Abstract

STUDY DESIGN

Cross-sectional study.

OBJECTIVE

To examine associations between frequent bilateral knee pain (BKP) and unilateral knee pain (UKP) and health-related quality of life (QoL). We hypothesized that frequent BKP would be associated with poorer health-related QoL than would frequent UKP and no knee pain.

BACKGROUND

Knee pain is one of the most frequently reported types of joint pain among adults in the United States. It is the most frequent cause of limited physical function, disability, and reduced QoL.

METHODS

Data were collected from the Osteoarthritis Initiative public-use data sets. Health-related QoL was assessed in 2481 participants (aged 45–79 years at baseline). The Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score QoL subscale (knee-specific measure) and the physical component summary and mental component summary (MCS) scores of the Medical Outcomes Study 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-12) (generic measure) were used to assess health-related QoL. Multiple regression analyses were used to examine the relationships between frequent knee pain and health-related QoL, adjusted for sociodemographic and health covariates.

RESULTS

Compared with subjects with no knee pain, subjects with frequent BKP and UKP had significantly lower scores on the Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score QoL subscale (mean difference, −35.2; standard error [SE], 0.86; P<.001 and mean difference, −29.2; SE, 0.93; P<.001; respectively) and the SF-12 physical component summary score (mean difference, −6.25; SE, 0.41; P<.001 and mean difference, −4.10, SE, 0.43; P<.00; respectively), after controlling for sociodemographic and health covariates. The SF-12 MCS score was lower among those with BKP (−1.29; SE, 0.42; P<.001). Frequent UKP was not associated with the SF-12 MCS.

CONCLUSIONS

Subjects with frequent BKP had lower health-related QoL than those with frequent unilateral or no knee pain, as reflected in lower Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Socre QoL subscale and SF-12 physical component summary and MCS scores.

Keywords: cross-sectional study, knee joint, pain, quality of life

INTRODUCTION

Knee pain is one of the most frequently reported types of joint pain among adults in the United States.31 In 2006, 18% of adults experiencing some type of joint pain during the preceding 30 days reported knee pain.37 It is the most frequent cause of limited physical function, disability, and reduced quality of life (QoL).18,20,21 In addition, knee pain has been established as the major reason for knee replacement, especially among people with knee osteoarthritis (OA).12 An estimated $3.4–13.2 billion is spent per year on job-related knee pain costs in the United States.13 Individuals with knee pain experience progressive loss of function, decline in health-related QoL, and display increasing dependence during activities of daily living.26

Few studies have examined knee pain and location in adults with OA or at high risk for OA. For example, Noll,32 in a cross-sectional study of 32 elderly patients, found that unilateral knee pain (UKP) was associated with leg-length discrepancy and osteoarthritic knee pain. In a recent longitudinal study, UKP and knee OA, comorbidities, and increasing chair-stand time were the most significant factors associated with reduced health-related QoL among 333 community-dwelling Japanese women.33 Data from the Japanese Research on Osteoarthritis Against Disability study found that low back and knee pain were associated with health-related QoL, using generic measures.29 Given that the proportion of adults undergoing knee replacement has increased in recent years and is expected to increase further,31 it is recommended that the impact of knee pain on QoL be quantified by both generic and specific measures of health-related QoL.

Health-related QoL is receiving increased attention as an outcome measure for knee pain.15 This measure reflects the impact of health status on one’s ability to function and perceived well-being in the physical, mental, and social domains of life, independent of political, economic, or social status.28 A variety of generic and knee-specific instruments for the assessment of health-related QoL are available, including the Medical Outcomes Study 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36) and the Medical Outcomes Study 12-Item Short-Form health Survey (SF-12),25 the Western Ontario and McMaster Osteoarthritis Universities Osteoarthritis Index,8 and the Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS).38 Whereas the SF-36 and SF-12 are generic health-related QoL measures, the Western Ontario and McMaster Osteoarthritis Universities Osteoarthritis Index and the KOOS are joint-specific instruments that were developed to assess the health-related QoL of subjects with knee pain or other knee disorders. The objective of the current study was to examine the association between frequent knee pain (bilateral and unilateral) and health-related QoL, assessed using knee-specific and generic measures. We hypothesized that frequent bilateral knee pain (BKP) would be associated with poorer health-related QoL than would frequent UKPl and no knee pain.

METHODS

Data Source and Study Sample

The Osteoarthritis Initiative (OAI) is a publicly and privately funded, ongoing longitudinal, multicenter study examining the onset and progression of knee OA.34 Adults aged 45 to 79 years at the time of enrollment who had knee OA or were at high risk of knee OA were recruited from 4 clinical sites in the United States (Baltimore, MD; Pittsburgh, PA; Pawtucket, RI; and Columbus, OH) between February 2004 and May 2006. Details of the OAI study criteria can be found online at http://www.oai.ucsf.edu/datarelaese/About.asp. The Institutional Review Board of the OAI Coordinating Center, University of California San Francisco, approved the study protocol.

