Abstract

Prostaglandin F2α (PGF2α) has been proposed as a functional luteolysin in primates. However, administration of PGF2α or prostaglandin synthesis inhibitors in vivo both initiate luteolysis. These contradictory findings may reflect changes in PGF2α receptors (PTGFR) or responsiveness to PGF2α at a critical point during the life span of the corpus luteum. The current study addressed this question using ovarian cells and tissues from female cynomolgus monkeys and luteinizing granulosa cells from healthy women undergoing follicle aspiration. PTGFRs were present in the cytoplasm of monkey granulosa cells, while PTGFRs were localized to the perinuclear region of large, granulosa-derived monkey luteal cells by mid-late luteal phase. A PTGFR agonist decreased progesterone production by luteal cells obtained at mid-late and late luteal phases but did not decrease progesterone production by granulosa or luteal cells from younger corpora lutea. These findings are consistent with a role for perinuclear PTGFRs in functional luteolysis. This concept was explored using human luteinizing granulosa cells maintained in vitro as a model for luteal cell differentiation. In these cells, PTGFRs relocated from the cytoplasm to the perinuclear area in an estrogen- and estrogen receptor-dependent manner. Similar to our findings with monkey luteal cells, human luteinizing granulosa cells with perinuclear PTGFRs responded to a PTGFR agonist with decreased progesterone production. These data support the concept that PTGFR stimulation promotes functional luteolysis only when PTGFRs are located in the perinuclear region. Estrogen receptor-mediated relocation of PTGFRs within luteal cells may be a necessary step in the initiation of luteolysis in primates.

Keywords: ovary, corpus luteum, primate, prostaglandin, estrogen, luteolysis

INTRODUCTION

Prostaglandin F2α (PGF2α) is widely recognized as a key luteolysin in mammals, including humans and non-human primates. In domestic animals, PGF2α produced by the uterus in the absence of a conceptus is transported to the ovary via a portal or lymphatic circulation, and this PGF2α initiates luteolysis (reviewed in (Niswender & Nett 1994)). A different mechanism appears to control prostaglandin-induced luteolysis in primates since hysterectomy does not alter the length of the luteal phase. For primates, the corpus luteum itself has been proposed as the source of luteolytic PGF2α (Auletta & Flint 1988). Indeed, treatment of mature granulosa-lutein cells in vitro with PGF2α decreases progesterone production, the classic definition of functional luteolysis (Stouffer et al. 1979).

While it has been suggested that PGF2α is luteolytic, other prostaglandins, most notably PGE2, are possibly luteotropic in primates (reviewed in (Stouffer 1991)). Injection of PGF2α directly into the corpus luteum in women decreased serum progesterone and shortened luteal phase length (Bennegard et al. 1991). Similarly, infusion of PGF2α directly into the monkey corpus luteum caused a premature decline in progesterone production, while co-infusion of PGF2α with PGE2 yielded a luteal phase of normal length (Zelinski-Wooten & Stouffer 1990, Auletta et al. 1995). These findings are consistent with the concept that actions of PGF2α are luteolytic, while PGE2 and perhaps other prostaglandins are luteotropic. However, infusion of potentially luteotropic prostaglandins alone did not lengthen luteal life span (Zelinski-Wooten & Stouffer 1990). In these studies, concentrations of luteotropic and luteolytic prostaglandins within luteal tissues did not correlate directly with either maintenance of luteal function or luteolysis. Collectively, these studies do not support the hypothesis that levels of prostaglandins within luteal tissues are primarily responsible for initiation of luteolysis in primates.

Interpretation of these and other studies is complicated by the temporal pattern of PGF2α receptor (PTGFR) expression in the primate ovary. PTGFR mRNA is expressed in both ovulatory follicles and corpora lutea of monkeys and women (Carrasco et al. 1997, Ristimaki et al. 1997, Ottander et al. 1999, Bogan et al. 2008b, Xu et al. 2011). PTGFR mRNA and protein are present in the primate corpus luteum throughout its life span, with peak levels measured in late luteal phase (Ottander et al. 1999, Bogan et al. 2008b, Bogan et al. 2008a). PGF2α levels in follicular fluid and luteal tissue extracts are in the nanomolar to micromolar range (Patwardhan & Lanthier 1981, Lumsden et al. 1986, Auletta et al. 1995, Ottander et al. 1999, Dozier et al. 2008), so PTGFRs are likely exposed to a receptor-saturating concentration of PGF2α throughout the ovulatory period and during the entire luteal life span. Importantly, there are no reports of increased luteal levels of PTGFR or PGF2α specifically at the time that luteolysis is initiated. It has been suggested that changing PTGFR functionality may explain the acquisition of luteolytic responsiveness to PGF2α (Ottander et al. 1999, Tsai et al. 2001), but this concept has not been tested.

To test the hypothesis that PTGFR function changes within primate granulosa-lutein cells in order to initiate luteolysis, we examined PTGFR expression and function in monkey granulosa cells obtained during the ovulatory interval as well as in cells from monkey corpora lutea obtained during the luteal phase. The transition from the granulosa cell phenotype to the granulosa-lutein (luteal) cell phenotype is difficult to assess in vivo. For this reason, additional studies were performed with human luteinizing granulosa cells maintained in vitro, utilizing an established cell culture model which promotes the transition from the granulosa cell to the granulosa-lutein (luteal) cell phenotype (Carrasco et al. 1997, Ristimaki et al. 1997, Chin et al. 2004). Using these complementary approaches, we show for the first time that PTGFRs relocate from the cytoplasm/plasma membrane to the perinuclear/nuclear region of granulosa-lutein cells as these cells acquire sensitivity to PGF2α. Movement of PTGFRs to the perinuclear region is dependent on estrogen, providing a mechanism to explain how the primate corpus luteum may acquire responsiveness to PGF2α and luteolytic capacity.

METHODS

Animals

Granulosa cells, corpora lutea, and whole ovaries were obtained from adult female cynomolgus macaques (Macaca fascicularis) at Eastern Virginia Medical School (EVMS). All animal protocols and experiments were approved by the EVMS Animal Care and Use Committee and were conducted in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Animal husbandry and sample collection were performed as previously described (Seachord et al. 2005). Briefly, blood samples were obtained under ketamine chemical restraint by femoral venipuncture, and serum was stored at −20°C. Aseptic surgeries were performed in a dedicated surgical suite under isofluorane anesthesia, and appropriate post-operative pain control was used.

A controlled ovarian stimulation model developed for the collection of multiple oocytes for in vitro fertilization was used to obtain monkey granulosa cells (Chaffin et al. 1999b). Beginning within 3 days of initiation of menstruation, recombinant human (r-h) FSH (90 IU daily, Merck & Co., Inc., Whitehouse Station, NJ) was administered for 6–8 days, followed by daily administration of 90 IU r-hFSH plus 60 IU r-hLH (Serono Reproductive Biology Institute, Rockland, MA) for 2 days to stimulate the growth of multiple preovulatory follicles. A GnRH antagonist (Antide (0.5 mg/kg body weight; Serono) or Ganirelix (30 μg/kg body weight; Merck)) was also administered daily to prevent an endogenous ovulatory LH surge. Adequate follicular development was monitored by serum estradiol levels and ultrasonography (Wolf et al. 1996). Follicular aspiration was performed during aseptic surgery before (0 hour) or up to 36 hours after administration of 1000 IU r-hCG (Serono) (Chaffin et al. 1999b). At aspiration, each follicle was pierced with a 22-gauge needle, and the contents of all follicles larger than 4 mm in diameter were pooled. Ovulatory follicles in cynomolgus macaques are typically 4–6 mm in diameter as assessed by ultrasonography and confirmed by direct measurement at surgery. Whole ovaries were also obtained from monkeys experiencing ovarian stimulation. These ovaries were bisected, maintaining at least two follicles greater than 4 mm in diameter on each piece. Ovarian pieces were frozen in O.C.T. Compound (Sakura, Tokyo, Japan) and stored at −80°C until sectioned. Sections were fixed in 10% formalin and immunostained.

Corpora lutea were obtained from monkeys experiencing natural menstrual cycles. Serum samples obtained once daily beginning on days 6–9 after menstruation were assayed for estradiol and progesterone. Day 1 of the luteal phase is defined as the first day of low serum estradiol following the midcycle estradiol peak; serum progesterone is elevated above 1 ng/ml by luteal day 2. The corpus luteum was removed from the ovary during aseptic surgery in the early (days 3–4), mid (days 6–8), mid-late (days 10–11), and late (days 12–15) luteal phases (Duffy & Stouffer 1995). Luteal tissues were either dispersed for culture of luteal cells, frozen without O.C.T in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until used for preparation of total RNA or tissue lysates, or frozen in O.C.T. as described above for ovarian tissues and used for histologic sections.

Monkey Granulosa and Luteal Cells

Monkey granulosa cells and oocytes were pelleted from the follicular aspirates by centrifugation at 300 X g. Following oocyte removal, a granulosa cell-enriched population of cells was obtained by Percoll gradient centrifugation (Chaffin et al. 1999a); viability was assessed by trypan blue exclusion and averaged 85%. Granulosa cells were either used for cell culture or frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C.

Corpora lutea were dispersed into individual luteal cells as previously described (Sanders et al. 1996). Briefly, luteal tissue was minced, and pieces were incubated in Ham’s F-10 media containing 1% bovine serum albumin, 0.16% collagenase, and 0.02% DNase I in an atmosphere of 95% O2: 5% CO2 at 37°C. Dispersed mixed luteal cells were held on ice in an atmosphere of 95% O2: 5% CO2 until placed in culture. Viability of mixed luteal cell preparations was assessed by trypan blue exclusion and averaged 96%.

