Abstract

Aim/Objective:

The aim of this study is to compare the antimicrobial efficacy of QMix™ 2 in 1, sodium hypochlorite (NaOCl), and chlorhexidine (CHX) against Enterococcus faecalis and Candida albicans.

Materials and Methods:

Eighty freshly extracted, single-rooted human mandibular premolar teeth were instrumented and autoclaved. Samples were divided into two groups of 40 teeth each based on the type of microorganism used. Group I was inoculated with E. faecalis and Group II with C. albicans and incubated for 3 days. Each group was subdivided into four subgroups based on the type of irrigant used. Group IA, IIA, 5.25% NaOCl; Group IB, IIB, 2% CHX; Group IC, IIC, QMix™ 2 in 1; and Group ID, IID, 0.9% saline (the control group). Ten microliters of the sample from each canal was taken and was placed on Brain Heart Infusion agar and Sabouraud dextrose agar. The plates were incubated at 37°C for 24 h and colony forming units (CFUs) that were grown were counted. Data was analyzed with analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by post-hoc Games-Howell test.

Results:

The greatest antimicrobial effects were observed in samples treated with QMix™ 2 in 1 (P < 0.001). No statistical significant difference was found between 5.25% NaOCl and 2% CHX (P > 0.001) against E. faecalis and C. albicans.

Conclusion:

QMix™ 2 in 1 demonstrated significant antimicrobial efficacy against E. faecalis and C. albicans.

Keywords: Candida albicans, chlorhexidine, Enterococcus faecalis, QMix™ 2 in 1, sodium hypochlorite

INTRODUCTION

One of the most important objectives of endodontic therapy is to completely eliminate intracanal microorganisms from the root canal system to create favorable environment for healing and to prevent reinfection in order to achieve long-term success.[1]

Endodontic infections are polymicrobial in nature with predominant anaerobic microorganisms. Bacteria and their metabolic products, enzymes, and toxins play a vital role in the initiation, propagation, and persistence of pulpal and periradicular pathosis.[2] Although several factors contribute to endodontic failures, the literature reported that persistent intraradicular or secondary infection is the major etiology for failed endodontic therapy. Studies have shown that microflora in failed root canal therapy are different from those found in untreated teeth.[3]

Enterococcus faecalis (E. faecalis) and Candida albicans (C. albicans) are considered to be the most resistant species in infected root canals and they are often associated with endodontic treatment failures.[4]

E. faecalis is a gram positive, facultative anaerobic cocci commonly found in persistent root canal infection and commonly recovered in over one-third of the canal of endodontically treated teeth with persisting periapical lesions.[5,6]

C. albicans, the most predominant and commonly isolated yeast in failed root canal treatment with periradicular pathosis. It may gain access to the root canal from the oral cavity as a result of poor asepsis during endodontic treatment procedures or because of coronal leakage. It is a dentinophilic aerobic microorganism able to survive in harsh ecologic environment of root canal.[7,8]

Due to complex anatomy of root canal system, an effective disinfection is achieved by augmenting mechanical preparation with antimicrobial irrigants. Irrigants help in removal of debris and microorganisms form the canal that cannot be reached by endodontic instruments.[9] An ideal root canal irrigant should have good antimicrobial efficacy, nontoxic to periapical tissues, capable of dissolving necrotic tissue, able to lubricate the canal, and help in smear layer removal.[10,11]

Sodium hypochlorite (NaOCl) has been widely used as root canal irrigant due to its potent antimicrobial activity and tissue dissolving ability.[12] But it has several undesirable characteristics such as tissue toxicity, risk of subcutaneous emphysema, allergic potential, and disagreeable smell and taste.[13]

Chlorhexidine (CHX) digluconate has been suggested as root canal irrigant because of its good antimicrobial efficacy and substantivity. It seems to act by adsorbing onto the cell wall of microorganisms resulting in leakage of intracellular components. At low concentration, it has bacteriostatic effect. At higher concentration, has bactericidal effect due to precipitation and coagulation of intracellular constituents.[14,15]

QMix™ 2 in 1, an experimental irrigating solution, contains a mixture of a bisbiguanide antimicrobial agent, a polyamino carboxylic acid calcium chelating agent; saline; and a surfactant. It was evaluated as an effective irrigant similar to 17% ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) in removing canal wall smear layer after the use of 5.25% NaOCl as the initial rinse.[16] QMix had stronger antibacterial effects against young and old E. faecalisbiofilm in dentin[17] and had stronger antibacterial effect against E. faecalis present in deep dentin.[18] Studies are needed to evaluate the antimicrobial efficacy of QMix™ 2 in 1 in comparison with NaOCl and CHX against E. faecalis and C. albicans.

