Abstract

Purpose

Individuals with spina bifida are typically followed closely as outpatients by multidisciplinary teams. However, emergent care of these patients is not well defined. We describe patterns of emergent care in patients with spina bifida and healthy controls.

Materials and Methods

We reviewed Nationwide Emergency Department Sample data from 2006 to 2010. Subjects without spina bifida (controls) were selected from the sample using stratified random sampling and matched to each case by age, gender and treatment year at a 1:4 ratio. Missing emergency department charges were estimated by multiple imputation. Statistical analyses were performed to compare patterns of care among emergency department visits and charges.

Results

A total of 226,709 patients with spina bifida and 888,774 controls were identified. Mean age was 28.2 years, with 34.6% of patients being younger than 21. Patients with spina bifida were more likely than controls to have public insurance (63.7% vs 35.4%, p <0.001) and to be admitted to the hospital from the emergency department (37.0% vs 9.2%, p <0.001). Urinary tract infections were the single most common acute diagnosis in patients with spina bifida seen emergently (OR 8.7, p <0.001), followed by neurological issues (OR 2.0, p <0.001). Urological issues were responsible for 34% of total emergency department charges. Mean charges per encounter were significantly higher in spina bifida cases vs controls ($2,102 vs $1,650, p <0.001), as were overall charges for patients subsequently admitted from emergent care ($36,356 vs $29,498, p <0.001).

Conclusions

Compared to controls, patients with spina bifida presenting emergently are more likely to have urological or neurosurgical problems, to undergo urological or neurosurgical procedures, to be admitted from the emergency department and to incur higher associated charges.

Keywords: case-control studies, emergency treatment, spinal bifida cystica

Spina bifida is a major congenital birth defect in which the neural tube fails to close properly during embryonic development. Although the use of perinatal folic acid supplementation has significantly reduced the birth prevalence of spina bifida, this condition remains the most common permanently disabling birth defect in the United States.1,2 Furthermore, an increasingly large number of children with spina bifida are surviving beyond infancy into childhood and adolescence as a result of modern medical and surgical advances.3

Because SB affects multiple organ systems, a multidisciplinary approach including neurosurgery, urology, orthopedics and developmental pediatrics is often used to manage these cases. However, an aging SB population cannot always be accommodated by traditional pediatric clinics, and coordinating a multidisciplinary transition from pediatric to adult care can be problematic. Adults with SB are reportedly frequent users of acute care hospitals and emergency departments as a major provider of their primary care needs instead of establishing themselves with an adult primary care provider.4,5 As such, a better understanding of patterns of ED care among individuals with SB is crucial to improve the care (and care transitions) of these often complex cases. We describe emergent care patterns and associated medical charges in patients with SB and healthy controls using a large, population based emergency room encounter registry.

Patients and Methods

Data Source

We analyzed Nationwide Emergency Department Sample data from 2006 to 2010. NEDS is an all payer database managed by HCUP and sponsored by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Data in NEDS are from a 20% stratified probability sample of hospital based EDs in the United States based on 5 hospital characteristics, including ownership/profit status, trauma center designation, teaching status, urban/rural location and geographical region. NEDS contains ED visits that do not result in hospitalization and patients who are seen at the ED and subsequently admitted to the same hospital.

NEDS captures patient demographics, clinical features such as acute and chronic diagnostic codes, procedures performed at the ED and subsequent admission, ED disposition and charge data. HCUP has defined post-stratification discharge weights that may be used to estimate nationwide approximations.6

Case and Control Selection

We identified individuals with SB (cases) by ICD-9-CM diagnostic codes 741.X and 756.17 in any diagnosis field. Controls were randomly selected from the overall NEDS cohort using stratified random sampling. Controls were matched to each study subject by age (year), gender and treatment year at a case-to-control ratio of 1:4.

Covariates for Analysis

Analyzed covariates included basic patient demographics, ie median household income quartiles by zip code, insurance payer (public insurance including Medicare and Medicaid, primary and other), Elixhauser cormorbidity index,7 total charges from ED and subsequent admissions, ED disposition (discharged, admitted, transferred, died, other), and hospital characteristics such as hospital teaching status (metropolitan nonteaching, metropolitan teaching, nonmetropolitan) and geographical region (Northeast, South, Midwest, West).