Granulosa and luteal cells were plated on LabTek glass chamber slides (Nalgene Nunc, Rochester, NY) or culture plates. The cells were cultured on fibronectin-coated surfaces in chemically-defined, serum-free DMEM-Ham’s F12 medium containing insulin, transferrin, selenium, aprotinin, and human low-density lipoprotein as previously described (Markosyan et al. 2006). The PTGFR agonist fluprostenol (1 μM; Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI), hCG (20 IU/ml, Sigma), the general cyclooxygenase inhibitor indomethacin (0.1 μM; Sigma), the phospholipase C (PLC) inhibitor U73122 (100 μM; Cayman), the protein kinase C (PKC) inhibitor Ro31-3220 (1 μM; CalBiochem, Billerica, MA), the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitor rapamycin (1 μM; Invitrogen, Rockville, MD), the 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase inhibitor trilostane (250 ng/ml, Stegram Pharmaceuticals, Sussex, UK), progesterone (0.1 μM; Sigma), the aromatase inhibitor letrozole (4,4-[1,2,3-triazol-lyl-methylene]-bis-benzonitrite; 0.5 μM; Norvartis Pharm AG, Basel, Switzerland), estradiol benzoate (0.1 μM; Sigma), and the estrogen receptor antagonist ICI182,780 (1 μM; Tocris Biosciences, Bristol, UK) were added to cultures as indicated. Spent culture media were stored at −20°C pending analysis. Preparation of cells for analysis of mRNA or protein is described below. Cells cultured on chamber slides were fixed in 10% formalin for 30 min, then stored at 4°C in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) until used for immunodetection of PTGFR.

Human Luteinizing Granulosa Cells

Luteinizing granulosa cells were obtained from healthy young women undergoing ovarian stimulation for oocyte donation at the Jones Institute for Reproductive Medicine at EVMS. The Institutional Review Board at EVMS determined that this use of discarded human granulosa cells does not constitute human subjects research as defined by 45 CFR 46.102(f). Follicular aspirates were collected 34–36 hours after administration of an ovulatory dose of hCG, and granulosa cells were transferred to our laboratory after oocyte removal. A granulosa cell-enriched population of cells was obtained by Percoll gradient centrifugation as described above for monkey granulosa cells.

Human luteinizing granulosa cells were cultured in a manner similar to that described by others as a model of granulosa-lutein cells (Carrasco et al. 1997, Ristimaki et al. 1997, Chin et al. 2004). Briefly, cells were plated on fibronectin-coated culture ware in DMEM/F12 medium with supplements as described above for monkey granulosa cells with the addition of 10% fetal bovine serum (Atlanta Biologicals, Lawrenceville, GA) and cultured for up to 10 days. Cells assessed on Day 0 (day of plating) were allowed to attach to cell culture ware for 1 hour prior to study. At initiation of in vitro treatments, medium was removed and replaced with serum-free DMEM/F12 including all other supplements as described for monkey cells (above). Cells and media were harvested and stored as described above for monkey granulosa cells.

Quantitative RT-PCR (qPCR)

Levels of mRNA for PTGFR were assessed by qPCR using a Roche LightCycler (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN, USA). Total RNA was obtained from granulosa cells using Trizol reagent, treated with DNase and reverse transcribed as previously described (Duffy et al. 2005). PCR was performed using the FastStart DNA Master SYBR Green I kit (Roche) following manufacturer’s instructions. Primers were designed using LightCycler Probe Design software (Roche) based on the human or monkey sequences and span an intron to prevent undetected amplification of genomic DNA. Amplification of monkey cDNA included primers for PTGFR (forward: CCTGGTAATCACGGACT; reverse: GCACACACCACTTAACAT; Accession# DQ375448) and ACTB (β-actin; forward: ATCCGCAAAGACCTGT; reverse: GTCCGCTAGAAGCAT; Accession# AY765990). Amplification of human cDNA included primers for PTGFR (forward: GAGGTTGATGTCGAGCA; reverse: TTGTTCATACGTGTAGC; Accession# NM_000959) and ACTB (forward: ATCCGCAAAGACCTGT; reverse: GTCCGCTAGAAGCAT; Accession# NM_001101). PCR products were sequenced (Microchemical Core Facility, San Diego State University, CA) to confirm amplicon identity. At least 5 log dilutions of the sequenced PCR product were included in each assay and used to generate a standard curve. For each sample, the content of PTGFR and ACTB mRNA was determined in independent assays. No amplification was observed when cDNA was omitted. All data were expressed as the ratio of mRNA of interest to ACTB mRNA for each sample.

Immunofluorescent Detection of PTGFRs

After antigen retrieval with 10 mM sodium citrate (pH 6), slides were blocked with 5% non-immune goat serum (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) in PBS containing 0.1% Triton; all antibody solutions were made in this blocking buffer. Slides were incubated for 1 hour at room temperature either with primary antibody generated against PTGFR (5 μg/ml; Cayman) or no primary antibody, followed by incubation with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-rabbit secondary antibody (4 μg/ml; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). The slides were treated with 1% Sudan Black in 70% methanol to reduce autofluorescence and coverslipped in Vectashield medium containing propidium iodide (Vector). In some experiments, the anti-PTGFR primary antibody was pre-incubated with the blocking peptide at a 1:2 ratio prior to use in the primary antibody incubation step.

Conventional fluorescence images were obtained using an Olympus BX41 fluorescent microscope fitted with a DP70 digital camera and associated software (Olympus, Melville, NY). Confocal laser microscopy was performed using a Zeiss 510 laser scanning confocal microscope with LSM5 software for image acquisition (Carl Zeiss Inc., Thornwood, NY) using 488 nm excitation with a 505/550 band pass filter (green channel) and 543 nm excitation with a 560 nm long pass filter (red channel).

Western Blotting for PTGFR

Whole cells and luteal tissues were lysed on ice in PBS containing 0.5% sodium dodecyl sulfate and 0.1% Triton X-100. Cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions were prepared using the NE-PER extraction kit (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA). Protein concentration of each cell lysate and cell fraction was determined using the BCA method (Sigma). Lysates and fractions (25 μg protein) were mixed with sample buffer (0.03% bromophenol blue, 5% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 20% glycerol, 0.4M Tris, pH 6.8), heated to 95°C for 5 minutes, and loaded onto7.5% or 10% precast polyacrylamide Tris-HCl gels (BioRad, Hercules, CA). Proteins were transferred to PDVF membranes (Hybond-P, Amersham Biosciences, Buckinghamshire, UK) using the Trans Blot SD Semi-Dry Electrophoresis Transfer Cell (Bio-Rad). Membranes were blocked in 5% nonfat dry milk, 0.1% Tween-20 in PBS. Membranes were incubated for 1 hour at room temperature with the PTGFR polyclonal primary antibody (1:500 dilution, 1.0 μg/ml; Cayman) in blocking buffer, followed by exposure to goat anti-rabbit IgG-alkaline phosphatase-conjugated secondary antibody (1:7500 dilution, Applied Biosystems) for 1 hour at room temperature. Blots were washed in PBS with 0.3% Tween-20 between antibody incubations and before exposure to chemiluminescence reagents (CDP-Star, Applied Biosystems) for up to 5 min using Fuji medical imaging film (Fuji Photo Film Co, Tokyo, Japan). For each primary antibody, optimal exposure time was determined in preliminary experiments. Blots were then stripped and reprobed using a mouse anti-pan-actin primary monoclonal antibody (1:1000 dilution, Millipore) and an anti-mouse alkaline phosphatase-conjugated secondary antibody (1:10,000 dilution, Applied Biosystems). For examination of nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions, proteins were separated on 10% or 8–16% gradient precast gels (BioRad), blotted and blocked as described above, and also probed for tubulin (1:5000 dilution, mouse monoclonal, Sigma), sodium/potassium ATPase (Na/K ATPase (0.1 μg/ml, mouse monoclonal, Millipore), or histone H3 (1:1000 dilution, mouse monoclonal, Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers MA). Molecular weights (MW) of bands representing individual proteins were determined by comparison to pre-stained standards (Precision Plus Protein Standard Dual Color, BioRad).

Assay of cAMP and Progesterone

Spent culture media was assayed for cAMP by enzyme immunoassay (Cayman) following kit instructions for acetylation of samples; intra-assay and inter-assay coefficients of variation were 11.6% and 11.2%, respectively. Additional media samples were assessed for progesterone by enzyme immunoassay following kit instructions (Cayman); intra-assay and inter-assay coefficients of variation were 20.1% and 7.8%, respectively. All cAMP and progesterone levels were normalized to media volume of the culture well.

Data Analysis

All data were assessed for heterogeneity of variance using Bartlett’s test; data were log-transformed when Bartlett’s test yielded a significance of < 0.05. Data were then assessed by either paired t-test or ANOVA. When indicated, ANOVA with one repeated measure was used for cell culture experiments to reflect repeated use of cells from an individual women or monkey in all treatments in vitro. For ANOVA, post hoc analyses were performed using Duncan’s multiple range test or t-test. Statistical analyses were performed using StatPak v4.12 software (Northwest Analytical, Portland, OR). Data are presented as mean + SEM, and significance was assumed at p < 0.05.

