Abstract

Background

Incomplete penetrance and variable expressivity of arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy (ARVD/C) complicate family screening.

Objectives

To determine the optimal approach to longitudinal follow-up regarding (1) screening interval and (2) testing strategy in at-risk relatives of ARVD/C patients.

Methods

We included 117 relatives (45% male, 33.3±16.3 years) from 64 families who were at risk of developing ARVD/C by virtue of their familial predisposition (72% mutation carriers [92% Plakophilin-2]; 28% first-degree relatives of a mutation-negative proband). Subjects were evaluated using ECG, Holter monitoring, signal-averaged ECG, and cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR). Disease progression was defined as the development of a new criterion by the 2010 Task Force criteria (TFC; not “Hamid criteria”) at last follow-up, which was absent at enrollment.

Results

At first evaluation, 43 (37%) subjects fulfilled ARVD/C diagnosis according to the 2010 TFC. Among the remaining 74 (63%) individuals, 11/37 (30%) subjects with complete reevaluation experienced disease progression during 4.1±2.3 years of follow-up. Electrical progression (n=10 [27%] including ECG 14%, Holter monitoring 11%, signal-averaged ECG 14%) was more frequently observed than structural progression (n=1 [3%] on CMR). All 5/37 (14%) patients with clinical ARVD/C diagnosis at last follow-up had an abnormal ECG or Holter monitor, and the only patient with an abnormal CMR already had an abnormal ECG at enrollment.

Conclusion

Over a mean follow-up of 4 years, our study showed that (1) almost one-third of at-risk relatives have electrical progression; (2) structural progression is rare; and (3) electrical abnormalities precede detectable structural changes. This information could be valuable in determining family screening protocols.

Keywords: Cardiomyopathy, Progression, Electrocardiography, Magnetic Resonance Imaging, Screening

Introduction

Arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy (ARVD/C) is an inherited cardiomyopathy characterized by a high incidence of ventricular arrhythmias and an increased risk of sudden cardiac death (SCD) (1,2). The genetic era has significantly improved our understanding of heritability in ARVD/C, and a familial basis of the disease is now well established (3,4). Once the diagnosis of ARVD/C is made in an index patient with positive gene identification, guidelines exist on the optimal testing strategy to diagnose ARVD/C in first-degree relatives (5,6).

However, in our experience, only a subgroup of at-risk family members meet diagnostic Task Force Criteria (TFC) for ARVD/C at time of their initial evaluation; the majority have minor electrocardiographic (ECG) criteria, or reveal no additional criteria other than the positive family history (7). Although guidelines exist on how to evaluate at-risk family members at an initial visit, both the optimal longitudinal screening strategy and timing of subsequent evaluations to monitor development of ARVD/C criteria are unknown. Periodic reassessment using ECG recording, Holter monitoring, and echocardiography/cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) imaging are performed by many referral centers including ours, but objective evidence to support this approach is lacking. The burden on clinical resources is significant, as is the psychosocial impact on patients and their families (8). As such, there is an enormous need for objective data on the impact of serial screening in these at-risk individuals on both the development of ARVD/C criteria and clinical outcome. The purpose of our study was to examine the utility of serial non-invasive follow-up evaluation in individuals at risk of developing ARVD/C.

Methods

Study Population

The study population was recruited from the Johns Hopkins ARVD/C registry (ARVD.com). For the purpose of this study, we identified all families in which the proband fulfilled 2010 diagnostic TFC for ARVD/C (6) and had undergone comprehensive genetic testing for an ARVD/C-associated mutation in 5 desmosomal genes (1). Among families with a mutation-positive proband, we included all relatives who were genotyped and found to carry the same mutation as the proband. Non-genotyped and mutation-negative relatives were excluded (2). Among families with a mutation-negative proband, we included all first-degree relatives of the proband. According to clinical practice and genetics guidelines (5), genetic testing is not recommended in relatives of a mutation-negative proband, although a genetic cause of ARVD/C cannot be ruled out. Therefore, we only included first-degree relatives of a mutation-negative proband.

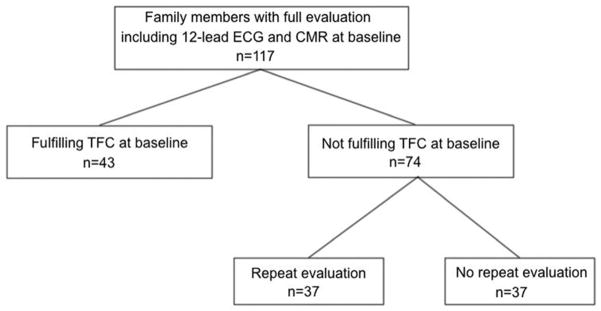

This yielded a total of 239 relatives from 107 families who were regarded at risk of developing ARVD/C. Among these individuals, 117 subjects underwent at least 1 full evaluation including 12-lead ECG and CMR with the images available for analysis. Therefore, the study population comprised 117 relatives from 64 families who were regarded at risk of developing ARVD/C and underwent full evaluation with the studies available for analysis. A patient flowchart is shown in Figure 1. The majority of subjects were “at risk” by virtue of the presence of an ARVD/C-associated pathogenic mutation (n=84; 92% Plakophilin-2); the remainder were first-degree relatives of a mutation-negative ARVD/C proband (n=33). All patients provided written informed consent. The Johns Hopkins School of Medicine Institutional Review Board approved the study.

