Abstract

Amino acids play essential roles in both metabolism and the proteome. Many studies have profiled free amino acids (FAAs) or proteins; however, few have connected the measurement of FAA with individual amino acids in the proteome. In this study, we developed a metabolomics method to comprehensively analyze amino acids in different domains, using two examples of different sample types and disease models. We first examined the responses of FAAs and insoluble-proteome amino acids (IPAAs) to the Myc oncogene in Tet21N human neuroblastoma cells. The metabolic and proteomic amino acid profiles were quite different, even under the same Myc-induced transfection, and their combination provided a better understanding of the biological status. In addition, amino acids were measured in 3 domains (FAAs, free and soluble-proteome amino acids (FSPAAs), and IPAAs) to study changes in serum amino acid profiles related to colon cancer. A penalized logistic regression model based on the amino acids from the three domains had better sensitivity and specificity than that from each individual domain. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to perform a combined analysis of amino acids in different domains, and indicates the useful biological information available from a metabolomics analysis of the protein pellet. This study lays the foundation for further quantitative tracking of the distribution of amino acids in different domains, with opportunities for better diagnosis and mechanistic studies of various diseases.

Keywords: metabolomics, amino acid, Myc, colon cancer

1. Introduction

Amino acids play an essential role in biological processes, primarily because they are extensively involved in metabolism and constitute the basic building blocks of peptides and proteins. Amino acids are of increasing interest in the field of metabolomics which aims to establish metabolic responses of living systems to external or internal perturbations.1–8 For example, in the field of cancer metabolism, the Warburg effect9–13 is being re-evaluated due to new findings on the importance of glutamine as an energy source for proliferating cancer cells.10, 14, 15 A recent study found that glycine is an important metabolite for human cancer, since it is also strongly correlated with the rate of cancer cell proliferation.16 Amino acid profiles have been used for cancer detection.17 We recently showed that the recurrence of breast cancer could be predicted 13 months (on average) before clinical diagnosis using metabolic markers that included glutamic acid, histidine, proline, and tyrosine.18 Advanced studies of amino acids may lead to significant discoveries in many research areas including disease diagnosis, drug discovery, and biological sciences, etc.

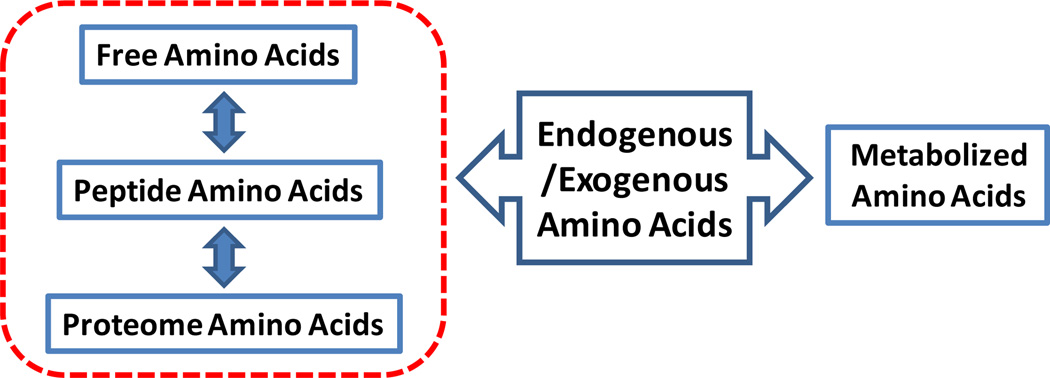

As shown in Fig. 1, endogenous or exogenous amino acids in a biological system are either metabolized or incorporated into three domains that include free amino acids (FAAs), peptide amino acids, and proteome amino acids. In fact, amino acids provide an important connection between metabolism and the proteome, since the free amino acids and those to be incorporated in peptides and proteins are the same; therefore, the distribution of individual amino acids in different domains should be related to the biological status of a living system. However, although metabolomics and proteomics have been combined in previous studies,19, 20 the distribution changes of amino acids in these domains in response to different physiological status have not been investigated, and the integrated analysis of individual amino acids in various domains has not been performed.

Fig. 1.

The distribution of amino acids in a biological system. Endogenous or exogenous amino acids are either metabolized or incorporated into three domains that include free amino acids, peptide amino acids, and proteome amino acids.

In this study, we obtained a “snapshot” of amino acid levels in various domains (as shown schematically within the red dashed line in Fig. 1) and examined their ability to detect altered metabolism in both cancer cells and human serum. We applied the well-established acid hydrolysis method to obtain individual amino acids from peptides and proteins, and used liquid chromatography tandem MS (LC-MS/MS) to measure MS-detectable amino acids. First, we examined the comprehensive responses of amino acids that were due to induction of the N-Myc oncogene in Tet21N human neuroblastoma cells.21–23 Second, we investigated the ability of amino acid analysis to identify patients with colon cancer by measuring amino acids from three domains in their serum. We constructed multivariate statistical models based on the significantly altered levels of amino acids in different domains, both individually and in combination, and showed that their combination led to improved differentiation. This study lays the foundation for further quantitative tracking of the distribution of individual amino acid levels in metabolic, peptide, and proteome profiles, which can provide a new window for studying the results of perturbed metabolism in different domains.

2. Experimental

2.1 Chemicals

The compounds purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) included acetonitrile (LC-MS grade), methanol (LC-MS grade), formic acid (LC-MS grade), chloroform (HPLC grade), and 20 amino acids (reagent grade; Table S1). Hydrochloric acid (HCl) was purchased from EMD Millipore (Billerica, MA). DI water was provided in-house by a Synergy Ultrapure Water System from EMD Millipore (Billerica, MA). Doxycycline was purchased from Clontech Laboratories, Inc. (Mountain View, CA).

2.2 Tet21N Human Neuroblastoma Cells

The cell samples and their preparation were well documented in a study investigating N-Myc-driven tumorigenesis.24 Briefly, Tet21N cells were cultured in DMEM (Gibco, Grand Island, NY; with 10% fetal bovine serum). Doxycycline was used to repress N-Myc expression. Fig. S1 shows the characterization of Myc-On and Myc-Off cells. Tet21N cells express a doxycycline-repressible N-Myc construct which allows for inducible N-Myc expression in the presence/absence of doxycycline (Myc-Off/Myc-On). Ectopic N-Myc is sufficient to induce both hyperproliferation and anchorage-independent growth in soft agar (an indicator of malignant transformation). Comprehensive amino acid profiles (3 replicates for each group) were compared between Myc-Off and Myc-On cells.

