Abstract

Background:

Women Veterans are a significant minority of users of the VA healthcare system, limiting provider and staff experience meeting their needs in environments historically designed for men. The VA is nonetheless committed to ensuring that women Veterans have access to comprehensive care in environments sensitive to their needs.

Objectives:

We sought to determine what aspects of care need to be tailored to the needs of women Veterans in order for the VA to deliver gender-sensitive comprehensive care.

Research Design:

Modified Delphi expert panel process.

Subjects:

Eleven clinicians and social scientists with expertise in women’s health, primary care, and mental health.

Measures:

Importance of tailoring over 100 discrete aspects of care derived from the Institute of Medicine’s definition of comprehensive care and literature-based domains of sex-sensitive care on a 5-point scale.

Results:

Panelists rated over half of the aspects of care as very-to-extremely important (median score 4+) to tailor to the needs of women Veterans. The panel arrived at 14 priority recommendations that broadly encompassed the importance of (1) the design/delivery of services sensitive to trauma histories, (2) adapting to women’s preferences and information needs, and (3) sex awareness and cultural transformation in every facet of VA operations.

Conclusions:

We used expert panel methods to arrive at consensus on top priority recommendations for improving delivery of sex-sensitive comprehensive care in VA settings. Accomplishment of their breadth will require national, regional, and local strategic action and multilevel stakeholder engagement, and will support VA’s national efforts at improving customer service for all Veterans.

Key Words: comprehensive care, women’s health, sex sensitivity, Veterans

The largest integrated health care delivery system in the United States, the Veterans Health Administration (VA), is responsible for delivering comprehensive care to nearly 9 million enrolled Veterans.1 Women are a substantial minority of those patients, approximately 6.5% of VA users, reflecting historically lower levels of military participation as well as gaps in knowledge of their VA benefits.2–4 However, they are now the fastest growing segment of new users, doubling their numbers in the past decade and projected to be 18% of the VA population by 2040.1,2

Delivering comprehensive care to women Veterans has posed significant challenges in a system that has been predominated by men.5 Lower female caseloads has translated into a workforce with limited exposure to women’s gender-specific care needs, resulting in gaps in clinical experience and frequent lack of recognition of women’s military service and exposures.6 Many VA facilities also do not deliver specialized women’s health care services on-site.7 Women Veterans are more likely to be seen by multiple providers in multiple sites, including community providers, to obtain needed care.8 Much higher rates of military sexual trauma (MST) among women Veterans using the VA also requires special attention to the capacity to deliver trauma-informed care in environments that ensure women’s safety, security, and dignity.9,10 The result has been a history of fragmented care among a vulnerable group of Veterans, whose VA care options have varied from facility-to-facility, in the face of persistent gender disparities in VA quality of care.11,12

Early solutions to these issues included the creation of model comprehensive women’s health centers in a handful of larger VAMCs linked to university settings to draw in women’s health clinical expertise.13 These centers were comparable in organization and mix of clinical services to the US Department of Health and Human Services’ Centers of Excellence in Women’s Health, but with one third of the patient volumes.13 These VA women-only clinics were designed to provide greater privacy, access to same-sex providers, integrated gynecology, mental health, and other services tailored to women Veterans’ needs. Subsequent adoption of women’s clinics in other VA facilities expanded 8-fold, though they were not as comprehensive as the original models.14

Delivering care that is more comprehensive (eg, integrated gynecology care) and gender sensitive is associated with important benefits. For example, VA facilities with women’s clinics outperform others on women’s ratings of access, continuity, and coordination,15 as well as overall quality, satisfaction, and gender appropriateness.16 Women Veterans in women’s clinics are more likely to report getting needed care, complete care, and follow-up care, and rate the privacy and comfort of the clinic environments as better than in traditional primary care clinics.17 Women Veterans seen in VA facilities that have adopted women’s clinics with female providers and also integrated gynecology care have reported perfect or nearly perfect ratings of their VA providers’ communication and knowledge.18 In fact, regardless of clinic type, women offered routine gynecologic care by VA providers are much less likely to split their care between VA and non-VA providers.19 Women from all military service eras rate colocated gynecologic and general health care as important.20 Not tailoring care to the needs of women has its own consequences as well, as women Veterans who perceive that VA providers are not gender sensitive are much more likely to delay or forgo needed care.21

As evidence has mounted, the VA released a new national VA Handbook that outlined requirements designed to ensure that women Veterans get care in comprehensive primary care clinics that include gender-specific services and integrated mental health care.22 Care must be delivered by a designated women’s health provider, trained and proficient in caring for women Veterans. Such providers must be located in 1 of 3 primary care clinic models, including separate women’s health centers, women’s clinics embedded in primary care clinics, or integrated primary care clinics with designated providers. The VA Handbook further codified expectations that all enrolled women Veterans obtain such “1-stop shopping” care “irrespective of where they are seen” and “regardless of the number of women Veterans utilizing a particular facility.”22

In this paper, we report on the results of a national expert panel designed to further advance delivery of gender-sensitive comprehensive care in the VA by defining what other aspects of care should be tailored to meet the needs of women Veterans. The panel focused broadly on the path a woman Veteran may take as she engages in care at the VA, from her first contact with the system to the care she receives thereafter.