Figure 1. Patient Flowchart.

Determination of the Study Population.

Abbreviations: CMR: Cardiac Magnetic Resonance, ECG: electrocardiogram, TFC: Task Force Criteria.

Clinical Characterization

The 2010 TFC were used for clinical characterization of family members (6) and not the criteria proposed by Hamid et al (7). All 117 subjects underwent routine 12-lead ECG (recorded at rest, 10 mm/mV at paper speed 25 mm/s), which was evaluated for repolarization (precordial T-wave inversion in V1-2 or beyond) and/or depolarization (epsilon waves or terminal activation duration ≥55 ms) criteria for ARVD/C (6). No individual was taking antiarrhythmic or other medications known to affect the QRS complex at the time of ECG acquisition. In addition, 24-hour Holter monitoring was evaluated for premature ventricular complex (PVC) count, which according to the 2010 TFC was regarded as abnormal if more than 500 PVCs were recorded (6). Exercise stress testing and loop recordings were evaluated for evidence of (non-)sustained ventricular tachycardia (VT). Signal-averaged ECG (SAECG) recordings, obtained using time-domain analysis with a bandpass filter of 40 Hz, were evaluated for evidence of late potentials. SAECG was regarded as abnormal if 1 of 3 parameters showed evidence of late potentials, as stated in the 2010 TFC (6).

CMR exams for all 117 individuals were performed according to standard protocols for ARVD/C, which have previously been described in detail (9,10). All CMRs were acquired on a 1.5T scanner with a phased array cardiac coil during repeated end-expiratory breath holds. ECG-gated cine images, fast spin-echo images, and contrast enhanced images after administration of a gadolinium chelate were acquired in both axial and short-axis planes covering the entire right ventricle (RV) and left ventricle (LV). Global ventricular volumes and function were calculated from the short-axis cine images using the software program QMASS (Medis, Leiden, the Netherlands). Three experienced CMR physicians blinded to all other patient information performed the CMR image analysis. CMR studies were analyzed for fulfillment of diagnostic criteria for ARVD/C, according to the revised 2010 TFC(6).

Follow-up and Outcome Measures

This study’s primary outcome was the diagnosis of ARVD/C according to the revised 2010 TFC (6), and not according to the criteria as described by Hamid et al. (7). Because all subjects were either an ARVD/C-associated pathogenic mutation carrier or first-degree relative of a mutation-negative ARVD/C proband, they all received a major criterion for family history. Therefore, an additional 2 minor criteria, or 1 major criterion sufficed for meeting diagnostic criteria for ARVD/C. In addition, we describe fulfillment of the criteria for familial ARVD/C as previously described by Hamid et al. in the Supplementary Material (7).

As a secondary outcome, we ascertained the occurrence of a life-threatening ventricular arrhythmia, which was a composite measure of the occurrence of spontaneous sustained VT, aborted SCD, SCD, or appropriate implantable cardioverter-defibrillator intervention for a ventricular arrhythmia, as described previously (11).

Statistical Analysis

All continuous data were presented as mean ± standard deviation or median (interquartile range [IQR]) and categorical variables as numbers (percentages). Continuous variables were compared between two groups using the independent Student t-test or Mann-Whitney U test; comparisons between three groups were performed using Analysis of Variance or Kruskal Wallis test. Categorical data were compared using the Chi-square test or Fisher exact test where appropriate. To evaluate differences between baseline and last follow-up for continuous variables, paired Student t-tests were used. For categorical variables, the proportion of disease progression (i.e., 2010 TFC fulfillment) was estimated using the Clopper-Pearson 95% confidence interval (CI). The freedom from disease progression (i.e., 2010 TFC fulfillment) was evaluated using Kaplan-Meier analysis. A p-value of <0.05 was considered significant. Statistical calculations were performed using SPSS version 21.0 (IBM, Chicago, IL).

