Abstract

To decouple the extracellular oxidative toxicity of catechol adhesive moiety from its intracellular non-oxidative toxicity, dopamine was chemically bound to a non-degradable polyacrylamide hydrogel through photo-initiated polymerization of dopamine methacrylamide (DMA) with acrylamide monomers. Network-bound dopamine released cytotoxic levels of H2O2 when its catechol side chain oxidized to quinone. Introduction of catalase at a concentration as low as 7.5 U/mL counteracted the cytotoxic effect of H2O2 and enhanced the viability and proliferation rate of fibroblasts. These results indicated that H2O2 generation is one of the main contributors to the cytotoxicity of dopamine in culture. Additionally, catalase is a potentially useful supplement to suppress the elevated oxidative stress found in typical culture conditions and can more accurately evaluate the biocompatibility of mussel-mimetic biomaterials. The release of H2O2 also induced a higher foreign body reaction to catechol-modified hydrogel when it was implanted subcutaneously in rat. Given that H2O2 has a multitude of biological effects, both beneficiary and deleterious, regulation of H2O2 production from catechol-containing biomaterials is necessary to optimize the performance of these materials for a desired application.

Keywords: dopamine, mussel adhesive protein, catalase, hydrogel, cytotoxicity, biocompatibility, subcutaneous implantation

1. Introduction

Marine mussels secrete remarkable underwater adhesives that allow these animals to anchor to surfaces in turbulent intertidal zones [1]. These proteins contain a large abundance of a catecholic amino acid, 3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine (DOPA), which functions both as a crosslinking precursor and an adhesive moiety [2]. The catechol side chain of DOPA is a unique and versatile adhesive molecule capable of binding to both organic and inorganic surfaces through either covalent attachment or strong reversible bonds. Inert, synthetic polymers modified with DOPA and other catechol derivatives (i.e., dopamine) have demonstrated strong, water-resistant adhesive properties to various biological, metallic and polymeric substrates [3–5]. The simplicity and versatility of catechol chemistry has been exploited in designing functional biomaterials for a wide range of applications including tissue adhesive and sealant [6–8], antimicrobial polymer [9], drug carrier [10], surface coating [11, 12], and soft actuator [13, 14].

To further advance this biomimetic technology toward clinical applications, biocompatibility of these biomimic materials need to be carefully evaluated. Both dopamine and DOPA are naturally found in our body [15]. However, autoxidation of these catechol species generates a considerable amount of reactive oxygen species (ROS) [16]. Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) is a major composition of ROS that has been detected in cell culture media containing DOPA or dopamine [17]. Routine cultures are exposed to elevated oxygen pressure (150 mmHg compared to 1–10 mmHg in vivo) [18, 19] and are deficient of antioxidants (i.e., ascorbic acid, tocopherol, catalase) that counteract elevated oxidative stress [20], both of which promote ROS generation from these catechol species [17]. Incubation of polyphenol extracts in an nitrogen-rich atmosphere inhibited H2O2 generation, which indicated that the importance of oxygen concentration in the production of H2O2 from catechol moieties [21]. Similarly, polyphenols that are well-known for their antioxidant properties have also been shown to exhibit pro-oxidant activities under certain culture conditions [20].

ROS has been found to have both beneficiary and deleterious effects [22]. Inflammatory cells produce ROS during the early stages of wound healing process [23] and a suppressed ROS production increases the chance for infection [24] and delayed wound healing [25, 26]. Exogenously supplied H2O2 at a relatively low concentration promoted skin [25] and corneal [27] healing as well as axon regeneration [28]. Similarly, biomaterials supplemented with glucose oxidase, which increased the production of H2O2 at the wound site, also promoted wound healing [29]. On the other hand, excessive ROS concentrations, especially H2O2, can destroy healthy tissue, resulting in the formation of chronic wounds and promote tumor initiation [22]. Antioxidant nanoparticles (e.g. cerium oxide) have been found to accelerate topical wound healing in mice skin [30] and antioxidant (superoxide dismutase, SOD) incorporation reduced the foreign body response and increased the biocompatibility of injectable hydrogels [31]. Therefore, ROS concentration needs to be rigorously regulated depending on the application.

Here, we use a model system to correlate the production of H2O2 from biomimetic catechol with the biocompatibility of the adhesive molecule both in culture and in vivo. Dopamine methacylamide (DMA) was copolymerized into a non-degradable polyacrylamide (PAAm) hydrogel network. Dopamine consists of a catechol side chain that mimics the reactivity of bioadhesive moiety, DOPA. The adhesive is bound to the PAAm network so that the generation and release of the oxidation byproducts can be captured in the cell culture extract. This model system is used to distinguish the cytotoxicity effect of the oxidation byproducts (i.e., exrtracellular effect of ROS) from intracellular toxicity effect as a result of cellular uptake of the catechol [17]. Production of H2O2 from DMA containing hydrogel and its effect on cell viability and proliferation was determined. Catalase is a common enzyme found in many living organisms that are exposed to air and can catalyze H2O2 into water and oxygen [32]. Catalase has been found to effectively counteract the cytotoxicity induced by H2O2 in culture [17]. The ability for catalase to counteract the cytotoxicity effect of H2O2 in culture was also examined. Finally, the biocompatibility of DMA containing hydrogel was evaluated in a rat subcutaneous model.

2. Materials and methods

2.1 Materials

Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM; with 4.5 g/L glucose and glutamine, without sodium pyruvate), and trypsin-EDTA (0.05% Trypsin/0.53 mM EDTA in Hank’s balanced salt solution) were obtained from Corning Cellgro (Manassas, VA). N,N′-methylene-bisacrylamide (MBAA) and 2,2-dimethoxy-2-phenylacetophenone (DMPA), and dopamine hydrochloride were purchased from Acros Organics (Geel, Belgium). Acrylamide (AAm), ethanol, phosphate buffered saline (PBS, BioPerformance certified, pH7.4), bovine liver catalase, and PolyFreeze were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and 12 M hydrochloric (HCl) acid were purchased from Fisher Scientific (Pittsburg, PA). Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2, 30% stock solution) was from Avantor (Center Valley, PA). Pierce Quantitative Peroxide Assay Kit with sorbitol, fetal bovine serum (FBS) and Penicillin-Streptomycin (10 units/mL) were purchased from Thermo Scientific (Rockford, IL). 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide 98% (MTT) was from Alfa Aesar (Ward Hill, MA). Mouse mAb (clone MoBU-1) Alexa Fluor® 488 conjugate antibody and 4′, 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) was obtained from Invitrogen (Grand Island, NY). Anti-S100A4 antibody (ab27957), goat anti-rabbit IgG H&L (Alexa Fluor 488; ab150077), anti-CD68 antibody (ab125212), and goat anti-rabbit IgG H&L (Alexa Fluor 647; ab150079) were purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, MA). DMA was synthesized as previously described [33].

2.2 Hydrogel preparation

Hydrogels were prepared by photo-initiated polymerization following published protocol [34]. Briefly, precursor solutions containing 1M AAm, 0–3 wt% DMA, 2 mol% MBAA, and 0.1 mol% DMPA were poured into a 2-mm thick mold and photo-irradiated for 15 min using a UV crosslinking chamber (XL-1000, Spectronics Corporation, Westbury, NY) located in a N2-filled glove box. Hydrogel samples were cut into disc-shape (diameter = 10 mm) and dialyzed in deionized water acidified to pH 3.5 using concentrated HCl for at least 3 days while changing the dialysate twice daily to remove unreacted monomers. Due to the differences in the swelling behaviour for hydrogels with different concentrations of DMA (Figure S1 and Table S1), cutting the hydrogels to a uniform size before equilibrating them in an aqueous medium ensured accurate estimation of DMA concentration in each sample.

2.3 Preparation of hydrogel extract

Hydrogels were sterilized by submersing the samples in 70% (v/v) ethanol for 45 min and washed three times with 20 mL PBS for 90 min [35, 36]. The sterilized hydrogels were transferred into a 24-well plate and incubated with 1 mL of L929 cell culture medium, prepared with DMEM (addition of 10% (v/v) FBS and 0.5% (v/v) Penicillin-Streptomycin) and incubated for 1–48 h (37°C, 5% CO2 and 95% air). The concentrations of hydrogel-bound DMA in the extraction media were 7, 14, and 21 mM for hydrogels containing 1, 2, and 3 wt% DMA, respectively.

