Abstract

Trifluoromethyl-substituted arenes and heteroarenes are widely prevalent in pharmaceuticals and agrochemicals. As a result, the development of practical methods for the formation of aryl–CF3 bonds has become an active field of research. Over the past five years, transition metal catalyzed cross-coupling between aryl–X (X = halide, organometallic, or H) and various “CF3” reagents has emerged as a particularly exciting approach for generating aryl–CF3 bonds. Despite many recent advances in this area, current methods generally suffer from limitations such as poor generality, harsh reaction conditions, the requirement for stoichiometric quantities of metals, and/or the use of costly CF3 sources. This Account describes our recent efforts to address some of these challenges by: (1) developing aryl trifluoromethylation reactions involving high oxidation state Pd intermediates, (2) exploiting AgCF3 for C–H trifluoromethylation, and (3) achieving Cu-catalyzed trifluoromethylation with photogenerated CF3•.

Introduction

Trifluoromethyl-arenes and heteroarenes are increasingly important structural features of pharmaceuticals and agrochemicals. The incorporation of a trifluoromethyl group into an organic molecule can dramatically impact a variety of properties, including metabolic stability, lipophilicity, and bioavailability.1 Despite the significance of this functional group in medicinal chemistry, mild, efficient, and functional-group tolerant methods for the formation of aryl/heteroaryl–CF3 linkages have been limited until very recently.1f,2

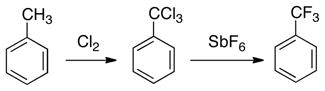

On the industrial scale, trifluoromethylated arenes are mainly produced by the Swarts reaction, which was developed in 1892.3 This transformation involves a two-step conversion of toluene derivatives to benzotrifluorides via: (1) radical chlorination followed by (2) treatment with an inorganic fluoride (e.g. SbF5) or anhydrous hydrogen fluoride (eq. 1).3 The requirement for reactive fluorinating reagents and high temperatures render this strategy incompatible with many common functional groups. Thus, the development of mild and flexible alternative methods for the installation of CF3 groups, particularly at late stages in the synthesis of complex molecules, is highly desirable.

|

(1) |

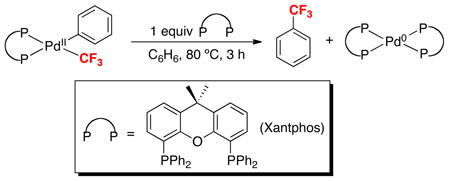

This Account describes our efforts in methods development and mechanistic investigations of transition metal-mediated aromatic trifluoromethylation reactions. When we initiated our work in this area in 2009, three groups had just reported exciting advances in Pd- and Cu-promoted arene trifluoromethylation reactions. For example, in 2006, Grushin demonstrated that (Xantphos)Pd(Ph)(CF3) undergoes stoichiometric Ph–CF3 bond-forming reductive elimination to release trifluorotoluene under mild conditions (80 °C, 3 h, eq. 2).4 This was the first reported example of selective aryl–CF3 coupling from a Pd center. The properties of the Xantphos ligand (particularly its large bite angle) were hypothesized to play an important role in this novel transformation.

|

(2) |

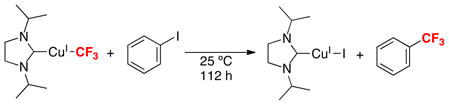

A major advance in the area of Cu-promoted trifluoromethylation was made in 2008, when Vicic reported the first example of an isolable, crystallographically characterized CuI–CF3 complex (eq. 3).5 This complex, which is supported by an N-heterocyclic carbene ligand, was shown to react with aryl iodides under mild conditions (25 °C, 112 h) to liberate trifluoromethylated products (eq. 3). While related Cu-mediated trifluoromethylations were known prior to this report,1f these previous systems generally involved ill-defined “Cu-CF3” intermediates.

|

(3) |

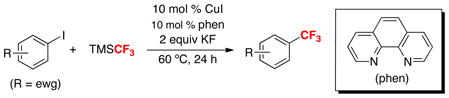

A final significant advance that occurred just prior to our entry into the field was a 2009 report by Amii.6 This work demonstrated the first copper catalyzed trifluoromethylation of aryl iodides. As shown in eq. 4, 1,10-phenanthroline (phen) was used as a supporting ligand for Cu in conjunction with TMSCF3 as the CF3 source. A variety of electron deficient aryl iodides underwent trifluoromethylation under these conditions.

|

(4) |

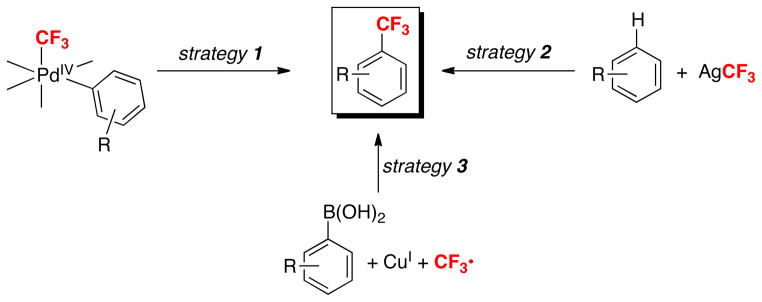

Our goal was to build on these exciting advances by developing new mechanistic pathways for metal-mediated aryl–CF3 coupling reactions. Over the last 3 years, we have pursued three different strategies to achieve this goal (Scheme 1). Strategy 1 involves aryl trifluoromethylation via reductive elimination from high valent PdIV(aryl)(CF3) intermediates. Strategy 2 involves exploiting AgCF3 intermediates to achieve aryl–CF3 bond formation. Finally, strategy 3 involves the trifluoromethylation of aryl-Cu intermediates with CF3•. All three of these approaches are described in detail below.

