Abstract

Higher organisms rely on a closed cardiovascular circulatory system with blood vessels supplying vital nutrients and oxygen to distant tissues. Not surprisingly, vascular pathologies rank among the most life-threatening diseases. At the crux of most of these vascular pathologies are (dysfunctional) endothelial cells (ECs), the cells lining the blood vessel lumen. ECs display the remarkable capability to switch rapidly from a quiescent state to a highly migratory and proliferative state during vessel sprouting. This angiogenic switch has long been considered to be dictated by angiogenic growth factors (eg vascular endothelial growth factor; VEGF) and other signals (eg Notch) alone, but recent findings show that it is also driven by a metabolic switch in ECs. Furthermore, these changes in metabolism may even override signals inducing vessel sprouting. Here, we review how EC metabolism differs between the normal and dysfunctional/diseased vasculature and how it relates to or impacts the metabolism of other cell types contributing to the pathology. We focus on the biology of ECs in tumor blood vessel and diabetic ECs in atherosclerosis as examples of the role of endothelial metabolism in key pathological processes. Finally, current as well as unexplored ‘EC metabolism’-centric therapeutic avenues are discussed.

Keywords: endothelial cell metabolism, angiogenesis, diabetes, atherosclerosis, cancer

Angiogenesis and endothelial cell biology in a nutshell

Blood vessels supply tissues with oxygen and nutrients, whereas lymphatic vessels absorb and filter interstitial fluids from these tissues 1, 2. While mostly remaining quiescent throughout adult life, blood vessels maintain the capacity to rapidly form new vasculature in response to injury or in pathological conditions. Key players in this new vessel formation are the blood vessel lining endothelial cells (ECs). Capillary sprouting, an important component of neovascularization, is accomplished by interactions among three different EC subtypes, each carrying out highly specific roles during this process 3: tip cells are highly migratory, non-proliferative ECs that guide and pull the new sprout in the correct direction, stalk cells elongate the new sprout by their high proliferative capacity, and quiescent phalanx cells mark the more mature part of the vessel by their typical cobblestone shape 4.

The specification of ECs into one of these subtypes is mainly driven by the key angiogenic vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and occurs upon VEGF production by hypoxic tissues and macrophages trying to regain oxygenation and nutrient supply by attracting new vessel sprouts. These processes have been best studied in retinal angiogenesis where a continuous VEGF gradient will eventually reach the existing vascular front allowing VEGF to bind the VEGF receptor 2 (VEGFR2) in ECs, predestining these ECs to become tip cells. Intriguingly, the newly appointed tip cells themselves instruct their neighboring ECs to adopt a stalk cell phenotype: the Notch ligand Delta like 4 (Dll4) produced by tip cells binds Notch receptors in adjacent ECs whereby the Notch intracellular domain (NICD) is released and reprograms the cell to express the decoy receptor VEGFR1 at the expense of VEGFR2, causing reduced VEGF sensitivity and enforcing stalk cell behavior 5. Although seemingly rigid, tip/stalk specification is a highly dynamic feature in which, through continuous cell shuffling, the EC with the highest VEGFR2 / VEGFR1 expression ratio (and thus the highest VEGF responsiveness) is at the tip of the new sprout at every given moment 6.

When the tip cell encounters another tip cell or a pre-existing vessel, both will fuse to form a lumenized, perfused vessel, a process referred to as anastomosis. As the new vessel sprout matures, ECs adopt a more quiescent, non-proliferative and non-migratory, cobblestone-like phenotype called phalanx cells. High VEGFR1 levels and subsequent low VEGF responsiveness enable these cells to stay quiescent for years. By virtue of their tight monolayer organization and barrier function, phalanx cells facilitate blood flow within the blood vessel lumen, which further promotes quiescence of phalanx cells 3. In addition, ECs in the maturing vessel excrete platelet derived growth factor B (PDGF-B) to attract PDGF receptor β (PDGF-Rβ) expressing pericytes. Coverage of the nascent vessel with these mural cells contributes to proper vessel functioning and stability 7.

EC metabolism in health: driving vessel sprouting

Although often mistakenly considered as inert lining material with the sole function of guiding and conducting blood, ECs are key players in health as well as in life-threatening vascular diseases. Before discussing the metabolism of ECs and other cell types involved in vascular pathologies, we will briefly review glucose, fatty acid and amino acid metabolism, the three major energy and biomass generating metabolic pathways in healthy ECs (Fig. 1), and highlight their importance in normal vessel sprouting. Most of the findings reported below are from in vitro experiments and, although they have tremendously increased our understanding of EC metabolism, await further confirmation in an in vivo setting.

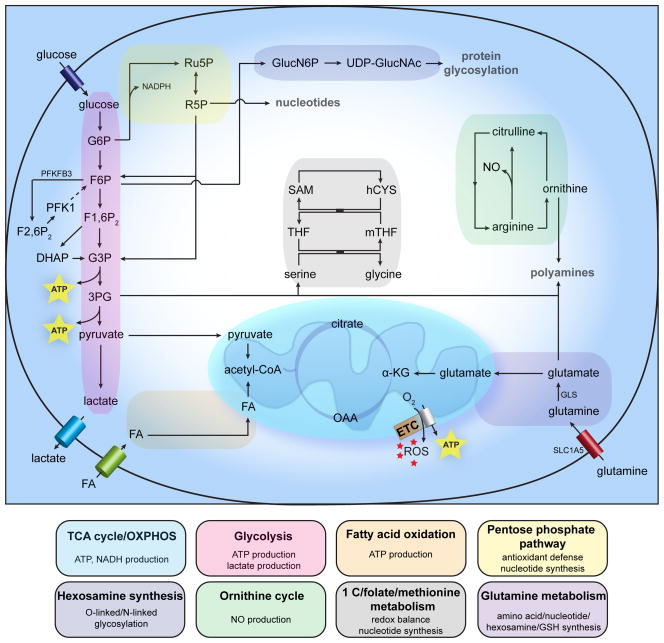

Figure 1. General metabolism in healthy ECs.

Schematic and simplified overview of general EC metabolism. Abbreviations used: 3PG: 3-phosphogylcerate; α-KG: α-ketoglutarate; ATP: adenosine triphosphate; DHAP: dihydroxyacetone phosphate; ETC: electron transport chain; Fu1,6P2: fructose-1,6-bisphosphate; F2,6P2: fructose-2,6-bisphosphate; F6P: fructose-6-phosphate; FA: fatty acid; G3P: glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate; G6P: glucose-6-phosphate; GLS: glutaminase; GlucN6P: glucosamine-6-phosphate; hCYS: homocysteine; mTHF: 5-methyltetrahydrofolate; NADPH: nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate; NO: nitric oxide; OAA: oxaloacetate; PFK1: phosphofructokinase-1; PFKFB3: 6-phosphofructo-2-kinase/fructose-2,6-bisphosphatase 3; R5P: ribose-5-phosphate; ROS: reactive oxygen species; Ru5P: ribulose-5-phosphate; SAM: S-adenosylmethionine; SLC1A5: solute carrier family 1 member 5; THF: tetrahydrofolate; UDP-GlucNAc: uridine diphosphate N-acetylglucosamine.

ATP generation through oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) could be expected to be the preferred energy-yielding pathway in ECs based on their immediate exposure to blood stream oxygen. However, ECs have a relatively low mitochondrial content 8 and rely primarily on glycolysis with in vitro glycolysis rates comparable to or even higher than in cancer cells and exceeding glucose oxidation and fatty acid oxidation flux by over 200-fold 9–11. Per molecule of glucose, ECs miss out on approximately 34 molecules of ATP by opting for glycolysis instead of oxidative phosphorylation. Notwithstanding the lower ATP per glucose yield, high glycolytic flux can yield more ATP in a shorter time than OXPHOS when available glucose is unlimited, and has the advantage of shunting glucose into glycolysis side-branches (see below) for macromolecule synthesis. Whether large amounts of glucose are indeed available in the metabolically harsh environment into which vessels sprout, remains to be determined. Additional advantages of ‘aerobic glycolysis’ in ECs could be 1) lower OXPHOS-generated reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels, 2) preservation of maximal amounts of oxygen for transfer to perivascular cells, 3) adaptation of ECs to the hypoxic surroundings they will grow into, and 4) production of lactate as a pro-angiogenic signaling molecule 12.

Upon VEGF-stimulation, ECs double their glycolytic flux to meet increased overall energy and biomass demands and to locally supply energy for cytoskeleton remodeling during EC migration. As such, ECs display increased expression of the glycolysis activator 6-phosphofructo-2-kinase/fructose-2,6-bisphosphatase 3 (PFKFB3) 10, which by virtue of its much higher kinase activity (as compared to its phosphatase activity) produces large amounts of fructose-2,6-bisphosphate (F2,6P2) to activate phosphofructokinase-1 (PFK1), a rate-limiting enzyme in glycolysis. Interestingly, both genetic and pharmacologic inhibition of PFKFB3 results in decreased sprouting capacity in in vitro spheroid assays and in reduced vessel branching and outgrowth in vivo, even though there is only a partial reduction in glycolytic flux (~ 60% of total flux is retained) 10, 13. Moreover, in vitro knock-down of PFKFB3 diminished tip cell behavior even when Notch was simultaneously knocked-down to create a strong genetic ‘pro-tip cell’ cue. Conversely, PFKFB3 overexpression was able to push ECs that were genetically instructed to become stalk cells by NICD overexpression, back into a tip cell phenotype, underscoring the pivotal role of glycolysis in ECs 10. As mentioned above, blood flow contributes to phalanx cell quiescence. Remarkably, the laminar shear stress exerted by blood flow reduced glucose uptake, glycolysis and mitochondrial content in ECs and lowered the expression of PFKFB3 and PFK1 to sustain a metabolically quiescent behavior. Mechanistically, the flow-responsive Krüppel-like factor 2 (KLF2) transcription factor was found to bind to a KLF2 binding site in the PFKFB3 promoter to subsequently repress PFKFB3 transcription 14. Taken together these findings underscore the pivotal role of glycolysis in EC subtype specification.

