Abstract

Pol32 is an accessory subunit of the replicative DNA Polymerase δ and of the translesion Polymerase ζ. Pol32 is involved in DNA replication, recombination and repair. Pol32’s participation in high- and low-fidelity processes, together with the phenotypes arising from its disruption, imply multiple roles for this subunit within eukaryotic cells, not all of which have been fully elucidated. Using pol32 null mutants and two partial loss-of-function alleles pol32rd1 and pol32rds in Drosophila melanogaster, we show that Pol32 plays an essential role in promoting genome stability. Pol32 is essential to ensure DNA replication in early embryogenesis and it participates in the repair of mitotic chromosome breakage. In addition we found that pol32 mutantssuppress position effect variegation, suggesting a role for Pol32 in chromatin architecture.

Introduction

A eukaryotic chromosome is a highly organized DNA-nucleoprotein complex that regulates its metabolism—transcription, replication, recombination and repair—by intricate and continuous modifications of its protein components. The accuracy of genome replication is ensured by high-fidelity DNA polymerases (Pols). However, if DNA damage prevents these high-fidelity polymerases from continuing DNA replication, the cell tries to overcome the obstacle with a damage tolerant pathway, using specialized translesion Pols that lack exonucleolytic proof-reading activity. With the aid of these Pols, DNA synthesis can proceed without the collapse of the replication fork, but with the risk of possible mutations from incorrect nucleotide incorporation.

Pol32 is a small accessory subunit of both DNA Polymerase δ (Polδ) [1] and Polymerase ζ (Polζ) [2–4]. It is conserved during evolution, and participates in both high- and low-fidelity repair processes [5].

Polδ is a high-fidelity polymerase essential for chromosome replication, recombination and DNA repair in eukaryotic cells [6]. What is currently known about the structure and functions of Polδ comes mainly from studies on Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Schizosaccharomyces pombe, and humans.

In the budding yeast S. cerevisiae, Polδ is composed of three subunits, the catalytic subunit Pol3 and the Pol31 subunit, both essential, and a third small accessory subunit, Pol32 [7]. In the fission yeast S. pombe, Polδ contains four subunits: the catalytic subunit Pol3, and three small accessory subunits Cdc1, Cdc27 (corresponding to Pol31 and Pol32 respectively), and Cdm1 [8]. Orthologs of all the four yeast proteins, named p125, p50, p66 and p12 respectively, form mammalian Polδ [9].

In Drosophila melanogaster, Polδ is a three-subunit complex: the catalytic subunit DmPolδ, the putative Pol31 ortholog encoded by CG12018, and the recently identified small subunit Pol32; no Cdm1 ortholog has been identified so far [10–13]. Drosophila Pol32 contains conserved Polα and PCNA (proliferating cell nuclear antigen) interacting domains [14].

Pol32 is dispensable for growth in budding yeast, whereas the orthologous Cdc27 is an essential protein in fission yeast. Pol32 has two basic functions: to enhance Polδ complex activity during replication, and to repair DNA. Cells lacking Pol32 display defects in replication with frequent stalls, as well as an increased sensitivity to hydroxy-urea (HU), ultraviolet (UV) radiation and methylmethane sulphonate (MMS) mutagens; moreover, mutants display defects in break-induced replication (BIR) [15–17]. Pol32 is also required for telomerase-independent telomere maintenance [18].

In D. melanogaster, Pol32 is required for the repair of DNA Double-Strand Breaks (DSBs) by homologous recombination (HR) involving extensive DNA synthesis [13]. DSB lesions can arise during endogenous metabolism or they can be induced from exogenous sources such as ionizing radiation (IR) or chemical agents. If not properly repaired, DSBs lead to chromosome loss or chromosome rearrangements [19]. HR is one of the strategies that allow cells to repair DSBs [20].

In Yeast, Pol32 is also required for Polζ-mediated translesion synthesis (TLS) [17]. Polζ is not an error-prone Pol per se, but it extends DNA from mispaired bases after an incorrect nucleotide insertion by a Y-family Pol, across a replication-blocking lesion [21]. Yeast Polζ is composed of the catalytic subunit Rev3 and the accessory Rev7 subunit [22]; recent work demonstrates that both Pol32 and Pol31 are also functional subunits of Polζ [2–4].

Polζ is not essential for yeast viability, but a deletion of Rev3 results in a marked reduction in the frequency of base pair substitutions and frame shift mutations after UV radiation or chemical treatment with DNA damaging agents [3,23]. In mice, besides its role in TLS, a disruption of Polζ leads to embryonic lethality [24].

DmREV3 and DmREV7 subunits form D. melanogaster Polζ (DmPolζ) [25]. rev3 mutants are sensitive to MMS, nitrogen mustard and ionizing radiation; DmPolζ plays an important role in HR repair [13]. A biochemical interaction between DmREV7 and Pol32 has been predicted in a protein interaction map (DPiM) [12,26].

Drosophila is a good model for the characterization of genes involved in DNA repair and genome stability. In addition, although gene functions are evolutionarily conserved, some mutations that are lethal in higher organisms, such as Polδ and Polζ are in mice [24,27], are viable in Drosophila.

In this study, we investigated previously uncharacterized aspects of the role of Pol32 in promoting genome stability. Our results support the identification of CG3975 as the pol32 ortholog, as Kane and collaborators advocate in their paper [13].

We induced new mutant alleles of pol32; by analyzing the mutant phenotypes we found that Pol32 is required to ensure DNA replication during the early embryonic nuclear divisions. In addition we showed that the loss of Pol32 prevents the repair of DNA breaks in mitotic brain cells, conferring sensitivity to IR, and is important for EMS and ENU-induced damage repair. Moreover we found that pol32 mutants suppress position effect variegation, suggesting a novel role for Pol32 in the dynamics of chromatin architecture.

Materials and Methods

Drosophila chromosomes and culture conditions

Drosophila strains and crosses were raised at 25° on standard cornmeal yeast agar medium. Genetic markers and strains are described in [28] and FlyBase (http://flybase.bio.indiana.edu). The stocks used in the present work were supplied by Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center unless otherwise noted. The wild-type Oregon-R strain was used as a control unless otherwise noted.

P{PZ}ms(2)1006 ([29], kindly provided) has a single P{PZ} insertion in the 35B2-C polytene region carrying rosy (ry) as a marker gene. By inverse PCR, the insertion was mapped in the 5’ UTR region, 17 bases upstream of the pol32, ATG site (Fig. 1). P{EPgy2}CG3975 EY15283 [30] is reported as a single P insertion carrying white (w) as a marker gene, inserted downstream of 3'UTR of CG3975 (2L:15,254,643) [31], (named pol32 in [13]), (Fig. 1). Chromosome rd1 carried a lethal mutation which was removed by recombination, and an unidentified female sterile mutation. The recombinant rd1 chromosome was used in the present work. To avoid interference with the female-sterile and likely occurring other second site mutations on the second chromosome, trans-heterozygotes with Df(2L)pol32 R2 and Df(2L)pol32 NR42 (recovered in the present work, henceforth designated pol32 R2 and pol32 NR42, respectively) were used in all experiments. A mei-W68 k05603/Cy stock was used to construct the recombinant double mutant pol32 NR42 mei-W68/Cy, used for the embryogenesis analysis.

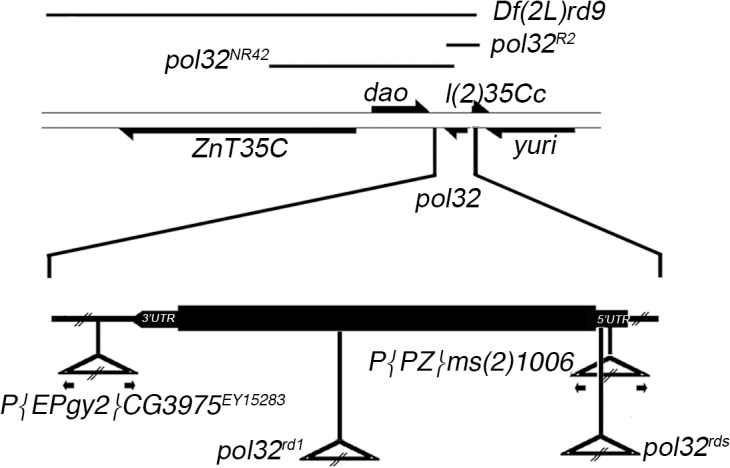

Fig 1. Diagram of pol32 genomic region.

