Abstract

Proteasome assembly is a complex process, requiring 66 subunits distributed over several subcomplexes to associate in a coordinated fashion. Ten proteasome-specific chaperones have been identified that assist in this process. For two of these, the Pba1-Pba2 dimer, it is well established that they only bind immature core particles (CP) in vivo. In contrast, the regulatory particle (RP) utilizes the same binding surface but only interacts with the mature CP in vivo. It is unclear how these binding events are regulated. Here, we show that Pba1-Pba2 binds tightly to immature CP, preventing RP binding. Changes in the CP that occur upon maturation significantly reduce its affinity for Pba1-Pba2, enabling the RP to displace the chaperone. Mathematical modeling indicates that this “affinity switch” mechanism has likely evolved to improve assembly efficiency by preventing the accumulation of stable, non-productive intermediates. Our work thus provides mechanistic insights into a crucial step in proteasome biogenesis.

Introduction

The selective and timely degradation of polypeptide chains in the cell is important for overall protein homeostasis as well as an integral part of many cellular processes. Many proteins destined for degradation undergo a modification where ubiquitin is covalently attached to lysine residues. The ubiquitin-tag targets substrates to the proteasome, where they are deubiquitinated, unfolded, and hydrolyzed into short peptide fragments. The proteasome itself is a complex molecular machine, containing 66 subunits that must assemble into a 2.5 MDa complex. The subunits are broadly organized into a regulatory particle (RP or 19S, also called PA700 in mammals) that is responsible for substrate recognition, deubiquitination, and unfolding, and a proteolytically active core particle (CP or 20S)1. The CP is formed by four stacked rings, each consisting of seven unique α or seven unique β subunits, in an α1–7β1–7β1–7α1–7 arrangement. During CP maturation, the β1 (Pre3), β2 (Pup1), and β5 (Pre2) subunits become proteolytically active through an autocatalytic process that removes propeptides present within these subunits. This occurs when two half CPs, often referred to as 15S or immature CP, dimerize. In yeast, five assembly chaperones, Ump1, Pba1 (also called Poc1), Add66 (also called Pba2 or Poc2), Irc25 (also called Pba3, POC3, or DMP2), and Poc4 (also called Pba4 or Dmp1) have been found to bind the CP prior to its maturation (reviewed in 2). Here, we will refer to these factors as Ump1 and Pba1 to Pba4. Each of these has a human ortholog, known as POMP, and PSMG1 to PSMG4 (also called PAC1 to PAC4). Pba3 and Pba4 form a dimer that binds to β5 (Pup2) and promotes proper α-ring assembly3-5. The Pba3-Pba4 dimer must dissociate before the β4 (Pre1) subunit can join the complex due to extensive steric clashes with this subunit4. The chaperone Ump1 associates with immature CP after the α-ring forms. Upon dimerization of half CPs, Ump1 is retained inside the CP and is degraded as part of the maturation process6. Pba1 and Pba2 form a dimer that, like Ump1, is present on the half CP, but binds on the outside of the CP cylinder base7,8. Although Pba1-Pba2 has been shown to prevent α-ring dimerization in mammals9, its cellular functions remain poorly characterized.

While the CP can be found in the cell by itself (a.k.a. the free CP), in most cases it acts in consortium with a set of associated factors10,11. In yeast the RP, Blm10, and Pba1-Pba2 can all bind to the ends of the CP cylinder, although the later has only been shown to bind mature CP in vitro8,12-14. Blm10 (PSME4/PA200 in humans) has been proposed to function in CP maturation15,16, CP localization17, and activation of protein degradation18-20. In recent years it has become clear that these interaction partners all utilize a similar mechanism where C-terminal tails dock into pockets located at the interface between CP α-subunits, often facilitated by a conserved C-terminal HbYX-motif8,12,19,21-24. The C-terminal tail of Pba1 docks into the α5-α6 (Pup2-Pre5) pocket and the Pba2 tail in the α6-α7 (Pre5-Pre10) pocket8. Interestingly, the α5-α6 pocket is also utilized by Blm10 and the RP subunits Rpt1 and Rpt5, while the α6-α7 pocket can associate with Rpt4 and Rpt512-14,24. This suggests that the RP, Blm10, and Pba1-Pba2 compete with one another for CP binding.

Since the full α-ring forms early in assembly, one would expect a priori that any CP binding partner would interact with both mature and immature CPs. While Blm10 can indeed associate with both forms of the CP, the RP is only found associated with mature particles, and Pba1-Pba2 only binds immature CP in vivo9,16,25-27. These observations imply that the binding of these factors to the CP is tightly regulated. The RP chaperones Nas2, Nas6, Hsm3, and Rpn14 (known in humans as PSMD9/p27, PSMD10/gankyrin, PSMD5/S5b, and PAAF1/Rpn14 respectively) are one example of this regulation: they all have the capacity to interfere with the association of immature RP subcomplexes and the CP28-34. Despite intense research over the last decade, however, surprisingly little is known about the mechanisms that control the interaction between the CP and its binding partners.

In this work, we demonstrate that the Pba1-Pba2 dimer associates tightly with immature CP and prevents them from associating with the RP. Upon CP maturation, however, the affinity of Pba1-Pba2 for the CP changes dramatically, presumably due to a subtle conformational change in the α-ring that impacts the Pba1-Pba2 binding surface. Consistent with this we observed that the Pba2 tail, which plays a negligible role in mature CP binding, contributes substantially to immature CP binding. Mathematical models of proteasome assembly demonstrated that this “affinity switch” is crucial for achieving high yields of functional molecules. Finally, our results reveal that Pba1-Pba2 is also required for efficient incorporation of α5 and α6 into the immature CP.

Results

The Pba1 and Pba2 complex prevents RP binding

As mentioned above, Pba1-Pba2 and Blm10 likely compete with each other for binding to the CP α ring. Consistent with this idea, upon purification of proteasomes from pba1Δ, pba2Δ or pba1Δpba2Δ yeast strains we observed increased levels of Blm10 (Fig. 1a, 1b, and Supplementary Figure 1a). However, in vivo Pba1-Pba2 is normally only found on the immature CP, and it has been postulated that one function of Pba1-Pba2 could be to prevent RP from binding to immature CP8,9,35,36. To test this hypothesis, we first affinity-purified immature CP using TAP-tagged Ump1 (Fig. 1c and 1d). Mass spectrometry analyses confirmed that these purifications contained all seven α subunits in addition to β1 to β5, Pba1, Pba2 and Ump1 (Supplementary Table 1). β6 (Pre7) and β7 (Pre4) were undetectable, as has been observed before37. The presence of Pba1-Pba2 was also confirmed by immunoblotting (Fig. 1c and Supplementary Figure 1b). Propeptides for β1, β2, and β5 were detected by immunoblotting or mass spectrometry (Fig. 1c and Supplementary Table 1). Taken together, these data indicate we purified a form of CP that has not matured yet.

Figure 1. Pba1-Pba2 prevents RP association with immature CP.

(a) Proteasomes were purified from indicated strains, resolved by SDS-PAGE, and stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue (CBB). (b) Native gel analysis of samples from (A) stained in gel with the proteasome substrate suc-LLVY-AMC (left) or stained with CBB. (c) 26S proteasome or immature CP were affinity-purified using ProA-tagged β4 or TAP-tagged Ump1 respectively. Purified complexes were resolved on SDS-PAGE and stained with CBB (top) or immunoblotted for Pba1-Pba2, indicated proteasome subunits (CP indicates core and RP indicates regulatory particle subunits), and Ecm29. The asterisk marks a non-specific band. (d) 26S proteasome and CP were purified using standard protocols. Immature CP was purified and washed with buffers containing the indicated NaCl concentrations. Samples were resolved on a native gel and stained with either suc-LLVY-AMC (top) or with CBB (bottom).