Outcome Selection

We defined ED diagnoses and procedures as primary outcomes. Single and multilevel clinical classifications software was used to define these outcomes, and NEDS chronic disease indication was used to categorize each as acute or chronic. NEDS is structured such that each ED visit/encounter lists the top 15 diagnoses most relevant to that specific visit, ie each diagnosis is simply listed as 1 of 15 diagnoses, and does not necessarily represent a “principal” diagnosis. Acute neurological diagnoses were additionally defined to include neurosurgical device malfunction (ICD-CM-9 diagnosis code 996.2, 996.63 or 996.75) and multilevel CCS diagnosis, “Diseases of the nervous system and sense organs.” We defined ventricular shunt procedures as ventricular shunt placement or revision (ICD-CM-9 procedure code 02.3x or 02.4x).

We also examined total charges per ED visit and total hospital charges from the ED and subsequent admission. These charges were reflective of the facility fees associated with each encounter record.

Statistical Analysis

Bivariate analyses were performed to compare demographics and hospital characteristics of SB cases and controls. We used the Rao-Scott chi-square test, t-test or Wilcoxon rank sum test as appropriate based on data characteristics and distribution. Rates of acute diagnoses and procedures were estimated for cases and controls. All analyses were weighted using HCUP provided estimated weights and estimated covariance matrices to obtain nationwide representation. Generalized estimating equations were used to account for NEDS complex survey design in addition to hospital clustering effects.

Missing charges were treated as missing at random and estimated by multiple imputation methods using other known variables, including patient age, gender, Elixhauser comorbidity index, disposition, insurance, geographical region and injury status. Charges were adjusted to 2010 United States dollars using the Consumer Price Index.8

An alpha of 0.05 and 95% confidence intervals were used as criteria for statistical significance. All analyses were performed using SAS®, version 9.3.

Results

Demographics

A total of 226,709 SB cases and 888,774 control weighted subjects were identified in the 2006 to 2010 NEDS (table 1). Mean patient age was 28.2 years, and 34.6% of patients were younger than 21. Males constituted 43.4% of the overall cohort. Compared to controls, patients with SB were more likely to have public insurance, to be treated at a metropolitan teaching hospital and to be admitted from the ED.

Table 1. Characteristics of patients with SB and controls.

| Cases | Controls | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD age (yrs) | 28.23 ± 0.58 | 28.39 ± 0.13 | Matched |

| No. 18 yrs or younger/total No. (%) | 68,469/226,709 (30) | 263,136/888,774 (30) | — |