Glucose can also be shunted into two side branches of glycolysis: the hexosamine biosynthesis pathway (HBP) and the pentose phosphate pathway (PPP). The HBP generates N-acetylglucosamine for protein O- and N-glycosylation and uses glucose, glutamine, acetyl-CoA and uridine for that purpose 15. In ECs, the functionality of key angiogenic proteins like Notch and VEGFR2 depends on their glycosylation status 16, 17. Although its in vivo role is less well characterized, the endothelial HBP possibly serves as a nutrient-sensing pathway to guide new vessels to nutrient-rich regions by glycosylating these key angiogenic proteins. Inhibition of the HBP significantly reduces angiogenesis 18.

Glucose enters the PPP as glucose-6-phosphate (G6P) to fuel 5-carbon sugar (pentose) production for nucleotide and nucleic acid synthesis 19. Genetic or pharmacologic inhibition of G6P dehydrogenase (G6PDH), the rate-limiting enzyme of the oxidative PPP branch (oxPPP; generating nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) and ribulose-5-phosphate (Ru5P)), and transketolase, a rate-limiting enzyme in the non-oxidative PPP branch (non-oxPPP, yielding ribose-5-phosphate (R5P)) reduces EC viability and migration 20, 21. The oxPPP generates NADPH that can be used as reducing equivalent in lipid synthesis and in restoring the antioxidant capacity of glutathione by converting the oxidized form (GSSG) back to the reduced form (GSH) 19.

Besides glucose, fatty acids represent another fuel source for ECs. In vitro glucose deprivation, for example, causes ECs to increase their fatty acid oxidation (FAO) flux in an AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK)-dependent manner 9. Interestingly, VEGF enhances the expression of the fatty acid uptake and trafficking protein FABP4, which is required for normal EC proliferation 22. Given its presumably modest contribution to total ATP levels in ECs 10, the exact role of FAO is uncertain at present. Whether FAO is involved in EC redox homeostasis (as is the case in stressed cancer cells 23, 24) and biosynthesis of macromolecules, remains to be determined. Interestingly, capillary ECs in fatty acid consuming tissues (such as the heart and skeletal muscle) express FABP4 and FABP5 to transport fatty acids across the endothelium into these tissues 25 (a process requiring tight control given that excess fatty acid uptake by the tissue can cause insulin resistance). Transendothelial transport of lipids is regulated by VEGF-B, though this matter is debated 26, 27. The required fatty acids are supplied inside the capillary lumen through hydrolysis of triglyceride-rich lipoproteins by lipoprotein lipase (LPL). Intriguingly, LPL is secreted into the interstitium by parenchymal cells and relies on the glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored high-density-lipoprotein-binding protein 1, expressed by the capillary ECs, to be transported to the capillary lumen 28.

Although gaining increasing attention in cancer cells, amino acid (AA) metabolism is largely understudied in ECs. Arginine is the exception to this rule and has been broadly studied for its conversion to citrulline and nitric oxide (NO), an important regulator of EC function, by endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) 29. The non-essential amino acid glutamine is the most abundant amino acid in the plasma, which makes it a supposedly easily accessible fuel. Glutamine has the added value to contribute both its carbons and nitrogens to ECs’ metabolism (though the relative importance of both in vessel sprouting remains to be determined) and can therefore serve different, mostly biosynthetic metabolic fates 30. ECs express the solute carrier family 1 member 5 (SLC1A5) to take up glutamine and were reported to have high glutaminase (GLS) activity 31, 32; this enzyme converts glutamine to glutamate in the first and rate-limiting step of glutaminolysis (the series of reactions that serves to supply glutamine carbons to the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) to replenish intermediates that were used for biosynthesis purposes (anaplerosis)) (Fig. 1). Inhibition of glutaminase causes ECs to senesce prematurely and to stop proliferating 33. Two different GLS isozymes have been identified in mammalian cells; kidney-type GLS1 and liver-type GLS2. In cancer cells at least, these isozymes serve different functions: GLS1 is a c-MYC target and mainly drives glutamine carbons into the TCA 34, 35, whereas GLS2 is downstream of p53 and preferably shunts glutamine carbons and nitrogen into glutathione for antioxidant purposes 36. Remarkably, transcriptomic analysis of laser capture micro-dissected tip cells from the microvasculature in mouse postnatal retinas, showed increased expression of GLS2 37; the exact biological significance hereof is unknown at present. Glutamine-derived glutamate can be used for the production of other non-essential amino acids. Serine is of particular interest here since its synthesis requires the α-nitrogen from glutamate and 3-phosphoglycerate (3PG) from the glycolytic pathway and thus exemplifies the functional interconnection between glucose and glutamine metabolism 38 (Fig. 1). ECs express D-3-phosphoglycerate-dehydrogenase, the rate-limiting enzyme in serine synthesis. Serine seems to predominantly affect blood pressure by promoting vasodilation through activation of KCa channels present in the endothelium 39, 40. Furthermore, by virtue of its interconversion with glycine, serine can feed one-carbon metabolism, which is crucial for redox balance and for nucleotide, protein and lipid synthesis 41.

The above metabolic pathways in ECs (and the rate-limiting enzymes therein) are not only controlled by substrate and end product availability but also by key metabolic ‘sensors’ like the highly conserved serine threonine kinase adenosine monophosphate (AMP)-activated protein kinase (AMPK). Unmet energy demands, reflected by increased intracellular AMP levels cause AMPK to increase flux through energy generating metabolic pathways (eg FAO) to maintain cellular energy levels. Specifically in ECs, AMPK can also be activated by EC-specific stimuli such as hypoxia/ischemia and (blood flow) shear stress. For more details on the role of endothelial AMPK in angiogenesis and ischemia as well as on the link with nitric oxide (NO) and statins (see below) the reader is referred to the following reviews 42, 43. For additional information on how signaling proteins drive cellular metabolism (not restricted to ECs), the reader is referred to the following reviews 44–46.

The endothelium is one of the largest organs in the body and probably also one of the most heterogeneous. The endothelium comprises of not just one stereotype EC but rather a large collection of EC subtypes differing in phenotype, function and location. Exactly how this heterogeneity translates to EC metabolism – or vice versa how EC metabolism drives this heterogeneity – remains largely unknown. Probably if not certainly, the different EC types adapt the flux through the metabolic pathways generalized above in order to meet their highly specific energy, redox and biosynthesis demands. Arterial, venous, microvascular and lymphatic ECs each have different functions and face different oxygen levels, most probably reflected by differences in their core metabolism. As such, pulmonary microvascular ECs differ from pulmonary arterial ECs in glucose and oxygen consumption and in total intracellular ATP levels 47. Brain microvascular ECs have significantly more mitochondria than peripheral ECs 48; whether this implies increased oxidative metabolism in these cells remains unknown. EC heterogeneity and possible metabolic consequences also apply to the disease state (see below). Tumor ECs for example differ significantly when isolated from high- versus low-metastatic tumors 49 (tumor endothelium heterogeneity is reviewed in ref 50). Whether the role of muscle ECs in trans-endothelial insulin transport (described further below) also reflects a tissue-specific EC characteristic remains to be determined. As such, EC heterogeneity is a given; its translation to differences in metabolic wiring, however, remains to be explored.

Metabolic features of ECs and accomplices in disease vessels

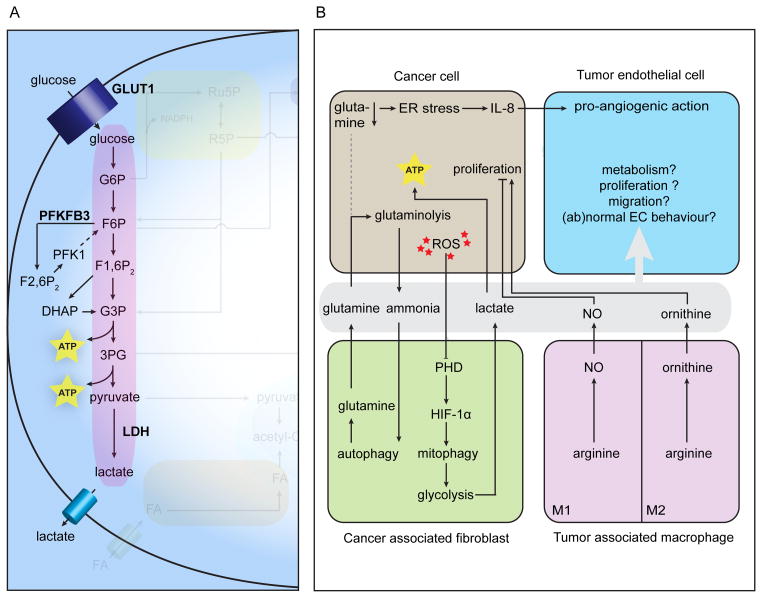

Given that ECs take the lead part but are not soloists in vascular disorders, the following section highlights the main metabolic changes in ECs in the disease state and looks for parallels and differences with or effects on the metabolism of other cell types involved, for as far as they have been studied. We focus on dysfunctional ECs in diabetes (Fig. 2A) and atherosclerosis (a frequent complication in diabetes) (Fig. 2B) and on excessively growing ECs in tumor blood vessels (Fig. 3A,B). Much like in healthy ECs, the data on EC metabolism in disease are mostly from in vitro / ex vivo experiments.