RP was not detected above background levels in purifications of immature CP when assessed using several RP specific antibodies (Fig. 1c). To understand how the presence of Pba1-Pba2 might impact interactions of RP with the immature CP, we deleted PBA1. The deletion of PBA1 resulted in the absence of both Pba1 and Pba2 from immature CP, and the appearance of the RP (Fig. 1c). Thus, upon deletion of Pba1, the surface of the α ring becomes available for interaction with RP. Particularly striking was the presence of Ecm29 in this deletion background; Ecm29 is a proteasome-associated protein that only associates with RP-CP species and not free RP or free CP38,39. It has been found recruited to mutant proteasome forms29,40, potentially indicating specific recruitment on these samples where RP associates prematurely with CP.

Previously, it has been shown that Blm10 associates with both mature CP17,26,27,38 and immature CP15,16,26. We consistently observed higher levels of Blm10 on immature CP purified from a pba1Δ strain compared to wildtype (Fig. 1c and Supplementary Figure 1c). The deletion of BLM10 together with PBA1 caused a modest further increase of RP binding to immature CP, consistent with the fact that the RP and Blm10 compete for CP binding. Interestingly, a deletion of BLM10 in strains that contain functional Pba1-Pba2 did not cause the RP to associate with immature CP (Supplementary Figure 1c), suggesting that it is mainly the Pba1-Pba2 dimer that blocks association of RP with immature CP.

Analysis of immature CP on native gel shows a distinct band that migrates faster than CP and lacks hydrolytic activity (Fig. 1d). The deletion of PBA1 resulted in a smear instead of a well-resolved species (Fig. 1d lower panel). This smearing is likely caused by different factors associated with the immature CP in the absence of Pba1-Pba2, since including a washing step with high salt resulted in a more distinct band on native gel (Fig. 1d lower panel). The band does not migrate similar to wildtype immature CP, which might be caused by the absence of Pba1-Pba2 or a different composition of the immature CP (Fig. 1c and below). Our results thus indicate that the Pba1-Pba2 dimer shields the immature CP from other factors that can interact with the α-ring surface.

RP readily displaces Pba1 and Pba2 from mature CP

Crystal structures of Blm10 or Pba1-Pba2 bound to the CP and cryoEM structures of RP-CP complexes show that they bind with the CP exclusively through the α ring8,12-14. Since both Ump1-bound immature CP (Supplementary Table 1) and mature CP have a complete α1–7 ring, it is unclear what drives the difference in binding behavior observed between mature CP and immature CP. An attractive mechanism that has been proposed posits that Pba1-Pba2 binds to immature CP, but upon maturation, Pba1-Pba2 is degraded, which enables the formation of RP-CP complexes. This model is supported by the observation that, upon overexpression of a flag-tagged version of the human orthologs PSMG1 (PAC1) or PSMG2 (PAC2), the flag-tagged protein is unstable in Hela cells9. On the other hand, for the yeast orthologs no detectable degradation of Pba1-Pba2 by the mature CP has been observed in vitro7,8.

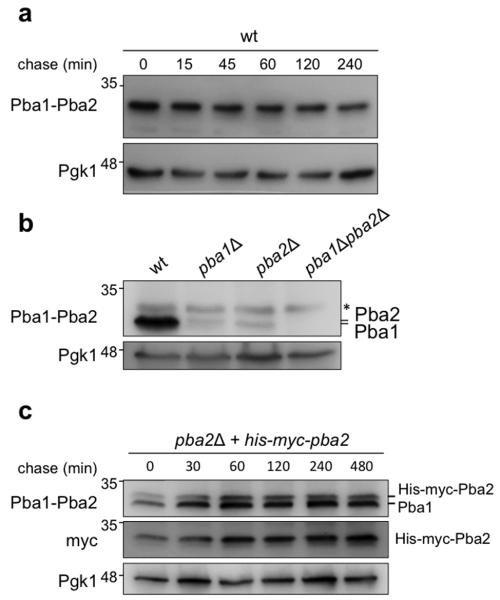

To test the stability of Pba1-Pba2 in vivo, we conducted chase experiments using an antibody that recognizes endogenous Pba1-Pba2 (Fig. 2a). These data suggested that the Pba1-Pba2 dimer is stable. To address the possibility that one of the two subunits is unstable, we next determined steady state levels of Pba1 and Pba2 in the pba2Δ and pba1Δ strains respectively. Here, a subtle difference in migration between the two proteins can be observed, indicating the antibody recognizes both endogenous Pba1 and endogenous Pba2 (Fig. 2b). The strongly reduced signal upon deletion of PBA1 or PBA2 might indicate that subunits incapable of forming dimers are subject to degradation in a process unrelated to CP maturation. This finding could potentially explain perceived differences between the yeast and mammalian systems9. Finally, we also reintroduced a His-Myc-tagged version of Pba2 in a pba2Δ background using a CEN plasmid and the endogenous promoter to prevent overexpression. Chase experiments with the later strain also showed both subunits are stable (Fig. 2c). In sum, our findings indicate that Pba1-Pba2 is not degraded as part of the CP maturation process in yeast.

Figure 2. Pba1 and Pba2 are stable.

(a) Cyclohexamide chase of wildtype using antibodies that recognize endogenous Pba1-Pba2. 100 μg ml−1 of cyclohexamide was added to logarithmically growing samples at t=0. Samples were collected at indicated times and lysed in SDS sample buffer. Immunoblots show levels of Pba1-Pba2 with Pgk1 as a loading control. Pba1-Pba2 has a long half-life inconsistent with the previously proposed model that Pba1-Pba2 is degraded during the assembly process. (b) Steady state levels of Pba1-Pba2 in total lysate. (c) Cyclohexamide chase as in (a) but from a strain that expresses His-Myc-tagged Pba1 from a CEN plasmid under its own promoter.

Since CP does not degrade Pba1-Pba2, RP must be able to displace it directly or with the help of other factors. Previous work using surface plasmon resonance had shown that the interaction between mature CP and Pba1-Pba2 is salt-labile8. We also observe that this interaction can be disrupted with low salt concentrations when we reconstituted E. coli purified Pba1-Pba2 onto resin-bound CP purified from yeast (Fig. 3a). Using bio-layer interferometry, we measured a KD of ~ 1 μM for Pba1-Pba2 with mature CP in 50 mM NaCl (Supplementary Figure 2a), which is similar to the 3 μM reported by Stadtmueller et al. under physiological salt concentrations8. Considering the reported nanomolar range affinities between the RP subunit containing complexes and CP21,30, these findings suggest that the RP will likely displace Pba1-Pba2 from the mature CP.

Figure 3. CP undergoes affinity switch upon maturation.

(a) Affinity-resin bound purified CP was reconstituted with heterologously expressed His-tagged Pba1-Pba2 dimer. Samples were washed with buffer containing the indicated NaCl concentrations. Next, samples were resolved on SDS-PAGE and stained with CBB or immunoblotted for the indicated proteins. (b) YFP-tagged CP was first reconstituted with 5 fold molar excess of Pba1-Pba2 and challenged with different amounts of purified RP (molar excess over CP indicated). Samples were resolved on a native gel to determine complex composition in samples: Top panel, proteolytic active complexes were visualized using in gel suc-LLVY-AMC hydrolytic activity assay. Middle panel, native gel was immunoblotted for the RP subunit Rpn1. Lower panel, native gel was analyzed for YFP signal. (c-f) Immature CP or 26S proteasome from wildtype or indicated strains were purified, split into different samples and washed with buffer containing the indicated NaCl concentrations. Samples were resolved on SDS-PAGE and stained with CBB or immunoblotted for indicated proteins. The asterisk indicates an IgG resin-derived band.

