Abstract

Controversy in management of athletes exists after anterior cruciate ligament injury and reconstruction. Consensus criteria for evaluating successful outcomes following ACL injury include no re-injury or recurrent giving way, no joint effusion, quadriceps strength symmetry, restored activity level and function, and returning to pre-injury sports. Using these criterions, we will review the success rates of current management strategies after ACL injury and provide recommendations for the counseling of athletes after ACL injury.

Keywords: Anterior Cruciate Ligament, Knee, ACLR, ACL, Physical Therapy, Athletes, Sports Physical Therapy

Introduction

More than 250,000 anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injuries occur yearly in the United States1, with 125,000–175,000 undergoing ACL reconstruction (ACLR)2,3. While standard of practice in the United States is early reconstruction for active individuals with the promise of returning to pre-activity injury levels4,5, evidence suggests athletes are counseled that reconstruction is not required to return to high level activity after a program of intensive neuromuscular training6. Others advocate counseling for a delayed reconstruction approach7, however no differences in outcomes exist between delayed and early ACL reconstruction6. Furthermore, athletes in the United States are commonly counseled to undergo early ACLR5 with the promise of restoring static joint stability, minimizing further damage to the mensicii and articular cartilage8,4, and preserving knee joint health5, however, not all athletes are able to return to sport or exhibit normal knee function following reconstruction9. Several factors, such as impaired functional performance, knee instability and pain, reduced range of motion, quadriceps strength deficits, neuromuscular dysfunction, and biomechanical maladaptations, may account for highly variable degree of success.

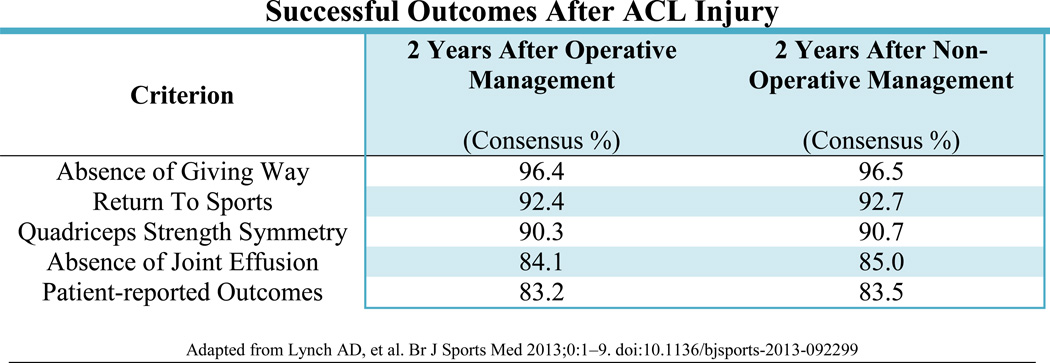

In order to identify the minimum set of outcomes that identify success after ACL injury or ACLR, Lynch et al established consensus criteria from 1779 sports medicine professionals concerning successful outcomes after ACL injury and reconstruction10. The consensus of successful outcomes were identified as no re-injury or recurrent giving way, no joint effusion, quadriceps strength symmetry, restored activity level and function, and returning to pre-injury sports10 Figure 1. Using these criterions we will review the success rates of current management after ACL injury and provide recommendations for the counseling of athletes after ACL injury.

Figure 1.

Consensus criteria on successful outcomes after anterior cruciate ligament injury and reconstruction from 1779 sports medicine professionals.

