Abstract

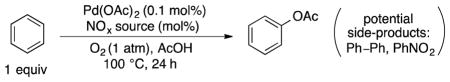

Palladium-catalyzed methods for C–H oxygenation with O2 as the stoichiometric oxidant are limited. Here, we describe the use of nitrite and nitrate sources as NOx-based redox mediators in the acetoxylation of benzene. The conditions completely avoid formation of biphenyl as a side product, and strongly favor formation of phenyl acetate over nitrobenzene (PhOAc:PhNO2 ratios up to 40:1). Under the optimized reaction conditions, with 0.1 mol% Pd(OAc)2, 136 turnovers of Pd are achieved with only 1 atm of O2 pressure.

Keywords: oxidation, aerobic, palladium, benzene, phenyl acetate, phenol, C–H activation, redox mediators, nitrate, nitrite, nitric acid

1. Introduction

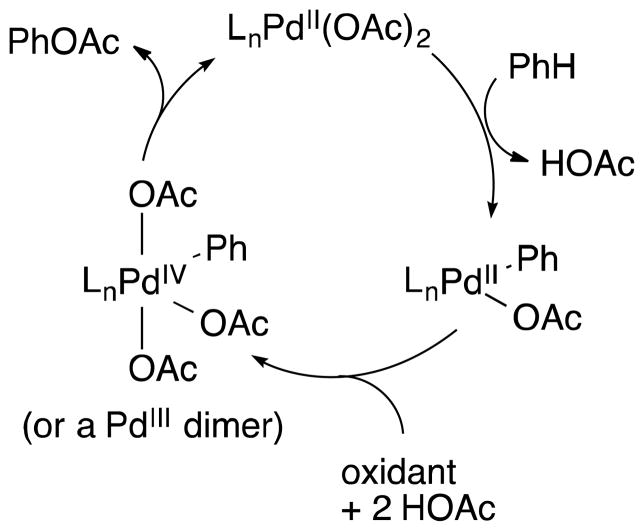

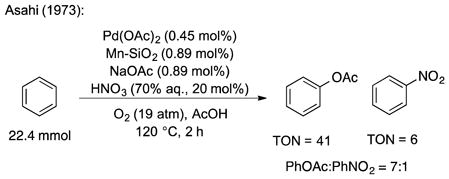

Direct, selective oxidation of benzene to phenol and other oxygenates has been a major focus of attention in catalysis research [1], and palladium-catalyzed routes have shown significant promise [2]. Pd-catalyzed activation of an sp2 C–H bond in benzene generates a phenyl-PdII species that can be trapped by various stoichiometric oxidants, such as PhI(OAc)2 and persulfate, to afford phenyl-PdIII or -PdIV species. These high-valent intermediates undergo facile C–O reductive elimination to afford phenyl acetate and related oxygenation products (Figure 1) [3], [4], [5]. The development of an effective method for benzene oxygenation capable of using O2 as the oxidant remains a prominent challenge and goal of contemporary research [6].

Figure 1.

General proposed reaction mechanism for palladium-catalyzed benzene C–H acetoxylation.

Precedents for Pd-catalyzed oxygenation of benzene with O2 as the oxidant are relatively limited [7], and the best examples typically require very high (unsafe) O2 pressures. For example, Fujiwara disclosed Pd(OAc)2/1,10-phenanthroline-catalyzed selective synthesis of phenol with O2 in combination with CO as a sacrificial reductant [15 atm of each, turnover numbers (TON) = 12] [8]. Yin recently reported a Pd(OAc)2/2,2′-bipyrimidine-catalyzed process using 20 atm of O2, where selectivity was diverted from biphenyl to phenol when redox-inactive metals such as aluminum triflate were included in the reaction mixture (TON = 10.6) [9]. The most effective methods to date, however, employ Pd(OAc)2 in combination with a heteropolyacid (HPA), H3+x[PMo12–xVxO40], cocatalyst. Schuchardt used a heteropolyacid with a vanadium content of x = 3.3 to achieve up to 600 Pd turnovers for phenol formation, although a very high O2 pressure (60 atm) was required [10]. Kozhevnikov showed that a different HPA (x = 2) could shift the reaction from preferential biphenyl formation to phenol formation by increasing the water content in a H2O:AcOH solvent mixture [11]. In this case, only modest turnovers (TON ≤ 23) for phenol formation were observed, at 5 atm O2. Finally, Ashland Oil patented the oxygenation of benzene with longer chain carboxylic acids. The reaction was performed in the presence of catalytic Pd(OAc)2, Sb(OAc)3 and Cr(OAc)3 at a low pressure of O2 (1 atm), achieving up to 90 turnovers with octanoic acid [12].