2.4 Measurement of H2O2 generation

H2O2 measurement was carried out using the ferrous (Fe) ion oxidation xylenol orange (FOX) assay by Quantitative Peroxide Assay Kit [17]. 20 μL of the hydrogel extract was mixed with 200 μL of FOX reagent and incubated at room temperature for 20 minutes and examined using a microplate reader (SynergyTM HT, BioTek) at 595 nm. To evaluate the effect of catalase activity on H2O2 production, bovine liver catalase (7.8–2000 U/mL) was added to the cell culture medium prior to extraction. For comparison purposes, DMA monomer and dopamine were dissolved in DMSO (84 mM) and diluted to 14 mM (equivalent to hydrogel containing 2 wt% DMA) using cell culture medium, and H2O2 generation from these solutions were determined. The H2O2 standard curve was prepared by preparing a stock solution (2000 μM of H2O2) from 30% H2O2 solution and serially diluting it to a concentration of 7.8–2000 μM.

2.5 Cell viability assessment

Cell viability was measured using quantitative MTT cytotoxicity assay in line with the guideline from ISO 10993–5 [37]. L929 mouse fibroblasts were suspended in cell culture medium and seeded into 96-well microculture plates with a density of 1×104 cells/100 μL/well and incubated for 24 h at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 humidified incubator to obtain a monolayer of cells. Cell medium was replaced with hydrogel extracts or cell culture medium containing various controls (i.e., H2O2, catalase, DMA monomer, or dopamine) and further incubated for an additional 24 h. The sample solution was removed and the cells were incubated with 50 μL of 1 mg/mL of MTT in PBS for 2 h. Finally, the PBS solution was replaced with 100 μL of DMSO to dissolve formazan, and the absorbance of the DMSO solution was detected at 570 nm (reference 650 nm). The relative cell viability was calculated as the ratio between the mean absorbance value of the sample and that of cells cultured in the medium. Samples with relative cell viability less than 70% was deemed to be cytotoxic [37]. For each sample, 3 independent cultures were prepared and cytotoxicity test was repeated 3 times for each culture.

2.6 Primary cell proliferation assessment

Cell proliferation activity of rat dermal fibroblasts were obtained by BrdU assay [38]. Rat dermal fibroblasts were isolated from rat subcutaneous tissue and identified by Anti-S100A4 antibody and goat anti-rabbit IgG H&L (Alexa Fluor® 488) (Figure S2) [39]. Rat dermal fibroblasts (6000 cells/cm2) were seeded in a 4-well chamber slide in 1 mL of cell culture medium for 4 h to allow cells to adhere. The cell culture medium was replaced by the hydrogel extract (with or without 100 U/mL of catalase), and further incubated for 12 h. 1 mL of Brdu (100 μM in cell culture medium) was then added to replace the hydrogel extract and incubated for another 24 h. After which, the chamber slide was stained with Brdu mouse mAb (clone MoBU-1) Alexa Fluor® 488 conjugate antibody following published protocols [38]. DAPI was used to locate the cells via nonspecific cell nuclei staining. Proliferation activity was defined as the percentage of Brdu positive cells in relation to the total number of cells stained by DAPI.

2.7 Subcutaneous implantation

12 to 16 weeks old, healthy, weight matched Sprague Dawley rats were provided by the Michigan Technological University (MTU) animal facility. Subcutaneous implantation was performed following protocols approved by MTU Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Hydrogels containing either 0 or 2 wt% DMA were randomly and bilaterally implanted into 4 subcutaneous pouches along the dorsal midline of the animal. Animals were sacrificed after 1 week or 4 weeks of implantation and the implants along with the surrounding tissues were collected, embedded in PolyFreeze, flash frozen in liquid nitrogen, cryosectioned into 10 μm thick sections, and stained with Masson’s trichrome kit. After 1 week, there was a cellular layer near the tissue-hydrogel interface composed mainly of macrophages and fibroblasts which is defined as the MF layer [40]. Cell density was calculated by counting cell nuclei (black in Masson’s Trichrome staining) in the MF layer in three 50 μm × 100 μm area on each slides [41]. Collagen density (blue in Masson’s Trichrome staining) was quantified in three 50 μm × 100 μm fields adjacent to the MF layer using a previously developed MATLAB (MathWorks, Natick, MA) program [42]. 4-week samples were quantified by measuring the fibrous capsule thickness, as well as cell and collagen density located in the fibrous capsule [41]. To identify the cell types surrounding the implanted hydrogels, both 1- and 4-week sections were further stained by immunofluorescent staining markers for rat fibroblasts (green, Anti-S100A4 antibody and goat antirabbit IgG H&L (Alexa Fluor® 488)) and macrophages (red, anti-CD68 antibody and goat antirabbit IgG H&L (Alexa Fluor ® 647)) [36]. All histological imaging analyses were performed on fluorescent microscope (Olympus BX51, Melville, NY). Both capsule thickness and MF layer cell numbers were quantified by ImageJ.

2.8 Statistical analysis

One way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey-Kramer HSD analysis and student t-test was performed for comparing means of multiple and two groups, respectively. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1 H2O2 generation from DMA-containing hydrogel

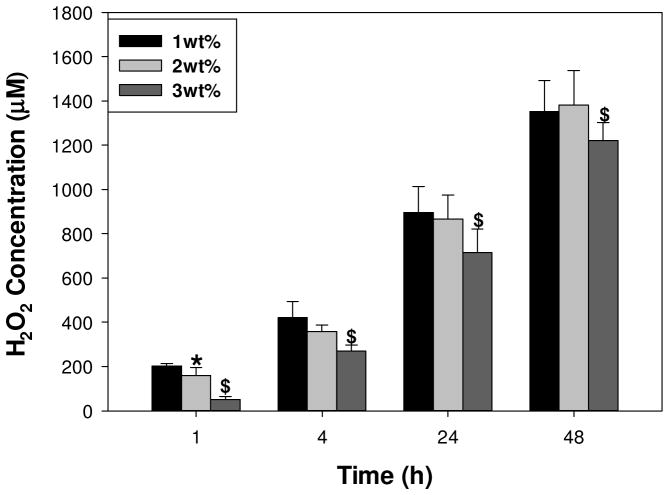

50.2 – 202 μM of H2O2 was detected within 1 h of incubation for 1–3 wt% DMA hydrogels and the H2O2 concentration increased with incubation time (Figure 1). Curiously, H2O2 concentrations did not increase proportionally with DMA content in the hydrogel, but decreased. This is contrary to H2O2 generated from equivalent concentrations of 7–21 mM DMA monomer in solution, where the H2O2 concentration increased with increasing DMA concentration (Figure S3). Additionally, DMA monomer and dopamine generated significantly higher concentrations of H2O2 than hydrogel with equivalent catechol concentration (14 mM) in the cell culture medium (Figure S4). For example, hydrogels containing 2 wt% DMA incubated in 1 mL of cell culture medium corresponds to 14 mM of DMA and dopamine. At the 48-h time point, H2O2 content in the hydrogel extract (1380 ± 155 μM) was 3 and 6 times lower than those of the DMA monomer (4710 ± 356 μM) and dopamine (7290 ± 1020 μM), respectively. The color of DMA monomer solutions and DMA containing hydrogel turned dark red with time, indicating the oxidation of colorless catechol moiety into its quinone chromophore. On the other hand, the solution containing dopamine turned black within a couple of hours of incubation, indicating that it has undergone autoxidation and polymerization to form polydopamine resembling melanin formation [16]. DMA lacks a free amine group necessary to participate in autoxidation mediated polymerization, indicating that excess H2O2 production likely formed during the polymerization of dopamine. There were no detectable H2O2 generated from DMA free hydrogel or cell culture medium (data not shown). Hydrogels containing 2 wt% DMA were used for subsequent cytotoxicity, cell proliferation and subcutaneous implantation studies.

