Abstract

PURPOSE

While patients often use the internet as a medium to search for and exchange health-related information, little is known about the extent to which patients use social media to discuss side effects related to medications. We aim to understand the frequency and content of side effects and associated adherence behaviors discussed by breast cancer patients related to using aromatase inhibitors (AIs), with particular emphasis on AI-related arthralgia.

METHODS

We performed a mixed methods study to examine content related to AI associated side effects posted by individuals on 12 message boards between 2002 and 2010. We quantitatively defined the frequency and association between side effects and AIs and identified common themes using content analysis. One thousand randomly selected messages related to arthralgia were coded by two independent raters.

RESULTS

Among 25,256 posts related to AIs, 4,589 (18.2%) mentioned at least one side effect. Top-cited side effects on message boards related to AIs were joint/musculoskeletal pain (N=5,093), hot flashes (1,498), osteoporosis (719), and weight gain (429). Among the authors posting messages who self-reported AI use, 12.8% mentioned discontinuing AIs, while another 28.1% mentioned switching AIs. Although patients often cited severe joint pain as the reason for discontinuing AIs, many also offered support and advice for coping with AI-associated arthralgia.

CONCLUSIONS

Online discussion of AI-related side effects was common and often related to drug switching and discontinuation. Physicians should be aware of these discussions and guide patients to effectively manage side effects of drugs and promote optimal adherence.

Keywords: adverse effects, adherence, breast neoplasm, aromatase inhibitor, health communication, online, musculoskeletal, joint pain

INTRODUCTION

The internet is an important facet of modern living with an estimated two billion users worldwide. Approximately 476 million (58.3%) Europeans and 272 million (78.3%) Americans use the internet regularly.1 According to the Pew Internet & American Life Project, 61% of American adults go online for health information.2 Additionally, individuals with chronic health conditions such as high blood pressure, diabetes, heart disease, and cancer utilize the internet for information on self-management.2,3

Breast cancer is the leading cause of cancer death among women.4 Because of early diagnosis and improved treatment, 2.5 million breast cancer survivors live in the U.S. and many are cared by primary care physicians.5,6 Previous research shows breast cancer survivors have used the internet to search for information on their diagnoses, treatment options, medications, and control of side effects.7–11 Over the years, the internet has become a social medium where users can communicate and exchange information with others through online message boards and support groups. These online communities provide breast cancer survivors with a space and anonymity to ask questions, gain more intimate knowledge about the disease, and voice fears and frustrations to an understanding audience.7,12

Despite these findings, no research has focused on examining how patients discuss side effects associated with medications and the potential impact on adherence behaviors. This is particularly important as research suggests that internet users play an active role in decision making regarding medical therapies,13,14 and that information a user obtains online may affect their behaviors and, ultimately, outcome.

We began our inquiry into the online discussion of drug side effects with aromatase inhibitors (AIs), the most commonly used medications among post-menopausal women with hormone receptor positive breast cancer. AIs have an estimated annual revenue of over $3.5 billion worldwide; they are considered standard adjuvant hormonal treatments shown to be effective in preventing hormone receptor positive breast cancer recurrence.15–17 Joint pain, or arthralgia, is a major symptom in breast cancer survivors receiving AIs.18 In clinical settings outside of therapeutic trials, nearly half of the patients on AIs attribute arthralgia to this class of medication.19–21 AI-associated arthralgia (AIAA) results not only in reduced function,22 but also in sub-optimal adherence and premature discontinuation.23 A recent large study found that nearly 50% of breast cancer survivors receiving adjuvant hormonal treatments, including AIs, did not complete the desired course of treatment.24 Those who stopped medications or had non-optimal adherence had increased breast cancer-related and overall mortality.25

We first sought to evaluate the volume and frequency of AI-associated side effects reported on internet message boards. We then focused on understanding the specific communication content related to AIAA since that is one of the most common side effects reported in the existing literature on AIs.26

Materials and Methods

Overall Design

We performed a mixed methods (i.e., quantitative and qualitative) study using breast cancer message boards. We first quantitatively defined the frequency and association between side effects and AIs in message boards using the methods reported in Benton et al.27 Informed by findings from this step, we randomly selected 1,000 messages for detailed coding containing AIs and arthralgia. To develop the codes, we performed content analyses among the first 60 posts, identified themes, and developed a coding scheme for communication about AI-associated arthralgia. This study was approved by the University of Pennsylvania Institutional Review Board.