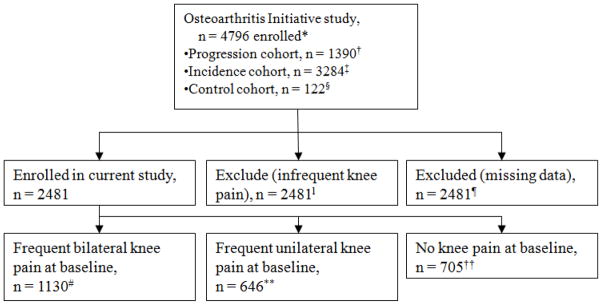

The sample for the current study was drawn from baseline (wave 0–2009) of the OAI database, which is publicly accessible at http://www.oai.ucsf.edu/. Data set 0.2.2 was used for this study. A sample of 2481 subjects was selected from the 4976 subjects enrolled in the OAI using the following inclusion criteria: frequent BKP (frequent pain in both knees), UKP (frequent pain in one knee, no pain in the other knee), or no knee pain. The OAI sample includes progression, incidence, and control cohorts (FIGURE 1). Subjects from all ethnic groups included in the OAI were enrolled in the present study. Participants who reported infrequent UKP or BKP, those with missing data regarding which knee was eligible for the study, and those who refused to participate were excluded from the study. Excluded subjects (n = 2315) were significantly more likely than included subjects (n = 2481) to be younger (61.0 years), unmarried (32%), and living alone (22%). They were also significantly more likely to have healthcare coverage (97%), to have fallen during past 12 months (64.9%), and have fewer depressive symptoms (8%) and less comorbidities (23%) than those included in the study.

FIGURE 1.

Flow diagram of selection and classification of subjects enrolled in the Osteoarthritis Initiative study that was included in the present study.

*The Osteoarthritis Initiative Study has made large, heterogeneous data sets available for public use (http://oai.epi-ucsf.org/datarelease/).

†Subjects with symptomatic tibiofemoral knee osteoarthritis at baseline.

‡Subjects with no symptomatic tibiofemoral osteoarthritis in either knee at baseline.

§Subjects with no pain, aching, or stiffness in either knee in the past year; no radiographic finding of osteoarthritis; and no eligibility risk factors.

lInfrequent pain in one knee and no pain in the other knee or infrequent pain in both knees.

¶Data missing for the variable indicating which knee was eligible for the study.

#Frequent pain in both knees.

**Frequent pain in one knee, no pain in the other knee.

††No pain in either knee.

Subjects were classified as having frequent knee pain if they answered yes to the following questions: “During the past 12 months, have you had pain, aching or stiffness in or around your (right/left) knee?” and “During the past 12 months, have you had pain, aching or stiffness in or around your (right/left) knee on most days for at least 1 month?”. Subjects were classified as having infrequent knee pain if they answered yes to the following question: “During the past 12 months, have you had pain, aching or stiffness in or around your (right/left) knee?” and no to the following question: “During the past 12 months, have you had pain, aching or stiffness in or around your (right/left) knee on most days for at least 1 month?”. Similar questions have been used in the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging17 and in other population-based surveys.9

Measures

Health-related QoL was assessed using knee-specific (KOOS-QoL subscale) and generic (SF-12) measures.4 The KOOS was developed to assess patients’ opinions about their knees and associated problems. It consists of 5 subscales: pain, other symptoms, function in activities of daily living, function in sport and recreation, and knee-related QoL. Data from the KOOS QoL subscale were used in this study. The KOOS QoL subscale has 4 items: knee problems, knee damage, knee trouble and knee difficulty. Scores for each item question ranges from 0 (no problem) to 4 (extreme problems). A summary score was calculated by summing item scores and then transforming them to a 0-to-100 scale, with 0 representing extreme knee problems and 100 representing no knee problem.38

The SF-12 is a shorter version of the SF-36. It comprises 12 questions measuring 8 dimensions of health: physical function, role limitations related to physical problems, bodily pain, general health perception, vitality, social functioning, role limitations due to emotional problems, and mental health. These dimensions are represented by physical component summary (PCS) and mental component summary (MCS) scores. The range of possible values for SF-12 final scores is 0 to 100. Higher scores indicate better health state.40

Covariates

The following demographic and socioeconomic variables were included in analyses: age (years), sex (female/male), race (nonwhite/white), education (categorized in 4 levels), marital status (married/unmarried), annual income (less than $50,000/$50,000 or greater), healthcare coverage (yes/no), employment (employed/unemployed) and social support (living alone/with spouse). Validated general health measures of comorbidity (Carlson index),14 depression (Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale; severe depressive symptoms defined as score of 16 or greater),7 fall (self-report) and body mass index (BMI [kg/m2] were used.22

Statistical Analysis

Independent-sample t tests and chi-squared tests were used to determine whether the sociodemographic or other characteristics of subjects enrolled in the OAI who were included and excluded from the current study differed. Chi-squared tests and analysis of variance were used to examine the distributions of study participants’ characteristics according to frequent BKP and UKP status. Three multiple linear regression models were used to examine the associations between frequent BKP and UKP and KOOS QoL subscale and SF-12 (PCS and MCS) scores. Model 1 was unadjusted; model 2 controlled for sociodemographic variables (age, sex, race, education, marital status, income, and health insurance coverage); and model 3 controlled for all variables in model 2, as well as BMI, depressive symptoms, falls, and comorbidities. Model 2 and 3 were conducted to test whether the association between BKP/UFP and KOOS QoL subscale/SF-12 remained significant All analyses were conducted using SAS Version 9.1.3 (SAS Institute, Inc, Cary, NC), with a significance level of .05.

