Abstract

Aim:

To compare the fracture resistance and modes of failures of three different aesthetic MOD onlays on endodontically treated premolars.

Materials and Methods:

Forty sound maxillary premolars were selected of which 10 untreated teeth were taken as control (Group I). The other thirty premolars were subjected to standardized MOD onlay preparations and root canal treatments and divided into 3 equal groups. Onlays were prepared in Group II- Indirect composite, Group III- Lithium Disilicate ceramic and Group IV- Full Zirconia. All onlays were cemented using Multilink Automix. All the 40 samples were subjected to fracture resistance testing on Universal testing machine. Also fractured specimens were observed under stereo-microscope for modes of failure.

Results:

Group IV presented the highest fracture resistance. Groups II and III presented no significant difference in fracture resistance from each other (P > 0.05). Group II and Group III showed significantly lower fracture resistance values than Group I. Coming to modes of failure, only Group IV had showed no cracks in any of the restorations.

Conclusion:

Full Zirconia MOD onlays increased the fracture resistance of endodontically treated premolars to a significantly higher level than the sound teeth.

Keywords: CAD/CAM onlays, Zirconia onlay, Lithium disilicate onlay, Indirect composite onlay

INTRODUCTION

Traditional principles of fixed prosthodontics recommend full coverage of endodontically treated tooth.[1] Indirect aesthetic materials have become very popular in making of inlays, onlays, and crowns. Lithium disilicate is one such material which has wonderful translucency and shade variety for the manufacture of inlays, onlays, and single crowns.[2] Indirect composite is another material which is proven to have improved fracture toughness because of post-cure treatment reinforcement.[3] Full-contour zirconia has become the most preferred material for anterior and posterior indirect restorations because of their high flexural strength, excellent biocompatibility, and good esthetics.[4]

Limited data is available regarding the selection of the appropriate tooth-colored restorative material and its influence on the fracture resistance of cusp-replacing restorations in endodontically treated posterior teeth. The present study assessed the fracture resistance and failure patterns of endodontically treated maxillary premolars restored with three all-ceramic CAD-CAM (computer aided design-computer aided manufacturing) onlay materials which are lithium disilicate, indirect composite, and full zirconia.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Forty sound human maxillary premolars atraumatically extracted for orthodontic reasons were selected and were stored in 0.5% chloramine solution (Oxford Lab Chem, India).[5] Teeth showing cracks under × 10 magnification were excluded. The roots were embedded in acrylic resin parallel to the long axis of teeth upto 2 mm below the cemento-enamel junction (CEJ). No simulation of periodontal ligament was performed.[6] Ten teeth were randomly selected for the control group (Group I) in which neither cavity preparation nor root canal treatment was performed. In the remaining 30 teeth, standardized mesio occluso distal (MOD) onlay cavities were prepared using FG 271 and FG 169L carbide burs (SS White, Lake wood, USA). Occlusal cavity width was kept at half the intercuspal distance, pulpal depth at 4 mm from the buccal cusp tip, and 6° taper on each wall. Gingival seat in the proximal boxes were placed 1 mm above the CEJ and width of the seat in mesio-distal direction was 1.5 mm. The buccal and palatal cusps were reduced occlusally by 2 mm from cusp tips and a 1.5 mm width collar was prepared for both cusps. Occlusal and proximal view of tooth preparation.

Root canal treatments were performed in these 30 teeth. Access openings were done with FG round diamond point ISO 001-009 (Dia burs, Mani, Tochigi, Japan). The coronal and middle thirds of the root canals were enlarged using sizes 1-3 Gates Glidden drills (Mani Tochigi, Japan). Subsequently the instrumentation of the root canals was done by step back technique using hand K files till clean shavings of dentin was achieved. Irrigation was performed using 1 ml of 2.5% NaOCl (Prime Dental Products, India) after every change of file size and after cleaning and shaping 3 ml of 17% ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA; Prevest Denpro, Jammu and Kashmir, India) was irrigated for 1 minute to remove smear layer.[7] The canals were obturated with Gutta-percha (Densply Maillefer, Ballaigues, Switzerland) and Grossman's sealer (Pharma Dent, Montevideo, Uruguay) by lateral condensation technique. Subsequently, the pulp chambers were temporarily filled with Cavit (3M ESPE, Germany) and stored for 24 h at 37°C in 100% humidity. Gutta-percha was removed upto the orifice of the canals and a zinc phosphate base of 1 mm was placed over the gutta-percha, and the remaining access cavity space was restored with dual cure flowable composite (Rebilda DC dual cure flowable composite, Voco, Germany) till the pulpal floor.