To further test this we developed an in vitro reconstitution assay. First, we combined mature CP with increasing ratios of Pba1-Pba2 to determine the stoichiometry of binding on native gel. Pba1-Pba2 binds to the CP, but does not cause a mobility shift (Supplementary Figure 2b). Since a five fold excess of Pba1-Pba2 showed maximum CP binding, we challenged reconstitutions with that ratio of Pba1-Pba2 to CP with increasing amounts of RP (Fig. 3b). We found that the RP associates with the CP starting at low concentrations where Pba1-Pba2 is in 20 fold excess over RP. This indicates that the RP can readily replace Pba1-Pba2 bound to mature CP. These analyses are complicated by a small amount of active RP2-CP that co-purifies with our RP preparations (38 and Fig. 3b lane 2). However, looking at the singly-capped RP-CP or visualizing exclusively the reconstituted CP by utilizing YFP-tagged CP (Fig. 3b lowest panel), we know the RP is reconstituted onto Pba1-Pba2-CP complexes. These data suggest that Pba1-Pba2 bound to mature CP cannot prevent RP association. Hence, there is no need for Pba1-Pba2 degradation to produce RP-CP complexes.

A switch in affinity upon CP maturation

We hypothesized that a specific mechanism must exist that ensures Pba1-Pba2 cannot be replaced by RP when bound to immature CP. This could involve regulatory proteins, like the RP chaperones that associate with RP complexes. However, those chaperones cannot fully prevent RP-immature CP association as we observed RP binding in pba1Δ cells (Fig. 1c). As an alternative mechanism, we envisioned a conformational change in the α ring upon maturation that changes the binding surface between the CP and associated proteins. In general, the CP has more structural plasticity then has been appreciated41. More specifically, during the final steps of CP maturation, β7 is incorporated, immature CP dimerizes, autoproteolytic cleavage activates the three active sites (β1, β2 and β5), and Ump1 is degraded2. The β7 subunit is in direct contact with the α subunits that bind to Pba1-Pba2, α6 and α7 8, providing a direct opportunity to induce a conformational change in the α ring. Alternatively, autoproteolytic activation might provide a trigger that induces a conformational change in CP, as modification of active sites has been shown to change properties of the α-ring38,42.

To test for differences in binding behavior between mature and immature CP, we characterized the salt dependence of several different interactions. First, we used TAP-tagged Ump1 to purify immature CP associated with endogenous Pba1-Pba2. Here, even washes with buffers containing 1M NaCl washed off very little of the Pba1-Pba2 complex from immature CP (Fig. 3c). This is in sharp contrast to the Pba1-Pba2 association with mature CP, which is highly salt labile (Fig. 3a and 8). Next, to test if the RP also shows a change in binding behavior, we purified immature CP from the pba1Δ blm10Δ strain and exposed it to washes with different salt concentrations. In these samples, the RP consistently washes off in buffers containing 100 mM NaCl (Fig. 3d), while 250 to 500 mM NaCl is required to disrupt the binding between RP and mature CP (Fig. 3e and 39). These data suggest that the immature CP has a high affinity for Pba1-Pba2 and a low affinity for the RP. Upon maturation, the affinities are reversed and the RP has a much higher affinity for the mature CP than Pba1-Pba2. For RP binding to the immature CP we cannot exclude that the reduced binding is due to differences in immature CP composition upon PBA1 deletion (see below). However, in reconstitution assays we were unable to expel Pba1-Pba2 from normal immature CP, even though the base subcomplex of the RP efficiently reconstituted on mature CP (Supplementary Figure 2c and 2d) and can expel Pba1-Pba2 from mature CP (Fig. 3b). Interestingly, the binding of Blm10 to both mature and immature CP shows a disruption of the interaction at similar salt concentrations, suggesting that Blm10 is not sensitive to the affinity switch (compare Fig. 3c and 3e). This is consistent with the fact that Blm10 has been observed on mature as well as immature CP under physiological conditions17,26. In all, these data reveal an affinity switch during CP maturation that at least in part can explain the exclusive binding of Pba1-Pba2 to immature CP and RP to mature CP.

The Pba2 tail contributes to the affinity switch

Pba1 and Pba2 both contain an HbYX-motif that is required for functionality7,8, and a crystal structure of Pba1-Pba2 bound to the CP shows that both C-termini dock in a specific α-pocket8. Interestingly, in the interaction with the mature CP, the tail of Pba2 contributes only minimally to binding, since its deletion reduces the affinity with only 2-3 fold8. In comparison, deleting the tail of Pba1, reduced the affinity > 100 fold. The differential contribution to the affinity can be rationalized through analysis of the structure itself. Pba2 binds in an unusual manner to the CP, lacking several hydrogen bonds commonly observed for HbYX-motif binding in the α pockets (e.g. for the HbYX of Pba1 or Blm10). For example, the hydroxyl group of the tyrosine residue in the Pba2 HbYX-motif is far (4.2 Å) removed from the closest potential hydrogen bond partner8,12. Despite the apparent minor role in binding to the CP, the HbYX-motif of Pba2 is physiologically relevant, since mutant strains with a truncated tail show phenotypes similar to mutants lacking the Pba1 HbYX-motif7,8. Only after deletion of both HbYX-motifs, however, do strains show phenotypes that mimic pba1Δ strains7,8. Hence, the HbYX-motif of Pba2 has an unidentified but important physiological function. We hypothesized that the HbYX-motif of Pba2 is more important for binding with the immature CP as compared to the mature CP, thereby contributing to the observed affinity switch. Such a difference might arise from small changes in the conformation of the αα7 pocket, or from the fact that changes in Pba1-α5-α6 interactions could limit the ability of Pba2 to interact fully with its pocket in the mature CP.

The model described above predicts that both the Pba2 and Pba1 HbYX-motif would have a role in binding to the immature CP. To test this, we deleted the HbYX-motif from Pba1 (pba1-ΔCT3), Pba2 (pba2-ΔCT3), or both together (pba1-ΔCT3 pba2-ΔCT3) in an Ump1-Tap tagged background. Next, we tested the salt lability of Pba1-Pba2 binding to immature CP. To our surprise, Pba1-Pba2 remained bound to immature CP in both the pba1-ΔCT3 and pba2-ΔCT3 background even after washes with 1 M NaCl (Fig. 3f). The binding of Pba1-Pba2 to the immature CP is thus very different compared to the mature CP, as the latter showed a highly salt dependent interaction that depends largely on the Pba1 tail (Fig. 3a and 8). Only after deletion of both the Pba1 and Pba2 HbYX-motif (pba1-ΔCT3 pba2-ΔCT3) did we observe loss of binding of the Pba1-Pba2 complex to immature CP with high salt washes (Fig. 3f). Thus, in contrast to binding to mature CP, both the Pba1 and Pba2 HbYX-motif contribute substantially to the affinity of Pba1-Pba2 for immature CP. This suggests that a major contributor to the molecular mechanism of the affinity switch derives from differences in how the Pba2 HbYX-motif docks into the α6-α7 pocket.