Data Source

The corpus of text examined consisted of 1,235,400 posts collected from 12 different breast cancer message boards between February 2002 and May 2010. The majority of the posts (71%) came from breastcancer.org. This distribution of messages over sites, where a select few sites contain many messages and a long list of sites contain much fewer, is expected in the current online environment. The message boards were chosen using a search engine; we identified message boards with a large number of posts (N>100) that were structured to allow the data to be easily collected. Table 1 lists the twelve message boards used to generate the corpus and the number of messages and threads in each.

Table 1.

Message Boards Used to Generate Corpus

| URL | # Posts | # Threads | # Posts/Threads |

|---|---|---|---|

| http://community.breastcancer.org/ | 872728 | 26128 | 33.4 |

| http://apps.komen.org/forums/ | 201909 | 25469 | 7.9 |

| http://csn.cancer.org/forum/127 | 113521 | 11663 | 9.7 |

| http://bcsupport.org/ | 14215 | 3242 | 4.4 |

| http://www.healthboards.com/boards/forumdisplay.php?f=23 | 11270 | 2738 | 4.1 |

| http://www.cancercompass.com/message-board/cancers/breast-cancer/1,0,119,1.htm | 8543 | 1918 | 4.5 |

| http://boards.webmd.com/webx/topics/hd/Cancer/Breast-Cancer-Friend-to-Friend/ | 7974 | 1549 | 5.1 |

| http://www.dailystrength.org/c/Breast-Cancer/forum | 2255 | 521 | 4.3 |

| http://www.revolutionhealth.com/forums/cancer/breast-cancer | 1786 | 551 | 3.2 |

| http://ehealthforum.com/health/breast_cancer.html | 921 | 332 | 2.8 |

| http://www.oprah.com/community/community/health/cancer | 150 | 55 | 2.7 |

| http://boards.webmd.com/webx/topics/hd/Cancer/Breast- | |||

| Cancer-Living-with-Metastatic-Breast-Cancer/ | 128 | 47 | 2.7 |

Posts were collected with a custom-built web crawler that followed links within the message boards and downloaded pages that contained message posts. Information relevant to the posts (e.g. subject text, body text, username of author, date posted) was extracted from these pages, and saved in a standardized format. Personal identifiers were then removed from these messages using a de-identification system we designed specifically for message board text.28 This system removed e-mail addresses, phone numbers, user resource locators (URLs), social security numbers, usernames, and proper names from the posts. We replaced names with “hashed” identifiers that allowed us to track an individual’s posts throughout a thread without revealing the true identity of that individual. This de-identified corpus was then used for subsequent analyses.

Quantitative search on AI-side effects

Our first goal was to discover which symptoms breast cancer message board users mentioned the most frequently with respect to AIs. This was done by searching through the breast cancer message board corpus for all occurrences of terms that referred to an AI (“arimidex,” “aromasin,” “femara,” “anastrozole,” “exemestane,” and “letrozole”). All occurrences of symptom terms were also identified. The list of symptom terms was compiled by collecting all of the terms reported as reactions to or indications for all drugs (not limited to AIs) reported in the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s Adverse Event Reporting System database29 from the first quarter of 2004 to the second quarter of 2009 and then augmenting these with lay terms found in the Consumer Health Vocabulary (http://www.consumerhealthvocab.org), again not limited to terms associated with AIs. If an AI occurred within 20 tokens (i.e. strings of characters separated by punctuation or whitespace) of a symptom term, then this was treated as a co-occurrence. For each AI/symptom pair found, a 2x2 contingency table of their rate of co-occurrence was constructed and a Fisher’s exact test was used to determine the p-value for the null hypothesis that these two terms co-occurred independently. The null hypothesis was assumed to be that the AI/symptom term were distributed independently over the messages in our corpus. P(AI, Symptom) = P(AI)*P(Symptom). All pairs with the Simes-corrected p-value less than 0.05 were considered significant.

