Abstract

Polyphosphoinositides (PPIn) are an important family of phospholipids located on the cytoplasmic leaflet of eukaryotic cell membranes. Collectively, they are critical for the regulation many aspects of membrane homeostasis and signaling, with notable relevance to human physiology and disease. This regulation is achieved through the selective interaction of these lipids with hundreds of cellular proteins, and thus the capability to study these localized interactions is crucial to understanding their functions. In this review, we discuss current knowledge of the principle types of PPIn-protein interactions, focusing on specific lipid-binding domains. We then discuss how these domains have been re-tasked by biologists as molecular probes for these lipids in living cells. Finally, we describe how the knowledge gained with these probes, when combined with other techniques, has led to the current view of the lipids’ localization and function in eukaryotes, focusing mainly on animal cells.

Keywords: Phosphoinositides, PH-domain, PX-domain, phospholipase C, fluorescence imaging, membrane

Inositol containing phospholipids have played a fundamental role in eukaryotic evolution (see the review by Michell in this issue). Most of their biology focuses on phosphorylation of the inositol head group in phosphatidylinositol (PtdIns), which yields a family of seven polyphosphoinositides (PPIn; we use the nomenclature proposed by Michell [1]; see figure 1). These PPIn regulate a truly impressive number of eukaryotic functions – as can be gleaned from the other articles present in this volume, and as recently comprehensively reviewed [2]. How can a family of chemically simple phospholipids control such an impressive array of biological functions? The answer in all cases lies in their ability to interact with and thereby regulate proteins. Details of specific protein interactions and their functions are best left in their biological context as described in detail in the accompanying reviews. Rather, our goal in this review are threefold: (i) to outline the general principles of PPIn-protein interactions, (ii) to discuss how lipid binding proteins can be used as biosensors to study PPIn localization and dynamics in living cells and finally (iii) to provide an overview on the current state-of-the-art with regards our knowledge of the lipids’ cellular distribution.

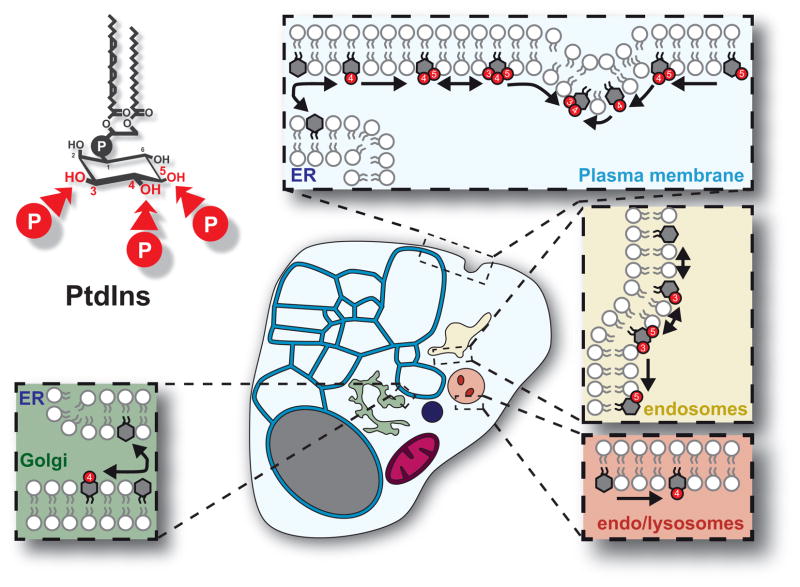

Figure 1. PPIn and their cellular distribution.

The structure of phosphatidylinositol (PtdIns) is shown with the hydroxyls 3–5 available for reversible phosphorylation indicated. The cartoon shows a generic mammalian cell with the major PPIn conversion reactions indicated in their native membranes. Note that PtdIns synthesis occurs in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), from whence it is known to be transferred to the plasma membrane or Golgi as depicted.

General Principles of PPIn-protein interactions

A break-through in understanding how PPIn execute their biological functions came with the discovery of high affinity PtdIns(4,5)P2 binding by the isolated Pleckstrin Homology (PH) domain from phospholipase C delta [3,4]. This example was rapidly followed by the discovery of other PH domains with high affinity but diverse PPIn-binding selectivities [5], as well as by the identification of other PPIn-binding domains such as the FERM [6,7], FYVE [8–10], PX [11–13], ENTH/ANTH [14,15], PROPPIN [16] and the recently described TRAF [17] domains. These observations together revealed the first and canonical principle of PPIn-protein interactions (Figure 2): that high-affinity PPIn binding by conserved families of lipid binding domains drives membrane recruitment of proteins, thereby regulating protein activity in time and space [5].

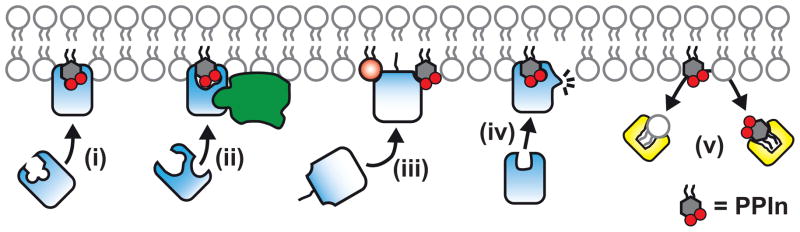

Figure 2. Five functional principles underlying PPIn-regulated protein function.

(i) high affinity binding between protein and PPIn drives membrane binding (ii) co-incident binding between a protein, PPIn and a tertiary determinant (in this case a small G-protein, but it may also be a physical determinant such as membrane curvature) provide the avidity necessary for membrane binding. (iii) Polyvalent clustering of PPIn through non-specific electrostatic interactions with the polybasic region of a amphilic peptide motif contributes to membrane tragetting at anionic lipid-rich membrane (iv) binding of PPIn induces a conformational change in a binding protein. (v) PPIn interaction with a transfer protein facilitates lipid transfer.

This first principle remains fundamentally important for understanding PPIn function. Indeed, high-affinity binding of PtdIns3P appears to be a shared function of every PX domain found in Saccharomyces cerevisiae [18]. However, this general principle is not universal; for example, the PH domain family counts relatively few members that exhibit selective and high affinity PPIn binding [19]. Instead, most members of this large family are now thought to be more general scaffold modules, regulating diverse inter-molecular interactions [20]. Although many PH domains exhibit some binding to PPIn, more often than not the affinity is too low to dictate protein localization [19]. Does this make PPIn binding irrelevant? Probably not, as illustrated by the PH domains found in the cytohesin family of ARF guanine nucleotide exchange factors. Cytohesins come in two splice variants: a “2G” variant that exhibits high-affinity binding to PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 that can direct protein localization [21–23]; and a second, “3G” splice variant with an additional glycine residue that expands the lipid binding pocket in the PH domain, reducing both specificity and affinity [21,24] to such an extent that PPIn binding cannot drive membrane localization [25]. Instead, additional protein-protein interactions between the cytohesin PH domains and Arf/Arl family GTPases have been discovered, which cooperate with PPIn binding to target the cytohesins to membranes [26–28].

This illustrates a second principle of PPIn-protein interactions, one that is an extension of the first: PPIn binding by specific domains can add the necessary avidity to a second interaction that together drive membrane binding (Figure 2). This principle has also been coined “co-incidence detection” [29], and is widely used. For example, interaction between PX domains and PPIn combined with membrane curvature sensing by BAR domains is a central mechanisms by which sorting nexins separate and route different cargos in the endocytic pathway [30]. This combinatorial approach whereby multiple protein or lipid ligands as well as physical constraints such as membrane curvature can direct protein function is a powerful and adaptable one, but can also generate significant caveats when trying to interpret the role of PPIn binding in protein localization, as we will see in the next section.

Note that recruitment of cellular proteins to cell membranes through PPIn binding is not a unique feature of eukaryotic cells; many bacterial pathogens contain protein binding domains that target their host cell’s membrane compartments using PPIn interactions (see the review by Cossart in this issue). These include a family of PtdIns4P-binding proteins in Legionella pneumophila [31,32] and a unique and widely distributed bacterial PPIn binding domain (BPD) found in many type III secretion system-containing bacterial pathogens [33].

There is also a third general principle whereby PPIn contribute to membrane targeting, albeit in a less specific manner. Many proteins contain polybasic domains, which when coupled to some hydrophobic character (for example, bulky hydrophobic residues or lipid modifications), selectively partition onto the plasma membrane [34]. Membrane binding depends on electrostatic interactions with anionic lipids that are enriched on the inner leaflet of the plasma membrane [34,35], principally phosphatidylserine (PtdSer) [35,36]. However, PtdSer enrichment at the plasma membrane alone is not sufficient for localization of polybasic domains, which require the presence of PPIn, mainly PtdIns(4,5)P2 and PtdIns4P [37,38]. This observation is reflected by the capacity of polybasic domains to sequester PtdIns(4,5)P2 molecules in the plane of a PtdSer-rich membrane in vitro [39]. Therefore, it appears that PPIn satisfy a polyanionic lipid requirement for polybasic domain binding in the unique electrostatic environment of the plasma membrane. Interestingly, in addition to unstructured polybasic domain containing proteins, the Kinase-Associated-1 (KA-1) domain family has recently been demonstrated to exploit a similar electrostatic lipid binding mechanism to specifically target the plasma membrane [38,40].

