Abstract

Purpose

Pegfilgrastim is a pegylated form of filgrastim, a recombinant protein of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor, that is used to reduce the risk of febrile neutropenia (FN). Here, we report the results of a phase III trial of pegfilgrastim in breast cancer patients receiving docetaxel and cyclophosphamide (TC) chemotherapy.

Methods

We conducted a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized trial to determine the efficacy of pegfilgrastim in reducing the risk of FN in early-stage breast cancer patients. A total of 351 women (177 in the pegfilgrastim group and 174 in the placebo group) between 20 and 69 years of age with stage I–III invasive breast carcinoma who were to receive TC chemotherapy (docetaxel 75 mg/m2 and cyclophosphamide 600 mg/m2 every 3 weeks) as either neoadjuvant or adjuvant therapy were enrolled; 346 of these patients were treated with either pegfilgrastim (n = 173) or placebo (n = 173).

Results

The incidence of FN was significantly lower in the pegfilgrastim group than in the placebo group (1.2 vs. 68.8 %, respectively; P < 0.001). In addition, patients in the pegfilgrastim group required less hospitalization and antibiotics for FN. Most adverse events were consistent with those expected for breast cancer subjects receiving TC chemotherapy.

Conclusions

Pegfilgrastim is safe and significantly reduces the incidence of FN in breast cancer patients.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s00520-014-2597-1) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Adjuvant therapy, Breast cancer, Febrile neutropenia, Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF), Pegfilgrastim, Docetaxel/cyclophosphamide therapy

Introduction

Febrile neutropenia (FN) is a potentially life-threatening condition characterized by the development of fever in addition to chemotherapy-induced neutropenia. With a longer duration of neutropenia, the risk of contracting FN is greater [1]. FN risk can be mitigated by reducing chemotherapy dosages or extending dosing intervals. However, these measures also reduce the relative dose intensity of chemotherapy and, consequently, survival rates. Therefore, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) is often administered to manage chemotherapy-associated FN [2, 3] and to allow anticancer drugs to be administered more effectively. Guidelines for the use of G-CSF based on the risk of FN have been established by several groups [4–7]. According to these guidelines, prophylactic G-CSF use is recommended for patients with a clinically significant risk of FN, based on regimen and patient-specific risk factors.

Pegfilgrastim, a pegylated form of filgrastim, has a long half-life in circulation. A phase III placebo-controlled, double-blind, randomized trial of pegfilgrastim in patients with breast cancer who received docetaxel in Europe and North America demonstrated that it significantly reduces the incidence of FN, FN-related hospitalization, and the use of antibiotics [8]. Therefore, pegfilgrastim has been approved in many countries to prevent FN. However, since it has not yet been approved in Japan, a phase II trial of pegfilgrastim in breast cancer patients receiving docetaxel, doxorubicin, and cyclophosphamide chemotherapy was conducted. The trial demonstrated that pegfilgrastim was safe, and based on the duration of severe neutropenia, a surrogate endpoint of FN incidence, 3.6 mg subcutaneous administration once per chemotherapy cycle is the recommended dose for further development [9]. On the basis of these studies, we conducted a phase III clinical trial of pegfilgrastim in patients with breast cancer receiving docetaxel and cyclophosphamide (TC) chemotherapy, a standard treatment regimen for primary breast cancer [10]. The primary endpoint was the percentage of patients who developed FN. FN incidence without G-CSF was also of interest to determine the need for the prophylactic use of G-CSF, as guidelines commonly recommend such use for regimens with an FN incidence of ≥20 % [4–7].

Materials and methods

Eligibility criteria

The inclusion criteria were as follows: women aged 20–69 years, pathological and clinical stage I–III primary invasive breast carcinoma, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status 0–2, no prior chemotherapy, absolute neutrophil count (ANC) ≥1500/μL, platelet count ≥100,000/μL, hemoglobin concentration ≥10 g/dL, aspartate aminotransferase and alanine aminotransferase levels ≤3 times the upper limit of normal in each institute, total bilirubin level ≤1.5 times the upper limit of normal, creatinine level ≤1.5 mg/dL, and negative hepatitis B status. Exclusion criteria were cardiac failure, a history of radiation therapy within 4 weeks of enrollment, other concomitant cancers, or bilateral breast cancer. All patients provided informed consent before study procedures were performed, and the protocol was approved by institutional review boards.

