Abstract

An acid–base switchable molecular shuttle based on a [2]rotaxane, incorporating stable radical units in both the ring and dumbbell components, is reported. The [2]rotaxane comprises a dibenzo[24]crown-8 ring (DB24C8) interlocked with a dumbbell component that possesses a dialkylammonium (NH2+) and a 4,4′-bipyridinium (BPY2+) recognition site. Deprotonation of the rotaxane NH2+ centers effects a quantitative displacement of the DB24C8 macroring to the BPY2+ recognition site, a process that can be reversed by acid treatment. Interaction between stable 2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidine-1-oxyl (TEMPO) radicals connected to the ring and dumbbell components could be switched between noncoupled (three-line electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectrum) and coupled (five-line EPR spectrum) upon displacement of the spin-labelled DB24C8 macroring. The complete base- and acid-induced switching cycle of the EPR pattern was repeated six times without an appreciable loss of signal, highlighting the reversibility of the process. Hence, this molecular machine is capable of switching on/off magnetic interactions by chemically driven reversible mechanical effects. A system of this kind represents an initial step towards a new generation of nanoscale magnetic switches that may be of interest for a variety of applications.

Keywords: EPR, molecular devices, rotaxane, spin labelling, supramolecular chemistry

Living organisms make extensive use of biomolecular machines to perform functions crucial for life.[1] A large variety of synthetic molecular machines exhibiting controlled displacement of their components has been produced in the past three decades,[2], [3] and laboratory demonstration of the potential utility of molecular machines in information and communication technology (ICT),[4] materials science,[5] catalysis,[6] and medicine[7] has been recently reported. Nevertheless, the exploitation of molecular movements to perform tasks is still a formidable research challenge, and more effort is necessary to extend the range of possible functionalities that may be accessed through the control of motion at the nanoscale.

An interesting possibility in this regard is the exploitation of molecular movements to enable or prevent distance-dependent processes. For example, mechanical switching of photoinduced intercomponent energy-, electron-, or charge-transfer processes has been observed in suitably designed systems.[8], [9] On the other hand, the efficiency of such processes can be used to measure distances at the molecular scale[10] and therefore monitor the operation of the system, as is routinely done with Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET) processes in mechanical devices based on nucleic acids.[3b]

Another intriguing option consists of incorporating radicals in the molecular components and using electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectroscopy to investigate changes in the magnetic properties as the device operates.[11] So far, spin labelling for intramolecular magnetic switching purposes has been mainly limited to photochromic compounds,[12] and mechanically interlocked molecules containing persistent radicals have only been used to carry out EPR-based co-conformational investigations.[13]

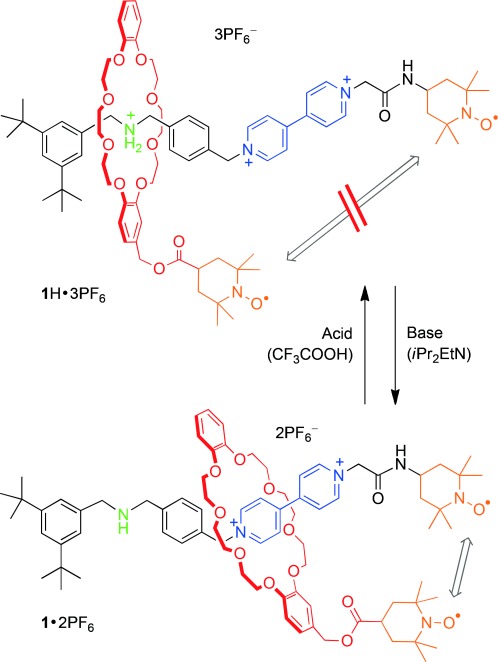

Herein we present the first example of an acid–base-controllable molecular shuttle in which through-space magnetic interactions between two mechanically interlocked nitroxide units can be switched on and off reversibly by chemical stimulation. The mechanical switch (Figure 1) is based on a well-known [2]rotaxane architecture[14] comprising a dibenzo[24]crown-8 (DB24C8) ring interlocked with a dumbbell component that possesses two different recognition sites, namely, a dialkylammonium (NH2+) and a 4,4′-bipyridinium (BPY2+) unit. A pair of stable 2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidine-1-oxyl (TEMPO) radicals are respectively attached to the ring and to one extremity of the dumbbell.

