Abstract

Purpose

HIV-related diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) may be biologically different from DLBCL in the general population. We compared, by HIV status, the expression and prognostic significance of selected oncogenic markers in DLBCL diagnosed at Kaiser Permanente in California, between 1996 and 2007.

Experimental Design

Eighty HIV-infected DLBCL patients were 1:1 matched to 80 HIV-uninfected DLBCL patients by age, gender, and race. Twenty-three markers in the following categories were examined using IHC: (i) cell-cycle regulators, (ii) B-cell activators, (iii) antiapoptotic proteins, and (iv) others, such as IgM. Tumor marker expression was compared across HIV infection status by Fisher exact test. For markers differentially expressed in HIV-related DLBCL, logistic regression was used to evaluate the association between tumor marker expression and 2-year overall mortality, adjusting for International Prognostic Index, cell-of-origin phenotype, and DLBCL morphologic variants.

Results

Expression of cMYC (% positive in HIV-related and -unrelated DLBCL: 64% vs. 32%), BCL6 (45% vs. 10%), PKC-β2 (61% vs. 4%), MUM1 (59% vs. 14%), and CD44 (87% vs. 56%) was significantly elevated in HIV-related DLBCLs, whereas expression of p27 (39% vs. 75%) was significantly reduced. Of these, cMYC expression was independently associated with increased 2-year mortality in HIV-infected patients [relative risk = 3.09 (0.90–10.55)] in multivariable logistic regression.

Conclusion

These results suggest that HIV-related DLBCL pathogenesis more frequently involves cMYC and BCL6 among other factors. In particular, cMYC-mediated pathogenesis may partly explain the more aggressive clinical course of DLBCL in HIV-infected patients.

Introduction

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is the most common subtype of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) occurring in HIV-infected individuals, accounting for greater than 40% of the diagnoses (1, 2). In the era of combination antiretroviral therapy (ART), survival of patients diagnosed with HIV-related lymphoma has significantly improved through enhanced immunity, functional status, and thus tolerability to standard chemotherapy (2, 3). However, compared with those without HIV infection, HIV-infected DLBCL patients continue to experience inferior outcomes (1). Clinically, HIV-related DLBCL frequently presents at advanced stage, with extranodal involvement, and positive for tumor Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) infection (4). These differences suggest that lymphomas arising in the setting of HIV infection may be biologically different from that in the general population.

There are limited comparative data on molecular characteristics of DLBCL by HIV status to inform patient management and development of novel therapeutics, especially for aggressive HIV-related lymphomas. Several classes of molecular markers have been implicated in DLBCL progression in the general population. For example, the expression of cell-cycle promoters, such as the cyclin family proteins, p27 and SKP2, has been linked to disease progression in DLBCL (5–8). B-cell activation/proliferation markers and apoptosis regulators have also been associated with disease outcomes. Expression of antiapoptotic proteins such as BCL2 has been linked to treatment resistance in DLBCL (9–11). However, the roles of these markers in HIV-related DLBCL remain unclear.

Our objective was to determine whether molecular pathogenic mechanisms for DLBCL are distinct for HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected patients diagnosed and managed in the ART era. Tumor markers compared by HIV status included selected cell-cycle regulators, B-cell activation markers, apoptosis regulators, and other markers that were previously identified as prognostic for DLBCL in the general population.

Materials and Methods

Study design, population, and setting

We included incident HIV-infected DLBCL patients and matched HIV-uninfected DLBCL patients diagnosed between 1996 and 2007 in the Kaiser Permanente (KP) Southern and Northern California Health Plans. KP Southern and Northern California are integrated health care delivery systems providing comprehensive medical services to more than seven million members who are broadly representative of the population in California (12, 13). DLBCL diagnoses were ascertained from KP’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER)-affiliated cancer registries. HIV infection status was identified through record linkage with KP’s HIV registries, which include all known cases of HIV infection dating back to the early 1980s for KP Northern California and dating to 2000 for KP Southern California. HIV-infected individuals are initially identified from electronic health records, and subsequently confirmed by manual chart review or with case confirmation with KP HIV clinics. All adult (≥18 years) HIV-infected patients diagnosed with DLBCL were eligible for the study. Because tumor biology can differ by age and DLBCLs tend to be diagnosed at younger age in HIV-infected persons, to ensure comparability of HIV-uninfected DLBCL patients to the HIV-infected patients, we matched subjects 1:1 by age groups (i.e., <30, 30–50, and >50 years), gender, and race (white vs. non-white). The KP Institutional Review Boards approved this study and provided waivers of informed consent.

Pathology review and tissue microarray construction

The study pathologists (J. Said and H.D. Zha) reviewed hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained slides to confirm the DLBCL diagnosis and identify representative tumor blocks for tissue microarray (TMA) construction. Whenever possible, three 1.2 mm cores from different areas of the donor block were obtained from each patient and inserted in a grid pattern into a recipient paraffin block using a tissue arrayer (Beecher Instruments).

IHC staining

IHC staining was performed on TMA cores to analyze the expression of selected B-cell oncogenic markers in the following categories: (i) cell-cycle promoters, including cyclin E, cMYC, p27, SKP2; (ii) B-cell activators/differentiation, including BCL6, FOXP1, PKC-β 2, CD21, and CD10; (iii) apoptotic regulators, including BCL2, p53, survivin, BAX, GAL3, and BLIMP1; and (iv) others, including MUM1, Ki-67, CD44, CD30, CD43, LMO2, MMP9, and IgM. All markers were selected on the basis of previously reported prognostic significance in DLBCL in the general population. Coexpressions of cMYC and BCL2, and of cMYC, BCL2, and BCL6 were also evaluated (14, 15). Expression of CD10, MUM1 and BCL6 was used to determine the germinal center (GC) phenotype using the Hans’ algorithm (16). Sections from paraffin-embedded blocks were cut at 4 μm and paraffin removed with xylene and rehydrated through graded ethanols. Heat-induced antigen retrieval and proteolytic-induced epitope retrieval were used. Following this pretreatment, the slides were incubated with primary antibodies for the markers of interest. The detailed antibody information, incubation method, and signal detection for each marker were described elsewhere (17). All staining was performed manually. Normal tonsillar lymphoid tissue was included as a positive control. Negative controls for each case consisted of substituting the primary antibody with isotype-specific noncross reacting antibody matching the primary antibody.

