Abstract

Dairy foods are rich in bone beneficial nutrients, yet the role of dairy foods in hip fracture prevention remains controversial. The objective was to evaluate the association of milk, yogurt, cheese, cream and milk+yogurt intakes with incident hip fracture. 830 men and women from the Framingham Original Cohort, a prospective cohort study, completed a food frequency questionnaire (1988–89) and were followed for hip fracture until 2008. In this population-based study, Cox-proportional hazards regression was used to estimate Hazard Ratios (HR) by categories of energy-adjusted dairy intake (servings/week) adjusting for standard confounders. The exposure was energy adjusted intakes of milk, yogurt, cheese, cream and milk+yogurt (servings/wk). Risk of hip fracture over the follow-up was the primary outcome; the hypothesis being tested was formulated after data collection. The mean age at baseline was 77y (SD:4.9, range: 68–96). 97 hip fractures occurred over the mean follow-up time of 11.6y (range: 0.04–21.9y). The mean±SD (servings/wk) of dairy intakes at baseline were: milk=6.0±6.4, yogurt=0.4±1.3, cheese=2.6±3.1; cream=3.4±5.5. Participants with medium (>1 and <7serv/wk) or higher (≥7serv/wk) milk intake tended to have lower hip fracture risk than those with low (≤1serv/wk) intake [HR(95%CI): high vs low intake: 0.58 (0.31–1.06), P=0.078; medium vs. low intake: 0.61 (0.36–1.08), P=0.071; P trend: 0.178]. There appeared to be a threshold for milk, with 40% lower risk of hip fracture among those with medium/high milk intake, compared to those with low intake (P=0.061). A similar threshold was observed for milk+yogurt intake (P=0.104). These associations were further attenuated after adjustment for femoral neck bone mineral density. No significant associations were seen for other dairy foods (P range, 0.117–0.746). These results suggest that greater intakes of milk and milk+yogurt may lower risk for hip fracture in older adults through mechanisms that are partially, but not entirely, due to effects on bone mineral density.

Keywords: Dairy, milk, hip fracture, cohort study

INTRODUCTION

Osteoporosis is a disease characterized by low bone mass and progressive deterioration of bone tissue 1. There are several critical public health implications of osteoporosis including increased risk of fracture, loss in physical function, increased mortality and morbidity, and decreased quality of life 2. It is estimated that among the 10 million Americans over the age of 50 years who have osteoporosis 3, approximately 1.5 million suffer from osteoporotic fractures every year 4. Hip fractures are the most serious of the osteoporotic fractures as they almost always lead to hospitalization and result in permanent disability for approximately 50% and mortality for approximately 20%, of patients 5.

Milk and other dairy products provide a complex source of essential nutrients, including protein, calcium, phosphorus, potassium, and magnesium and, in the United States, are often fortified with vitamin D, thus contributing to bone health 6. Furthermore, fortified milk is also a good source of vitamin D. Previous research has suggested a positive relationship between milk intake and bone mineral density (BMD) 7–10, but not with hip fracture 11–14. A meta-analysis examining middle-aged or older persons concluded that there was no overall association between milk consumption and hip fracture risk in women, but that more research was needed in men 15. Previous studies of BMD have focused primarily on young, premenopausal women 16–19, and most evaluated milk intake but did not examine other sources of dairy, which may be important as the nutritional profiles of dairy foods are not uniform. For example, cream and cream products have higher levels of saturated fat and sugar but lower levels of bone-specific nutrients such as calcium, vitamin D and protein than do lower fat dairy products. In our previous study, cream intake was associated with lower hip BMD 10. Taken together, the evidence supporting an association between dairy food intake and hip fracture risk among older adults remains unclear.

Therefore, the purpose of the present study was to determine the association of dairy food intake [milk, yogurt, cheese, cream and milk+yogurt with risk of hip fracture in older adults from the Framingham Original Cohort, which included both men and women followed for approximately 10 years for incident hip fracture. Our hypothesis was that all dairy foods, except cream, would be protective against the risk of hip fracture in older men and women.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The Framingham Heart Study, begun in 1948, examined risk factors for heart disease in a cohort of 5,209 men and women aged 28–62 y, selected as a population based sample of two thirds of the households in Framingham, MA, USA. The cohort has been examined biennially for more than 50 y 20. In 1988–1989, there were 1,402 surviving participants from the Original Cohort who participated in the Framingham Osteoporosis Study and formed the baseline examination for this study. We excluded participants with missing or incomplete food frequency questionnaires (FFQ), based on the criteria of >12 food items left blank or with energy intakes <2.51 or >16.74 MJ (<600 or >4000 kcal/d). Of 976 participants with complete FFQ and fracture information, we further excluded 146 with prior hip fracture, 62 with missing information on dairy food intake, and four with missing covariate information. The final analytic sample (n=764) was followed for incident hip fracture from the date of FFQ completion to the end of 2008. All participants provided written informed consent. The Institutional Review Board for Human Research at Boston University and Hebrew SeniorLife approved this study.

