Abstract

Increasing evidence suggests that selective neuronal loss in neurodegenerative diseases involves activation of cysteine aspartyl proteases (caspases), which initiate and execute apoptosis. In Alzheimer disease both extracellular amyloid deposits and intracellular amyloid β protein may activate caspases, leading to cleavage of nuclear and cytoskeletal proteins, including tau protein. Proteolysis of tau may be critical to neurofibrillary degeneration, which correlates with dementia.

Alzheimer disease (AD), the most common cause of dementia in the elderly, is associated with senile plaques and neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs), but the relationship between these two neuropathologic lesions has been difficult to discover. Senile plaques are heterogenous lesions composed of extracellular amyloid β protein (Aβ), dystrophic neuronal processes, and reactive glia (1), while NFTs are intracellular lesions composed of filamentous aggregates of the microtubule-associated protein tau (2). Genetic factors have implicated Aβ in the pathogenesis of AD since mutations are found in the Aβ precursor (APP) as well as in enzymes involved in the production of Aβ (reviewed in ref. 3). Moreover, genes implicated in AD by linkage studies encode proteins that degrade Aβ, such as insulin-degrading enzyme. The major genetic risk factor for late-onset AD, apolipoprotein E, promotes Aβ aggregation and colocalizes with Aβ in senile plaques.

The conundrum that has plagued research on AD is that clinicopathologic studies have not shown strong correlations between cognitive impairment and Aβ. In particular, the degree of cognitive impairment in AD is not as closely tied to the amount of amyloid deposited in the brain or the number of senile plaques as it is to the amount of abnormal tau protein in the brain and the density and distribution of NFTs (4, 5). This is not entirely surprising since NFTs are composed of proteins that are part of the neuronal cytoskeleton, which supports vital structural and dynamic neuronal functions. Amyloid, on the other hand, is a relatively innocuous extracellular deposit. It has been suggested that cytoskeletal disruption may act as the proximate cause of progressive synaptic and neuronal loss by interfering with axoplasmic and dendritic transport, which starves the cell of trophic support (6). This dysfunction and eventual death of neurons manifests clinically as cognitive impairment.

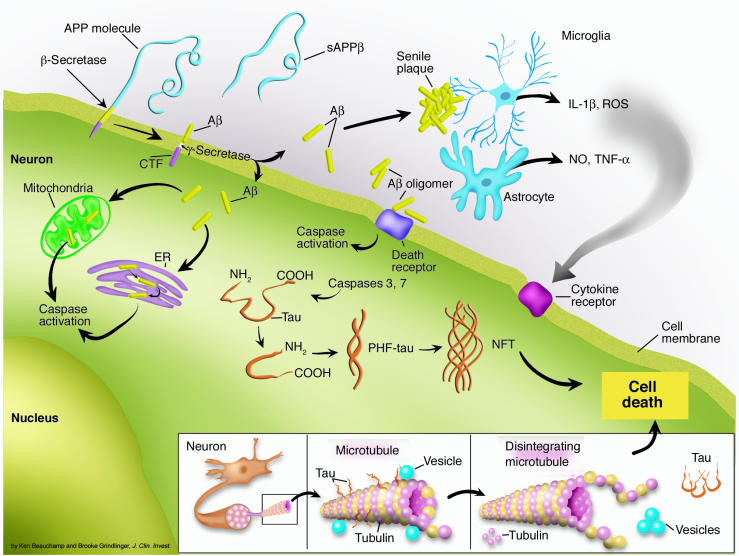

A major challenge of the amyloid cascade hypothesis for AD (Figure 1), which posits that amyloid formation leads to neuronal loss and dementia (7), is determining the link between Aβ, the protein most clearly linked to the cause of AD, and tau, the protein that is most clearly associated with clinical manifestations of AD. The studies by Rissman and coworkers in this issue of the JCI (8) suggest that apoptotic mechanisms may be the missing link.

Figure 1.

Proteolytic processes contribute to the amyloid cascade hypothesis. Aβ is generated from APP by concerted proteolysis by β-secretase, which generates carboxyl-terminal fragments (CTFs) of APP, and then by γ-secretase. The Aβ forms aggregates in the extracellular compartment as senile plaques through a process that depends on proteoglycans and apolipoproteins. The extracellular Aβ oligomers may activate caspases through activation of cell surface death receptors. Alternatively, intracellular Aβ may activate caspases through a process that involves ER stress or mitochondrial stress. One of the consequences of caspase activation is cleavage of tau, which favors conformational changes characteristic of paired helical filaments (PHF-tau). Progressive accumulation of tau leads to cytoskeletal disruption (inset), failure of axoplasmic and dendritic transport, and subsequent loss of trophic support that culminates in neuronal death. The extracellular amyloid deposits in senile plaques also trigger reactive glial changes and neuroinflammation that can also contribute to neuronal loss through production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), NO, and proinflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-1β. sAPPβ, secreted APPβ.

Apoptosis in AD

Apoptosis has been the focus of intense research in the last several decades as a means of controlling cell populations in normal development and inflammation through programmed cell death. Failure to control cell numbers through apoptosis is common in cancer, while excessive apoptosis is viewed to play a role in a number of neurologic disorders in addition to AD, including stroke and Parkinson disease (PD) (9).

Enthusiasm for apoptosis, however, as a mechanism for neuronal death in AD has been tempered in recent years. The initial evidence for apoptosis in AD came from cell culture experiments that were not always physiologically relevant, including exposure of cells to very high concentrations of Aβ or to Aβ peptides that do not exist in nature. Evidence for frank cellular apoptosis in AD is controversial, but there is growing recognition that apoptotic mechanisms may play a role in disease pathogenesis in the absence of overt apoptosis (10). Apoptosis is an attractive mechanism for neuronal death in neurodegenerative diseases for several reasons. Neuronal death in degenerative diseases is selective at the individual cell level and not associated with inflammation. In AD, neuronal loss is prominent in the cerebral cortex and the limbic lobe, while different neuronal populations are vulnerable in other neurodegenerative diseases. For example, in PD, brainstem monoaminergic neurons are affected. Cellular death via apoptosis is not associated with disruption of the cell membrane, and clearance of cellular debris is by facultative tissue phagocytes rather than professional macrophages of the reticuloendothelial system. Apoptosis also has a number of characteristic morphologic hallmarks, such as nuclear condensation and fragmentation, which have been very difficult to identify in AD brains.

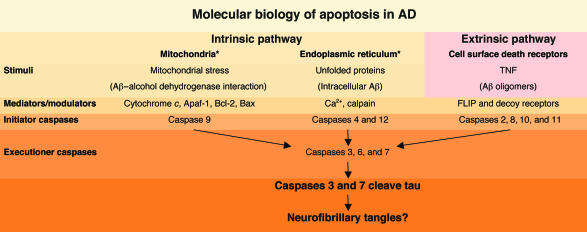

Another feature of apoptosis is intranucleosomal cleavage that produces DNA nicks that can be labeled by specific techniques, such as TUNEL. Initial reports of extensive neuronal TUNEL labeling in AD have been difficult to confirm, and much of the labeling appears to be related to damage to DNA that occurs as a postmortem artifact (11). Another approach to studying apoptosis is to examine enzymes that are involved in mediating programmed cell death. About a dozen such proteases have been identified; they share the property of being cysteine aspartyl proteases and are referred to as caspases. Caspases participate in apoptosis through initiation of intracellular cascades and in executing the final outcome, including proteolytic cleavage of cytoskeletal proteins and proteins of the nuclear scaffold. Both membrane (e.g., spectrin) and cytosolic (e.g., intermediate filament) cytoskeletal proteins are targets of caspase cleavage. Apoptosis is initiated through intracellular mechanisms that often involve alterations in mitochondria or endoplasmic reticulum and by signaling through cell membrane death receptors — the so-called intrinsic and extrinsic apoptotic pathways (12) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The interface of the two major molecules implicated in AD pathogenesis with molecular mechanisms of apoptosis. The two major pathways to cellular apoptosis are intrinsic and extrinsic. The extrinsic pathway involves signaling through cell surface death receptors, such as the TNF receptor, which are regulated by decoy receptors and Fas-associated death domain–like interleukin-1β–converting enzyme inhibitory proteins (FLIPs). Direct binding of Aβ or Aβ oligomers to death receptors remains to be shown, but the pattern of activation of downstream caspases (e.g., caspases 2 and 8) supports involvement of the extrinsic pathway in Aβ-mediated apoptotic processes. Alternatively, intracellular Aβ produced in the ER may lead to ER stress, or binding of Aβ to a mitochondrial alcohol dehydrogenase may lead to mitochondrial stress. Both entries into the intrinsic pathway may activate downstream apoptotic mechanisms. While details of the upstream mechanisms and mediators remain to be defined, activated executioner caspases 3 and 7 are capable of cleaving tau protein, which may favor formation of NFTs. Asterisk indicates possible sites of action of Aβ. Caspases 1 and 5 are involved in cytokine activation.