Genes are depicted as arrows indicating the direction of transcription; the thick lines represent the coding region and the thinner lines, the intergenic regions. The lines above indicate the extent of the deletions used. Below, in the enlargement of pol32 gene, triangles indicate the locations of the transposable element insertions.

P-element mobilization and molecular characterization of excision lines

We recovered loss-of-function alleles by imprecise excision of P{PZ} ms(2)1006 and P{EPgy2}CG3975 EY15283 insertions by standard crosses using a Δ 2–3 transposase source [32]; the excisions were identified by following loss of ry or w expression, respectively. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was used to screen for the presence of small deletions flanking genomic sequences caused by imprecise excision of P-elements. The alleles pol32 R2 and pol32 NR42, recovered from P{PZ}ms(2)1006 and P{EPgy2}CG3975 EY15283 respectively, were used for subsequent genetic and molecular analysis. The genomic regions flanking the P{PZ}ms(2)1006 and P{EPgy2}CG3975 EY15283 insertions were recovered by plasmid rescue according to [33], cloned into Bluescript (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA), and sequenced. The primers used for molecular characterization of the P{PZ}ms(2)1006 and P{EPgy2}CG3975 EY15283 insertions and for the excision lines were: Plac1 5’-GAA GCCGATAGCTGCCCTG-3’; UB 5’-AACGCGGCCGCCAATAGCGGCAAGTAG-3’; Pry2 5’-CTTGCCGACGGGACCACCTTATGTTATT-3’; LA 5’-AAATAGATCTCTGGGCTTTTGTTGGTTT-3’; Plac1Lw1 5’-GCCTAAATGCGATACCTAAT-3’, Pry4 5’-CAATCATATCGCTGTCTCACTCA-3’, UB 5’-AACGCGGCCGCCAATAGCGGCAAGTAG-3’.

The pol32 R2 line contains a 2015 bp deletion (positions 15255302–15257317, FB2012_03, released May 11th, 2012), removing nearly all of the pol32 coding sequence and the 5' neighboring l(2)35Cc gene. The pol32 NR42 line carries about a 14 kb deletion (positions 15241415–15255722) that, in addition to a partial deletion of the pol32 gene, removes the dao and ZnT35C genes.

Fertility tests

Female fertility: to determine the embryonic lethality phase, 4-day-old females of the suitable genotype were crossed to pol32 NR42 homozygous males. Eggs were collected from fertilized females using apple-grape-juice agar plates. The eggs were monitored for several days and any first instar larvae were counted and transferred to fresh culture for further development. All the experiments were at 25°. Male fertility was determined as previously described [34].

Molecular biology

Unless otherwise noted, standard molecular techniques used are described in [35]. Total RNA was purified from female gonadal tissues using the RNA extraction kit (Qiagen) and samples were incubated with DNase I RNase free (Quiagen) to remove any DNA from the preparation, according to manufacturer’s instructions. RT-PCR was done with M-MLV reverse transcriptase using conditions suggested by the suppliers (Invitrogen). For the first-strand cDNA synthesis, 5μg of total RNA were used as a template for oligonucleotide dT primed reverse transcription using SuperScript III RNaseH-reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen), according to manufacturer’s instructions. qRT–PCR was performed in the SmartCycler Real-time PCR (Cepheid) using SYBR green (Celbio) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. For quantification of the transcripts we used the 2ΔΔCt method [36]. The mean of the fold changes and the standard deviation were calculated in three independent experiments.

Primers used in the experiments: rdU1 Upper Primer 5'-CAGCATTTGGAGGTG AAGTT-3' (position 384 pol32 cDNA); rdL1 Lower Primer 5'-CGACTTTGCTGG CTCTGATT-3' (position 568 pol32 cDNA); rp49 Upper Primer 5'–ATCGGTTACGGATCGAACAA-3'; rp49 Lower Primer 5'-GACAATCTCCTTGCGCTTCT-3'.

Embryo fixation and staining

0–4 h embryos were collected and fixed as previously described [37]; chromatin was visualized by staining with 4,6-diamino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) and images acquired using an epifluorescence microscope equipped with a cooled CCD camera.

Chromosome cytology

Colchicine-treated metaphase chromosome preparations stained with 4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) from larval brains were prepared and analyzed as previously described [38]. Brains were dissected in 0.7% sodium chloride, incubated with 10−5 M colchicine in 0.7% sodium chloride for 1 h, and treated with hypotonic solution (0.5% sodium citrate) for 7 min. Mitotic chromosome preparations were analyzed using a Zeiss Axioplan epifluorescence microscope (Carl Zeiss, Obezkochen, Germany) equipped with a cooled CCD camera (Photometrics Inc., Woburn, MA).

Radiosensitivity assay

X-irradiation (2.5 Gy) was performed using a Gilardoni X-ray generator operating at 250 kV and 6 mA at a dose rate of 0.75 Gy/min. Cytological analysis from each genotype was set up in duplicate, one for the analysis of spontaneous chromatid breaks as a control, and another for X-ray treatment. Third instar larvae were irradiated with a dose of 2.5 Gy (corresponding to 250 rad) of X-rays generated by a Gilardoni apparatus (mod. MLG 300/6-D; 250 kV, 6 mA, 0.2 mm copper; Gilardoni, Lecco, Italy). Following a 3 h recovery time, brains were dissected and treated as previously described for cytological analysis. We assessed the presence of chromatid breaks (CD), which are defined as chromatid discontinuities with displacement of the broken segment, and the presence of isochromatid breaks (ISO), defined as two chromatid breaks regarding two different chromatids of the same chromosome.

Wing Spot Assay

To evaluate the rate of DNA breakage and/or mitotic recombination in null pol32 flies, we used the Drosophila Somatic Mutation and Recombination Test (SMART). Wings were dissected from flies and analyzed under a compound microscope at 400x magnification. The frequency of spots is calculated as the number of observed spots divided by the number of wings analyzed. Chi-square analysis was used to statistically analyze SMART test data; for Chi-square value calculation, large spots (due to their very low number) were added to the small spots.

Mutagen treatment

Five-day-old pol32 NR42/Cy females were crossed to pol32 R2 /Cy males for 3 days at 25°. The eggs were allowed to hatch for a further 24 h and then 500 μl of the mutagens EMS (SIGMA CAS No. 62-50-0) or ENU (Sigma-CAS No. 759-73-9), at proper molarity in 5% sucrose, was added to the food. Surviving heterozygous and homozygous adult flies were recorded; a ratio was calculated by dividing the number of pol32 NR42 /pol32 R2 flies (phenotypically Cy +) by the number of heterozygous pol32 NR42 /Cy and pol32 R2 /Cy flies (phenotypically Cy) at various mutagen concentrations.

PEV and eye pigment quantification

The effect of pol32 alleles on variegation of In(1)w m4h chromosome was analyzed by crossing C(1;Y)3, In(1)FM7, w 1 m 2 B/In(1)w m4h ; pol32 NR42 /In(2LR)Gla females to 3 types of males without a free Y chromosome: either (i) C(1;Y)3, In(1)FM7, w 1 m 2 B/0; pol32 R2 /Sco, (ii) C(1;Y)3, In(1)FM7, w 1 m 2 B/0; pol32 rds/Sco or (iii) C(1;Y)3, In(1)FM7, w 1 m 2 B/0; pol32 rd1 /Sco, and 3 types of males with a free Y chromosome: either (iv) C(1;Y)3, In(1)FM7, w 1 m 2 B/Y; pol32 R2 /Sco, (v) C(1;Y)3, In(1)FM7, w 1 m 2 B/Y; pol32 rds/Sco or (vi) C(1;Y)3, In(1)FM7, w 1 m 2 B/Y; pol32 rd1 /Sco. This allows us to recover male offspring with identical genotypes, differing only in whether they have a Y chromosome, to monitor the effect of the Y on the extent of variegation. All crosses were performed at 25° to prevent temperature effects on variegation. Extraction of the eye pigments and measurement were done according to [39]. Newly hatched males were aged for 6–9 days and 15 excised heads were placed into 1 ml of 30% ethanol acidified to pH 2 with HCl for 3 days. Each sample was split into two tubes for duplicate processing and optical absorbance was measured at 480nm. The two readings for each sample were averaged. Measurement for each line contained from 4 to 12 replicates. Standard deviation was calculated for the values obtained.