Analyses of AI-associated Arthralgia

Because arthralgia was identified as being the most commonly cited side effect in our step one, we referred back to posts containing these possible mentions of AIAA. We first randomly selected 1,000 posts that mentioned joint pain near an AI mention. Of these, we randomly selected 60 messages for qualitative content analysis to identify common themes. These themes were then discussed among study investigators to develop consensus. They included whether or not individuals attributed their joint pain to an AI, their switching / adherence behavior, strategies used to cope with AIAA, and information sought or given. We used these themes to develop an instrument to code the total 1,000 message posts. The qualitative data gathered during the analysis also helped to populate the coding instrument with subcategories for each theme. We established definitions and decision rules for each of the codes and two researchers (AC and AB) were trained to use the coding instrument based on these rules.

The overall inter-rater reliability ranged from 76.4% to 100.0% (mean of 96.0%, standard deviation of 4.8%) among the various codes. Records that differed were compared and reconciled between the two coders. If a decision could not be made, a third coder (JM) reviewed the data and made a final decision. We sampled at least 1,000 posts to calculate a point estimate of the prevalence of each study variable, with a total width set at 5 percentage points for the 95% confidence interval (CI), using the conservative assumption of a point estimate of 50% for each study variable.

RESULTS

MOST COMMONLY REPORTED SIDE EFFECTS

Among 1,235,400 posts, 25,256 (2.0%) mentioned one of the three specific AIs. Within those, 4,589 (18.2%, 95% CI 17.7–18.7%) mentioned at least one side effect close to that term in the text. Among the commonly cited side effects associated with AIs (see Table 2), musculoskeletal pain (e.g., joint, muscle, bone) was mentioned 5,093 times, at a frequency substantially greater than vasomotor symptoms (1,498 times, including hot flash and night sweats), followed by bone loss/osteoporosis (719 times), and weight gain (429 times).

Table 2.

Side Effects Associated with Aromatase Inhibitors

| Symptom | Count | P-value* |

|---|---|---|

| Pain (joint, bone, muscle) | 5093 | 0 |

| Vasomotor (hot flush/sweat) | 1498 | 0 |

| Osteoporosis (Bone loss) | 719 | 0 |

| Weight gain | 429 | 4.20E-126 |

| Hair loss | 317 | 1.47E-37 |

| Mental depression | 289 | 1.80E-34 |

| Sleeplessness | 208 | 4.88E-64 |

| Headache | 196 | 0.00056 |

| Thyroid issues | 122 | 1.77E-06 |

| Dizziness | 119 | 5.35E-10 |

| Back pain | 102 | 6.05E-13 |

P-value by Fisher’s exact test between presence of an aromatase inhibitor and a side effect

AROMATASE INHIBITOR ASSOCIATED ARTHRALGIA

In the 1,000 posts that we coded for AI associated arthralgia, 829 (82.9%, 95% CI 80.4%–85.2%) mentioned experiencing joint pain directly related to AIs, while others inferred joint pain was related to other causes or offered an opinion about AI associated arthralgia.

