Abstract

Objectives

Age limits for kidney transplantation (KT) have expanded significantly in recent years, yet outcomes in older recipients remain poorly understood. The goal of this study was to estimate relative mortality and death-censored graft loss by year of KT between 1990–2011.

Design

Cohort study.

Setting

All KT recipients in the United States as reported to the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients (SRTR).

Participants

30,207 KT recipients aged ≥65 at the time of transplantation.

Measurements

Mortality and death-censored graft loss ascertained through center report, linkage to Social Security Death Master File, and linkage to Medicare.

Results

Older adults currently represent 18.4% of KT recipients, a 5-fold rise from 3.4% in 1990; similar increases were noted for both deceased (5.4-fold) and live donor (9.1-fold) transplants. Current recipients are not only older, but also more likely to be female, African American, have lengthier pre-transplant dialysis, have diabetes or hypertension, and receive marginal kidneys. Mortality for older deceased donor recipients between 2009–2011 was 57% lower (HR=0.43, 95%CI:0.33–0.56, P<0.001) than in 1990–1993; mortality for older live donor recipients was 50% lower (HR=0.50, 95%CI:0.36–0.68, P<0.001). Death-censored graft loss for older deceased donor recipients between 2009–2011 was 65% lower (HR=0.35, 95% CI:0.29–0.42, P<0.001) than in 1990–1993; death-censored graft loss for older live donor KT recipients was 59% lower (HR=0.41, 95%CI:0.24–0.70, P<0.001).

Conclusion

Despite a major increase in number of older adults transplanted, and an expanding window of transplant eligibility, mortality and graft loss have decreased substantially for this recipient population. These trends are important to understand, both for patient counseling as well as transplant referral.

Keywords: Kidney transplantation, older adults, mortality, graft loss

INTRODUCTION

In 2011, there are over 230,000 older adults (aged ≥65) with end stage renal disease (ESRD), a substantial rise from approximately 50,000 in 1990.1 The incidence of ESRD is highest among older adults, and patients with ESRD are also living longer, further increasing the prevalence of ESRD in older adults disproportionately to the incidence. 2 However, very few older recipients undergo kidney transplantation (KT) relative to the burden of ESRD in this population. 3 We have previously identified that, of older adults with ESRD estimated to be excellent candidates for KT (in the highest quintile of KT outcomes, with predicted 3-year post-KT survival exceeding 87%), 76% lack access to transplantation. 4 In the past, KT outcomes were poor for older adults, 5–8 and we hypothesize that these historically poor outcomes have contributed to regressive attitudes towards transplantation of older patients and lesser pursuit of KT by older patients and their providers.

It is critical to understand trends in this patient population, especially in light of the rapid, profound expansion of both older KT candidates and recipients, as well as recent changes to kidney allocation policy. Older adults who receive KT are likely to have many comorbidities (including cardiovascular disease which is not captured by registries) and likely to receive kidneys that are associated with worse outcomes such as an expanded criteria donor (ECD) or donation after cardiac death (DCD) kidneys.3 Quantifying changes in mortality and graft loss for older KT recipients is not only important for clinical decision-making but also for informing policy changes. The new organ allocation policy considers candidate age (among other variables) in allocation priority.9 Understanding changes in survival over time will be important for organ allocation in older KT candidates, a group that has recently experienced improved survival after KT. If organ allocation priority for older candidates is based on old, outdated data (in other words, if the risk associated with age in the prediction model is estimated based on outdated data), older KT candidates may be denied organs because this population had poor survival in the past.

To inform clinical practice and policy changes, the main goals of this study were to characterize the changing landscape of transplantation in older adults, to evaluate trends in KT mortality and death-censored graft loss for older adults over time, and to identify risk factors unique to older adults.

METHODS

This study used data from the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients (SRTR), a national registry of all solid organ transplants. The SRTR includes data on all donors, wait-listed candidates, and transplant recipients in the United States, submitted by the members of the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN), and has been described elsewhere. Each transplant center uniformly reports recipient, donor and transplant factors. The Health Resources and Services Administration, US Department of Health and Human Services, provided oversight to the activities of the OPTN and SRTR contractors. As is standard with SRTR data, mortality and graft loss were augmented through linkage with the Social Security Death Master File, data from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), and waitlist data. Graft loss was defined as irreversible graft failure signified by return to long-term dialysis (ascertained from CMS), listing for a KT (ascertained from SRTR) or re-transplantation (ascertained from SRTR).

Adult kidney-only transplant recipients between January 1, 1990 and December 31, 2011, were identified using data from SRTR. For comparison of outcomes over time, the year of KT was grouped into 7three-year categories; for the sake of stability of the statistical models, we increased the size of the reference group (earliest time category) by one year. All models were stratified by donor type (living or deceased), age (older vs. younger), and outcome (death and death-censored graft loss).