To test whether the pol32 mutation affects TPE, we used the yw; p[w + ]39C-58, and yw; p[w + ]39C-50 reporter strains with mini-w + inserted near the telomere of 2R (T2R), and yw; p[w + ]39-C5 with mini-w + insertion in 2L (T2L), as well as the yw; p[w + ]39C-31 and yw; p[w + ]39C-62 strains carrying mini-w + in 3R (T3R) [40,41]. Homozygous females from each strain were crossed to w 1118 ; pol32 NR42 /Cy males and the eye phenotypes of the F1 double heterozygous progeny were analyzed. To examine TPE in pol32 NR42 homozygotes, F1 females from each cross were mated to w 1118 ; pol32 NR42 /Cy males. Male and female progeny phenotypically p[w + ] pol32 -, arising from independent assortment or from exchange events between pol32 NR42 and T2L p[w + ] or T2R p[w + ] chromosomes, were examined for eye pigmentation.

Results

New alleles of pol32

To obtain null alleles of pol32 (CG3975), we recovered imprecise excisions of P elements flanking the locus (Fig. 1). pol32 R2 was obtained by the mobilization of P element P{PZ}ms(2)1006, which is inserted in the 5’ UTR of pol32, while pol32 NR42 comes from excision of the P element P{EPgy2}CG3975 EY15283 inserted downstream of the 3’ UTR of pol32.

Homozygous pol32 NR42 and pol32 NR42/pol32 R2 trans-heterozygous mutants are female sterile; males are fertile (87 individuals/male; n = 15). Females show short, thin bristles (Fig. 2A) and moderate etching of abdominal tergites; the eggs have apparently normal chorion morphology but don't hatch. Null males have a more severe bristle and abdomen phenotype than females. Molecular characterization of pol32 R2 and pol32 NR42 shows that in both lines the majority of the predicted open reading frame is deleted; pol32 NR42 retains the putative first 180 aa, pol32 R2 retains the last 109 aa. pol32 R2 lethality is due to the deletion of 5' neighboring l(2)35Cc gene.

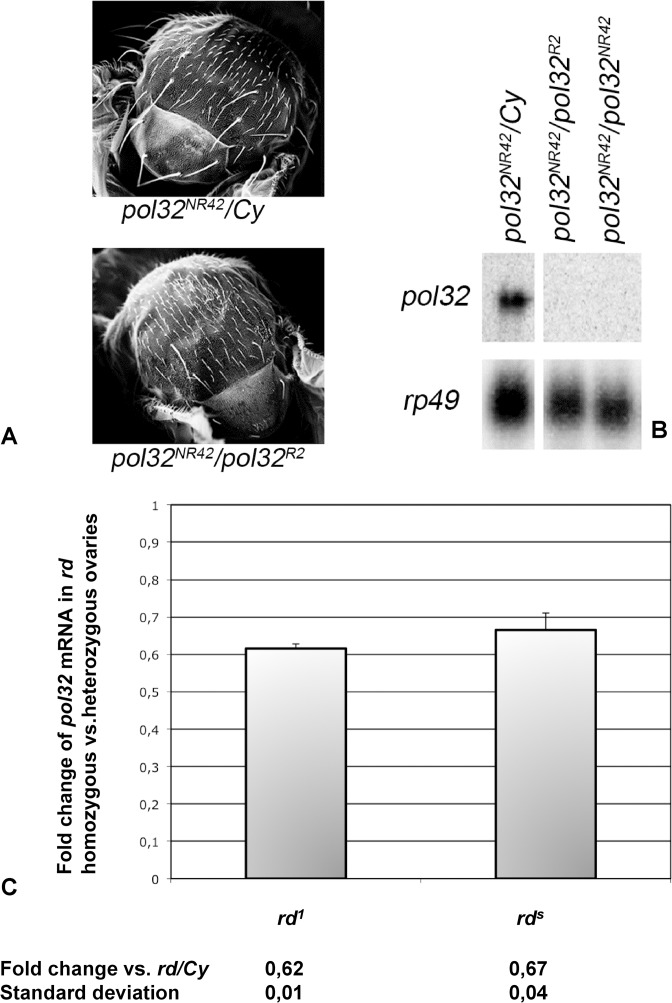

Fig 2. pol32 expression is altered in pol32 mutants.

(A) Scanning electron micrographs of adult thoraxes: heterozygous pol32 NR42 /Cy shows a wild-type bristle pattern (upper) while null pol32 NR42 /pol32 R2 shows bristles which are shorter or absent (lower). (B) Northern blotting of total RNA extracted from ovaries of the indicated genotypes, hybridized with pol32 cDNA. A single transcript of about 1.5 Kb is evident in the wild-type ovaries, while no transcript is detectable in the null mutants; hybridization with a ribosomal protein 49 (rp49) cDNA probe is used as a gel-loading control. (C) qRT-PCR analysis on pol32 transcript in rd 1 and rd s homozygous vs. heterozygous. The results come from three independent experiments. Below are indicated the fold change values calculated as reported in Materials and Methods and the standard deviation.

Northern blot analysis shows that the Pol32 transcript of about 1.5 Kb in pol32 NR42 /Cy ovaries is missing in the trans-heterozygous pol32 NR42 /pol32 R2 and in the homozygous pol32 NR42 /pol32 NR42 ovaries (Fig. 2B).

The physical phenotype reminded us of a mutation called reduced (rd) [42], described in Lindsley and Zimm [28], located in region 35C3-C5 of the II chromosome [43]. Two alleles, rd 1 and rd s, are reported to show “bristles reduced in length and thickness, males more extreme than females; males are fertile, but rd 1 females may be sterile” [28]; we refer to this as the rd phenotype.

To test whether pol32 corresponds to reduced, we did complementation analysis assessing the rd phenotype in pol32 R2 /rd 1, pol32 R2 /rd s, pol32 NR42 /rd 1 and pol32 NR42 /rd s trans-heterozygotes. The adults in all genetic combinations show the bristle and the abdomen phenotypes, supporting that pol32 and reduced are synonyms. We then did a molecular characterization of rd 1 and rd s. The rd s mutant contains the transposable element 412, 4 bp ahead of the translational start codon ATG (Fig. 1). The rd 1 allele contains a DNA insertion of approximately 8 Kb, in the middle of the CDS.

To analyze pol32 expression pattern in rd s and rd 1 mutants, we performed a qRT-PCR on the RNA extracted from homozygous ovaries compared to the heterozygous ovaries. We tested the oligo pairs on the DNA coming from the homozygotes for the two mutations and we obtained amplicons of the right size. Both rd s and rd 1 mutants exhibited a reduction (almost 40%) of the pol32 transcript (Fig. 2C). The difference between the fold change values between the two mutants is not meaningful (p = 0.35 calculated by 2-tailed t-test). Our phenotypic and molecular data identify rd mutants as pol32 alleles; we will henceforth refer to rd s and rd 1 as pol32 rds and pol32 rd1, respectively.