Scheme 1.

Three different strategies used in the Sanford group for aryl–CF3 coupling

Part 1. Aryl trifluoromethylation via high valent palladium

Historically, it has proven challenging to achieve aryl–CF3 bond-forming reductive elimination from PdII centers. Only two examples of this transformation have been reported in the literature, and both involve the use of specialized phosphine ligands to induce the desired reactivity. As described above, Grushin reported Ph–CF3 coupling from (Xantphos)PdII(Ph)(CF3) in 2006 (eq. 2).4a More recently, Buchwald has shown that (Brettphos)PdII(aryl)(CF3) (Brettphos = dicyclohexyl(2′-isopropyl-3,6-dimethoxy-4′,6′-dipropyl-[1,1′-biphenyl]-2-yl)phosphine) also undergoes aryl–CF3 bond-forming reductive elimination under mild conditions (80 °C, ~30 min).7

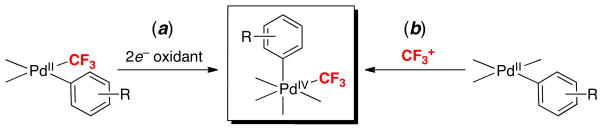

Our group aimed to achieve aryl–CF3 coupling from Pd using a different, complementary approach. Rather than modifying the ligands at PdII, we sought to achieve the desired reactivity by changing the oxidation state of the Pd center from PdII to PdIV. This idea was predicted on the fact that PdIV complexes are well-known to undergo other reductive elimination reactions (eg, C–F, C–Cl, C–I, C–N, C–O) that have proven challenging at PdII centers.8 To probe the viability of this strategy, we synthesized and studied the reactivity of PdIV(aryl)(CF3) intermediates. Two different synthetic routes were used to access these compounds: the 2e− oxidation of pre-formed PdII(aryl)(CF3) complexes (Scheme 2a) and the oxidation of PdII(aryl) complexes with CF3+ reagents (Scheme 2b).

Scheme 2.

Two synthetic routes to PdIV(aryl)(CF3) complexes

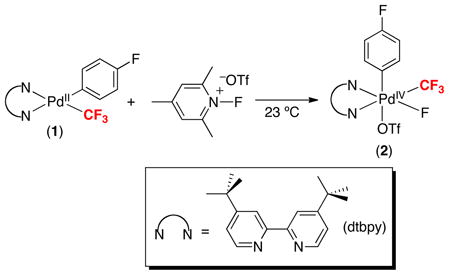

We initially pursued the synthesis of PdIV(aryl)(CF3) complexes via the 2e− oxidation of (N~N)PdII(aryl)(CF3) (1).9 4,4′-Di-tert-butyl-2,2′-bipyridine (dtbpy) was selected as the N~N ligand, since its rigid, bidentate structure is known to stabilize PdIV complexes.10 As shown in eq. 5, N-fluoro-2,4,6-trimethyl-pyridinium triflate (NFTPT) proved particularly effective for the oxidation of 1, yielding 2 in 53% isolated yield. This product was fully characterized by NMR spectroscopy and X-ray crystallography.

|

(5) |

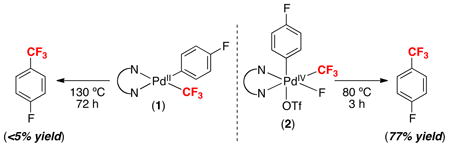

The availability of pure samples of 1 and 2 enabled a direct comparison of aryl–CF3 bond formation from dtbpy-ligated PdII versus PdIV centers. As shown in eq. 6, PdII complex 1 was inert towards thermal reductive elimination, affording <5% yield of p-F-Ph–CF3 even after 72 h at 130 °C (mass balance was predominantly recovered starting material). In marked contrast, the analogous PdIV complex underwent high yielding aryl–CF3 bond-forming reductive elimination over 3 h at just 80 °C (eq. 6). Notably, products derived from competing aryl–F or aryl–OTf coupling were not observed from 2, presumably due to the low reactivity of these ligands towards reductive elimination.2a,10a,b,11 Overall, the results in eq. 6 confirmed our original hypothesis that aryl–CF3 coupling can be accelerated by oxidation of a Pd center from PdII to PdIV.

