Abstract

Introduction

There is paucity of case reports that describe the successful reimplantation of a penis after amputation. We sought to report on self-inflicted penile amputation and comment on its surgical management and review current literature.

Aim

To report on self-inflicted penile amputation and comment on its surgical management and review current literature.

Methods

A 19-year-old male with no prior medical history presented to our university-affiliated trauma center following sustaining a self-inflicted amputation of shaft penis secondary to severe methamphetamine-induced psychosis. He immediately underwent extensive reconstructive reimplantation of the penis performed jointly by plastics and urology teams reattaching all visible neurovascular bundles, urethra, and corporal and fascial layers. The patient was discharged with a suprapubic tube in place and a Foley catheter in place with well-healing tissue.

Main Outcome Measures

To review the current published literature and case reports on the management of penile amputation with particular emphasis its etiology, surgical repairs, potential complications and functional outcomes.

Results

We report herein a case of a traumatic penile amputation and successful outcome of microscopic reimplantation and review of the published literature with particular comments on surgical managements.

Conclusion

We review the literature and case reports on penile amputation and its etiology, surgical management, variables effecting outcomes, and its complications. Raheem OA, Mirheydar HS, Patel ND, Patel SH, Suliman A, and Buckley JC. Surgical management of traumatic penile amputation: A case report and review of the world literature. Sex Med 2015;3:49–53.

Keywords: Traumatic, Penile Amputation, Reimplantation

Introduction

Although penile amputation is a rare urologic emergency, it carries major functional and psychological consequences in regard to patient's overall quality of life. There is a paucity of case reports of traumatic penile amputation during circumcisions; however, most of the cases reported with self-mutilation are a result or severe substance-induced psychosis or underlying psychiatric disorder [1]. We herein describe a case of severe substance-induced psychosis that resulted in a complete self-amputation of the patient's penis.

Case Report

A 19-year-old single Caucasian male with no significant past medical or psychiatric history was presented to our university-affiliated trauma center with traumatic penile self-amputation. The patient brought in his distal penile stump placed on ice (>6 hours cold ischemic time) (Figures 1 and 2). The patient had used methamphetamine 4 days prior and developed severe psychosis episode. Earlier to patient's presentation, the patient had hand-masturbated for 12 hours leading to extensive penile skin friction, thinning, excoriation, and ultimately de-gloving, followed by intentional amputation of the penis at the base of the penis with a sharp blade due to auditory hallucinations while on methamphetamines.

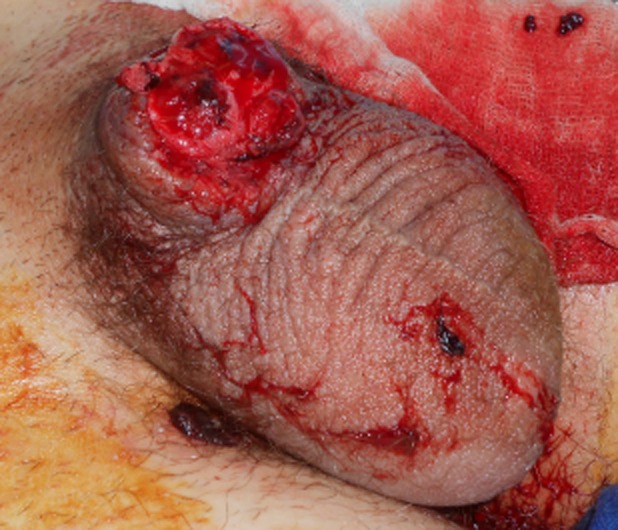

Figure 1.

Complete penile amputation at base of penis

Figure 2.

Amputated penis prior to reimplantation

Detailed discussion regarding surgical reimplantation of the amputated penile stump was undertaken. All risks, benefits, alternative treatments, and potential complications were discussed and formal consent was obtained. Subsequently, the patient was taken to the operating room and careful examination under anesthesia revealed fully and transversally transected urethra as well as corporal bodies at the level of penis base. The skin along the penile stump and amputated penis was intact with no evidence of ischemia or necrotic changes. Prophylactic intravenous third-generation cephalosporin antibiotics were given.

