TMEM16A is an essential component of Ca2+-activated Cl− currents in mouse vomeronasal sensory neurons.

Abstract

Pheromones are substances released from animals that, when detected by the vomeronasal organ of other individuals of the same species, affect their physiology and behavior. Pheromone binding to receptors on microvilli on the dendritic knobs of vomeronasal sensory neurons activates a second messenger cascade to produce an increase in intracellular Ca2+ concentration. Here, we used whole-cell and inside-out patch-clamp analysis to provide a functional characterization of currents activated by Ca2+ in isolated mouse vomeronasal sensory neurons in the absence of intracellular K+. In whole-cell recordings, the average current in 1.5 µM Ca2+ and symmetrical Cl− was −382 pA at −100 mV. Ion substitution experiments and partial blockade by commonly used Cl− channel blockers indicated that Ca2+ activates mainly anionic currents in these neurons. Recordings from inside-out patches from dendritic knobs of mouse vomeronasal sensory neurons confirmed the presence of Ca2+-activated Cl− channels in the knobs and/or microvilli. We compared the electrophysiological properties of the native currents with those mediated by heterologously expressed TMEM16A/anoctamin1 or TMEM16B/anoctamin2 Ca2+-activated Cl− channels, which are coexpressed in microvilli of mouse vomeronasal sensory neurons, and found a closer resemblance to those of TMEM16A. We used the Cre–loxP system to selectively knock out TMEM16A in cells expressing the olfactory marker protein, which is found in mature vomeronasal sensory neurons. Immunohistochemistry confirmed the specific ablation of TMEM16A in vomeronasal neurons. Ca2+-activated currents were abolished in vomeronasal sensory neurons of TMEM16A conditional knockout mice, demonstrating that TMEM16A is an essential component of Ca2+-activated Cl− currents in mouse vomeronasal sensory neurons.

INTRODUCTION

Chemosensation is used by animals to obtain information from the environment and to regulate their behavior. In most mammals, both the main olfactory epithelium and the vomeronasal epithelium are involved in chemodetection (Brennan, 2009; Tirindelli et al., 2009; Touhara and Vosshall, 2009). Sensory neurons in these epithelia detect chemicals and, through different second messenger–mediated transduction pathways, generate action potentials that are transmitted to different regions of olfactory bulbs. In vomeronasal sensory neurons, the binding of chemicals with vomeronasal receptors occurs in the microvilli, at the apical region of the neuron’s dendrite. In rodents, these neurons express one or a few members of three families of G protein–coupled receptors: V1Rs, V2Rs, and formyl peptide receptors (FPRs) (Dulac and Axel, 1995; Herrada and Dulac, 1997; Matsunami and Buck, 1997; Ryba and Tirindelli, 1997; Martini et al., 2001; Liberles et al., 2009; Rivière et al., 2009; Francia et al., 2014). The binding of molecules to vomeronasal receptors activates a phospholipase C pathway, which leads to the influx of Na+ and Ca2+ ions mainly through the transient receptor potential canonical 2 (TRPC2) channel present in the microvilli (Liman et al., 1999; Zufall et al., 2005; Munger et al., 2009), and/or to Ca2 + release from intracellular stores (Kim et al., 2011).

The vomeronasal organ (VNO) plays an important role in the detection of pheromones. Stimulation of the VNO with urine, which contains a rich blend of pheromones, or with individual pheromones, produces a transient increase in intracellular Ca2+ concentration in vomeronasal sensory neurons (Holy et al., 2000; Leinders-Zufall et al., 2000, 2004, 2009; Chamero et al., 2007, 2011; Haga et al., 2010; Kim et al., 2011; Celsi et al., 2012). The intracellular Ca2+ increase has several physiological effects, including activation of ion channels (Liman, 2003; Spehr et al., 2009; Yang and Delay, 2010; Kim et al., 2011, 2012; Dibattista et al., 2012) and modulation, through binding to calmodulin, of sensory adaptation (Spehr et al., 2009).

Previous studies in vomeronasal sensory neurons identified the presence of Ca2+-activated currents; some studies found Ca2+-activated nonselective cation currents (Liman, 2003; Spehr et al., 2009), whereas other studies found Ca2+-activated Cl− currents (Yang and Delay, 2010; Kim et al., 2011; Dibattista et al., 2012). In hamster vomeronasal sensory neurons, Liman (2003) measured Ca2+-activated nonselective cation currents with half-activation occurring at 0.51 mM Ca2+ at −80 mV. In mouse vomeronasal sensory neurons, Spehr et al. (2009) showed that 50 µM Ca2+ activated nonselective cation currents in patches from dendritic knobs from a small population of neurons (12.5%; 7 out of 56). Other recent studies showed that Ca2+-activated Cl− channels contribute to the response of mouse vomeronasal neurons to urine (Yang and Delay, 2010; Kim et al., 2011). Furthermore, the presence of Ca2+-activated Cl− channels in the apical portion of vomeronasal sensory neurons was confirmed by local photorelease of Ca2+ from caged Ca2+ (Dibattista et al., 2012) and by the expression of TMEM16A and TMEM16B (Dibattista et al., 2012), two proteins forming Ca2+-activated Cl− channels (Caputo et al., 2008; Schroeder et al., 2008; Yang et al., 2008; Pifferi et al., 2009a; Stephan et al., 2009; Stöhr et al., 2009; Scudieri et al., 2012; Pedemonte and Galietta, 2014). The aim of this study was to further characterize the ionic nature (in the absence of intracellular K+ to avoid the contribution of Ca2+-activated K+ currents) of Ca2+-activated currents in mouse vomeronasal sensory neurons and to identify the molecular identity of the channels mediating these currents. We performed recordings both in whole-cell and in inside-out patches from dendritic knobs/microvilli of mouse vomeronasal neurons, and we measured only Ca2+-activated Cl− currents with biophysical properties more similar to those of TMEM16A than of TMEM16B. To investigate the role of TMEM16A in vomeronasal neurons, we generated conditional knockout mice for TMEM16A, as the constitutive TMEM16A knockout mice die soon after birth (Rock et al., 2008). Our results demonstrate the presence of Ca2+-activated Cl− currents in the apical portion of vomeronasal sensory neurons of WT mice, confirm that TMEM16A is expressed in mature neurons, and show that TMEM16A is a necessary component of Ca2+-activated Cl− channels in mouse vomeronasal sensory neurons.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Mice were handled in accordance with the Italian Guidelines for the Use of Laboratory Animals (Decreto Legislativo 27/01/1992, no. 116) and European Union guidelines on animal research (no. 86/609/EEC). 2–3-mo-old mice were anaesthetized by CO2 inhalation and decapitated before VNO removal.

To obtain mice in which TMEM16A expression was specifically eliminated in mature vomeronasal sensory neurons, we crossed floxed TMEM16Afl/fl mice, whose generation has been described in detail (Faria et al., 2014; Schreiber et al., 2014), with mice expressing Cre recombinase under the control of the olfactory marker protein (OMP) promoter (OMP-Cre mice; Li et al., 2004; provided by P. Mombaerts, Max Planck Institute of Biophysics, Frankfurt, Germany). Our conditional TMEM16A knockout mice (TMEM16A cKO) were homozygous for the floxed TMEM16A alleles and heterozygous for Cre and OMP. C57BL/6 or TMEM16Afl/fl mice were used as controls. In the following, WT mice correspond to C57BL/6 mice.

Dissociation of mouse vomeronasal sensory neurons

The vomer capsule containing the VNO was removed as described previously (Liman and Corey, 1996; Dean et al., 2004; Shimazaki et al., 2006; Arnson et al., 2010). Vomeronasal sensory neurons were dissociated from the VNO with the enzymatic-mechanical dissociation protocol described in Dibattista et al. (2008, 2012), or with the following slight modifications. In brief, the removed vomer capsule was put into a Petri dish containing divalent-free PBS (Sigma-Aldrich) solution where the VNO was extracted and transferred to a tube containing PBS with 1 mg/ml collagenase (type A), incubated at 37°C for 20 min, and transferred twice to Ringer’s solution with 5% fetal bovine serum for 5 min. The tissue was then cut into small pieces with tiny scissors and gently triturated with a fire-polished Pasteur pipette. Neurons were plated on Petri dishes (WPI) coated with poly-l-lysine and concanavalin A (type V; Sigma-Aldrich) and stored at 4°C.

Patch-clamp recordings and ionic solutions

Vomeronasal sensory neurons were viewed using an inverted microscope (IMT-2 or IX70; Olympus) with 20× or 40× objectives and identified by their bipolar shape, as illustrated in Fig. 1 of Dean et al. (2004). Patch pipettes, pulled from borosilicate capillaries (WPI) with a PC-10 puller (Narishige), had a resistance of ∼3–6 MΩ for whole-cell and 6–8 MΩ for excised patch recordings. Currents were recorded with an Axopatch 1D or 200B amplifier controlled by Clampex 9 or 10 via a Digidata 1332A or 1440 (Molecular Devices). Data were low-pass filtered at 2 or 5 kHz and sampled at 10 kHz. Experiments were performed at room temperature (20–25°C).

For whole-cell recordings, the standard extracellular mammalian Ringer’s solution contained (mM): 140 NaCl, 5 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, 10 glucose, and 1 sodium pyruvate, pH 7.4. The intracellular solution filling the patch pipette contained (mM): 140 CsCl, 10 HEPES, and 10 HEDTA, adjusted to pH 7.2 with CsOH, and no added Ca2+ for the nominally 0-Ca2+ solution, or various added Ca2+ concentrations, as calculated with the program WinMAXC (C. Patton, Stanford University, Stanford, CA), to obtain free Ca2+ in the range between 0.5 and 13 µM (Patton et al., 2004), as described previously (Pifferi et al., 2006, 2009b). The composition of the intracellular solutions containing 2 mM Ca2+ was (mM) 140 CsCl, 10 HEPES, 2 CaCl2 or 145 NaCl, 10 HEPES, and 2 CaCl2, as in Liman (2003). No significant difference was observed among currents activated by the two solutions containing 2 mM Ca2+. For ionic selectivity experiments, NaCl in the extracellular mammalian Ringer’s solution was replaced with equimolar choline chloride, Na-gluconate, or NaSCN. Niflumic acid (NFA), CaCCinh-A01 (Tocris Bioscience), and anthracene-9-carboxylic acid (A9C) were prepared in DMSO as stock solutions at 200 mM, 20 mM, or 1 M, respectively, and diluted to the final concentrations in Ringer’s solution. A gravity perfusion system was used to exchange solutions.

In most whole-cell recordings, we applied voltage steps from a holding potential of 0 mV ranging from −100 to 100 (or 160 mV), followed by a step to −100 mV. A single-exponential function was fitted to instantaneous tail currents to extrapolate the current value at the beginning of the step to −100 mV.

For inside-out recordings, the solution in the patch pipette contained (mM): 140 NaCl, 10 HEDTA, and 10 HEPES, pH 7.2. The bathing solution at the intracellular side of the patch contained (mM): 140 NaCl, 5 EGTA or 10 HEDTA, and 10 HEPES, pH 7.2, and no added Ca2+ for the nominally 0-Ca2+ solution, or various added Ca2+ concentrations, as calculated with the program WinMAXC (C. Patton, Stanford University, Stanford, CA), to obtain free Ca2+ in the range between 0.18 and 100 µM (Patton et al., 2004).