Aside from simple membrane binding, PPIn can also assist in direct conformational activation of proteins. Association of PPIn ligands with the PH domains from PKB [41], Arf GAPs [42,43] and the Arf GEF Brag2 [44] activate the proteins independently from effects on membrane targeting. Conformational activation is also the mechanistic principle by which many integral membrane channels and transporters are regulated by PPIn [45]. Indeed, recent structural studies have revealed how PtdIns(4,5)P2-binding at the interface between the transmembrane and cytosolic domains contributes to opening of the cytosolic pores of two types of voltage gated inwardly rectifying potassium channels [46,47].

Finally, recent work has produced compelling evidence for binding of both the hydrophilic head along with the acyl tails of PPIn to lipid transfer domains, facilitating non-vesicular transfer of these molecules between membranes [48–50]. If coupled to PPIn phosphorylation and de-phosphorylation reactions nestled on separate membranes between which the lipid species is transferred, a chemical gradient may be established; this has been proposed to provide the energy for an antiporter mechanism that drives non-vesicular transport of other lipids [50]. Whilst this exciting idea has not yet been firmly established, with alternative scenarios involving lipid sensing rather than transfer [51], it seems at least possible that this mechanism represents a newly discovered principle by which PPIn control cellular activity [52].

In summary, at present we can identify five functional principles by which PPIn regulate their binding proteins (see Figure 2): (i) direct recruitment of a protein to a membrane by high affinity stoichiometric binding. (ii) “Co-incidence detection” whereby PPIn cooperate with other molecular interactions to specify the membrane location where recruitment occurs. (iii) Simple electrostatic interaction with a protein in the context of a general anionic lipid environment. (iv) Allosteric activation induced by binding and finally (v) through interactions with lipid transfer proteins to facilitate non-vesicular lipid transport. Through these five functional principles, the PPIn can control protein activity in space (by directing protein activity on specific membranes) and time (through modulation of PPIn levels in these membranes). It follows that to fully appreciate the regulation of cellular physiology by these lipids requires an understanding of their dynamic distribution in cells. We therefore next turn to how PPIn-protein interactions can be utilized as experimental tools to address this precise issue.

PPIn binding proteins as biosensors - PPIn localization

Specific, high-affinity binding of PPIn by isolated domains with 1:1 stoichiometry is a molecular talent poised for exploitation, since these domains can be cloned, engineered and re-tasked as biosensors for detecting PPIn. Purified recombinant proteins have been used successfully by many groups to probe for PPIn in fixed cells by both fluorescence and electron microscopy. These have included probes against PtdIns(4,5)P2 [53–56], PtdIns(3,4)P2 [57], PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 [58], PtdIns5P [59] and PtdIns3P [60]. Such approaches often provide quantitative data, especially when validated against biochemical measurements of lipid amounts [38,53,57,58,61] or appropriate standard curves [54]. However, the preservation of lipids and membranes for fluorescence or electron microscopy is a tricky business (see the respective discussions of each in [55] and [53]). Thus a considerable amount of empirical determination is required to ensure the detected signals represent a pool of PPIn present in its native compartment, which must remain reasonably intact despite fixation and the rendering internal membranes accessible to externally applied probes via permeabilization or mechanical disruption. These requirements obviously preclude interrogation of the dynamic distribution of the lipids in living cells.

An alternative-and indeed, pioneering approach [62,63]-to using PPIn binding domains as biosensors was through their fusion to fluorescent proteins; these can be ectopically expressed in cells or even whole organisms, typically exhibiting a diffuse cytosolic/nuclear distribution, but with marked enrichment on specific membrane compartment(s) (e.g. Figure 3). For a high quality biosensor, the membrane enrichment will depend on the presence of a specific PPIn species and only on that species. The sensor will thus report on dynamic changes of the PPIn concentration in this and any other compartment, to an extent that depends on the domain’s binding affinity. Thus fluorescent lipid biosensors have the capacity to reveal the dynamic distribution of PPIn pools in living cells in real time at the resolution limit dictated by the microscope. The downside, as recognized early on in the use of these probes [64], is that rarely if ever are all the criteria met for a specific and unbiased probe; it is always important to be aware of confounds that impact PPIn biosensor behavior, as we will discuss below.

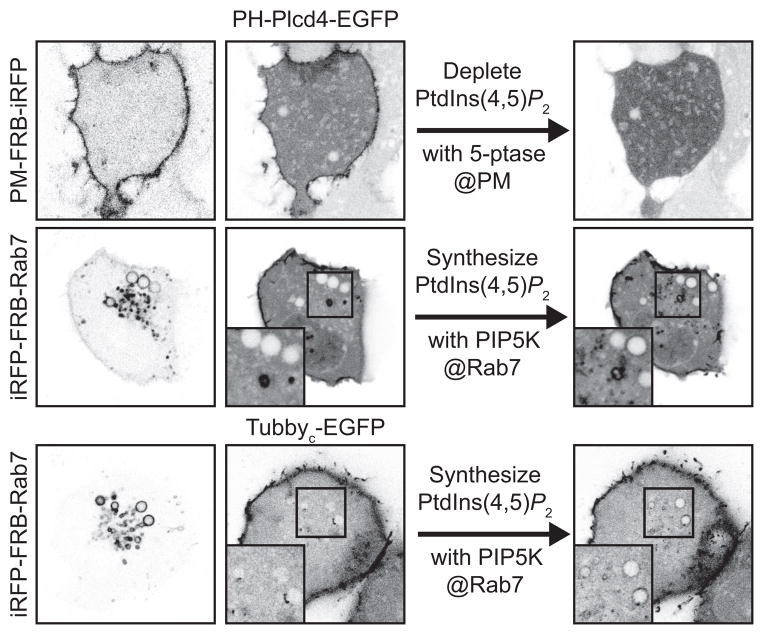

Figure 3. specificity of two PtdIns(4,5)P2 biosensors in cells.

Depletion of PtdIns(4,5)P2 at the PM causes release of Plcd4-PH-GFP, showing the dependence on this lipid for probe localization. Alternatively, driving ectopic synthesis of PtdIns(4,5)P2 at Rab7-labelled membranes is sufficient to recruit the PtdIns(4,5)P2 biosensors PH-Plcd4-GFP and Tubbyc-GFP. The indicated biosensors fused to GFP were expressed in COS-7 cells with either an FRB-PM motif (N-terminal peptide from Lyn kinase) and FKBP fused to the INPP5E 5-phosphatase, or an FRB-fused Rab7 and an FKBP-fused PIP5K. Addition of rapamycin induced dimerization of FRB and FKBP, leading to recruitment of the enzyme to the labelled compartment and depletion or synthesis of PtdIns(4,5)P2, respectively. Insets show enlarged view of the boxed region.

Table 1 lists the seven PPIn species, some of the commonly used probes to image them and the cellular localization revealed by each probe. We also list three crucial criteria that we believe should be taken into account when interpreting data from each probe: Is the biosensor specific for the target PPIn? Is its localization in cells dependent on this PPIn? And if is dependent on that PPIn, is the lipid alone sufficient to drive localization? As can be seen from even a cursory glance of the table, very few biosensors satisfy all three of these criteria. However, all have their merit and have yielded useful data even when their individual caveats are taken into account.

Table 1. PPIn biosensors and their properties.

The seven PPIn, along with some of the more commonly used biosensors that are expressed as fusions with fluorescent-proteins.

| PPIn | Biosensor | localization | Kd | PPIn specific? | PPIn dependent? | PPIn sufficient? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PtdIns3P | FYVE-Hrsx2 | EE | 2.5 μM [159](monomer) |

[8,9] [8,9] |

[60] [60] |

? |

| FYVE-EEA1 | EE | 45 nM [160] |

[8,9] [8,9] |

[8,9] [8,9] |

? | |

| PX-p40phox | EE | 5 μM (diC4-PtdIns3P) [161] |

[11,12] [11,12] |

[11,12] [11,12] |

? | |

|

| ||||||

| PtdIns(3,5)P2 | ML1-Nx2 | LE | ? |

[83] [83] |

? | ? |

|

| ||||||

| PtdIns4P | PH-OSBP | Golgi/PM* | 3.5 μM [71] |

Binds PtdIns(4,5)P2 [71] Binds PtdIns(4,5)P2 [71] |

[72,76,77] [72,76,77] |

Golgi (Arf1-dependent) [72, 71,75

76] Golgi (Arf1-dependent) [72, 71,75

76] PM [75,78] PM [75,78] |

| PH-FAPP1 | Golgi | 18.6 μM [71] |

Binds PtdIns(4,5)P2 [71] Binds PtdIns(4,5)P2 [71] |

[72,76,77] [72,76,77] |

Arf1-dependent [71,75,77] Arf1-dependent [71,75,77] |

|

| PH-Osh2×2 | PM | ? |

Binds PtdIns(4,5)P2 [72] Binds PtdIns(4,5)P2 [72] |

Binds PtdIns(4,5)P2 [38,79] Binds PtdIns(4,5)P2 [38,79] |

Cannot detect Golgi-PtdIns4P [72] Cannot detect Golgi-PtdIns4P [72] |

|

| P4M-SidM | Golgi/PM/LE | ~ 1μM (1/50 full length SidM at 18.2 nM) [32,81] |

[32] [32] |

[82] [82] |

[82] [82] |

|

|

| ||||||

| PtdIns(4,5)P2 | PH-PLCD1 | PM | 2 μM [3,4,96] |

Binds Ins(1,4,5)P3 [3,4,96] Binds Ins(1,4,5)P3 [3,4,96] |

[162,163] [162,163] |

[82] [82] |

| PH-Plcd4 | PM | ? but > PH-PLCD1 [164] |

Binds Ins(1,4,5)P3 [164] Binds Ins(1,4,5)P3 [164] |

Fig. 4

Fig. 4

|

Fig. 3

Fig. 3

|

|

| Tubbyc | PM | ? |

Binds PtdIns(3,4)P2/PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 [66] Binds PtdIns(3,4)P2/PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 [66] |