Figure 2. Metabolic pathways involved in disease characterized by EC dysfunction.

A, In diabetes, hyperglycemia triggers mainly increased ROS production through eNOS uncoupling and PPP impairment resulting in stalled glycolytic flux with glycolytic intermediates being diverted into alternative metabolic pathways leading to additional excess ROS and AGEs production. B, Atherosclerosis is characterized at a metabolic level mainly by eNOS uncoupling resulting in excess ROS production and loss of NO-dependent vasodilation. Abbreviations used: as in Figure 1. 1,3BPG: 1,3-bisphosphoglycerate; 3DG: 3-deoxyglucosone; ADMA: asymmetric dimethyl arginine; AGE: advanced glycation end product; AGXT2: alanine-glyoxylate aminotransferase; AR: aldose reductase; BH2: 7,8-dihydrobiopterin; BH4: tetrahydrobiopterin; DAG: diacylglycerol; DDAH: dimethyl-arginine dimethyl-aminohydrolase; DHFR: dihydrofolate reductase; eNOS: endothelial nitric oxide synthase; G6PDH: glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase; GADPH: glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; GFAT: glutamine fructose-6-phosphate amidotransferase; GGPP: geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate; GTP: guanosine triphosphate; GTPCH: GTP cyclohydrolase; HMG-CoA: hydroxymethylglutaryl coenzyme A; HMGCR: 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase; MET: methionine; MTHFR: methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase; PARP1: polyADP-ribose polymerase 1; PKC: protein kinase C; PPP: pentose phosphate pathway; SDH: sorbitol dehydrogenase.

Figure 3. Metabolic pathways in tumor vessels and metabolic interactions between cancer and stromal cells.

A, ECs in tumor vasculature are presumably characterized by increased glycolysis. B, Metabolic interactions between cancer and stromal cells. Abbreviations used: as in Figures 1 and 2. ER: endoplasmic reticulum; GLUT: glucose transporter; HIF: hypoxia-inducible factor; IL-8: interleukin-8; LDH: lactate dehydrogenase; PHD: prolyl hydroxylase domain.

Diabetic ECs

Diabetics have increased blood glucose levels that drastically change EC metabolism and cause EC dysfunction. Hyperglycemia reduces G6PDH-mediated entry of glucose into the PPP, thereby lowering production of the main intracellular reductant NADPH and increasing oxidative stress levels 21. Contributing to this is the high glucose-induced activation of NADPH oxidases generating ROS 51. Excess glucose induces arginase activity, which consumes the NO-precursor arginine and as such uncouples the NO generating eNOS activity; instead superoxide anions are being produced. ROS together with reactive nitrogen species cause DNA strand breaks, which activate the enzyme polyADP-ribose polymerase (PARP1). The glycolytic enzyme glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH; converting glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate (G3P) to 1,3-bisphosphoglycerate (1,3BPG)) is ADP-ribosylated by PARP1 (ref 52), causing glycolytic flux to stall and glycolytic intermediates to pile up and to be diverted into the following ‘pathological’ pathways (Fig. 2A): 1) Excess glucose is shunted into the polyol pathway where it is converted to sorbitol by the rate-limiting enzyme aldose reductase (AR) 53, a reaction that further depletes NADPH and increases ROS. Sorbitol in turn is converted to fructose by sorbitol dehydrogenase (SDH), which leads to the production of 3-deoxyglucosone (3DG), a highly reactive α-oxo-aldehyde that contributes to the non-enzymatic generation of toxic advanced glycation endproducts (AGE) 54. 2) The fructose-6-phosphate (F6P) overload causes increased flux through the HBP, which, as discussed above, is crucial for protein glycosylation, but under hyperglycemic conditions impedes normal angiogenic behavior. eNOS activity, for example, is reduced by increased O-glycosylation 55. 3) G3P and dihydroxyacetone phosphate (DHAP) are diverted towards methylglyoxal production, further contributing to ROS and AGE production. Also, G3P and DHAP are used for de novo synthesis of diacylglycerol (DAG) and subsequent protein kinase C (PKC) activation that has been shown to cause vascular abnormalities 56. Remarkably, on top of stalling glycolysis and subsequently impacting glycolytic side-branches, hyperglycemia causes endothelial mitochondriopathy featuring defects in mitochondrial biogenesis and mitophagy (the latter causing damaged mitochondria to pile up), mitochondrial fragmentation and impaired functionality and increased ROS production (reviewed in ref 48). Of note, GAPDH inactivation and glucose-shunting into glycolytic side-branches were remedied by normalizing mitochondrial ROS levels 57, 58.

As end products of dysfunctional EC metabolism, AGEs have far reaching effects on the ECs’ immediate extracellular surroundings but also on other cells types. AGEs can crosslink key-molecules (eg, laminin, elastin, collagens) in the extracellular matrix (ECM) basement membrane causing increased vessel stiffness, which further contributes to the diabetes-related vascular complications (for more details the reader is referred to the following review 59). The broad intracellular effects of circulating AGEs are mediated through ligating the receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE), which is expressed in monocytes, smooth muscle cells (SMC) and ECs themselves 60. Contributing to vascular dysfunction, AGEs cause hyperpermeability and induce tissue factor expression leading to a more procoagulant endothelium 59. RAGE ligation in monocyte-derived macrophages increases the expression of macrophage scavenger receptor class A and CD36, favoring uptake of oxidized low-density lipoproteins (LDL) 61. Conversely, efflux of cholesterol to high-density lipoprotein (HDL) is hampered by reduced expression of the ATP binding cassette transporter G1 in human macrophages exposed to AGE-bovine serum albumin; a finding that mainly depended on RAGE 62. Both phenomena contribute to foam cell transformation, a key process in atherosclerosis (see below). In vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs), AGE-RAGE ligation increases proliferation and chemotactic migration, which contributes to VSMC accumulation in atherosclerotic plaques and is mediated by different signaling cascades (for more details the reader is referred to other reviews 59, 60, 63). In VSMCs, AGE-RAGE also induces autophagy via ERK/Akt signaling to metabolically sustain the increased proliferation 64, and induces inducible NOS (iNOS) activity through NADPH-oxidase derived ROS in an NF-κB-dependent manner 65. In addition, AGEs in SMCs have been reported to cause increased fibronectin/ECM production and (vascular) calcification 66–68.

The exact role for glutamine (metabolism) in diabetic endothelial cell dysfunction is not fully understood, although the effect of hyperglycemia on the HBP and subsequent eNOS inhibition (see above) proves the involvement of glutamine given that its γ-nitrogen is coupled to fructose-6-phosphate (F6P) to yield glucosamine-6-phosphate (GlucN6P) in the glutamine fructose-6-phosphate aminotransferase (GFAT)-mediated first and rate-limiting step of the HBP 32, 69. However, disease-mimicking high glucose treatment (25 mM) of the human umbilical vein endothelial cell line EA.hy926 revealed a small reduction in glutamine being oxidized 70. Interestingly, a genome-wide association study identified a single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) on chromosome 1q25, which causes a 32% reduction in the expression of glutamine synthetase (GS or GLUL: the enzyme responsible for de novo glutamine synthesis) in ECs. Only in diabetic patients, and not in the non-diabetic participants, this SNP (occurring at an approximate allelic frequency of 0.7 in diabetics) leads to increased risk for coronary heart disease (CHD), with each risk allele carrying a 36% higher risk for CHD. Plasma pyroglutamic acid (an intermediate of the γ-glutamyl cycle and direct precursor for glutamic acid) to glutamic acid ratios were altered in diabetics homozygous for the SNP, but the exact causative mechanism remains to be determined 71.

The available data on FAO in diabetic ECs appear highly contextual and somewhat contradictory. High glucose treatment of EA.hy926 ECs caused increased palmitate oxidation 70, whereas a similar high glucose treatment on primary human umbilical vein ECs caused an increase in malonyl-coenzyme A levels (known to inhibit carnitine palmitoyltransferase-1 (CPT-1), the rate-limiting enzyme for FAO) and substantial decrease in FAO 72. Of note, leptin, of which the circulating levels are increased in diabetes, induces FAO in ECs by increasing CPT-1 activity and by lowering acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC; rate-limiting enzyme for fatty acid synthesis) activity 73. Insulin resistance itself (under normal glucose levels/tolerance) increases FAO in aortic ECs 74.

On a more systemic level, capillary blood flow in muscle is increased by insulin through increased eNOS expression and NO levels and subsequent vasodilation (capillary recruitment). This drives ‘nutritive flow’ and ensures transport across capillary ECs of glucose and insulin itself towards the muscle interstitium (for more details and possibly contradictory findings on insulin-induced capillary blood flow, the reader is referred to the following review 75). Muscle (micro)-vascular dysfunction and reduced eNOS activity are among the earliest signs of insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes 76.