Thus, the aim of the present study is to compare the antimicrobial efficacy of QMix™ 2 in 1 with 5.25% NaOCl and 2% CHX digluconate against E. faecalis and C. albicans.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Eighty sound healthy human mandibular premolar teeth extracted for orthodontic treatment were taken. Teeth were cleansed using ultrasonic scalers to render them free from calculus and tissue tags, following which they were stored in physiological saline until use.

The teeth were decoronated at the cementoenamel junction using diamond disc (Isomet 2000; Buehler Ltd, Lake Bluff, IL) and the root lengths was standardized to approximately 14 mm. Pulp was extirpated and working length was established 1 mm short of apex where the file exited the apical foramen. Gates Glidden drills #3 (Mani Inc, Tachigi-ken, Japan) were used to prepare the root canal orifices (3 mm). Apical preparation was done using K-file (Dentsply Maillefer, Ballaigues, Switzerland) up to the ISO size #40. Canals were irrigated copiously with physiologic saline (0.9 w/v NaCl) after each instrument. Each canal was then rinsed with 1mL of 17% EDTA (Prime Dental Product) for 1 min followed by 3 mL of 5.25% NaOCl (Prime Dental Product, Mumbai, India) to facilitate the removal of smear layer. The roots were coated with nail varnish and apical foramen sealed with type II glass ionomer cement (GIC; GC Fuji, Tokyo, Japan).

The roots were sterilized in an autoclave for 15 min at 121°C and 15lb of pressure to ensure complete sterilization within the canal space. Efficacy of sterilization was tested by sampling the root canal with paper points. The paper points were placed into a test tube containing 1 ml reduced transport fluid, vortexed for 10 s, placed onto Brain Heart Infusion (BHI) agar (HiMedia Laboratories, Mumbai, India) and Sabouraud dextrose agar (Himedia Laboratories, Mumbai, India), incubated at 37°C for 48 h, and examined for growth. A suspension of E. faecalis (ATCC 29212) and C. albicans (Courtesy IBMS Institute, Chennai, India) were adjusted to 0.5 turbidity on the McFarland scale (1.5 × 108 bacteria/mL). E. faecalis suspension of 10 μL was injected into Group I samples containing 40 teeth and 10 μL suspension of C. albicans into Group II samples containing 40 teeth using a micropipette in a Class II vertical laminar airflow cabinet to prevent any airborne contamination. Then inoculated specimens with E. faecalis were placed in vials filled with BHI agar and inoculated specimens with C. albicans were placed in vials filled with Sabouraud dextrose agar, then inoculum was added every day and incubated aerobically at 37°C for 3 days. E. faecalis has ability to form biofilm on root canal walls. After 3 days, aliquots were taken from each tooth using a syringe and plated on BHI agar to verify the growth of E. faecalis and Sabouraud dextrose agar to verify the growth of C. albicans.

At the end of 3 days, teeth were removed from the vials and excess fluid in canal was removed with sterile paper points. The specimens from each group were divided into four subgroups (A, B, C, and D) of 10 teeth each depending on the experimental irrigating solution used. Test solutions used were: Subgroup IA and IIA: 3 mL of 5.25% NaOCl (Prime Dental Product, Mumbai, India), subgroup IB and IIB: 3 mL of 2% CHX (Dentochlor, Ammdent, PB, India), subgroup IC and IIC: 3 mL of QMix™ 2 in 1 (Dentsply Tulsa Dental Specialities, Tulsa, OK), subgroup ID and IID: 3 mL of 0.9% saline (positive control). Irrigation was accomplished using 30 gauge ProRinse needle (Dentsply) placed 1-2 mm short of the working length. The time of contact of each irrigant was 1 min and a final flush was done with 5mL of distilled water to terminate the action of irrigant.

