Abstract

Beak shape is a classical example of evolutionary diversification. Here chicken / duck beak development was used to study morphological variations among avian species. There is only one proliferative zone in the frontonasal mass of chickens, but two in ducks. These growth zones are associated with BMP4 activity. By tinkering with BMP4 in beak prominences, the shapes of the chicken beak can be modulated.

Keywords: Evolution, Development, localized growth zone, craniofacial morphogenesis, chicken, duck

During bird evolution, the beak emerged as the dominant avian facial feature, adapting birds to diverse eco-morphological opportunities (1-2). The beak is made of multiple facial prominences: the frontonasal mass (FNM), maxillary prominences (MXP), lateral nasal prominences (LNP) and mandibular prominence (MDP) (fig. S1A). In development all prominences are proportionally coordinated to compose a unique beak. Progress in molecular mechanisms underlying early beak morphogenesis has been reviewed recently (3-4). Here we focus on later events that mold the shape of the FNM, by comparing proliferation zones of chickens and ducks that have distinct beak shapes (Fig. 1A, fig. S2A).

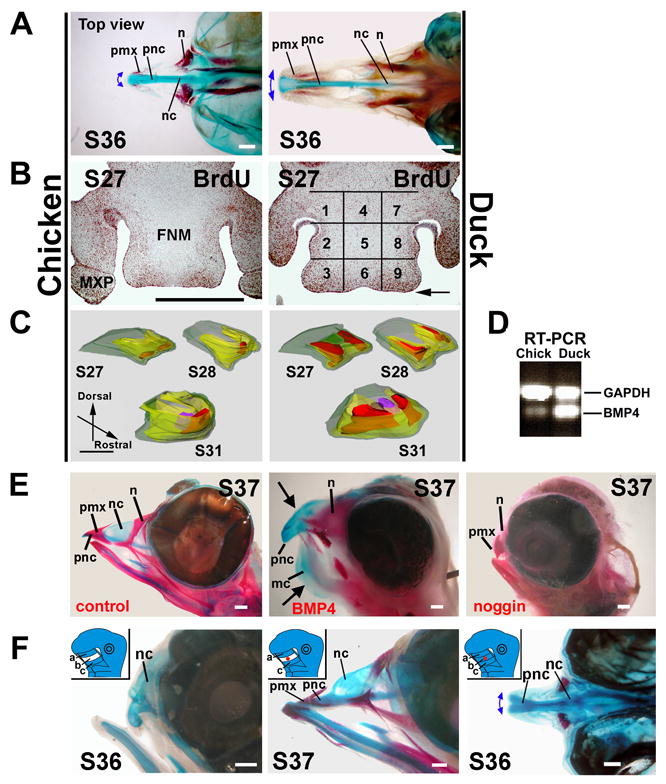

Figure 1. Cell proliferation and BMP4 function in chicken and duck beak morphogenesis.

(A) Stage 36 chicken and duck beaks, top view. Blue, cartilages. Red, bones. Double headed arrows indicates beak tip width (fig. S2E).

(B) Stage 27 frontal sections. 1.5 hr BrdU labeling. See fig. S1C for stages 26, 28, 29 and 31. Percent BrdU positive cells were quantified in 9 regions using the grid overlay (11) shown in table S1. Arrow indicates the rostral margin.

(C) Three dimensional reconstruction of the percent BrdU positive cells in the FNM. Red >20%, yellow 10-20%, green <10%. From this perspective, viewing the inner red zone through the yellow zone appears orange. Purple indicates proliferation in the cartilage region.

(D) BMP4 RT-PCR from stage 25 FNMs showed a higher BMP4/GAPDH ratio in ducks than in chickens.

(E) Left panel: Stage 37 control.

Middle and right panels: RCAS BMP4 or RCAS noggin were injected into all beak prominences of chicken embryos and harvested at Stage 37. Arrows point to enlarged skeletal elements.

(F) Left panel: Stage 20 chicken FNM was divided into three regions (a-c, defined in fig. S2B). Excision of region b containing the frontonasal ectodermal zone and subjacent mesenchyme (insert) truncated the upper beak with missing distal cartilage elements as observed at stage 36. Ablation of region a or c showed normal growth (not shown).

Middle panel: BMP4 beads (insert, red circle) can rescue most growth and cartilage elements from region b ablated specimens (stage 37).

Right panel: BMP4 bead addition to non-ablated FNM led to wider upper beaks (stage 36).

FNM, frontonasal mass; mc, Meckel's cartilage; MXP, maxillary prominence; n, nasal bone; nc, nasal chonchae; pmx, premaxilla bone; pnc, prenasal cartilage.

Size bars, 1mm.