2.3 Serum Samples

All serum samples were collected in accordance with the protocols approved by the Indiana University School of Medicine and Purdue University Institutional Review Boards. All subjects in the study provided informed consent according to the institutional guidelines. Patients undergoing colonoscopy for CRC screening were evaluated, and blood samples from the patients were obtained after overnight fasting and bowel preparation prior to colonoscopy. Based on the analysis of biopsied tissue, individuals were categorized as either colon cancer patients or healthy controls. All colon cancer patients in this study were newly diagnosed, and the blood samples were drawn before any surgery, chemotherapy, or radiation treatment. In total, serum samples from 28 colon cancer patients and 28 healthy controls were analyzed. The detailed demographic and clinical information for the patients and healthy controls was shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical information for the patients and healthy controls included in this study.

| Healthy Controls | Colon Cancer | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Subjects | 28 | 28 | |

| Age, median (range) | 58 (18–80) | 56 (29–88) | |

| BMIa, median (range) | 30.0 (21.1–43.2) | 27.5 (17.8–32.2) | |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 14 | 14 | |

| Female | 14 | 14 | |

| Stage | |||

| I | - | 1 | |

| II | - | 2 | |

| III | - | 6 | |

| IV | - | 19 | |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Caucasian | 13 | 15 | |

| African American | 2 | 2 | |

| Hispanic or Latino | 0 | 1 | |

| NA | 13 | 10 | |

13 controls and 9 colon cancer patients do not have BMI data.

2.4 Sample Preparation

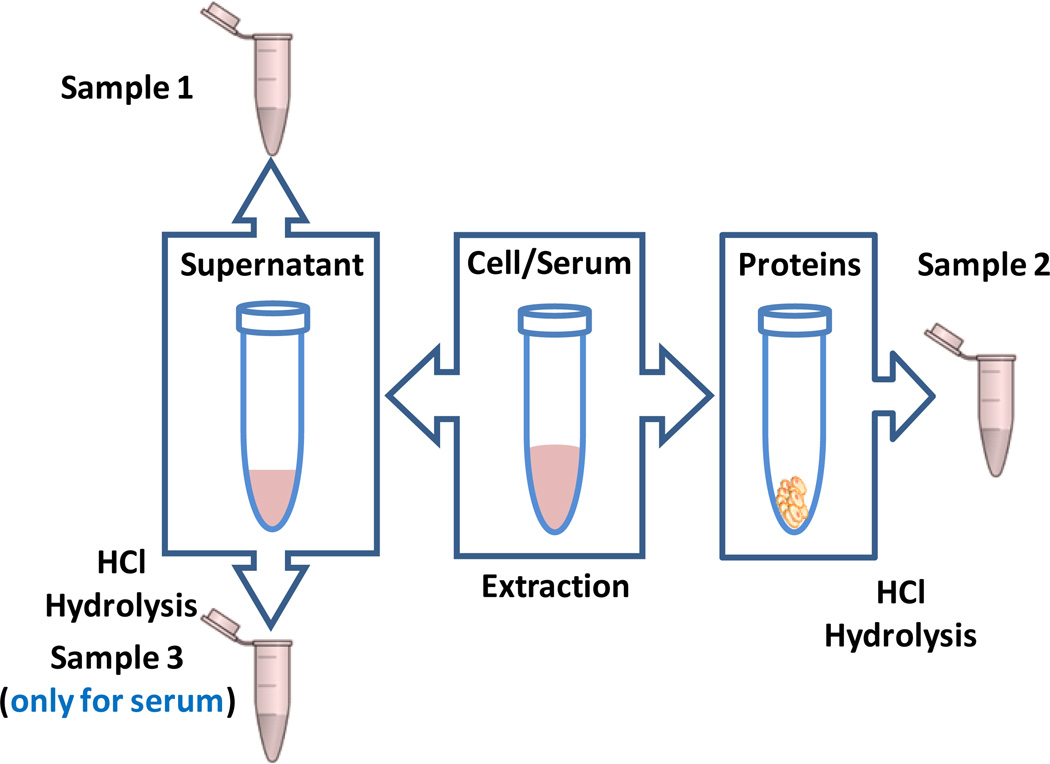

In this study, we obtained 2 amino acid samples from each cell extract for further LC-MS/MS experiments. Fig. 2 illustrates how amino acids were obtained from the two domains using a single cell extract, including portions for measuring FAAs (Sample 1) and insoluble-proteome amino acids (IPAAs, Sample 2). Forty-eight hrs after transfection, 1×106 cells were plated in a 6 well plate (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL). After 24 hrs culture media was aspirated, and cells were washed twice in ice cold H2O and lysed in 1.5 mL of ice cold 9:1 methanol:chloroform, with the plates placed on dry ice (~−75 °C) to quench metabolism. After 5 min, cells were scraped and transferred to 1.5 mL Eppendorf tubes (Hauppauge, NY). Lysates were centrifuged at 20817 rcf for 10 min, and supernatants were transferred to new vials and dried using an Eppendorf Vacufuge (Eppendorf, Hauppauge, NY). The dried supernatant was used as Sample 1 for FAA measurements, after reconstituting in 100 µL DI water. The protein pellet was mixed with 500 µL 6N HCl in a 1.5 mL microtube (Sarstedt Inc., Newton, NC) and baked at 110 °C using a digitally controlled dry bath (Labnet International, Inc., Edison, NJ) for 24 hrs. This sample (Sample 2) was then dried and reconstituted with 1 mL DI water prior to LC-MS/MS analysis. The protein content was evaluated using the BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL).

Fig. 2.

A schematic illustration of sample preparation to obtain amino acids in different domains, including free amino acids, FAAs (Sample 1), insoluble-proteome amino acids, IPAAs (Sample 2), and free and soluble-proteome amino acids, FSPAAs (Sample 3).