[87] [87] |

Fig. 3

Fig. 3

|

|

| ENTH/ANTH | PM | 5 μM [14,15] |

[14,15] [14,15] |

[98] [98] |

? | |

|

| ||||||

| PtdIns5P | PHD-Ing2×3 | Nucleus/PM* | ? |

Binds PtdIns3P [68] Binds PtdIns3P [68] |

[68] [68] |

PM [68] ? nucleus [68] PM [68] ? nucleus [68] |

|

| ||||||

| PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 | PH-Akt | PM* | 590 nM [165] |

Binds PtdIns(3,4)P2 and InsP4 [165,166] Binds PtdIns(3,4)P2 and InsP4 [165,166] |

[167–169] [167–169] |

? |

| PH-Btk | PM* | 80 nM [165] |

Binds Ins(1,3,4,5)P4 [89,165,170,171] Binds Ins(1,3,4,5)P4 [89,165,170,171] |

[165,172] [165,172] |

? | |

| GRP1-PH | PM* | 170 nM [165] |

Binds Ins(1,3,4,5)P4 [22,165] Binds Ins(1,3,4,5)P4 [22,165] |

[22,65] [22,65] |

Requires Arf/Arl [26–28] Requires Arf/Arl [26–28] |

|

|

| ||||||

| PtdIns(3,4)P2 | TAPP1-PH-CT | PM* | 80 nM [165] |

[174] [174] |

[147] [147] |

[147] [147] |

Localization: EE (Early endosome), LE (late endo/lysosomes), PM (plasma membrane) and * denotes a localization viewed after stimulation of lipid synthesis. The dissociation constant Kd is reported as binding to the PPIn in a membrane unless indicated. Satisfaction of three criteria that define the specificity of the biosensors is denoted by

and failure to do so by

and failure to do so by

-see text for details.

-see text for details.

The first criteria (binding specificity) has typically been the gold standard when assessing the suitability of probes, and is usually determined by in vitro experiments. These in vitro assays have their own host of caveats that are beyond the scope of this review (see an excellent discussion in [65]); in short, different assays can yield different results, and are rarely definitive in isolation. A battery of different assays yielding congruent data is usually required to gain confidence that the true specificity has been determined. Even so, many biosensors that fail under this criteria have still been extremely useful and selective probes. For example, the PtdIns(4,5)P2 biosensor derived from the Tubby c-terminal domain shows no selectivity for this PPIn over PtdIns(3,4)P2 and PtdIns(3,4,5)P2 [66]. However, the ≥ 20 fold excess of PtdIns(4,5)P2 over these other lipids in cells [67] means that PtdIns(4,5)P2 is the only lipid at sufficient concentration to drive localization of the probe (Table 1). Likewise, a biosensor based on three tandem repeats of the Ing2 PHD domain recognizes both PtdIns3P and PtdIns5P in vitro. However, the probe does not detect cellular PtdIns3P pools, and can detect PtdIns5P synthesis in the plasma membrane [68]. Unfortunately, the affinity of this biosensor seems insufficient to detect the scant endogenous PtdIns5P levels.

A frequent impediment to specificity is binding of PH domains to the equivalent soluble inositol phosphate as forms the hydrophilic “head” of the phospholipid. This is only a concern when these inositol phosphates accumulate at sufficient concentration to compete with the lipid (which can be a serious issue in the case of Ins(1,4,5)P3, as we will discuss later). Furthermore, additional membrane binding interactions often favor lipid binding over soluble inositol phosphates in the physiological environment [69,70].

In our view, these examples demonstrate the equal importance of the second two criteria that address behavior in cells. The dependence on PPIn binding is readily assessed in most cases by inducing acute depletion of the lipid and determining whether the probe’s localization is lost; sufficiency can then be assessed by ectopically driving lipid synthesis and determining whether the probe detects this ectopic synthesis. For example, Figure 3 shows that depletion of PtdIns(4,5)P2 from the plasma membrane by chemically-induced recruitment of a 5-phosphatase (see the detailed discussion on these inducible tools by De Camilli and Idevall-Hagren) causes depletion of the biosensors PH-Plcd4, demonstrating dependence on this lipid for membrane localization in live cells. Although a crucial control, this doesn’t exclude the possibility that another factor assists in membrane targeting (i.e. it is a “co-incidence detector”), biasing the probes towards reporting on PtdIns(4,5)P2 only at the plasma membrane. However, Figure 3 also reveals that induction of ectopic PtdIns(4,5)P2 synthesis at late endosomes is sufficient to the probe, arguing strongly that PtdIns(4,5)P2 alone is sufficient to target the biosensor.

The importance of considering whether a particular PPIn is sufficient as well as necessary to explain localization of a PPIn biosensor is well illustrated by the large family of PtdIns4P biosensors (Table 1). The first two biosensors, those derived from the PH domains of OSBP and FAPP1, display no particular preference for PtdIns4P over PtdIns(4,5)P2 in most, but not all, in vitro assays [71–74]. Nevertheless, when expressed as fluorescent protein fusions in cells both probes label Golgi membranes in a PtdIns4P-dependent fashion; maneuvers that cause selective depletion of PtdIns4P from this compartment release the biosensors from the membrane [71,75,76]. It is easy to interpret these data as indicative that the probes are not influenced by PtdIns(4,5)P2 binding in cells, and that the Golgi localization reflects the unique compartmental accumulation of PtdIns4P. However, it is clear that these probes utilize the co-incidence detection mechanism, and targeting also depends on the presence of Arf1 [71,75,77]. Therefore, the distinct Golgi localization reflects a unique accumulation of both molecular species (Arf1 and PtdIns4P) at these membranes. Indeed, albeit with a less pronounced accumulation, the OSBP PH domain also labels the plasma membrane in a PtdIns4P-dependent and PtdIns(4,5)P2-independent manner [75,78].

An attempt to circumvent this biased detection of Golgi-localized PtdIns4P pools led Roy et al to examine binding sites for potential non-lipid ligands in PH domains, allowing them to identify the S. cerevisiae Osh2p PH domain as a PtdIns4P binder that did not depend on an additional protein ligand for membrane targeting [72]. Although like its OSBP and FAPP1-derived predecessors, this domain exhibits PtdIns(4,5)P2 binding in vitro, it was shown to depend only on PtdIns4P to bind to membranes in yeast cells, and crucially to detect both plasma membrane and Golgi pools of this lipid [72]. When expressed in mammalian cells as a tandem dimer of two identical PH domains (to increase avidity), this probe selectively labels the plasma membrane, co-dependent on the presence of PtdIns4P and PtdIns(4,5)P2 [38,72,79]. It failure to detect PtdIns4P in the Golgi, combined with the capacity of PtdIns(4,5)P2 alone to suffice for plasma membrane localization [38] led us to conclude that it fails under all three criteria as a PtdIns4P biosensor (Table 1). On the other hand, we stress that the probe works well in yeast (perhaps owing to this organism’s lower relative PtdIns(4,5)P2 accumulation), and the conclusion that the large PtdIns4P accumulation in sac1 null cells is at the plasma membrane is certainly valid [80].

Recently, we have investigated the capacity of the high-affinity PtdIns4P binding domain from SidM (P4M) for its capacity as a biosensor for this lipid. P4M exhibits excellent specificity and affinity for PtdIns4P in a variety of in vitro assays [32,81], satisfying our first criterion (Table 1). The probe labels several compartments including the plasma membrane, Golgi and endo-lysosomal network [82], which in all three cases release the probe after acute depletion of PtdIns4P with a Sac phosphatase (second criteria). Crucially, however, induction of ectopic PtdIns4P synthesis on ER-derived membrane via a Hepatitis C virus non-structural protein 5A/PI4KA complex is sufficient to recruit the probe, satisfying our third criteria (Table 1). This gave us the confidence to conclude that P4M reveals the major steady-state pools of PtdIns4P in a typical mammalian cell [82], a feat not achieved by any of the contemporary biosensors.

Efforts to create a PtdIns(3,5)P2 biosensor have been frustrated. The high-affinity PROPPIN binding domain of Atg18p (erstwhile known as Svp1p) has exquisite specificity and affinity in vitro, but is almost certainly biased by additional molecular interactions in vivo [16]. A recent report proposed use of the cytosolic N-terminal domain from the mucolipin transient receptor potential channel (TRPML1) as a biosensor; the probe was reported to show good specificity for PI(3,5)P2 in vitro, and to exhibit dependence on this lipid for localization in cells, based on reduced co-localization with late endo-lysosomal markers after pharmacological or genetic depletion of the lipid [83]. However, our own efforts using time-lapse imaging in live cells show no release of the probe after PI(3,5)P2 depletion with pharmacological or enzymatic means (G.R.V.H. and T.B., unpublished observations), and for this reason we list this biosensor as ambiguous with respect to satisfying the cellular criteria in Table 1.

