“Of all of the forms of inequality, injustice in health is the most shocking and inhumane.”

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

March 12, 2015 will mark the 10th anniversary of World Kidney Day (WKD), an initiative of the International Society of Nephrology and the International Federation of Kidney Foundations. Since its inception in 2006, WKD has become the most successful effort ever mounted to raise awareness among decision-makers and the general public about the importance of kidney disease. Each year WKD reminds us that kidney disease is common, harmful and treatable. The focus of WKD 2015 is on chronic kidney disease (CKD) in disadvantaged populations. This article reviews the key links between poverty and CKD and the consequent implications for the prevention of kidney disease and the care of kidney patients in these populations.

Chronic kidney disease is increasingly recognized as a global public health problem and a key determinant of the poor health outcomes. There is compelling evidence that disadvantaged communities, that is, those from low resource, racial and minority ethnic communities, and/or indigenous and socially disadvantaged backgrounds, suffer from marked increases in the burden of unrecognized and untreated CKD. Although the entire population of some low and middle-income countries could be considered disadvantaged, further discrimination on the basis of local factors creates a position of extreme disadvantage for certain population groups (peasants, those living in some rural areas, women, the elderly, religious minorities, etc). The fact that even in developed countries, racial and ethnic minorities bear a disproportionate burden of CKD and have worse outcomes, suggests there is much to learn beyond the traditional risk factors contributing to CKD-associated complications.[1]

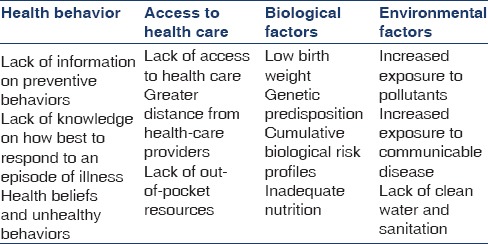

About 1.2 billion people live in extreme poverty worldwide. Poverty negatively influences healthy behaviors, health care access and environmental exposure, all of which contribute to health care disparities[2] [Table 1]. The poor are more susceptible to disease because of lack of access to goods and services, in particular clean water and sanitation, information about preventive behaviors, adequate nutrition, and reduced access to health care.[3]

Table 1.

Possible mechanisms by which poverty increases the burden of disease

Chronic Kidney Disease in Developed Countries

In the US, ethnic minorities have a higher incidence of end stage renal disease (ESRD). Despite similar prevalence rates for early stages of CKD,[4] poor outcomes such as ESRD are 1.5–4 times higher[2,5,6,7] among minorities (i.e. African-American, Hispanic and Native Americans). Poverty further increases the disparity in ESRD rates, with African-Americans being at greater risk.[8] In the UK, rates of treated ESRD are higher in ethnic minority groups and with increasing social deprivation.[9] Similarly in Singapore, CKD prevalence is higher among Malays and Indians compared to the Chinese, with socioeconomic and behavioral factors accounting for 70–80% of the excess risk.[10]

End stage renal disease incidence is also higher among the less advantaged indigenous populations in developed countries. Canadian First Nations people experience ESRD at rates 2.5–4 times higher than the general population.[11] In Australia, the increase in the number of indigenous people starting renal replacement therapy (RRT) over the past 25 years exceeded that of the nonindigenous population by 3.5-fold, largely due to a disproportionate (>10-fold) difference in ESRD due to type II diabetic nephropathy, a disease largely attributable to lifestyle issues such as poor nutrition and lack of exercise.[12] Indigenous populations also have a higher incidence of ESRD due to glomerulonephritis and hypertension.[13] Compared to the US general population, the ESRD incidence rate is higher in Guam and Hawaii, where the proportion of indigenous people is high, again driven primarily by diabetic ESRD.[14] Native Americans have a greater prevalence of albuminuria and higher ESRD incidence rate.[15,16,17,18] Nearly three-quarters of all incident ESRD cases among this population have been attributable to type II diabetes.