|

(6) |

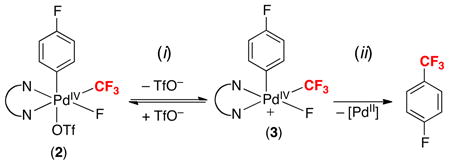

Experimental and computational mechanistic studies indicate that aryl–CF3 coupling from 2 proceeds via pre-equilibrium triflate dissociation (step i) followed by aryl–CF3 bond-formation from cationic intermediate 3 (step ii, eq. 7). These results led us to propose that replacing the dtbpy ligand with N,N,N′,N′-tetramethylethylenediamine (tmeda) would result in an acceleration of this C–C bond-forming event. Importantly, literature precedent has shown that the more flexible tmeda increases the rate of C–C coupling from the related PdIV complexes (N~N)PdIV(CH3)2(Ph)(I) (N~N = bpy versus tmeda).12 DFT calculations of analogues of 2 were consistent with this hypothesis, predicting that both triflate dissociation and aryl–CF3 coupling would be faster with tmeda. Experimental studies confirmed that the PdIV tmeda complex 5 is significantly more reactive than 2, as substitution of tmeda for dtbpy enables aryl–CF3 coupling to proceed at room temperature rather than 80 °C (eq. 8)!

|

(7) |

|

(8) |

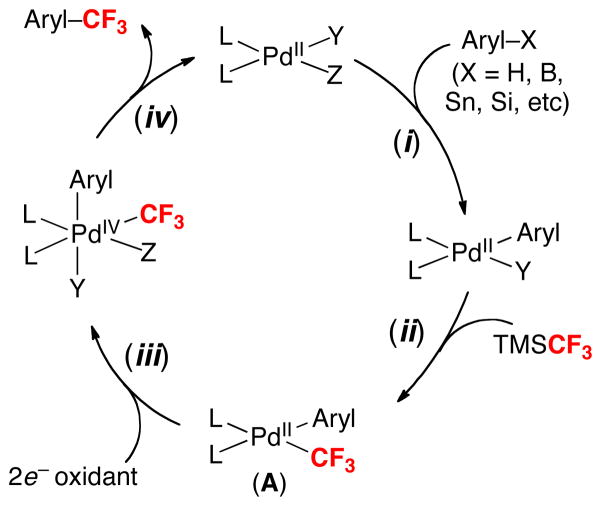

This work provides the basis for the development of many different types of PdII/IV-catalyzed aryl–CF3 cross-coupling reactions. A potential catalytic cycle for such transformations is outlined in Figure 1. Step i involves the formation of a PdII(aryl) complex. This could occur, for example, by C–H activation (X = H) or transmetalation (X = B, Sn, Si). Subsequent reaction with TMSCF3 (step ii) would yield PdII(aryl)(CF3) (A). Two-electron oxidation of A (step iii) followed by aryl–CF3 bond-forming reductive elimination (step iv) would then furnish the trifluoromethylated product and regenerate the catalyst.

Figure 1.

General catalytic cycle for Pd-catalyzed oxidative trifluoromethylation with TMSCF3

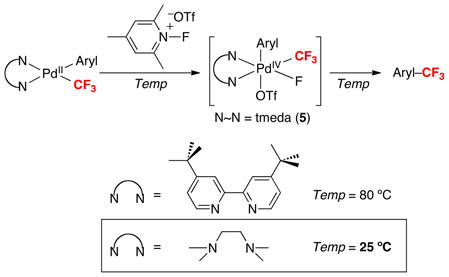

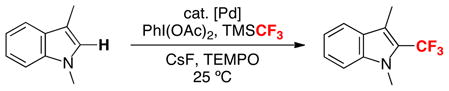

This approach is already being adopted to achieve synthetically useful trifluoromethylation reactions. For example, a recent report by Liu and coworkers exploited this strategy in the Pd-catalyzed C–H trifluoromethylation of indoles (eq. 9).13 While detailed mechanistic investigations of this transformation have not yet been conducted, the combination of aryl–H (indole), TMSCF3, and an oxidant [PhI(OAc)2] was proposed to react via a cycle very similar to that in Figure 1. An related pathway has also been proposed for the Pd-catalyzed aryltrifluoromethylation of alkenes.14 Numerous analogous transformations can be envisioned, and we anticipate that this approach could find widespread utility for Pd-catalyzed trifluoromethylation sequences.

|

(9) |

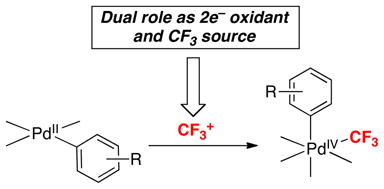

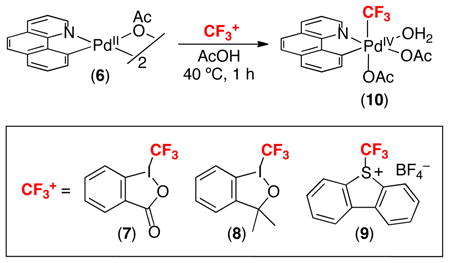

Our second strategy for generating PdIV(aryl)(CF3) intermediates is via the reaction of PdII(aryl) complexes with CF3+ reagents (eq. 10). Here the CF3+ plays two roles. First, it serves to oxidize the PdII to PdIV. Second, it serves as the source of CF3 in the product.

|

(10) |

We initially examined the feasibility of this transformation in the context of the cyclopalladated dimer [(bzq)PdII(OAc)]2 (6). This complex was selected for study for two reasons. First, it contains a rigid cyclometalated σ-aryl ligand, which should stabilize high valent Pd oxidation products.15 Second, it is believed to be a catalytically relevant intermediate in C–H functionalization reactions of benzo[h]quinoline.16 As such, studies of its reactivity could potentially be directly applicable to the development of catalytic ligand-directed C–H trifluoromethylation reactions.