Onlays were fabricated in all the three groups. In Group II- indirect composite (Paradigm MZ 100,3M ESPE, St Paul, MN) and Group III- lithium disilicate glass-ceramic (IPS e. max CAD, Ivoclar Vivadent, Schaan, Liechtenstein) were fabricated using CAD/CAM (CEREC; Sirona, Bensheim, Germany) with the CEREC 3D system using the software package provided (Version 2.80R2402; Sirona). In Group IV- partially sintered zirconia onlays (Sagemax-NexxZr, Federal Way, USA) were fabricated using CAD/CAM using Delcam Dent CAD and Roland milling machine.

Cementation surfaces of Group III onlays were etched using 5% hydrofluoric acid for 60 s and rinsed under running water for 60 s and air dried for 30 s. A silane coupling agent was applied and allowed to dry for 3 min. Enamel and dentin margins were etched using 35% phosphoric acid for 15 s and rinsed with water for 30 s. All the onlays were cemented using Multilink Automix (Ivoclar Vivadent, Schaan, Lichtenstein).[8] Multilink primer A and B were mixed and applied to the cavity preparations according to the manufacturer's recommendation and the onlays were cemented and light-cured for 40 s on all restored surfaces.

The same protocol was followed for cementation of Groups II and IV except 5% hydrofluoric etching step was eliminated, instead was replaced by air borne particle abrasion with 27 μm aluminium oxide at 30 psi. The silane coupling agent (metal/zirconia primer) was applied for 180 s. After cementation of the restorations, specimens were stored in water for 21 days at 37°C. The fracture resistance of the buccal cusp[9] was tested on a universal testing machine (Instron, UK) with load applied on the center of the buccal cusp slope with a steel ball of diameter 3.5 mm at an angle of 30° to the long axis of the tooth with a crosshead speed of 0.5 mm/min.[5,10] The applied force in Newtons (N) at fracture was measured.

After mechanical failure, all specimens were observed under stereomicroscope (×2 magnification) to visualize the fracture lines in the restoration and the tooth.

Failure patterns were evaluated and classified into five categories:

Type I: No visible fracture in the restoration and tooth

Type II: No visible fracture in the restoration but fracture in the tooth

Type III: Fracture in the restoration only

Type IV: Fracture in the restoration and the tooth above CEJ

Type V: Fracture in the restoration and the tooth below CEJ

Statistical analysis

Resistance to fracture was submitted to parametric one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) test. Evaluation of failure patterns was performed using nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis test. Intergroup comparison was done to compare two groups using t-test. These were performed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS), version # 16.