METHODS

Conceptual Framework for Evaluating Gender-sensitive Comprehensive Care

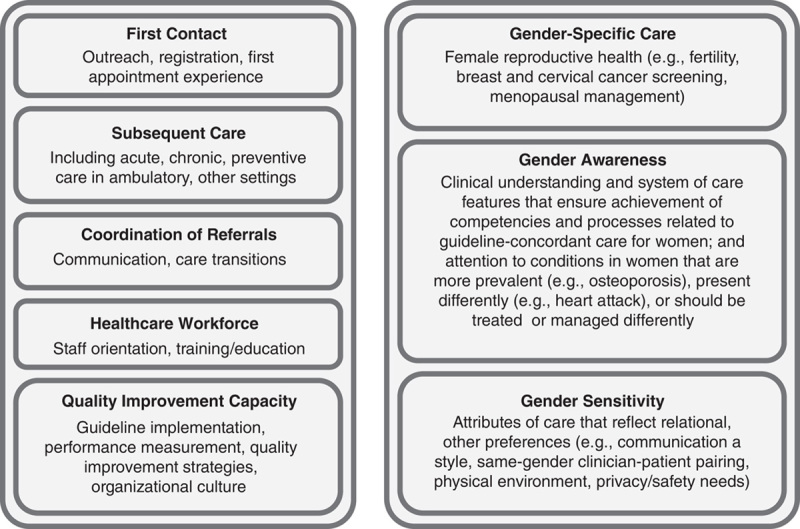

We integrated definitional elements of comprehensive care put forward by the Institute of Medicine (IoM) with aspects of gender-sensitive care culled from the published literature and expert opinion to arrive at domains of gender-sensitive comprehensive care for use in our expert panel (Fig. 1).

FIGURE 1.

Domains of gender-sensitive comprehensive care.

Comprehensive Care

Ensuring delivery of comprehensive care is central to the IoM recommendations for improving population health.23 IoM defines comprehensive care as everything from first contacts with the health care system, subsequent care for acute, chronic and preventive care, and coordination of the referrals within and across settings needed to deliver each aspect of care based on patient needs. Improving comprehensive care, in turn, requires explicit attention to the health care workforce and quality improvement capacity within which they deliver services.24

Gender-sensitive Care

The fragmentation of care that results from the often separate management of reproductive and nonreproductive health care needs for women has significantly complicated achievement of comprehensive care. The resulting “patchwork quilt with gaps” has contributed to significant gender disparities in care25 and bolstered recognition of the importance of advancing care that is gender sensitive.26–28 We examined the literature for domains of gender-sensitive care and interviewed selected subject matter experts outside the VA to identify discrete domains that spanned (1) gender-specific care (eg, female reproductive health services), (2) gender awareness (eg, clinical understanding and system of care features that acknowledge sex differences in the prevalence, presentation, and/or treatment of health conditions), and (3) sex sensitivity (eg, attributes of care that reflect relational and other preferences).