Rapid solution exchange in inside-out patches was obtained with the perfusion Fast-Step (SF-77B; Warner Instruments). For I-V relations of Ca2+-activated currents, a double voltage ramp from −100 to 100 mV and back to −100 mV was applied at 1 mV/ms. The two I-V relations were averaged, and leak currents measured with the same ramp protocol in Ca2+-free solutions were subtracted. For dose–response experiments, a patch was exposed for 1 s to solutions with increasing Ca2+ concentration.

The bath was grounded through a 3-M KCl agar bridge connected to a Ag/AgCl reference electrode. Liquid junction potentials were calculated using Clampex’s Junction Potential Calculator (Molecular Devices), based on the JPCalc program developed by Barry (1994), and applied voltages were corrected offline for the calculated values.

Chemicals, unless otherwise stated, were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich.

Analysis of electrophysiological data

IGOR Pro software (WaveMetrics) was used for data analysis and figures. Data are presented as mean ± SEM and the number of neurons (n). Because most of the data were not normally distributed (Shapiro–Wilk test), statistical significance was determined using Wilcoxon Signed Rank test or Krustal–Wallis test. When a statistically significant difference was determined with Krustal–Wallis analysis, Dunn–Hollander–Wolfe test was done to evaluate which data groups showed significant differences. P-values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant. For the sake of clarity, capacitive transients were trimmed in some traces.

Immunohistochemistry

VNO sections and immunohistochemistry were obtained as described previously (Dibattista et al., 2012). The following primary antibodies were used: rabbit anti-TMEM16A (1:50; Abcam), goat anti-TMEM16A (1:50; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), rabbit anti-TMEM16B (1:100; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), and goat anti-TRPC2 (1:50; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.). The following secondary antibodies obtained from Invitrogen were used: donkey anti–rabbit Alexa Fluor 488 (1:500) and donkey anti–goat Alexa Fluor 594 (1:500). Immunoreactivity was visualized with a confocal microscope (TCS SP2; Leica). Images were acquired using Leica software (at 1,024 × 1,024–pixel resolution) and were not modified other than to balance brightness and contrast. Nuclei were stained by DAPI, and signals were enhanced for better visualization of the vomeronasal epithelium. Control experiments without the primary antibodies gave no signal.

RESULTS

Ca2+-activated Cl− currents in isolated mouse vomeronasal sensory neurons

We first studied Ca2+-activated currents in isolated mouse vomeronasal sensory neurons using the whole-cell voltage-clamp configuration with intracellular solutions containing different amounts of free [Ca2+]i, ranging from nominally 0 Ca2+ up to 2 mM Ca2+. To avoid contributions from Ca2+-activated K+ currents, the intracellular monovalent cation was Cs+ (or Na+ in some experiments in the presence of 2 mM Ca2+).

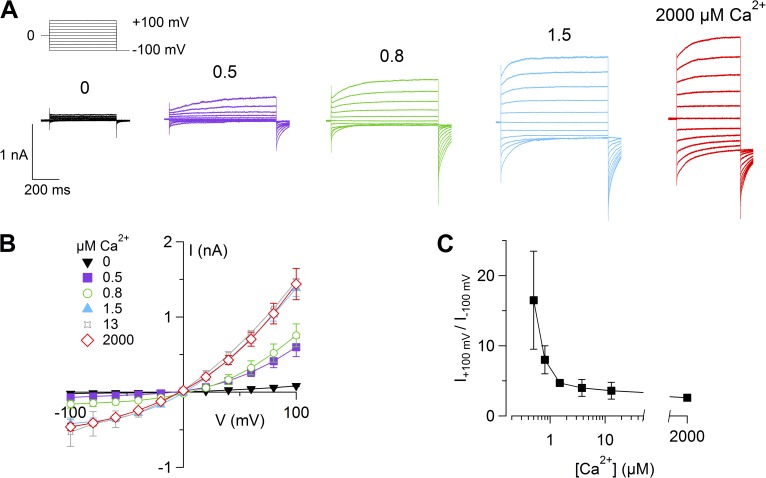

Fig. 1 A shows currents activated by voltage steps between −100 and 100 mV from a holding voltage of 0 mV. The average current in the presence of nominally 0 Ca2+ was 82 ± 9 pA at 100 mV and −20 ± 7 pA at −100 mV (n = 6). When neurons were dialyzed with a solution containing 0.5 µM Ca2+, large currents were recorded in several neurons at positive voltages, with an average value at steady state of 545 ± 96 pA (range of 133 to 1,060 pA) at 100 mV, and −50 ± 17 pA (range of −21 to −163 pA) at −100 mV (n = 10). Further increases in [Ca2+]i produced currents of higher amplitudes, reaching the average of 1,503 ± 146 pA (range of 615 to 3,530 pA) at 100 mV (n = 28) in the presence of 1.5 µM Ca2+. The average current amplitude did not further increase for [Ca2+]i up to 2 mM.

Figure 1.

Ca2+-activated currents in mouse vomeronasal sensory neurons. (A) Representative whole-cell currents recorded from different neurons with a pipette solution containing the indicated [Ca2+]i (for the trace in 2 mM Ca2+, the intracellular solution contained 140 mM NaCl). The holding voltage was 0 mV and voltage steps from −100 to 100 mV with 20-mV increments, followed by a step to −100 mV, were applied as indicated in the top part of the panel. (B) Average steady-state I-V relationships from several neurons at the indicated [Ca2+]i (n = 3–28). (C) Average ratios between steady-state currents measured at 100 and −100 mV at various [Ca2+]i (n = 3–28). Data in B and C are represented as mean ± SEM.

The I-V relations measured at steady state were outwardly rectifying (Fig. 1, B and C), and the rectification index, calculated as the ratio between current at 100 and −100 mV, decreased from 16 ± 7 at 0.5 µM Ca2+ to 5.5 ± 0.6 at 1.5 µM Ca2+ and 3.2 ± 0.3 at 2 mM Ca2+, showing that the I-V relation is Ca2+ dependent and becomes more linear as [Ca2+]i increases.

All together, we tested 178 neurons with various [Ca2+]i and found that 70% of the neurons (124 out of 178) had a Ca2+-activated current. The remaining 30% of the neurons (54 out of 178) did not have Ca2+-activated currents but showed transient voltage-gated inward currents (likely Na+ currents) in response to a depolarizing step to 0 mV from a holding potential of −100 mV.

In the presence of Ca2+, voltage steps induced currents composed of an instantaneous component and a time-dependent relaxation (Figs. 1 A and 2, A and B). The instantaneous component is related to channels open at the holding potential of 0 mV, whereas the time-dependent component is the result of the activation of the channel at a given voltage step, indicating that these channels are regulated both by Ca2+ and by voltage.

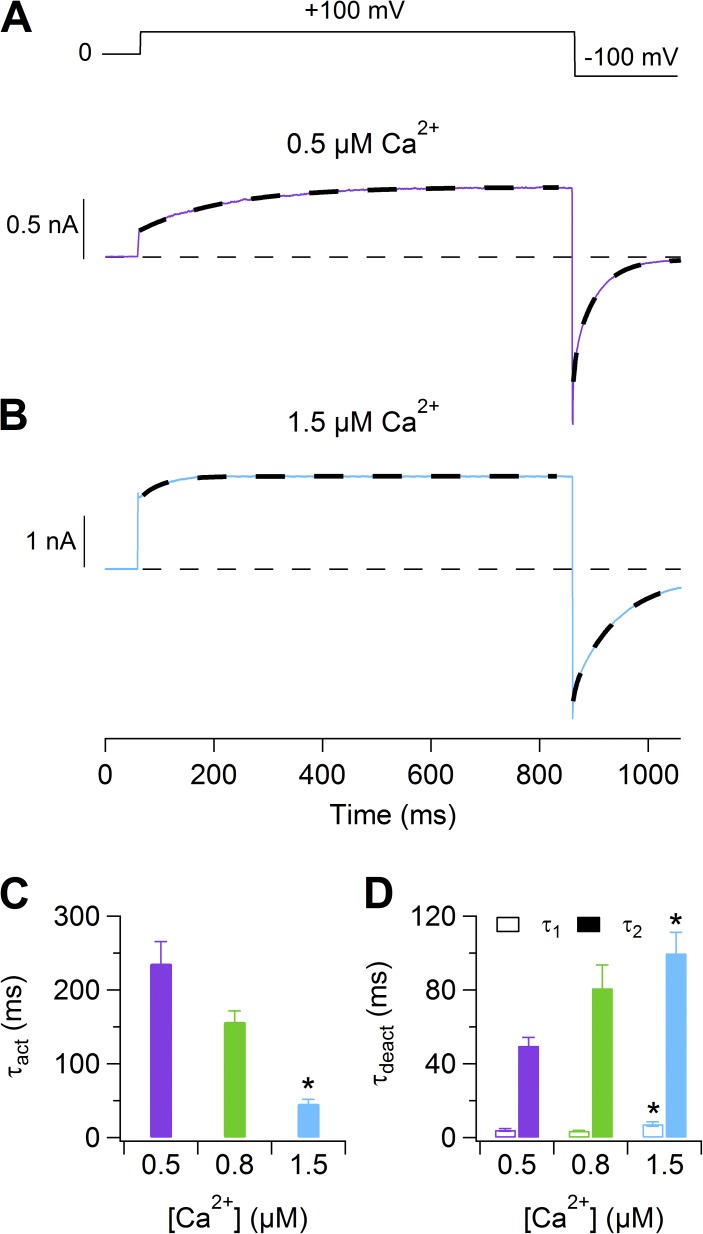

Figure 2.

Activation and deactivation kinetics of Ca2+-activated currents. (A and B) Representative currents with 0.5 and 1.5 µM [Ca2+]i, respectively. The voltage was stepped from 0 to 100 mV and then to −100 mV. Dashed lines are the fit of activation or deactivation time constants obtained, respectively, with a single- or double-exponential function. (C and D) Average activation (from 0 to 100 mV) or deactivation (from 100 to −100 mV) time constants at the indicated [Ca2+]i (n = 5–7). Data in C and D are represented as mean ± SEM (*, P < 0.05; Dunn–Hollander–Wolfe test after Krustal–Wallis analysis between 0.5 and 1.5 µM).

The time-dependent component was fit by a single-exponential function to calculate the time constant of activation, τact. At 100 mV, τact in the presence of 0.5 µM Ca2+ was 235 ± 29 ms (n = 7), decreased to 156 ± 15 ms (n = 8) at 0.8 µM Ca2+, and to 46 ± 6 ms (n = 6) at 1.5 µM Ca2+ (Fig. 2, A–C). At all the tested intracellular Ca2+ concentrations, the activation kinetics did not show voltage dependence in the range between 80 and 160 mV (not depicted).

We examined the deactivation kinetics by measuring the decay of the instantaneous current after a step from 100 to −100 mV (Fig. 2, A, B, and D). The best fit of the current decay was obtained with two exponential functions with average τdeact1 = 4.1 ± 0.7 ms and τdeact2 = 50 ± 4 ms (n = 7) at 0.5 µM Ca2+. Increasing [Ca2+]i to 1.5 µM produced a slower decay of the current, with average τdeact1 = 7 ± 1 ms and τdeact2 = 100 ± 11 ms (n = 5).

These results show that an increase in [Ca2+]i accelerates activation and slows deactivation.