Figure 1.

H2O2 generated from DMA-containing hydrogels with different DMA concentration. * significantly different from 1 wt% DMA hydrogel; $ significantly different from both 1 and 2 wt% DMA hydrogel. There was no detectable H2O2 generated from 0 wt% DMA hydrogel (data not shown).

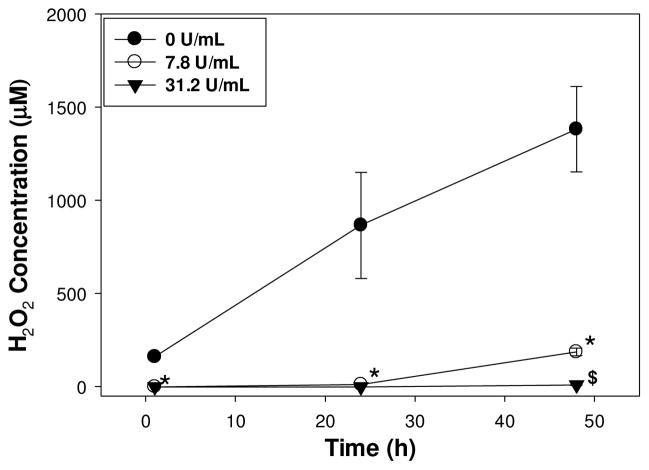

When catalase was introduced into the hydrogel extract, the detected H2O2 concentrations was drastically reduced (Figure 2). For extracts containing a catalase concentration of 7.8 U/mL, H2O2 concentration was negligible (0 μM) at the 1 and 24 h time points but increased to 186 ± 20.7 μM after 48 h. This lower catalase concentration likely was unable to completely reduce the elevated H2O2 concentration generated over 48 h. H2O2 was not detected for extracts with catalase concentrations of 31.2 U/mL and higher (data not shown) at all the time points tested.

Figure 2.

H2O2 concentration generated from 2 wt% DMA hydrogel in extracts containing 0–31.2 U/mL of catalase as a function of time. * significantly different from 0 U/mL of catalase; $ significantly different from both 0 and 7.8 U/mL of catalase.

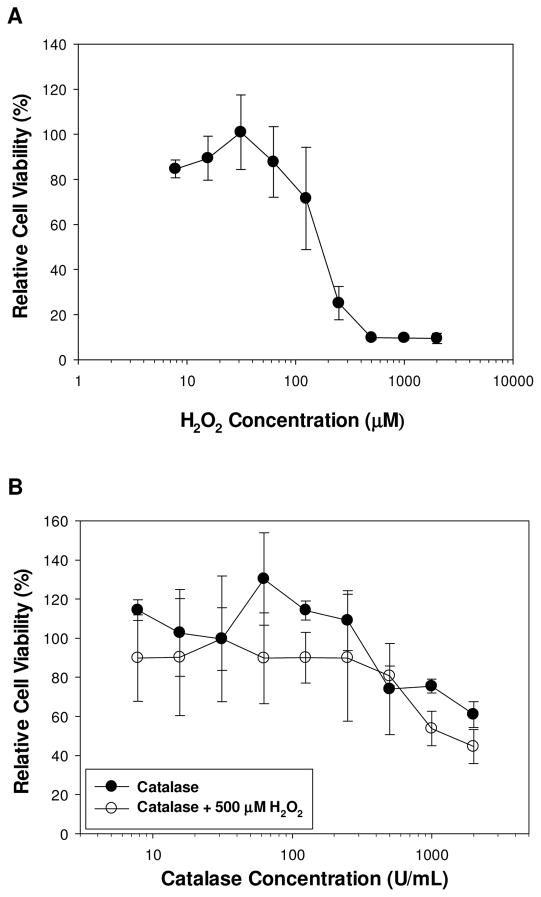

3.2 Effect of H2O2 and catalase on L929 fibroblast viability

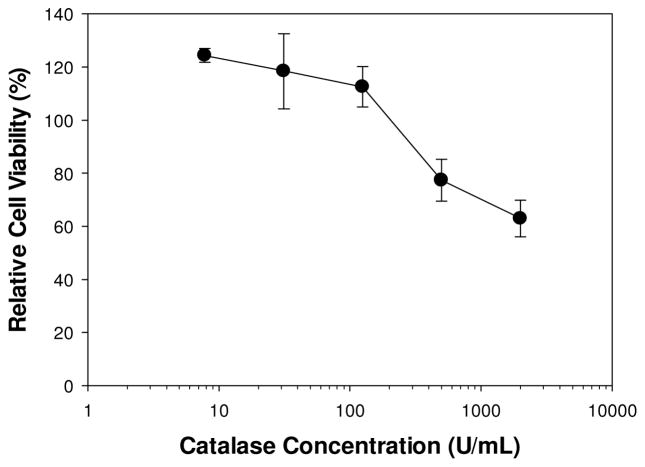

L929 fibroblasts were incubated in cell culture medium containing 7.8–2000 μM of H2O2. H2O2 concentrations greater than 62.5 μM resulted in cytotoxic response, while lower levels of H2O2 are relatively non-cytotoxic with cell viability greater than 85% (Figure 3A). This result indicates that 2 wt% DMA-containing hydrogel generated cytotoxic level of H2O2 (158.9 ± 7.4 μM) within 1 h of incubation (Figure 2). L929 cells were also exposed to an increasing concentration of catalase (7.8–2000 U/mL) (Figure 3B). Low levels of catalase did not affect cell viability and cellular activity even increased with the presence of catalase, suggesting the enzyme had a proliferative effect on fibroblast. However, cell culture medium with a catalase concentration higher than 500 U/mL demonstrated reduced cell viability, likely due to the complete removal of H2O2 as micromolar concentrations of H2O2 is necessary for intra- and intercellular signalling [43]. When catalase was added to a solution containing 500 μM of H2O2, the cytotoxic effect of H2O2 was completely eradicated. Addition of only 7.8 U/mL of catalase increased cell viability from 9.8 ± 0.8% to 85 ± 4.0% (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

L929 fibroblasts cell viability as a function of H2O2 concentration in the cell culture medium (A). L929 fibroblasts cell viability as a function of catalase concentration with or without 500 μM of H2O2 (B). Cell viability is 9.8 ± 0.8% for 500 μM of H2O2 without catalase.

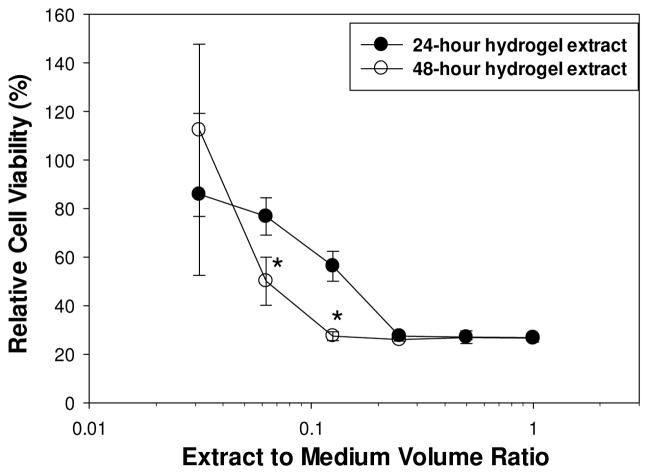

3.4 Effect of hydrogel extract on L929 fibroblast viability

After 24 and 48 h of incubation, the undiluted extracts from 2 wt% DMA hydrogels were both toxic to L929 fibroblast, with cell viability of only 26% (Figure 4). Cell viability increased when extracts were serially diluted with cell culture medium. At a 1:8 and 1:16 dilutions, cell viability for the 24 h extracts was significantly higher when compared to that of 48 h extracts, likely due to a reduced H2O2 concentration in extracts with a shorter incubation time. The cytotoxic effect of undiluted hydrogel extracts was eliminated with the addition of catalase (Figure 5). Cell viability was greater than 100% with the introduction of a catalase concentration as little as 7.8 U/mL. Similar to Figure 3B, catalase concentration greater than 500 U/mL reduced cell viability. Extracts from DMA-free PAAm hydrogels did not generate H2O2 and were non-cytotoxic (relative cell viability = 108 ± 8.4%).