In summary, we encourage a critical approach when interpreting the localization of PPIn biosensors, and it has been rare to identify probes which generate definitive answers to a particular lipids’ cellular distribution. We have attempted to fill some of the gaps in the criteria we propose to assess fidelity of these probes in Figure 3. Although there is certainly room for the development of new and improved biosensors, there are high-quality probes available for most of the PPIn (as listed in Table 1).

PPIn binding proteins as biosensors-Quantitation

So far, we have discussed the capacity of biosensors to localize particular pools of PPIn. Yet this is only half the story; the capacity of cells to dynamically alter the concentration of a PPIn is crucial to temporal modulation of protein function, and is the central mechanism underlying these lipids’ signaling functions. Prior to the advent of biosensors, biochemical measurements based on isotopic labeling or chemical determination of mass were required for quantitation of PPIn from cells [84], which have recently been joined by advances in lipid mass spectrometry [85]. Although these methods are accurate, they are unable to provide single cell resolution, and sub-cellular resolution requires laborious and artifact-prone fractionation. The newly emerging methodology of imaging mass spectrometry using magnetic sector secondary ion mass spectrometry offers great promise for solving these problems in the near future [86]. In the meantime, fluorescent biosensors provide a readily available solution, with the added advantage that PPIn dynamics can be monitored in living cells. For an ideal biosensor meeting each criteria from Table 1, the extent of membrane localization will vary depending on the concentration of PPIn. How quantitative is this relationship?

Before we can answer this question, we need to consider the potential for these biosensors to fail as passive and unobtrusive reporters for their target lipids. Most of the biosensors listed in table 1 are single domains that bind the lipid with a 1:1 stoichiometry and a characteristic dissociation constant, Kd. Some are tandem dimers or even trimers of such domains, increasing their avidity with the consequent multiplicative enhancement of the effective Kd. In either case, for the sensors to be able to detect a cellular pool of PPIn then the unbound, free lipid must be present at concentrations ~Kd-averaged across the entire volume of the cytoplasm for 1:1 binding, or measured locally in the plane of the membrane for probes with multiple lipid binding sites. Problems can arise as the concentration of biosensor expressed in the cell approaches or even exceeds the Kd, since in this case a substantial fraction of the free PPIn will be sequestered by the biosensor. This can lead to competition with and ultimately displacement of endogenous PPIn binding proteins, and result in disruption of their physiological function. At present, we have very little information on the homeostatic mechanisms that regulate the steady state accumulation of PPIn-especially the more abundant PtdIns(4,5)P2, PtdIns4P and PtdIns3P lipids. It is possible that cells can sense the free lipid concentration and adjust synthesis to maintain this level if a fraction becomes sequestered by an over-expressed binding protein-but to our knowledge this has never been definitively demonstrated. What has been shown is that over-expression of PtdIns(4,5)P2 biosensors can lead to inhibitory effects on PLC signaling [63,87] and exocytosis [88]. Indeed, inhibition can be a useful test of the role of a PPIn in a cellular process. This consideration is especially important for PPIn that accumulate in low abundance such as PtdIns(3,4,5)P3, since biosensors exhibit sub micromolar Kd [89,90] and are known to produce inhibitory effects [91].

Regardless of whether a significant fraction of the free PPIn is bound, it is important to consider what a lipid biosensor actually reports on: a fraction of the endogenous PPIn, sampled from the free PPIn pool but that is now in complex with the biosensor. This has two fundamental consequences: Firstly, PPIn molecules that associate with endogenous effector proteins, which as we discussed in the first section execute all of the lipids’ biological functions, are invisible to the biosensor. Consider the interaction of the clathrin mediated endocytosis machinery with PtdIns(4,5)P2 in the plasma membrane (See the review by Haucke in this issue); as these proteins oligomerize they may sequester and concentrate PtdIns(4,5)P2. Because this local PtdIns(4,5)P2 is sequestered by a high local concentration of binding proteins, the free PtdIns(4,5)P2 concentration could be much lower than outside the clathrin-coated pit and therefore – perversely – the biosensor could report a lower local enrichment of lipid. Secondly, as soon as a biosensor binds a lipid, any other interactions with the inositol ring are occluded; since these biosensor: lipid complexes exhibit rapid diffusion ~ μm/s with substantial binding times (~s) [92–94], they have the potential to “smear out” local heterogeneities in local PtdIns(4,5)P2 over a micron scale. This is particularly important to bear in mind when attempting to utilize these tools with methods that localize the lipid with high resolution (i.e. both electron and “super-resolution” light microscopy).

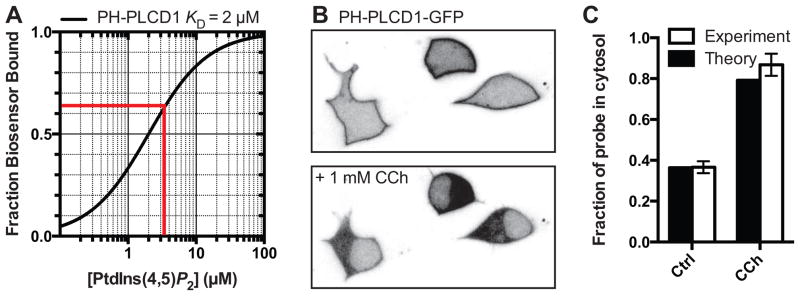

The concentration of biosensor present is rarely determined, but may typically reach micromolar levels [95]. Therefore, the minimum expression levels required to produce acceptable signal to noise in images is strongly advised. This criteria becomes increasingly less difficult to satisfy with ongoing advances in camera and photomultiplier tube sensitivity. For the time being, we will assume that the concentration of biosensor is much less than the effective PPIn concentration. In this case, we can think of the lipids as ligands in excess binding to biosensor “receptors”; the fraction of biosensor bound can then be estimated as [PPIn]/Kd+[PPIn], where concentrations are denoted in square brackets. As a well characterized example, we will take PtdIns(4,5)P2, with the biosensor derived from the PH domain from PLCD1 (Table 1). This domain has a well established Kd of 2 μM for binding to PtdIns(4,5)P2 [3,4,96], and for now we will ignore binding to Ins(1,4,5)P3. Considering the cellular [PtdIns(4,5)P2], McLaughlin has estimated this from first principles to be ~ 10 μM [97], corresponding to empirical estimates ranging from ~4 μM in neuroblastoma cells [95] to ~17 μM in fibroblasts [98]. Therefore, we can estimate the fraction of biosensor bound to PtdIns(4,5)P2 as anything from 50% to 90% (Figure 4A), which grossly fits with what is observed. For example, Figure 4 shows a human neuroblastoma cell line (SH-SY5Y) with approximately 64% of its PH-PLCD1-GFP estimated to be present at the plasma membrane, corresponding to an estimated [PtdIns(4,5)P2] of 3.5 μM, in good agreement with estimates for mouse neuroblastomas [95].

Figure 4. quantitative aspects of a PtdIns(4,5)P2 biosensor.

A. The fraction of PH-PLCD1-GFP expected to be membrane bound in a cell with varying PtdIns(4,5)P2 concentrations. For SH-SY5Y cells the fraction bound (~64%, red line) was estimated after treating cells with ionomycin to cause complete release of the probe into the cytosol, giving the estimated [PtdIns(4,5)P2] = 3.5 μM. B. Three SH-SY5Y cells expressing PH-PLCD1-GFP, either at rest of after activation of endogenous cholinergic M3 receptors with carbachol. C. Carbachol treatment is known to induce ~85% depletion of PtdIns(4,5)P2, and the theoretical and experimentally-measured change in cytosolic fraction of biosensor is shown. See text for details.

Now lets consider a fairly subtle change in [PtdIns(4,5)P2]: treatment of SH-SY5Y with micromolar wortmannin to inhibit PtdIns 4-kinases, which causes a modest ~15% reduction in PtdIns(4,5)P2 [99] to ~3 μM. This will cause the cytosolic fraction of PH-PLCD1-GFP to increase from 36%, to 40%, a factor of 10%. How easy would this be to detect? A simple but effective measurement (as performed in Figure 4) is to measure the fluorescence intensity of a region of interest in the cytoplasm. The confocal volume imaged with a high numerical aperture objective effectively excludes membrane fluorescence axial to the focal plane in a typical tissue culture cell several microns thick, so assuming an adequate signal to noise ratio, the 10% increase should be readily detectable. However, precise quantitation of such fluorescence changes is subject to a number of caveats. Firstly, motile cellular structures that exclude the biosensor and occupy a significant fraction of the confocal volume (mitochondria are a good example) can cause fluctuations in the fluorescence recorded from a region of cytosol. Next, many biosensors are small enough to diffuse into the nucleus, so fluorescence increases in the cytosol from newly released probe then equilibrates relatively slowly with the nuclear pool. Finally, cell movement itself can be an issue, especially for extended measurements or when agonists are used that stimulate cytoskeletal dynamics. For these reasons, although small changes can be detected, they are difficult to accurately quantify.

A way to avoid many of the problems with cytosolic measurements is to apply fluorescence microscopy techniques that measure fluorescence intensity specifically of the membrane associated fraction of biosensor. One method is to employ total internal reflection fluorescence (TIRF) microscopy, which selectively illuminates a sub-resolution (typically ~100 nm) layer at the glass water interface. Since this layer encompasses the plasma membrane and relatively little cytosol compared to a confocal or wide-field focal volume, it is exquisitely sensitive [78,92]. Indeed, in our example of wortmannin in SH-SY5Y cells, we expect a change in the fraction of PH-PLCD1-GFP from 64% to 60%, a factor of 6% change in fluorescence. This is well within the range that can be effectively detected by TIRF [78,82].

