Abstract

Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PI4,5P2) is an essential lipid messenger with roles in all eukaryotes and most aspects of human physiology. By controlling the targeting and activity of its effectors, PI4,5P2 modulates processes, such as cell migration, vesicular trafficking, cellular morphogenesis, signaling and gene expression. In cells, PI4,5P2 has a much higher concentration than other phosphoinositide species and its total content is largely unchanged in response to extracellular stimuli. The discovery of a vast array of PI4,5P2 binding proteins is consistent with data showing that the majority of cellular PI4,5P2 is sequestered. This supports a mechanism where PI4,5P2 functions as a localized and highly specific messenger. Further support of this mechanism comes from the de novo synthesis of PI4,5P2 which is often linked with PIP kinase interaction with PI4,5P2 effectors and is a mechanism to define specificity of PI4,5P2 signaling. The association of PI4,5P2-generating enzymes with PI4,5P2 effectors regulate effector function both temporally and spatially in cells. In this review, the PI4,5P2 effectors whose functions are tightly regulated by associations with PI4,5P2-generating enzymes will be discussed.

Keywords: phosphoinositide; PI4,5P2; PI4,5P2 effector; PIP kinase; phosphoinositide kinase; interaction

1. Introduction

Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PI4,5P2) is the most abundant species among the 7 known phosphoinositides (PI3P, PI4P, PI5P, PI3,4P2, PI3,5P2 PI4,5P2 and PI3,4,5P3) [1, 2]. Due to its abundance and stable concentration in cells, early studies focused on PI4,5P2 as a substrate for phospholipases and phosphatidylinositol-3 kinases (PI3Ks) to generate other lipid messengers. PI4,5P2 was soon after discovered as a lipid messenger that regulated the interaction of the cytoskeletal protein, band 4.1, with the integral membrane protein, glycophorin [3] and was also shown to interact with profilactin and regulate its ability to modulate actin polymerization [4]. These findings demonstrated that PI4,5P2 could function directly as a lipid messenger, beyond its utilization as a substrate for the generation of other messengers. Following these initial discoveries, hundreds of PI4,5P2 effectors have been identified. These include ion channels [5], receptors [6], Ras family small GTPases [7], actin regulatory proteins [8, 9], regulators of vesicular trafficking [10], scaffolds [11] and nuclear proteins [12]. Furthermore, recent advances in proteomics have putatively identified many proteins that bind PI4,5P2 [13–15].

An important feature of signaling molecules is that their regulated availability at specific times and locations to convey signals as needed [16]. In addition, many messengers vary dramatically in cellular concentration upon agonist stimulation [17]. From this view point, PI4,5P2 is a poor signal as PI4,5P2 is present in comparatively high concentration and its level remains largely unchanged by extracellular stimuli [18]. For example, in resting neutrophils and erythrocytes, total cellular concentrations of PI4,5P2 are approximately 50 µM, while concentrations on the inner leaflet of the plasma membrane, where the majority of PI4,5P2 is found in the cell, are estimated to be at ~5 mM (1–2 mole percent). Stimulation of neutrophils with fMLP, which activates PLC and PI3K, induced only a small drop in PI4,5P2 concentration [2, 19]. Further, studies with PI4,5P2-specific pleckstrin homology (PH) domains fused to GFP to probe the localized PI4,5P2 concentration reveal that PI4,5P2 is uniformly distributed around the plasma membrane, both before and after stimulation in non- polarized cells [20]. However, understanding of PI4,5P2 signaling was impacted by the discovery of a family of proteins that sequester PI4,5P2 at the plasma membrane. Proteins such as myristoylated alanine-rich C-kinase substrate (MARCKS), growth-associated protein 43 (GAP43) and cytoskeleton-associated protein 23 (CAP23) contain basic clusters that mediate an electrostatic interaction with PI4,5P2 [6, 21]. These proteins are present in concentrations of 1–10 µM, comparable to those of PI4,5P2, and bind tightly to PI4,5P2 (the dissociation constant is approximately 10 nM for MARCKS [6]). This suggested that a substantial fraction of PI4,5P2 is sequestered by PI4,5P2 binding proteins (approximately two thirds by a biochemical study [22]) and unavailable for binding to other PI4,5P2 effectors.

The discovery of the numerous PI4,5P2 binding proteins raises a question of how PI4,5P2 availability is regulated spatially and temporally in cells. One direct way of increasing local concentrations of PI4,5P2 could be achieved by releasing the sequestration. In line with this possibility, membrane association of PI4,5P2 sequestering proteins is controlled by extracellular stimuli. For example, MARCKS translocates from the plasma membrane to the cytoplasm when cells are treated with phorbol myristate acetate or insulin, and there is concomitant accumulation of GFP fused PI4,5P2-specific PH domains in the plasma membrane [6, 23, 24]. This indicates that translocation of MARCKS to the cytoplasm frees PI4,5P2. There are three pathways for the direct synthesis of PI4,5P2 from other phosphoinositides, which include: phosphorylation at the 5 hydroxyl of the myo-inositol ring of PI4P by type I phosphatidylinositol phosphate kinases (PIPKIs), phosphorylation at the 4 hydroxyl of the myo-inositol ring of PI5P by type II PIP kinases (PIPKIIs), and dephosphorylation at the 3 hydroxyl of the myo-inositol ring of PI3,4,5P3 by phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) and similar phosphatases [25]. As cellular PI4P concentration is at least 20-fold higher than those of PI5P and PI3,4,5P3 [1, 2], it is generally accepted that the majority of PI4,5P2 is produced by PIPKIs [26].

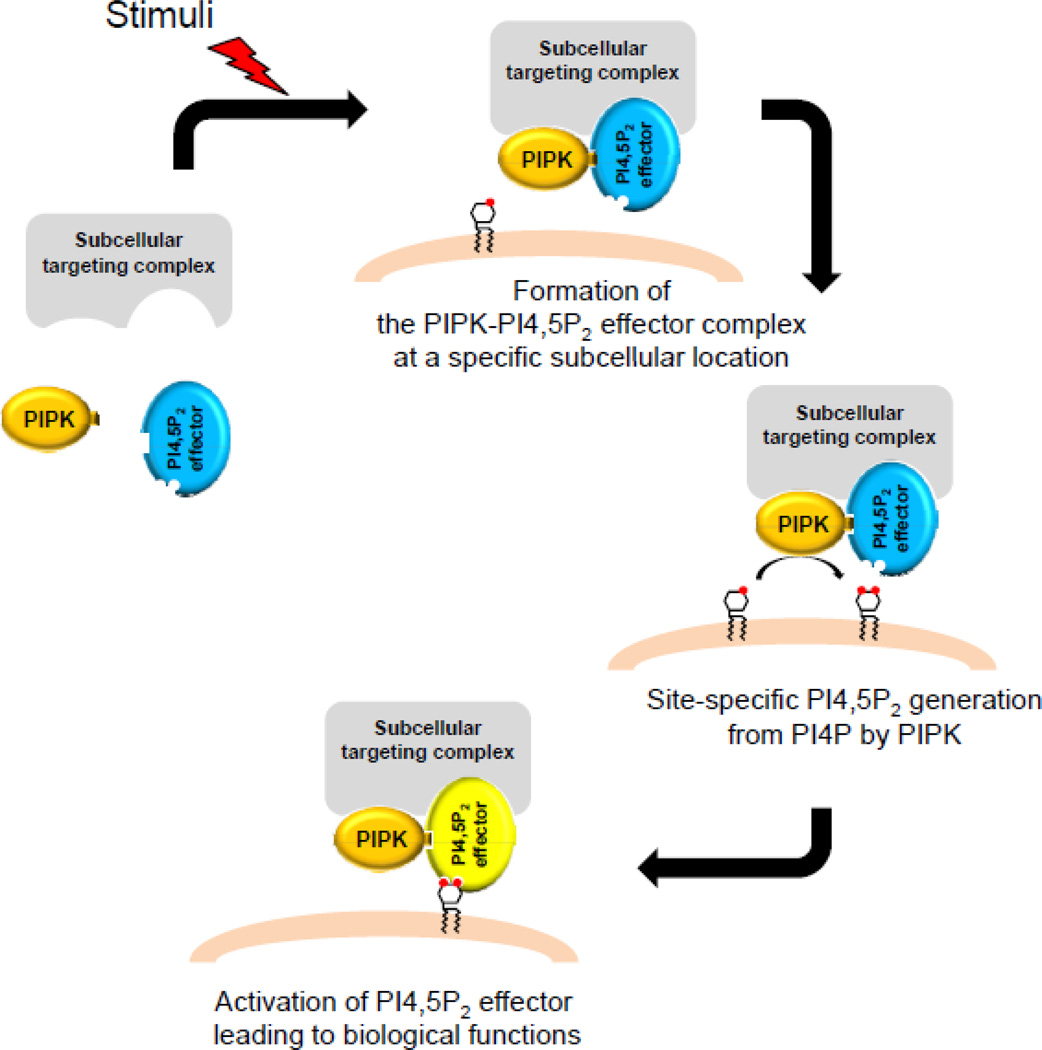

In humans, three distinct genes encode PIPKIs (PIP5K1A encodes PIPKIα, PIP5K1B encodes PIPKIβ, and PIP5K1C encodes PIPKIγ). The nomenclature for the human and murine PIPKIα and PIPKIβ genes are switched. To avoid confusion this manuscript will use the human nomenclature. Each PIPKI gene undergoes alternative splicing, generating multiple splice variants [27]. All PIPKI isoforms contain a highly conserved kinase core domain with invariant catalytic residues [18, 26, 28]. Despite their similarity in the kinase domain, each PIPKI isoform shows unique tissue and subcellular distribution. For example, by Northern analysis, PIPKIα, PIPKIβ and PIPKIγ splice variants have wide tissue distributions, but varying expression levels [29, 30]. The different isoforms also have distinct subcellular distribution. When overexpressed in cells, a large fraction of PIPKIα is found in membrane ruffles and the nucleus, whereas, PIPKIβ localizes at the perinuclear region likely at intracellular organelles such as the Golgi and endosomes [26]. PIPKIγ isoforms show diverse distributions, including the plasma membrane, focal adhesions, endosomes, cell-cell contacts, and the nucleus [8, 30, 31]. The N- and C-terminal domains of PIPKIs are variable between isoforms, but are conserved in each isoform between species. This suggested that the variable regions define functional specificity and cellular location possibly by distinct protein-protein interactions [18]. Many interacting proteins that target PIPKIs to specific cellular locations have since been identified. Remarkably, many of these proteins are PI4,5P2 effectors signifying that PI4,5P2 production is tightly linked to its usage [26]. This concept fits well with basic principles of cell signaling, where a messenger is produced when and where it is needed (see Figure 1 for model).