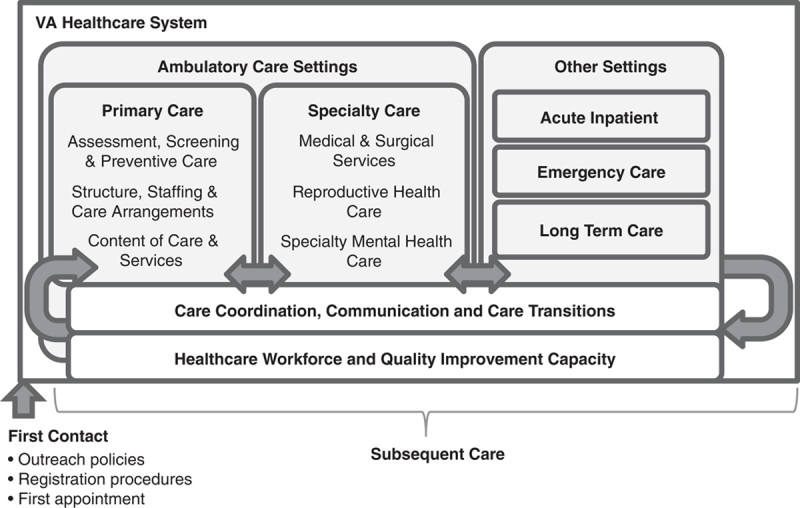

We then applied these domains to the VA healthcare system to arrive at our conceptual framework for evaluating aspects of gender-sensitive comprehensive care (Fig. 2). We integrated VA policies on primary care, women’s health, and mental health care delivery, including relevant guidance on VA’s patient-centered medical home model (Patient Aligned Care Teams or PACT). Aspects of care for other settings, such as emergency rooms and long-term care facilities, were not included. We specifically omitted aspects of emergency care because of recent completion of another expert panel focused exclusively on the resources and processes of care for women Veterans’ in VA emergency rooms.29 On the basis of the age distribution of women Veterans and their use of VA long-term care services, we also did not include aspects of extended care, with the exception of transfers from VA hospitals to nursing homes (as an aspect of care coordination). We also asked local VA managers and frontline women’s health clinicians to identify omissions and candidates for trimming.

FIGURE 2.

Conceptual framework for evaluating aspects of gender-sensitive comprehensive care.

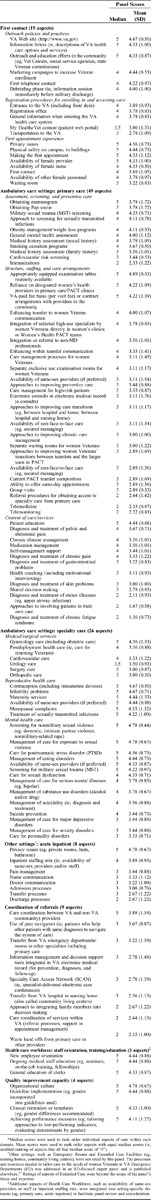

Table 1 contains the final aspects of care organized along domains from our conceptual framework: first contact (19 aspects), primary care (49 aspects), specialty care (20 aspects), acute inpatient care (8 aspects), coordination of referrals (9 aspects), health care workforce (3 aspects), and quality improvement capacity (4 aspects). First contact, primary care, and specialty care were further divided into subgroups; for example, first contact care included aspects for outreach policies and practices, registration procedures for enrolling in and accessing care, and first appointment experience.

TABLE 1.

Median Score Rank Ordered Final Expert Panel Ratings of Importance of Tailoring Aspects of Care to the Needs of Women Veterans*

Expert Panel Methods

We applied expert panel methods using a modified nominal group technique to come to consensus on the aspects of care that should be tailored to meet the needs of women Veterans in the context of seeking to achieve gender-sensitive comprehensive care.30 These highly structured meetings typically gather input from 9 to 12 relevant experts in ≥2 rounds of ratings of a series of items.30

Panelist Selection

We selected panelists on the basis of their knowledge of the patient population and the VA, with a focus on expertise in women’s health, primary care, and mental health care. National VA leaders in women’s health and mental health were recruited and also asked for nominations of experts in the field, seeking a multidisciplinary mix of panelists representing a regional and urban/rural distribution. We also identified a pool of experts in women’s health outside the VA.

We sent email invitations to prospective panelists until we successfully recruited 11 panelists (9 clinicians/2 nonclinicians, 10 VA/1 non-VA expert, 9 urban/2 rural). Almost all of the VA clinicians also had university appointments, with non-Veteran patient panels at their respective schools of medicine. Final panelists represented 7 states in all 4 VA regions and included expertise in general internal medicine, obstetrics-gynecology, family medicine, clinical psychology, epidemiology, and sociology. Travel costs for attendance at an in-person meeting in Washington, DC were covered for each panelist.

Panel Process

In round 1, panelists received emails containing key articles on gender-sensitive care and a prepanel rating form that asked panelists to rate how important it was for the VA to develop a tailored approach for each listed aspect of care for women Veterans. We used a 5-point Likert scale from “1” (not at all important) to “5” (extremely important). (A copy of the rating form is available on request.) In round 2, the panel met face-to-face with 2 panel moderators (E.M.Y./M.d.K.) in a day-long meeting (June 2012) to review aggregated panel ratings as a guide to discussion of areas of agreement and disagreement. After reviewing aggregated ratings and open-ended comments for each aspect of care, we presented the panel with their top-rated priorities overall and went through an iterative discussion allowing members to add elements only if an equal numbers were deleted. Discussion continued until a final list reflected group consensus (Table 2). In round 3, panelists rerated the same aspects of care to verify consensus with the final priority ratings.