A small amount of saline solution was introduced into the canal, and an endodontic hand file was used in a filing motion to a level 1 mm short of the root apex. Sterile 30 gauge needle was used to collect 0.01mL (10 μL) of the sample from the canal. Using a bacterial inoculation loop; the bacterial suspension was placed on Sabouraud dextrose agar and BHI agar. The plates were incubated at 37°C for 24 h and then number of colony forming units (CFUs) was counted.

Log transformation of absolute bacterial CFU was performed. Mean Log CFUs were compared among the groups using analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by post-hoc Games-Howell test.

RESULTS

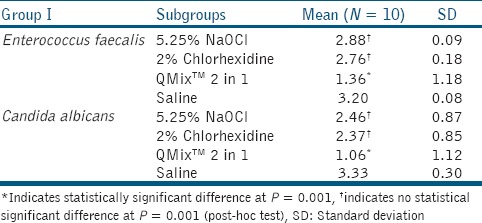

Results were analyzed with the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS)/Predictive Analytics Software (PASW) version 18 software. Table 1 shows the mean CFUs of E. faecalis and C. albicans. QMix™ 2 in 1 was the most effective and statistically significant when compared with 5.25% NaOCl and 2% CHX (P < 0.001). There is no statistical significant difference between 5.25% NaOCl and 2% CHX (P > 0.001).

Table 1.

Comparison of CFUs among the study groups

DISCUSSION

The main goal of chemomechanical preparation of infected root canals is to completely eliminate intracanal bacteria and prevention of recontamination after treatment.[1] This laboratory study was aimed to evaluate the antimicrobial efficacy of QMix™ 2 in 1, NaOCl, and CHX against E. faecalis and C. albicans. The in vitro model developed by Orstavik and Haapasalo has been used to assess antimicrobial efficacy of irrigants.[19]

E. faecalis and C. albicans are frequently isolated in root canals with pulpal infection and in secondary/persistent endodontic infections.[20]

In the present study QMix™ 2 in 1 has shown good antimicrobial efficacy and statistically superior to all other irrigants (P < 0.01). The reason could be effective functioning of individual constituents of it. Surface active agent lowers the surface tension of solution and increases their wett ability and enables better penetration of an irrigant in the root canal. The potential benefit of bisbiguanide in this mixture is that it prevents the microbial colonization on dentin surface. Calcium chelating agent can cause cell wall damage in gram negative bacteria by chelating and removing divalent cations (Mg+2 and Ca+2) from bacterial cell membrane and increasing its permeability.[21] Wang et al., concluded that QMix and 6% NaOCl had stronger antibacterial effects against young and old E. faecalis biofilm in dentin than 2% NaOCl and 2% CHX.[17] QMix and 6% NaOCl had stronger antibacterial effect against E. faecalis which resides deep in dentin than 1% and 2% NaOCl and 2% CHX.[18]

QMix™ 2 in 1 showed statistically superior antimicrobial efficacy against C. albicans. C. albicans was more resistant to irrigating solutions when the smear layer was present.[7] EDTA present in QMix™ 2 in 1 effectively removes the smear layer and CHX prevents the colonization of fungi on dentinal walls. There have been very few published studies examining the effect of antimicrobial agents on fungi. Those articles that have been published are difficult to compare because of variations in methodology and the agents tested.

NaOCl has effectively killed E. faecalis and C. albicans. But there was statistically significant difference present between QMix™ 2 in 1 and NaOCl (P < 0.001). NaOCl exerts its antibacterial effect by inducing the irreversible oxidation of sulfhydryl groups of essential bacterial enzymes, resulting in disulfide linkages, with consequent disruption of the metabolic function of bacterial cells.[10] Many in vitro and in vivo studies have proved NaOCl has good antimicrobial efficacy against E. faecalis.[22,23,24] Fidalgo et al., evaluated the antimicrobial activity of NaOCl, citric acid, and EDTA against E. faecalis, C. albicans, and Staphylococcus aureus and concluded that 2.5% and 5.25% NaOCl are microbiocides against S. aureus, while 0.5% and 1% NaOCl are only microbiostatic against the tested E. faecalis and C. albicans.[22]

CHX is a broad spectrum antimicrobial agent with substantivity property. The positively charged ions released by CHX can adsorb into dentin and prevent microbial colonization.[25] CHX has shown good antimicrobial efficacy against E. faecalis and C. albicans, but it is inferior to QMix™ 2 in 1 in this study (P < 0.001). Pavlovic and Zivkovic concluded that 2% CHX solution was effective against S. aureus, Streptococcus mutans, E. faecalis, Escherichia coli, and C. albicans.[26]