The reaction of 6 with CF3+ reagents 7–9 in AcOH afforded the PdIV complex 10 (eq. 11).17 This complex was fully characterized by NMR spectroscopy and X-ray crystallography.

|

(11) |

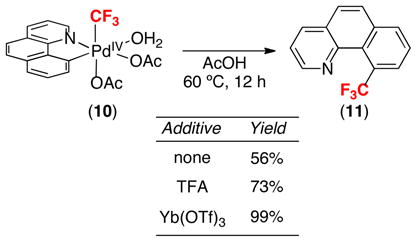

Complex 10 was stable at room temperature, but it decomposed at 60 °C with formation the aryl–CF3 coupled product 11 (eq. 12). However, under all of the conditions examined, the formation of 11 was sluggish, showed an induction period, and proceeded in only modest yield (56% in AcOH), with poor mass balance. While we have not yet been able to completely explain these results, we have identified additives that ameliorate many of these issues. In particular, reactions conducted in the presence of Brønsted acids (e.g., trifluoroacetic acid) or Lewis acids (e.g., Yb(OTf)3) were faster, occurred with minimal induction periods, and proceeded in significantly higher yields than those without these additives (eq. 12).

|

(12) |

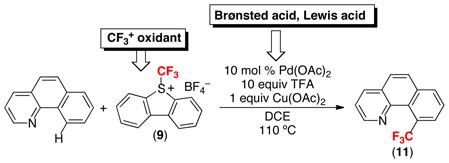

The lessons learned from these stoichiometric studies have proven highly relevant to Pd-catalyzed ligand-directed C–H trifluoromethylation reactions. In an elegant recent paper, Yu and coworkers achieved the Pd-catalyzed C–H trifluoromethylation of a variety of aromatic substrates using 9 as the CF3+ source. The optimal conditions for these transformations [using a chlorinated solvent in the presence of a Brønsted acid (TFA) and a Lewis acid (Cu(OAc)2)] are remarkably similar to those identified in our stoichiometric reactions with 6 and 11.18

|

(13) |

This suggested the possibility that PdIV complex 10 could be an intermediate in Yu’s catalytic reactions. Consistent with this proposal, the use of 10 as catalyst provided nearly identical yield to Pd(OAc)2. Furthermore, analysis of the initial rates with Pd(OAc)2 vs 10 showed that the PdIV complex is a kinetically competent catalyst for C–H trifluoromethylation.17

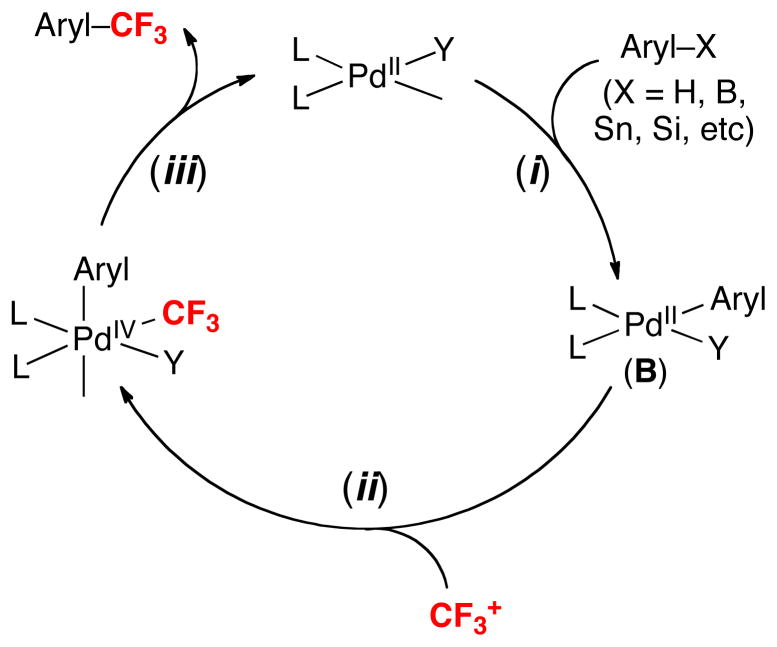

Overall, these studies demonstrate the viability of catalytic cycles like that in Figure 2 for PdII/IV-catalyzed trifluoromethylation. This cycle involves initial generation of PdII(aryl) intermediate B via C–H activation or transmetalation (step i). Oxidation of B with CF3+ (step ii) and subsequent C–CF3 coupling (step iii) then releases the trifluoromethylated product. We anticipate that this pathway could prove broadly useful for a number of different Pd-catalyzed transformations for introducing CF3 groups into organic molecules.

Figure 2.

General catalytic cycle for Pd-catalyzed oxidative trifluoromethylation with CF3+ reagents

Part 2: Aryl trifluoromethylation using AgCF3

Our second approach to uncovering new pathways for arene trifluoromethylation has been to explore metal catalysts beyond Pd and Cu. Our initial efforts in this area focused on Ag for three reasons. First, AgI has the same electronic configuration as CuI, which suggests the possibility for similar reactivity. Second, AgI salts have recently been used as catalysts for related organometallic reactions, including the fluorination of arylstannanes with F+ reagents.19 These examples suggest the possibility that organometallic Ag complexes can participate in aryl–X bond-forming transformations. Third, AgCF3 is readily synthetically accessible (although its reactivity with organic substrates had not previously been explored extensively).20

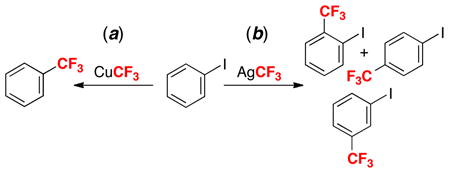

We first examined the reaction between AgCF3 and iodobenzene. PhI was selected as a substrate because it is known to react with CuCF3 complexes to generate trifluorotoluene (eq. 14a).1f Very surprisingly, the treatment of AgCF3 with PhI did not yield the expected cross-coupled product PhCF3. Instead, this reaction afforded a mixture of three isomeric C–H trifluoromethylation products (iodobenzotrifluorides) (eq. 14b).21 This is a particularly exciting result because it shows that moving to a different metal (from Cu to Ag) results in completely complementary reactivity.

|

(14) |

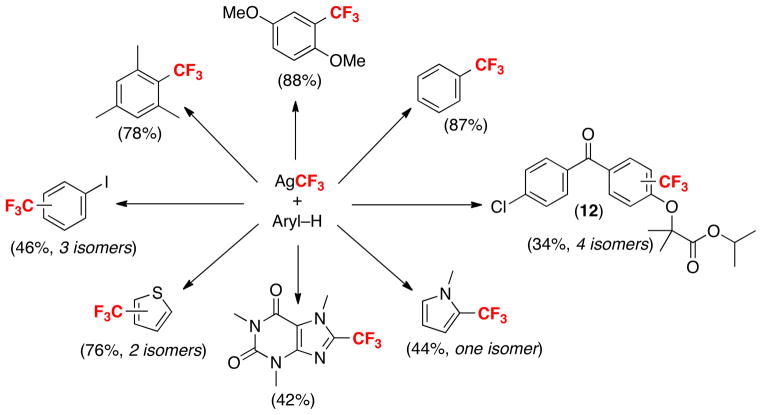

Optimization of this transformation led to a new Ag-promoted trifluoromethylation reaction that is applicable to a variety of substrates.18 As summarized in Scheme 3, reactions of electron rich aromatic and heteroaromatic compounds afforded particularly high yields. Somewhat lower yields were obtained with electron deficient aromatics. In substrates containing more than 1 type of aromatic C–H bond, mixtures of isomeric trifluoromethylated products were generally obtained. This feature could prove valuable to medicinal chemists, as it enables the transformation of a single lead molecule into a variety of different trifluoromethylated analogues in a single operation. This is exemplified in the formation of 12 as a mixture of 4 isomers from the trifluoromethylation of Tricor (a commercial cholesterol-lowering drug).

Scheme 3.

C–H trifluoromethylation reactions with AgCF3

While detailed mechanistic studies have not yet been conducted, several pieces of evidence implicate a pathway involving homolysis of the Ag–CF3 bond to generate Ag0 and CF3• followed by C–H functionalization via radical aromatic substitution. First, a Ag mirror is observed at the bottom of the flask at the end of these reactions, indicative of the reduction of AgI to Ag0. Additionally, the high reactivity with electron rich aromatics is consistent with the intermediacy of an electrophilic CF3 radical.22 Finally, the addition of 1 equiv of 2,2,6,6-(tetramethylpiperidin-1-yl)oxyl (TEMPO) to this transformation resulted in a dramatic reduction of the yield, suggesting the possibility that this additive is trapping the key CF3• intermediate.12

Overall these efforts demonstrate the viability of Ag as a promoter for C–H trifluoromethylation. The AgCF3-mediated transformations proceed under mild conditions and are complementary to analogous reactions of CuCF3. In addition, this work adds to a growing body of evidence suggesting that CF3• is a potent reagent for synthetically useful C–H trifluoromethylation reactions. For example, Baran and MacMillan have recently demonstrated the C–H trifluoromethylation of complex molecules with CF3• generated from either NaSO2CF3/tBuOOH (Baran)23 or CF3SO2Cl/Ru(phen)32+/visible light (MacMillan).24,25 All of these transformations serve as valuable methods for the trifluoromethylation of aromatic/heteroaromatic substrates under mild and functional group tolerant conditions.

Part 3. Cu-catalyzed aryl trifluoromethylation with CF3•

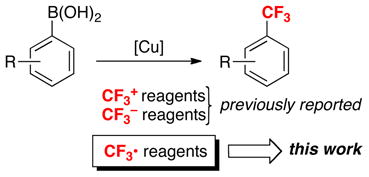

A third objective of our efforts in this area has been to identify new pathways for Cu-catalyzed boronic acid trifluoromethylation. Prior work had demonstrated that this transformation can be achieved via transfer of nucleophilic CF3− [derived from, for example, TMSCF3 or K(MeO)3B(CF3)]26,27 or electrophilic CF3+ (derived, for example, from 7–9)28 to the Cu catalyst (eq. 15). These two approaches are limited by the relatively high cost of some CF3−/CF3+ reagents, limited functional group tolerance in the presence of these highly nucleophilic/electrophilic reagents, and the requirement for high temperatures in some systems. We reasoned that these limitations could potentially be addressed by accessing an alternative mechanistic manifold in which CF3 transfer to the metal center occurs via CF3• (eq. 15). A discussed above in Part 2, CF3• can effect C–H trifluoromethylation via radical aromatic substitution. Thus, a key challenge for this approach is to identify a system in which reaction of CF3• with the metal catalyst is faster than competing uncatalyzed C–H trifluoromethylation. We selected Cu-based catalysts based on the fact that they are susceptible to rapid 1e− oxidation reactions.

|

(15) |

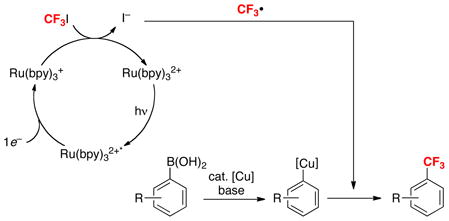

Our proposed approach to Cu-catalyzed trifluoromethylation requires a mild and readily available source of CF3•. We were inspired by several recent reports by MacMillan that used CF3I as a precursor to CF3• in the presence of visible light and a photocatalyst.29 As such, our initial studies focused on the Cu-catalyzed trifluoromethylation of boronic acid derivatives with CF3I in the presence of Ru(bpy)32+ (eq 16).

|

(16) |

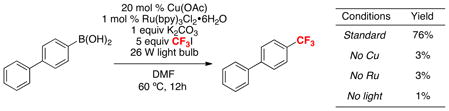

Our investigations revealed that the reaction of 1,1′-biphenyl-4-ylboronic acid with CF3I in the presence of 20 mol % of Cu(OAc), 1 mol % of Ru(bpy)32+, and visible light (two 26 W household light bulbs) affords the trifluoromethylated product 4-(trifluoromethyl)-1,1′-biphenyl in high yield (eq. 17).30 Importantly, the reaction proceeds in <5% yield when light, Cu, or Ru are excluded from the reaction mixture, indicating that all three of these components are necessary for the major reaction pathway. Furthermore, <2% of competing C–H trifluoromethylation of the substrate or product was observed, indicating that the relative rate of the Cu-catalyzed process is faster than radical aromatic substitution.

|

(17) |

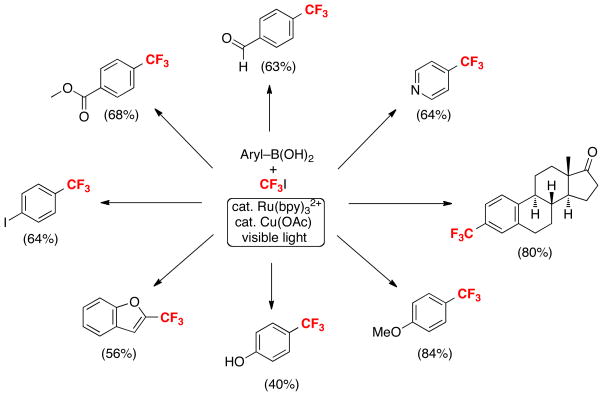

Scheme 4 summarizes the scope of this transformation. As shown, this method is effective for the trifluoromethylation of a wide variety of aromatic and heteroaromatic boronic acid substrates bearing many common functional groups. Importantly, analogous perfluoroalkylation reactions of boronic acids can also be conducted under these conditions using cheap and readily available perfluoroalkyl iodide starting materials.

Scheme 4.

Boronic acid trifluoromethylation reactions with CF3I

This work indicates that Cu-catalyzed trifluoromethylation reactions involving CF3• intermediates can be viable and facile processes. We believe that it is possible (even likely) that many Cu-catalyzed processes that were initially believed to involve CF3− or CF3+ transfer actually involve radical intermediates. For example, several reports have shown that Ag salts serve as promoters for the Cu-catalyzed trifluoromethylation of aryl iodides.20b,31 The role of Ag has been proposed to involve mediating transmetalation of CF3− from Si (in TMSCF3) to Cu.17b However, the current results (along with those in Part 2 of this Account) suggest that the role of Ag may be to generate CF3• in these transformations. In addition, CF3+ reagents can potentially undergo 1e− reduction to form CF3•, suggesting the possibility that Cu-catalyzed reactions of CF3+ reagents may also involve radical intermediates.28c,32

Our preliminary results also have important implications for the future development of Cu-catalyzed trifluoromethylation sequences. They suggest that combining aryl-Cu species (generated via transmetalation, C–H activation, oxidative addition, etc) with perfluoroalkyl radicals (generated via various possible oxidative or reductive pathways) could prove broadly effective for the construction of new fluorinated molecules.