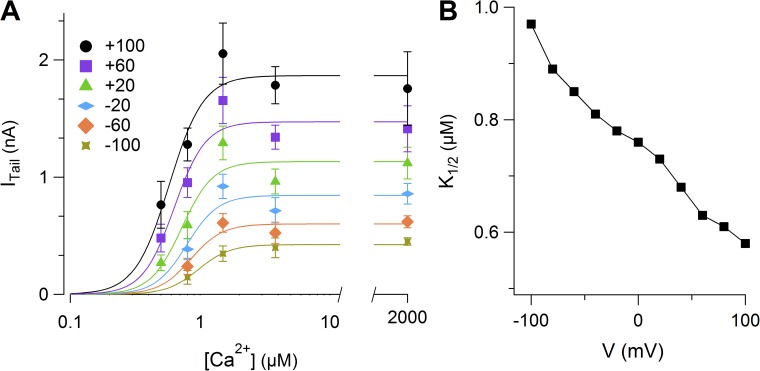

To analyze the Ca2+ dependence of current activation, we measured dose–response relations by calculating instantaneous tail currents at −100 mV after prepulses ranging from −100 to 100 mV with a duration between 200 and 800 ms (Fig. 3 A). The average instantaneous tail currents were plotted versus [Ca2+]i and fit at each voltage by the Hill equation:

Figure 3.

Ca2+ sensitivity. (A) Average instantaneous tail currents measured at −100 mV after a prepulse varying from −100 to 100 mV plotted versus [Ca2+]i (n = 4–8). The continuous lines are the fit with the Hill equation (Eq. 1). (B) K1/2 values plotted versus the prepulse voltage. Data in A are represented as mean ± SEM.

| (1) |

where I is the current, Imax is the maximal current, K1/2 is the [Ca2+]i producing 50% of Imax, and nH is the Hill coefficient.

Fig. 3 B shows that K1/2 decreased with membrane depolarization from 0.97 µM at −100 mV to 0.58 µM at 100 mV. The Hill coefficient was not voltage dependent with a value ranging between 3 and 4. These results show that Ca2+ sensitivity is slightly voltage dependent and that binding of more than 3 Ca2+ ions is necessary to open the channel. It should be noted, however, that the current amplitudes at high Ca2+ concentrations were sometimes smaller than those at 1.5 µM Ca2+ (Fig. 3 A), and that this current decrease may have slightly affected the estimation of nH and K1/2. A decline of currents at high Ca2+ concentrations has been described previously in some native Ca2+-activated Cl− currents (Kuruma and Hartzell, 2000; Qu et al., 2003), as well as in some splice variants of TMEM16A (Ferrera et al., 2009; Yang et al., 2014).

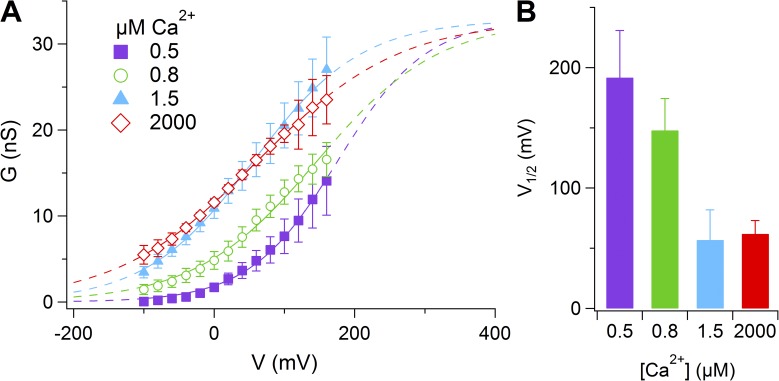

To estimate the voltage dependence of channel activation (G-V relation), we increased the amplitude of voltage steps to 160 mV and calculated instantaneous tail currents at −100 mV. G-V relations were fit by the Boltzmann equation:

| (2) |

where G is the conductance, Gmax is the maximal conductance, z is the equivalent gating charge associated with voltage-dependent channel opening, V is the membrane potential, V1/2 is the membrane potential producing 50% of Gmax, F is the Faraday constant, R is the gas constant, and T is the absolute temperature.

Fig. 4 A shows the average G-V relations at the indicated [Ca2+]i. Continuous lines were obtained from a global fit of the average G-V relations with the same Gmax. The average V1/2 was 197 ± 39 mV (n = 4) at 0.5 µM Ca2+ and became 70 ± 25 mV (n = 6) at 1.5 µM Ca2+ (Fig. 4 B), whereas the equivalent gating charge was not largely modified (z = 0.39 and 0.34, respectively).

Figure 4.

Voltage dependence of Ca2+-activated currents. (A) Average conductances at the indicated [Ca2+]i measured from instantaneous tail currents at −100 mV after prepulses from −100 to 160 mV plotted versus the prepulse voltage (n = 4–8). The continuous lines are the fit with the Boltzmann equation (Eq. 2). (B) Average V1/2 values plotted versus [Ca2+]i (n = 4–8). Data are represented as mean ± SEM.

These results show that an increase in [Ca2+]i caused a leftward shift of the G-V relation. Thus, the conductance depends both on [Ca2+]i and voltage, and depolarization can activate more channels as [Ca2+]i is increased.

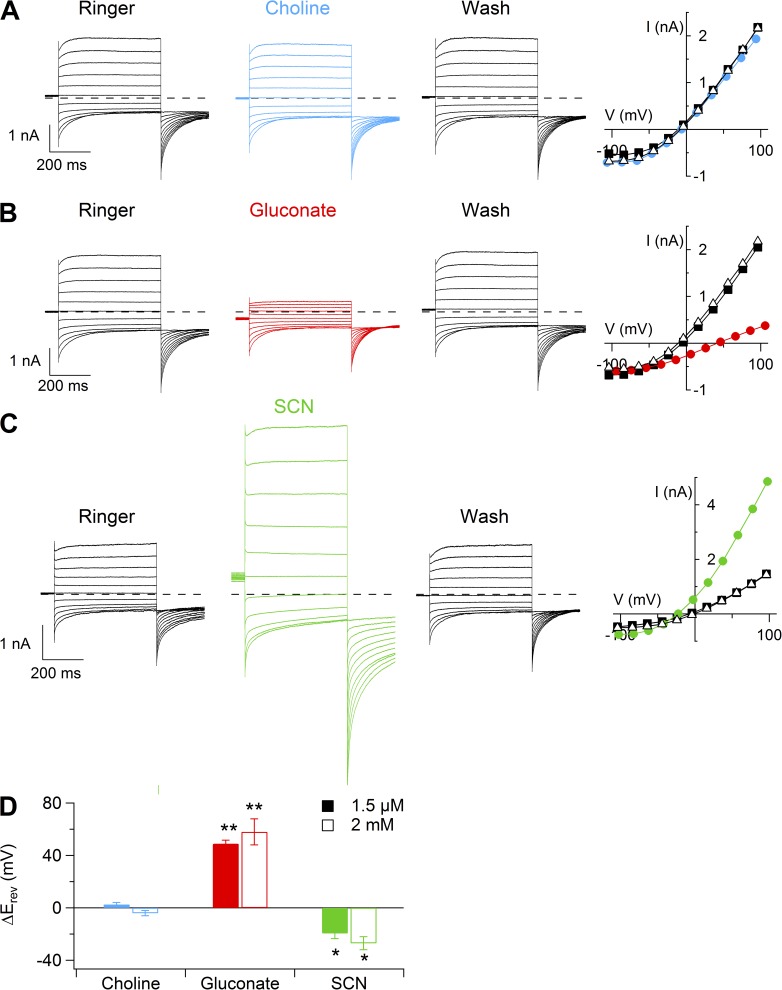

To investigate if the Ca2+-activated currents are caused by cation channels, we first substituted Na+ in the Ringer’s solution with choline, as this large organic cation is usually impermeant in cation channels (Hille, 2001). Fig. 5 A shows representative recordings at 1.5 µM Ca2+ in the presence of NaCl, after replacement of Na+ with choline, and in NaCl after washout. Steady-state I-V relations plotted in Fig. 5 B show that the replacement of Na+ with choline did not modify the I-V relation. Similar results were obtained with 2 mM Ca2+. The average reversal potential in choline-Cl was −10 ± 4 mV (n = 5), not significantly different from the value of −7 ± 2 mV (n = 5) measured in NaCl. The average shift of reversal potential in choline-Cl with respect to NaCl was not significantly different in 1.5 µM or 2 mM Ca2+ (Fig. 5 D), indicating that the Ca2+-activated current at both Ca2+ concentrations was not a cation current.

Figure 5.

Ionic selectivity of Ca2+-activated currents. Representative whole-cell recordings obtained with an intracellular solution containing 1.5 µM Ca2+. Voltage protocol as in Fig. 1 A. Each neuron was exposed to a Ringer’s solution containing NaCl, choline-Cl (A), Na-gluconate (B), or NaSCN (C), followed by washout in Ringer’s solution with NaCl. Dashed lines indicate zero current. Steady-state I-V relationships measured at the end of the voltage steps are shown at the right of each set of recordings. (D) Average reversal potential shift upon substitution of extracellular NaCl with choline-Cl, Na-gluconate, or NaSCN in 1.5 µM (closed bars; n = 5–10) or 2 mM Ca2+ (open bars; n = 4). Data in D are represented as mean ± SEM (**, P < 0.01; *, P < 0.05; Wilcoxon Signed Rank test).

Anion selectivity was then tested by replacing 140 mM NaCl with equimolar amounts of Na-gluconate or NaSCN (Fig. 5, C and E). When Cl− was replaced with gluconate in the presence of 1.5 µM Ca2+, we measured an average shift of Vrev of 49 ± 3 mV (n = 10), whereas in the presence of SCN− the Vrev shift was −20 ± 3 mV (n = 8). Similar values were obtained in the presence of 2 mM Ca2+ (Fig. 5 D). The average permeability ratios for anions (PX/PCl) were: SCN− (2.6) > Cl− (1.0) > gluconate (0.1).

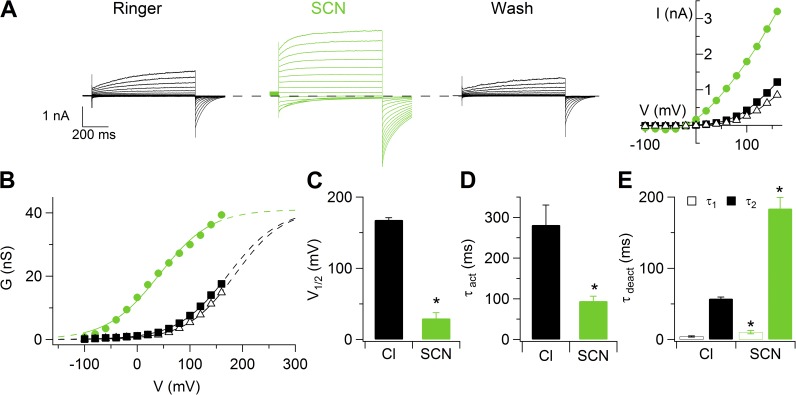

We investigated whether the more permeant anion SCN− modifies the voltage dependence of channel activation and the gating kinetics, as observed in several native Ca2+-activated Cl− currents (Greenwood and Large, 1999; Perez-Cornejo et al., 2004), as well as in heterologously expressed TMEM16A and TMEM16B (Xiao et al., 2011; Betto et al., 2014). Fig. 6 (A and B) shows recordings and I-V relations from a vomeronasal neuron in the presence of 0.5 µM Ca2+ when NaCl was replaced with NaSCN. The G-V relation was shifted toward more negative potentials when Cl− was substituted with SCN− (Fig. 6 C). The average V1/2 from several neurons significantly changed from 168 ± 6 mV in Cl− to 39 ± 14 mV in SCN− (n = 3). Moreover, τact in the presence of 0.5 µM Ca2+ became significantly faster in SCN−, with an average value at 100 mV of 94 ± 12 ms (n = 3), compared with 282 ± 49 ms (n = 3) in Cl− (Fig. 6 E). Also, the deactivation time constants, measured as in Fig. 2 D, were significantly modified upon anion substitution (Fig. 6 F), with average values of τdeact1 = 4.2 ± 0.9 ms and τdeact2 = 57 ± 2 ms (n = 3) in SCN−, slower than the values in Cl− measured in the same neurons: τdeact1 = 10 ± 2 ms and τdeact2 = 183 ± 16 ms (n = 3).

