Abstract

Jaina religion has existed for thousands of years. Lord Mahavir was the last of the 24 Tirthankaras, 23 having preceded him. The principals of Jaina religion teach us: (1) Self-control, which includes: (a) Control over physiological instinct of hunger and sex; (b) control over desires; (c) control over emotions; (2) meditation; (3) introspection; (4) concentration; and (5) healthy interpersonal relationship. The principles of Jaina Religion can contribute to Positive Mental Health.

Keywords: Interpersonal Relationship, Jaina Religion, Meditation, Mohiniya Karma, Self-control, Tapa, Vratas

Introduction

Life is dear to all even though it may contain misery. Man's desire for an explanation of the existence of a misery, for relief from and extinction of misery and for a consequent increase of happiness of life, is the function of religion.

True religion is a way of life. It should lead to the mental and moral upliftment of an aspirant and must provide peace and happiness for his soul.

Jaina religion (Jainism) is an ancient one. Lord Mahavira, the 24th Tirthankara, rejuvenated it around 2500 years ago. However, it was propagated for thousands of years before Mahavira by the 23 Tirthankaras who preceded him. Even they were not the founders of Jainism, which had existed from time immemorial, they had brought the fundamental principles of Jainism to light by their extraordinary perception and knowledge. They preached, propounded and popularised its principles. Lord Mahavira, however, is credited with having formalised and rejuvenated the religion called Jainism.

Jaina Principles

Four infinities

The soul according to Jainism, consists of four infinities, that is, Infinite Knowledge (Ananta Gnana), Infinite Intuition (Anata Darsana), Infinite Happiness (Ananta Sukha) and Infinite Potency (Ananta Virya) (Bhadraprabhu, 1986).[3] These are the natural characteristics of the soul and come to full manifestation in the state of salvation. These powers of the soul are neutralised by Karmic influences in the state of spiritual bondage - the state of being engrossed in worldly affairs. The way to salvation consists of the efforts of the soul to remove the karmic obstruction and regain its natural state of four infinities lying dormant since the time immemorial.

Karman

The cause of obstruction is known as Karman. It is composed of a material substance known as Karma Varna (Galia, 2002).[5] The soul, disturbed by the activity of the mind, speech and/or body, attracts the dirt of that substance and is thereby petrified. The passions of anger, conceit, crookedness and greed, give durability and intensity to that dirt. The stronger the passions, the longer will dirt of the Karman last, and more strongly will it affect the soul. The accumulated Karman ends after producing its fruits, when its term is over. At the same time, fresh disturbances cause a new accumulation. This process has gone on from time immemorial. It will continue as long as the new accumulation is not stopped and until the old is not worked through or cast off through other measurers. The way to salvation demands a deliberate attempt of the soul to purify itself from the Karmic dirt by stopping the fresh accumulation and destroying the old.

Umasvati prescribes three virtues paving the way to salvation: right knowledge, right attitude and right conduct (Suriji, 1988, p30-1).[7] Knowledge in itself is neither right nor wrong. It is right when possessed by a person with right attitude and wrong in a person whose attitude is wrong. Thus, right attitude and right conduct play the main part. Both are connected with ‘Mohaniya Karman’. The ladder of salvation means, therefore, gradual liberation from the effects of ‘Mohaniya’.

Shrimad Rajchandra has said:

Karma Anant Prakarna, Tema Mukhya Aath

Tema Mukhya Mohiniya, Hanay Te Kahu Path

(There are infinite kinds of karmas. Eight are chief among them. Among these eight, Mohaniya deluding karma is the chief.) (Bhadraprabhu, 1986[2])

Karma Mohiniya Bhed Ve Darshan Charitra Naam

Hane Bodh, Vitragata, Achuk Upay Aam (Bhadraprabhu, 1986[2])

(There are two kinds of deluding Karma, namely, right belief deluding and right conduct deluding. The former is destroyed by knowledge of the soul and the latter by non-attachment.).