Activation of caspases has been reported in AD using antibodies that are specific to the activated forms of the enzymes, which themselves are activated by proteolysis (13). Increasingly, apoptotic mechanisms are viewed to play a role in neurodegeneration in the absence of overt apoptosis. The process may even act in discrete subcellular domains such as synaptic termini (14). If caspase activation plays a role in AD, it is important to learn how activation occurs, where in the neuron this process takes place, and whether or not it leads to neuronal death.

Activation of apoptosis in AD

While Aβ is a leading candidate for activation of apoptotic mechanisms in AD, recent evidence suggests that it is not the soluble form of Aβ that has toxic properties, but rather, higher order complexes of Aβ, including protofibrils and oligomers (also referred to as Aβ-derived diffusible ligands or ADDLs) (15). Some experimental studies suggest that Aβ can activate caspases through the extrinsic pathway, implicating binding of extracellular Aβ to cell receptors, while other studies suggest that the intrinsic pathway may be more relevant. Recent studies have drawn attention to the possible role of intracellular Aβ in neurodegeneration (16, 17). Accumulation of Aβ in endoplasmic reticulum or endosomes, where it may be synthesized, may activate apoptotic mechanisms through the unfolded protein response or endoplasmic reticulum stress. Alternatively, intracellular Aβ may bind to alcohol dehydrogenase within mitochondria and activate apoptosis through mitochondrial stress (18).

One of the consequences of caspase activation as discussed by Rissman and coworkers (8), as well as in the previous studies by Gamblin and others (19), is cleavage of tau protein. This is a significant finding because, in order for tau to form fibrils similar to those in NFTs, a number of conditions must be met (20). Fragments of tau, particularly those that contain the microtubule-binding domain, which is critical for self-interaction, more readily aggregate into fibrils than full-length tau. Other substances contribute to efficient fibril formation, particularly polyanions such as heparan sulfate proteoglycans, RNA, or arachidonic acid.

Tau proteolysis and neurofibrillary degeneration

The role of conformational changes in tau is also considered by some to be critical (21). Since tau is a natively unfolded molecule, its crystal structure is unknown and most current ideas about conformational changes in tau are based upon speculation rather than any hard structural data. Conformational changes in tau are inferred from antibodies that react with tau in solution-based assays or with pathological tau in immunohistochemistry, but not with denatured tau in Western blots. The epitopes of these putative conformational antibodies may be discontinuous, and this is the case for the epitope recognized by MC1 (21, 22), which is the monoclonal antibody used by Rissman and coworkers (8) to detect abnormal forms of tau protein. The recognition of this tau epitope by MC1 is dependent on specific amino- and carboxyl-terminal residues, which suggests that MC1 must recognize tau that is folded in such a way as to bring the two termini together (22). This conformation is felt to be specific for tau that forms NFTs (Figure 1). The conditions that favor this conformation are not known with certainty, but phosphorylation and proteolysis are postulated to be important. The evidence that phosphorylation is important is the fact that many of the antibodies that recognize NFTs recognize phosphoepitopes (23). Moreover, mapping of the phosphoepitopes in tau reveals phosphorylation sites that are not known to occur in normal tau. On the other hand, phosphorylation is not necessary for tau to form fibrils, at least in the test tube (20).

Proteolysis in AD and other neurodegenerative disorders

The first successful attempts to produce fibrils from tau used constructs with little more than the microtubule-binding domain, but more recent efforts show that full-length tau also forms fibrils in vitro. The microtubule-binding domain appears to be important for tau-tau interaction, and structural studies of the tau filaments isolated from Alzheimer brains reveal that the filaments have a fuzzy coat that can be cleared by protease treatment, leaving intact tau filaments. Analysis of the filaments with the fuzzy coat shows full-length tau, while the core contains the microtubule-binding domain of tau and a small number of flanking sequences (24).