Impairment Resolution

Following ACL injury or reconstruction, athletes undergo an extensive period of vigorous rehabilitation targeting functional impairments. These targeted rehabilitation protocols strive for full symmetrical range of motion, adequate quadriceps strength, walking and running without frank aberrant movement, and a quiet knee: little to no joint effusion or pain10. Despite targeted post-operative rehabilitation, athletes commonly experience quadriceps strength deficits11,12,13, lower self-reported knee function14, and movement asymmetry15,16 up to two years after reconstruction. The importance of quadriceps strength as a dynamic knee stabilizer has been established, as deficits have been linked to lower functional outcomes12,17. In a systematic review of quadriceps strength after ACLR, quadriceps strength deficits can exceed 20% 6 months after reconstruction, with deficits having the potential to persist for 2 years after reconstruction13. Otzel et al reported a 6–9% quadriceps deficit 3 years after reconstruction, concluding that long-term deficits after surgery were the results of lower neural drive as quadriceps atrophy measured by thigh circumference was not significantly different between limbs18. Grindem et al reported at two-year follow up 23% of non-operatively managed athletes had greater than 10% strength deficits compared to 1/3 of athletes who underwent reconstruction.19 Another study comparing operatively and non-operatively managed patients 2–5 years after ACL injury found no differences in quadriceps strength between groups concluding reconstructive surgery is not a prerequisite for restoring muscle function20. Regardless of operative or non-operative management, quadriceps strength deficits are ubiquitous after ACL injury, and can persist for the long term. The current evidence does not support ACLR as a means of improved quadriceps strength outcomes over non-operative management after ACL injury.

Outcomes

Individuals do not respond uniformly to an acute ACL injury and outcomes can vary. Most individuals decrease their activity level after ACL injury21,20,22–25. While a large majority of individuals rate their knee function below normal ranges after an ACL injury, which is a common finding early after an injury26–30, some individuals exhibit higher perceived knee function than others early after ACL injury28–30. This highlights the variability in outcomes seen after ACL injury.

Knee outcome scores are lowest early after surgery and improve up to 6 years post surgery29,31,32. Using the Cincinnati Knee Rating System, scores improved from 60.5/100 at 12 weeks post reconstruction to 85.9/100 at 1 year follow-up32. By six months after surgery almost half of individuals score greater than 90% on the Knee Outcomes Survey- Activities of Daily Living Scale (KOS-ADLS) and Global Rating Scale of Perceived Function (GRS) and 78% have achieved these scores by 12 months14. Using the GRS, scores improved from 63.1/100 taken at week 12 to 83.3/100 at week 5232. Moksness and Risberg reported similar post-surgical GRS results of 86.0/100 at 1 year follow-up29. Poor self-report on outcome measures after ACLR are associated with chondral injury, previous surgery, return to sport, and poor radiological grade in ipsilateral medial compartment33. ACLR revision and extension deficits at 3 months are also predictors of poor long term outcomes34,35

Patient reported outcomes from multiple large surgical registries are available concerning patients after ACLR. A study from the MOON consortium of 446 patients reported International Knee Documentation Committee Subjective Knee Form 2000 (IKDC) for patients 2 and 6 years after reconstruction36. The median IKDC score was 45 at baseline, rose to 75 at 2 year follow up, and reached 77 at 6 years after reconstruction36. Grindem et al compared IKDC scores between athletes managed non-operatively or with reconstruction at baseline and 2 years19. The non-operative group improved from a score of 73 at baseline to 89 2 years after injury19. The reconstructed group improved from 69 at baseline to 89 2 years after surgery19. There were no significant differences between groups at baseline or at 2 year follow-up19. Using the Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS), Frobell et al compared patient reported outcomes at 5 years after ACL injury and found no significant differences in change score from baseline to 5 years in those managed with early reconstruction versus those managed non-operatively or with delayed reconstruction37. Outcomes after ACL injury, whether managed non-operatively or with ACLR, have similar patient reported outcomes scores at up to 5 years after injury.

Long-Term Joint Health

Preventing further intra-articular injury and preserving joint surfaces for long-term knee health is a purposed reason to surgically stabilize an unstable knee5. Patients who had increased knee laxity after an ACL injury are more likely to have late meniscal surgery33 and time from ACL injury is associated with the number of chondral injuries and severity of chondral lesions38. Injury to menisci or articular cartilage places the knee at increased risk for the development of osteoarthritis39. Barenius et al found a 3 fold increase in knee osteoarthritis prevalence in surgically reconstructed knees 14 years after surgery39. They concluded that while ACLR did not prevent secondary osteoarthritis, initial meniscal resection was a risk factor for osteoarthritis with no differences in osteoarthritis prevalence seen between graft types39. A recent systematic review compared operatively and non-operatively treated patients at a mean of 14 years after ACL injury40 and found no significant differences between groups in radiographic osteoarthritis40. The operative group had less subsequent surgery and meniscal tears, as well as increased Tegner change scores however there were no differences in Lysholm or IKDC scores between groups40. The current evidence does not support the use of ACLR to reduce secondary knee osteoarthritis after ACL injury.