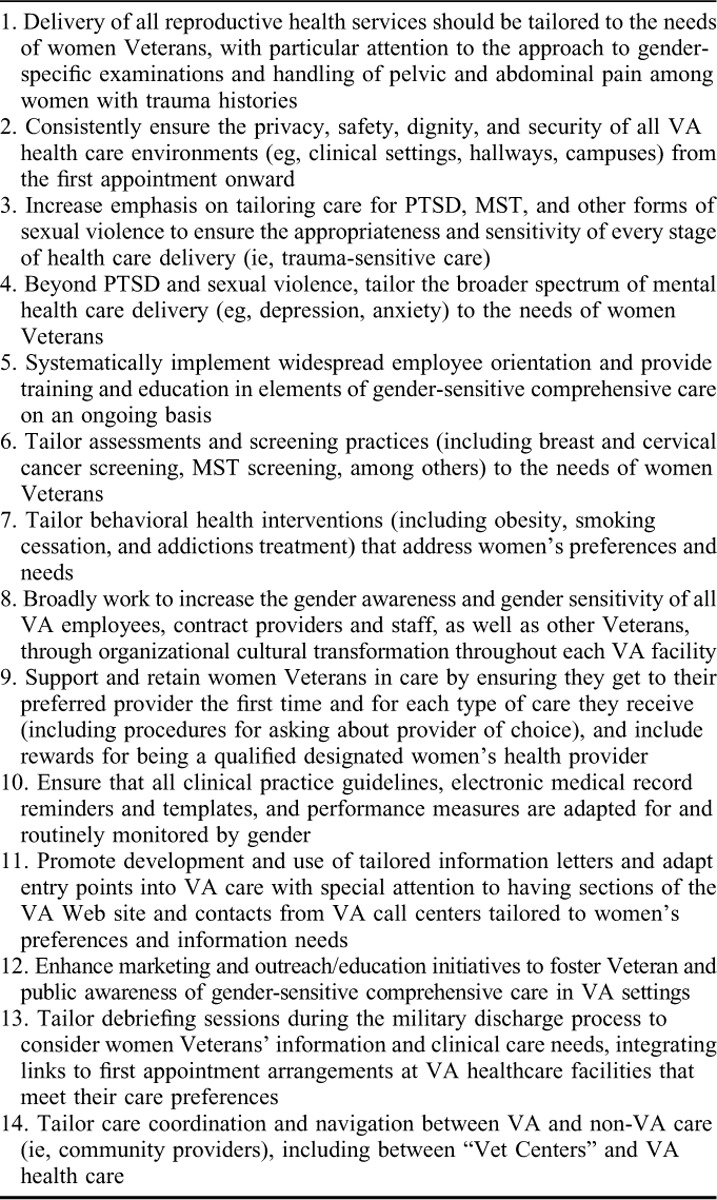

TABLE 2.

Priority Recommendations for Tailoring Aspects of Care to the Needs of Women Veterans to Achieve Gender-sensitive Comprehensive Care

Statistical Analysis

We calculated univariate statistics for the panel ratings of each aspect of care. We used a median score of ≥4.0 (very-to-extremely important) on the 5-point scale as the criterion for required tailoring to meet women Veterans’ needs and thus a key aspect for achieving gender-sensitive comprehensive care.

RESULTS

Expert Panel Ratings by Domain

Table 1 contains the rank ordered final expert panel ratings within each domain of gender-sensitive comprehensive care. Overall, 68 of the 118 aspects (58%) had median scores that met our criterion for tailoring.

First Contact

Overall, 16 of the 19 aspects (84%) of women Veterans’ first contact with the VA healthcare system achieved a median score of ≥4 (ie, met criterion). All outreach policies and practices require tailoring to the needs of women Veterans, including VA Web site, information letters sent out to women describing VA healthcare options, outreach/education in the community, marketing campaigns, first telephone contacts, and the debriefing process following military discharge. Panelists also recommended tailoring registration procedures, attention to the main entrances to VA facilities and registration office, and all general information provided when entering the VA healthcare system. First appointment experiences were seen as a critical opportunity for making optimal impressions on women Veterans new to the VA. Top priorities included attention to privacy and physical safety on campus and in buildings, tailoring the processes for making the first appointment, as well as ensuring the availability of female providers and nurses.

Primary Care

Overall, 22 of the 49 aspects (45%) met criterion requiring tailoring. We organized primary care aspects into 3 subdomains: (1) assessment, screening, and preventive care (11 aspects); (2) structure, staffing, and care arrangements (25 aspects); and (3) content of care/services (13 aspects).

Eight of the 11 aspects (73%) on assessment, screening, and preventive care scored 4+. Most focused on sex-specific screenings (eg, breast and cervical cancer screening) and sexual trauma/exposures (eg, MST, sexually transmitted infections). Others focused on health habits (eg, weight loss, smoking cessation) and approaches to assessment (eg, mental health and social history).