| No. gender (%): | Matched | ||

| Male | 98,365 (43) | 386,181 (43) | |

| Female | 128,225 (57) | 502,113 (57) | |

| No. treatment yr (%): | Matched | ||

| 2006 | 38,646 (17) | 150,106 (17) | |

| 2007 | 43,089 (19) | 169,132 (19) | |

| 2008 | 48,387 (21) | 188,975 (21) | |

| 2009 | 47,387 (21) | 188,261 (21) | |

| 2010 | 49,200 (22) | 192,301 (22) | |

| No. insurance (%): | <0.0001 | ||

| Public | 144,414 (64) | 314,778 (35) | |

| Private | 58,567 (26) | 329,570 (37) | |

| Other | 23,292 (10) | 240,160 (27) | |

| No. hospital status (%): | <0.0001 | ||

| Metropolitan nonteaching | 78,055 (34) | 377,838 (43) | |

| Metropolitan teaching | 118,030 (52) | 342,628 (39) | |

| Nonmetropolitan | 30,625 (14) | 168,308 (18) | |

| No. ED event (%): | <0.0001 | ||

| Discharged | 136,781 (60) | 784,639 (88) | |

| Admitted | 83,867 (37) | 81,939 (9) | |

| Transferred | 4,207 (2) | 8,754 (1) | |

| Unknown | 1,624 (1) | 12,807 (1) |

Common ED Diagnoses and Procedures

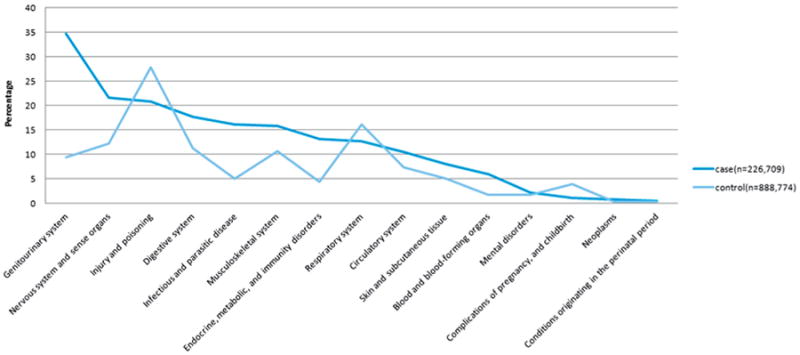

Acute diagnoses in patients with SB were markedly different from controls (see figure). Disorders of the genitourinary system were the most common multilevel CCS category among SB cases, being significantly more likely to occur in SB cases than controls (table 2). By contrast, higher proportions of controls were diagnosed with injury and poisoning, respiratory diseases and pregnancy complications compared to patients with SB (table 3).

Figure.

Multilevel CCS diagnosis in SB cases (dark blue line) and controls (light blue line).

Table 2. Top 10 single level CCS diagnoses in patients with SB.

| Diagnosis | No. Cases (%) | No. Controls (%) | OR (95% CI)* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Urinary tract infection | 60,881 (26.9) | 36,005 (4.1) | 8.7 (8.2–9.2) |

| Fluid + electrolyte disorders | 25,597 (11.3) | 33,459 (3.8) | 3.3 (3.1–3.5) |

| Bacterial infection, unspecified site | 23,523 (10.4) | 8,579 (1.0) | 11.9 (11.0–12.8) |

| Other gastrointestinal disorders | 19,476 (8.6) | 29,302 (3.3) | 2.8 (2.6–2.9) |

| Headache, including migraine | 19,079 (8.4) | 31,273 (3.5) | 2.5 (2.4–2.7) |

| Spondylosis, intervertebral disc disorders, other back problems | 18,980 (8.4) | 44,783 (5.0) | 1.7 (1.6–1.8) |

| Complication of device, implant or graft | 14,994 (6.6) | 2,438 (0.3) | 25.8 (22.9–29.0) |

| Skin + subcutaneous tissue infections | 14,870 (6.6) | 31,436 (3.5) | 1.9 (1.8–2.0) |

| Abdominal pain | 14,218 (6.3) | 65,478 (7.4) | 0.8 (0.8–0.9) |

| Nausea + vomiting | 14,083 (6.2) | 42,102 (4.7) | 1.3 (1.3–1.4) |

p <0.0001.

Table 3. Top 10 single level CCS diagnoses in controls.

| Diagnosis | No. Cases (%) | No. Controls (%) | OR (95% CI)* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Superficial injury, contusion | 8,528 (3.8) | 70,210 (7.9) | 0.5 (0.4–0.5) |

| Abdominal pain | 14,218 (6.3) | 65,478 (7.4) | 0.8 (0.8–0.9) |

| Other upper respiratory infections | 6,017 (2.7) | 62,730 (7.1) | 0.4 (0.3–0.4) |

| Sprains + strains | 8,243 (3.6) | 61,678 (6.9) | 0.5 (0.5–0.6) |

| Spondylosis, intervertebral disc disorders, other back problems | 18,980 (8.4) | 44,783 (5.0) | 1.7 (1.6–1.8) |

| Nausea + vomiting | 14,083 (6.2) | 42,102 (4.7) | 1.3 (1.3–1.4) |

| Other lower respiratory disease | 8,691 (3.8) | 39,716 (4.5) | 0.9 (0.8–0.9) |

| Urinary tract infection | 60,881 (26.9) | 36,005 (4.1) | 8.7 (8.2–9.2) |

| Nonspecific chest pain | 7,710 (3.4) | 35,742 (4.0) | 0.8 (0.8–0.9) |

| Fluid + electrolyte disorders | 25,597 (11.3) | 33,459 (3.8) | 3.3 (3.1–3.5) |

p <0.0001.