Figure 1.

Acid–base controlled shuttling in the examined rotaxane and schematic representation of the consequent change of distance between the two TEMPO radicals.

We envisaged that, in spite of the large (co-)conformational freedom of the rotaxane, the acid–base-driven displacement of the macrocycle between the NH2+ and BPY2+ stations[14] could bring the two TEMPO radicals close together or far apart, thus affecting their through-space magnetic interaction (Figure 1). The synthesis of rotaxane 1 H⋅3 PF6 and of its components 2 and 3 H⋅3 PF6 is outlined in Scheme 1. The TEMPO-functionalized DB24C8 derivative 2 was obtained in 70 % yield by condensation of the macrocyclic alcohol 4 with 4-carboxy-TEMPO 5 using N,N′-dicyclohexyl-carbodiimide (DCC) and 4-dimethylaminopyridine (DMAP) as the condensing reagents. The paramagnetic dumbbell 3 H⋅3 PF6 was prepared in 50 % yield by reacting the half-dumbbell 6 H⋅2 PF6 and the commercially available 4-(2-iodoacetamido)-TEMPO (7) in acetonitrile under reflux for 18 h followed by anion exchange.

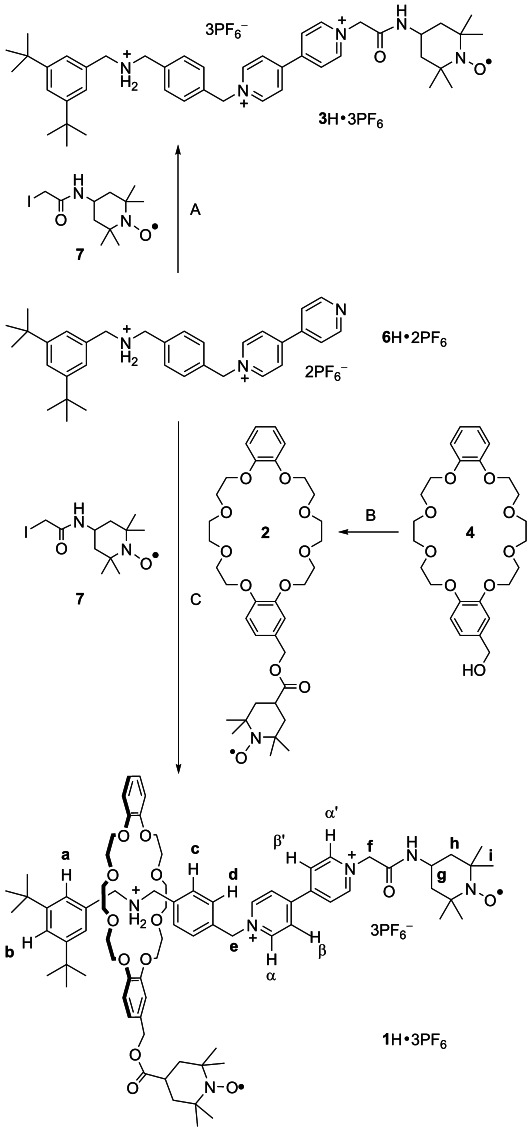

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of rotaxane 1 H⋅3 PF6. Reagents and conditions: A) CH3CN, NH4PF6, reflux, 18 h, 50 %; B) 4-carboxy-TEMPO (5), DMAP, DCC, CH2Cl2, rt, 24 h, 70 %; C) CHCl3, NH4PF6, reflux, 4 d, 30%.