Atherosclerosis

ECs in atherosclerosis display perturbations in metabolic pathways pertaining to NO generation. Atherosclerosis is characterized early on by uncoupled and reduced eNOS, resulting in an imbalance between the anti-atherogenic molecule NO and pro-atherogenic superoxides 77. In the endothelium, eNOS normally generates NO through enzymatic oxidation of arginine to citrulline, requiring several cofactors including NADPH, flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD), flavin mononucleotide (FMN), Ca2+/calmodulin and tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4) 78–80. eNOS-derived NO mediates endothelium-dependent vasodilation, required for normal vascular homeostasis, and inhibits important events promoting atherosclerosis, such as platelet aggregation, smooth muscle cell proliferation and migration, leukocyte adhesion and oxidative stress 81, 82. When the availability of the NO-precursor arginine and cofactor BH4 is reduced, eNOS fails to produce NO and citrulline and instead produces ROS 77, 83, a process called eNOS uncoupling (Fig. 2B).

The amino acid arginine is the main source for the generation of NO with approximately 1% of the daily arginine intake being metabolized through this pathway 84. Even though endothelial and plasma levels of arginine are sufficiently high to support eNOS-dependent NO synthesis, arginine did appear to be rate-limiting in atherosclerotic patients with impaired endothelium-dependent vasodilation 85. A possible explanation for this is the existence of endogenous arginine analogues such as asymmetric dimethyl arginine (ADMA) which antagonizes endothelium-dependent vasodilation and NO synthesis, by competing with arginine for binding to the catalytic center of eNOS 86. ADMA plasma concentrations have been shown to be elevated up to 10-fold in atherosclerotic patients compared to healthy subjects and is now considered a major cardiovascular risk factor 87. Approximately 80% of ADMA is eliminated through metabolization into citrulline and dimethylamine via dimethyl-arginine dimethyl-aminohydrolase (DDAH) 88. DDAH is impaired by oxidative stress, allowing the accumulation of ADMA and subsequent inhibition of NO production 89. The remaining 20% of ADMA can also be metabolized by alanine-glyoxylate aminotransferase (AGXT2), a mitochondrial aminotransferase primarily expressed in the kidney. The competition between arginine and ADMA may explain why arginine supplementation is only beneficial in atherosclerotic patients with high ADMA plasma levels, and not in healthy patients with low ADMA plasma levels. Finally, oral supplementation of arginine not only benefits endothelium-dependent vasodilation, but was also shown to reverse the hyperadhesive phenotype of monocytes and T-lymphocytes in atherosclerotic patients 90.

Next to eNOS uncoupling, NADPH oxidases are important sources of ROS in the vasculature 91. In early atherosclerotic vessels, endothelial-derived NADPH oxidases produce superoxides, whereas further along the disease, mainly VSMC-derived NADPH oxidases produce superoxides 92, 93. NADPH oxidases are induced in ECs and macrophages by plaque components such as oxidized LDL. Subsequent NADPH oxidase-derived ROS production has a detrimental effect in atherosclerosis by triggering increased expression of adhesion molecules, induction of VSMC proliferation and migration, apoptosis of ECs and oxidation of lipids. Much like hyperglycemia in diabetes (see above), atherosclerosis- inducing triglycerides and oxidized low-density lipoprotein (oxLDL) can cause endothelial mitochondria to become dysfunctional by damaging mitochondrial DNA and other vital components, eventually leading to increased ROS 48.

The cofactor BH4 is de novo produced from guanosine triphosphate (GTP) in the pathway where the highly regulated GTP cyclohydrolase I (GTPCH) is the first and rate-limiting enzyme. The endothelial cell-autonomous need for de novo BH4 production was only recently confirmed in mice with EC-specific knock-out of GTPCH showing loss of EC NO activity and increased O2•− production 94. Cellular BH4 is oxidatively degraded to inactive 7,8-dihydrobiopterin (BH2) and it is assumed that the intracellular BH4/BH2 ratio, rather than absolute BH4 levels, is the key factor for eNOS uncoupling 95. BH4 is recovered through a salvage pathway in which dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR) reduces BH2 back to BH4 (ref 96). The involvement of DHFR links BH4 levels (and eNOS activity by extension) to one-carbon metabolism through which single carbon units from folates are transferred to methyl-acceptors (folate cycle) and in which methyltetrahydrofolate (mTHF) donates one-carbon to recycle methionine (and subsequently the methyldonor S-adenosylmethionine (SAM)) from homocysteine (methionine cycle) (for more details the reader is referred to the following review 97) (Fig. 2B). Both homocysteine by itself (in in vitro assays) as well as inactivating mutations in methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR; the enzyme generating mTHF) leading to hyperhomocysteinemia lower BH4 availability, possibly by affecting GTPCH and DHFR activity. Finally, recycling of the methyldonor SAM provides a link between one-carbon metabolism and ADMA (see above), which is generated through methylation of arginine residues by protein arginine N-methyltransferase (PRMT).

The EC mevalonate or isoprenoid pathways, which use acetyl-CoA to generate cholesterol, have a peculiar effect on eNOS transcript levels. Active RhoA/ROCK signaling, involved in regulating cell shape, polarity, contractility and locomotion by controlling cytoskeletal dynamics (see reviews 98, 99), reduces eNOS mRNA stability 100. However, in order to be active and acquire its correct membranous localization, RhoA needs to be prenylated with geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate (GGPP), an intermediate of the mevalonate pathway. The serum lipid lowering statins (see under translational opportunities below) inhibit the rate-limiting 3-hydroxyl-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase (HMG-CoA reductase) in the mevalonate pathway and subsequently reduce cholesterol levels 101. A beneficial non-lipid lowering effect of statins, originating from the same inhibitory action, is to inhibit Rho activation in ECs by reducing the availability of geranylgeranyl and as such to restore eNOS expression levels 102. In contrast, by blocking the mevalonate pathway, statins also reduce the availability of farnesyl pyrophosphate, required for the synthesis of Coenzyme Q10, an important cofactor for eNOS 103, 104 (see also under Translational Opportunities). However, the effects on Rho prenylation are observed at statin doses far exceeding the clinically relevant dose, an important remark given the reported dose-dependency of statin effects on ECs (eg ref 105). Noteworthy, regular-dose statins primarily affect Rac1 signaling by increasing the expression of the small GTP-binding protein GDP dissociation stimulator (SmgGDS), which causes nuclear translocation and subsequent degradation of Rac1 leading to reduced ROS levels 106. For further reading on the pleiotropic effects of statins on ECs the reader is referred to the following reviews 107, 108.

Furthermore, cholesterol metabolism drives the mischievous behavior of monocyte-derived macrophages in atherosclerosis. After ingestion by macrophages, lipoproteins’ cholesteryl esters are converted into free cholesterol and fatty acids through hydrolysis in late endosomes 109. Subsequently, the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) enzyme acyl-CoA:cholesterol acyltransferase (ACAT) converts free (unesterified) cholesterol into cholesteryl fatty acid esters through re-esterification; these cholesteryl fatty acid esters are the main component of foam cells 110. Incessant accumulation of free cholesterol may result in free cholesterol-induced cytotoxicity and subsequent inflammation and atherosclerotic lesion development. Cholesterol accumulation can be counteracted by ATP-binding cassette protein A1 (ABCA1) transporter-mediated cholesterol efflux to lipid-deficient apolipoprotein (Apo) A-I. Macrophages in ABCA1-deficient mice indeed have reduced cholesterol efflux 111, while overexpression of ABCA1 in macrophages was associated with a substantial reduction in atherosclerosis 112. A similar cholesterol efflux pathway to mature HDL exists via the scavenger receptor class B type I (SR-BI) or the ATP-binding cassette protein G1 (ABCG1) transporter 113, 114; the expression of ABCG1 is reduced by AGEs produced by diabetic ECs (see above). Finally, apoA-I binding protein (AIBP)-mediated cholesterol efflux from ECs regulates proper EC function and proper VEGFR2-mediated angiogenesis, exemplified by the findings that knock-down or overexpression of aibp in zebrafish caused dysregulated and reduced angiogenesis, respectively 115.

Tumor vasculature

Within the tumor microenvironment, metabolic features of the cancer cells are mostly hardwired (driven by genetic alterations), whereas stromal cells adapt their normal metabolism to their environment and to meet the demands of the tumor. Even though full characterization of tumor EC metabolism is in its infancy, it most likely resembles the metabolism of highly activated ECs, since the tumor-induced switch from quiescence to proliferation and migration during sprouting is metabolically taxing. Normal, quiescent ECs display higher than expected glycolysis rates in order to generate sufficient energy to maintain crucial functions (eg tight barrier function in certain vascular beds) 3, 10, 116; tumor ECs have increased lactate dehydrogenase B expression and probably further increase glycolysis as indicated by the induction of the glucose transporter GLUT1 in the tumor endothelium 117, 118 and the capability of (tumor-derived) VEGF to induce PFKFB3 expression 10 (Fig. 3A). In this respect, ECs and cancer cells are highly alike 10 given that most cancer cells are highly glycolytic (Warburg effect 119). Furthermore, both cell types co-compartmentalize glycolytic enzymes with actin-rich regions in invading structures such as filopodia (ECs) and invadopodia 120 (cancer cells) to ensure efficient energy production required for motility and invasion 10.