RESULTS

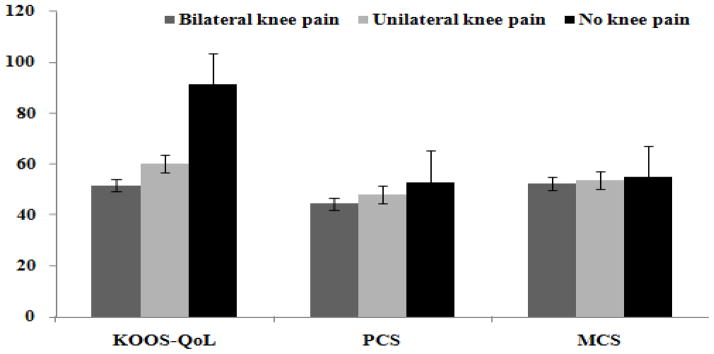

Of the 2481 participants, 1130 (45.55%) had frequent BKP, 646 (26.04%) had frequent UKP, and 705 (28.42%) had no knee pain (TABLE 1). Participants with frequent BKP were significantly more likely than those with frequent UKP or no knee pain to be younger (59.9 years), nonwhite (61.1%), female (47.8%), to have low education (53.9%) and low income levels (53%), higher BMI (30.0 kg/m2), to live single (47.5%), and to report more depressive symptoms (59.7%). FIGURE 2 illustrates the overall adjusted health-realted QoL scores according to knee pain status. Bilateral knee pain yielded the lowest score on the KOOS QoL subscale (mean difference, −35.2; P<.0001) and the PCS of the SF-12 (mean difference, −6.25; P<.0001), even after controlling all covariates, but BKP had the lowest score on the MCS of the SF-12 (mean difference −1.29; P = .002) after controlling only sociodemographic variables.

TABLE 1.

DESCRIPTIVE CHARACTERISTICS OF STUDY PARTICIPANTS (N = 2481)*

| Characteristic | Frequent bilateral knee pain (n = 1130, 45.55%) | Frequent unilateral knee pain (n = 646, 26.04%) | No knee pain n = (705, 28.42%) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD age, y | 59.9 ± 8.9 | 61.1 ± 9.4 | 63.5 ± 9.4 | <.0001 |

| Gender | .0005 | |||

| Male | 439 (42.4) | 311 (30.0) | 286 (27.6) | |

| Female | 691 (47.8) | 335 (23.2) | 419 (29.0) | |

| Race | <.0001 | |||

| Non-white | 382 (61.12) | 159 (25.44) | 84 (13.44) | |

| White or Caucasian | 695 (42.9) | 302 (18.7) | 622(38.4) | |

| Marital status | <.0001 | |||

| Married | 673 (42.01) | 426 (26.59) | 503 (31.40) | |

| Unmarried | 457 (51.99) | 220 (25.03) | 202 (22.98) | |

| Social support | .55 | |||

| Living alone | 259 (47.52) | 139 (25.50) | 147 (26.97) | |

| Living with spouse | 871 (44.99) | 507 (26.19) | 558 (28.82) | |

| Education level | <.0001 | |||

| High school or less | 245 (53.96) | 112 (24.67) | 97 (21.37) | |

| Some college | 324 (52.68) | 146 (23.74) | 145 (23.58) | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 278 (39.89) | 196 (28.12) | 223 (31.99) | |

| Graduate degree | 283 (39.58) | 192 (26.85) | 240 (33.57) | |

| Employment status | .33 | |||

| Employed/self-employed | 715 (46.70) | 388 (25.34) | 428 (27.96) | |

| Unemployed/retired | 415 (43.68) | 258 (27.16) | 277 (29.16) | |

| Yearly income | <.0001 | |||

| <$50,000 | 510 (52.90) | 224 (23.24) | 230 (23.86) | |

| >$50,000 | 620 (40.87) | 422 (27.82) | 475 (31.31) | |

| Healthcare coverage | <.0001 | |||

| Yes | 1065 (44.73) | 622 (26.12) | 694 (29.15) | |

| No | 65 (65.0) | 24 (24.0) | 11 (11.0) | |

| Fall during past 12 mo | .0009 | |||

| No | 712 (43.26) | 430 (26.12) | 504 (30.62) | |

| Yes | 418 (50.06) | 216 (25.87) | 201 (24.07) | |

| Depressive symptoms† | <.0001 | |||

| Yes | 172 (59.72) | 74 (25.69) | 42 (14.58) | |

| No | 958 (43.68) | 572 (26.08) | 663 (30.23) | |

| Comorbidity score‡ | <.0001 | |||

| 0 | 776 (43.18) | 465 (25.88) | 556 (30.94) | |

| 1 | 198 (49.62) | 110 (27.57) | 91 (22.81) | |

| ≥2 | 156 (54.74) | 71 (24.91) | 58 (20.35) | |

| Mean ± SD BMI, kg/m2 | 29.8 ± 5.1 | 28.6 ± 4.5 | 27.4 ± 4.7 | <.0001 |

Abbreviation: BMI, body mass index.

Values are n (%) unless otherwise indiacated.

Depressive symptoms were measured using Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale; severe depressive symptoms were defined as scores of 16 or greater.

Comorbidity score was measured using the Carlson Index.

