Abstract

Currently immunosuppressive and biological agents are used in a more extensive and earlier way in patients with inflammatory bowel disease, rheumatic or dermatologic diseases. Although these drugs have shown a significant clinical benefit, the safety of these treatments is a challenge. Hepatitis B virus (HBV) reactivations have been reported widely, even including liver failure and death, and it represents a deep concern in these patients. Current guidelines recommend to pre-emptive therapy in patients with immunosuppressants in general, but preventive measures focused in patients with corticosteroids and inflammatory diseases are scarce. Screening for HBV infection should be done at diagnosis. The patients who test positive for hepatitis B surface antigen, but do not meet criteria for antiviral treatment must receive prophylaxis before undergoing immunosuppression, including corticosteroids at higher doses than prednisone 20 mg/d during more than two weeks. Tenofovir and entecavir are preferred than lamivudine because of their better resistance profile in long-term immunosuppressant treatments. There is not a strong evidence, to make a general recommendation on the necessity of prophylaxis therapy in patients with inflammatory diseases that are taking low doses of corticosteroids in short term basis or low systemic bioavailability corticosteroids such as budesonide or beclomethasone dipropionate. In these cases regularly HBV DNA monitoring is recommended, starting early antiviral therapy if DNA levels begin to rise. In patients with occult or resolved hepatitis the risk of reactivation is much lower, and excepting for Rituximab treatment, the prophylaxis is not necessary.

Keywords: Hepatitis B virus, Inflammatory bowel disease, Rheumatic disease. Dermatologic diseases, Corticosteroids, Anti-tumor necrosis factor, Prophylaxis, Immunosuppressants

Core tip: Few reviews have been published including data of the three more common inflammatory diseases that require immunosuppressive therapy: inflammatory bowel disease, rheumatic and dermatologic diseases. This paper is focused on the risk of reactivation of hepatitis B virus under immunosuppressants, and particularly corticosteroids. Although most of the guidelines do not specify the necessity of prophylaxis in case of monotherapy with corticosteroids, the specialists responsible of these patients are usually concerned about this issue. Moreover, the risk with low systemic bioavailability new corticosteroids has not been evaluated in previous reviews. This work summarizes the evidence of VHB reactivation in patients with inflammatory diseases: when and how to apply prophylaxis, with a special focus on “new” and “old” steroids.

INTRODUCTION

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) is a preventable viral infection, but it is estimated that 2 billion persons worldwide are infected, and a significant number of case reports and clinical studies have pointed the risk of reactivation of this infection in patients on immunosuppressive therapies[1,2] Immunosuppressive and biological treatments are use more and sooner, during long periods of time in patients with inflammatory diseases (ID), including inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), rheumatic or dermatologic diseases. Therefore, the safety of these treatments is a deep concern among gastroenterologist, rheumatologist, and dermatologist

PREVALENCE OF HBV INFECTION IN PATIENTS WITH INFLAMMATORY DISEASES

The prevalence of the hepatitis B infection varies significantly worldwidely, from 1%-2% in the Western countries, to more than 8% in Asia and Africa[3-5].

Among patients with inflammatory diseases, those with IBD are assumed to have a higher risk of HBV infection because of the potential nosocomial transmission[6]. Biancone et al[7] found that IBD population had higher prevalence of hepatitis B surface antibody (HBsAb) than controls[7], and studies conducted in endemic areas have reported a rate of present and past HBV infection of 40%[8]. Conversely, recent researches in Spain and France describe exposure rates similar to the general population[9,10], while Kim et al[11], in South Korea, cannot find IBD as a risk factor for HBV, with a reported prevalence of hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) of 3.7% in IBD vs 4.4% in the control group[11].

In rheumatic diseases, the HBV status has also been evaluated. Irish investigators identified in a cohort of 200 rheumatoid arthritis (RA) patients only 4 cases with positive hepatitis B core antibody (HBcAb) and 11 with positive HBsAb, with no cases of positive HBsAg[12]. The prevalence of concurrent chronic hepatitis B infection in a cohort of RA patients in China was 11.2%, consistent with the prevalence in the general population[13], although the reported rate of HBsAg in ankylosing spondylitis (AS) by Zheng et al[14] was 25.4%, higher than in the general population or patients with other spondyloarthropathies and RA. In Japan, where approximately 20% Japanese individuals are infected with HBV, HBsAg and HBcAb positive occurred in 0.7% and 25.6% of patients with RA[15].

There are very few studies to determinate the prevalence of HBV infection in psoriasis and no significant differences between these patients and general population have been found[16].

Therefore, we cannot say that ID patients are a great risk population for HBV infection, at least according to the more recent research. The Table 1 summarizes some of the more relevant studies that have evaluated the prevalence of HBV in patients with inflammatory diseases.

Table 1.

Studies evaluating the prevalence of hepatitis B virus infection in patients with inflammatory diseases

| Ref. | Disease | Country | Publication year | Number patients | HBcAb | HBsAg |

| Biancone et al[7] | IBD | Italy | 2001 | 494 | UC 11.5% CD 11% | UC 0.64% CD 2.1% |

| Loras et al[9] | IBD | Spain | 2009 | 2056 | UC 8% CD 7.1% | UC 0.8% CD 0.6% |

| Chevaux et al[10] | IBD | France | 2010 | 315 | UC 1.6% CD 2.8% | UC 1.59% CD 0.79% |

| Huang et al[3] | IBD | China | 2014 | 714 | UC 41.6% CD 39.8% | UC 5.7% CD 5.3% |

| Kim et al[11] | IBD | South Korea | 2014 | 513 | UC 4.1% CD 3.3% | |

| Zou et al[13] | RA | China | 2013 | 223 | 11.2% | |

| Watanabe et al[15] | RA | Japan | 2014 | 7650 | 25.6% | 0.7% |

| Conway et al[12] | RA | Ireland | 2014 | 200 | 2% | 0% |

| Zheng et al[14] | AS | China | 2011 | 439 | 25.4% | |

| Cohen et al[16] | Psoriasis | Israel | 2010 | 12502 | 0.74% |

IBD: Inflammatory bowel disease; HBcAb: Hepatitis B core antibody; HBsAg: Hepatitis B surface antigen; RA: Rheumatoid arthritis; AS: Ankylosing spondylitis.