Dietary assessment

Usual dietary intake was assessed in 1988–1989 with a semi-quantitative, 126-item Willett FFQ 21. Questionnaires were mailed to the study participants. They were asked to complete them, based on their intake over the previous year, and to bring them to the examination, where they were reviewed with clinic staff. This FFQ has been validated against multiple diet records and blood measures for many nutrients in several populations 22, 23. An earlier version of this FFQ was validated against dietary records, with food intake for seven consecutive days at four times during a 1-year interval, among 173 women from the Nurses’ Health Study 24. The corrected correlation coefficients between the FFQ and seven day records ranged from 0.57 to 0.94 for dairy products. Dairy intake was assessed in servings per week, using the food list section of the FFQ. Willett’s questionnaire specifies the serving size for each dairy food as follows: milk, skim/low fat/whole (8 oz. glass), ice milk (1/2 cup), cottage or ricotta cheese (1/2 cup), other cheese (1 slice or 1 oz. serving), cream (1 Tbs.), sour cream (1 Tbs.), ice cream (1/2 cup), cream cheese (1 oz.), and yogurt (1 cup). Milk intake was calculated as the combined intake of skim milk, low fat milk, whole milk, and ice milk. Cheese intake was calculated as the combined intake of cottage/ricotta cheese and other cheeses. The variable “other cheese” included American, Cheddar etc. plain or as part of a dish (1 slice or 1 oz. serving). Cream intake was calculated as the combined intake of cream, sour cream, ice cream, and cream cheese. Yogurt intake was also estimated in servings per week. In our previous work on dairy intake and bone health in the Framingham Offspring Cohort 10, we reported beneficial effects of milk and yogurt on hip BMD. Therefore, we decided to examine the combined intake of milk and yogurt (milk+yogurt) in servings per week.

Assessment of hip fracture

As reported previously 25, all records of hospitalizations and deaths for the study participants were systematically reviewed for occurrences of hip fracture. Beginning in 1983, hip fractures were reported by interview at each examination or by telephone interview for participants unable to attend an examination. Reported hip fractures were confirmed by review of medical records, radiographic and operative reports. For this analysis, incident hip fracture was defined as a first-time fracture of the proximal femur, which occurred over follow-up after the dietary assessment in 1988–1989 through December 2008.

Potential confounding factors

Previous studies on this and other groups have reported several major risk factors for osteoporosis, which informed our inclusion of potential confounding variables such as age, female sex, height, weight, current smoking, physical activity, current estrogen use in women, calcium, vitamin D and multivitamin supplement use. All covariates were measured at the time of dietary assessment in 1988–1989, except for maximum adult height, which was measured at the first examination in 1948–51 without shoes, in inches. Weight was measured in pounds with a standardized balance-beam scale. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as height (m2) divided by weight (kg). Smoking status was assessed from questionnaire data, with two groups (those who never smoked cigarettes or smoked in the past and current smokers). Physical activity was measured with the Framingham physical activity index, an estimated measure of energy expenditure calculated from questions about number of hours spent in heavy, moderate, light, or sedentary activity and number of hours spent sleeping during a typical day 26. Each component of these 24-h summaries was multiplied by an appropriate weighting factor on the basis of the estimated level of associated energy expenditure and summed to arrive at a physical activity score. For estrogen use, women were divided into two groups: 1) those currently using estrogen or who had been using continuously for >1 year in the past two years and 2) those who had never used estrogen, had only used it previously or, although currently using, had used it for <1 year, as past or short-term use does not sustain bone benefits 27. Intake of total energy, calcium and vitamin D were estimated using the food list section of the FFQ. Intakes of calcium, vitamin D or multivitamin supplements, as recorded on the supplement section of the FFQ, were coded as yes-no variables. Final models were adjusted for baseline BMD at the femoral neck measured in 1988–1989 using a Lunar DP2 dual photon absorptiometer, to examine if baseline femoral neck BMD was in the pathway of the association of dairy intake with fracture.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive characteristics were calculated for the combined sample of men and women. The distribution of dairy food intakes (defined as milk, yogurt, cheese, cream and milk+yogurt intakes) were examined. Variables were energy adjusted using the residual method. 28 Dairy food intakes were energy-adjusted residuals added to a constant, where the constant equals the dairy food intake for the mean energy intake of the study population. These energy-adjusted dairy food variables (servings/week) were then examined as continuous as well as categorical variables. Milk intake was categorized in servings per week as: low ≤ 1, medium > 1 and < 7 or high ≥ 7 servings per week. Yogurt intake was categorized as none versus any intake (> 0 servings/week). Cheese intake was categorized as minimal ≤ 1 versus some > 1 serving per week. Cream intake was categorized as low < 0.5, medium ≥ 0.5 and < 3 or high ≥ 3 servings per week. Milk+yogurt intake was categorized as low ≤ 1, medium > 1 and <10 or high ≥ 10 servings per week. Dairy intakes were adjusted for total energy intake using the residual method 29. Assumptions for Cox proportional hazards regression were tested and met. Hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals were estimated for men and women combined using Cox proportional hazards regression, adjusting for potential confounders and covariates. Hazard ratios were used to estimate the relative increase in the risk of hip fracture for each of the higher intake categories, compared with the lowest category (referent). For dairy intake, linear trends across the categories were also examined.