Figure 4.

Relative cell viability for L929 fibroblast exposed to serially diluted extracts from hydrogel containing 2 wt% DMA after 24 and 48 h of incubation. * significantly different from the 24 h data.

Figure 5.

Relative cell viability of L929 fibroblast exposed to 2 wt% DMA hydrogel extract (24 h incubation) containing 7.8–2000 U/mL of catalase. Cell viability of extract without catalase was 26.7 ± 0.52%.

The cytotoxicity response of hydrogel extract was compared with those of DMA and dopamine solutions (Figure S5). Relative cell viability of both DMA solution and the extract from 2 wt% DMA hydrogel increased with serial dilution. The hydrogel extract required only 1:16 dilution to become non-cytotoxic, whereas the DMA solution requires a significant higher dilution (1:128) to improve cell viability. This result is in agreement with the lower measured H2O2 level in the hydrogel extracts as compared to that of DMA monomer (Figure S4). On the contrary, the undiluted dopamine solution was initially non-cytotoxic and demonstrated significantly higher cell viability when compared to those of DMA monomer and the hydrogel extract (Figure S5). However, when the dopamine solution was serial diluted with cell culture medium, cell viability decreased and reached a minimum at a ratio of 1:32 dilution. Further diluting the dopamine solution resulted in increased cell viability. Polydopamine is a known antioxidant [44] and its presence likely have a protective effect even though it generated the highest H2O2 amongst the samples tested. Additionally, both DMA and dopamine solutions were brought into direct contact with fibroblast and unlike the hydrogel extracts, the extracellular (i.e., generation of H2O2) and intracellular (i.e., cellular uptake) effects of these soluble catechol species could not be separated.

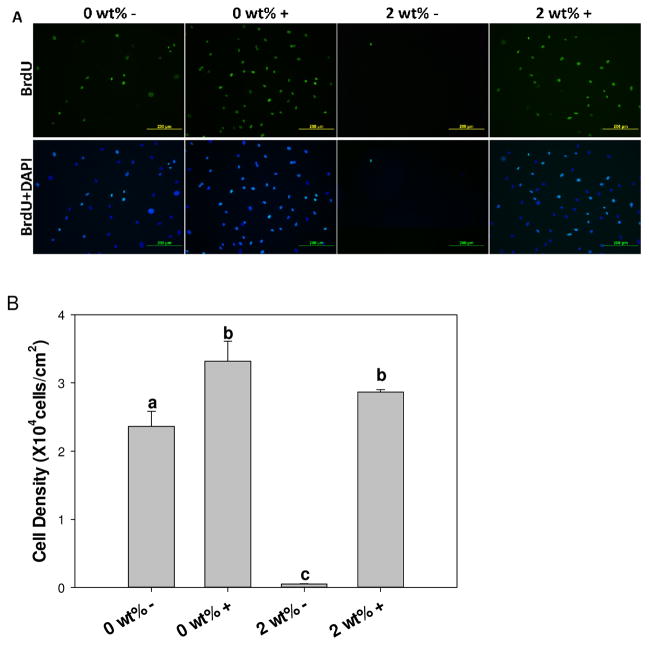

3.5 Effect of hydrogel extract on the proliferation of primary fibroblast

BrdU assay was performed to determine the effect of H2O2 generated from the hydrogel extract on the proliferation of primary dermal fibroblast (Figure 6). In the absence of catalase, fibroblasts exposed to 2 wt% DMA hydrogel extract (2 wt% –) demonstrated complete destruction of cell layer with floated cells in the cell culture medium, which confirmed the sever cytotoxicity of catalase-free extract with extremely low cellular density (Figure 6A). On the other hand, addition of 100 U/mL of catalase (2 wt% +) drastically increased cellular density (2.9×104 ± 377 cells/cm2/mL), which was not statistically different from catalase-containing extract from 0 wt% DMA hydrogel (0 wt% +, 3.3×104 ± 233 cells/cm2/mL, p=0.06). Similarly, fibroblasts proliferation percentage for catalase-containing extracts were also equivalent (64.9 ± 3.2% and 70.5 ± 4.5% for 0 wt% + and 2 wt% +, respectively; p=0.064), indicating that catalase eradicated the cytotoxicity effect of H2O2 generated from hydrogel-bound DMA. The proliferation percentage was significantly lower for extract from DMA-free hydrogel that was not doped with catalase (45.9 ± 5.1%; p=0.001), further confirming that catalase promotes proliferation of fibroblast.

Figure 6.

Immunofluorescent staining of BrdU (green) and DAPI (blue) of primary rat dermal fibroblasts exposed to 0 and 2 wt% DMA hydrogel extract with (+) or without (−) 100 U/mL of catalase (A). Rat dermal fibroblast cell density (B) and percentage of BrdU positive cells (C) exposed to the extract of 0 or 2 wt% DMA hydrogel with (+) or without (−) 100 U/mL of catalase. Letters a–c indicate statistical equivalence for samples labeled with the same letter.