Nine of the 25 aspects (36%) of primary care structure, staffing, and care arrangements were rated as requiring tailoring. Structural aspects included availability of separate exclusive use examination rooms for women Veterans and routinely available and appropriately equipped examination tables. Staffing needs included reliance on designated women’s health providers in primary care/PACT clinics, integration of selected high-use specialists directly in women’s clinics or PACT teams, with integration or referral to non-MD professionals as needed. Attention to tailoring arrangements for women Veterans referred to community providers was also a priority. Ratings for tailoring care arrangements focused on enhancing PACT teamlet-to-women Veteran and within-teamlet communication, with enhanced care management.

Six of the 13 aspects (46%) of primary care content of care/services require tailoring. Chief among them was patient education, followed by special attention to diagnosis and treatment of pelvic and abdominal pain, chronic pain and gastrointestinal problems, chronic disease and medication management, and self-management support.

Specialty Care

Twenty of the 26 aspects (77%) of specialty care were rated as requiring tailoring. We organized specialty care into (1) medical/surgical services (6 aspects); (2) reproductive health care (6 aspects); and (3) mental health care (14 aspects). Half of the medical/surgical services aspects were recommended to be tailored, including gynecology, postdeployment, and cardiovascular care, while all aspects of reproductive health require tailoring based on final panel scores. Eleven of the 14 aspects of mental health care (78%) met our criterion for tailoring. Many of these aspects focused on sexual trauma/violence (screening, management of care for exposures) or sexual dysfunction, and also included care for posttraumatic stress disorder, eating disorders, serious mental illness, and substance use disorders. VA approaches to suicide prevention and management of suicidality were also rated as requiring tailoring to women Veterans’ needs.

Acute Inpatient Care

Two of the 8 aspects (25%) of inpatient care met our criterion and focused on privacy issues and inpatient staffing mix (ie, availability of same-sex providers and/or staff if preferred).

Coordination of Referrals

Only care coordination between VA and non-VA providers was rated as requiring tailoring (1 of the 8 aspects or 12%).

Health Care Workforce

All 3 aspects (100%) were rated as requiring tailoring: new employee orientation, ongoing medical staff education, and general education of clerks.

QI Capacity

All 4 aspects (100%) of QI capacity were also rated as requiring tailoring, and included attention to tailoring organizational culture, guideline implementation, clinical reminders/templates in the electronic medical record, and performance measurement (eg, evaluating determinants of sex differences).

Top Priorities for Achieving Gender-sensitive Comprehensive Care

After structured review of each domain, we presented the expert panel with their top-rated aspects of care across all domains and facilitated a final round of consensus development. Panelists worked collaboratively to recombine and distill several discrete aspects into broader recommendation statements, arriving at 14 consolidated priority recommendations for achieving gender-sensitive comprehensive care for women Veterans in the VA healthcare system (Table 2).

DISCUSSION

We used an expert panel process to evaluate the aspects of care that should be tailored to the needs of women Veterans to deliver gender-sensitive comprehensive care. Of over 100 discrete aspects of care, panelists rated over half of them as very-to-extremely important to tailor. Essential aspects spanned the need to tailor women’s first contacts with the VA healthcare system and their subsequent care in different VA settings, as well as the choice of community providers and the arrangements made to coordinate care between VA and community providers. The panel ratings suggest that meeting women Veterans’ needs will require tailoring the orientation, education, and training of the VA workforce to meet clinical care needs (eg, gender incorporated into guideline implementation) and to transform the organization’s culture to be more gender sensitive. Identifying strategies for offering access to same-sex providers and staff in all VA care settings if preferred by female patients will also be important. The panel ultimately came to consensus on 14 priority recommendations that broadly encompass the importance of (1) the design/delivery of services sensitive to women’s gender-specific care needs in the context of potential trauma histories, (2) adapting to women’s preferences and information needs, and (3) gender awareness and cultural transformation in every facet of VA operations.

Tailoring first contact experiences to the needs of women Veterans has important ramifications for the VA system, as recent evidence suggests high rates of attrition among new women Veteran VA users.31 Consistently ensuring the privacy, safety, and security of all entire VA campuses is essential, with explicit attention to building entrances and public spaces. One panelist mentioned a VA hospital where rows of waiting room chairs lined the main entrance, making women feel like they were “walking a gauntlet.” VA has also instituted a national call center for Veteran outreach, including tailored protocols for enrolling eligible women in VA care. However, the extent of tailoring of telephone protocols at local VAMC call centers is unknown.