RESULTS

PTGFRs in the Monkey Follicle

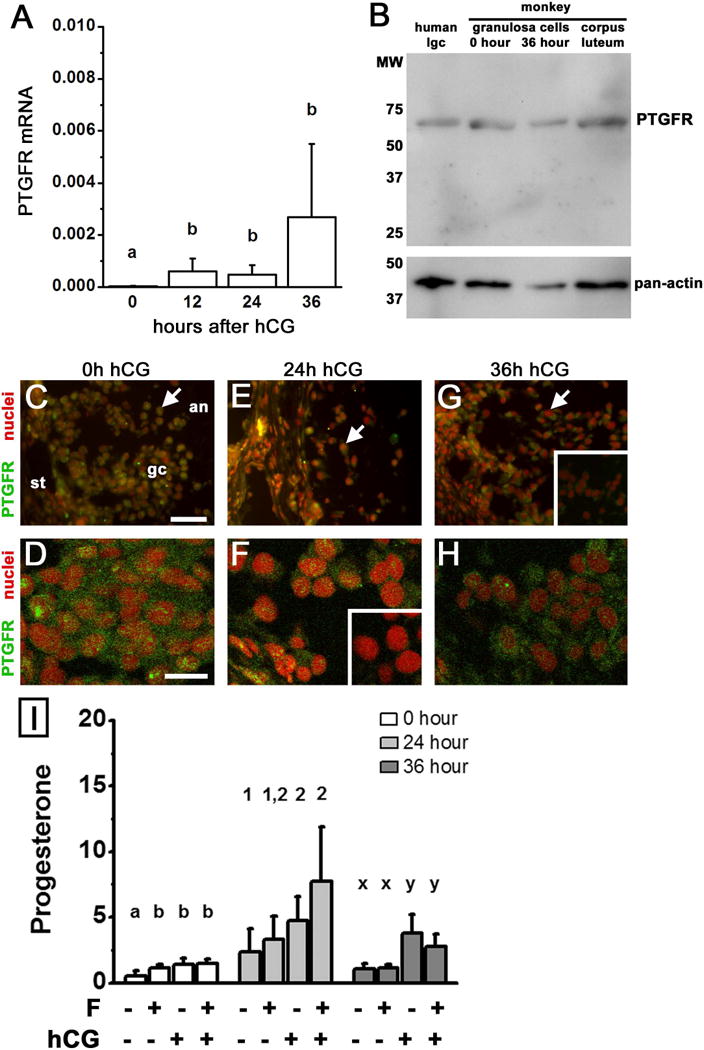

PTGFR receptors were expressed in monkey granulosa cells obtained throughout the ovulatory interval. Granulosa cell levels of PTGFR mRNA were low before hCG (0 hour) and increased 12–36 hours after administration of an ovulatory dose of hCG (Fig 1A), with ovulation anticipated 37–40 hours after hCG (Weick et al. 1973). PTGFR protein was detected by western blot in lysates of monkey granulosa cells obtained 0 and 36 hours after hCG as a single band of 67 MW (Fig 1B), consistent with previous reports of PTGFR protein in monkey and human tissues (Bogan et al. 2008a, Unlugedik et al. 2010). Conventional immunofluorescent microscopy showed PTGFR in ovarian tissues obtained throughout the ovulatory interval (Fig 1C,E,G) was observed predominately in the granulosa cells. Confocal laser microscopy showed that PTGFR protein was present throughout the granulosa cell and not preferentially in the plasma membrane or the perinuclear area (Fig 1D,F,H).

Figure 1.

PTGFR expression and function in monkey granulosa cells. Panel A. Levels of PTGFR mRNA in monkey granulosa cells obtained before (0) and 12, 24, and 36 hours after hCG administration in vivo were determined by qPCR and expressed relative to ACTB mRNA. Data are expressed as mean+SEM and were assessed by ANOVA, followed by Duncan’s post hoc test. Groups with no common superscripts are different, p<0.05; n=4–5 animals/group. Panel B. PTGFR protein was detected as a single band of 67 MW in monkey granulosa cells obtained before (0 hour) and 36 hours after hCG, and monkey corpus luteum (luteal day 10); human luteinizing granulosa cells (lgc) are included for size comparison. Pan-actin detection confirms protein loading; positions of MW size standards are shown on left. Panels C–H. PTGFR immunodetection (green) in monkey ovarian tissues obtained after controlled ovarian stimulation and before hCG (0 hour (h) C,D) or 24 h (E,F) and 36 h (G,H) after hCG. In Panels C, E, and G, follicles were imaged by conventional microscopy and are oriented as indicated in Panel C, with stroma (st) in the lower left, granulosa cells (gc) central, and follicle antrum (an) in upper right. Arrows indicate PTGFR detection throughout granulosa cells at all times examined. Panels C, E, and G use bar in Panel C = 25 μm. Panels D, F, and H show PTGFR dispersed throughout granulosa cells as imaged by confocal microscopy and use bar in Panel D = 100 μm. PTGFR detection was reduced when primary antibody was preabsorbed with the peptide used to generate the antibody (insets in Panels F and G). Nuclei are counterstained red. Images shown are representative of 3–4 monkeys. Panel I. Granulosa cells obtained at 0, 24, and 36 hours were cultured for 16 hours in the presence of no treatment, fluprostenol (F), hCG, or F+hCG. Progesterone levels (ng/ml media) were determined by EIA. Within each time of hCG exposure, data were assessed by ANOVA with 1 repeated measure, followed by Duncan’s post hoc test. Groups with no common superscripts are different, p<0.05; n=4–5 animals/time point.

To determine if PTGFRs in granulosa cells were functional, monkey granulosa cells obtained 0, 24, and 36 hours after hCG treatment in vivo were treated in vitro with the non-metabolizable PTGFR agonist fluprostenol, the LH-like hormone hCG, or fluprostenol+hCG; media progesterone was assessed. Progesterone levels in culture media were slightly but significantly elevated by exposure to fluprostenol in granulosa cells obtained at 0 hour hCG (Fig 1I). However, fluprostenol did not alter progesterone production by granulosa cells obtained 24 or 36 hours after hCG in vivo. hCG treatment in vitro increased progesterone at all times as expected; the addition of fluprostenol with hCG did not alter progesterone when compared to hCG only. Moreover, fluprostenol did not alter media cAMP (not shown) or intracellular calcium when determined as previously described ((Markosyan et al. 2006), not shown). Overall, PTGFRs in monkey granulosa cells were not localized to any specific region of the cell, and a selective PTGFR agonist did not alter progesterone production by granulosa cells obtained after the ovulatory stimulus.

PTGFRs in the Monkey Corpus Luteum

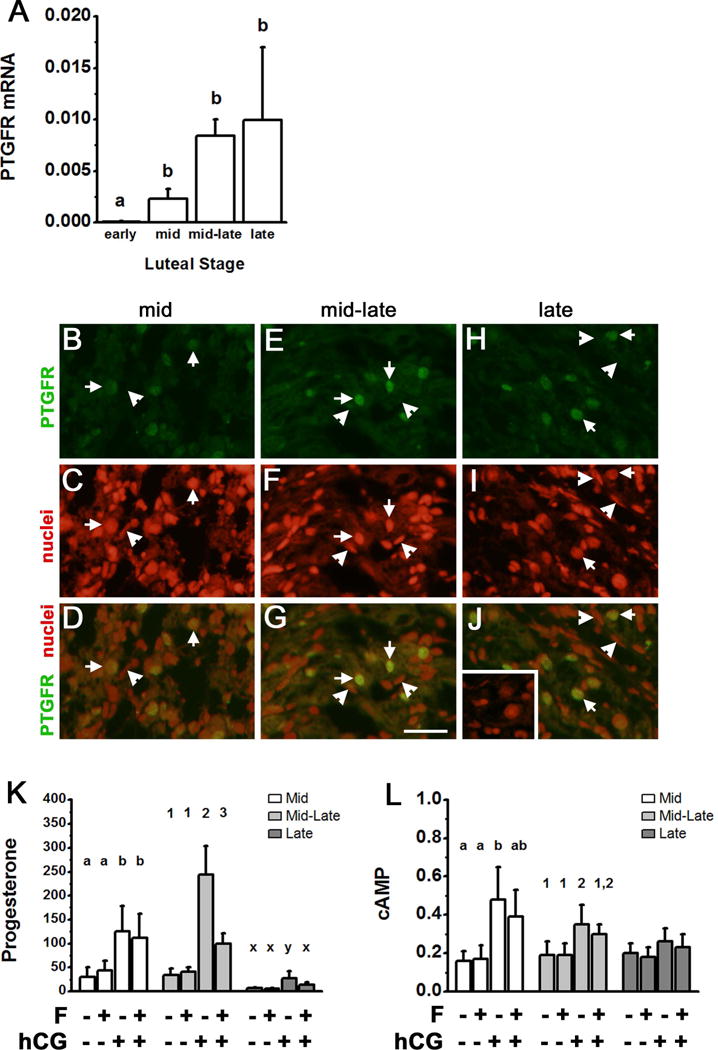

PTGFRs were expressed in the monkey corpus luteum throughout the luteal phase. PTGFR mRNA levels were lowest early in the luteal phase, higher at mid luteal phase, and remained elevated thereafter (Fig 2A). PTGFR protein in luteal tissue lysate was detected as a single band of 67 MW (Fig 1B). PTGFR protein was also detected in cells of the monkey corpus luteum by immunofluorescence and conventional microscopy. Granulosa-derived large luteal cells are easily identified by their characteristic large cytoplasmic area and large, round nuclei (Duffy et al. 1994). PTGFR was present throughout the large, granulosa-derived cells of luteal tissues obtained at mid luteal stage (Fig 2B–D). PTGFR protein was more concentrated in or near the nuclei of large luteal cells in tissues obtained at mid-late (Fig 2E–G) and late (Fig 2H–J) luteal stages. In luteal tissues obtained at the mid-late and late luteal stages, the majority of cells did not colocalize with PTGFR, indicating that other luteal cells types may have little or no PTGFR.