Pd-catalyzed oxidation of benzene under aerobic conditions typically affords biphenyl as the major reaction product [13]. A particular challenge in realizing a high-turnover process for benzene oxygenation is the typical inability of O2 to react directly with phenyl-palladium(II) species to afford a high-valent species that can undergo facile C–O bond formation. Recently, well-defined organopalladium(II) complexes with multidentate ligands have been shown to react with O2 to afford organopalladium(III) and/or organopalladium(IV) complexes [ 14 ], [ 15 ]; however, the specialized ligands used to achieve these transformations exhibit limited or no catalytic reactivity [16].

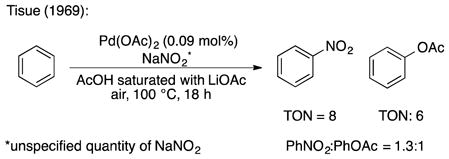

A number of historical and recent studies suggest that nitrogen oxide (NOx) species [17] could serve as effective cocatalysts or stoichiometric mediators in aerobic palladium-catalyzed C–H oxidation reactions. For example, Bao recently used sodium nitrite as a cocatalyst to achieve aerobic trifluoroacetoxylation of methane [18] and Sanford used sodium nitrate as an additive in ligand-directed aerobic acetoxylation of sp3 C-H bonds [19]. Older precedents exist for application of similar concepts in the oxidation of benzene. In 1969, Tisue reported Pd(OAc)2-catalyzed oxidation of benzene in the presence of sodium nitrite, leading to formation of nitrobenzene in preference to phenyl acetate (PhNO2:PhOAc = 1.3:1; TON = 6, with respect to PhOAc) [20]. Asahi later published a patent in which they described preferential formation of phenyl acetate over nitrobenzene (PhOAc:PhNO2 = 7:1; TON = 41, with respect to PhOAc) under modified conditions, most notably using a very high pressure of O2 (19 atm) [21], [22]. More recently, NOx-based reaction partners have been used in palladium-catalyzed, ligand-directed C–H nitration reactions [23]. Collectively, these results highlight the ability of NOx species to promote carbon-heteroatom bond formation in Pd-catalyzed C–H oxidation; however, they also draw attention to potential challenges in controlling product selectivity.

|

(1) |

|

(2) |

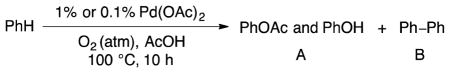

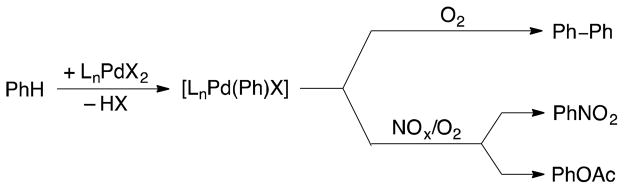

In the present study, we explore the use of NOx-based cocatalysts in the palladium-catalyzed aerobic oxidation of benzene to phenyl acetate. Of particular interest is the identification of reaction conditions that use low pressures of O2 and achieve high selectivity for phenyl acetate relative to the potential by-products biphenyl and nitrobenzene (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Potential products from the reaction of benzene with Pd/O2/NOx. Top (undesired) pathway: dimerization. Middle (undesired) pathway: nitration. Lower (desired) pathway: acetoxylation.

2. Results and discussion

Our initial studies of palladium-catalyzed oxidation of benzene were carried out in the absence of NOx sources in order to establish benchmarks for benzene reactivity with Pd(OAc)2. Benzene was dissolved in acetic acid (1:29 molar ratio) and heated to 100 °C in the presence of 1 mol% Pd(OAc)2 and 1 atm of O2. These conditions exhibited low conversion of benzene to oxidation products, resulting in 0.4 turnovers to biphenyl and phenol/phenyl acetate in a 1:1 ratio of C–O:C–C coupling products (Table 1, entry 1). A minor improvement was observed when Pd(OAc)2 was decreased to 0.1 mol% loading. The C–O coupling products were slightly favored over biphenyl (1.7:1); however, the overall reactivity still remained low (TON = 1.2). Negligible changes were observed when the O2 partial pressure was increase to 10 atm (entry 3).

Table 1.

Pd-catalyzed aerobic oxidative coupling of benzene in acetic acid: Product ratios in the absence of a redox mediator.

7 mmol scale; see SI for additional information.

“1 atm O2” = 11 atm of 9% O2 in N2.

“10 atm O2” = 111 atm of 9% O2 in N2.

Based on combined GC yields of PhOAc, PhOH, and Ph-Ph.

The latter results suggests that C–O coupling does not result from direct reaction of O2 with a phenyl-palladium(II) intermediate and is consistent with previous observations that O2 is kinetically inert toward direct reaction with organopalladium(II) species [24]. The origin of the small quantities of benzene oxygenation products in these reactions is not currently understood.