SWITCHING AND ADHERENCE BEHAVIORS

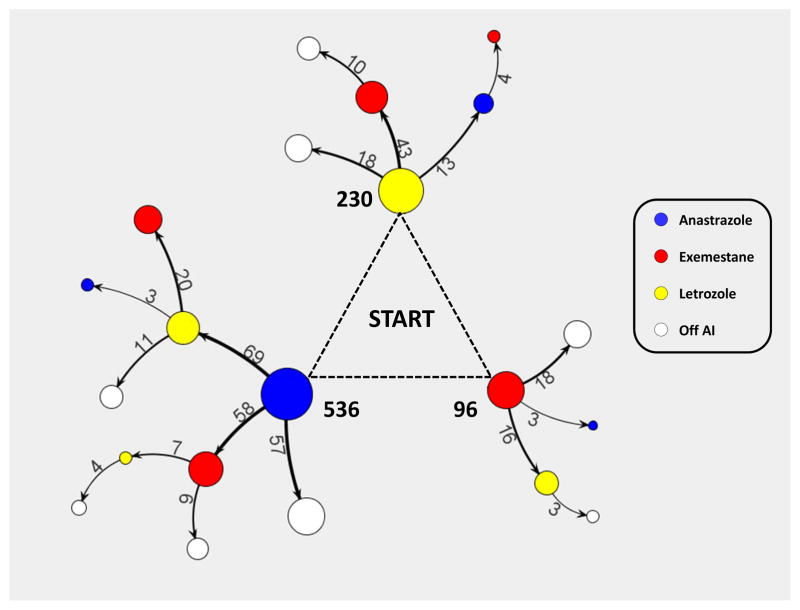

From the 862 out of the 1,000 posts in which we were confident that subjects stated their previous and current drug therapies, we generated a tree diagram by merging the paths that users took when mentioning having switched AIs (see Figure 1). Among patients who started AIs (N=862), 110 (12.8%, 95% CI 10.5%–15.0%) mentioned discontinuing AIs with no intention of starting a new one, 201 (23.3%, 20.5%–26.1%) switched once, and 41 (4.8%, 3.3%–6.2%) switched twice (i.e. used all three AIs). Among those no longer on AIs (N=110), 74 (67.3%, 58.5%–76.0%) quit after one AI, 30 (27.3%, 19.2–36.6%) quit after two, and 10 (9.1%, 4.4–16.1%) quit after trying all three AIs.

Figure 1. Self-reported Paths of AI Switching in Breast Cancer Message Board Users.

Node color refers to the particular drug they claimed to be on (Anastrozole: Blue, Exemestane: Red, Letrozole: Yellow, Not on Aromatase Inhibitor: White), and the thickness of the edge reflects the proportion of the original population that moved from that particular node to the next node. Only users whose transitions between drugs were explicitly stated and had mentioned being on at least one AI were used to generate this tree (n=917). Edges with less than three users switching between these nodes are not displayed. The numbers in bold refer to the number of users that mentioned beginning on that particular AI.

REASONS FOR STAYING ON OR STOPPING MEDICATIONS

If an author of a post indicated that she was taking an AI at the time of the post (N=742, 74.2%), we coded her reason for continuing. The most common reason given was manageability of joint pain 199 (26.8%, 95% CI 23.7–30.2%). Other post authors conveyed that the joint pain was a great inconvenience, but felt the benefits of the drug outweighed its adverse effects 77 (10.4%, 8.3–12.8%). These authors seemed appreciative that there was something for them to take to help reduce the risk of recurrence. Other authors expressed continuing with an AI because they feared that the consequences of not taking the drug would lead to a recurrence 61(8.2%, 6.3–10.4%). These individuals generally felt that they had to take the drug and did not have any other options (see Table 3 for sample quotes).

Table 3.

Decisions about Continuing or Stopping Aromatase Inhibitors*

| Reasons for continuing | |

|---|---|

| Joint pain manageable | I stuck it out and by last November I rounded a corner and the side effects became more manageable. I take some Advil every now and then, but any pain I have now is very tolerable. The joint pains are never completely gone, but they have settled into being tolerable at least. |

| Afraid not to take | I'm afraid to stop taking it. What should we all do, I feel I’ll never be who I was before breast cancer...I’m not ready to stop living. I hurt, ache, swell, pain, shuffle, have significant joint pain, have cognitive issues, and feel like I'm 80 when I'm mid-50's. But I'm also so afraid of the breast cancer that I shuffle alongside of everyone, like you do. |

| Benefit outweighs risk | Like someone said in one of the other posts, I can live with the joint pain as long as it's helping to keep the cancer from recurring. The way I look at it, at 53 years old, I was likely to get arthritis anyway, and any discomfort I may have as a result of treatment is well worth prolonging my life. I have no regrets at all. I do have some joint pain on arimidex but it's far preferable to a recurrence of course so I'm happy to continue taking it. |