Multivariable analyses initially adjusted hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals for age (y), sex, weight (kg), height (inches), and total energy intake (Kcal/d). Subsequent models were adjusted for calcium and vitamin D supplement use (y/n) and current smoking (y/n). In the process of model building, any covariate that changed the β-coefficient of the primary exposure by >10% was included in the final parsimonious model. Based on this method, physical activity, estrogen use and multivitamin use were excluded from the final models presented. Final models were adjusted for baseline femoral neck BMD (FN-BMD) to determine the possibility that a dairy effect on fracture involved BMD in the pathway.

Hazard Ratios for medium and high intake categories were similar for milk and milk+yogurt intakes, suggesting a threshold effect. Therefore, we re-examined the final models (with and without adjustment for FN-BMD) using milk intake categories defined as: low ≤ 1 versus medium/high > 1 serving per week and milk+yogurt intake categories defined as: low ≤ 1 versus medium/high > 1 serving per week.

All analyses were performed using SAS statistical software (SAS user’s guide, version 9.3; SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). A nominal two-sided p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant for all the analyses.

RESULTS

Subject characteristics

The mean age at baseline was 77 y for men and women combined (SD, 4.9; range, 68–96y) (Table 1). Seventeen percent of participants were calcium supplement users; and 27% were vitamin D supplement users. Mean dietary calcium intake was 726 mg/d (SD, 350) and mean dietary vitamin D was 221 IU/d (SD, 145). Mean total milk intake was 6 servings/wk (SD, 6.4; range, 0–42.0). Milk and yogurt comprised ~52% of total dairy intake. Intake of yogurt was limited in women (mean intake: 0.57 ± 1.5 servings/wk, range: 0 to 17.5 serv./wk) and even less in men (mean intake: 0.20 ± 0.87 servings/wk, range: 0–7 servings/wk). There were 97 (13%) incident hip fractures over an average follow-up period of 11.6 years (SD, 6.0; range: 0.04–21.9 years).

Table 1.

Characteristics of 764 men and women from the Framingham Original Cohort.

| Characteristics | Mean ± SD |

|---|---|

| Age (years) range: 68–96 | 76.9 ± 4.9 |

| Body Mass Index (Kg/m2) Range: 15.4–51.6 | 25.6 ± 4.5 |

| Weight (Kg) | 70.1 ± 14.4 |

| Height (inches) | 65.1 ± 3.5 |

| Total energy (Kcal/d) | 1743 ± 586 |

| Dietary calcium (mg/d) | 726 ± 350 |

| Dietary vitamin D (IU/d) | 221 ± 145 |

| Total milk (servings/week) | 6.0 ± 6.4 |

| Total cheese (servings/week) | 2.6 ± 3.1 |

| Total cream (servings/week) | 3.4 ± 5.5 |

| Yogurt (servings/week) | 0.43 ± 1.3 |

| Milk+yogurt (servings/week) | 6.4 ± 6.7 |

| Physical Activity Scale for Elderly (PASE) | 33.6 ± 5.6 |

| n, (%) | |

| Incident Hip fractures | 97 (12.7) |

| Current smokers | 76 (10.0) |

| Calcium supplement use | 130 (17) |

| Vitamin D supplement use | 208 (27) |

| Current estrogen use | 6 (1.3) |

Unadjusted dairy intake variables are in the original scale (Servings/week)

When dairy food intake was examined as a continuous variable, after initial adjustment for age, sex, weight, height, and total energy intake, there were no statistically significant associations between milk, yogurt, cheese, cream or milk+yogurt intake with risk of hip fracture (P range, 0.133–0.819) (data not shown). There was a modest 3% increased risk of hip fracture for every serving increase of cream per week. However, these associations did not reach significance (HR=1.03; 95% CI=0.99–1.06; P=0.133). In the full models, additional adjustment for current cigarette smoking, calcium supplement use, and vitamin D supplement use did not change the results for any dairy food (P range, 0.182–0.779; Table 2).

Table 2.

Association of dairy intake (servings/week) with the hip fracture risk in 764 participants from the Framingham Original Cohort.

| Dairy Exposures (servings/week)a |

n hip fractures | Hazard Ratiob |

95% Confidence Intervals |

Variable P valuec |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Milk | 97 | 0.995 | 0.962–1.029 | 0.779 |

| Yogurt | 97 | 0.948 | 0.796–1.113 | 0.554 |

| Cheese | 97 | 0.975 | 0.901–1.055 | 0.526 |

| Cream | 97 | 1.024 | 0.989–1.060 | 0.182 |

| Milk+yogurt | 97 | 0.993 | 0.961–1.026 | 0.689 |

Dairy food intakes were energy-adjusted residuals added to a constant, where the constant equals the dairy food intake for the mean energy intake of the study population.