Pba1 and Pba2 contribute to α5 and α6 incorporation

Upon purification of immature CP from a pba1Δ strain we noticed a reduced level of a specific proteasome core particle subunit after SDS-PAGE analysis (compare Fig. 3c and 3d). Based on the running behavior, previous assignments by other labs26,43 and our own mass spectrometry analysis (Fig. 4a, 4b, and Table 1) we determined this was the subunit α6. This suggests that there is a reduced level of α6 present in immature proteasomes in the absence of Pba1. Additional mass spectrometry analysis suggested that besides α6 there might also be reduced levels of α5. To test this, we ran 2D gels of mature CP from wildtype and immature CP from wildtype and pba1Δ strains (Fig. 4c and Supplementary Figure 3). These gels confirmed the substantial reduction in levels of α5 and α6 from immature CP purified from pba1Δ strains. Pba1 thus likely has a role in efficient incorporation of α5 and α6, similar to Pba3-Pba4, which has a role in controlling α3 (Pre9) and α4 (Pre6) incorporation. However, α5 and α6 are essential subunits of the proteasome, making a potential role for Pba1-Pba2 in formation of alternative proteasomes, as was proposed for Pba3-Pba43, unlikely. Considering the thermodynamic stability of rings once they have formed44-46, the reduced level of these two subunits most likely indicates a slow incorporation of these subunits into the α ring in a pba1Δ strain. However, an alternative or additional role of Pba1-Pba2 might be the stabilization of α5 and α6 once they have been incorporated into the α ring, in particular since α5 and α6 appear to be absent in the high salt wash of the pba1-ΔCT3 pba2-ΔCT3 strain (Fig. 3F).

Figure 4. Pba1-Pba2 are required for efficient incorporation of α5 and α6.

(a) Immature CP from wildtype strain was purified and resolved on SDS-PAGE. Two bands that were consistently absent or reduced in a pba1Δ background (See Fig. 1c, 3c, and 3d) were excised and submitted to mass spectrometry analysis for identification (see Table 1). Band 1 was identified as Pba1 and Pba2, while α6 was the major component of Band 2, consistent with previous assignments15,26,43. (b) Unique peptides from the mass spectrometry analyses in (a) that cover regions of the pro-peptides of β1, β2, and β5 are underlined with the pro-peptide sequence in bold. (c) Purified mature or immature CP from indicated strains were resolved by two-dimensional gel electrophoresis using a non-linear ZOOM® IPG strip (pH 3–10) followed by SDS-PAGE. Gels were stained with CBB. Proteins spots were assigned based on immunoblotting (Supplementary Figure 3a), mass spectrometry analyses (underlined and Supplementary Figure 3b), and previous assignments26,43.

Table 1. Mass spectrometry analyses of band 1 and band 2 in Figure 4a.

| Band | Protein Name |

Standard Name |

Systematic Gene Name |

# unique peptides |

# total Spectra |

% coverage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Pba1 | Pba1 | YLR199C | 9 | 25 | 42 |

| Pba2 | Add66 | YKL206C | 10 | 23 | 35 | |

| α5 | Pup2 | YGR253C | 7 | 10 | 28 | |

| β5 | Pre2 | YPR103W | 6 | 8 | 21 | |

| α7 | Pre10 | YOR362C | 4 | 7 | 18 | |

| α4 | Pre6 | YOL038W | 5 | 6 | 23 | |

| α1 | Scl1 | YGL011C | 2 | 2 | 8 | |

|

| ||||||

| 2 | α6 | Pre5 | YMR314W | 16 | 32 | 75 |

| Ump1 | Ump1 | YBR173C | 7 | 20 | 47 | |

| β1 | Pre3 | YJL001W | 9 | 15 | 39 | |

| β5 | Pre2 | YPR103W | 2 | 2 | 9 | |

| β2 | Pup1 | YOR157C | 2 | 2 | 8 | |

Preventing premature RP binding improves assembly efficiency

Our data provide experimental evidence and mechanistic insight into a role of Pba1-Pba2 in preventing binding of RP to immature CP. To better understand the importance of the observed affinity switch, we developed a mathematical model in which we manipulated the affinity of Pba1-Pba2 for the CP α ring.

In our model of proteasome assembly, the α-ring is nucleated by the formation of an α5-α6 dimer and we kept the roles of the Pba3-Pba4 chaperone1,47,48 implicit. After α-dimers form, other α subunits can bind on either end of the complex, eventually leading to the formation of the α ring. We ignored subsequent steps in CP maturation (addition of the β subunits, half proteasome dimerization, etc.) in order to reduce the complexity of the model. To test the effect of the proposed affinity switch, we used various affinities for Pba1-Pba2 dimer bound to intermediates as well as the full α ring. We only included fully-formed RPs in this model, assuming the RP chaperones would prevent association between immature RPs and CP subunits28-31,33,34. Finally, since the Rpt ring of the RP makes many contacts with the α subunits of the CP13,49, RP binding to α–ring structures was considered to be stable when the α intermediate in question contained more than one subunit44-46.

We used this model to analyze how proteasome assembly efficiency (defined as the formation of fully active 26S RP-CP complexes) depends on the concentration of Pba1-Pba2 for three different scenarios. In the first, we implemented the affinity switch that was implied by our data (Fig. 5a and 5b, black lines). In the affinity switch model, the KD of Pba1-Pba2 for the mature CP was taken to be 1 μM (Supplementary Figure 2a), and the KD of Pba1-Pba2 for immature CP was taken to be 3 orders of magnitude stronger (1 nM) to represent the lack of dissociation of the chaperones from immature CP even in high salt (Fig. 3c). The other two scenarios lacked an affinity switch and the affinity of Pba1-Pba2 for mature and immature CP was either low (1 μM, “low affinity”, Fig. 5a and 5b, red lines) or high (1 nM, “high affinity”, Fig. 5a and 5b, green lines).

Figure 5. Pba1-Pba2 prevents assembly deadlock.

(a) Mathematical models were designed to investigate the function of Pba1-Pba2 (see text for details). The graph explores three scenarios. In the first (black line), we incorporated an affinity switch in our model. The Y-axis shows fraction of assembled proteasomes, which reaches 1 within the likely physiological range of concentrations of Pba1-Pba2 in the presence of an affinity switch (gray area). The second scenario (green line) assumed a high affinity rather than an affinity switch, while the third considered a low affinity (red line). (b) This graph displays the fraction of complexes where the RP is associated with the CP prior to CP maturation, yielding unproductive, deadlocked complexes. (c) Proposed conceptual model for the role of Pba1-Pba2 in CP maturation (see text for details).

As can be seen in Figure 5a, the behavior of these three scenarios is quite different. The presence of an affinity switch results in very high assembly yield compared to the absence (i.e. very low concentrations) of Pba1-Pba2; going from 75% to almost 100%. The improved assembly results from a decrease in RP binding to immature CP intermediates (Fig. 5b). When the concentration of Pba1-Pba2 reaches unphysiologically high levels (~100 μM), it overcomes the affinity switch and begins to interfere with 26S assembly by blocking RP association with mature CP (Fig. 5a). The 75% yield in the absence of Pba1 or Pba2 fits well with in vivo data, where the deletion of Pba1 or Pba2 does not cause a severe phenotype25,26, but likely causes a reduction in assembly yield substantial enough to explain synergistic phenotypes with other proteasome mutants25,26.

If we remove the affinity switch, however, the robust increase in assembly yields due to the presence of Pba1-Pba2 is no longer observed in the model. When affinities are uniformly low (Fig. 5a, red line), Pba1-Pba2 simply does not bind either immature or mature CP well enough at physiological concentrations to have an impact on assembly yields. When affinities are uniformly high, on the other hand, Pba1-Pba2 block RP binding to both the mature and immature CP, resulting in lower yields (Fig. 5b, green line).