| Reasons for stopping | |

| I cannot live this way with the pain. I can barely function at my job and I need to work. Last night at this site I found 13 other ladies with the same problem. I was so happy to read I wasn't the only one and that my intuition was right. It was the meds. Now my oncologist wants me to start aromasin. When I see her Wednesday I'm telling her no way. I took Arimidex for 10 months and recently stopped it. I was having unbearable joint pain and felt like I was 90. My joints feel so much better now. I had joint and bone pain with Arimidex and decided no more drugs even though I have one more year to go. I figured the small survival advantage was not worth all the side effects. I feel great...hope I made the right decision. I started taking aromasin in Nov of 2006. I stopped taking it because the side effects just weren't worth it. My theory is there isn't enough info about long term effects. Just my opinion. I'm too young to feel so bad! |

|

| Reluctance to start | As for the joint pain, I'm still suffering with joint pain since stopping Arimidex in August. Now my doctor wants me to try Tamoxifen and after reading the side effects I'm reluctant to take any meds at all. I am unsure about taking Arimidex after reading all the side effects. I already have joint pain as I have arthritis. |

| Advice | |

| If you don't do well on one, there are others you can try. I never thought a medicine could make you feel so bad. But for every one of me, there is someone else who has no trouble. It's good to know how different people react, so you know what to share with your doc. Try it for yourself, don't let others scare you off, everyone is different. Don’t give up, just allow some time for your body to adjust. It’s the most effective drug we postmenopausal folks can take. Give it some adjustment time, at least a month or more and see how the effects are then. But talk to your doctor just the same. |

|

These quotes have been slightly altered to protect the authors and to prevent them from being discovered online

Among posts indicating that authors had stopped taking the AIs (N=110), 100 (90.9%, 95% CI 84.0–95.6%) patients expressed experiencing frequent debilitating pain attributable to AIs and perceived that the side effect was much greater than the benefit of AI in recurrence prevention. Other reasons included different side effects, cost, and perceived ineffectiveness of the drug (numbers were too low to calculate reliable estimates). A few patients also indicated that reading other posts helped validate their concerns about side effects and affirmed their decisions to stop or start AIs (see Table 3 for sample quotes).

SEEKING AND GIVING ADVICE

Among the 1,000 posts, 179 (17.9%, 95% CI 15.6–20.4%) sought advice on how to deal with AIAA and 274 (27.8%, 24.7–30.3%) explicitly gave advice. Among those messages that provided advice (N=274), 85 (31%, 25.6–36.9%) provided advice on how to cope with AIAA, 97 (35.4%, 29.7–41.4%), provided general information about AIs, and 75 (27.4% 22.2–33.1%) urged others to seek advice from their own physicians. Twenty-six (9.5%, 6.3–13.6%) told others “the decisions are yours,” while 22 (8%, 5.1–11.9%) urged others to stay on AIs.

STRATEGIES TO COPE

Among the 1,000 posts, 281 (28.1%, 25.3–31.0%) mentioned some method for addressing their AI-related joint pain (see Table 4); 119 (42.3%, 36.5–48.4%) of these posts mentioned using pharmaceuticals, whether prescribed or over the counter. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs were reported most often followed by cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors, and acetaminophen. Several mentioned getting corticosteroid injections when their joint pain, carpal tunnel, or tendonitis became too severe; 125 (44.5%, 38.6–50.5%) posts mentioned using herbal or mineral supplements to reduce or prevent joint pain. Glucosamine and chondroitin were mentioned most often, followed by vitamin D, calcium, fish oil, and magnesium. The third most frequently reported strategy for dealing with joint pain was exercise (30.6%, 25.3–36.4%). Authors indicated that exercising sometimes helped to relieve some of their joint pain or prevented it from worsening. This included stretching or just keeping their bodies moving. However, some mentioned that joint pain sometimes made it difficult to exercise.

Table 4.