Figure 6.

Change of voltage dependence in the presence of SCN−. (A) Representative whole-cell recordings obtained with an intracellular solution containing 0.5 µM Ca2+. The same neuron was exposed to a Ringer’s solution containing NaCl or NaSCN, followed by washout in Ringer’s solution with NaCl. Voltage steps of 800-ms duration were given from a holding voltage of 0 mV to voltages between −100 and 160 mV in 20-mV steps, followed by a step to −100 mV. Dashed lines indicate zero current. Steady-state I-V relationships measured at the end of the voltage steps. (B) Conductances measured from instantaneous tail currents at −100 mV after prepulses from −100 to 160 mV plotted versus the prepulse voltage. Data from the recordings shown in A. (C) Average V1/2 in Cl− or SCN− (n = 3). (D and E) Average activation and deactivation time constants in Cl− or SCN− (n = 3). Data in C–E are represented as mean ± SEM (*, P < 0.05; Wilcoxon Signed Rank test).

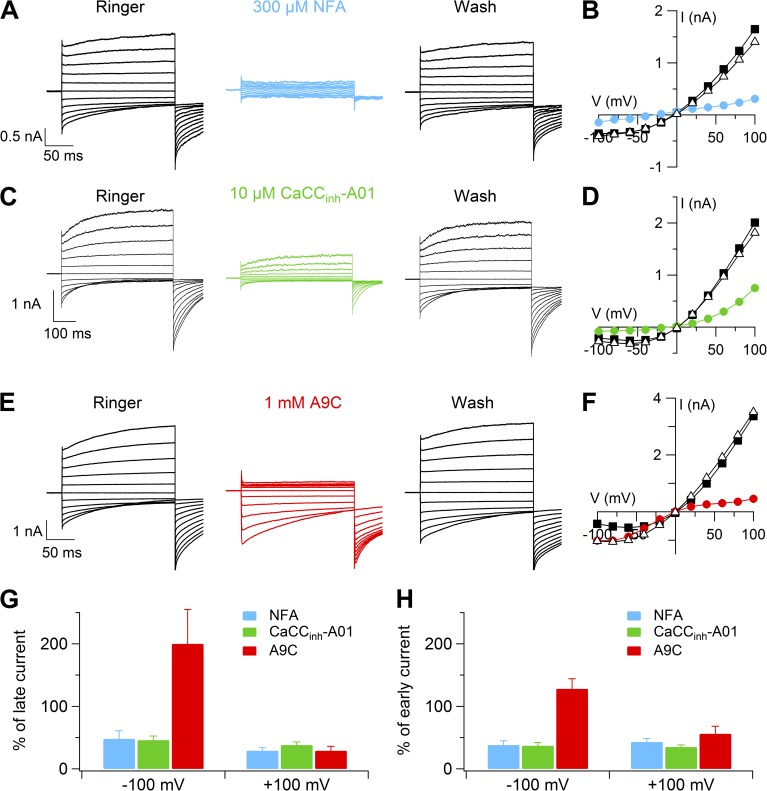

To assess the pharmacological profile of Ca2+-activated Cl− currents in vomeronasal sensory neurons, we measured the extracellular blockage properties of 300 µM NFA, 10 µM CaCCinh-A01, and 1 mM A9C, commonly used blockers of Ca2+-activated Cl− currents (De La Fuente et al., 2008; Hartzell et al., 2009; Huang et al., 2012). Fig. 7 shows that all three compounds induced a reversible block of the outward currents activated by 1.5 µM Ca2+, whereas inward currents were blocked only by NFA and CaCCinh-A01. The percentage of current in the presence of each compound relative to control was measured both at 2 ms after the voltage step (early current) and at the end of the voltage step (late current), as shown in Fig. 7 (G and H). At 100 mV, the percentage of late currents was 29 ± 5 for NFA, 38 ± 5 for CaCCinh-A01, and 29 ± 7 for A9C (Fig. 7 G; n = 5–7), and similar values were obtained by measuring the early currents (Fig. 7 H). At −100 mV, both NFA and CaCCinh-A01 partially blocked the inward late currents with the following percentages: 48 ± 13 for NFA and 46 ± 7 for CaCCinh-A01 (Fig. 7 G). These values were not significantly different when measured as early currents (Fig. 7 H). On the contrary, A9C did not significantly affect the inward early current at −100 mV but greatly potentiated the inward late current with a percentage of 200 ± 55 (Fig. 7, G and H).

Figure 7.

Pharmacology of Ca2+-activated currents. Representative whole-cell recordings obtained with an intracellular solution containing 1.5 µM Ca2+. Voltage protocol as in Fig. 1 A. Each neuron was exposed to a Ringer’s solution to 300 µM NFA (A), 10 µM CaCCihn-A01 (C), or 1 mM A9C (E), and again to Ringer’s solution. (B, D, and F) I-V relationships measured at the end of the voltage steps from the recordings shown on the left. (G and H) Average percentages of currents measured in the presence of each compound relative to control at the end of the voltage step (G; late current) or 2 ms after the voltage step (H; early current) at −100 or 100 mV (n = 5–7). Data in G and H are represented as mean ± SEM.

These results show that, in the presence of 1.5 µM Ca2+, 300 µM NFA and 10 µM CaCCinh-A01 produced similar current inhibitions at 100 and −100 mV both for early and late currents. 1 mM A9C had an anomalous effect, blocking the current at 100 mV and largely potentiating late currents at −100 mV.

Collectively, these results show that the Ca2+-activated currents measured in vomeronasal sensory neurons are mainly anion currents.

TMEM16A and TMEM16B are coexpressed in microvilli of vomeronasal sensory neurons (Dibattista et al., 2012), and their individual heterologous expression shows some similar electrophysiological properties—indeed, they cannot be distinguished by their ionic selectivity (Adomaviciene et al., 2013) or by their pharmacological profile (Pifferi et al., 2009a; Bradley et al., 2014)—as well as some important differences: TMEM16A have a higher Ca2+ sensitivity and slower activation kinetics than TMEM16B (Caputo et al., 2008; Schroeder et al., 2008; Yang et al., 2008; Pifferi et al., 2009a; Stephan et al., 2009; Ferrera et al., 2011: Cenedese et al., 2012; Pedemonte and Galietta, 2014). We found that whole-cell properties of Ca2+-activated Cl− currents in vomeronasal neurons are more similar to those of heterologous TMEM16A than TMEM16B.

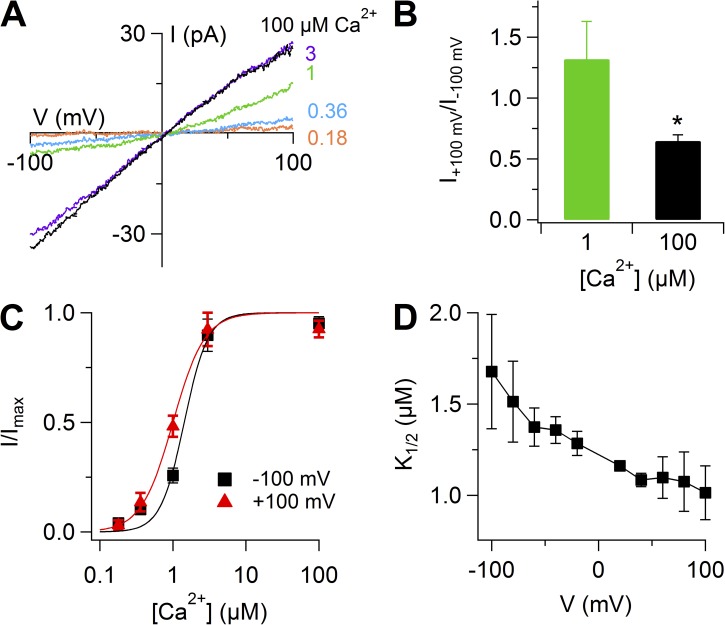

Ca2+-activated Cl− currents in inside-out excised patches from dendritic knob/microvilli of mouse vomeronasal sensory neurons

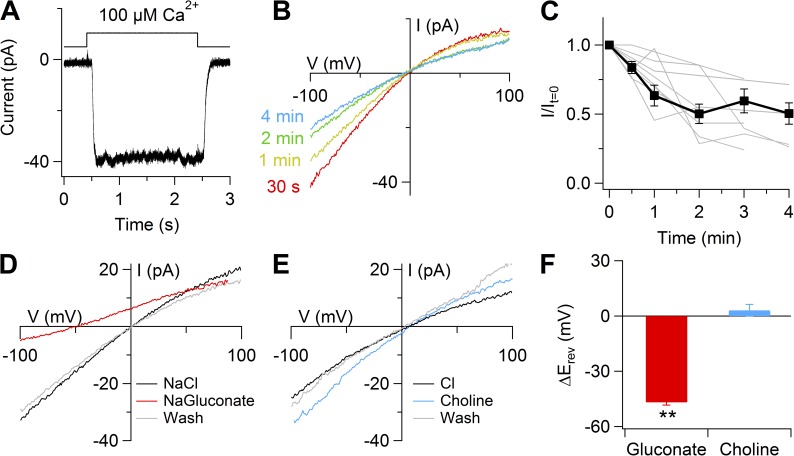

To further characterize Ca2+-activated currents, we excised membrane patches in the inside-out configuration from dendritic knobs of vomeronasal neurons. Membrane patches were excised from the tips of the knobs and are likely to contain membranes from both the dendritic knob and from microvilli. Fig. 8 A shows the change of current at −50 mV when an inside-out patch was exposed to 100 µM Ca2+ for 2 s. Upon the application of 100 µM Ca2+, the current rapidly reached a value of about −40 pA and remained stationary in the presence of Ca2+, whereas it rapidly returned to the baseline value when Ca2+ was removed. The average current from several patches at −50 mV was −16 ± 5 pA (range of −6 to −40 pA; n = 7), and the average ratio between the current measured 2 s after Ca2+ application and the current measured shortly after Ca2+ application was 0.96 ± 0.02 (n = 7).

Figure 8.

Rundown and ionic selectivity of Ca2+-activated currents in inside-out patches from dendritic knob/microvilli of vomeronasal sensory neurons. (A) An inside-out patch was exposed to 100 µM Ca2+ for 2 s at the time indicated in the upper trace. Holding potential, −50 mV. Symmetrical NaCl solutions. (B) I-V relations from a voltage ramp protocol. Leakage currents measured in 0 Ca2+ were subtracted. The number next to each trace indicates the time of Ca2+ application after patch excision. (C) Average ratios between currents at −100 mV measured at the indicated times after patch excision and the current measured at patch excision (n = 3–10). Ratios of individual patches are in gray. (D and E) I-V relations activated by 100 µM Ca2+ from a voltage ramp protocol after subtraction of the leakage currents measured in 0 Ca2+. The patch was exposed to bath solutions containing 140 mM NaCl, Na-gluconate (D), or choline-Cl (E), followed by washout with NaCl. Current traces in D and E were from the same patch. (F) Average reversal potential shift upon substitution of extracellular NaCl with Na-gluconate or choline-Cl (n = 3) (**, P < 0.01; Wilcoxon Signed Rank test). Error bars indicate SEM.