As shown in Fig. 2, we obtained 3 amino acid samples from each serum, including FAAs (Sample 1), IPAAs (Sample 2), and free and soluble-proteome amino acids (FSPAAs, Sample 3). We mixed 30 µL serum with 300 µL methanol, and then vortexed the mixture for 10 min. The mixture was incubated at 4 °C for 20 min and then centrifuged at 20817 rcf for 5 min to precipitate the proteins. The supernatant was collected into a new vial. To the protein pellet, we added 660 µL methanol:DI water (10:1, v:v), which was then vortexed for 10 min. After centrifuging at 20817 rcf for 5 min, the supernatant was added to the previous vial. The combined supernatant was dried and then reconstituted in 60 µL DI water. The first half (30 µL) of the sample was mixed with 120 µL DI water and used as Sample 1. The other half (30 µL) of the sample was mixed with 500 µL 6N HCl and baked at 110 °C for 24 hrs. This sample was then dried and reconstituted in 150 µL DI water to obtain Sample 3. In addition, the protein pellet was suspended in 500 µL 6N HCl and incubated at 110 °C for 24 hrs to prepare Sample 2. Sample 2 was then dried and reconstituted in the same manner as that for Sample 3 except that it was diluted 50-fold with DI water. Notably, different volume parameters were used for Sample 1, 2, and 3. In our initial experiments we found that IPAA concentrations in the original cell/serum samples were generally much higher than those of the FAAs and FSPAAs (FSPAAs were a little bit higher than FAAs). Volumes were adjusted to maintain somewhat similar MS intensities.

2.5 LC-MS/MS Measurements

All experiments were performed using an Agilent 1260 LC-6410 Triple Quad MS system (Agilent Technologies, Inc., Santa Clara, CA). The LC separation was carried out on an Agilent Eclipse XDB-C18 (100×3 mm, 1.8 um) column. The flow rate was 0.5 mL/min. Mobile phase A was 0.2% formic acid in H2O, and mobile phase B was 0.2% formic acid in acetonitrile. For each run, the content of mobile phase A was kept constant at 97% for the first 1 min, and then decreased to 10% during the next 4 min. The mobile phase A content was then kept at 10% for 4 min until the end of the gradient (a total of 9 min). The MS spectrometer was operated under the multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) mode using positive (+) ionization. We used 20 amino acid standards to optimize the MRM transitions and to validate their detection. For each amino acid, the transition producing the highest signal was selected. Table S1 (Supplementary Information) shows the optimized MS parameters to measure each amino acid in this study.

2.6 Data Analysis

Agilent MassHunter QQQ Quantitative Analysis software (version B.03.01) was used to extract MS peak areas. The integrated areas and BCA values for cell and serum samples are provided in the Supplementary Information. The integrated areas for the amino acid signals were normalized to the BCA assay values. We further performed principal component analysis (PCA) on the total-spectral-sum normalized cell data using the PLS toolbox (Version 6.2, Eigenvector Research, Inc., Wenatchee, WA) in Matlab (Version 7.0.4, Mathworks, Natick, MA). For the serum data after further normalizing to the quality control samples, similar to previous studies,18, 25–28 we used penalized logistic regression to construct multivariate statistical models based on amino acid levels measured in the three domains, both individually and in combination. The R statistical software (version 2.8.0) was installed with the gplots package for heatmap plotting and the glmpath package for penalized logistic regression calculations.29 Ten-fold cross validation was used for model building. The output of this procedure was a ranked set of markers according to the prediction probability of validation samples (some less important variables could be omitted).30–32 Thereafter, logistic regression was used to build a statistical model based on the selected variables. The verification package installed in R was used to generate receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves, and to calculate the sensitivity, specificity, and the area under ROC curve (AUROC).

3. Results and Discussion

Isoleucine and leucine had the same optimized MS parameters (Table S1), and they could not be base-line separated in the LC separation, so their combined signal was used in the analysis. Glutamine and lysine had different optimized MS parameters (Table S1), but our analytical assay could not differentiate them (they co-eluted and the MS spectrometer has unit mass resolution). We could not obtain good sensitivity or peak shape for cysteine, and therefore it was excluded from the analysis in this study. Therefore, we obtained 17 variables from the LC-MS/MS measurements of the FAA profile (Sample 1), after adding the isoleucine/leucine and glutamine/lysine signals together, respectively. In addition, during HCl hydrolysis tryptophan was completely destroyed, and asparagine was completely hydrolyzed to aspartic acid. Glutamine became glutamic acid, in which case lysine could be separately measured. Thus, we had 15 LC-MS/MS variables from Sample 2 (IPAAs) and Sample 3 (FSPAAs).

3.1 Tet21N Human Neuroblastoma Cells

For quality control (QC) samples, we used a FAA sample and an IPAA sample, and they were run 3 times throughout the experiments. The average coefficient of variation (CV) of the QC FAA measurements was 5.9%. The IPAA QC measurements were also very reproducible, with an average CV of 4.1%. In addition, we examined the variation of each biological group (Myc-Off and Myc-On). The average CV for the FAA measurements (3 replicates for each group) was 5.6%, including both analytical and biological variation. The average CV for the IPAA measurements was 13.6%. Therefore, our LC-MS/MS measurements for both FAAs and IPAAs are relatively reliable for this method development study.

Table 2 shows the P-values for amino acid levels in the two domains when comparing Myc-Off vs Myc-On cells. Interestingly, we found that the profile of FAAs was much more perturbed than that of IPAAs, since in general FAAs had lower P-values. Fourteen out of 17 FAAs had P-values<0.05 when comparing Myc-Off vs Myc-On, while only one of the IPAAs was significantly different (proline with a P-value of 0.021).

Table 2.