Strategies Used to Deal with Aromatase Inhibitor Associated Arthralgia

| Drug | 119* |

| Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (e.g. ibuprofen) | 61 |

| Cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors (e.g. celecoxib) | 32 |

| Acetaminophen | 14 |

| Corticosteroid injection | 12 |

| Anticonvulsant (e.g. gabapentin) | 11 |

| Opioid (e.g. oxycondone) | 8 |

| Other* | 19 |

| Supplement | 125* |

| Glucosamine/Chondroitin | 58 |

| Vitamin D | 42 |

| Calcium | 32 |

| Fish oil | 18 |

| Magnesium | 10 |

| Other | 33 |

| Exercise | 86 |

| See a specialist | 17 |

| Other | 52 |

Number of posts mentioned drug/supplement at least once. Some posts may have multiple therapies mentioned so the total did not add up

Other ways of addressing pain includes: acupuncture, surgery, splints, hot/cold, massage, magnetic bracelets, adjustments to diet, stress balls, change in dosage, and stretching.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we found that many individuals discussed the side effects of AIs on internet message boards related to breast cancer. For posts mentioning AIAA, many also claimed to have switched between or discontinued AIs completely. Individuals voiced concerns and struggles to balance risk and benefit, and offered practical advice and support to one another.

The observed relative frequency of key side effects reflected those reported from large clinical trials15–17 and epidemiologic studies.19,20,30 Previous research found patient-reported AIAA in clinical settings was much higher than clinician-assessed toxicities in clinical trials.19,20 Increasing effort is currently underway to incorporate patients’ voices into adverse events reporting.31 Our study demonstrated that the internet is another way for individuals to report side effects. Interestingly, pain-related concerns in this study outnumbered vasomotor symptoms, the second most common side effect category, by a factor of three, a much greater difference than expected from prior literature of clinical trials.15,16 The spontaneity and anonymous nature of internet message board provides individuals to voice concerns they feel the most pertinent. It is also likely that the side effects that resonate most among other individuals will generate the most conversation. Thus, the frequency data should not serve as prevalence of the side effect but as a measure of which symptoms may be the most salient to patients on a day-to-day basis. .

Our study also offers unique insights into AI adherence. Hershman et al. found that non-optimal adherence to hormonal treatment exceeded 50%.24 We found that individuals switch or stop AIs because of side effects. Women tried to appraise the level of their symptom severity and weigh the benefits of continuing AIs against current or expected side effects. Some continued AIs (10.4%) despite significant arthralgia because they viewed the benefit as outweighing the harm. For others (8.4%), fear of recurrence drove them to feel they had no other options. The psychological aspect of decision making should be further explored to develop and apply theory-based interventions32 to promote optimal adherence in the context of effective symptom management.

We also found that individuals exchanged information and offered practical advice and social support. Through message boards, some survivors expressed recognition that their suffering was shared among others. This reassurance can validate patients’ concerns and encourage them to discuss their treatment options with their physician. Prior research suggests such an online support system may increase patients’ sense of control and psychological outcomes.11,12,33 Recent data further suggests that cancer patients who utilize the internet are likely to take a more active role in their medical decision making.14

Despite the potential benefits, the discussion of arthralgia and other side effects of AIs may have negative consequences on adherence behavior. Some women voiced concerns over initiating AIs based on reading other women’s posts. Others decided to definitively stop the AI prior to their doctor’s appointment (see quote). A well-known “nocebo” effect, (i.e. knowing a side effect will likely make an individual attribute the side effect to a therapy) exists in clinical context.34 Given that most women who are about to start AIs are postmenopausal, some will likely experience arthralgia due to aging, among other chronic health conditions (e.g. osteoarthritis). Our finding of online communication about AI-related arthralgia raises concerns that some women who read the posts may have a higher pre-drug expectation of side effects, and, thus may excessively attribute their symptoms to AIs.