FIGURE 2.

Scores reflecting health-related quality of life among subjects with frequent bilateral knee pain, frequent unilateral knee pain, and no knee pain.

Abbreviations: KOOS, Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score; MCS, mental component summary score of the Medical Outcomes Study 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey; PCS, physical component summary score of the Medical Outcomes Study 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey; QoL, quality of life.

TABLE 2 presents the results of multiple regression analyses of associations between frequent knee pain status and KOOS QoL score. In model 1, participants with frequent BKP scored 39.4 points less on the KOOS QoL subscale than those with no knee pain (P<.0001), and those with UKP scored 30.8 points less on the KOOS QoL than those with no knee pain (P<.0001). In model 2, which included sociodemographic variables, the associations between frequent BKP and UKP and KOOS QoL scores were slightly weaker, but remained statistically significant in comparison with no knee pain (β = −36.7; standard error [SE], 0.87 and β = −29.8; SE, 0.93, respectively; both P<.0001). In model 3, which additionally controlled for BMI, falls, depression, and comorbidities, the associations of frequent BKP and UKP with KOOS QoL scores were attenuated by approximately 11% [(39.4 – 35.2)/39.4 = 0.11] and 5% [(30.8 – 29.2)/30.8 = 0.05], respectively, but remained statistically significant (β = −35.2 and −29.2, respectively). Compared with the unadjusted analysis, the inclusion of all covariates in the model increased the explained variance (R2) from 0.31 to 0.57. Other variables significantly associated with KOOS QoL scores in model 3 were race, education, falls, depression, and BMI (TABLE 2).

TABLE 2.

REGRESSION ANALYSIS OF ASSOCIATIONS BETWEEN FREQUENT KNEE PAIN AND KOOS QUALITY OF LIFE SUBSCALE SCORE (N = 2481)

| Regression Term | Model 1* (n = 1835) | Model 2† (n = 1349) | Model 3‡ (n = 1349) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| β | SE | P Value | β | SE | P Value | β | SE | P Value | |

| Constant | 55.9 | 0.59 | <.0001 | 41.5 | 3.75 | <.0001 | 59.9 | 4.77 | <.0001 |

| No knee pain§ (reference) | |||||||||

| Frequent unilateral knee painl | −30.8 | 0.93 | <.0001 | −29.8 | 0.93 | <.0001 | −29.2 | 0.93 | <.0001 |

| Frequent bilateral knee pain¶ | −39.4 | 0.84 | <.0001 | −36.7 | 0.87 | <.0001 | −35.2 | 0.86 | <.0001 |

| Age | −0.08 | 0.05 | .07 | 0.06 | 0.05 | .21 | |||

| Sex (female versus male) | −0.76 | 0.84 | .37 | −0.34 | 0.83 | .68 | |||

| Race (white versus nonwhite) | 6.43 | 1.0 | <.0001 | 4.95 | 1.0 | <.0001 | |||

| Marital status (married versus unmarried/separated) | 2.23 | 1.26 | .08 | 1.56 | 1.23 | .21 | |||

| Social support (live single versus live with others) | −1.0 | 1.37 | .44 | −0.91 | 1.34 | .49 | |||

| Education (high school or less versus some college/graduates) | 1.75 | 0.41 | <.0001 | 1.27 | 0.41 | 0.0019 | |||

| Income (< $50K versus > $50K) | 1.20 | 0.97 | .21 | −0.05 | 0.95 | .96 | |||

| Healthcare coverage (yes versus no) | 2.0 | 2.1 | .33 | 1.32 | 2.0 | .52 | |||

| Fallen, past 12 mo (yes versus no) | −1.79 | 0.59 | .0025 | ||||||

| Depressive symptoms (yes versus no) | −7.80 | 1.26 | <.0001 | ||||||

| Comorbidity (yes versus no) | −0.99 | 0.83 | .24 | ||||||

| BMI | −0.53 | 0.08 | <.0001 | ||||||

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; KOOS, Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score; SE, standard error.

Unadjusted. Adjusted R2 = 0.31.

Adjusted for age, sex, race, education, marital status, social support, income, and healthcare coverage. Adjusted R2 = 0.54.

Additionally adjusted for BMI, falls, depression, and comorbidities. Adjusted R2 = 0.57.

No pain in either knee.

Frequent pain in one knee and no pain in other knee.

Frequent pain in both knees.

TABLE 3 shows the results of multiple regression analyses of associations between frequent knee pain status and SF-12 PCS scores. In model 1, participants with frequent BKP scored 8.50 points less on the PCS than those with no knee pain (P<.0001), and those with UKP scored 4.79 points less on the PCS than those with no knee pain (P<.0001). In model 2, which included sociodemographic variables, the associations of frequent BKP and UKP with PCS scores were slightly weaker, but remained statistically significant in comparison with no knee pain (β = −7.26; SE, 0.43 and β = −4.50; SE, 0.43, respectively; both P<.0001). In model 3, which additionally controlled for BMI, falls, depression, and comorbidities, the associations of frequent BKP and UKP with PCS scores were attenuated by approximately 26% [(8.50 – 6.25)/8.50 = 0.26] and 14% [(4.79 – 4.10)/4.79 = 0.14], respectively, but remained statistically significant (β = −6.25 and −4.10, respectively). Compared with the unadjusted analysis, the inclusion of all covariates in the model increased the explained variance (R2) from 0.17 to 0.35. Other variables significantly associated with SF-12 PCS scores in model 3 were age, race, education, income, falls, health coverage, fall depression, and BMI (TABLE 3).