Kaplan-Meier methods were used to estimate the 1, 3, and 5-year patient, death-censored graft survival, and all cause graft loss (death or graft loss) per stratum. As a sensitivity analysis, cumulative incidence of graft loss (treating death as a competing event) was estimated, using the nonparametric methods of Lin, by summing up to time t the function S(t-1) * h′(t), where S(t-1) is the overall survival function and h′ (t) is the cause-specific hazard at time t.10

Given changes in recipient demographics and comorbidities over time, Cox proportional hazards models were used to calculate adjusted changes in outcomes. To ensure proper risk adjustment, standard factors accounted for in the SRTR program specific reports11–14 were included in the models, including recipient factors (sex, age, race, body mass index (BMI), hepatitis C virus(HCV) status, previous KT, preemptive KT, cause of ESRD, peak panel reactive antibody (PRA), and number of years on dialysis), transplant factors (human leukocyte antibody (HLA) mismatches, use of pulsatile perfusion, cold ischemia time, and donor/recipient weight ratio) and donor factors (race, terminal creatinine, hypertension, ECD, diabetes, and DCD). Additionally, to determine whether improvements in mortality and death-censored graft loss differed by age (older vs. younger), sex and race, interactions between year of KT and these factors were explored using Wald tests in the stratified models.

All analyses were performed using STATA 12.1/SE (College Station, Texas), including the competing risks analyses using the stcompet package. Proportional hazards assumptions were confirmed by visual inspection of the complementary log-log plots and Schoenfeld residuals.

RESULTS

Study Population

Among 30,207 older KT recipients between 1990–2011, mean age at transplantation was 69.0 (standard deviation (SD)=3.6), 36.2% were female, 18.2% were African American, and 26.3% received a live donor kidney.

Increase in KT in Older Adults

The number of KTs performed in older adults increased monotonically throughout the study period (Figure 1A). In 2011, 2,829(18.4% of all KTs in 2011) older adults received KT, a 5-fold rise from the 295 (3.4% of all KTs in 1990) older recipients in 1990; in contrast, KT in younger adults only increased 1.5-fold during same time period. Older adults currently represent 21.0% of deceased donor KT recipients (a 5.4-fold-rise from 3.9% in 1990) and 13.7% of live donor KT recipients (a 9.1-fold rise from 1.5% in 1990). Furthermore, the overall age distribution of KT recipients shifted towards older age in more recent years (Figure 1B).

Figure 1. Older Kidney Transplant Recipients (A) and the Cumulative Distribution of Age at Kidney Transplantation (B), by Year of Transplantation.

(A) The number of older kidney transplantation (KT) recipients is shown as a bar (1st y-axis), and the percentage of total kidney transplant recipients in that year comprised of adults ages 65 and older is shown as a line (2nd y-axis).(B)For all transplant recipients between 1990–2011, the nested cumulative distribution of age at the time of kidney transplantation by year of transplantation is displayed. The further the curve is to the right, the older the age distribution at that time.

KT=kidney transplantation.

Changing Landscape of KT in Older Adults

In addition to the number of older adults transplanted, the characteristics of older KT recipients changed over time as well (Table 1). Between 1990–1993, among older KT recipients, 77.2% were 65–69 years old, 19.8% were 70–74, 2.6% were 75–79, and <1% were over 80. This shifted to a statistically significantly older distribution by 2009–2011:58.5%, 30.3%, 9.5% and 1.7%, respectively (P<0.001). Compared to older KT recipients in 1990–1993, those in 2009–2011 were more likely to be female (37.3% vs. 33.4%, P=0.004), African American (19.9% vs. 10.4%, P<0.001), have a longer time on dialysis prior to transplantation (2.5 vs. 1.9 years, P<0.001), have diabetes or hypertension as their cause of ESRD (diabetes: 35.4% vs. 14.8%; hypertension: 32.3% vs. 27.1%; P<0.001). Additionally, compared to older KT recipients in 1990–1993, those in 2009–2011 were more likely to have received a kidney from a live donor (27.9% vs. 10.3%, P<0.001), have received a kidney from an expanded criteria donor (35.6% vs. 11.5%, P<0.001) and have received a kidney from a donor after cardiac death (13.7% vs. 1.2% in 1994–1996, the first period in which DCD was captured by the OPTN, P<0.001) (Table 1), which was similar to the trends seen in younger adults.

Table 1.

Older Kidney Transplant Recipients, by Year of Transplantation

| All older KT recipients | 1990–1993 | 2009–2011 | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Recipient factors | ||||

| Age (mean ± SD) | 69.0 ± 3.6 | 67.9 ± 2.8 | 69.5 ± 3.8 | <0.001 |

| Female (%) | 36.2 | 33.4 | 37.3 | 0.004 |

| African American (%) | 18.2 | 10.4 | 19.9 | <0.001 |

| BMI (mean ± SD) | 27.3 ± 4.6 | 24.9 ± 4.1 | 28.1 ± 4.7 | <0.001 |

| HCV positive (%) | 3.0 | 2.4 | 2.8 | 0.9 |

| Years on dialysis (median [IQR]) | 2.3 [1.0–4.1] | 1.9 [1.1–3.1] | 2.5 [0.8–4.5] | <0.001 |