RESULTS

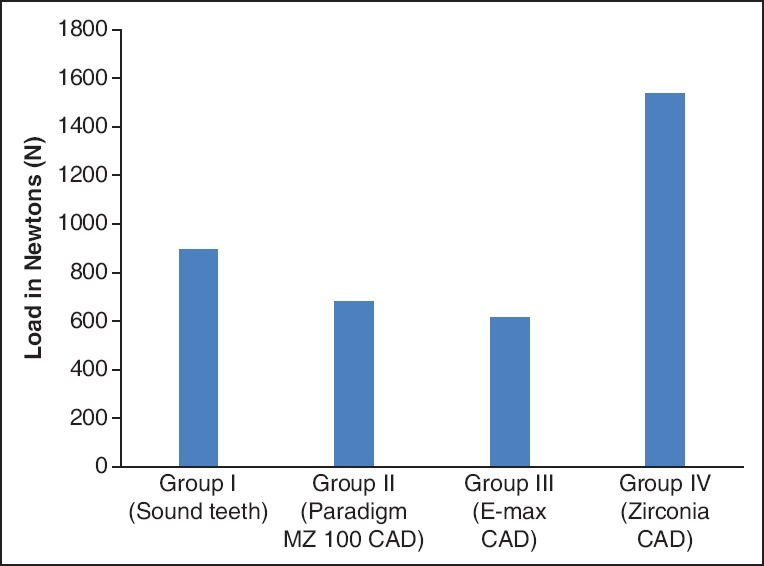

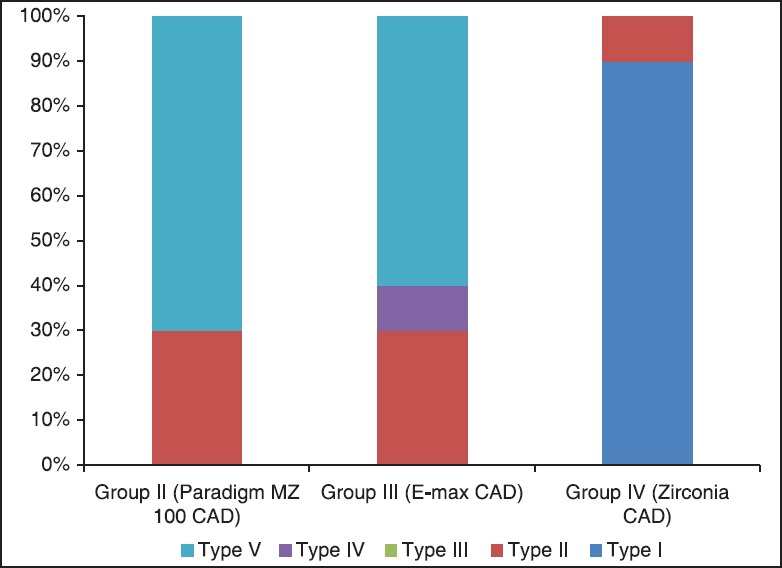

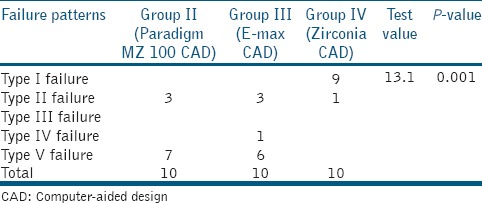

The mean fracture resistance and standard deviation of the experimental groups is shown in Figure 1. Group IV presented the highest fracture resistance. Groups II and III showed significantly lower values than the Group I. However, Groups II and III presented no significant difference from each other. Failure patterns are shown in Figure 2 and Table 1. Group II showed 30% type II fractures and 70% type V fractures. Group III demonstrated 30% type II fractures, 10% type IV, and 60% type V. Group IV demonstrated 90% type I and 10% type II fractures.

Figure 1.

Bar graph representing mean fracture resistance of four groups

Figure 2.

Bar graph representing comparison of failure patterns

Table 1.

Frequency table of failure patterns observed in all groups

DISCUSSION

Generally, endodontically treated teeth are considered to be more susceptible to fracture than the sound teeth, because of the internal tooth structure removal during endodontic treatment.

According to Reeh et al.,[11] endodontic treatment performed in intact teeth reduced fracture resistance by 5%, but when combined with an MOD cavity preparation, it is reduced to 69%.

Many authors preferred the onlay design to the inlay design as it would reinforce the cusps.[9,10,12] In the present study, the bucco lingual width of half the intercuspal distance was maintained to simulate the clinical situation where a wide bucco lingual access cavity is prepared. Earlier studies had maintained 1.5-2mm of occlusal cavity width for the inlays and onlays.[13] Buccal and palatal cusps were reduced by 2 mm occlusally and are in line with Bruke et al.,[14] who suggested that 2mm should be the minimal thickness of the indirect restoration that will provide adequate resistance to occlusal forces.