Figure 1. Synthesis is linked to usage of PI4,5P2 by the association of PIPK with PI4,5P2 effector.

Extracellular stimuli promote the association of PIPK with PI4,5P2 effector. Through interactions with the subcellular targeting complex, the PIPK/PI4,5P2 effector complex is recruited to a specific location. PI4,5P2 generated from PI4P by PIPK then binds and activates PI4,5P2 effector. This assures that PI4,5P2 signal is produced only where and when it is needed.

In this review, we summarize recent advances in PI4,5P2 signaling and the role of PI4,5P2 generating enzymes. Focus will be on how PI4,5P2 generating enzymes work together with PI4,5P2 effectors in regulation of cell migration, vesicular trafficking and nuclear signaling. We also discuss the link between PI4,5P2 production and usage in the context of general signaling pathways.

2. Subcellular distribution of PIP kinases and PI4,5P2 generation

Studies using PI4,5P2-specific PH domains, such as the PH domain of phospholipase C 51 (PLCδ1-PH), fused to GFP revealed that PI4,5P2 is exclusively found in the plasma membrane, where it displays uniform distribution [32]. This uniform and exclusive distribution is unchanged by extracellular stimuli. For example, in migrating neutrophils and Dictyostelium, PI4,5P2 distribution remains unchanged before and after chemotactic stimulation [20]. As these early studies were performed at low resolution without titrating expression of the probes, they are likely not representative of PI4,5P2 distribution in living cells. We have observed that when GFP-PLCδ1-PH is expressed at low concentrations, it largely localizes to intracellular compartments with an accumulation at the leading edges in migrating carcinoma cells (S. Choi and R.A. Anderson, unpublished data). Examination at high resolution with electron microscopy followed by labeling cellular PI4,5P2 with purified PLCδ1-PH fused to glutathione S -transferase demonstrated that PI4,5P2 is present not only in the plasma membrane, but also in membranes of Golgi, endosomes, endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and the nucleus [33]. In line with this study, immunocytochemical analysis with a PI4,5P2-specific antibody identified multiple, distinct pools of PI4,5P2 in the plasma membrane, intracellular vesicles and the nucleus [34, 35]. Additionally, this immunostaining approach revealed that in response to extracellular stimuli PI4,5P2 in the plasma membrane actively redistributes. For example, PI4,5P2 accumulates at the leading edges of fMLP-stimulated chemotacting neutrophils, which is likely mediated by a redistribution of PI4,5P2-generating enzymes [36].

Detection of PI4,5P2 at multiple subcellular locations is further supported by concomitant detection of PI4,5P2-generating enzymes [26, 30, 37–39] and their substrate PI4P [34, 40] at the same locations. The majority of cellular PI4,5P2 is generated by α, β and γ isoform of PIPKIs and splice variants of each isoform are reported. In human, three α, four β and six γ splice variants have been described [27, 30, 37, 41, 42]. Amongst, PIPKIγ splice variants, PIPKIγi1 to PIPKIγi6, show strikingly diverse subcellular distribution. PIPKIγi1, i3 and i6 are largely found in the plasma membrane [11, 42, 43], whereas PIPKIγi2 targets to the focal adhesions when overexpressed [37, 44]. PIPKIγi2 is also found at cell-cell contacts and the recycling endosomes [45, 46]. PIPKIγi4 is present in the nucleus and colocalizes with a nuclear speckle marker SC-35 [30]. PIPKIγi5 is found largely at the cell-cell contacts in confluent epithelial cells and colocalizes with E-cadherin [30, 47]. In mesenchymal-like cells, PIPKIγi5 localizes in intracellular compartments including early/late endosomes and lysosomes [30, 39].

Additionally, subcellular distribution of PIPKIs is altered by extracellular stimuli. When analyzed by fractionation, a substantial portion of PIPKIαand PIPKIγ is cytosolic [11, 48, 49]. In response to platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) stimulation, PIPKIα translocates to membrane ruffles of the plasma membrane [48, 49] and in the nucleus [48]. In non-stimulated breast cancer cells, only ~30% of PIPKIγi1 is bound to membranes. Upon epidermal growth factor (EGF) or integrin receptor activation, membrane bound PIPKIγi1 increases ~2.5-fold and PIPKIγi1 accumulates at the leading edges of migrating cells [11]. Consistently, in phagocytic bone marrow-derived macrophages, PIPKIγi1 is recruited to the phagocytic cup where actin is actively polymerized [50]. PIPKIγi2 also accumulates at the leading edges of migrating breast cancer cells [38]. In chemotacting neutrophils and T lymphocytes, PIPKIγi2 targets to uropods at the rear of cells [51, 52]. PIPKIβ also targets to uropods of chemotacting neutrophils [53]. It is important to note that it is difficult to draw conclusions from studies that are wholly dependent on the overexpression of PIPK isoforms or mutants as the normal targeting and regulation of the PIP kinases could be overwhelmed.

Consistent with studies in cells, genetic alterations of PIPKI isoforms in mice show that each isoform has a unique role in generation of distinct PI4,5P2 pools required for specific physiological functions. PIPKIγ knockout mice displayed perinatal lethality [54], whereas PIPKIα or PIPKIβ knockout mice survive to adulthood with some cell type specific defects [55–57] suggesting an essential role of PIPKIγ during embryogenesis. More recently, mice expressing only PIPKIα by knocking out both PIPKIβ and PIPKIγ were generated and these mice showed perinatal lethality. Since embryos developed until perinatal period, this study indicates that PIPKIα also has a partially overlapping role during embryogenesis [58]. Platelets from PIPKIα knockout mice have defects in PI4,5P2 synthesis and inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3) production by thrombin. PIPKIβ is also implicated in this process as double knockout of PIPKIα and PIPKIβ completely blocked thrombin-stimulated IP3 production [56]. PIPKIβ knockout mice displayed increased anaphylactic responses [57]. Mast cells from these mice showed enhanced cytokine production and degranulation by antigen challenge, and this is likely due to defective actin polymerization by PIPKIβ knockout as actin polymerization is critical for mast cell functions [59]. Interestingly, PIPKIβ knockout reduces PI4,5P2 content in mast cells, whereas IP3 and PI3,4,5P3 levels are increased signifying the role of PIPKIα or PIPKIγ in IP3 and PI3,4,5P3 generation. It is important to note that another PIPKIγ knockout mouse fails to develop beyond embryonic day 11.5 due to defects in cardiovascular development and neural tube closure [60]. However, the cause for the discrepancy between the two different PIPKIγ knockout mice lines remains unclear.

3. PIP kinases regulate PI4,5P2 effectors in cell migration

Cell migration is an essential process controlling many aspects of human physiology including morphogenesis during development, maintenance of tissue integrity and immune response. Consequently, aberrant cell migration is linked to pathological conditions such as cancer, mental retardation, atherosclerosis, and arthritis [8, 61–67]. Cell migration is initiated by extracellular signals such as cytokines, growth factors and extracellular matrix (ECM). These signals modulate many intracellular signaling pathways to eventually induce changes in the actin cytoskeleton and microtubules [66–68]. Early studies demonstrated that sequestration of PI4,5P2 inhibits actin polymerization, whereas artificially increasing PI4,5P2 levels enhances actin polymerization [20, 69–71]. Also, PI4,5P2 is required for microtubule capture at the leading edge membrane [66, 72], but the exact mechanism remains unknown. PI4,5P2 is now well established as a critical component in cell migration by controlling the targeting and activity of cytoskeleton regulators [8, 9, 31, 73]. Below, PI4,5P2-regulated cytoskeleton regulators, whose functions are controlled by an association with PIPKIs will be discussed in detail.

3.1. Talin

In multicellular organisms, focal adhesion complexes are critical structural and functional units that enable cells to integrate signaling inputs from extracellular environments to regulate cell migration [8]. Integrin transmembrane proteins and the talin cytoskeletal binding protein play critical roles in cell migration [8]. PI4,5P2 and PI4,5P2 synthesizing enzymes control integrin activation by talin in the process termed “inside-out” integrin signaling [74, 75]. Adhesion, spreading and migration are all directly influenced by the activation state of integrins and talin in focal adhesion complexes [74, 75]. PI4,5P2 generation by a focal adhesion-targeting splice isoform of PIPKIγ, PIPKIγi2, putatively provides a discrete pool of PI4,5P2 required for talin activation during assembly of focal adhesion complexes [37, 44, 76].

Talin consists of a head domain (approximately 50 kDa) and a large rod domain (220 kDa) [77, 78]. The head domain contains a region that is responsible for β1-integrin tail binding. Within this domain, the N-terminus contains an atypical FERM domain, which is composed of four sub-domains, F0, F1, F2 and F3, arranged in a cloverleaf pattern [77, 78]. The rod domain contains multiple binding sites for vinculin and actin [77]. When inactive, the head domain interacts with the rod domain (in the middle segment), limiting the accessibility of the head domain for β1-integrin tail, vinculin and actin binding [77–79]. This type of autoinhibition is widespread among other FERM domain-containing proteins, including focal adhesion kinase (FAK) and moesin [79]. The F2 and F3 sub-domains in talin contain PI4,5P2 binding sites and the availability of PI4,5P2 is crucial for relieving the intramolecular autoinhibition of talin, promoting the head binding to β1-integrin tail [75, 77–79]. A NMR study indicates that the talin head domain has strong affinity for PI4,5P2 compared to other lipids [75]. A key step in integrin activation is the binding of the F3 sub-domain via an atypical PTB domain to the membrane distal portion of β1-integrin tail via the NPXY motif ([77–80]. Similarly, talin association with membrane proximal NPXY motif in β1-integrin disrupts an interaction with α-integrin, inducing structural rearrangements in the extracellular domain of the integrin that increase the ligands binding [77–80]. Besides the F3 sub-domain, other domains in the talin head also contribute to integrin activation via an interaction between a positively charged patch in the F1 and F2 sub-domains of talin with negatively charged phosphoinositides including PI4,5P2 in the plasma membrane [77–79].

Among the PIPKI isoforms, only PIPKIγi2 directly interacts with talin [37, 38, 76]. PIPKIγi2 binding to talin provides the mechanism for local enrichment of PI4,5P2, which in turn induces the conformational change in talin exposing its integrin binding site [75, 78, 80, 81]. The WVYSPLH motif in the C-terminal tail of PIPKIγi2 interacts with the PTB domain in the F3 sub-domain of talin [44, 82]. The PIPKIγi2-talin interaction possibly induces talin activation as discussed above. However, unlike PI4,5P2, PIPKIγi2 binding to talin does not affect the autoinhibitory conformation of talin as indicated by NMR and biochemical studies, although kinase activity of PIPKIγi2 is increased upon talin binding [83]. In addition, the ability of talin to homodimerize and the presence of additional β1-integrin binding sites in the talin rod domain may provide the mechanism for integrating talin, PIPKIγi2 and integrin into the same complex. Consistently, the ternary complex of PI4,5P2, talin and integrin mediating integrin activation and clustering has been demonstrated [84]. Similarly, a biochemical study has demonstrated the assembly of ternary complex of in migrating cells [38]. Src phosphorylation of PIPKIγi2 and β1-integrin provides the important regulatory mechanism in controlling talin binding with PIPKIγi2 versus β1-integrin [82]. Src phosphorylation of PIPKIγi2 promotes talin binding whereas Src phosphorylation of β1-integrin diminishes talin binding with integrins [82], although the functional role of this process remains to be defined in cell migration. However, in PIPKIγi2 regulation of membrane trafficking the Src phosphorylation of PIPKIγi2 completely blocked the interaction with clathrin adaptor complexes [45, 46] suggesting a regulatory mechanism for PIPKIγi2’s role in trafficking as discussed below (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. A schematic diagram depicting the collaborative function of PIPKIγi2, talin and the exocyst complex in polarized delivery/recruitment of signaling molecules to the leading edge of migrating cells.

PI4,5P2 synthesized by PIPKIγi2 facilitates the polarized recruitment of the exocyst complex and its associated cargo molecules to the leading edge. Exo70 and Sec3 are PI4,5P2-binding proteins of the exocyst complex, which is involved in vesicle trafficking processes before SNARE-mediated fusion. Talin, a cytoskeletal protein, remains intramolecularly constrained in the absence of PI4,5P2. PI4,5P2 generated by PIPKIγi2 relieves the intramolecular inhition of talin, which exposes its head domain that binds to the cytoplasmic tail of p-integrins to convey “Inside-out” integrin signaling. Increased assembly of PIPKIγi2 with talin and the exocyst complex in migrating cells also promotes the PI4,5P2 signaling in control of polarized vesicles trafficking towards reorganizing/remodelling plasma membrane of the leading edge.

3.2. Rho family small GTPases

Rho family small GTPases, such as Rac1, Cdc42 and RhoA, are master regulators of the actin cytoskeleton and microtubules [66–68]. They have polybasic clusters that target them to the plasma membrane for function. Studies with phosphoinositide-specific phosphatases reveal that multiple phosphoinositide species including PI4P, PI4,5P2 and PI3,4,5P3 mediate Rho family small GTPase association with the plasma membrane via electrostatic interactions [7], which is a mechanism utilized by multiple proteins [6, 85]. Similar to other phosphoinositides, PI4,5P2 is present in a limiting concentration for effectors (see above), thus their plasma membrane targeting may require de novo synthesis of PI4,5P2. Consistently, the plasma membrane targeting of small GTPases is controlled by PIPKI isoforms. Rac1 and RhoA associate with all three PIPKI isoforms in vitro [86]. In vivo, PIPKIα is required for Rac1 localization at the plasma membrane [49], whereas PIPKIβ is recruited to the plasma membrane by Rac1 [87]. Further, RhoA signaling is required for the translocation of PIPKIβ to the plasma membrane [28, 88].

An association of Rho family small GTPases with PIPKIs regulates their function in cell migration. PIPKIα controls PDGF- and integrin-induced cell migration by regulating Rac1 translocation and activation at the leading edge membrane [49]. PIPKIα-mediated actin polymerization and membrane ruffle formation are dependent on Rac1 activity, and a PIPKIα-binding defective Rac1 mutant fails to mediate these processes [48, 49, 70] suggesting that PIPKIα and Rac1 mutually regulate their activity in actin polymerization. In neuronal cells, PIPKIα and PIPKIβ induce neurite retraction that is dependent on Rac1 or RhoA activity [88–90]. A PIPKIβ mutant that is unable to interact with Rac1 fails to translocate to the plasma membrane, resulting in defective retraction [87]. Rac1-mediated PIPKIβ translocation to the plasma membrane facilitates neurite retraction, as PI4,5P2 promotes vinculin-dependent adhesion turnover [91, 92]. Although PIPKIs do not directly interact with Cdc42, PIPKIs are implicated in Cdc42-induced de novo actin polymerization. Cdc42 and PI4,5P2 synergistically activate N-WASP to promote Arp2/3 complex-mediated actin polymerization [93]. Consistently, overexpression of PIPKIα or PIPKIβ induces N-WASP- and Arp2/3 complex-dependent actin polymerization [94], and a physical interaction of PIPKIs with Arp2/3 complex is reported [8].

3.3. IGGAP1

IQGAP1 is a member of the IQ motif containing GTPase activating protein family and controls cell migration by functioning as a key regulator of the actin cytoskeleton and microtubules [66, 68]. In many cell types, IQGAP1 is targeted to the leading edge membrane of migrating cells [11, 72, 95–98], and this localization is controlled by an association of leading edge-targeted proteins such as Rac1, Cdc42, Dia1 and the Exocyst complex [99–102]. In addition to these factors, PIPKIγ binding is also required for IQGAP1 targeting to the leading edge and control of migration [11]. In vitro, a conserved region found in all six PIPKIγ interacts with IQGAP1 on the IQ domain. In vivo, PIPKIγ-binding is sufficient to recruit IQGAP1 to the leading edges as a PIPKIγ-binding defective IQGAP1 mutant is unable to target to the leading edge [11] (Figure 3).

Figure 3. A model of IQGAP1 activation by PIPKIγ and PI4,5P2.

Integrin or growth factor receptor activation induces activation of upstream regulators of IQGAP1 including PKC, Rho family GTPases and PIPKIs. The N-terminus of IQGAP1 in unstimulated state forms an intramolecular interaction with the C-terminus. Phosphorylation at Ser1441 and Ser1443 inhibits this intramolecular interaction exposing the IQ domain for PIPKIγ interaction. Phosphorylation also partially relieves the intramolecular interaction between the GRD and RGCT domains. PIPKIγ mediates IQGAP1 recruitment to the leading edge membrane. At the leading edge, PIPKIγ generates PI4,5P2 from PI4P PI4,5P2 then binds to the RGCT domain, completely relieving the autoinhibitory interaction between the GRD and RGCT domains. Cdc42 or Rac1 binding at the GRD domain also induces this process. The relieved RGCT domain recruits microtubules via an interaction with APC or CLIP-170, and facilitates actin polymerization by activating N-WASP.

At the leading edge membrane, IQGAP1 regulates actin polymerization and recruits microtubules that are essential for membrane protrusion and establishment of migrating cell polarity [66, 67, 98, 103]. For this role, IQGAP1 interacts with N-WASP and the interaction relieves an autoinhibitory conformation exposing the VCA domain of N-WASP. The exposed VCA domain, then, activates Arp2/3 complex-mediated de novo actin polymerization [98]. IQGAP1 also interacts with the microtubule plus end regulators, CLIP-170 and adenomatous polyposis coli (APC). These interactions with IQGAP1 dynamically link microtubules to the leading edge [99, 100]. The N-WASP, CLIP-170 and APC interaction region on IQGAP1 is within the RGCT domain that is otherwise masked by an autoinhibitory interaction with the GRD domain [98, 104] (Figure 3). Rac1 and Cdc42 binding to the GRD domain in vivo or phosphorylation at Ser1441 and Ser1443, between the GRD and RGCT domains, in vitro relieves the autoinhibitory interaction [99, 100]. In addition to these factors, phosphoinositide binding also regulates IQGAP1 function by relieving the autoinhibitory interaction [11]. In vitro, IQGAP1 interacts with multiple phosphoinositide isomers [13, 14, 105] and the phosphoinositide binding site is localized to a polybasic sequence located in the RGCT domain [11]. PI4,5P2-binding on the RGCT domain specifically relieves the autoinhibitory interaction and regulates N-WASP-Arp2/3 complex-dependent actin polymerization [11, 98]. Strikingly, when expressed in cells, an IQGAP1 mutant that is defective in PI4,5P2-binding induces multiple leading edges [11] suggesting that PI4,5P2-binding is important for IQGAP1 to regulate cell polarity. Consistently, a Rac1/Cdc42 binding defective IQGAP1 mutant expressed in Vero epithelial cells also induces multiple leading edges as its interaction with CLIP-170 is enhanced irrespective of the Rac1/Cdc42-binding status [100].