Results

Study Population

The study population comprised 117 relatives from 64 families who were at risk of developing ARVD/C. Characteristics of the study participants are shown in Table 1. Mean age at first evaluation was 33.3±16.3 years, and 53 (45%) patients were men. The majority (n=72, 61%) of subjects were asymptomatic at presentation; the remainder (n=45, 39%) had a history of syncope, presyncope, or palpitations.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Family Members.

| No ARVD/C | ARVD/C | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall (n=117) | Completely Normal Evaluation (n=40) | Borderline/ Suspected ARVD/C* (n=34) | Definite ARVD/C diagnosis* (n=43) | P-value† | |

| Age at enrollment (yrs) | 33.3 ± 16.3 | 28.5 ± 16.9 | 35.5 ± 17.2 | 36.0 ± 14.3 | 0.038 |

| Male | 53 (45) | 17 (43) | 21 (62) | 15 (35) | NS |

| Mutation carrier | 84 (72) | 27 (68) | 24 (71) | 33 (77) | NS |

| Symptomatic | 45 (39) | 9 (23) | 10 (29) | 26 (61) | 0.001 |

| Palpitations | 36 (31) | 9 (23) | 9 (27) | 18 (42) | NS |

| Syncope | 11 (9) | 4 (10) | 0 (0) | 7 (16) | NS |

| Presyncope | 15 (13) | 4 (10) | 3 (9) | 8 (19) | NS |

| ECG, Holter monitor, or SAECG fulfilling TFC | 74 (63) | 0 (0) | 31 (91) | 43 (100) | NS |

| ECG fulfilling TFC | 46 (39) | 0 (0) | 11 (32) | 35 (81) | <0.001 |

| T-wave inversion V1-3 | 24 (21) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 24 (56) | <0.001 |

| T-wave inversion V1-2 | 11 (9) | 0 (0) | 4 (12) | 7 (16) | 0.034 |

| T-wave inversion V4-6 | 4 (3) | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | 3 (7) | NS |

| T-wave inversion V1-4 in presence of CRBBB | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (2) | NS |

| Epsilon wave | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (2) | NS |

| Prolonged TAD | 8 (7) | 0 (0) | 6 (18) | 2 (5) | 0.009 |

| Holter monitoring fulfilling TFC‡ | 19/91 (16) | 0/26 (0) | 2/30 (7) | 17/35 (49) | <0.001 |

| Median PVC count | 10 (IQR 1– 267) | 2 (IQR 0–10) | 2 (IQR 0–46) | 462 (IQR 39–2558) | <0.001 |

| SAECG fulfilling TFC§ | 40/86 (74) | 0/29 (0) | 23/32 (72) | 17/25 (68) | <0.001 |

| CMR fulfilling TFC | 21 (18) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 21 (49) | <0.001 |

| RV wall motion abnormalities | 31 (27) | 1 (3) | 4 (12) | 26 (61) | <0.001 |

| RV EDV/BSA (mL/m2) | 81.2 ± 25.8 | 70.7 ± 12.6 | 81.7 ± 21.1 | 95.0 ± 26.1 | <0.001 |

| RVEF (%) | 51.1 ± 8.3 | 54.6 ± 7.1 | 52.4 ± 6.5 | 47.2 ± 9.0 | 0.004 |

| LVEF (%) | 57.7 ± 6.5 | 59.0 ± 6.8 | 58.2 ± 5.7 | 56.0 ± 6.6 | NS |

Borderline/suspected ARVD/C defined as 3 TFC points; definite ARVD/C defined as ≥4 TFC points. The 2010 revised TFC were used for diagnostic categorization, and not the “Hamid criteria”.

P-value constitutes comparison of all three groups.

Holter monitoring fulfilled TFC when >500 PVCs/24 hours.

SAECG fulfilled TFC when at least 1 of 3 parameters were abnormal.

Abbreviations: ARVD/C: Arrhythmogenic Right Ventricular Dysplasia/Cardiomyopathy, CMR: cardiac magnetic resonance, CRBBB: complete right bundle branch block, ECG: electrocardiogram, PVC: premature ventricular complex, SAECG: signal-averaged electrocardiogram, TAD: terminal activation duration, TFC: Task Force Criteria.

Definite ARVD/C Diagnosis at Enrollment

Results for baseline clinical evaluation are shown in Table 1. At first evaluation, 43 (37%) individuals were diagnosed with ARVD/C according to the 2010 TFC. Mean age of these patients was 36.0±14.3 years, and 15 (35%) were male (Table 1). Definite ARVD/C patients were more often symptomatic than subjects without ARVD/C diagnosis (n=26 [61%] vs n=19 [26%], p<0.001). All 43 definite ARVD/C patients had electrical abnormalities on ECG, Holter monitor, and/or SAECG (Table 1). Structural changes on CMR were observed in 21 (49%) individuals.

No ARVD/C Diagnosis at Enrollment

Baseline Evaluation

Overall, 74 (63%) individuals did not fulfill ARVD/C diagnosis according, to the 2010 TFC at first evaluation. These patients were 31.7±17.3 years at time of first evaluation, and 38 (51%) were male. At enrollment, 43% (n=31) of these subjects had minor electrical abnormalities on ECG, Holter monitoring, and/or SAECG; none had TFC on CMR (Table 1).