If proteolytic events are crucial to the conformational changes that characterize early tau pathology, it is important to determine the proteases that catalyze this reaction. Tau undergoes proteolysis by at least two types of proteases — caspases and calpains (25, 26). Calpains are calcium-dependent proteases, and their activation by calcium fits well with pathogenetic scenarios that invoke increases in intracellular calcium as critical events in neurodegeneration. Caspases, on the other hand, are activated by conditions that favor apoptosis as discussed above. Interestingly, there is experimental evidence to suggest that both types of proteases can be activated during apoptosis (25). Moreover, proteolytic products generated by caspases and calpains can be difficult to differentiate from each other (27). While calpains are activated in nonapoptotic cell death, they may also play a role in the signal transduction that leads to apoptosis, particularly in the setting of endoplasmic reticulum stress.

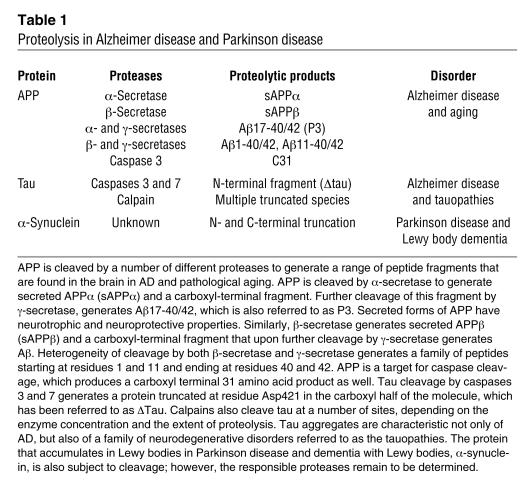

Understanding the relationship of proteolysis of tau protein to subsequent conformational changes and fibrillar aggregation is likely to shed light not only on AD, but also on other common neurodegenerative disorders, including PD. In AD and PD there is compelling evidence that proteolytic processing events contribute to aggregation of abnormal proteins derived from normal cellular proteins (Table 1). Both APP and tau are subject to proteolysis in AD, which produces proteins with abnormal conformations that aggregate into fibrillar intracellular and extracellular lesions. Similarly, the protein that accumulates in Lewy bodies within degenerating monoaminergic neurons in PD, α-synuclein, is also subject to proteolysis, since amino- and carboxyl-terminal truncated forms of α-synuclein are enriched in diseased brains (28). As with AD, it remains to be determined with certainty if the proteolytic events are necessary and early events that lead to neurodegeneration. Alternatively, they may be secondary processes in degenerating neurons subjected to activation of apoptotic mechanisms or flooding of intracellular compartments by calcium due to other underdetermined pathogenic processes.

Table 1.

Proteolysis in Alzheimer disease and Parkinson disease

Footnotes

See the related article beginning on page 121.

Nonstandard abbreviations used: Alzheimer disease (AD); amyloid β protein (Aβ); Aβ precursor (APP); neurofibrillary tangle (NFT); Parkinson disease (PD).

Conflict of interest: The author has declared that no conflict of interest exists.