This study has several limitations. First, our unit of analysis was internet posts, not individuals; thus, some individuals may contribute multiple posts and their opinions would have greater weight than those who posted once or never. However, those who were more vocal probably had more influence on other individuals; thus, our unit of analysis likely captures what matters in online communication. It is important to acknowledge that those individuals who chose not to use internet message boards may have different symptom experiences than those who posted messages. Secondly, individuals volunteered information rather than providing forced-responses in a standardized survey; thus, the count information cannot serve as prevalence of side effects. However, the spontaneous nature of online posting may help identify issues that are more central to majority of patients’ experiences of using drugs. Using more in-depth qualitative methods35 may provide richer descriptions of patient experiences and teach us how communication patterns may influence subsequent reporting of drug side effects and drug use behaviors. Lastly, we chose to analyze the online discussion of side effects by breast cancer survivors on one class of drugs to begin understanding several issues surrounding a focused topic. Our findings should be applied in different online populations for different types of drugs to determine the generalizability of our results.

As online social media continues to evolve, it will play an increasingly large role in modern living, including pharmaceutical marketing.36 Our study suggests that information extraction from online social media may be an important tool in pharmacovigilance to understand patient perceptions of drug side effects and examine potential effects on reported adherence. Internet social media provides a unique forum to capture spontaneous and anonymous perspectives of patients from wide geographic areas; these perspectives may be difficult to capture in a clinical trial, survey, or administrative data settings. Thus, continued development data mining of online social media for pharmacovigilance research will provide complementary information to guide patients and health care providers to use drugs safely. Lastly, health care providers should be aware of these online communications and facilitate patient-centered decision making about management of drug side effects.

TAKE HOME MESSAGES.

Patients often use online social media to discuss drug side effects and related adherence behaviors

Patients offer strategies to deal with drug side effects and provide support to each other

Text mining of social media may be a way to conduct pharmacovigilance to generate testable hypothesis

Acknowledgments

FUNDING: This project is supported by a challenge grant from the National Library of Medicine (RC1LM010342). Dr. Mao is supported by the American Cancer Society (CCCDA-08-107-03) and National Institutes of Health (1K23 AT004112-04).

Footnotes

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Library of Medicine or the National Institutes of Health.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

Dr. Mao served as an advisor to Pfizer on research unrelated to breast cancer. Dr. Leonard received research funding from AstraZeneca for studies unrelated to breast cancer. Dr. Hennessy received research funding from AstraZeneca and consulted with Novartis for research unrelated to breast cancer. The other authors had no conflict of interest to report.

References

- 1.Miniwatts Marketing Group. Internet World Stats: Usage and Population Statistics. 2011 http://www.internetworldstats.com/stats.htm.