Figure 2.

PTGFR expression and function in monkey luteal cells. Panel A. Levels of PTGFR mRNA in monkey corpora lutea obtained during the early (days 3–4), mid (days 6–8), mid-late (days 10–11), and late (days 12–15) stages of the luteal phase were determined by qPCR and expressed relative to ACTB mRNA. Data are expressed as mean+SEM and were assessed by ANOVA, followed by Duncan’s post hoc test. Groups with no common superscripts are different, p<0.05; n=3–4 animals/group. Panels B–J. PTGFR immunodetection (green) in monkey luteal tissues obtained at the mid (B–D), mid-late (E–G), and late (H–J) luteal phases. Nuclei are counterstained red. Arrows indicate green fluorescence located in the perinuclear region of large luteal cells. Arrowheads indicate elongated nuclei of non-steroidogenic cells which do not colocalize with PTGFR. For Panels B–J, use bar in Panel G = 25 μm; images are representative of 3–4 monkeys/time point. Panels K–L. Dispersed luteal cells were cultured with no treatment, fluprostenol (F), hCG, or F+hCG for 4 hours; media was harvested for assay of progesterone (ng/ml media) and cAMP (pmol/ml media) by EIA. Within each stage of the luteal phase, data were assessed by ANOVA with 1 repeated measure, followed by Duncan’s post hoc test. Groups with no common superscripts are different, p<0.05; n=4–5 animals/luteal stage.

To determine if PTGFRs regulate luteal progesterone production, dispersed monkey luteal cells were cultured with fluprostenol or hCG (Fig 2K). In luteal cells obtained at mid luteal phase, hCG increased media progesterone, but fluprostenol had no effect on progesterone levels. Luteal cells obtained at mid-late luteal phase showed robust progesterone production in response to hCG. Although fluprostenol alone had no effect on progesterone production, fluprostenol reduced hCG-stimulated progesterone production by luteal cells obtained at mid-late luteal phase. Fluprostenol also decreased hCG-stimulated progesterone production in cells obtained at late luteal phase, although overall levels of progesterone were lower than those measured at mid or mid-late luteal phase. Previous studies suggest that PTGFR agonists may regulate progesterone production by reducing cAMP generation in response to LH receptor stimulation (Channing 1972, Abayasekara et al. 1993). However, fluprostenol had no effect on basal or hCG-stimulated cAMP levels (Fig 2L). Overall, luteal cells responded to PTGFR agonist stimulation to reduce progesterone production when PTGFRs were concentrated in the perinuclear area.

PTGFRs in Human Luteinizing Granulosa Cells In Vitro

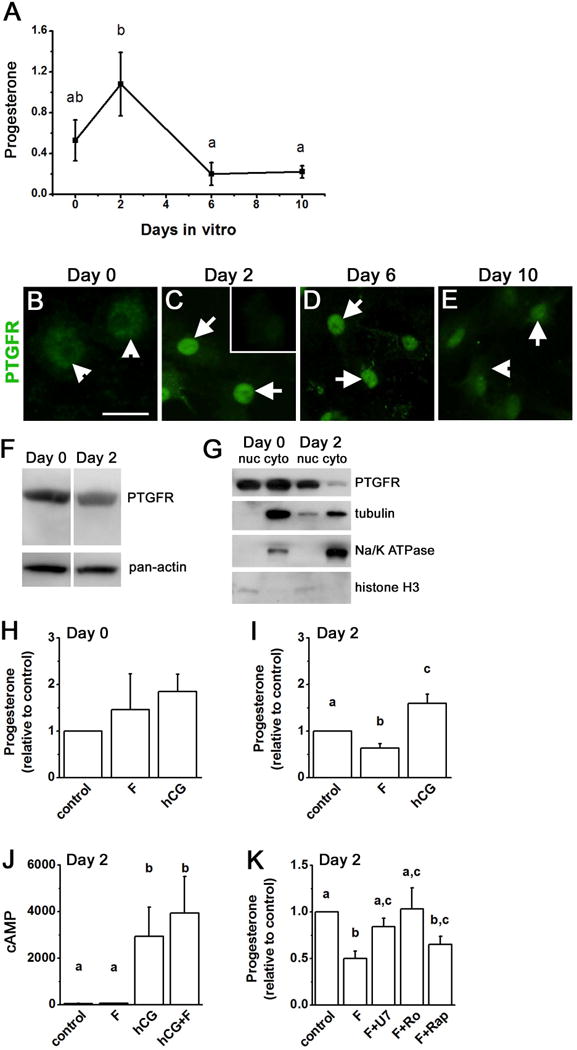

To examine the transition from the granulosa cell to the granulosa-lutein cell (large luteal cell) phenotype, a well-established human cell culture model was utilized (Carrasco et al. 1997, Ristimaki et al. 1997, Chin et al. 2004). Similar to these previous reports, human luteinizing granulosa cells produced progesterone when cultured in the absence of exogenous gonadotropin support. Media progesterone levels were modest on Day 0, peaked on Day 2, and declined to low levels on Days 6 and 10 of culture (Fig 3A). Changing progesterone levels in vitro parallel the pattern of changes in serum progesterone measured across the luteal phase in monkeys and women (Duffy et al. 1994, Groome et al. 1996).

Figure 3.

PTGFR expression and function in human luteinizing granulosa cells differentiating into granulosa-lutein cells in vitro. Panel A. Progesterone (μg/ml media) was assessed in cells after culture for 0, 2, 6, and 10 days. Media were changed on the day of culture indicated, and progesterone accumulation over 4 hours was assessed. Data were expressed as mean ± SEM and assessed by ANOVA with 1 repeated measure, followed by Duncan’s post hoc test. Groups with no common superscripts are different, p<0.05; n=4–6 women. Panels B–E. Immunodetection of PTGFR (green) in cells maintained in vitro 0 days (A), 2 days (B), 6 days (C), or 10 days (D); cells are not counterstained. Arrowheads indicates cytoplasmic detection of PTGFR; arrows indicate perinuclear PTGFR. Inset in Panel C shows reduced immunodetection when the PTGFR antibody was preabsorbed with the peptide used to generate the antibody. For Panels B–E, use bar in Panel B = 25 μm. Images shown are representative of 3–4 patients. Panels F–G. PTGFR (67 MW) detection by western blotting in total human luteinizing granulosa cell lysate (F) and in nuclear (nuc) and cytoplasmic (cyto) fractions of luteinizing granulosa cells (G) on Day 0 and Day 2 of culture (representative of n=3–4 women). Pan-actin detection (37 MW) detection in Panel F was performed on the same blot as PTGFR detection and confirms similar protein loading. Nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions were probed for tubulin (50 MW), Na/K ATPase (112 MW), and histone H3 (17 MW). Panels H–I. On Day 0 (H) or Day 2 (I–K) in vitro, fresh media containing fluprostenol (F), hCG or no treatment (control) were added to each well; media were harvested after 4 hours for assay of progesterone by EIA. Progesterone varied widely between women, so control for each woman was set at 1.0, and progesterone levels after hormone treatment are expressed relative to control levels. Panel J. Media from Day 2 cultures were assayed for cAMP by EIA (expressed as pmol cAMP/ml media). Panel K. On Day 2 in vitro, fresh media containing fluprostenol (F) alone or in combination with U73122 (F+U7), Ro31-3220 (F+Ro), or rapamycin (F+Rap) were added and collected 4 hours later for assay of progesterone. For Panels H–K, data are expressed as mean+SEM, n=4–6 patients per treatment or time point. Within each panel, data were assessed by ANOVA with 1 repeated measure, followed by Duncan’s post hoc test; data with no common superscripts are different, p<0.05.

PTGFR protein was detected by immunofluorescence and conventional microscopy as being dispersed throughout human luteinizing granulosa cells on the day of follicle aspiration (typically 34–36 hours after hCG), which is Day 0 of culture (Fig 3B) and comparable to monkey granulosa cells obtained 36 hours after hCG (Fig 1G,H). By Day 2 of culture, PTGFR protein was concentrated in the perinuclear region of the cells (Fig 3C). On Day 6, immunodetection of PTGFR was predominantly in the perinuclear region of these human cells (Fig 3D). Immunodetection of PTGFR was seen throughout the cells on Day 10 in vitro, with some cells retaining apparent concentration of PTGFR in the perinuclear region (Fig 3E). PTGFR was detected in a single band in cultured human luteinizing granulosa cells on Day 0 and Day 2 in vitro (Fig 3F). Total cellular levels of PTGFR receptor protein did not vary significantly over the culture period as determined by western blotting, although PTGFR levels were more variable on days 6 and 10 of culture (Fig 3F and not shown).

Additional studies were performed to determine if PTGFR was located primarily in cytoplasmic or nuclear fractions of cultured human luteinizing granulosa cells (Fig 3G). PTGFR was detected in both nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions of cells on Day 0 in vitro. On Day 2, PTGFR was more prominent in the nuclear fraction, with little PTGFR detected in the corresponding cytoplasmic fraction. Successful preparation of nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions was confirmed by detection of tubulin primarily in cytoplasmic fractions and histone H3 primarily in nuclear fractions of cells on Day 0 and Day 2 of culture. The plasma membrane protein Na/K ATPase was detected primarily or exclusively in the cytoplasmic fractions, confirming that nuclear fractions contained little, if any, plasma membrane proteins. Overall, these results confirm that PTGFRs were distributed throughout human luteinizing granulosa cells at the time of follicle aspiration but were located primarily in the perinuclear region after 2 days in vitro.

