Abstract

Teratozoospermia is characterized by the presence of spermatozoa with abnormal morphology over 85 % in sperm. When all the spermatozoa display a unique abnormality, teratozoospermia is said to be monomorphic. Two forms of monomorphic teratozoospermia, representing less than 1 % of male infertility, are recognized: macrozoospermia (also called macrocephalic sperm head syndrome) and globozoospermia (also called round-headed sperm syndrome). Macrozoospermia is defined as the presence of a very high percentage of spermatozoa with enlarged head and multiple flagella. Meiotic segregation studies in 30 males revealed that over 90 % of spermatozoa were aneuploid, mainly diploid. Sperm DNA fragmentation studies performed in a few patients showed an increase in DNA fragmentation index compared to fertile men. Four mutations in the AURKC gene, a key player in meiosis and more particularly in spermatogenesis, have been found to be responsible for macrozoospermia. Globozoospermia is characterized by round-headed spermatozoa with an absent acrosome, an aberrant nuclear membrane and midpiece defects. The rate of aneuploidy of various chromosomes in spermatozoa from 26 globozoospermic men was slightly increased compared to fertile men. However, this increase was of the same order as that commonly found in infertile men with altered sperm parameters. The majority of the studies found that globozoospermic males had a sperm DNA fragmentation index higher than in fertile men. Mutations or deletions in three genes, SPATA16, PICK1 and DPY19L2, have been shown to be responsible for globozoospermia. Identification of the genetic causes of macrozoospermia and globozoospermia should help refine diagnosis and treatment of these patients, avoiding long and painful treatments. Elucidating the molecular causes of these defects is of utmost importance as intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) is very disappointing in these two pathologies.

Keywords: Male infertility, Teratozoospermia, Globozoospermia, Macrozoospermia, Meiotic segregation, Sperm DNA fragmentation, Molecular genetics

Introduction

Infertility is defined as the inability for a couple to conceive a child following two years of unprotected sexual intercourses [1]. Infertility is estimated to affect up to 15 % of couples of reproductive age [2]. The causes of infertility are variable; they can be of male (20 %), female (34 %), mixed (38 %) or even idiopathic (8 %) origins [3].

Causes of infertility of male origin are numerous and multifactorial. Among them, teratozoospermia is characterized by the presence of spermatozoa with abnormal morphology over 85 % in sperm. To be considered as morphologically normal, a spermatozoon should have a normal acrosome, an oval head between 5 and 6 μm long and 2.5 and 3.5 μm width, a midpiece of 4.0 to 5.0 μm and a tail or flagellum about 50 μm long [4].

Teratozoospermia can be subdivided into 2 categories. An ejaculate presenting an excess of spermatozoa with more than one type of abnormality is considered polymorphic teratozoospermia. When all the spermatozoa display a unique abnormality, teratozoospermia is said to be monomorphic. Two forms of monomorphic teratozoospermia are recognized: macrozoospermia (also called macrocephalic sperm head syndrome) and globozoospermia (also called round-headed sperm syndrome) [5, 6]. They are the subject of this review.

Macrozoospermia

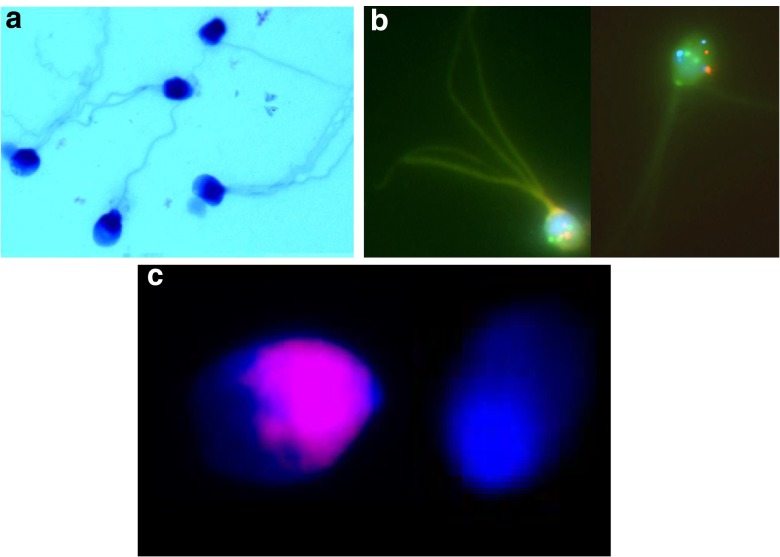

Macrozoospermia is a very rare morphologic disorder of spermatozoa observed in less than 1 % of infertile men. It can be defined as the presence of a very high percentage of spermatozoa with enlarged head, an irregular head shape, and multiple flagella (Fig. 1a) [7].

Fig. 1.

Macrozoospermia. a May Grünwald-Giemsa staining showing spermatozoa with enlarged head and multiple flagella. b Fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) showing a triploid sperm (probes: 13q14 in green, 21q22 in red) and a tetraploid sperm (probes: CEPX in green, CEPY in red, 18q11.1-2 in aqua). c TUNEL assay showing a sperm head with fragmented DNA (left side) and a normal sperm head (right side)

Meiotic segregation studies

Using fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH), several investigators found no association between the frequency of morphologically and chromosomally abnormal sperm [8, 9], except in macrozoospermia [5]. In 1996, Yurov et al. found in an infertile man that 40 % of his spermatozoa were large headed. They found that the majority of these macrocephalic spermatozoa contained a diploid chromosomal content, whereas the majority of normal-sized spermatozoa had a haploid content [10]. Since that publication, detailed meiotic segregation analysis using FISH has been reported in 30 males with large-headed, multiple-tailed sperm (Table 1). A strong correlation was found between the rate of sperm macrocephalic forms and the rate of aneuploidy (R = 0.88, p < 0.001).

Table 1.