Darasna Mohaniya Karma makes a man extravagant, seeking happiness in external objects and identifying himself with the body and other material enteties. Charitra Mohaniya Karma has also the effects of the emotions of Anger (Krodha), Conceit (Mana), Crookedness (Maya) and Greed (Lobha) (Suriji, p30-1).[7] The aspirant has to ascend gradually by subduing these passions by degrees. This is minutely and well-described in the Jaina theory of 14 Gunasthanas (Bhadraprabhu, 1986).[3]

Shravakas and Vratas

Jainism has prescribed two different ways of practising religion, one by saints and monks (known as ‘shramanas’) who live separately in a holy place, and the other by laymen (known as ‘shravakas’) living with their families or as a householder. A shravaka is one who does his worldly duties and, in addition, follows the doctrine of Jainism. His primary goal is to do his duties as individual towards his family, towards his society, towards the State, etc. Secondarily, he also practises Jainism. A Shravaka follows 12 rules of conduct (vratas). He follows these 12 vratas to whatever extent possible, the goal being to follow them to the maximum extent without jeopardising his worldly duties.

The Sanskrit word for these 12 rules is ‘vrata’. It is derived from ‘vr’ which means to select or choose; so literally, the word ‘vrata’ means a kind of choice. The choice is a very strict matter, requiring the exercise of much care. This idea is peculiarly Jaina; there is no oath to a superior, or to a Deity; neither is it a decree or a command issued by a Deity to his subjects or creatures.

These 12 special rules or vows are divided into three classes; the first five vows are called ‘lesser’ vows, as compared with more strict vows of the monk. The next three vows (gunavrata) are of a kind that help or supports the first five. And the last four vows are disciplinary (siksavrata), their practice forms a sort of preparation for the monastic life. These vratas are:

Refraining from killing or destroying life (Sthula - Pranatipata - Viramana - Vrata).

Refraining from telling falsehood (sthula - Mrusavada - Viramana - Vrata).

Refraining from taking what is not give, that is, theft (Sthula - Adttadana - Virmana - vrata).

Avoidance of Sensual Pleasure (Sthula - Maithuna - viramana - Vrata).

Undertaking to limit one's possessions (Sthula - Parigrahaparimana - vrata).

Limitation of the area in which one will live including all direction of motion (Dig - Parimana - Vrata).

Limitation of the quantity of things one will use (Bhogopabhoga - Viramana - Vrata).

Undertaking not to incur unnecessary avoidable evils (Anarthadanda - Viramana - Vrata).

To sit in a certain holy place and read or meditate on holy subjects usually for 48 min (Samayika).

Reducing to a minimum the space in which one will move usually for a few days (Desavayasika - Vrata).

Same as ninth vow but continued for 12–24 hrs and accompanied by fasting (Pausadhopavasa).

Sharing and/or distributing essential things without any expectations or desires to Jaina monks or respectable Jaina layman (Atithisamvibhaga) (Suriji, 1988,[8] Bhadraprabhu, 1986).[4]

By following the above 12 vratas, the sharavaka would be able to minimise the inflow of new karmas. To wear out the accumulated effects of karma on the soul, the practice of austerities/Tapa has been advised. There are 12 types of austerities: Six physical or external and six internal.

The six physical austerities are:

Fasting (Upavas),

Eating less than one's capacity or hunger (Unodari),

Daily renunciation of one or more delicacies (Rastyag),

Reducing the desires (Vratisankshep),

Mortification of the body (Kayakalesh),

Concentration is a lonely or holy place (Sanalinata) (Bhadraprabhu, 1986).[1]

The six internal austerities are:

Expiation (Prayaschita),

Veneration (vinay),

Nursing and service to others (Vaiyavachcha),

Study of religious book (Sajajaya,)

Abandonment of bodily attachment (Vyutasarga),

Concentration (Dhyan) (Bhadraprabhu, 1986).[1]

Psychiatric Aspects

Individual

Self-control

Control over physiological instincts of sex and hunger: The fourth vrata of a Shravaka is avoidance of sensual pleasure including sensual pleasure with other man or woman; avoiding talking, reading and/or observing picture which excite an individual sexually; avoiding indulging in lustful conversation or stories; avoiding physical contact with person of opposite sex, etc. This weakness is many a time exploited as in the case of Vishwamitra by Menaka and the notoriety of Ms Pamela Bordes some time back. Control over desire for sensual pleasure will not allow the individual to get morally degraded.

The physical austerities of fasting, eating less and daily renunciation of one or more delicacies will bring about control over hunger and taste. During fasting, the Shravaka does not take any food for 36 h, that is, from sunset on day 1 to sunrise on day 3. During these 36 h, only boiled water is permitted for drinking. Some Shravakas even prefer avoiding water. Very rarely do these Shravakas suffer from dehydration, if at all. Some Shravakas do fasting for three consecutive days (Athama), some for eight consecutive days (Athai) or even for thirty consecutive days (Mas khamana). In Rastyag, Shravaka is expected to abandon or give up daily, voluntarily, certain food items. He usually decides about this in the morning and generally does not even inform anyone in the family. He may decide that today he will he not eat items prepared from milk or restrict his diet to 5 or any other number of items.