Chronic Kidney Disease in Developing Countries

Poverty-related factors such as infectious diseases secondary to poor sanitation, inadequate supply of safe water, environmental pollutants and high concentrations of disease-transmitting vectors continue to play an important role in the development of CKD in low-income countries. Although rates of diabetic nephropathy are rising, chronic glomerulonephritis and interstitial nephritis are among the principal causes of CKD in many countries. Of note is the emergence of HIV-associated nephropathy as the major cause of CKD in sub-Saharan Africa.[19]

A high prevalence of CKD of unknown etiology has been reported in rural agricultural communities from Central America, Egypt, India and Sri Lanka. Male farm workers are affected disproportionately, and the clinical presentation is suggestive of interstitial nephritis, confirmed on renal biopsies. The strong association with farm work has led to suggestions that exposure to agrochemicals, dehydration, and consumption of contaminated water might be responsible.[20] Additionally, the use of traditional herbal medications is common and frequently associated with CKD among the poor.[21,22] In Mexico, CKD prevalence among the poor is 2–3-fold higher than the general population, and the etiology is unknown in 30% of ESRD patients.[23,24,25,26]

Low-Birth Weight and Risk of Chronic Kidney Disease in the Disadvantaged Populations

An association between low birth weight (LBW) due primarily to nutritional factors and kidney disease has been described in disadvantaged populations. The frequency of LBW is more than double in the aboriginal population than in the non-Aboriginal population of Australia. The high prevalence of albuminuria in this population has been linked to low nephron number related to LBW.[27,28] Morphometric studies of kidney biopsies in the Aboriginals show glomerulomegaly, perhaps secondary to nephron deficiency, which might predispose to glomerulosclerosis.[29,30] A correlation between LBW and CKD has also been described in poor African-Americans and Caucasians living in the Southeastern US.[31] Similarly, in an Indian cohort, LBW and early malnutrition were associated with later development of metabolic syndrome, diabetes and diabetic nephropathy.[32] The finding of a high prevalence of proteinuria, elevated blood pressure and CKD of unknown etiology in South Asian children may also be explained by this mechanism.[33,34]

Disparities in Access to Renal Replacement Therapy

A recent analysis shows that globally, there were 2.6 million people on dialysis in 2010, 93% in high or upper middle-income countries. By contrast, the number of people requiring RRT was estimated at 4.9-9 million, suggesting that at least 2.3 million died prematurely because of lack of access to RRT. Even though diabetes and hypertension increase the burden of CKD, the current provision of RRT is linked largely to two factors - per capita GNP and age, suggesting that poverty is a major disadvantage for receiving RRT. By 2030, the number of people receiving RRT around the world is projected to increase to 5.4 million. Most of this increase will be in developing countries of Asia and Africa.[35]

Access to RRT in the emerging world is dependent mostly on the health care expenditures and economic strength of individual countries, with the relationship between income and access to RRT being almost linear in low and middle-income countries.[19,36] In Latin America, RRT prevalence and kidney transplantation rates correlate significantly with gross national income and health expenditure,[37] while in India and Pakistan <10% of all ESRD patients have access to RRT.[38] Additionally, developing countries have low transplant rates because of a combination of low levels of infrastructure; geographical remoteness; lack of legislation governing brain death; religious, cultural and social constraints; and commercial incentives that favor dialysis.[39]

There are also differences in utilization of renal replacement modalities between indigenous and nonindigenous groups in the developed countries. In Australia and New Zealand, the proportion of people receiving home dialysis is considerably lower among indigenous people. At the end of 2007 in Australia, 33% of nonindigenous people requiring RRT were receiving home-based dialysis therapies, in contrast to 18% of Aboriginal people. In New Zealand, home-based dialysis was utilized by 62% of nonindigenous RRT population but only by 42% of Maori/Pacific Islanders.[12] The rate of kidney transplantation is also lower among disadvantaged communities. Maori and Pacific people are only 25% as likely to get a transplant as European New Zealanders, and the proportion of indigenous people who underwent transplantation and had a functioning kidney transplant is lower among Aboriginal Australians (12%) compared to nonindigenous Australians (45%). In the UK, white individuals from socially deprived areas, South Asians and blacks were all less likely to receive a preemptive renal transplant or living donor transplants than their more affluent white counterparts.[9] A multinational study found that when compared with white patients, the likelihood of receiving a transplant for Aboriginal patients was 77% lower in Australia and New Zealand, and 66% lower in Canadian First Nations individuals.[40]