The Student's T-Test P-values comparing amino acids of different domains from Tet21N human neuroblastoma cells.

| Myc-Off vs Myc-On | ||

|---|---|---|

| FAAs | IPAAs | |

| tyrosine | 0.00034 | 0.13 |

| arginine | 0.042 | 0.48 |

| phenylalanine | 0.0016 | 0.83 |

| histidine | 0.0038 | 0.11 |

| methionine | 0.0079 | 0.14 |

| isoleucine/leucine | 0.000070 | 0.92 |

| threonine | 0.0041 | 0.68 |

| valine | 0.00081 | 0.25 |

| proline | 0.000010 | 0.021 |

| serine | 0.17 | 0.47 |

| alanine | 0.037 | 0.099 |

| glycine | 0.0089 | 0.64 |

| tryptophan | 0.061 | N/A |

| asparagine | 0.00061 | N/A |

| glutamic acid | 0.00011 | N/A |

| glutamine/lysine | 0.54 | N/A |

| aspartic acid | 0.0023 | N/A |

| glutamic acid/glutamine | N/A | 0.40 |

| lysine | N/A | 0.52 |

| aspartic acid/asparagine | N/A | 0.85 |

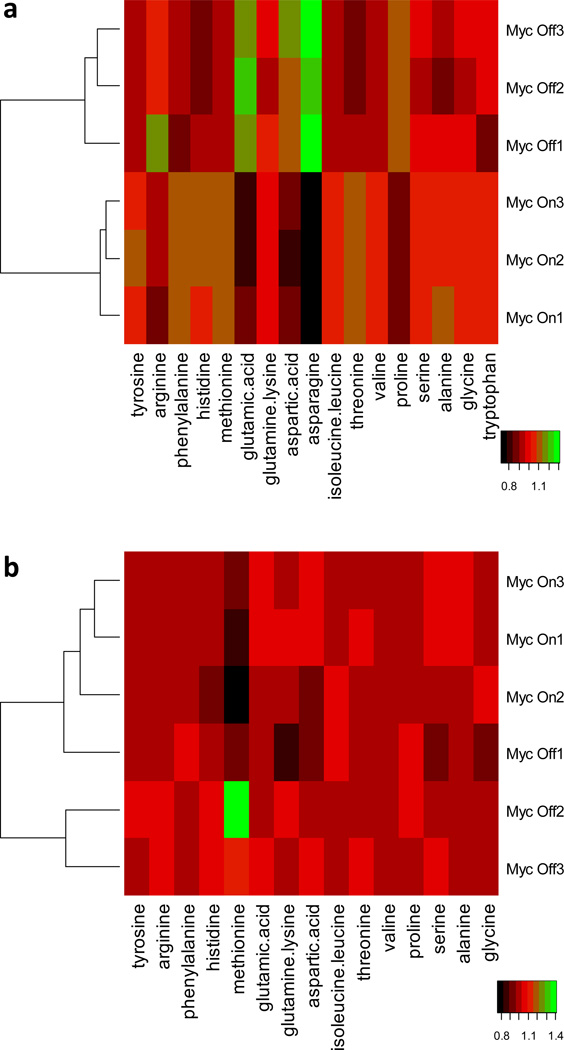

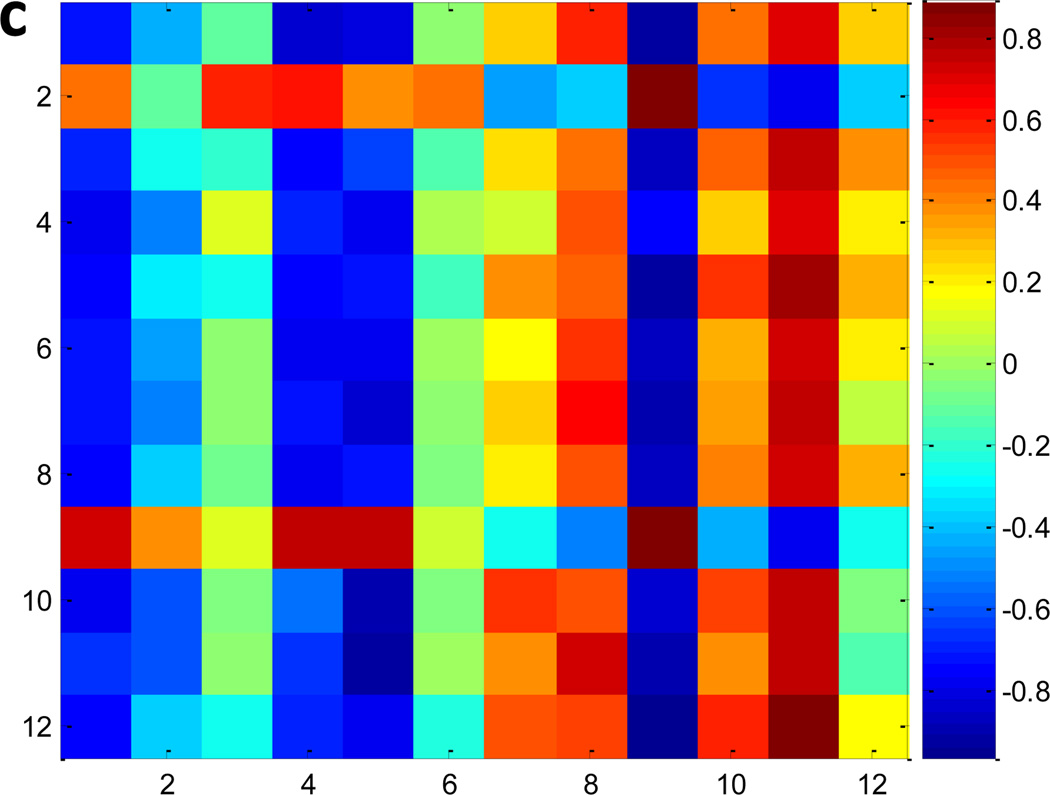

Fig. 3a and 3b show the heatmaps of FAA and IPAA levels, respectively, comparing Myc-On and Myc-Off cells. Consistent with Table 2, FAAs showed larger changes than IPAAs (Fig. 3a vs Fig. 3b). Nevertheless, the two groups were correctly classified in both Fig. 3a and Fig. 3b. This indicates that although individual amino acids in the proteome had relatively large P-values (Table 2), their combination could still successfully reflect Myc-induced variations, which matches well with the fact that global gene and protein expression are significantly altered by Myc.21–23 In Fig. 3c, we examined the Pearson correlation among the 12 amino acids that were detected in both FAAs and IPAAs (glutamic acid, glutamine/lysine, and aspartic acid were not included because of reactions during hydrolysis). Proline (0.89) had the largest positive autocorrelation in FAAs and IPAAs (in Fig. 3c), while methionine had the lowest negative autocorrelation (−0.73). Although a number of correlations were large among different amino acids between FAAs and IPAAs (the highest value is 0.88 between arginine in FAAs and proline in IPAAs), more than half of the FAAs had negative correlations with IPAAs (−0.97 between glycine in FAAs and proline in IPAAs). Our results indicate that metabolic and proteome amino acids in many cases had highly correlated (either positive or negative) responses to Myc.