Although the exact role of EC glutamine metabolism and the relative contribution of the two GLS isoforms (GLS1 vs GLS2) is undetermined, blocking GLS causes reduced EC proliferation and increased senescence 33, which suggests a crucial role for glutamine in tumor vessel sprouting, further supported by the notion that glutamine is the most abundant amino acid and a readily available carbon and nitrogen source. Cancer cells from their side have indeed rewired their glutamine metabolism to maximize glutamine carbon flux towards replenishment of the TCA cycle and nitrogen usage for nucleotide, amino acid and glutathione production. The c-MYC oncogene has been reported to underlie this rewiring by inducing glutaminolysis-related enzymes and rendering cancer cells ‘glutamine-addicted’ 34, 35. This dependency on glutamine is further exemplified by the recent findings that, under hypoxic conditions or impaired mitochondrial respiration, cancer cells can reductively carboxylate glutamine-derived α-ketoglutarate (α-KG) into citrate for de novo lipid synthesis 121–123. If and to what extent reductive carboxylation contributes to lipid synthesis in the predominantly glycolytic/hypoxic (see above) tumor ECs and total stromal compartment is currently an open question.

The glutamine-derived non-essential amino acid arginine is, as mentioned above, pivotal in EC behavior because of its precursor role in eNOS-mediated NO synthesis. Generation of the correct perivascular NO gradient by eNOS promotes vessel maturation 124. Cancer cells from their side express neuronal NOS (nNOS) or iNOS to generate NO, which perturbs the optimal perivascular NO gradient and renders tumor vessels abnormal 124, 125.

Ammonia, produced during the first two steps of glutaminolysis (deamination of glutamine to glutamate and glutamate to α-KG), is an auto- and paracrine inducer of autophagy 126. In co-culture systems, ammonia produced by high glutaminolysis rates in breast cancer cells, induced autophagy in cancer associated fibroblasts (CAFs) leading to increased proteolysis and increased glutamine levels, which in turn feeds the high glutaminolysis rate in the cancer cell compartment and as such closes the loop 127. In vitro glutamine deprivation causes osteosarcoma and lung cancer cells to excrete the pro-inflammatory chemokine interleukin-8 (IL-8), which has pro-angiogenic activity 128. An apparent ER stress and depletion of TCA intermediates underlies this phenomenon; treatment with dimethyl α-KG replenished the TCA and abrogated IL-8 excretion129. Although the in vivo relevance of these findings remains to be determined, they exemplify how cancer cell metabolism instructs the stromal component (cq tumor ECs).

Much like ECs, fibroblasts maintain a relatively high glycolytic flux in quiescence to sustain basal cell functions and they approximately double this flux upon proliferation 130. CAFs have increased glycolysis rates to sustain a very peculiar relationship with cancer cells. The activity of oxygen-sensing prolyl-hydroxylase domain (PHD) proteins in CAFs is inhibited by high ROS levels coming from neighboring cancer cells. Subsequent hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-1α stabilization causes excess NO production through autophagic degradation of caveolin-1, a repressor of NO production. These high NO levels cause mitochondria in CAFs to become dysfunctional and to be cleared through mitophagy; consequently, CAFs need to turn to glycolysis for energy production and as such supply lactate (and pyruvate) which cancer cells use to generate ATP in the TCA cycle 131, 132. This phenomenon contradicts the predominant view on cancer cells as the absolute “Warburgian” cells and has been coined the ‘Reverse Warburg effect’; the stromal compartment is suspected to be glycolytic (through mitochondrial dysfunction) and to feed energy-rich lactate into the TCA cycle of the cancer cell for highly efficient aerobic ATP production for anabolism and growth 132, 133. It remains to be determined if highly glycolytic tumor ECs engage in a similar host-parasite-like relationship with cancer cells as CAFs do (Fig. 3B).

Although the immune component of the tumor is intensively studied nowadays, insights to the metabolism of tumor-associated immune cells are lacking. Aerobic glycolysis is induced upon switching from a naive T cell to an activated T cell to fulfill the energy needs for proliferation, differentiation and activity (for more detailed information on the metabolic features of different T cell subtypes, we refer to other reviews 12, 134). If and how the move from the oxygen and nutrient-rich blood and lymph vessels to the harsh tumor microenvironment changes the metabolism of activated T cells is less well characterized. T cells in the tumor microenvironment display an ‘exhaustion’-like phenotype, a state of non-responsiveness and reduced effector function normally caused by constant antigen exposure (cfr chronic inflammation), and increase the expression of the immune-inhibitory programmed death receptor 1 (PD1) and the cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen-4 (CTLA4), ligation of which has been shown to reduce glycolysis 135, 136. Lactate excreted by cancer cells promotes IL-17A production, which negatively regulates T cell-mediated anti-tumor mechanisms 137. Although the metabolism of tumor associated macrophages (TAMs) is not fully known, these cells display a peculiarly divergent use of arginine within the tumor stroma depending on their polarization status (M1 versus M2 phenotype; see other reviews 12, 138 for more detail). M1 macrophages suppress tumor growth and use arginine and iNOS to produce NO, which is toxic for cancer cells. Tumor growth promoting M2 macrophages use arginase 1 to convert arginine to ornithine which can feed proliferation of cancer cells 139.

Translational opportunities

The need for efficient and specific therapeutics to treat life-threatening vascular disorders is high. As evidenced above, diseased ECs reorient their core metabolism in dysfunction and during imbalanced angiogenesis raising the question if more ‘EC metabolism’-centric treatment strategies should be considered. Given that the necessary technical and conceptual advances to fully understand diseased EC metabolism to the tiniest details are starting to emerge only now, EC metabolism as a therapeutic target is still in its infancy. Nevertheless, recent publications provided convincing proof of concept 10, 13. The current approach in tumor angiogenesis relies on blocking VEGF or its receptors; a ‘growth factor-centric’ treatment that suffers from tumor-based escape mechanisms (ie use of alternative additional growth factors to induce excess angiogenesis), leading to resistance 140. The recent data on how the glycolysis regulator PFKFB3 in ECs controls vessel sprouting in parallel to genetic signaling 10 have generated seminal follow-up studies showing the advantage of (chemical) inhibition of PFKFB3 in treating pathological angiogenesis 13, 141. Noteworthy and probably of critical importance for future EC metabolism-centric approaches is the paradigm altering concept of partial and transient glycolysis reduction. The small molecule PFKFB3 inhibitor 3-(3-pyridinyl)-1- (4-pyridinyl)-2-propen-1-one (3PO) blocks EC glycolysis in vivo only transiently and by only 40% (corresponding to the difference in glycolysis rate between quiescent and proliferating/migrating ECs), sufficient to reduce pathological angiogenesis without affecting the healthy, quiescent vasculature 13. Contrary to earlier belief, it is thus not necessary to block glycolysis permanently and completely – furthermore, this bears an increased risk for adverse effects.

Whether targeting PFKFB3 in ECs is a valuable strategy in atherosclerosis too is an unanswered question at present. In vitro, in response to the shear stress mimicking normal blood flow in mature vessels, the transcription factor KLF2 represses the expression of PFKFB3 to ensure the exact glycolytic flux required to maintain the ECs (phalanx cells) quiescent 14. Given the high prevalence of atherosclerotic plaque formation at sites where disturbed flow impacts the ECs (eg bifurcations, the aortic lesser curvature) and possibly causes reduced KLF2 expression (reviewed in ref 142), it is tempting to speculate that ECs in these athero-prone regions have increased PFKFB3 levels and subsequently higher glycolysis rates; if so, partial glycolysis inhibition as described above might also prove valuable in atherosclerosis. In the context of atherosclerosis (or cardiovascular disorders by extension), serum lipid lowering treatments have proven to be highly beneficial. The HMG-CoA reductase blocking statins, for example, are among the most often prescribed drugs world-wide 101. Interestingly, statins have additional beneficial effects such as inhibiting inflammatory processes but also a direct protective effect on the endothelium by increasing NO production (see above) 143. Even though they do mostly not outweigh the benefits, side effects such as myopathy, (possibly) increased diabetes incidence and statin intolerance, are linked to statin treatment 101. Furthermore, by blocking HMG-CoA reductase in the mevalonate pathway, statins reduce the availability of farnesyl pyrophosphate, a precursor for Coenzyme Q10, an important antioxidant and co-factor for eNOS in ECs 103, 104. Therefore, in atherosclerosis too, additional/other EC-metabolism centric approaches, focused on normalizing eNOS activity, can be of future importance. The use of vascular-targeted nano-carriers which use EC-expressed inflammation markers as landing platform are a promising strategy to deliver possible drugs to the atherosclerotic lesion 144. Although challenging to accomplish, normalizing the pathologically increased or decreased flux through a given metabolic pathway will be key to successful novel treatments.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank L. Notebaert for administrative assistance. We apologize to all colleagues whose work was not cited in this review due to space limitations and due to our attempt to cite the most recent literature.

Sources of funding

P.C. is supported by Federal Government Belgium grant (IUAP P7/03), long-term structural funding Methusalem funding by the Flemish Government, FWO grants, AXA Research Fund, ERC Advanced Research Grant and the Foundation Leducq Transatlantic Artemis Network. M.S. is supported in part by NIH grants HL053793, HL084619 and PO1 HL107205.