Meanwhile, the urology team began to perform a flexible cystourethroscopy into the posterior urethra, which identified normal posterior urethra, bladder neck, and bladder. The bladder was filled up and distended with sterile water and under direct visualization, we placed a 16 French percutaneous suprapubic catheter for urinary diversion. We began by placing four interrupted 3-0 Monocryl sutures through the tunica albuginea of the corporal bodies on the ventral aspect and snapped them for future tying. Next, we attached the urethra in a 360-degree fashion using interrupted 5-0 Monocryl sutures. Halfway through the anastomosis, we placed a 16 Silastic catheter with 8 mL of water into the bladder and completed the anastomosis. We had an excellent tension-free, widely spatulated urethral anastomosis. Attention was then turned into corporal bodies, which we reattached in interrupted fashion using a combination of 3 and 4-0 Monocryl sutures. We were very careful on the dorsal aspect near the vessels to just reapproximate the tunica albuginea and not interfere with the blood supply that required microvascular reanastomosis. Following this, the plastic surgeons performed microvascular reimplantation of amputated penis with approximation of the dorsal artery and dorsal vein as well as the dorsal sensory nerves. Adequate Doppler arterial flow and color were noted in the distal end of the anastomosis after microvascular reimplantation was accomplished successfully (Figure 3A and B).

Figure 3.

(A and B) Postoperative image shows re-anastomosed dorsal penile vessels and 16 French Foley catheter in place

The penis was then covered in bacitracin and xeroform gauze and scrotal support placed. Postoperatively, the patient had adequate flow to the distal end, with every 4-hour Doppler checks. During his postoperative course, he was under strict bed rest until postoperative day 12, with a scrotal support. The penis had significant edema and swelling in the distal penile shaft; however, sensation was gradually returning. Postoperative course was complicated by acute kidney injury, requiring temporary hemodialysis that gradually resolved. Psychiatry consult was also sought given the severity of the penile injury, and it was recommended to begin antipsychotics medications.

Approximately 4 weeks postoperatively, the patient was evaluated at urology clinic with good Doppler flow and excellent skin preservation and adequate wound healing (Figure 4). Serum creatinine was 1.15 and dialysis was no longer required. His follow-up retrograde urethrogram showed no contrast extravasations and complete urethral integrity. Suprapubic catheter was clamped and subsequently removed. At 4 months clinic follow-up, the patient continued satisfactory recovery and reported partial return of penile sensation and erection.

Figure 4.

Postoperative image (4 weeks) shows healing incisions and 16 French Foley catheter in place

Discussion

Penile amputation is a rare urologic emergency, with paucity of published data detailing best surgical measures and outcomes following penile reimplantation. Historically, earlier case reports were published in the mid 1800s and successful penile reimplantation was reported in 1926 [2]. Since then, there have been gradual rise of traumatic penile amputation with 87% of cases reported associated with an underlying psychotic disorder [1],[3]. A systematic review of the literature revealed approximately 80 cases reported worldwide of penile self-amputation from 1966 to 2007, with at least 30 successful penile reimplantation [4],[5]. Different weapons have been utilized in penile amputation cases, which range from sharp blades, heavy machinery to projectile objects.

Outcome measures for successful penile reimplantation have been widely varying and limiting the ability to clearly define a successful penile reimplantation of an amputated penis [5]. Adding to this, numerous factors contribute to the successful penile reimplantation outcomes often desirable to both physician and patient alike, which include the severity of the penile injury or amputation, type and mechanism of injury, team expertise available, duration of ischemia time, and use of a microscope at time of neurovascular bundle repair [6]. Table 1 summarizes the mechanism of injuries, weapon utilized, ischemia time, operative measures undertaken, and postoperative complications of various traumatic penile amputation case reports published in the literature. Exclusion criteria included case reports where non-English literature, penile reimplantation was not attempted and clinical or operative variables not reported.

Table 1.