3.6. Subcutaneous implantation

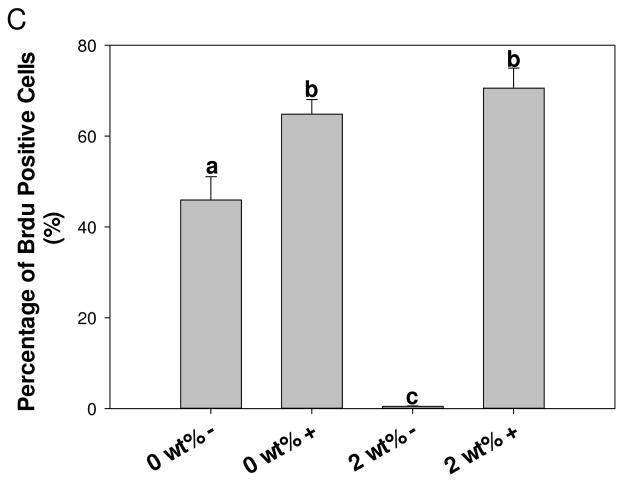

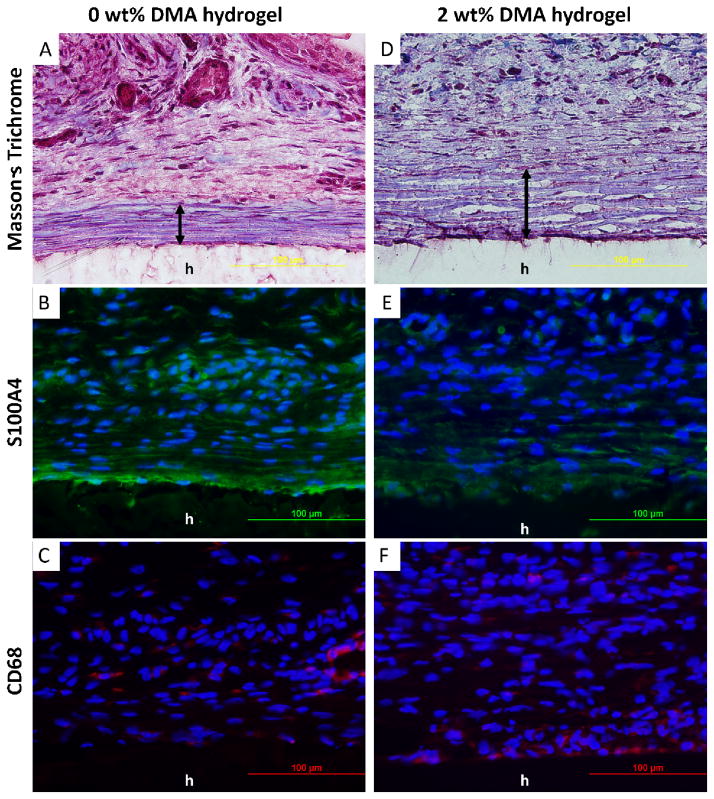

Hydrogels containing 0 and 2 wt% DMA were implanted subcutaneously for 1 and 4 weeks and retrieved with the surrounding tissues for histological assessment. DMA containing hydrogels appeared dark red in color, a clear indication of catechol oxidation and H2O2 production during implantation. DMA-free hydrogels showed no color change over 4 weeks. 1 week implantation results were used to evaluate acute cellular and tissue responses to the hydrogels. Trichrome staining revealed that after 1 week of implantation, the interface between the hydrogel and the surrounding tissue contained a cellular layer composed of macrophages and fibroblasts (MF layer; Figure 7). Collagen was deposited close to the MF layer. The cell density in the MF layer were 3.2 ± 0.4 ×105 cells/mm2 and 5.2 ± 0.6 ×105 cells/mm2 for 0 and 2 wt% DMA hydrogels, respectively (Table 1, p=0.008). For 0 wt% DMA hydrogel, fibroblasts (Figure 7B) and macrophages (Figure 7C) appeared evenly distributed in the MF layer. On the other hand, fibroblasts only existed in a monolayer close to the surface of 2 wt% DMA hydrogel (Figure 7E) while macrophages were distributed across the collagen layer adjacent to the MF layer at an elevated density (Figure 7F). H2O2 generated from DMA containing hydrogel likely stimulated the recruitment of macrophages [28]. Collagen density adjacent to the MF layer was 58.9 ± 6.9 % and 37.1 ± 6.2% for hydrogels containing 0 and 2 wt% DMA, respectively (p=0.03). Fibroblast was the main source of collagen deposition, and the lower collagen density for 2 wt% DMA hydrogel is attributed to lower fibroblast cellular density found in its surrounding tissue.

Figure 7.

Masson’s trichrome (A, D) and immunofluorescent (B, C, E, F) staining of 0 and 2 wt% DMA hydrogel and surrounding tissue after 1 week of subcutaneous implantation. Cell nuclei, fibroblasts, and macrophages were stained by DAPI (blue), S100A4 (green), and CD68 (red), respectively. h : hydrogel; MF : macrophages and fibroblasts layer.

Table 1.

Cell numbers, collagen density, and fibrous capsule thickness assessment of the implanted PAAm hydrogel (0 and 2 wt% DMA) and surrounding tissue retrieved after 1 and 4 weeks subcutaneous implantation.

| 1 week | 4 weeks | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 wt% DMA | 2 wt% DMA | 0 wt% DMA | 2 wt% DMA | |

| Cell density (×105 nuclei/mm2) | 3.1 ± 0.4 | 5.3 ± 0.58 | 3.92 ± 0.34 | 5.25 ± 1.4 |

| p = 0.008# | p = 0.068 | |||

|

| ||||

| Collagen density (%) | 58.9 ± 6.9 | 37.1 ± 6.2 | 80.1 ± 4.2 | 70.8 ± 5.3 |

| p = 0.03# | p = 0.055 | |||

|

| ||||

| Fibrous capsule thickness (μm) | Not yet formed | 38.2 ± 2.6 | 97.0 ± 8.5 | |

| p = 0.0025# | ||||

p < 0.05 indicates significant difference (analyzed by t-test)

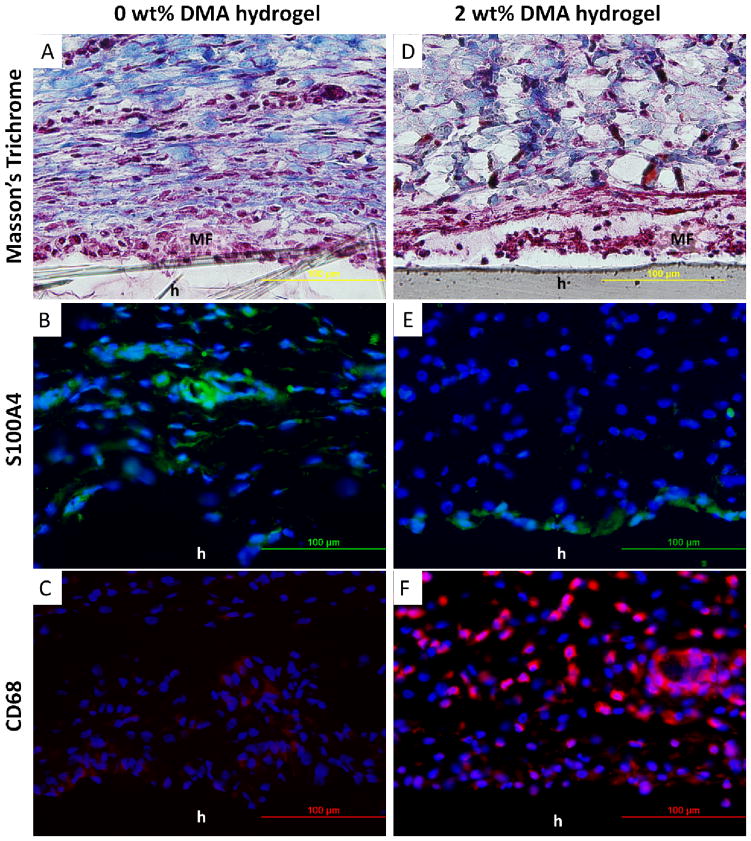

After 4 weeks of implantation, a thin, compacted and aligned fibrous capsule formed around the hydrogels (Figure 8A and B). A thicker but looser fibrous capsule formed surrounding 2 wt% DMA hydrogel (97.0 ± 8.5 μm) compared to a thinner but densely compacted collagen layer surrounding the 0 wt% DMA hydrogel (38.2 ± 2.6μm; p=0.0025; Table 1). There was a decrease in macrophage density but an increase in fibroblast density surrounding 2 wt% DMA hydrogel at week 4 when compared to those of week 1 (Figure 8E and F). The nuclei located in the fibrous capsule surrounded 0 wt% hydrogel were stretched and aligned in parallel to the alignment of the fibrous capsule (Figure 8B), whereas the cell nuclei surrounding the 2 wt% DMA hydrogel were rounded and randomly distributed (Figure 8E). These results further implied a more densely compacted fibrous capsule formation surrounding the 0 wt% DMA hydrogel. There was no difference in the measured cell and collagen density for the two hydrogels (Table 1, p=0.055).

Figure 8.

Masson’s trichrome (A, D) and immunofluorescent (B, C, E, F) staining of 0 and 2 wt% DMA hydrogel and surrounding tissue after 4 week of subcutaneous implantation. Cell nuclei, fibroblasts, and macrophages were stained by DAPI (blue), S100A4 (green), and CD68 (red), respectively. h : hydrogel; double-headed arrows : fibrous capsule.

4. Discussion

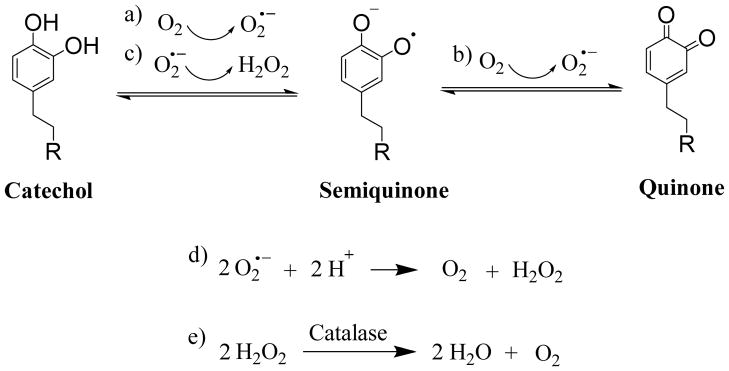

The catechol side chain of DOPA and its derivatives readily undergo autoxidation at neutral to alkaline pH in an oxygenated environment to form the corresponding quinone moiety and reactive oxygen species, such as superoxide anion (O2•−) and H2O2, are generated during the process (Scheme 1) [45]. Molecular dioxygen (O2) oxidizes catechol to semiquinone and is transformed into O2•− in the process (reaction a). O2 further oxidizes semiquinone into its quinone form, further generating O2•− (reaction b). O2•− is a significantly more potent oxidant than O2, and are quickly consumed as it oxidizes catechol to semiquinone to form H2O2 (reaction c). O2•− can also react with proton ions to form H2O2 (reaction d) [46]. When compared to O2•−, H2O2 is more stable and oxidizes catechol at a significantly reduced rate [45]. As such, H2O2 was released from our hydrogel network and was detected using the FOX assay. In the presence of catalase, the enzyme catalyzes H2O2 to water and O2 (reaction e).