TABLE 3.

REGRESSION ANALYSIS OF ASSOCIATIONS BETWEEN FREQUENT KNEE PAIN AND SF-12 PHYSICAL COMPONENT SUMMARY SCORE (N = 2481)

| Regression Term | Model 1* (n = 1809) | Model 2† (n = 1344) | Model 3‡ (n = 1344) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| β | SE | P Value | β | SE | P Value | β | SE | P Value | |

| Constant | 46.1 | 0.29 | <.0001 | 45.4 | 1.83 | <.0001 | 57.6 | 2.28 | <.0001 |

| No knee pain§ (reference) | |||||||||

| Frequent unilateral knee painl | −4.79 | 0.45 | <.0001 | −4.50 | 0.43 | <.0001 | −4.10 | 0.43 | <.0001 |

| Frequent bilateral knee pain¶ | −8.50 | 0.44 | <.0001 | −7.26 | 0.43 | <.0001 | −6.25 | 0.41 | <.0001 |

| Age | −0.13 | 0.02 | <.0001 | −0.12 | 0.02 | <.0001 | |||

| Sex (female versus male) | −0.09 | 0.42 | .82 | 0.49 | 0.41 | .23 | |||

| Race (white versus nonwhite) | 3.26 | 0.51 | <.0001 | 2.23 | 0.49 | <.0001 | |||

| Marital status (married versus unmarried/separated) | 0.86 | 0.64 | .18 | 0.72 | 0.61 | .24 | |||

| Social support (live single versus live with others) | −0.28 | 0.69 | .69 | −0.29 | 0.66 | .66 | |||

| Education (high school or less versus some college/graduates) | 1.29 | 0.20 | <.0001 | 0.95 | 0.19 | <.0001 | |||

| Income (< $50K versus > $50K) | 2.18 | 0.48 | <.0001 | 1.32 | 0.46 | 0.0047 | |||

| Healthcare coverage (yes versus no) | 4.02 | 1.05 | 0.0001 | 3.84 | 1.0 | 0.0001 | |||

| Fallen, past 12 mo (yes versus no) | −2.15 | 0.29 | <.0001 | ||||||

| Depressive symptoms (yes versus no) | −2.27 | 0.62 | 0.0002 | ||||||

| Comorbidity (yes versus no) | −0.67 | 0.41 | 0.10 | ||||||

| BMI | −0.38 | 0.04 | <.0001 | ||||||

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; SE, standard error; SF-12, Medical Outcomes Study 12-Item Short-From Health Survey.

Unadjusted. Adjusted R2 = 0.17.

Adjusted for age, sex, race, education, marital status, social support, income, and healthcare coverage. Adjusted R2 = 0.28.

Additionally adjusted for BMI, falls, depression, and comorbidities. Adjusted R2 = 0.35.

No pain in either knee.

Frequent pain in one knee and no pain in other knee.

Frequent pain in both knees.

TABLE 4 shows the results of regression analyses of frequent knee pain status with SF-12 MCS scores. In model 1, participants with frequent BKP scored 2.48 less in the MCS than those with no knee pain (P <.0001). In model 2, which included sociodemographic variables, the association of frequent BKP with MCS scores was slightly weaker but remained statistically significant (β = −1.29; SE, 0.42; P = .002) compared with no knee pain. In model 3, which additionally controlled for BMI, falls, depression, and comorbidities, the association of frequent BKP with MCS scores was not statistically significant. Unilateral knee pain was not significantly associated with MCS scores. Compared with the unadjusted analysis, the inclusion of all covariates in the model increased the explained variance (R2) from 0.02 to 0.38. Other variables significantly associated with SF-12 MCS scores in model 3 were age, marital status, income, BMI, and depression (TABLE 4).

TABLE 4.

REGRESSION ANALYSIS OF ASSOCIATIONS BETWEEN FREQUENT KNEE PAIN AND SF-12 MENTAL COMPONENT SUMMARY SCORE (N = 2481)

| Regression Term | Model 1* (n = 1809) | Model 2† (n = 1344) | Model 3‡ (n = 1344) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| β | SE | P Value | β | SE | P Value | β | SE | P Value | |

| Constant | 52.9 | 0.27 | <.0001 | 38.6 | 1.76 | <.0001 | 47.7 | 2.00 | <.0001 |

| No knee pain§ (reference) | |||||||||

| Frequent unilateral knee painl | −1.0 | 0.41 | .013 | −0.48 | 0.41 | .24 | 0.04 | 0.35 | .91 |

| Frequent bilateral knee pain¶ | −2.48 | 0.41 | <.0001 | −1.29 | 0.42 | .002 | −0.6 | 0.35 | .091 |

| Age | 0.18 | 0.02 | <.0001 | 0.14 | 0.02 | <.0001 | |||

| Sex (female versus male) | 0.52 | 0.41 | .20 | 0.2 | 0.34 | .41 | |||

| Race (white versus nonwhite) | −0.05 | 0.49 | .92 | −0.17 | 0.42 | .68 | |||

| Marital status (married versus unmarried/separated) | 0.64 | 0.63 | .30 | −0.13 | 0.51 | .79 | |||