DEFINITIONS OF HEPATITIS B INFECTION AND REACTIVATION

The exposure to HBV can be divided broadly by the viral load and the liver biopsy into three categories: (1) active chronic HBV, characterized by an elevated serum alanine transaminase (ALT) (usually more than twice the upper limit of normal) and DNA levels above 2000 IU/mL; (2) inactive hepatitis B carrier, defined by low HBV DNA levels, typically < 2000 IU/mL, and normal ALT. There is not a significant necroinflammatory activity on the liver biopsy; and (3) resolved HBV infection. These patients are characterized by negative HBsAg and positive HBsAb. Patients with occult HBV infection (OBI) test positive only for HBcAb[17].

HBV reactivation is the reappearance of active necroinflammatory disease, marked by a 1.5-2-fold increase in ALT levels and DNA viral load > 2000 IU/mL in an inactive hepatitis B carrier, or a positivization from a previously undetectable DNA in an individual with a resolved hepatitis B[18,19].

EFFECT OF IMMUNOSUPPRESSIVE THERAPY ON HBV INFECTION

The HBV-induced liver inflammation is predominantly immune mediated: the host immune response causes a hepatocellular damage following the HBV replication, which can result in an acute or chronic liver necroinflammation.

Immunosuppressants lead to an increase in DNA viral due to both a effect on the host immune response, as to a stimulatory effect of these drugs on hepatitis B virus[20]. The corticosteroids may increase the expression of HBV through a glucocorticoid-responsive element, which has been detected in viral genoma, and stimulates viral replication in patients under these treatments[21].

On the other hand, tumoral necrosis factor (TNF) α and interferon gamma (IFNγ) are important in the clearance of HBV from infected hepatocytes, so the use of anti-TNF drugs in patients with chronic HBV infections may result in an increase in viral replication[22,23].

Despite the increase in viral replication, the major damage hardly ever appears at the time of maximal immunosuppression and usually occurs once the immunosuppressive therapy is withdrawn, during the phase of immune reconstitution, when the immune system is able to destroy the hepatitis B-infected hepatocytes, producing the liver disease[5,24]. Clinically these exacerbations can vary, ranging from a subclinical or asymptomatic course to a severe acute hepatitis and even death[25].

HBV REACTIVATIONS IN PATIENTS WITH INFLAMMATORY DISEASES

In ID patients the risk of hepatitis B reactivation is highest with the use of monoclonal antibodies anti-CD20 (rituximab)[26], but it may also be fatal in inactive hepatitis B carriers patients undergoing other immunosuppressant treatments[27]. Cases of HBV reactivation have been reported in RA patients treated with methotrexate (MTX) generally at doses lower than 10 mg/wk[28], and anti-TNF agents, specially with IFX, but also with adalimumab and etanercept[29-31].

Oshima et al[32] measured the risk of hepatitis B with anti rheumatic drugs and found a significant association between them and the occurrence of hepatitis exacerbation {corticosteroids [OR = 2.3 (1.3-4)], MTX: [4.9 (3.9-6.0)] and rituximab: [7.2 (5.3-9.9)]}[32]. Lee et al[33] and Nakamura et al[34] reported an incidence of viral reactivations of 5.3% and 12% in the patients under immunosuppressive treatment and inactive viral infection[33,34].

Regarding IBD, reported cases of reactivation of HBV with IFX have been extensively reviewed elsewhere[35-38]. Most of them have occurred in patients with co-treatment with immunomodulators such as azathioprine or MTX. The Spanish REPENTINA study showed that no single drug was specifically involved, and the risk seems to be associated with the intensity of immunosuppression[39,40].

Case reports of HBV exacerbation in severe psoriasis patients have also been published[41]. In a recent review in patients with rheumatic, digestive, and dermatologic autoimmune diseases, treated with any of the anti-TNF inhibitors, by Pérez-Alvarez et al[42] HBV reactivation was observed in 39% of hepatitis B carriers in hepatitis B carriers. Reactivations were more frequent in patients previously treated with other immunosuppressive agents (96% vs 70%, P = 0.033) and less in those who received antiviral prophylaxis (23% vs 62%, P = 0.003).

Although anti-TNFs are the most common biological therapy in patients with ID, human IgG1κ monoclonal antibody of interleukin-12/23 (ustekinumab) has become an emerging therapy, especially in chronic psoriasis, but also in IBD. There are scarce data about the safety of ustekinumab and the relationship between IL-12 or IL-23 and HBV, but some cases of reactivations have been described[2,43,44].

Regarding patients with resolved HBV or OBI, the risk is much lower. Reactivations following chemotherapy or potent immunosuppressive drugs such as Rituximab have been reported specially on the onco-haematological field[13,45], and although some cases have also been published with anti-TNF therapy, the rate is not relevant[46]. Tamori et al[47] described the reactivation risk in 50 patients, with positive results for hepatitis B core antibody, treated with immunosuppresants for rheumatic diseases: the reactivation was 10 times more likely in those with HBsAg positive than in the HBsAg negative grupo (20% vs 2%)[47].