Parsimonious models adjusted for age (y), sex, weight (kg), height (inches), total energy intake (Kcal/d), current cigarette smoking (yes/no), calcium supplement use (yes/no) and vitamin D supplement use (yes/no)

† P>0.05 and P<0.1

When dairy food intakes were examined as categorical variables, after initial adjustment for age, sex, weight, height, and total energy intake, participants with higher milk intake had 43% (≥7 servings/wk) and 39% (>1 and <7 servings/wk) lower risk of hip fracture compared to those with low milk intakes (≤1 serving/wk) (highest milk intake: HR=0.57; 95% CI=0.31–1.05; P=0.078, medium intake: HR=0.61; 95% CI=0.35–1.06; P=0.071; P trend=0.172). In addition, participants with higher milk+yogurt intake had 37% (≥10 servings/wk) and 35% (>1 and <10 servings/wk) decreased risk of hip fracture compared to those with low milk+yogurt intake (≤1 servings/wk) (highest milk+yogurt intake: HR=0.63; 95% CI=0.35–1.14; P=0.133 medium milk+yogurt intake: HR=0.65; 95% CI=0.38–1.13; P=0.136, P trend=0.277). However, these associations did not reach statistical significance. Additional adjustment for current cigarette smoking, calcium and vitamin D supplement use, in the full models, did not change these associations (Table 3). Similarly, no significant associations were observed for other sources of dairy intake (P range, 0.117–0.746).

Table 3.

Association of dairy intake categories (servings/week) with the hip fracture risk in participants from the Framingham Original Cohort (n=764).

| Dairy Exposures (servings/week) a |

Incident hip fractureb |

Hazard Ratio (95% Confidence Intervals)c |

Variable P valued |

P trend |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Milk | 0.178 | |||

| Low intake ≤ 1 | 20/108 | Ref | -- | |

| Medium intake > 1 and < 7 | 50/422 | 0.61 (0.36–1.08) | 0.071† | |

| High intake ≥ 7 | 27/234 | 0.58 (0.31–1.06) | 0.078† | |

| Yogurt | -- | |||

| No intake 0 | 77/627 | Ref | -- | |

| Yes intake > 0 | 20/137 | 1.09 (0.65–1.81) | 0.746 | |

| Cheese | -- | |||

| Minimal intake ≤ 1 | 52/358 | Ref | -- | |

| Some intake > 1 | 45/406 | 0.72 (0.48–1.08) | 0.117 | |

| Cream | 0.601 | |||

| Low intake < 1 | 21/167 | Ref | -- | |

| Medium intake ≥ 1 and < 3 | 35/284 | 0.86 (0.47–1.58) | 0.626 | |

| High intake ≥ 3 | 41/313 | 1.04 (0.59–1.86) | 0.881 | |

| Milk+yogurt | 0.278 | |||

| Low intake ≤ 1 | 20/119 | Ref | -- | |

| Medium intake > 1 and <10 | 48/405 | 0.65 (0.37–1.14) | 0.136 | |

| High intake ≥ 10 | 29/240 | 0.63 (0.34–1.15) | 0.133 | |

Dairy food intakes were energy-adjusted residuals added to a constant, where the constant equals the dairy food intake for the mean energy intake of the study population.

Incident hip fractures were calculated as the number of persons with hip fracture at the end of the follow-up/ total number of persons at risk of hip fracture at the beginning of the follow-up.

Parsimonious models were adjusted for age (y), sex, weight (kg), height (inches), total energy intake (Kcal/d), current cigarette smoking (yes/no), calcium supplement use (yes/no), vitamin D supplement use (yes/no).

HR significantly different from HR in the lowest category,

P<0.10.