Further experiments focused on human luteinizing granulosa cells cultured for 2 days, when progesterone production peaks in this cell culture model, analogous to monkey luteal cells obtained at mid-late luteal phase (Fig 2K). To determine if cultured human luteinizing granulosa cells acquire the ability to respond to PTGFR stimulation as these cells transition from the granulosa cell to the luteal cell phenotype in vitro, media progesterone was measured after treatment with fluprostenol or hCG. On Day 0 in vitro, treatment with fluprostenol did not alter media progesterone levels (Fig 3H). On Day 2 in vitro, fluprostenol decreased media progesterone levels (Fig 3I). hCG increased media progesterone levels at Day 2, but not Day 0, similar to previous reports (Chin & Abayasekara 2004, Chin et al. 2004). Fluprostenol regulation of progesterone could not be attributed to alteration of cAMP as fluprostenol did not reduce control or hCG-stimulated cAMP levels after 2 days in vitro (Fig 3J). After 2 days in vitro, these cells responded to PTGFR stimulation with reduced progesterone production, consistent with induction of luteolysis.

As members of the 7-transmembrane superfamily of receptors, PTGFR receptors are thought to couple with G proteins to regulate intracellular signaling components including PLC, PKC, and mTOR (Houmard et al. 1992, Abayasekara et al. 1993, Carrasco et al. 1997, Ristimaki et al. 1997, Arvisais et al. 2006). Human luteinizing granulosa cells were maintained in vitro for 2 days, then treated for 4 hours with fluprostenol or fluprostenol in combination with the PLC inhibitor U73122, the PKC inhibitor Ro31-3220, or the mTOR inhibitor rapamycin (Fig 3K). Fluprostenol treatment reduced progesterone levels when compared to control cultures; this reduction in progesterone was blocked by the PLC inhibitor U73122 and the PKC inhibitor Ro31-3220 but not the mTOR inhibitor rapamycin.

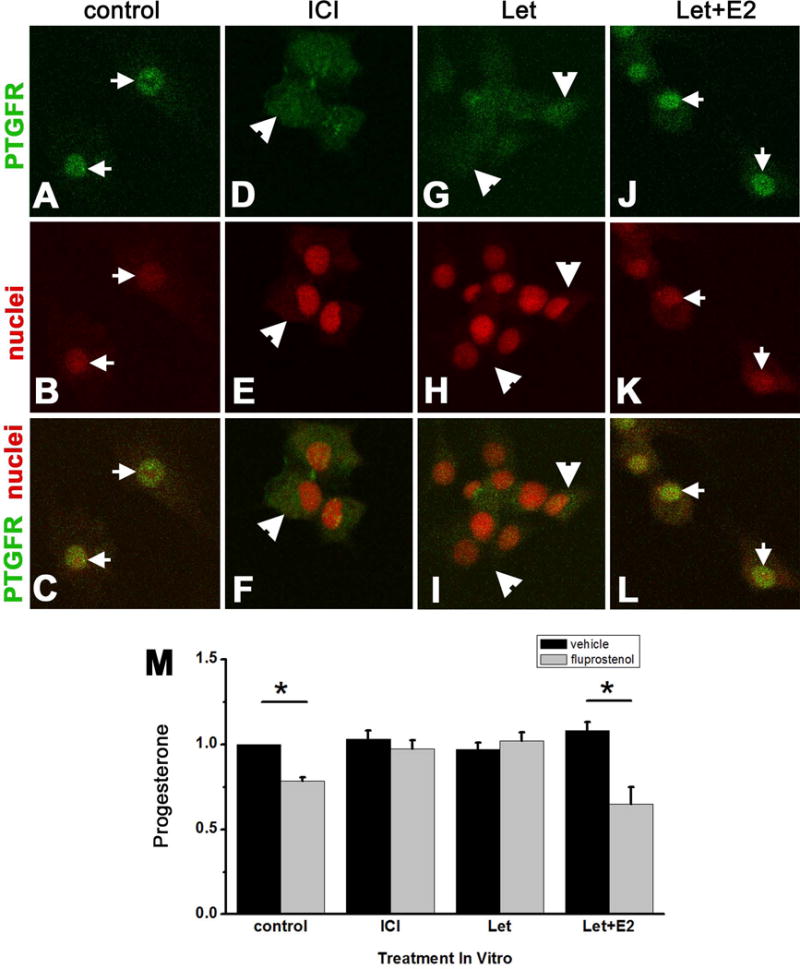

Modulation of PTGFR Location in Human Luteinizing Granulosa Cells

Additional studies were performed to determine if the proposed luteolysins estrogen, progesterone, and PGF2α modulated PTGFR location within human luteinizing granulosa cells after 2 days in vitro. Cells cultured with vehicle only but exposed to endogenously-produced estrogen (approximately 0.1 μM (Chang et al. 2013); control) showed green immunofluorescence reflecting PTGFR concentrated in the perinuclear region as imaged by confocal microscopy (Fig 4A–C). To determine if estrogen receptors were involved in the relocation of PTGFRs, cells were treated with the estrogen receptor antagonist ICI 182,780 to block the action of endogenously-produced estrogen. Treatment with ICI 182,780 yielded less apparent PTGFR immunodetection in the perinuclear region (Fig 4D–F) when compared with control cells. In addition, an ablate-and-replace approach was used to confirm the effect of endogenous estrogen on PTGFR location. Treatment with the aromatase inhibitor letrozole to inhibit estrogen synthesis yielded PTGFR immunodetection throughout the cell, with no apparent concentration in the vicinity of the nucleus (Fig 4G–I). In contrast, treatment with letrozole+estradiol replacement yielded perinuclear PTGFR localization (Fig 4J–L).

Figure 4.

Estrogen promotes PTGFR localization to the perinuclear region and PTGFR function in cultured human luteinizing granulosa cells. Cells were cultured for 2 days with vehicle (control), ICI 182,780 (ICI), letrozole (Let), or letrozole and estradiol (Let+E2). Panels A–L. PTGFR immunodetection (green), nuclear counterstain (red), and merged images are shown. Arrows indicate perinuclear location of PTGFR; arrowheads indicate PTGFR dispersed throughout cells. Images were obtained with confocal microscopy and are representative of n=3 women. Panel M. Cells were cultured for 2 days with vehicle (control), ICI, Let, and Let+E2 as described above; media were replaced and cells were treated for 4 hours with media containing vehicle or fluprostenol before assay for progesterone by EIA. Progesterone levels after hormone treatment were expressed relative to control levels, which was set at 1.0 for each woman. Fluprostenol reduced media progesterone (asterisks) in control and Let+E2-treated cells as assessed by paired t-test, p<0.05. Data are expressed as mean+SEM, n=4 women.

To determine if perinuclear location of PTGFR correlated with the ability of PGF2α to modulate progesterone production, human luteinizing granulosa cells were treated with ICI 182,780, letrozole, or letrozole+estradiol, for 2 days in vitro. Media were removed, and cells from each treatment group received fresh media with vehicle or fluprostenol for 4 hours prior to harvest of media for progesterone assay (Fig 4M). In cells receiving no treatment but exposed to endogenously-produced estrogen during 2 days in vitro (control), fluprostenol decreased progesterone production, consistent with our findings in Fig 3I. Cells treated with the estrogen receptor antagonist ICI 182,780 for 2 days in vitro did not respond to fluprostenol with altered progesterone. Cells treated with estrogen synthesis inhibitor letrozole for 2 days in vitro also did not respond to fluprostenol with altered progesterone production. In contrast, treatment with letrozole+estradiol replacement for 2 days in vitro yielded decreased progesterone in response to fluprostenol treatment. Therefore, only cells exposed to estrogen stimulation during 2 days in vitro (i.e., control and letrozole+estradiol treated cells) responded to fluprostenol with decreased progesterone production.

Progesterone and prostaglandins were not required for the relocation of PTGFRs in human luteinizing granulosa cells. Treatment with either the 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase inhibitor trilostane to block progesterone production or trilostane+progesterone replacement for 2 days in vitro yielded PTGFRs located in the perinuclear area, similar to control cells (n=4; data not shown). PTGFRs were also located in the perinuclear region of cells treated with the prostaglandin synthesis inhibitor indomethacin or indomethacin+ fluprostenol for 2 days in vitro (n=3; data not shown).

DISCUSSION

PGF2α has been proposed as a key regulator of ovarian function in many species, including monkeys and humans. The observation that follicular PGF2α increases just before ovulation (Lumsden et al. 1986, Murdoch et al. 1986, Sirois & Dore 1997, Duffy & Stouffer 2001, Sayasith et al. 2006, Dozier et al. 2008), coupled with PTGFR expression in follicular granulosa cells (Carrasco et al. 1997, Bridges & Fortune 2007, Xu et al. 2011), has led to the suggestion that PGF2α may serve as a local mediator of ovulatory events. While systemic administration of PGF2α can reverse indomethacin-induced inhibition of ovulation (Wallach et al. 1975, Murdoch et al. 1986, Sogn et al. 1987, Janson et al. 1988), disruption of PTGFR expression in mice did not prevent ovulation (Sugimoto et al. 1997). To date, functional PTGFRs have not been reported in follicular granulosa cells. Taken together, these findings do not support a role for PGF2α in ovulatory events.