Return to Pre-Injury Sports

Returning to sports is often cited as the goals of athletes and health care professionals after ACL injury or ACLR. When asked, 90% of NFL head team physicians believed that 90–100% of NFL players returned to play after ACLR41. Shah et al found that regardless of position 63% of NFL athletes seen at their facility returned to play42. A recent systematic review reported 81% of athletes return to any sports at all, but only 65% return to their pre-injury level and an even smaller percentage, 55%, return to competitive sports43 Figure 2. This review found that younger athletes, men, and elite athletes were more likely to return to sports43. Similar reports within this range are common when examining amateur athletes by sport. McCullough et al. report that 63% of high school and 69% of college football players return to sport44. Shelbourne found that 97% of high school basketball players return to play, 93% of high school women and 80% of high school male soccer players returned45. Brophy et al. found a slightly different trend in soccer players; 72% returned to play, where 61% returned to the same level of competition but when broken down by sex more men (75%) returned than women (67%)46. These studies highlight the fact that while there may be a link between sport and return to sport, due to a lack of high quality research, current literature was unable to come to any conclusion47.

Figure 2.

Meta-analysis pooled return to sport rates43

Reported return to sport rates after ACLR from Arden et al 2014 systematic review and meta-analysis

Reduced return to sport rates can be attributed to many factors, including age, sex, pre-injury activity level, fear and psychological readiness. Age and sex are two variables which have been identified in multiple studies43,46, with men and younger athletes being more likely to return to sport. Age, may be a proxy measure for changing priorities (i.e. family), commitments (i.e. employment), and/or opportunities to play at the same level (i.e. no longer have the competitive structure of high school, college, or club sports)43. Further, it has been hypothesized that “For those athletes whose life and social networks are inherently structure around participating in sport, a stronger sense of athletic identity may be a positive motivator for return to sport”43. While this hypothesis remains to be tested, this could explain the higher rates of return to sport in younger and elite/professional level athletes. Dunn et al found that higher level of activity at prior to injury and a lower BMI were predictive of higher activity levels at two years following ACLR48. Ardern et al found that elite athletes were more likely to return to sport that lower level athletes43. Professional and elite level athletes may have access to more resources, particularly related to rehabilitation services, but motivation to return to that high level of play and athletic identity may also drive such return to sport43. Interestingly, Shah et al. found that in NFL players return to play was predicted by draft round. Athletes drafted in the first four rounds of the NFL draft were 12.2 times more likely to return to sport than those athletes drafted later or as free agents42. This could represent the perceived talent of the player as well as the investment of the organization in that player42.

Despite common misconceptions, non-operatively managed athletes can return to sport without the need for reconstruction26. Fitzgerald et al reported a decision making scheme for returning ACL deficient athletes to sport in the near-term, without furthering of meniscal or articular cartilage injury26. There is a paucity, however, of long-term evidence on non-operatively managed athletes returning to high level sports. Grindem et al compared return to sport in operatively and non-operatively managed athletes after ACL injury. They found no significant differences between groups in level I sports participation, and higher level II sports participation in the non-operative group in the first year after injury19. This is the only study to our knowledge comparing return to sport rates in the longer term. Further research is needed on long-term non-operatively managed athletes after ACL injury.

