Abstract

Aims:

To evaluate and compare the push-out bond strength of root filled with Endosequence BC, AH Plus and Endomethasone N sealers using lateral condensation and thermoplasticized technique.

Materials and Methods:

Thirty mandibular premolars with completely formed roots were selected. Teeth were decoronated, working length was determined. Instrumentation and irrigation were performed. Teeth were then obturated with Group 1-Cold lateral compaction (n = 15) or Group 2-Thermoplasticized technique (n = 15). Each group was again subdivided into three depending on the sealers used. Teeth in each subgroup were then sectioned perpendicularly to the long axis to obtain a disc of 2 mm each, which were then subjected to micro push-out test. Data was analyzed with ANOVA.

Results:

AH Plus sealer in Group 1 showed the maximum (4.77 ± 1.67 MPa) push-out bond strength among the three sealers and between two groups. The mean strength of Bioceramic sealer was lower in Group 1 (2.62 ± 0.76 MPa) and higher in Group 2 (3.52 ± 0.69 MPa).

Conclusions:

The push-out bond strength of Endosequence BC sealer was lower than the AH Plus root canal sealer with cold lateral condensation technique.

Keywords: AH Plus sealer, endosequence BC sealer, lateral condensation, push-out test, thermoplasticized technique

INTRODUCTION

Over the past century, numerous obturation materials and delivery techniques have been introduced in dentistry. The continued research on obturation materials is based on the concept that, the primary cause for failure of Root Canal Treatment is the apical migration of microorganisms and their by-products in a poorly filled and leaking root canal obturation.[1,2,3] To overcome this, Grossman studied the physical properties of filling materials and found adhesion to be a very desirable property in root canal cements.[4] Caicedo and von Fraunhofer have also stated that the endodontic cements must seal the root canal space and, ideally, should adhere to both the gutta-percha cone and the canal walls.[5]

With this concept, Monoblock was introduced in endodontics by Tay and Pashley who further classified it into primary, secondary and tertiary depending on the number of interfaces present between the bonding substrate and the bulk core material.[6] Epoxy resin type sealers have been used for many years. They showed higher bond strength to dentin than zinc oxide eugenol types, calcium hydroxide-based and glass-ionomer sealers.[7,8,9]

Recently, Endosequence BC sealer (Brasseler USA, Savannah, GA), previously known as iRoot SP (Innovative Bioceramix, Vancouver, Canada), has been introduced, which is described by its manufacturer as an insoluble, radiopaque, aluminum-free material composed of calcium, calcium phosphate, calcium hydroxide and zirconium oxide that requires the presence of water to set and harden.[10] Also Endosequence BC sealer show alkaline pH, antibacterial activity, radio-opacity and biocompatibility.[11] The apical sealing ability[12] and the push-out bond strength of iRoot SP sealer were found to be equivalent to that of AH Plus sealer.[13]

With the increasing trend of using thermoplasticized technique to obtain a three-dimensional filling of the root canal system, this study aimed to evaluate the push-out bond strength of Endosequence BC sealer with lateral condensation and thermoplasticized technique and comparing it with AH Plus sealer (Dentsply DeTrey GmbH, Konstanz, Germany) and Endomethasone N sealer (Septodont).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Thirty extracted sound-matured human mandibular first premolars were used for this study. Teeth were sectioned transversely below the cemento-enamel junction, to obtain a standardized root length of 15 mm. Canal patency and working length were established by inserting a 15 K file in the canal until its tip could be seen through the apical foramen under operating microscope (Seiler) at 12X magnification. The tooth length was then checked and 1 mm was subtracted to determine the working length. Instrumentation was completed using Protaper Rotary files (Dentsply) up to F3 at working length. The canals were irrigated with 2 ml of 3% sodium hypochlorite (Neelkanth Health Care (P.) LTD., India) during instrumentation. After preparation, canals were filled with 5 ml of 17% ethylene diamine tetra-acetic acid (Ammdent) for 1 min to remove the smear layer, and the final flush was performed using 5 ml of distilled water. It was then dried with absorbent paper points (Dentsply) of 0.06 taper 30 size.

Thirty teeth were then divided into two groups (15 teeth/group) according to the obturation technique employed. In Group 1 canals were filled using Cold Lateral Condensation technique and in Group 2 it was obturated using thermoplasticized technique. These groups were then further divided into subgroups according to the sealers used, i. e., Endosequence BC sealer (Brasseler USA, Savannah, GA), AH Plus sealer (Dentsply DeTrey GmbH, Konstanz, Germany) and Endomethasone N sealer (Septodont).