We then turned our attention to reactions incorporating NOx-based cocatalysts (Table 2). When Pd(OAc)2 (1 mol%) was used with 10 mol% of tert-butyl nitrite as a NOx source under 1 atm of O2, benzene oxidation exhibited a strong preference for phenyl acetate formation over nitrobenzene and biphenyl side products, PhOAc:PhNO2:Ph–Ph 10:1:0.8 (Table 2, entry 1; only trace phenol was detected). None of these oxidation products are observed if the same reaction is performed in the absence of Pd(OAc)2. This observation shows that nitrobenzene formation is a palladium-catalyzed process and does not arise from electrophilic nitration under the reaction conditions. Recent mechanistic studies of palladium-catalyzed aerobic oxidative coupling of arenes revealed that biaryl formation proceeds via a bimetallic process involving transmetalation between two LnPdIIArX species [25]. Therefore, we conjectured that biphenyl formation could be minimized by reducing the catalyst loading. When the Pd(OAc)2 and tert-butyl nitrite loadings were reduced to 0.1 and 1 mol%, respectively, no biphenyl was observed, and the TON with respect to PhOAc formation increased from 4 to 21. A similar PhOAc:PhNO2 selectivity was observed (PhOAc:PhNO2 = 8.4:1, entry 2). Increasing the O2 partial pressure from 1 to 10 atm led to a slight increase in the palladium TON (26), but the PhOAc:PhNO2 ratio improved to 27:1 (entry 3). Other changes to the reaction conditions, especially focused on the catalyst loading and identity of the NOx source, did not lead to significant improvements (entries 4–9).

Table 2.

Pd(OAc)2/NOx-catalyzed aerobic acetoxylation of benzene with low NOx loading.

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | %Pda | % NOx | O2 (atm)b | TON (Pd)c | PhOAc:PhNO2d |

| 1 | 1.0 | 10% t-BuONO | 1 | 4.0 | 10:1e |

| 2 | 0.1 | 1% t-BuONO | 1 | 21 | 8.4:1 |

| 3 | 0.1 | 1% t-BuONO | 10 | 26 | 27:1 |

| 4 | 0.1 | 1% n-pentylONO | 10 | 25 | 25:1 |

| 5 | 0.1 | 1% NaNO3 | 10 | 23 | 26:1 |

| 6 | 0.1 | 1% fuming HNO3 | 10 | 15 | 22:1 |

| 7 | 0.05 | 0.5% t-BuONO | 10 | 22 | 25:1 |

| 8 | 0.2 | 2% t-BuONO | 10 | 21 | 11:1 |

| 9 | 0.1 | 0.5% t-BuONO | 10 | 12 | 33:1 |

Entries 1 & 2 were conducted in sealed pressure tubes with teflon caps (1.75 mmol scale; 0.55 M). Entries 3–9 were conducted in Parr reactor vessels (7 mmol scale; 0.55 M). No PhOAc or PhNO2 is observed in the absence of Pd(OAc)2.

For entries 3–9, “10 atm O2” = 111 atm of 9% O2 in N2.

TONs were calculated based on calibrated GC yields of PhOAc.

Based on the ratio of calibrated GC yields.

Ratio of PhOAc:Ph–Ph (mmol) is 10:0.8. For all other entries, biphenyl is not observed.

The active NOx species appears to decompose under the reaction conditions, and addition of another dose of NOx (in this case, tert-butyl nitrite) reinitiates the reaction [26]. This observation, together with the modest turnover numbers observed in Table 1 prompted us to investigate the use of larger quantities of NOx sources for the reaction. In addition, we elected to focus on low- pressure reaction conditions (pO2 = 1 atm).

Use of 30 mol% tert-butyl nitrite under 1 atm O2, however, resulted in low catalyst turnover (Table 3, entry 1). We speculated that this poor result could reflect the deleterious consequence of generating larger quantities of tert-butoxyl radicals in the formation of NO from tert-butyl nitrite [27]. Therefore, other NOx sources were tested. When 30 mol% NaNO3 was employed, the turnover number increased to 59 and led to a PhOAc:PhNO2 ratio of 9:1 (entry 2) [28]. Further improvements were observed upon using 30 mol% HNO3 (70% in H2O), which led to a turnover number of 115 (entry 3). The best results were obtained with 30 mol% fuming HNO3, which led to a turnover number of 136 (entry 4). The selectivity for PhOAc over PhNO2 remained very good under these conditions (PhOAc:PhNO2 = 26:1, entry 4), in spite of the presence of a large quantity of NOx. Only traces of diacetoxylated products were detected, even when the yield of PhOAc surpasses 10%. Varying the mol% of fuming HNO3 led to modest reductions in turnover number (entries 5–7). When the optimized conditions, with 30 mol% fuming nitric acid, were conducted under N2 instead of O2, nitrobenzene is the major product (PhOAc:PhNO2 = 1:1.2; entry 7). This result shows that the NOx species can serve as competent oxidants, but they favor C–N bond formation, rather than C–O bond formation in the absence of O2. The optimized conditions in Table 3, entry 4 afford a 13.6% yield of phenyl acetate, which compares favorably to previous methods for palladium-catalyzed oxidation of benzene to phenyl acetate using PhI(OAc)2 and potassium persulfate as stoichiometric oxidants (7.5% [5a] and 7.1% [5f] yields, respectively). Additionally, the optimized conditions from entry 4 can be conducted under 1 atm of air instead of O2, adjusting the temperature to 85 °C, to afford a still high turnover number of 120, while the PhOAc:PhNO2 ratio improved to 40:1 (entry 9).