Fig. 8 B shows that the amplitude of Ca2+-activated currents in inside-out patches decreased with time after patch excision. A similar current rundown has also been observed in other native Ca2+-activated Cl− currents, as well as in heterologous TMEM16A and TMEM16B currents (Kuruma and Hartzell, 2000; Qu and Hartzell, 2000; Reisert et al., 2003; Pifferi et al., 2009a,b; Stephan et al., 2009; Yu et al., 2014). Currents underwent an irreversible reduction until they reached an almost steady-state value (Fig. 8, B and C).

To determine the ion selectivity of the Ca2+-activated current, we replaced NaCl in the bathing solution with Na-gluconate or with choline-Cl and measured the shift of reversal potential (Fig. 8, D–F). Currents were activated by 100 µM Ca2+, and voltage ramps from −100 to 100 mV were applied. When Cl− was replaced with gluconate, we measured an average shift of Vrev of −47 ± 2 mV (n = 3), whereas in the presence of choline-Cl, the shift of Vrev was 3 ± 3 mV (n = 3). Thus, replacement of Cl− with gluconate shifted the reversal potential from near zero in symmetrical Cl− to more negative values, as expected for Cl−-selective channels in our experimental conditions, showing that Ca2+-activated currents were Cl− selective.

To measure dose–response relations, we activated currents in excised inside-out patches with various Ca2+ concentration and measured current amplitudes after the rapid phase of rundown, when the current reached an almost steady-state value (Fig. 9, A–D). Fig. 9 C shows that K1/2 decreased with membrane depolarization from 1.5 ± 0.2 µM at −100 mV to 1.1 ± 0.1 µM (n = 5) at 100 mV. The Hill coefficient was not voltage dependent with a value ranging between 2.4 and 3.2. The average ratio between currents at 100 and −100 mV was 1.3 ± 0.3 at 1 µM (n = 5) and 0.65 ± 0.05 at 100 µM (n = 13).

Figure 9.

Dose–response relations of Ca2+-activated currents in inside-out patches from the dendritic knob/microvilli of vomeronasal sensory neurons. (A) I-V relations from the same patch exposed to the indicated Ca2+ concentrations after subtraction of the currents measured in 0 Ca2+. (B) Ratios between currents measured at 100 and at −100 mV at the indicated Ca2+ concentrations (n = 5–13). *, P < 0.05; Wilcoxon Signed Rank test. (C) Dose–response relations, obtained by normalized currents at −100 or 100 mV (n = 5). Continuous lines are the fit with the Hill equation (Eq. 1). (D) Mean K1/2 values plotted versus voltage (n = 5). Error bars indicate SEM.

Collectively, these results demonstrate the presence of Ca2+-activated Cl− currents in the knob/microvilli of mouse vomeronasal sensory neurons. Moreover, the range of Ca2+ sensitivity and the absence of inactivation in the presence of a constant Ca2+ concentration indicate that properties of native currents are more similar to those of TMEM16A than TMEM16B (see also Discussion). Indeed, all isoforms of TMEM16B have been shown to inactivate in the continuous presence of Ca2+ at negative potentials (Pifferi et al., 2009a; Stephan et al., 2009; Ponissery Saidu et al., 2013), whereas TMEM16A current did not inactivate (Ni et al., 2014; Tien et al., 2014; Yu et al., 2014).

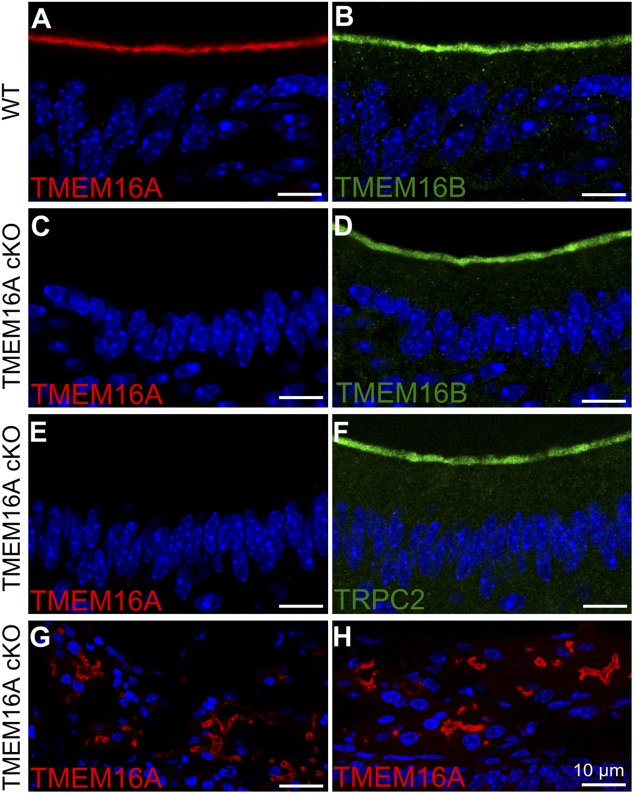

Conditional knockout of TMEM16A in vomeronasal sensory neurons

We have shown previously that TMEM16A and TMEM16B are coexpressed in microvilli of mouse vomeronasal sensory neurons (Dibattista et al., 2012), and we showed here that Ca2+-activated Cl− currents in vomeronasal sensory neurons are more similar to heterologous TMEM16A than TMEM16B. As the constitutive TMEM16A knockout is lethal soon after birth (Rock et al., 2008), we selectively abolished expression of TMEM16A in mature vomeronasal sensory neurons by crossing floxed TMEM16Afl/fl mice (Faria et al., 2014; Schreiber et al., 2014) with OMP-Cre mice (Li et al., 2004).

By immunohistochemistry, we confirmed our previous results that TMEM16A and TMEM16B are expressed at the apical surface of the vomeronasal epithelium of control WT mice (Fig. 10, A and B), whereas we showed that TMEM16A immunoreactivity was absent in TMEM16A cKO mice (Fig. 10 C). Furthermore, we investigated by immunohistochemistry if the lack of TMEM16A affected the expression of TMEM16B and TRPC2, and found a normal pattern of expression for the two proteins (Fig. 10, D and F). In addition, we verified the specificity of Tmem16A ablation, by checking TMEM16A expression in lateral nasal glands and septal nasal glands, which do not express OMP and should therefore express TMEM16A. Indeed, Fig. 10 (G and H) shows expression of TMEM16A in the nasal glands of TMEM16A cKO mice.

Figure 10.

Immunostaining of sections of VNO in WT and TMEM16A cKO mice. (A and B) Confocal micrographs showing TMEM16A (red) and TMEM16B (green) expression at the apical surface of the vomeronasal epithelium in WT mice. (C–F) No immunoreactivity to TMEM16A was detectable at the apical surface of the vomeronasal epithelium in TMEM16A cKO mice, whereas TMEM16B and TRPC2 were normally detected. (G and H) As a control, expression of TMEM16A is shown in nasal septal glands (G) and lateral nasal glands (H) of cKO mice. Cell nuclei were stained by DAPI (blue). Bars, 10 µm.

These results demonstrate that the loss of TMEM16A is restricted to vomeronasal sensory neurons of cKO mice and confirm the specificity of the antibody against this protein. Furthermore, TMEM16B and TRPC2 are expressed at the apical surface of the vomeronasal epithelium in cKO as in WT mice.

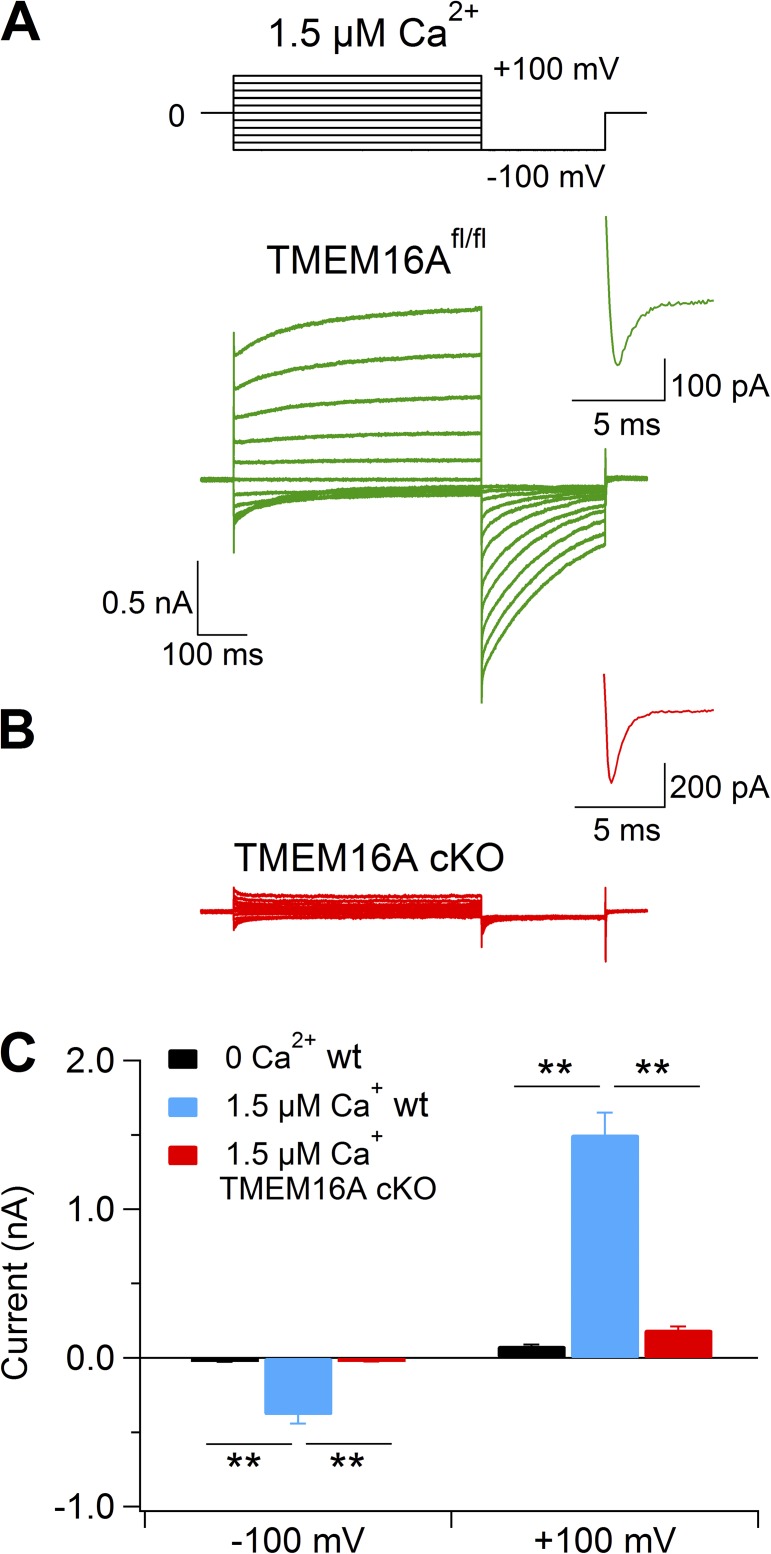

To determine the contribution of TMEM16A to Ca2+-activated Cl− currents in vomeronasal sensory neurons, we measured currents in isolated neurons from TMEM16A cKO mice in the whole-cell configuration with intracellular solutions containing various amounts of free [Ca2+]i. Fig. 11 (A and B) shows the comparison between representative recordings from TMEM16Afl/fl and TMEM16A cKO mice. Currents were activated by voltage steps between −100 and 100 mV from a holding potential of 0 mV, followed by a step to −100 mV and return to 0 mV. The last part of the current trace elicited by the depolarizing voltage from −100 to 0 mV was used as a control of the viability of neurons, as it allowed the measurement of voltage-gated inward currents (likely Na+ currents; insets of Fig. 11, A and B). The kinetics of currents activated by 1.5 µM Ca2+ in neurons from TMEM16Afl/fl mice resembled those measured in control WT mice (Figs. 11 A and 1 A), whereas currents in vomeronasal neurons from TMEM16A cKO mice were not significantly different from currents in the absence of Ca2+ (Figs. 11, B and C, and 1 A). The inset of Fig. 11 B shows a representative voltage-gated current (elicited by a 0-mV step from −100 mV), indicating that the neuron was viable but did not have currents activated by Ca2+. All together, we tested 40 viable neurons from 6 TMEM16A cKO mice at [Ca2+]i varying from 0.5 µM to 2 mM Ca2+ and did not find a significant difference from currents measured in 0 Ca2+. Furthermore, we measured currents in inside-out patches from dendritic knobs of vomeronasal neurons from TMEM16A cKO mice and did not find any measurable Ca2+-activated current (not depicted).