Disease Progression

Patients without ARVD/C diagnosis were followed for a mean period of 4.1±2.3 years. Disease progression was defined as the development of a new ECG, Holter monitoring, SAECG, or CMR TFC, according to the 2010 TFC at last follow-up, which was absent at enrollment. Among 37 individuals with a complete re-evaluation, 28 (76%) were mutation carriers.

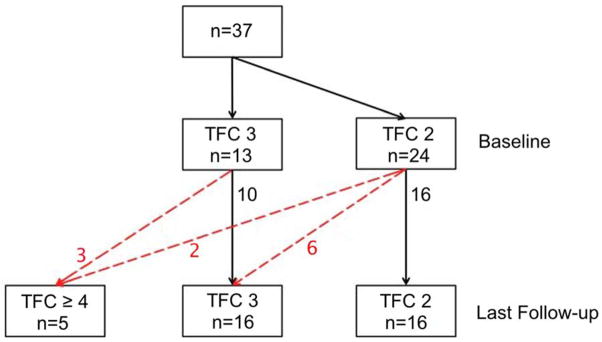

Eleven (30%) subjects showed evidence of disease progression (Figure 2). Five (45%) of these subjects were men, with a mean age of 29.3±16.0 (median 22.0, IQR 15.0–42.5) years at time of first evaluation. The vast majority (n=10/11, 91%) of these patients showed evidence of electrical progression on ECG, Holter monitor, and/or SAECG. Electrical progression was frequently observed on ECG (n=5 [14%]; 95% CI 5–29%). Holter monitoring progression was observed in 3/27 subjects (11%; 95% CI 2–29%). SAECG showed evidence of late potentials in 3/22 individuals (14%; 95% CI 3–35%). In addition to the 10 patients with progression on ECG, Holter monitoring and/or SAECG, 1 (3%) patient had a run of non-sustained VT of left bundle branch block superior axis morphology on exercise testing, thereby fulfilling a major arrhythmia TFC, according to the 2010 TFC that was absent at enrollment. None of the tests that were abnormal at baseline reverted to normal during follow-up (Supplementary Figure 1). A graphical representation of disease progression is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 2. Disease Progression in 37 Subjects with Complete Re-Evaluation.

Disease progression (defined as the development of a new 2010 TFC at last follow-up, which was absent at enrollment) is shown as red dotted lines; numbers depict the number of patients.

Abbreviations: ARVD/C: Arrhythmogenic Right Ventricular Dysplasia/Cardiomyopathy, TFC: Task Force Criteria.

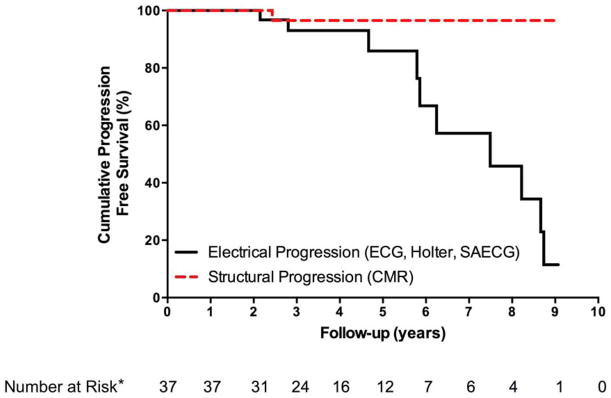

Figure 3. Time to Disease Progression among 37 Subjects with Complete Re-Evaluation.

*Per study design, time to progression (i.e. TFC fulfillment) and time to last follow-up were the same or within a 1-year range for electrical and structural progression in all individuals. Therefore, numbers at risk apply to both electrical and structural progression.

Abbreviations: CMR: Cardiac Magnetic Resonance, ECG: electrocardiogram, SAECG: signal-averaged electrocardiogram, TFC: Task Force Criteria.

Supplementary Figure 2 and Supplementary Table 2 show the prevalence of CMR findings in 37 subjects with serial structural evaluation. One patient had structural progression and fulfilled a minor 2010 TFC for CMR at last follow-up. This patient, who also had the non-sustained VT during exercise testing, already had an abnormal ECG with T-wave inversions in V1 and V3 (not V2) both at enrollment and last follow-up. Her baseline CMR showed RV dyskinesia with borderline RV end-diastolic volume 88.3 mL/m2 and RV ejection fraction 50%, increasing to RV end-diastolic volume 93.5 mL/m2 and RV ejection fraction 45% at last follow-up, thereby fulfilling a minor CMR TFC, according to the 2010 TFC. In the overall group, RV and LV volumes and function did not significantly change during follow-up (Supplementary Figure 2).