While the results in Figure 5 suppose a particular concentration of both RP and CP subunits in the cell, independent variations in these concentrations do not influence the overall trends observed in the model (Supplementary Figure 4a). Similarly, changes to the size of the affinity switch also do not influence the general behavior of the model (Supplementary Figure 4b). Our model thus provides a robust explanation for the functional role of the Pba1-Pba2 affinity switch: by blocking premature RP-CP association, these chaperones prevent the stabilization of intermediates that would lead to CP assembly deadlock44. The switch from a high-affinity to low-affinity binding conformation upon CP maturation ensures that the chaperone “gets off” the complex at the right time, allowing the RP to bind once the CP is fully formed.

Discussion

Figure 5c summarizes our current conceptual model of the role of Pba1-Pba2. CP assembly starts with the formation of the α1–7 ring. In the early steps of assembly, both the Pba1-Pba2 and the Pba3-Pba4 dimers have a role in efficient ring formation. Pba3-Pba4 has a role in ring nucleation and ensures incorporation of α33. The presence of Pba1-Pba2 ensures the efficient incorporation or stabilization of α5 and α6. Next, the β-subunits assemble onto the α ring; at this step in the process, Pba3-Pba4 must dissociate from the complex to avoid steric clashes with the βsubunit4. However, Pba1-Pba2 remains bound until late in the assembly process, shielding the external surface of the α ring from RP and Blm10 and also preventing α-ring dimerization9.

After assembly of the β-ring several steps must occur, including dimerization of immature half proteasomes and autocatalytic activation1,48. Our results show that maturation of the CP causes a change in the binding of Pba1-Pba2 to the CP. While the structural basis of the affinity switch has yet to be determined, our data suggest that conformational changes in the CP that accompany maturation impact the capacity of the HbYX-motif on Pba2 to interact with the α6-α7 pocket. The affinity switch we have identified allows the chaperone to specifically protect the immature CP from interactions with regulatory factors, thereby preventing the formation of unproductive complexes that decrease the assembly yield of functional proteasomes. It is likely that other assembly chaperones (particularly those that bind to immature RPs, e.g. Nas6) utilize a similar mechanism, preventing association with larger assemblies prior to completion of subcomplex assembly. Small structural changes that accompany maturation likely reduce the affinity for these chaperones, allowing for the coordinated exchange of possible binding partners during the assembly process.

Methods

Yeast techniques and reagents

Yeast strains used are summarized in Supplementary Table 2. Genomic manipulation of yeast was done using a PCR based approach50,51. Upon transformation of yeast, successful integration was confirmed by positive PCR for integration and negative PCR for wildtype. Pba1 knockout primer pRL 252 (5′-AAG ATA TCA TCG CAC TAC AGT AAA ATT TTC ATT TAT AGC GCG GAT CCC CGG GTT AAT TAA-3′) and pRL253 (5′-CTC TTT CAC TCG CCA TTA CTG ACA TTC TGT GAT CGC CAT CAT CGA TGA ATT CGA GCT CGT-3′) and Pba2 knockout primers pRL254 (5′-ACT TCA GGA AAG AAT AGC ACA AAA CCC AAA GGA ACA TAC GCG GAT CCC CGG GTT AAT TAA-3′) and pRL255 (5′-TAT ATG CAC TTG TAT AGA AAA CAG ATA TAC TTC TCG GTT CAT CGA TGA ATT CGA GCT CGT-3′) were used together with templates pAG25 (natMX4) and pAG32 (hphMX4)51 in a PCR to prepare DNA for yeast transformation. To create a strain deleted for Blm10, smash and grab prepared genomic DNA from a strain where the Blm10 ORF was replaced with ClonNAT selection cassette27 was used as template for PCR with the following primers: pf2Blm10 (5′-CTG TCA TCA GGG CTT G-3′) and pr2Blm10 (5′-GTT GAT CAT TCT CAG TGG-3′). To produce C-terminal truncation of Pba1 that deleted the codons coding for the last three amino acids of Pba1, pba1-ΔCT3, primers pRL210 (5′-TGG AGG TGT GAT AGC GCG GCA ATT GGT GCA CAA TCA GGC TGA GGC GCG CCA CTT CT-3′) and pRL253 (5′-CTC TTT CAC TCG CCA TTA CTG ACA TTC TGT GAT CGC CAT CAT CGA TGA ATT CGA GCT CGT-3′) were used with pFA6a-3HA-kanMX6 as template50. To create pba2-ΔCT3 primers pRL211 (5′-GCA TAC GGA ATG GCG GAT GCA AGA GAT AAA TTT GTA GAT TGA GGC GCG CCA CTT-3′) and pRL255 (5′-TAT ATG CAC TTG TAT AGA AAA CAG ATA TAC TTC TCG GTT CAT CGA TGA ATT CGA GCT CGT-3′) were used with pFA6a-3HA-TRP1 as template50. Integrations were confirmed by PCR and sequencing. To create a strain with C-terminal YFP tag fused to β2 we used a knock-in DNA fragment synthesized from pDH6 as template (a generous gift of the Yeast Resource Center) in a PCR with primers pRL73 (5′-AAT ATT TGT GAC ATA CAA GAA GAA CAA GTC GAT ATA ACG GCT GGT CGA CGG ATC CCC GGG -3′) and pRL74 (5′-TGA TTT ACT ATA CTA AAA TAT ACT TAA GTT CTA TGT TTT ACT ATC GAT GAA TTC GAG CTC G -3′). Gibson cloning kit (NEB) was used to create a CEN plasmid that expresses His-Myc Pba2 utilizing the promoter and terminator of PBA2. pRS416 was digested with BamHI and mixed with two PCR products that were generated using yeast gDNA as template together with the following primer pairs: pRL274 (5′-TGC AGC CCG GGG GAG TCC TCG ATT TGA CTG GAA AC-3′) with pRL275 (5′-CAG ATC TTC CTC GCT AAT CAG CTT CTG CTC CAT CGT ATG TTC CTT TGG GTT TTG TGC-3′) and pRL276 (5′-GAG GAA GAT CTG CAC CAC CAT CAC CAT CAC CAT GGA AGC AGC TGC CTG GTG TTG CC-3′) with pRL277 (5′-CGC TCT AGA ACT AGT GAA ATT CAA AGA GAT GTT ACA GAC-3′) using the manufacturers protocol. The resulting plasmid is pCEN-His-Myc-Pba2 (pJR643).

A polyclonal antibody that recognizes the Pba1-Pba2 complex was generated using a standard immunization protocol (Rockland Immunochemicals, Inc.) with a dimer of Pba1 and His-tagged Pba2 purified from E.coli as the antigen (see Supplementary Figure 2b). Ecm29 and Rpn5 were detected using polyclonal antibodies kindly provided by Dr. Dan Finley (Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA). Monoclonal antibodies for α7 and Rpt5 were kindly provided by Dr. William Tansey (Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center, Nashville, TN). Polyclonal anti-pup1 (β2) antibody was a generous gift from Dr. R. Jürgen Dohmen (University of Cologne, Cologne, Germany). Antibodies recognizing Rpt1 and Blm10 were purchased from ENZO life sciences and THE™ HIS-tag antibody was obtained from GenScript. Peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies were purchased from Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories and for Fig. 2f Rabbit TrueBlot® IgG HRP from Rockland Immunochemicals was used. Anti-Myc antibody (9E10) was derived from an atcc hybridoma cell line (#CRL1729). The monoclonal anti-pgk-1 antibody was purchased from life technologies (#459250). All antibodies were used in 1:000 dilutions in TBST, except those against pgk-1 (1:10,000), Pba1-Pba2 (1:500), Myc (1:5), and Rpt5 (1:5,000). Uncropped images from the most important immunoblots are provided as Supplementary Figure 5.