Pol32 is essential in the early stages of embryogenesis

To investigate the female sterility phenotype, trans-heterozygotes for pol32 alleles over the deficiency pol32 R2 and in various heteroallelic combinations, were crossed to pol32 NR42 homozygous males (A) or wild-type Oregon-R (B) (Table 1). Eggs produced from null pol32 females, pol32 R2 /pol32 NR42 (Cross 1A), don’t hatch and the lethality is not rescued by the paternal pol32 + allele (Cross 1B). Eggs from pol32 R2/pol32 rd1 and pol32 R2 /pol32 rds females (crosses 2A and 3A, respectively), can infrequently escape early embryonic lethality. pol32 R2 /pol32 rd1 embryos reach the larval and pupal stages with very few individuals reaching the adult stage; pol32 R2 /pol32 rds individuals show an earlier lethality and mostly die as larvae. However, the nearly complete rescue of the embryonic lethal phenotype by wild-type paternal allele (crosses B), indicates that both alleles are partial loss-of-function alleles, pol32 rds being more severe than pol32 rd1. Maternal pol32 product is critical in the early stages of embryogenesis and a low level of it is sufficient to reach the zygotic stage, when zygotic genes are activated, but not enough to complete development.

Table 1. Embryonic lethal effect of pol32 mutations.

| % of total progeny surviving | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crosses | Maternal genotype | No. of examined embryos | Hatched | III Instar larvae | Pupae | Adults | |

| 1A | pol32 R2 /pol32 NR42 | 1032 | 0 | ||||

| 2A | pol32 R2 /pol32 rd1 | 745 | 11.9 | 6.6 | 5.9 | 0.7 | |

| 3A | pol32 R2 /pol32 rds | 1112 | 6.7 | 0.3 | 0.02 | 0 | |

| 4A | pol32 rd1 /pol32 rds | 366 | 12.8 | 6.3 | 5.2 | 2.5 | |

| 1B | pol32 R2 /pol32 NR42 | 761 | 0 | ||||

| 2B | pol32 R2 /pol32 rd1 | 155 | 80.6 | 71.6 | 64.5 | 41.9 | |

| 3B | pol32 R2 /pol32 rds | 166 | 80.7 | 70.5 | 58.4 | 44.0 | |

| 4B | pol32 rd1 /pol32 rds | 235 | 87.7 | 81.3 | 78.7 | 65.5 | |

Males in A crosses are pol32 NR42 homozygous, in B crosses are wild-type Oregon-R.

A low percentage of embryos from pol32 R2 /pol32 rds and pol32 R2 /pol32 rd1 mothers are able to hatch and the hatching frequency is increased when these females are crossed to wild-type males. This suggests a zygotic role for Pol32 during embryogenesis.

To test if the arrest of the developing embryos was due to the inability of oocytes to repair DSBs during meiotic recombination in the absence of Pol32, we created double mutant pol32 mei-W68 flies. Drosophila mei-W68 mutants lack meiotic DSBs [28], so double mutants should overcome the arrest in embryogenesis. We compared the embryos produced by pol32 R2 /pol32 NR42, and pol32 R2 mei-W68/ pol32 NR42 mei-W68 homozygous mothers.

Embryos were collected during 0–4 h time period, fixed and stained with DAPI to visualize the nuclei. Essentially, we can classify the mutant embryos into 3 phenotypic classes, and between single and double mutant embryos there is no significant change in the frequencies and in the types of the observed phenotypes (Table 2 and S1 Fig.). Approximately 11% of the pol32 - mutant embryos show a polar body with a star like structure with additional or fragmented chromosomes; about 57% of the embryos arrest in mitotic cycles 1 to 6 of with uneven distribution of nuclei; the remaining 31% of embryos, that we define as degenerated, show bubble-like formations and no chromatin is detectable (S1 Fig.). In the mutant embryos we count no more than 64 nuclei and no embryo forms polar cells. When 0–4 h mutant embryos are aged for an additional 4 h all embryos appear degenerated. To see if embryo degeneration is an artifact of the collection time period, we decreased this interval to 1 h. The percentage of degenerated embryos decreased by up to a third, suggesting that about 20% of the embryos observed in the 0–4 h collection degenerate after nuclear division arrest, while another 10% could degenerate due to defects during oogenesis.

Table 2. Frequencies of embryonic phenotypes observed in 0–4 h collection from pol32 R2 /pol32 NR42 and pol32 R2 mei-W68/pol32 NR42 mei-W68 mothers.

| Maternal genotype | 1 nucleus (%) | 1–6 nuclear division (%) | 7–16 nuclear divisions(%) | Degenerate (%) | No. of counted embryos |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oregon-R | 2 | 10 | 88 | 0 | 200 |

| pol32 R2 /pol32 NR42 | 11.4 | 57.3 | 0 | 31.2 | 420 |

| pol32 R2 mei-W68/ pol32 NR42 mei-W68 | 9.2 | 61.7 | 0 | 29.2 | 379 |

Pol32 functions as a subunit of both replicative and TLS pols, but the defects exhibited by the pol32 mutant embryos seem to be essentially due to the role of Pol32 as a subunit of replicative Polδ as suggested by Rong [13]. These mutants prevent the correct replication of DNA during the fast syncytial nuclei divisions of the embryos.

Pol32 is required for chromosome stability

a. X-ray sensitivity

Although null pol32 homozygous flies are fully viable, colchicine-treated larval brain squashes from pol32 null mutants revealed a high frequency of spontaneous chromosome breakage. Of the mitotic pol32 - cells, 5.5% displayed chromosome breaks, whilst the frequency in control cells was approximately 0.3% (Table 3). These breaks involve either one chromatid (CD) or both sister chromatids (isochromatid break, ISO) and are characterized by the simultaneous presence of both the acentric and the centric fragments (Fig. 3).

Table 3. Frequencies of chromatid (CD) and isochromatid (ISO) breaks observed in pol32 null mutant brains.

| IR treatment(Gy) | Genotype | No. of brains | No. of scoredcells | % of cells with breaks | % of cells with >5 breaks per cell |

| 0 | +/+ | 6 | 618 | 0.3 | 0 |

| pol32 NR42 /pol32 R2 | 8 | 1906 | 5.5 | 0 | |

| 2.5 | +/+ | 4 | 394 | 8.9 | 0 |

| pol32 NR42 /pol32 R2 | 4 | 488 | 58.5 | 1.8 |

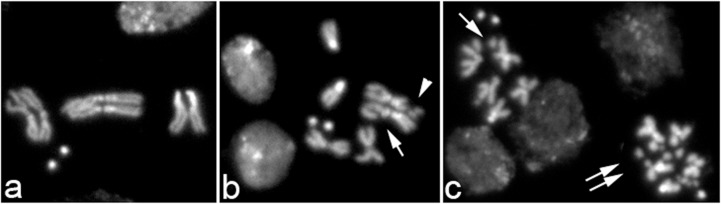

Fig 3. Mutations in pol32 cause chromosome breakage.

Representative panels of metaphases from (a) wild-type and (b, c) pol32 NR42 /pol32 R2 brains, showing CD (arrow), ISO breaks (head arrow) and extensive chromosome fragmentation (double arrows).

To substantiate the finding that Pol32 is required to prevent chromosome breakage, we treated mutant and control larvae with X-rays. Third instar larvae were irradiated with 2.5 Gy and after a 3 h recovery, brains were dissected and then incubated in colchicine for 1 h before fixation. The results show that pol32 mutant cells are considerably more sensitive than wild-type cells to the induction of chromosome breaks (Table 3). 58.5% of the mitotic brain cells from irradiated pol32 mutant larvae displayed chromosome breaks, compared to the 8.9% of chromosome breaks induced in control brains. Moreover, in 1.8% of the aberrant metaphases from treated pol32 larvae, we detected extensive chromosome fragmentation (more than 5 chromosome breaks per cell), which is not present in treated control cells (Fig. 3). Thus, pol32 function is essential both for preventing spontaneous chromosome breakage and for repairing IR-induced DNA damage.

b. mitotic chromosome breakage

The Drosophila Somatic Mutation and Recombination Test (SMART), also known as the Wing Spot Assay, is routinely used for a qualitative and quantitative evaluation of genetic alteration induced by mutants defective in DNA repair. It detects a loss of heterozygosity (LOH) resulting from gene mutation, chromosome rearrangement, chromosome breakage and mitotic recombination [44].