Outlook

Over the past 5 years, the field of aromatic trifluoromethylation has experienced an explosion of research activity. In parallel with our own efforts, numerous advances from other research groups around the world1f,2,33 have dramatically expanded the organic chemists’ toolbox for installing CF3 groups onto arenes and heteroarenes. As discussed above, our contributions to this area have particularly focused on discovering new oxidation states (e.g., PdIV), new metals (e.g., Ag), and new reaction pathways (e.g., the combination of Cu and photogenerated CF3•) for achieving aryl–CF3 coupling. Moving forward, we anticipate that detailed mechanistic studies of all of these transformations will provide valuable insights for the development of second-generation catalysts. Furthermore, the invention of novel pathways and reagents for these reactions should stimulate advances that further facilitate the assembly of trifluoromethyl-containing molecules.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the NIH (GM073836) and NSF (CHE-1111563). We also acknowledge funding from NSF grant CHE-0840456 for X-ray instrumentation.

Biographies

Yingda Ye was born in Beijing, China in 1983. He received his B.E. degree in Computer Science from Beijing University of Technology in 2006. He then studied computer-aided drug design and pharmaceutical chemistry and obtained his M.S. at Tianjin University with Professor Kang Zhao in 2008. He has been working toward his Ph.D. at the University of Michigan with Professor Melanie Sanford since 2009, where he is focusing on transition metal catalyzed aromatic trifluoromethylation reactions.

Melanie Sanford was born in New Bedford, MA in 1975. She received B.S. and M.S. degrees in chemistry from Yale University in 1996 and a Ph.D. in chemistry from California Institute of Technology in 2001. After post-doctoral studies at Princeton University, she joined the faculty at the University of Michigan in 2003, where she is currently the Moses Gomberg Collegiate Professor as well as an Arthur F. Thurnau Professor of Chemistry.

References

- 1.(a) Schlosser M. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2006;45:5432. doi: 10.1002/anie.200600449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Müller K, Faeh C, Diederich F. Science. 2007;317:1881. doi: 10.1126/science.1131943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Hagmann WK. J Med Chem. 2008;51:4359. doi: 10.1021/jm800219f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Kirk KL. Org Process Res Dev. 2008;12:305. [Google Scholar]; (e) Purser S, Moore PR, Swallow S, Gouverneur V. Chem Soc Rev. 2008;37:320. doi: 10.1039/b610213c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Tomashenko OA, Grushin VV. Chem Rev. 2011;111:4475. doi: 10.1021/cr1004293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Roy S, Gregg BT, Gribble GW, Le VD. Tetrahedron. 2011;67:2161. [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Furuya T, Kamlet AS, Ritter T. Nature. 2011;473:470. doi: 10.1038/nature10108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Grushin VV. Acc Chem Res. 2010;43:160. doi: 10.1021/ar9001763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Swarts F. Bull Acad R Belg. 1892;24:309. [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Grushin VV, Marshall WJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:12644. doi: 10.1021/ja064935c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Bakhmutov VI, Bozoglian F, Gomez K, Gonzalez G, Grushin VV, Macgregor SA, Martin E, Miloserdov FM, Novikov MA, Panetier JA, Romashov LV. Organometallics. 2012;31:1315. [Google Scholar]

- 5.(a) Dubinina GG, Furutachi H, Vicic DA. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:8600. doi: 10.1021/ja802946s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Dubinina GG, Ogikubo J, Vicic DA. Organometallics. 2008;27:6233. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oishi M, Kondo H, Amii H. Chem Commun. 2009:1909. doi: 10.1039/b823249k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cho EJ, Senecal TD, Kinzel T, Zhang Y, Watson DA, Buchwald SL. Science. 2010;328:1679. doi: 10.1126/science.1190524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.(a) Hickman AJ, Sanford MS. Nature. 2012;484:177. doi: 10.1038/nature11008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Muniz K. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2009;48:9412. doi: 10.1002/anie.200903671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Lyons T, Sanford MS. Chem Rev. 2010;110:1147. doi: 10.1021/cr900184e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.(a) Ball ND, Kampf JW, Sanford MS. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:2878. doi: 10.1021/ja100955x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Ball ND, Gary JB, Ye Y, Sanford MS. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:7577. doi: 10.1021/ja201726q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.(a) Ball ND, Sanford MS. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:3796. doi: 10.1021/ja8054595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Ball ND, Kampf JW, Sanford MS. Dalton Trans. 2010;39:632. doi: 10.1039/b914426a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Canty AJ. Acc Chem Res. 1992;25:83. [Google Scholar]