| Previous KT (%) | 4.3 | 4.3 | 5.0 | 0.3 |

| Peak PRA (median [IQR]) | 0 [0–12] | 3 [0–11] | 0 [0–21] | 0.005 |

| Cause of ESRD (%) | 0.001 | |||

| Diabetes | 31.4 | 14.8 | 35.4 | |

| Hypertension | 32.0 | 27.1 | 32.3 | |

| Polycystic kidney disease | 8.5 | 10.5 | 8.3 | |

| Glomerulonephritis | 15.8 | 29.4 | 12.2 | |

| Tubulo-interstitial disease | 3.0 | 3.4 | 2.9 | |

| Other | 9.2 | 14.7 | 8.8 | |

| KT factors | ||||

| 0 HLA mismatches (%) | 8.5 | 5.7 | 6.3 | 0.4 |

| Kidney pumped (%)* | 27.0 | 10.9 | 41.9 | <0.001 |

| Cold ischemia time(median [IQR])* | 18 [13–24] | 23 [16–31] | 17 [11–30] | <0.001 |

| Different DSA (%)* | 29.4 | 32.8 | 23.3 | <0.001 |

| Donor factors | ||||

| Live donor KT (%) | 26.3 | 10.3 | 27.9 | <0.001 |

| Donor age (mean ± SD) | 43.8 ± 16.3 | 35.9 ± 17.4 | 45.6 ± 15.5 | <0.001 |

| White race (%) | 75.8 | 82.9 | 73.2 | <0.001 |

| Donation after cardiac death (%)* | 7.7 | 1.2** | 13.7 | <0.001 |

| Expanded criteria donor (%)* | 32.2 | 11.5 | 35.6 | <0.001 |

For deceased donors

For 94–96 (First year donation after cardiac death was reliably recorded)

The P values compares the mean ± SD (or median (IQR))/% of each recipient, donor, and transplant factor between 1990–1993 and 2009–2011.

KT=kidney transplantation. SD=standard deviation. BMI=body mass index. HCV=hepatitis C virus. IQR=inter-quartile range. PRA=panel reactive antibody. ESRD=end stage renal disease. DSA=donor service area. HLA=human leukocyte antigen.

Patient Survival Over Time

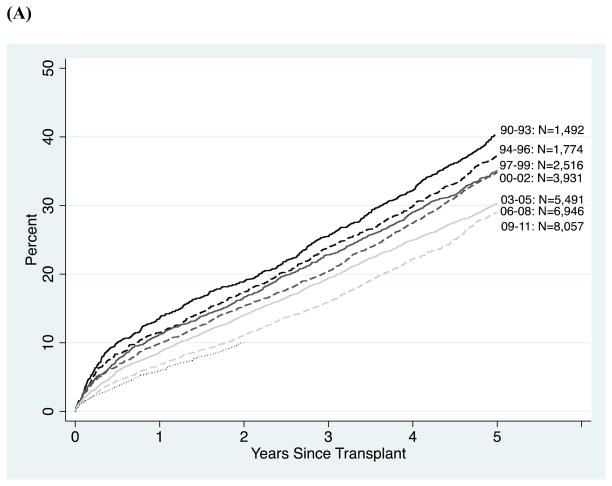

Survival in older adults improved steadily over time (Figure 2A). The 1-, 3- and 5-year unadjusted patient survival for deceased donor KT recipients improved, despite a much higher risk phenotype in recent years, from 86% at 1-year for recipients transplanted in 1990–1993 to 94% at 1-year for recipients transplanted in 2009–2011; from 74% at 3-years for recipients transplanted in 1990–1993 to 82% at 3-years for recipients transplanted in 2006–2008; and from 59% at 5-years for recipients transplanted in 1990–1993 to 67% at 5-years for recipients transplanted in 2006–2008 (Table 2A). For recipients aged 75 and older at the time of transplantation, the 1-, 3- and 5-year unadjusted patient survival for deceased donor KT recipients improved from 79% at 1-year for recipients transplanted in 1990–1993 to 89% at 1-year for recipients transplanted in 2009–2011; from 64% at 3-years for recipients transplanted in 1990–1993 to 76% at 3-years for recipients transplanted in 2006–2008; and from 50% at 5-years for recipients transplanted in 1990–1993 to 58% at 5-years for recipients transplanted in 2006–2008. Similarly, the 1-, 3- and 5-year unadjusted patient survival for live donor KT recipients improved from 87% at 1-year for recipients transplanted in 1990–1993 to 97% at 1-year for recipients transplanted in 2009–2011; from 79% at 3-years for recipients transplanted in 1990–1993 to 90% at 3-years for recipients transplanted in 2006–2008; and from 68% at 5-years for recipients transplanted in 1990–1993 to 81% at 5-years for recipients transplanted in 2006–2008 (Table 2A).

Figure 2. Mortality (A), Death-Censored Graft Loss (B), and All Cause Graft Loss (Death or Mortality) (C) Among Older Kidney Transplantation Recipients, by Year of Transplant.

The year and number of older recipients are listed to the right of the curve. The curves for 2009–2011 stop at 2 years because only 2 years of available follow-up are available for this cohort of older KT recipients.

Table 2. Outcomes in Older Kidney Transplant Recipients, by Year of Transplant.