Scheme 1.

Proposed mechanism of catechol oxidation and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) generation. R = hydrogel network.

In our experiments, H2O2 generated by hydrogel-bound DMA was captured by cell culture medium extracts, which can be used to separate the cytotoxic effect of H2O2 from the effect of cellular uptake of soluble dopamine. Extracts from these hydrogels generated cytotoxic levels of H2O2 with time. There was a strong correlation between the extent of cytotoxicity response and H2O2 concentration in the hydrogel extracts, where extracts with higher levels of measured H2O2 resulted in a lower cell viability. The cell culture medium extracts of PAAm hydrogel without DMA showed no H2O2 production and were non-cytotoxic, indicating that DMA is the main source for the production of H2O2. When catalase was introduced into the extraction medium, the free-radical scavenging effect of this enzyme significantly reduced H2O2 levels and greatly enhanced cell viability and proliferation. The catalase concentration-dependent cellular response was equivalent for H2O2-doped cell culture medium and extracts from DMA-containing hydrogels. These results collectively suggest that H2O2 generation is one of the main contributors to the cytotoxicity of catechol in culture.

H2O2 is not stable in typical cell culture condition can be depleted within 1 h [47]. However, extracts of DMA-containing hydrogel showed a slow and persistent increase in H2O2 over a 48 h period, potentially due to a slow oxidation process of hydrogel-bound catechol groups. Interestingly, DMA monomer of equivalent concentrations generated significantly higher H2O2 when compared to those of hydrogel extracts. The yield for incorporating DMA into the hydrogel is most likely less than 100% and the DMA content in the hydrogel may be lower than that in the monomer solution. However, given that DMA incorporation is minimally hampered when free-radical polymerization is carried out under an inert environment [33, 34, 48], the observed discrepancy in the production of H2O2 (3–4 times difference) cannot be solely attributed to the reduced yield of DMA incorporation in the hydrogel network. Measured H2O2 levels from DMA monomer dissolved in solution have demonstrated a concentration dependent increase. On the contrarily, when DMA monomer was incorporated into PAAm hydrogel, hydrogel with the highest DMA content (3 wt%) demonstrated the lowest H2O2 generation and the highest cell viability among all the formulations tested (Table S1). Possible reasons for the observed difference in H2O2 generation between DMA monomer solution and the hydrogel extract may be due to reduced water content in hydrogels with increasing DMA content (Table S1). Deswelling of the hydrogel network may have resulted from the formation of the charge transfer complex through π-π interaction between a catechol and a quinone [1, 49]. Hydrogen bonding plays an important role in stabilizing this complex [50], which may have affected the rate of catechol oxidation and H2O2 generation. This deswelled network may have also affected the exchange of cell culture medium during extraction and trapped H2O2 within the hydrogel. Finally, this cage effect may have also reduced oxygen diffusion into the polymer matrix and resulted in slower radical pair formation [51].

Dopamine solution generated the highest H2O2 level when compared to DMA solutions and hydrogel extracts with equivalent concentrations (Figure S3). Dopamine is the only chemical species tested that is capable of undergoing autoxidation-mediated polymerization [11], and generating large quantity of H2O2 during the process. Dopamine solution was also the only sample that demonstrated non-cytotoxic response in its undiluted form (Figure S4). Polydopamine and other polyphenols can scavenge free-radicals and are known antioxidants [20, 44], which may provide cellular protection. Polydopamine have been also demonstrated to be non-cytotoxic and often improved cytocompatibility of materials coated with polydopamine [52, 53]. However, when polydopamine solution was serially diluted with cell culture medium, the protective function of polydopamine may have been reduced and unable to counteract the cytotoxicity effect of H2O2. Addition of catalase to dopamine solution did not affect this trend (data not shown) indicating that there other factors are involved when polydopamine comes into direct contact with L929 fibroblast.

PAAm hydrogel is a highly water swell-able, biocompatible, and non-degradable biomaterials, which has been used in ophthalmic operation [54], breast augmentation [55] and drug delivery [56]. Subcutaneous implantation of DMA-free PAAm control indicated that this hydrogel exhibited minimal inflammatory response as expected. On the other hand, DMA-containing hydrogel exhibited a higher foreign body response as a result of H2O2 generation. After one week of implantation, a higher amount of macrophage was recruited to the tissue surrounding the DMA-containing hydrogel. Elevated ROS level have been reported to promote leukocyte (monocytes and macrophages) recruitment to the tissue-biomaterial interface [28] and stimulate foreign body reaction [23]. Increased number of macrophages generates more ROS, activates phagocytes and leading to the destruction of microorganisms [57]. Additionally, ROS are necessary in the differentiation of M2 macrophage [58], which promote tissue regeneration and anti-inflammatory responses [59, 60]. The presence of macrophage also promoted a thicker fibrous capsule formation surrounding the DMA-containing hydrogel at week 4. After four weeks of implantation, the number of macrophages surrounding the DMA-containing hydrogel decreased and fibroblasts were recruited to form the fibrous capsule, which implied a reduced inflammatory response to the DMA-containing hydrogel. This reduction in the inflammatory response is potentially due to reduced H2O2 generation with time.

Catechol-modified adhesives have been reported to be biocompatible and non-cytotoxic [6, 36, 61]. However, cytotoxicity assays for these in situ curable materials were determined after oxidation crosslinking of the catechol groups were complete. Additionally, these bioadhesives employed strong oxidant that accelerated oxidation crosslinking as opposed to the slow auto-oxidation of catechol in our study. Given that H2O2 are produced during the process of catechol oxidation, it is likely that these materials had ceased to produce H2O2 when the cytotoxicity tests were performed. To our knowledge, there is no study that have investigated the effect of in situ curing or the process of oxidative crosslinking of catechol on biocompatibility. Specifically, our data indicated that significantly higher amount of H2O2 was produced during the process of polydopamine formation (Figure S4). Most importantly, catechol-containing bioadhesives typically require the addition of strong oxidants (i.e., NaIO4) to initiate rapid cohesive and interfacial crosslinking [6, 36, 62, 63]. Additional study is require to evaluate the production of ROS and the biocompatibility of mussel-mimetic bioadhesives during the process of in situ curing.

Here, we reported the cytotoxic effect of H2O2 production from hydrogel-bound dopamine. Our finding is in agreement with other published results where H2O2 generated by phenolic compounds indirectly kills cells [17]. However these previous studies cannot effectively decouple the extracellular toxicity factors (i.e., the effect of H2O2) from intracellular factors (i.e., cellular uptake of soluble catechol species). Our results unambiguously demonstrated that H2O2 generation is one of the main contributors to the cytotoxic response of these adhesive moieties. Given the presence of elevated oxidative stress in typical cell culture conditions [18, 19], catalase supplementation serves as an effective approach to evaluate the in vitro ctytocompatibility of catechol-functionalized biomaterials while eliminating the cytotoxic effect of H2O2. ROS are naturally produced during normal cellular metabolism and functional activities, and have important roles in wound healing, cell signaling, apoptosis, gene expression and ion transportation. Specifically, H2O2 concentrations in the range of 102–103 μM have been found to promote wound healing, while completely removal of H2O2 and H2O2 concentrations in excess of 105 μM retarded wound healing [25, 26]. Our DMA hydrogel system generated 102–103 μM of H2O2 over 48 hrs, which matches the therapeutic window of H2O2 concentrations reported in the literature. Additionally, dopamine has previously demonstrated to have antibacterial property toward Escherichia coli [64, 65]. Tightly controlling the production of H2O2 from mussel-mimetic adhesive biomaterials will be necessary to optimize their performance for a given application (i.e., promotion of wound healing, treating infected wounds, etc.).