Meiotic segregation analysis using FISH in 30 males with macrozoospermia

| Reference | Nr sperm | Macrocephalic forms | Multiple flagella | Abnormal acrosome | Diploidy | Triploidy | Tetraploidy | Aneuploidy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [14] | >500 | 78 | 51 | 94 | 29.6 | 24.7 | 21.9 | 94 |

| [14] | >500 | 74 | 30 | 84 | 16.8 | 19.1 | 16.7 | 93.7 |

| [14] | >500 | 87 | 47 | 96 | 18.5 | 24.5 | 21 | 95.2 |

| [14] | >500 | 60 | 37 | 65 | 21 | 10.7 | 11.8 | 91.7 |

| [14] | >500 | 95 | 70 | 96 | 22.1 | 24.3 | 15.1 | 98.7 |

| [14] | >500 | 79 | 50 | 85 | 15.4 | 8.9 | 11.1 | 92.7 |

| [14] | >500 | 98 | 30 | 98 | 20.2 | 25.4 | 17.8 | 99.3 |

| [14] | >500 | 98 | 64 | 99 | 30 | 27 | 19.3 | 100 |

| [54] | 68 | 76 | 76 | 77 | 32.5 | 26.5 | 3 | 100 |

| [54] | 50 | 60 | 49 | 72 | 4.5 | 2 | 1 | 85.5 |

| [54] | 200 | 54 | 50 | 80 | 18 | 12 | 4 | 76 |

| [13] | 130 | 91 | NA | NA | 50 | NA | NA | 100 |

| [13] | 314 | 82 | NA | NA | 23 | NA | NA | 100 |

| [55] | 500 | 100 | NA | NA | 40 | 24 | 5.1 | 98.4 |

| [56] | 1148 | 50 | 72 | 63 | 21.6 | 62.4 | 13.3 | NA |

| [57] | 2948 | 100 | 30 | NA | 80.4 | 14.8 | 4.4 | 99.6 |

| [57] | 1645 | >95 | NA | >95 | 71.3 | 16 | 12.7 | 100 |

| [57] | 473 | 100 | NA | NA | 58.8 | 23.2 | 17.8 | 99.8 |

| [58] | 102 | 100 | 100 | NA | 9.8 | 16.7 | 17.6 | 91.2 |

| [59] | 1430 | 29.5 | NA | NA | 17.1 | NA | 3.0 | 51.4 |

| [59] | 2811 | 22 | NA | NA | 10.2 | NA | 1.9 | 43.6 |

| [59] | 1955 | 49.7 | NA | NA | 18.1 | NA | 12.7 | 71.7 |

| [59] | 3981 | 19 | NA | NA | 16.5 | NA | 0.07 | 25.6 |

| [60] | 500 | 70 | NA | NA | 19.4 | 10.2 | NA | 99.2 |

| [8] | 1656 | 64 | 28 | 52 | 25.1 | 2.2 | NA | 89.2 |

| [5] | 1124 | 100 | 100 | NA | 18.42 | 6.14 | 33.99 | 99.29 |

| [15] | 1010 | 78 | 30 | NA | 0.99 | 18.12 | 44.55 | 99.9 |

| [15] | 2522 | 83 | 27 | NA | 4.52 | 9.99 | 35.65 | 99.92 |

| [15] | 576 | 72 | 10 | NA | 3.47 | 18.23 | 43.23 | 100 |

| [15] | 1103 | 80 | 47 | NA | 2.9 | 11.97 | 71.08 | 100 |

Some frequencies were recalculated from the raw data

Dieterich et al. (2007) performed FISH for chromosomes X,Y and 18 on a total of 3689 spermatozoa from 5 patients. Only 8 % of the analyzed spermatozoa were haploid while some 25 % were diploid [11]. Brahem et al. (2011) studied the semen samples of 12 males with macrocephalic sperm head syndrome. Triple color FISH analysis showed a mean total sperm aneuploidy rate of 98.33 % in the macrozoospermia group, including a mean rate of 22.7, 25.3 and 18.3 % of sperm nuclei with diploidy, triploidy and tetraploidy, respectively [12]. Altogether, the meiotic segregation analysis shows that more than 90 % of the sperm heads have an aneuploid composition (Fig. 1b).

Guthauser et al. (2006) found that only very low proportions of normal headed-size spermatozoa had a normal chromosomal content (X18 or Y18). Therefore, low fertilization and pregnancy rates may be due to the high incidence of aneuploidy in the apparently normal-sized spermatozoa that may be used for intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) [13].

Sperm DNA fragmentation studies

Two studies evaluated the presence of apoptosis-related DNA strand breaks in spermatozoa using the terminal desoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated deoxyuridine triphosphate nick-end labelling (TUNEL) assay. Brahem et al. (2011) calculated the DNA fragmentation index to be included between 33 and 75 % in 8 males with macrozoospermia while it was less than 10 % in controls [14]. In a study published by Perrin et al. (2011) on three patients, the proportion of spermatozoa with DNA fragmentation varied from 4.4 to 28 %, the mean DNA fragmentation percentage among the control men being 1.20 ± 0.95 % (Fig. 1c) [15]. In all patients, the rate of DNA fragmentation was significantly higher than in their respective control groups.

Molecular genetic studies

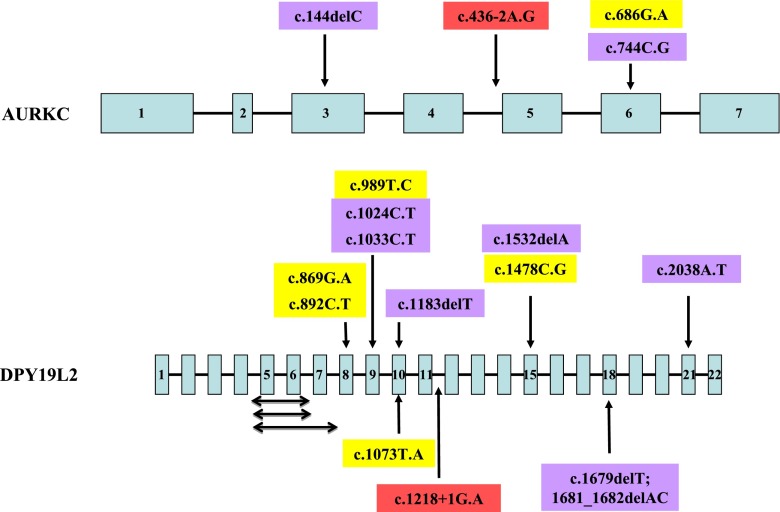

Dieterich et al. (2007) carried out a genome-wide microsatellite scan of ten infertile men (4 French citizens of North African descent and 6 from the Rabat region in Morocco) with a large-headed sperm phenotype. Subsequently, they added 4 more males from Rabat [11]. They identified a small region of homozygosity at 19qter. As the aurora kinase C (AURKC) gene is located close to that region, they sequenced the coding sequence and detected a homozygous cytosine deletion in exon 3 (c.144delC) in all 14 individuals (Fig. 2). This mutation leads to the premature insertion of a stop codon, inducing the production of a non functional and truncated protein lacking its kinase domain [11].

Fig. 2.

Schematic diagram of the AURKC and DPY19L2 genes and localization of the mutations thus far identified. Double-headed arrows represent intragenic deletions; yellow boxes represent missense mutations; blue boxes represent nonsense mutations; red boxes represent splice-site mutations

Harbuz et al. (2009) analyzed 34 patients with macrozoospermia. The AURKC c.144delC mutation was found in a homozygous state in 32 patients. Two brothers had a compound genotype made of the c.144delC mutation and a new mutation in exon 6, c.686G.A (p.C229Y). They estimated the heterozygote rate to be 1 in 50 in the Maghreban population [16, 17].

Ben Khelifa et al. (2011) described a new mutation in AURKC in two brothers of Tunisian descent. They were compound heterozygotes for the c.144delC mutation and the c.436-2A.G mutation. This later mutation is located in the acceptor consensus splice site of exon 5 and leads to the skipping of exon 5. As a consequence, the mutant protein lacks the 50 amino acids coded by exon 5 (amino acids 146–195). These amino acids are localized in the middle of the catalytic domain and their absence is therefore very likely to severely hamper the functionality of the protein [18].

Ben Khelifa et al. (2012) genotyped 44 macrozoospermic males of European and North African origins. They identified a new nonsense mutation (c.744C.G, p.Y248X) in 11 males (9 homozygotes and 2 compound heterozygotes). Altogether, this group analyzed 83 probands. A mutation was identified in 68 out these probands (82 %). The c.144delC and c.744C.G mutations represented 85.5 and 13 % of the mutated alleles respectively [19].

Eloualid et al. (2014) screened 326 infertile Moroccan patients for the presence of the AURKC c.144delC mutation. This mutation was detected in homozygous (4/326−1.23 %) and heterozygous (6/326–1.84 %) states, with frequencies of 1.23 and 1.84 %, respectively. Two homozygotes had azoospermia and the other 2 macrocephalic and multiflagellar spermatozoa. Eight heterozygous individuals carrying the c.144delC mutation were identified among 459 control fertile individuals (1.74 %) [20]. All 11 Moroccan males with a rate of macrocephalic spermatozoa representing at least 70 % of the total sperm concentration reported by El Kerch et al. (2011) were homozygous for the c.144delC mutation [21].

The AURKC gene, located at 19q13.43 has 7 coding exons and encodes a 309 amino acids protein that is a member of the Aurora subfamily of serine/threonine protein kinases [22]. It is a component of the chromosomal passenger complex (CPC), a complex that acts as a key regulator of mitosis. The CPC complex has essential functions at the centromere in ensuring correct chromosome alignment and segregation and is required for chromatin-induced microtubule stabilization and spindle assembly. It plays also a role in meiosis and more particularly in spermatogenesis [23–25].

Globozoospermia

Globozoospermia is also a very rare condition, observed in less than 0.1 % of infertile males. It is characterized by round-headed spermatozoa with an absent acrosome, an aberrant nuclear membrane and midpiece defects [26]. Lack of acrosome, which production is a postmeiotic event in spermatogenesis, and round sperm head are its main characteristics [27]. The acrosomeless spermatozoon is unable to go through the zona pellucida and fuse with the oolemma of the oocyte and fertilization failures have been attributed to a deficiency in oocyte activation capacity, even when ICSI is attempted [28–30].

Meiotic segregation studies

Several workers have investigated the rate of aneuploidy of various chromosomes in spermatozoa from 26 globozoospermic men using FISH [6] (Table 2). The slightly increased aneuploidy rate observed in some patients could reflect disturbances in spermatogenesis, as commonly observed in patients with oligoasthenoteratozoospermia.

Table 2.

Sperm aneuploidy rates in globozoospermic males reported in the literature

| References | Patient | Disomy (%) | Diploidy (%) | Nr spz | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 12 | 13 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 21 | X | Y | XY | ||||

| [35] | Sib 1 | 0.7 | 0 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0 | 12.1 * | ±5000 | |||||||||

| [35] | Sib 2 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 3.0 * | 0.4 | 0 | 0 | ±5000 | |||||||||

| [8] | 0 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.1 | 3716 | |||||||||||

| [61] | Sib 1 | 0.4 | 4.03 * | 0.74 | 0.4 | 0.43 | 0.52 | 10,000 | |||||||||

| [61] | Sib 2 | 0.32 | 0.58 | 0.74 | 0.14 | 0.58 | 0.6 | 10,000 | |||||||||

| [62] | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.13 | 0 | 0 | 3885 | ||||||||||

| [63] | 2.0 for chromosomes 13, 18, 21, X and Y | 1000 | |||||||||||||||

| [64] | 0.09 | 0.13 | 0.19 | 0.12 | 0.07 | 0.18 * | 0.21 | 30,145 | |||||||||

| [65] | Pat 1 | 0.26 | 0.2 | 0.39 | 0.02 | 0.39 | 0 | 0.04 | 0.15 | 0.88 * | 10,719 | ||||||

| [65] | Pat 2 | 0.1 | 0.14 | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.3 | 15,152 | ||||||

| [66] | 4.0 * | 5.0 * | 0.1 * | 1.0 | 100 | ||||||||||||

| [67] | Pat 1 | 0.052 | 0.364 * | 0.599 * | 7388 | ||||||||||||

| [67] | Pat 2 | 0.078 | 0.364 * | 0.494 * | |||||||||||||

| [68] | NS | NS | NS | 0.66 * | NS | NA | |||||||||||

| [69] | Aneuploidy rate not higher in globozoospermic cells | NA | |||||||||||||||

| [70] | 2.3 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 400 | |||||||||||

| [71] | Pat 1 | 1.2 * | 0.09 | 0.12 | 0.2 | 1.8 * | 1.2 * | 0.15 | ±500 | ||||||||

| [71] | Pat 2 | 2.0 * | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0 | 2.75 * | 3.0 * | 2.0 * | ±500 | ||||||||

| [15] | 0.08 | 0.12 | 1.11 * | 0.27 * | 0.23 * | 0.35 * | 0.13 | 10,165 | |||||||||

| [72] | <1.0 for chromosomes 13, 18, 21, X and Y | 500 | |||||||||||||||

| [73] | Pat 1 | 1.06 for chromosomes 18, X and Y (NS) | 658 | ||||||||||||||

| [73] | Pat 2 | 1.18 for chromosomes 18, X and Y (NS) | 1019 | ||||||||||||||

| [73] | Pat 3 | 1.90 for chromosomes 18, X and Y (NS) | 948 | ||||||||||||||

| [73] | Pat 4 | 0.9 for chromosomes 18, X and Y (NS) | 1000 | ||||||||||||||

| [73] | Pat 5 | 0.8 for chromosomes 18, X and Y (NS) | 963 | ||||||||||||||

| [73] | Pat 6 | 0.9 for chromosomes 18, X and Y (NS) | 950 | ||||||||||||||

*p < 0.05 when compared to controls

NS not significant (p > 0.05)

Brahem et al. (2011) compared the sperm aneuploid rate between patients with polymorphic teratozoospermia, globozoospermia, macrozoospermia and healthy fertile men [12]. They found a statistically significant increase in the rate of aneuploidy between all three teratozoospermic groups compared to the fertile group (P < 0.001). However, no significant difference in sperm aneuploidy was found between globozoospermia and polymorphic teratozoospermia (p > 0.05).

In fact, variations found in the studies presented here are of the same order as those that are commonly found in the literature about infertile men with a normal karyotype but altered sperm parameters [15, 31].

Sperm DNA fragmentation studies

Several techniques are currently used to measure the sperm DNA integrity in the investigation of male fertility [32]. However, the most widely used technique is the TUNEL assay [32]. The DNA fragmentation index (DFI) was calculated in a few globozoospermic patients [6] (Table 3). The majority of the studies, although in a limited number, found that globozoospermic males had a sperm DNA fragmentation index statistically significantly higher than in fertile men.

Table 3.

Sperm DNA fragmentation rates in globozoospermic males reported in the literature

| References | Number of patients | Number of spermatozoa | DNA fragmentation index | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient | Control | ||||

| [74] | NA | NA | 10 % | 0.1 % | |

| [75] | 1 | NA | 13 % a | NS | |

| [76] | 1 | NA | 37 % | 22.5 % | P < 0.005 |

| [68] | 1 | NA | 45.7 % b | 30 % | |

| [77] | 1 | NA | 97.1 % c | 41.3 % | P < 0.05 |

| [70] | 1 | 200 | 80 % | 27 ± 13 % | |

| [71] | 1 | 500 | 40 % | 12 ± 2.12 % | P < 0.001 |

| [71] | 1 | 500 | 80 % | 12 ± 2.12 % | P < 0.001 |

| [72] | 1 | 500 | 6 % | NS | |

| [15] | 1 | 500 | 9.6 % | 1.2 % | P < 0.001 |

| [73] | 1 | 700 | 18 % | d | |

| [73] | 1 | 1000 | 29 % | d | |

| [73] | 1 | 950 | 19 % | d | |

| [73] | 1 | 1000 | 10 % | d | |

| [73] | 1 | 960 | 2 % | d | |

| [73] | 1 | 950 | 15 % | d | |

NA not available

aSCSA and COMET assays

bsperm chromatin disperse test (Halosperm technique)

cacridine orange test

dNormal values < 13 %

NS not significant (p > 0.05)

Brahem et al. (2011) compared the rate of sperm DNA fragmentation between patients with polymorphic teratozoospermia, globozoospermia and healthy fertile men [12]. They found a statistically significant increase in the rate of sperm DNA fragmentation between the globozoospermia and the fertile groups (40.00 % ± 3.55 % versus 8.90 % ± 1.3 %) (P < 0.01). However, no significant difference in sperm DNA fragmentation was found between globozoospermia and polymorphic teratozoospermia (40.00 % ± 3.55 % versus 45.33 % ± 10.02 %) (p > 0.05).

These results suggested that sperm of globozoospermic males could carry abnormal remodeled chromatin, which could be a possible source of DNA fragmentation. Indeed, some workers reported abnormal chromatin condensation in globozoospermia, with a high heterogeneity in the degree of maturity [33], due to an altered replacement of histones by protamines [34, 35].

Molecular genetic studies

The presence of consanguineous marriages in families affected with globozoospermia and reports of two or more sibs in several families suggested a genetic contribution to globozoospermia in humans with an autosomal recessive mode of inheritance [6, 35–40]. Three genes segregating on an autosomal recessive mode have now been identified to be associated with globozoospermia in humans.

Dam et al. (2007) identified a homozygous mutation (c.848G.A) in exon 4 of the SPATA16 (spermatogenesis-associated protein 16) gene (located at chromosome band 3q26.32), leading to the substitution of an arginine to a glutamine at residue 283 (R283Q) in the protein, in three brothers affected with globozoospermia from a consanguineous Ashkenazi Jewish family [39].

Liu et al. (2010) identified a homozygous G->A transition at nucleotide 1567 in exon 13 of the PICK1 (protein interacting with PRKCA 1) gene (located at chromosome band 22q12.3-q13.2), generating a missense substitution (G393R) in the protein, in one patient [40].

These two genes could be involved in the same process of spermiogenesis. Indeed, the SPATA16 protein localizes to the Golgi apparatus and the proacrosomal granules that are transported in the acrosome in round and elongated spermatids [41]. Pick1 localizes to Golgi-derived proacrosomal granules and is involved in vesicle trafficking from the Golgi to the acrosome and participates in acrosome biogenesis [42].

In 2011, Koscinski et al. identified a homologous deletion of the DPY19L2 (dpy-19-like 2) gene located at 12q14.2 in 4 globozoospermic brothers of a Jordanian consanguineous family and in three additional unrelated patients [43]. Subsequently, a whole genome SNP scan on 20 patients presenting with total globozoospermia allowed the identification of a 200 kb homozygous deletion encompassing only DPY19L2 in 15 patients of different ethnic background [44]. More patients with globozoospermia associated with a homozygous deletion of the whole DPY19L2 were reported [45–48]. The mechanism underlying this deletion is due to a non-allelic homologous recombination (NAHR) between two low copy repeats that share 96.5 % identity and flank the DPY19L2 locus [43].

However, it appears very quickly that other genetic defects in the DPY19L2 gene could be responsible for globozoospermia (Fig. 2). At present, three intragenic deletions have been described [45]. One patient had a deletion of exons 5, 6 and 7 inducing an aberrant splicing between exons 4 and 8 that would give rise to a protein with a deletion of 91 amino acids. Two other patients had a deletion of exons 5 and 6 inducing an aberrant splicing between exons 4 and 7 that would give rise to a frame shift, introducing a premature stop codon; it should be noted that the breakpoints location in these two patients was different.

The other genetic defects consisted in mutations [45, 47, 48]. A donor splice-site mutation in intron 11 (c.1218 + 1G.A) was identified in one patient. Six mutations, located in exons 9, 11, 15, 18 and 21, introduced a premature stop codon; two of these mutations (c.1183delT and c.1532delA) were identified in two unrelated patients each. Five point mutations, including one (c.869G.A) found in three unrelated males, lead to an amino acid change; they were distributed in exons 8, 9, 10 and 15. Altogether, 10 of the 12 mutations thus far identified clustered between exons 5 and 15 (Fig. 2).

The DPY19L2 gene belongs to a family of genes derived from the DPY-19 gene, present in Caenorhabditis elegans, that is involved in the establishment of cell polarity in the worm. This family of proteins has no obvious homology with any other membrane proteins and represents a new family of integral membrane proteins [49]. The DPY19L2 gene has 22 coding exons [50] and the resulting protein 758 amino acids. It might be involved in indicating the anterior pole of the spermatozoon and in the acroplaxome positioning, a subacrosomal cytoskeletal plate toward which Golgi-derived vesicles fuse [51].

The DPY19L2 protein is thought to be a transmembrane protein with 10 putative transmembrane segments with the N- and C-terminal domains located in the nucleoplasm. It is expressed specifically in spermatids and localized only in the inner nuclear membrane of the nucleus facing the acrosome. Dpy19l2 participates in the anchoring of the acrosome to the nucleus, bridging the nuclear envelope to both the nuclear dense lamina and the acroplaxome [44].

Conclusions

It is thought that between 1500 and 2000 genes are involved in the control of spermatogenesis. Therefore, it is expected that genetic alterations in these genes would disturb male fertility [52]. Furthermore, a novel mechanism of posttranscriptional control mediated by microRNAs has lately emerged as an important regulator of spermatogenesis [53]. Development of next generation sequencing is likely to identify new genes involved in male infertility.

Although monomorphic teratozoospermia is very rare, macrozoospermia and globozoospermia represent a brand new avenue for the search of genes involved in spermatogenesis. Identification of the genetic causes should help refine diagnosis and treatment of these patients, avoiding long and painful treatments. Elucidating the molecular causes of these defects is of utmost importance as ICSI is very disappointing in these two pathologies.

Acknowledgments

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest

Footnotes

Capsule

Two forms of monomorphic teratozoospermia are recognized: macrozoospermia (or macrocephalic sperm head syndrome) and globozoospermia (or round-headed sperm syndrome). Both pathologies are characterized by a high rate of sperm aneuploidy and DNA fragmentation index compared to fertile males. Identification of their genetic causes should help refine diagnosis and treatment of these patients, avoiding long and painful treatments. Elucidating the molecular causes of these defects is of utmost importance as intracytoplasmic sperm injection is very disappointing in these two pathologies.

References

- 1.World Health Organization . Laboratory manual for the examination of human semen and semen-cervical mucus interaction. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boivin J, Bunting L, Collins JA, Nygren KG. International estimates of infertility prevalence and treatment-seeking: potential need and demand for infertility medical care. Hum Reprod. 2007;22:1506–1512. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dem046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thonneau P, Marchand S, Tallec A, Ferial ML, Ducot B, Lansac J, et al. Incidence and main causes of infertility in a resident population (1 850 000) of three French regions (1988–1989) Hum Reprod. 1991;6:811–816. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a137433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Perrin A, Nguyen MH, Douet-Guilbert N, Morel F, De Braekeleer M. Motile sperm organelle morphology examination (MSOME): where do we stand twelve years later? Expert Rev Obstet Gynecol. 2013;8:249–260. doi: 10.1586/eog.13.13. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Perrin A, Morel F, Moy L, Colleu D, Amice V, De Braekeleer M. Study of aneuploidy in large-headed, multiple-tailed spermatozoa: case report and review of the literature. Fertil Steril. 2008;90:1201–1207. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Perrin A, Coat C, Nguyen MH, Talagas M, Morel F, Amice J, et al. Molecular cytogenetic and genetic aspects of globozoospermia: a review. Andrologia. 2013;45:1–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0272.2012.01308.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nistal M, Paniagua R, Herruzo A. Multi-tailed spermatozoa in a case with asthenospermia and teratospermia. Virchows Arch B Cell Pathol. 1977;26:111–118. doi: 10.1007/BF02889540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Viville S, Mollard R, Bach ML, Falquet C, Gerlinger P, Warter S. Do morphological anomalies reflect chromosomal aneuploidies? Hum Reprod. 2000;15:2563–2566. doi: 10.1093/humrep/15.12.2563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Celik-Ozenci C, Jakab A, Kovacs T, Catalanotti J, Demir R, Bray-Ward P, et al. Sperm selection for ICSI: shape properties do not predict the absence or presence of numerical chromosomal aberrations. Hum Reprod. 2004;19:2052–2059. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yurov YB, Saias MJ, Vorsanova SG, Erny R, Soloviev IV, Sharonin VO, et al. Rapid chromosomal analysis of germ-line cells by FISH: an investigation of an infertile male with large-headed spermatozoa. Mol Hum Reprod. 1996;2:665–668. doi: 10.1093/molehr/2.9.665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dieterich K, Soto Rifo R, Faure AK, Hennebicq S, Ben Amar B, Zahi M, et al. Homozygous mutation of AURKC yields large-headed polyploid spermatozoa and causes male infertility. Nat Genet. 2007;39:661–665. doi: 10.1038/ng2027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brahem S, Elghezal H, Ghedir H, Landolsi H, Amara A, Ibala S, et al. Cytogenetic and molecular aspects of absolute teratozoospermia: comparison between polymorphic and monomorphic forms. Urology. 2011;78:1313–1319. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2011.08.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guthauser B, Vialard F, Dakouane M, Izard V, Albert M, Selva J. Chromosomal analysis of spermatozoa with normal-sized heads in two infertile patients with macrocephalic sperm head syndrome. Fertil Steril. 2006;85:750.e5–750.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2005.07.1334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brahem S, Mehdi M, Elghezal H, Saad A. Study of aneuploidy rate and sperm DNA fragmentation in large-headed, multiple-tailed spermatozoa. Andrologia. 2012;44:130–135. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0272.2010.01115.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Perrin A, Louanjli N, Ziane Z, Louanjli T, Le Roy C, Guéganic N, et al. Study of aneuploidy and DNA fragmentation in gametes of patients with severe teratozoospermia. Reprod Biomed Online. 2011;22:148–154. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2010.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harbuz R, Zouari R, Dieterich K, Nikas Y, Lunardi J, Hennebicq S. Ray PF [Function of aurora kinase C (AURKC) in human reproduction] Gynecol Obstet Fertil. 2009;37:546–551. doi: 10.1016/j.gyobfe.2009.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dieterich K, Zouari R, Harbuz R, Vialard F, Martinez D, Bellayou H, et al. The Aurora Kinase C c.144delC mutation causes meiosis I arrest in men and is frequent in the North African population. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:1301–1309. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ben Khelifa M, Zouari R, Harbuz R, Halouani L, Arnoult C, Lunardi J, et al. A new AURKC mutation causing macrozoospermia: implications for human spermatogenesis and clinical diagnosis. Mol Hum Reprod. 2011;17:762–768. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gar050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ben Khelifa M, Coutton C, Blum MG, Abada F, Harbuz R, Zouari R, et al. Identification of a new recurrent aurora kinase C mutation in both European and African men with macrozoospermia. Hum Reprod. 2012;27:3337–3346. doi: 10.1093/humrep/des296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eloualid A, Rouba H, Rhaissi H, Barakat A, Louanjli N, Bashamboo A, et al. Prevalence of the Aurora kinase C c.144delC mutation in infertile Moroccan men. Fertil Steril. 2014;101:1086–1090. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.12.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.El Kerch F, Lamzouri A, Laarabi FZ, Zahi M, Ben Amar B. Sefiani A [Confirmation of the high prevalence in Morocco of the homozygous mutation c.144delC in the aurora kinase C gene (AURKC) in the teratozoospermia with large-headed spermatozoa] J Gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod (Paris) 2011;40:329–333. doi: 10.1016/j.jgyn.2010.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bernard M, Sanseau P, Henry C, Couturier A, Prigent C. Cloning of STK13, a third human protein kinase related to Drosophila aurora and budding yeast Ipl1 that maps on chromosome 19q13.3-ter. Genomics. 1998;53:406–409. doi: 10.1006/geno.1998.5522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kimura M, Matsuda Y, Yoshioka T, Okano Y. Cell cycle-dependent expression and centrosome localization of a third human aurora/Ipl1-related protein kinase, AIK3. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:7334–7340. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.11.7334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tang CJ, Chuang CK, Hu HM, Tang TK. The zinc finger domain of Tzfp binds to the tbs motif located at the upstream flanking region of the Aie1 (aurora-C) kinase gene. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:19631–19639. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100170200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tang CJ, Lin CY, Tang TK. Dynamic localization and functional implications of Aurora-C kinase during male mouse meiosis. Dev Biol. 2006;290:398–410. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.11.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schirren CG, Holstein AF, Schirren C. Uber die Morphogenese rundkopfiger Spermatozoen des Menschen. Andrologia. 1971;3:125. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Singh G. Ultrastructural features of round-headed human spermatozoa. Int J Fertil. 1992;37:99–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aitken RJ, Kerr L, Bolton V, Hargreave T. Analysis of sperm function in globozoospermia: implications for the mechanism of sperm-zona interaction. Fertil Steril. 1990;54:701–707. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)53833-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dale B, Iaccarino M, Fortunato A, Gragnaniello G, Kyozuka K, Tosti E. A morphological and functional study of fusibility in round-headed spermatozoa in the human. Fertil Steril. 1994;61:336–340. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)56528-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rybouchkin A, Dozortsev D, Pelinck MJ, De Sutter P, Dhont M. Analysis of the oocyte activating capacity and chromosomal complement of round-headed human spermatozoa by their injection into mouse oocytes. Hum Reprod. 1996;11:2170–2175. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a019071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kirkpatrick G, Ferguson KA, Gao H, Tang S, Chow V, Yuen BH, et al. A comparison of sperm aneuploidy rates between infertile men with normal and abnormal karyotypes. Hum Reprod. 2008;23:1679–1683. doi: 10.1093/humrep/den126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Morel F, Douet-Guilbert N, Perrin A, Le Bris MJ, Amice V, Amice J, et al. Chromosomal abnormalities in spermatozoa. In: De Braekeleer M, et al., editors. Cytogenetics and Infertility. Trivandrum: Transworld Research Network; 2006. pp. 53–112. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dam AH, Feenstra I, Westphal JR, Ramos L, van Golde RJ, Kremer JA. Globozoospermia revisited. Hum Reprod Update. 2007;13:63–75. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dml047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Blanchard Y, Lescoat D, Le Lannou D. Anomalous distribution of nuclear basic proteins in round-headed human spermatozoa. Andrologia. 1990;22:549–555. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0272.1990.tb02052.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Carrell DT, Emery BR, Liu L. Characterization of aneuploidy rates, protamine levels, ultrastructure, and functional ability of round-headed sperm from two siblings and implications for intracytoplasmic sperm injection. Fertil Steril. 1999;71:511–516. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(98)00498-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Florke-Gerloff S, Topfer-Petersen E, Muller-Esterl W, Mansouri A, Schatz R, Schirren C, et al. Biochemical and genetic investigation of round-headed spermatozoa in infertile men including two brothers and their father. Andrologia. 1984;16:187–202. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0272.1984.tb00262.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kilani Z, Ismail R, Ghunaim S, Mohamed H, Hughes D, Brewis I, et al. Evaluation and treatment of familial globozoospermia in five brothers. Fertil Steril. 2004;82:1436–1439. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2004.03.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dirican EK, Isik A, Vicdan K, Sozen E, Suludere Z. Clinical pregnancies and livebirths achieved by intracytoplasmic injection of round headed acrosomeless spermatozoa with and without oocyte activation in familial globozoospermia: case report. Asian J Androl. 2008;10:332–336. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7262.2008.00248.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dam AH, Koscinski I, Kremer JA, Moutou C, Jaeger AS, Oudakker AR, et al. Homozygous mutation in SPATA16 is associated with male infertility in human globozoospermia. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81:813–820. doi: 10.1086/521314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu G, Shi QW, Lu GX. A newly discovered mutation in PICK1 in a human with globozoospermia. Asian J Androl. 2010;12:556–560. doi: 10.1038/aja.2010.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xu M, Xiao J, Chen J, Li J, Yin L, Zhu H, et al. Identification and characterization of a novel human testis-specific Golgi protein, NYD-SP12. Mol Hum Reprod. 2003;9:9–17. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gag005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xiao N, Kam C, Shen C, Jin W, Wang J, Lee KM, et al. PICK1 deficiency causes male infertility in mice by disrupting acrosome formation. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:802–812. doi: 10.1172/JCI36230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Koscinski I, Elinati E, Fossard C, Redin C, Muller J, Velez DC, et al. DPY19L2 deletion as a major cause of globozoospermia. Am J Hum Genet. 2011;88:344–350. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.01.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Harbuz R, Zouari R, Pierre V, Ben Khelifa M, Kharouf M, Coutton C, et al. A recurrent deletion of DPY19L2 causes infertility in man by blocking sperm head elongation and acrosome formation. Am J Hum Genet. 2011;88:351–361. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Elinati E, Kuentz P, Redin C, Jaber S, Vanden Meerschaut F, Makarian J, et al. Globozoospermia is mainly due to DPY19L2 deletion via non-allelic homologous recombination involving two recombination hotspots. Hum Mol Genet. 2012;21:3695–3702. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Noveski P, Madjunkova S, Maleva I, Sotiroska V, Petanovski Z, Plaseska-Karanfilska D. A homozygous deletion of the DPY19l2 gene is a cause of globozoospermia in Men from the republic of Macedonia. Balk J Med Genet. 2013;16:73–76. doi: 10.2478/bjmg-2013-0021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Coutton C, Zouari R, Abada F, Ben KM, Merdassi G, Triki C, et al. MLPA and sequence analysis of DPY19L2 reveals point mutations causing globozoospermia. Hum Reprod. 2012;27:2549–2558. doi: 10.1093/humrep/des160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhu F, Gong F, Lin G, Lu G. DPY19L2 gene mutations are a major cause of globozoospermia: identification of three novel point mutations. Mol Hum Reprod. 2013;19:395–404. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gat018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Honigberg L, Kenyon C. Establishment of left/right asymmetry in neuroblast migration by UNC-40/DCC, UNC-73/Trio and DPY-19 proteins in C. elegans. Development. 2000;127:4655–4668. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.21.4655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Carson AR, Cheung J, Scherer SW. Duplication and relocation of the functional DPY19L2 gene within low copy repeats. BMC Genomics. 2006;7:45. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-7-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kierszenbaum AL, Tres LL. The acrosome-acroplaxome-manchette complex and the shaping of the spermatid head. Arch Histol Cytol. 2004;67:271–284. doi: 10.1679/aohc.67.271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Matzuk MM, Lamb DJ. The biology of infertility: research advances and clinical challenges. Nat Med. 2008;14:1197–1213. doi: 10.1038/nm.f.1895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Papaioannou MD, Nef S. microRNAs in the testis: building up male fertility. J Androl. 2010;31:26–33. doi: 10.2164/jandrol.109.008128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lewis-Jones I, Aziz N, Seshadri S, Douglas A, Howard P. Sperm chromosomal abnormalities are linked to sperm morphologic deformities. Fertil Steril. 2003;79:212–215. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(02)04411-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.In’t Veld PA, Broekmans FJ, de France HF, Pearson PL, Pieters MH, van Kooij RJ. Intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) and chromosomally abnormal spermatozoa. Hum Reprod. 1997;12:752–754. doi: 10.1093/humrep/12.4.752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Benzacken B, Gavelle FM, Martin-Pont B, Dupuy O, Lievre N, Hugues JN, et al. Familial sperm polyploidy induced by genetic spermatogenesis failure. Hum Reprod. 2001;16:2646–2651. doi: 10.1093/humrep/16.12.2646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Devillard F, Metzler-Guillemain C, Pelletier R, DeRobertis C, Bergues U, Hennebicq S, et al. Polyploidy in large-headed sperm: FISH study of three cases. Hum Reprod. 2002;17:1292–1298. doi: 10.1093/humrep/17.5.1292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mateu E, Rodrigo L, Prados N, Gil-Salom M, Remohi J, Pellicer A, et al. High incidence of chromosomal abnormalities in large-headed and multiple-tailed spermatozoa. J Androl. 2006;27:6–10. doi: 10.2164/jandrol.05033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Achard V, Paulmyer-Lacroix O, Mercier G, Porcu G, Saias-Magnan J, Metzler-Guillemain C, et al. Reproductive failure in patients with various percentages of macronuclear spermatozoa: high level of aneuploid and polyploid spermatozoa. J Androl. 2007;28:600–606. doi: 10.2164/jandrol.106.001933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Weissenberg R, Aviram A, Golan R, Lewin LM, Levron J, Madgar I, et al. Concurrent use of flow cytometry and fluorescence in-situ hybridization techniques for detecting faulty meiosis in a human sperm sample. Mol Hum Reprod. 1998;4:61–66. doi: 10.1093/molehr/4.1.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Carrell DT, Wilcox AL, Udoff LC, Thorp C, Campbell B. Chromosome 15 aneuploidy in the sperm and conceptus of a sibling with variable familial expression of round-headed sperm syndrome. Fertil Steril. 2001;76:1258–1260. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(01)02904-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Vicari E, Perdichizzi A, De Palma A, Burrello N, D’Agata R, Calogero AE. Globozoospermia is associated with chromatin structure abnormalities. Hum Reprod. 2002;17:2128–2133. doi: 10.1093/humrep/17.8.2128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zeyneloglu HB, Baltaci V, Duran HE, Erdemli E, Batioglu S. Achievement of pregnancy in globozoospermia with Y chromosome microdeletion after ICSI. Hum Reprod. 2002;17:1833–1836. doi: 10.1093/humrep/17.7.1833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Martin RH, Greene C, Rademaker AW. Sperm chromosome aneuploidy analysis in a man with globozoospermia. Fertil Steril. 2003;79:1662–1664. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(03)00401-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Morel F, Douet-Guilbert N, Moerman A, Duban B, Marchetti C, Delobel B, et al. Chromosome aneuploidy in the spermatozoa of two men with globozoospermia. Mol Hum Reprod. 2004;10:835–838. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gah111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ditzel N, El Danasouri I, Just W, Sterzik K. Higher aneuploidy rates of chromosomes 13, 16, and 21 in a patient with globozoospermia. Fertil Steril. 2005;84:217–218. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2005.01.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Moretti E, Collodel G, Scapigliati G, Cosci I, Sartini B, Baccetti B. ‘Round head’ sperm defect. Ultrastructural and meiotic segregation study. J Submicrosc Cytol Pathol. 2005;37:297–303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tejera A, Molla M, Muriel L, Remohi J, Pellicer A, De Pablo JL. Successful pregnancy and childbirth after intracytoplasmic sperm injection with calcium ionophore oocyte activation in a globozoospermic patient. Fertil Steril. 2008;90:1202–1205. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.11.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sahu B, Ozturk O, Serhal P. Successful pregnancy in globozoospermia with severe oligoasthenospermia after ICSI. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2010;30:869–870. doi: 10.3109/01443615.2010.515321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Taylor SL, Yoon SY, Morshedi MS, Lacey DR, Jellerette T, Fissore RA, et al. Complete globozoospermia associated with PLCzeta deficiency treated with calcium ionophore and ICSI results in pregnancy. Reprod Biomed Online. 2010;20:559–564. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2009.12.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Brahem S, Mehdi M, Elghezal H, Saad A. Analysis of sperm aneuploidies and DNA fragmentation in patients with globozoospermia or with abnormal acrosomes. Urology. 2011;77:1343–1348. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2010.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sermondade N, Hafhouf E, Dupont C, Bechoua S, Palacios C, Eustache F, et al. Successful childbirth after intracytoplasmic morphologically selected sperm injection without assisted oocyte activation in a patient with globozoospermia. Hum Reprod. 2011;26:2944–2949. doi: 10.1093/humrep/der258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zhioua A, Merdassi G, Bhouri R, Ferfouri F, Ben Ammar A, Amouri A, et al. Apport de l’exploration cytogénétique et ultrastructurale dans le pronostic de fertilité des sujets globozoospermiques. Andrologie. 2011;21:240–246. doi: 10.1007/s12610-011-0145-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Baccetti B, Collodel G, Piomboni P. Apoptosis in human ejaculated sperm cells (notulae seminologicae 9) J Submicrosc Cytol Pathol. 1996;28:587–596. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Larson KL, Brannian JD, Singh NP, Burbach JA, Jost LK, Hansen KP, et al. Chromatin structure in globozoospermia: a case report. J Androl. 2001;22:424–431. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Vicari E, Perdichizzi A, De Palma A, Burrello N, D’Agata R, Calogero AE. Globozoospermia is associated with chromatin structure abnormalities: case report. Hum Reprod. 2002;17:2128–2133. doi: 10.1093/humrep/17.8.2128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Egashira A, Murakami M, Haigo K, Horiuchi T, Kuramoto T. A successful pregnancy and live birth after intracytoplasmic sperm injection with globozoospermic sperm and electrical oocyte activation. Fertil Steril. 2009;92:2037e5–2037e9. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]