Figure 11.

Lack of Ca2+-activated currents in vomeronasal sensory neurons from TMEM16A conditional knockout mice. Representative whole-cell recordings obtained with an intracellular solution containing 1.5 µM Ca2+ from vomeronasal sensory neurons dissociated from TMEM16Afl/fl (A) or TMEM16A cKO (B) mice. Insets show the enlargement of the recordings of voltage-gated inward currents activated by a step to 0 mV from the holding potential of −100 mV, as indicated in the voltage protocol at the top of the figure. (C) Mean current amplitudes measured at −100 or 100 mV with intracellular pipette solution containing nominally 0 (black bar; n = 6) or 1.5 µM free Ca2+ from WT (blue bar; n = 28) or TMEM16A cKO mice (red bar; n = 20). Error bars indicate SEM (**, P < 0.01; Dunn–Hollander–Wolfe test after Krustal–Wallis analysis).

These results demonstrate that TMEM16A is a necessary component of the Ca2+-activated Cl− current in vomeronasal sensory neurons.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we have provided the first functional characterization of Ca2+-activated Cl− currents in isolated mouse vomeronasal sensory neurons both in whole-cell and in inside-out patches from the knobs/microvilli. A comparison among biophysical properties indicates that native currents are more similar to heterologous TMEM16A than to TMEM16B Ca2+-activated Cl− currents. Furthermore, conditional knockout of TMEM16A abolished Ca2+-activated currents in mouse vomeronasal neurons, demonstrating that TMEM16A is a necessary component of Ca2+-activated Cl− currents in these neurons.

Ca2+-activated currents

In whole-cell recordings, we measured Ca2+-activated currents in 70% of the neurons (124/178), whereas we did not record any Ca2+-activated current in the remaining neurons (30%; 54/178), although these neurons were considered viable, as they had transient voltage-gated inward currents (likely Na+ currents). These currents were recorded with intracellular Cs+ or Na+ instead of K+, i.e., under ionic conditions that prevented permeation through Ca2+-activated K+ channels. The absence of Ca2+-activated currents in some neurons could simply be caused by inactivation or rundown of Ca2+-activated channels, or to damage of the microvilli, where these channels should be mostly expressed (as it will be discussed later), but it also raises the question of whether a Ca2+-activated current is present only in a subset of vomeronasal neurons. Indeed, the mouse vomeronasal epithelium contains two major populations of neurons, basal and apical, based on their location and on the expression of different receptors and proteins (Berghard and Buck, 1996; Jia and Halpern, 1996; Lau and Cherry, 2000; Martini et al., 2001; Leinders-Zufall et al., 2004; Liberles et al., 2009; Rivière et al., 2009). Apical neurons express receptors of the V1R or FPR families, the G protein α subunit Gαi2, and phosphodiesterase 4A, whereas basal neurons express receptors of the V2R or FPR families and the G protein α subunit Gαo. We have previously investigated by immunocytochemistry the percentage of apical and basal neurons obtained in our dissociated preparations using anti–phosphodiesterase 4A antibody as a marker for apical neurons, or anti-Gαo antibody as a marker for basal neurons, and found that on average, ∼74% of the dissociated neurons were apical (Celsi et al., 2012). Based on these results, it is very likely that most of our electrophysiological recordings were obtained from apical neurons, and it is possible to speculate that the 30% of neurons without Ca2+-activated current could be basal neurons. However, in the dissociated preparations used for electrophysiological recordings, we could not determine by visual inspection whether a neuron was apical or basal, nor we could perform immunocytochemistry after the recordings, as neurons were often lost after pipette retrieval. It is important to note that TMEM16A and TMEM16B are coexpressed both in apical and basal neurons (Dibattista et al., 2012). Thus, we favor the interpretation that all neurons have Ca2+-activated currents and that the absence of these currents in some neurons was likely caused by channel inactivation or rundown or to damage of the microvilli, although we cannot exclude the possibility that Ca2+-activated currents are present only in a subset of vomeronasal neurons.

Cationic and anionic Ca2+-activated currents

Previous studies on vomeronasal sensory neurons have reported the presence of Ca2+-activated currents, in the absence of intracellular K+, with different ionic selectivity: nonselective cation currents or anion currents.

Ca2+-activated nonselective cation currents have been recorded in the hamster (Liman, 2003) and in the mouse (Spehr et al., 2009), although they showed different Ca2+ sensitivities. In the hamster, whole-cell dialysis with 0.5–2 mM Ca2+ produced currents with an average amplitude of −177 pA at −80 mV, and half-activation of this current required a high Ca2+ concentration of 0.5 mM at −80 mV (Liman, 2003). In the mouse, nonselective cation currents were recorded in inside-out patches only in a subpopulation of neurons (12.5%) in the presence of 50 µM Ca2+ (Spehr et al., 2009). In a previous study by our group (Dibattista et al., 2012), we used photolysis of caged Ca2+ to increase Ca2+ concentration in the apical region (dendritic knob and microvilli) of mouse vomeronasal neurons, and we did not detect any cation current, but we measured Ca2+-activated Cl− currents with an average amplitude of −261 pA at −50 mV. In that study, we pointed out that the highest Ca2+ concentration obtained from photolysis of caged Ca2+ was probably ∼10–20 µM, lower than the values used to activate the nonselective cation currents in the previous studies (Liman, 2003; Spehr et al., 2009), and that perhaps a higher Ca2+ concentration could activate nonselective cation currents. However, in the present study, we dialyzed neurons also using high Ca2+ concentrations in the pipette, reaching 2 mM, and did not record any cation current. Indeed, the substitution of extracellular NaCl with choline-Cl did not cause a significant shift in the reversal potential both with 1.5 µM and 2 mM of intracellular Ca2+, whereas the substitution of NaCl with Na-gluconate caused a shift in the reversal potential, as expected for Cl− currents. The substitution of extracellular Cl− with SCN− showed that this anion is more permeant than Cl− and also altered the voltage dependence of the Ca2+-activated current, a common characteristic of Ca2+-activated Cl− channels (Perez-Cornejo et al., 2004; Xiao et al., 2011; Betto et al., 2014). Moreover, the typical Cl− blockers NFA and CaCCinh-A01 caused a reversible inhibition of the current. A9C had an anomalous effect, causing a current decrease at positive voltages and a current increase at negative voltages, consistent with previous results observed in Ca2+-activated Cl− channels in smooth muscle cells (Piper and Greenwood, 2003; Cherian et al., 2015).

Furthermore, we performed inside-out recordings from the knobs/microvilli of mouse vomeronasal neurons and demonstrated the presence of Ca2+-activated Cl− channels with electrophysiological properties similar to those of TMEM16A. We therefore suggest that the nonselective cation current measured in vomeronasal neurons from the hamster may be species specific. In the mouse, results obtained in 12.5% of inside-out patches from Spehr et al. (2009) could indicate that the presence of Ca2+-activated nonselective cation channels is restricted to a very small subpopulation of vomeronasal neurons that was not present in our experiments.

Other studies have also reported evidence for Ca2+-activated Cl− currents in mouse vomeronasal sensory neurons. Yang and Delay (2010) used perforated patch recording on dissociated neurons and reported that the urine-activated current was partially blocked by some Cl− channel blockers (NFA and DIDS), and was reduced by removing extracellular Ca2+ or by blocking intracellular Cl− accumulation mediated by the NKCC1 cotransporter. Similar results were also obtained by Kim et al. (2011) using VNO slice preparations. At present, the source of intracellular Ca2+ increase is still unclear, as Yang and Delay (2010) showed that Ca2+ influx is necessary to activate a Cl− current, whereas Kim et al. (2011) suggested that Cl− currents could also be activated by Ca2+ release from internal store mediated by IP3 in a TRPC2-independent manner. The presence of Ca2+-activated Cl− component in urine response indicates that these channels could play a role in vomeronasal transduction. However, at present, the Cl− equilibrium potential in vomeronasal neurons in physiological conditions is unknown, preventing the possibility to determine if Ca2+-activated Cl− currents contribute to depolarization or hyperpolarization.

TMEM16A is a necessary component of the Ca2+-activated Cl− currents in mouse vomeronasal sensory neurons

Both the results of our whole-cell and inside-out experiments from mouse vomeronasal neurons showed the presence of Ca2+-activated Cl− currents with electrophysiological properties more similar to those of heterologous TMEM16A than TMEM16B currents. It is important to note that splice variants have been identified both for TMEM16A (Caputo et al., 2008; Ferrera et al., 2009, 2011) and for TMEM16B (Stephan et al., 2009; Ponissery Saidu et al., 2013), and it has been shown that some functional channel properties such as Ca2+ sensitivity and time and voltage dependence differ among the various isoforms of each protein (Ferrera et al., 2010; Huang et al., 2012; Pedemonte and Galietta, 2014).

In whole-cell recordings, we measured a kinetics of activation with a time constant of ∼235 ms at 100 mV in 0.5 µM Ca2+, rather similar to the value of ∼300 ms measured in the same conditions for the TMEM16A (abc) isoform (Scudieri et al., 2013), but very different from the fast kinetics, with time constants of activation <10 ms, measured in the retinal isoforms of TMEM16B (Cenedese et al., 2012; Adomaviciene et al., 2013; Scudieri et al., 2013; Betto et al., 2014). However, time constants of activation for the olfactory isoforms of TMEM16B have not been estimated yet, and visual inspection of a whole-cell recording of the recently identified olfactory isoform B (Fig. 4 A of Ponissery Saidu et al., 2013) indicates that the kinetics could be slower than in the retinal isoforms.

In inside-out recordings, a comparison of dose–response relations shows that the Ca2+ concentration necessary for 50% activation of the maximal current at 60 or 70 mV had a value of 1.1 µM in our experiments, more similar to the value of 1.3 µM for TMEM16A (Adomaviciene et al., 2013) than to the value of 1.8–4 µM for TMEM16B (Pifferi et al., 2009a, 2012; Adomaviciene et al., 2013). Moreover, at the holding potential of −50 mV and in the presence of 100 µM Ca2+, we did not measure a time-dependent decrease in the presence of Ca2+, typical of all TMEM16B isoforms (Pifferi et al., 2009a, 2012; Stephan et al., 2009; Ponissery Saidu et al., 2013), but we observed a stationary current similar to the behavior of TMEM16A currents in inside-out patches (Ni et al., 2014; Tien et al., 2014; Yu et al., 2014).