Finally, Cassano et al[48] analyzed 62 psoriatic patients with occult viral infection, treated with anti-TNFs agents. There were no signs of HBV activation after a period of 4 years, which supports the safety of the use of immunosuppressant drugs (others than rituximab) in this scenario[48].

CORTICOSTEROIDS AND IMMUNOSUPPRESSION

The risk of infections with corticosteroids are proved to be increased with the dose[49]. Although it is not clearly defined, a dose equivalent to either 2 mg/kg of body weight or a total of 20 mg/d of prednisone are accepted to suppress significatively the immune system in treatments longer than two weeks[50-52].

The Consortium of Rheumatology Researchers of North America evaluated the risk for all infectious events, which were increased with prednisone 10 mg/d (incidence rate ratio relative:1.30; 95%CI: 1.11-1.53) whilst any dose increased the risk of opportunistic infections[53].

Concerning IBD population, there are no precise data on the dose of corticosteroids associated with the increased risk, but Rahier et al[25] in the Second European evidence-based Consensus on the prevention, diagnosis and management of opportunistic infections in inflammatory bowel disease, indicate that doses greater than 20 mg/d of prednisolone in adults are immunusuppressive and increase the percentage of events[25].

Beyond that, the combination of two or three of immunosuppressant drugs enhances the probability of infections[54,55].

Corticosteroids and HBV reactivation

First reactivation was described by Wands et al[56] in 1975, in 20 patients with lymphoproliferative and myeloproliferative disorders receiving chemotherapy.

Subsequently, other cases were communicated in rheumatic and autoimmune diseases: Nakanishi et al[57] and Cheng et al[58] reported HBV reactivations after high dose of steroids in monotherapy. None of the cases had received prophylaxis for HBV, and developed clinical disease in 4, 5 and 9 mo after the beginning of the treatment. Zanati et al[59] and Bae et al[60] have also described two fatal cases of HBV reactivations in patients with connective tissue diseases treated with steroids and chloroquine.

Another prospective study, carried in 41 Chinese adults with idiopatic nephrotic syndrome and inactive hepatitis B, compared standard doses of prednisone vs lower doses of prednisone plus mycophenolate mofetil (MMF)[61]. Without pre-emptive therapy, the risk of exacerbation was lower in MMF-prednisone regimen than the group with prednisone in monotherapy, reflecting the major effect of higher doses on the viral reactivation.

Yang et al[62] identified in a retrospective study, four cases of viral hepatitis flares in HBV carriers, who received at least 6 mo of high doses of systemic corticosteroid for connective tissue diseases[62], and resulted in a mortality of fifty percent.

Finally, Xuan et al[63] have reviewed 30 cases of reactivation after steroids, in monotherapy or combined with other therapies, in 144 patients with rheumatic diseases. The mean time to reactivations was 9.8 mo. Although the findings indicate that the risk of hepatitis reactivation mostly relies on the prednisone doses, as some cases of HBV reactivation have occurred with low-dose-prednisone therapies, caution is advisable[60].

In IBD there have also been reports of reactivation in patients under corticosteroids, with or without azathioprine or anti-TNF therapy, even resulting in severe acute hepatitis[6,64,65]. The Spanish REPENTINA study describes 6 cases of HBV reactivation in IBD patients during conventional immunosuppressive therapy, two of them with prednisone in monotherapy. Fifty percent of the cases resulted in liver failure and one of them required a liver transplantation[39]. The Table 2 reflects the cases of HBV reactivation with steroid therapy.

Table 2.

Hepatitis B virus reactivations in patients treated with steroids

| Ref. | Disease | Study | Patients (n) | HBV status (n) | Pre-emptive therapy | HBV reactivations (n) |

| Cheng et al[58] | Autoimmune diseases | Case report | 2 | CHB (1) RS (1) | No | 2 |

| Nakanishi et al[57] | Polymyositis | Case report | 1 | CHB | No | 1 |

| Zanati et al[59] | Mixed connective tissue disease | Case report | 1 | CHB | No | 1 |

| Bae et al[60] | Rheumatoid arthritis | Case report | 1 | CHB | No | 1 |

| Li et al[61] | Idiopathic nephrotic syndrome | Prospective | 41 | CHB (41) | No | 21 |

| Yang et al[62] | Connective tissue disease | Retrospective | 98 | CHB (21) Not applied (77) | No | 4 |

| Loras et al[39] | IBD | Retrospective | 25 | CHB | No | 6 |

Adapted from Xuan et al[63]. CHB: Chronic hepatitis B, inactive carriers included; RS: Resolved infection; HBV: Hepatitis B virus.

Reactivation of HBV and “new” corticosteroids

The topically acting oral steroids are agents characterized by a low systemic bioavailability due to an important first-pass liver metabolism. So, the typical adverse effects of steroids are partially avoided because of a lower concentration of the drug in plasma[66]. The most representative are beclometasone dipropionate (BDP) and budesonide. Many studies have reported their efficacy compared to placebo, conventional steroids and 5-ASA[67-70]. Nunes et al[71] reported the Spanish experience of oral BDP in a retrospective and multicenter study that included more than four hundred patients with active UC. Mild secondary effects were described in 7.6% of the cases, but no serious events either cases of HBV reactivations were identified.

Lichtenstein et al[72] reviewed five trials evaluating budesonide for up to 1 year for mild-to-moderate CD compared to placebo. Budesonide 6 mg/d was found to be significantly associated with mild infections (P = 0.023), but clinically important events were rare, and no HBV reactivations were observed.