Table 3.

Pd-catalyzed and NOx-mediated aerobic acetoxylation of benzene: Optimization of turnover numbers.

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Entrya | % NOx | TON (Pd)b | PhOAc:PhNO2c |

| 1 | 30% t-BuONO | 4 | 4:1 |

| 2 | 30% NaNO3 | 59 | 9:1 |

| 3 | 30% aq. HNO3 (70%) | 115 | 25:1 |

| 4d | 30% fuming HNO3 | 136 | 26:1 |

| 5 | 10% fuming HNO3 | 100 | 29:1 |

| 6 | 50% fuming HNO3 | 127 | 22:1 |

| 7 | 70% fuming HNO3 | 116 | 18:1 |

| 8 | 30% fuming HNO3; N2 (1 atm) instead of O2 | 19 | 1:1.2 |

| 9e | 30% fuming HNO3, 85 °C, air (1 atm) instead of O2 | 120 | 40:1 |

1.2 mmol scale; 0.55 M. Reactions were conducted in sealed pressure tubes with teflon caps. Biphenyl is not observed.

TONs were calculated based on calibrated GC yields of PhOAc.

Based on the ratio of calibrated GC yields.

Average of four experiments. Standard deviation for TON: 9.9. Standard deviation for ratio of PhOAc:PhNO2: 3.3

13.56 mmol scale; 0.55 M. Reaction was conducted in a flask equipped with a reflux condenser. Biphenyl is not observed.

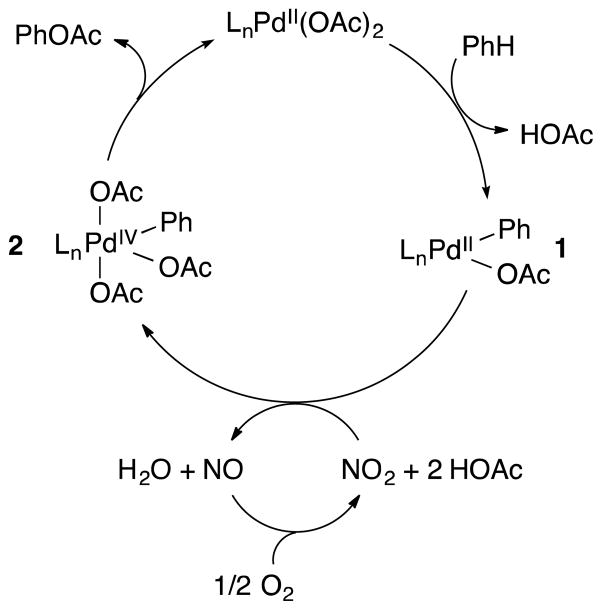

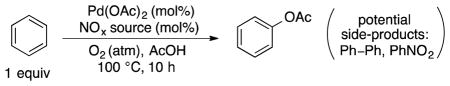

A likely catalytic cycle for Pd(OAc)2/NOx-catalyzed oxidation of benzene to phenyl acetate is illustrated in Figure 3. Benzene C-H activation by palladium(II) [LnPd(OAc)2] affords a phenyl-palladium(II) intermediate. Two-electron oxidation of 1 by NO2 could then generate a phenyl-palladium(IV) species 2, which can undergo facile C–O reductive elimination to afford phenyl acetate and the original LnPd(OAc)2 catalyst. This proposed catalytic cycle mirrors other proposed PdII/IV (and PdII/PdIII dimer) cycles for arene and alkane oxygenation, in which various oxidants (e.g. PhI(OAc)2) are used to generate species similar to 2 [3a]. The proposed catalytically relevant oxidant NO2 can be generated via thermal decomposition of HNO3 (eq 3) [29], and the reduced NOx species NO is well known to undergo facile aerobic oxidation to NO2 [17].

Figure 3.

A possible catalytic cycle for palladium-catalyzed, NOx-mediated benzene C–H acetoxylation.

| (3) |

The direct involvement of NO2 (or other NOx species) in oxidizing the phenyl-palladium(II) intermediate is supported by the observation of significant catalytic turnover (TON = 19), when the reaction is carried out in the absence of O2. Furthermore, increased formation of nitrobenzene under these conditions (together with the lack of background nitration in the absence of palladium) implicates N-coordination of a NOx species to palladium, which then participates in C–N reductive elimination. The change in PhOAc:PhNO2 product selectivity under N2 suggests that O2 plays a role beyond oxidation of NO to NO2.