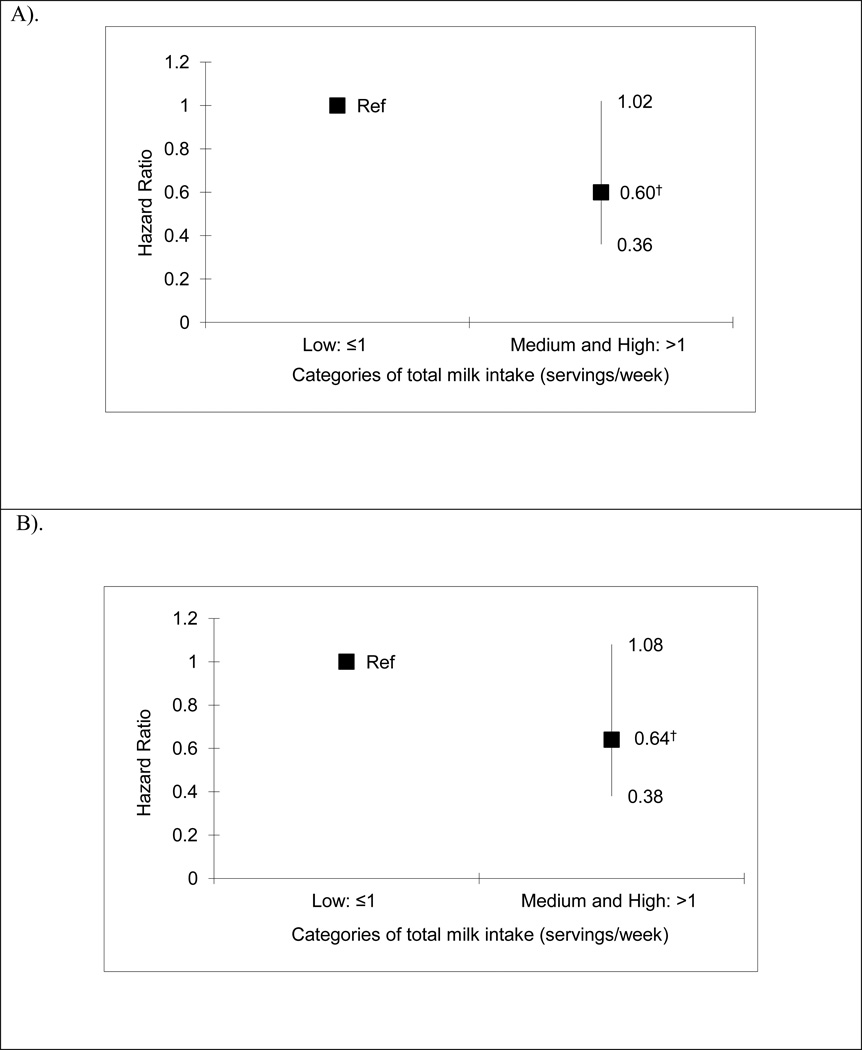

When milk intake was analyzed as low versus medium/high intake, participants with medium/high milk intake (>1 serving/wk) had 40% lower risk of hip fracture, compared to those with low milk intake (≤1 serving/wk) (medium/high milk intake: HR=0.60; 95% CI=0.36–1.02; P=0.061, Figure 1). These associations were attenuated after adjustment for FN-BMD (P=0.101, Figure 1). Similarly, when milk+yogurt intake was analyzed as low versus medium/high intake, participants with medium/high milk+yogurt intake (>1 serving/wk) appeared to have 20% lower risk of hip fracture, compared to those with low milk+yogurt intake (≤1 servings/wk) (medium/high milk intake: HR=0.80; 95% CI=0.62–1.04; P=0.104). These associations did not change after adjustment for FN-BMD (P=0.122).

Figure 1.

Parts A–B. Association of dairy intake categoriesa with hip fracture risk in 764 older adults from the Framingham Original Cohort.

A). Hazard Ratiosb were adjusted for age (y), sex, weight (kg), height (inches), total energy intake (Kcal/d), current cigarette smoking (yes/no), calcium supplement use (yes/no), vitamin D supplement use (yes/no).

B). Hazard Ratiosb in panel A were additionally adjusted for baseline femoral neck bone mineral density (FN-BMD).

a Dairy food intakes were energy-adjusted residuals added to a constant, where the constant equals the dairy food intake for the mean energy intake of the study population.

b † P>0.05 and P<0.1

DISCUSSION

This prospective study examined associations between individual dairy food intakes and risk of incident hip fracture in older men and women over a relatively long follow-up period. Threshold effect was observed for milk intake that was suggestive of a protective association for higher levels of milk intake with hip fracture risk over a mean follow-up of 11.6 years. This strength of the association was attenuated, but remained marginally significant after final adjustment for baseline FN-BMD, confirming that at least some of the association between milk intake and risk for hip fracture are due to effects on BMD. Similar, threshold effect was also observed for milk+yogurt intake though the effect estimates indicating protective associations were only marginally significant. No statistically significant associations were observed between other dairy foods and hip fracture risk.

Evidence from previous studies suggests a significant role for dairy intake 9, 10, 17, 30–32 and related nutrients 33, 34 in maintaining BMD. However, the evidence for hip fracture remains weak. Results from the largest cohort study to date on this topic were based on 72,337 postmenopausal women with 18-year follow-up for self-reported hip fractures; they showed no association between milk intake and the risk of hip fracture 13; although a recent meta-analysis that included this study suggested that more data are required, particularly for men 15. A meta-analysis including six prospective cohort studies with 195,102 women sustaining 3,574 hip fractures reported that, in women aged >35 years, there was no overall association between total milk intake and hip fracture risk (pooled RR per glass of milk per day = 0.99; 95% CI=0.96–1.02; Q-test p = 0.37). However, the same study also included three prospective cohort studies with 75,149 men sustaining 195 hip fractures and reported that more data were needed in men aged >40 years (pooled RR per glass of milk per day=0.91; 95% CI=0.81–1.01) 15. Similarly, no associations were observed for milk intake and hip fracture risk in a previous meta-analysis that included six prospective cohort studies 35.

A recent prospective cohort study with more than 22 years of follow-up in >96,000 white postmenopausal women from the Nurses’ Health Study, and men aged 50 years and older from the Health Professionals Follow-up Study, reported that teenage milk consumption (assessed retrospectively using an FFQ) was not associated with hip fracture in women (RR = 1.00 per glass per day; 95%CI, 0.95–1.05), and was associated with greater risk in men (RR = 1.09; 95%CI, 1.01–1.17), after adjustment for adult milk consumption. However, when further adjusted for height, no significant associations were observed for milk intake and hip fracture risk in men (RR = 1.06; 95%CI, 0.98–1.14). Cheese consumption was also not associated with hip fracture risk in men or women, which could be due to low cheese intake during teenage years reported in this study 36. However, results from this study cannot be compared directly to the current study from the Framingham cohort, because Feskanich et al. examined the effect of milk intake during teenage years to hip fracture later in life, adjusting for adult milk consumption among men and women aged 40–75 years, while the current study aimed to examine adult milk consumption and hip fractures later in life, in relatively older men and women (mean age: 76y and range: 68–96 years). In a meta-analysis of 6 prospective cohort studies, Kanis et al. reported that low intake of milk (<1 glass of milk per day) was associated with an increased risk of osteoporotic fracture only from the age of 80 years.35 Although the same was not observed with hip fracture, this could perhaps explain the discrepant findings from the Framingham Original Cohort compared to some previous studies with relatively younger participants of <75 years of age.