There are temporal-spatial specific changes of proliferative zones within the FNM (Fig. 1B. More stages in fig. S1C. High power magnifications in fig. S1D). In stage 26 chickens, short BrdU pulse labeling showed cell proliferation in both FNM lateral edges. At stage 27, the two growth zones shifted toward the rostral margin, flanking the midline. At stage 28, these growth zones gradually converged into one centrally localized zone. In ducks, the two bilaterally positioned growth zones persisted in the lateral edges, widening the developing FNM. These changes precede morphological changes of the FNM. After stage 31, the basic beak structures were determined. Percent BrdU positive cells were quantified in 9 separate FNM regions (Fig. 1B; table S1). A growth zone shift is clearly seen in the three dimension reconstruction (Fig. 1C).

BMP2, 4 and BMP receptors are expressed in chicken beak prominences (5-7). Here we show higher expression of BMP4 transcripts in ducks using RT-PCR with primers conserved between chickens and ducks (Fig. 1D). Furthermore, BMP4 in the mesenchyme is closely associated with the shifting growth zones (fig. S1C, E). Comparisons showed more diffuse BMP4 expression in the duck than chicken, and duck MXPs are larger than chicken MXPs (fig. S1F).

We tested the roles of BMP4 in shaping beaks with two different strategies. To test whether BMP4 drives beak growth, replication competent avian sarcoma retrovirus (RCAS)-BMP4 were injected into all beak prominences of stage 22-23 chicken embryos. This led to larger beaks with significant increases in length, width and depth (Fig. 1E, middle panel, 100%, n = 15, p<0.001) compared to controls (Fig. 1E, left panel). To test whether BMP is physiologically involved, we mis-expressed noggin, the BMP antagonist. RCAS-noggin miniaturized beaks (Fig. 1E, right panel, 100%, n = 9, p<0.001). Histological sections showed BMP4 caused enhanced cell proliferation and skeletal differentiation as seen by H&E, BrdU and collagen-I staining (fig. S3A-D), consistent with results using RCAS BMP receptors (7). Noggin had the opposite effect (fig. S3A, C).

The “frontonasal ectodermal zone” flanked by FGF8 and Shh was shown to direct beak outgrowth (8, fig. S1B). We micro-surgically ablated this region (including epithelium and mesenchyme, region b in fig. S2B) and growth was arrested, missing the distal cartilage elements (Fig. 1F, left panel, 70%, n=20). BMP4 coated beads can partially restore growth even when this mesenchymal zone was deleted (Fig. 1F, middle panel, 62%, n=13). Implanting a BMP4 bead to the non-ablated FNM region induced a new growth zone leading to a wider beak (Fig. 1F, right panel, 33%, n=12). The moderate percentage may be due to a slight shift of bead positions in ovo, since the BMP bead effect appears to be highly location specific (6). The width of the upper beak tip was significantly increased (p<0.01) and resembled that of the duck (fig. S2F, bar graph). Albumin coated beads did not have this effect (fig. S2C). In 24 hr, BMP4 coated beads induced surrounding mesenchymal cell proliferation (not shown).

In summary, BMP4 is one of the major driving forces building beak mass. The number and activity of localized growth zones in the prominence confers its specific shape. Darwin's finches in the Galapagos Islands exhibit different sized and shaped beaks (1) regulated in part by BMP4 (9). Here we show we can produce beaks phenocopying those in nature by modulating BMP activities. It is likely that beak shape diversity was achieved by modulating prototypical molecular modules (10), and BMP pathway members may work as candidates mediating a spectrum of morphological designs for selection.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Tabin and Abzhanov for discussion, and Dr. Grant for comments. This work is supported by NIH AR42177, 47364 (CMC) and CA83716 (RW).

Footnotes

Competing Interest Statement: The authors declare that they have no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Grant PR, Grant BR. Science. 2002;296:707. doi: 10.1126/science.1070315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Feduccia A. In: The Origin and Evolution of Birds. ed. 2. Feducia A, editor. Yale Univ. Press; New Haven: 1999. pp. 93–137. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Helms JA, Schneider RA. Nature. 2003;423:326. doi: 10.1038/nature01656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Richman JM, Lee SH. BioEssays. 2003;25:554. doi: 10.1002/bies.10288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Francis-West PH, Tatla T, Brickell PM. Dev Dyn. 1994;201:168. doi: 10.1002/aja.1002010207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ashique AM, Fu K, Richman JM. Development. 2002;129:4647. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.19.4647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ashique AM, Fu K, Richman JM. Int J Dev Biol. 2002;46:243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hu D, Marcucio RS, Helms JA. Development. 2003;130:1749. doi: 10.1242/dev.00397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abzhanov A, Protas M, Grant BR, Grant PR, Tabin CJ. Accompanying manuscript. doi: 10.1126/science.1098095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.von Dassow, Munro E. J Exp Zool. 1999;285:307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.MacDonald ME, Abbott UK, Richman JM. Dev Dyn. 2004;230:335. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.