IQGAP1 activation requires Rac1/Cdc42-binding on the GRD domain, PIPKIγ-binding on the IQ domain, PI4,5P2-binding on the RGCT domain, and phosphorylation at Ser1441 and Ser1443 possibly in a stepwise manner. Phosphorylation at the serine residues, likely by protein kinase C (PKC) isoforms or other kinases, is required for Rac1/Cdc42-binding [104]. PIPKIγ-binding to the IQ domain is followed by phosphorylation [11], and finally both PI4,5P2- and Rac1/Cdc42-binding are required for full activation of IQGAP1 [11, 106]. Based on these findings, we propose a mechanism of IQGAP1 activation in actin polymerization and microtubule recruitment at the leading edge (Figure 3).

3.4. Gelsolin

Gelsolin is a PI4,5P2 effector that is also a dual function actin binding protein. Gelsolin severs actin filaments in the middle or caps the fast growing barbed ends of actin filaments [107]. The capping function of gelsolin is regulated by PI4,5P2-binding that induces gelsolin dissociation from actin and allows actin filament assembly at the barbed ends [108]. PI4,5P2 induces actin polymerization at the N-cadherin-mediated cell-cell contacts by regulating gelsolin [109]. As gelsolin associates with PIPKIγ [110], PI4,5P2 produced by PIPKIγ may directly control gelsolin dissociation from actin filaments and subsequent incorporation of actin monomers at cell-cell contact sites [109].

3.5. Src tyrosine kinase

Another key signaling molecule in migration is the Src non-receptor tyrosine kinase, which regulates a plethora of cell functions. Src targets to focal adhesions by interacting with many adhesion components, including integrin, talin and FAK [111]. Src also interacts with PIPKIγi2 and this interaction regulates Src focal adhesion targeting and activation [112]. The kinase activity of Src remains suppressed by an intramolecular interaction of the SH2 domain with phosphorylated Tyr527 at the C-terminus [113, 114]. Interestingly, the PIPKIγi2 binding site on Src is within the C-terminal region including Tyr527 [112], suggesting that the interaction with PIPKIγi2 might activate Src by relieving the autoinhibitory interaction. Polybasic residues at the N-terminus of Src mediate membrane binding through interaction with phosphoinositide species [115]. Mutating these residues to neutral amino acids blocked Src activation by PIPKIγi2 [112]. Collectively, these results indicate that PIPKIγi2 and its generation of PI4,5P2 regulate Src recruitment to and activation at focal adhesions.

3.6. Is calpain a PI4,5P2 effector in migration?

For efficient cell migration, adhesions have to be dynamic and at the cell rear must be dissolved for retraction, which is largely mediated by RhoA-dependent actomyosin contractility and calpain-dependent proteolysis of adhesion components [62, 67, 68]. PIPKIβ and PIPKIγi2 target to the cell rear and regulate adhesion disassembly. In chemotacting neutrophils, PIPKIβ specifically localizes at the retractile tails of cells by an association with 4.1-ezrin-radixin-moesin (ERM)-binding phosphoprotein 50 (EBP50) [116]. The EBP50 binding region on PIPKIβ is within the 83 C-terminal amino acids, which are not present in other PIPKI isoforms. This PIPKIβ-specific interaction with EBP50 mediates PIPKIβ association with ERM proteins whose activities are regulated by PI4,5P2-binding [107] and the Rho GDP dissociation inhibitor (RhoGDI) [52]. As ERM proteins inhibit RhoGDI, leading to RhoA activation [117], localized PI4,5P2 production at the cell rear controls cell contractility [52]. Calpain is a calcium-dependent protease that cleaves several adhesion components at the trailing edges, such as vinculin and talin [118]. PI4,5P2-binding to calpain enhances calpain activity by decreasing the calcium requirement for its activation [119]. Although a calpain interaction with PIPKIs has not been reported, calpain activity is potentially regulated by a PIP kinase at the trailing edges of migrating cells [8]. In support of this possibility, PI4,5P2 accumulates at the uropod of migrating neutrophils and overexpression of a kinase inactive form of PIPKIγi2 compromises uropod formation in which calpain activity is essential [52].

4. PIP kinases and PI4,5P2 effectors regulate membrane trafficking

The PIP kinases, and other phosphoinositide kinases and phosphatases have unique subcellular targeting and regulate specific processes [18, 26, 31]. This compartmentalized and effector linked synthesis of phosphoinositides is critical for membrane trafficking, as localized synthesis of phosphoinositides regulates key effector molecules in trafficking pathways [31, 120, 121]. Within the cell, the numerous phosphoinositide isomers vary in location and quantity. This is regulated by multiple kinases and phosphatases, which maintain a distinct distribution for each lipid [28]. The precursor to all phosphoinositide signals, phosphatidylinositol (PI), is synthesized on the ER. From there, PI is distributed throughout the cell where it is further modified [122, 123]. There is evidence that some phosphoinositides are concentrated at distinct compartments. These include, PI4P at the Golgi, PI3P and PI3,5P2 at early and late endosomes, respectively [120, 121]. In the past, PI4,5P2 was thought to be primarily confined to the plasma membrane, however, a recent explosion of evidence indicates diverse functions for PI4,5P2 at multiple intracellular locations. Below, PI4,5P2-modulated trafficking regulators whose functions are controlled by select PIPKIs will be discussed.

4.1. AP complex

Adaptor protein (AP) complexes are key components of clathrin coats in the post-Golgi and endocytic membrane trafficking pathways [124]. The formation of a clathrin coat is not through a direct interaction of clathrin with the membrane, and instead adaptor proteins are involved in recruiting clathrin. Each AP complex contains subunits that are responsible for phosphoinositide or cargo binding. The phosphoinositide and cargo binding is highly selective, allowing for the formation of clathrin coats at specific membrane compartments. At the Golgi, clathrin coats are important in the formation of vesicles and fission events needed for cargo exit. Clathrin adaptors, including the AP1 complex, EpsinR and Golgi-localized γ-ear containing, Arf binding proteins (GGAs), bind to and are activated by PI4P, to recruit clathrin to the Golgi [125–128]. Loss of function studies for the PI4 kinases, which generate PI4P, demonstrate the role of PI4P in recruiting clathrin coats. Knockdown of the trans-Golgi network (TGN) associated PI4KIIα inhibits the trafficking of proteins from the Golgi and also the recruitment of the AP1 complex, which can be overcome by administering PI4P or PI4,5P2 to knockdown cells [125]. The ability of PI4,5P2 to rescue these phenotypes suggests that PIPKIs also participate in Golgi functions [129].

Outside of the Golgi, PI4,5P2 regulates several steps in trafficking to and from the plasma membrane. For example, in epithelial cells, there is a specific clathrin AP complex associated with basolaterial sorting, called the AP1B complex. PIPKIγi2 regulates the trafficking of cargo to the basolateral surface [130]. This is mediated through a YxxØ sorting motif (where x is any amino acid and Ø is an amino acid with a bulky hydrophobic side chain) found in the PIPKIγi2 C-terminus that allows for specific association with the AP1B complex through the µ2 subunit. Additionally, the formation of PI4,5P2 is enhanced by association with AP1B [130]. In this scenario, the PI4,5P2 produced by PIPKIγi2 binds to the AP1B complex to enhance its function in recruiting clathrin coats. PIPKIγi2 also interacts with the β2 subunit of the AP2 complex by a C-terminal sequence conserved in all PIPKIγ isoforms that is close to the junction of the PIPKIγi2 C-terminal extension [131, 132]. Thus, there are multiple interaction sites between PIPKIγ and the AP complexes. Also, α subunit of AP2 complex interacts with PI4,5P2 and the PI4,5P2 binding is critical for initial membrane association of AP2 complex [133, 134]. However, it remains to be defined whether α subunit of AP2 complex interacts with PIPKIs.

At the plasma membrane, PI4,5P2 has been well characterized in the regulation of endocytosis. Clathrin adaptors, such as the AP2 complex and Epsin1–3, dynamin, β-arrestin, Numb, and Dab2, regulate recruitment of clathrin to the plasma membrane at sites of endocytosis, and PI4,5P2 regulates the recruitment and activation of these proteins [45, 135–138]. The PIPKIs that generate PI4,5P2 are important in this process and physical association of clathrin adaptors with PIPKIs is defined [138]. Knockdown of PIPKIβ was found to inhibit transferrin receptor endocytosis [139]. Additionally, there is a direct interaction between PIPKIγi2 and the AP2 complex [45, 131]. Increased expression of PIPKIγi2 enhances the endocytosis of transferrin, while a PIPKIγi2 kinase inactive mutant or siRNA knockdown of PIPKIγ inhibits endocytosis [45]. Besides their roles in clathrin recruitment, Epsin, and similar proteins, also regulate membrane deformation, and are able to elongate the membrane into tubules to assist in formation of vesicles [137]. Membrane deformation is also mediated by the actin cytoskeleton to generate force. PI4,5P2 is known to regulate many actin regulating proteins, including N-WASP and Arp2/3 complex. PI4,5P2 can recruit these proteins to sites of endocytosis and stimulate actin branching and polymerization important for membrane deformation during endocytosis [140]. At the final stages of endocytosis, PI4,5P2 also recruits and activates the GTPase, dynamin, to complete fission and release of the endocytic vesicle from the plasma membrane [141].

4.2. Exocyst complex

The exocyst complex is a multiprotein complex essential for polarized delivery and tethering of secretory vesicles to specific domains of the plasma membrane for secretion [142]. This complex is thought to function prior to SNARE-mediated vesicle fusion with the plasma membrane [142]. Exocyst is composed of eight subunits (Sec3, Sec5, Sec6, Sec8, Sec10, Sec15, Exo70 and Exo84) that interact with each other and are thought to organize into distinct sub-complexes. The subunits that define the targeting patch on the plasma membrane form one sub-complex and the other subunits form a separate complex on a cargo-laden vesicle, with both sub-complexes functioning together at the final step of vesicle delivery/tethering on the plasma membrane [143] (Figure 2). Furthermore, the exocyst complex interacts with key regulators of vesicle trafficking such as Rab11, Arf, RalB and Rho GTPases [143].

