Malaria is a mosquito-borne infection caused by parasites of the genus Plasmodium and may present as a spectrum of diseases ranging from asymptomatic infection to death. The estimated 660 000 fatal cases annually are almost all caused by Plasmodium falciparum, due to the ability of this species to cause high parasitaemia and sequestration of the infected erythrocytes in the microvasculature of vital organs.

P. falciparum is also the cause of the vast majority of cases of renal failure in malaria. The incidence of acute kidney injury (AKI) in P. falciparum is ∼1–5% in natives of endemic areas who have some degree of immunity, but is much higher in non-immune subjects, with reported incidences of up to 30% [1]. When AKI occurs, mortality is high and ranges from 15 to 45%. The World Health Organization therefore classifies malaria infection with AKI as severe malaria. We describe a patient with severe P. falciparum infection and AKI, in which renal biopsy revealed an unexpected cause.

Case report

A 62-year-old woman of African descent with a history of hypertension and type 2 diabetes mellitus presented with high fever and malaise for 4 days. One week earlier she had returned from a holiday in Ghana, where she had not used malaria prophylaxis. She was diagnosed with a P. falciparum infection. Parasitaemia was 15.6% and she had AKI (RIFLE Stage F). She was classified as having severe malaria.

She was admitted to the intensive care unit for treatment with exchange transfusions and intravenous artesunate. Treatment was continued with oral atovaquone/proguanil. Despite rehydration and rapid parasite clearance, her serum creatinine increased and she remained anuric. Two days after admission, renal replacement therapy was initiated.

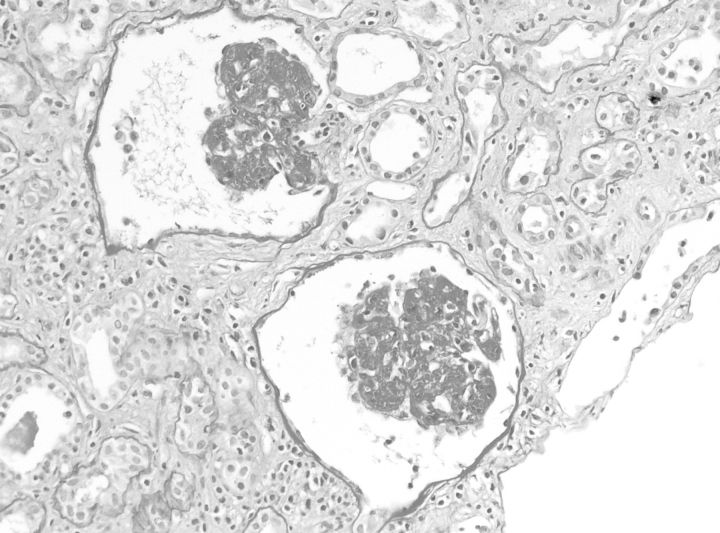

After 6 weeks, diuresis gradually increased to 2000 mL/ day. However, creatinine clearance remained 8 mL/min and she was found to have nephrotic-range proteinuria (20 g/day). A renal biopsy was performed. As expected, light microscopic evaluation showed marked acute tubular necrosis (ATN). In addition, glomerular abnormalities consistent with collapsing focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (cFSGS) were discerned (Figure 1). On immunofluorescence, complement factor C3 deposits were seen. Staining on IgG, IgA, C1q and kappa and lambda light chains was negative and the IgM pattern was similar to that of C3, although with less intensity. Electron microscopy confirmed the presence of cFSCS and was not compatible with membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis. Known causes of cFSGS like human immunodeficiency virus, parvovirus B19, cytomegalovirus, Campylobacter jejuni and tuberculosis were ruled out. She was not started on immunosuppressive therapy because the response in cFSGS is decidedly poor and because her clinical condition did not allow it. Sixteen months after her initial presentation, she still required renal replacement therapy and her residual renal function has steadily declined.