Outcome

Five (14%) subjects with an initially normal clinical evaluation were diagnosed with ARVD/C, according to the 2010 TFC during follow-up. Their clinical characteristics are described in Table 2. There was no statistically significant difference in length of follow-up between those with and without a definite ARVD/C diagnosis (median 5.9 [IQR 2.7–7.2] versus 3.6 [IQR 2.4–5.1] years, p=NS). The majority (n=4, 80%) of subjects with definite ARVD/C were female, with a median age of 39.0 (IQR 19.5–51.0) years at time of diagnosis.

Table 2.

Characteristics of Five Patients With a Definite ARVD/C Diagnosis at Last Follow-Up.

| Patient 1 | Patient 2 | Patient 3 | Patient 4 | Patient 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | F | F | M | F | F |

| Age at time of diagnosis | 21 yrs | 43 yrs | 59 yrs | 39 yrs | 18 yrs |

| Pathogenic mutation | - | + (PKP2) | + (PKP2) | + (PKP2) | + (PKP2) |

| Length follow-up | 5.9 yrs | 6.2 yrs | 8.2 yrs | 2.4 yrs | 2.8 yrs |

| Symptoms | Palpitations | Palpitations, presyncope | Palpitations, presyncope | Palpitations, syncope | Palpitations |

| Disease progression | |||||

| Electrical progression* | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Repolarization progression | BL: None FU: TWI V1- 3 |

- | - | - | BL: None FU: TWI V1- 2 |

| Arrhythmia progression | - | BL: 1 PVC/24h FU: 502 PVC/24h |

BL: 29 PVC/24h FU: 1105 PVC/ 24h |

BL: None FU: LBS NSVT |

BL: 2 PVC/ 24h FU: 4559 PVC/ 24h |

| Depolarization progression | - | - | - | - | BL: None FU: > TAD |

| Structural progression† | No | No | No | Yes | No |

| Clinical Phenotype | |||||

| Repolarization TFC | TWI V1-3 (major) | TWI V1-2 (minor) | None | None | TWI V1-2 (minor) |

| Depolarization TFC | Late potentials (minor) | None | >TAD + late potentials (minor) | None | >TAD (minor) |

| Arrhythmia TFC | None | 502 PVCs/24 hours (minor) | 1105 PVCs/24 hours (minor) | Non- sustained VT, LBBB sup. axis (major) | 4559 PVCs/24 hours (minor) |

| Structural TFC | None | None | None | Minor | None |

| Family History TFC | Major | Major | Major | Major | Major |

| TFC points at enrollment | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 |

| TFC points at last follow-up | 5 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 |

Disease progression was defined as the presence of a new 2010 TFC at last follow-up, which was absent at baseline.

Progression on ECG, Holter monitoring, or SAECG.

Progression on CMR.

Abbreviations: ARVD/C: Arrhythmogenic Right Ventricular Dysplasia/ Cardiomyopathy, BL: baseline, CMR: cardiac magnetic resonance, ECG: electrocardiography, FU: follow-up, LBBB: left bundle branch block, PKP2: Plakophilin-2, PVC: premature ventricular complex, >TAD: prolonged terminal activation duration, TFC: Task Force Criteria, TWI: T-wave inversion, VT: ventricular tachycardia.

Patients fulfilling 2010 TFC for ARVD/C at last follow-up were more often symptomatic at enrollment (n=3/5 [60%] vs n=4/32 [13%] asymptomatic, p=0.012) and more often had an abnormal baseline ECG (n=2/5 [40%] vs n=1/32 [3%] normal ECG, p=0.005) than patients who did not fulfill ARVD/C TFC at last follow-up. All other clinical characteristics and tests at enrollment were similar between those with and without a definite ARVD/C diagnosis at last follow-up. Among all clinical tests at last follow-up, SAECG was the only modality that did not distinguish between patients with and without a definite ARVD/C diagnosis (n=1/2 (50%) vs 9/25 (36%), p=NS).

Adverse Events

Among the overall cohort, 29/117 (25%) subjects had ICDs implanted, all of whom had a definite ARVD/C diagnosis at time of ICD implantation. During 4.1±2.3 years of follow-up, none of the 74 subjects without definite ARVD/C diagnosis at first evaluation experienced a sustained ventricular arrhythmia. In comparison, 8 (19%) of 43 patients with ARVD/C diagnosis at first evaluation experienced an arrhythmic event during 3.2±2.4 years of follow-up. Two events were spontaneous sustained VTs and 6 were appropriate ICD discharges. All patients experiencing an arrhythmic event were successfully diagnosed with ARVD/C prior to the arrhythmia. No subjects died or required heart transplantation during follow-up.

