Abstract

The paper discusses the issue of doctor-patient relationship in view of a changing world with special emphasis on mental health professionals. It takes into account transference and counter-transference issues in doctor-patient relationships. It deals with issues pertaining to consent and liabilities, confidentiality and patient protection. Role of a psychiatrist as a leader in the art of communication is touched upon. In the end issues about professional fees and ethics too is dealt with.

Keywords: Confidentiality and privilege, Consent, ‘Cuts’, and Ads, Ethics and legal aspects, Informed consent, Liability prevention, Malpractice and liabilities, Privacy, Professional fees, Professional liabilities

Introduction

I have noted a few painful facts while working in the field of psychiatry. Many a times, while tackling patients with psychosis, substance abuse and dementia, we become very mechanical. We show no respect to these patients, spend no time with them and treat them in the most autocratic way. We label them as ‘that paranoid schizophrenic’ rather than ‘Mr. X’. Sometimes, we, who are supposed to know the humane component in depth, treat these patients most condescendingly. We drug them and hospitalize them, without taking them into confidence. At the same time, many ethical and legal aspects have gradually emerged on the scene. With these points in view, I thought of focusing on the ‘Doctor-patient relationship’ in this communication.

Three Main Components

A psychiatric consultation has three main components:

Gathering necessary in-depth information to come to an appropriate diagnostic formulation;

Establishing a doctor-patient relationship;

Initiating and continuing various therapeutic measures.

Good patient-doctor relationship is like an excellent vehicle: With its help therapy becomes smooth. It:

Helps in better data collection;

Improves compliance with various treatment modalities;

Helps achieve better therapeutic results; and

Prevents unnecessary bitterness and subsequent legal hassles.

While a good doctor-patient relationship is most desirable, and is the best protection against legal hassles, it is also absolutely obligatory on ·the part of a psychiatrist to know certain ethical and legal aspects of his professional practice. I will discuss both these below.

Doctor-Patient Relationship

Doctor-patient relationship can be discussed under the following headings:

Factors pertaining to the patient;

Factors pertaining to the treating physician;

Approach towards the patient;

Model of approach;

Certain reportable conditions;

Consents;

Malpractice and liabilities;

Liability prevention;

Commercial aspects.

Let me discuss each of them one by one.

1. Factors pertaining to the patient

The patient comes to a psychiatrist not only with his presenting symptoms but also with certain expectations. He has faith in various treatment modalities and expectations about the outcome. Even the presenting symptoms differ from person to person, even though the underlying disease is the same.

Factors pertaining to the patient are determined by:

The personality of the individual, past experiences, methods of coping with sickness. Dependent personality expects miracles. Histrionic personalities have a tendency to exaggerate symptoms. Antisocial personalities show a hostile attitude towards a therapist. Paranoids patients show lack of faith in the doctor and doubt every intention and guidance provided by the doctor.

Society's view of sickness, society's and families’ expectations regarding the sick person. Many of the mental problems are considered a curse or mystical phenomenon. Hence, relatives may approach a psychiatrist with little faith in the doctor's healing abilities.

Economic factors, education, urbanisation: Affluent and educated families expect more time, more explanations and more flexibility from the treating doctor. They perceive doctor more as a friend and a guide. However, those who are not so educated and from non-affluent families expect a more authoritarian approach from the doctor; they treat the doctor as their saviour, and at times God. Urbanisation has resulted in a more critical approach.

The patient's feelings for the doctor (‘transference’). This may be determined by psychodynamic conflicts. The patient may perceive the doctor as a good/bad/caring/hostile brother/sister/father/mother as experienced in his own family in the past.

2. Factors pertaining to the treating physician

A doctor's interaction with his patient depends on many factors:

His training: Especially with reference to objectivity, empathy, ethical and legal issues and his own expectations about his patient;

His personality: Doctor with paranoid tendencies may feel threatened by the patient or his relatives. A therapist having a superiority complex may consider his patients as poorly educated and incapable of understanding the nuisances of therapy.

His preconceived notions: Especially about different types of patient and their socio-economic background. Also, a doctor may believe personality disorders as untreatable and hence his approach to the patient may be negative.

Physical and material aspects: If a doctor feels he is not given fair remuneration for his abilities he may ignore the patient.

Society's expectations about doctor's behaviour: A doctor is supposed to be a saviour, ever available, non-commercial. The doctor may find it difficult to live up to this role.

Counter-transference: We call a doctor's feelings towards the patient ‘counter transference’ and it has several psychodynamic components. A doctor may perceive his patient as good/bad father/brother/sister/son/daughter as per his own childhood experiences. This can positively/negatively impact therapy.

3. Approach towards the patient

Approach towards the patient should be scientific and is discussed under the following headings:

Non-judgmental approach with an open mind: Taking every new/old case as a new entity, the doctor must approach in textbook fashion and determine only from his inferences. Data from relatives are important, but that should not prejudice one's mind. Similarly, educational qualifications, social background, financial conditions should not come in the way of making a sound scientific evidence-based diagnosis and treatment plan.

Time and setting: Give the patient a patient hearing, let the setting be relaxed with least outside interference, less/no intrusions, with sufficient time for patient to elaborate and with the taking of appropriate notes.