SMART employs the wing cell recessive markers multiple wing hairs (mwh, 3–0.7) and flare 3 (flr 3, 3–38.8) in transheterozygous mwh +/+ flr 3 individuals. When a genetic alteration is induced in a mitotically dividing cell of a developing wing disc, it may give rise to a small (1–2 cells) or large clone(s) (> 3 cells) of mutant mwh and/or flr 3 cells (a “spot”) visible on the wing surface of the adult fly. Two types of spots can be produced: (i) single mwh or flr 3 spots and (ii) twin mwh and flr 3 spots (patches of adjacent flr 3 and mwh cells). The types of clone can reveal the mutational mechanisms involved in clone production; single spots are produced by somatic point mutations, chromosome aberrations or mitotic recombination; twin spots originate exclusively from mitotic recombination. We used the SMART test to evaluate the rate of DNA breakage and/or mitotic recombination in null pol32 flies. We compared the frequencies of single spots and twin spots observed using the two genotypes mwh/TM6 and mwh +/+ flr 3, in wild-type and pol32 - backgrounds (Table 4). Males pol32 NR42 /Cy; mwh jv/TM6, Tb e were crossed to pol32 R2 /Cy; mwh jv/TM6, Tb e females and wing blades of pol32 R2 /pol32 NR42 ; mwh/TM6, Tb e individuals were scored for mwh single spots arising in cells rendered hemizygous or homozygous due to a deletion or mutation event; mitotic recombination products between the balancer chromosome TM6 and the normal mwh chromosome are inviable.

Table 4. Wing spot test data in pol32 null mutant.

| Genotypes | Total wings | Spots per fly | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Small single spots | Large single spots | Small twin spots | Large twin spots | ||||||

| (1–2 cells) | (>2 cells) | (1–2 cells) | (>2 cells) | ||||||

| Fr. | No. | Fr. | No. | Fr. | No. | Fr. | No. | ||

| +/+; mwh/TM6 | 108 | 0.01 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| pol32 R2 /pol32 NR42 ; mwh/TM6 | 94 | 1.0 | 98 | 0.02 | 2 | 0 | 0 | ||

| +/+; mwh +/+ flr 3 | 80 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| pol32 R2 /pol32 NR42 ; mwh +/+ flr 3 | 120 | 0.9 | 105 | 0.05 | 6 | 0.01 | 1 | 0.03 | 4 |

Fr., frequency of spots calculated as the number of observed spots divided by the number of wings analyzed.

No., number of spots.

Males pol32 NR42 /Cy; mwh jv/TM6, Tb e were crossed to pol32 R2 /Cy; flr3/TM6, Tb e. Among the progeny, individuals pol32 R2 /pol32 NR42 ; mwh +/+ flr 3 can produce single and twin spots. Twin spots are exclusively derived from mitotic recombination. Both pol32 R2 /pol32 NR42 ; mwh/TM6 and pol32 R2 /pol32 NR42 ; mwh +/+ flr 3 progeny produce single spots, with the mean frequency of the mwh or mwh/flr 3 spots per wing of approximately 1.0 in both genotypes (Table 4). There is a significant effect of the pol32 mutation on the production of single spots (Chi-square = 189.12, df = 2, p<1E-10). The very low number of twin spots compared to single spots in null pol32 flies indicates that almost all of the events arise not from recombination, but from chromosome breaks. These results confirm the participation of Pol32 in the repair of DNA lesions that give rise to chromosome breakage.

c. sensitivity to monoalkylating agents

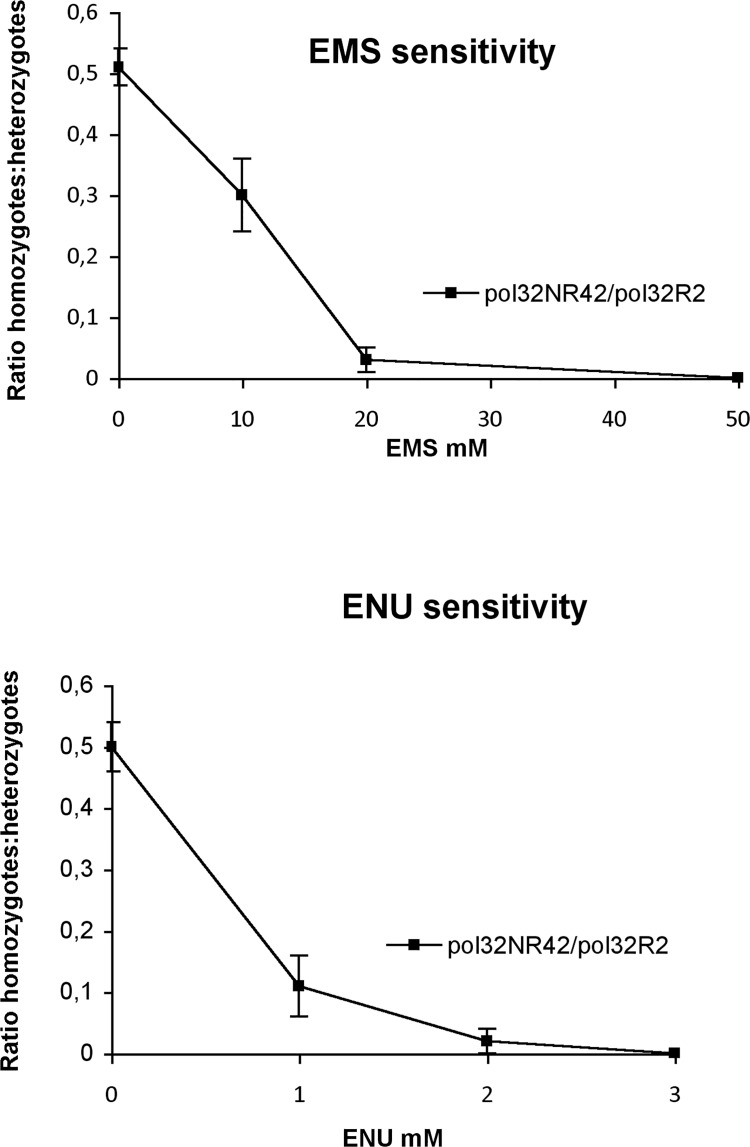

We tested the sensitivity of pol32 null mutant to the monoalkylating agents ethylmethanesulphonate (EMS) and N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea (ENU) at increasing concentrations. We know that pol32 mutants are extremely sensitive to MMS [13], an alkylating agent inducing mainly chromosome aberrations [45]. Due to their different reactive mechanisms, the repair of DNA alterations induced by MMS, EMS and ENU mutagens requires various DNA repair processes [46–48]. Larvae from a cross of pol32 NR42 /Cy females by pol32 R2 /Cy males were treated with EMS and ENU, and the adult flies were scored for heterozygosity or homozygosity. The results (Fig. 4 and S1 Table) indicate a significant loss of viability of homozygous pol32 R2 /pol32 NR42 flies compared to their heterozygous siblings, at all concentrations of the tested mutagens, with total lethality at 50mM EMS and 3mM ENU. Thus pol32 −flies are hypersensitive to both mutagens, suggesting the participation of Pol32 in the repair pathways triggered by these monoalkylating agents.

Fig 4. pol32 null mutants are sensitive to EMS and ENU.

Newly- hatched larvae from a cross of pol32 NR42 /Cy X pol32 R2/Cy were treated with EMS and ENU at various concentrations; the ratio of homozygous pol32 NR42 / pol32 R2: heterozygous pol32 - /Cy surviving adults was plotted against mutagen concentration. The lower frequency of pol32 NR42 /pol32 R2 homozygous flies observed at increasing mutagen doses demonstrates the mutant hypersensitivity to EMS and ENU. Error bars correspond to Standard Deviation determined from at least five independent experiments.

pol32 mutants suppress Position Effect Variegation

Chromatin modifications are necessary for the recognition of DNA lesions and for access to various protein complexes during DNA repair [49–50]. A role for epigenetic changes in a chromatin-dependent repair mechanism in DSB repair is now emerging [51]. DNA repair-deficient mutants (e.g. mus genes) are potential candidates for modifiers of position effect variegation (PEV) [52–53], so we looked at whether Pol32 is a PEV modifier.