| Social support (live single versus live with others) | 0.31 | 0.68 | .65 | 0.33 | 0.56 | .55 | |||

| Education (high school or less versus some college/graduates) | 0.48 | 0.20 | .019 | 0.17 | 0.17 | .30 | |||

| Income (< $50K versus > $50K) | 2.0 | 0.47 | <.0001 | 1.0 | 0.39 | .009 | |||

| Healthcare coverage (yes versus no) | 0.59 | 1.0 | .57 | −0.72 | 0.84 | .40 | |||

| Fallen, past 12 mo (yes versus no) | −0.22 | 0.25 | .37 | ||||||

| Depressive symptoms (yes versus no) | −14.9 | 0.52 | <.0001 | ||||||

| Comorbidity (yes versus no) | −1.25 | 0.34 | .0003 | ||||||

| BMI | 0.11 | 0.03 | .0016 | ||||||

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; SE, standard error; SF-12, Medical Outcomes Study 12-Item Short-From Health Survey.

Unadjusted. Adjusted R2 = 0.02.

Adjusted for age, sex, race, education, marital status, social support, income, and healthcare coverage. Adjusted R2 = 0.08.

Additionally adjusted for BMI, falls, depression, and comorbidities. Adjusted R2 = 0.38.

No pain in either knee.

Frequent pain in one knee and no pain in other knee.

Frequent pain in both knees.

DISCUSSION

Frequent knee pain in adults can affect every aspect of daily life, impacting overall quality of life.2 Very few studies on frequent BKP have focused on psychosocial outcomes, such as health-related QoL. To explore these outcomes, we examined associations between frequent BKP and UKP and health-related QoL using a sample drawn from the OAI study. We found that self-reported frequent BKP and UKP were significantly associated with decreased QoL. Subjects with frequent BKP and UKP scored low on the KOOS QoL subscale and the PCS of the SF-12 compared with those without knee pain, after adjusting for all covariates. No significant association between knee pain (BKP and UKP) and the MCS of the SF-12 was found after adjusting for all covariates. Our findings thus suggest that knee pain negatively impact on physical aspects of health-related QoL, in line with data from the OAI19 and the Research on Osteoarthritis Against Disability Study.3

Our findings are similar to findings previously reported in the literature. For example, Muraki et al29 in a sample of 767 men participants, found that those with knee pain or OA had decreased scores on the Medical Outcomes Study 8-Item Short-From Health Survey PCS. In another study, Muraki et al30 showed that knee pain was associated with lower score on the the Medical Outcomes Study 8-Item Short-From Health Survey PCS in a sample of 1369 women. Antonopoulou et al5 found that the mental domain of health-related QoL was affected only by self-reported knee pain, and not by other musculoskeletal disorders. Creaby et al,16 in a cohort study of 122 participants showed that UKP was associated with asymmetries in knee biomechanics and that BKP was associated with symmetries in knee biomechanics.

Our findings concur with those of other studies: falls,10 depressive symptoms,19 and high BMI11 were associated with decreased QoL. Falls are a major risk factor for injuries, which leads to poor recovery of physical functions, specifically those needed to carry out activities of daily living, and contributes to decreased QoL.10 The finding that a standardized measure of knee pain can differentiate health-related QoL ratings is important for 3 reasons. First, low SF-12 PCS scores among subjects with frequent BKP are indicators of considerable physical limitations, disability, and poorer QoL in relation to those with frequent UKP and no knee pain.32,42 In addition, knee pain has been associated with lower scores on items pertaining to general health.31 Second, previous research has documented a high rate of global disability among those reporting knee pain.42 Thus, better detection, management, and prevention of knee pain in adults may positively affect health-related QoL among aging adults. Finally, the SF-12 and the KOOS QoL subscale health-related QoL measures capture different aspects of the health related to knee pain.39

Our findings support the need for continued research on interventions that address physical approaches to improved health-related QoL. In adults, physical approaches have been shown to decrease the likelihood of declines in health-related QoL,27 thus they may similarly benefit those with frequent UKP or BKP specifically.24 The incorporation of more physical activity into the lifestyles of adults with knee pain led to improvements in the physical domain of health-related QoL relative to adults with knee pain who is less physically active.1 Clinical trials of physical exercise programs and cross-sectional studies of community-dwelling adults have shown that greater physical activity is associated with better long-term health-related QoL in the adult population.6 Thus, the use of physical interventions to improve health-related QoL should be further examined.

Our study has some limitations. Firs, the cross-sectional analyses do not allow us to determine causality. Second, data on pain and health-related QoL was self-reported. Third, the findings are generalizable to those with Knee OA or at high risk for OA. Our study has several strengths. First, to our knowledge, this study is the first to examine the associations of frequent BKP and UKP with health-related QoL separately in comparison with no knee pain, using well-established and validated measures of health-related QoL. Second, data used in this study were from a large databased sample of the OAI study, with information on well-established and validated measurement of health-related QoL, such as the SF-12 and the KOOS. This novel examination of the effects of knee pain on health-related QoL outcomes contributes to a broader understanding of the impacts of knee pain in adults.41 Third, the major strength of this study is that we have examined pain location (bilateral or unilateral), whereas the majority of the studies examining health-related QoL in patients with knee pain used knee pain without location (unilateral or bilateral), did not report pain frequency 23,29 and were conducted after joint replacement.36

CONCLUSIONS

In analyses controlling for sociodemographic and health-related variables, subjects with frequent BKP and UKP had poorer health-related QoL than did those with no knee pain, and subjects with BKP additionally showed worse physical health than did those with UKP, which further worsened helth-related QoL in these patients. Clinicians should be aware of the possible association between frequent BKP and health-related QoL. Future research should assess potential mediating factors in an effort to improve the QoL of people with frequent BKP or UKP.