(A) Mortality;

(B) Death-Censored Graft Loss

(C) All Cause Graft Loss (Mortality or Graft Loss). Columns 2–6 represent older recipients; outcomes trends in younger recipients (column 7) are also shown for comparison.

| (A)

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deceased Donor (n=22,268)

|

||||||

| Patient Survival

|

||||||

| Year of KT | N | 1-year (%) | 3-year (%) | 5-year (%) | aHR (95% CI) Older adults1 | aHR (95% CI) Younger adults1 |

|

| ||||||

| 1990–1993 | 1,338 | 86 | 74 | 59 | Reference | Reference |

| 1994–1996 | 1,484 | 88 | 75 | 60 | 0.93 (0.74–1.16) | 0.91 (0.85–0.97) |

| 1997–1999 | 1,969 | 88 | 75 | 62 | 0.85 (0.67–1.08) | 0.79 (0.73–0.84) |

| 2000–2002 | 2,713 | 88 | 77 | 61 | 0.80 (0.63–1.02) | 0.72 (0.67–0.78) |

| 2003–2005 | 3,852 | 90 | 78 | 66 | 0.69 (0.53–0.85) | 0.60 (0.56–0.65) |

| 2006–2008 | 5,100 | 92 | 82 | 67 | 0.57 (0.46–0.73) | 0.48 (0.44–0.52) |

| 2009–2011 | 5,812 | 94 | - | - | 0.43 (0.33–0.56) | 0.41 (0.37–0.46) |

| Live Donor (n=7,939)

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient Survival

|

||||||

| Year of KT | N | 1-year (%) | 3-year (%) | 5-year (%) | aHR (95% CI) Older adults2 | aHR (95% CI) Younger adults2 |

|

| ||||||

| 1990–1993 | 154 | 87 | 79 | 68 | Reference | Reference |

| 1994–1996 | 290 | 93 | 84 | 76 | 1.06 (0.85–1.32) | 0.97 (0.92–1.02) |

| 1997–1999 | 547 | 93 | 86 | 74 | 1.03 (0.83–1.28) | 0.83 (0.78–0.87) |

| 2000–2002 | 1,218 | 94 | 86 | 75 | 0.88 (0.71–1.08) | 0.76 (0.71–0.80) |

| 2003–2005 | 1,639 | 95 | 88 | 79 | 0.71 (0.57–0.89) | 0.60 (0.56–0.64) |

| 2006–2008 | 1,846 | 97 | 90 | 81 | 0.58 (0.45–0.74) | 0.50 (0.46–0.55) |

| 2009–2011 | 2,245 | 97 | - | - | 0.50 (0.36–0.68) | 0.38 (0.32–0.44) |

| (B) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deceased Donor (n=22,268)

|

||||||

| Death-Censored Graft Survival

|

||||||

| Year of KT | N | 1-year (%) | 3-year (%) | 5-year (%) | aHR (95% CI) Older adults3 | aHR (95% CI) Younger adults3 |

|

| ||||||

| 1990–1993 | 1,338 | 89 | 85 | 80 | Reference | Reference |

| 1994–1996 | 1,484 | 91 | 87 | 82 | 0.77 (0.66–0.90) | 0.88 (0.85–0.90) |

| 1997–1999 | 1,969 | 92 | 87 | 81 | 0.76 (0.65–0.88) | 0.76 (0.73–0.78) |

| 2000–2002 | 2,713 | 92 | 88 | 83 | 0.65 (0.56–0.76) | 0.70 (0.67–0.72) |

| 2003–2005 | 3,852 | 93 | 89 | 84 | 0.56 (0.48–0.65) | 0.61 (0.59–0.64) |

| 2006–2008 | 5,100 | 94 | 90 | 85 | 0.47 (0.40–0.55) | 0.51 (0.49–0.53) |

| 2009–2011 | 5,812 | 93 | - | - | 0.35 (0.29–0.42) | 0.39 (0.37–0.42) |

| Live Donor (n=7,939)

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Death-Censored Graft Survival

|

||||||

| Year of KT | N | 1-year (%) | 3-year (%) | 5-year (%) | aHR (95% CI) Older adults4 | aHR (95% CI) Younger adults4 |

|

| ||||||

| 1990–1993 | 154 | 89 | 85 | 80 | Reference | Reference |

| 1994–1996 | 290 | 91 | 87 | 82 | 0.96 (0.61–1.51) | 1.03 (0.98–1.08) |

| 1997–1999 | 547 | 92 | 87 | 81 | 0.77 (0.50–1.19) | 0.91 (0.86–0.96) |

| 2000–2002 | 1,218 | 92 | 88 | 83 | 0.73 (0.48–1.10) | 0.85 (0.81–0.90) |

| 2003–2005 | 1,639 | 93 | 89 | 84 | 0.69 (0.45–1.06) | 0.78 (0.74–0.83) |

| 2006–2008 | 1,846 | 94 | 90 | 85 | 0.49 (0.31–0.78) | 0.65 (0.60–0.70) |

| 2009–2011 | 2,245 | 95 | - | - | 0.41 (0.24–0.70) | 0.46 (0.41–0.53) |

| (C) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deceased Donor (n=22,268)