In the present study, the fracture resistance of Group I presented a mean fracture resistance of 980 N. Similar values were found in other studies,[15] which ranged between mean of 882 and 1,568N. This variance of results of the present study from the other studies may be due to difference in the type and design of the load application of the contact device, specimen preparation, test speed, and tooth storage method.

The mean fracture resistance in Group II was 681N. Fracture resistance of indirect composite CAD onlays has never been studied. Studies were mainly done on indirect composite crowns and veneers assessing the fatigue resistance.[16] In the present study, indirect composite CAD onlays could not reinforce the endodontically treated teeth to that of sound teeth.

The mean fracture resistance in Group III was 613N. Again there are no studies in the literature assessing fracture resistance of E-max press and E-max CAD onlays. However in the present study, E-max CAD onlays could not reinforce the endodontically treated teeth to that of sound teeth.

The mean fracture resistance in Group IV was 1,524.4N which is highest of all the groups. Fracture resistance of monolithic zirconia onlays has never been investigated. This high fracture resistance of Zirconia could be related to its phase transformation toughening phenomenon. Under stresses, when crack propagates within the zirconia mass, the tetragonal grains are transformed to monoclinic with a volume expansion of 3-5%. This expansion of the grains will ultimately lead to compressive stresses at the edge of the induced crack front and so extra energy is required for the crack to propagate.[17] In the present study, zirconia MOD onlays had reinforced the endodontically treated to a much higher value than that of the sound teeth.

In comparison between groups in the present study, the mean fracture resistance of Group I was significantly higher than Groups II and III. Although the fracture resistance of Groups II and III were lower than that of the Group I, their fracture resistance values were much higher than the normal masticatory forces which is between 222 and 447 N.[10] But that is not good enough to withstand the highest masticatory forces of 900N in bruxism and hard objects chewing.

While comparing Groups II and III, there is no significant difference statistically. This could be attributed to the increased thickness of E-max CAD of 2 mm in this study which could have withstood the testing loads compared to ultrathin models in other studies.[18]

Group IV onlays showed the highest fracture resistance compared to all other groups. Interestingly there is almost double the increase in the fracture resistance as compared to all the other groups. These findings were supported by Ma et al.,[19] who reported that flexural strength or fracture load of zirconia is 2.5 times greater than lithium disilicate glass ceramics suggesting that zirconia is much more suitable for free standing stress bearing application.

Coming to modes of failure; in contrast to many studies,[3,15] there was not much difference in the fracture modes of Groups II and III even though the stress distribution varies with the material properties and cavity design. The occlusal cavity depth of 4mm in the present study could have altered the stress distribution. This can be supported by Goel et al.,[20] where they suggested that deeper the prepared cavity, the greater the changes in the stress gradient in the dentin. The changes in the stress gradient could initiate fracture of the remaining cusps, possibly starting in the dentin immediately adjacent to the deepest portion of the cavity preparation.

In Group IV, none of the onlays fractured, but one sample fractured only in the root. The failure at a higher load could be due to the bond failure in the cement or fractures in the internal surface of the tooth, where more amount of stresses are usually concentrated.