Disparities in renal care are more evident in developing nations. Data from India shows that there are fewer nephrologists and nephrology services in the poorer states. As a result, people living in these states are likely to receive less care.[41] In Mexico, the fragmentation of the health care system has resulted in unequal access to RRT. In the state of Jalisco, the acceptance and prevalence rates in the more economically advantaged insured population were higher (327 pmp and 939 pmp, respectively) than for patients without medical insurance (99 pmp and 166 pmp, respectively) The transplant rate also was dramatically different, at 72 pmp for those with health insurance and 7.5 pmp for those without it.[42]

The Bidirectional Relationship Between Poverty and Chronic Kidney Disease

In addition to having a higher disease burden, the poor have limited access to resources for meeting the treatment costs. A large proportion of patients who are forced to meet the expensive ESRD treatment costs by incurring out-of-pocket expenditure, get pushed into extreme poverty. In one Indian study, over 70% patients undergoing kidney transplantation experienced catastrophic health care expenditures.[43] Entire families felt the impact of this, including job losses and interruptions in education of children,

Outcomes

Overall mortality rates among those who do receive RRT are higher in the indigenous, minorities, and the uninsured populations, even after adjustment for co-morbidities. The hazard ratios for death on dialysis relative to the nonindigenous group are 1.4 for Aboriginal Australians and New Zealand Maori.[44] The Canadian First Nations patients achieve target levels for BP and mineral metabolism less frequently.[45] In the US, living in predominantly black neighborhoods was associated with higher than expected mortality rates on dialysis and increased time to transplantation.[46] Similarly, black patients on PD had a higher risk of death or technique failure compared to whites.[47]

In Mexico, the mortality on PD is 3-fold higher among the uninsured population compared to Mexican patients receiving treatment in the US, and the survival rate is significantly lower than the insured Mexican population,[48] while in India almost two-thirds of the patients are unable to continue dialysis beyond the first 3 months due to financial reasons.[49]

Summary

The increased burden of CKD in disadvantaged populations is due to both global factors and population-specific issues. Low socioeconomic status and poor access to care contribute to health care disparities, and exacerbate the negative effects of genetic or biologic predisposition. Provision of appropriate renal care to these populations requires a two-pronged approach: Expanding the reach of dialysis through development of low-cost alternatives that can be practiced in remote locations, and implementation and evaluation of cost-effective prevention strategies. Kidney transplantation should be promoted by expanding deceased donor transplant programs and use of inexpensive, generic immunosuppressive drugs. The message of WKD 2015 is that a concerted attack against the diseases that lead to ESRD, by increasing community outreach, better education, improved economic opportunity, and access to preventive medicine for those at highest risk, could end the unacceptable relationship between CKD and disadvantage in these communities.