Re-Injury

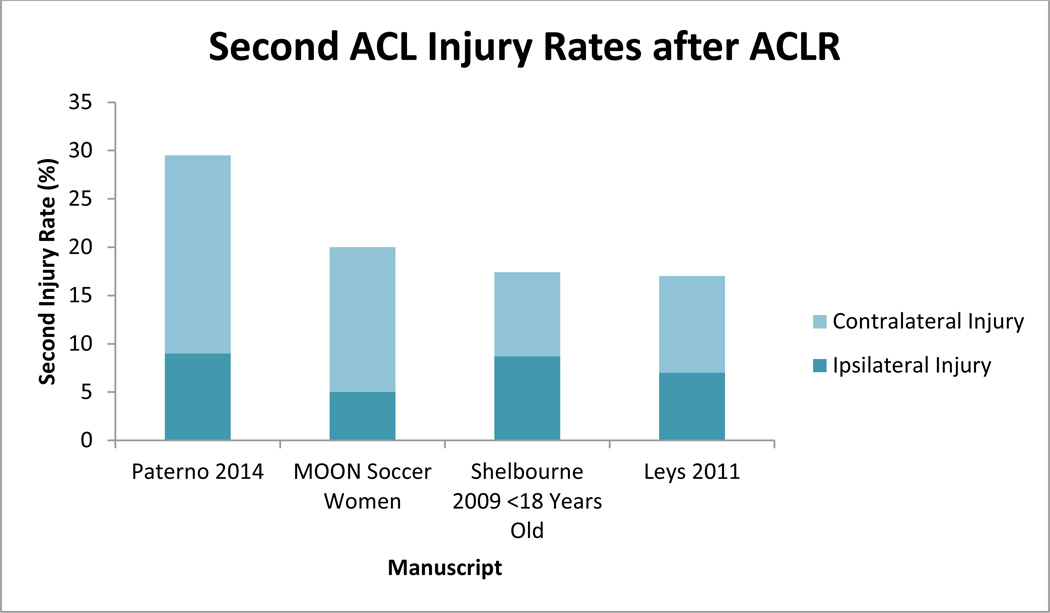

Second injury, whether it is an insult to the ipsilateral graft or the contralateral ACL, is a growing problem after ACLR as rates appear to be higher than once thought. Risk factors for second injury include younger athletes49 who return to high level sporting activities early50,51, with women having a higher risk of contralateral injury52,53, and men having a higher risk of ipsilateral injury54,55. While second injury rates in the general population 5 years after reconstruction are reported to be 6%56, rates in young athletes are considerably higher.51 Paterno et al followed 78 athletes after ACLR and 47 controls over a 24 month period. They found an overall second injury rate of 29.5% which was an incidence rate nearly 4 times that of the controls (8%)51. Over 50% of these injuries occurred within the first 72 athletic exposures, while in the control group only 25% were injured within the same time frame51. The MOON cohort reported a 20% second injury rate in women and a 5.5% rate in men of 100 soccer players returning to sport after ACLR46. Shelbourne et al55 and Leys et al57 both reported 17% second injury rates in younger athletes. Besides missing more athletic time, increasing healthcare costs, and increased psychological distress, re-injury and subsequent revision surgery has significantly worse outcomes compared to those after initial reconstruction34. FIGURE 3

Figure 3.