The most frequent single level CCS acute diagnoses are outlined in tables 2 and 3. Urinary tract infections comprised the single most common acute diagnosis category in patients with SB seen at the ED, followed by fluid and electrolyte disorders, unspecified site bacterial infection, gastrointestinal disorders and headache.

Device complications were also frequently encountered in SB cases compared to controls. More than half (56%) of device complications in patients with SB occurred in nervous system devices/grafts. By contrast, the most common single level CCS diagnoses in controls were superficial injuries and contusions, abdominal pain, upper respiratory infections, sprains and strains, and back issues including spondylosis and intervertebral disc disorders.

The most common procedures performed in the ED and/or during subsequent admission among SB cases and controls are detailed in supplementary tables 1 and 2 (http://jurology.com/). Of individuals requiring surgical intervention at the ED those with SB were significantly more likely than controls to undergo a urological intervention, typically catheter placement (0.56% of SB cases vs 0.13% of controls, OR 4.4, p <0.001). For individuals subsequently admitted from the ED ventricular shunt procedures were the most commonly performed inpatient procedures in patients with SB (6.4% vs 0.1% in controls, OR 53.5, p <0.001). Individuals with SB also underwent more inpatient procedures than controls, including respiratory intubation and mechanical ventilation (OR 1.5, p <0.001), wound debridement (OR 3.5, p <0.001), hemodialysis (OR 1.3, p <0.001), enteral/parenteral nutrition (OR 2.0, p <0.001), other skin and breast therapeutic procedures (OR 2.4, p <0.001), and other gastroenterology therapeutic procedures (OR 3.3, p <0.001).

ED Charges

Total ED charges are listed in supplementary table 3 (http://jurology.com/). The weighted gross ED charge for patients with SB was estimated at $476 million from 2006 to 2010. Mean ED charge per encounter was significantly higher for patients with SB than controls ($2,102 vs $1,650, p <0.001), as were overall charges for individuals who were subsequently admitted ($36,356 vs $29,498, p <0.001). Urological issues accounted for 34% of total ED charges.

Discussion

Spina bifida is the most common permanently disabling birth defect in the United States, with an incidence of approximately 1 per 1,000 births.9,10 With advances in medical and surgical management an increasing proportion of children with SB are surviving to adulthood.3,11–13 As such, patients with SB collectively require increasing health care expenditures to maintain their health.14–16 Due partly to poor care transition from pediatric to adult providers, an increasingly large proportion of patients with SB reportedly seek medical attention at the ED instead of from primary care providers.5,17

We evaluated patterns of ED care in patients with SB by analyzing a large, nationally representative database. Interestingly we found that genitourinary issues were the most frequently diagnosed problem in patients with SB at the ED. This finding remained consistent throughout the study period. Given that the majority of SB cases involve neurogenic bladder dysfunction, bladder management has a critical role in the long-term health and well-being of these individuals. Complications of SB related neurogenic bladder include urinary incontinence, UTI and renal failure.18 These complications can cause significant disability, diminish quality of life, and add to the significant health related burdens of patients with SB and their caregivers.

Furthermore, UTI was the most frequent ED visit diagnosis among patients with SB. As outlined in tables 2 and 3, UTIs appeared to occur significantly more frequently among patients with SB than controls. Caterino et al similarly reported UTI as the most common ED diagnosis in a single institution ED visit series.17 Such a high UTI rate in patients with SB raises the concern of improper ambulatory care, since UTI is considered a potentially preventable condition in the outpatient setting.16,19 A more comprehensive program to prevent UTI in high risk SB cases may be beneficial in SB management. Furthermore, UTI in patients with SB may be hard to capture due to the high variability of UTI diagnostic and treatment criteria, as recently demonstrated by our group.18 In that study the rather high UTI diagnosis rate at EDs we observed could potentially underestimate an even larger SB population with UTI issues. Conversely this finding could also represent a high rate of asymptomatic bacteriuria being incorrectly interpreted as UTI.