In group I, the master cone of size 30, 0.06 taper (Dentsply-Tulsa Dental, Tulsa, OK) was selected. Canals were then coated with sealer using lentulo-spiral (Dentsply-Tulsa Dental, Tulsa, OK) and master cone was introduced up to the working length. After this, a 25-size finger spreader (Dentsply-Tulsa Dental, Tulsa, OK) was introduced vertically to create space for accessory GP. Accessory GP cones were then coated with sealer and introduced into the canal. In group II roots filled with thermoplasticized technique Calamus obturating delivery system (Dentsply-Tulsa Dental, Tulsa, OK) was used. The canal walls were coated with sealer, and master cone of size 30, 0.06 taper was introduced till working length. Master cone was then seared of at the level of orifice using a heated plugger tip and this heated plugger tip was further pressed through the thermo softened GP until the silicon stop is 2mm from the reference point. This was followed by back filling done using Calamus Flow delivery system to optimally fill the canal. After obturation, teeth were placed immediately at 37°C and 100% humidity for 48 hours, to allow the sealers to set completely.

Each roots were then divided into 3 segments of 2 mm each using diamond disc. Thus, each group comprised 45 samples and subgroup comprised 15 samples (n = 15) for each subgroup). Thus, total 90 samples were prepared.

Sample preparation

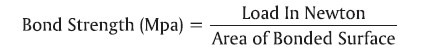

The root slices were then mounted on acrylic block of 1.5 × 1.5 mm dimension. The shear bond strength was then tested with micro push-out technique by using universal testing machine (Star testing System, 248). This was accomplished by using a 0.7 and 0.4 mm diameter cylindrical stainless steel plunger of length 4 mm. A constant compressive load at a speed of 1 mm/min was applied until bond failure occurred. The disk specimens were positioned to allow plunger to move in apical to the coronal direction. The bond strength was determined using a computer software program. The bond strength was recorded in Mpa according to Skidmore et al., by dividing the load in Newton by the area of bonded interface using the following formula.[14]

Failure analysis

Failure mode was analyzed by examining each debonded specimen under a stereomicroscope (2.0 Stereomicroscope with Image analyzer software, Microscope, Vardhan, India) at 25× magnification. Failures were classified according to Skidmore et al., as Type 1: Adhesive failure (at sealer dentin interface), Type 2: Cohesive failure (within sealer or dentin interface) and Type 3: Mixed failure.[14]

The mean and standard deviations for the push-out bond strength were obtained for the three sealer types in each study group. To determine the effect of groups and sealers, as well as their interaction effect, two-way analysis of variance was performed. The statistical significance of fixed and interaction effects were evaluated at 5% level, and the analysis was carried out using SPSS 11.0 (SPSS Inc.).

RESULTS

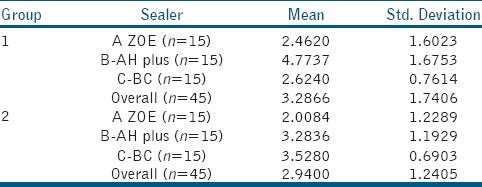

The bond strength values for each groups are given in Table 1. The mean bond strength for AH Plus sealer in Group 1 was maximum (4.77 ± 1.67 MPa) among the three sealers and between the two groups. The mean strength of Endosequence BC sealer was lower in Group 1 (2.62 ± 0.76 MPa) and higher in Group 2 (3.52 ± 0.69 MPa).

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for bond strength according to groups and sealers

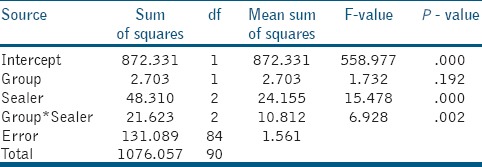

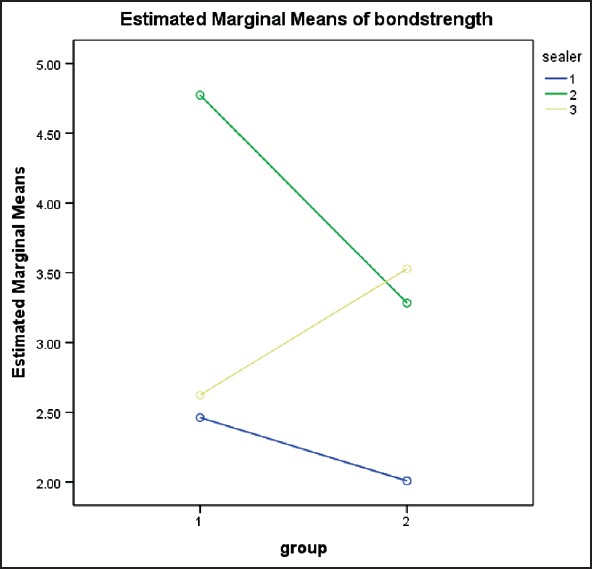

To determine whether the group effect, sealer effect and their interaction are statistically significant, two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed with the results shown in Table 2. The analysis revealed that the group effect was statistically insignificant (P value = 0.192), while sealer effect was significant (P value < 0.001). Further, the interaction effect of group and sealer was also significant (P value = 0.002). The visualization of interaction effect is shown through line plots graph [Figure 1].