PROPHYLAXIS AGAINST HEPATITIS B REACTIVATION

The aim of the diverse guidelines is to provide clear recommendations for clinical practice. Before 2005 there were no recommendations for HVB and HCV screening in IBD or rheumatic patients requiring immunosuppression[73]. The appropriate time to do hepatitis B serologic tests is at diagnosis, better than the moment of considering immunosuppression[74-77]. The tests must include HBsAb, HBsAg, and HBcAb, in order to detect also OBI, and HBV vaccination or HBV-DNA quantification must be done depending on the results[25].

Patients with active chronic HBV should receive the antiviral treatment applicable to immunocompetent patients, but this is not the goal of this review.

Prophylaxis in hepatitis B resolved infection

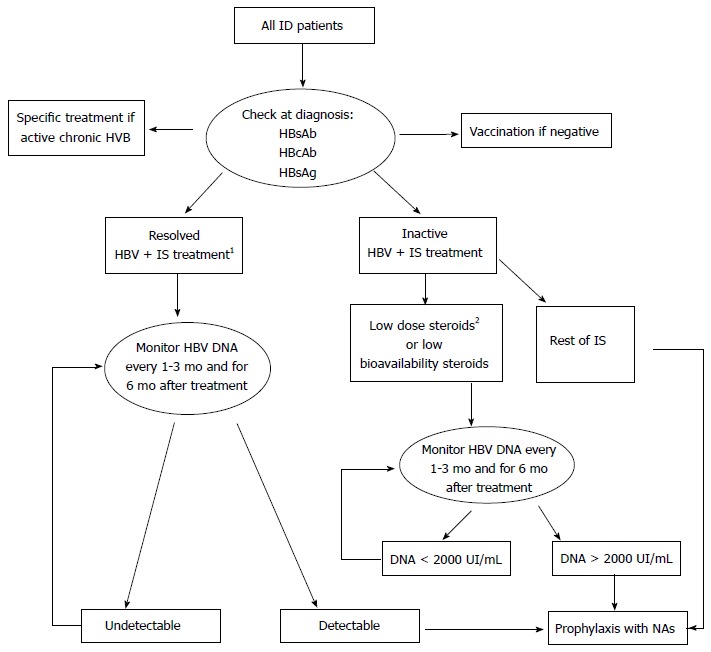

Excepting rituximab, there is no evidence for systematic anti-viral prophylaxis in resolved or OBI in patients on immunosuppresants, taking into account that the HBV reactivation occurs rarely[78]. These patients must be followed closely during therapy (every 1-3 mo, and for 6 mo after stopping treatment), and considered for prophylactic therapy according to DNA levels[5] (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Algorithm suggested for the management of patients with inflammatory diseases and hepatitis B virus infection. 1Except Rituximab, in which antiviral prophylaxis is desirable; 2Low dose steroids ≤ 20 mg/d prednisone. Adapted from Lopez-Serrano et al[17]. ID: Inflammatory diseases; IS: Immunosuppressants (steroids, thiopurines, methotrexate and biologics); NAs: Nucleoside/nucleotide analogues; HBcAb: Hepatitis B core antibody; HBsAg: Hepatitis B surface antigen; Low biodisponibility steroids: Budesonide or beclometasone dipropionate; HBV: Hepatitis B virus.

Prophylaxis in inactive hepatitis B carriers

The American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the European Association for the Study of the Liver recommend the early introduction of pre-emptive therapy in those HBsAg carriers which are going to start immunosuppressive therapy, including immunomodulators, biologic therapy and corticosteroids[74,75]. As we have commented previously, a dose of prednisone higher than 20 mg/d appears to be sufficiently immunosuppressive, in treatments longer than two weeks, so that prophylaxis must be considered. It must be introduced 1-3 wk before therapy and continue for 6 mo to 1 year after withdrawal [77,79,80].

Apart from cases reviews, there is no strong evidence to make this recommendation in patients with ID and low doses of corticosteroids in short term basis. More conservative management advises to monitor regularly HBV DNA and to start early antiviral therapy if DNA level arises[6,81,82]. The same recommendations can be made in the case of the low systemic bioavailability steroids (budesonide and BPD).

Which antiviral drug must we choose?

Lamivudine has been the most frequent agent used agent in this scenario, having proved to reduce the reactivation risk and the associated mortality and morbidity. However, Lamivudine resistance develops in 53%-76% of patients after 3 years of treatment, therefore, this agent is only appropriate when a short course of therapy is needed. As immunosuppressants for ID usually are used for long term, nucleoside/nucleotide analogues (NAs) with a lower rate of resistance must be considered. Tenofovir and entecavir have a higher barrier to resistance, and should be used if treatments longer than 12 mo are planned[6,76,77,82,83].

In those patients with OBI with a high risk of reactivation, lamivudine may still have a role, because of its low cost, and the low or absent HBV viremia in these cases[76,78]. Alternative antiviral medications for lamivudine would be adefovir and telbivudine[20]. In all cases, but more closely if lamivudine, adefovir or telbivudine are used, serum AST/ALT levels and hepatitis B viral load must be monitored every 3 or 6 mo.

In conclusion, HBV reactivations are not uncommon in inactive HBV patients treated with immunosuppressive therapy for inflammatory diseases. Current guidelines highly recommend prophylaxis in case of immunosuppressive therapy, including patients receiving steroids in monotherapy. However, steroids at low doses, treatments shorter than two weeks and low biodisponibility steroids are unlikely to need prophylaxis, although studies are lacking in this setting. These patients and those with occult or resolved HBV precise regularly HBV DNA monitoring during immunosuppressant therapy in order to detect reactivations. Entecavir or tenofovir are recommended as the optimal agents against HBV reactivation.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest: Dr. Conrado Fernández Rodríguez is a advisory board member, panel reviewer and consultant for Bristol Myers Squibb. The rest of the authors whose names are listed certify that they have NO affiliations or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial interest, or non-financial interest in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript.