References

- 1.Pugsley D, Norris KC, Garcia-Garcia G, Agodoa L. Global approaches for understanding the disproportionate burden of chronic kidney disease. Ethn Dis. 2009;19:S1–1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Crews DC, Charles RF, Evans MK, Zonderman AB, Powe NR. Poverty, race, and CKD in a racially and socioeconomically diverse urban population. Am J Kidney Dis. 2010;55:992–1000. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2009.12.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sachs JD. Report of the Commission on Macroeconomics and Health. Geneva: WHO; 2001. Macroeconomics and Health: Investing in Health for Economic Development. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kalantar-Zadeh K, Block G, Humphreys MH, Kopple JD. Reverse epidemiology of cardiovascular risk factors in maintenance dialysis patients. Kidney Int. 2003;63:793–808. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00803.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hsu CY, Lin F, Vittinghoff E, Shlipak MG. Racial differences in the progression from chronic renal insufficiency to end-stage renal disease in the United States. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14:2902–7. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000091586.46532.b4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Norris K, Nissenson AR. Race, gender, and socioeconomic disparities in CKD in the United States. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19:1261–70. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008030276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bruce MA, Beech BM, Crook ED, Sims M, Wyatt SB, Flessner MF, et al. Association of socioeconomic status and CKD among African Americans: The Jackson Heart Study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2010;55:1001–8. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2010.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Volkova N, McClellan W, Klein M, Flanders D, Kleinbaum D, Soucie JM, et al. Neighborhood poverty and racial differences in ESRD incidence. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19:356–64. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006080934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Caskey FJ. Renal replacement therapy: Can we separate the effects of social deprivation and ethnicity? Kidney Int Suppl (2011) 2013;3:246–49. doi: 10.1038/kisup.2013.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sabanayagam C, Lim SC, Wong TY, Lee J, Shankar A, Tai ES. Ethnic disparities in prevalence and impact of risk factors of chronic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2010;25:2564–70. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfq084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gao S, Manns BJ, Culleton BF, Tonelli M, Quan H, Crowshoe L, et al. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease and survival among aboriginal people. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18:2953–9. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007030360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McDonald S. Incidence and treatment of ESRD among indigenous peoples of Australasia. Clin Nephrol. 2010;74(Suppl 1):S28–31. doi: 10.5414/cnp74s028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Collins JF. Kidney disease in Maori and Pacific people in New Zealand. Clin Nephrol. 2010;74(Suppl 1):S61–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weil EJ, Nelson RG. Kidney disease among the indigenous peoples of Oceania. Ethn Dis. 2006;16(Suppl 2):S24–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.United States Renal Data System: USRDS 2006 Annual Data Report. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, National Institutes of Health. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kasiske BL, Rith-Najarian S, Casper ML, Croft JB. American Indian heritage and risk factors for renal injury. Kidney Int. 1998;54:1305–10. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1998.00106.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nelson RG, Morgenstern H, Bennett PH. An epidemic of proteinuria in Pima Indians with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Kidney Int. 1998;54:2081–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1998.00191.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scavini M, Shah VO, Stidley CA, Tentori F, Paine SS, Harford AM, et al. Kidney disease among the Zuni Indians: The Zuni Kidney Project. Kidney Int Suppl. 2005;(Suppl 97):S126–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.09721.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jha V, Garcia-Garcia G, Iseki K, Li Z, Naicker S, Plattner B, et al. Chronic kidney disease: Global dimension and perspectives. Lancet. 2013;382:260–72. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60687-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Almaguer M, Herrera R, Orantes CM. Chronic kidney disease of unknown etiology in agricultural communities. MEDICC Rev. 2014;16:9–15. doi: 10.37757/MR2014.V16.N2.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ulasi II, Ijoma CK, Onodugo OD, Arodiwe EB, Arodiwe EB, Ifebunandu NA, et al. Towards prevention of chronic kidney disease in Nigeria; a community-based study in Southeast Nigeria. Kidney Int Suppl. 2013;3:195–201. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Otieno LS, McLigeyo SO, Luta M. Acute renal failure following the use of herbal medicines. East Afr Med J. 1991;6:993–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Obrador GT, García-García G, Villa AR, Rubilar X, Olvera N, Ferreira E, et al. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease in the Kidney Early Evaluation Program (KEEP) México and comparison with KEEP US. Kidney Int Suppl. 2010;77:S2–8. doi: 10.1038/ki.2009.540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gutierrez-Padilla JA, Mendoza-Garcia M, Plascencia-Perez S, Renoirte-Lopez K, Garcia-Garcia G, Lloyd A, et al. Screening for CKD and cardiovascular disease risk factors using mobile clinics in Jalisco, Mexico. Am J Kidney Dis. 2010;55:474–84. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2009.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.García-García G, Gutiérrez-Padilla AJ, Chávez-Iñiguez J, Pérez-Gómez HR, Mendoza-García M, González-De la Peña Mdel M, et al. Identifying undetected cases of chronic kidney disease in Mexico. Targeting high-risk populations. Arch Med Res. 2013;44:623–7. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2013.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Amato D, Alvarez-Aguilar C, Castañeda-Limones R, Rodriguez E, Avila-Diaz M, Arreola F, et al. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease in an urban Mexican population. Kidney Int Suppl. 