Discussion

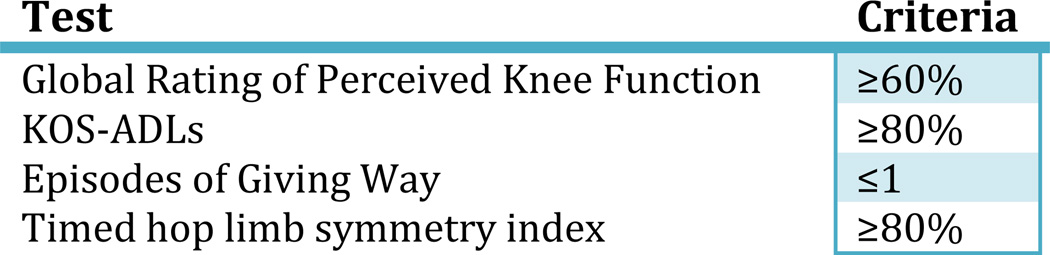

ACLR continues to be the gold standard treatment of ACL injuries in the young athletic population. A survey of American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons reported 98% of surgeons would recommend surgery if a patient wishes to return to sport, with 79% believing ACL deficient patients are unable to return to all recreational sporting activities without reconstruction5. Revisiting the successful outcomes criterion after ACL injury, a successful outcome is considered no re-injury or recurrent giving way, no joint effusion, quadriceps strength symmetry, restored activity level and function, and returning to pre-injury sports10. After reviewing the current literature looking at these criterions, counseling athletes to undergo early reconstruction after ACL injury may not be in the athlete’s best interests. Undergoing reconstruction does not guarantee athletes return to their pre-injury sport, and return to the pre-injury competitive level of sport is unlikely. The risk of a second injury is high in young athletes returning to sport, especially in the near-term. Risk of secondary injury increases for the contralateral limb in females, or the ipsilateral limb in males. The risk for developing osteoarthritis is high in the long-term regardless of surgical intervention, and even higher if a revision procedure is required58. A Cochrane Review found that there was insufficient evidence to recommend ACLR compared to nonoperative treatment, and recent randomized control trials have found no difference between those who had ACLR and those treated nonoperatively with regards to knee function, health status, and return to pre-injury activity level/sport after two and five years in young, active individuals19,37,59. With no differences in outcomes between early reconstruction, delayed reconstruction, and no surgery at all, counseling should start by considering non-operative management. Eitzen et al60 found a 5 week progressive exercise program after ACL injury led to significantly improved knee function before deciding to undergo reconstruction or remain non-operatively managed Figure 4. The authors reported good compliance with few adverse events during training. Non-operative management is a viable evidence based option after ACL injury, allowing some athletes to return to sport despite being ACL deficient, with equivalent functional outcomes to those after ACLR. Given there is no evidence in outcomes to undergo early ACLR, non-operative management should be a first line of treatment choice in athletes after ACL injury. Figure 5

Figure 4.

Perturbation Training

Unilateral rollerboard portion of perturbation training. The athlete attempts to maintain balance in slight knee flexion while the therapist performs manual perturbations. Progression includes adding sport specific tasks while maintaining balance.

Figure 5.

Decision-making scheme for ACL deficient athletes26

Global Rating of Perceived Knee Function (GRS) is a scale from 0 to 100 asking the athlete to rate their current knee function with 100 being back to all pre-injury activity and function. Knee Outcome Survey Activities of Daily Living Questionnaire (KOS-ADLs) is a patient reported outcome measure evaluating knee function within daily activity. Episodes of giving way are true moments of instability in which a shifting occurs in the tibio-femoral joint resulting in an increase in knee pain and joint effusion. The timed hop is one component of hop testing in which the athlete unilaterally hops down a 6 meter line as fast as possible. Symmetry index is calculated by dividing the uninvolved limb time by the involved limb time and multiplying by 100.

Key Points.

Undergoing ACL reconstruction does not guarantee athletes will return to their pre-injury sport, and return to the pre-injury competitive level of sport is unlikely.

The risk of a second ACL injury is high in young athletes returning to sport, especially in the near-term.

The risk for developing osteoarthritis after ACL injury is high in the long-term regardless of surgical intervention, and even higher if a revision procedure is required.

Despite common misconceptions, non-operatively managed athletes can return to sport without the need for reconstruction

Without differences in outcomes between early reconstruction, delayed reconstruction, and nonoperative management, counseling should start by considering non-operative management.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures: None

References

- 1.Griffin LY, Albohm MJ, Arendt Ea, et al. Understanding and preventing noncontact anterior cruciate ligament injuries: a review of the Hunt Valley II meeting, January 2005. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34(9):1512–1532. doi: 10.1177/0363546506286866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hughes G, Watkins J. A risk-factor model for anterior cruciate ligament injury. Sports Med. 2006;36(5):411–428. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200636050-00004. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16646629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim S, Bosque J, Meehan JP, Jamali A, Marder R. Increase in outpatient knee arthroscopy in the United States: a comparison of National Surveys of Ambulatory Surgery, and 1996 and 2006. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93(11):994–1000. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.I.01618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Myklebust G, Bahr R. Return to play guidelines after anterior cruciate ligament surgery. Br J Sports Med. 2005;39(3):127–131. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2004.010900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marx RG, Jones EC, Angel M, Wickiewicz TL, Warren RF. Beliefs and attitudes of members of the American Academy of orthopaedic surgeons regarding the treatment of anterior cruciate ligament injury. Arthrosc J Arthrosc Relat Surg. 2003;19(7):762–770. doi: 10.1016/s0749-8063(03)00398-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smith TO, Davies L, Hing CB. Early versus delayed surgery for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2010;18(3):304–311. doi: 10.1007/s00167-009-0965-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shelbourne_1995_ Timing of Surgery in Acute ACL Tears on the Return of Quadriceps Muscle Strength After Reconstruction Using an Autogenous Patellar Tendon Graft.pdf.