To investigate the contribution of TMEM16A to Ca2+-activated Cl− currents in vomeronasal neurons, we obtained TMEM16A cKO mice and surprisingly found that Ca2+-activated currents were abolished, demonstrating that TMEM16A is an essential component of Ca2+-activated Cl− currents in mouse vomeronasal sensory neurons. Immunohistochemistry showed the presence of TMEM16B at the apical surface of the vomeronasal epithelium TMEM16A cKO mice, indicating that the expression of TMEM16B does not depend on TMEM16A. At present, we do not know which splice variants are expressed in vomeronasal neurons, but Ponissery Saidu et al. (2013) showed that neurons of the main olfactory epithelium also express isoforms lacking the exon 4 sequence (named isoforms AΔ4 or BΔ4), which do not form functional channels by themselves but modulate channel properties of main olfactory isoforms (named A and B) when they are coexpressed. It is therefore tempting to speculate that vomeronasal neurons may express TMEM16B isoforms that do not form functional channels but could modulate the activity of TMEM16A. Previous results showed that TMEM16A coimmunoprecipitated with TMEM16B in heterologous systems, suggesting that these two proteins may form heteromers (Tien et al., 2014). Thus, native vomeronasal Ca2+-activated Cl− channels may be heteromers composed of two or more TMEM16A and TMEM16B isoforms. Moreover, our results show that TMEM16A is necessary to have functional channels in the VNO, whereas VNO TMEM16B isoforms may not form functional channels by themselves but could be modulatory subunits of heteromeric channels.

However, in a previous study, Billig et al. (2011) compared whole-cell recordings in vomeronasal sensory neurons from WT (n = 7) or knockout mice for TMEM16B (Ano2−/−; n = 6) in the presence of 1.5 µM Ca2+ or 0 Ca2+ in the pipette, and reported that: “Currents of most Ano2−/− VSNs were indistinguishable from those we observed without Ca2+ (Fig. 5n), but a few cells showed currents up to twofold larger. Averaged current/voltage curves revealed that Ca2+-activated Cl− currents of VSNs depend predominantly on Ano2 (Fig. 5l). Although Ano1 is expressed in the VNO (Fig. 3a), its contribution to VSN currents seems minor.” Thus, Billig et al. (2011) suggested that TMEM16B plays a prominent role in Ca2+-activated currents in vomeronasal neurons. However, as the specific VNO TMEM16A and TMEM16B isoforms are presently unknown, there is an alternative possible explanation for the results observed by Billig et al. (2011); vomeronasal neurons may express one or more TMEM16A isoforms that do not form functional channels by themselves but may form functional heteromeric channels when coexpressed with specific TMEM16B isoforms.

Collectively, our data and those from Billig et al. (2011) raise the possibility that only heteromeric channels composed by the VNO-specific isoforms TMEM16A and TMEM16B are functional in vomeronasal neurons. In addition, we cannot exclude the possibility that different populations of neurons may express different isoforms at various levels, and that the two studies investigated different populations of vomeronasal neurons. Future experiments will have to identify the specific VNO isoforms and unravel their interactions.

Acknowledgments

We thank Peter Mombaerts (Max Planck Institute of Biophysics, Frankfurt, Germany) for providing OMP-Cre mice. We also thank Claudia Gargini (University of Pisa, Italy) for useful discussions, Gianluca Pietra for help with the production of cKO mice, and all members of the laboratory for discussions.

This study was supported by grants from the Italian Ministry of Education, University and Research (2010599KBR to A. Menini) and from the Fondazione Compagnia di San Paolo, Torino (2013.0922 to A. Boccaccio). S. Pifferi is a recipient of an EU Marie Curie Reintegration Grant (OLF-STOM n.334404).

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Angus C. Nairn served as editor.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used in this paper:

- A9C

- anthracene-9-carboxylic acid

- FPR

- formyl peptide receptor

- NFA

- niflumic acid

- OMP

- olfactory marker protein

- TRPC2

- transient receptor potential canonical 2

- VNO

- vomeronasal organ

References

- Adomaviciene A., Smith K.J., Garnett H., and Tammaro P.. 2013. Putative pore-loops of TMEM16/anoctamin channels affect channel density in cell membranes. J. Physiol. 591:3487–3505 10.1113/jphysiol.2013.251660 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnson H.A., Fu X., and Holy T.E.. 2010. Multielectrode array recordings of the vomeronasal epithelium. J. Vis. Exp. 1:1845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry P.H.1994. JPCalc, a software package for calculating liquid junction potential corrections in patch-clamp, intracellular, epithelial and bilayer measurements and for correcting junction potential measurements. J. Neurosci. Methods. 51:107–116 10.1016/0165-0270(94)90031-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berghard A., and Buck L.B.. 1996. Sensory transduction in vomeronasal neurons: Evidence for Gαo, Gαi2, and adenylyl cyclase II as major components of a pheromone signaling cascade. J. Neurosci. 16:909–918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betto G., Cherian O.L., Pifferi S., Cenedese V., Boccaccio A., and Menini A.. 2014. Interactions between permeation and gating in the TMEM16B/anoctamin2 calcium-activated chloride channel. J. Gen. Physiol. 143:703–718 10.1085/jgp.201411182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billig G.M., Pál B., Fidzinski P., and Jentsch T.J.. 2011. Ca2+-activated Cl− currents are dispensable for olfaction. Nat. Neurosci. 14:763–769 10.1038/nn.2821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley E., Fedigan S., Webb T., Hollywood M.A., Thornbury K.D., McHale N.G., and Sergeant G.P.. 2014. Pharmacological characterization of TMEM16A currents. Channels (Austin). 8:308–320 10.4161/chan.28065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan P.A.2009. Outstanding issues surrounding vomeronasal mechanisms of pregnancy block and individual recognition in mice. Behav. Brain Res. 200:287–294 10.1016/j.bbr.2008.10.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caputo A., Caci E., Ferrera L., Pedemonte N., Barsanti C., Sondo E., Pfeffer U., Ravazzolo R., Zegarra-Moran O., and Galietta L.J.V.. 2008. TMEM16A, a membrane protein associated with calcium-dependent chloride channel activity. Science. 322:590–594 10.1126/science.1163518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celsi F., D’Errico A., and Menini A.. 2012. Responses to sulfated steroids of female mouse vomeronasal sensory neurons. Chem. Senses. 37:849–858 10.1093/chemse/bjs068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cenedese V., Betto G., Celsi F., Cherian O.L., Pifferi S., and Menini A.. 2012. The voltage dependence of the TMEM16B/anoctamin2 calcium-activated chloride channel is modified by mutations in the first putative intracellular loop. J. Gen. Physiol. 139:285–294 10.1085/jgp.201110764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamero P., Marton T.F., Logan D.W., Flanagan K., Cruz J.R., Saghatelian A., Cravatt B.F., and Stowers L.. 2007. Identification of protein pheromones that promote aggressive behaviour. Nature. 450:899–902 10.1038/nature05997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamero P., Katsoulidou V., Hendrix P., Bufe B., Roberts R., Matsunami H., Abramowitz J., Birnbaumer L., Zufall F., and Leinders-Zufall T.. 2011. G protein Gαo is essential for vomeronasal function and aggressive behavior in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 108:12898–12903 10.1073/pnas.1107770108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherian O.L., Menini A., and Boccaccio A.. 2015. Multiple effects of anthracene-9-carboxylic acid on the TMEM16B/anoctamin2 calcium-activated chloride channel. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1848:1005–1013 10.1016/j.bbamem.2015.01.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De La Fuente R., Namkung W., Mills A., and Verkman A.S.. 2008. Small-molecule screen identifies inhibitors of a human intestinal calcium-activated chloride channel. Mol. Pharmacol. 73:758–768 10.1124/mol.107.043208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean D.M., Mazzatenta A., and Menini A.. 2004. Voltage-activated current properties of male and female mouse vomeronasal sensory neurons: sexually dichotomous? J. Comp. Physiol. A Neuroethol. Sens. Neural Behav. Physiol. 190:491–499 10.1007/s00359-004-0513-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dibattista M., Mazzatenta A., Grassi F., Tirindelli R., and Menini A.. 2008. Hyperpolarization-activated cyclic nucleotide-gated channels in mouse vomeronasal sensory neurons. J. Neurophysiol. 100:576–586 10.1152/jn.90263.2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dibattista M., Amjad A., Maurya D.K., Sagheddu C., Montani G., Tirindelli R., and Menini A.. 2012. Calcium-activated chloride channels in the apical region of mouse vomeronasal sensory neurons. J. Gen. Physiol. 140:3–15 10.1085/jgp.201210780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dulac C., and Axel R.. 1995. A novel family of genes encoding putative pheromone receptors in mammals. Cell. 83:195–206 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90161-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faria D., Rock J.R., Romao A.M., Schweda F., Bandulik S., Witzgall R., Schlatter E., Heitzmann D., Pavenstädt H., Herrmann E., et al. 2014. The calcium-activated chloride channel Anoctamin 1 contributes to the regulation of renal function. Kidney Int. 85:1369–1381 10.1038/ki.2013.535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrera L., Caputo A., Ubby I., Bussani E., Zegarra-Moran O., Ravazzolo R., Pagani F., and Galietta L.J.V.. 2009. Regulation of TMEM16A chloride channel properties by alternative splicing. J. Biol. Chem. 284:33360–33368 10.1074/jbc.M109.046607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrera L., Caputo A., and Galietta L.J.V.. 2010. TMEM16A protein: A new identity for Ca2+-dependent Cl− channels. Physiology (Bethesda). 25:357–363 10.1152/physiol.00030.2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrera L., Scudieri P., Sondo E., Caputo A., Caci E., Zegarra-Moran O., Ravazzolo R., and Galietta L.J.V.. 2011. A minimal isoform of the TMEM16A protein associated with chloride channel activity. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1808:2214–2223 10.1016/j.bbamem.2011.05.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francia S., Pifferi S., Menini A., and Tirindelli R.. 2014. Vomeronasal receptors and signal transduction in the vomeronasal organ of mammals. InNeurobiology of Chemical Communication. Mucignat-Caretta C., editor CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL: 297–324 10.1201/b16511-11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood I.A., and Large W.A.. 1999. Modulation of the decay of Ca2+-activated Cl− currents in rabbit portal vein smooth muscle cells by external anions. J. Physiol. 516:365–376 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.0365v.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haga S., Hattori T., Sato T., Sato K., Matsuda S., Kobayakawa R., Sakano H., Yoshihara Y., Kikusui T., and Touhara K.. 2010. The male mouse pheromone ESP1 enhances female sexual receptive behaviour through a specific vomeronasal receptor. Nature. 466:118–122 10.1038/nature09142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartzell H.C., Yu K., Xiao Q., Chien L.-T., and Qu Z.. 2009. Anoctamin/TMEM16 family members are Ca2+-activated Cl− channels. J. Physiol. 587:2127–2139 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.163709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrada G., and Dulac C.. 1997. A novel family of putative pheromone receptors in mammals with a topographically organized and sexually dimorphic distribution. Cell. 90:763–773 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80536-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hille B.2001. Ion Channels of Excitable Membranes. Third Edition Sinauer Associates, Sunderland, MA: 814 pp. [Google Scholar]