On the other hand some studies do support a protective association between milk intake and fracture risk. Results from the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (1988–1994) of 3,251 adult women (aged >20 y) showed that women with milk intake < one serving/wk during childhood (assessed via 24-hour recall questionnaire) was associated with 2-fold greater risk of fracture of the hip, wrist or spine 17. Also, a study of 4,573 Japanese men and women (aged: 59 years) showed a marginally significant protective effect of milk consumed five or more times per week compared to those consuming one or less servings per week [HR: 0.54 (0.25–1.07)] 37. Our previous study, using data from the Framingham Offspring Cohort, examined the association of dairy food intake and hip fracture risk in men and women with a mean age of 55±1.6 years (range: 26–85) over a 12-y follow-up 10. In that study, yogurt intake showed a weak protective trend for hip fracture with higher intakes [HR (95%CI) compared to no intake: ≤4 servings/week: 0.46 (0.21–1.03), >4 servings/week: 0.43 (0.06–3.27); P trend=0.06]. However, no other dairy intakes were significantly associated (HRs range, 0.53–1.47). Compared to other studies, the Framingham Offspring participants included mostly middle-aged men and women, with fewer fractures and hence, limited power to detect associations. The current study includes older men and women (aged: 68–96 years) from the Framingham Original cohort, with 97 confirmed hip fractures over a mean of almost 11.6y of follow-up.

The current study showed different results when dairy intake variables were treated as continuous (Table 2) versus when they were categorized (Table 3). There could be two reasons for this. First, the distribution of crude dairy variables was not-normal. While the distribution of the energy adjusted residuals for some dairy variables was close to normal, for other dairy variables it was not. Second, it is possible that the decrease in hip fracture risk with higher milk intake was non-linear. In fact, there seemed to be a threshold effect for milk intake as well as for milk+yogurt intake (Table 3), where the risk of hip fracture appeared to be lower in medium and high milk drinkers compared to those with low milk intake (<1 serving/week). When the medium and high milk drinkers were combined, the results suggested that medium to higher milk intake was protective against hip fractures compared to low intake (<1 serving/week).

The strengths of this study include the population-based prospective cohort design, with a long follow-up for fracture in both men and women. Only confirmed hip fractures were used and specific dairy foods were examined. However, this study had several limitations. The dietary assessment was conducted by FFQ, which is a semi-quantitative questionnaire that rank orders usual intakes. However, the FFQ used in this study has been validated for use in this population and several others 24. The complete dietary data were available only at baseline and, therefore, we were unable to adjust for secular change in diet during the follow-up period. However, we evaluated average milk intake over follow-up exams (in 1988–1992 and 1990–1994) for the smaller subset of participants with repeated dietary assessments and found that milk intake did not change significantly. Furthermore, the results of this study are generalizable only to non-Hispanic white men and women. Lastly, in any observational study, residual confounding may occur, despite control for several potential confounders.

In 2004, McCarron and Heaney reported that there could be an estimated 5-year savings in healthcare cost of $14 billion for treating osteoporotic fractures in the U.S. if the recommended intake of dairy products (3 servings per day) was met 38. Our current study contributes to the body of scientific information supporting a beneficial effect of dairy intake on hip fracture risk among older adults. Milk intake, the most commonly consumed dairy food seemed to be protective against the risk of hip fracture in this cohort of older men and women, and this appeared to be partially mediated through BMD. However, associations were marginally significant after adjusting for BMD, suggesting that there may be other mechanisms, such as effects on bone strength, structure or other contributors to fracture risk such as falls. Other specific dairy foods were not associated with hip fracture risk. Some foods, particularly yogurt, were consumed in small amounts with limited variability, making it difficult to see a potential effect.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Drs. Sahni and Hannan have unrestricted research grants from General Mills Bell Institute of Health and Nutrition. Dr. Kiel reports being on the scientific advisory board of Merck Sharp and Dohme, Amgen, Eli Lilly and Novartis, has institutional grants from Merck Sharp and Dohme, Amgen, Eli Lilly and reports receiving royalties from Springer for editorial work and author royalties from UpToDate®. Dr. Tucker reports receiving royalties from Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins for editorial work and travel compensation for annual meetings from International Life Sciences Institute (ILSI) North America for her work as a scientific advisor.

Sources of support: NIH R01 AR53205, R01 AR/AG 41398, NHLBI’s Framingham study contract #N01-HC-25195; unrestricted research grant from General Mills Bell Institute of Health and Nutrition; NIH's National Institute of Aging (T32-AG023480); Friends of Hebrew SeniorLife.

Role of Sponsors: General Mills Bell Institute of Health and Nutrition reviewed the manuscript but did not participate in changing the manuscript. NIH's National Institute of Aging (T32-AG023480) and Friends of Hebrew SeniorLife supported Dr. Mangano’s work on this project. Approval of the manuscript and the decision to submit the manuscript for publication was made by the authors.

