Abstract

Maintenance of the mitochondrial proteome is performed primarily by chaperones, which fold and assemble proteins, and by proteases, which degrade excess damaged proteins. Upon various types of mitochondrial stress, triggered genetically or pharmacologically, dysfunction of the proteome is sensed and communicated to the nucleus, where an extensive transcriptional program, aimed to repair the damage, is activated. This feedback loop, termed the mitochondrial unfolded protein response (UPRmt), synchronizes the activity of the mitochondrial and nuclear genomes and as such ensures the quality of the mitochondrial proteome. Here we review the recent advances in the UPRmt field and discuss its induction, signaling, communication with the other mitochondrial and major cellular regulatory pathways and its potential implications on health and lifespan.

Keywords: mitochondria, aging, proteostasis

Introduction

Mitochondria supply cells with ATP, the cellular energy currency, and are essential for many other aspects of cellular homeostasis, thereby influencing not only cellular metabolism, but also organismal health and lifespan [1,2]. Inborn mitochondrial defects result in severe multisystem diseases and mitochondrial dysfunction also underlies several common metabolic and neurodegenerative diseases [3,4]. Mitochondrial unfolded protein response (UPRmt) is an emerging adaptive stress response pathway, which ensures optimal quality and function of the mitochondrial proteome. UPRmt internally surveys mitochondrial proteostasis and responds to stress signals by activating an intricate mitochondrial protein quality control (PQC) network [5-7]. Here we review the recent literature on mechanisms that trigger UPRmt activation, its signaling pathways, crosstalk with other mitochondrial quality control systems and interactions with the wider network of cellular responses.

Activation of UPRmt

Mitochondria are evolutionarily derived from proteobacteria that evolved in symbiosis within eukaryotic cells [8]. Mitochondria contain multiple copies of the circular mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), a vestige of the proteobacterial genome, which encodes 13 protein constituents of the multiprotein complexes of the electron transport chain (ETC). The remainder of the mitochondrial proteome (~1500 proteins) is transcribed from the nuclear DNA (nDNA). After translation in the cytoplasm, these nuclear encoded proteins are imported, folded and assembled within the mitochondria [9,10]. Four out of five ETC complexes contain proteins encoded in both genomes, requiring a robust synchrony between the mitochondrial and nuclear genome to warrant optimal mitochondrial function [11].

Proteostasis in the mitochondria is ensured by an elaborate protein quality control (PQC) network, composed of two main functional groups of proteins, chaperones and proteases [12,13]. Chaperones mtHsp70, Hsp60 and Hsp10 fold and assemble proteins that are imported into the mitochondria and refold damaged mitochondrial proteins. Excess proteins that are unassisted by chaperones are digested by ATP-dependent PQC proteases, specific for each mitochondrial compartment: the ClpXP and Lon proteases in the matrix, the i-AAA (Yme1L1) and m-AAA proteases (Afg3l2 and Spg7), acting in the intermembrane space (IMS) and matrix, respectively. Upon mitochondrial proteotoxic stress, these PQC chaperones and proteases are induced as a result of a retrograde mitochondria-to-nucleus signaling termed UPRmt. Using mitochondrial chaperones and proteases as UPRmt biomarkers, this PQC pathway has now been established in worms, flies, mammalian cell cultures and mice. Various conditions have been shown to trigger the UPRmt, most of which interfere with the mitochondrial proteostasis either by disturbing the PQC system or by increasing the load of damaged, unfolded or unassembled proteins (table 1).

Table 1.

UPRmt inducing manipulations

| Genetic | Pharmacological | |

|---|---|---|

| protein damage | aggregation prone OTC-Δ [20,22], EndoG [21] overexpression | ROS generator paraquat [23], toxins, produced by pathogenic bacteria [24,25] |

| interference with PQC | knockdown of Hspa9 [19], hsp-60 [17], dnj-21 [17], spg-7 [17] | |

| interference with mitochondrial import and architecture | RNAi of tim-17, tim-23 (RNAi) [14,15], phb-2 [16,17] | arsenic (III) [14] |

| mtDNA depletion | RNAi of mtDNA helicase pif-1 [17], Deletor mice [34] | ethidium bromide [17,45] |

| interference with mitochondrial translation | downregulation of various cytosolic and mitochondrial ribosomal proteins [17,26] | bacterial and mitochondrial translation inhibitors doxycycline and chloramphenicol [26] |

| loss of ETC subunits | cco-1 RNAi [27], isp-1 (qm150) [44], clk-1 (qm30) [44] alleles, RNAi of ND75 [41], Surf1−/− mice [42] | ETC inhibitors antimycin [23,24], rotenone [23] |

| sirtuin activation and mitochondrial biogenesis | sir-2.1 overexpression [29] | PARP inhibitors MRL45696 [30] and AZD2281 [29], NAD+ precursor NR [29], rapamycin [26] |

RNAi based downregulation of components of the mitochondrial protein handling machinery, such as the import proteins TIM-17 and TIM-23 [14,15], the inner membrane protein scaffold PHB-2 [16,17], the PQC protease SPG-7 [17,18] or the chaperone mtHsp70 [19] all induce UPRmt in C. elegans or in mammals. Moreover, increasing the workload of PQC machinery by overexpression of aggregation-prone proteins, such as a mutant form of ornithine transcarbamylase (OTC-Δ and EndoG, also activates UPRmt in mammalian cells [19-21] and flies [22]. On a similar note, the treatment with the reactive oxygen species (ROS) generator paraquat, which increases the amount of damaged proteins, also induces UPRmt in C. elegans [17,23]. Additionally, pathogenic bacteria can induce UPRmt by production of toxins, which antagonize mitochondrial proteostasis [24,25].

Another way to induce UPRmt is by manipulating ETC assembly either by the downregulation or inhibition of single (or groups of) ETC components, which are encoded by either mtDNA or nDNA [26]. This results in a mismatch between mtDNA and nDNA encoded ETC subunits, creating orphaned unassembled subunits, which stay associated with chaperones; this phenomenon is termed mitonuclear protein imbalance [26]. Thus downregulation of ETC subunits by cco-1 (complex IV) RNAi [18,27], in isp-1 (complex III) or clk-1 (ubiquinone synthesis) mutant strains [27,28], or by using pharmacological ETC inhibitors, such as antimycin [23,24] and rotenone [23], activates UPRmt. Additionally, downregulation of mitochondrial ribosomal proteins or treatment with the bacterial (also mitochondrial) translation inhibitors doxycycline or chloramphenicol [26], as well as mtDNA depletion induced by ethidium bromide [17] result in a mitonuclear protein imbalance and consequently induce UPRmt.

Similarly, the activation of mitochondrial biogenesis by resveratrol or rapamycin [26] also reduces the levels of mitochondrially encoded ETC subunits, triggering UPRmt. Boosting NAD+ levels by the NAD+ precursor, nicotinamide riboside (NR), or by inhibiting NAD+ consumption, as seen after treatment with PARP inhibitors [29], also enhances biogenesis, but the raise in NAD+ levels specifically increases the transcription and translation of mtDNA-encoded ETC subunits [30], creating also a mitonuclear imbalance, which triggers the UPRmt. In accordance with these findings related to mitochondrial biogenesis, UPRmt can be activated in worms, only if the perturbation in mitochondrial proteostasis takes place during L3/L4 transition [31], which coincides with a major burst in mitochondrial biogenesis [32], further emphasizing its role in the induction of UPRmt. The induction of UPRmt during biogenesis is in most cases mediated by actvation of sirtuins, protein deacylases, which are major regulators of metabolism and aging [33], namely Sirt1 in mouse or sir-2.1 in worms [29,30,34,35]. In addition to Sirt1, recently, Sirt7 and its downstream target transcription factor GABPβ1 were shown to control the expression of multiple mitochondrial ribosomal proteins, responsible for mitochondrial translation [36]. Although the potential role of Sirt7 in UPRmt induction has not yet been examined, given its major impact on mitochondrial ribosomal proteins [26], Sirt7 might be pivotal for mitochondrial proteostasis, while its deficiency could induce UPRmt.