Another sensitive method is to employ Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET) to detect close proximity of the lipid biosensor with a membrane bound fluorescent protein [100]. This method has the advantage of being applicable to multiple cellular compartments, as opposed to just the plasma membrane with TIRF.

A popular method to boost the measured change in biosensor localization is to record both the membrane-associated and cytosolic fluorescence and calculate the ratio [62,63]. However, this is subject to the same confounds that we list above for cytosolic measurements. Our recent experience with the P4M PtdIns4P biosensor was that the highly motile endosome-associated pool prevented measurements from fixed regions of interest of both the membranes and the cytoplasm, since P4M-decorated vesicles rapidly move in and out of such regions. Our solution was to use other fluorescent markers of these compartments to generate dynamic masked regions of interest, and normalize this to the total cellular fluorescence rather than the cytosol. This method captures increases in fluorescence in the cytosol and other membrane compartments when the probe is displaced from one of its resident Golgi, endosomal or plasma membranes [82]. However, it makes estimations of the fraction of biosensor associated with any given compartment extremely difficult.

Up until this point, with our specific example of the PH-PLCD1-GFP PtdIns(4,5)P2 biosensor, we have ignored binding of the probe to the product of phospholipase C activation, Ins(1,4,5)P3. We do so at our peril, since the PH domain binds this inositol phosphatase with sub-micromolar affinity [4,96]. Returning to our example of SH-SY5Y cells (Figure 4), activation of phospholipase C in these cells causes a decrease of approximately 85% of PtdIns(4,5)P2 mass [99] to an estimated ~0.5 μM, expected to increase the cytosolic fraction of PH-PLCD1-GFP from 36% to 79%. As we can see from Figure 4B & C, the actual increase in PH-PLCD1-GFP is slightly higher, likely reflecting Ins(1,4,5)P3 competing with residual PtdIns(4,5)P2. More generally, the extent to which this competition influences translocation of the probe has been controversial [96,100]. A careful theoretical consideration with empirical measurement revealed that both will influence the translocation of the probe to an extent that depends on the concentrations of PtdIns(4,5)P2, Ins(1,4,5)P3 and-crucially-the biosensor itself [95]. In practice, translocation of PH-PLCD1 cannot be ascribed to a decrease in lipid or increase in inositol phosphate a priori; some knowledge of the concentration of these reactants must be available to draw conclusions.

Fortunately, there are simple steps to avoid this issue. The development of a tandem dimer of PLCD1 PH domains [101] shifts the binding towards the much higher concentration of PtdIns(4,5)P2 in the plane of the membrane relative to Ins(1,4,5)P3 in the cytosol. Furthermore, the Tubby c-terminal domain (Table 1) exhibits virtually no binding to Ins(1,4,5)P3 and therefore decreases in membrane binding are directly attributable to decreases in PtdIns(4,5)P2 [66,87,102]. A new class of biosensor selective for lipid has emerged through the use of PtdIns(4,5)P2-regulated ion channels such as Kir2.1, which allow rapid and high precision recordings of currents as a proxy for the relative lipid concentration [103,104], although careful selection of channels or their mutants with affinities matching the lipid concentration is necessary for accurate measurement [105], exactly as it is for fluorescent protein biosensors.

Recent efforts have been made to generate a quantitative PtdIns(4,5)P2 biosensor based on the ENTH domain (Table 1) and fused to an organic fluorophore that exhibits a blue shift upon membrane binding [98]. This elegant approach permits ratiometric imaging of the green cytosolic vs. blue membrane-bound fluorescence as a robust and precise read out of fraction of probe bound, and that is readily calibrated to an in vitro binding curve. Although we would argue that this probe is still sensitive to local foldings of the plasma membrane in ruffles and vili etc. that may concentrate membrane relative to cytosol in a confocal volume, this approach may still prove advantageous when precise quantitative measurements are a must.

Throughout these detailed discussions have focused on PtdIns(4,5)P2, but the conclusions are applicable to available biosensors against all the PPIn. When combined with modern high-sensitivity fluorescence microscopy (or even electrophysiological) techniques, these probes can be extremely sensitive and detect relatively minor changes in the levels of a PPIn pool in cells (~10%). In fact, it may even be possible to make quantitative estimates of the lipid level, if the stoichiometry of the probe is known, the Kd has been reliably determined and the concentration of biosensor is measured to be substantially lower than that of the PPIn pool. However, these criteria are rarely met in a typical experiment, and so for the time being, accurate and precise quantitation of PPIn concentrations with the current stable of biosensors is extremely difficult (and indeed, is not easy with traditional biochemical methods). We urge the reader to exercise caution when interpreting a reduction in signal with any biosensor as evidence of the equivalent quantitative change in lipid abundance.

Cellular distribution of PPIn

Having discussed in depth the utility of PPIn binding domains as biosensors for detecting and quantifying PPIn, we will close with a brief summary of what we have learnt about the lipids’ cellular distribution using these probes. As we can see from Table 1, most of the PPIn show a somewhat restricted cellular distribution and are enriched on specific membranes. However, as we discussed earlier in the article, biosensors have the caveats of only being able to detect pools of PPIn that accumulate at concentrations ~ Kd, and of sometimes exhibiting additional interactions that mislead as to how restricted a PPIn distribution really is. Indeed, the versatile “co-incidence detection” mechanism for directing protein-PPIn interaction, as well as emerging roles of lipid transport proteins make it possible that small pools of PPIn, either highly localized in a specific compartment or else present at concentrations below those detectable with the current biosensors, may exist. For these reasons, we have included this discussion as a separate section to include evidence from more traditional approaches of PPIn biochemistry and enzymology. Note that we restrict our discussion to the PPIn present in cytoplasmic membranes; although the generation of PPIn in the nucleus is an exciting field, they appear to function largely independently of the cytoplasmic pool, and are discussed in an accompanying review by Divecha.

PtdIns

PtdIns is the precursor of all PPIn yet, ironically, we have the least amount of information about its distribution between the various membranes. PtdIns constitutes about 10–20% (mol%) of total cellular phospholipids depending on the cell or tissue. It is produced in the ER where its synthesizing enzymes, PtdIns synthase (PIS) and CDP-DG synthase (CDS) are located [106]. Early studies based on membrane fractionation in kidney and liver have found PtdIns at the highest level in the Golgi and the ER (7–12 mol % of total phospholipid) although with significant tissue differences [36]. Based on the fact that PtdIns is converted to PtdIns3P in early endosomes and PtdIns4P in the Golgi, plasma membrane (PM), early-and late endosomes, it is assumed that PtdIns must be present in all of those membranes. PtdIns is believed to be distributed from its site of synthesis in the ER to other membranes either by vesicular transport or by non-vesicular lipid transfer proteins, with PtdIns transfer proteins (PITPs) [107,108] thought to be responsible for the latter. It has been postulated that PITPs transfer PtdIns from the ER to the Golgi [109] or from the ER to the PM [110,111]. Interestingly, over-expressed PIS enzyme generates an ER-derived highly mobile membrane compartment that is dependent on PIS enzymatic activity. This may help to deliver PtdIns to various membranes [106]. With all these putative rapid PtdIns distribution mechanisms in place, the steady-state level of PtdIns is quite unpredictable, as the lipid could be made available at any membrane simply based on demand. Curiously, our efforts to obtain indirect information on PtdIns distribution by the use of a PtdIns-specific bacterial PLC enzyme, together with a sensitive diacylglycerol (DG) probe to capture the product, showed that the PLC was able to accumulate DG in the PM, but DG was not detectable in the ER even when the PLC was targeted to the ER membrane [106]. Whether this reflects the rapid metabolism of the generated DG in the ER, the inability of the DG probe to detect DG in ER membranes or a true low steady-state level of PtdIns in the site of its synthesis remains to be determined. However, studies on red blood cell membranes showed the presence of substantial amount of PtdIns [112,113], which together with the above results strongly argues that the PM does contain PtdIns in significant amounts.

PtdIns4P

This lipid constitutes about 2–5% of total PtdIns in a typical mammalian cell [95,99]. PtdIns4P has been clearly recognized a long time ago as the precursor of plasma membrane PtdIns(4,5)P2, so there was little doubt that it must be present in the PM. It came then as a surprise that none of the cloned mammalian PI4Ks are particularly PM localized; instead, they are found enriched in the Golgi and several endosomal compartments (except for the yeast Stt4p that appears PM localized [114]) [115]. However, the existence of a PM pool of PtdIns4P was indicated by the fact that the PIP5Ks that use this lipid were associated with the PM. The presence of PtdIns4P in these compartments was then confirmed initially by immuno-staining [116] and most recently by the new unbiased P4M probe from the Legionella protein SidM [82]. Based on these measurements and given the estimated fraction of the PM of all the cellular membranes (estimated 1–14% of total cell surface) [117], a substantial fraction of the total PtdIns4P must be present in the PM. This conclusion is also supported by cell fractionation studies using [3H]-inositol labeled lipids [118]. It is worth noting that metabolic labeling with 32P-phosphate labels PtdIns4P most rapidly, but this pool with high metabolic turnover does not represent PtdIns4P across the whole cell. Based on inhibitor studies the high PtdIns4P labeling likely over-represents the PM pool of PtdIns4P that is generated by PI4KA [119]. PtdIns4P in various compartments is made by distinct PI4K enzymes: the Golgi pool is primarily produced by PI4KB [120] with help from PI4K2A and B, especially in the Tgn [121,122], whereas the early and late endosomal PtdIns4P is made by the type II PI4Ks [82], although a lysosomal function of PI4KB has also been reported [123]. The PM pool is mostly generated by PI4KA but based on studies in red blood cell membranes, type II PI4Ks probably also make a contribution. Although PtdIns4P is not detected in the ER, the ER localization of PI4KA and its pivotal role in the formation of the probably ER-derived viral replication “membranous web” in hepatitis C infected cells [124], suggest that PtdIns4P is important in the ER possibly at ER exit sites or the ERGIC compartment [125].

PtdIns3P

In mammalian cells, PtdIns3P is present in a low amount representing about 5–10% of PtdIns4P [126]. In yeast, however, the levels of PtdIns3P and PtdIns4P are comparable [127]. There is relatively little ambiguity that PtdIns3P is found primarily in early endosomes, since several specific and high affinity biosensors are available for PtdIns3P (Table 1). To our knowledge, no study has directly assessed whether this lipid is sufficient to drive localization of these probes. That said, the consistent early-endosomal localization achieved with these structurally unrelated domains strongly imply that they correctly report this as the major pool present in cells. An EM analysis using a recombinant 2xFYVE domain also showed concentration of the lipid associated with the internal vesicular membranes of multivesicular bodies (MVBs) [60]. PtdIns3P has a high turnover rate requiring constitutive PtdIns phosphorylation, as indicated by the rapid disappearance of the PtdIns3P-sensing lipid probes after inhibition of the PI 3-kinases [60]

Notably, a recent cell fractionation study has found the majority of PtdIns3P associated with ®COP positive ER/Golgi membranes [118]. Whether this reflects a redistribution of the lipid during fractionation or the inability of the lipid probes to locate the lipid in this compartment, is yet to be seen. Importantly, several studies have shown the essential role of the Class III PI3K, hVps34 in autophagosomal membrane formation [128]. This is an important point to recognize as the origin of these autophagosomal membranes are believed to be the ER with the help from mitochondria [129], but not particularly from endosomes. This finding would agree with the lipid being found in the ER. The bigger question related to PtdIns3P, however, is which enzyme(s) are responsible for its production. It is clear that hVps34 is a major source of PtdIns3P in early endosomes and in autophagosomes, but there is increasing evidence that Class II PI3Ks may also generate this lipid in specific endosomal compartments [130]. Again, the conclusion that can be drawn from all of these reports is that PtdIns3P levels may not have to be very high (detectable by our current probes) at all places where the lipid plays an important role by interaction with downstream effector proteins.

PtdIns5P

This is one of the most enigmatic members of the PPIn family. It is estimated that its levels are about 1 % of PtdIns4P in mammalian cells [118,126] and its localization is highly debated (Figure 1). The importance of this lipid is recognized, as it serves as the precursor of the type II PIP kinases [131]. Although the exact role of these enzymes is still being explored, their possible nuclear functions [132] and connections to Akt and mTOR signaling [59,133,134] and carcinogenesis [135,136] makes PtdIns5P a highly desirable target to investigate, although as we discussed earlier, no probe is available that can detect the scant endogenous level. Cell fractionation studies have found the highest amount of PtdIns5P in PM fractions [118,137] and an enrichment of the lipid in ER/Golgi fractions [118] or in early endosomes [133]. Enzymatically, PtdIns5P can be formed directly by PtdIns phosphorylation by the PIKfyve enzyme [138], or via dephosphorylation of PtdIns(3,5)P2 by myotubularin phosphatases [126]. Which of these pathways are more important in the cell is still highly debated. It is now generally assumed that type II PIP kinases are more important in controlling PtdIns5P levels than generating PtdIns(4,5)P2, the majority of which is made via the canonical PtdIns4P phosphorylation route [137].

PtdIns(4,5)P2

This is the most abundant phosphorylated PPIn, amounting to 2–5 % of total PtdIns [95,99]. Notably, yeast and plants contain significantly lower levels of PtdIns(4,5)P2 and more PtdIns4P than mammalian cells [139,140]. Most of the PtdIns(4,5)P2 is located in the PM as shown either by expressed fluorescent lipid reporters [64] or by anti-PtdIns(4,5)P2 antibodies or recombinant PH domains [61]. EM analysis of PtdIns(4,5)P2 distribution assessed by a GST-fused PLC™1PH domain also showed small amounts in the Golgi and endosomes [53]. However, biochemical evidence suggests that PtdIns(4,5)P2 can regulate Golgi-localized effectors such as various Arf1 GAPs [42,43], making a small amount of PtdIns(4,5)P2 in the Golgi feasible. An intracellular role of PtdIns(4,5)P2 has also been shown for endolysosomal processing of EGF receptors and E-cadherin [141,142], although many 5-phosphatases are important during endocytosis at the plasma membrane to strip PtdIns(4,5)P2 before conversion to 3 phosphorylated PPIn on the endosomes [143].

As the number of PM-bound effectors regulated by PtdIns(4,5)P2 is increasing [2], the question arises: how is the lipid able to control so many effectors seemingly independently in the same membrane? Several theories have been entertained, some suggesting the existence of PtdIns(4,5)P2 enriched membrane domains, related or unrelated to lipid rafts, the existence of lateral diffusion barriers, or the localized channeling of the lipids by the kinases to specific molecular effectors etc. Experimental evidence for these mechanisms are not easy to obtain. The other hard-to-explain findings are related to the relationship between the PM-localized PtdIns4P and PtdIns(4,5)P2. It appears that cells can maintain their basal PtdIns(4,5)P2 levels at a wide range of PM PtdIns4P [38,119] even though it is clear that PM PtdIns4P is an obligate intermediate for PtdIns(4,5)P2 synthesis. How cells sense their PM PtdIns(4,5)P2 levels and what homeostatic mechanisms keep it within a range are exciting questions for future studies. What is clear at present is that the major pool of PtdIns(4,5)P2 resides and is indeed metabolized at the PM, where it is required to control an assortment of transport, signaling and cytoskeletal processes.

PtdIns(3,4)P2

This is also a minor lipid with basal levels at detection limits but it can substantially increase upon activation of PI3Ks. The largest elevation in PtdIns(3,4)P2 is achieved by treatment with H2O2, which, through inhibition of PTEN and probably the PtdIns(3,4)P2 phosphatases, INPP4A/B, slowly converts almost the entire PtdIns(4,5)P2 pool to PtdIns(3,4)P2 [144,145]. However, in a normal stimulated cell PtdIns(3,4)P2 levels reach only 2–5 % of those of PtdIns(4,5)P2 [146]. Because the main source of PtdIns(3,4)P2 is PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 made by Class I PI3Ks in the plasma membrane and dephosphorylated by SHIP1/2 5-phosphatases, this lipid was assumed to be localized to the PM. This was confirmed with the use of the TAPP1 PH domain as a probe in live [147] or fixed cells [146] and the lipid was found especially enriched in lamellopodia [148,149]. EM analysis using the TAPP1 PH domain as a probe found some of the lipid in the ER and endosomes, especially in the lumen of MVBs [57]. A recent study unveiled a role of PtdIns(3,4)P2 in controlling the maturation of clathrin-coated vesicles and showed the presence of the lipid in late stages of endocytic intermediates [143]. Therefore, the current view is that PtdIns(3,4)P2 is most likely generated at the PM, but may persist through endocytotic events and therefore be trafficked to distant membrane compartments.

PtdIns(3,5)P2

This minor PPIn is critical for the proper sorting of cargoes in the late endosomal stage and during formation of the internal vesicles in MVBs. PtdIns(3,5)P2 levels in yeast are ~50% of those of PtdIns(4,5)P2 [140,150]. Their amount is significantly lower in mammalian cells (1% of PtdIns(4,5)P2 [126,138]) making it the PPIn of lowest abundance. Because of the lack of appropriate tools to visualize them, the localization of this lipid species has been deduced only from functional studies and from the localization of the enzymes that make and degrade this lipid species. A recent study has reported the localization of PtdIns(3,5)P2 to late-endosomes/lysosomes using a tandem sequence from the N-terminus of the mucolipin channel, TRPML1 as a probe [83]. However, we have been unable to substantiate these claims (see above). Immunostaining with an anti PI(3,5)P2 antibody showed a mitochondrial staining [151] but based on what we know about PI(3,5)P2 physiology this localization is highly questionable. Therefore we are still searching for an appropriate tool to find this lipid inside the cell.

PtdIns(3,4,5)P3

This minor lipid has generated a lot of attention because of its oncogenic potential. It represents about 1–5% of PtdIns(4,5)P2 with almost undetectable levels in quiescent cells that rise upon activation of Class I PI3Ks [152]. PtdIns(3,4,5)P2 is generated primarily in the plasma membrane and that is where it has been detected either in live cells using PH-domain-based reporters (See table 1) or by antibody staining [153]. PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 shows significant enrichment within the plasma membrane in the front of migrating cells pointing to the chemotactic source but also in active membrane domains such as lamellopodia [154]. Perhaps the most striking lateral segregation and concentration of PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 is seen in the phagocytic cup [155], where the diffusion of the lipid must be significantly curtailed to maintain a localized enrichment. Intracellular PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 has not been detected widely, but a recent study showed that PI3Kγ associated with its p101 regulatory subunit generates a PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 pool in the PM that undergoes endocytosis whereas the PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 pool produced by the p84/p110γ complex remains in the PM [156].

Perspective

The Biology of PPIn has been active since the 1940s, with our appreciation of their protein interactions exploding in the 1990s, as we saw in the first section of this review. Although many principles of protein-PPIn interaction are understood, often with atomic resolution, new examples continue to be discovered and we are far from genomic annotation with a completed list of these interactions. Recent discoveries of the coupling of PPIn metabolism with lipid transfer [50,80,157] and host-pathogen interaction (see the review by Cossart in this issue) underscore how new paradigms continue to emerge.

In light of these continuing advances, it is clear there is still plenty of utility for the current toolbox of PPIn biosensors (table 1), and indeed for the development of improved versions. Despite the limitations discussed in this review, there are currently excellent tools for the detection of most PPIn in living cells. The current lack of proven probes for PtdIns(3,5)P2, PtdIns5P and PtdIns are notable gaps and are priorities for the future. Another key question is how cells co-ordinate these legion protein-PPIn interactions, and couple this to feedback control of PPIn metabolism. The development of new tools that can probe these interactions at the molecular scale will be key to finding answers. We are particularly excited by recent advances in the fields of liquid-chromatography mass spectrometry [85], “imaging” mass spectrometry [86] and the field of super-resolution light microscopy [158] as being poised to produce new insights in this area. In short, we look forward to yet more discoveries in biosensor development driving our understanding of basic PPIn biology and its impact on human disease.

Highlights.

Polyphosphoinositides (PPIn) binding domains come from many families, with a broad spectrum of affinity and selectivity

Their regulation by lipids can take several forms, from simple membrane targeting to specific allosteric regulation

High affinity, specific binding domains can make excellent probes to study the lipids in living cells

The usefulness of the probes depends on their specificity, and whether the target lipid is necessary and sufficient for targeting

Quantitation with such probes requires careful consideration of binding affinity

PPIn binding domains have been instrumental in defining the cellular distribution of the various PPIn on plasma, endocytic and late secretory membranes.

Contributor Information

Gerald R. V. Hammond, Email: gerald.hammond@nih.gov.

Tamas Balla, Email: ballat@mail.nih.gov.