Fig. 3.

a) The heatmap of 17 FAAs comparing Myc-Off vs Myc-On cells, b) the heatmap of 15 IPAAs comparing Myc-Off vs Myc-On cells, and c) the Pearson correlation among 12 amino acids detected in both FAAs and IPAAs comparing Myc-Off vs Myc-On cells. 1. tyrosine; 2. arginine; 3. phenylalanine; 4. histidine; 5. methionine; 6. isoleucine/leucine; 7. threonine; 8. valine; 9. proline; 10. serine; 11. alanine; 12. glycine.

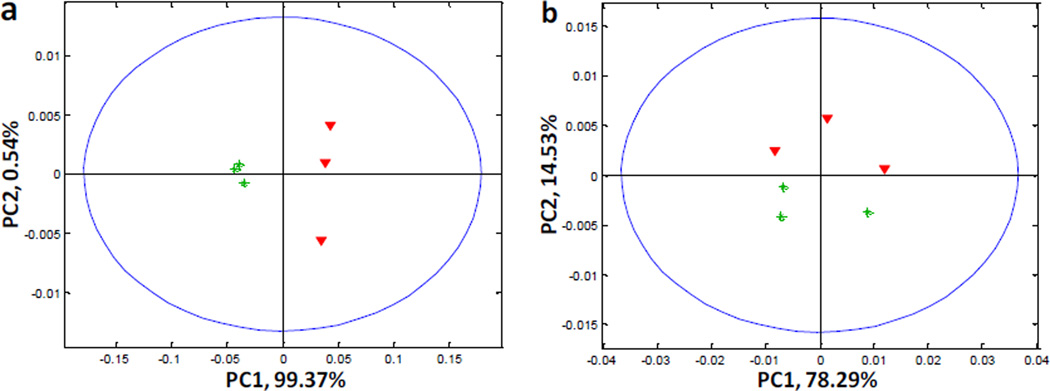

Fig. 4 shows the PCA score plots for different cell groups based on the FAA and IPAA data. Not surprisingly, excellent classification using FAAs was obtained in Fig. 4a, with the PC1 direction carrying 99.37% of the total variation in the data. There was no separation between Myc-On and Off cells along PC1 in Fig. 4b; however, the different cell groups were clearly separated along PC2 direction which carried 14.53% of the total variation. This further proved that, in addition to individual FAAs, different combinations of amino acids in the proteome (i.e., different proteins) could also be an indicator of Myc-induced perturbations. Our results fit well with previous studies demonstrating that the Myc oncogene induces changes in amino acid catabolism,33 and we recently provided additional evidence that Myc together with MondoA (a nutrient-sensing transcription factor that is closely related to Myc regulation) cooperatively regulate metabolism during tumorigenesis in Tet21N cells.24 Our current results, using Tet21N cells expressing high and low levels of Myc show that levels of metabolic and proteome-associated amino acids respond differently to changes in Myc abundance, and examination of both responses may lead to a better understanding of the biological changes.

Fig. 4.

PCA score plots comparing Myc-Off and Myc-On cells using a) FAAs and b) IPAAs. Red triangles: Myc-Off cells; green stars: Myc-On cells.

3.2 Serum Samples

A similar analysis was performed on serum samples from patients with colon cancer and healthy subjects. Table 3 shows the amino acids in the three domains with significant differences (P-values<0.05) when comparing the two groups. As shown in Table 3, there were 10, 9, and 14 amino acids with low P-values (<0.05) in FAAs, FSPAAs, and IPAAs, respectively. Histidine in FAAs had the lowest P-value of 0.00013. Interestingly, glutamic acid/glutamine/lysine, histidine, isoleucine/leucine, threonine, and valine were changed significantly in all the three domains; asparagine/aspartic acid (FAAs and IPAAs), methionine (FAAs and FSPAAs), serine (FASPAAs and IPAAs), and tyrosine (FSPAAs and IPAAs) were altered in two profiles. This indicates that colon cancer not only changes amino acids individually in metabolism, peptides, or proteins, but also affects the amino acid distribution in these domains. Notably, the average CV of the amino acid measurements for 12 injections of the QC sample (4 injections in each of the 3 batches) was 3.7%, ranging from 2.0% (alanine) to 10.4% (tryptophan).

Table 3.

Amino acids in the three domains with P-values<0.05 when comparing colon cancer patients and healthy controls.

| Amino Acid | P-Values |

|---|---|

| FAAs | |

| asparagine | 0.031 |

| aspartic acid | 0.018 |

| glutamic acid | 0.032 |

| glutamine/lysine | 0.0045 |

| histidine | 0.00013 |

| isoleucine/leucine | 0.026 |

| methionine | 0.0050 |

| threonine | 0.042 |

| tryptophan | 0.044 |

| valine | 0.0078 |

| FSPAAs | |

| glutamic acid/glutamine | 0.015 |

| histidine | 0.042 |

| isoleucine/leucine | 0.010 |

| lysine | 0.0017 |

| methionine | 0.036 |

| serine | 0.022 |

| threonine | 0.0041 |

| tyrosine | 0.023 |

| valine | 0.0032 |

| IPAAs | |

| alanine | 0.00099 |

| arginine | 0.00089 |

| aspartic acid/asparagine | 0.0045 |

| glutamic acid/glutamine | 0.0016 |

| glycine | 0.048 |

| histidine | 0.0022 |

| isoleucine/leucine | 0.0013 |

| lysine | 0.00066 |

| phenylalanine | 0.00037 |

| proline | 0.0071 |

| serine | 0.014 |

| threonine | 0.0057 |

| tyrosine | 0.00042 |

| valine | 0.0094 |

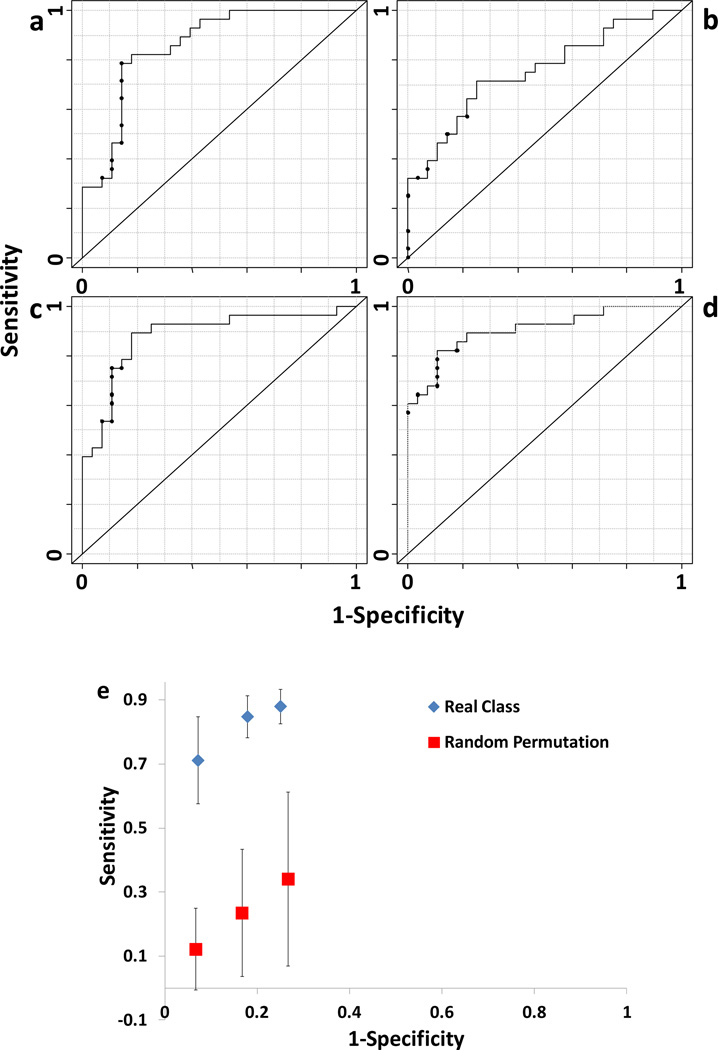

Penalized logistic regression models were then constructed based on the amino acids in Table 3 with low P-values (<0.05). We first examined the performance of amino acids in different domains individually for detecting colon cancer patients. Fig. 5a shows the ROC curve for the logistic regression model using the FAAs. This model had an AUROC of 0.86. The sensitivity was 28% when the specificity was 95%. Penalized logistic regression selected 4 important variables from 10 candidates (FAAs in Table 3), including aspartic acid, glutamic acid, glutamine/lysine, and histidine.

Fig. 5.

The ROC curves of the penalized logistic regression models based on the amino acids with P-values <0.05: a) FAAs, b) FSPAAs, c) IPAAs, and d) the selected amino acids by penalized logistic regression in a)–c). e) MCCV of the penalized logistic regression modeling in a ROC space. True class models, blue diamonds; random permutation models, brown squares.

Similarly, Fig. 5b shows the ROC curve for the penalized logistic regression model based on the FSPAAs in Table 3. An AUROC of 0.75 was obtained, which was less than that (0.86) of Fig. 5a. The sensitivity was 32% (>28% in Fig. 5a) when the specificity was 95%. The selected amino acids from the 9 FSPAAs were lysine and valine. Fig. 5c shows the ROC curve for the penalized logistic regression model based on the 14 IPAAs in Table 3, and the AUROC was determined to be 0.88. The significant amino acids included alanine, arginine, aspartic acid/asparagine, glycine, proline, serine, threonine, tyrosine, and valine. This model (Fig. 5c) had better performance in differentiating colon cancer than those of Fig. 5a and 5b, especially when the specificity was between 80%–100%. For example, the sensitivity was 43% when the specificity was 95%.

Furthermore, we performed penalized logistic regression on all the selected variables from the 3 models above. An AUROC of 0.91 was achieved for the ROC curve in Fig. 5d. In particular, this model had a sensitivity of 65% when the specificity was 95%. The important amino acids selected in Fig. 5d were aspartic acid, glutamic acid, glutamine/lysine, and histidine from FAAs (4 out of 4 variables), lysine from FSPAAs (1 out of 2 variables), and arginine, serine, and tyrosine from IPAAs (3 out of 9 variables). Fig. S2 shows the box-and-whisker plots for the amino acid marker candidates in constructing the model shown in Fig. 5d. Aspartic acid and glutamic acid in FAAs were increased in the colon cancer patients, while the rest of amino acids were decreased. This further confirmed that the distribution of amino acids in the three domains was altered under the biological stress of colon cancer.

To further evaluate the colon cancer-related variation in the data, we used Monte Carlo Cross Validation (MCCV)34, 35 to validate the penalized logistic regression modeling in Fig. 5d. In each iteration (100 in total), all the samples were randomly divided into two sets, 70% as the training set and 30% as the test set. Penalized logistic regression was performed on the training set, and then the resulting model was used to predict the classification of the test set samples. The sample membership could be either correctly assigned, referred as true class, or randomly assigned (permutation). Fig. 5e shows the sensitivities at the specificities of 0.95, 0.85, and 0.75, respectively, for the true class models and permutation models in a ROC space. The true class models were clearly separated from the permutation models, with significantly higher sensitivities. For example, the average sensitivity of true class models was 71% (±14%) at a specificity of 0.95, while it was 12% (±13%) for the permutation models. This result testifies to the fact that amino acids from the three domains in the serum samples contain variations related to colon cancer.

Although biological analysis is beyond the scope of this paper, it is well known that both metabolic and proteomic profiles of amino acids are altered by colorectal cancer (CRC).17, 28, 36, 37 Carcinogenesis of CRC is a complex process involving multiple genetic abnormalities such as mutations in both tumor suppressor genes and oncogenic mediators.38–41 An important consequence of this complex progression could be the altered uptake and usage of amino acids, which have been recognized in metabolomics as putative markers for diagnosing colon cancer.42, 43 Colon cancer also induces a wide range of altered protein synthesis/degradation.44 Stable isotope labeling with amino acids in cell culture (SILAC) is used to study the incorporation of amino acids and degradation of proteins;45–49 however, the analysis of individual amino acids composing proteins/peptides has rarely been combined with those in metabolism. From the present results it is clear that colon cancer changes amino acid levels in both the FSPAA and IPAA domains (Table 3), and thus the amino acid distribution is changed among free amino acids, peptides, and proteins. In addition, the combined analysis of amino acids in the three domains helps improve the diagnostic power of logistic regression modeling to detect colon cancer (Fig. 5). Our study indicates that it is useful to evaluate the network of amino acids in metabolism, peptides, and proteins (Fig. 1) in order to gain a deeper understanding of colon cancer.

While it is valuable to incorporate amino acids in peptides and proteins, our approach does not provide the ability to identify specific proteins/peptides related to Myc or colon cancer. In addition, many amino acids underwent some degree of loss during hydrolysis; therefore, in this semi-quantitative study we prepared the samples using a traditional hydrolysis method (incubation in 6N HCl under 110 °C for 24 hrs). Correction factors can be employed if a precise quantification is desired.50, 51 In principle, stable isotope-resolved metabolomics (SIRM)5, 52 and SILAC45–49 can quantitatively track the distribution of each amino acid in different domains (Fig. 1), although quantitative isotope tracing can be challenging. For our colon cancer study, we measured 168 samples (FAAs, FSPAAs, and IPAAs) from 56 subjects, which limited our ability to perform analyses related to other important factors such as cancer stage. External validation with a separate test set using samples from additional subjects is highly preferred for further validating the statistical models.

4. Conclusions

We introduced the concept of, and developed a new method for, performing a combined analysis of amino acids in three different domains: FAAs, FSPAAs, and IPAAs. We used acid hydrolysis to obtain individual amino acids from peptides and proteins, and LC-MS/MS was utilized to measure the cell and serum samples of different groups. Using Tet21N cells as an example, we showed that the metabolic and proteomic amino acid profiles were different, even under the same stress provided by the N-Myc-oncogene. The combined investigation of metabolic amino acids together with proteome amino acids (for both cell and biofluid samples) provides a more comprehensive view of biological changes, although currently it is rarely performed (e.g., protein pellets are often thrown away in metabolomics studies). It was shown that Myc/colon cancer changed the amino acid profiles and their relative distribution in different domains. Using 13C2-glycine as the tracer, we recently performed a quantitative study, and our results showed that N-Myc was able to change the balance between metabolism and proteome biomass (data not shown). Furthermore, the combined analysis performed here helped improve the sensitivity and specificity of the penalized logistic regression model for detecting colon cancer. This study aims to link metabolism and proteome through the measurement of individual amino acids, and our approach has the potential to bring new insights to the diagnosis and mechanistic understanding of cancer and other diseases.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by the Institute of Translational Health Sciences (ITHS) small pilot grant at the University of Washington (Seattle, WA), the NIH (2R01GM085291 and RO1 CA57138), the Cancer Care Engineering Project at Purdue University (Department of Defense, USAMRMC, W81XWH-08-1-0065 and W81XWH-10-1-0540, Walther Cancer Foundation, Regenstrief Foundation), the Chromosome Metabolism and Cancer Training Grant (T32 CA009657), the Chinese National Instrumentation Program (2011YQ170067), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 21365001). Dr. James B. Hurley in the University of Washington (Seattle, WA) also provided important assistance to the project.

DR serves an executive officer for and holds equity in Matrix-Bio, Inc.

Footnotes

Statement on Potential Conflicts of Interest

The other authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Gu H, Gowda GAN, Raftery D. Future Oncol. 2012;8:1207–1210. doi: 10.2217/fon.12.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gowda GAN, Zhang SC, Gu HW, Asiago V, Shanaiah N, Raftery D. Expert Rev. Mol. Diagn. 2008;8:617–633. doi: 10.1586/14737159.8.5.617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scalbert A, Brennan L, Fiehn O, Hankemeier T, Kristal BS, van Ommen B, Pujos-Guillot E, Verheij E, Wishart D, Wopereis S. Metabolomics. 2009;5:435–458. doi: 10.1007/s11306-009-0168-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nicholson JK, Holmes E, Kinross JM, Darzi AW, Takats Z, Lindon JC. Nature. 2012;491:384–392. doi: 10.1038/nature11708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fan TWM, Lane AN. J. Biomol. NMR. 2011;49:267–280. doi: 10.1007/s10858-011-9484-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reaves ML, Rabinowitz JD. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2011;22:17–25. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2010.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bain JR, Stevens RD, Wenner BR, Ilkayeva O, Muoio DM, Newgard CB. Diabetes. 2009;58:2429–2443. doi: 10.2337/db09-0580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yanes O, Tautenhahn R, Patti GJ, Siuzdak G. Anal. Chem. 2011;83:2152–2161. doi: 10.1021/ac102981k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Warburg O. Science. 1956;123:309–314. doi: 10.1126/science.123.3191.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heiden MGV, Cantley LC, Thompson CB. Science. 2009;324:1029–1033. doi: 10.1126/science.1160809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim J, Dang CV. Cancer Res. 2006;66:8927–8930. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Samudio I, Fiegl M, Andreeff M. Cancer Res. 2009;69:2163–2166. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hockenbery DM. Environ. Mol. Mutag. 2010;51:476–489. doi: 10.1002/em.20552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.DeBerardinis RJ, Mancuso A, Daikhin E, Nissim I, Yudkoff M, Wehrli S, Thompson CB. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007;104:19345–19350. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709747104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wise DR, DeBerardinis RJ, Mancuso A, Sayed N, Zhang XY, Pfeiffer HK, Nissim I, Daikhin E, Yudkoff M, McMahon SB, Thompson CB. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2008;105:18782–18787. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810199105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jain M, Nilsson R, Sharma S, Madhusudhan N, Kitami T, Souza AL, Kafri R, Kirschner MW, Clish CB, Mootha VK. Science. 2012;336:1040–1044. doi: 10.1126/science.1218595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miyagi Y, Higashiyama M, Gochi A, Akaike M, Ishikawa T, Miura T, Saruki N, Bando E, Kimura H, Imamura F, Moriyama M, Ikeda I, Chiba A, Oshita F, Imaizumi A, Yamamoto H, Miyano H, Horimoto K, Tochikubo O, Mitsushima T, Yamakado M, Okamoto N. Plos One. 2011;6:e24143. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Asiago VM, Alvarado LZ, Shanaiah N, Gowda GAN, Owusu-Sarfo K, Ballas RA, Raftery D. Cancer Res. 2010;70:8309–8318. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cai Z, Zhao JS, Li JJ, Peng DN, Wang XY, Chen TL, Qiu YP, Chen PP, Li WJ, Xu LY, Li EM, Tam JPM, Qi RZ, Jia W, Xie D. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 2010;9:2617–2628. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M110.000661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Casado-Vela J, Cebrian A, del Pulgar MTG, Lacal JC. Clin. Transl. Oncol. 2011;13:617–628. doi: 10.1007/s12094-011-0707-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dang CV. Cold Spring Harbor Symp. Quant. Biol. 76:369–374. doi: 10.1101/sqb.2011.76.011296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sloan EJ, Ayer DE. Genes Cancer. 2010;1:587–596. doi: 10.1177/1947601910377489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.O'Shea JM, Ayer DE. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Medicine. 2013;3 doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a014258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carroll PA, Diolaiti D, McFerrin L, Gu H, Djukovic D, Du J, Cheng PF, Anderson S, Ulrich M, Hurley JB, Raftery D, Ayer DE, Eisenman RN. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2014.11.024. Submitted. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leichtle AB, Nuoffer JM, Ceglarek U, Kase J, Conrad T, Witzigmann H, Thiery J, Fiedler GM. Metabolomics. 2012;8:643–653. doi: 10.1007/s11306-011-0357-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ma J, Giovannucci E, Pollak M, Leavitt A, Tao YZ, Gaziano JM, Stampfer MJ. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2004;96:546–553. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nishiumi S, Kobayashi T, Ikeda A, Yoshie T, Kibi M, Izumi Y, Okuno T, Hayashi N, Kawano S, Takenawa T, Azuma T, Yoshida M. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e40459. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Okamoto N, Miyagi Y, Chiba A, Akaike M, Shiozawa M, Imaizumi A, Yamamoto H, Ando T, Yamakado M, Tochikubo O. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2009;1:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Park MY, Hastie T. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B Stat. Methodol. 2007;69:659–677. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen MH, Dey DK. J. Stat. Plan. Inference. 2003;111:37–55. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bursac Z, Gauss CH, Williams DK, Hosmer DW. Source Code Biol. Med. 2008;3:17. doi: 10.1186/1751-0473-3-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kiezun A, Lee I-TA, Shomron N. Bioinformation. 2009;3:311–313. doi: 10.6026/97320630003311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Murphy TA, Dang CV, Young JD. Metab. Eng. 2013;15:206–217. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2012.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rocha CuM, Carrola J, Barros AnS, Gil AM, Goodfellow BJ, Carreira IM, Bernardo Jo, Gomes A, Sousa V, Carvalho L, Duarte IF. J. Proteome Res. 2011;10:4314–4324. doi: 10.1021/pr200550p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wei S, Suryani Y, Gowda GAN, Skill N, Maluccio M, Raftery D. Metabolites. 2012;2:701–716. doi: 10.3390/metabo2040701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.O'Dwyer D, Ralton LD, O'Shea A, Murray GI. Plos One. 2011;6:e27718. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Randhawa H, Chikara S, Gehring D, Yildirim T, Menon J, Reindl KM. BMC Cancer. 2013;13:321. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-13-321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nambiar PR, Gupta RR, Misra V. Mutat. Res.-Fundam. Mol. Mech. Mutag. 2010;693:3–18. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2010.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Markowitz SD, Bertagnolli MM. New Engl. J. Med. 2009;361:2449–2460. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0804588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fearon ER, Vogelstein B. Cell. 1990;61:759–767. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90186-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Noffsinger AE. Annu. Rev. Pathol.-Mech. 2009;4:343–364. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathol.4.110807.092317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tan BB, Qiu YP, Zou X, Chen TL, Xie GX, Cheng Y, Dong TT, Zhao LJ, Feng B, Hu XF, Xu LX, Zhao AH, Zhang MH, Cai GX, Cai SJ, Zhou ZX, Zheng MH, Zhang Y, Jia W. J. Proteome Res. 2013;12:3000–3009. doi: 10.1021/pr400337b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhu J, Djukovic D, Deng L, Gu H, Himmati F, Chiorean EG, Raftery D. J. Proteome Res. 2014;13:4120–4130. doi: 10.1021/pr500494u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Heber D, Byerly LO, Chlebowski RT. Cancer. 1985;55:225–229. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19850101)55:1+<225::aid-cncr2820551304>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ong SE, Blagoev B, Kratchmarova I, Kristensen DB, Steen H, Pandey A, Mann M. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 2002;1:376–386. doi: 10.1074/mcp.m200025-mcp200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mann M. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2006;7:952–958. doi: 10.1038/nrm2067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schmidt F, Strozynski M, Salus SS, Nilsen H, Thiede B. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2007;21:3919–3926. doi: 10.1002/rcm.3290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pratt JM, Petty J, Riba-Garcia I, Robertson DHL, Gaskell SJ, Oliver SG, Beynon RJ. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 2002;1:579–591. doi: 10.1074/mcp.m200046-mcp200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Marimuthu A, Subbannayya Y, Sahasrabuddhe NA, Balakrishnan L, Syed N, Sekhar NR, Katte TV, Pinto SM, Srikanth SM, Kumar P, Pawar H, Kashyap MK, Maharudraiah J, Ashktorab H, Smoot DT, Ramaswamy G, Kumar RV, Cheng YL, Meltzer SJ, Roa JC, Chaerkady R, Prasad TSK, Harsha HC, Chatterjee A, Pandey A. Proteomics Clin. Appl. 2013;7:355–366. doi: 10.1002/prca.201200069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fountoulakis M, Lahm HW. J. Chromatogr. A. 1998;826:109–134. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(98)00721-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Robel EJ, Cranea AB. Anal. Biochem. 1972;48:233–246. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(72)90186-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lane AN, Fan TWM, Bousamra M, Higashi RM, Yan J, Miller DM. OMICS: J. Integrative Biol. 2011;15:173–182. doi: 10.1089/omi.2010.0088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.