In epithelial cells, PIPKIγ and the exocyst complex play crucial roles in maintaining adherens junctions and apical-basal polarity by regulating endocytic trafficking of E-cadherin [144]. PIPKIγ directly associates with Exo70 and Sec6 subunits of the exocyst complex [38, 144]. Sec3 and Exo70 have clusters of basic residues (at the N-terminus of Sec3 and the C-terminus of Exo70) that mediate the interaction of the exocyst complex with PI4,5P2 in the plasma membrane [145, 146]. This provides a mechanism for polarized delivery of E-cadherin to adherens junctions in the plasma membrane. However, in many carcinoma cells, E-cadherin expression is lost. In these cells, the exocyst complex redistributes from the adherens junctions to the leading edges and may regulate trafficking of other cargos [147]. In migrating cells, PIPKIγ and the exocyst complex colocalize at the leading edges [38]. The loss of PIPKIγ profoundly affects the recruitment and localization of the exocyst complex, indicating that the interaction with PIPKIγ facilitates recruitment of the exocyst complex to the leading edges. In addition, the association of PIPKIγ with the exocyst complex is highly induced at the onset of cell migration [38] (Figure 2). This would ensure the efficient polarized recruitment and delivery of transmembrane proteins and signaling molecules that are required for nascent adhesion formation in migrating cells. Consistently, knockdown of PIPKIγ and the exocyst complex profoundly affect leading edge formation, polarized recruitment of integrins and cell migration [38, 142, 147, 148] (Figure 2). The spatial targeting of integrins is regulated by vesicle associated PIPKIγi2. At talin rich sites, phosphorylation of PIPKIγi2 by Src may block PIPKIγi2 interaction with trafficking complexes and enhances its interaction with talin [38]. This could regulate the localized secretion of integrins to talin rich sites of developing focal adhesions [73]. The targeting of integrins at talin rich sites along with the generation of PI4,5P2 could enhance inside out activation of integrins and formation of stable adhesion complexes [38, 73] (Figure 2).

These complexes may also mediate the polarized recruitment of growth factor receptors in migrating cells (N. Thapa and R.A. Anderson, unpublished data). In addition, there is increasing evidence that the exocyst complex plays key roles in autophagy [149–151] consistent with roles for the PIP kinases in autophagy.

4.3. Sorting nexins

The sorting nexins are an evolutionary conserved family of eukaryotic proteins that regulate a wide range of trafficking pathways, including lysosomal sorting, recycling pathways and endocytosis [152–156]. All sorting nexin family members contain a Phox homology (PX) domain, which mediates binding to phosphoinositides [153, 157–160]. Therefore, the interplay of phosphoinositides, sorting nexins and the enzymes that generate phosphoinositide signals is essential for proper regulation of trafficking.

Sorting nexin 5 (SNX5) was identified as an interactor of PIPKIγi5 in a yeast two-hybrid screen [39], and the closely related SNX6 was also found to interact with PIPKIγi5 [47]. PIPKIγi5, SNX5 and SNX6 are found at early and late endosomes where PI3P and PI3,5P2 are the most abundant phosphoinositide species. While most PX domains have specificity for PI3P, solution of the SNX5 PX domain crystal structure revealed binding specificity for PI4,5P2, but not PI3P [161]. Additionally, a subset of sorting nexins, including SNX5 and SNX6, contain a phosphoinositide binding Bin/Amphiphysin/Rvs (BAR) domain [157, 159]. At endosomes, production of PI4,5P2 by PIPKIγi5 promotes an association of SNX5 with Hrs, a subunit of endosomal sorting complex required for transport (ESCRT) complex that controls EGF receptor sorting to the intraluminal vesicles of the multivesicular body [39, 162]. The mechanism of how PI4,5P2 regulates the SNX5-Hrs interaction is unclear. One possibility is that PI4,5P2 binding on the PX and BAR domain of SNX5 induces a conformational change that enhances Hrs binding. Additionally, PI4,5P2 generation on endosomes may recruit SNX5 to specific regions of endosomes where SNX5 and Hrs can function to sort specific cargos [163–165].

Furthermore, SNX5 and SNX6 function with PIPKIγi5 to control endosome-to-lysosome trafficking of E-cadherin [47]. Treatment of polarized epithelial cells with hepatocyte growth factor initiates the disassembly of adherens junctions and eventual degradation of E-cadherin at lysosomes. PIPKIγi5 directly binds E-cadherin and promotes its lysosomal degradation, and PI4,5P2 generation by PIPKIγi5 is required for this process [47]. However, SNX5 and SNX6 inhibit E-cadherin lysosomal targeting in this pathway [47]. The role for SNX5, SNX6 and PIPKIγi5 interaction in regulating the trafficking of other receptors requires further investigation.

Additionally, other sorting nexins may be regulated by PIPKI. For example, SNX9 binds to PI4,5P2 and regulates endocytosis by controlling membrane dynamics [166, 167]. PIPKIα, PIPKIβ and PIPKIγ all bind to the SNX9 PX domain [167]. Further this interaction enhanced kinase activity of PIPKIγi2 in vitro [167]. Thus, SNX9 represents another PI4,5P2 effector that regulates endocytosis and interacts with PIPKIs. As the PX domain is present in all sorting nexins, there is the potential that PIPKI and sorting nexins may control additional trafficking pathways.

5. PIP kinases regulate PI4,5P2 effectors in the nucleus

Several phosphoinositide species, including PI4,5P2, are found in the nuclear envelope and intra-nuclear non-membranous structures such as at nuclear speckles, a compartment that lacks membrane structures [168, 169]. Nuclear PI4,5P2 levels change, although modestly, upon various stimuli [170–172], supporting roles for PI4,5P2 signaling in the nucleus. Similar to the plasma membrane, PI4,5P2 in the nucleus is used by nuclear PI3Ks or phospholipases to generate downstream second messengers [173–176]. Moreover, nuclear PI4,5P2 also functions as a direct messenger that binds and regulates nuclear PI4,5P2 effectors. Recent progress has identified a set of nuclear PI4,5P2 effectors directly involved in multiple processes, including transcription [177–180], mRNA processing [181–185], mRNA export [186, 187], chromatin remodeling [180], stress responses [185], DNA repair, and mitosis [188]. The PIP kinases responsible for PI4,5P2 generation in the nuclear envelope are not clear, but the intra-nuclear PIP kinases and PI4,5P2 signaling are more defined.

To date, there are 4 distinct PIP kinases found in the nucleus, PIPKIα [183], PIPKIγi4 [189], PIPKIIα and PIPKIIβ [190, 191], all of which are found concentrated at nuclear speckles where the PIP kinases specifically associate with their interacting proteins, including PI4,5P2 effectors. PIPKIγi4 is the most recently identified nuclear PIPKI, but its function has not yet been determined [189]. PIPKIIα and PIPKIIβ associate with each other in the nucleus [191–193], and their major functions are linked to regulation of nuclear PI5P levels, and subsequent PI5P signaling [192, 194]. Compared with the other nuclear PIP kinases, the function of PIPKIα in the nucleus is the best characterized and will be discussed below as a model for PIP kinase mediated PI4,5P2 signaling in the nucleus.

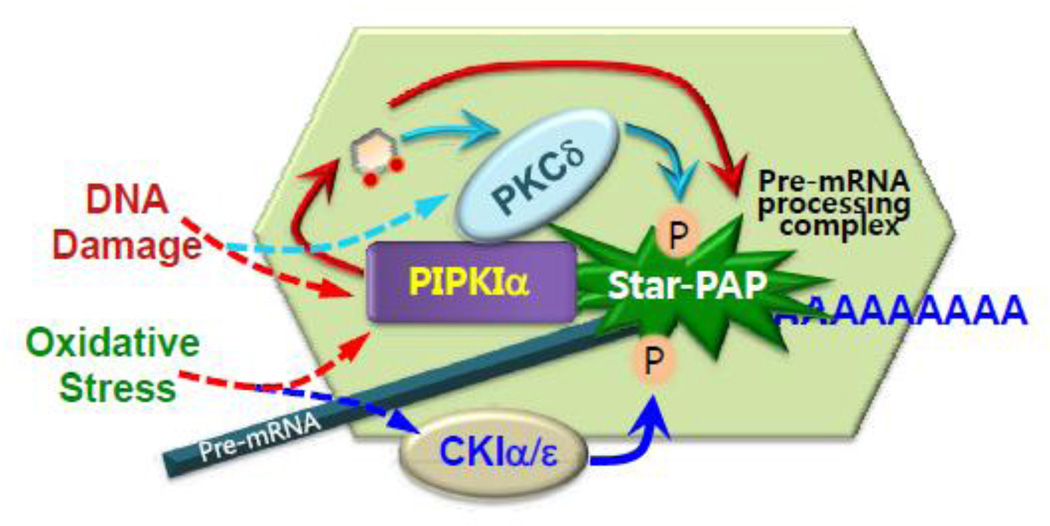

PIPKIα specifically associates with the PI4,5P2 effector Star-PAP (for Speckle Targeted PIPKIα Regulated-Poly(A) Polymerase, a non-canonical poly(A) polymerase (PAP), that is critical for the 3’ cleavage, polyadenylation and expression of select mRNAs [183, 195]. Sufficient evidence indicates that PIPKIα, PI4,5P2 and Star-PAP function together in a complex to control the mRNA processing and expression of select mRNAs [182, 183, 196]. In vitro, Star-PAP activity is dramatically stimulated by PI4,5P2, but not other phosphoinositide or inositol phosphate species, indicating that Star-PAP is a specific PI4,5P2 effector [183]. Importantly, both the PIPKIα interaction and PI4,5P2 stimulation of the poly(A) polymerase activity are specific for Star-PAP but not canonical PAPs [183], emphasizing the unique role for Star-PAP in PIPKIα-mediated nuclear PI4,5P2 signaling (Figure 4).