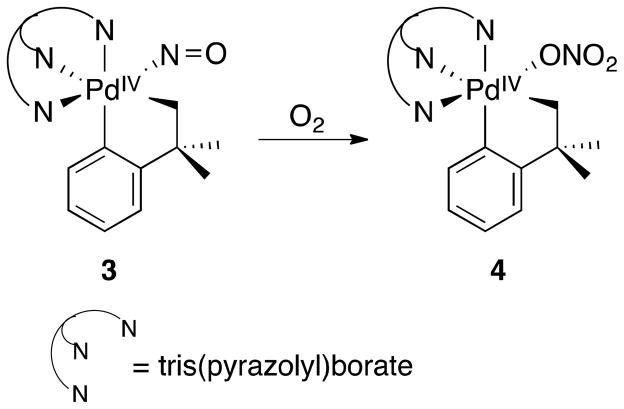

In Table 2, increasing the O2 pressure resulted in an improvement of the PhOAc:PhNO2 ratio from 8.4:1 to 27:1 (entries 2 vs 3). Similarly, in Table 3, altering the reaction conditions from an O2 to a N2 atmosphere (1 atm in each case), significantly decreased the PhOAc:PhNO2 product ratio from 26:1 to 1:1.2 (entries 4 vs 8) [30]. The reaction of NOx species with organopalladium complexes has received relatively little attention, but fundamental studies of Campora and coworkers potentially provide insights into the selectivity trends just noted [31]. A nitrosyl-organopalladium(IV) complex bearing a tris(pyrazolyl)borate ancillary ligand (3) was synthesized and shown to react with O2 to afford the corresponding O-bound nitrate complex 4 (Figure 4). Anaerobic conditions could result in accumulation of NO, which could then coordinate to organopalladium species and lead to C–N bond formation (the details of which are not yet understood). In the presence of O2, nitric oxide could convert to NO2 via direct oxidation by molecular oxygen, as shown in Figure 3, or a bound nitrosyl ligand could undergo oxidation to a nitrate ligand within the palladium coordination sphere, as shown in Figure 4. Either pathway could result in preferential C–O reductive elimination with a more-basic acetate ligand (cf. Figure 3).

Figure 4.

NOx-bound organopalladium(IV) complexes synthesized by Campora. In the presence of O2, 3 converts to 4.

3. Conclusions

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that NOx sources serve as effective redox mediators for palladium-catalyzed aerobic acetoxylation of benzene under only 1 atm of O2. Promising turnover numbers of >100 and high selectivities for phenyl acetate have been achieved. Biphenyl formation is negligible under these reaction conditions, and phenyl acetate to nitrobenzene ratios of up to 40:1 are accessible.

4. Experimental

General considerations

The following reagents were purchased and used as received: benzene (Aldrich, anhydrous, 100-mL sure-seal bottles), acetic acid (Aldrich, >99.99%, trace metals basis), nitric acid (Aldrich, red fuming), palladium(II) acetate (Strem). The use of these high-purity reagents is extremely important in order to achieve optimal results. All reactions using 1 atm of pure O2 were carried out in oven-dried Ace pressure tubes (9 mL, bushing type, front seal, 20.3 cm L x 13 mm O.D.). All reactions using 9% O2/N2 were carried out in a Series 5000 Multiple Reactor System (Parr Instrument Company) using 45-mL Hastelloy C-276 vessels. GC analyses were carried out on a Shimadzu Gas Chromatograph GC-1010 Plus, with a Phenomenex Zebron ZB-Wax column (30 m L × 0.25 mm ID × 0.25 μm df).

Note: 1) It is important that the ratio of solution:headspace for these reactions be between 1:1.8 and 1:3.5 in order to achieve optimal results. 2) Because NOx species will react with rubber, it is important that teflon caps, and not septa, be used for these reactions.

Reactions were optimized with respect to temperature, concentration, and ratio of solution:headspace (not shown).

Table 1: General procedure

A 45-mL Hastelloy C-276 vessel was charged with a teflon stirbar, the specified mol% of Pd(OAc)2, as indicated in Table 2 (it is easiest to use a stock solution of Pd(OAc)2/AcOH), a total of 12.1 mL of AcOH, and benzene (626 μl, 7 mmol). The reactor was sealed, pressurized to either 11 atm or 111 atm of 9% O2/N2 (effectively 1 atm of O2 or 10 atm of O2), and then heated to 100 °C and stirred vigorously for 10 h. The vessel was then allowed to cool to room temperature and the reaction mixture was analyzed by GC analysis using chlorobenzene as an internal standard. TONs are reported based on mmol PhOAc + mmol PhOH + mmol Ph–Ph. Ratios of (PhOAc + PhOH):Ph–Ph are based on mmol of products.

Table 2, entries 1 & 2: General procedure

An oven-dried Ace pressure tube (9 mL, bushing type, front seal, 20.3 cm L x 13 mm O.D.) was charged with a teflon stirbar, the specified mol% of Pd(OAc)2 as indicated in Table 2 (it is easiest to use a stock solution of Pd(OAc)2/AcOH), and a total of 3.0 mL of AcOH. The tube was capped with a septum and purged for 2 minutes with an oxygen balloon, while stirring. Benzene (158 μl, 1.75 mmol) was added via syringe, followed by the specified quantity of the NOx source. The rubber septum was removed, quickly capped with a Teflon cap, and stirred vigorously in a 100 °C oil bath for 10 h (the oil bath level is the same height as the solution level of the reaction). The pressure tube was then allowed to cool to room temperature and the reaction mixture was analyzed by GC analysis using chlorobenzene as an internal standard. TONs are reported solely based on mmol PhOAc. Ratios of PhOAc:PhNO2 are based on mmol of products.

Table 2, entries 3–9: General procedure

A 45-mL Hastelloy C-276 vessel was charged with a teflon stirbar, the specified mol% of Pd(OAc)2 as indicated in Table 2 (it is easiest to use a stock solution of Pd(OAc)2/AcOH), a total of 12.1 mL of AcOH, benzene (626 μl, 7 mmol), and the specified quantity of the NOx source. The reactor was sealed, pressurized to 111 atm of 9% O2/N2, and then heated to 100 °C and stirred vigorously for 10 h. The vessel was then allowed to cool to room temperature and the reaction mixture was analyzed by GC analysis using chlorobenzene as an internal standard. TONs are reported solely based on mmol PhOAc. Ratios of PhOAc:PhNO2 are based on mmol of products.

Table 3: General procedure

An oven-dried Ace pressure tube (9 mL, bushing type, front seal, 20.3 cm L × 13 mm O.D.) was charged with a teflon stirbar, 100 μl of a 0.00012 M Pd(OAc)2/AcOH stock solution (stock solution: 26.9 mg in 10 mL of AcOH; 0.0012 mmol Pd(OAc)2 per reaction), and 1.9 mL of AcOH. The tube was capped with a septum and purged for 2 minutes with an oxygen balloon, while stirring (exception: for entry 8, N2 was used in place of O2). Benzene (108 μl, 1.2 mmol) was added via syringe, followed by the specified quantity of the NOx source, via syringe. The rubber septum was removed, quickly capped with a Teflon cap, and stirred vigorously in a 100 °C oil bath for 24 h (the oil bath level is the same height as the solution level of the reaction). The pressure tube was then allowed to cool to room temperature and the reaction mixture was analyzed by GC analysis using chlorobenzene as an internal standard. TONs are reported solely based on mmol PhOAc. Ratios of PhOAc:PhNO2 are based on mmol of products.

*Entry 4 is the average of 4 runs:

Run 1: TON = 137; 28:1 PhOAc:PhNO2

Run 2: TON = 136; 26:1 PhOAc:PhNO2

Run 3: TON = 121; 30:1 PhOAc:PhNO2

Run 4: TON = 149; 21:1 PhOAc:PhNO2

Standard deviation for TON: 9.9

Standard deviation for PhOAc:PhNO2 ratio: 3.3

Table 3, entry 9: Procedure

An oven-dried 100-mL round-bottom flask was charged with a teflon stirbar, 500 μl of a 0.027 M Pd(OAc)2/AcOH stock solution (stock solution: 30.4 mg in 5 mL of AcOH; 0.0136 mmol Pd(OAc)2 per reaction), AcOH (22.7 mL), benzene (1.21 mL, 13.56 mmol), and fuming HNO3 (173 μL, 4.07 mmol). The flask was equipped with a reflux condenser (open top) and stirred vigorously in a 85 °C oil bath for 24 h. The mixture was then allowed to cool to room temperature and the reaction mixture was analyzed by GC analysis using chlorobenzene as an internal standard. TONs are reported solely based on mmol PhOAc. Ratios of PhOAc:PhNO2 are based on mmol of products.

Note: In a more rigorous approach for reactions run in Ace pressure tubes, Ace pressure tubes with plunger valves (e.g. Ace glass manufacturer #8648-164) were used. In this case, a pressure tube was charged with a Teflon stirbar, Pd(OAc)2, AcOH, PhH and the NOx source. The tube was sealed with a Teflon cap containing a plunger valve. The top of the plunger valve was connected to a three-way valve; one valve connected to a vacuum pump, and one valve connected to an O2 balloon. The reaction mixture was frozen using a dry ice bath, evacuated under reduced pressure with the plunger valve open, and then backfilled with 1 atm of pure O2 The plunger valve was closed and the reaction mixture was allowed to warm to room temperature. This evacuation/backfilling with O2 procedure was conducted two more times, and then the sealed reaction mixture was stirred vigorously in a 100 °C oil bath for the indicated time. The pressure tube was then allowed to cool to room temperature and the reaction mixture was analyzed by GC analysis using chlorobenzene as an internal standard. Results using this approach were comparable to the less rigorous approach using Ace pressure tubes with simple Teflon caps.