Non-standard abbreviations and acronyms

- α-KG

α-ketoglutarate

- (ox)LDL

(oxidized) low-density lipoprotein

- (non-)oxPPP

(non-)oxidative pentose phosphate pathway

- (V)SMC

(vascular) smooth muscle cell

- 1,3BPG

1,3-bisphosphoglycerate

- 3DG

3-deoxyglucosone

- 3PG

3-phosphoglycerate

- 3PO

3-(3-pyridinyl)-1-(4-pyridinyl)-2-propen-1-one

- AA

amino acid

- ABCA1

ATP-binding cassette protein A1

- ABCG1

ATP-binding cassette protein G1

- ACAT

acyl-CoA:cholesterol acyltransferase

- ACC

acetyl-CoA carboxylase

- acetyl-CoA

acetyl-coenzyme A

- ADMA

asymmetric dimethyl arginine

- AGE

advanced glycation end product

- AGXT2

alanine-glyoxylate aminotransferase 2

- AIBP

ApoA-I binding protein

- AMPK

adenosine monophosphate activated protein kinase

- Apo

apolipoprotein

- AR

aldose reductase

- ATP

adenosine triphosphate

- BH2

7,8-dihydrobiopterin

- BH4

tetrahydrobiopterin

- CAF

cancer associated fibroblast

- CD36

cluster of differentiation 36

- CHD

coronary heart disease

- CPT-1

carnitine palmitoyltransferase-1

- CTLA4

cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen-4

- DAG

diacylglycerol

- DDAH

dimethyl-arginine dimethyl-aminohydrolase

- DHAP

dihydroxyacetone phosphate

- DHFR

dihydrofolate reductase

- Dll4

Delta like 4

- EC

endothelial cell

- ECM

extracellular matrix

- eNOS

endothelial nitric oxide synthase

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

- ERK

extracellular signal regulated kinase

- ETC

electron transport chain

- F1,6P2

fructose-1,6-bisphosphate

- F2,6P2

fructose-2,6-bisphosphate

- F6P

fructose-6-phosphate

- FA(BP)

fatty acid (binding protein)

- FAD

flavin adenine dinucleotide

- FAO

fatty acid oxidation

- FMN

flavin mononucleotide

- G3P

glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate

- G6P

glucose-6-phosphate

- G6PDH

glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase

- GAPDH

glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- GFAT

glutamine fructose-6-phosphate amidotransferase

- GGPP

geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate

- GLS

glutaminase

- GlucN6P

glucosamine-6-phosphate

- GLUT

glucose transporter

- GS/GLUL

glutamine synthetase

- GSH

reduced glutathione

- GSSG

oxidized glutathione

- GTP

guanosine triphosphate

- GTPCH

GTP cyclohydrolase

- HBP

hexosamine biosynthesis pathway

- hCYS

homocysteine

- HDL

high-density lipoprotein

- HIF

hypoxia-inducible factor

- HMG-CoA

hydroxymethylglutaryl coenzyme A

- IL

interleukin

- iNOS

inducible nitric oxide synthase

- KLF2

Krüppel-like factor 2

- LDH

lactate dehydrogenase

- LPL

lipoprotein lipase

- MET

methionine

- mTHF

5-methyltetrahydrofolate

- MTHFR

methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase

- NADPH

nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate

- NF-κB

nuclear factor κB

- NICD

Notch intracellular domain

- nNOS

neuronal nitric oxide synthetase

- NO

nitric oxide

- OAA

oxaloacetate

- OXPHOS

oxidative phosphorylation

- PARP1

polyADP-ribose polymerase 1

- PD1

programmed death receptor 1

- PDGF-B

platelet derived growth factor B

- PDGF-Rβ

platelet derived growth factor receptor β

- PFK1

phosphofructokinase-1

- PFKFB3

6-phosphofructo-2-kinase/fructose-2,6-bisphosphatase 3

- PHD

prolyl hydroxylase domain

- PKC

protein kinase C

- PRMT

protein arginine N-methyltransferase

- R5P

ribose-5-phosphate

- RAGE

receptor for advanced glycation end products

- ROCK

Rho-associated protein kinase

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- Ru5P

ribulose-5-phosphate

- SAM

S-adenosylmethionine

- SDH

sorbitol dehydrogenase

- SLC1A5

solute carrier family 1 member 5

- SmgGDS

small GTP-binding protein GDP dissociation stimulator

- SNP

single nucleotide polymorphism

- SR-B1

scavenger receptor class B type I

- TAM

tumor associated macrophage

- TCA

tricarboxylic acid

- THF

tetrahydrofolate

- UDP-glucNAc

uridine diphosphate N-acetylglucosamine

- VEGF(R)

vascular endothelial growth factor (receptor)

Footnotes

In January 2015, the average time from submission to first decision for all original research papers submitted to Circulation Research was 14.7 days.

Disclosures

P.C. declares to be named as inventor on patent applications claiming subject matter related to the findings reviewed in this publication.