Figure 4. PIPKIα defines nuclear PI4,5P2 specificity by associating with nuclear PI4,5P2 effectors.

Upon stress signals, PIPKIα controls Star-PAP mediated mRNA processing by directly interacting with and generating PI4,5P2 to activate Star-PAP. In response to different upstream stress signals, two sets of distinct kinases CKIα/ε or PKCδ directly phosphorylate Star-PAP, which is required for full activation of its poly(A) polymerase activity. Interestingly, both CKIα and PKCδ are regulated by PI4,5P2. Similar to Star-PAP, PKCδ directly associates with PIPKIα and is activated by PI4,5P2 to phosphorylate Star-PAP. The PIPKIα coordinated PI4,5P2 signaling controls Star-PAP mediated 3’ processing of select mRNAs.

The PI4,5P2 generated by PIPKIα appears to directly activate Star-PAP and also regulates other components of the Star-PAP complex, as exemplified by the Ser/Thr kinase casein kinase I (CKI) and protein kinase C δ (PKC5), both of which are required to activate Star-PAP for mRNA processing [181, 182, 185]. The functionally redundant CKI isoforms α and ε phosphorylate Star-PAP at the proline rich region (PRR) upon oxidative stress, which is critical for Star-PAP polyadenylation activity. Importantly, the activity of CKIs is inhibited by PI4,5P2 [181, 185]. Though the CKIs are constitutively active, oxidative stress induces Star-PAP phosphorylation, suggesting that the CKI kinase activity may be regulated recruitment to the Star-PAP complex [185, 197]. The CKIα kinase activity towards Star-PAP is PI4,5P2 sensitive as PI4,5P2 inhibits CKIα-mediated Star-PAP phosphorylation in vitro in a dose dependent manner [181, 185]. Potentially, upon oxidative stress, changes in PI4,5P2 signaling in the Star-PAP complex might relieve the PI4,5P2-mediated CKI inhibition, resulting in Star-PAP phosphorylation, which allows for PI4,5P2 stimulation of Star-PAP activity (Figure 4).

While CKIs control Star-PAP activation downstream of oxidative stress, PKCδ is an additional PI4,5P2 effector that similarly activates Star-PAP upon DNA damage by direct phosphorylation [182]. PKCs are well known as kinases that bind and are activated by diacylglycerol (DAG), but some PKCs also directly bind and are regulated by PI4,5P2 [198–201]. DNA damage induces recruitment of PKCδ into the Star-PAP complex that is dependent on the PIPKIα-PKC5 interaction [182]. PIPKIα binding inhibited PKCδ activity and phosphorylation of Star-PAP in vitro. Intriguingly, PKCδ binding to PIPKIα blocked activation of PKCδ by a phorbol ester, a DAG analog, yet when bound to PIPKIα the PKCδ activity was stimulated by PI4,5P2 that then regulates Star-PAP activity toward specific pre-mRNAs [182]. This again highlights the paradigm where PIPKIs define the specificity of PI4,5P2 signaling by associating with PI4,5P2 effectors, in this case PKCδ. The collaborative roles for PIPKIα, PI4,5P2, and PKCδ in Star-PAP control of DNA damage induced expression of the apoptotic gene BIK [182, 195] (Figure 4).

Although the PIPKIα-mediated PI4,5P2 signaling specifically modulates Star-PAP activity, not all Star-PAP targeting mRNAs are regulated by PIPKIα [183, 195, 202]. It is likely that other nuclear speckle targeted PIP kinases such as PIPKIγi4 or nuclear PIPKII isoforms may control additional Star-PAP target mRNAs. This emphasizes the emerging paradigm where the pre-mRNA specificity of Star-PAP is regulated by the assembly or recruitment of different kinase co-activators into the Star-PAP complex [195].

Another example of a PI4,5P2 effector in the nucleus is steroidogenic factor 1 (SF-1), a nuclear receptor. Transcriptional activity of SF-1 is regulated by a direct association with PI4,5P2 [203]. In the solved structure, SF-1 binds PI4,5P2 with the head group exposed to surface and the acyl chains buried deep in the hydrophobic pocket [204, 205]. The exposed head group is further phosphorylated by a nuclear PI3K, inositol polyphosphate multikinase, [205], and an association of SF-1 with PI3,4,5P3 stabilizes its binding to coactivators leading to enhancement of transcription activity of SF-1 [204]. However, whether SF-1 physically or functionally associates with PIP kinases remains untested.

6. PIP kinases integrate with and regulate other phosphoinositide kinases

PI4 kinases generate PI4P, a substrate for PIPKIs, a physical interaction of PIPKIs with PI4 kinases could bestow functional synergism for PI4,5P2 production. An association of type II PI4 kinases (PI4KIIs) with PIPKIs is reported [206]. Following this discovery, ADP-ribosylation factor (ARF) small GTPase was shown to mediate the targeting of PI4KIIβ and an unidentified PIPKI to the Golgi [129]. The PIPKI that is responsible for PI4,5P2 generation at the Golgi is likely PIPKIβ as it directly interacts with ARF1 and this interaction targets PIPKIβ to the Golgi [207]. Additionally, ARF1 enhances kinase activity of PI4KIIβ at the Golgi membranes [207] and a PIPKI isoform, possibly PIPKIβ [8]. Taken together, the organization of PI4 kinases and PIPKIs into multiprotein complexes specifically targeted to the Golgi membrane by ARF is an efficient way to spatiotemporally and efficiently coordinate the synthesis of PI4,5P2. Furthermore, such an assembly may not be confined to the Golgi membrane as PI4 kinases and their targeting factors are also found in most membrane compartments [208, 209].

Class I PI3Ks generate PI3,4,5P3 using PI4,5P2 as substrate. Thus, class I PI3Ks are potential effectors of PI4,5P2 and the compartmentalized organization of PIPKIs and class I PI3Ks might be an efficient means for generating PI3,4,5P3. However, the role of PIPKIs in PI3,4,5P3 generation is underestimated as it had been believed that cellular PI4,5P2 is present beyond the limiting concentration for PI3,4,5P3 synthesis by class I PI3Ks [20]. As discussed above, the enzymatically available concentration of PI4,5P2 at a specific time and location is much lower than estimated, thus de novo synthesis of PI4,5P2 by PIPKIs might be required for efficient PI3,4,5P3 generation by class I PI3Ks. In line with this possibility, in Dictyostelium, depletion of a PIPKI, that is responsible for approximately 90% of cellular PI4,5P2 generation, results in attenuation of Akt activity, a readout of class I PI3K activity in the cell [210]. In human keratinocytes, knockdown of PIPKIα also attenuates extracellular calcium-induced Akt activation [211]. In this particular study, knockdown of PIPKIα reduces approximately 40% of global PI4,5P2 levels in keratinocytes, but the reduction of PI3,4,5P3 levels and Akt activation is much greater (up to approximately 90% reduction) suggesting that PI4,5P2 and PI3,4,5P3 synthesis might be locally organized and that only a specific pool of PI4,5P2 (but not all) is available and responsible for PI3,4,5P3 generation. In support of this possibility, the knockdown of a single PIPKI isoform has no significant impact on global PI4,5P2 levels [46, 50]. The local organization of PI4,5P2 and PI3,4,5P3 synthesis is further supported by immunostaining analyses in migrating leukocytes [36]. Class I PI3Ks localize at the leading edge membranes, whereas PTEN is present at the side and rear of migrating cells [212–214]. This leads to an assumption that PI3,4,5P3 concentration is higher at the leading edges than side and rear, and PI4,5P2 concentration is higher at the side and rear than the leading edges. In contrast to this assumption, PI4,5P2 concentration is also higher at the leading edges of migrating leukocytes when analyzed with a PI4,5P2-specific antibody [36]. Importantly, PIPKIα and PIPKIγ are colocalized with PI3,4,5P3 at the leading edge suggesting that PI4,5P2 synthesis by PIPKIs is coupled to PI3,4,5P3 localization at the leading edges of migrating cell.

PI4 kinases, PIPKIs and class I PI3Ks mediate sequential phosphorylation at the 4, 5 and 3 hydroxyl of the myo-inositol ring of PI, respectively, to generate PI3,4,5P3. Organization of all three enzymes in the same multiprotein complex could more efficiently generate PI3,4,5P3. Knockdown of PI4KIIα or PI4KIIIβ in fibroblast cells reduces global PI4P and PI4,5P2 levels, but only PI4KIIα knockdown reduces EGF-stimulated Akt activation [215] indicating that PI4KIIα-mediated local PI4P and PI4,5P2 generation is required for class I PI3K dependent Akt activation. Also, sequestration of PI4P attenuates downstream signaling of Akt, without affecting other PI4P–mediated signaling, further suggesting that PI4P is important for PI3,4,5P3 generation by class I PI3Ks [216].

7. Concluding remarks

As discussed above, interaction of PIP kinases with PI4,5P2 effectors provides an efficient means to regulate PI4,5P2 signaling at a specific time and location (see Figure 1). Recent advances in proteomic studies have revealed PI4,5P2 interacting protein complexes [13–15]. Interestingly, these studies have identified many phosphoinositide-metabolizing enzymes including PIP kinases along with known PI4,5P2 effectors, suggesting that the linkage of PI4,5P2 signal generation, turnover and usage generally occurs within cells. Further studies are required to elucidate how a specific PI4,5P2 effector is regulated by association with PI4,5P2-metabolizing enzymes. Although, this review focuses on generation of PI4,5P2 by PIP kinases, PI4,5P2 effectors and PIP kinases also associate with PI4,5P2-specific phosphatases [8, 28] providing a means to fine tune PI4,5P2 signaling. In a larger context aberrant PIPn signaling contributes to many human diseases including neurodegenerative diseases, cancers, and cardiovascular diseases [28, 120, 217], understanding the molecular mechanisms underlying PIPn effector signaling regulated by PIPn-metabolizing enzymes will provide new insights and foundations for therapeutic approaches to disease states.