PGF2α has also been suggested as a regulator of primate luteolysis. It is well established that PGF2α of uterine origin acts at the corpus luteum to initiate luteolysis in domestic animal species (Niswender & Nett 1994). A role for PGF2α to promote luteolysis in primate species is more controversial. Human and monkey luteal tissues synthesize PGF2α (Auletta et al. 1995, Ottander et al. 1999) and express PTGFR mRNA and protein (Carrasco et al. 1997, Ristimaki et al. 1997, Ottander et al. 1999, Bogan et al. 2008b, Xu et al. 2011). Luteal cells express PTGFRs capable of signal transduction in many species (Davis et al. 1987, Carrasco et al. 1997, Ristimaki et al. 1997, Arvisais et al. 2006), including monkeys (Houmard et al. 1992). Intraluteal or systemic injection of PGF2α caused a decline of serum progesterone and shortened the luteal phase in women and monkeys (Bennegard et al. 1991, Auletta et al. 1995). Importantly, PGF2α acts directly at luteal cells to decrease progesterone production. As previously shown (Stouffer et al. 1979) and confirmed with more precise timing of tissue collection in the present study, PGF2α decreased hCG-stimulated (but not basal) progesterone production by luteal cells obtained from monkeys at mid-late or late luteal stages, when the corpus luteum is sensitive to luteolytic stimuli in vivo. Decreased progesterone production is the hallmark of functional luteolysis, so collectively these findings are consistent with the concept that ovarian PGF2α acts via PTGFRs as a part of the luteolytic process in primates.

Acquisition of luteal cell sensitivity to PTGFR ligands correlates with relocation of the PTGFR from the cytoplasm to the perinuclear area of primate luteal cells. In the present studies, monkey granulosa cells from ovulatory follicles, monkey luteal cells, and human luteinizing granulosa cells in vitro all expressed PTGFR protein. PTGFRs were distributed throughout monkey granulosa cells. In contrast, PTGFRs were observed primarily in the perinuclear area of mature monkey granulosa-lutein cells. In the human luteinizing granulosa cell model of luteal cell differentiation, PTGFRs were distributed throughout the cells at the start of culture (Day 0), with perinuclear PTGFRs observed on Day 2 in vitro. This relocation of PTGFRs is consistent with observations made in monkey ovarian cells. PTGFRs were distributed throughout human luteinizing granulosa cells on the day of follicle aspiration (about 36 hours after the ovulatory gonadotropin stimulus), similar to monkey granulosa cells obtained 36 hours after hCG. In contrast, PTGFRs were observed in the perinuclear region of human luteinizing granulosa cells after several days in vitro, similar to mature monkey luteal cells. Most importantly, PTGFRs were consistently located in the perinuclear area when cells were sensitive to PTGFR stimulation to reduce progesterone production.

G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), including PTGFRs, are often located in the plasma membrane and respond to ligands located outside the cell. Accumulating evidence suggests that functional GPCRs can also be located in the nuclear envelope or perinuclear membranes. While the specific mechanisms which direct nuclear localization of GPCRs remain to be established, structural components of the GPCR referred to as nuclear localization signals or endoplasmic retention sequences have been proposed (Marrache et al. 2002, Lee et al. 2004). However, such sequences remain to be identified for the majority of GPCRs, including PTGFR. Nuclear membranes do contain components of signal transduction systems for GPCRs, such as G proteins, adenylyl cyclase, PKA, PLC and PKC; isolated nuclei can respond to ligand binding with generation of intracellular signals (reviewed in (Gobell et al. 2006)). Our studies in cultured human luteinizing granulosa cells show that stimulation of perinuclear PTGFRs regulate progesterone production via the PLC/PKC signaling pathway. This is consistent with previous reports in which stimulation of PTGFR by PGF2α led to increase in the accumulation of inositol trisphosphate (IP3), elevated intracellular calcium, increased PKC activity, and activation of MAP kinases in luteal cells (Davis et al. 1987, Abayasekara et al. 1993, Chen et al. 1998, Tai et al. 2001, Hou et al. 2008). These observations are consistent with the concept that PTGFRs can activate G protein-coupled signal transduction pathways when located in or near the nucleus.

Despite decades of interest, the key factor which initiates primate luteolysis remains elusive. Several hypotheses have been put forward. Decreasing LH pulse frequency or declining luteal cell sensitivity to LH late in the luteal phase may provide inadequate gonadotropin support for progesterone synthesis (Ellinwood et al. 1984, Hutchison et al. 1986, Duffy et al. 1999b). Alternatively, because the ability of luteal cells to produce progesterone declines as the corpus luteum ages, it has been suggested that reduced substrate availability, decreased activity of steroidogenic enzymes, or declining luteal cell sensitivity to gonadotropin may be the cause of luteolysis (reviewed in (Stouffer et al. 1996)). Progesterone has also been proposed as a key luteotropin, with declining progesterone itself serving as the initiator of luteolysis (reviewed in (Rothchild 1981)). Estrogen has been proposed as a luteolytic signal, but the specific target of estrogen action in experimental models has been disputed (Karsch & Sutton 1976, Hutchison et al. 1987). Prostaglandins, and in particular PGF2α, can modulate progesterone production by luteal cells, but the hypothesis that PGF2α initiates primate luteolysis in vivo remains unproven. The present study provides support for a novel hypothesis that unites two of these ideas: estrogen regulates relocation of PTGFRs to the perinuclear area, an event which enhances luteal cell sensitivity to PGF2α as an early step in luteolysis.

The role of estrogen in luteolysis has been debated for decades. Cells of the corpus luteum express estrogen receptors. ERα, ERβ, and the plasma membrane estrogen receptor GPR30 have been reported in luteal tissues of rodents, domestic animals, monkeys, and women, with most studies suggesting that ERβ predominates (Duffy et al. 2000, Hosokawa et al. 2001, Diaz & Wiltbank 2004, Shibaya et al. 2007, Wang et al. 2007, van den Driesche et al. 2008, Hazell et al. 2009, Maranesi et al. 2010). Additional studies have shown that estrogen acts directly at luteal cells to regulate functions as diverse as apoptosis, steroidogenesis, and inhibin production (Diaz & Wiltbank 2004, van den Driesche et al. 2008). While expression of enzymes involved in estrogen synthesis increases as luteolysis approaches (Benyo et al. 1993, Diaz & Wiltbank 2004), it is widely accepted that tissue estrogen concentrations within the corpus luteum are receptor-saturating throughout the luteal phase (Duffy et al. 1999a). High serum estrogen resulting from the natural preovulatory rise, gonadotropin treatments to stimulate multiple follicles, or systemic administration during the early luteal phase in monkeys and women does not prevent formation of the corpus luteum or promote premature luteolysis (Weick et al. 1973, Schoonmaker et al. 1981, Hibbert et al. 1996, Beckers et al. 2006). Exogenous estrogen did elicit premature luteolysis in monkeys when administered at mid/mid-late luteal phase (Schoonmaker et al. 1981). In subsequent studies, it was demonstrated that estrogen acts via the hypothalamus to decrease gonadotropin support for the corpus luteum and thereby promote luteolysis (Hutchison et al. 1987). However, estrogen implants placed in the corpus luteum itself caused luteolysis, while estrogen delivered systemically or within the contralateral ovary did not, providing strong support for the hypothesis that estrogen can act locally within the corpus luteum to promote luteolysis (Karsch & Sutton 1976). So, while estrogen can shorten luteal life span by inhibiting gonadotropin synthesis/release, well-controlled studies also support a role for estrogen action locally within the corpus luteum to promote luteolysis.

In the present study, estrogen promoted movement of PTGFRs to the perinuclear area of luteal cells. Use of an ablate-and-replace approach, in parallel with the estrogen receptor antagonist ICI 182,780 (Howell et al. 2000, Thomas et al. 2005), confirmed that PTGFR movement is dependent on both estrogen and estrogen receptors. It is important to note that high estrogen levels within granulosa cells of the follicle in vivo did not stimulate PTGFR concentration near the nucleus. Luteal cells may need to mature sufficiently to be receptive to this luteolytic stimulus, and additional experiments would be required to identify the conditions which constitute this receptive environment. One aspect of receptivity may be the ability of estrogen to act via estrogen receptors to stimulate the movement of PTGFRs within granulosa-lutein cells, placing PTGFRs in proximity to the G-protein-coupled apparatus necessary for signal transduction. The findings presented in this report unite two long-standing hypotheses to suggest that estrogen and PGF2α produced within the corpus luteum are both essential to initiate timely luteolysis during the menstrual cycle in primates.

Acknowledgments

The Authors would like to acknowledge the assistance of the Jones Institute for Reproductive Medicine at EVMS for providing human luteinizing granulosa cells. Recombinant human gonadotropins and GnRH antagonists were generously provided by Merck & Co., Whitehouse Station NJ and Serono Reproductive Biology Institute, Rockland MA. Novartis Pharma (Basel, Switzerland) generously provided the aromatase inhibitor letrozole. Stegram Pharmaceuticals (Sussex, UK) generously provided the 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase inhibitor trilostane.

Footnotes

Funding was provided by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (HD054691 and HD071875 to DMD).

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Contributor Information

Soon Ok Kim, Email: kims@evms.edu.

Nune Markosyan, Email: nune@mail.med.upenn.edu.

Gerald J. Pepe, Email: pepegj@evms.edu.