PEV is an epigenetic phenotype produced by the inactivation of a euchromatic gene when relocated in, or close to, the heterochromatin [54]. PEV may be altered by suppressor or enhancer mutations [55]. Variegation is also suppressed by the addition of extra heterochromatin, such as a Y chromosome, and enhanced by decreasing the heterochromatin, which occurs in X/0 males [56].

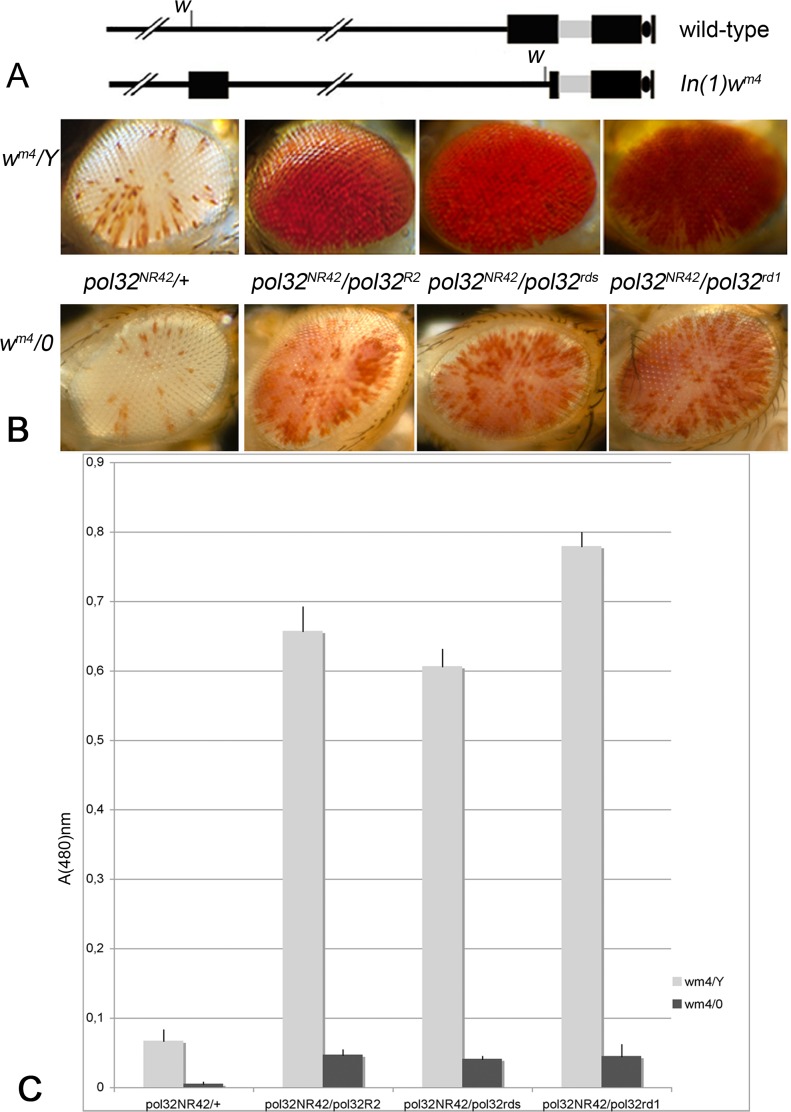

We used the inversion chromosome, In(1)w m4h (referred to here as w m4) in which the white (w) gene is moved close to the basal heterochromatin of the X chromosome (Fig. 5A), and the new position induces a variegated pigment phenotype in the eyes. The amount of eye pigment is diagnostic of the strength of PEV. Individuals carrying pol32 alleles in various genetic combinations were analyzed for variegation of w in the w m4 chromosome. Fig. 5B displays the expression of w both in the presence and in the absence of the Y chromosome in pol32 - males. The strong inactivation of w in w m4/Y males leaves only rare and small dots of red pigment in the eyes; in w m4/0 males the eyes appear quite white. In the state of partial (pol32 NR42/pol32 rds and pol32 NR42/pol32 rd1) or complete (pol32 NR42 /pol32 R2) loss of Pol32, mottling of the phenotype increases in w m4/0 males, and w m4/Y males are almost fully pigmented. Spectrophotometrical quantization of the pigment level confirms a correlation between the eye phenotype and the amount of drosopterin (Fig. 5C).

Fig 5. Mutations in pol32 suppress PEV.

(A) Diagram of In(1)w m4 chromosome. The black boxes represent heterochromatic regions, the gray box represents the heterochromatic bb locus. (B) Phenotypic effect of pol32 mutations on the expression of white (w) in In(1)w m4 males of the indicated genotypes. Inactivation of w is seen in eyes with only rare and small patches of red pigment. The PEV suppression of the Y chromosome, enhances pigmentation in X/Y with respect to X/0 males. w expression is enhanced in all pol32 allelic combinations. (C) Spectrophotometric quantitation of eye pigment. Error bars represent the standard error.

PEV may also occur on genes inserted into the telomeres, a silencing phenomenon called telomere position effect (TPE) [57,58]. We tested the effect of null pol32 mutation on TPE, using a mini-white + reporter gene inserted into telomere-associated sequences (described in Materials and Methods). Analyzing eye pigmentation in both heterozygous and homozygous pol32 NR42 flies carrying the w + reporter, we found no differences compared to controls. This is not surprising: systematic searches for TPE and PEV modifiers reveal that the majority of mutations that affect PEV have no effect on TPE, suggesting that PEV and TPE differ mechanistically [41,58]. The pol32 mutation suppresses PEV and does not affect TPE.

Discussion

pol32, DNA replication and repair

The Pol32 protein is involved in several processes that promote genome stability, which can be seen from many studies conducted in yeast. By analyzing Drosophila phenotypes in null or hypomorph pol32 mutants, we defined the specific processes in which Pol32 is required. It has an essential function in DNA replication during the early embryonic divisions, corresponding to the period in which each nucleus replicates its DNA and divides in less than 10 minutes. The small percentage of embryos that we define as degenerated, together with the embryos showing a polar body-like structure, may also indicate a role for Pol32 during oogenesis. Cytogenetic analysis shows that chromosome breaks characterize the pol32 mutant and that the mutants have an increased sensitivity to X-rays, providing evidence that Pol32 ensures chromosome integrity in somatic cells. The high frequency of single spots with respect to twin spots in the SMART test also supports a Pol32 role in the repair of DNA lesions that cause chromosome breaks. The increased sensitivity of pol32 mutants to the monoalkylating agents ENU and EMS, as well as MMS, suggests the involvement of Pol32 in diverse DNA repair pathways.

In an RNAi-based screen to identify MMS survival genes in D.melanogaster, the analysis of the protein interactome placed Pol32 (as CG3975) in BER (Base Excision Repair), NER (Nucleotide Excision Repair) and TOR (Target of Rapamycin) pathways [12].

In mammalian cells, BER—through DNA polymerase β (Polβ), Polδ and Polε—is the main pathway that cells use to repair abasic (AP) sites [59,60]. In D. melanogaster, which lacks the Polβ ortholog, the involvement of DmPolζ has been suggested in AP site repair [48]. Since the deletion of Pol32 leaves both Polδ and Polζ structurally incomplete, analysis of pol32 mutants combined with knockout in the single subunits of these Pols and of the enzymes involved in the other pathways will clarify the relationship of Pol32 in the DNA damage survival network.

pol32 and PEV

We found that pol32 mutations suppress PEV in the w m4 chromosome. This suggests an involvement of Pol32 in the induction of chromatin state changes. A switching role that permits the replacement of Polδ with Polζ and vice versa has been proposed in yeast for the complex of Pol32 and Pol31. This accessory protein complex, retained on DNA at replication-blocking lesions, exchanges Polδ with Polζ during TLS DNA synthesis, allowing replication to proceed [2–4]. The mechanism by which these events occur is unknown, but they require the interaction of Pol32-Pol31, through Pol32, with the processivity factor PCNA.