References

- 1.Carmeliet P, Jain RK. Molecular mechanisms and clinical applications of angiogenesis. Nature. 2011;473:298–307. doi: 10.1038/nature10144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tammela T, Alitalo K. Lymphangiogenesis: Molecular mechanisms and future promise. Cell. 2010;140:460–476. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Potente M, Gerhardt H, Carmeliet P. Basic and therapeutic aspects of angiogenesis. Cell. 2011;146:873–887. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.08.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mazzone M, Dettori D, Leite de Oliveira R, Loges S, Schmidt T, Jonckx B, Tian YM, Lanahan AA, Pollard P, Ruiz de Almodovar C, De Smet F, Vinckier S, Aragones J, Debackere K, Luttun A, Wyns S, Jordan B, Pisacane A, Gallez B, Lampugnani MG, Dejana E, Simons M, Ratcliffe P, Maxwell P, Carmeliet P. Heterozygous deficiency of phd2 restores tumor oxygenation and inhibits metastasis via endothelial normalization. Cell. 2009;136:839–851. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Phng LK, Gerhardt H. Angiogenesis: A team effort coordinated by notch. Developmental cell. 2009;16:196–208. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jakobsson L, Franco CA, Bentley K, Collins RT, Ponsioen B, Aspalter IM, Rosewell I, Busse M, Thurston G, Medvinsky A, Schulte-Merker S, Gerhardt H. Endothelial cells dynamically compete for the tip cell position during angiogenic sprouting. Nature Cell Biology. 2010;12:943–953. doi: 10.1038/ncb2103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gaengel K, Genove G, Armulik A, Betsholtz C. Endothelial-mural cell signaling in vascular development and angiogenesis. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology. 2009;29:630–638. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.161521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Groschner LN, Waldeck-Weiermair M, Malli R, Graier WF. Endothelial mitochondria--less respiration, more integration. Pflugers Archiv : European journal of physiology. 2012;464:63–76. doi: 10.1007/s00424-012-1085-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dagher Z, Ruderman N, Tornheim K, Ido Y. Acute regulation of fatty acid oxidation and amp-activated protein kinase in human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Circulation research. 2001;88:1276–1282. doi: 10.1161/hh1201.092998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Bock K, Georgiadou M, Schoors S, Kuchnio A, Wong BW, Cantelmo AR, Quaegebeur A, Ghesquiere B, Cauwenberghs S, Eelen G, Phng LK, Betz I, Tembuyser B, Brepoels K, Welti J, Geudens I, Segura I, Cruys B, Bifari F, Decimo I, Blanco R, Wyns S, Vangindertael J, Rocha S, Collins RT, Munck S, Daelemans D, Imamura H, Devlieger R, Rider M, Van Veldhoven PP, Schuit F, Bartrons R, Hofkens J, Fraisl P, Telang S, Deberardinis RJ, Schoonjans L, Vinckier S, Chesney J, Gerhardt H, Dewerchin M, Carmeliet P. Role of pfkfb3-driven glycolysis in vessel sprouting. Cell. 2013;154:651–663. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.06.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mertens S, Noll T, Spahr R, Krutzfeldt A, Piper HM. Energetic response of coronary endothelial cells to hypoxia. The American journal of physiology. 1990;258:H689–694. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1990.258.3.H689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ghesquiere B, Wong BW, Kuchnio A, Carmeliet P. Metabolism of stromal and immune cells in health and disease. Nature. 2014;511:167–176. doi: 10.1038/nature13312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schoors S, De Bock K, Cantelmo AR, Georgiadou M, Ghesquiere B, Cauwenberghs S, Kuchnio A, Wong BW, Quaegebeur A, Goveia J, Bifari F, Wang X, Blanco R, Tembuyser B, Cornelissen I, Bouche A, Vinckier S, Diaz-Moralli S, Gerhardt H, Telang S, Cascante M, Chesney J, Dewerchin M, Carmeliet P. Partial and transient reduction of glycolysis by pfkfb3 blockade reduces pathological angiogenesis. Cell metabolism. 2014;19:37–48. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2013.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Doddaballapur A, Michalik KM, Manavski Y, Lucas T, Houtkooper RH, You X, Chen W, Zeiher AM, Potente M, Dimmeler S, Boon RA. Laminar shear stress inhibits endothelial cell metabolism via klf2-mediated repression of pfkfb3. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology. 2015;35:137–145. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.114.304277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Slawson C, Copeland RJ, Hart GW. O-glcnac signaling: A metabolic link between diabetes and cancer? Trends in biochemical sciences. 2010;35:547–555. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2010.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Benedito R, Roca C, Sorensen I, Adams S, Gossler A, Fruttiger M, Adams RH. The notch ligands dll4 and jagged1 have opposing effects on angiogenesis. Cell. 2009;137:1124–1135. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vaisman N, Gospodarowicz D, Neufeld G. Characterization of the receptors for vascular endothelial growth factor. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1990;265:19461–19466. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Merchan JR, Kovacs K, Railsback JW, Kurtoglu M, Jing Y, Pina Y, Gao N, Murray TG, Lehrman MA, Lampidis TJ. Antiangiogenic activity of 2-deoxy-d-glucose. PloS one. 2010;5:e13699. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Riganti C, Gazzano E, Polimeni M, Aldieri E, Ghigo D. The pentose phosphate pathway: An antioxidant defense and a crossroad in tumor cell fate. Free radical biology & medicine. 2012;53:421–436. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vizan P, Sanchez-Tena S, Alcarraz-Vizan G, Soler M, Messeguer R, Pujol MD, Lee WN, Cascante M. Characterization of the metabolic changes underlying growth factor angiogenic activation: Identification of new potential therapeutic targets. Carcinogenesis. 2009;30:946–952. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgp083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang Z, Apse K, Pang J, Stanton RC. High glucose inhibits glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase via camp in aortic endothelial cells. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2000;275:40042–40047. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007505200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Elmasri H, Karaaslan C, Teper Y, Ghelfi E, Weng M, Ince TA, Kozakewich H, Bischoff J, Cataltepe S. Fatty acid binding protein 4 is a target of vegf and a regulator of cell proliferation in endothelial cells. FASEB journal : official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. 2009;23:3865–3873. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-134882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carracedo A, Cantley LC, Pandolfi PP. Cancer metabolism: Fatty acid oxidation in the limelight. Nature reviews. Cancer. 2013;13:227–232. doi: 10.1038/nrc3483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jeon SM, Chandel NS, Hay N. Ampk regulates nadph homeostasis to promote tumour cell survival during energy stress. Nature. 2012;485:661–665. doi: 10.1038/nature11066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Iso T, Maeda K, Hanaoka H, Suga T, Goto K, Syamsunarno MR, Hishiki T, Nagahata Y, Matsui H, Arai M, Yamaguchi A, Abumrad NA, Sano M, Suematsu M, Endo K, Hotamisligil GS, Kurabayashi M. Capillary endothelial fatty acid binding proteins 4 and 5 play a critical role in fatty acid uptake in heart and skeletal muscle. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology. 2013;33:2549–2557. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.113.301588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hagberg CE, Falkevall A, Wang X, Larsson E, Huusko J, Nilsson I, van Meeteren LA, Samen E, Lu L, Vanwildemeersch M, Klar J, Genove G, Pietras K, Stone-Elander S, Claesson-Welsh L, Yla-Herttuala S, Lindahl P, Eriksson U. Vascular endothelial growth factor b controls endothelial fatty acid uptake. Nature. 2010;464:917–921. doi: 10.1038/nature08945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kivela R, Bry M, Robciuc MR, Rasanen M, Taavitsainen M, Silvola JM, Saraste A, Hulmi JJ, Anisimov A, Mayranpaa MI, Lindeman JH, Eklund L, Hellberg S, Hlushchuk R, Zhuang ZW, Simons M, Djonov V, Knuuti J, Mervaala E, Alitalo K. Vegf-b-induced vascular growth leads to metabolic reprogramming and ischemia resistance in the heart. EMBO molecular medicine. 2014;6:307–321. doi: 10.1002/emmm.201303147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Davies BS, Beigneux AP, Barnes RH, 2nd, Tu Y, Gin P, Weinstein MM, Nobumori C, Nyren R, Goldberg I, Olivecrona G, Bensadoun A, Young SG, Fong LG. Gpihbp1 is responsible for the entry of lipoprotein lipase into capillaries. Cell metabolism. 2010;12:42–52. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2010.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tousoulis D, Kampoli AM, Tentolouris C, Papageorgiou N, Stefanadis C. The role of nitric oxide on endothelial function. Current vascular pharmacology. 2012;10:4–18. doi: 10.2174/157016112798829760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.DeBerardinis RJ, Cheng T. Q’s next: The diverse functions of glutamine in metabolism, cell biology and cancer. Oncogene. 2010;29:313–324. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lohmann R, Souba WW, Bode BP. Rat liver endothelial cell glutamine transporter and glutaminase expression contrast with parenchymal cells. The American journal of physiology. 1999;276:G743–750. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1999.276.3.G743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wu G, Haynes TE, Yan W, Meininger CJ. Presence of glutamine:Fructose-6-phosphate amidotransferase for glucosamine-6-phosphate synthesis in endothelial cells: Effects of hyperglycaemia and glutamine. Diabetologia. 2001;44:196–202. doi: 10.1007/s001250051599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Unterluggauer H, Mazurek S, Lener B, Hutter E, Eigenbrodt E, Zwerschke W, Jansen-Durr P. Premature senescence of human endothelial cells induced by inhibition of glutaminase. Biogerontology. 2008;9:247–259. doi: 10.1007/s10522-008-9134-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gao P, Tchernyshyov I, Chang TC, Lee YS, Kita K, Ochi T, Zeller KI, De Marzo AM, Van Eyk JE, Mendell JT, Dang CV. C-myc suppression of mir-23a/b enhances mitochondrial glutaminase expression and glutamine metabolism. Nature. 2009;458:762–765. doi: 10.1038/nature07823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wise DR, DeBerardinis RJ, Mancuso A, Sayed N, Zhang XY, Pfeiffer HK, Nissim I, Daikhin E, Yudkoff M, McMahon SB, Thompson CB. Myc regulates a transcriptional program that stimulates mitochondrial glutaminolysis and leads to glutamine addiction. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008;105:18782–18787. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810199105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hu W, Zhang C, Wu R, Sun Y, Levine A, Feng Z. Glutaminase 2, a novel p53 target gene regulating energy metabolism and antioxidant function. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107:7455–7460. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1001006107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Strasser GA, Kaminker JS, Tessier-Lavigne M. Microarray analysis of retinal endothelial tip cells identifies cxcr4 as a mediator of tip cell morphology and branching. Blood. 2010;115:5102–5110. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-07-230284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Amelio I, Cutruzzola F, Antonov A, Agostini M, Melino G. Serine and glycine metabolism in cancer. Trends in biochemical sciences. 2014;39:191–198. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2014.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mishra RC, Tripathy S, Desai KM, Quest D, Lu Y, Akhtar J, Gopalakrishnan V. Nitric oxide synthase inhibition promotes endothelium-dependent vasodilatation and the antihypertensive effect of l-serine. Hypertension. 2008;51:791–796. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.099598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mishra RC, Tripathy S, Quest D, Desai KM, Akhtar J, Dattani ID, Gopalakrishnan V. L-serine lowers while glycine increases blood pressure in chronic l-name-treated and spontaneously hypertensive rats. J Hypertens. 2008;26:2339–2348. doi: 10.1097/hjh.0b013e328312c8a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tibbetts AS, Appling DR. Compartmentalization of mammalian folate-mediated one-carbon metabolism. Annual review of nutrition. 2010;30:57–81. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.012809.104810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fisslthaler B, Fleming I. Activation and signaling by the amp-activated protein kinase in endothelial cells. Circulation research. 2009;105:114–127. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.201590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li J, McCullough LD. Effects of amp-activated protein kinase in cerebral ischemia. Journal of cerebral blood flow and metabolism : official journal of the International Society of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism. 2010;30:480–492. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2009.255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Eijkelenboom A, Burgering BM. Foxos: Signalling integrators for homeostasis maintenance. Nature reviews. Molecular cell biology. 