|

||||||

| All Cause Graft Survival

|

||||||

| Year of KT | N | 1-year (%) | 3-year (%)(%) | 5-year | aHR (95% CI) Older adults3 | aHR (95% CI) Younger adults3 |

|

| ||||||

| 1990–1993 | 1,338 | 79 | 67 | 51 | Reference | Reference |

| 1994–1996 | 1,484 | 82 | 68 | 54 | 0.86(0.79–0.93) | 0.87 (0.85–0.89) |

| 1997–1999 | 1,969 | 82 | 68 | 56 | 0.78(0.72–0.84) | 0.76 (0.74–0.78) |

| 2000–2002 | 2,713 | 83 | 70 | 55 | 0.72(0.66–0.78) | 0.70 (0.68–0.72) |

| 2003–2005 | 3,852 | 85 | 72 | 60 | 0.60(0.55–0.66) | 0.60 (0.58–0.62) |

| 2006–2008 | 5,100 | 88 | 76 | 62 | 0.51(0.47–0.56) | 0.49 (0.47–0.51) |

| 2009–2011 | 5,812 | 89 | - | - | 0.39(0.35–0.44) | 0.39 (0.37–0.42) |

| Live Donor (n=7,939)

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Cause Graft Survival

|

||||||

| Year of KT | N | 1-year (%) | 3-year (%) | 5-year (%) | aHR (95% CI) Older adults4 | aHR (95% CI) Younger adults4 |

|

| ||||||

| 1990–1993 | 154 | 83 | 77 | 66 | Reference | Reference |

| 1994–1996 | 290 | 90 | 79 | 70 | 1.11(0.89–1.38) | 1.01 (0.97–1.05) |

| 1997–1999 | 547 | 92 | 84 | 71 | 1.05(0.85–1.30) | 0.89 (0.85–0.92) |

| 2000–2002 | 1,218 | 92 | 83 | 71 | 0.91(0.74–1.12) | 0.83 (0.79–0.86) |

| 2003–2005 | 1,639 | 94 | 85 | 75 | 0.75(0.61–0.94) | 0.73 (0.69–0.76) |

| 2006–2008 | 1,846 | 95 | 89 | 78 | 0.60(0.47–0.76) | 0.61 (0.57–0.64) |

| 2009–2011 | 2,245 | 95 | - | - | 0.54(0.40–0.72) | 0.44 (0.40–0.49) |

Note: Adjusted hazard ratios (aHR) of patient mortality and death-censored graft loss over time (relative to 1990–1993) were estimated using Cox models, adjusting for recipient, donor, and transplant factors as specified below.

recipient factors (sex, age, race, BMI, HCV status, previous KT, preemptive KT, cause of ESRD, peak PRA, history of cancer and number of years on dialysis), transplant factors (HLA mismatches, cold ischemia time, donor/recipient weight ratio, kidney pumped, different DSA and insurance type) and donor factors (race, age, terminal creatinine, hypertension, ECD, DCD, and diabetes).

recipient factors (sex, age, race, BMI, HCV status, previous KT, preemptive KT, cause of ESRD, peak PRA, and number of years on dialysis), transplant factors (HLA mismatches and insurance type) and donor factors (race, age, and related).

recipient factors (sex, age, race, BMI, HCV status, previous KT, preemptive KT, cause of ESRD, peak PRA, and number of years on dialysis), transplant factors (HLA mismatches, cold ischemia time, donor/recipient weight ratio, kidney pumped, different DSA and insurance type) and donor factors (race, age, terminal creatinine, hypertension, ECD, DCD, diabetes, and stroke as the cause of death).

recipient factors (sex, age, race, BMI, HCV status, previous KT, cause of ESRD, and peak PRA), transplant factors (HLA mismatches, cold ischemia time, donor/recipient weight ratio, and insurance type) and donor factors (race, age, and related).

KT=kidney transplantation. BMI=body mass index. HCV=hepatitis C virus. PRA=panel reactive antibody. ESRD=end stage renal disease. HLA=human leukocyte antigen.

After adjusting for those comorbidities captured by the SRTR, mortality for older deceased donor KT recipients for recipients transplanted in 2009–2011 was 57%lower (adjusted hazard ratio(HR)=0.43, 95% CI: 0.33–0.56, P<0.001); similarly, mortality for older live donor KT recipients was 50% lower (adjusted HR=0.50, 95% CI: 0.36–0.68, P<0.001). In recipients 75 and older, the adjusted risk of mortality for deceased donor KT recipients for recipients transplanted in 2009–2011 was 63% lower (adjusted HR=0.37, 95% CI: 0.23–0.60, P<0.001). The improvement over time in patient survival for older KT recipients was statistically similar to the improvement observed in younger KT recipients (deceased donor recipients P for interaction=0.23 and live donor recipients P for interaction=0.10).