2005;(Suppl 97):S11–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.09702.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hoy W, McDonald SP. Albuminuria: Marker or target in indigenous populations. Kidney Int Suppl. 2004:S25–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.09207.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McDonald SP, Maguire GP, Hoy WE. Renal function and cardiovascular risk markers in a remote Australian Aboriginal community. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2003;18:1555–61. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfg199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hoy WE, Samuel T, Mott SA, Kincaid-Smith PS, Fogo AB, Dowling JP, et al. Renal biopsy findings among Indigenous Australians: A nationwide review. Kidney Int. 2012;82:1321–31. doi: 10.1038/ki.2012.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hoy WE, Hughson MD, Zimanyi M, Samuel T, Douglas-Denton R, Holden L, et al. Distribution of volumes of individual glomeruli in kidneys at autopsy: Association with age, nephron number, birth weight and body mass index. Clin Nephrol. 2010;74(Suppl 1):S105–12. doi: 10.5414/cnp74s105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lackland DT, Bendall HE, Osmond C, Egan BM, Barker DJ. Low birth weights contribute to high rates of early-onset chronic renal failure in the Southeastern United States. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:1472–6. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.10.1472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bhargava SK, Sachdev HS, Fall CH, Osmond C, Lakshmy R, Barker DJ, et al. Relation of serial changes in childhood body-mass index to impaired glucose tolerance in young adulthood. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:865–75. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa035698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jafar TH, Chaturvedi N, Hatcher J, Khan I, Rabbani A, Khan AQ, et al. Proteinuria in South Asian children: Prevalence and determinants. Pediatr Nephrol. 2005;20:1458–65. doi: 10.1007/s00467-005-1923-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jafar TH, Islam M, Poulter N, Hatcher J, Schmid CH, Levey AS, et al. Children in South Asia have higher body mass-adjusted blood pressure levels than white children in the United States: A comparative study. Circulation. 2005;111:1291–7. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000157699.87728.F1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liyanage T, Ninomiya T, Jha V, Patrice HM, Okpechi I, Zhao M, et al. Worldwide access to treatment for end stage kidney disease: A systematic review. Lancet. 2015 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61601-9. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Barsoum RS. Chronic kidney disease in the developing world. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:997–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp058318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cusumano AM, Garcia-Garcia G, Gonzalez-Bedat MC, Marinovich S, Lugon J, Poblete-Badal H, et al. Latin American Dialysis and Transplant Registry: 2008 prevalence and incidence of end-stage renal disease and correlation with socioeconomic indexes. Kidney Int Suppl (2011) 2013;3:153–56. doi: 10.1038/kisup.2013.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jha V. Current status of end-stage renal disease care in India and Pakistan. Kidney Int Suppl. 2013;3:157–60. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Garcia GG, Harden P, Chapman J. World Kidney Day Steering Committee 2012. The global role of kidney transplantation. Lancet. 2012;379:e36–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60202-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yeates KE, Cass A, Sequist TD, McDonald SP, Jardine MJ, Trpeski L, et al. Indigenous people in Australia, Canada, New Zealand and the United States are less likely to receive renal transplantation. Kidney Int. 2009;76:659–64. doi: 10.1038/ki.2009.236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jha V. Current status of chronic kidney disease care in southeast Asia. Semin Nephrol. 2009;29:487–96. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2009.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Garcia-Garcia G, Monteon-Ramos JF, Garcia-Bejarano H, Gomez-Navarro B, Reyes IH, Lomeli AM, et al. Renal replacement therapy among disadvantaged populations in Mexico: A report from the Jalisco Dialysis and Transplant Registry (REDTJAL) Kidney Int Suppl. 2005;(Suppl 97):S58–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.09710.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ramachandran R, Jha V. Kidney transplantation is associated with catastrophic out of pocket expenditure in India. PLoS One. 2013;8:e67812. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0067812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McDonald SP, Russ GR. Burden of end-stage renal disease among indigenous peoples in Australia and New Zealand. Kidney Int Suppl. 2003;(Suppl 97):S123–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.63.s83.26.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chou SH, Tonelli M, Bradley JS, Gourishankar S, Hemmelgarn BR. Alberta Kidney Disease Network. Quality of care among Aboriginal hemodialysis patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;1:58–63. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00560705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rodriguez RA, Sen S, Mehta K, Moody-Ayers S, Bacchetti P, O'Hare AM. Geography matters: Relationships among urban residential segregation, dialysis facilities, and patient outcomes. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146:493–501. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-7-200704030-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mehrotra R, Story K, Guest S, Fedunyszyn M. Neighborhood location, rurality, geography, and outcomes of peritoneal dialysis patients in the United States. Perit Dial Int. 2012;32:322–31. doi: 10.3747/pdi.2011.00084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Garcia-Garcia G, Briseño-Rentería G, Luquín-Arellan VH, Gao Z, Gill J, Tonelli M. Survival among patients with kidney failure in Jalisco, Mexico. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18:1922–7. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006121388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Parameswaran S, Geda SB, Rathi M, Kohli HS, Gupta KL, Sakhuja V, et al. Referral pattern of patients with end-stage renal disease at a public sector hospital and its impact on outcome. Natl Med J India. 2011;24:208–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]