Study design

This was a phase III, multicenter (50 sites), double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized trial conducted in Japan. Patients were stratified by investigational site and chemotherapy status (neoadjuvant or adjuvant) and then randomized in a 1:1 ratio using a dynamic allocation method into either the pegfilgrastim or placebo cohort.

Procedures

All patients received 4–6 3-week cycles of TC chemotherapy. On day 1 of each cycle, patients were administered docetaxel (75 mg/m2) and cyclophosphamide (600 mg/m2) intravenously. If a chemotherapy cycle was delayed by more than 3 weeks, the patient was withdrawn from the study. If a critical adverse event (AE) occurred during chemotherapy and a dose reduction was deemed necessary, the dosage of each drug was reduced by 20 % in the next cycle. A dose reduction was allowed only once.

Pegfilgrastim and placebo were both supplied in vials as clear, colorless, sterile protein solutions. On day 2 of each cycle (≥24 h after chemotherapy), patients received a single subcutaneous injection of either pegfilgrastim (3.6 mg) or placebo in a double-blind manner. Use of the 3.6 mg dose was based on findings from Masuda and colleagues, who noted that the 3.6 mg dose was effective in reducing the incidence of FN in Japanese patients who received TAC (docetaxel, doxorubicin, and cyclophosphamide) chemotherapy [9]. Patients who developed protocol-defined FN (defined as an ANC <500/μL and axillary temperature ≥37.5 °C on the same day or the following day) were allowed to continue treatment with pegfilgrastim under open-label conditions.

The prophylactic use of antibiotics was prohibited until the first episode of FN was documented. G-CSF treatment was prohibited; however, rescue treatment was allowed when protocol-defined FN occurred. Corticosteroids and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs were also prohibited, except for AE treatment. However, administration of dexamethasone by day 3 of each cycle was allowed to counteract side effects of TC chemotherapy.

Blood samples were obtained from all patients. Complete blood counts were obtained on days 1, 2, 8, 11, and 15 of the first cycle; on days 1, 2, 8, and 11 of the subsequent cycles administered in a double-blind manner; and on days 1 and 2 of cycles of open-label treatment. Furthermore, at the beginning and end of the study, serum was analyzed to detect the presence of antibodies against either pegfilgrastim or filgrastim.

The axillary body temperature of all patients was measured every day. Patients who were being treated in a double-blind manner and had an elevated body temperature (≥37.5 °C) were required to have a complete blood count by the next day.

Efficacy

The primary endpoint was the percentage of patients who developed protocol-defined FN. Secondary endpoints included incidence of FN in the first cycle of chemotherapy, incidence of grade 4 neutropenia, incidence of FN-related hospitalization, and percentage of patients treated with antibiotics for FN.

Safety

Safety assessments were based on AE reports, abnormal laboratory values, and vital signs. AEs were defined by the Japanese version of the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities and graded according to the National Cancer Institute’s Common Toxicity Criteria (version 4.0).

Statistical analyses

The sample size was determined based on the ability to detect a statistically significant difference with a power of 80 % and achieve a two-sided significance level of 5 % by the χ2 test. Based on previous clinical trials, we assumed that 10.3 % of the patients in the pegfilgrastim cohort and 23 % of the patients in the placebo cohort would develop FN [9, 11–16]. We also expected approximately 10 % of all patients to be excluded or withdrawn from the study. Therefore, target recruitment was at least 150 patients per cohort.