Chromatin modifications occur during the DNA damage response and Pol32 could enter in this process. An involvement of Pol32 in the induction of chromatin state changes may include both its activities, DNA replication and repair.

The abnormal bristles and tergites phenotype, observed in pol32 - mutants, recalls bobbed (bb) mutants, which are caused by a reduction in rRNA synthesis [61]. Investigations are required to determine whether Pol32 can affect the rDNA repeat number and/or the chromatin structure of this region. Genetic analyses have demonstrated the influence of some repair defective mutations on the chromosomal stability of the rDNA cluster [62,63]. An effect of Pol32 on rDNA repeat expansion has been seen in yeast [64]. Human p66, the ortholog of Pol32, interacts directly with WERNER protein (WRN); in cells from individuals with a deficiency in WRN helicase, rDNA gene arrays display an increased proportion of palindromic structures [65,66]. Finding an evolutionary conservation of functional interactions of p66 with WRN and with components of the DNA repair pathway may render Drosophila an interesting model for studying relationships among genes associated with genomic instability.

Supporting Information

Embryos collected at 0–4 h from wild-type Oregon-R (a) and pol32 R2 / pol32 NR42 (b-e) mothers, stained with DAPI and viewed as whole mounts. (a) Wild-type embryo at blastoderm stage: nuclei are uniformly distributed along the cortex; in the middle of the embryo dividing nuclei are visible; pole cells are visible at the posterior end. (b) pol32 R2 /pol32 NR42 embryo showing asynchronous nuclear divisions, abnormal spatial arrangements of syncytial nuclei; the difference in intensity of staining suggests a different level of ploidy. Mutant embryos at higher magnification show chromatin fragmentation (c), metaphase-anaphase with dispersed chromosomes and chromatin (d), anaphase chromosome bridges (e).

(TIF)

(DOC)

Acknowledgments

We thank Bloomington Drosophila Stock center for Drosophila strains; L. Wallrath and G. Cenci for TPE assay strains; P. D’addabo for technical assistance; L. G. Robbins for assistance in statistical analysis and E. E. Swanson for comments on the manuscript.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by leftover of grants from Università degli Studi di Bari and Ministero dell’istruzione, dell’Università e della ricerca. This work was also supported by the Epigenomics Flagship Project EpiGen, of the Italian National Research Council (SP). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Johansson E, Majka J, Burgers PM. Structure of DNA polymerase delta from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 2001;276: 43824–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Baranovskiy AG, Lada AG, Siebler HM, Zhang Y, Pavlov YT, Tahirov TH. DNA polymerase and switch by sharing accessory subunits of DNA polymerase. J. Biol. Chem. 2012; 287: 17281–7. 10.1074/jbc.M112.351122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Johnson RE, Prakash L, Prakash S. Pol31 and Pol32 subunits of yeast DNA polymerase delta are also essential subunits of DNA polymerase zeta. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109: 12455–60. 10.1073/pnas.1206052109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Makarova AV, Stodola JL, Burgers PM. A four-subunit DNA polymerase zeta complex containing Pol delta accessory subunits is essential for PCNA-mediated mutagenesis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40: 11618–26. 10.1093/nar/gks948 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Langston LD, O'Donnell M. Subunit sharing among high- and low-fidelity DNA polymerases. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109: 1228–9. 10.1073/pnas.1112078109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Prindle MJ, Loeb LA. DNA polymerase delta in DNA replication and genome maintenance. Environ Mol Mutagen. 2012;53: 666–82. 10.1002/em.21745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Burgers PMJ, Gerik KJ. Structure and processivity of two forms of Saccharomyces cerevisiae DNA polymerase delta. J. of Biological Chemistry. 1998;273: 19756–19762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Zuo S, Gibbs E, Kelman Z, Wang TS, O'Donnell M, MacNeill SA, et al. DNA polymerase isolated from Schizosaccharomyces pombe contains five subunits. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94: 11244–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Liu L, Mo J, Rodriguez-Belmonte EM, Lee MY. Identification of a fourth subunit of mammalian DNA polymerase delta. J Biol Chem. 2000;275: 18739–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Aoyagi N, Matsuoka S, Furunobu A, Matsukage A, Sakaguchi K. Drosophila DNA polymerase delta. Purification and characterization. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269: 6045–6050. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Reynolds N, MacNeill SA. Characterisation of XlCdc1, a Xenopus homologue of the small (PolD2) subunit of DNA polymerase delta; identification of ten conserved regions I-X based on protein sequence comparisons across ten eukaryotic species. Gene.1999;230: 15–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ravi D, Wiles AM, Bhavani S, Ruan J, Leder P, Bishop AJ. A network of conserved damage survival pathways revealed by a genomic RNAi screen. PLoS Genet. 2009;5: e1000527 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kane DP, Shusterman M, Rong Y, McVey M. Competition between replicative and translesion polymerases during homologous recombination repair in Drosophila. PLoS Genet. 2012;8: e1002659 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gray FC, Pohler JR, Warbrick E, MacNeill SA. Mapping and mutation of the conserved DNA polymerase interaction motif (DPIM) located in the C-terminal domain of fission yeast DNA polymerase delta subunit Cdc27. BMC Mol Biol. 2004;5: 21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Haracska L, Unk I, Johnson RE, Johansson E, Burgers PM, Prakash S, et al. Roles of yeast DNA polymerases delta and zeta and of Rev1 in the bypass of abasic sites. Genes Dev. 2001;15: 945–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Huang ME, Rio AG, Galibert MD, Galibert F. Pol32, a subunit of Saccharomyces cerevisiae DNA polymerase delta, suppresses genomic deletions and is involved in the mutagenic bypass pathway. Genetics. 2002;160: 1409–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hanna M, Ball LG, Tong AH, Boone C, Xiao W. Pol32 is required for Pol zeta-dependent translesion synthesis and prevents double-strand breaks at the replication fork. Mutat Res. 2007;625: 164–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lydeard JR, Jain S, Yamaguchi M, Haber JE. Break-induced replication and telomerase-independent telomere maintenance require Pol32. Nature. 2007;448: 820–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bohgaki T, Bohgaki M, Hakem R. DNA double-strand break signaling and human disorders. Genome Integr. 2010;1: 15 10.1186/2041-9414-1-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Jasin M, Rothstein R. Repair of strand breaks by homologous recombination. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2013;5: a012740 10.1101/cshperspect.a012740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Prakash S, Johnson RE, Prakash L. Eukaryotic translesion synthesis DNA polymerases: specificity of structure and function. Annu Rev Biochem. 2005; 74: 317–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Nelson JR, Lawrence CW, Hinkle DC. Thymine-thymine dimer bypass by yeast DNA polymerase zeta. Science. 1996;272: 1646–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lawrence CW, Hinkle DC. DNA polymerase zeta and the control of DNA damage induced mutagenesis in eukaryotes. Cancer Surv. 1996;28: 21–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Esposito G, Godindagger I, Klein U,Yaspo ML, Cumano A, Rajewsky K. Disruption of the Rev3l-encoded catalytic subunit of polymerase zeta in mice results in early embryonic lethality. Curr Biol. 2000;10: 1221–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Eeken JC, Romeijn RJ, de Jong AW, Pastink A, Lohman PH. Isolation and genetic characterisation of the Drosophila homologue of (SCE)REV3, encoding the catalytic subunit of DNA polymerase zeta. Mutat Res. 2001;485: 237–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mintseris J, Obar RA, Celniker S, Gygi SP, VijayRaghavan K, Artavanis-Tsakonas S. DPiM: the Drosophila Protein Interaction Mapping project. 2009; Available: https://interfly.med.harvard.edu/

- 27. Uchimura A, Hidaka Y, Hirabayashi T, Hirabayashi M, Yagi T. DNA polymerase delta is required for early mammalian embryogenesis. PLoS One 2009;4: e4184 10.1371/journal.pone.0004184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lindsley DL, Zimm GG. The Genome of Drosophila melanogaster Academic Press, San Diego, CA; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bier E, Vaessin H, Shepherd S, Lee K, McCall K, Barbel S, et al. Searching for pattern and mutation in the Drosophila genome with a P-lacZ vector. Genes Dev. 1989;3: 1273–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bellen HJ, Levis RW, Liao G, He Y, Carlson JW, Tsang G, et al. The BDGP gene disruption project: single transposon insertions associated with 40% of Drosophila genes. Genetics. 2004;167: 761–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gene disruption Project members. 2001. (Flybase, FB2012_02).