5. Conclusion

Network-bound dopamine released cytotoxic levels of H2O2 when catechol oxidized to when the quinone. Introduction of catalase significantly counteracted the cytotoxic effect of H2O2 hydrogel extracts were exposed to L929 and rat dermal fibroblasts in vitro. Catalase supplementation suppressed the elevated oxidative stress found in typical cell culture conditions and can more accurately evaluate the biocompatibility of mussel-mimetic biomaterials. The also induced a higher foreign body reaction to catechol-modified hydrogel in the release of H2O2 subcutaneous implantation model in rat. These results indicate that H2O2 generation is one of the main contributors to the cytotoxicity and elevated foreign body response of the biomimetic catechol moiety. Reported hydrogel system can potentially serve as a model system to decouple the extracellular oxidative cytotoxicity factors from the toxicity of intracellular factors as a result of cellular uptake. Additional studies are necessary to further elucidate the biocompatibility of for a desired application. these biomimetic adhesives and to tune the production of H2O2

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (R15GM104846). YL was supported in part by the Kenneth L. Stevenson Biomedical Engineering Summer Research Fellowship.

Appendix A. Figures with essential colour discrimination

Certain figures in this article, particularly Figures 6A, 7 and 8 are difficult to interpret in black and white. The full colour images can be found in the on-line version, at xxxxx.

Appendix B. Supplementary data

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, FE-SEM images, pore size and equilibrium water content of PAAm hydrogel with different DMA concentration, H2O2 concentration and relative cell viability of DMA monomer and dopamine solution. See DOI: 10.1039/b000000x

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Waite JH. Nature’s underwater adhesive specialist. Int J Adhes Adhes. 1987;7:9–14. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Silverman H, Roberto F. Understanding Marine Mussel Adhesion. Mar Biotechnol. 2007;9:661–81. doi: 10.1007/s10126-007-9053-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Faure E, Falentin-Daudré C, Jérôme C, Lyskawa J, Fournier D, Woisel P, et al. Catechols as versatile platforms in polymer chemistry. Progress in Polymer Science. 2013;38:236–70. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee BP, Messersmith PB, Israelachvili JN, Waite JH. Mussel-Inspired Adhesives and Coatings. Annu Rev Mater Res. 2011;41:99–132. doi: 10.1146/annurev-matsci-062910-100429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sedó J, Saiz-Poseu J, Busqué F, Ruiz-Molina D. Catechol-Based Biomimetic Functional Materials. Adv Mat. 2013;25:653–701. doi: 10.1002/adma.201202343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mehdizadeh M, Weng H, Gyawali D, Tang L, Yang J. Injectable citrate-based mussel-inspired tissue bioadhesives with high wet strength for sutureless wound closure. Biomaterials. 2012;33:7972–83. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.07.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Murphy JL, Vollenweider L, Xu F, Lee BP. Adhesive Performance of Biomimetic Adhesive-Coated Biologic Scaffolds. Biomacromol. 2010;11:2976–84. doi: 10.1021/bm1007794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brodie M, Vollenweider L, Murphy JL, Xu F, Lyman A, Lew WD, et al. Biomechanical properties of Achilles tendon repair augmented with bioadhesive-coated scaffold. Biomed Mater. 2011;6:015014. doi: 10.1088/1748-6041/6/1/015014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sileika TS, Kim H-D, Maniak P, Messersmith PB. Antibacterial Performance of Polydopamine-Modified Polymer Surfaces Containing Passive and Active Components. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2011;3:4602–10. doi: 10.1021/am200978h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cui J, Yan Y, Such GK, Liang K, Ochs CJ, Postma A, et al. Immobilization and Intracellular Delivery of an Anticancer Drug Using Mussel-Inspired Polydopamine Capsules. Biomacromolecules. 2012;13:2225–8. doi: 10.1021/bm300835r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee H, Dellatore SM, Miller WM, Messersmith PB. Mussel-inspired surface chemistry for multifunctional coatings. Science. 2007;318:426–30. doi: 10.1126/science.1147241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pechey A, Elwood CN, Wignall GR, Dalsin JL, Lee BP, Vanjecek M, et al. Anti-Adhesive Coating and Clearance of Device Associated Uropathogenic Escherichia coli Cystitis. The Journal of Urology. 2009;182:1628–36. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee BP, Konst S. Novel Hydrogel Actuator Inspired by Reversible Mussel Adhesive Protein Chemistry. Advanced Materials. 2014;26:3415–9. doi: 10.1002/adma.201306137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee BP, Lin M-H, Narkar A, Konst S, Wilharm R. Modulating the Movement of Hydrogel Actuator based on Catechol-Iron Ion Coordination Chemistry. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical. 2015;206:456–62. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cumming P, Ase A, Laliberte C, Kuwabara H, Gjedde A. In Vivo Regulation of DOPA Decarboxylase by Dopamine Receptors in Rat Brain. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1997;17:1254–60. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199711000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hasegawa T. Tyrosinase-expressing neuronal cell line as in vitro model of Parkinson’s disease. International journal of molecular sciences. 2010;11:1082–9. doi: 10.3390/ijms11031082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Clement M-V, Long LH, Ramalingam J, Halliwell B. The cytotoxicity of dopamine may be an artefact of cell culture. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2002;81:414–21. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.00802.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Halliwell B. The wanderings of a free radical. Free Radic Biol Med. 2009;46:531–42. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.de Groot H, Littauer A. Hypoxia, reactive oxygen, and cell injury. Free Radic Biol Med. 1989;6:541–51. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(89)90047-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Halliwell B. Are polyphenols antioxidants or pro-oxidants? What do we learn from cell culture and in vivo studies? Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 2008;476:107–12. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2008.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Akagawa M, Shigemitsu T, Suyama K. Production of Hydrogen Peroxide by Polyphenols and Polyphenol-rich Beverages under Quasi-physiological Conditions. Bioscience, Biotechnology, and Biochemistry. 2003;67:2632–40. doi: 10.1271/bbb.67.2632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brian N, Ahswin H, Smart N, Bayon Y, Wohlert S, Hunt JA. Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS)-A Family of Fate Deciding Molecules Pivotal in Constructive Inflammation and Wound Healing. European Cells and Materials. 2012;24:249–65. doi: 10.22203/ecm.v024a18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Anderson JM, Rodriguez A, Chang DT. Foreign body reaction to biomaterials. Seminars in Immunology. 2008;20:86–100. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2007.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cooper AM, Segal BH, Frank AA, Holland SM, Orme IM. Transient Loss of Resistance to Pulmonary Tuberculosis in p47 phox−/− Mice. Infection and Immunity. 2000;68:1231–4. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.3.1231-1234.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Loo AEK, Wong YT, Ho R, Wasser M, Du T, Ng WT, et al. Effects of Hydrogen Peroxide on Wound Healing in Mice in Relation to Oxidative Damage. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e49215. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0049215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roy S, Khanna S, Nallu K, Hunt TK, Sen CK. Dermal Wound Healing Is Subject to Redox Control. Mol Ther. 2006;13:211–20. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2005.07.684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pan Q, Qiu W-Y, Huo Y-N, Yao Y-F, Lou MF. Low Levels of Hydrogen Peroxide Stimulate Corneal Epithelial Cell Adhesion, Migration, and Wound Healing. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 2011;52:1723–34. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-5866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rieger S, Sagasti A. Hydrogen Peroxide Promotes Injury-Induced Peripheral Sensory Axon Regeneration in the Zebrafish Skin. PLoS Biol. 2011;9:e1000621. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Arul V, Masilamoni JG, Jesudason EP, Jaji PJ, Inayathullah M, Dicky John DG, et al. Glucose Oxidase Incorporated Collagen Matrices for Dermal Wound Repair in Diabetic Rat Models: A Biochemical Study. Journal of Biomaterials Applications. 2012;26:917–38. doi: 10.1177/0885328210390402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chigurupati S, Mughal MR, Okun E, Das S, Kumar A, McCaffery M, et al. Effects of cerium oxide nanoparticles on the growth of keratinocytes, fibroblasts and vascular endothelial cells in cutaneous wound healing. Biomaterials. 2013;34:2194–201. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.11.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li Z, Wang F, Roy S, Sen CK, Guan J. Injectable, Highly Flexible, and Thermosensitive Hydrogels Capable of Delivering Superoxide Dismutase. Biomacromolecules. 2009;10:3306–16. doi: 10.1021/bm900900e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chelikani P, Fita I, Loewen PC. Diversity of structures and properties among catalases. CMLS, Cell Mol Life Sci. 2004;61:192–208. doi: 10.1007/s00018-003-3206-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee H, Lee BP, Messersmith PB. A reversible wet/dry adhesive inspired by mussels and geckos. Nature. 2007;448:338–41. doi: 10.1038/nature05968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Skelton S, Bostwick M, O’Connor K, Konst S, Casey S, Lee BP. Biomimetic adhesive containing nanocomposite hydrogel with enhanced materials properties. Soft Matter. 2013;9:3825–33. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huebsch N, Gilbert M, Healy KE. Analysis of sterilization protocols for peptide-modified hydrogels. J Biomed Mater Res B. 2005;74B:440–7. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.30155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu Y, Meng H, Konst S, Sarmiento R, Rajachar R, Lee BP. Injectable Dopamine-Modified Poly(ethylene glycol) Nanocomposite Hydrogel with Enhanced Adhesive Property and Bioactivity. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces. 2014;6:16982–92. doi: 10.1021/am504566v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.ISO 10993-5: Biological evaluation of medical devices. Part 5: Tests for cytotoxicity: in vitro methods. International Organization for Standardization; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhao F, Sellgren K, Ma T. Low-Oxygen Pretreatment Enhances Endothelial Cell Growth and Retention Under Shear Stress. Tissue Engineering Part C: Methods. 2008;15:135–46. doi: 10.1089/ten.tec.2008.0321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Harford J. Preparation and isolation of cells. Current protocols in cell biology. 2004;22:2.0.1–2.1.12. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ferreira L, Rafael A, Lamghari M, Barbosa MA, Gil MH, Cabrita AMS, et al. Biocompatibility of chemoenzymatically derived dextran-acrylate hydrogels. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part A. 2004;68A:584–96. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.20102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nichols SP, Le NN, Klitzman B, Schoenfisch MH. Increased In Vivo Glucose Recovery via Nitric Oxide Release. Analytical Chemistry. 2011;83:1180–4. doi: 10.1021/ac103070t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Koschwanez HE, Yap FY, Klitzman B, Reichert WM. In vitro and in vivo characterization of porous poly-L-lactic acid coatings for subcutaneously implanted glucose sensors. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part A. 2008;87A:792–807. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.31824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schreck R, Rieber P, Baeuerle PA. Reactive Oxygen Intermediates as Apparently Widely Used Messengers in the Activation of the Nf-Kappa-B Transcription Factor and Hiv-1. Embo J. 1991;10:2247–58. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb07761.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ju K-Y, Lee Y, Lee S, Park SB, Lee J-K. Bioinspired Polymerization of Dopamine to Generate Melanin-Like Nanoparticles Having an Excellent Free-Radical-Scavenging Property. Biomacromolecules. 2011;12:625–32. doi: 10.1021/bm101281b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mochizuki M, Yamazaki S-i, Kano K, Ikeda T. Kinetic analysis and mechanistic aspects of autoxidation of catechins. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - General Subjects. 2002;1569:35–44. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4165(01)00230-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sawyer DT, Valentine JS. How Super Is Superoxide. Accounts Chem Res. 1981;14:393–400. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Reznikov K, Kolesnikova L, Pramanik A, Tan-No K, Gileva I, Yakovleva T, et al. Clustering of apoptotic cells via bystander killing by peroxides. The FASEB Journal. 2000;14:1754–64. doi: 10.1096/fj.99-0890com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lee BP. Biomimetic compounds and synthetic methods therefor. 7,622,533. US Patent. 2009