KEY POINTS.

FINDINGS

In this cross-sectional study, the physical, but not mental, domain of health-related QoL was poorer among subjects with frequent BKP or UKP than among those with no knee pain, after adjusting for confounders.

IMPLICATION

Physical therapists and other healthcare providers should measure the health-related QoL of patients with knee pain using knee-specific and generic measures to improve outcomes and care.

CAUTION

Subject groups were determined based on a history of self-reported frequent knee pain, and the cross-sectional study design prevented the inference of causality.

Acknowledgments

S. Bindawas and V. Vennu are funded by the Research Centre, College of Applied Medical Sciences, and the Deanship of Scientific Research at King Saud University. S. Al Snih is funded by the UTMB Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center (P30 AG024832)

Footnotes

The Committee on Human Research is the Institutional Review Board for the University of California San Francisco-approved Osteoarthritis Initiative Study (approval number 10.00532).

The authors certify that they have no affiliations with or financial involvement in any organization or entity with a direct financial interest in the subject matter or materials discussed in the article.

COMPETING INTERESTS: The authors declare they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Acree LS, Longfors J, Fjeldstad AS, et al. Physical activity is related to quality of life in older adults. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2006;4:37. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-4-37. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-4-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adegoke BO, Babatunde FO, Oyeyemi AL. Pain, balance, self-reported function and physical function in individuals with knee osteoarthritis. Physiother Theory Pract. 2012;28:32–40. doi: 10.3109/09593985.2011.570858. http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/09593985.2011.570858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Agaliotis M, Fransen M, Bridgett L, et al. Risk factors associated with reduced work productivity among people with chronic knee pain. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2013;21:1160–1169. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2013.07.005. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.joca.2013.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andresen EM, Meyers AR. Health-related quality of life outcomes measures. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2000;81:S30–S45. doi: 10.1053/apmr.2000.20621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Antonopoulou MD, Alegakis AK, Hadjipavlou AG, Lionis CD. Studying the association between musculoskeletal disorders, quality of life and mental health. A primary care pilot study in rural Crete, Greece. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2009;10:143. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-10-143. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1471-2474-10-143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Balboa-Castillo T, Leon-Munoz LM, Graciani A, Rodriguez-Artalejo F, Guallar-Castillon P. Longitudinal association of physical activity and sedentary behavior during leisure time with health-related quality of life in community-dwelling older adults. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2011;9:47. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-9-47. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-9-47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barlow JH, Wright CC. Dimensions of the Center of Epidemiological Studies-Depression Scale for people with arthritis from the UK. Psychol Rep. 1998;83:915–919. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1998.83.3.915. http://dx.doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1998.83.3.915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bellamy N, Buchanan WW, Goldsmith CH, Campbell J, Stitt LW. Validation study of WOMAC: a health status instrument for measuring clinically important patient relevant outcomes to antirheumatic drug therapy in patients with osteoarthritis of the hip or knee. J Rheumatol. 1988;15:1833–1840. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blake VA, Allegrante JP, Robbins L, et al. Racial differences in social network experience and perceptions of benefit of arthritis treatments among New York City Medicare beneficiaries with self-reported hip and knee pain. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;47:366–371. doi: 10.1002/art.10538. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/art.10538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cakar E, Dincer U, Kiralp MZ, et al. Jumping combined exercise programs reduce fall risk and improve balance and life quality of elderly people who live in a long-term care facility. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2010;46:59–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Callegari A, Michelini I, Sguazzin C, Catona A, Klersy C. Efficacy of the SF-36 questionnaire in identifying obese patients with psychological discomfort. Obes Surg. 2005;15:254–260. doi: 10.1381/0960892053268255. http://dx.doi.org/10.1381/0960892053268255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Accessed Jun 12, 2014];Arthritis Program Health Disparities Activities. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/arthritis/data_statistics/disparities.htm.