- 2.Fox S. The social life of health information. Pew Research Center Report. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Armstrong N, Powell J. Patient perspectives on health advice posted on Internet discussion boards: a qualitative study. Health Expect. 2009;12:313–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2009.00543.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Globocan. WHO cancer fact sheet. International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2008. http://globocan.iarc.fr/factsheets/cancers/breast.asp. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burstein HJ, Winer EP. Primary care for survivors of breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1086–94. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200010123431506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mao JJ, Bowman MA, Stricker CT, et al. Delivery of survivorship care by primary care physicians: the perspective of breast cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:933–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.0679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rodgers S, Chen Q. Internet community group participation: Psychosocial benefits for women with breast cancer. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication. 2005;10:00. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schultz PN, Stava C, Beck ML, et al. Internet message board use by patients with cancer and their families. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2003;7:663–7. doi: 10.1188/03.CJON.663-667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Macias W, Lewis LS, Smith TL. Health-related message boards/chat rooms on the Web: discussion content and implications for pharmaceutical sponsorships. J Health Commun. 2005;10:209–23. doi: 10.1080/10810730590934235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nagler RH, Gray SW, Romantan A, et al. Differences in information seeking among breast, prostate, and colorectal cancer patients: Results from a population-based survey. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;81S1:S54–S62. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2010.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eysenbach G. The impact of the Internet on cancer outcomes. CA Cancer J Clin. 2003;53:356–71. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.53.6.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Civan A, Pratt W. Threading together patient expertise. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2007:140–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bartlett YK, Coulson NS. An investigation into the empowerment effects of using online support groups and how this affects health professional/patient communication. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;83:113–9. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2010.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee CJ, Gray SW, Lewis N. Internet use leads cancer patients to be active health care consumers. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;81 (Suppl):S63–9. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2010.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goss PE, Ingle JN, Martino S, et al. A randomized trial of letrozole in postmenopausal women after five years of tamoxifen therapy for early-stage breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1793–802. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coombes RC, Hall E, Gibson LJ, et al. A randomized trial of exemestane after two to three years of tamoxifen therapy in postmenopausal women with primary breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1081–92. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Howell A, Cuzick J, Baum M, et al. Results of the ATAC (Arimidex, Tamoxifen, Alone or in Combination) trial after completion of 5 years' adjuvant treatment for breast cancer. Lancet. 2005;365:60–2. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17666-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burstein HJ, Winer EP. Aromatase inhibitors and arthralgias: a new frontier in symptom management for breast cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:3797–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.9529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mao JJ, Stricker C, Bruner D, et al. Patterns and risk factors associated with aromatase inhibitor-related arthralgia among breast cancer survivors. Cancer. 2009;115:3631–9. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Crew KD, Greenlee H, Capodice J, et al. Prevalence of joint symptoms in postmenopausal women taking aromatase inhibitors for early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:3877–83. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.10.7573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mao JJ, Su HI, Feng R, et al. Association of functional polymorphisms in CYP19A1 with aromatase inhibitor associated arthralgia in breast cancer survivors. Breast Cancer Res. 2011;13:R8. doi: 10.1186/bcr2813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morales L, Pans S, Verschueren K, et al. Prospective study to assess short-term intra-articular and tenosynovial changes in the aromatase inhibitor-associated arthralgia syndrome. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:3147–52. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.4005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Donnellan PP, Douglas SL, Cameron DA, et al. Aromatase inhibitors and arthralgia. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:2767. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hershman DL, Kushi LH, Shao T, et al. Early discontinuation and nonadherence to adjuvant hormonal therapy in a cohort of 8,769 early-stage breast cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4120–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.9655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hershman DL, Shao T, Kushi LH, et al. Early discontinuation and non-adherence to adjuvant hormonal therapy are associated with increased mortality in women with breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010 doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-1132-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chlebowski RT. Aromatase inhibitor-associated arthralgias. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:4932–4. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.3270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Benton A, Ungar L, Hill S, et al. Identifying potential adverse effects using the web: A new approach to medical hypothesis generation. J Biomed Inform. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2011.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Benton A, Hill S, Ungar L, et al. A system for de-identifying medical message board text. Ninth International Conference on Machine Learning and Applications. 2010:485–490. [Google Scholar]

- 29.FDA. [Accessed April 28, 2011];The Adverse Event Reporting System (AERS): older quarterly data files. http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Surveillance/AdverseDrugEffects/ucm083765.htm.

- 30.Su HI, Sammel MD, Springer E, et al. Weight gain is associated with increased risk of hot flashes in breast cancer survivors on aromatase inhibitors. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010 doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-0802-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Basch E. The missing voice of patients in drug-safety reporting. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:865–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0911494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Painter JE, Borba CP, Hynes M, et al. The use of theory in health behavior research from 2000 to 2005: a systematic review. Ann Behav Med. 2008;35:358–62. doi: 10.1007/s12160-008-9042-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Winzelberg AJ, Classen C, Alpers GW, et al. Evaluation of an internet support group for women with primary breast cancer. Cancer. 2003;97:1164–73. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barsky AJ, Saintfort R, Rogers MP, et al. Nonspecific medication side effects and the nocebo phenomenon. Jama. 2002;287:622–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.5.622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Medawar C, Herxheimer A, Bell J, et al. Paroxetine, Panorama and user reporting of ADRs: Consumer intelligence matters in clinical practice and post-marketing drug surveillance. International Journal of Risk & Safety in Medicine. 2002;15:161–169. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Greene JA, Kesselheim AS. Pharmaceutical marketing and the new social media. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:2087–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1004986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]