The primary endpoint was analyzed using the full analysis set, which included patients who were treated with pegfilgrastim at least once. Safety assessments were analyzed using the safety analysis set, which included subjects treated with pegfilgrastim at least once. Only the data from patients who were treated in a double-blind manner were analyzed in terms of efficacy and safety. Secondary endpoints were analyzed using the χ2 test. All statistical analyses were performed using Statistical Analysis Software (version 9.2; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

Patients

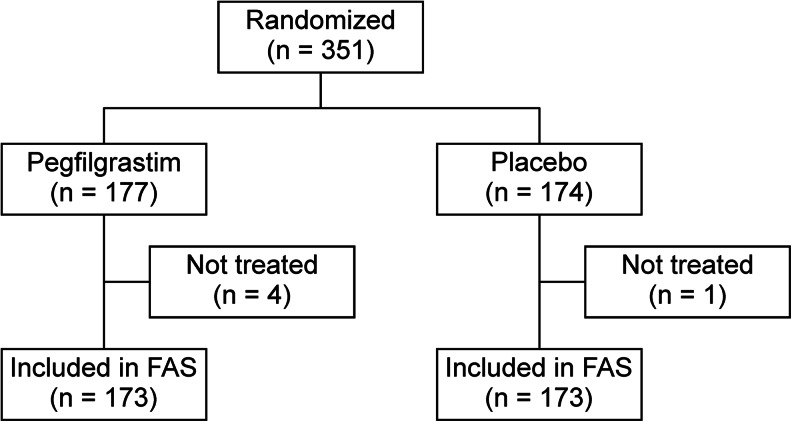

Between April 2011 and February 2012, 351 Japanese women with breast cancer were recruited and randomly assigned to the treatment groups, resulting in 177 patients in the pegfilgrastim group and 174 in the placebo group. One patient in the pegfilgrastim group withdrew from the study because she could not start chemotherapy within 14 days of the screening test. In addition, three patients from the pegfilgrastim group and one patient from the placebo group were removed from the study at the discretion of the investigators, leaving 173 patients in each group (Fig. 1). As shown in Table 1, patient characteristics were balanced in both groups. Three patients received an overdose of pegfilgrastim; one patient randomized to the pegfilgrastim group received 10.0 mg of pegfilgrastim in the first cycle, and two patients received 10.0 mg in the first and second cycles. These patients were included in the original full analysis set and safety analysis set.

Fig. 1.

Patient allocation and disposition. FAS full analysis set

Table 1.

Summary of demographic and baseline characteristics for patients in the full analysis set (FAS)

| Pegfilgrastim | Placebo | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 173) | (n = 173) | ||||

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Age (years) | Median | 51.0 | 50.0 | ||

| Range | 26–69 | 27–69 | |||

| <65 | 153 | 88.4 | 156 | 90.2 | |

| ≥65 | 20 | 11.6 | 17 | 9.8 | |

| Body weight (kg) | Mean (SD) | 56.0 (9.9) | 55.0 (7.6) | ||

| <60 | 123 | 71.1 | 131 | 75.7 | |

| ≥60 | 50 | 28.9 | 42 | 24.3 | |

| Body surface area (m2) | Mean (SD) | 1.55 (0.13) | 1.54 (0.11) | ||

| Chemotherapy | Neoadjuvant | 24 | 13.9 | 22 | 12.7 |

| Adjuvant | 149 | 86.1 | 151 | 87.3 | |

| Primary disease | Infiltrating ductal carcinoma | 158 | 91.3 | 153 | 88.4 |

| Special type | 12 | 6.9 | 19 | 11.0 | |

| Other | 3 | 1.7 | 1 | 0.6 | |

| Clinical stage | I | 64 | 37.0 | 56 | 32.4 |

| II | 97 | 56.1 | 105 | 60.7 | |

| III | 12 | 6.9 | 12 | 6.9 | |

| Lymph node involvement | pN0 | 101 | 58.4 | 94 | 54.3 |

| pN (+) | 72 | 41.6 | 77 | 44.5 | |

| Unknown | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 1.2 | |

| Hormone receptor status | ER negative | 35 | 20.2 | 42 | 24.3 |

| ER positive | 138 | 79.8 | 131 | 75.7 | |

| PgR negative | 60 | 34.7 | 60 | 34.7 | |

| PgR positive | 113 | 65.3 | 113 | 65.3 | |

| HER2 negative | 60 | 34.7 | 60 | 34.7 | |

| HER2 positive | 113 | 65.3 | 113 | 65.3 | |

ER estrogen receptor, PgR progesterone receptor, HER2 human epidermal growth factor receptor 2, SD standard deviation

At the end of the first, second, and third cycles of chemotherapy, 94, 10, and seven patients in the placebo group, respectively, were permitted to receive open-label pegfilgrastim treatment after experiencing FN. In contrast, only two patients in the pegfilgrastim group made this change during this time. No other changes in patient disposition were observed during the study.