2013;14:83–97. doi: 10.1038/nrm3507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mihaylova MM, Shaw RJ. The ampk signalling pathway coordinates cell growth, autophagy and metabolism. Nature cell biology. 2011;13:1016–1023. doi: 10.1038/ncb2329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pollizzi KN, Powell JD. Integrating canonical and metabolic signalling programmes in the regulation of t cell responses. Nature reviews. Immunology. 2014;14:435–446. doi: 10.1038/nri3701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Parra-Bonilla G, Alvarez DF, Al-Mehdi AB, Alexeyev M, Stevens T. Critical role for lactate dehydrogenase a in aerobic glycolysis that sustains pulmonary microvascular endothelial cell proliferation. American journal of physiology. Lung cellular and molecular physiology. 2010;299:L513–522. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00274.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tang X, Luo YX, Chen HZ, Liu DP. Mitochondria, endothelial cell function, and vascular diseases. Frontiers in physiology. 2014;5:175. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2014.00175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ohga N, Ishikawa S, Maishi N, Akiyama K, Hida Y, Kawamoto T, Sadamoto Y, Osawa T, Yamamoto K, Kondoh M, Ohmura H, Shinohara N, Nonomura K, Shindoh M, Hida K. Heterogeneity of tumor endothelial cells: Comparison between tumor endothelial cells isolated from high- and low-metastatic tumors. The American journal of pathology. 2012;180:1294–1307. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.11.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Aird WC. Endothelial cell heterogeneity. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in medicine. 2012;2:a006429. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a006429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Drummond GR, Sobey CG. Endothelial nadph oxidases: Which nox to target in vascular disease? Trends in endocrinology and metabolism: TEM. 2014;25:452–463. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2014.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Du X, Matsumura T, Edelstein D, Rossetti L, Zsengeller Z, Szabo C, Brownlee M. Inhibition of gapdh activity by poly(adp-ribose) polymerase activates three major pathways of hyperglycemic damage in endothelial cells. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:1049–1057. doi: 10.1172/JCI18127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lorenzi M. The polyol pathway as a mechanism for diabetic retinopathy: Attractive, elusive, and resilient. Exp Diabetes Res. 2007;2007:61038. doi: 10.1155/2007/61038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wautier JL, Schmidt AM. Protein glycation: A firm link to endothelial cell dysfunction. Circ Res. 2004;95:233–238. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000137876.28454.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Federici M, Menghini R, Mauriello A, Hribal ML, Ferrelli F, Lauro D, Sbraccia P, Spagnoli LG, Sesti G, Lauro R. Insulin-dependent activation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase is impaired by o-linked glycosylation modification of signaling proteins in human coronary endothelial cells. Circulation. 2002;106:466–472. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000023043.02648.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Das Evcimen N, King GL. The role of protein kinase c activation and the vascular complications of diabetes. Pharmacological research : the official journal of the Italian Pharmacological Society. 2007;55:498–510. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2007.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nishikawa T, Edelstein D, Du XL, Yamagishi S, Matsumura T, Kaneda Y, Yorek MA, Beebe D, Oates PJ, Hammes HP, Giardino I, Brownlee M. Normalizing mitochondrial superoxide production blocks three pathways of hyperglycaemic damage. Nature. 2000;404:787–790. doi: 10.1038/35008121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Brownlee M. The pathobiology of diabetic complications: A unifying mechanism. Diabetes. 2005;54:1615–1625. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.6.1615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Goldin A, Beckman JA, Schmidt AM, Creager MA. Advanced glycation end products: Sparking the development of diabetic vascular injury. Circulation. 2006;114:597–605. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.621854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ott C, Jacobs K, Haucke E, Navarrete Santos A, Grune T, Simm A. Role of advanced glycation end products in cellular signaling. Redox biology. 2014;2:411–429. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2013.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Boyle JJ. Macrophage activation in atherosclerosis: Pathogenesis and pharmacology of plaque rupture. Current vascular pharmacology. 2005;3:63–68. doi: 10.2174/1570161052773861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Isoda K, Folco EJ, Shimizu K, Libby P. Age-bsa decreases abcg1 expression and reduces macrophage cholesterol efflux to hdl. Atherosclerosis. 2007;192:298–304. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2006.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chuah YK, Basir R, Talib H, Tie TH, Nordin N. Receptor for advanced glycation end products and its involvement in inflammatory diseases. International journal of inflammation. 2013;2013:403460. doi: 10.1155/2013/403460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hu P, Lai D, Lu P, Gao J, He H. Erk and akt signaling pathways are involved in advanced glycation end product-induced autophagy in rat vascular smooth muscle cells. International journal of molecular medicine. 2012;29:613–618. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2012.891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.San Martin A, Foncea R, Laurindo FR, Ebensperger R, Griendling KK, Leighton F. Nox1-based nadph oxidase-derived superoxide is required for vsmc activation by advanced glycation end-products. Free Radic Biol Med. 2007;42:1671–1679. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sakata N, Meng J, Takebayashi S. Effects of advanced glycation end products on the proliferation and fibronectin production of smooth muscle cells. Journal of atherosclerosis and thrombosis. 2000;7:169–176. doi: 10.5551/jat1994.7.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tanikawa T, Okada Y, Tanikawa R, Tanaka Y. Advanced glycation end products induce calcification of vascular smooth muscle cells through rage/p38 mapk. J Vasc Res. 2009;46:572–580. doi: 10.1159/000226225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wang Y, Zhang ZY, Chen XQ, Wang X, Cao H, Liu SW. Advanced glycation end products promote human aortic smooth muscle cell calcification in vitro via activating nf-kappab and down-regulating igf1r expression. Acta pharmacologica Sinica. 2013;34:480–486. doi: 10.1038/aps.2012.166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wu G, Haynes TE, Li H, Yan W, Meininger CJ. Glutamine metabolism to glucosamine is necessary for glutamine inhibition of endothelial nitric oxide synthesis. The Biochemical journal. 2001;353:245–252. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3530245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Koziel A, Woyda-Ploszczyca A, Kicinska A, Jarmuszkiewicz W. The influence of high glucose on the aerobic metabolism of endothelial ea.Hy926 cells. Pflugers Archiv : European journal of physiology. 2012;464:657–669. doi: 10.1007/s00424-012-1156-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Qi L, Qi Q, Prudente S, Mendonca C, Andreozzi F, di Pietro N, Sturma M, Novelli V, Mannino GC, Formoso G, Gervino EV, Hauser TH, Muehlschlegel JD, Niewczas MA, Krolewski AS, Biolo G, Pandolfi A, Rimm E, Sesti G, Trischitta V, Hu F, Doria A. Association between a genetic variant related to glutamic acid metabolism and coronary heart disease in individuals with type 2 diabetes. JAMA. 2013;310:821–828. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.276305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ido Y, Carling D, Ruderman N. Hyperglycemia-induced apoptosis in human umbilical vein endothelial cells: Inhibition by the amp-activated protein kinase activation. Diabetes. 2002;51:159–167. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.1.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Yamagishi SI, Edelstein D, Du XL, Kaneda Y, Guzman M, Brownlee M. Leptin induces mitochondrial superoxide production and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 expression in aortic endothelial cells by increasing fatty acid oxidation via protein kinase a. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2001;276:25096–25100. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007383200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Du X, Edelstein D, Obici S, Higham N, Zou MH, Brownlee M. Insulin resistance reduces arterial prostacyclin synthase and enos activities by increasing endothelial fatty acid oxidation. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2006;116:1071–1080. doi: 10.1172/JCI23354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Richards OC, Raines SM, Attie AD. The role of blood vessels, endothelial cells, and vascular pericytes in insulin secretion and peripheral insulin action. Endocrine reviews. 2010;31:343–363. doi: 10.1210/er.2009-0035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lesniewski LA, Donato AJ, Behnke BJ, Woodman CR, Laughlin MH, Ray CA, Delp MD. Decreased no signaling leads to enhanced vasoconstrictor responsiveness in skeletal muscle arterioles of the zdf rat prior to overt diabetes and hypertension. American journal of physiology. Heart and circulatory physiology. 2008;294:H1840–1850. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00692.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kawashima S. Malfunction of vascular control in life-style related diseases: Endothelial nitric oxide (no) synthase/no system in atherosclerosis. Journal of Parmacology Science. 2004;96:411–419. doi: 10.1254/jphs.fmj04006x6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Moncada S, Higgs EA, Hodson HF, Knowles RG, Lopez-Jaramillo P, McCall T, Palmer RM, Radomski MW, Rees DD, Schulz R. The l-arginine:Nitric oxide pathway. Journal of Cardiovascular Pharmacology. 1991;17:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Moncada S, Palmer RM, Higgs EA. Nitric oxide: Physiology, pathophysiology, and pharmacology. Pharmacol Rev. 1991;43:109–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Nathan C, Xie Q. Nitric oxide synthases: Roles, tolls, and controls. Cell. 1994;78:915–918. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90266-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Davignon J, Ganz P. Role of endothelial dysfunction in atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2004;109:27–32. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000131515.03336.f8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kopincova J, Puzserova A, Bernatova I. L-name in the cardiovascular system - nitric oxide synthase activator? Pharmacological Reports. 2012;64:511–520. doi: 10.1016/s1734-1140(12)70846-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Stroes E, Hijmering M, van Zandvoort M, Wever R, Rabelink TJ, van Faassen EE. Origin of superoxide production by endothelial nitric oxide synthase. FEBS Letters. 1998;438:161–164. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)01292-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Castillo L, Chapman TE, Sanchez M, Yu Y, Burke JF, Ajami AM, Vogt J, Young VR. Plasma arginine and citrulline kinestics in adults given adequate and arginine-free diets. PNAS. 1993;90:7749–7753. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.16.7749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Boger RH, Bode-Boger SM, Szuba A, Tsao PS, Chan JR, Tangphao O, Blaschke TF, Cooke JP. Asymmetric dimethylarginine (adma): A novel risk factor for endothelial dysfunction: Its role in hypercholesterolemia. Circulation. 1998;98:1842–1847. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.18.1842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Cooke JP. Does adma cause endothelial dysfunction? Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2000;20:2032–2037. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.20.9.2032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Boger RH. Asymmetric dimethylarginine: Understanding the physiology, genetics, and clinical relevance of this novel biomarker. Proceedings of the 4th international symposium on adma. Pharmacol Res. 2009;60:447. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2009.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Leiper JM, Santa Maria J, Chubb A, MacAllister RJ, Charles IG, Whitley GS, Vallance P. Identification of two human dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolases with distinct tissue distributions and homology with microbial arginine deiminases. Biochem J. 1999;343(Pt 1):209–214. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Wilcox CS. Asymmetric dimethylarginine and reactive oxygen species: Unwelcome twin visitors to the cardiovascular and kidney disease tables. Hypertension. 2012;59:375–381. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.187310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]