The percentage of DLBCL cells with visible marker staining was scored on a scale from 0–4 (0: 0%–9%, 1: 10%–24%, 2: 25%–49%, 3:–50% 74%, and 4: ≥75%). Scoring was performed manually by one study pathologist and confirmed by another study pathologist for all markers except for Ki-67, which was scored on a computerized automated image analysis platform (Definiens TissueStudio). Cases with discrepant scores (about 10%) were resolved by re-review with double headed microscope. Tumor EBV infection status was not included in the current analyses since we evaluated this marker in our previous study (17) which included the same patients as reported here.

DLBCL morphologic variants

DLBCL morphologic variant subtyping was performed by the two study pathologists independently by reviewing pathology reports, H&E slides, and stained tumor marker expression data. Minor classification discrepancies on two patients were resolved after applying the WHO’s 2008 classification system of tumors of the hematopoietic and lymphoid tissues.

Ascertainment of patient survival

Two-year mortality was chosen as the outcome because most deaths in HIV-infected patients (85% in our study) occurred within 2 years after DLBCL diagnosis. Mortality ascertainment was complete for all subjects, even in the event of termination of KP membership, through record linkage with KP’s membership and utilization files, California’s state death file, and social security death records. As such, there was no loss-to-follow up for the mortality outcomes.

Covariates

The standard International Prognostic Index (IPI) was calculated on the basis of age, clinical stage, extranodal involvement, serum lactose dehydrogenase (LDH), and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status (18, 19). Age at DLBCL diagnosis, stage at diagnosis, and extranodal involvement were collected from KP’s cancer registries. Serum LDH level at DLBCL diagnosis was obtained from KP’s laboratory databases. Health service utilization records, including home health visits, hospitalization and rehabilitation, and comorbidity status were used to estimate performance status (20). Among HIV-infected DLBCL patients, we also collected HIV disease factors from KP’s HIV registries, including prior AIDS diagnosis, use of ART, and duration of known HIV infection. CD4 cell counts at DLBCL diagnosis and lowest (nadir) recorded at KP were obtained from KP’s laboratory databases. Information on the receipt of chemotherapy was collected from KP’s cancer registries. In addition, information on disease progression and relapse was collected via manual chart review for HIV-infected patients for analysis to confirm the prognostic role of any tumor markers found to predict increased mortality in HIV-infected DLBCL patients.

Statistical analysis

The demographic and DLBCL characteristics were compared between patients who were HIV infected versus uninfected. The mean and SD of the expression score (staining score) for each tumor marker were calculated by HIV status. Tumor marker expression was also considered as “positive” or “negative” based on previously published cutoff values for each marker, and compared using the Fisher exact test. Because of the small sample size in the analytical subcohort, P value <0.10 was used as the cutoff for statistical significance in this study. Bonferroni method was used to adjust for multiple comparisons (21).

For markers that were differentially expressed by HIV status, their expression levels within the GC phenotype, the non-GC phenotype, and within the centroblastic variant (the most common DLBCL variant) were also examined. Associations between clinical stage, extranodal involvement, and expression of these markers were further examined in HIV-infected patients. Because HIV-related lymphomagenesis is related to immunosuppression, we hypothesized that differential expression of oncogenic markers by HIV status may be driven by differences in immune function. To test this hypothesis, the associations between prior AIDS diagnosis, prior ART use, CD4 cell counts, both at DLBCL diagnosis and the lowest recorded at KP, and tumor marker positivity were examined using t test in HIV-infected patients.

To explore whether the different molecular characteristics of DLBCL may explain the more aggressive clinical course in HIV-related DLBC, the prognostic significance of markers that were differentially expressed by HIV status was examined. Kaplan–Meier survival curves for each of these markers were generated. The association between tumor marker positivity and 2-year overall mortality was examined using bivariate and multivariable logistic regression, adjusting for IPI, GC phenotype, DLBCL variants (centroblastic, immunoblastic, and plasmablastic), and chemotherapy treatment. These analyses were performed separately for HIV-infected and -uninfected patients. Missing data were handled using the multiple imputation method proposed by Rubin in these analyses (22). For markers found to predict increased mortality in HIV-infected patients, the analyses were also repeated for progression-free survival. Disease progression was defined as relapse after complete remission or progression after partial remission or nonresponse. All analyses were performed with SAS Version 9.2.

Results

The characteristics of the 80 HIV-infected and the 80 matched HIV-uninfected DLBCL patients are presented in Table 1. The mean age at DLBCL diagnosis was similar by HIV status (50 years) due to matching. The majority of the patients were male (~90%) and of non-Hispanic white (~60%). HIV-infected patients with DLBCL, compared with HIV-uninfected patients, were more likely to be diagnosed at advanced cancer stage (48% and 29%; P = 0.01), with extranodal involvement (43% vs. 11%, P < 0.01) and have germinal center phenotype (39% vs. 26%; P = 0.01). HIV-infected patients had a mean CD4 cell count of 206 cells/ mm3 at DLBCL diagnosis, and a mean 5-year duration of known HIV infection before DLBCL diagnosis. Among the HIV-infected DLBCL patients, a total of 37 deaths (46%) occurred during the 2-year follow-up (Table 1). In contrast, only 13 (16%) deaths occurred in the 2-year period among the 80 matched HIV-uninfected DLBCL patients.

Table 1.

DLBCL patient characteristics by HIV infection status

| HIV-infected (N = 80) | HIV-uninfected (N = 80) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years, mean (SD) | 47.9 (9.2) | 50.6 (15.9) | 0.97 |

| Male gendera | 74 (92.5%) | 70 (87.5%) | 0.29 |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| White | 47 (58.8%) | 47 (58.8%) | 1.00 |

| Non-white | 33 (41.2%) | 33 (41.2%) | |

| Known duration of HIV infection, year, mean (SD) | 5.2 (5.80) | — | — |

| Prior AIDS diagnosis | 34 (42.5%) | — | — |

| Prior use of ART | 52 (65.0%) | — | — |

| CD4 cell count at DLBCL diagnosis, cells/mm3, mean (SD) | 206.2 (166.9) | — | — |

| Lowest CD4 cell count recorded in KP before DLBCL diagnosis, cells/mm3, mean (SD) | 71.2 (66.7) | — | — |

| SEER summary stage | |||

| I (localized) | 20 (25%) | 38 (47.5%) | 0.01 |

| II (regional) | 14 (17.5%) | 15 (18.8%) | |

| III (advanced) | 38 (47.5%) | 23 (28.8%) | |

| Unknown | 8 (10%) | 4 (5%) | |

| Extranodal involvement | |||

| Yes | 33 (41.3%) | 9 (11.3%) | <0.01 |

| Unknown | 0 (0%) | 19 (23.8%) | |

| Cell-of-origin phenotype | |||

| Germinal center (GC) | 31 (38.8%) | 21 (26.3%) | 0.01 |

| Non-GC | 41 (51.3%) | 58 (72.5%) | |

| Unknown | 8 (10.0%) | 1 (1.3%) | |

| DLBCL subtype | |||

| Centroblastic | 56 (70.0%) | 72 (90%) | <0.01 |

| Immunoblastic | 18 (22.5%) | 5 (6.3%) | |

| Plasmablastic | 6 (7.5%) | 1 (1.3%) | |

| Unknown | 0 (0%) | 2 (2.5%) | |

| DLBCL treatment modality | |||

| Chemotherapy | 60 (75.0%) | 67 (83.8%) | 0.17 |

| Chemotherapy + radiation | 10 (12.5%) | 19 (23.8%) | |

| Radiation therapy only | 3 (3.8%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Two-year mortality | 37 (46.3%) | 13 (16.3%) | <0.01 |

Exact match of gender was not achieved because of lack of appropriate tumor specimens of matched HIV-uninfected patients for 4 HIV-infected patients. The HIV-uninfected comparisons for those 4 HIV-infected patients were thus replaced by additional matched HIV-uninfected patients for other HIV-infected patients.

HIV infection status and tumor marker expression

The expression of the following tumor markers was found to be substantially different in HIV-infected patients: an elevated expression was observed for cMYC, BCL6, PKC-β2, MUM1, CD44, CD30, MMP9, and IgM; while a reduced expression was observed for p27, FOXP1, and GAL3 (Table 2). After accounting for multiple comparisons, the differences by patient HIV status remained statistically significant for cMYC, p27, BCL6, PKC-β2, MUM1, and CD44. Of these six markers, the greatest difference in expression level was seen for PKC-β2: mean expression level was 2.7 (SD: 1.7) in HIV-related and 0.5 (0.8) for HIV-unrelated DLBCL.

Table 2.

Expression level of selected tumor markers measured by IHC staining in DLBCL by HIV infection status

| Tumor marker | HIV-infectedb | HIV-uninfectedb | Pc | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cell-cycle regulator | ||||

| Cyclin E | % tumor cells positivea | 23.2% | 15.4% | 0.29 |

| Mean expression level (SD)d | 1.4 (1.4) | 1.3 (1.1) | ||

| cMYC | 64.3% | 32.1% | <0.01e | |

| 1.5 (1.5) | 0.4 (0.7) | |||

| P27 | 39.2% | 74.7% | <0.01e | |

| 0.5 (0.8) | 1.0 (0.7) | |||

| SKP2 | 8.1% | 10.1% | 0.78 | |

| 0.4 (1.0) | 1.0 (1.0) | |||

| B-cell activator/differentiation | ||||

| BCL6 | % tumor cells positivea | 45.2% | 10.1% | <0.01e |

| Mean expression level (SD)d | 1.5 (1.4) | 0.4 (0.8) | ||

| FOXP1 | 36.0% | 59.5% | <0.01 | |

| 1.2 (1.3) | 1.9 (1.4) | |||

| PKC-β2 | 61.1% | 3.8% | <0.01e | |

| 2.7 (1.7) | 0.5 (0.8) | |||

| CD21 | 1.4% | 1.3% | 1.00 | |

| 0.0 (0.1) | 0.0 (0.1) | |||

| CD10 | 28.8% | 21.5% | 0.46 | |

| 1.1 (1.4) | 0.6 (1.1) | |||

| Apoptosis regulator | ||||

| BCL2 | % of tumor with positivea | 51.4% | 50.7% | 1.00 |

| Mean expression level (SD)d | 1.7 (1.3) | 1.6 (1.5) | ||

| P53 | 16.0% | 10.1% | 0.34 | |

| 0.7 (1.2) | 0.3 (0.8) | |||

| Survivin | 76.8% | 87.3% | 0.13 | |

| 2.8 (1.5) | 2.6 (1.2) | |||

| BAX | 74.7% | 76.0% | 1.00 | |

| 2.6 (1.5) | 2.6 (1.3) | |||

| GAL3 | 26.1% | 45.6% | 0.02 | |

| 1.5 (1.5) | 2.1 (1.8) | |||

| BLIMP1 | 9.9% | 13.8% | 0.62 | |

| 0.3 (0.8) | 0.7 (0.9) | |||

| Others | ||||

| MUM1 | % of tumor with positivea | 58.9% | 13.9% | <0.01e |

| Mean expression level (SD)d | 1.8 (1.5) | 0.5 (0.9) | ||

| Ki-67 | 35.3% | 41.8% | 0.50 | |

| 2.1 (0.8) | 2.2 (1.1) | |||

| CD44 | 86.7% | 55.8% | <0.01e | |

| 2.8 (1.2) | 1.9 (1.5) | |||

| CD30 | 23.6% | 7.7% | <0.01 | |

| 1.0 (1.5) | 0.3 (0.9) | |||

| CD43 | 23.3% | 32.1% | 0.15 | |

| 1.1 (1.6) | 1.7 (1.5) | |||

| LMO2 | 55.4% | 62.0% | 0.42 | |

| 2.0 (1.5) | 2.2 (1.5) | |||

| MMP9 | 41.2% | 19.2% | <0.01 | |

| 2.0 (1.7) | 1.3 (1.3) | |||

| IgM | 53.4% | 38.5% | 0.07 | |

| 2.0 (1.8) | 1.5 (1.9) | |||

| Co-expression phenotype | ||||

| cMYC+ and BCL2+ | 25.3% | 13.9% | 0.07 | |

| cMYC+, BCL2+ and BCL6+ | 7.9% | 1.3% | 0.05 | |

Cutoff value for positivity: cyclin E: 3+; c-MYC: 1+; p27: 1+; SKP2: 3+; BCL6: 2+; FOXP1:2+; PKC-β2: 3+; CD21: 2+; CD10: 2+; BCL2: 2+; p53:2+; survivin: 2+; BAX: 2+; GAL3: 3+; BLIMP1: 2+; MUM1:2+, Ki-67:3+; CD44: 2+; CD30: 2+; CD43: 3+; LMO2: 2+; MMP9: 3+; IgM: 2+.

Number included in each tumor marker analysis varies slightly due to failure of staining in some specimens.

P value obtained from Fisher exact test.

Tumor marker score 0 = 0%–9%, 1 = 10%–24%, 2 = 25%–49%, 3 = 50%–74%, and 4 = ≥75% of DLBCL cells stained positive for the marker.

Statistical significance at P < 0.10 level after adjusting for multiple comparisons using the Bonferroni method (0.10/25 comparisons = 0.004).

DLBCLs in HIV-infected patients also more frequently presented with coexpression of cMYC and BCL2 (25% vs. 14%, Table 2, bottom), and of cMYC, BCL2, and BCL6 (8% vs. 1%).

Tumor marker expression by cell-of-origin phenotype and in centroblastic subtype

Statistically significant differences in expression of cMYC, p27, BCL6, PKC-β2, MUM1, and CD44 by HIV status continued to be observed within subgroups defined by cell-of-origin (data not shown). Similar results were found when we restricted the analyses to only the centroblastic variant (data not shown).

Associations between tumor marker expression and DLBCL clinical characteristics

No clear association was found between DLBCL clinical stage and expression of cMYC, p27, BCL6, PKC-β2, MUM1, and CD44 within HIV-infected patients (Table 3). p27 and BCL6 expressions were found to be associated with increased and decreased extra-nodal involvement in HIV-infected patients, respectively. However, the directions of these associations do not explain the more frequent extranodal involvement in HIV-related DLBCL compared with HIV-unrelated DLBCL.

Table 3.

Associations between tumor marker expression and clinical stage and extranodal involvement: HIV-related DLBCL

| Marker positivity | cMYC

|

P27

|

BCL6

|

PKC-β2

|

MUM1

|

CD44

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| − | + | − | + | − | + | − | + | − | + | − | + | |

| n = 25 | n = 45 | n = 45 | n = 29 | n = 40 | n = 23 | n = 28 | n = 44 | n = 33 | n = 43 | n = 10 | n = 65 | |

| Stage | Column percent (% of stage within subgroups defined by marker positivity) | |||||||||||

| Localized | 25.0% | 26.2% | 36.8% | 17.9% | 50.0% | 50.0% | 29.6% | 24.3% | 27.6% | 25.6% | 30.0% | 26.3% |

| Regional | 25.0% | 16.7% | 15.8% | 21.4% | 10.8% | 27.6% | 22.2% | 16.2% | 17.2% | 20.5% | 30.0% | 15.8% |

| Distant | 50.0% | 57.1% | 47.4% | 60.7% | 64.9% | 41.4% | 48.2% | 59.5% | 55.2% | 53.9% | 40.0% | 57.9% |

| P value | 0.73 | 0.24 | 0.11 | 0.66 | 0.94 | 0.47 | ||||||

| Extranodal involvement | Column percent (% of extranodal involvement within subgroups defined by marker positivity) | |||||||||||

| Yes | 48.0% | 42.2% | 33.3% | 58.6% | 52.5% | 30.3% | 50.0% | 40.9% | 39.4% | 44.2% | 40.0% | 43.1% |

| P value | 0.64 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.45 | 0.67 | 0.85 | ||||||

Tumor marker expression by immune status

We did not find an association between prior AIDS diagnosis, prior ART use, or CD4 cell count and expression of cMYC, p27, BCL6, PKC-β2, and CD44 (data not shown for prior AIDS or ART use) in patients with HIV-related DLBCL. MUM1 expression, however, was found to be positively associated with prior AIDS diagnosis: 70% in those with prior AIDS expressed MUM1, compared with 47% in those without prior AIDS (P value =0.04). This is consistent with the finding that a significantly lower CD4 cell count, both at DLBCL diagnosis and as the lowest recorded at KP, was observed in those positive for MUM1 expression compared with those without MUM1 expression (Table 4).

Table 4.