There was no statistical significant difference between CHX and NaOCl (P > 0.01). Arslan et al., concluded that propolis, BioPure MTAD, 5% NaOCl, and 2% CHX showed good antimicrobial activity against E. faecalis and C. albicans.[27]

The effectiveness of NaOCl and CHX on C. albicans is well documented in literature.[25,28,29] Ruff et al., investigated the efficacy of 6% NaOCl, 2% CHX, 17% EDTA, and BioPure MTAD against C. albicans and concluded that 2% CHX and 6% NaOCl were equally effective and statistically superior to 17% EDTA and BioPure MTAD.[29]

Saline has also shown considerable reduction in the CFU counts of E. faecalis and C. albicans. The mechanical shaping and cleaning of the canals and irrigation with saline served to flush out the debris from the canals. This accounted for a reduction in the microbial counts. Kuruvilla and Kamath reported a significant reduction in microbial counts with usage of saline in canals without mechanical preparation.[30]

CONCLUSION

Within the limitations of this study, QMix™ 2 in 1 demonstrated significant antimicrobial efficacy against E. faecalis and C. albicans.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Brito PR, Souza LC, Machado de Oliveira JC, Alves FR, De-Deus G, Lopes HP, et al. Comparison of the effectiveness of three irrigation techniques in reducing intracanal Enterococcus faecalis populations: An in vitro study. J Endod. 2009;35:1422–7. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2009.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu H, Wei X, Ling J, Wang W, Huang X. Biofilm formation capability of Enterococcus faecalis cells in starvation phase and its susceptibility to sodium hypochlorite. J Endod. 2010;36:630–5. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2009.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hoelscher AA, Bahcall JK, Maki JS. In vitro evaluation of the antimicrobial effects of a root canal sealer-antibiotic combination against Enterococcus faecalis. J Endod. 2006;32:145–7. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2005.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tirali RE, Turan Y, Akal N, Karahan ZC. In vitro antimicrobial activity of several concentrations of NaOCl and Octenisept in elimination of endodontic pathogens. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2009;108:e117–20. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2009.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shon W, Lim S, Bae KS, Baek S, Lee W. The expression of alpha 4 integrins by human polymorphonuclear neutrophils in response to sonicated extracts of Enterococcus faecalis. J Endod. 2005;31:369–72. doi: 10.1097/01.don.0000145420.29539.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kayaoglu G, Erten H, Bodrumlu E, Ørstavik D. The resistance of collagen-associated, planktonic cells of Enterococcus faecalis to calcium hydroxide. J Endod. 2009;35:46–9. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2008.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chandra SS, Miglani R, Srinivasan MR, Indira R. Antifungal efficacy of 5.25% sodium hypochlorite, 2% chlorhexidine gluconate, and 17% EDTA with and without an antifungal agent. J Endod. 2010;36:675–8. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2010.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Valera MC, Silva KC, Maekawa LE, Carvalho CA, Koga-Ito CY, Camargo CH, et al. Antimicrobial activity of sodium hypochlorite associated with intracanal medication for Candida albicans and Enterococcus faecalis inoculated in root canals. J Appl Oral Sci. 2009;17:555–9. doi: 10.1590/S1678-77572009000600003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dametto FR, Ferraz CC, Gomes BP, Zaia AA, Teixeira FB, de Souza-Filho FJ. In vitro assessment of the immediate and prolonged antimicrobial action of chlorhexidine gel as an endodontic irrigant against Enterococcus faecalis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2005;99:768–72. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2004.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oliveira DP, Barbizam JV, Trope M, Teixeira FB. In vitro antibacterial efficacy of endodontic irrigants against Enterococcus faecalis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2007;103:702–6. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2006.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Retamozo B, Shabahang S, Johnson N, Aprecio RM, Torabinejad M. Minimum contact time and concentration of sodium hypochlorite required to eliminate Enterococcus faecalis. J Endod. 2010;36:520–3. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2009.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Siqueira JF, Jr, Paiva SS, Rocas IN. Reduction in the cultivable bacterial populations in infected root canals by a chlorhexidine-based antimicrobial protocol. J Endod. 2007;33:541–7. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2007.