Fig. 1.

cFSGS: two glomeruli with diffuse and global collapse (Periodic acid-Schiff stain). Available as colour image as an online supplementary file.

Discussion

We described a patient with no history of renal disease, who developed AKI during a severe P. falciparum infection. Recovery of diuresis after her AKI revealed nephrotic syndrome due to cFSGS.

Both Plasmodium malariae and P. falciparum infection are well-known causes of malarial renal disease. However, the responsible pathophysiological mechanisms are different. Plasmodium malariae associated nephropathy typically presents as a nephrotic syndrome several weeks after infection and usually progresses gradually despite parasite eradication [2]. Histopathological investigation typically shows mesangioproliferative glomerulonephritis with immune complex deposits containing IgG, C3 and malarial antigens [1, 2].

P. falciparum associated nephropathy usually presents as oliguric or anuric AKI. The exact pathogenesis is not fully understood. As cytoadherance and sequestration of infected erythrocytes in the microvasculature of vital organs is the hallmark of severe falciparum infection, mechanical obstruction of the renal microcirculation by these erythrocytes has been suspected as an important mechanism. In a post-mortem study of renal tissue of patients who died of severe P. falciparum malaria, it was found that there was a correlation between the degree of renal parasite sequestration and renal failure. However, as the degree of sequestration in renal capillaries was found to be mild, this does not seem to be the sole cause of renal failure. Other mechanisms involved, include numerous humoral mediators that are abundantly present during severe malaria [1–4]. On histopathological examination the predominant finding is ATN, but it is frequently accompanied by interstitial inflammation. Glomerular lesions have also been described in falciparum infection, and are characterized by mesangial proliferation with granular deposits of IgM and C3. Parasitized erythrocytes can sometimes be found in the glomerular capillaries mild proteinuria has been described in 20–50% of cases, but nephrotic syndrome has rarely been reported [4].

Known causes of collapsing FSGS were excluded in our patient. She did not receive any medication known to cause nephrotic syndrome. Our patient was diabetic, but her renal function was completely normal 1 year prior to presentation and nephrotic-range proteinuria in diabetes mellitus is not caused by cFSGS. We therefore concluded that cFSGS was caused by her malaria infection.

The pathogenesis of cFSGS has not been fully clarified. It was associated with a broad range of etiologic factors, and a role of immune activation has been hypothesized. Genetic factors also seem to be involved, as the prevalence of cFSGS is higher in patients of African ethnicity. cFSGS is a highly unusual finding in malaria-associated renal failure. One report was found, describing a patient with a P. falciparum infection complicated by haemophagocytic syndrome. In this case however, the FSGS was thought to be caused by the haemophagocytic syndrome rather than malaria [5].

The pathogenesis of the cFSGS in our patient remains elusive, but one could speculate that an immune activation triggered by the P. falciparum infection combined with a genetic susceptibility was involved.

Conclusion

Although P. falciparum infection usually causes ATN; in our patient renal biopsy revealed, apart from tubular damage, cFSGS. This is a highly uncommon finding in malarial renal failure.

Conflict of interest statement

The case presented in this paper has not been published previously in whole or part. The authors state that they have no competing interests to declare.

References

- 1.Barsoum RS. Malarial acute renal failure. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2000;11:2147–2154. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V11112147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Das BS. Renal failure in malaria. J Vector Borne Dis. 2008;45:83–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nguansangiam S, Day NPJ, Hien TT, et al. A quantitative ultrastructural study of renal pathology in fatal plasmodium falciparum malaria. Trop Med Int Health. 2007;12:1037–1050. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2007.01881.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barsoum RS. Malarial nephropathies. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1998;13:1588–1597. doi: 10.1093/ndt/13.6.1588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Niang A, Niang SE, Kael HF, et al. Collapsing glomerulopathy and haemophagocytic syndrome related to malaria: a case report. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2008;23:3359–3361. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfn427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]