CONCLUSION

Within the limitations of this in vitro study, it is interesting to note that full contour zirconia onlays had showed an excellent fracture resistance with no cracks in the restoration at very high loads, compared to lithium disilicate and indirect composite onlays. Therefore, full contoured zirconia could be chosen as an ideal esthetic posterior onlay material and could be a good alternative to unesthetic metal onlays.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Edelhoff D, Sorensen JA. Tooth structure removal associated with various preparation designs for anterior teeth. J Prosthet Dent. 2002;87:503–9. doi: 10.1067/mpr.2002.124094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chu SJ. Current clinical strategies with lithium disilicate restorations. Compend Contin Educ Dent. 2012;33:64–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Magne P, Knezevic A. Influence of overlay restorative materials and load cusps on the fatigue resistance of endodontically treated molars. Quintessence Int. 2009;40:729–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Al-Amleh B, Lyons K, Swain M. Clinical trials in zirconia: A systematic review. J Oral Rehabil. 2010;37:641–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2842.2010.02094.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bitter K, Meyer-Lueckel H, Fotiadis N, Blunck U, Neumann K, Kielbassa AM, et al. Influence of endodontic treatment, post insertion, and ceramic restoration on the fracture resistance of maxillary premolars. Int Endod J. 2010;43:469–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2010.01701.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Naumann M, Metzdorf G, Fokkinga W, Watzke R, Sterzenbach G, Bayne S, et al. Influence of test parameters on in vitro fracture resistance of post-endodonticrestorations: A structured review. J Oral Rehabil. 2009;36:299–312. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2842.2009.01940.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Basrani B, Haapasalo M. Update on endodontic irrigating solutions. Endod Topics. 2012;27:74–102. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Salameh Z, Sorrentino R, Ounsi HF, Goracci C, Tashkandi E, Tay FR, et al. Effect of different All-ceramic crown system on fracture resistance and failure pattern of endodontically treated maxillary premolars restored with and without glass fiber posts. J Endod. 2007;33:848–51. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2007.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cavel WT, Kelsey WP, Blankenau RJ. An in vivo study of cuspal fracture. J Prosthet Dent. 1985;53:3–41. doi: 10.1016/0022-3913(85)90061-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Habekost Lde V, Camacho GB, Pinto MB, Demarco FF. Fracture resistance of premolars restored with partial ceramic restorations and submitted to two different loading stresses. Oper Dent. 2006;31:204–11. doi: 10.2341/05-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reeh ES, Messer HH, Douglas WH. Reduction in tooth stiffness as a result of endodontic and restorative procedures. J Endod. 1989;15:512–6. doi: 10.1016/S0099-2399(89)80191-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yamanel K, Caglar A, Gülsahi K, Ozden UA. Effects of different ceramic and composite materials on stress distribution in inlay and onlay cavities: 3-D finite element analysis. Dent Mater J. 2009;28:661–70. doi: 10.4012/dmj.28.661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Santos MJ, Mondelli RF, Francischone CE, Lauris JR, de Lima NM. Clinical evaluation of ceramic inlays and onlays made with two systems: A one- year follow- up. J Adhes Dent. 2004;6:333–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burke FJ, Wilson NH, Watts DC. The effect of cuspal coverage on the fracture resistance of teeth restored with indirect composite resin restorations. Quintessence Int. 1993;24:875–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Soares PV, Santos-Filho PC, Martins LR, Soares CJ. Influence of restorative technique on biomechanical behaviour of endodontically treated maxillary premolars. Part I: Fracture resistance and failure mode. J Prosthet Dent. 2008;99:30–7. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3913(08)60006-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Attia A, Abdelaziz KM, Freitag S, Kern M. Fracture load on Composite resin and feldsphatic all-ceramic CAD/CAM crowns. J Prosthet Dent. 2006;95:117–23. doi: 10.1016/j.prosdent.2005.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vagkopoulou T, Koutayas SO, Koidis P, Strub JR. Zirconia in dentistry: Part 1. Discovering the nature of an upcoming bioceramic. Eur J Esthet Dent. 2009;4:130–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guess PC, Zavanelli RA, Silva NR, Bonfante EA, Coelho PG, Thompson VP. Monolithic CAD/CAM Lithium disilicate versus veneered Y-TZP crowns: Comparison of failure modes and reliability after fatigue. Int J Prosthodont. 2010;23:434–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ma L, Guess PC, Zhang Y. Load-bearing properties of minimal-invasive monolithic lithium disilicate and zirconia occlusal onlays: Finite element and theoretical analysis. Dent Mater. 2013;29:742–51. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2013.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goel VK, Khera SC, Gurusami S, Chen RC. Effect of cavity depth on stresses in a restored tooth. J Prosthet Dent. 1992;67:174–83. doi: 10.1016/0022-3913(92)90449-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]