- 49.Mijangos F, Varona F, Villota N. Changes in Solution Color During Phenol Oxidation by Fenton Reagent. Environ Sci Technol. 2006;40:5538–43. doi: 10.1021/es060866q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.D’Souza F, Deviprasad GR. Studies on Porphyrin–Quinhydrone Complexes: Molecular Recognition of Quinone and Hydroquinone in Solution. The Journal of Organic Chemistry. 2001;66:4601–9. doi: 10.1021/jo0100547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Denisov ET, Afanas’ev IB. Chapter 13.1.1 Cage effect in solid polymers. Oxidation and Antioxidants in Organic Chemistry and Biology. 2005:13. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yan P, Wang J, Wang L, Liu B, Lei Z, Yang S. The in vitro biomineralization and cytocompatibility of polydopamine coated carbon nanotubes. Applied Surface Science. 2011;257:4849–55. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yang SH, Kang SM, Lee KB, Chung TD, Lee H, Choi IS. Mussel-inspired encapsulation and functionalization of individual yeast cells. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2011;133:2795–7. doi: 10.1021/ja1100189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.da Silva ALB, Bredemeier M, Gebrim ES, Moura EdM. Intraorbital Polyacrylamide Gel Injection for the Treatment of Anophthalmic Enophthalmos. Ophthalmic Plastic & Reconstructive Surgery. 2008;24:367–71. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0b013e3181846245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Unukovych D, Khrapach V, Wickman M, Liljegren A, Mishalov V, Patlazhan G, et al. Polyacrylamide Gel Injections for Breast Augmentation: Management of Complications in 106 Patients, a Multicenter Study. World J Surg. 2012;36:695–701. doi: 10.1007/s00268-011-1273-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ferreira L, Vidal MM, Gil MH. Design of a Drug-Delivery System Based On Polyacrylamide Hydrogels. Evaluation of Structural Properties Chem Educator. 2001;6:100–3. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Seifried HE, Anderson DE, Fisher EI, Milner JA. A review of the interaction among dietary antioxidants and reactive oxygen species. The Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry. 2007;18:567–79. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2006.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhang Y, Choksi S, Chen K, Pobezinskaya Y, Linnoila I, Liu Z-G. ROS play a critical role in the differentiation of alternatively activated macrophages and the occurrence of tumor-associated macrophages. Cell Res. 2013;23:898–914. doi: 10.1038/cr.2013.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Spiller KL, Anfang RR, Spiller KJ, Ng J, Nakazawa KR, Daulton JW, et al. The role of macrophage phenotype in vascularization of tissue engineering scaffolds. Biomaterials. 2014;35:4477–88. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Marchetti V, Yanes O, Aguilar E, Wang M, Friedlander D, Moreno S, et al. Differential Macrophage Polarization Promotes Tissue Remodeling and Repair in a Model of Ischemic Retinopathy. Sci Rep. 2011:1. doi: 10.1038/srep00076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cencer M, Liu Y, Winter A, Murley M, Meng H, Lee BP. Effect of pH on the Rate of Curing and Bioadhesive Properties of Dopamine Functionalized Poly(ethylene glycol) Hydrogels. Biomacromolecules. 2014 doi: 10.1021/bm500701u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lee BP, Dalsin JL, Messersmith PB. Synthesis and Gelation of DOPA-Modified Poly(ethylene glycol) Hydrogels. Biomacromol. 2002;3:1038–47. doi: 10.1021/bm025546n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cencer M, Murley M, Liu Y, Lee BP. Effect of Nitro-Functionalization on the Cross-Linking and Bioadhesion of Biomimetic Adhesive Moiety. Biomacromol. 2015;16:404–10. doi: 10.1021/bm5016333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Iqbal Z, Lai EPC, Avis TJ. Antimicrobial effect of polydopamine coating on Escherichia coli. Journal of Materials Chemistry. 2012;22:21608–12. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhao P, Li J, Wang Y, Jiang H. Broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity of the reactive compounds generated in vitro by Manduca sexta phenoloxidase. Insect Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 2007;37:952–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2007.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.