Highlights.

Cellular PI4,5P2 is present in a limiting concentration for PI4,5P2 effector binding.

A number of PI4,5P2 effectors physically associate with PI4,5P2 modifying enzymes.

The PI4,5P2 effector-PIP kinase complexes serve as a functional platform.

Spatiotemporal PI4,5P2 signaling specificity is defined by the complex formation.

Acknowledgements

This work is in part supported by NIH grant CA104708 and GM057549 to R.A.A., American Heart Association Predoctoral Fellowship to S.C, and Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI) International Student Research Fellowship to X.T. Due to space constraints some relevant studies may not have been referenced.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The authors have declared no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Lemmon MA. Membrane recognition by phospholipid-binding domains. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:99–111. doi: 10.1038/nrm2328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stephens LR, Jackson TR, Hawkins PT. Agonist-stimulated synthesis of phosphatidylinositol(3,4,5)-trisphosphate: a new intracellular signalling system? Biochim Biophys Acta. 1993;1179:27–75. doi: 10.1016/0167-4889(93)90072-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson RA, Marchesi VT. Regulation of the association of membrane skeletal protein 4.1 with glycophorin by a polyphosphoinositide. Nature. 1985;318:295–298. doi: 10.1038/318295a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lassing I, Lindberg U. Specific interaction between phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate and profilactin. Nature. 1985;314:472–474. doi: 10.1038/314472a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Suh BC, Hille B. Regulation of ion channels by phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2005;15:370–378. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2005.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McLaughlin S, Murray D. Plasma membrane phosphoinositide organization by protein electrostatics. Nature. 2005;438:605–611. doi: 10.1038/nature04398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heo WD, Inoue T, Park WS, Kim ML, Park BO, Wandless TJ, Meyer T. PI(3,4,5)P3 and PI(4,5)P2 lipids target proteins with polybasic clusters to the plasma membrane. Science. 2006;314:1458–1461. doi: 10.1126/science.1134389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ling K, Schill NJ, Wagoner MP, Sun Y, Anderson RA. Movin’ on up: the role of PtdIns(4,5)P(2) in cell migration. Trends Cell Biol. 2006;16:276–284. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2006.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yin HL, Janmey PA. Phosphoinositide regulation of the actin cytoskeleton. Annu Rev Physiol. 2003;65:761–789. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.65.092101.142517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Downes CP, Gray A, Lucocq JM. Probing phosphoinositide functions in signaling and membrane trafficking. Trends Cell Biol. 2005;15:259–268. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2005.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Choi S, Thapa N, Hedman AC, Li Z, Sacks DB, Anderson RA. IQGAP1 is a novel phosphatidylinositol 4,5 bisphosphate effector in regulation of directional cell migration. EMBO J. 2013;32:2617–2630. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2013.191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barlow CA, Laishram RS, Anderson RA. Nuclear phosphoinositides: a signaling enigma wrapped in a compartmental conundrum. Trends Cell Biol. 2012;20:25–35. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2009.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Catimel B, Schieber C, Condron M, Patsiouras H, Connolly L, Catimel J, Nice EC, Burgess AW, Holmes AB. The PI(3,5)P2 and PI(4,5)P2 interactomes. J Proteome Res. 2008;7:5295–5313. doi: 10.1021/pr800540h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dixon MJ, Gray A, Boisvert FM, Agacan M, Morrice NA, Gourlay R, Leslie NR, Downes CP, Batty IH. A screen for novel phosphoinositide 3-kinase effector proteins. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2011;10 doi: 10.1074/mcp.M110.003178. M110 003178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lewis AE, Sommer L, Arntzen MO, Strahm Y, Morrice NA, Divecha N, D’Santos CS. Identification of nuclear phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate-interacting proteins by neomycin extraction. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2011;10 doi: 10.1074/mcp.M110.003376. M110 003376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Good MC, Zalatan JG, Lim WA. Scaffold proteins: hubs for controlling the flow of cellular information. Science. 2011;332:680–686. doi: 10.1126/science.1198701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rana RS, Hokin LE. Role of phosphoinositides in transmembrane signaling. Physiological reviews. 1990;70:115–164. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1990.70.1.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Anderson RA, Boronenkov IV, Doughman SD, Kunz J, Loijens JC. Phosphatidylinositol phosphate kinases a multifaceted family of signaling enzymes. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:9907–9910. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.15.9907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stephens LR, Hughes KT, Irvine RF. Pathway of phosphatidylinositol(3,4,5)-trisphosphate synthesis in activated neutrophils. Nature. 1991;351:33–39. doi: 10.1038/351033a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Insall RH, Weiner OD. PIP3 PIP2, and cell similar messages different meanings? Dev Cell. 2001;1:743–747. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(01)00086-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sheetz MP, Sable JE, Dobereiner HG. Continuous membrane-cytoskeleton adhesion requires continuous accommodation to lipid and cytoskeleton dynamics. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 2006;35:417–434. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.35.040405.102017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Golebiewska U, Nyako M, Woturski W, Zaitseva I, McLaughlin S. Diffusion coefficient of fluorescent phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate in the plasma membrane of cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19:1663–1669. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-12-1208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kalwa H, Michel T. The MARCKS protein plays a critical role in phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate metabolism and directed cell movement in vascular endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2010;286:2320–2330. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.196022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vaaraniemi J, Palovuori R, Lehto VP, Eskelinen S. Translocation of MARCKS and reorganization of the cytoskeleton by PMA correlates with the ion selectivity, the confluence, and transformation state of kidney epithelial cell lines. J Cell Physiol. 1999;181:83–95. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(199910)181:1<83::AID-JCP9>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Song MS, Salmena L, Pandolfi PP. The functions and regulation of the PTEN tumour suppressor. Nature reviews. Molecular cell biology. 2012;13:283–296. doi: 10.1038/nrm3330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Heck JN, Mellman DL, Ling K, Sun Y, Wagoner MP, Schill NJ, Anderson RA. A conspicuous connection: structure defines function for the phosphatidylinositol-phosphate kinase family. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 2007;42:15–39. doi: 10.1080/10409230601162752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van den Bout I, Divecha N. PIP5K–driven PtdIns(4,5)P2 synthesis: regulation and cellular functions. J Cell Sci. 2009;122:3837–3850. doi: 10.1242/jcs.056127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sasaki T, Takasuga S, Sasaki J, Kofuji S, Eguchi S, Yamazaki M, Suzuki A. Mammalian phosphoinositide kinases and phosphatases. Prog Lipid Res. 2009;48:307–343. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2009.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Loijens JC, Anderson RA. Type I phosphatidylinositol-4-phosphate 5-kinases are distinct members of this novel lipid kinase family. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:32937–32943. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.51.32937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schill NJ, Anderson RA. Two novel phosphatidylinositol-4-phosphate 5-kinase type Igamma splice variants expressed in human cells display distinctive cellular targeting. Biochem J. 2009;422:473–482. doi: 10.1042/BJ20090638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sun Y, Thapa N, Hedman AC, Anderson RA. Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate: targeted production and signaling. Bioessays. 2013;35:513–522. doi: 10.1002/bies.201200171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Varnai P, Balla T. Visualization of phosphoinositides that bind pleckstrin homology domains: calcium- and agonist-induced dynamic changes and relationship to myo-[3H]inositol-labeled phosphoinositide pools. J Cell Biol. 1998;143:501–510. doi: 10.1083/jcb.143.2.501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Watt SA, Kular G, Fleming IN, Downes CP, Lucocq JM. Subcellular localization of phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate using the pleckstrin homology domain of phospholipase C delta1. Biochem J. 2002;363:657–666. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3630657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hammond GR, Schiavo G, Irvine RF. Immunocytochemical techniques reveal multiple distinct cellular pools of PtdIns4P and PtdIns(4,5)P(2) Biochem J. 2009;422:23–35. doi: 10.1042/BJ20090428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rong Y, Liu M, Ma L, Du W, Zhang H, Tian Y, Cao Z, Li Y, Ren H, Zhang C, Li L, Chen S, Xi J, Yu L. Clathrin and phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate regulate autophagic lysosome reformation. Nat Cell Biol. 2012;14:924–934. doi: 10.1038/ncb2557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sharma VP, DesMarais V, Sumners C, Shaw G, Narang A. Immunostaining evidence for PI(4,5)P2 localization at the leading edge of chemoattractant-stimulated HL-60 cells. J Leukoc Biol. 2008;84:440–447. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0907636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ling K, Doughman RL, Firestone AJ, Bunce MW, Anderson RA. Type I gamma phosphatidylinositol phosphate kinase targets and regulates focal adhesions. Nature. 2002;420:89–93. doi: 10.1038/nature01082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thapa N, Sun Y, Schramp M, Choi S, Ling K, Anderson RA. Phosphoinositide signaling regulates the exocyst complex and polarized integrin trafficking in directionally migrating cells. Dev Cell. 2012;22:116–130. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.10.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sun Y, Hedman AC, Tan X, Schill NJ, Anderson RA. Endosomal type Igamma PIP 5-kinase controls EGF receptor lysosomal sorting. Dev Cell. 2013;25:144–155. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hammond GR, Machner MP, Balla T. A novel probe for phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate reveals multiple pools beyond the Golgi. J Cell Biol. 2014;205:113–126. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201312072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Giudici ML, Emson PC, Irvine RF. A novel neuronal-specific splice variant of Type I phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate 5-kinase isoform gamma. Biochem J. 2004;379:489–496. doi: 10.1042/BJ20031394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xia Y, Irvine RF, Giudici ML. Phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate 5-kinase Igamma_v6, a new splice variant found in rodents and humans. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2011;411:416–420. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.06.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Giudici ML, Lee K, Lim R, Irvine RF. The intracellular localisation and mobility of Type Igamma phosphatidylinositol 4P 5-kinase splice variants. FEBS Lett. 2006;580:6933–6937. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.11.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Di Paolo G, Pellegrini L, Letinic K, Cestra G, Zoncu R, Voronov S, Chang S, Guo J, Wenk MR, De Camilli P. Recruitment and regulation of phosphatidylinositol phosphate kinase type 1 gamma by the FERM domain of talin. Nature. 2002;420:85–89. doi: 10.1038/nature01147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bairstow SF, Ling K, Su X, Firestone AJ, Carbonara C, Anderson RA. Type Igamma661 phosphatidylinositol phosphate kinase directly interacts with AP2 and regulates endocytosis. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:20632–20642. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601465200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ling K, Bairstow SF, Carbonara C, Turbin DA, Huntsman DG, Anderson RA. Type I gamma phosphatidylinositol phosphate kinase modulates adherens junction and E-cadherin trafficking via a direct interaction with mu 1B adaptin. J Cell Biol. 2007;176:343–353. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200606023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schill NJ, Hedman AC, Choi S, Anderson RA. Isoform 5 of PIPKIgamma regulates the endosomal trafficking and degradation of E-cadherin. J Cell Sci. 2014;127:2189–2203. doi: 10.1242/jcs.132423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Doughman RL, Firestone AJ, Wojtasiak ML, Bunce MW, Anderson RA. Membrane ruffling requires coordination between type Ialpha phosphatidylinositol phosphate kinase and Rac signaling. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:23036–23045. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211397200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chao WT, Daquinag AC, Ashcroft F, Kunz J. Type I PIPK-alpha regulates directed cell migration by modulating Rac1 plasma membrane targeting and activation. J Cell Biol. 2010;190:247–262. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200911110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mao YS, Yamaga M, Zhu X, Wei Y, Sun HQ, Wang J, Yun M, Wang Y, Di Paolo G, Bennett M, Mellman I, Abrams CS, De Camilli P, Lu CY, Yin HL. Essential and unique roles of PIP5K–gamma and -alpha in Fcgamma receptor-mediated phagocytosis. J Cell Biol. 2009;184:281–296. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200806121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mathis L, Wernimont S, Affentranger S, Huttenlocher A, Niggli V. Determinants of phosphatidylinositol-4-phosphate 5-kinase type Igamma90 uropod location in T-lymphocytes and its role in uropod formation. PeerJ. 2013;1:e131. doi: 10.7717/peerj.131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lokuta MA, Senetar MA, Bennin DA, Nuzzi PA, Chan KT, Ott VL, Huttenlocher A. Type Igamma PIP kinase is a novel uropod component that regulates rear retraction during neutrophil chemotaxis. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18:5069–5080. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-05-0428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lacalle RA, Peregil RM, Albar JP, Merino E, Martinez AC, Merida I, Manes S. Type I phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate 5-kinase controls neutrophil polarity and directional movement. J Cell Biol. 2007;179:1539–1553. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200705044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Di Paolo G, Moskowitz HS, Gipson K, Wenk MR, Voronov S, Obayashi M, Flavell R, Fitzsimonds RM, Ryan TA, De Camilli P. Impaired PtdIns(4,5)P2 synthesis in nerve terminals produces defects in synaptic vesicle trafficking. Nature. 2004;431:415–422. doi: 10.1038/nature02896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang Y, Litvinov RI, Chen X, Bach TL, Lian L, Petrich BG, Monkley SJ, Kanaho Y, Critchley DR, Sasaki T, Birnbaum MJ, Weisel JW, Hartwig J, Abrams CS. Loss of PIP5KIgamma, unlike other PIP5KI isoforms, impairs the integrity of the membrane cytoskeleton in murine megakaryocytes. J Clin Invest. 2008 doi: 10.1172/JCI34239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wang Y, Chen X, Lian L, Tang T, Stalker TJ, Sasaki T, Kanaho Y, Brass LF, Choi JK, Hartwig JH, Abrams CS. Loss of PIP5KIbeta demonstrates that PIP5KI isoform-specific PIP2 synthesis is required for IP3 formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:14064–14069. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804139105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sasaki J, Sasaki T, Yamazaki M, Matsuoka K, Taya C, Shitara H, Takasuga S, Nishio M, Mizuno K, Wada T, Miyazaki H, Watanabe H, Iizuka R, Kubo S, Murata S, Chiba T, Maehama T, Hamada K, Kishimoto H, Frohman MA, Tanaka K, Penninger JM, Yonekawa H, Suzuki A, Kanaho Y. Regulation of anaphylactic responses by phosphatidylinositol phosphate kinase type I {alpha} J Exp Med. 2005;201:859–870. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Volpicelli-Daley LA, Lucast L, Gong LW, Liu L, Sasaki J, Sasaki T, Abrams CS, Kanaho Y, De Camilli P. Phosphatidylinositol-4-phosphate 5-kinases and phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate synthesis in the brain. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:28708–28714. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.132191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kettner A, Kumar L, Anton IM, Sasahara Y, de la Fuente M, Pivniouk VI, Falet H, Hartwig JH, Geha RS. WIP regulates signaling via the high affinity receptor for immunoglobulin E in mast cells. J Exp Med. 2004;199:357–368. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wang Y, Lian L, Golden JA, Morrisey EE, Abrams CS. PIP5KI gamma is required for cardiovascular and neuronal development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:11748–11753. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700019104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ridley AJ. Life at the leading edge. Cell. 2011;145:1012–1022. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Parsons JT, Horwitz AR, Schwartz MA. Cell adhesion: integrating cytoskeletal dynamics and cellular tension. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2010;11:633–643. doi: 10.1038/nrm2957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Petrie RJ, Doyle AD, Yamada KM. Random versus directionally persistent cell migration. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:538–549. doi: 10.1038/nrm2729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Adams RH, Alitalo K. Molecular regulation of angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:464–478. doi: 10.1038/nrm2183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Noritake J, Watanabe T, Sato K, Wang S, Kaibuchi K. IQGAP1: a key regulator of adhesion and migration. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:2085–2092. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Watanabe T, Noritake J, Kaibuchi K. Regulation of microtubules in cell migration. Trends Cell Biol. 2005;15:76–83. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2004.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ridley AJ, Schwartz MA, Burridge K, Firtel RA, Ginsberg MH, Borisy G, Parsons JT, Horwitz AR. Cell migration: integrating signals from front to back. Science. 2003;302:1704–1709. doi: 10.1126/science.1092053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rodriguez OC, Schaefer AW, Mandato CA, Forscher P, Bement WM, Waterman-Storer CM. Conserved microtubule-actin interactions in cell movement and morphogenesis. Nat Cell Biol. 2003;5:599–609. doi: 10.1038/ncb0703-599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hartwig JH, Bokoch GM, Carpenter CL, Janmey PA, Taylor LA, Toker A, Stossel TP. Thrombin receptor ligation and activated Rac uncap actin filament barbed ends through phosphoinositide synthesis in permeabilized human platelets. Cell. 1995;82:643–653. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90036-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Tolias KF, Hartwig JH, Ishihara H, Shibasaki Y, Cantley LC, Carpenter CL. Type Ialpha phosphatidylinositol-4-phosphate 5-kinase mediates Rac-dependent actin assembly. Curr Biol. 2000;10:153–156. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00315-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Shibasaki Y, Ishihara H, Kizuki N, Asano T, Oka Y, Yazaki Y. Massive actin polymerization induced by phosphatidylinositol-4-phosphate 5-kinase in vivo. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:7578–7581. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.12.7578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Golub T, Caroni P. PI(4,5)P2-dependent microdomain assemblies capture microtubules to promote and control leading edge motility. J Cell Biol. 2005;169:151–165. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200407058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Thapa N, Anderson RA. PIP2 signaling, an integrator of cell polarity and vesicle trafficking in directionally migrating cells. Cell Adh Migr. 2013;6:409–412. doi: 10.4161/cam.21192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Pinon P, Parssinen J, Vazquez P, Bachmann M, Rahikainen R, Jacquier MC, Azizi L, Maatta JA, Bastmeyer M, Hytonen VP, Wehrle-Haller B. Talin-bound NPLY motif recruits integrin-signaling adapters to regulate cell spreading and mechanosensing. J Cell Biol. 2014;205:265–281. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201308136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kalli AC, Campbell ID, Sansom MS. Conformational changes in talin on binding to anionic phospholipid membranes facilitate signaling by integrin transmembrane helices. PLoS Comput Biol. 2013;9:e1003316. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Legate KR, Takahashi S, Bonakdar N, Fabry B, Boettiger D, Zent R, Fassler R. Integrin adhesion and force coupling are independently regulated by localized PtdIns(4,5)2 synthesis. EMBO J. 2011;30:4539–4553. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Elliott PR, Goult BT, Kopp PM, Bate N, Grossmann JG, Roberts GC, Critchley DR, Barsukov IL. The Structure of the talin head reveals a novel extended conformation of the FERM domain. Structure. 2010;18:1289–1299. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2010.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Anthis NJ, Wegener KL, Ye F, Kim C, Goult BT, Lowe ED, Vakonakis I, Bate N, Critchley DR, Ginsberg MH, Campbell ID. The structure of an integrin/talin complex reveals the basis of inside-out signal transduction. EMBO J. 2009;28:3623–3632. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Goksoy E, Ma YQ, Wang X, Kong X, Perera D, Plow EF, Qin J. Structural basis for the autoinhibition of talin in regulating integrin activation. Mol Cell. 2008;31:124–133. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kalli AC, Wegener KL, Goult BT, Anthis NJ, Campbell ID, Sansom MS. The structure of the talin/integrin complex at a lipid bilayer: an NMR and MD simulation study. Structure. 2010;18:1280–1288. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2010.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Calderwood DA, Campbell ID, Critchley DR. Talins and kindlins: partners in integrin-mediated adhesion. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2013;14:503–517. doi: 10.1038/nrm3624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]