This self-control helps in building one's self-confidence, and it is one of the virtues of a mature personality. Even 8-10 years old children have been observed to follow fasting and Rastyag. This will help in developing a mature personality in these children. With fasting and eating less, the physical problems of obesity, and its complication would also be prevented.

Control over desires: The fifth vow of the Shravaka is undertaking to limit one's worldly possessions. One should prepare a list of everything one wants to possess. One should not go beyond this limit. Only in exceptional cases, one may enhance the limit. It is also expected that a Shravaka should scrutinise this list from time to time and go on curtailing it. Desires about money, property, ornaments etc., have to be curtailed. Limit has to be fixed according to reality. In present day life, one observes that desires and expectations are fast changing and increasing, even though the means to achieve these may not be available. Initially one has some desire, and when these are fulfilled (many times at much psychological cost), new desires and expectations crop up. The individual is never satisfied. There is no limit to such desires and expectations whereby the individual remain unhappy and anxious all the time. Larger the gap between expectations, desires and reality, greater the frustration. It is becoming the major reason for psychiatric morbidity. By voluntarily keeping desires within limits and remaining satisfied, one goes a long way towards psychological well-being.

Control over emotion: Anger (Krodha), Conceit (Mana), Crookedness (Maya) and Greed (Lobha) have been grouped in Jainism as Ksaya Saghna. Because of the effects of these emotions (part of Chaitra Mohaniya Karman), the soul is not able to achieve salvation or moksha. Therefore, the soul remains in this world (ksa = world, aya = increasing, that is, increasing worldly attachments.)

Psychologically, it is very well-known that one should control the above emotions. If not controlled, they produce effects on the body tilting the balance in favour of mental illness.

Dasha - Vaikalika Niryukti instructs as follows:

‘Subdue anger by forgiveness

Conquer vanity by humbleness

Overcome fraud with honesty

Vanquish greed through contentment.’ (Maharaj, 1999[6])

Meditation

Kausagga implies the idea of a particular bodily posture to be adopted in keeping oneself unmoved at a suitable spot (Sethia, 1985[10]) Samayika and Pratikamana means maintenance of balanced state of mind with regard to all blameworthy action, passions and hatred. The period is of consecutive 48 min to 1 h. During this period, all concentration is centred on religious activities, away from the world; this is similar to mediation. In the morning, chanting of the main sutra ‘Namo Arihamtanam etc.,’ for 108 times (requiring about 15 min) is also a form of meditation. Jaina temples are some of the cleanest temples. The atmosphere is one of tranquillity and serenity. Doing pooja and other morning rituals in such a serene atmosphere leads to meditation and mental peace.

All these are Jaina modes of dhyana practice. He, who practices these modes, is required to keep his body, mind and speech under perfect restraint. His mind is to be kept intent on the particular object of meditation (in religious discourses). Jainism lays stress on the practice of self-mortification as a means of checking one's passions as well as of inducing mental concentration. These practices of meditation were described and were actually being practiced by Shravakas centuries before Patanjali described yoga (Suriji, 1988).[9]

Introspection and concentration

In a lonely holy place, while sitting or standing, concentration is to be performed (Sanalinata). Furthermore, during this, virtues of the Tirthankaras and other saints are to be recited. By remembering and praising these virtues, a Shravaka remembers the Tirthankaras and is likely to follow them by identifying with their virtues.

Shravakas take a vow not to speak for few minutes, or a few hours or even a full day (Mauna Vrata). By this, again, one enhances self-control, and during this Mauna Vrata one also carries out introspection.

Interpersonal relationships

Society, according to Jainism, is a co-ordinated aggregate of autonomous units and depends for its own well-being upon that of every individual. No individual is subordinate to any other, and each being is entitled to independent expression. Jainism rejects the patronizing of one individual or class by another. The gradation of society into classes, therefore, is not in keeping with its spirit. Thus, all individuals are equal. This helps in keeping better interpersonal relationship among Shravakas.

Religion in Jainism is not blind faith. Nor is it emotional worship inspired by fear or wonder. It is intuitional realisation of the inherent purity of consciousness, will and the bliss of the self. In Jainism, the virtues are important and respected, not the individual. Even while worshiping the Tirthankaras and other saints, their virtues are recited. Ten virtues which are important are:

Forgiveness (uttama-ksama),

Humility (uttama-mardava),

Honesty and truthfulness (uttama-satya),

Purity (uttama-sauca),

Restrain (uttama-sanyama),

Austerities (uttama-tapa),

Renunciation (uttama-tyaga),

Selflessness (uttama-akinchanya), and

Chaste life (uttama-brahmacharya).

In reciting religious mantras, these virtues are recited again and again. From the interpersonal point of view, one who has virtues and knowledge should be respected, however small he may be. This respect and praise leads one to perform good and right conduct. One can compare this with learning theory wherein behaviour, which is rewarded, is maintained. The good and right behaviour from a person is appreciated in society, even though he may belong to a low socio-economic group.

Ahimsa or non-violence has to be practiced towards all human beings as also towards all living souls. Ahimsa is not only not killing, but also not inflicting pain or suffering, physical or psychological. In this manner, one recognises and respects others individuality, ideas, virtues and knowledge. This helps in the building up of positive interpersonal relationships. The second vrata, refraining from telling falsehood, and the third vrata, refraining from taking what is not given (theft), help in building trust and self-control. Trust so developed helps in building positive interpersonal relationships. Suspiciousness and paranoia are thus avoided.

By nursing and service to others, particularly those who are suffering (vaiavachcha), one recognises the sufferings of others. Psychologically, voluntary help without asking for anything in return, rendered to a person who suffers or who is in agony, builds up confidence. Empathy shown during this period, builds up a positive rapport. Religious books have quoted the Tirthankaras as saying:

Jo Gilanam Padivajjai So Maa Padivajjai

(‘One who serves diseased or suffering humanity, serves God’, Bhadraprabhu, 1986[2])

It is necessary for a Jaina to purify his heart of all passions at least once a year. That is why the Jains are so particular about observing the festival of ‘Pryushana’ which is an annual ritual of self-purification and introspection. Here, each individual begs pardon from every other by saying, ‘Knowingly or unknowingly, by mind, speech and body if I have hurt your feelings, please pardon me’ (Michacchami Dukkadam). By forgetting negative feelings and asking pardon, a new positive relationship is established with family members and other relatives. A true Jaina himself would ask for pardon without considering pride or prestige. Thus negative emotional feelings do not get accumulated and are worked through.

Furthermore, a true Jaina will confess his sins and mistakes committed to a Guru (Aloyana), thus getting rid of guilt feelings and improving psychological functioning. He himself decides his punishment by performing some form of austerities (Tapas). This helps in strengthening his ego so that he will not repeat the same sin or mistake. Accepting one's mistakes after introspection and observing self-punishment (Aloyana and Tapas) helps individuals in building ego strength.

Short Account

The above is a short account of the principles of Jainism in relation to Psychiatry. Its principles were laid down thousands of years ago, and the principles are still valid today. By putting these principles into practice voluntarily, the person himself is less likely to suffer from psychiatric illnesses. These principles also help in prevention and treatment of certain psychiatric illnesses like neurosis, personality disorders, addictions, etc. Indra Shastri has said in the article, Jainism and the way to spiritual realisation in the book ‘The Doctrines of Jainism’ (p 56):

Jainism is useful not only for salvation but also for a man who wishes to live a happy life by rising above his inner conflicts and complexes. It is regrettable that the supreme science of leading a happy life has been wrongly confined to transcendental purposes, on the assumption that benefits are not connected with the present life. That is a wrong notion. A man however materially rich he may be, will sooner or later have to learn this science if he seeks real happiness and wants to save himself from destruction.(Maharaj, 1999[6])

I will end my discussion by quoting from two sources. One is from ‘Utteradhyayana Sutra’ of Jainism. The first one is:

If one is always humble, free from curiosity and deceit; if he abuses nought; if he holds not to his wrath, if he listens to friendly advise; if he is not proud of his learning; if he finds no faults with any or nought; if he is patient with friends; if he speaks well even of the bad friend when he is absent; if he abstains from quarrels; if he is polite, gracious, calm and endeavours to gain enlightenment - then he is named the well-behaved (Sethia, 1985).[11]

The second one is:

Khamemi Sarve Jiva, Sarve Jiva Khamantu Me

Mitti Me Savva Bhuesu, Veram Majjam Nakenai

I forgive all souls: Let all souls forgive me. I am on friendly terms with all: I have no enmity with anybody. (Sethia, 1985[12]).