Efficacy

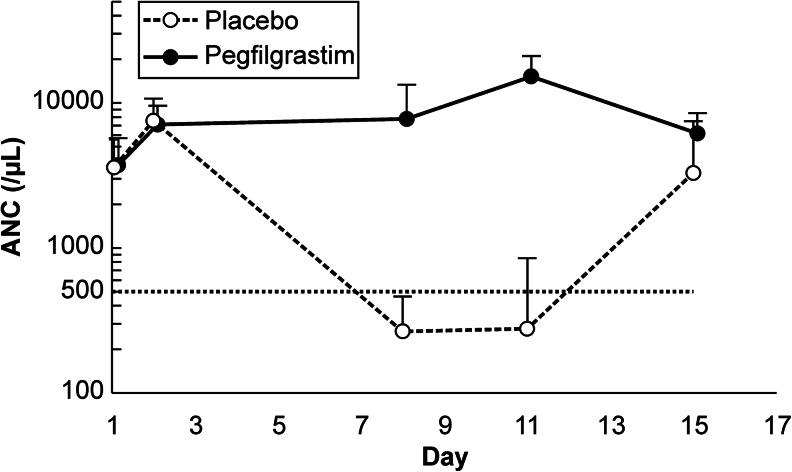

The primary endpoint, the incidence of FN during all cycles of chemotherapy, differed significantly between the pegfilgrastim (2/173; 1.2 %) and placebo (119/173; 68.8 %) groups (P < 0.001) (Table 2). Similarly, differences in other secondary endpoints were also significant (P < 0.05). First, during the first chemotherapy cycle, FN occurred in one patient (0.6 %) in the pegfilgrastim group and in 100 patients (57.8 %) in the placebo group (P < 0.001). Second, only seven patients (4.0 %) in the pegfilgrastim group developed grade 4 neutropenia during all chemotherapy cycles, whereas all 173 patients in the placebo group progressed to grade 4 neutropenia during the same time (P < 0.001). Changes in ANC during the first cycle of chemotherapy are shown in Fig. 2. Third, no patients in the pegfilgrastim group required FN-related hospitalization, whereas 12/173 patients (6.9 %) in the placebo group did (P < 0.001). Fourth, fewer patients required antibiotics to treat FN in the pegfilgrastim group (1/173; 0.6 %) than in the placebo group (98/173; 56.6 %; P < 0.001).

Table 2.

Incidence of febrile neutropenia (FN), FN-related hospitalization, and use of antibiotics to treat FN in the full analysis set for all chemotherapy cycles

| Pegfilgrastim (n = 173) |

Placebo (n = 173) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | P value | |

| Patients with FN | 2 | 1.2 | 119 | 68.8 | <0.001 |

| Patients with FN-related hospitalization | 0 | 0 | 12 | 6.9 | <0.001 |

| Patients treated with antibiotics | 1 | 0.6 | 98 | 56.6 | <0.001 |

Fig. 2.

Changes in absolute neutrophil counts during the first cycle of chemotherapy for patients in the full analysis set. Data points and error bars indicate the mean and standard deviation of 173 measurements, respectively. The horizontal dashed line marks an absolute neutrophil count (ANC) of 500/μL. Open circles denote values for the placebo group, whereas closed circles denote values for the pegfilgrastim group

Subgroup analysis revealed that elderly patients in the placebo group tended to have a higher risk than younger patients for developing FN. Among patients aged <65 years, 66.7 % developed FN, whereas 88.2 % of those aged ≥65 years developed FN.

We did not detect any antibodies to pegfilgrastim or filgrastim in any patient.