Adapting primary care to the needs of women Veterans may be challenging on several levels.32 Although VA gender-specific preventive screening rates (eg, breast and cervical cancer screening) are higher than outside the VA33 and MST screening is nearly universal,34 tailoring smoking cessation and weight management programs based on women Veterans’ preferences has proved difficult.35 Consolidating care to a subset of designated providers has improved women’s experiences with VA primary care,36 yet limits opportunities for others to gain needed expertise. As women who have lower ratings of a VA’s gender-specific features of care are much more likely to leave VA, the VA can ill afford to move beyond the designated provider model until the volume of female patients hits some critical threshold.37 Establishing arrangements with community providers for care outside the VA must also be tailored, though recent legislation fostering such access does not take gender differences into account.38

We found that the panel ratings of importance of tailoring specialty care varied, perhaps as a result of gaps in knowledge of women Veterans’ chronic care needs.39 All aspects of reproductive health were rated highly, consistent with strategies for transforming VA reproductive health care delivery.40 Most aspects of mental health care also warrant tailoring, for example, to address gender differences postdeployment,41 while gender differences in detection and management of cardiovascular disease have resulted in lingering quality gaps in VA.42 More research is needed to examine aspects of sex-sensitive medical/surgical specialty and acute care.

Improving the gender sensitivity of the VA workforce, given generations caring for men, could prove challenging. Certainly, universal access to same-sex employees is unlikely, as federal hiring practices preclude use of sex as a criterion. The VA has instead focused on proficiency, which is arguably more important as women are not automatically embued with gender sensitivity by virtue of their sex. Establishing women’s health proficiency standards (ie, training, minimum patient volumes) has resulted in placement of designated providers in the vast majority of VA facilities.43 An evidence-based curriculum that improves VA provider/staff gender awareness has also been developed, and is ready for broad deployment.44 VAMCs also have Women Veterans Program Managers, who conduct “environmental rounds” and locally implement aspects of VA’s national culture change initiative (eg, “not every GI is a Joe”). Ongoing monitoring of women Veterans’ experiences with VA care should be used to determine the effectiveness of these efforts and inform future improvements.

Integrating gender in quality improvement efforts is also key. The VA already reports quality metrics by gender11,33 and has used them to reduce disparities.45 Greater attention to tailoring clinical guidelines, as suggested by the panel, is needed in areas with lingering disparities (eg, cardiovascular risk reduction, sex differences in lipid-lowering therapies).42,46 The VA’s electronic medical record should facilitate implementation once gender-tailored tools are developed and tested.

This work comes with important limitations. First, we focused on the VA healthcare system. While we incorporated experts with non-VA experience, experts in other settings or contexts may have generated different aspects of care to rate and arrived at different ratings. We also focused on women Veterans, whereas gender sensitivity is just as important for men. Results are also sensitive to panel composition,47 and would benefit from replication.

CONCLUSIONS

Improving our understanding of the complex interplay of sex and gender on the delivery and experience of health and health care is essential to reducing longstanding disparities and improving population health.26 This paper aims to add to that understanding through use of expert panel methods focused on women Veterans in the VA healthcare system, while broadly contributing to the conceptualization of gender-sensitive comprehensive care.

More specifically, these expert panel recommendations may serve as a quality improvement roadmap for improving delivery of gender-sensitive comprehensive care in VA settings. Acting on these recommendations will require multilevel engagement of a broad range of stakeholders at national, regional, and local levels, with special attention to effectively engaging the Veterans we serve in designing first contact and subsequent care so that the VA is no longer another “patchwork quilt.”48,49

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to acknowledge the technical and logistical support of their project team members, including Danielle Rose, PhD and Britney Chow, MPH, as well as the funding support of Dr Patricia Hayes, Chief Consultant of VA Women’s Health Services. The authors also would like to acknowledge the contributions of the members of the national expert panel, without whose time, input, and participation in consensus development this work would not have been possible. Panelists included Sonya Batten, PhD, Deputy Chief Consultant, Specialty Mental Health, Veterans Health Administration (VHA), Washington, DC; Sudha Bhoopalam, MD, Medical Director, Women Veterans Health Program, Hines VA Medical Center, Hines, IL; Megan Gerber, MD, Medical Director, Women’s Health, VA Boston Healthcare System, Jamaica Plains, MA; Howard Gordon, MD, Staff Physician (General Internist), Jesse Brown VA Medical Center, Chicago, IL; Sally Haskell, MD, Director of Comprehensive Women’s Health Care, Women’s Health Services, West Haven VA Medical Center, CT; Amanda Johnson, MD, Physician (Obstetrician-Gynecologist), Cheyenne VA Medical Center, Cheyenne, WY; Erin Krebs, MD, Core Investigator, Center for Chronic Disease Outcomes Research, and Women’s Health Medical Director, Minneapolis VA Medical Center, Minneapolis, MN; Melissa McNeil, MD, Staff Physician (General Internist) and Women’s Health Medical Director, VA Pittsburgh Healthcare System, Pittsburgh, PA; Margaret Mikelonis, RN, Deputy Field Director, Women’s Health Services, Tampa VA Medical Center, Tampa, FL; Sabine Oishi, PhD, MSPH, Health Science Specialist, VA HSR&D Center for the Study of Healthcare Innovation, Implementation and Policy, VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System, Sepulveda, CA; and Sarah Scholle, DrPH, Vice President, Research and Analysis, National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA), Washington, DC.