Table 2.

Two-way ANOVA for bond strength

Figure 1.

Line plots showing the mean push-out strength for three sealer types in two study groups

Failure analysis showed the predominant failure mode to be cohesive failure for Endosequence BC sealer and AH Plus sealer; and adhesive failure for Endomethasone N sealer.

DISCUSSION

Adhesion of root canal filling material is important in both the static situation to eliminate any space that allows the percolation of fluids in between fillings and walls[15] and dynamic situation to resist the dislodgement of filling during subsequent manipulation.[16] Extrusion testing in dentistry was first described by Roydhouse.[17] The push-out test is based on the shear stress at the interface between dentine and cement,[18] which is comparable with stresses under clinical conditions.[19] Model used in this study is similar to one used by Ungor et al., which is effective and reproducible and can also evaluate the root canal sealers with a low bond strength.[16]

A measurable adhesive property was seen in all the groups in this study. It was seen that the mean push-out strength of AH plus in Group 1 (Cold lateral condensation) was higher as compared to Group 2 (Thermoplasticized technique), while the mean strength of Endosequence BC sealer was lower in Group 1 as compared to Group 2 and moreover it was higher than that of AH plus in Group 2 resulting into a significant interaction. Thus, the group effect was prominent for AH plus and Endosequence BC sealer. The behavior of ZOE in two groups was similar to that of AH plus, but the magnitudes of push-out strength for ZOE was much lower as compared to that of AH plus in both the groups.

Numerous studies have shown AH Plus to have higher bond strength than most other sealers.[7,8] In the present study, AH Plus sealer showed significant higher bond strength than Endosequence BC sealer and Endomethasone N sealer when used with cold lateral compaction. The higher bond strength obtained with AH Plus may be associated with its ability to react with any exposed amino groups in collagen to form covalent bonds between the resin and collagen upon opening of the epoxide ring.[9] Epoxy-based resin sealer penetrates deeper into the dentinal tubules due to its flowability and long-term polymerization time, which might contribute to enhancing the mechanical interlocking between the sealer and dentin.[20] Thus, a very low shrinkage while setting and long-term dimensional stability shown by AH Plus might also contribute to its observed bond strength. The results of this study do not correlate with that of the study by Sagsen et al.,[21] in which no statistical significant difference was observed between AH Plus sealer and iRoot SP with lateral condensation.

Endosequence BC sealer showed a reasonably good bond strength as compared to ZOE-based sealer, because of its true self-adhesive nature, which forms a chemical bond (through production of hydroxyapatite during setting) with dentine.[12] Also it is hydrophilic, posseses low contact angle allowing it to spread easily over the canal walls providing adaptation and good hermetic seal.[11] In an in vitro study done by Ghoneim et al., it was seen that the resistance to vertical fracture of roots obturated with iRoot SP (Bioceramic-based sealer) and ActiV GP cones was comparable to that of intact teeth.[22] So it can be said that, the lower value achieved in group 1 can be attributed to the Endosequence BC sealer as it does not bond with the gutta-percha cones, but if Bioceramic cones or ActiV GP cones were used, the bond strength might have increased.

The findings in this literature are in accordance with the study results of Kaya et al., which also showed that warm techniques did not affect the push-out bond strengths.[23] Considering the interaction effect between the technique and root filling material, AH plus sealer showed significantly higher bond strength to intraradicular dentin when used with lateral condensation as compared to thermoplasticized technique, as reported by Carneiro et al.,[20] and De-Deus et al.,[24] When warm technique is used for obutration, there is accelerated polymerization of resin-based sealers. Thus the rapid setting causes decrease in flow, increases stiffness and hence does not allow time for relief of shrinkage stress via resin flow, resulting in low bond strength of AH Plus with thermoplasticized technique.

In general, the high bond strength material, which are adhesive to the dentine shows cohesive failure as per Lee et al.,[7] Thus, both Endosequence BC sealer and AH Plus sealer showed mostly cohesive or mixed failure, whereas Endomethasone N showed adhesive failure.

Since, uptil now no other known study has been performed using Endosequence BC sealer and thermoplasticized obturation technique, the higher bond strength achieved by Endosequence BC sealer with thermoplastcized technique remains unexplainable and requires further investigation.

CONCLUSION

Within the limit of this study,

AH Plus sealer along with cold lateral condensation showed the highest bond strength. (P < 0.05).