Discussion

Our study aimed to describe the utility of serial non-invasive follow-up evaluation in at-risk family members of ARVD/C probands (predominantly Plakophilin-2 mutation carriers). This study has several interesting results. First, we showed that relatives of ARVD/C probands who do not fulfill 2010 TFC for ARVD/C at first evaluation have a low short-term risk of sustained arrhythmia during a mean follow-up of 4 years. Second, during the 4-year follow-up period, we only observed minimal disease progression, which should be taken into account when determining the optimal screening interval for these patients. Third, electrical progression on ECG, Holter monitoring, and/or SAECG was seen to a much greater extent than structural progression on CMR, and all patients with a definite ARVD/C diagnosis at last follow-up had an abnormal ECG or Holter monitor. These results add to the growing body of evidence that electrical abnormalities precede detectable structural changes in ARVD/C, which should be reflected by the screening strategy employed in these individuals.

Favorable Prognosis

The high risk of ventricular arrhythmias in ARVD/C is well established. However, the arrhythmic propensity of the index patient must not necessarily be applied to at-risk relatives who by virtue of the incomplete penetrance and variable expressivity of this disease have a different, lower level of risk (11). In fact, our study shows that family members of ARVD/C patients who do not fulfill diagnostic 2010 TFC at first evaluation have a low risk of arrhythmia during a mean follow-up of 4 years. It is important to note in this regard that more than one-third of at-risk relatives fulfilled diagnostic 2010 TFC for ARVD/C at first evaluation, and 8/43 of these subjects experienced a ventricular arrhythmia during follow-up. This emphasizes the importance of complete screening in relatives upon diagnosis in a proband, and underlines that the low risk of arrhythmias in short-term follow-up only applies to those who do not fulfill 2010 TFC at initial evaluation.

Determining the Optimal Screening Interval

An important result of our study is that the overall rate of progression in relatives of ARVD/C probands is slow, and unlikely to be appreciated on short-term screening. Disease progression was observed in 30% of subjects with an initially normal clinical investigation during 4 years of follow-up. However, only minimal changes were observed for all single testing modalities between baseline and last follow-up. These results are in alignment with prior reports, showing limited change on electroanatomic scar mapping and CMR during a follow-up period of about 4 years (12,13). This lack of short-term progression is important to consider when re-evaluating family members of ARVD/C index patients at a 2- to 3-year interval. The pre-test probability of finding new abnormalities is low, and the observed changes are likely to be minor with questionable clinical significance. Although our mean follow-up duration was relatively short, and the results by no means provide definite reassurance for patients at risk of developing ARVD/C, these data provide important information for clinical care in which follow-up protocols are still largely based on consensus opinions and clinical judgments. One recent study from our group described that endurance exercise and frequent physical activity contribute to disease development and arrhythmic occurrence in ARVD/C-associated desmosomal mutation carriers (14), suggesting that at-risk individuals should not participate in high-level athletics. It is certainly possible, and perhaps likely, that the absence of disease progression that we observed in the current study may not apply to subjects who continue to participate in athletic training.

Determining the Optimal Screening Strategy

Over the last decade, CMR has gained enormous popularity as the modality of choice for structural evaluation in ARVD/C. However, in our cohort of subjects with high a priori risk of ARVD/C, there was only 1 patient with an initially normal structural evaluation who had a minor CMR criterion at last follow-up. In addition, other qualitative CMR parameters, such as RV delayed enhancement and fat, did not increase the yield of CMR screening.

Based on a cross-sectional study in ARVD/C mutation carriers, we have previously proposed that electrical abnormalities precede detectable structural changes in individuals at risk of developing ARVD/C (15). This is also supported by a study by Protonotarios et al., which reported on 205 at-risk subjects who were similarly followed over a median period of 4 years (16). In their study, 16 mutation carriers were newly diagnosed with ARVD/C during follow-up, of whom 100% had ECG abnormalities, while only 31% had structural alterations. The current study extends prior reports by showing that electrical abnormalities are not only more prevalent in a cross-sectional setting in ARVD/C, but also precede structural abnormalities in a longitudinal fashion. Only 1 patient in this study had structural progression on CMR, but whether this really represents disease progression is arguable. This patient already had an abnormal CMR with RV free wall dyskinesia at baseline and showed a minimal volume increase (RV end-diastolic volume 88.3 mL/m2 to 93.5 mL/m2) fulfilling a minor TFC. Moreover, she had an abnormal ECG with T-wave inversion in leads V1 and V3 (but not V2), and a run of non-sustained VT on exercise testing fulfilling a major arrhythmia TFC for ARVD/C.