To ensure that the TEMPO unit is large enough to behave as an efficient stopper for the DB24C8 ring, we initially studied the interlocking between the diamagnetic host 4 and the half-dumbbell 6 H⋅2 PF6. The reaction was carried out in chloroform to favor the formation of the hydrogen-bonded pseudorotaxane[14a,b], [4⊃6 H]⋅2 PF6, in which the ring encircles the NH2+ recognition site of 6 H2+, and the mixture was then held at reflux for four days in the presence of the paramagnetic stopper 7. The reaction progress was followed by thin-layer chromatography, and the corresponding [2]rotaxane was isolated in 30 % yield. The robustness of the mechanical link was checked by measuring a 1 D Rotating-Frame Nuclear Overhauser Effect Spectroscopy (ROESY) spectrum of the sample in CD3CN (see Supporting Information) following selective irradiation of the peak of methylene protons close to the ammonium site. The Nuclear Overhauser Effect (NOE) spectrum reveals significant host–guest enhancement of signals corresponding to the OCH2 protons of the ring, indicating that the NH2+ station is encircled by the crown ether and dethreading does not take place. Similarly, a threaded complex is not formed upon heating a mixture of 4 and dumbbell 3 H⋅3 PF6, confirming that the TEMPO moiety is a suitable stopper in the present system.

The target biradical rotaxane 1 H⋅3 PF6 was made by threading 6 H⋅2 PF6 with the radical-armed DB24C8 2 and using the TEMPO derivative 7 to introduce the second stopper (Scheme 1). Also, in this case, the reaction was monitored by thin-layer chromatography, and 1 H⋅3 PF6 was isolated in 30 % yield by means of a silica gel column and anion exchange. The interlocked nature of 1 H⋅3 PF6 was confirmed by 1H NMR spectroscopy (see Figure 2 a,b).

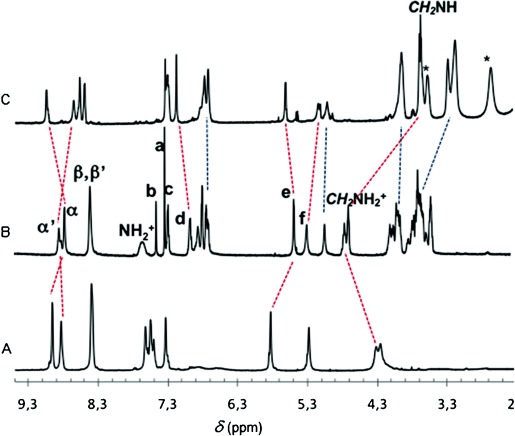

Figure 2.

Partial 1H NMR spectra (600 MHz, CD3CN, 298 K) of the dumbbell 3 H⋅3 PF6 (A), the rotaxane 1 H⋅3 PF6 (B), and the rotaxane 1⋅2 PF6 (C) (obtained from 1 H⋅3 PF6 after addition of iPr2EtN). Red dashed lines evidence the shift of guest protons caused by the movement of the paramagnetic crown ether, and blue dashed lines evidence the macrocycle signals. The signals marked with a star are relative to the protons of the amine.

The shuttling of the macrocycle towards the secondary BPY2+ station (Figure 1) was obtained by treating the 1 H⋅3 PF6 rotaxane in CD3CN with the non-nucleophilic Hünigs base, diisopropylethylamine (iPr2EtN), which is strong enough to deprotonate the NH2+ center.[14a] Replacement of the ring onto the ammonium station was triggered by addition of trifluoroacetic acid. The addition of iPr2EtN (2 equiv) caused the disappearance of CH2NH2+CH2 peaks in the 1H NMR spectrum of the rotaxane (Figure 2 B) which were replaced by new signals of lower frequencies ascribed to CH2NHCH2 protons (chemical shift δ∼3.7 ppm, Figure 2 C). Bipyridinium Hα’ and Hα undergo shifts of Δδ=−0.19 and +0.27 ppm respectively, and Hβ and Hβ’ show downfield shifts of Δδ=+0.09 and +0.19 ppm. A similar trend to Hα’ and Hα protons (shielding/deshielding, respectively, upon deprotonation) is also detected for the viologen-adjacent CH2 hydrogens (protons f and e), which undergo shifts Δδ=−0.15 and +0.13 ppm, respectively.