- 8.Andernord D, Karlsson J, Musahl V, Bhandari M, Fu FH, Samuelsson K. Timing of surgery of the anterior cruciate ligament. Arthroscopy. 2013;29(11):1863–1871. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2013.07.270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gobbi A, Francisco R. Factors affecting return to sports after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with patellar tendon and hamstring graft: a prospective clinical investigation. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2006;14(10):1021–1028. doi: 10.1007/s00167-006-0050-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lynch AD, Logerstedt DS, Grindem H, et al. Consensus criteria for defining “successful outcome” after ACL injury and reconstruction: a Delaware-Oslo ACL cohort investigation. Br J Sports Med. 2013:1–9. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2013-092299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Jong SN, van Caspel DR, van Haeff MJ, Saris DBF. Functional assessment and muscle strength before and after reconstruction of chronic anterior cruciate ligament lesions. Arthroscopy. 2007;23(1):21–28. 28.e1–28.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2006.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eitzen I, Holm I, Risberg Ma. Preoperative quadriceps strength is a significant predictor of knee function two years after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Br J Sports Med. 2009;43(5):371–376. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2008.057059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Palmieri-Smith RM, Thomas AC, Wojtys EM. Maximizing quadriceps strength after ACL reconstruction. Clin Sports Med. 2008;27(3):405–424. vii–ix. doi: 10.1016/j.csm.2008.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Logerstedt D, Lynch A, Axe MJ, Snyder-Mackler L. Symmetry restoration and functional recovery before and after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2013;21(4):859–868. doi: 10.1007/s00167-012-1929-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Paterno MV, Ford KR, Myer GD, Heyl R, Hewett TE. Limb asymmetries in landing and jumping 2 years following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Clin J Sport Med. 2007;17(4):258–262. doi: 10.1097/JSM.0b013e31804c77ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roewer BD, Di Stasi SL, Snyder-Mackler L. Quadriceps strength and weight acceptance strategies continue to improve two years after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. J Biomech. 2011;44(10):1948–1953. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2011.04.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Logerstedt D, Lynch A, Axe MJ, Snyder-Mackler L. Pre-operative quadriceps strength predicts IKDC2000 scores 6 months after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Knee. 2013;20(3):208–212. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2012.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Otzel DM, Chow JW, Tillman MD. Long-term deficits in quadriceps strength and activation following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Phys Ther Sport. 2014:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ptsp.2014.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grindem H, Eitzen I, Engebretsen L, Ma R. Nonsurgical or Surgical Treatment of ACL Injuries. 2014:1233–1241. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.M.01054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ageberg E, Thomeé R, Neeter C, Silbernagel KG, Roos EM. Muscle strength and functional performance in patients with anterior cruciate ligament injury treated with training and surgical reconstruction or training only: a two to five-year followup. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59(12):1773–1779. doi: 10.1002/art.24066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Neeter C, Gustavsson A, Thomeé P, Augustsson J, Thomeé R, Karlsson J. Development of a strength test battery for evaluating leg muscle power after anterior cruciate ligament injury and reconstruction. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2006;14(6):571–580. doi: 10.1007/s00167-006-0040-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tsepis E, Vagenas G, Ristanis S, Georgoulis AD. Thigh muscle weakness in ACL-deficient knees persists without structured rehabilitation. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006;450(450):211–218. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000223977.98712.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ageberg E, Pettersson A, Fridén T. 15-Year Follow- Up of Neuromuscular Function in Patients With Unilateral Nonreconstructed Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injury Initially Treated With Rehabilitation and Activity Modification: a Longitudinal Prospective Study. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35(12):2109–2117. doi: 10.1177/0363546507305018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Muaidi QI, Nicholson LL, Refshauge KM, Herbert RD, Maher CG. Prognosis of conservatively managed anterior cruciate ligament injury: a systematic review. Sports Med. 2007;37(8):703–716. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200737080-00004. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17645372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tagesson S, Oberg B, Good L, Kvist J. A comprehensive rehabilitation program with quadriceps strengthening in closed versus open kinetic chain exercise in patients with anterior cruciate ligament deficiency: a randomized clinical trial evaluating dynamic tibial translation and muscle function. Am J Sports Med. 2008;36(2):298–307. doi: 10.1177/0363546507307867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fitzgerald GK, Axe MJ, Snyder-Mackler L. A decision-making scheme for returning patients to high-level activity with nonoperative treatment after anterior cruciate ligament rupture. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2000;8(2):76–82. doi: 10.1007/s001670050190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fitzgerald GK, Axe MJ, Snyder-Mackler L. Proposed practice guidelines for nonoperative anterior cruciate ligament rehabilitation of physically active individuals. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2000;30(4):194–203. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2000.30.4.194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moksnes H, Snyder-Mackler L, Risberg MA. Individuals with an anterior cruciate ligament-deficient knee classified as noncopers may be candidates for nonsurgical rehabilitation. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2008;38(10):586–595. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2008.2750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moksnes H, Risberg Ma. Performance-based functional evaluation of non-operative and operative treatment after anterior cruciate ligament injury. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2009;19(3):345–355. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2008.00816.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eitzen I, Moksnes H, Snyder-Mackler L, Engebretsen L, Risberg MA. Functional tests should be accentuated more in the decision for ACL reconstruction. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2010;18(11):1517–1525. doi: 10.1007/s00167-010-1113-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Keays SL, Bullock-Saxton JE, Keays AC, Newcombe Pa, Bullock MI. A 6-year follow-up of the effect of graft site on strength, stability, range of motion, function, and joint degeneration after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: patellar tendon versus semitendinosus and Gracilis tendon graft. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35(5):729–739. doi: 10.1177/0363546506298277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hopper DM, Strauss GR, Boyle JJ, Bell J. Functional recovery after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a longitudinal perspective. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2008;89(8):1535–1541. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2007.11.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Logerstedt DS, Snyder-Mackler L, Ritter RC, Axe MJ, Godges JJ. Knee stability and movement coordination impairments: knee ligament sprain. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2010;40(4):A1–A37. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2010.0303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wright RW, Gill CS, Chen L, et al. Outcome of Revision Anterior Cruciate Ligament. 2012:531–536. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.K.00733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mauro CS, Irrgang JJ, Williams Ba, Harner CD. Loss of extension following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: analysis of incidence and etiology using IKDC criteria. Arthroscopy. 2008;24(2):146–153. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2007.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Spindler KP, Huston LJ, Wright RW, et al. The Prognosis and Predictors of Sports Function and Activity at Minimum 6 Years After Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction A Population Cohort Study. Am J Sports Med. 2010:1–12. doi: 10.1177/0363546510383481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Frobell RB, Roos HP, Roos EM, Roemer FW, Ranstam J, Lohmander LS. Treatment for acute anterior cruciate ligament tear : five year outcome of randomised trial. Br Med J. 2013 Jan;232:1–12. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Logerstedt DS, Snyder-Mackler L, Ritter RC, Axe MJ. Knee pain and mobility impairments: meniscal and articular cartilage lesions. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2010;40(6):A1–A35. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2010.0304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Barenius B, Ponzer S, Shalabi A, Bujak R, Norlén L, Eriksson K. Increased risk of osteoarthritis after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a 14-year follow-up study of a randomized controlled trial. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(5):1049–1057. doi: 10.1177/0363546514526139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chalmers PN, Mall NA, Moric M, et al. Does ACL Reconstruction Alter Natural History? 2014:292–300. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.L.01713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bradley JP, Klimkiewicz JJ, Rytel MJ, Powell JW. Anterior cruciate ligament injuries in the National Football League: epidemiology and current treatment trends among team physicians. Arthroscopy. 2002;18(5):502–509. doi: 10.1053/jars.2002.30649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shah VM, Andrews JR, Fleisig GS, McMichael CS, Lemak LJ. Return to play after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction in National Football League athletes. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38(11):2233–2239. doi: 10.1177/0363546510372798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ardern CL, Taylor NF, Feller Ja, Webster KE. Fifty-five per cent return to competitive sport following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction surgery: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis including aspects of physical functioning and contextual factors. Br J Sports Med. 2014:1–11. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2013-093398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McCullough Ka, Phelps KD, Spindler KP, et al. Return to high school- and college-level football after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a Multicenter Orthopaedic Outcomes Network (MOON) cohort study. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(11):2523–2529. doi: 10.1177/0363546512456836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shelbourne KD, Sullivan aN, Bohard K, Gray T, Urch SE. Return to basketball and soccer after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction in competitive school-aged athletes. Sports Health. 2009;1(3):236–241. doi: 10.1177/1941738109334275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brophy RH, Schmitz L, Wright RW, et al. Return to play and future ACL injury risk after ACL reconstruction in soccer athletes from the Multicenter Orthopaedic Outcomes Network (MOON) group. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(11):2517–2522. doi: 10.1177/0363546512459476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Warner SJ, Smith MV, Wright RW, Matava MJ, Brophy RH. Sport-specific outcomes after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Arthroscopy. 2011;27(8):1129–1134. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2011.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dunn WR, Spindler KP. Predictors of activity level 2 years after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction (ACLR): a Multicenter Orthopaedic Outcomes Network (MOON) ACLR cohort study. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38(10):2040–2050. doi: 10.1177/0363546510370280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Webster KE, Feller Ja, Leigh WB, Richmond AK. Younger patients are at increased risk for graft rupture and contralateral injury after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(3):641–647. doi: 10.1177/0363546513517540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Laboute E, Savalli L, Puig P, et al. Analysis of return to competition and repeat rupture for 298 anterior cruciate ligament reconstructions with patellar or hamstring tendon autograft in sportspeople. Ann Phys Rehabil Med. 2010;53(10):598–614. doi: 10.1016/j.rehab.2010.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Paterno MV, Rauh MJ, Schmitt LC, Ford KR, Hewett TE. Incidence of Second ACL Injuries 2 Years After Primary ACL Reconstruction and Return to Sport. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(7):1567–1573. doi: 10.1177/0363546514530088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wright RW, Dunn WR, Amendola A, et al. Risk of tearing the intact anterior cruciate ligament in the contralateral knee and rupturing the anterior cruciate ligament graft during the first 2 years after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a prospective MOON cohort study. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35(7):1131–1134. doi: 10.1177/0363546507301318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Paterno MV, Schmitt LC, Ford KR, et al. Biomechanical measures during landing and postural stability predict second anterior cruciate ligament injury after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction and return to sport. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38(10):1968–1978. doi: 10.1177/0363546510376053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bourke HE, Salmon LJ, Waller A, Patterson V, Pinczewski La. Survival of the anterior cruciate ligament graft and the contralateral ACL at a minimum of 15 years. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(9):1985–1992. doi: 10.1177/0363546512454414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shelbourne KD, Gray T, Haro M. Incidence of subsequent injury to either knee within 5 years after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with patellar tendon autograft. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37(2):246–251. doi: 10.1177/0363546508325665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wright RW, Magnussen Ra, Dunn WR, Spindler KP. Ipsilateral graft and contralateral ACL rupture at five years or more following ACL reconstruction: a systematic review. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93(12):1159–1165. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.J.00898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Leys T, Salmon L, Waller A, Linklater J, Pinczewski L. Clinical results and risk factors for reinjury 15 years after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a prospective study of hamstring and patellar tendon grafts. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(3):595–605. doi: 10.1177/0363546511430375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Borchers JR, Kaeding CC, Pedroza AD, Huston LJ, Spindler KP, Wright RW. Intra-articular findings in primary and revision anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction surgery: a comparison of the MOON and MARS study groups. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39(9):1889–1893. doi: 10.1177/0363546511406871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Smith TO, Postle K, Penny F, McNamara I, Mann CJV. Is reconstruction the best management strategy for anterior cruciate ligament rupture? A systematic review and meta-analysis comparing anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction versus non-operative treatment. Knee. 2014;21(2):462–470. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2013.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Eitzen I, Moksnes PH. A Progressive 5-Week Exercise Therapy Program Leads to Significant Improvement in Knee Function Early After Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injury. J Orthop Sport Phys Ther. 2010;40(2):705–721. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2010.3345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]