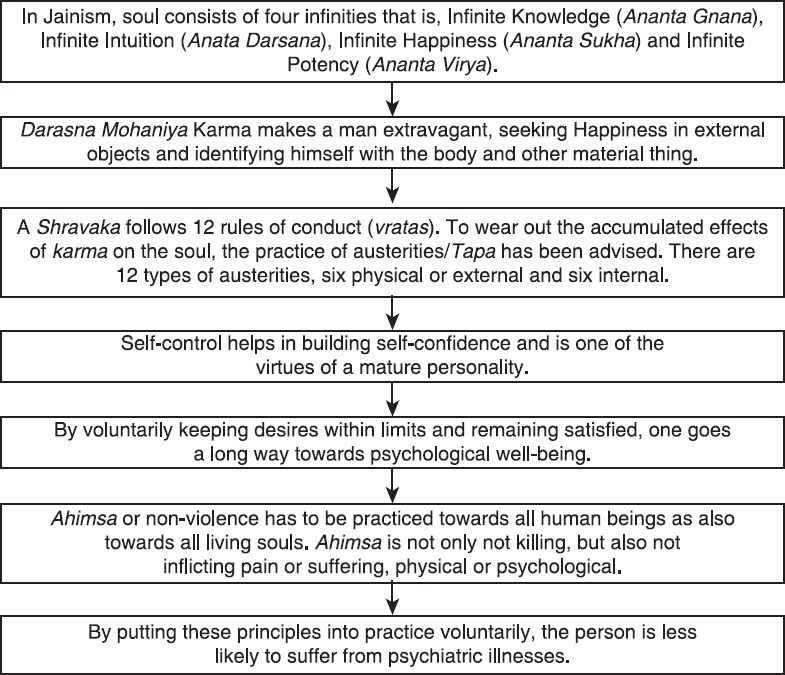

Conclusions [See also Figure 1: Flowchart of the Paper]

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the paper

The soul, according to Jainism, consists of four infinities, that is, Infinite Knowledge (Ananta Gnana), Infinite Intuition (Anata Darsana), Infinite Happiness (Ananta Sukha) and Infinite Potency (Ananta Virya). The cause of obstruction is known as Karman. It is composed of a material substance known as Karma Varna. The way to salvation demands a deliberate attempt of the soul to purify itself from the Karmic dirt by stopping the fresh accumulation and destroying the old. Darasna Mohaniya Karma makes a man extravagant, seeking happiness in external objects and identifying himself with the body and other material things. Charitra Mohaniya Karma has also the effects of emotion of Anger (Karodha), Conceit (Mana), Crookedness (Maya) and Greed (Lobha). The aspirant has to ascend gradually by subduing these passions by degrees. This is minutely and well-described in the Jaina theory of 14 Gunasthanas. A Shravaka follows 12 rules of conduct (vratas). By following them, he would be able to minimise the inflow of new karmas. To wear out the accumulated effects of karma on the soul, the practice of austerities/Tapa has been advised. There are 12 types of austerities, six physical or external and six internal.

The fourth vrata of a Shravaka is avoidance of sensual pleasure. Self-control helps in building self-confidence and is one of the virtues of a mature personality. The fifth vow of the Shravaka is undertaking to limit one's worldly possessions. By voluntarily keeping desires within limits and remaining satisfied, one goes a long way towards psychological well-being. Anger (Krodha), Conceit (Mana), Crookedness (Maya) and Greed (Lobha) have been grouped in Jainism as Ksaya Saghna. Because of the effects of these emotions, the soul is not able to achieve salvation or moksha. He, who practices meditation, is required to keep his body, mind and speech under perfect restraint. Jainism lays stress on the practice of self-mortification as a means of checking one's passions as well as of inducing mental concentration. Shravakas take a vow not to speak for few minutes, or a few hours or even a full day (Mauna Vrata). By this, again, one enhances self-control, and during this Mauna Vrata one also carries out introspection. Ahimsa or non-violence has to be practiced towards all human beings as also towards all living souls. Ahimsa is not only not killing, but also not inflicting pain or suffering, physical or psychological. In this manner, one recognises and respects others’ individuality, ideas, virtues and knowledge. This helps in the building up of positive interpersonal relationships.