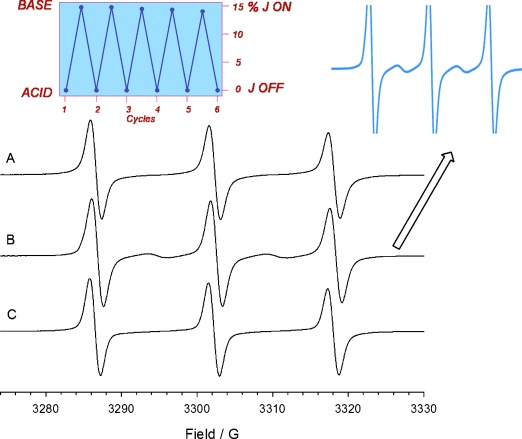

The 1H NMR spectrum recorded after the successive addition of CF3COOH was superimposable to the original one (Figure 2 B), indicating that the ring shuttles back to the NH2+ station and highlighting the reversibility of the switching process.[14] An important result of these experiments is that the radical centers do not interfere with the movement of the ring. Finally, the changes in the magnetic interaction between the two TEMPO radical units of rotaxane 1 H⋅3 PF6, brought about by the shuttling motion of the macrocyclic ring, were monitored by EPR spectroscopy. A three-line spectrum (g=2.0060, aN=15.75 G) typical of an isolated TEMPO was observed when the macrocycle is located on the NH2+ station (Figure 3 A). This observation indicates the absence of significant spin coupling between the two radicals, suggesting their spatial separation in the starting co-conformations is relatively large (Figure 1). Upon addition of iPr2EtN, the EPR spectrum showed a noticeable change from a three- to a five-line spectrum, retaining the same aN value (15.75 G) (Figure 3 B). Conversely, the same addition performed on a 1:1 mixture of the non-interlocked rotaxane components (2 and 3 H⋅3 PF6) did not cause variations in the EPR signals. Such a control experiment confirms that the observed EPR changes arise from through-space radical–radical interactions which become possible as a result of ring shuttling in the deprotonated rotaxane.

Figure 3.

Room temperature EPR spectra of rotaxane 1 H⋅3 PF6 (0.15 mm) before (A) and after sequential addition of 2 equiv iPr2EtN (B) and CF3COOH (C). Right inset: enlargement of spectrum B showing exchange lines. Left inset: co-conformations (%) showing spin-exchange as function of sequential acid–base additions.

The ratio of line intensities, however, differs substantially from the 1:2:3:2:1 pattern expected in case all the (co-)conformations of the [2]rotaxane were characterized by strong spin-exchange between the nitroxide units. The combination of three- and five-line EPR patterns observed after addition of iPr2EtN is due to the overlap of the signals arising from 1) biradicals in which the two spin labels are too far apart to interact (three-line spectrum), and 2) biradicals in with the TEMPO moieties are sufficiently close to undergo exchange coupling (five-line spectrum). By measuring the relative EPR line intensities,[13b] we could estimate that, in acetonitrile at 298 K, about 15 % of the deprotonated rotaxane molecules assume (co-)conformations such as that shown schematically in Figure 1, bottom, in which the two nitroxide units are sufficiently close to one another to allow a strong electron exchange (J≫aN). Such behavior is a consequence of the relatively large flexibility of the connectors that link the TEMPO centers to the rotaxane components and of the (co-)conformational degrees of freedom of the ring and dumbbell relative to each another. More rigid systems are required to exploit the distance effect on through-space spin exchange interactions in a better way. The addition of a stoichiometric amount of trifluoroacetic acid after the addition of the base caused the quantitative recovery of the initial three-line EPR spectrum (Figure 3 C) as a consequence of the replacement of the macrocyclic ring to the ammonium station. The complete base- and acid-induced switching cycle of the EPR pattern was repeated for six times without an appreciable loss of signal, highlighting the reversibility of the process (see inset of Figure 3). Similar EPR results were also observed at a higher temperature (328 K).