Patient Survival Over Time: Sex/Race Interactions

For older deceased donor recipients, survival improved over time equally for men and women (P=0.46) as well as for Caucasian and African American KT recipients (P=0.77). For live donor recipients, survival improved equally for men and women (P=0.75). However, older African American recipients had a greater improvement in survival over time (P=0.01) than older Caucasian recipients: older African American live donor KT recipients saw an 85% decrease in mortality between 1990–1993 and 2009–2011 (adjusted HR=0.15, 95% CI: 0.05–0.47, P<0.001), while Caucasians saw only a 46% decrease in mortality (adjusted HR=0.54, 95% CI: 0.38–0.75, P<0.001).

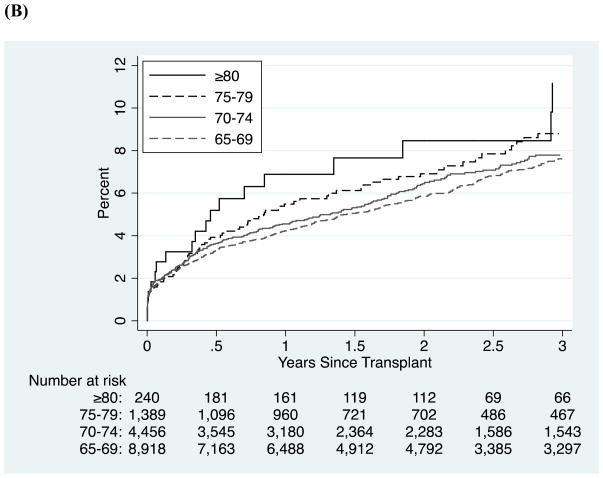

Graft Survival Over Time

Graft survival in older adults also improved steadily over time (Figure 2B). The 1-, 3- and 5-year unadjusted death-censored graft survival for deceased donor KT recipients, despite use of higher risk donors in recent years, improved from 89% at 1-year for recipients transplanted in 1990–1993 to 93% at 1-year for recipients transplanted in 2009–2011; from 85% at 3-years for recipients transplanted in 1990–1993 to 90% at 3-years for recipients transplanted in 2006–2008; and from 80% for recipients transplanted in 1990–1993 at 5-years to 85% at 5-years for recipients transplanted in 2006–2008 (Table 2B). Similarly, the 1-, 3- and 5-year unadjusted death-censored graft survival for live donor KT recipients improved from 89% at 1-year for recipients transplanted in 1990–1993 to 95% at 1-year for recipients transplanted in 2009–2011; from 85% at 3-years for recipients transplanted in 1990–1993 to 90% at 3-years for recipients transplanted in 2006–2008; and from 80% at 5-years for recipients transplanted in 1990–1993 to 85% at 5-years for recipients transplanted in 2006–2008 (Table 2B). Inferences were similar for all cause graft loss (Table 2C and Figure 2C). The 1-, 3- and 5-year unadjusted death-censored graft survival for deceased donor KT recipients improved from 90% at 1-year for recipients transplanted in 1990–1993 to 93% at 1-year for recipients transplanted in 2009–2011; from 87% at 3-years for recipients transplanted in 1990–1993 to 89% at 3-years for recipients transplanted in 2006–2008; and from 83% for recipients transplanted in 1990–1993 at 5-years to 86% at 5-years for recipients transplanted in 2006–2008. There were too few live donor recipients aged 75 and older in 1990–1993 to compare graft survival across time.

Death-censored graft loss for older deceased donor KT recipients for recipients transplanted in 2009–2011 was 65% lower (adjusted HR=0.35, 95%CI:0.29–0.42, P<0.001) than for recipients transplanted in 1990–1993; similarly, death-censored graft loss for older live donor KT recipients was 59% lower (adjusted HR=0.41, 95%CI:0.24–0.70, P<0.001). In recipients 75 and older, the adjusted risk of death-censored graft loss for deceased donor KT recipients for recipients transplanted in 2009–2011 was 57% lower (adjusted HR=0.43, 95% CI: 0.18–1.00, P=0.05). The improvement over time in death-censored graft survival for older KT recipients was statistically similar to the improvement observed in younger KT recipients (deceased donor recipients P for interaction=0.07 and live donor recipients P for interaction=0.20).

Death-Censored Graft Survival Over Time: Sex/Race Interactions

Older women who received a deceased donor kidney had a greater improvement in death-censored graft survival (P=0.01) than older men: older female deceased donor KT recipients saw a 72% decrease in graft loss between 1990–1993 and 2009–2011 (adjusted HR=0.28, 95% CI: 0.21–0.39, P<0.001), while older men only saw a 60%decrease (adjusted HR=0.40, 95% CI: 0.31–0.51, P<0.001). Additionally, older Caucasian deceased donor recipients had a greater improvement in death-censored graft survival over time (P=0.02) than older African American recipients: older Caucasian deceased donor KT recipients saw a 66% decrease in graft loss between 1990–1993 and 2009–2011 (adjusted HR=0.34, 95% CI: 0.28–0.42, P<0.001), while African American saw only a 57% decrease in graft loss (adjusted HR=0.43, 95% CI: 0.28–0.66, P<0.001). For older live donor recipients, death-censored graft survival improved over time equally for men and women (P=0.45) as well as for Caucasian and African American KT recipients (P=0.80).