Pd-catalyzed aerobic oxidation of benzene in acetic acid to phenyl acetate is enabled by the inclusion of NOx-based redox mediators, achieving up to 136 turnovers.

Phenyl acetate is strongly favored over the formation of the side product nitrobenzene (PhOAc:PhNO2 ratios up to 40:1), and the potential byproduct biphenyl is not observed.

High pressures of O2 are not required; good reactivity is observed with air as the source of O2.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health (R01-GM067173 to S.S.S. and a Ruth L. Kirchstein National Service Award (F32-GM109569) to S.L.Z.).

Footnotes

Dedicated to the memory of Alexander E. Shilov, an inspirational scientist who had a profound impact on the field of catalysis.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.(a) Weissermel K, Arpe H-J. Industrial Organic Chemistry. 4. Wiley-VCH; New York: 2003. [Google Scholar]; (b) Weber M, Weber M, Kleine-Boymann M. Phenol In Ullmann’s Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. 2004;26:503–519. [Google Scholar]; (c) Schmidt RJ. App Catal A. 2005;280:89–103. [Google Scholar]

- 2.For a review on transition metal catalyzed synthesis of hydroxylated arenes, see: Alonso DA, Nájera C, Pastor IM, Yus M. Chem Eur J. 2010;16:5274–5284. doi: 10.1002/chem.201000470.

- 3.For reviews on PdII/IV and PdII/III C–H activation chemistry in catalysis, see: Muñiz K. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2009;48:9412–9423. doi: 10.1002/anie.200903671.Lyons TW, Sanford MS. Chem Rev. 2010;110:1147–1169. doi: 10.1021/cr900184e.Engle KM, Mei TS, Wasa M, Yu JQ. Acc Chem Res. 2012;45:788–802. doi: 10.1021/ar200185g.Powers DC, Ritter T. Acc Chem Res. 2012;45:840–850. doi: 10.1021/ar2001974.

- 4.For a general review on C–H activation of simple arenes, including Pd-catalyzed processes, see: Kuhl N, Hopkinson MH, Wencel-Delord J, Glorius F. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2012;51:10236–10254. doi: 10.1002/anie.201203269.

- 5.For examples of palladium-catalyzed C–H oxygenation of simple arenes, see: Yoneyama T, Crabtree RH. J Mol Catal A. 1996;108:35–40.Shibahara F, Kinoshita S, Nozaki K. Org Lett. 2004;6:2437–2439. doi: 10.1021/ol049166l.Emmert MH, Cook AK, Xie YJ, Sanford MS. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2011;50:9409–9412. doi: 10.1002/anie.201103327.Tato F, García-Domínguez A, Cárdenas DJ. Organometallics. 2013;32:7487–7494.Cook AK, Emmert MH, Sanford MS. Org Lett. 2013;15:5428–5431. doi: 10.1021/ol4024248.Gary JB, Cook AK, Sanford MS. ACS Catal. 2013;3:700–703.

- 6.(a) Cornils B, Herrmann WA. J Catal. 2003;216:23–31. [Google Scholar]; (b) Lücke B, Narayana KV, Martin A, Jähnisch K. Adv Synth Catal. 2004;346:1407–1484. [Google Scholar]

- 7.For examples in which low (≤ 5) turnover numbers were observed, see: Pachkovskaya LN, Matveev KI, Il’inich GN, Eremenko NK. Kinet Catal. 1977;18:1040–1043.Liang P, Xiong H, Guo H, Yin G. Catal Commun. 2010;11:560–562.

- 8.(a) Jintoku T, Taniguchi H, Fujiwara Y. Chem Lett. 1987:1865–1868. [Google Scholar]; (b) Jintoku T, Takaki K, Fujiwara Y, Fuchita Y, Hiraki K. Bull Chem Soc Jpn. 1990;63:438–441. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guo H, Chen Z, Mei F, Zhu D, Xiong H, Yin G. Chem Asian J. 2013;8:888–891. doi: 10.1002/asia.201300003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Passoni LC, Cruz AT, Buffon R, Schuchardt U. J Mol Catal A. 1997;120:117–123. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burton HA, Kozhevnikov IV. J Mol Catal A. 2002;185:285–290. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ashland Oil, Inc., Ashland, KY. . US Patent 4,465,633. Manufacture of aryl esters. 1984 Aug 14;

- 13.For leading references, see: Mukhopadhyay S, Rothenberg G, Lando G, Agbaria K, Kazanci M, Sasson Y. Adv Synth Catal. 2001;343:455–459.Yokota T, Sakaguchi S, Ishii Y. Adv Synth Catal. 2002;344:849–854.Izawa Y, Stahl SS. Adv Synth Catal. 2010;352:3223–3229. doi: 10.1002/adsc.201000771.