Safety

AEs occurred in all patients; however, most were expected from the chemotherapy regimen, and none were severe enough to result in death. During the first cycle of chemotherapy, grade 3 or 4 hematologic AEs were more frequently observed in the placebo group than in the pegfilgrastim group (Online Resource 1). No patients developed grade 3 or 4 thrombocytopenia or anemia during all chemotherapy cycles. Non-hematologic AEs occurred in ≥10 % of patients during the first cycle of chemotherapy (Online Resource 2). Blood lactate dehydrogenase levels increased, and pyrexia was more frequent in the pegfilgrastim group than in the placebo group. After overdosing, drug-related AEs were observed in two patients during chemotherapy cycles. However, these AEs were grade 1 and resolved without any treatment.

Regarding bone and back pain, common AEs of G-CSF treatment, the incidence rates of bone pain in the pegfilgrastim and placebo groups were 6.4 and 2.3 %, respectively, and the incidence rates of back pain were 19.1 and 15.0 %, respectively. These AEs were manageable with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. No patients were withdrawn from the study due to intractable pain.

Discussion

This phase III trial showed that pegfilgrastim reduces the risk of FN in breast cancer patients who receive TC chemotherapy by 98 %, consistent with a previous trial that showed that pegfilgrastim is more effective than placebo in reducing FN risk in breast cancer patients who receive docetaxel [8]. Our finding that most FN cases occurred during the first cycle of chemotherapy is consistent with other studies [8, 17]; therefore, we concluded that pegfilgrastim should be administered from the first cycle of chemotherapy to achieve effective FN prophylaxis.

When this trial was planned, the incidence of TC chemotherapy-induced FN without G-CSF treatment was controversial. The clinical trial conducted by the US Oncology group reported a 5 % FN incidence and a 51 % incidence of grade 4 neutropenia [10], while a meta-analysis of 902 patients treated with TC demonstrated that the pooled estimate of FN incidence, in the absence of G-CSF, was 29 % (95 % confidence interval, 24–35 %) [18]. Previous studies in Japan confirmed these meta-analysis findings, as they showed that the incidence of FN was >20 % and that of grade 4 neutropenia was >70 % [13, 14]. The definition of FN in terms of body temperature differs slightly in different countries; for example, FN is defined as an axillary temperature ≥37.5 °C in Japanese guidelines and as an oral temperature ≥38.3 °C or 38.0 °C over 1 h in the US guidelines [5, 19]. This difference, however, can be considered negligible from a clinical point of view and does not significantly impact the results. Therefore, we selected the percentage of patients who developed FN during all chemotherapy cycles as the primary endpoint of our trial. However, the 68.8 % FN incidence in our trial is still much higher than the incidence observed in the US trial [10]. In addition, all patients in the placebo group of our trial developed grade 4 neutropenia. One possible reason for these differences may be that patients in these clinical trials did not undergo hematology tests frequently enough to observe the ANC nadir. In our trial, patients who were treated in a double-blind manner were required to undergo hematology tests on days 8 and 11, when the ANC nadir was expected to occur, as well as immediately after any occurrence of fever. Further, ethnic differences may contribute significantly to such differences, because Asians tend to have a higher risk of FN than Caucasians [20, 21]. Nevertheless, our results support the conclusion that the prophylactic use of pegfilgrastim reduces the FN risk in Japanese breast cancer patients who receive TC chemotherapy, consistent with current National Comprehensive Cancer Network breast cancer guidelines that recommend the use of G-CSF with TC chemotherapy.

We assessed the incidence of FN-related hospitalization and use of antibiotics to treat FN as secondary endpoints to evaluate the benefit of pegfilgrastim for outpatient chemotherapy, which is now common in Japan. However, patients are required to visit hospitals to receive a shot of G-CSF every day to alleviate profound neutropenia. Furthermore, hospitalization or antibiotic use is required once FN occurs. Our results indicate that single-administration pegfilgrastim reduces the need for both FN-related hospitalization and antibiotics to treat FN; therefore, pegfilgrastim is expected to facilitate outpatient chemotherapy, reduce hospitalization costs, and improve the quality of life of cancer patients, reducing the burden of receiving daily administrations.