By putting these principles into practice voluntarily, the person is less likely to suffer from psychiatric illnesses. These principles also help in prevention and treatment of certain psychiatric illnesses like neurosis, personality disorders, addictions, etc.

Take Home Message

(1) Self-control (2) meditation (3) introspection (4) concentration (5) positive Interpersonal Relationship are the principles of Jaina religion that can contribute to Positive Mental Health.

Questions That This Paper Raises

What are the Principles of other religions and how can they contribute to Mental Health?

Is religion a buffer against stress?

Can Mental Health Professionals collaborate with religious preachers to bring about positive mental health?

What are those common features of most religions that can be useful for mental health?

About the Author

Manilal T. Gada MD, DPM., BPS President 1989-1990, has been Head and Hon. Psychiatrist (Retd), Rajawadi Municipal General Hospital, Ghatkopar, Mumbai, and Hon. Prof of Psychiatry (Retd): D.Y. Patil Medical College Nerul, Navi Mumbai India. He has awarded numerous orations and awards, e.g., Tilak Venkoba Rao Oration, Indian Psychiatric Society in 1987; Dr. S.M. Lulla Oration: Bombay Psychiatric Society in 2000; Dr. L.P. Shah Oration: Indian Psychiatric Society Western Zonal Branch in 2006; President's Award for Best Scientific Paper, Indian Psychiatric Society, Western Zonal Conference in 1984; President's Award for Best Scientific Paper, Indian Psychiatric Society, Western Zonal Conference in 1997. He has also co-edited a Psychiatry Text Book, Essentials of Postgraduate Psychiatry, published in 2005 by Paras Medical Publishers, Hyderabad, India.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Declaration

This is a revised, updated version of a paper published as, ‘Jaina Religion and Psychiatry’, Bombay Psychiatric Bulletin, Vol. 1(1), June 1989. It is not submitted for publication elsewhere.

CITATION: Gada M. Jaina religion and psychiatry. Mens Sana Monogr 2015;13:70-81.

Peer reviewer for this paper: Anon

References

- 1.Vijay B. Guidelines of Jainism. Original in Gujarati. In: Ramappa K, editor. 1st ed. Mehsana: Sri Vishwa Kalyan Prakashan Trust; 1986. pp. 22–33. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vijay B. Guidelines of Jainism. Original in Gujarati. In: Ramappa K, editor. 1st ed. Mehasana: Sri Vishwa Kalyan Prakashan Trust; 1986. pp. 52–60. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vijay B. Guidelines of Jainism. Original in Gujarati. In: Ramappa K, editor. 1st ed. Mehsana: Sri Vishwa Kalyan Prakashan Trust; 1986. pp. 122–2. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vijay B. Guidelines of Jainism. Original in Gujarati. In: Ramappa K, editor. 1st ed. Mehsana: Sri Vishwa Kalyan Prakashan Trust; 1986. pp. 138–42. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Galia C. 1st ed. Mumbai: Galia Hiten; 2002. Glimpses of Jainism and Teaching of Lord Mahavir; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maharaj, Rajsekharsuriji AV. 2nd ed. Mahesana: Shrimad Yashovijayji Jain Sanskrut Pathshala; 1999. The Doctrines of Jainism; p. 56. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Suriji, Kirtichandra AS. Jainism in a Nutshell, Original in Gujarati. In: Shah BC, Shah NT, editors. 1st ed. Mumbai: Shah BC & Shah NT; 1988. pp. 30–1. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Suriji, Kirtichandra AS. Jainism in a Nutshell, Original in Gujarati. In: Shah BC, Shah NT, editors. 1st ed. Mumbai: Shah BC & Shah NT; 1988. pp. 39–45. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Suriji, Kirtichandra AS. Jainism in a Nutshell, Original in Gujarati. In: Shah BC, Shah NT, editors. 1st ed. Mumbai: Shah BC & Shah NT; 1988. pp. 64–5. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sethia KN. Mumbai: Sethia KN; 1985. Shri Samayik Pratikaman Sutra. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sethia KN. Mumbai: Sethia KN; 1985. Shri Samayik Pratikaman Sutra. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sethia KN. Mumbai: Sethia KN; 1985. Shri Samayik Pratikaman Sutra; p. 240. [Google Scholar]