- 14.For fundamental studies of LnPdMe2 complexes that react directly with O2, including the formation of well defined PdIII or PdIV products, see: Boisvert L, Denney MC, Hanson SK, Goldberg KI. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:15802–15814. doi: 10.1021/ja9061932.Khusnutdinova JR, Rath NP, Mirica LM. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:2414–2422. doi: 10.1021/ja210841f.Khusnutdinova JR, Qu F, Zhang Y, Rath NP, Mirica LM. Organometallics. 2012;31:4627–4630.Tang F, Zhang Y, Rath NP, Mirica LM. Organometallics. 2012;31:6690–6696.

- 15.For a stoichiometric reaction of a LnPdII(aryl)(alkyl) species with O2, see: Qu F, Khusnutdinova JR, Rath NP, Mirica LM. Chem Commun. 2014;50:3036–3039. doi: 10.1039/c3cc49387c.

- 16.For examples of ligand-directed, catalytic C–H oxygenation reactions using O2 as the oxidant, see: Zhang J, Khaskin E, Anderson NP, Zavalij PY, Vedernikov AN. Chem Commun. 2008:3625–3627. doi: 10.1039/b803156h.Zhang YH, Yu YQ. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:14654–14655. doi: 10.1021/ja907198n.Wang D, Zavalij PY, Vedernikov AN. Organometallics. 2013;32:4882–4891.

- 17.Bohle DS. The Nitrogen Oxides: Persistant Radicals and van der Waals Complex Dimers. In: Hicks RG, editor. Stable Radicals: Fundamental and Applied Aspects of Odd-Electron Compounds. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; UK: 2010. pp. 147–171. [Google Scholar]

- 18.An Z, Pan X, Liu X, Han X, Bao X. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:16028–16029. doi: 10.1021/ja0647912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stowers KJ, Kubota A, Sanford MS. Chem Sci. 2012;3:3192–3195. doi: 10.1039/C2SC20800H. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tisue T, Downs WJ. Chem Commun. 1969:410. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Asahi Kasei Co., Osaka, Japan. US Patent 3,772,383. Process for preparing phenyl esters of aliphatic carboxylic acids. 1973 Nov 13;

- 22.For additional examples, see: Gulf Research & Development Company, Pittsburgh, PA. US Patent 3,542,852. Process for the preparation of aromatic esters. 1970 Nov 24; (yields for PhOAc are <1%)Asahi Kasei Co., Tokyo, Japan. US Patent 3,887,608. Process for preparing phenyl acetate and related products. 1975 Jun 3; (PhOAc TON = 9 or less)

- 23.(a) Zhang W, Lou S, Liu Y, Xu Z. J Org Chem. 2013;78:5932–5948. doi: 10.1021/jo400594j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Zhang W, Wu D, Zhang J, Liu Y. Eur J Org Chem. 2014:5827–5835. [Google Scholar]; (c) Majhi B, Kundu D, Ahammed S, Ranu BC. Chem Eur J. 2014;20:9862–9866. doi: 10.1002/chem.201403325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Diao T, Stahl SS. Polyhedron. 2014;84:96–102. doi: 10.1016/j.poly.2014.06.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang D, Izawa Y, Stahl SS. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:9914–9917. doi: 10.1021/ja505405u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.A reaction using the same conditions as those described in Table 2, entry 2, was run to approximately 70% completion (3h), at which point an additional 1 mol% tert-butyl nitrite was added. This resulted in an improvement in the Pd TON to 32, as compared to 21 in Table 2, entry 2. In contrast, addition of another aliquot of palladium does not results in improved turnover numbers, indicating that the limitation in these reactions is associated with the NOx source, not the palladium source.

- 27.Uchiumi S-i, Ataka K, Matsuzaki T. J Organomet Chem. 1999;576:279–289. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Metal nitrites such as NaNO2 afforded variable results due to their spontaneous room temperature reaction with acetic acid to generate NO, NO2 and H2O, lending to a difficult reaction setup.

- 29.(a) Theimann M, Scheibler E, Weigland KW. Nitric Acid, Nitrous Acid, and Nitrogen Oxides. Ullmann’s Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry, Wiley-VCH; Weinheim: 2005. [Google Scholar]; (b) Laue W, Theimann M, Schiebler E, Wiegland KW. Nitrates and Nitrites. Ullmann’s Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry, Wiley-VCH; Weinheim: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Note: the reaction conducted under N2 is not completely devoid of O2, as O2 is generated via HNO3 thermal decomposition: 4 HNO3 → 2 H2O + 4 NO2 + O2).

- 31.Campora J, Palma P, del Rio D, Carmona E, Graiff C, Tiripicchio A. Organometallics. 2003;22:3345–3347. [Google Scholar]