Structured/non-structured interview: Depending on the therapist's approach, both methods can serve the purpose well. A combination of both and judicious mix is the best approach.

Good empathy and sincere effort to understand patient's feelings: This is the crux of the approach and can never be over-emphasised.

Involving relatives in an appropriate way: Relatives can offer valuable data and insights into the patient's condition while at times try to unduly influence therapy. It is necessary to ensure the first while being aware the second does not happen.

Assurance about confidentiality: Especially in psychotherapy, and with all patients, there must be an assurance that their case histories will not be revealed without their consent.

Discussion about various treatment modalities: This can be discussed with the patient in case the doctor feels that he has insight into his condition and can understand the same. If that is not possible, the relatives must always be taken into confidence.

Benevolence: To keep the humane factor in mind even while treating patients with limited capacity to assimilate what the psychiatrist is saying or doing.

4. Models of approach

We can discuss models of approach under the following heads:

Activity - passivity: In case of treating psychotic patients very active and may be at times an assertive attitude is necessary. Passive attitude from the doctor is seen in case where he feels nothing further can be done, or when he feels potential legal threats. Defensive approach is prevalent especially in psychiatry to ward off legal threats. While it is necessary to be cautious, one must not forget to ‘dare to care’.

Guidance, co-operation: At times, clients land up mainly for guidance on certain interpersonal or occupational matters, or seek cooperation to resolve interpersonal stresses, e.g., marital. The therapist must decide where advice ends and therapy starts. And where advice itself is therapy.

Mutual participation: The therapist may have to get involved in a mutual participatory model, wherein there is a lot of give and take of ideas and action plans. Clients, who prefer to take charge of their lives, but with specialised help, are especially suited for this model.

Social intimacy: The psychiatrist has more chances to develop social and physical intimacy with his patients. However, the guidelines maintain that this is unprofessional. In a case where you already have social intimacy with a patient, it is preferable to refer this patient to another psychiatrist.

5. Certain reportable conditions

Patient expressing suicidal or homicidal intentions: In case the doctor judges the ideas about suicide or homicide expressed in psychotherapy or otherwise as serious and/or life-threatening, communication must be made to relatives/relevant authority so that appropriate action can be taken. Lest breach of confidentiality be a concern, remember the Tarsoff Maxim still prevails, ‘Protective privilege ends when public peril begins’.

6. Consents

Informed consent is both an ethical and legal issue. It consists of the following components:

Information: The patient and relatives must be given reasonable information about the sickness and possible modes of treatment in the language they understand. Common side effects of any drugs need to be told.

Consent: Consent for any procedure or treatment is necessary. Either implied consent, oral consent or written consent, as the case may be.

Consent form: In case of procedures like electroconvulsive therapy in psychiatry, there is the need to have details in the language understood by the patient and his relatives.

Competence: This is the capacity to weigh, reason and make reasonable decisions based thereon. If a patient is incompetent, appropriate health care proxy, e.g., relatives must be involved [See point below].

Relatives’ consent: For practical reasons, when a patient is not competent, relative's consent for the treatment should be considered sufficient. However, when legal hassles are anticipated, e.g., litigious paranoid patient, it is best to abide by all prevalent legal procedures.

7. Malpractice and liabilities

Misdiagnosis: It is not expected that a psychiatrist should diagnose by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders or International Classification of Diseases system. But he must use his average skills in coming to conclusions. Legal issues arise when an organic condition in missed, and suicidal or homicidal risks are not properly evaluated.

Negligence in treatment: This includes under-treatment, over-treatment, wrong treatment, treatment without informed consent, involuntary treatment, side effects of treatment.

Improper hospitalisation: This includes hospitalisation due to false reasons and/or prolonged hospitalisation without valid reasons. When prolonged hospitalisation is necessary, the patient and relatives should be properly explained. If necessary, a second opinion should be sought even in case of voluntary admissions. Definite guidelines exist in the case of involuntary admissions and must be followed.

Improper relationship with the patient. Sexual relationship with a patient, exploiting a patient, social and economic deals with patient are not acceptable. As written earlier, even social intimacy with patient is not desirable. Any sexual or physical intimacy is considered malpractice.

-

Some unclear issues: There remain certain grey areas:

- Who bears responsibilities for mistakes done by subordinates?

- What is a psychiatrist's legal standing in a joint consultation?

8. Liability prevention

Liability prevention consists of the following:

Competent practice: Needless to say, the greater the competence, the lesser the need for liability prevention. Updating on knowledge and skills and judicious use of therapy is mandatory.

Documentation: Case histories and case records are a must. Even as case papers may be given to the patient, a record of the same in the office is a wise practice.

Knowledge of legal and ethical issues: Adequate knowledge of legal and ethical issues to anticipate and abort potential liability action is necessary for a clinician, much as he cares for and is dedicated to patient welfare. One must remember ‘Ignorance of law is no excuse’. Also, remember the Bolam principle which states that management of a patient should be in accordance with a practice accepted at the time as proper by two different responsible groups of medical opinion of the same speciality.