- 13.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. A National Public Health Agenda for Osteoarthrtitis. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen HY, Baumgardner DJ, Rice JP. Health-related quality of life among adults with multiple chronic conditions in the United States, Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2007. Prev Chronic Dis. 2011;8:A09. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Creaby MW, Bennell KL, Hunt MA. Gait differs between unilateral and bilateral knee osteoarthritis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2012;93:822–827. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2011.11.029. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2011.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Creamer P, Lethbridge-Cejku M, Costa P, Tobin JD, Herbst JH, Hochberg MC. The relationship of anxiety and depression with self-reported knee pain in the community: data from the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. Arthritis Care Res. 1999;12:3–7. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199902)12:1<3::aid-art2>3.0.co;2-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Department of Health Statistics and informatics. Causes of Death 2008: Data Sources and Methods. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Elliott TE, Renier CM, Palcher JA. Chronic pain, depression, and quality of life: correlations and predictive value of the SF-36. Pain Med. 2003;4:331–339. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2003.03040.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grimaldi-Bensouda L, Begaud B, Lert F, et al. Benchmarking the burden of 100 diseases: results of a nationwide representative survey within general practices. BMJ Open. 2011;1:e000215. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000215. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guccione AA, Felson DT, Anderson JJ, et al. The effects of specific medical conditions on the functional limitations of elders in the Framingham Study. Am J Public Health. 1994;84:351–358. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.3.351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hootman JM, Helmick CG. Projections of US prevalence of arthritis and associated activity limitations. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:226–229. doi: 10.1002/art.21562. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/art.21562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jhun HJ, Sung NJ, Kim SY. Knee pain and its severity in elderly Koreans: prevalence, risk factors and impact on quality of life. J Korean Med Sci. 2013;28:1807–1813. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2013.28.12.1807. http://dx.doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2013.28.12.1807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim IJ, Kim HA, Seo YI, et al. Prevalence of knee pain and its influence on quality of life and physical function in the Korean elderly population: a community based cross-sectional study. J Korean Med Sci. 2011;26:1140–1146. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2011.26.9.1140. http://dx.doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2011.26.9.1140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kosinski M, Keller SD, Ware JE, Jr, Hatoum HT, Kong SX. The SF-36 Health Survey as a generic outcome measure in clinical trials of patients with osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis: relative validity of scales in relation to clinical measures of arthritis severity. Med Care. 1999;37:MS23–MS39. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199905001-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Loza E, Lopez-Gomez JM, Abasolo L, Maese J, Carmona L, Batlle-Gualda E. Economic burden of knee and hip osteoarthritis in Spain. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;61:158–165. doi: 10.1002/art.24214. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/art.24214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Macera CA, Jones DA, Yore MM, et al. Prevalence of physical activity, including lifestyle activities among adults—United States, 2000–2001. MMWR. 2003;52:764–769. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moriarty DG, Zack MM, Kobau R. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Healthy Days Measures - population tracking of perceived physical and mental health over time. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2003;1:37. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-1-37. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-1-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Muraki S, Akune T, Oka H, et al. Health-related quality of life in subjects with low back pain and knee pain in a population-based cohort study of Japanese men: the Research on Osteoarthritis Against Disability study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2011;36:1312–1319. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181fa60d1. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181fa60d1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Muraki S, Akune T, Oka H, et al. Impact of knee and low back pain on health-related quality of life in Japanese women: the Research on Osteoarthritis Against Disability (ROAD) Mod Rheumatol. 2010;20:444–451. doi: 10.1007/s10165-010-0307-5. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10165-010-0307-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nguyen US, Zhang Y, Zhu Y, Niu J, Zhang B, Felson DT. Increasing prevalence of knee pain and symptomatic knee osteoarthritis: survey and cohort data. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:725–732. doi: 10.1059/0003-4819-155-11-201112060-00004. http://dx.doi.org/10.1059/0003-4819-155-11-201112060-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Noll DR. Leg length discrepancy and osteoarthritic knee pain in the elderly: an observational study. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2013;113:670–678. doi: 10.7556/jaoa.2013.033. http://dx.doi.org/10.7556/jaoa.2013.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Norimatsu T, Osaki M, Tomita M, et al. Factors predicting health-related quality of life in knee osteoarthritis among community-dwelling women in Japan: the Hizen-Oshima study. Orthopedics. 2011;34:e535–540. doi: 10.3928/01477447-20110714-04. http://dx.doi.org/10.3928/01477447-20110714-04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.The Osteoarthrtitis Initiative. [Accesse June 19, 2014]; Available at: https://oai.epi-ucsf.org/datarelaease/default.asp.

- 35.Peat G, McCarney R, Croft P. Knee pain and osteoarthritis in older adults: a review of community burden and current use of primary health care. Ann Rheum Dis. 2001;60:91–97. doi: 10.1136/ard.60.2.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Protzman NM, Gyi J, Malhotra AD, Kooch JE. Examining the Feasibility of Radiofrequency Treatment for Chronic Knee Pain After Total Knee Arthroplasty. PM R. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2013.10.003. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pmrj.2013.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.QuickStats: percentage of adults* reporting joint pain or stiffness†-National Health Interview Survey,§ United States, 2006. MMWR. 2008;57:467. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Roos EM, Lohmander LS. The Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS): from joint injury to osteoarthritis. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2003;1:64. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-1-64. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-1-64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vennu V, Bindawas SM. Relationship between falls, knee osteoarthritis, and health-related quality of life: data from the Osteoarthritis Initiative study. Clin Interv Aging. 2014;9:793–800. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S62207. http://dx.doi.org/10.2147/CIA.S62207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ware J, Jr, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;34:220–233. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Williams DA, Farrell MJ, Cunningham J, et al. Knee pain and radiographic osteoarthritis interact in the prediction of levels of self-reported disability. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;51:558–561. doi: 10.1002/art.20537. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/art.20537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wood L, Peat G, Thomas E, Hay EM, Sim J. Associations between physical examination and self-reported physical function in older community-dwelling adults with knee pain. Phys Ther. 2008;88:33–42. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20060372. http://dx.doi.org/10.2522/ptj.20060372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]