- 32. Robertson HM, Preston CR, Phillis RW, Johnson-Schlitz DM, Benz WK, Engels WR. A stable genomic source of P element transposase in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 1988;118: 461–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Steller H, Pirrotta V. P transposons controlled by the heat shock promoter. Mol Cell Biol. 1986;6: 1640–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Palumbo G, Bonaccorsi S, Robbins LG, Pimpinelli S. Genetic analysis of Stellate elements of Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 1994;138: 1181–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. Molecular Cloning A Laboratory Manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Specchia V, Benna C, Mazzotta GM, Piccin A, Zordan MA, Costa R, et al. aubergine gene overexpression in somatic tissues of aubergine (sting) mutants interferes with the RNAi pathway of a yellow hairpin dsRNA in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 2008;178: 1271–1282. 10.1534/genetics.107.078626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Vincent S, Vonesch JL, Giangrande A. Glide directs glial fate commitment and cell fate switch between neurones and glia. Development. 1996;122: 131–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Gatti M, Bonaccorsi S, Pimpinelli S. Looking at Drosophila mitotic chromosomes. Methods Cell Biol. 1994;44: 371–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Henikoff S, Dreesen TD. Trans-inactivation of the Drosophila brown gene: evidence for transcriptional repression and somatic pairing dependence. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86: 6704–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wallrath LL, Elgin SC. Position effect variegation in Drosophila is associated with an altered chromatin structure. Genes Dev. 1995;9: 1263–1277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Cryderman DE, Morris EJ, Biessmann H, Elgin SC, Wallrath LL. Silencing at Drosophila telomeres: nuclear organization and chromatin structure play critical roles. EMBO J. 1999;18: 3724–3735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Lynch CJ. An analysis of Certain Cases of Intra-Specific Sterility. Genetics. 1919;4: 501–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ashburner M, Misra S, Roote J, Lewis SE, Blazej R, Davis T, et al. An exploration of the sequence of a 2.9-Mb region of the genome of Drosophila melanogaster: the Adh region. Genetics. 1999;153: 179–219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Graf U, Würgler FE, Katz AJ, Frei H, Juon H, Hall CB, et al. Somatic mutation and recombination test in Drosophila melanogaster. Environ Mutagen. 1984;6: 153–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Vogel E, Natarajan AT. The relation between reaction kinetics and mutagenic action of mono-functional alkylating agents in higher eukaryotic systems. I. Recessive lethal mutations and translocations in Drosophila. Mutat Res. 1979;62: 51–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Tosal L, Comendador MA, Sierra LM. In vivo repair of ENU-induced oxygen alkylation damage by the nucleotide excision repair mechanism in Drosophila melanogaster. Mol Genet Genomics. 2001; 265: 327–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Takeuchi R, Ruike T, Nakamura R, Shimanouchi K, Kanai Y, Abe Y, et al. Drosophila DNA polymerase zeta interacts with recombination repair protein 1, the Drosophila homologue of human abasic endonuclease 1. J Biol Chem. 2006;281: 11577–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Chan K, Resnick MA, Gordenin DA. The choice of nucleotide inserted opposite abasic sites formed within chromosomal DNA reveals the polymerase activities participating in translesion DNA synthesis. DNA Repair (Amst). 2013;12: 878–89. 10.1016/j.dnarep.2013.07.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Polo SE, Almouzni G. Chromatin dynamics during the repair of DNA lesions Med Sci (Paris). 2007;23: 29–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Misteli T, Soutoglou E. The emerging role of nuclear architecture in DNA repair and genome maintenance. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10: 243–54. 10.1038/nrm2651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Dronamraju R, Mason JM. MU2 and HP1a regulate the recognition of double strand breaks in Drosophila melanogaster. PLoS One. 2011;6: e25439 10.1371/journal.pone.0025439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Henderson DS, Banga SS, Grigliatti TA, Boyd JB. Mutagen sensitivity and suppression of position-effect variegation result from mutations in mus209, the Drosophila gene encoding PCNA. EMBO J. 1994;13: 1450–1459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Ayoub N, Jeyasekharan AD, Bernal JA, Venkitaraman AR. HP1-beta mobilization promotes chromatin changes that initiate the DNA damage response. Nature. 2008;453: 682–686. 10.1038/nature06875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Spofford JB. Position-effect variegation in Drosophila In: The genetics and biology of Drosophila Vol.1C, edited by Ashburner M and Novitski E. Academic Press, New York; 1976. pp 955–1018. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Sinclair DA, Lloyd VK, Grigliatti TA. Characterization of mutations that enhance position-effect variegation in Drosophila melanogaster. Mol Gen Genet. 1989;216: 328–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Dimitri P, Pisano C. Position effect variegation in Drosophila melanogaster: relationship between suppression effect and the amount of Y chromosome. Genetics. 1989;122: 793–800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Gehring WJ, Clemenz R, Weber U, Kloter U. Functional analysis of the white gene of Drosophila by P-factor-mediated transformation. EMBO J. 1984;3: 2077–2085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Doheny JG, Mottus R, Grigliatti TA. Telomeric Position Effect-A Third Silencing Mechanism in Eukaryotes. PLoS ONE. 2008;3: e3864 10.1371/journal.pone.0003864 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Dianov GL, Hübscher U. Mammalian Base Excision Repair: the Forgotten Archangel. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41: 3483–3490. 10.1093/nar/gkt076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Auerbach PA, Demple B. Roles of Rev1, Pol zeta, Pol32 and Pol eta in the bypass of chromosomal abasic sites in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mutagenesis. 2010;25: 63–9. 10.1093/mutage/gep045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Mohan J, Ritossa FM. Regulation of ribosomal RNA synthesis and its bearing on the bobbed phenotype in Drosophila melanogaster. Dev Biol. 1970;22: 495–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Hawley RS, Tartof KD. The effect of mei-41 on rDNA redundancy in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics.1983;104: 63–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Hawley RS, Marcus CH, Cameron ML, Schwartz RL, Zitron AE. Repair-defect mutations inhibit rDNA magnification in Drosophila and discriminate between meiotic and premeiotic magnification. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1985;82: 8095–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Houseley J, Tollervey D. Repeat expansion in the budding yeast ribosomal DNA can occur independently of the canonical homologous recombination machinery. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39: 8778–8791. 10.1093/nar/gkr589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Kamath-Loeb AS, Johansson E, Burgers PM, Loeb LA. Functional interaction between the Werner Syndrome protein and DNA polymerase delta. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97: 4603–4608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Caburet S, Conti C, Schurra C, Lebofsky R, Edelstein SJ, Bensimon A. Human ribosomal RNA gene arrays display a broad range of palindromic structures. Genome Res. 2005;15: 1079–1085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Embryos collected at 0–4 h from wild-type Oregon-R (a) and pol32 R2 / pol32 NR42 (b-e) mothers, stained with DAPI and viewed as whole mounts. (a) Wild-type embryo at blastoderm stage: nuclei are uniformly distributed along the cortex; in the middle of the embryo dividing nuclei are visible; pole cells are visible at the posterior end. (b) pol32 R2 /pol32 NR42 embryo showing asynchronous nuclear divisions, abnormal spatial arrangements of syncytial nuclei; the difference in intensity of staining suggests a different level of ploidy. Mutant embryos at higher magnification show chromatin fragmentation (c), metaphase-anaphase with dispersed chromosomes and chromatin (d), anaphase chromosome bridges (e).

(TIF)

(DOC)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.