Consultation second opinion in difficult and complex cases: It is always wise to seek a second opinion or senior's opinion in difficult and complex cases. This does not undermine one's authority, rather it adds a necessary alternative opinion and outlook which may help patient welfare, and also protect the doctor against potential liability threats.

Informed consent. This had been discussed earlier.

Better doctor-patient relationship: This is the refrain of this whole paper. Better the relationship, lesser the chance of liability hassles.

Insurance coverage: In spite of doing the best of everything, Medical Indemnity insurance must be taken; for, sometimes, the best of intentions, procedures and therapies may not guarantee immunity from potential legal difficulties.

9. Commercial aspects

Professional fees: In private practice, a doctor has the right to charge his appropriate fees. He should reveal his fees to the patient at the first interview if asked about it. If not, charging appropriate fees depends upon time, area of practice, seniority, etc. If the patient refuses, or is unable to pay, politely guide him regarding other avenues for treatment; or, if felt appropriate, give due consideration to his limitations by lowering the fees. Withholding prescription and advice because patient cannot pay is generally not done at the first interview.

First interview: It is necessary at the end of the first interview to discuss further line of treatment, the possible costs, the possible length of treatment as also giving the patients/relatives some idea about realistic outcome of treatment. This helps them determine further involvement with therapy.

Payment issues: Problems are faced by a doctor when a patient, even after due explanation, does not pay or underpays for professional services, hospitalisation, medicines and other expenses. Certain precautionary measures here are involving relatives, referring agencies, referring doctor and taking an adequate deposit.

‘Cuts’ and Ads: Sharing profits with referring agencies, money spent for public relations, direct or indirect advertisements, obliging referring agencies in cash or kind, are all issues in which there are straight and clear-cut ethical guidelines which prohibit them. However, in reality, there exists a lot of confusion about and connivance of these guidelines.

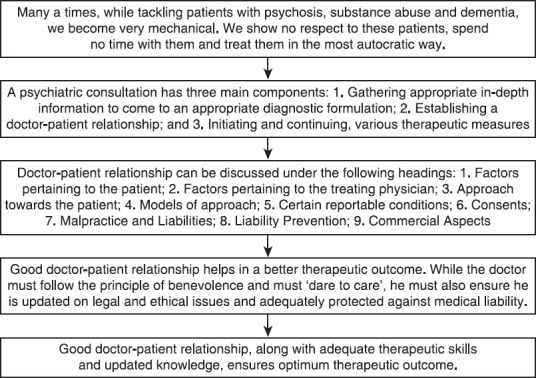

Conclusions [Figure 1: Flowchart of the Paper]

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the paper

In this paper, the author has discussed the issue of doctor-patient relationship. It is never taught and often taken for granted. This has to be seen from various aspects: the patient, doctor, the approach and the model of approach, certain reportable conditions, consents, malpractices, liabilities and also its prevention and commercial aspects. In fact, good doctor-patient relationship helps in a better therapeutic outcome. While the doctor must follow the principle of benevolence and must ‘dare to care’, he must also ensure he is updated on legal and ethical issues and adequately protected against medical liability.

Take Home Message

Good doctor-patient relationship, along with adequate therapeutic skills and updated knowledge, ensures optimum therapeutic outcome.

Questions that this Paper Raises

What is the essence of a good doctor-patient relationship? How are they different in psychiatry compared to other medical disciplines?

How does one best avoid legal hassles?

Which ethical and legal issues remain prime considerations in psychiatric practice?

Is doctor-patient relationship culture-based and are there some common factors applicable to all societies?

About the Author

Paresh D Lakdawala M.D, D.P.M, M.N.A.M.S. is a privately practicing psychiatrist in Mumbai for the last 35 years. He has had a meritorious track record, winning a National Scholarship, Dr. N.D. Patel prize in medicine and the Merck gold medal. He was the President of Bombay Psychiatric Society in the year 1992-1993. He has been Lecturer in Psychiatry, L.T.M.G. Hospital and College Mumbai, Sr. Research Fellow, WHO Collaborating Center in Psychopharmacology at KEM Hospital, Asst Child Psychiatrist at Wadia Hospital for Children, and Hon Asst Professor in Psychiatry at G.S Medical College and K.E.M. Hospital, Mumbai. Currently, he is in private practice as a consultant psychiatrist and consultant psychiatrist at Bhatia Hospital. He retired as a consultant psychiatrist at H. N. Hospital and Conwest Jain Clinic, Mumbai. He has publications in psychopharmacology, childhood depression, trans-sexuality and social psychiatry. He has also authored a book chapter on Childhood depression in the API Textbook of Medicine Fourth and Fifth editions, published by Association of Physicians of India, 1986 and 1992.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Declaration

This is a revised, updated version of a paper published as, ‘Doctor-Patient Relationship in Psychiatry’, Bombay Psychiatric Bulletin, V, Combined Annual Issue, 1993-1995, pg. 3-6. It is not submitted for publication elsewhere.

CITATION: Lakdawala PD. Doctor-patient relationship in psychiatry. Mens Sana Monogr 2015;13:82-90.

Peer reviewer for this paper: Anon