UPRmt signaling

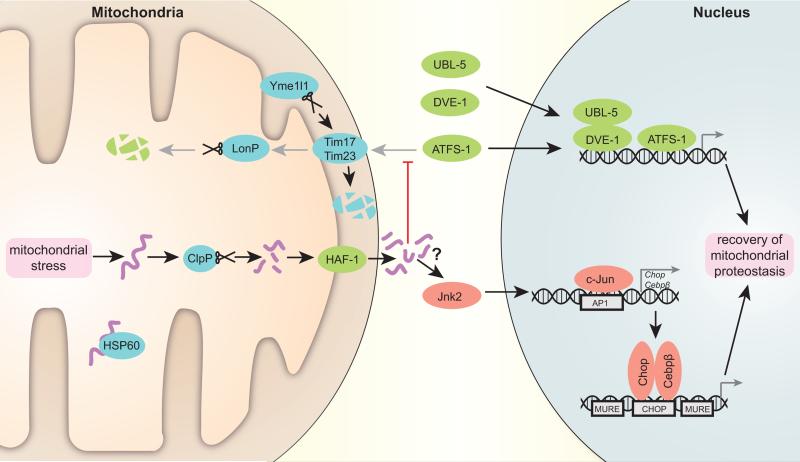

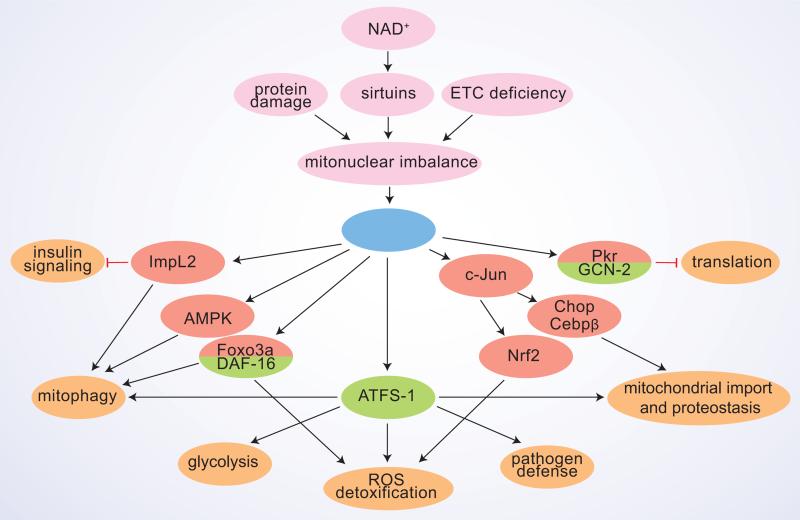

The first trigger for UPRmt in C. elegans is the excess of damaged and unfolded proteins, which are digested by the CLPP-1 protease into small peptides [37], and then transported outside of the mitochondria by the transporter HAF-1 [38] (figure 1). The role of these peptides is unknown yet, but presumably they contribute to weaken mitochondrial import during stress, which on its turn is important for the nuclear translocation of the main UPRmt transcriptional regulator ATFS-1 [15]. ATFS-1 is able to shuttle between mitochondria and nucleus due to presence of a mitochondrial targeting sequence (MTS) and a nuclear localization sequence (NLS). In normal conditions, ATFS-1 is imported and degraded by the Lon protease in the mitochondria, but upon mitochondrial stress ATFS-1 translocates into the nucleus [15]. Together with other transcriptional regulators UBL-5 [39] and DVE-1 [37], which also move into the nucleus in stress conditions, ATFS-1 then induces the transcription of UPRmt targets in the worm. Of note, the Ubl5 protein levels also correlate tightly with UPRmt effector chaperones and proteases in several tissues in the BXD mouse genetic reference population (GRP) and in humans, which indicates that presumably it is also involved in the initiation of the mammalian UPRmt [18]. Interestingly, ATFS-1 does not have an unambiguous sequence homolog in mammals, making it doubtful whether an ATFS-1 counterpart and its shuttling mechanism are conserved in mammalian UPRmt. ATFS-1 induces multiple genes with a pleiotropic outcome. It activates the transcription of mitochondrial chaperones and proteases, as well as that of detoxification enzymes to neutralize the generation of ROS, and of mitochondrial transporters, which presumably correct the import deficit after the resolution of the perturbation [15] (figure 2). ATFS-1 also induces glycolytic genes, which indicates that there is a concomitant transient shift in cellular ATP production from mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation to cytoplasmic glycolysis during mitochondrial stress [15]. Such a metabolic shift, while maintaining cellular energy supply, avoids overtaxation of mitochondrial energy harvesting in stress situations.

Figure 1. Scheme depicting the transcriptional regulation of the UPRmt.

Accumulating unfolded proteins, unassisted by chaperone Hsp60 in stressed mitochondria, are digested by the protease Clpp. The resulting peptides are transported through the double mitochondrial membrane into the cytosol. These peptides presumably stop mitochondrial import, which is also negatively affected by specific degradation of Tim17 component of the translocation pore by protease Yme1l1. As a result, C. elegans transcription factor ATFS-1, which in normal conditions is translocated to mitochondria and degraded by protease LonP, moves into the nucleus together with UBL-5 and DVE-1 to activate a reparative transcriptional program. In mammals, Jnk2 triggers c-Jun binding to AP1 sites, leading to the activation of Chop and Cebpβ transcription. Subsequently, Chop and Cebpβ dimers bind to CHOP sites flanked by MUREs and induce UPRmt target gene transcription. Proteins characterized in C. elegans are marked in green, fly and mammalian system proteins in red and proteins conserved in all the systems are noted in blue (mouse nomenclature is used).

Figure 2. The pleiotropic effects of UPRmt.

A scheme summarizing the principle UPRmt sensor/activator signals and the downstream interacting pathways, with their respective cellular effects. Proteins characterized in the fly and/or mammalian systems are marked in red and those studied in C. elegans in green.

How mitochondrial stress in mammals is sensed and triggers UPRmt, and whether it involves the possible generation of peptides similarly as in C. elegans, is still unknown. In mammalian cells transfected with OTC-Δ, the UPRmt transcriptional response was shown to involve JNK2 phosphorylation, which triggers c-Jun to bind and activate the CHOP and C/EBPβ promoters [20,40] (figure 1). c-Jun was shown to be also required for UPRmt induction in flies [41] and CHOP induction has been observed upon EndoG overexpression [21] or in complex IV deficient Surf−/− mice [42]. Consequently, UPRmt target gene expression is coordinated by a dimer of the transcription factors CHOP and C/EBPβ, which binds target promoters on a specific CHOP binding site flanked by two UPRmt response elements (MUREs) [43]. MUREs have been identified in the promoters of human mitochondrial PQC chaperones and proteases (HSP60, HSP10 and mtDnaJ, ClpP, YME1L1 and PMPCB), as well as in the enzymes NDUFB2, endonuclease G and thioredoxin 2 [43]. A recent transcriptomics and proteomics analysis revealed that UPRmt effector proteins Hsp60, Hsp10, mtHsp70, ClpP, Lonp1 and Ubl5 form a tight coexpression network in mice GRPs and human populations, suggestive of their transcriptional control [18]. However, the fact that stronger correlations were observed on protein than on transcript level, indicates also importance of posttranslational mechanisms in UPRmt regulation [18].

Evidence for conservation of UPRmt pathway in mammals

Although the UPRmt has been intensively investigated in yeast [16], worms [15,17,27,37-39,44], flies [22,41], and mammalian cells [17,20,26,28,29,45], it is not yet defined when and where UPRmt occurs in intact mammals.

We previously demonstrated that mitonuclear protein imbalance, as seen upon reduced expression of Mrps and/or inhibition of mitochondrial translation, induces a robust UPRmt in the BXD mouse strains, which translated in a significant lifespan extension [26]. As further proof of concept that similar mechanisms could activate UPRmt across species, we recently showed that subtle variations in the expression of orthologs of two prototypical UPRmt components—i.e. cco-1, a nuclear encoded component of ETC complex IV [27] and the protease spg-7 [17]—whose loss-of-function trigger worm UPRmt, also induce a UPRmt signature in unchallenged mice from the BXD GRPs [18]. These robust correlations on a population levels are remarkable as they indicate that UPRmt is a physiological pathway, which is not only activated by robust genetic or pharmacological perturbations, but has a role in subtle homeostatic processes [18], that can impact on lifespan [26]. The tight correlation and regulation of the UPRmt was furthermore also conserved in several different human tissues, supporting the cross-species nature of UPRmt [18].

In addition to these data coming from holistic genetic approaches, recently also single gene perturbations in mice have been linked with UPRmt. A UPRmt signature was for instance detected in muscles of mtDNA Deletor and Sco2KO/KI mice, models of inherited mitochondrial myopathies [34,35]. Phenotypic analysis of Surf1−/− mice, deficient in ETC complex IV, also revealed activation of the UPRmt markers Hsp60, ClpP, Lonp and Chop [42]. Furthermore, UPRmt can also be induced pharmacologically in mice [30]. Like in worms, treatment with PARP inhibitors triggers a robust UPRmt in mice as a consequence of a mitonuclear protein imbalance caused by the enhanced translation of the 13 mtDNA encoded ETC proteins [30]. These emerging data warrant further investigation of the eventual presence of UPRmt in other mice models and in human patient biopsies.

UPRmt-induced protective responses

Under stress, several lines of defense are activated by mitochondria. First, production and import of new mitochondrial proteins is temporarily blocked. Specific kinases, GCN-2 in the worm [44] and PKR in mammals [28], phosphorylate eIF2a, which leads to attenuation of global translation (figure 2). In C. elegans, reduction of mitochondrial import is important to initiate the UPRmt transcriptional response [15]. Furthermore, specific reduction in mitochondrial import occurs also in mammalian cells upon UPRmt, as the Yme1l1 protease selectively degrades the translocation pore component Tim17A [14]. The reduction of mitochondrial proteins and function during stress is consistent with the reallocation of ATP production to glycolysis in the cytoplasm [15].

In addition, several parallel protective responses are activated upon UPRmt. SIR-2.1 in worms and mammalian Sirt3 were shown to regulate UPRmt in part by deacetylating DAF-16 or its mammalian homolog Foxo3a, respectively, which then activates an antioxidant response [21,29] (figure 2). Another major oxidative stress response pathway, coordinated by Nrf2 (NFE2L2), was activated in complex IV deficient Surf1−/− mice [42]. Interestingly, the Nrf2 pathway is coordinated by c-Jun [46], which also regulates CHOP and C/EBPβ in the context of mammalian UPRmt, as discussed above. On a similar note, in C. elegans treated with antimycin or spg-7 RNAi to induce UPRmt, pathogen defense and drug detoxification are enhanced [24,25]. The activation of these protective pathways allows the worm to recognize and avoid pathogens, which target mitochondria, and can increase its resistance to a wider network of stressors. For instance, worms and mammalian cells with an active UPRmt are more resistant to ROS generator paraquat [14,29]. Additionally, worm gain-of-function mutants of ATFS-1 with constitutively activated UPRmt, are resistant to statin (inhibitors of HMG-CoA reductase) toxicity [47].

Recent findings suggest that mitochondrial remodeling, namely fission and fusion, as well selective removal of terminally defective mitochondria by mitophagy, take place under stress conditions. Both increased fusion [29] and fission [19,22,26] have been detected under UPRmt, which presumably depends on the type and strength of UPRmt inducer and requires further studies. Increased mitophagy has been observed in mammalian cells and flies overexpressing mutant forms of EndoG [21] or OTC-Δ [19,22,48], as well as upon RNAi inactivation of the ETC component ND75 [41]. In these systems mitophagy is potentially regulated by Foxo3a [21], AMPK [22] and secreted Insulin antagonizing peptide ImpL2, which non-autonomously repressed insulin signaling in distant tissues [41] (figure 2). Whether mitophagy is upregulated in UPRmt inducing conditions in worms, has not been directly investigated, but seems also likely, as autophagy genes are among the ATFS-1 targets [49]. Interestingly, mitophagy and UPRmt might share the same initial mitochondrial damage detection steps, as in worms, synthesis of ceramide, a sphingolipid which marks domains of mitochondrial dysfunction and induces mitophagy by anchoring autophagolysosomes to these domains [50], was required for UPRmt activation [24]. Mitophagy is induced by PINK1, that accumulates on the depolarized outer mitochondrial membrane, and then recruits the E3 ubiquitin ligase Parkin, targeting mitochondria to autophagosomes [51]. Mitophagy induction might be altered in UPRmt conditions, as upon OTC-Δ expression in cells, PINK1 and Parkin accumulate on stressed, but not depolarized mitochondria [48]. This might be regulated at the level of PINK1 degradation in basal conditions, in which mitochondrial PQC proteases, namely Lonp1, seem to be also involved [52].

Both mitochondrial dynamics and mitophagy pathways contribute to reconstitution of cellular homeostasis in stress conditions, by redistribution and removal of the irreversibly damaged elements of mitochondrial network. Inability to induce sufficient levels of mitophagy, under strong mitochondrial stress and activation of UPRmt, induces apoptosis and has negative systemic effects on whole organism physiology [21,22].

UPRmt systemic effects on aging

Disruption of almost any subunit of the ETC paradoxically extends lifespan in yeast, worms, flies and mice [53-55]. The lifespan extension is associated with typical phenotypes, such as delayed development, small size and reduced fertility. Interference with ETC has hormetic effects on longevity, demonstrated by RNAi dilution experiments: moderate knockdown extends lifespan, while too low and too strong knockdowns either do not have an effect or reduce lifespan, respectively [56]. Moreover, there are specific spatio-temporal restrictions, as selective interference with ETC only in neurons and intestine during larval stages increases worm longevity [27,31]. UPRmt is almost invariably present [57], follows the same spatio-temporal specifications [27], and is required for lifespan extension in worms with ETC problems [26,27,44,58]. In flies, disruption of the complex I component ND75 in the muscle by low-levels of RNAi, for a defined time period in the adult stage, activated UPRmt and increased lifespan [41]. In line with this, the reduced expression of Mrps5, a mitochondrial ribosomal protein, which regulates the translation of mtDNA encoded ETC genes, induces a mitonuclear imbalance resulting in UPRmt, which correlates with increased lifespan in the BXD mouse GRP [26]. This effect on lifespan in the BXD strains was all the more striking as it was not linked to loss of gene function, but just due to a subtle variation in Mrps5 expression levels. The positive effects of UPRmt on lifespan are also exemplified in worms [59] and flies [41] with forced overexpression of UPRmt effector chaperones.

Despite this rather convincing evidence linking UPRmt activation and longevity obtained in several independent laboratories and across multiple species (worm, fly, mice), not all UPRmt inductions may be beneficial [22,60]. This is not too surprising given the hormetic nature of UPRmt, with a clear dose effect relationship and with well-defined spatio-temporal frames. If the level of mitochondrial stress is too high, the protective effects of UPRmt may hence be insufficient to counteract the damage, making a beneficial adaptive response become maladaptive.

Conclusions and perspectives

First described ~20 years ago, the UPRmt is now emerging as an important regulator of mitochondrial health, interacting with other mitochondrial quality control systems, such as the oxidative stress response, mitochondrial biogenesis and mitophagy. Although some specific UPRmt regulators and pathways have been described in invertebrates, our knowledge of the exact molecular machinery of the UPRmt is still evolving and incomplete. Further studies defining the UPRmt sensors, signal transduction pathways and effectors, particularly in mammals are hence required. Also how the UPRmt intersects with other cellular signaling pathways, such as those controlled by sirtuins, AMPK or insulin, requires further investigation. The fact that a UPRmt signal is present in unchallenged mouse and human populations across multiple tissues [18] is an important step towards ascertaining its importance in mammals. It furthermore suggests that this pathway not only has a role in stress defense but also in homeostasis, where UPRmt could synchronize mitochondrial and nuclear genomes at the proteome level. We hope that better understanding of UPRmt may one day help translate the benefits of the UPRmt into therapies for rare inherited and common age-related related diseases with mitochondrial dysfunction.

Acknowledgements

We thank laboratory members Adrienne Mottis, Pedro M. Quiros and Laurent Mouchiroud for critical suggestions. JA is the Nestlé Chair in Energy Metabolism and his research is supported by the EPFL, the NIH (R01AG043930), and the SNSF (31003A-140780).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References and recommended reading