- Holy T.E., Dulac C., and Meister M.. 2000. Responses of vomeronasal neurons to natural stimuli. Science. 289:1569–1572 10.1126/science.289.5484.1569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang F., Wong X., and Jan L.Y.. 2012. International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. LXXXV: Calcium-activated chloride channels. Pharmacol. Rev. 64:1–15 10.1124/pr.111.005009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia C., and Halpern M.. 1996. Subclasses of vomeronasal receptor neurons: differential expression of G proteins (Giα2 and Goα) and segregated projections to the accessory olfactory bulb. Brain Res. 719:117–128 10.1016/0006-8993(96)00110-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S., Ma L., and Yu C.R.. 2011. Requirement of calcium-activated chloride channels in the activation of mouse vomeronasal neurons. Nat. Commun. 2:365 10.1038/ncomms1368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S., Ma L., Jensen K.L., Kim M.M., Bond C.T., Adelman J.P., and Yu C.R.. 2012. Paradoxical contribution of SK3 and GIRK channels to the activation of mouse vomeronasal organ. Nat. Neurosci. 15:1236–1244 10.1038/nn.3173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuruma A., and Hartzell H.C.. 2000. Bimodal control of a Ca2+-activated Cl− channel by different Ca2+ signals. J. Gen. Physiol. 115:59–80 10.1085/jgp.115.1.59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau Y.E., and Cherry J.A.. 2000. Distribution of PDE4A and Goα immunoreactivity in the accessory olfactory system of the mouse. Neuroreport. 11:27–30 10.1097/00001756-200001170-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leinders-Zufall T., Lane A.P., Puche A.C., Ma W., Novotny M.V., Shipley M.T., and Zufall F.. 2000. Ultrasensitive pheromone detection by mammalian vomeronasal neurons. Nature. 405:792–796 10.1038/35015572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leinders-Zufall T., Brennan P., Widmayer P., Chandramani S. P., Maul-Pavicic A., Jäger M., Li X.H., Breer H., Zufall F., and Boehm T.. 2004. MHC class I peptides as chemosensory signals in the vomeronasal organ. Science. 306:1033–1037 10.1126/science.1102818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leinders-Zufall T., Ishii T., Mombaerts P., Zufall F., and Boehm T.. 2009. Structural requirements for the activation of vomeronasal sensory neurons by MHC peptides. Nat. Neurosci. 12:1551–1558 10.1038/nn.2452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Ishii T., Feinstein P., and Mombaerts P.. 2004. Odorant receptor gene choice is reset by nuclear transfer from mouse olfactory sensory neurons. Nature. 428:393–399 10.1038/nature02433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liberles S.D., Horowitz L.F., Kuang D., Contos J.J., Wilson K.L., Siltberg-Liberles J., Liberles D.A., and Buck L.B.. 2009. Formyl peptide receptors are candidate chemosensory receptors in the vomeronasal organ. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 106:9842–9847 10.1073/pnas.0904464106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liman E.R.2003. Regulation by voltage and adenine nucleotides of a Ca2+-activated cation channel from hamster vomeronasal sensory neurons. J. Physiol. 548:777–787 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.037119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liman E.R., and Corey D.P.. 1996. Electrophysiological characterization of chemosensory neurons from the mouse vomeronasal organ. J. Neurosci. 16:4625–4637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liman E.R., Corey D.P., and Dulac C.. 1999. TRP2: A candidate transduction channel for mammalian pheromone sensory signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 96:5791–5796 10.1073/pnas.96.10.5791 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martini S., Silvotti L., Shirazi A., Ryba N.J., and Tirindelli R.. 2001. Co-expression of putative pheromone receptors in the sensory neurons of the vomeronasal organ. J. Neurosci. 21:843–848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsunami H., and Buck L.B.. 1997. A multigene family encoding a diverse array of putative pheromone receptors in mammals. Cell. 90:775–784 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80537-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munger S.D., Leinders-Zufall T., and Zufall F.. 2009. Subsystem organization of the mammalian sense of smell. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 71:115–140 10.1146/annurev.physiol.70.113006.100608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni Y.-L., Kuan A.-S., and Chen T.-Y.. 2014. Activation and inhibition of TMEM16A calcium-activated chloride channels. PLoS ONE. 9:e86734 10.1371/journal.pone.0086734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton C., Thompson S., and Epel D.. 2004. Some precautions in using chelators to buffer metals in biological solutions. Cell Calcium. 35:427–431 10.1016/j.ceca.2003.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedemonte N., and Galietta L.J.V.. 2014. Structure and function of TMEM16 proteins (anoctamins). Physiol. Rev. 94:419–459 10.1152/physrev.00039.2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Cornejo P., De Santiago J.A., and Arreola J.. 2004. Permeant anions control gating of calcium-dependent chloride channels. J. Membr. Biol. 198:125–133 10.1007/s00232-004-0659-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pifferi S., Pascarella G., Boccaccio A., Mazzatenta A., Gustincich S., Menini A., and Zucchelli S.. 2006. Bestrophin-2 is a candidate calcium-activated chloride channel involved in olfactory transduction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 103:12929–12934 10.1073/pnas.0604505103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pifferi S., Dibattista M., and Menini A.. 2009a. TMEM16B induces chloride currents activated by calcium in mammalian cells. Pflugers Arch. 458:1023–1038 10.1007/s00424-009-0684-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pifferi S., Dibattista M., Sagheddu C., Boccaccio A., Al Qteishat A., Ghirardi F., Tirindelli R., and Menini A.. 2009b. Calcium-activated chloride currents in olfactory sensory neurons from mice lacking bestrophin-2. J. Physiol. 587:4265–4279 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.176131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pifferi S., Cenedese V., and Menini A.. 2012. Anoctamin 2/TMEM16B: a calcium-activated chloride channel in olfactory transduction. Exp. Physiol. 97:193–199 10.1113/expphysiol.2011.058230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piper A.S., and Greenwood I.A.. 2003. Anomalous effect of anthracene-9-carboxylic acid on calcium-activated chloride currents in rabbit pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells. Br. J. Pharmacol. 138:31–38 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponissery Saidu S., Stephan A.B., Talaga A.K., Zhao H., and Reisert J.. 2013. Channel properties of the splicing isoforms of the olfactory calcium-activated chloride channel Anoctamin 2. J. Gen. Physiol. 141:691–703 10.1085/jgp.201210937 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu Z., and Hartzell H.C.. 2000. Anion permeation in Ca2+-activated Cl− channels. J. Gen. Physiol. 116:825–844 10.1085/jgp.116.6.825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu Z., Wei R.W., and Hartzell H.C.. 2003. Characterization of Ca2+-activated Cl− currents in mouse kidney inner medullary collecting duct cells. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 285:F326–F335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reisert J., Bauer P.J., Yau K.-W., and Frings S.. 2003. The Ca-activated Cl channel and its control in rat olfactory receptor neurons. J. Gen. Physiol. 122:349–364 10.1085/jgp.200308888 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivière S., Challet L., Fluegge D., Spehr M., and Rodriguez I.. 2009. Formyl peptide receptor-like proteins are a novel family of vomeronasal chemosensors. Nature. 459:574–577 10.1038/nature08029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rock J.R., Futtner C.R., and Harfe B.D.. 2008. The transmembrane protein TMEM16A is required for normal development of the murine trachea. Dev. Biol. 321:141–149 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.06.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryba N.J., and Tirindelli R.. 1997. A new multigene family of putative pheromone receptors. Neuron. 19:371–379 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80946-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber R., Faria D., Skryabin B.V., Wanitchakool P., Rock J.R., and Kunzelmann K.. 2014. Anoctamins support calcium-dependent chloride secretion by facilitating calcium signaling in adult mouse intestine. Pflugers Arch. In press 10.1007/s00424-014-1559-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder B.C., Cheng T., Jan Y.N., and Jan L.Y.. 2008. Expression cloning of TMEM16A as a calcium-activated chloride channel subunit. Cell. 134:1019–1029 10.1016/j.cell.2008.09.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scudieri P., Sondo E., Ferrera L., and Galietta L.J.V.. 2012. The anoctamin family: TMEM16A and TMEM16B as calcium-activated chloride channels. Exp. Physiol. 97:177–183 10.1113/expphysiol.2011.058198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scudieri P., Sondo E., Caci E., Ravazzolo R., and Galietta L.J.V.. 2013. TMEM16A-TMEM16B chimaeras to investigate the structure-function relationship of calcium-activated chloride channels. Biochem. J. 452:443–455 10.1042/BJ20130348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimazaki R., Boccaccio A., Mazzatenta A., Pinato G., Migliore M., and Menini A.. 2006. Electrophysiological properties and modeling of murine vomeronasal sensory neurons in acute slice preparations. Chem. Senses. 31:425–435 10.1093/chemse/bjj047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spehr J., Hagendorf S., Weiss J., Spehr M., Leinders-Zufall T., and Zufall F.. 2009. Ca2+-calmodulin feedback mediates sensory adaptation and inhibits pheromone-sensitive ion channels in the vomeronasal organ. J. Neurosci. 29:2125–2135 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5416-08.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephan A.B., Shum E.Y., Hirsh S., Cygnar K.D., Reisert J., and Zhao H.. 2009. ANO2 is the cilial calcium-activated chloride channel that may mediate olfactory amplification. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 106:11776–11781 10.1073/pnas.0903304106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stöhr H., Heisig J.B., Benz P.M., Schöberl S., Milenkovic V.M., Strauss O., Aartsen W.M., Wijnholds J., Weber B.H.F., and Schulz H.L.. 2009. TMEM16B, a novel protein with calcium-dependent chloride channel activity, associates with a presynaptic protein complex in photoreceptor terminals. J. Neurosci. 29:6809–6818 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5546-08.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tien J., Peters C.J., Wong X.M., Cheng T., Jan Y.N., Jan L.Y., and Yang H.. 2014. A comprehensive search for calcium binding sites critical for TMEM16A calcium-activated chloride channel activity. eLife. 3 10.7554/eLife.02772 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tirindelli R., Dibattista M., Pifferi S., and Menini A.. 2009. From pheromones to behavior. Physiol. Rev. 89:921–956 10.1152/physrev.00037.2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Touhara K., and Vosshall L.B.. 2009. Sensing odorants and pheromones with chemosensory receptors. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 71:307–332 10.1146/annurev.physiol.010908.163209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao Q., Yu K., Perez-Cornejo P., Cui Y., Arreola J., and Hartzell H.C.. 2011. Voltage- and calcium-dependent gating of TMEM16A/Ano1 chloride channels are physically coupled by the first intracellular loop. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 108:8891–8896 10.1073/pnas.1102147108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang C., and Delay R.J.. 2010. Calcium-activated chloride current amplifies the response to urine in mouse vomeronasal sensory neurons. J. Gen. Physiol. 135:3–13 10.1085/jgp.200910265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang T., Hendrickson W.A., and Colecraft H.M.. 2014. Preassociated apocalmodulin mediates Ca2+-dependent sensitization of activation and inactivation of TMEM16A/16B Ca2+-gated Cl− channels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 111:18213–18218 10.1073/pnas.1420984111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y.D., Cho H., Koo J.Y., Tak M.H., Cho Y., Shim W.-S., Park S.P., Lee J., Lee B., Kim B.-M., et al. 2008. TMEM16A confers receptor-activated calcium-dependent chloride conductance. Nature. 455:1210–1215 10.1038/nature07313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Y., Kuan A.-S., and Chen T.-Y.. 2014. Calcium-calmodulin does not alter the anion permeability of the mouse TMEM16A calcium-activated chloride channel. J. Gen. Physiol. 144:115–124 10.1085/jgp.201411179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zufall F., Ukhanov K., Lucas P., Liman E.R., and Leinders-Zufall T.. 2005. Neurobiology of TRPC2: from gene to behavior. Pflugers Arch. 451:61–71 10.1007/s00424-005-1432-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]