Interestingly, all patients who fulfilled diagnostic TFC for ARVD/C at last follow-up had electrical abnormalities on ECG and/or Holter monitor in addition to their familial predisposition. This suggests that electrical abnormalities precede detectable structural changes in subjects at risk for ARVD/C. Importantly, this study as well as prior reports have shown that no single test should be relied upon for diagnosis and risk stratification purposes in ARVD/C, as even a 12-lead ECG can be normal in definite ARVD/C cases (17,18). Therefore, a full baseline evaluation still remains necessary in determining an at-risk individual’s phenotype. In our cohort, SAECG was the only test that did not distinguish between individuals with and without a definite ARVD/C diagnosis at last follow-up. While this questions the significance of an abnormal SAECG in the evaluation of subjects at risk for ARVD/C, SAECG has been shown to have incremental value for ARVD/C evaluation among newly diagnosed ARVD/C probands in a prior study (18). Adding to the results of prior studies (11,15,16), this supports a screening strategy including serial ECG and Holter monitoring in all subjects at risk of developing ARVD/C and using CMR in selected cases when symptoms and/or ECG or Holter monitoring abnormalities are present. Prior studies have shown that arrhythmic risk in ARVD/C is very low in children before the age of puberty (19). Further studies are needed to validate our findings and identify the age window at which screening is particularly likely to detect disease expression.

Limitations

Studies on ARVD/C, in particular involving CMR, are typically small in size. Only 37 subjects without ARVD/C diagnosis at enrollment underwent complete re-evaluation using at least ECG and CMR. The other 37 individuals did not undergo repeat CMR, and re-evaluation using ECG was not performed in the majority of these subjects. Since baseline characteristics and endpoints were similar between subjects with and without repeat evaluation, a significant selection bias seems unlikely. The presence of multiple pathogenic mutations in ARVD/C probands has been previously described (20). Although only 1 pathogenic mutation has been identified in all mutation-positive families of this study, presence of modifier genes could be responsible for disease progression in some family members. Although the majority of subjects carried a pathogenic ARVD/C causing mutation, a subset of our cohort was made up of family members of a mutation-negative proband. This provided us with the opportunity to study a reasonably large cohort of family members at risk of developing disease. ICDs were implanted in 25% of our cohort, only among those with a definite ARVD/C diagnosis. This may have increased our ability to identify ventricular arrhythmias among those with an ICD.

Conclusions

To our best knowledge, this study is the first to describe the yield of serial cardiac evaluation using a combination of ECG, Holter monitoring, SAECG, and CMR in at-risk relatives of ARVD/C probands. Our results reassure the practicing physician that individuals who do not fulfill the 2010 revised TFC at first evaluation have a low risk of arrhythmia during a mean follow-up of 4 years. Disease progression is minimal and likely not appreciated on biennial or triennial screening. Since electrical abnormalities precede detectable structural changes on CMR, the use of serial CMR screening may be restricted to symptomatic family members with electrical abnormalities on ECG and Holter monitoring.

Supplementary Material

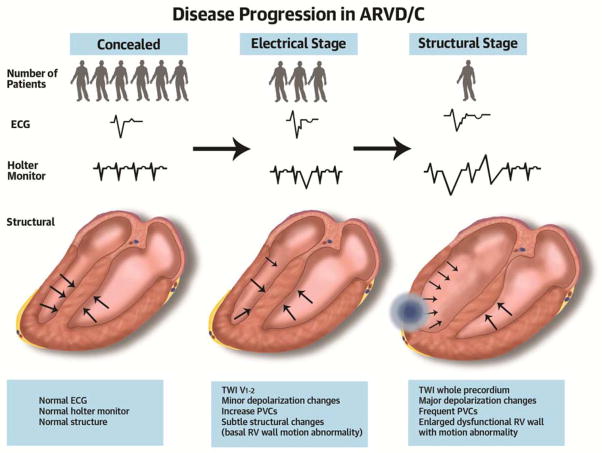

Figure 4 (Schematic). Disease Progression in ARVD/C.

Family members of an arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy proband have a long latent stage without signs or symptoms of disease (concealed stage). Electrical changes on electrocardiogram or Holter monitoring are usually the first sign of disease, and structural abnormalities may be observed later. Disease progression is typically slow.

Abbreviations: ARVD/C: Arrhythmogenic Right Ventricular Dysplasia/Cardiomyopathy, ECG: electrocardiogram, PVC: premature ventricular complex, RV: right ventricular, TWI: T-wave inversion.

Perspectives.

COMPETENCY IN MEDICAL KNOWLEDGE

Arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy (ARVD/C) is a slowly progressive disease in which electrical abnormalities precede detectable structural changes.

COMPETENCY IN PATIENT CARE 1

After comprehensive evaluation of relatives of patients with ARVD/C, physicians may reassure those not fulfilling the 2010 Task Force criteria that progression occurs slowly if at all and that the risk of arrhythmia is generally low.

COMPETENCY IN PATIENT CARE 2

Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging of the relatives of patients with ARVD/C may be restricted to subjects who are symptomatic and those with depolarization or repolarization abnormalities on ECG or Holter monitoring.