Most AEs that occurred in this study were primarily related to chemotherapy. AEs such as bone pain, back pain, and increased serum lactate dehydrogenase levels were more frequent in the pegfilgrastim group; however, no new safety concerns were identified.

In conclusion, this phase III trial demonstrated that pegfilgrastim is safe and effective for significantly reducing FN incidence in Japanese breast cancer patients who receive TC chemotherapy. We expect that the prophylactic use of pegfilgrastim will provide numerous clinical and economic benefits for not only cancer patients but also for cancer treatment in Japan.

Electronic supplementary material

(PDF 16 kb)

(PDF 17 kb)

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all of the patients who participated in this study and their families, as well as investigators, research nurses, study coordinators, and operations staff.

Study participants: Drs. Masato Takahashi (Hokkaido Cancer Center, Sapporo); Masahiro Kashiwaba (Iwate Medical University, Morioka); Shun Kudo (Yamagata Prefectural Central Hospital, Yamagata); Hisato Hara (University of Tsukuba, Tsukuba); Ei Ueno (Total Health Evaluation Center Tsukuba, Tsukuba); Jiro Ando (Tochigi Cancer Center, Utsunomiya); Yasuo Hozumi (Jichi Medical University, Shimono); Jun Horiguchi (Gunma University, Maebashi); Yasuhiro Yanagida (Gunma Prefectural Cancer Center, Maebashi); Toshiaki Saeki (Saitama Medical University International Medical Center, Hidaka); Hideki Tsujimura (Chiba Cancer Center, Chiba); Eisuke Fukuma (Kameda Medical Center, Kamogawa); Chizuko Shiga (Teikyo University, Tokyo); Katsumasa Kuroi (Tokyo Metropolitan Komagome Hospital, Tokyo); Hideko Yamauchi (St. Luke’s International Hospital, Tokyo); Masashi Ando (National Cancer Center Hospital, Tokyo); Toshimi Takano (Toranomon Hospital, Tokyo); Seigo Nakamura (Showa University, Tokyo); Shigeru Imoto (Kyorin University, Tokyo); Hitoshi Arioka (Yokohama Rosai Hospital, Yokohama); Takashi Ishikawa (Yokohama City University Medical Center, Yokohama); Satoru Shimizu (Kanagawa Cancer Center, Yokohama); Masaru Kuranami, Norihiko Sengoku (Kitasato University School of Medicine, Sagamihara); Yutaka Tokuda (Tokai University, Isehara); Nobuaki Sato (Niigata Cancer Center Hospital, Niigata); Hiroji Iwata (Aichi Cancer Center Central Hospital, Nagoya); Yasuhiro Kurumiya (Nagoya Daini Red Cross Hospital, Nagoya); Tatsuya Toyama, Hiroko Yamashita (Nagoya City University, Nagoya); Yasuyuki Sato (Nagoya Medical Center, Nagoya); Satoshi Tamaru (Mie University, Tsu); Tetsuya Taguchi (Kyoto Prefectural University of Medicine, Kyoto); Takashi Morimoto (Yao Municipal Hospital, Yao); Norikazu Masuda (Osaka National hospital, Osaka); Shigeru Tsuyuki (Osaka Red Cross Hospital, Osaka); Katsuhide Yoshidome (Osaka Police Hospital, Osaka); Nobuki Matsunami (Osaka Rosai Hospital, Sakai); Shunji Kamigaki (Sakai Municipal Hospital, Sakai); Chiyomi Egawa (Kansai Rosai Hospital, Amagasaki); Yasuo Miyoshi (Hyogo College of Medicine, Nishinomiya); Hiroyoshi Doihara (Okayama University, Okayama); Kenji Higaki (Hiroshima City Hospital, Hiroshima); Shigeru Murakami (Hiroshima City Asa Hospital, Hiroshima); Kenjiro Aogi (Shikoku Cancer Center, Matsuyama); Keisei Anan (Kitakyushu Municipal Medical Center, Kitakyusyu); Eriko Tokunaga (Kyushu University, Fukuoka); Shinji Ohno (National Kyushu Cancer Center, Fukuoka); Maki Tanaka (Social Insurance Kurume Daiichi Hospital, Kurume); Yutaka Yamamoto (Kumamoto University, Kumamoto); Hideya Tashiro (Oita Prefectural Hospital, Oita); Yoshiaki Rai (Hakuaikai Sagara Hospital, Kagoshima)

This study was funded by Kyowa Hakko Kirin Co., Ltd.