- 1.Dillin A, Gottschling DE, Nystrom T. The good and the bad of being connected: the integrons of aging. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2014;26:107–112. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2013.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Houtkooper RH, Williams RW, Auwerx J. Metabolic networks of longevity. Cell. 2010;142:9–14. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.06.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andreux PA, Houtkooper RH, Auwerx J. Pharmacological approaches to restore mitochondrial function. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2013;12:465–483. doi: 10.1038/nrd4023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nunnari J, Suomalainen A. Mitochondria: in sickness and in health. Cell. 2012;148:1145–1159. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.02.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jensen MB, Jasper H. Mitochondrial Proteostasis in the Control of Aging and Longevity. Cell Metab. 2014;20:214–225. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haynes CM, Ron D. The mitochondrial UPR - protecting organelle protein homeostasis. J Cell Sci. 2010;123:3849–3855. doi: 10.1242/jcs.075119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jovaisaite V, Mouchiroud L, Auwerx J. The mitochondrial unfolded protein response, a conserved stress response pathway with implications in health and disease. J Exp Biol. 2014;217:137–143. doi: 10.1242/jeb.090738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gray MW, Burger G, Lang BF. The origin and early evolution of mitochondria. Genome Biol. 2001;2:REVIEWS1018. doi: 10.1186/gb-2001-2-6-reviews1018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pagliarini DJ, Calvo SE, Chang B, Sheth SA, Vafai SB, Ong SE, Walford GA, Sugiana C, Boneh A, Chen WK, et al. A mitochondrial protein compendium elucidates complex I disease biology. Cell. 2008;134:112–123. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Neupert W, Herrmann JM. Translocation of proteins into mitochondria. Annu Rev Biochem. 2007;76:723–749. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.76.052705.163409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lane N. Mitonuclear match: optimizing fitness and fertility over generations drives ageing within generations. Bioessays. 2011;33:860–869. doi: 10.1002/bies.201100051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baker BM, Haynes CM. Mitochondrial protein quality control during biogenesis and aging. Trends Biochem Sci. 2011;36:254–261. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2011.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tatsuta T, Langer T. Quality control of mitochondria: protection against neurodegeneration and ageing. EMBO J. 2008;27:306–314. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14••.Rainbolt TK, Atanassova N, Genereux JC, Wiseman RL. Stress-regulated translational attenuation adapts mitochondrial protein import through Tim17A degradation. Cell Metab. 2013;18:908–919. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2013.11.006. [This study shows that mitochondrial import during stress conditions is perturbed by selective degradation of translocase subunit Tim17A, which promotes mitochondrial proteostasis.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15••.Nargund AM, Pellegrino MW, Fiorese CJ, Baker BM, Haynes CM. Mitochondrial import efficiency of ATFS-1 regulates mitochondrial UPR activation. Science. 2012;337:587–590. doi: 10.1126/science.1223560. [This work describes the molecular mechanism of initiation of UPRmt transcriptional program by ATFS-1, which is dependent on the mitochondrial import efficiency.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schleit J, Johnson SC, Bennett CF, Simko M, Trongtham N, Castanza A, Hsieh EJ, Moller RM, Wasko BM, Delaney JR, et al. Molecular mechanisms underlying genotype-dependent responses to dietary restriction. Aging Cell. 2013;12:1050–1061. doi: 10.1111/acel.12130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yoneda T, Benedetti C, Urano F, Clark SG, Harding HP, Ron D. Compartment-specific perturbation of protein handling activates genes encoding mitochondrial chaperones. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:4055–4066. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18••.Wu Y, Williams Evan G, Dubuis S, Mottis A, Jovaisaite V, Houten Sander M, Argmann Carmen A, Faridi P, Wolski W, Kutalik Z, et al. Multilayered Genetic and Omics Dissection of Mitochondrial Activity in a Mouse Reference Population. Cell. 2014;158:1415–1430. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.07.039. [Demonstration of the conservation of the UPRmt effector coexpression network in mice and human populations and of a role of the UPRmt in homeostasis, beyond its function in stress response.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Burbulla LF, Fitzgerald JC, Stegen K, Westermeier J, Thost AK, Kato H, Mokranjac D, Sauerwald J, Martins LM, Woitalla D, et al. Mitochondrial proteolytic stress induced by loss of mortalin function is rescued by Parkin and PINK1. Cell Death Dis. 2014;5:e1180. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2014.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhao Q, Wang J, Levichkin IV, Stasinopoulos S, Ryan MT, Hoogenraad NJ. A mitochondrial specific stress response in mammalian cells. EMBO J. 2002;21:4411–4419. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Papa L, Germain D. SirT3 regulates the mitochondrial unfolded protein response. Mol Cell Biol. 2014;34:699–710. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01337-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pimenta de Castro I, Costa AC, Lam D, Tufi R, Fedele V, Moisoi N, Dinsdale D, Deas E, Loh SH, Martins LM. Genetic analysis of mitochondrial protein misfolding in Drosophila melanogaster. Cell Death Differ. 2012;19:1308–1316. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2012.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23••.Runkel ED, Liu S, Baumeister R, Schulze E. Surveillance-Activated Defenses Block the ROS-Induced Mitochondrial Unfolded Protein Response. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:e1003346. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003346. [Demonstration of the conservation of the UPRmt effector coexpression network in mice and human populations and of a role of the UPRmt in homeostasis, beyond its function in stress response.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24••.Liu Y, Samuel BS, Breen PC, Ruvkun G. Caenorhabditis elegans pathways that surveil and defend mitochondria. Nature. 2014;508:406–410. doi: 10.1038/nature13204. [This paper establishes that UPRmt is an important mitochondrial defense against drugs and pathogens, for which ceramide and mevalonate synthesis pathways are required.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25••.Pellegrino MW, Nargund AM, Kirienko NV, Gillis R, Fiorese CJ, Haynes CM. Mitochondrial UPR-regulated innate immunity provides resistance to pathogen infection. Nature. 2014 doi: 10.1038/nature13818. In press. [This work further describes the role of UPRmt in innate immunity.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26••.Houtkooper RH, Mouchiroud L, Ryu D, Moullan N, Katsyuba E, Knott G, Williams RW, Auwerx J. Mitonuclear protein imbalance as a conserved longevity mechanism. Nature. 2013;497:451–457. doi: 10.1038/nature12188. [This study defines mitonuclear imbalance as the cause for UPRmt induction by multiple genetic and pharmacological perturbations. It also shows that mitochondrial ribosomal proteins are conserved regulators of UPRmt and longevity in mice genetic reference population and in worms.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27••.Durieux J, Wolff S, Dillin A. The cell-non-autonomous nature of electron transport chain-mediated longevity. Cell. 2011;144:79–91. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.12.016. [Landmark study that describes the role of UPRmt in ETC-mediated longevity, its cell non-autonomous aspects and demonstrates the involvement of so-called “mitokines”.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rath E, Berger E, Messlik A, Nunes T, Liu B, Kim SC, Hoogenraad N, Sans M, Sartor RB, Haller D. Induction of dsRNA-activated protein kinase links mitochondrial unfolded protein response to the pathogenesis of intestinal inflammation. Gut. 2012;61:1269–1278. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-300767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29••.Mouchiroud L, Houtkooper RH, Moullan N, Katsyuba E, Ryu D, Canto C, Mottis A, Jo YS, Viswanathan M, Schoonjans K, et al. The NAD(+)/Sirtuin Pathway Modulates Longevity through Activation of Mitochondrial UPR and FOXO Signaling. Cell. 2013;154:430–441. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.06.016. [This report reveals that Sirtuin 1 activation by increased NAD+ levels induces mitonuclear imbalance, UPRmt and induction of antioxidant defense by FOXO transcription factor daf-16.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30•.Pirinen E, Canto C, Jo YS, Morato L, Zhang H, Menzies KJ, Williams EG, Mouchiroud L, Moullan N, Hagberg C, et al. Pharmacological Inhibition of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerases improves fitness and mitochondrial function in skeletal muscle. Cell Metab. 2014;19:1034–1041. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.04.002. [This study shows that PARP inhibitors increase NAD+ levels, mitochondrial protein translation, UPRmt and have a beneficial impact on muscle function in mice.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dillin A, Hsu AL, Arantes-Oliveira N, Lehrer-Graiwer J, Hsin H, Fraser AG, Kamath RS, Ahringer J, Kenyon C. Rates of behavior and aging specified by mitochondrial function during development. Science. 2002;298:2398–2401. doi: 10.1126/science.1077780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tsang WY, Lemire BD. Mitochondrial genome content is regulated during nematode development. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;291:8–16. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2002.6394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Houtkooper RH, Pirinen E, Auwerx J. Sirtuins as regulators of metabolism and healthspan. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2012;13:225–238. doi: 10.1038/nrm3293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Khan NA, Auranen M, Paetau I, Pirinen E, Euro L, Forsstrom S, Pasila L, Velagapudi V, Carroll CJ, Auwerx J, et al. Effective treatment of mitochondrial myopathy by nicotinamide riboside, a vitamin B3. EMBO Mol Med. 2014;6:721–731. doi: 10.1002/emmm.201403943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cerutti R, Pirinen E, Lamperti C, Marchet S, Sauve AA, Li W, Leoni V, Schon EA, Dantzer F, Auwerx J, et al. NAD(+)-dependent activation of Sirt1 corrects the phenotype in a mouse model of mitochondrial disease. Cell Metab. 2014;19:1042–1049. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ryu D, Jo YS, Lo Sasso G, Stein S, Zhang H, Perino A, Lee JU, Zeviani M, Romand R, Hottiger MO, et al. A SIRT7-Dependent Acetylation Switch of GABPbeta1 Controls Mitochondrial Function. Cell Metab. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Haynes CM, Petrova K, Benedetti C, Yang Y, Ron D. ClpP mediates activation of a mitochondrial unfolded protein response in C. elegans. Dev Cell. 2007;13:467–480. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Haynes CM, Yang Y, Blais SP, Neubert TA, Ron D. The matrix peptide exporter HAF-1 signals a mitochondrial UPR by activating the transcription factor ZC376.7 in C. elegans. Mol Cell. 2010;37:529–540. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Benedetti C, Haynes CM, Yang Y, Harding HP, Ron D. Ubiquitin-like protein 5 positively regulates chaperone gene expression in the mitochondrial unfolded protein response. Genetics. 2006;174:229–239. doi: 10.1534/genetics.106.061580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Horibe T, Hoogenraad NJ. The chop gene contains an element for the positive regulation of the mitochondrial unfolded protein response. PLoS One. 2007;2:e835. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41••.Owusu-Ansah E, Song W, Perrimon N. Muscle mitohormesis promotes longevity via systemic repression of insulin signaling. Cell. 2013;155:699–712. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.09.021. [This work demonstrates that mild interference with the ETC in fly muscle extends lifespan through induction of UPRmt and the insulin antagonizing peptide ImpL2 (a mitokine), which non-autonomously represses insulin signaling and increases mitophagy. Furthermore, it shows that forced expression of UPRmt genes increases lifespan.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pulliam DA, Deepa SS, Liu Y, Hill S, Lin AL, Bhattacharya A, Shi Y, Sloane L, Viscomi C, Zeviani M, et al. Complex IV-deficient Surf1−/− mice initiate mitochondrial stress responses. Biochem J. 2014;462:359–371. doi: 10.1042/BJ20140291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Aldridge JE, Horibe T, Hoogenraad NJ. Discovery of genes activated by the mitochondrial unfolded protein response (mtUPR) and cognate promoter elements. PLoS One. 2007;2:e874. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44••.Baker BM, Nargund AM, Sun T, Haynes CM. Protective coupling of mitochondrial function and protein synthesis via the eIF2alpha kinase GCN-2. PLoS Genet. 2012;8:e1002760. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002760. [This work highlights GCN-2 mediated inhibition of translation in the cytoplasm in mitochondrial stress conditions.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Martinus RD, Garth GP, Webster TL, Cartwright P, Naylor DJ, Hoj PB, Hoogenraad NJ. Selective induction of mitochondrial chaperones in response to loss of the mitochondrial genome. Eur J Biochem. 1996;240:98–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.0098h.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jeyapaul J, Jaiswal AK. Nrf2 and c-Jun regulation of antioxidant response element (ARE)-mediated expression and induction of gamma-glutamylcysteine synthetase heavy subunit gene. Biochem Pharmacol. 2000;59:1433–1439. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(00)00256-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rauthan M, Ranji P, Aguilera Pradenas N, Pitot C, Pilon M. The mitochondrial unfolded protein response activator ATFS-1 protects cells from inhibition of the mevalonate pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:5981–5986. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1218778110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jin SM, Youle RJ. The accumulation of misfolded proteins in the mitochondrial matrix is sensed by PINK1 to induce PARK2/Parkin-mediated mitophagy of polarized mitochondria. Autophagy. 2013;9:1750–1757. doi: 10.4161/auto.26122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Guo B, Huang X, Zhang P, Qi L, Liang Q, Zhang X, Huang J, Fang B, Hou W, Han J, et al. Genome-wide screen identifies signaling pathways that regulate autophagy during Caenorhabditis elegans development. EMBO Rep. 2014;15:705–713. doi: 10.1002/embr.201338310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sentelle RD, Senkal CE, Jiang W, Ponnusamy S, Gencer S, Selvam SP, Ramshesh VK, Peterson YK, Lemasters JJ, Szulc ZM, et al. Ceramide targets autophagosomes to mitochondria and induces lethal mitophagy. Nat Chem Biol. 2012;8:831–838. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kroemer G, Marino G, Levine B. Autophagy and the integrated stress response. Mol Cell. 2010;40:280–293. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.09.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Thomas RE, Andrews LA, Burman JL, Lin WY, Pallanck LJ. PINK1-Parkin pathway activity is regulated by degradation of PINK1 in the mitochondrial matrix. PLoS Genet. 2014;10:e1004279. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wong A, Boutis P, Hekimi S. Mutations in the clk-1 gene of Caenorhabditis elegans affect developmental and behavioral timing. Genetics. 1995;139:1247–1259. doi: 10.1093/genetics/139.3.1247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Munkacsy E, Rea SL. The paradox of mitochondrial dysfunction and extended longevity. Exp Gerontol. 2014;56:221–233. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2014.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pulliam DA, Bhattacharya A, Van Remmen H. Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Aging and Longevity: A Causal or Protective Role? Antioxid Redox Signal. 2012 doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.4950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rea SL, Ventura N, Johnson TE. Relationship between mitochondrial electron transport chain dysfunction, development, and life extension in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS Biol. 2007;5:e259. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ventura N, Rea SL. Caenorhabditis elegans mitochondrial mutants as an investigative tool to study human neurodegenerative diseases associated with mitochondrial dysfunction. Biotechnol J. 2007;2:584–595. doi: 10.1002/biot.200600248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schieber M, Chandel NS. TOR signaling couples oxygen sensing to lifespan in C. elegans. Cell Reports. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.08.075. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yokoyama K, Fukumoto K, Murakami T, Harada S, Hosono R, Wadhwa R, Mitsui Y, Ohkuma S. Extended longevity of Caenorhabditis elegans by knocking in extra copies of hsp70F, a homolog of mot-2 (mortalin)/mthsp70/Grp75. FEBS Lett. 2002;516:53–57. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)02470-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bennett CF, Vander Wende H, Simko M, Klum S, Barfield S, Choi H, Pineda VV, Kaeberlein M. Activation of the mitochondrial unfolded protein response does not predict longevity in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nat Commun. 2014;5:3483. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]