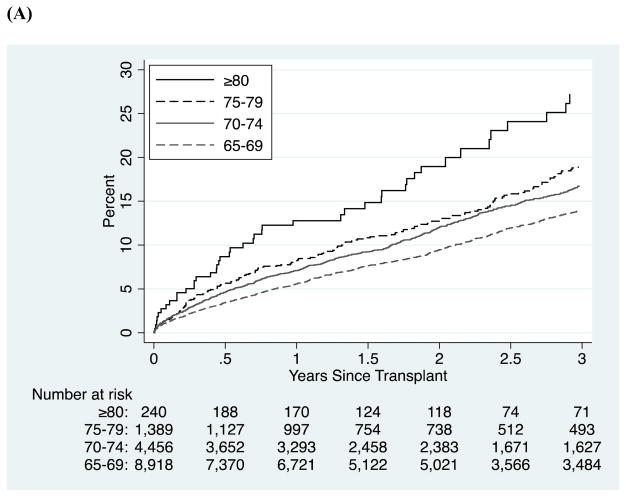

Age Strata over 65

Among recent (2006–2011) older KT recipients, mortality was worse in the older age strata as expected (P<0.001, Figure 3A). Nonetheless, outcomes were quite good even for the highest age groups: for deceased donor recipients, 3-year survival was 84% for those aged 65–69, 81% for those aged 70–74, 79% for those aged 75–80, and 70% for those aged 80 and older, and the corresponding survivals for live donor recipients were 91%, 90%, 86%, and 87%. Death-censored graft survival, on the other hand, was relatively constant across ages in both censored (P=0.7, Figure 3B) and competing risks (Figure 3C) analyses: for deceased donor recipients, 3-year death-censored graft survival was 91% for those aged 65–69, 90% for those aged 70–74, 89% for those aged 75–80, and 87% for those aged 80 and older, and the corresponding survivals for live donor recipients were 91%, 90%, 86%, and 87%.

Figure 3. Mortality (A), Death-Censored Graft Loss (B), and Cumulative Incidence of Graft Loss (C) for Older Kidney Transplant Recipients between 2006–2011, by Age.

Mortality and death-censored graft loss were estimated using Kaplan-Meier methods. The cumulative incidence of graft loss was estimated using a nonparametric method which treats death as a competing risk.

DISCUSSION

This national study of more than 30,000 older KT recipients characterizes a changing landscape of transplantation in older adults with increasing numbers of transplants performed, a wider window of acceptable risk, and substantially improving outcomes. Older adults currently represent 18.4% of KT recipients, a 5-fold rise from in 1990. Clinically meaningful differences in recent older recipients include even older age than in previous years, higher proportion of African Americans, higher BMI, more time on dialysis, and higher prevalence of diabetes or hypertension as the primary cause of ESRD; furthermore, recent older recipients had a higher proportion of DCD and ECD donors. Despite a major increase in number of older adults transplanted, and the transplantation of more high-risk older adults, patient and death-censored graft survival have improved since 1990. Mortality for older recipients between 2009–2011 was 57% (deceased donor) and 50% (live donor) lower than in 1990–1993; similarly, death-censored graft loss was 59% lower (both deceased and live donor). Additionally, even outcomes in patients over the age of 80 were surprisingly good (3-year 70% survival and 87% death-censored graft survival for deceased donor recipients, and 3-year 87% survival and 87% death-censored graft survival for live donor recipients).

Our findings reinforce evidence that, in the modern era of transplantation, appropriately selected older adults with ESRD who receive a KT have a survival benefit over those who remain on dialysis.3,15–22 Furthermore, our findings show that improvements in patient mortality and death-censored graft loss among older adults occurred in all sex and race strata and this improvement in outcomes was statistically similar to what was observed in younger KT recipients. Interestingly, African American recipients of live donor transplants had a substantially greater improvement in mortality over time compared with Caucasians.

The strengths of this study include a large, national cohort of KT recipients dating back to 1990, making possible analyses of the impact of year, sex, race, and their interactions on KT outcomes. This study is limited by the variables that are available for analysis by SRTR; specifically, more granular ascertainment of comorbidities is not available. However, there are more high-risk older KT recipients in recent years, so it is highly unlikely that adjusting for comorbidities would explain the observed improvement in recent years (in fact, it is likely that the adjusted improvement in recent years is even more pronounced than we identified, because of the likely higher prevalence of latent comorbidities).

In conclusion, there is an improving landscape for KT in older adults. The findings that KT is an expanding treatment option for older adults, and that outcomes in these patients have greatly improved over the last two decades, are important for all providers caring for older adults with ESRD, especially given the increase in number of older adults with ESRD. National registry data should consider collecting measures specific to older adults, including cognitive function, frailty and functional status to improve risk prediction in older recipients. Discussions about KT referral occur in the general community and only older adults who are encouraged to pursue KT and referred to a transplant center will have the opportunity for assessment and possible transplantation. Information about excellent recent KT outcomes for all older adults-- even those with advanced age --needs to be disseminated to both patients and providers.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by NIH grant R01AG042504 (PI: Dorry Segev). Mara McAdams-DeMarco was supported by the American Society of Nephrology Carl W. Gottschalk Research Scholar Grant and Johns Hopkins University Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center, National Institute on Aging (P30-AG021334) and K01AG043501 from the National Institute on Aging. Megan Salter was supported by T32AG000247 from the National Institute on Aging. The data reported here have been supplied by the Minneapolis Medical Research Foundation as the contractor for the SRTR. The interpretation and reporting of these data are the responsibility of the author(s) and in no way should be seen as an official policy of or interpretation by the SRTR or the U.S. Government.