References

- 1.Dickson DW. Pathogenesis of senile plaques. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 1997;56:321–339. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199704000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grundke-Iqbal I, et al. Microtubule-associated protein tau. A component of Alzheimer paired helical filaments. J. Biol. Chem. 1986;261:6084–6089. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tanzi RE, Bertram L. New frontiers in Alzheimer’s disease genetics. Neuron. 2001;32:181–184. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00476-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grober E, et al. Memory and mental status correlates of modified Braak staging. Neurobiol. Aging. 1999;20:573–579. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(99)00063-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bennett DA, Schneider JA, Wilson RS, Bienias JL, Arnold SE. Neurofibrillary tangles mediate the association of amyloid load with clinical Alzheimer disease and level of cognitive function. Arch. Neurol. 2004;61:378–384. doi: 10.1001/archneur.61.3.378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mandelkow EM, Stamer K, Vogel R, Thies E, Mandelkow E. Clogging of axons by tau, inhibition of axonal traffic and starvation of synapses. Neurobiol. Aging. 2003;24:1079–1085. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2003.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Golde TE. Alzheimer disease therapy: can the amyloid cascade be halted? J. Clin. Invest. 2003;111:11–18. doi:10.1172/JCI200317527. doi: 10.1172/JCI17527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rissman RA, et al. Caspase-cleavage of tau is an early event in Alzheimer disease tangle pathology. J. Clin. Invest. 2004;114:121–130. doi:10.1172/JCI200420640. doi: 10.1172/JCI20640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cotman CW, Anderson AJ. A potential role for apoptosis in neurodegeneration and Alzheimer’s disease. Mol. Neurobiol. 1995;10:19–45. doi: 10.1007/BF02740836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stadelmann C, Bruck W, Bancher C, Jellinger K, Lassmann H. Alzheimer disease: DNA fragmentation indicates increased neuronal vulnerability, but not apoptosis. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 1998;57:456–464. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199805000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Migheli A, Cavalla P, Marino S, Schiffer D. A study of apoptosis in normal and pathologic nervous tissue after in situ end-labeling of DNA strand breaks. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 1994;53:606–616. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199411000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schultz DR, Harrington WJ., Jr Apoptosis: programmed cell death at a molecular level. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;32:345–369. doi: 10.1053/sarh.2003.50005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Su JH, Zhao M, Anderson AJ, Srinivasan A, Cotman CW. Activated caspase-3 expression in Alzheimer’s and aged control brain: correlation with Alzheimer pathology. Brain Res. 2001;898:350–357. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(01)02018-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mattson MP, Keller JN, Begley JG. Evidence for synaptic apoptosis. Exp. Neurol. 1998;153:35–48. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1998.6863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gong Y, et al. Alzheimer’s disease-affected brain: presence of oligomeric A beta ligands (ADDLs) suggests a molecular basis for reversible memory loss. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2003;100:10417–10422. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1834302100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Glabe C. Intracellular mechanisms of amyloid accumulation and pathogenesis in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Mol. Neurosci. 2001;17:137–145. doi: 10.1385/JMN:17:2:137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oddo S, et al. Triple-transgenic model of Alzheimer’s disease with plaques and tangles: intracellular Abeta and synaptic dysfunction. Neuron. 2003;39:409–421. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00434-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lustbader JW, et al. ABAD directly links Abeta to mitochondrial toxicity in Alzheimer’s disease. Science. 2004;304:448–452. doi: 10.1126/science.1091230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gamblin TC, et al. Caspase cleavage of tau: linking amyloid and neurofibrillary tangles in Alzheimer’s disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2003;100:10032–10037. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1630428100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yen SH, Hutton M, DeTure M, Ko LW, Nacharaju P. Fibrillogenesis of tau: insights from tau missense mutations in FTDP-17. Brain Pathol. 1999;9:695–705. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.1999.tb00551.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weaver CL, Espinoza M, Kress Y, Davies P. Conformational change as one of the earliest alterations of tau in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging. 2000;21:719–727. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(00)00157-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jicha GA, Bowser R, Kazam IG, Davies P. Alz-50 and MC-1, a new monoclonal antibody raised to paired helical filaments, recognize conformational epitopes on recombinant tau. J. Neurosci. Res. 1997;48:128–132. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4547(19970415)48:2<128::aid-jnr5>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jicha GA, O’Donnell A, Weaver C, Angeletti R, Davies P. Hierarchical phosphorylation of recombinant tau by the paired-helical filament-associated protein kinase is dependent on cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase. J. Neurochem. 1999;72:214–224. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.0720214.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wischik CM, et al. Isolation of a fragment of tau derived from the core of the paired helical filament of Alzheimer disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1988;85:4506–4510. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.12.4506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Canu N, et al. Tau cleavage and dephosphorylation in cerebellar granule neurons undergoing apoptosis. J. Neurosci. 1998;18:7061–7074. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-18-07061.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johnson GV, Jope RS, Binder LI. Proteolysis of tau by calpain. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1989;163:1505–1511. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(89)91150-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang KK. Calpain and caspase: can you tell the difference? Trends Neurosci. 2000;23:20–26. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(99)01536-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee MK, et al. Human alpha-synuclein-harboring familial Parkinson’s disease-linked Ala-53 Ø Thr mutation causes neurodegenerative disease with alpha-synuclein aggregation in transgenic mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2002;99:8968–8973. doi: 10.1073/pnas.132197599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]