References

- Abayasekara DRE, Michael AE, Webley GE, Flint APF. Mode of action of prostaglandin F2α in human luteinized granulosa cells: role of protein kinase C. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology. 1993;97:81–91. doi: 10.1016/0303-7207(93)90213-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arvisais EW, Romanelli A, Hou X, Davis JS. AKT-independent phosphorylation of TSC2 and activation of mTOR and ribosomal protein S6 kinase signaling by prostaglandin F2α. 2006;281:26904–26913. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605371200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auletta FJ, Flint APF. Mechanisms controlling corpus luteum function in sheep, cows, nonhuman primates, and women especially in relation to the time of luteolysis. Endocrine Reviews. 1988;9:88–105. doi: 10.1210/edrv-9-1-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auletta FJ, Kelm LB, Schofield MJ. Responsiveness of the corpus luteum of the rhesus monkey (Macaca mulatta) to gonadotrophin in vitro during spontaneous and prostaglandin F2α-induced luteolysis. Journal of Reproduction and Fertility. 1995;103:107–113. doi: 10.1530/jrf.0.1030107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckers NGM, Platteau P, Eijkemans MJ, Macklon NS, de Jong FH, Devroey P, Fauser BCJM. The early luteal phase administration of estrogen and progesterone does not induce premature luteolysis in normo-ovulatory women. European Journal of Endocrinology. 2006;155:355–363. doi: 10.1530/eje.1.02199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennegard B, Hahlin M, Wennberg E, Noren H. Local luteolytic effect of prostaglandin F2 alpha in the human corpus luteum. Fertility and Sterility. 1991;56:1070–1076. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benyo DF, Little-Ihrig L, Zeleznik AJ. Noncoordinated expression of luteal cell messenger ribonucleic acids during human chorionic gonadotropin stimulation of the primate corpus luteum. Endocrinology. 1993;133:699–704. doi: 10.1210/endo.133.2.8344208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogan RL, Murphy MJ, Stouffer RL, Hennebold JD. Prostaglandin synthesis, metabolism, and signaling potential in the rhesus macaque corpus luteum throughout the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle. Endocrinology. 2008a;149:5861–5871. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-0500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogan RL, Murphy MJ, Stouffer RL, Hennebold JD. Systematic determination of differential gene expression in the primate corpus luteum during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle. Molecular Endocrinology. 2008b;22:1260–1273. doi: 10.1210/me.2007-0484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bridges PJ, Fortune JE. Regulation, action and transport of prostaglandins during the periovulatory period in cattle. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology. 2007;263:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrasco MP, Asboth G, Phaneuf S, Lopez Bernal A. Activation of the prostaglandin FP receptor in human granulosa cell. Journal of Reproduction and Fertility. 1997;111:309–317. doi: 10.1530/jrf.0.1110309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaffin CL, Hess DL, Stouffer RL. Dynamics of periovulatory steroidogenesis in the rhesus monkey follicle after controlled ovarian stimulation. Human Reproduction. 1999a;14:642–649. doi: 10.1093/humrep/14.3.642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaffin CL, Stouffer RL, Duffy DM. Gonadotropin and steroid regulation of steroid receptor and aryl hydrocarbon receptor mRNA in macaque granulosa cells during the periovulatory interval. Endocrinology. 1999b;140:4753–4760. doi: 10.1210/endo.140.10.7056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang HM, Klausen C, Leung PCK. Antimullerian hormone inhibits follicle-stimulating hormone-induced adenylyl cyclase activation, aromatase expression, and estradiol production in human granulosa-lutein cells. Fertility and Sterility. 2013;100:585–592. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Channing CP. Stimulatory effects of prostaglandins upon luteinization of rhesus monkey granulosa cell cultures. Prostaglandins. 1972;2:331–349. doi: 10.1016/s0090-6980(72)80042-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen DB, Westfall SD, Fong HW, Roberson MS, Davis JS. Prostaglandin F2alpha stimulates the Raf/MEK1/mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling cascade in bovine luteal cells. Endocrinology. 1998;139:3876–3885. doi: 10.1210/endo.139.9.6197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chin EC, Abayasekara DR. Progersterone secretion by luteinizing human granulosa cells: a possible cAMP-dependent but PKA-independent mechanism involved in its regulation. Journal of Endocrinology. 2004;183:51–60. doi: 10.1677/joe.1.05550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chin EC, Harris TE, Abayasekara DRE. Changes in cAMP-dependent protein kinase (PKA) and progesterone secretion in luteinizing human granulosa cells. Journal of Endocrinology. 2004;183:39–50. doi: 10.1677/joe.1.05549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis JS, Weakland LL, Weiland DA, Farese RV, West LA. Prostaglandin F2 alpha stimulates phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate hydrolysis and mobilizes intracellular Ca2+ in bovine luteal cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA. 1987;84:3728–3732. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.11.3728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz FJ, Wiltbank MC. Acquisition of luteolytic capacity: changes in prostaglandin F2a regulation of steroid hormone receptors and estradiol biosynthesis in pig corpora lutea. Biology of Reproduction. 2004;70:1333–1339. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.103.020461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dozier BL, Watanabe K, Duffy DM. Two pathways for prostaglandin F2α synthesis by the primate periovulatory follicle. Reproduction. 2008;136:53–63. doi: 10.1530/REP-07-0514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy DM, Abdelgadir SE, Stott KR, Resko JA, Stouffer RL, Zelinski-Wooten MB. Androgen receptor mRNA expression in the rhesus monkey ovary. Endocrine. 1999a;11:23–30. doi: 10.1385/ENDO:11:1:23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy DM, Chaffin CL, Stouffer RL. Expression of estrogen receptor α and β in the rhesus monkey corpus luteum during the menstrual cycle: Regulation by luteinizing hormone and progesterone. Endocrinology. 2000;141:1711–1717. doi: 10.1210/endo.141.5.7477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy DM, Hess DL, Stouffer RL. Acute administration of a 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase inhibitor to rhesus monkeys at the midluteal phase of the menstrual cycle: Evidence for possible autocrine regulation of the primate corpus luteum by progesterone. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 1994;79:1587–1594. doi: 10.1210/jcem.79.6.7989460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy DM, Seachord CL, Dozier BL. Microsomal prostaglandin E synthase-1 (mPGES-1) is the primary form of PGES expressed by the primate periovulatory follicle. Human Reproduction. 2005;20:1485–1492. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy DM, Stewart DR, Stouffer RL. Titrating luteinizing hormone replacement to sustain the structure and function of the corpus luteum after gonadotropin-releasing hormone antagonist treatment in rhesus monkeys. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 1999b;84:342–349. doi: 10.1210/jcem.84.1.5362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy DM, Stouffer RL. Progesterone receptor messenger ribonucleic acid in the primate corpus luteum during the menstrual cycle: Possible regulation by progesterone. Endocrinology. 1995;136:1869–1876. doi: 10.1210/endo.136.5.7720632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy DM, Stouffer RL. The ovulatory gonadotrophin surge stimulates cyclooxygenase expression and prostaglandin production by the monkey follicle. Molecular Human Reproduction. 2001;7:731–739. doi: 10.1093/molehr/7.8.731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellinwood WE, Norman RL, Spies HG. Changing frequency of pulsatile luteinizing hormone and progesterone secretion during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle of rhesus monkeys. Biology of Reproduction. 1984;31:714–722. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod31.4.714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gobell F, Fortier A, Zhu T, Bossolasco M, Leduc M, Grandbois M, Heveker N, Bkaily G, Chemtob S, Barbaz D. G-protein-coupled receptors signalling at the cell nucleus: an emerging paradigm. Canadian Journal of Physiology and Pharmacology. 2006;84:287–297. doi: 10.1139/y05-127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groome NP, Illingworth PJ, O’Brien M, Pai R, Rodger FE, Maher JP, McNeilly AS. Measurement of dimeric inhibin B throughout the human menstrual cycle. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 1996;81:1401–1405. doi: 10.1210/jcem.81.4.8636341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazell GGJ, Yao ST, Roper JA, Prossnitz ER, O’Carroll A-M, Lolait SJ. Localization of GPR30, a novel G protein-coupled oestrogen receptor, suggests multiple functions in rodent brain and peripheral tissues. Journal of Endocrinology. 2009;202:223–236. doi: 10.1677/JOE-09-0066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hibbert ML, Stouffer RL, Wolf DP, Zelinski-Wooten MB. Midcycle administration of a progesterone synthesis inhibitor prevents ovulation in primates. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA. 1996;93:1897–1901. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.5.1897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosokawa K, Ottander U, Wahlberg P, Ny T, Cajander S, Olofsson IJ. Dominant expression and distribution of oestrogen receptor β over oestrogen receptor α in the human corpus luteum. Molecular Human Reproduction. 2001;7:137–145. doi: 10.1093/molehr/7.2.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou X, Arvisais EW, Jiang C, Chen DB, Roy SK, Pate JL, Hansen TR, Rueda BR, Davis JS. Prostaglandin F2alpha stimulates the expression and secretion of transforming growth factor B1 via induction of the early growth response 1 gene (EGR1) in the bovine corpus luteum. Molecular Endocrinology. 2008;22:403–414. doi: 10.1210/me.2007-0272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houmard BS, Guan Z, Stokes BT, Ottobre JS. Activation of the phosphatidylinositol pathway in the primate corpus luteum by prostaglandin F2 alpha. Endocrinology. 1992;131:743–748. doi: 10.1210/endo.131.2.1639020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell A, Osborne CK, Morris C, Wakeling AE. ICI 182,780 (Faslodex): development of a novel, “pure” antiestrogen. Cancer. 2000;89:817–825. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20000815)89:4<817::aid-cncr14>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchison JS, Kubik CJ, Nelson PB, Zeleznik AJ. Estrogen induces premature luteal regression in rhesus monkeys during spontaneous menstrual cycles, but not in cycles driven by exogenous gonadotropin-releasing hormone. Endocrinology. 1987;121:466–474. doi: 10.1210/endo-121-2-466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchison JS, Nelson PB, Zeleznik AJ. Effects of different gonadotropin pulse frequencies on corpus luteum function during the menstrual cycle of rhesus monkeys. Endocrinology. 1986;119:1964–1971. doi: 10.1210/endo-119-5-1964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janson PO, Brannstrom M, Holmes PV, Sogn J. Studies on the mechansim of ovulation using the model of the isolated ovary. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1988;541:22–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1988.tb22238.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karsch FJ, Sutton GP. An intra-ovarian site for the luteolytic action of estrogen in the rhesus monkey. Endocrinology. 1976;98:553–561. doi: 10.1210/endo-98-3-553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee DK, Lanca AJ, Cheng R, Nguyen T, Ji XD, Gobeil FJ, Chemtob S, George SR, O’Dowd BF. Agonist-independent nuclear localization of the apelin, angiotensin AT1, and bradykinin B2 receptors. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2004;279:7901–7908. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306377200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lumsden MA, Kelly RW, Templeton AA, Van Look PFA, Swanston IA, Baird DT. Changes in the concentration of prostaglandins in preovulatory human follicles after administration of hCG. Journal of Reproduction and Fertility. 1986;77:119–124. doi: 10.1530/jrf.0.0770119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maranesi M, Zerani M, Lilli L, Dall’Aglio C, Brecchia G, Gobbetti A, Boiti C. Expressiopn of luteal estrogen receptor, interleukin-1, and apoptosis-associated genes after PGF2a administration in rabbits at different stages of psuedopregnancy. Domestic Animal Endocrinology. 2010;39:116–130. doi: 10.1016/j.domaniend.2010.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markosyan N, Dozier BL, Lattanzio FA, Duffy DM. Primate granulosa cell response via prostaglandin E2 receptors increases late in the periovulatory interval. Biology of Reproduction. 2006;75:868–876. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.106.053769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marrache AM, Gobeil FJ, Bernier SG, Stankova J, Rola-Pleszczynski M, Choufani S, Bkaily G, Bourdeau A, Sirois MG, Vazquez-Tello A, Fan L, Joyal J-S, Filep JG, Varma DR, Ribeiro-Da-Silva A, Chemtob S. Proinflammatory gene induction by platelet-activating factor mediated via its cognate nuclear receptor. J Immunol. 2002;169:6474–6481. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.11.6474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murdoch WJ, Peterson TA, Van Kirk EA, Vincent DL, Inskeep EK. Interactive roles of progesterone, prostaglandins, and collagenase in the ovulatory mechanism of the ewe. Biology of Reproduction. 1986;35:1187–1194. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod35.5.1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niswender GD, Nett TM. Corpus luteum and its control in infraprimate species. The Physiology of Reproduction. 1994:781–816. [Google Scholar]