Neurological complications including headache, epilepsy, convulsions and ventricular shunt malfunctions are the other major categories among patients with SB presenting to the ED in our study. In fact, ventricular shunt related surgery was the most commonly performed procedure during post-ED admission. A significant number of patients with SB underwent ventricular shunt surgery due to SB associated hydrocephalus. Unfortunately ventricular shunts in patients with SB are frequently associated with relatively high malfunction and revision rates.19–22 Since shunt malfunction is associated with high morbidity and mortality, clinical providers must remain vigilant and have a low threshold for suspecting shunt malfunction in patients with SB.

Care for children with SB is expensive. Cassell et al observed that the mean expenditure during the first year of life in an infant with SB was nearly tenfold greater than that of a child free of birth defects.23 Yi et al observed that lifetime direct medical costs for patients with SB are more than $50,000 yearly per person, with the majority of expenditures covering inpatient care, treatment at initial diagnosis and comorbid conditions in adulthood.24 We found that patients with SB were significantly more likely to incur higher ED charges and subsequent inpatient charges than controls. This finding is also corroborated by other studies showing considerably higher medical costs in patients with vs without SB.4,24–26 Further studies investigating ways to decrease costs potentially through reducing preventable conditions such as UTI, and to provide better quality of care for patients with SB, especially in transition between adolescence and adulthood, are warranted.

Our study findings must be interpreted in the context of its limitations. NEDS represents a 20% stratified sample of United States hospital based ED encounters. As such, our reported results may not be generalizable to encounters not in the sample pool. However, NEDS provides meticulous tracking of discharge and hospital weights to minimize the risk of sampling bias. We are reassured by the fact that the age distribution in our data set is similar to United States Census Bureau figures and other large cohorts of patients with SB.27

Additionally NEDS is a large retrospective administrative database that may be affected by coding bias. Our analysis relies on the accuracy of the diagnostic and procedure codes included in NEDS. While the accuracy level of NEDS is high for an administrative database, it is possible that at least some portion of our cohort may be incorrectly coded. However, as noted previously, the NEDS database is rigorously monitored and audited for coding accuracy, and, therefore, represents a reasonably reliable panorama of the characteristics of its cohort.

Because NEDS represents encounter based rather than patient based data, it is impossible to track a given patient through time. We were unable to assess longer term outcomes beyond each encounter and whether patients may be accounted for multiple times. The retrospective nature of NEDS also limits the available data, and NEDS has some missing data. As an example, roughly 20% of total ED charges data were missing in NEDS. However, we adjusted our estimates using multiple imputation methods to decrease the chances of error and systematic bias.

Conclusions

Patients with spina bifida presenting to the emergency department are more likely than controls to have urological or neurosurgical problems, to be admitted from the ED and to undergo neurosurgical procedures, especially ventricular shunt related surgery. Individuals with SB also incur higher charges at the ED and during subsequent inpatient admission compared to controls.

Supplementary Material

Abbreviations and Acronyms

- CCS

clinical classifications software

- ED

emergency department

- HCUP

Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project

- NEDS

Nationwide Emergency Department Sample

- SB

spina bifida

- UTI

urinary tract infection

References

- 1.Honein MA, Paulozzi LJ, Mathews TJ, et al. Impact of folic acid fortification of the US food supply on the occurrence of neural tube defects. JAMA. 2001;285:2981. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.23.2981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mathews TJ, Honein MA, Erickson JD. Spina bifida and anencephaly prevalence–United States, 1991-2001. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2002;51:9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davis BE, Daley CM, Shurtleff DB, et al. Long-term survival of individuals with myelomeningocele. Pediatr Neurosurg. 2005;41:186. doi: 10.1159/000086559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Young NL, Steele C, Fehlings D, et al. Use of health care among adults with chronic and complex physical disabilities of childhood. Disabil Rehabil. 2005;27:1455. doi: 10.1080/00222930500218946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McDonnell GV, McCann JP. Why do adults with spina bifida and hydrocephalus die? A clinic-based study. Eur J Pediatr Surg, suppl. 2000;10:31. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1072411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) NEDS Overview. Rockville, Maryland: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2014. [Accessed June 22, 2014]. Available at, http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/nedsoverview.jsp. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, et al. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care. 1998;36:8. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199801000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.United States Department of Labor. [Accessed June 22, 2014];Bureau of Labor Statistics: Consumer Price Index. Available at http://www.bls.gov/cpi/