- 11.(a) Racowski JM, Gary JB, Sanford MS. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2012;51:3414. doi: 10.1002/anie.201107816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Furuya T, Benitez D, Tkatchouk E, Strom AE, Tang P, Goddard WAI, Ritter T. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:3793. doi: 10.1021/ja909371t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Markies BA, Canty AJ, Boersma J, van Koten G. Organometallics. 1994;13:2053. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mu X, Chen S, Zhen X, Liu G. Chem Eur J. 2011;17:6039. doi: 10.1002/chem.201100283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mu X, Wu T, Wang HY, Guo YL, Liu G. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;134:878. doi: 10.1021/ja210614y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Racowski JM, Dick AR, Sanford MS. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:10974. doi: 10.1021/ja9014474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.(a) Powers DC, Ritter T. Acc Chem Res. 2012;45:840. doi: 10.1021/ar2001974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Canty AJ. Dalton Trans. 2009:10409. doi: 10.1039/b914080h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ye Y, Ball ND, Kampf JW, Sanford MS. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:14682. doi: 10.1021/ja107780w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang X, Truesdale L, Yu JQ. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:3648. doi: 10.1021/ja909522s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.(a) Furuya T, Strom AE, Ritter T. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:1662. doi: 10.1021/ja8086664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Furuya T, Ritter T. Org Lett. 2009;11:2860. doi: 10.1021/ol901113t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Tang P, Ritter T. Tetrahedron. 2011;67:4449. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2011.02.077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.(a) Tyrra WE, Naumann D. J Fluorine Chem. 2004;125:823. [Google Scholar]; (b) Wang Z, Lee R, Jia W, Yuan Y, Wang W, Feng X, Huang KW. Organometallics. 2011;30:3229. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ye Y, Lee SH, Sanford MS. Org Lett. 2011;13:5464. doi: 10.1021/ol202174a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.(a) Wakselman C, Tordeux M. J Chem Soc, Chem Commun. 1987:1701. [Google Scholar]; (b) Akiyama T, Kato K, Kajitani M, Sakaguchi Y, Nakamura J, Hayashi H, Sugimori A. Bull Chem Soc Jpn. 1988;61:3531. [Google Scholar]; (c) Sawada H, Nakayama M. J Fluorine Chem. 1990;46:423. [Google Scholar]; (d) Langlois BR, Laurent E, Roidot M. Tetrahedron Lett. 1991;32:7525. [Google Scholar]; (e) McClinton MA, McClington DA. Tetrahedron. 1992;48:6555. [Google Scholar]; (f) Kamigata N, Ohtsuka T, Fukushima T, Yoshida M, Shimizu T. J Chem Soc, Perkin Trans 1. 1994:1339. [Google Scholar]; (g) Kino T, Nagase Y, Ohtsuka Y, Yamamoto K, Uraguchi D, Tokuhisa K, Yamakawa T. J Fluorine Chem. 2010;131:98. [Google Scholar]; (h) Loy RN, Sanford MS. Org Lett. 2011;13:2548. doi: 10.1021/ol200628n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ji Y, Brueckl T, Baxter RD, Fujiwara Y, Seiple IB, Su S, Blackmond DG, Baran PS. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:14411. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1109059108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nagib DA, MacMillan DWC. Nature. 2011;480:224. doi: 10.1038/nature10647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Iqbal N, Choi S, Ko E, Cho EJ. Tetrahedron Lett. 2012;53:2005. [Google Scholar]

- 26.(a) Chu L, Qing FL. Org Lett. 2010;12:5060. doi: 10.1021/ol1023135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Senecal TD, Parsons AT, Buchwald SL. J Org Chem. 2011;76:1174. doi: 10.1021/jo1023377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Khan BA, Buba AE, Gooßen LJ. Chem Eur J. 2012;18:1577. doi: 10.1002/chem.201102652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Jiang X, Chu L, Qing FL. J Org Chem. 2012;77:1251. doi: 10.1021/jo202566h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.For an example of trifluoromethyl copper(I) reagent derived from CF3−, see: Morimoto H, Tsubogo T, Litvinas ND, Hartwig JF. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2011;50:3793. doi: 10.1002/anie.201100633.

- 28.(a) Liu T, Shen Q. Org Lett. 2011;13:2342. doi: 10.1021/ol2005903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Xu J, Luo DF, Xiao B, Liu J, Gong TJ, Fu Y, Liu L. Chem Commun. 2011;47:4300. doi: 10.1039/c1cc10359h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Zhang CP, Wang ZL, Chen QY, Zhang CT, Gu YC, Xiao JC. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2011;50:1896. doi: 10.1002/anie.201006823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.(a) Nagib DA, Scott ME, MacMillan DWC. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:10875. doi: 10.1021/ja9053338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Pham PV, Nagib DA, MacMillan DWC. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2011;50:6119. doi: 10.1002/anie.201101861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ye Y, Sanford MS. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:9034. doi: 10.1021/ja301553c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li YCT, Wang H, Zhang R, Jin K, Wang X, Duan C. Synlett. 2011;12:1713. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang CP, Cai J, Zhou CB, Wang XP, Zheng X, Gu YC, Xiao JC. Chem Commun. 2011;47:9516. doi: 10.1039/c1cc13460d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Besset T, Schneider C, Cahard D. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2012;51:5048. doi: 10.1002/anie.201201012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]