Proteasome purification

The purification of proteasomes and proteasome subcomplexes from yeast were in essence performed as described previously29-31,38. Specific yeast strains were grown overnight in 2 to 3 liters of YPD media (final A600 ~ 10.0). Cells were collected and washed with H2O. Pellets were resuspended in 1.5 pellet volume of lysis buffer (50 mM Tris [pH8.0], 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM ATP) and lyzed by French press (1200 Psi.). Lysates were cleared by centrifugation (10,000g for 30mins) and supernatant was filtered through cheesecloth prior to incubation with IgG beads (MP Biomedical; 0.75 ml resin bed volume per 25 gram of cell pellet). After 1 hour of incubation (rotating at 4 °C), IgG beads were collected in an Econo Column (Bio-Rad) and washed with 50 bed volumes of ice-cold wash buffer (50 mM Tris [pH 7.5], 5 mM MgCl2, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM ATP). Next, material was washed with 15 bed volumes of cleavage buffer (50 mM Tris [pH 7.5], 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, 1 mM ATP). Bead-bound proteasome complex was either directly analyzed by loading on the SDS-PAGE after boiling with equal amount of 2× SDS PAGE sample buffer or eluted by incubation with His-Tev protease (Invitrogen). Protease was removed by incubation with talon resin prior to concentrating the proteasome complexes using 100-kDa concentrator (PALL Life Sciences). Proteasome purifications were used directly or stored at −80 °C in the presence of 5% glycerol.

Reconstitution assay

Proteasome core particles and regulatory particles were purified as described previously38 using strain sJR797 and SY36 respectively. 12.5 nM of CP and 62.5 nM of purified Pba1-Pba2 dimer protein were reconstituted in reconstitution buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM ATP, 50 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol) (Supplementary Figure 2) and incubated for 30 minutes at 30 °C. Next, increasing amounts of RP were added to different tubes (0 nM, 1.25 nM, 2.5 nM, 6.25 nM, 12.5 nM, 25 nM in reconstitution buffer), and the volume was adjusted to 20 μl for all samples. Samples were incubated for 30 minutes at 30 °C. To analyze the reconstitution assay, 1/10 volume of native gel loading buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4], 50% glycerol, 60 ng ml−1 xylene cyanol) was added and samples were loaded onto native gel52. First, gels were analyzed by in gel protease activity using LLVY-AMC as substrate. Next, samples were transferred to pvdf membrane for immunoblotting as described previously38.

Expression and purification of Pba1 and Pba2 complex

The ORF of PBA1 was amplified from yeast gDNA by PCR using primers pRL145 (5′-CTG TTG GAT CCA TGC TTT TTA AAC AAT GGA ATG ACT TAC CAG-3′) and pRL146 (5′-CGG GAA TTC TCA TAT ATA TAG GCC TGA TTG TG-3′). The PCR product was cloned into pNU247, a pGEX-6PK-1 derived plasmid, using the enzymes BamHI and EcoRI. The ORF of PBA2 was amplified from yeast gDNA by PCR using primers pRL147 (5′-GGC AGA TCT TGA AAA CCT GTA TTT CCA GGG ACA GGA TCC GAT GAG CTG CCT GGT GTT G-3′) and pRL148 (5′-CTC GAG CTC TCA ATT GTA TAA ATC TAC-3′). The PCR product was cloned into pRSF Duet-1 (EMD Millipore) using BglII and BamHI sites. The resulting plasmids were introduced together into Rosetta DE3 cells (stratagene) to enable co-purification of GST-tagged Pba1 and His-tagged Pba2. Transformed cells were inoculated in LB supplemented with kanamycin, ampicillin and chloramphenicol and incubated at 37 °C with shaking at 200 rpm. At an OD600 of 0.6, IPTG was added to 0.1 mM final concentration and the culture was incubated overnight at 37 °C with shaking. Cells were harvested by centrifugation (6,000 g, 10 min., 4 °C), washed in sterile H2O and resuspended in lysis buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 100 mM NaCl and 0.1% Triton X-100) supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail tablet (Roche). Lysis was performed at 900 psi using a French press system. Lysate was cleared by centrifugation (10,000 g, 30 min. at 4 °C). To the clear cell lysate glutathione agarose resin (GoldBio) (100 μl per 100 ml culture) was added and samples were incubated at 4 °C for 1 hour. The resin was washed four times with total 50 bed volumes of PBS buffer containing 0.1% triton X-100 and 0.02% Na-azide. To elute the Pba1-Pba2 dimer, resin was washed and resuspended in GST precision cleavage buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 6.8], 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT, and 0.01% Triton X-100) and incubated overnight in the presence of GST-precision protease. Eluted material was further purified using an AKTA purifier with a HiLoad Superdex 200 column equilibrated with reconstitution buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 5 mM MgCl2, 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM ATP, and 1 mM DTT). Fractions containing Pba1-His-Pba2 protein were collected and concentrated using 10 KDa concentrator (PALL Life Sciences).

Salt dependent binding

To test for salt dependent binding as described in Figure 2, indicated strains were processed using our standard proteasome purification protocol, up until the IgG beads washing step. Here, 20 bed volumes of a different wash buffer were used (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EDTA, and 1 mM ATP, 0.1% triton X-100). Next, washed IgG beads were distributed equally amongst five eppendorf tubes. Beads were resuspended in 5 bed volumes of buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EDTA, and 1 mM ATP, 0.1% triton X-100) containing different concentrations of NaCl (0 mM, 100 mM, 250 mM, 500 mM, and 1000 mM NaCl) and incubated for 3 minutes at room temperature under rotation. Beads were pelleted by centrifugation (500 g, 1 minutes at 4 °C). This washing step was performed two additional times. Next, beads were washed twice with 5 bed volumes of low salt buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH7.5], 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, 1 mM ATP, and 0.1% triton X-100). Finally, samples were resuspended in 2× SDS-PAGE sample buffer and loaded on 12% SDS-PAGE.

Binding affinity measurements

Binding kinetics of the His-tagged Pba1-Pba2 to purified mature CP were measured using bio-layer interferometry on a BLItz instrument (ForteBio). The Pba1-Pba2 complex was immobilized on a Ni-NTA biosensor using a 4.5 μM solution. Different concentrations of CP (from 0.0 μM to 1.8 μM) in reconstitution buffer (50mM Tris [pH 7.5], 5mM MgCl2, 50mM NaCl, 1mM ATP, 10% Glycerol) were used as analyte. Advanced kinetic experiment setup was used and kinetic parameters (kon and koff) and affinity (KD) were calculated from a global fit (1:1) of the BLItz instrument data using the BLItz software.

Cyclohexamide chase

Specific yeast strains were grown overnight in 5 ml of YPD or minimal selection media. The next day, cells were diluted to OD600 0.3 in fresh medium and allowed to grow up to logarithmic growth (OD600 1.0). Cells were then treated with cyclohexamide (100μg ml−1) for the indicated number of minutes and cells equivalent to 1 ml of OD600 2.0 of cells were collected at each time point. Equal amounts of protein extract from each time point were then loaded on 11% SDS-PAGE and a western blot was performed.

2D gel analysis

Ump1-containing immature CP complexes were purified from sJR792 and sJR793 using the proteasome purification protocol described above. 25 μg of each purified complex was vacuum dried and rehydrated in 140 μl of 2D rehydration buffer (8 M Urea, 2% CHAPS, 20 mM DTT, 0.002% Bromophenol Blue, 0.5% ZOOM® carrier ampholytes pH 3-10 (Life technology)). Isoelectric focusing was done using ZOOM® IPG Strips - pH 3-10NL (non-linear) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Next, IEF strips were incubated in 1× SDS PAGE sample buffer for 10 minutes. Strips were inserted into 12% percent SDS PAGE to run for the 2nd dimension. After electrophoresis, gels were either stained with coomassie brilliant blue or used to transfer samples to pvdf for subsequent analysis by immunoblotting.

Mass spectrometry

MS-grade solvents were purchased from Burdick & Jackson or Baker, sequencing grade trypsin from Promega and other solutions were the highest grade available from Sigma-Aldrich. For digestions, samples were denatured by SDS-PAGE (gel bands or spots), reduced with TCEP, alkylated with IAA, and digested overnight with 4 μg ml−1 trypsin, using Tris-HCl (pH 8.5) to buffer all solutions. For LC-MS/MS analyses, samples were analyzed on a hybrid LTQ-Orbitrap mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) coupled to a New Objectives PV-550 nanoelectrospray ion source and an Eksigent NanoULC chromatography system. Peptides were analyzed by trapping on a 5 cm pre-column using a vented column configuration, followed by analytical separation on a New Objective 75 μm ID fused silica column with an integral fused silica emitter, packed in house with 40 cm of 3-μm Magic C18 AQ beads. Peptides were eluted using a 5-40% ACN/0.1% formic acid gradient performed over 100-200 min at a flow rate of 250 nL min−1.

During elution, samples were analyzed using Top Six methodology, consisting of one full-range FT-MS scan (nominal resolution of 60,000 FWHM, 300 to 2000 m/z) and six data-dependent MS/MS scans performed in the linear ion trap. MS/MS settings used a trigger threshold of 8,000 counts, monoisotopic precursor selection (MIPS), and rejection of parent ions that had unassigned charge states, were previously identified as contaminants on blank gradient runs, or that had been previously selected for MS/MS (dynamic exclusion at 150% of the observed chromatographic peak width).

MS Data analysis

Centroided ion masses were extracted using the extract_msn.exe utility from Bioworks 3.3.1 and were used for database searching with Mascot v2.2.04 (Matrix Science). The search parameters used were: 6.0 PPM parent ion mass tolerance, 0.6 Da fragment ion tolerance, allow up to 1 missed cleavage; variable modifications, carbamidomethyl (C), oxidation (M), propionamide (C), and pyro-glu (N-term Q). Database searching was conducted using the Saccharomyces cerevisiae plus filter, resulting 134809 entries. Peptide and protein identifications were validated using Scaffold v2.2.00 (Proteome Software) and the PeptideProphet algorithm53. Searches were performed using thresholds of 1% peptide false discoveries and 1% protein false discoveries with at least two peptides identified. Proteins that contained similar peptides and could not be differentiated based on MS/MS analysis alone were grouped to satisfy the principles of parsimony.

MALDI-TOF Analyses

Protein spots and gel blanks from 2-D gels were excised and digested with trypsin (8 μg ml−1). For MALDI-TOF analyses, peptide extracts were mixed with alpha-cyano-4-hydroxy-cinnamic acid and analyzed on a Voyager DE-PRO instrument operated in reflectron mode. Individual TOF spectra were routinely externally calibrated with a known peptide mix (100 ppm accuracy). Supplemental strategies included desalting and concentration of peptide extracts on miniature C-18 affinity columns (OMIX tips from Agilent), and internal recalibration of MALDI-TOF spectra using trypsin autolysis products (20 ppm accuracy). MALDI-TOF ion peaks were extracted using Data Explorer 4.0. Spectra were deisotoped at a peak detection threshold of 5% BP intensity, and a peak list from the m/z range 500 to 3000 was built using the five most intense peaks from each 100-m/z interval. Alternatively, weaker spectra were analyzed using manually optimized peak detection windows that visually tracked the baseline noise threshold. Peptide mass fingerprint searches were conducted using MASCOT (v2.2). Protein identifications were accepted if their MASCOT probability based MOWSE scores (PBM) were statistically significant, and if the PBM of the top-ranked candidate was markedly superior to that of the next-ranked candidate. Experimental peptide masses were assessed for systematic divergence from hypothetical calculated peptide masses, wherein random mass deviations were used to reject candidate identifications.

Numerical simulation

Our model of proteasome assembly was represented as a system of Ordinary Differential Equations (ODEs). We numerically integrated these ODEs using the CVODE library in the SUNDIALS package54. A description of the model itself, along with the full set ODEs, can be found in the Supplementary Notes 1 and 2. The concentrations of the different proteins in this model were estimated from experimental measurements in yeast55, and the interaction parameters (association rates, dissociation rates, affinities, etc.) were taken from bio-layer interferometry measurements (Supplementary Figure 2a).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by awards from the Johnson Cancer Research Center and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health (grant numbers P20GM103420 and P20GM103418) to JR, as well as an award from the Directorate for Biological Sciences at the National Science Foundation (grant number MCB-1412262) to EJD. We would like to thank Stella Y. Lee and members of the Roelofs and Deeds labs for helpful discussions, Jürgen Dohmen for sharing the pup1 antibody, Xavier Capalla for technical assistance, and Gunnar Dittmar for initial mass spectrometry analysis. Reported mass spectrometry analyses were performed in the DNA/Protein Resource Facility at Oklahoma State University, using resources supported by the NSF MRI and EPSCoR programs (award DBI/0722494).

Footnotes

Author contributions

P.S.W., A.O. and J.R performed the experiments and constructed the yeast strains. M.A.R. and E.J.D. generated the model and performed the calculations. Studies were conceived by P.S.W., E.J.D., and J.R. Manuscript was written by P.S.W., E.J.D. and J.R. with input from all authors.

Competing financial interest: the authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Marques AJ, Palanimurugan R, Matias AC, Ramos PC, Dohmen RJ. Catalytic mechanism and assembly of the proteasome. Chem Rev. 2009;109:1509–1536. doi: 10.1021/cr8004857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ramos PC, Dohmen RJ. PACemakers of Proteasome Core Particle Assembly. Structure. 2008;16:1296–1304. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2008.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kusmierczyk AR, Kunjappu MJ, Funakoshi M, Hochstrasser M. A multimeric assembly factor controls the formation of alternative 20S proteasomes. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2008;15:237–244. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yashiroda H, et al. Crystal structure of a chaperone complex that contributes to the assembly of yeast 20S proteasomes. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2008;15:228–236. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Takagi K, et al. Pba3-Pba4 heterodimer acts as a molecular matchmaker in proteasome alpha-ring formation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2014;450:1110–1114. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.06.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ramos PC, Hockendorff J, Johnson ES, Varshavsky A, Dohmen RJ. Ump1p is required for proper maturation of the 20S proteasome and becomes its substrate upon completion of the assembly. Cell. 1998;92:489–499. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80942-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kusmierczyk AR, Kunjappu MJ, Kim RY, Hochstrasser M. A conserved 20S proteasome assembly factor requires a C-terminal HbYX motif for proteasomal precursor binding. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2011;18:622–629. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stadtmueller BM, et al. Structure of a proteasome Pba1-Pba2 complex: implications for proteasome assembly, activation, and biological function. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:37371–37382. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.367003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hirano Y, et al. A heterodimeric complex that promotes the assembly of mammalian 20S proteasomes. Nature. 2005;437:1381–1385. doi: 10.1038/nature04106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schmidt M, Finley D. Regulation of proteasome activity in health and disease. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1843:13–25. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2013.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kish-Trier E, Hill CP. Structural Biology of the Proteasome. Annu Rev Biophys. 2013;42:29–49. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biophys-083012-130417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sadre-Bazzaz K, Whitby FG, Robinson H, Formosa T, Hill CP. Structure of a Blm10 complex reveals common mechanisms for proteasome binding and gate opening. Mol Cell. 2010;37:728–735. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lander GC, et al. Complete subunit architecture of the proteasome regulatory particle. Nature. 2012;482:186–191. doi: 10.1038/nature10774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beck F, et al. Near-atomic resolution structural model of the yeast 26S proteasome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:14870–14875. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1213333109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marques AJ, Glanemann C, Ramos PC, Dohmen RJ. The C-terminal extension of the beta7 subunit and activator complexes stabilize nascent 20 S proteasomes and promote their maturation. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:34869–34876. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M705836200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fehlker M, Wendler P, Lehmann A, Enenkel C. Blm3 is part of nascent proteasomes and is involved in a late stage of nuclear proteasome assembly. EMBO reports. 2003;4:959–963. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.embor938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weberruss MH, et al. Blm10 facilitates nuclear import of proteasome core particles. EMBO J. 2013;32:2697–2707. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2013.192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tar K, et al. Proteasomes associated with the Blm10 activator protein antagonize mitochondrial fission through degradation of the fission protein Dnm1. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:12145–12156. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.554105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dange T, et al. Blm10 protein promotes proteasomal substrate turnover by an active gating mechanism. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:42830–42839. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.300178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Qian MX, et al. Acetylation-mediated proteasomal degradation of core histones during DNA repair and spermatogenesis. Cell. 2013;153:1012–1024. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.04.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Beckwith R, Estrin E, Worden EJ, Martin A. Reconstitution of the 26S proteasome reveals functional asymmetries in its AAA+ unfoldase. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2013;20:1164–1172. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gillette TG, Kumar B, Thompson D, Slaughter CA, DeMartino GN. Differential roles of the COOH termini of AAA subunits of PA700 (19 S regulator) in asymmetric assembly and activation of the 26 S proteasome. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:31813–31822. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M805935200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smith DM, et al. Docking of the proteasomal ATPases’ carboxyl termini in the 20S proteasome’s alpha ring opens the gate for substrate entry. Mol Cell. 2007;27:731–744. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.06.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tian G, et al. An asymmetric interface between the regulatory and core particles of the proteasome. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2011;18:1259–1267. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Le Tallec B, et al. 20S proteasome assembly is orchestrated by two distinct pairs of chaperones in yeast and in mammals. Mol Cell. 2007;27:660–674. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li X, Kusmierczyk AR, Wong P, Emili A, Hochstrasser M. beta-Subunit appendages promote 20S proteasome assembly by overcoming an Ump1-dependent checkpoint. EMBO J. 2007;26:2339–2349. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schmidt M, et al. The HEAT repeat protein Blm10 regulates the yeast proteasome by capping the core particle. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2005;12:294–303. doi: 10.1038/nsmb914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barrault MB, et al. Dual functions of the Hsm3 protein in chaperoning and scaffolding regulatory particle subunits during the proteasome assembly. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1116538109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee SY, De la Mota-Peynado A, Roelofs J. Loss of Rpt5 protein interactions with the core particle and Nas2 protein causes the formation of faulty proteasomes that are inhibited by Ecm29 protein. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:36641–36651. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.280875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Park S, et al. Reconfiguration of the proteasome during chaperone-mediated assembly. Nature. 2013;497:512–516. doi: 10.1038/nature12123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roelofs J, et al. Chaperone-mediated pathway of proteasome regulatory particle assembly. Nature. 2009;459:861–865. doi: 10.1038/nature08063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Park S, et al. Hexameric assembly of the proteasomal ATPases is templated through their C termini. Nature. 2009;459:866–870. doi: 10.1038/nature08065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ehlinger A, et al. Conformational dynamics of the rpt6 ATPase in proteasome assembly and rpn14 binding. Structure. 2013;21:753–765. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2013.02.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Satoh T, et al. Structural basis for proteasome formation controlled by an assembly chaperone nas2. Structure. 22:731–2014. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2014.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sahara K, Kogleck L, Yashiroda H, Murata S. The mechanism for molecular assembly of the proteasome. Adv Biol Regul. 2014;54:51–58. doi: 10.1016/j.jbior.2013.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kunjappu MJ, Hochstrasser M. Assembly of the 20S proteasome. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1843:2–12. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2013.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lehmann A, Janek K, Braun B, Kloetzel PM, Enenkel C. 20 S proteasomes are imported as precursor complexes into the nucleus of yeast. J Mol Biol. 2002;317:401–413. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2002.5443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kleijnen MF, et al. Stability of the proteasome can be regulated allosterically through engagement of its proteolytic active sites. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2007;14:1180–1188. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Leggett DS, et al. Multiple associated proteins regulate proteasome structure and function. Mol Cell. 2002;10:495–507. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00638-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.De La Mota-Peynado A, et al. The Proteasome-associated Protein Ecm29 Inhibits Proteasomal ATPase Activity and in Vivo Protein Degradation by the Proteasome. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:29467–29481. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.491662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Arciniega M, Beck P, Lange OF, Groll M, Huber R. Differential global structural changes in the core particle of yeast and mouse proteasome induced by ligand binding. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:9479–9484. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1408018111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Osmulski PA, Hochstrasser M, Gaczynska M. A tetrahedral transition state at the active sites of the 20S proteasome is coupled to opening of the alpha-ring channel. Structure. 2009;17:1137–1147. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2009.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chouduri AU, Tokumoto T, Dohra H, Ushimaru T, Yamada S. Functional and biochemical characterization of the 20S proteasome in a yeast temperature-sensitive mutant, rpt6-1. BMC Biochem. 2008;9:20. doi: 10.1186/1471-2091-9-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Deeds EJ, Bachman JA, Fontana W. Optimizing ring assembly reveals the strength of weak interactions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:2348–2353. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1113095109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bray D, Lay S. Computer-based analysis of the binding steps in protein complex formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:13493–13498. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.25.13493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Saiz L, Vilar JM. Stochastic dynamics of macromolecular-assembly networks. Mol Syst Biol. 2006;2:2006.0024. doi: 10.1038/msb4100061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kusmierczyk AR, Hochstrasser M. Some assembly required: dedicated chaperones in eukaryotic proteasome biogenesis. Biol Chem. 2008;389:1143–1151. doi: 10.1515/BC.2008.130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Murata S, Yashiroda H, Tanaka K. Molecular mechanisms of proteasome assembly. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:104–115. doi: 10.1038/nrm2630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lasker K, et al. Molecular architecture of the 26S proteasome holocomplex determined by an integrative approach. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:1380–1387. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1120559109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Longtine MS, et al. Additional modules for versatile and economical PCR-based gene deletion and modification in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 1998;14:953–961. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(199807)14:10<953::AID-YEA293>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Goldstein AL, McCusker JH. Three new dominant drug resistance cassettes for gene disruption in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 1999;15:1541–1553. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(199910)15:14<1541::AID-YEA476>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Elsasser S, Schmidt M, Finley D. Characterization of the Proteasome Using Native Gel Electrophoresis. Methods in Enzymology. 2005;398:353–363. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(05)98029-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Keller A, Nesvizhskii AI, Kolker E, Aebersold R. Empirical statistical model to estimate the accuracy of peptide identifications made by MS/MS and database search. Anal Chem. 2002;74:5383–5392. doi: 10.1021/ac025747h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hindmarsh AC, et al. SUNDIALS: Suite of nonlinear and differential/algebraic equation solvers. Acm T Math Software. 2005;31:363–396. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ghaemmaghami S, et al. Global analysis of protein expression in yeast. Nature. 2003;425:737–741. doi: 10.1038/nature02046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.