CD4 cell count by tumor marker expression status in HIV-infected patients

| Marker positivity | cMYC

|

P27

|

BCL6

|

PKC-β2

|

MUM1

|

CD44

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| − | + | − | + | − | + | − | + | − | + | − | + | |

| n = 24 | n = 44 | n = 43 | n = 29 | n = 39 | n = 32 | n = 28 | n = 42 | n = 31 | n = 43 | n = 10 | n = 63 | |

| CD4 cell count | Mean (SD), cells/mm3 | |||||||||||

| At DLBCL diagnosis | 221 (174) | 204 (162) | 199 (163) | 202 (170) | 210 (187) | 212 (137) | 218 (151) | 196 (174) | 254 (163) | 179 (166) | 223 (179) | 207 (162) |

| P value | 0.71 | 0.94 | 0.26 | 0.61 | 0.08 | 0.80 | ||||||

| Lowest recorded at KP | 65 (56) | 78 (71) | 71 (69) | 69 (62) | 66 (74) | 84 (62) | 81 (73) | 65 (61) | 96 (75) | 58 (57) | 78 (72) | 73 (68) |

| P value | 0.46 | 0.91 | 0.26 | 0.33 | 0.02 | 0.82 | ||||||

Tumor marker expression and 2-year mortality by HIV infection status

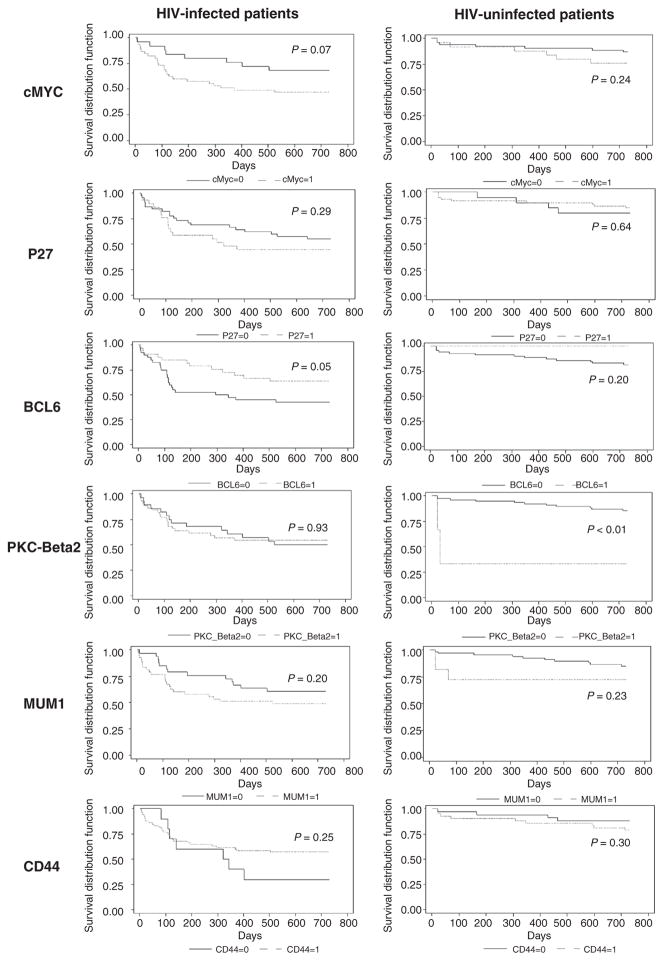

Figure 1 shows the Kaplan–Meier curve for 2-year mortality by marker expression status in HIV-infected and -uninfected patients. The crude and the adjusted associations between tumor marker expression and 2-year overall mortality are shown in Table 5. In the adjusted analyses, cMYC expression [OR =3.09 (0.90–10.55), P = 0.07] was significantly associated with increased 2-year mortality in HIV-infected DLBCL patients. When we further explored the role of cMYC expression on progression-free survival in these patients, we confirmed a positive association between cMYC expression and disease progression [OR = 2.53 (0.75–8.60)]. Increased mortality was noted among HIV-uninfected DLBCL patients with expression of cMYC [OR = 2.84 (0.54–15.01)], PKC-β2 [OR =3.93 (0.19–83.28)], and CD44 [RR =1.52 (0.28–8.25)], although these associations were not statistically significant.

Figure 1.

Kaplan–Meier survival curves for 2-year mortality by tumor marker expression status All. P values are from the log-rank test.

Table 5.

Crude and adjusted association between tumor marker positivity and 2-year overall mortality DLBCL patients by HIV infection status

| Tumor marker positivity | HIV-infected patients | HIV-uninfected patients | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bivariate analyses (crude) | ||||

| OR (95% CI) | P | OR (95% CI) | P | |

| cMYC | 2.36 (0.87–6.42) | 0.09 | 2.05 (0.61–6.90) | 0.25 |

| P27 | 1.61 (0.63–4.10) | 0.32 | 0.72 (0.19–2.65) | 0.62 |

| BCL6 | 0.45 (0.18–1.15) | 0.10 | —a | |

| PKC-β2 | 0.86 (0.34–2.19) | 0.75 | 11.58 (0.97–138.76) | 0.05 |

| MUM1 | 1.63 (0.65–4.07) | 0.30 | 2.10 (0.48–9.30) | 0.33 |

| CD44 | 0.32 (0.08–1.27) | 0.11 | 1.98 (0.55–7.09) | 0.29 |

| Multivariable analyses (adjusted)b | ||||

| cMYC | 3.09 (0.90–10.55) | 0.07 | 2.84 (0.54–15.01) | 0.22 |

| P27 | 1.44 (0.49–4.22) | 0.50 | 0.18 (0.03–1.27) | 0.08 |

| BCL6 | 0.48 (0.12–1.87) | 0.29 | —a | |

| PKC-β2 | 0.54 (0.17–1.69) | 0.29 | 3.93 (0.19–83.28) | 0.38 |

| MUM1 | 0.90 (0.29–2.79) | 0.85 | 0.80 (0.10–6.54) | 0.83 |

| CD44 | 0.18 (0.04–0.89) | 0.04 | 1.52 (0.28–8.25) | 0.63 |

OR cannot be estimated due to rare marker expression.

Model adjusted for IPI, germinal center phenotype, DLBCL subtype, and receipt of chemotherapy. Gender and race were matched and thus did not require adjustment in the multivariable model.

Expression of a couple markers was found to be associated with reduced mortality. These included CD44 expression in HIV-infected DLBCL patients [OR = 0.18 (0.04–0.89)], and P27 expression in HIV-uninfected patients [OR = 0.18 (0.03–1.27)]

Discussion

The distinct clinical features and aggressive behavior of HIV-related DLBCL beg the question whether DLBCLs in HIV-infected individuals are biologically different from DLBCLs in the general population. This knowledge is critical to improve outcomes of HIV-infected patients with DLBCL. Findings from this study suggest that DLBCLs from HIV-infected and -uninfected patients are systematically different in their molecular characteristics, particularly with respects to several cell-cycle regulators and B-cell activation markers. Specifically, our results suggest that overexpression of cMYC, BCL6, PKC-β2, MUM1, and CD44, and silencing of CDKN1B (gene that encodes p27) are more commonly involved in DLBCL pathogenesis in HIV-infected patients. Furthermore, cMYC expression was found to be associated with inferior survival in HIV-infected patients. Thus, the difference in cMYC expression may partly explain the aggressiveness of HIV-related DLBCL. These results point to the need of molecular risk stratification and novel therapeutic approaches for HIV-infected patients who do not respond well to standard therapy.

cMYC is a transcription factor that plays an important role in regulating proliferation, cell growth, apoptosis, and metabolism (23). Persistent expression of cMYC leads to the dysregulation of many genes, including the cyclin family proteins. Dysregulation of cMYC has also been linked to treatment resistance in several cancer models (24, 25). Consistent with the notion that MYC gene alterations in DLBCL are often associated with BCL6 translocation (14), we also observed elevated expression of BCL6. BCL6 expression is usually associated with the GC phenotype, a subtype of DLBCL with favorable prognosis under standard chemotherapy, although BCL6 can also be found in activated B-cell DLBCL. In our study, even after restricting to the GC subtype, a significantly greater proportion of the HIV-related DLBCL expressed BCL6 (77% in HIV-related vs. 38% in HIV-unrelated), sustaining the dominant role of BCL6-associated malignant transformation in HIV-related DLBCL. On the other hand, the expression of MUM1 protein appears at the later stages of B-cell differentiation after the expression of BCL6. MUM1 is consistently found at all stages of differentiation of plasma cells, and is associated with the more treatment-resistant activated B-cell subtypes. Similar to the BCL6 observation, elevated expression of MUM1 in HIV-related DLBCL was found even after restricting to the non-GC subtype, suggesting a more common MUM1-associated pathogenesis in HIV-related DLBCL. p27 is a marker expressed in nonproliferating lymphocytes in HIV-unrelated DLBCL, encoded by gene CDKN1B. Studies have shown that CDKN1B is a BCL6 target gene and is repressed by BCL6 expression (26). It is therefore possible that the reduced level of p27 observed in HIV-related DLBCL may be a result of the increased BCL6 expression.

The exact mechanism of how these pathways involving cell-cycle regulation and B-cell activation may become preferentially initiated in the setting of HIV infection is not clear. To this end, we explored the hypothesis that expression of these oncogenic markers was driven by mechanisms related to immunosuppression in the HIV-infected cohort. We did not find associations between the expression of most of these markers and level of CD4 cell count, except for MUM1 expression, which was associated with a reduced CD4 cell count. Consistent with this finding, a lower nadir CD4 cell count (but not CD4 cell count at DLBCL diagnosis) was also found among those with non-GC subtype compared with the those with GC subtype [mean (SD) was 63 (69) cells/mm3 vs. 90 (66) cells/ mm3, P value = 0.10]. However, it should be noted that most of our HIV-infected patients (75 out of 80) experienced a nadir CD4 cell count of less than 200 cells/mm3. Given the limited range of nadir CD4 cell count in our cohort, the lack of associations between CD4 cell count and most of these markers does not entirely exclude the possibility that immunosuppression in HIV-infected patients selectively promote these molecular pathogenic mechanisms compared to HIV-uninfected patients.

Another potential mechanism that may drive the differential marker expression by HIV status is EBV-induced pathogenesis. We have previously reported on the association between tumor EBV status and oncogenic tumor marker expression in the same HIV-infected DLBCL patients (17). EBV positivity was found in 30% of our HIV-infected and 10% of the matched HIV-uninfected DLBCL patients, respectively. However, expression of most of the six markers, except BCL6, was not associated with tumor EBV status in HIV-related DLBCL. Moreover, tumor EBV infection was inversely associated with BCL6 expression, which does not explain the elevated expression of BCL6 in HIV-related DLBCL. It should be noted that due to the small sample size of these subanalyses, these comparisons should be considered exploratory.

Interestingly, several markers, such as p27 and CD44, appear to have opposite prognostic implications for HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected patients. For example, although CD44 expression was associated with increased mortality in HIV-uninfected patients (not statistical significant), the relative risk was less than unity for HIV-infected patients. The prognostic significance of p27 has been controversial even within DLBCL in the general population (7, 31). In our analyses, p27 expression was associated with a reduced mortality in HIV-uninfected patients, but this was not the case in HIV-infected patients. However, given the overlapping confidence intervals of these estimates in HIV-infected versus-uninfected patients (that are likely a result of the small sample sizes), additional studies will be needed to clarify whether these molecules play a different role in disease progression in HIV-related DLBCL from DLBCL in the general population.

Few studies have examined the molecular characteristics of HIV-related lymphoma in comparison with lymphoma in the general population. Little and colleagues examined six IHC markers (MIB1, BCL2, MUM1, CD10, BCL6, and p53) among 25 HIV-infected and 33 HIV-uninfected B-cell lymphoma patients between 1995 and 2000 (27). They reported that lymphomas in HIV-infected patients expressed lower level of BCL2, higher CD10 and p53, and were highly proliferative. These results contrasted our findings that BCL2, CD10, and p53 were similarly expressed by HIV status. Proliferative index Ki-67 was also not overly expressed in HIV-related DLBCL in our study. However, it should be noted that Little and colleagues did not separately examine DLBCL from Burkitt lymphoma. The inclusion of Burkitt lymphoma may explain the different findings between studies, as Hoffmann and colleagues reported less frequent expression of BCL2 and more frequent expression of CD10 in HIV-related Burkitt lymphoma compared with HIV-related DLBCL (28). An earlier study by Schlaifer and colleagues that examined 36 HIV-infected and 109 HIV-uninfected NHL patients also reported less frequent BCL2 expression and more frequent p53 expression in HIV-related NHL (29). However, this study also included all NHL subtypes and was based on patients in the pre-ART era.

There are few comparative studies by HIV status within histology subtype such as DLBCL. Yet, histology-specific data are critical as tumor characteristics and treatment implications vary substantially for each NHL subtype. A recent study by Morton and colleagues compared molecular characteristics of HIV-related versus HIV-unrelated DLBCL with regard to cells of origin and translocations of cMYC, BCL2, and BCL6 (30). They found cMYC translocation the most common translocation of the three evaluated, and 31% of the HIV-related DLBCL tumors had any one of the three translocations. However, this study mainly included patients diagnosed in the pre-ART era where EBV infection was seen in most HIV-infected patients (i.e., >60% vs. 30% in our study, which is based on patients in the ART era). Thus, their results may not be generalizable to patients diagnosed in the ART era.

A potential limitation of this study was the limited sample size for certain subgroup comparisons and prognostic analysis for the matched HIV-uninfected DLBCL patients for whom there were fewer death events. This may explain the lack of statistical significance of cMYC and PKC-β2 in HIV-uninfected DLBCL patients despite potentially meaningful magnitudes of associations. Also, we choose a cutoff value for defining cMYC-positivity (i.e., ≥10% expression) based on Copie-Bergman and colleagues (31), while a higher cutoff has been recommended by others. To this end, in our sensitivity analysis using a higher cutoff value, that is, ≥50% to define cMYC positivity, HIV-related DLBCL patients continue to have elevated expression (26% cMYC-positive compared with1% in HIV-unrelated DLBCL patients, P < 0.01).

In conclusion, our study is based on a well-defined cohort of HIV-infected DLBCL patients from the ART era that is among the largest reported in the literature for the tumor marker analysis. In addition, the comparisons conducted with an internally matched HIV-uninfected DLBCL cohort from the same managed care population minimizes confounding in survival outcomes due to differential access to care or population characteristics. Our data suggest that DLBCL pathogenesis in the context of HIV infection more frequently involves over expression of several transcription regulators, including cMYC, BCL6, and MUM1, as well as cell signaling pathways related to PKC-β2 and CD44. In particular, cMYC expression is associated with increased mortality in both HIV-infected and -uninfected DLBCL patients, independent of established prognostic factors. Given that cMYC is expressed in two-thirds of the HIV-related DLBCL tumors compared with one-third of HIV-unrelated DLBCL, cMYC-mediated pathogenic mechanisms may in part explain the poorer clinical outcomes in HIV-infected DLBCL patients. These results suggest that cMYC may serve as a novel therapeutic target for HIV-related DLBCL. Future studies should examine whether the elevated cMYC expression in HIV-related DLBCL is associated with gene rearrangement and the double-hit or the triple hit (with BCL2 and/or BCL6) lymphomas, which may further inform patient risk stratification and treatment.

Translational Relevance.

HIV-related diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) often presents at an advanced stage and has an aggressive clinical course. It is thus possible that HIV-related DLBCLs are biologically different from DLBCL in the general population. In this study, we found that HIV-related DLBCLs are characterized with differential tumor marker expression compared with HIV-unrelated DLBCLs. Specifically, DLBCL pathogenesis in the context of HIV infection appears to more frequently involve overexpression of several transcription regulators, including cMYC, BCL6, and MUM1. In particular, elevated cMYC expression in HIV-related DLBCL predicted inferior survival and may partly explain the more aggressive clinical course of these lymphomas. These results suggest that cMYC may serve as a novel therapeutic target for HIV-related DLBCL.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Wendy Leyden for programming support and Courtney Ellis and Michelle McGuire for project management support.

Grant Support

This work was supported by an NCI grant R01CA134234-01 “Prognostic Markers for HIV-Positive DLBCL.” The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked advertisement in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

Note: Supplementary data for this article are available at Clinical Cancer Research Online (http://clincancerres.aacrjournals.org/).

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

M.J. Silverberg reports receiving a commercial research grant from Merck. No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed by the other authors.

Authors’ Contributions

Conception and design: C. Chao, M.J. Silverberg, O. Martínez-Maza, D.I. Abrams, J. Said

Development of methodology: C. Chao, L. Xu, J. Said

Acquisition of data (provided animals, acquired and managed patients, provided facilities, etc.): C. Chao, M.J. Silverberg, L. Xu, H.D. Zha, J. Said, B. Castor

Analysis and interpretation of data (e.g., statistical analysis, biostatistics, computational analysis): C. Chao, M.J. Silverberg, L. Xu, L.-H. Chen, H.D. Zha, R. Haque, J. Said

Writing, review, and/or revision of the manuscript: C. Chao, M.J. Silverberg, L. Xu, L.-H. Chen, O. Martínez-Maza, D.I. Abrams, H.D. Zha, R. Haque, J. Said

Administrative, technical, or material support (i.e., reporting or organizing data, constructing databases): M.J. Silverberg, L. Xu, J. Said

Study supervision: C. Chao, M.J. Silverberg, J. Said

References

- 1.Chao C, Xu L, Abrams D, Leyden W, Horberg M, Towner W, et al. Survival of non-Hodgkin lymphoma patients with and without HIV infection in the era of combined antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 2010;24:1765–70. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32833a0961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Diamond C, Taylor TH, Aboumrad T, Anton-Culver H. Changes in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome-related non-Hodgkin lymphoma in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy: incidence, presentation, treatment, and survival. Cancer. 2006;106:128–35. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vaccher E, Spina M, di GG, Talamini R, Nasti G, Schioppa O, et al. Concomitant cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and predni-sone chemotherapy plus highly active antiretroviral therapy in patients with human immunodeficiency virus-related, non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Cancer. 2001;91:155–63. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20010101)91:1<155::aid-cncr20>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fisher SG, Fisher RI. The epidemiology of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Oncogene. 2004;23:6524–34. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hans CP, Weisenburger DD, Greiner TC, Chan WC, Aoun P, Cochran GT, et al. Expression of PKC-beta or cyclin D2 predicts for inferior survival in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Mod Pathol. 2005;18:1377–84. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tzankov A, Gschwendtner A, Augustin F, Fiegl M, Obermann EC, Dirnhofer S, et al. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma with overexpression of cycline substantiates poor standard treatment response and inferior outcome. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12(7 Pt 1):2125–32. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Erlanson M, Portin C, Linderholm B, Lindh J, Roos G, Landberg G. Expression of cyclin E and the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p27 in malignant lymphomas-prognostic implications. Blood. 1998;92:770–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Seki R, Okamura T, Koga H, Yakushiji K, Hashiguchi M, Yoshimoto K, et al. Prognostic significance of the F-box protein Skp2 expression in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Am J Hematol. 2003;73:230–5. doi: 10.1002/ajh.10379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kramer MH, Hermans J, Parker J, Krol AD, Kluin-Nelemans JC, Haak HL, et al. Clinical significance of bcl2 and p53 protein expression in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: a population-based study. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14:2131–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1996.14.7.2131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kramer MH, Hermans J, Wijburg E, Philippo K, Geelen E, van Krieken JH, et al. Clinical relevance of BCL2, BCL6, and MYC rearrangements in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Blood. 1998;92:3152–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ichikawa A, Kinoshita T, Watanabe T, Kato H, Nagai H, Tsushita K, et al. Mutations of the p53 gene as a prognostic factor in aggressive B-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:529–34. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199708213370804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koebnick C, Langer-Gould AM, Gould MK, Chao CR, Iyer RL, Smith N, et al. Sociodemographic characteristics of members of a large, integrated health care system: comparison with US Census Bureau data. Perm J. 2012;16:37–41. doi: 10.7812/tpp/12-031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gordon NP. How does the Adult Kaiser Permanente Membership in Northern California compare with the larger community? Oakland: KP Division of Research; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ott G, Rosenwald A, Campo E. Understanding MYC-driven aggressive B-cell lymphomas: pathogenesis and classification. Blood. 2013;122:3884–91. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-05-498329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Green TM, Young KH, Visco C, Xu-Monette ZY, Orazi A, Go RS, et al. Immunohistochemical double-hit score is a strong predictor of outcome in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated with rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:3460–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.41.4342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hans CP, Weisenburger DD, Greiner TC, Gascoyne RD, Delabie J, Ott G, et al. Confirmation of the molecular classification of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma by immunohistochemistry using a tissue microarray. Blood. 2004;103:275–82. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-05-1545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chao C, Silverberg MJ, Martinez-Maza O, Chi M, Abrams DI, Haque R, et al. Epstein-Barr virus infection and expression of B-cell oncogenic markers in HIV-related diffuse large B-cell Lymphoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:4702–12. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-3169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rossi G, Donisi A, Casari S, Re A, Cadeo G, Carosi G. The International Prognostic Index can be used as a guide to treatment decisions regarding patients with human immunodeficiency virus-related systemic non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Cancer. 1999;86:2391–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mounier N, Spina M, Gabarre J, Raphael M, Rizzardini G, Golfier JB, et al. AIDS-related non-Hodgkin lymphoma: final analysis of 485 patients treated with risk-adapted intensive chemotherapy. Blood. 2006;107:3832–40. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-09-3600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Salloum RG, Smith TJ, Jensen GA, Lafata JE. Using claims-based measures to predict performance status score in patients with lung cancer. Cancer. 2011;117:1038–48. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bland JM, Altman DG. Multiple significance tests: the Bonferroni method. BMJ. 1995;310:170. doi: 10.1136/bmj.310.6973.170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rubin DB. Multiple Imputation for Nonresponse in Surveys. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cotterman R, Jin VX, Krig SR, Lemen JM, Wey A, Farnham PJ, et al. N-Myc regulates a widespread euchromatic program in the human genome partially independent of its role as a classical transcription factor. Cancer Res. 2008;68:9654–62. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sengupta S, Biarnes MC, Jordan VC. Cyclin dependent kinase-9 mediated transcriptional de-regulation of cMYC as a critical determinant of endocrine-therapy resistance in breast cancers. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2014;143:113–24. doi: 10.1007/s10549-013-2789-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Manfe V, Biskup E, Willumsgaard A, Skov AG, Palmieri D, Gasparini P, et al. cMyc/miR-125b-5p signalling determines sensitivity to bortezomib in preclinical model of cutaneous T-cell lymphomas. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e59390. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0059390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shaffer AL, Yu X, He Y, Boldrick J, Chan EP, Staudt LM. BCL-6 represses genes that function in lymphocyte differentiation, inflammation, and cell cycle control. Immunity. 2000;13:199–212. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)00020-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Little RF, Pittaluga S, Grant N, Steinberg SM, Kavlick MF, Mitsuya H, et al. Highly effective treatment of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome-related lymphoma with dose-adjusted EPOCH: impact of anti-retroviral therapy suspension and tumor biology. Blood. 2003;101:4653–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-11-3589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hoffmann C, Tiemann M, Schrader C, Janssen D, Wolf E, Vierbuchen M, et al. AIDS-related B-cell lymphoma (ARL): correlation of prognosis with differentiation profiles assessed by immunophenotyping. Blood. 2005;106:1762–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-12-4631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schlaifer D, Krajewski S, Galoin S, Rigal-Huguet F, Laurent G, Massip P, et al. Immunodetection of apoptosis-regulating proteins in lymphomas from patients with and without human immunodeficiency virus infection. Am J Pathol. 1996;149:177–85. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Morton LM, Kim CJ, Weiss LM, Bhatia K, Cockburn M, Hawes D, et al. Molecular characteristics of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in human immunodeficiency virus-infected and -uninfected patients in the pre-highly active antiretroviral therapy and pre-rituximab era. Leuk Lymphoma. 2014;55:551–7. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2013.813499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Copie-Bergman C, Gaulard P, Leroy K, Briere J, Baia M, Jais JP, et al. Immunofluorescence in situ hybridization index predicts survival in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated with R-CHOP: a GELA study. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:5573–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.7058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]