List of published case reports of penile amputation

| Author/year | Weapon utilized | N | Ischemia time (hours) | Operative measures | Postoperative complications | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Suprapubic catheter placement (yes/no/NR) | Urethral anastomosis (primary/staged) | Corpora closure (yes/no/NR) | Microscope (yes/no/NR) | |||||

| Riyach et al. 2014 [7] | Blade | 1 | 6 | NR | Primary/interrupted | NR | No | Decreased penile sensation |

| Leyngold and Rivera-Serrano 2014 [8] | Blade | 1 | 12 | Yes | Primary, inferior epigastric artery bypass | Yes | Yes | Partial skin necrosis |

| El Harrech et al. 2013 [9] | Blade | 1 | 5 | Yes | Primary | Yes | No | Erectile dysfunction |

| Li et al. 2013 [10] | Blade | 109 | 6 | NR | Primary/interrupted | Yes | Yes | Skin necrosis, fistula formation |

| Roche et al. 2012 [11] | Blade | 1 | 6 | Yes | Primary/interrupted | Yes | Yes | Skin necrosis |

| Tazi et al. 2011 [12] | Blade | 1 | 4 | NR | Primary | Yes | Yes | NR |

| Salem and Mostafa 2009 [13] | Blade | 1 | 2 | NR | Primary/continuous | Yes | Yes | NR |

| Chou et al. 2008 [14] | Blade | 1 | 10 | NR | Staged | Yes | Yes | Skin necrosis |

| Landström et al. 2004 [15] | Blade | 1 | 9 | NR | Primary/interrupted | Yes | Yes | Skin infection |

| Darewicz et al. 1996 [16] | Blade | 1 | 10 | NR | Primary | Yes | Yes | Skin necrosis |

NR = not reported

In a systematic meta-analysis detailed by Li et al., a total of 109 patients with penile amputation were successfully reimplanted in China over a period of 48 years. In Li et al.'s study, total ischemia time was 6.3 ± 5.7 hours (range 1–38 hours). Among all cases, a total of 53/109 (49%) cases were performed by microscopic anastomosis. Postoperative complications identified were skin necrosis in 58 patients, penile sensation alteration in 31 patients, urethral strictures in 16 patients, erectile dysfunction in 14 patients, and urethral fistulae in 8 patients. Li et al.'s study concluded that there is an increased incidence of erectile dysfunction as well as urethral strictures in the patients where urethral/corporal/neurovascular bundle repair was performed without microscope. In addition, penile skin necrosis was negatively correlated with total number of anastomosed blood vessels (P < 0.05) [10].

Previous studies highlighted that when total ischemic time was kept less than 15 hours (mean time 7 hours), it associated with successful penile reimplant and outcomes (Table 1). Majority of cases have reported primary closure of the urethral and corporal bodies. Data on the utilization of the suprapubic catheter at time of penile reimplantation were lacking as 9/11 (82%) of case reports evaluated did not utilize suprapubic catheters. Previous published data have recommended temporary placement of suprapubic catheter at time of penile reimplant for urinary diversion purposes (Table 1). Most common complications reported in descending order were skin necrosis, decreased penile skin sensation, and erectile dysfunction (Table 1).

A study conducted by Landström et al. reported on a self-inflicted penile amputation at the level of pubic bone in a 38-year-old male with successful penile reimplantation. However, a postoperative pseudomonas wound infection was developed and treated successfully with hyperbaric oxygen therapy to prevent potential penile reimplant loss [15]. Jezior et al. reviewed 19 penile amputation injuries and found 4/19 (21%) patients had erectile dysfunction. In Jezior et al.'s study, erectile function seemed to be correlated with meticulous dorsal structures and cavernosal arteries approximation. However, the more distal penile injuries tend to be more technically difficult particularly with vascular anastomosis due to smaller vessels. If meticulous microvascular repair is not feasible, the penile and erectile tissues ischemia often develop and penile fibrosis ultimately sets in and eventually contributes to severe erectile dysfunction [4]. A consensus in the contemporary literature clearly acknowledges that the microsurgical revascularization and approximation of the penile shaft structures provide early and adequate restoration of penile blood flow with the best outcome of penile reimplant survival and erectile and voiding functions [4],[11],[17].