- 9.Lloyd JC, Wiener JS, Gargollo PC, et al. Contemporary epidemiological trends in complex congenital genitourinary anomalies. J Urol, suppl. 2013;190:1590. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2013.04.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stein SC, Feldman JG, Friedlander M, et al. Is myelomeningocele a disappearing disease? Pediatrics. 1982;69:511. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bowman RM, McLone DG, Grant JA, et al. Spina bifida outcome: a 25-year prospective. Pediatr Neurosurg. 2001;34:114. doi: 10.1159/000056005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Steinbok P, Irvine B, Cochrane DD, et al. Long-term outcome and complications of children born with meningomyelocele. Childs Nerv Syst. 1992;8:92. doi: 10.1007/BF00298448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McLaughlin JF, Shurtleff DB, Lamers JY, et al. Influence of prognosis on decisions regarding the care of newborns with myelodysplasia. N Engl J Med. 1985;312:1589. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198506203122501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McDonnell GV, McCann JP. Issues of medical management in adults with spina bifida. Childs Nerv Syst. 2000;16:222. doi: 10.1007/s003810050502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barf HA, Post MW, Verhoef M, et al. Life satisfaction of young adults with spina bifida. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2007;49:458. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2007.00458.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kinsman SL, Doehring MC. The cost of preventable conditions in adults with spina bifida. Eur J Pediatr Surg, suppl. 1996;6:17. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1071031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Caterino JM, Scheatzle MD, D'Antonio JA. Descriptive analysis of 258 emergency department visits by spina bifida patients. J Emerg Med. 2006;31:17. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2005.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Madden-Fuentes RJ, McNamara ER, Lloyd JC, et al. Variation in definitions of urinary tract infections in spina bifida patients: a systematic review. Pediatrics. 2013;132:132. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-0557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dicianno BE, Wilson R. Hospitalizations of adults with spina bifida and congenital spinal cord anomalies. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2010;91:529. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2009.11.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Swank M, Dias L. Myelomeningocele: a review of the orthopaedic aspects of 206 patients treated from birth with no selection criteria. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1992;34:1047. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.1992.tb11416.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tomlinson P, Sugarman ID. Complications with shunts in adults with spina bifida. BMJ. 1995;311:286. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.7000.286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hunt GM, Oakeshott P. Episodes of symptomatic shunt insufficiency related to outcome at the mean age of 30: a community-based study. Eur J Pediatr Surg, suppl. 2001;11:S33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cassell CH, Grosse SD, Thorpe PG, et al. Health care expenditures among children with and those without spina bifida enrolled in Medicaid in North Carolina. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2011;91:1019. doi: 10.1002/bdra.22864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yi Y, Lindemann M, Colligs A, et al. Economic burden of neural tube defects and impact of prevention with folic acid: a literature review. Eur J Pediatr. 2011;170:1391. doi: 10.1007/s00431-011-1492-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ireys HT, Anderson GF, Shaffer TJ, et al. Expenditures for care of children with chronic illnesses enrolled in the Washington State Medicaid program fiscal year 1993. Pediatrics. 1997;100:197. doi: 10.1542/peds.100.2.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ouyang L, Grosse SD, Armour BS, et al. Health care expenditures of children and adults with spina bifida in a privately insured U.S. population. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2007;79:552. doi: 10.1002/bdra.20360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tennant PW, Pearce MS, Bythell M, et al. 20-Year survival of children born with congenital anomalies: a population-based study. Lancet. 2010;375:649. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61922-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.