Footnotes

Disclaimer: The views expressed in the submitted article are of the authors and not an official position of the institution or the funding institutions.

Author Contributions: Dr. Sahni had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study Concept and Design: Sahni, Hannan

Acquisition of data: Hannan, Kiel, Sahni

Analysis and Interpretation: Sahni, Mangano, Tucker, Kiel, Casey, Hannan

Drafting of the manuscript: Sahni, Mangano, Hannan

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Sahni, Mangano, Tucker, Kiel, Casey, Hannan

Statistical analysis: Sahni, Mangano

Obtained funding: Sahni, Hannan

Administrative, technical, or material support: Casey

Study supervision: Sahni

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: All authors have completed and submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Drs. Mangano and Casey report no conflicts.

Contributor Information

Shivani Sahni, Email: ShivaniSahni@hsl.harvard.edu, Assistant Scientist II, Institute for Aging Research, Hebrew SeniorLife; Instructor, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Harvard Medical School.

Kelsey M. Mangano, Email: KelseyMangano@hsl.harvard.edu, Post-Doctoral Fellow, Institute for Aging Research, Hebrew SeniorLife, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Harvard Medical School.

Katherine L. Tucker, Email: Katherine_Tucker@uml.edu, Professor, University of Massachusetts, Lowell, MA; Adjunct Professor, Northeastern University, Boston, MA.

Douglas P. Kiel, Email: Kiel@hsl.harvard.edu, Senior Scientist, Institute for Aging Research, Hebrew SeniorLife; Professor, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Harvard Medical School.

Virginia A. Casey, Email: VirginiaCasey@hsl.harvard.edu, Project Director, Institute for Aging Research, Hebrew SeniorLife.

Marian T. Hannan, Email: Hannan@hsl.harvard.edu, Senior Scientist, Institute for Aging Research, Hebrew SeniorLife; Associate Professor, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Harvard Medical School.