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Murray PE, Farber RM, Namerow KN, Kuttler S, Garcia-Godoy F. Evaluation of morinda citrifolia as an endodontic irrigant. J Endod. 2008;34:66–70. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2007.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang CS, Arnold RR, Trope M, Teixeira FB. Clinical efficiency of 2% chlorhexidine gel in reducing intracanal bacteria. J Endod. 2007;33:1283–9. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2007.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xu Y, Young MJ, Battaglino RA, Morse LR, Fontana CR, Pagonis TC, et al. Endodontic antimicrobial photodynamic therapy: Safety assessment in mammalian cell cultures. J Endod. 2009;35:1567–72. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2009.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dai L, Khechen K, Khan S, Gillen B, Loushine BA, Wimmer CE, et al. The effect of Qmix, an experimental antibacterial root canal irrigant, on removal of canal wall smears layer and debris. J Endod. 2011;37:80–4. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2010.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang Z, Shen Y, Haapasalo M. Effectiveness of endodontic disinfecting solutions against young and old Enterococcus faecalis biofilms in dentin canals. J Endod. 2012;38:1376–9. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2012.06.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ma J, Wang Z, Shen Y, Haapasalo M. A new non invasive model to study the effectiveness of dentin disinfection by using confocal laser scanning microscopy. J Endod. 2011;37:1380–5. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2011.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Orstavik D, Haapasalo M. Disinfection by endodontic irrigants and dressings of experimentally infected dentinal tubules. Endod Dent Traumatol. 1990;6:142–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-9657.1990.tb00409.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ercan E, Dalli M, Dülgergil CT. In vitro assessment of the effectiveness of chlorhexidine gel and calcium hydroxide paste with chlorhexidine against Enterococcus faecalis and Candida albicans. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2006;102:e27–31. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2006.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stojicic S, Shen Y, Qian W, Johnson B, Haapasalo M. Antibacterial and smear layer removal ability of a novel irrigant, Qmix. Int Endod J. 2012;45:363–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2011.01985.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fidalgo TK, Barcelos R, Portela MB, Soares RM, Gleiser R, Silva-Filho FC. Inhibitory activity of root canal irrigants against Candida albicans, Enterococcus faecalis and Staphylococcus aureus. Braz Oral Res. 2010;24:406–12. doi: 10.1590/s1806-83242010000400006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Berber VB, Gomes BP, Sena NT, Vianna ME, Ferraz CC, Zaia AA, et al. Efficacy of various concentrations of NaOCl and instrumentation techniques in reducing Enterococcus faecalis within root canals and dentinal tubules. Int Endod J. 2006;39:10–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2005.01038.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sassone LM, Fidel RA, Murad CF, Fidel SR, Hirata R., Jr Antimicrobial activity of sodium hypochlorite and chlorhexidine by two different tests. Aust Endod J. 2008;34:19–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-4477.2007.00071.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mohammadi Z, Abbott PV. The properties and applications of chlorhexidine in endodontics. Int Endod J. 2009;42:288–302. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2008.01540.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pavlovic V, Zivkovic S. Chlorhexidine as a root canal irrigant — Antimicrobial and scanning electron microscopic evaluation. Srp Arh Celok Lek. 2010;138:557–63. doi: 10.2298/sarh1010557p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arslan S, Ozbilge H, Kaya EG, Er O. In vitro antimicrobial activity of propolis, BioPure MTAD, sodium hypochlorite, and chlorhexidine on Enterococcus faecalis and Candida albicans. Saudi Med J. 2011;32:479–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sen BH, Safavi KE, Spangberg LS. Antifungal effects of sodium hypochlorite and chlorhexidine in root canals. J Endod. 1999;25:235–8. doi: 10.1016/S0099-2399(99)80149-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ruff ML, McClanahan SB, Babel BS. In vitro antifungal efficacy of four irrigants as a final rinse. J Endod. 2006;32:331–3. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2005.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kuruvilla JR, Kamathmp MP. Antimicrobial activity of 2.5% sodium hypochlorite and 0.2% chlorhexidine gluconate separately and combined, as endodontic irrigants. J Endod. 1998;24:472–6. doi: 10.1016/S0099-2399(98)80049-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]