The push-out bond strength of Endosequence BC sealer was higher than AH Plus when thermoplasticized technique was used. (P < 0.05).

The compaction technique and sealer showed interaction thus influencing the bond strength.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gutmann JL. Clinical, radiographic, and histologic perspectives on success and failure in endodontics. Dent Clin North Am. 1992;36:379–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sjögren U, Hägglund B, Sundqvist G, Wing K. Factors affecting the long-term results of endodontic treatment. J Endod. 1990;16:498–504. doi: 10.1016/S0099-2399(07)80180-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allen DE. Hermetic sealing of root canals, value in successful endodontics. J Dent Radiogr Photogr. 1964;37:85–90. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grossman LI. Physical properties of root canal cements. J Endod. 1976;2:166–75. doi: 10.1016/S0099-2399(76)80059-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Caicedo R, von Fraunhofer JA. The properties of endodontic sealer cements. J Endod. 1988;14:527–34. doi: 10.1016/S0099-2399(88)80084-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tay FR, Pashley DH. Monoblocks in root canals: A hypothetical or tangible goal. J Endod. 2007;33:391–8. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2006.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee KW, Williams MC, Camps JJ, Pashley DH. Adhesion of endodontic sealers to dentin and gutta-percha. J Endod. 2002;28:684–8. doi: 10.1097/00004770-200210000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wennberg A, Orstavik D. Adhesion of root canal sealers to bovine dentine and gutta-percha. Int Endod J. 1990;23:13–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.1990.tb00797.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tagger M, Tagger E, Tjan AH, Bakland LK. Measurement of adhesion of endodontic sealers to dentin. J Endod. 2002;28:351–4. doi: 10.1097/00004770-200205000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang W, Li Z, Peng B. Ex vivo cytotoxicity of a new calcium silicate-based canal filling material. Int Endod J. 2010;43:769–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2010.01733.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Candeiro GT, Correia FC, Duarte MA, Ribeiro-Siqueira DC, Gavini G. Evaluation of radiopacity, pH, release of calcium ions, and flow of a bioceramic root canal sealer. J Endod. 2012;38:842–5. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2012.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang W, Li Z, Peng B. Assessment of a new root canal sealer's apical sealing ability. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2009;107:e79–82. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2009.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ersahan S, Aydin C. Dislocation resistance of iRoot SP, a calcium silicate–based sealer, from radicular dentine. J Endod. 2010;36:2000–2. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2010.08.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Skidmore LJ, Berzins DW, Bahcall JK. An in vitro comparison of the intraradicular dentin bond strength of Resilon and gutta-percha. J Endod. 2006;32:963–6. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2006.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ørstavik D, Eriksen HM, Beyer-Olsen EM. Adhesive properties and leakage of root canal sealers in vitro. Int Endod J. 1983;16:59–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.1983.tb01297.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ungor M, Onay EO, Orucoglu H. Push-out bond strengths: The Epiphany — Resilon endodontic obturation system compared with different pairings of Epiphany, Resilon, AH Plus and gutta-percha. Int Endod J. 2006;39:643–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2006.01132.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roydhouse RH. Punch-shear test for dental purposes. J Dent Res. 1970;49:131–6. doi: 10.1177/00220345700490010501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Van Meerbeek B, De Munck J, Yoshida Y, Inoue S, Vargas M, Vijay P, et al. Buonocore memorial lecture. Adhesion to enamel and dentin: Current status and future challenges. Oper Dent. 2003;28:215–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Frankenberger R, Sindel J, Krämer N, Petschelt A. Dentin bond strength and marginal adaptation: Direct composite resins vs ceramic inlays. Oper Dent. 1999;24:147–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carneiro SM, Sousa-Neto MD, Rached FA, Jr, Miranda CE, Silva SR, Silva-Sousa YT. Push-out strength of root fillings with or without thermomechanical compaction. Int Endod J. 2012;45:821–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2012.02039.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sagsen B, Ustün Y, Demirbuga S, Pala K. Push-out bond strength of two new calcium silicate-based endodontic sealers to root canal dentine. Int Endod J. 2011;44:1088–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2011.01925.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ghoneim AG, Lutfy RA, Sabet NE, Fayyad DM. Resistance to fracture of roots obturated with novel canal-filling systems. J Endod. 2011;37:1590–2. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2011.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ureyen Kaya B, Keçeci AD, Orhan H, Belli S. Micropush-out bond strengths of gutta-percha versus thermoplastic synthetic polymer-based systems - An ex vivo study. Int Endod J. 2008;41:211–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2007.01342.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.De-Deus G1, Di Giorgi K, Fidel S, Fidel RA, Paciornik S. Push-out bond strength of resilon/epiphany and resilon/epiphany self-etch to root dentin. J Endod. 2009;35:1048–50. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2009.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]