REFERENCES

- 1.Harvey N, Dennison E, Cooper C. Osteoporosis: impact on health and economics. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2010;6(2):99–105. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2009.260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lotters FJ, Lenoir-Wijnkoop I, Fardellone P, Rizzoli R, Rocher E, Poley MJ. Dairy foods and osteoporosis: an example of assessing the health-economic impact of food products. Osteoporos Int. 2013;24(1):139–150. doi: 10.1007/s00198-012-1998-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Office of the Surgeon General (US) Bone Health and Osteoporosis: A Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, MD: Office of the Surgeon General (US); 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Riggs BL, Melton LJ., 3rd The worldwide problem of osteoporosis: insights afforded by epidemiology. Bone. 1995;17(5 Suppl):505S–511S. doi: 10.1016/8756-3282(95)00258-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Prevention and management of osteoporosis. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser. 2003;921:1–164. back cover. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bonjour JP, Lecerf JM. Dairy micronutrients: new insights and health benefits. Introduction. J Am Coll Nutr. 2011;30(5) Suppl 1:399S. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2011.10719982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thorpe MP, Jacobson EH, Layman DK, He X, Kris-Etherton PM, Evans EM. A diet high in protein, dairy, and calcium attenuates bone loss over twelve months of weight loss and maintenance relative to a conventional high-carbohydrate diet in adults. J Nutr. 2008;138(6):1096–1100. doi: 10.1093/jn/138.6.1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moschonis G, Manios Y. Skeletal site-dependent response of bone mineral density and quantitative ultrasound parameters following a 12-month dietary intervention using dairy products fortified with calcium and vitamin D: the Postmenopausal Health Study. Br J Nutr. 2006;96(6):1140–1148. doi: 10.1017/bjn20061977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McCabe LD, Martin BR, McCabe GP, Johnston CC, Weaver CM, Peacock M. Dairy intakes affect bone density in the elderly. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;80(4):1066–1074. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/80.4.1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sahni S, Tucker KL, Kiel DP, Quach L, Casey VA, Hannan MT. Milk and yogurt consumption are linked with higher bone mineral density but not with hip fracture: the Framingham Offspring Study. Arch Osteoporos. 2013;8(1–2):119. doi: 10.1007/s11657-013-0119-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lunt M, Masaryk P, Scheidt-Nave C, et al. The effects of lifestyle, dietary dairy intake and diabetes on bone density and vertebral deformity prevalence: the EVOS study. Osteoporos Int. 2001;12(8):688–698. doi: 10.1007/s001980170069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Feskanich D, Willett WC, Colditz GA. Calcium, vitamin D, milk consumption, and hip fractures: a prospective study among postmenopausal women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;77(2):504–511. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/77.2.504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Feskanich D, Willett WC, Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA. Milk, dietary calcium, and bone fractures in women: a 12-year prospective study. Am J Public Health. 1997;87(6):992–997. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.6.992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Owusu W, Willett WC, Feskanich D, Ascherio A, Spiegelman D, Colditz GA. Calcium intake and the incidence of forearm and hip fractures among men. J Nutr. 1997;127(9):1782–1787. doi: 10.1093/jn/127.9.1782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bischoff-Ferrari HA, Dawson-Hughes B, Baron JA, et al. Milk intake and risk of hip fracture in men and women: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. J Bone Miner Res. 2011;26(4):833–839. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cheng S, Lyytikainen A, Kroger H, et al. Effects of calcium, dairy product, and vitamin D supplementation on bone mass accrual and body composition in 10–12-y-old girls: a 2-y randomized trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;82(5):1115–1126. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/82.5.1115. quiz 1147–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kalkwarf HJ, Khoury JC, Lanphear BP. Milk intake during childhood and adolescence, adult bone density, and osteoporotic fractures in US women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;77(1):257–265. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/77.1.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Teegarden D, Legowski P, Gunther CW, McCabe GP, Peacock M, Lyle RM. Dietary calcium intake protects women consuming oral contraceptives from spine and hip bone loss. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90(9):5127–5133. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-0924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Teegarden D, Lyle RM, Proulx WR, Johnston CC, Weaver CM. Previous milk consumption is associated with greater bone density in young women. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;69(5):1014–1017. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/69.5.1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dawber TR, Meadors GF, Moore FE., Jr Epidemiological approaches to heart disease: the Framingham Study. Am J Public Health Nations Health. 1951;41(3):279–281. doi: 10.2105/ajph.41.3.279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rimm EB, Giovannucci EL, Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, Litin LB, Willett WC. Reproducibility and validity of an expanded self-administered semiquantitative food frequency questionnaire among male health professionals. Am J Epidemiol. 1992;135(10):1114–1126. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116211. discussion 1127–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ascherio A, Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, Rimm EB, Litin L, Willett WC. Correlations of vitamin A and E intakes with the plasma concentrations of carotenoids and tocopherols among American men and women. J Nutr. 1992;122(9):1792–1801. doi: 10.1093/jn/122.9.1792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jacques PF, Sulsky SI, Sadowski JA, Phillips JC, Rush D, Willett WC. Comparison of micronutrient intake measured by a dietary questionnaire and biochemical indicators of micronutrient status. Am J Clin Nutr. 1993;57(2):182–189. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/57.2.182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Salvini S, Hunter DJ, Sampson L, et al. Food-based validation of a dietary questionnaire: the effects of week-to-week variation in food consumption. Int J Epidemiol. 1989;18(4):858–867. doi: 10.1093/ije/18.4.858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kiel DP, Felson DT, Anderson JJ, Wilson PW, Moskowitz MA. Hip fracture and the use of estrogens in postmenopausal women. The Framingham Study. N Engl J Med. 1987;317(19):1169–1174. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198711053171901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tucker KL, Chen H, Hannan MT, et al. Bone mineral density and dietary patterns in older adults: the Framingham Osteoporosis Study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2002;76(1):245–252. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/76.1.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cauley JA, Seeley DG, Ensrud K, Ettinger B, Black D, Cummings SR. Estrogen replacement therapy and fractures in older women. Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group. Ann Intern Med. 1995;122(1):9–16. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-122-1-199501010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Willett WC, Howe GR, Kushi LH. Adjustment for total energy intake in epidemiologic studies. Am J Clin Nutr. 1997;65(4 Suppl):1220S–1228S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/65.4.1220S. discussion 1229S–1231S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Willett W, Stampfer MJ. Total energy intake: implications for epidemiologic analyses. Am J Epidemiol. 1986;124(1):17–27. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chee WS, Suriah AR, Chan SP, Zaitun Y, Chan YM. The effect of milk supplementation on bone mineral density in postmenopausal Chinese women in Malaysia. Osteoporos Int. 2003;14(10):828–834. doi: 10.1007/s00198-003-1448-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Daly RM, Bass S, Nowson C. Long-term effects of calcium-vitamin-D3-fortified milk on bone geometry and strength in older men. Bone. 2006;39(4):946–953. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2006.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Daly RM, Brown M, Bass S, Kukuljan S, Nowson C. Calcium- and vitamin D3-fortified milk reduces bone loss at clinically relevant skeletal sites in older men: a 2-year randomized controleed trial. J Bone Miner Res. 2006;21(3):397–405. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.051206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dawson-Hughes B, Harris SS, Krall EA, Dallal GE. Effect of calcium and vitamin D supplementation on bone density in men and women 65 years of age or older. N Engl J Med. 1997;337(10):670–676. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199709043371003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hannan MT, Tucker KL, Dawson-Hughes B, Cupples LA, Felson DT, Kiel DP. Effect of dietary protein on bone loss in elderly men and women: the Framingham Osteoporosis Study. J Bone Miner Res. 2000;15(12):2504–2512. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2000.15.12.2504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kanis JA, Johansson H, Oden A, et al. A meta-analysis of milk intake and fracture risk: low utility for case finding. Osteoporos Int. 2005;16(7):799–804. doi: 10.1007/s00198-004-1755-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Feskanich D, Bischoff-Ferrari H, Frazier A, Willett W. Milk Consumption During Teenage Years and Risk of Hip Fractures in Older Adults. JAMA Pediatr. 2013 doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.3821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fujiwara S, Kasagi F, Yamada M, Kodama K. Risk factors for hip fracture in a Japanese cohort. J Bone Miner Res. 1997;12(7):998–1004. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1997.12.7.998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McCarron DA, Heaney RP. Estimated healthcare savings associated with adequate dairy food intake. Am J Hypertens. 2004;17(1):88–97. doi: 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2003.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]