Footnotes

Supported by Women’s Health Services, Office of Patient Care Services, Veterans Health Administration, Washington, DC. M.d.K.’s effort was covered through a Gender Sensitive Medicine Postdoctoral Fellowship at Radboud University Medical Center, Njimegen, The Netherlands and the Hilly de Roever-Bonnet fund of The Dutch Society of Female Doctors. E.M.Y.’s effort was funded by a VA Health Services Research & Development Senior Research Career Scientist Award (Project # RCS 05-195).

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States government.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.US Department of Veterans Affairs. National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics. Statistics at a Glance (August 2014).Washington, DC: US Department of Veterans Affairs; Available at http://www.va.gov/vetdata/docs/Quickfacts/Homepage_slideshow_06_30_14.PDF. Accessed on November 15, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Frayne SM, Phibbs CS, Saechao F, et al. Sourcebook: Women Veterans in the Veterans Health Administration Volume 3: Sociodemographics, utilization, costs of care and health profiles. 2014Washington, DC: Veterans Health Administration. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Washington DL, Washington DL, Yano EM, et al. To use or not to use—Women veterans’ choices about VA health care use. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21suppl 3S11–S18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Washington DL, Kleimann S, Michelini AN, et al. Women veterans’ perceptions and decision-making about Veterans Affairs health care. Mil Med. 2007;172:812–817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Murdoch M, Bradley A, Mather S, et al. Women and war: what physicians should know. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21suppl 3S5–S10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yano EM, Hayes P, Wright S, et al. Integration of women veterans into VA quality improvement research efforts: what researchers need to know. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;1:56–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Washington DL, Caffrey C, Goldzweig C, et al. Availability of comprehensive women’s health care through Department of Veterans Affairs medical centers. Womens Health Issues. 2003;13:50–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Veterans Health Administration. Report of the Under Secretary for Health Work Group on Provision of Primary Care to Women Veterans. 2008Washington, DC: Women Veterans Health Strategic Health Care Group. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kimerling R, Street AE, Pavao J, et al. Military-related sexual trauma among Veterans Health Administration patients returning from Afghanistan and Iraq. Am J Public Health. 2010;100:1409–1412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.DeCandia CJ, Guarino K, Clervil R. Trauma-informed Care and Trauma-specific Services: A Comprehensive Approach to Trauma Intervention. 2014Washington, DC: American Institutes for Research. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Veterans Health Administration. Gender Differences in Performance Measures, Veterans Health Administration 2008-2011. 2012Washington, DC: Women Veterans Health Strategic Health Care Group. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bean-Mayberry BA, Yano EM, Brucker N, et al. Does sex influence immunization status for influenza and pneumonia in older veterans? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57:1427–1432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bean-Mayberry B, Yano EM, Bayliss N, et al. Federally funded comprehensive women’s health centers: leading innovation in women’s healthcare delivery. J Womens Health. 2007;16:1281–1290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yano EM, Goldzweig C, Canelo I, et al. Diffusion of innovation in women’s health care delivery: VA adoption of women’s health clinics. Womens Health Issues. 2006;16:226–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yano EM, Bean-Mayberry B, Washington DL. Impact of Practice Structure on the Quality of Care for Women Veterans. 2008Washington, DC: VA HSR&D Final Report (04-036). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Washington DL, Bean-Mayberry B, Mitchell MN, et al. Tailoring VA primary care to women veterans: association with patient-rated quality and satisfaction. Womens Health Issues. 2011;21supplS112–S119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bean-Mayberry BA, Chang CH, McNeil MA, et al. Patient satisfaction in women’s clinics versus traditional primary care clinics in the Veterans Administration. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18:175–181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bean-Mayberry BA, Chang C, McNeil MA, et al. Assuring high quality primary care for women: predictors of success. Womens Health Issues. 2006;1691:22–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bean-Mayberry B, Chang C, McNeil M, et al. Comprehensive care for women Veterans: indicators of dual use of VA and non-VA providers. JAMWA. 2004;59:192–197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Washington DL, Bean-Mayberry B, Hamilton AB, et al. Women veterans’ healthcare delivery preferences and use by military service era: findings from the National Survey of Women Veterans. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28suppl 2S571–S576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Washington DL, Bean-Mayberry B, Riopelle D, et al. Access to health care for women veterans: Delayed health care and unmet need. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26suppl 2655–661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.US Department of Veterans Affairs. Health Care Services for Women Veterans Veterans Health Administration (VHA) Handbook 1330.01. 2010Washington, DC: US Department of Veterans Affairs. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Institute of Medicine. Primary Care. 1996Washington, DC: National Academy of Sciences Press. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Institute of Medicine. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. 2001Washington, DC: National Academy of Sciences. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Clancy CM, Massion CT. American women’s health care: a patchwork quilt with gaps. JAMA. 1992;268:1918–1920. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Celik H, Lagro-Janssen TALM, Widdershoven GGAM, et al. Bringing gender sensitivity into healthcare practice: a systematic review. Patient Educ Counseling. 2011;84:143–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gijsbers Van Wijk CMT, Van Vliet KP, Kolk AM. Gender perspectives and quality of care: towards appropriate and adequate health care for women. Soc Sci Med. 1996;43:707–720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Judd F, Armstrong S, Kulkarni J. Gender-sensitive mental health care. Australas Psychiatry. 2009;17:105–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cordasco KM, Zephyrin LC, Kessler CS, et al. An inventory of VHA emergency departments’ resources and processes for caring for women. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28suppl 2S583–S590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jones J, Hunter D. Consensus methods for medical and health services research. BMJ. 1995;311:376–380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Friedman SA, Phibbs CS, Schmitt SK, et al. New women Veterans in the VHA: A longitudinal profile. Womens Health Issues. 2011;21supplS103–S111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yano EM, Haskell S, Hayes P. Delivery of gender-sensitive comprehensive primary care to women veterans: implications for VA Patient Aligned Care Teams. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29suppl 2S703–S707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wright SM, Schaefer J, Reyes-Harvey E, et al. Comparing the Care of Men and Women Veterans in the Department of Veterans Affairs. 2012Washington, DC: Veterans Health Administration. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kimerling R, Street AE, Gima K, et al. Evaluation of universal screening for military-related sexual trauma. Psychiatr Serv. 2008;59:635–640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Katzburg JR, Yano EM, Washington DL, et al. Combining women’s preferences and expert advice to design a tailored smoking cessation program. Subst Use Misuse. 2009;44:2114–2137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bastian LA, Trentalange M, Murphy TE, et al. Association between women Veterans’ experiences with VA outpatient health care and designation as a women’s health provider in primary care clinics. Womens Health Issues. 2014;24:605–612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hamilton AB, Frayne SM, Cordasco KM, et al. Factors related to attrition from VA healthcare use: findings from the National Survey of Women Veterans. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28suppl 2S510–S516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Department of Veterans Affairs. Expanded access to non-VA care through the Veterans Choice Program. Interim final rule. Fed Regist. 2014;79:65571–65587. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bielawski MP, Goldstein KM, Mattocks KM, et al. Improving care for chronic conditions for women veterans: identifying opportunities for comparative effectiveness research. J Comp Eff Res. 2014;3:155–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zephyrin LC, Katon JG, Yano EM. Strategies for transforming reproductive healthcare delivery in an integrated healthcare system: a national model with system-wide implications. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2014;26:503–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Maguen S, Cohen B, Ren L, et al. Gender differences in military sexual trauma and mental health diagnoses among Iraq and Afghanistan veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. Womens Health Issues. 2012;22:e61–e66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vimalananda VG, Miller DR, Palnati M, et al. Gender disparities in lipid-lowering therapy among veterans with diabetes. Womens Health Issues. 2011;21supplS176–S181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Maisel NC, Haskell S, Hayes PM, et al. Readying the workforce: Evaluation of VHA’s comprehensive women’s health primary care provider initiative. Med Care. 2014(In press). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vogt DS, Barry AA, King LA. Toward gender-aware health care: evaluation of an intervention to enhance care for female patients in the VA setting. J Health Psychol. 2008;13:624–638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Whitehead AM, Czarnogorski M, Wright SM, et al. Improving trends in gender disparities in the Department of Veterans Affairs: 2008-2013. Am J Public Health. 2014;104suppl 4S529–S531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Keuken DG, Haafkens JA, Moerman CJ, et al. Attention to sex-related factors in the development of clinical practice guidelines. J Women’s Health. 2007;6:82–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Campbell SM, Hann M, Roland MO, et al. The effect of panel membership and feedback on ratings in a two-round Delphi survey: results of a randomized controlled trial. Med Care. 1999;37:964–968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Isler MR, Corbie-Smith G. Practical steps to community engaged research: from inputs to outcomes. J Law Med Ethics. 2012;40:904–914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.McNeil M, Hayes P. Women’s health care in the VA system: another “patchwork quilt.” Womens Health Issues. 2003;13:47–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]