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Peer-review started: August 30, 2014

First decision: November 14, 2014

Article in press: January 9, 2015

P- Reviewer: Khattab MA, Li YY, Vespasiani-Gentilucci U S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu HL

References

- 1.Shouval D, Shibolet O. Immunosuppression and HBV reactivation. Semin Liver Dis. 2013;33:167–177. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1345722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Koskinas J, Tampaki M, Doumba PP, Rallis E. Hepatitis B virus reactivation during therapy with ustekinumab for psoriasis in a hepatitis B surface-antigen-negative anti-HBs-positive patient. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168:679–680. doi: 10.1111/bjd.12120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huang ML, Xu XT, Shen J, Qiao YQ, Dai ZH, Ran ZH. Prevalence and factors related to hepatitis B and C infection in inflammatory bowel disease patients in China: a retrospective study. J Crohns Colitis. 2014;8:282–287. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2013.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stroffolini T, Guadagnino V, Chionne P, Procopio B, Mazzuca EG, Quintieri F, Scerbo P, Giancotti A, Nisticò S, Focà A, et al. A population based survey of hepatitis B virus infection in a southern Italian town. Ital J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1997;29:415–418. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sansone S, Guarino M, Castiglione F, Rispo A, Auriemma F, Loperto I, Rea M, Caporaso N, Morisco F. Hepatitis B and C virus reactivation in immunosuppressed patients with inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:3516–3524. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i13.3516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gisbert JP, Chaparro M, Esteve M. Review article: prevention and management of hepatitis B and C infection in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;33:619–633. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2010.04570.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Biancone L, Pavia M, Del Vecchio Blanco G, D’Incà R, Castiglione F, De Nigris F, Doldo P, Cosco F, Vavassori P, Bresci GP, et al. Hepatitis B and C virus infection in Crohn’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2001;7:287–294. doi: 10.1097/00054725-200111000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yim HJ, Lok AS. Natural history of chronic hepatitis B virus infection: what we knew in 1981 and what we know in 2005. Hepatology. 2006;43:S173–S181. doi: 10.1002/hep.20956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Loras C, Saro C, Gonzalez-Huix F, Mínguez M, Merino O, Gisbert JP, Barrio J, Bernal A, Gutiérrez A, Piqueras M, et al. Prevalence and factors related to hepatitis B and C in inflammatory bowel disease patients in Spain: a nationwide, multicenter study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:57–63. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2008.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chevaux JB, Nani A, Oussalah A, Venard V, Bensenane M, Belle A, Gueant JL, Bigard MA, Bronowicki JP, Peyrin-Biroulet L. Prevalence of hepatitis B and C and risk factors for nonvaccination in inflammatory bowel disease patients in Northeast France. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2010;16:916–924. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim ES, Cho KB, Park KS, Jang BI, Kim KO, Jeon SW, Kim EY, Yang CH, Kim WJ. Prevalence of hepatitis-B viral markers in patients with inflammatory bowel disease in a hepatitis-B-endemic area: inadequate protective antibody levels in young patients. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2014;48:553–558. doi: 10.1097/01.mcg.0000436435.75392.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Conway R, Doran MF, O’Shea FD, Crowley B, Cunnane G. The impact of hepatitis screening on diagnosis and treatment in rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Rheumatol. 2014;33:1823–1827. doi: 10.1007/s10067-014-2612-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zou CJ, Zhu LJ, Li YH, Mo YQ, Zheng DH, Ma JD, Ou-Yang X, Pessler F, Dai L. The association between hepatitis B virus infection and disease activity, synovitis, or joint destruction in rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Rheumatol. 2013;32:787–795. doi: 10.1007/s10067-013-2170-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zheng B, Li T, Lin Q, Huang Z, Wang M, Deng W, Liao Z, Gu J. Prevalence of hepatitis B surface antigen in patients with ankylosing spondylitis and its association with HLA-B27: a retrospective study from south China. Rheumatol Int. 2012;32:2011–2016. doi: 10.1007/s00296-011-1934-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Watanabe R, Ishii T, Kobayashi H, Asahina I, Takemori H, Izumiyama T, Oguchi Y, Urata Y, Nishimaki T, Chiba K, et al. Prevalence of hepatitis B virus infection in patients with rheumatic diseases in Tohoku area: a retrospective multicenter survey. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2014;233:129–133. doi: 10.1620/tjem.233.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cohen AD, Weitzman D, Birkenfeld S, Dreiher J. Psoriasis associated with hepatitis C but not with hepatitis B. Dermatology. 2010;220:218–222. doi: 10.1159/000286131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.López-Serrano P, Pérez-Calle JL, Sánchez-Tembleque MD. Hepatitis B and inflammatory bowel disease: role of antiviral prophylaxis. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:1342–1348. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i9.1342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beaugerie L, Gerbes AL. Liver dysfunction in patients with IBD under immunosuppressive treatment: do we need to fear? Gut. 2010;59:1310–1311. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.217331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Manzano-Alonso ML, Castellano-Tortajada G. Reactivation of hepatitis B virus infection after cytotoxic chemotherapy or immunosuppressive therapy. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:1531–1537. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i12.1531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Calabrese LH, Zein NN, Vassilopoulos D. Hepatitis B virus (HBV) reactivation with immunosuppressive therapy in rheumatic diseases: assessment and preventive strategies. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:983–989. doi: 10.1136/ard.2005.043257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tur-Kaspa R, Shaul Y, Moore DD, Burk RD, Okret S, Poellinger L, Shafritz DA. The glucocorticoid receptor recognizes a specific nucleotide sequence in hepatitis B virus DNA causing increased activity of the HBV enhancer. Virology. 1988;167:630–633. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Herbein G, O’Brien WA. Tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha and TNF receptors in viral pathogenesis. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 2000;223:241–257. doi: 10.1177/153537020022300305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kasahara S, Ando K, Saito K, Sekikawa K, Ito H, Ishikawa T, Ohnishi H, Seishima M, Kakumu S, Moriwaki H. Lack of tumor necrosis factor alpha induces impaired proliferation of hepatitis B virus-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes. J Virol. 2003;77:2469–2476. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.4.2469-2476.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morisco F, Castiglione F, Rispo A, Stroffolini T, Vitale R, Sansone S, Granata R, Orlando A, Marmo R, Riegler G, et al. Hepatitis B virus infection and immunosuppressive therapy in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Liver Dis. 2011;43 Suppl 1:S40–S48. doi: 10.1016/S1590-8658(10)60691-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rahier JF, Magro F, Abreu C, Armuzzi A, Ben-Horin S, Chowers Y, Cottone M, de Ridder L, Doherty G, Ehehalt R, et al. Second European evidence-based consensus on the prevention, diagnosis and management of opportunistic infections in inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2014;8:443–468. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2013.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hanbali A, Khaled Y. Incidence of hepatitis B reactivation following Rituximab therapy. Am J Hematol. 2009;84:195. doi: 10.1002/ajh.21343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Flowers MA, Heathcote J, Wanless IR, Sherman M, Reynolds WJ, Cameron RG, Levy GA, Inman RD. Fulminant hepatitis as a consequence of reactivation of hepatitis B virus infection after discontinuation of low-dose methotrexate therapy. Ann Intern Med. 1990;112:381–382. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-112-5-381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wendling D, Auge B, Bettinger D, Lohse A, Le Huede G, Bresson-Hadni S, Toussirot E, Miguet JP, Herbein G, Di Martino V. Reactivation of a latent precore mutant hepatitis B virus related chronic hepatitis during infliximab treatment for severe spondyloarthropathy. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64:788–789. doi: 10.1136/ard.2004.031187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Calabrese LH, Zein N, Vassilopoulos D. Safety of antitumour necrosis factor (anti-TNF) therapy in patients with chronic viral infections: hepatitis C, hepatitis B, and HIV infection. Ann Rheum Dis. 2004;63 Suppl 2:ii18–ii24. doi: 10.1136/ard.2004.028209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Verhelst X, Orlent H, Colle I, Geerts A, De Vos M, Van Vlierberghe H. Subfulminant hepatitis B during treatment with adalimumab in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis and chronic hepatitis B. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;22:494–499. doi: 10.1097/meg.0b013e3283329d13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Michel M, Duvoux C, Hezode C, Cherqui D. Fulminant hepatitis after infliximab in a patient with hepatitis B virus treated for an adult onset still’s disease. J Rheumatol. 2003;30:1624–1625. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oshima Y, Tsukamoto H, Tojo A. Association of hepatitis B with antirheumatic drugs: a case-control study. Mod Rheumatol. 2013;23:694–704. doi: 10.1007/s10165-012-0709-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee YH, Bae SC, Song GG. Hepatitis B virus reactivation in HBsAg-positive patients with rheumatic diseases undergoing anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy or DMARDs. Int J Rheum Dis. 2013;16:527–531. doi: 10.1111/1756-185X.12154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nakamura J, Nagashima T, Nagatani K, Yoshio T, Iwamoto M, Minota S. Reactivation of hepatitis B virus in rheumatoid arthritis patients treated with biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs. Int J Rheum Dis. 2014:Apr 4; Epub ahead of print. doi: 10.1111/1756-185X.12359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Esteve M, Saro C, González-Huix F, Suarez F, Forné M, Viver JM. Chronic hepatitis B reactivation following infliximab therapy in Crohn’s disease patients: need for primary prophylaxis. Gut. 2004;53:1363–1365. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.040675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ojiro K, Naganuma M, Ebinuma H, Kunimoto H, Tada S, Ogata H, Iwao Y, Saito H, Hibi T. Reactivation of hepatitis B in a patient with Crohn’s disease treated using infliximab. J Gastroenterol. 2008;43:397–401. doi: 10.1007/s00535-008-2165-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.del Valle García-Sánchez M, Gómez-Camacho F, Poyato-González A, Iglesias-Flores EM, de Dios-Vega JF, Sancho-Zapatero R. Infliximab therapy in a patient with Crohn’s disease and chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2004;10:701–702. doi: 10.1097/00054725-200409000-00035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Esteve M, Loras C, González-Huix F. Lamivudine resistance and exacerbation of hepatitis B in infliximab-treated Crohn’s disease patient. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2007;13:1450–1451. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Loras C, Gisbert JP, Mínguez M, Merino O, Bujanda L, Saro C, Domenech E, Barrio J, Andreu M, Ordás I, et al. Liver dysfunction related to hepatitis B and C in patients with inflammatory bowel disease treated with immunosuppressive therapy. Gut. 2010;59:1340–1346. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.208413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Garcia-Vidal C, Rodríguez-Fernández S, Teijón S, Esteve M, Rodríguez-Carballeira M, Lacasa JM, Salvador G, Garau J. Risk factors for opportunistic infections in infliximab-treated patients: the importance of screening in prevention. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2009;28:331–337. doi: 10.1007/s10096-008-0628-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Conde-Taboada A, Muñoz JP, Muñoz LC, López-Bran E. Infliximab treatment for severe psoriasis in a patient with active hepatitis B virus infection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:1077–1080. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2008.09.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pérez-Alvarez R, Díaz-Lagares C, García-Hernández F, Lopez-Roses L, Brito-Zerón P, Pérez-de-Lis M, Retamozo S, Bové A, Bosch X, Sanchez-Tapias JM, et al. Hepatitis B virus (HBV) reactivation in patients receiving tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-targeted therapy: analysis of 257 cases. Medicine (Baltimore) 2011;90:359–371. doi: 10.1097/MD.0b013e3182380a76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Navarro R, Vilarrasa E, Herranz P, Puig L, Bordas X, Carrascosa JM, Taberner R, Ferrán M, García-Bustinduy M, Romero-Maté A, et al. Safety and effectiveness of ustekinumab and antitumour necrosis factor therapy in patients with psoriasis and chronic viral hepatitis B or C: a retrospective, multicentre study in a clinical setting. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168:609–616. doi: 10.1111/bjd.12045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Purnak S, Purnak T. Hepatitis B virus reactivation after ustekinumab treatment. Br J Dermatol. 2014;170:477–478. doi: 10.1111/bjd.12612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lledó JL, Fernández C, Gutiérrez ML, Ocaña S. Management of occult hepatitis B virus infection: an update for the clinician. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:1563–1568. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i12.1563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Matsumoto T, Marusawa H, Dogaki M, Suginoshita Y, Inokuma T. Adalimumab-induced lethal hepatitis B virus reactivation in an HBsAg-negative patient with clinically resolved hepatitis B virus infection. Liver Int. 2010;30:1241–1242. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2010.02238.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tamori A, Koike T, Goto H, Wakitani S, Tada M, Morikawa H, Enomoto M, Inaba M, Nakatani T, Hino M, et al. Prospective study of reactivation of hepatitis B virus in patients with rheumatoid arthritis who received immunosuppressive therapy: evaluation of both HBsAg-positive and HBsAg-negative cohorts. J Gastroenterol. 2011;46:556–564. doi: 10.1007/s00535-010-0367-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cassano N, Mastrandrea V, Principi M, Loconsole F, De Tullio N, Di Leo A, Vena GA. Anti-tumor necrosis factor treatment in occult hepatitis B virus infection: a retrospective analysis of 62 patients with psoriatic disease. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents. 2011;25:285–289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dixon WG, Kezouh A, Bernatsky S, Suissa S. The influence of systemic glucocorticoid therapy upon the risk of non-serious infection in older patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a nested case-control study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70:956–960. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.144741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Update on adult immunization. Recommendations of the Immunization Practices Advisory Committee (ACIP) MMWR Recomm Rep. 1991;40:1–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shepherd JE, Grabenstein JD. Immunizations for high-risk populations. J Am Pharm Assoc (Wash) 2001;41:839–849; quiz 923-925. doi: 10.1016/s1086-5802(16)31332-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Campos-Outcalt D. Immunization update: the latest ACIP recommendations. J Fam Pract. 2014;63:137–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Greenberg JD, Reed G, Kremer JM, Tindall E, Kavanaugh A, Zheng C, Bishai W, Hochberg MC. Association of methotrexate and tumour necrosis factor antagonists with risk of infectious outcomes including opportunistic infections in the CORRONA registry. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:380–386. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.089276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Aberra FN, Lewis JD, Hass D, Rombeau JL, Osborne B, Lichtenstein GR. Corticosteroids and immunomodulators: postoperative infectious complication risk in inflammatory bowel disease patients. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:320–327. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(03)00883-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Serradori T, Germain A, Scherrer ML, Ayav C, Perez M, Romain B, Palot JP, Rohr S, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Bresler L. The effect of immune therapy on surgical site infection following Crohn’s Disease resection. Br J Surg. 2013;100:1089–1093. doi: 10.1002/bjs.9152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wands JR, Chura CM, Roll FJ, Maddrey WC. Serial studies of hepatitis-associated antigen and antibody in patients receiving antitumor chemotherapy for myeloproliferative and lymphoproliferative disorders. Gastroenterology. 1975;68:105–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nakanishi K, Ishikawa M, Nakauchi M, Sakurai A, Doi K, Taniguchi Y. Antibody to hepatitis B e positive hepatitis induced by withdrawal of steroid therapy for polymyositis: response to interferon-alpha and cyclosporin A. Intern Med. 1998;37:519–522. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.37.519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cheng J, Li JB, Sun QL, Li X. Reactivation of hepatitis B virus after steroid treatment in rheumatic diseases. J Rheumatol. 2011;38:181–182. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.100692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zanati SA, Locarnini SA, Dowling JP, Angus PW, Dudley FJ, Roberts SK. Hepatic failure due to fibrosing cholestatic hepatitis in a patient with pre-surface mutant hepatitis B virus and mixed connective tissue disease treated with prednisolone and chloroquine. J Clin Virol. 2004;31:53–57. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2004.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bae JH, Sohn JH, Lee HS, Park HS, Hyun YS, Kim TY, Eun CS, Jeon YC, Han DS. A fatal case of hepatitis B virus (HBV) reactivation during long-term, very-low-dose steroid treatment in an inactive HBV carrier. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2012;18:225–228. doi: 10.3350/cmh.2012.18.2.225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Li X, Tian J, Wu J, He Q, Li H, Han F, Li Q, Chen Y, Ni Q, Chen J. A comparison of a standard-dose prednisone regimen and mycophenolate mofetil combined with a lower prednisone dose in Chinese adults with idiopathic nephrotic syndrome who were carriers of hepatitis B surface antigen: a prospective cohort study. Clin Ther. 2009;31:741–750. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2009.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yang CH, Wu TS, Chiu CT. Chronic hepatitis B reactivation: a word of caution regarding the use of systemic glucocorticosteroid therapy. Br J Dermatol. 2007;157:587–590. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2007.08058.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Xuan D, Yu Y, Shao L, Wang J, Zhang W, Zou H. Hepatitis reactivation in patients with rheumatic diseases after immunosuppressive therapy--a report of long-term follow-up of serial cases and literature review. Clin Rheumatol. 2014;33:577–586. doi: 10.1007/s10067-013-2450-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Colbert C, Chavarria A, Berkelhammer C. Fulminant hepatic failure in chronic hepatitis B on withdrawal of corticosteroids, azathioprine and infliximab for Crohn’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2007;13:1453–1454. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zeitz J, Mullhaupt B, Fruehauf H, Rogler G, Vavricka SR. Hepatic failure due to hepatitis B reactivation in a patient with ulcerative colitis treated with prednisone. Hepatology. 2009;50:653–654. doi: 10.1002/hep.23035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Harris DM. Some properties of beclomethasone dipropionate and related steroids in man. Postgrad Med J. 1975;51 Suppl 4:20–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Nos P, Hinojosa J, Gomollón F, Ponce J. Budesonide in inflammatory bowel disease: a meta-analysis. Med Clin (Barc) 2001;116:47–53. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7753(01)71716-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Seow CH, Benchimol EI, Griffiths AM, Otley AR, Steinhart AH. Budesonide for induction of remission in Crohn’s disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(3):CD000296. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000296.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gross V, Bunganic I, Belousova EA, Mikhailova TL, Kupcinskas L, Kiudelis G, Tulassay Z, Gabalec L, Dorofeyev AE, Derova J, et al. 3g mesalazine granules are superior to 9mg budesonide for achieving remission in active ulcerative colitis: a double-blind, double-dummy, randomised trial. J Crohns Colitis. 2011;5:129–138. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2010.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Papi C, Aratari A, Moretti A, Mangone M, Margagnoni G, Koch M, Capurso L. Oral beclomethasone dipropionate as an alternative to systemic steroids in mild to moderate ulcerative colitis not responding to aminosalicylates. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:2002–2007. doi: 10.1007/s10620-009-0962-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Nunes T, Barreiro-de Acosta M, Marin-Jiménez I, Nos P, Sans M. Oral locally active steroids in inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2013;7:183–191. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2012.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lichtenstein GR, Bengtsson B, Hapten-White L, Rutgeerts P. Oral budesonide for maintenance of remission of Crohn’s disease: a pooled safety analysis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;29:643–653. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03891.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Domènech E, Esteve M, Gomollón F, Hinojosa J, Panés J, Obrador A, Gassull MA. [GETECCU-2005 recommendations for the use of infliximab (Remicade) in inflammatory bowel disease] Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;28:126–134. doi: 10.1157/13072012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lok AS, McMahon BJ. Chronic hepatitis B: update 2009. Hepatology. 2009;50:661–662. doi: 10.1002/hep.23190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.European Association For The Study Of The Liver. EASL clinical practice guidelines: Management of chronic hepatitis B virus infection. J Hepatol. 2012;57:167–185. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Liaw Y, Kao J, Piratvisuth T, Yuen Chan H, Chien R, Liu C, Gane E, Locarnini S, Lim S, Han K, et al. Asian-Pacific consensus statement on the management of chronic hepatitis B: a 2012 update. Hepatol Int. 2012;6:531–561. doi: 10.1007/s12072-012-9365-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Buti M, García-Samaniego J, Prieto M, Rodríguez M, Sánchez-Tapias JM, Suárez E, Esteban R. [Consensus document of the Spanish Association for the Study of the Liver on the treatment of hepatitis B infection (2012)] Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;35:512–528. doi: 10.1016/j.gastrohep.2012.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sagnelli E, Pisaturo M, Martini S, Filippini P, Sagnelli C, Coppola N. Clinical impact of occult hepatitis B virus infection in immunosuppressed patients. World J Hepatol. 2014;6:384–393. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v6.i6.384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Mastroianni CM, Lichtner M, Citton R, Del Borgo C, Rago A, Martini H, Cimino G, Vullo V. Current trends in management of hepatitis B virus reactivation in the biologic therapy era. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:3881–3887. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i34.3881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hoofnagle JH, Doo E, Liang TJ, Fleischer R, Lok AS. Management of hepatitis B: summary of a clinical research workshop. Hepatology. 2007;45:1056–1075. doi: 10.1002/hep.21627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Toruner M, Loftus EV, Harmsen WS, Zinsmeister AR, Orenstein R, Sandborn WJ, Colombel JF, Egan LJ. Risk factors for opportunistic infections in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:929–936. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Vallet-Pichard A, Pol S. Hepatitis B virus treatment beyond the guidelines: special populations and consideration of treatment withdrawal. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2014;7:148–155. doi: 10.1177/1756283X14524614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Sacco R, Bertini M, Bresci G, Romano A, Altomare E, Capria A. Entecavir for hepatitis B virus flare treatment in patients with Crohn’s disease. Hepatogastroenterology. 2010;57:242–245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]