References

- 1.Michell RH, Heath VL, Lemmon M, Dove SK. Phosphatidylinositol 3,5-bisphosphate: metabolism and cellular functions. Trends Biochem Sci. 2006;31:52–63. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2005.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Balla T. Phosphoinositides: tiny lipids with giant impact on cell regulation. Physiol Rev. 2013;93:1019–1137. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00028.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garcia P, Gupta R, Shah S, Morris AJ, Rudge SA, Scarlata S, et al. The pleckstrin homology domain of phospholipase C-delta 1 binds with high affinity to phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate in bilayer membranes. Biochemistry. 1995;34:16228–16234. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307285101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lemmon M, Ferguson KM, O’Brien R, Sigler PB, Schlessinger J. Specific and high-affinity binding of inositol phosphates to an isolated pleckstrin homology domain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:10472–10476. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.23.10472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lemmon M. Phosphoinositide recognition domains. Traffic. 2003;4:201–213. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2004.00071.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Niggli V, Andréoli C, Roy C, Mangeat P. Identification of a phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate-binding domain in the N-terminal region of ezrin. FEBS Lett. 1995;376:172–176. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)01270-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hirao M, Sato N, Kondo T, Yonemura S, Monden M, Sasaki T, et al. Regulation mechanism of ERM (ezrin/radixin/moesin) protein/plasma membrane association: possible involvement of phosphatidylinositol turnover and Rho-dependent signaling pathway. J Cell Biol. 1996;135:37–51. doi: 10.1083/jcb.135.1.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burd CG, Emr SD. Phosphatidylinositol(3)-phosphate signaling mediated by specific binding to RING FYVE domains. Mol Cell. 1998;2:157–162. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80125-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gaullier JM, Simonsen A, D’Arrigo A, Bremnes B, Stenmark H, Aasland R. FYVE fingers bind PtdIns(3)P. Nature. 1998;394:432–433. doi: 10.1038/28767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Patki V, Lawe DC, Corvera S, Virbasius JV, Chawla A. A functional PtdIns(3)P-binding motif. Nature. 1998;394:433–434. doi: 10.1038/28771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kanai F, Liu H, Field SJ, Akbary H, Matsuo T, Brown GE, et al. The PX domains of p47phox and p40phox bind to lipid products of PI(3)K. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:675–678. doi: 10.1038/35083070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ellson CD, Gobert-Gosse S, Anderson KE, Davidson K, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, et al. PtdIns(3)P regulates the neutrophil oxidase complex by binding to the PX domain of p40(phox) Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:679–682. doi: 10.1038/35083076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xu Y, Hortsman H, Seet L, Wong SH, Hong W. SNX3 regulates endosomal function through its PX-domain-mediated interaction with PtdIns(3)P. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:658–666. doi: 10.1038/35083051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ford MG, Pearse BM, Higgins MK, Vallis Y, Owen DJ, Gibson A, et al. Simultaneous binding of PtdIns(4,5)P2 and clathrin by AP180 in the nucleation of clathrin lattices on membranes. Science. 2001;291:1051–1055. doi: 10.1126/science.291.5506.1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Itoh T, Koshiba S, Kigawa T, Kikuchi A, Yokoyama S, Takenawa T. Role of the ENTH domain in phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate binding and endocytosis. Science. 2001;291:1047–1051. doi: 10.1126/science.291.5506.1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dove SK, Piper RC, McEwen RK, Yu JW, King MC, Hughes DC, et al. Svp1p defines a family of phosphatidylinositol 3,5-bisphosphate effectors. Embo J. 2004;23:1922–1933. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rousseau A, McEwen AG, Poussin-Courmontagne P, Rognan D, Nominé Y, Rio MC, et al. TRAF4 is a novel phosphoinositide-binding protein modulating tight junctions and favoring cell migration. Plos Biol. 2013;11:e1001726. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lemmon M, Yu JW. All phox homology (PX) domains from Saccharomyces cerevisiae specifically recognize phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:44179–44184. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108811200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yu JW, Mendrola JM, Audhya A, Singh S, Keleti D, DeWald DB, et al. Genome-wide analysis of membrane targeting by S. cerevisiae pleckstrin homology domains. Mol Cell. 2004;13:677–688. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(04)00083-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Scheffzek K, Welti S. Pleckstrin homology (PH) like domains-versatile modules in protein-protein interaction platforms. FEBS Lett. 2012;586:2662–2673. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2012.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Klarlund JK, Tsiaras W, Holik JJ, Chawla A, Czech MP. Distinct polyphosphoinositide binding selectivities for pleckstrin homology domains of GRP1-like proteins based on diglycine versus triglycine motifs. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:32816–32821. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002435200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Venkateswarlu K, Oatey PB, Tavaré JM, Cullen PJ. Insulin-dependent translocation of ARNO to the plasma membrane of adipocytes requires phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase. Curr Biol. 1998;8:463–466. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)70181-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Venkateswarlu K, Gunn-Moore F, Oatey PB, Tavaré JM, Cullen PJ. Nerve growth factor-and epidermal growth factor-stimulated translocation of the ADP-ribosylation factor-exchange factor GRP1 to the plasma membrane of PC12 cells requires activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and the GRP1 pleckstrin homology domain. Biochem J. 1998;335(Pt 1):139–146. doi: 10.1042/bj3350139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cronin TC, DiNitto JP, Czech MP, Lambright DG. Structural determinants of phosphoinositide selectivity in splice variants of Grp1 family PH domains. Embo J. 2004;23:3711–3720. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Várnai P, Bondeva T, Tamás P, Tóth B, Buday L, Hunyady L, et al. Selective cellular effects of overexpressed pleckstrin-homology domains that recognize PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 suggest their interaction with protein binding partners. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:4879–4888. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hofmann I, Thompson A, Sanderson CM, Munro S. The Arl4 family of small G proteins can recruit the cytohesin Arf6 exchange factors to the plasma membrane. Curr Biol. 2007;17:711–716. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cohen LA, Honda A, Várnai P, Brown FD, Balla T, Donaldson JG. Active Arf6 recruits ARNO/cytohesin GEFs to the PM by binding their PH domains. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18:2244–2253. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-11-0998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li CC, Chiang TC, Wu TS, Pacheco-Rodriguez G, Moss J, Lee FJS. ARL4D recruits cytohesin-2/ARNO to modulate actin remodeling. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18:4420–4437. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-02-0149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Coincidence detection in phosphoinositide signaling. 2005 doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2005.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van Weering JRT, Sessions RB, Traer CJ, Kloer DP, Bhatia VK, Stamou D, et al. Molecular basis for SNX-BAR-mediated assembly of distinct endosomal sorting tubules. The EMBO Journal. 2012;31:4466–4480. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weber SS, Ragaz C, Reus K, Nyfeler Y, Hilbi H. Legionella pneumophila exploits PI(4)P to anchor secreted effector proteins to the replicative vacuole. PLoS Pathog. 2006;2:e46. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brombacher E, Urwyler S, Ragaz C, Weber SS, Kami K, Overduin M, et al. Rab1 guanine nucleotide exchange factor SidM is a major phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate-binding effector protein of Legionella pneumophila. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:4846–4856. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M807505200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Salomon D, Guo Y, Kinch LN, Grishin NV, Gardner KH, Orth K. Effectors of animal and plant pathogens use a common domain to bind host phosphoinositides. Nat Comms. 2013;4 doi: 10.1038/ncomms3973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yeung T, Terebiznik M, Yu L, Silvius J, Abidi WM, Philips M, et al. Receptor activation alters inner surface potential during phagocytosis. Science. 2006;313:347–351. doi: 10.1126/science.1129551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yeung T, Gilbert GE, Shi J, Silvius J, Kapus A, Grinstein S. Membrane phosphatidylserine regulates surface charge and protein localization. Science. 2008;319:210–213. doi: 10.1126/science.1152066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zambrano F, Fleischer S, Fleischer B. Lipid composition of the Golgi apparatus of rat kidney and liver in comparison with other subcellular organelles. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1975;380:357–369. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(75)90104-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Heo WD, Inoue T, Park WS, Kim ML, Park BO, Wandless TJ, et al. PI(3,4,5)P3 and PI(4,5)P2 lipids target proteins with polybasic clusters to the plasma membrane. Science. 2006;314:1458–1461. doi: 10.1126/science.1134389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hammond GRV, Fischer MJ, Anderson KE, Holdich J, Koteci A, Balla T, et al. PI4P and PI(4,5)P2 are essential but independent lipid determinants of membrane identity. Science. 2012;337:727–730. doi: 10.1126/science.1222483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gambhir A, Hangyás-Mihályné G, Zaitseva I, Cafiso DS, Wang J, Murray D, et al. Electrostatic sequestration of PIP2 on phospholipid membranes by basic/aromatic regions of proteins. Biophys J. 2004;86:2188–2207. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(04)74278-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lemmon M, Moravcevic K, Mendrola JM, Schmitz KR, Wang YH, Slochower D, et al. Kinase Associated-1 Domains Drive MARK/PAR1 Kinases to Membrane Targets by Binding Acidic Phospholipids. Cell. 2010;143:966–977. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.11.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Calleja V, Alcor D, Laguerre M, Park J, Vojnovic B, Hemmings BA, et al. Intramolecular and intermolecular interactions of protein kinase B define its activation in vivo. Plos Biol. 2007;5:e95. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kam JL, Miura K, Jackson TR, Gruschus J, Roller P, Stauffer S, et al. Phosphoinositide-dependent activation of the ADP-ribosylation factor GTPase-activating protein ASAP1. Evidence for the pleckstrin homology domain functioning as an allosteric site. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:9653–9663. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.13.9653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Campa F, Yoon HY, Ha VL, Szentpetery Z, Balla T, Randazzo P. A PH domain in the Arf GTPase-activating protein (GAP) ARAP1 binds phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate and regulates Arf GAP activity independently of recruitment to the plasma membranes. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:28069–28083. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.028266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jian X, Gruschus JM, Sztul E, Randazzo P. The pleckstrin homology (PH) domain of the Arf exchange factor Brag2 is an allosteric binding site. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:24273–24283. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.368084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hilgemann DW, Feng S, Nasuhoglu C. The complex and intriguing lives of PIP2 with ion channels and transporters. Sci STKE. 2001;2001:re19. doi: 10.1126/stke.2001.111.re19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Whorton MR, MacKinnon R. Crystal Structure of the Mammalian GIRK2 K+ Channel and Gating Regulation by G Proteins, PIP 2, and Sodium. Cell. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.07.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hansen SB, Tao X, MacKinnon R. Structural basis of PIP2 activation of the classical inward rectifier K+ channel Kir2.2. Nature. 2011;477:495–498. doi: 10.1038/nature10370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.de Saint-Jean M, Delfosse V, Douguet D, Chicanne G, Payrastre B, Bourguet W, et al. Osh4p exchanges sterols for phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate between lipid bilayers. J Cell Biol. 2011;195:965–978. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201104062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kono N, Ohto U, Hiramatsu T, Urabe M, Uchida Y, Satow Y, et al. Impaired α-TTP-PIPs interaction underlies familial vitamin E deficiency. Science. 2013;340:1106–1110. doi: 10.1126/science.1233508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mesmin B, Bigay J, Moser von Filseck J, Lacas-Gervais S, Drin G, Antonny B. A Four-Step Cycle Driven by PI(4)P Hydrolysis Directs Sterol/PI(4)P Exchange by the ER-Golgi Tether OSBP. Cell. 2013;155:830–843. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.09.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mousley CJ, Yuan P, Gaur NA, Trettin KD, Nile AH, Deminoff SJ, et al. A sterol-binding protein integrates endosomal lipid metabolism with TOR signaling and nitrogen sensing. Cell. 2012;148:702–715. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.12.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kim YJ, Hernandez MLG, Balla T. Inositol lipid regulation of lipid transfer in specialized membrane domains. Trends Cell Biol. 2013;23:270–278. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2013.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Watt SA, Kular G, Fleming IN, Downes CP, Lucocq J. Subcellular localization of phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate using the pleckstrin homology domain of phospholipase C delta1. Biochem J. 2002;363:657–666. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3630657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.James DJ, Khodthong C, Kowalchyk JA, Martin TFJ. Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate regulates SNARE-dependent membrane fusion. J Cell Biol. 2008;182:355–366. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200801056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hammond GRV, Schiavo G, Irvine RF. Immunocytochemical techniques reveal multiple, distinct cellular pools of PtdIns4P and PtdIns(4,5)P(2) Biochem J. 2009;422:23–35. doi: 10.1042/BJ20090428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fujita A, Cheng J, Tauchi-Sato K, Takenawa T, Fujimoto T. A distinct pool of phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate in caveolae revealed by a nanoscale labeling technique. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2009;106:9256–9261. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900216106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Watt SA, Kimber WA, Fleming IN, Leslie NR, Downes CP, Lucocq J. Detection of novel intracellular agonist responsive pools of phosphatidylinositol 3,4-bisphosphate using the TAPP1 pleckstrin homology domain in immunoelectron microscopy. Biochem J. 2004;377:653–663. doi: 10.1042/BJ20031397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lindsay Y, McCoull D, Davidson L, Leslie NR, Fairservice A, Gray A, et al. Localization of agonist-sensitive PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 reveals a nuclear pool that is insensitive to PTEN expression. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:5160–5168. doi: 10.1242/jcs.000133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pendaries C, Tronchère H, Arbibe L, Mounier J, Gozani O, Cantley L, et al. PtdIns5P activates the host cell PI3-kinase/Akt pathway during Shigella flexneri infection. Embo J. 2006;25:1024–1034. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gillooly DJ, Morrow IC, Lindsay M, Gould R, Bryant NJ, Gaullier JM, et al. Localization of phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate in yeast and mammalian cells. Embo J. 2000;19:4577–4588. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.17.4577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hammond GRV, Dove SK, Nicol A, Pinxteren JA, Zicha D, Schiavo G. Elimination of plasma membrane phosphatidylinositol (4,5)-bisphosphate is required for exocytosis from mast cells. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:2084–2094. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Stauffer TP, Ahn S, Meyer T. Receptor-induced transient reduction in plasma membrane PtdIns(4,5)P2 concentration monitored in living cells. Curr Biol. 1998;8:343–346. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)70135-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Várnai P, Balla T. Visualization of phosphoinositides that bind pleckstrin homology domains: calcium-and agonist-induced dynamic changes and relationship to myo-[3H]inositol-labeled phosphoinositide pools. J Cell Biol. 1998;143:501–510. doi: 10.1083/jcb.143.2.501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Balla T, Bondeva T, Várnai P. How accurately can we image inositol lipids in living cells? Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2000;21:238–241. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(00)01500-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lemmon M, Narayan K. Determining selectivity of phosphoinositide-binding domains. Methods. 2006;39:122–133. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2006.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Santagata S, Boggon TJ, Baird CL, Gomez CA, Zhao J, Shan WS, et al. G-protein signaling through tubby proteins. Science. 2001;292:2041–2050. doi: 10.1126/science.1061233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Stephens L, Jackson TR, Hawkins PT. Agonist-stimulated synthesis of phosphatidylinositol(3,4,5)-trisphosphate: a new intracellular signalling system? Biochim Biophys Acta. 1993;1179:27–75. doi: 10.1016/0167-4889(93)90072-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gozani O, Karuman P, Jones DR, Ivanov D, Cha J, Lugovskoy AA, et al. The PHD finger of the chromatin-associated protein ING2 functions as a nuclear phosphoinositide receptor. Cell. 2003;114:99–111. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00480-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Corbin JA, Dirkx RA, Falke JJ. GRP1 pleckstrin homology domain: activation parameters and novel search mechanism for rare target lipid. Biochemistry. 2004;43:16161–16173. doi: 10.1021/bi049017a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Manna D, Bhardwaj N, Vora MS, Stahelin R, Lu H, Cho W. Differential roles of phosphatidylserine, PtdIns(4,5)P2, and PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 in plasma membrane targeting of C2 domains. Molecular dynamics simulation, membrane binding, and cell translocation studies of the PKCalpha C2 domain. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:26047–26058. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802617200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]