TRANSLATIONAL OUTLOOK

Genetic characterization and longer-term follow-up of families of patients with ARVD/C are needed to define additional factors associated with early and late development of structural and electrical abnormalities.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding: The authors wish to acknowledge funding from the Alexandre Suerman Stipend (to AT), the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (K23HL093350 to HT), the Dr. Francis P. Chiaramonte Private Foundation, the St. Jude Medical Foundation and Medtronic Inc. The Johns Hopkins ARVD/C Program is supported by the Dr. Satish, Rupal, and Robin Shah ARVD Fund at Johns Hopkins, the Bogle Foundation, the Healing Hearts Foundation, the Campanella family, the Patrick J. Harrison Family, the Peter French Memorial Foundation, and the Wilmerding Endowments.

Abbreviations

- ARVD/C

Arrhythmogenic Right Ventricular Dysplasia/Cardiomyopathy

- CI

Confidence Interval

- CMR

Cardiac Magnetic Resonance

- ECG

12-lead Electrocardiography

- IQR

Interquartile Range

- PVC

Premature Ventricular Complex

- SAECG

Signal-Averaged Electrocardiography

- TAD

Terminal Activation Duration

- TFC

Task Force Criteria

Footnotes

Disclosures: Dr. Calkins receives ARVD/C research support from Medtronic and St. Jude Medical.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Marcus FI, Fontaine GH, Guiraudon G, et al. Right ventricular dysplasia: a report of 24 adult cases. Circulation. 1982;65:384–98. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.65.2.384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Corrado D, Thiene G, Nava A, et al. Sudden death in young competitive athletes: clinicopathologic correlations in 22 cases. Am J Med. 1990;89:588–96. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(90)90176-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nava A, Bauce B, Basso C, et al. Clinical profile and long-term follow-up of 37 families with arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;36:2226–33. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(00)00997-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dalal D, James C, Devanagondi R, et al. Penetrance of mutations in plakophilin-2 among families with arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48:1416–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.06.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ackerman MJ, Priori SG, Willems S, et al. HRS/EHRA expert consensus statement on the state of genetic testing for the channelopathies and cardiomyopathies. Heart Rhythm. 2011;8:1308–39. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2011.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marcus FI, McKenna WJ, Sherrill D, et al. Diagnosis of arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy/dysplasia: proposed modification of the task force criteria. Circulation. 2010;121:1533–41. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.840827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hamid MS, Norman M, Quraishi A, et al. Prospective evaluation of relatives for familial arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy/dysplasia reveals a need to broaden diagnostic criteria. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;40:1445–50. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)02307-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.James CA, Tichnell C, Murray B, et al. General and disease-specific psychosocial adjustment in patients with arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy with implantable cardioverter defibrillators: a large cohort study. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2012;5:18–24. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.111.960898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bhonsale A, James CA, Tichnell C, et al. Risk stratification in arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy-associated desmosomal mutation carriers. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2013;6:569–78. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.113.000233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tandri H, Calkins H, Nasir K, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging findings in patients meeting task force criteria for arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2003;14:476–82. doi: 10.1046/j.1540-8167.2003.02560.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dalal D, Tandri H, Judge DP, et al. Morphologic variants of familial arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy a genetics-magnetic resonance imaging correlation study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:1289–99. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.12.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dalal D, Nasir K, Bomma C, et al. Arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia: a United States experience. Circulation. 2005;112:3823–32. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.542266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sen-Chowdhry S, Morgan RD, Chambers JC, et al. Arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy: etiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Annu Rev Med. 2010;61:233–53. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.052208.130419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Basso C, Corrado D, Marcus FI, et al. Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. Lancet. 2009;373:1289–300. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60256-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Riley MP, Zado E, Bala R, et al. Lack of uniform progression of endocardial scar in patients with arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy and ventricular tachycardia. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2010;3:332–8. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.109.919530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Conen D, Osswald S, Cron TA, et al. Value of repeated cardiac magnetic resonance imaging in patients with suspected arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2006;8:361–6. doi: 10.1080/10976640500527082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.James CA, Bhonsale A, Tichnell C, et al. Exercise increases age-related penetrance and arrhythmic risk in arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy-associated desmosomal mutation carriers. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62:1290–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.06.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.te Riele AS, Bhonsale A, James CA, et al. Incremental value of cardiac magnetic resonance imaging in arrhythmic risk stratification of arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy-associated desmosomal mutation carriers. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62:1761–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.11.087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Protonotarios N, Anastasakis A, Antoniades L, et al. Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy/dysplasia on the basis of the revised diagnostic criteria in affected families with desmosomal mutations. Eur Heart J. 2011;32:1097–104. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.te Riele AS, James CA, Bhonsale A, et al. Malignant arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy with a normal 12-lead electrocardiogram: a rare but underrecognized clinical entity. Heart Rhythm. 2013;10:1484–91. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2013.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.