Conflict of interest

Regarding the work under consideration, YI received payment in relation to the role of the safety review committee. KT received payment in relation to the role of medical advisor. YT performed research and received research funding from Kyowa Hakko Kirin. TS performed research and received remuneration from Kyowa Hakko Kirin. RS is employed by and owns stock in Kyowa Hakko Kirin. YK, YR, NM, TT, and SN performed research and have declared that they have no disclosure and financial support.

Ethical standards

This clinical trial complies with the current laws in Japan. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

References

- 1.Blackwell S, Crawford J. Filgrastim (r-metHuG-CSF) in the chemotherapy setting. In: Morstyn G, Dexter TM, editors. Filgrastim (r-metHuG-CSF) in Clinical Practice. New York: Marcel Dekker, Inc.; 1994. pp. 103–116. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bosly A, Bron D, van Hoof A, de Bock R, Berneman Z, Ferrant A, Kaufman L, Dauwe M, Verhoef G. Achievement of optimal average relative dose intensity and correlation with survival in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma patients treated with CHOP. Ann Hematol. 2008;87:277–283. doi: 10.1007/s00277-007-0399-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lyman GH, Dale DC, Friedberg J, Crawford J, Fisher RI. Incidence and predictors of low chemotherapy dose-intensity in aggressive non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: a nationwide study. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:4302–4311. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.03.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith TJ, Khatcheressian J, Lyman GH, Ozer H, Armitage JO, Balducci L, Bennett CL, Cantor SB, Crawford J, Cross SJ, Demetri G, Desch CE, Pizzo PA, Schiffer CA, Schwartzberg L, Somerfield MR, Somlo G, Wade JC, Wade JL, Winn RJ, Wozniak AJ, Wolff AC. 2006 update of recommendations for the use of white blood cell growth factors: an evidence-based clinical practice guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3187–3205. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.4451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Comprehensive Cancer Network (2014) Clinical practice guidelines in oncology: myeloid growth factors, version 1. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/myeloid_growth.pdf. Accessed 6 June 2014 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Aapro MS, Bohlius J, Cameron DA, Dal Lago L, Donnelly JP, Kearney N, Lyman GH, Pettengell R, Tjan-Heijnen VC, Walewski J, Weber DC, Zielinski C, European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer 2010 update of EORTC guidelines for the use of granulocyte-colony stimulating factor to reduce the incidence of chemotherapy-induced febrile neutropenia in adult patients with lymphoproliferative disorders and solid tumours. Eur J Cancer. 2011;47:8–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2010.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Japan Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline [homepage on the Internet]. Japan Society of Clinical Oncology. G-CSF supportive treatment. http://www.jsco-cpg.jp/item/30/index.html. Accessed 6 June 2014