Sponsor’s Role: The sponsor had no role in the design, methods, subject recruitment, data collection, analysis or preparation of paper.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: Authors have no conflict of interest to report.

Author Contributions: All authors contributed: 1) to the conception and design or acquisition of data or analysis and interpretation of the data; 2) drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content; and 3) final approval of the version to be published.

References

- 1.United States Renal Data System. 2012 Annual Data Report: Atlas of Chronic Kidney Disease and End-Stage Renal Disease in the United States. Bethesda: National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eggers PW. The aging pandemic: Demographic changes in the general and end-stage renal disease populations. SemNeph. 2009;29:551–554. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2009.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huang E, Segev DL, Rabb H. Kidney transplantation in the elderly. Semin Nephrol. 2009;29:621–635. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2009.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grams ME, Kucirka LM, Hanrahan CF, et al. Candidacy for kidney transplantation of older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60:1–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03652.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Takiff H, Mickey MR, Terasaki PI. Factors important in 10-year kidney transplant survival. Clin Transpl. 1986:157–164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kjellstrand CM. Age, sex, and race inequality in renal transplantation. Arch Intern Med. 1988;148:1305–1309. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Molnar MZ, Streja E, Kovesdy CP, et al. Age and the associations of living donor and expanded criteria donor kidneys with kidney transplant outcomes. Am J Kidney Dis. 2012;59:841–848. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2011.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kwon OJ, Lee HG, Kwak JY. The impact of donor and recipient age on the outcome of kidney transplantation. Transp Proc. 2004;36:2043–2045. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2004.07.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Organ Procurement and Transplant Network HRSA, editor. Proposal to Substantially Revise the National Kidney Allocation System (Kidney Transplant Committee) 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lin DY. Non-parametric inference for cumulative incidence functions in competing risks studies. Stat Med. 1997;16:901–910. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19970430)16:8<901::aid-sim543>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. [Accessed March 1, 2013];Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients Risk Model Documentation, Adult: Kidney, Living Donor, Adult, Three-Year Patient Survival. 2013 Available at: http://www.srtr.org/csr/current/Centers/201206/modtabs/Risk/KIADL3P.pdf.

- 12. [Accessed March 1, 2013];Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients Risk Model Documentation, Adult: Kidney, Deceased Donor, Adult, Three-Year Graft Survival. 2013 Available at: http://www.srtr.org/csr/current/Centers/201206/modtabs/Risk/KIADC3G.pdf.

- 13. [Accessed March 1, 2013];Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients Risk Model Documentation, Adult: Kidney, Living Donor, Adult, Three-Year Graft Survival. 2013 Available at: http://www.srtr.org/csr/current/Centers/201206/modtabs/Risk/KIADL3G.pdf.

- 14.Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients Risk Model Documentation, Adult: Kidney, Deceased Donor, Adult, Three-Year Patient Survival. 2013 Available at: http://www.srtr.org/csr/current/Centers/201206/modtabs/Risk/KIADC3P.pdf.

- 15.Accessed March 1, 2013.

- 16.Wolfe RA, Ashby VB, Milford EL, et al. Comparison of mortality in all patients on dialysis, patients on dialysis awaiting transplantation, and recipients of a first cadaveric transplant. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1725–1730. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199912023412303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oniscu GC, Brown H, Forsythe JL. How old is old for transplantation? Am J Transplant. 2004;4:2067–2074. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2004.00622.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oniscu GC, Brown H, Forsythe JL. How great is the survival advantage of transplantation over dialysis in elderly patients? Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2004;19:945–951. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfh022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rao PS, Merion RM, Ashby VB, et al. Renal transplantation in elderly patients older than 70 years of age: Results from the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients. Transplantation. 2007;83:1069–1074. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000259621.56861.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnson DW, Herzig K, Purdie D, et al. A comparison of the effects of dialysis and renal transplantation on the survival of older uremic patients. Transplantation. 2000;69:794–799. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200003150-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu C, Shapiro R, Tan H, et al. Kidney transplantation in elderly people: The influence of recipient comorbidity and living kidney donors. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:231–238. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01542.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schold JD, Meier-Kriesche HU. Which renal transplant candidates should accept marginal kidneys in exchange for a shorter waiting time on dialysis? Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;1:532–538. doi: 10.2215/CJN.01130905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Frei U, Noeldeke J, Machold-Fabrizii V, et al. Prospective age-matching in elderly kidney transplant recipients--a 5-year analysis of the Eurotransplant Senior Program. Am J Transplant. 2008;8:50–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2007.02014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]