- Ottander U, Leung CHB, Olofsson JI. Functional evidence for divergent receptor activation mechanisms of luteotrophic and luteolytic events in the human corpus luteum. Molecular Human Reproduction. 1999;5:391–395. doi: 10.1093/molehr/5.5.391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patwardhan VV, Lanthier A. Prostaglandins PGE and PGF in human ovarian follicles: Endogenous contents and in vitro formation by theca and granulosa cells. Acta Endocrinologica. 1981;97:543–550. doi: 10.1530/acta.0.0970543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ristimaki A, Jaatinen R, Ritvos O. Regulation of prostaglandin F2α receptor expression in cultured human granulosa-luteal cells. Endocrinology. 1997;138:191–195. doi: 10.1210/endo.138.1.4891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothchild I. The regulation of the mammalian corpus luteum. Recent Progress in Hormone Research. 1981;37:183–298. doi: 10.1016/b978-0-12-571137-1.50009-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders SL, Stouffer RL, Brannian JD. Androgen production by monkey luteal cell subpopulations at different stages of the menstrual cycle. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 1996;81:591–596. doi: 10.1210/jcem.81.2.8636273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayasith K, Bouchard N, Dore M, Sirois J. Molecular cloning and gonadotropin-dependent regulation of equine prostaglandin F2α receptor in ovarian follicles during the ovulatory process in vivo. Prostaglandins and Other Lipid Mediators. 2006;80:81–92. doi: 10.1016/j.prostaglandins.2006.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoonmaker JN, Victery W, Karsch FJ. A receptive period for estradiol-induced luteolysis in the rhesus monkey. Endocrinology. 1981;108:1874–1877. doi: 10.1210/endo-108-5-1874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seachord CL, VandeVoort CA, Duffy DM. Adipose-differentiation related protein: a gonadotropin- and prostaglandin-regulated protein in primate periovulatory follicles. Biology of Reproduction. 2005;72:1305–1314. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.104.037523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibaya M, Matsuda A, Hojo T, Acosta TJ, Okuda K. Expression of estrogen receptors in the bovine corpus luteum: cyclic changes an deffects of prostaglandin F2a and cytokines. Journal of Reproduction and Development. 2007;53:1059–1068. doi: 10.1262/jrd.19065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sirois J, Dore M. The late induction of prostaglandin G/H synthase-2 in equine preovulatory follicles supports its role as a determinant of the ovulatory process. Endocrinology. 1997;138:4427–4434. doi: 10.1210/endo.138.10.5462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sogn JH, Curry TE, Jr, Brannstrom M, Lemaire WJ, Koos RD, Papkoff H, Janson PO. Inhibition of follicle-stimulating hormone-induced ovulation by indomethacin in the perfused rat ovary. Biology of Reproduction. 1987;36:536–542. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod36.3.536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stouffer RL. Endocrine, paracrine, and autocrine regulators of the macaque corpus luteum. Signaling mechanisms and gene expression in the ovary. 1991:68–82. [Google Scholar]

- Stouffer RL, Adashi EY, Rock JA, Rosenwaks Z. Corpus luteum formation and demise. Reproductive Endocrinology, Surgery, and Technology. 1996:251–269. [Google Scholar]

- Stouffer RL, Nixon WE, Hodgen GD. Disparate effects of prostaglandins on basal and gonadotropin-stimulated progesterone production by luteal cells isolated from rhesus monkeys during the menstrual cycle and pregnancy. Biology of Reproduction. 1979;20:897–903. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod20.4.897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugimoto Y, Yamasaki A, Segi E, Tsuboi K, Aze Y, Nishimura T, Oida H, Yoshida N, Tanaka T, Katsuyama M, Hasumoto KY, Murata T, Hirata M, Ushikubi F, Negishi M, Ichikawa A, Narumiya S. Failure of parturition in mice lacking the prostaglandin F receptor. Science. 1997;277:681–683. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5326.681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tai CJ, Kang SK, Choi KC, Tzeng CR, Leung PCK. Role of mitogen-activated protein kinase in prostaglandin F2α action in human granulosa-luteal cells. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2001;86:375–380. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.1.7159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas P, Pang Y, Filardo EJ, Dong J. Identity of an estrogen membrane receptor coupled to a G protein in human breast cancer cells. Endocrinology. 2005;146:624–632. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai SJ, Wu MH, Chuang PC, Chen HM. Distinct regulation of gene expression by prostaglandin F2α (PGF2α) is associated with PGF2α resistance or suseptibility in human granulosa-luteal cells. Molecular Human Reproduction. 2001;7:415–423. doi: 10.1093/molehr/7.5.415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unlugedik E, Alfaidy N, Holloway A, Lye S, Bocking A, Challis J, Gibb W. Expression and regulation of prostaglandin receptors in the human placenta and fetal membranes at term and preterm. Reproduction, Fertility and Development. 2010;22:796–807. doi: 10.1071/RD09148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Driesche S, Smith VM, Myers M, Duncan WC. Expression and regulation of oestrogen receptors in the human corpus luteum. Reproduction. 2008;135:509–517. doi: 10.1530/REP-07-0427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallach EE, Bronson R, Hamada Y, Wright KH, Stevens VC. Effectiveness of prostaglandin F2α in restoration of hMG-hCG induced ovulation in indomethacin-treated rhesus monkeys. Prostaglandins. 1975;10:129–138. doi: 10.1016/0090-6980(75)90099-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C, Prossnitz ER, Roy SK. Expression of G protein-coupled receptor 30 in the hamster ovary: differential regulation by gonadotropins and steroid hormones. Endocrinology. 2007;148:4853–4864. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-0727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weick RF, Dierschke DJ, Karsch FJ, Butler WR, Hotchkiss J, Knobil E. Periovulatory time course of circulating gonadotropic and ovarian hormones in the rhesus monkey. Endocrinology. 1973;93:1140–1147. doi: 10.1210/endo-93-5-1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf DP, Alexander M, Zelinski-Wooten MB, Stouffer RL. Maturity and fertility of rhesus monkey oocytes collected at different intervals after an ovulatory stimulus (human chorionic gonadotropin) in in vitro fertilization cycles. Molecular Reproduction and Development. 1996;43:76–81. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2795(199601)43:1<76::AID-MRD10>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu F, Stouffer RL, Muller J, Hennebold JD, Wright JW, Bahar A, Leder G, Peters M, Thorne M, Sims M, Wintermantel T, Lindenthal B. Dynamics of the transcriptome in the primate ovulatory follicle. Molecular Human Reproduction. 2011;17:152–165. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gaq089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zelinski-Wooten MB, Stouffer RL. Intraluteal infusions of prostaglandins of the E, D, I, and A series prevent PGF 2α-induced, but not spontaneous, luteal regression in rhesus monkeys. Biology of Reproduction. 1990;43:507–516. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod43.3.507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]