- 8.Vogel CL, Wojtukiewicz MZ, Carroll RR, Tjulandin SA, Barajas-Figueroa LJ, Wiens BL, Neumann TA, Schwartzberg LS. First and subsequent cycle use of pegfilgrastim prevents febrile neutropenia in patients with breast cancer: a multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III study. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:1178–1184. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.09.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Masuda N, Nakamura S, Ito Y, Tokuda Y, Tamura K. A multicenter randomized phase II study of KRN125 (pegfilgrastim) to determine the optimal dosage in Japanese breast cancer patients receiving TAC treatment. Eur J Cancer. 2011;47:S380. doi: 10.1016/S0959-8049(11)71609-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jones SE, Savin MA, Holmes FA, O’Shaughnessy JA, Blum JL, Vukelja S, McIntyre KJ, Pippen JE, Bordelon JH, Kirby R, Sandbach J, Hyman WJ, Khandelwal P, Negron AG, Richards DA, Anthony SP, Mennel RG, Boehm KA, Meyer WG, Asmar L. Phase III trial comparing doxorubicin plus cyclophosphamide with docetaxel plus cyclophosphamide as adjuvant therapy for operable breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:5381–5387. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.5391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Soong D, Haj R, Leung MG, Myers R, Higgins B, Myers J, Rajagopal S. High rate of febrile neutropenia in patients with operable breast cancer receiving docetaxel and cyclophosphamide. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:e101–e102. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.0508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vandenberg T, Younus J, Al-Khayyat S. Febrile neutropenia rates with adjuvant docetaxel and cyclophosphamide chemotherapy in early breast cancer: discrepancy between published reports and community practice—a retrospective analysis. Curr Oncol. 2010;17:2–3. doi: 10.3747/co.v17i2.498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Takabatake D, Taira N, Hara F, Sien T, Kiyoto S, Takashima S, Aogi K, Ohsumi S, Doihara H, Takashima S. Feasibility study of docetaxel with cyclophosphamide as adjuvant chemotherapy for Japanese breast cancer patients. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2009;39:478–483. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyp050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kawabata H, Iwatani T, Makuuchi R, Miura D, Suzuki N, Nakazawa H. Safety and tolerability of docetaxel with cyclophosphamide for early breast cancer. Gan To Kagaku Ryoho. 2010;37:835–839. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Trent JC, Valero V, Booser DJ, Esparza-Guerra LT, Ibrahim N, Rahman Z, Vernillet L, Patel S, David CL, Murray JL, Cristofanilli M, Hortobagyi GN. A phase I study of docetaxel plus cyclophosphamide in solid tumors followed by a phase II study as first-line therapy in metastatic breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:2426–2434. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chan A, Fu WH, Shih V, Coyuco JC, Tan SH, Ng R. Impact of colony-stimulating factors to reduce febrile neutropenic events in breast cancer patients receiving docetaxel plus cyclophosphamide chemotherapy. Support Care Cancer. 2011;19:497–504. doi: 10.1007/s00520-010-0843-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martín M, Lluch A, Seguí MA, Ruiz A, Ramos M, Adrover E, Rodríguez-Lescure A, Grosse R, Calvo L, Fernandez-Chacón C, Roset M, Antón A, Isla D, del Prado PM, Iglesias L, Zaluski J, Arcusa A, López-Vega JM, Muñoz M, Mel JR. Toxicity and health-related quality of life in breast cancer patients receiving adjuvant docetaxel, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide (TAC) or 5-fluorouracil, doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide (FAC): impact of adding primary prophylactic granulocyte-colony stimulating factor to the TAC regimen. Ann Oncol. 2006;17:1205–1212. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Younis T, Rayson D, Thompson K. Primary G-CSF prophylaxis for adjuvant TC or FEC-D chemotherapy outside of clinical trial settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Support Care Cancer. 2012;20:2523–2530. doi: 10.1007/s00520-011-1375-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Masaoka T. Evidence-based recommendations for antimicrobial use in febrile neutropenia in Japan: executive summary. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39:S49–S52. doi: 10.1086/383054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gandara DR, Kawaguchi T, Crowley J, Moon J, Furuse K, Kawahara M, Teramukai S, Ohe Y, Kubota K, Williamson SK, Gautschi O, Lenz HJ, McLeod HL, Lara PN, Jr, Coltman CA, Jr, Fukuoka M, Saijo N, Fukushima M, Mack PC. Japanese-US common-arm analysis of paclitaxel plus carboplatin in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a model for assessing population-related pharmacogenomics. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3540–3546. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.8793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Han HS, Reis IM, Zhao W, Kuroi K, Toi M, Suzuki E, Syme R, Chow L, Yip AY, Glück S. Racial differences in acute toxicities of neoadjuvant or adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with early-stage breast cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2011;47:2537–2545. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2011.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(PDF 16 kb)

(PDF 17 kb)