Conclusion

There are limited clinical data describing the surgical repair techniques employed in a penile reimplantation as well as their long-term outcomes and functional success. This can be partly explained by lack of the proper or accepted definitions of successful penile reimplantation. Historically, successful penile reimplantation is commonly measured by restoration of intact penile sensation, recovering erectile function, and/or absence of urethral strictures or urinary problems. Nevertheless, the primary goals for successful penile reimplantation are to minimize ischemia time, proper transport of distal penile segment, and transportation to a hospital with the surgical expertise and equipment to provide the patient with the best outcomes. Clearly, these measures and techniques, when applied together in timely fashion, would ultimately improve the patient's sexual and urinary functions, while maintaining best possible cosmosis. Future directions should be aimed to establish well-validated penile trauma algorithm with multidisciplinary surgical specialties platform to serve as a guide for the wider range of reconstructive urologists, plastics and trauma surgeons as well as other healthcare providers in both civilian trauma and warfare causality situations.

Conflict of Interest

The authors report no conflict of interest.

References

- Greilsheimer H, Groves JE. Male genital self-mutilation. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1979;36:441–446. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1979.01780040083009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salehipour M, Ariafar A. Successful replantation of amputated penile shaft following industrial injury. Int J Occup Environ Med. 2010;1:198–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simopoulos EF, Trinidad AC. Two cases of male genital self-mutilation: An examination of liaison dynamics. Psychosomatics. 2012;53:178–180. doi: 10.1016/j.psym.2011.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jezior JR, Brady JD, Schlossberg SM. Management of penile amputation injuries. World J Surg. 2001;25:1602–1609. doi: 10.1007/s00268-001-0157-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selby EA, Bender TW, Gordon KH, Nock MK, Joiner TE., Jr Non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) disorder: A preliminary study. Pers Disord. 2012;3:167–175. doi: 10.1037/a0024405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darewicz B, Galek L, Darewicz J, Kudelski J, Malczyk E. Successful microsurgical replantation of an amputated penis. Int Urol Nephrol. 2001;33:385–386. doi: 10.1023/a:1015226115774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riyach O, El Majdoub A, Tazi MF, El Ammari JE, El Fassi MJ, Khallouk A, Farih MH. Successful replantation of an amputated penis: A case report and review of the literature. J Med Case Rep. 2014;8:125. doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-8-125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leyngold MM, Rivera-Serrano CM. Microvascular penile replantation utilizing the deep inferior epigastric vessels. J Reconstr Microsurg. 2014;30:581–584. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1383427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Harrech Y, Abaka N, Ghoundale O, Touiti D. Genital self-amputation or the Klingsor syndrome: Successful non-microsurgical penile replantation. Urol Ann. 2013;5:305–308. doi: 10.4103/0974-7796.120309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li GZ, Man LB, He F, Huang GL. Replantation of amputated penis in Chinese men: A meta-analysis. Zhonghua Nan Ke Xue. 2013;19:722–726. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roche NA, Vermeulen BT, Blondeel PN, Stillaert FB. Technical recommendations for penile replantation based on lessons learned from penile reconstruction. J Reconstr Microsurg. 2012;28:247–250. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1306373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tazi MF, Ahallal Y, Khallouk A, Elfassi MJ, Farih MH. Spectacularly successful microsurgical penile replantation in an assaulted patient: One case report. Case Rep Urol. 2011:865489. doi: 10.1155/2011/865489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salem HK, Mostafa T. Primary anastomosis of the traumatically amputated penis. Andrologia. 2009;41:264–267. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0272.2009.00925.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou EK, Tai YT, Wu CI, Lin MS, Chen HH, Chang SC. Penile replantation, complication management, and technique refinement. Microsurgery. 2008;28:153–156. doi: 10.1002/micr.20470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landström JT, Schuyler RW, Macris GP. Microsurgical penile replantation facilitated by postoperative HBO treatment. Microsurgery. 2004;24:49–55. doi: 10.1002/micr.10192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darewicz J, Gatek L, Malczyk E, Darewicz B, Rogowski K, Kudelski J. Microsurgical replantation of the amputated penis and scrotum in a 29-year-old man. Urol Int. 1996;57:197–198. doi: 10.1159/000282912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biswas G. Technical considerations and outcomes in penile replantation. Semin Plast Surg. 2013;27:205–210. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1360588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]