In summary, we have developed an acid–base switchable molecular shuttle based on a [2]rotaxane, incorporating stable radical units in both the ring and dumbbell components. The chemically driven shuttling motion was exploited to reversibly change the distance between the two spin centers, thereby enabling or preventing through-space electron exchange interactions that can be measured by EPR spectroscopy. Hence, this molecular machine is capable of switching on/off magnetic interactions by chemically driven reversible mechanical effects. A system of this kind can represent a first step towards a new generation of nanoscale magnetic switches that may be of interest for information and communication technology applications.[15] Spin labelling in molecular machines is also interesting because correlations between radical pairs, monitored by pulsed EPR methods, enable detailed conformational analyses, dynamics studies, and precise measurements of nanoscale distances.[13] Hence, they represent a powerful tool to increase our understanding of the intricate operation mechanisms of molecular machines. Experiments in this direction are underway in our laboratories.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Italian Ministry of Education, University and Research (PRIN 2010CX2TLM InfoChem, PRIN MULTINANOITA) and the University of Bologna (Finanziamenti di Ateneo alla Ricerca di Base, SLaMM Project).

Supporting Information

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re-organized for online delivery, but are not copy-edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supplementary

References

- Jones RAL. Soft machines: Nanotechnology and Life. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Balzani V, Credi A, Venturi M. Molecular Devices and Machines-Concepts and Perspectives for the Nanoworld. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kay ER. Leigh DA. Zerbetto F. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007;46:72–191. doi: 10.1002/anie.200504313. Angew. Chem. 2007, 119, 72–196; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan Y. Simmel FC. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011;50:3124–3156. doi: 10.1002/anie.200907223. Angew. Chem. 2011, 123, 3180–3215; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coskun A. Banaszak M. Astumian RD. Stoddart JF. Grzybowskin BA. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012;41:19–30. doi: 10.1039/c1cs15262a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Dongen SFM. Cantekin S. Elemans JAAW. Rowan AE. Nolte RJM. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014;43:99–122. doi: 10.1039/c3cs60178a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coskun A, Spruell JM, Barin G, Dichtel WR, Flood AH, Botros YY, Stoddart JF. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012;41:4827–4859. doi: 10.1039/c2cs35053j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vukotic NV. Harris KJ. Zhu K. Schurko RW. Loeb SJ. Nat. Chem. 2012;4:456–460. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobr L. Zhao K. Shen Y. Comotti A. Bracco S. Shoemaker RK. Sozzani P. Clark NA. Price JC. Rogers CT. Michl J. Chem J. Am. Soc. 2012;134:10122–10131. doi: 10.1021/ja302173y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du G. Moulin E. Jouault N. Buhler E. Giuseppone N. Int Angew. Chem. Ed. 2012;51:12504–12508. doi: 10.1002/anie.201206571. Angew. Chem. 2012, 124, 12672–12676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iamsaard S. Aβhoff SJ. Matt B. Kudernac T. Cornelissen JJLM. Fletcher SP. Katsonis N. Nat. Chem. 2014;6:229–235. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang X. Rodríguez-Molina B. Nazarian M. Garcia-GaribayChem M. J. Am. Soc. 2014;136:8871–8874. doi: 10.1021/ja503467e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berná J. Alajarin M. Orenes RA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:10741–10747. doi: 10.1021/ja101151t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J. Feringa BL. Science. 2011;331:1429–1432. doi: 10.1126/science.1199844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Dongen SFM. Clerx J. Nørgaard K. Bloemberg TG. Cornelissen JJLM. Trakselis MA. Nelson SW. Benkovic SJ. Rowan AE. Nolte RJM. Nat. Chem. 2013;5:945–951. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco V. Leigh DA. Marcos V. Morales-Serna JA. Nussbaumer AL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:4905–4908. doi: 10.1021/ja501561c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z. Barnes JC. Bosoy A. Stoddart JF. Zink JI. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012;41:2590–2605. doi: 10.1039/c1cs15246g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z. Balogh D. Wang FA. Sung SY. Nechushtai R. Willner I. ACS Nano. 2013;7:8455–8468. doi: 10.1021/nn403772j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma X. Tian H. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2010;39:70–80. doi: 10.1039/b901710k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mateo-Alonso A. Chem. Commun. 2010;46:9089–9099. doi: 10.1039/c0cc03724a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez EM. Dryden DTF. Leigh DA. Teobaldi G. Zerbetto F. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:12210–12211. doi: 10.1021/ja0484193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y. Li H. Li Y. Liu H. Wang S. He X. Wang N. Zhu D. Org. Lett. 2005;7:4835–4838. doi: 10.1021/ol051567t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrer B. Rogez G. Credi A. Ballardini R. Gandolfi MT. Balzani V. Liu Y. Tseng H-R. Stoddart JF. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:18411–18416. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606459103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collin J-P. Frey J. Heitz V. Sauvage J-P. Tock C. Allouche L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:5609–5620. doi: 10.1021/ja900565p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou W. Zhang S. Li G. Zhao Y. Shi Z. Liu H. Li Y. Chem Phys Chem. 2009;10:2066–2072. doi: 10.1002/cphc.200900228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasabe H. Sandanayaka ASD. Kihara N. Furusho Y. Takata T. Araki Y. Ito O. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2009;11:10908–10911. doi: 10.1039/b913966d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang O. Zhang H-Y. Han M. Ding Z-J. Liu Y. Org. Lett. 2010;12:1728–1731. doi: 10.1021/ol100321k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H. Zhou B. Li H. Qu D. Tian H. J. Org. Chem. 2013;78:2091–2098. doi: 10.1021/jo302107a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mateo-Alonso A. Ehli C. Rahman GMA. Guldi DM. Fioravanti G. Marcaccio M. Paolucci F. Prato M. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007;46:3521–3525. doi: 10.1002/anie.200605039. Angew. Chem. 2007, 119, 3591–3595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onagi H, Jr, Rebek J. Chem. Commun. 2005:4604–4606. doi: 10.1039/b506177f. , . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EPR spectroscopy proved to be a powerful technique to study electron-transfer processes in supramolecular or mechanically interlocked compounds. See, for example:

- See, for example:

- Jeschke G. Godt A. ChemPhysChem. 2003;4:1328–1334. doi: 10.1002/cphc.200300890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mileo E. Casati C. Franchi P. Mezzina E. Lucarini M. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2011;9:2920–2026. doi: 10.1039/c0ob01160f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pievo R. Casati C. Franchi P. Mezzina E. Bennati M. Lucarini M. ChemPhysChem. 2012;13:2659–2661. doi: 10.1002/cphc.201200103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casati C. Franchi P. Pievo R. Mezzina E. Lucarini M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:19108–19117. doi: 10.1021/ja3073484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Díaz M-V. Spencer N. Stoddart JF. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 1997;36:1904–1907. Angew. Chem. 1997, 109, 1991–1994; [Google Scholar]

- Ashton PR. Ballardini R. Balzani V. Baxter I. Credi A. Fyfe MCT. Gandolfi MT. Gómez-López M. Martínez-Díaz M-V. Piersanti A. Spencer N. Stoddart JF. Venturi M. White AJP. Williams DJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998;120:11932–11942. [Google Scholar]

- Garaudée S. Silvi S. Venturi M. Credi A. Stoddart JF. ChemPhysChem. 2005;6:2145–2152. doi: 10.1002/cphc.200500295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato O, Tao J, Zhang Y. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 46:2152–2187. doi: 10.1002/anie.200602205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2007;119 , and references therein. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary