Abstract

Purpose

Metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joint deformities caused by rheumatoid arthritis can be treated using silicone metacarpophalangeal joint arthroplasty (SMPA). There is no consensus whether this surgical procedure is beneficial. The purpose of the study was to prospectively compare outcomes for a surgical and a non-surgical cohort of rheumatoid arthritis patients.

Methods

The prospective cohort trial was conducted from January 2004 to May 2008 at 3 referral centers in the US and England. Over a 3 year period, 70 surgical and 93 nonsurgical patients were recruited. One year data are available for 45 cases and 72 controls. All patients had severe ulnar drift and/or extensor lag of the fingers at the MCP joints. The patients all had one year follow-up evaluations. Patients could elect to undergo SMPA and medical therapy or medical therapy alone. Outcomes included the Michigan Hand Outcomes Questionnaire (MHQ), Arthritis Impact Measurement Scales (AIMS2), grip/pinch strength, Jebson-Taylor test and ulnar deviation and extensor lag measurements at the MCP joints.

Results

There was no difference in the mean age for the surgical group (60) when compared to the non-surgical group (62). There was also no significant difference in race, education, and income between the two groups. At one year follow-up time, the mean overall MHQ score showed significant improvement in the surgical group, but no change in the non-surgical group, despite worse MHQ function at baseline in the surgical group. Ulnar deviation and extensor lag improved significantly in the surgical group, but the mean AIMS2 scores and grip/pinch strength showed no significant improvement.

Conclusion

This clinical trial demonstrated significant improvement for RA patients with poor baseline functioning treated with SMPA. The non-surgical group had better MHQ scores at baseline and their function did not deteriorate during the one year follow-up interval.

Keywords: Rheumatoid arthritis, Silicone Metacarpophalangeal Joint Arthroplasty, Clinical trial, The Michigan Hand Outcomes Questionnaire, Hand Surgery

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is the second most common type of arthritis after osteoarthritis.1 A recent report from the National Arthritis Data Workshop estimates that 1.3 million adults in the United States have been diagnosed with RA. This disease is more common in women by affecting 1.06% of women in comparison to 0.61% of men in the United States.2

RA is a progressive and often crippling disease, which is responsible for lost work and wages as well as a decline in the quality of life for many patients. It has been estimated that 70% of RA patients have some type of hand impairment.3 These hand impairments hamper the ability of RA patients to perform activities of daily living (ADL) and in severe cases, live independently. Hand deterioration can occur quite rapidly. Dellhag and Bjelle monitored RA patients over a 5 year period and found that hand function worsened significantly during this time.4 Sherrer et al. found that by 10 years after diagnosis, 90% of RA patients had some measurable disability in ADL and 13% were nearly completely disabled.5 In the US, the costs associated with RA, including medical costs and lost wages, were estimated at $8.7 billion annually in 1996.6

A common deformity in RA patients is the appearance of ulnar drift of the fingers and an inability of the fingers to extend (Figure 1). RA patients experience functional limitations due to difficulty with grasping, fine pinch and holding large objects. Since the introduction of the silicone metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joint arthroplasty (SMPA) to realign fingers over 40 years ago, a number of retrospective uncontrolled studies have been published that demonstrate the effectiveness of this operation in improving the appearance and posture of the hand.7-15 Recently, more prospective outcome studies (sample sizes ranging from 12 to 21) with 1 year follow-up have shown that the SMPA procedure is highly effective in correcting ulnar drift and improving health-related quality-of-life (HRQL), but hand function, as measured by arc of motion and grip strength, does not improve after surgery.16-19

Figure 1.

Example of deformities in rheumatoid hand and results following SMPA. The right unoperated hand shows the ulnar drift and extension lag of the fingers due to disease at the MCP joints. The left hand was corrected by SMPA.

One problem in determining appropriate care for RA patients is the considerable disagreement between rheumatologists and hand surgeons regarding timing, indications, and outcomes of RA hand surgery.20-23 The care of RA patients is marked by large area variations between regions of the United States.20 These large variations are reflected in a national survey of rheumatologists and hand surgeons that showed that a minority of rheumatologists (34%) and a majority of hand surgeons (83%) had a positive view regarding outcomes of SMPA procedures.23 In addition, rheumatologists indicated that this procedure should be reserved for patients with more severe deformity, whereas hand surgeons prefer to operate on patients earlier when they have less deformity. One of the main reasons for this disagreement is that outcomes data on RA hand surgery is often viewed by rheumatologists as unscientific and less than robust. These interdisciplinary controversies may be hampering care of RA patients and highlight the viewpoint of hand surgeons that RA patients with hand deformities are not referred sufficiently often for surgical consideration or are referred at a late stage.3, 23

To address the ongoing debate regarding the SMPA procedure, we have initiated a three center international prospective cohort study as a collaborative effort between rheumatologists and hand surgeons to evaluate outcomes of SMPA procedures comparing patients treated with or without surgical intervention. Rheumatologists and hand surgeons worked jointly to recruit patients into the study and to assess the outcomes and complications associated with this commonly performed procedure. The specific aim of this study is to measure patient outcomes using functional and validated patient-rated outcomes questionnaires in an effort to assess the effects of SMPA on hand function and overall health-related quality-of-life. We hypothesize that RA patients who undergo SMPA will have clinically and statistically significant improvements as measured by the Michigan Hand Outcomes Questionnaire compared to non-SMPA patients.

Materials and Methods

Objectives

The objective of the study was to evaluate a prospective cohort of RA patients with MCP joint subluxation who elect to undergo SMPA or not undergo SMPA. Outcome measurements included a hand-specific instrument, the Michigan Hand Outcomes Questionnaire (MHQ) andthree quantitative hand function tests (grip strength, pinch strength, and Jebsen-Taylor test). We also compared the global functioning of the surgical and non-surgical groups by using an arthritis specific instrument, the Arthritis Impact Measurement Scales (AIMS2).

Eligibility criteria

Study subjects were recruited from three sites: The University of Michigan (Ann Arbor, MI), Curtis National Hand Center (Baltimore, MD) and Pulvertaft Hand Centre (Derby, England). All aspects of the study were approved by the Institutional Review Boards at the University of Michigan, Curtis National Hand Center and the Pulvertaft Hand Centre. Patients diagnosed with RA were referred by their rheumatologists to one of the three centers. Patients were eligible to participate in the study if they had a diagnosis of RA, were 18 years of age or older and had the ability to complete questionnaires in English. Additionally, patients were eligible to participate in the study if the sum of the average MCP joint ulnar drift and average MCP joint extensor lag was equal to or greater than 50. For example, the ulnar deviation and extensor lag of the index, middle, ring and small fingers were summed and then averaged. The sum of the two averages (ulnar deviation and extensor lag) must equal 50° or more. This threshold of MCP joint subluxation was determined by an expert panel of rheumatologists and hand surgeons to be the minimal deformity that would warrant surgical consideration for reconstruction. Exclusion criteria included: health problems that would prohibit surgery, extensor tendon ruptures in the study hand (which require a different therapy protocol), swan-neck or boutonniere deformities that would require surgery (which confounds the outcomes because of additional surgical procedures on the hand), previous MCP joint replacement and the initiation of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) within 3 months of enrollment (which may increase surgical infection risk).

Treatment allocation

The study design was a prospective cohort clinical trial with two treatment groups: SMPA surgery or no surgery. Because of strong patient preference, we could not randomize patients into the treatment groups. We found in the planning phase of this study that most patients would not consent to randomization because they had an inherent preference whether to have or not have surgery. In addition, most RA hand deformities are not perfectly symmetrical and patients frequently have a preference regarding the hand on which they want to have surgery first. For this reason, in this study, the surgical subjects could choose which hand would have surgery. Similarly, non-surgical subjects could choose which (hypothetical) hand would be the study hand, if they would have elected to have an operation. During the study, changes in the medical management of each patient were at the discretion of the patients’ rheumatologists.

Patients met with the occupational therapist prior to surgery to discuss the procedure and what to expect regarding therapy and rehabilitation time post-operatively. The occupational therapist explained that they would begin wearing a dynamic MCP joint extension splint five days after surgery. The tension of the dynamic splint is set to maintain full MCP joint extension at rest and allow maximal active MCP joint flexion. The extension dynamic splint is worn at all times for six weeks. After six weeks, dynamic extension splint is worn in the evenings only. The patients can start engaging in “light duty” hand activities during the day. At 12 weeks, splinting is discontinued, and patients resume unrestricted activity

Outcome Measures

All outcome measures were completed at each of the study intervals: enrollment, 6 months, 1 year, 2 years, and 3 years. This paper will present the one year follow-up data. The patients are still being followed and the sample sizes for the 2 and 3 year cohort are as yet too small for analysis.

Study Questionnaires

The primary outcome instrument for measuring hand performance in this study is the MHQ.24, 25 The MHQ is a validated hand-specific outcome questionnaire and has been utilized in researching outcomes for RA,19, 26, 27 carpal tunnel syndrome, 28, 29 distal radius fractures,30-32 Dupuytren’s disease,33 and microvascular toe transfer.34, 35 The MHQ contains six domains: (1) overall hand function, (2) ADL, (3) pain, (4) work performance, (5) aesthetics, and (6) patient satisfaction. Scores range from 0 to 100 with higher scores indicating better performance, except for the pain scale. For the pain scale, a higher score indicated more pain.

Study subjects also completed the Arthritis Impact Measurement Scales 2 (AIMS2).36 The AIMS2 is a health status questionnaire specifically designed to measure health status in RA patients. The AIMS2 contains 12 scales, which can be combined into four domains: 1) physical, 2) affect, 3) symptom, and 4) social interaction. AIMS2 scores range from 1 to 10 with lower scores indicating better health status.

Functional Assessment

Functional assessments included: grip strength, lateral pinch, two-point pinch and three-point pinch. The Jebson-Taylor test was also administered at each study visit.37 It is a test that simulates ADL and consists of seven components: (1) writing a short sentence, (2) turning over 3 by 5 inch cards, (3) picking up small objects and placing them in a container, (4) stacking checkers, (5) simulated eating, (6) moving large, empty cans, and (7) moving large, weighted cans. Because of the difficulty in interpreting the writing portion, this section of the test was omitted. The time required in seconds to complete each task is recorded for the subjects’ dominant and non-dominant hands.

Data Analysis

Because study subjects agreed not to cross over to the other treatment group before the one year follow-up period, the effect of cross-over is not an issue in this current analysis. We first compared the distribution of demographic variables and baseline factors between the surgical group and the non-surgical group. Baseline analysis included descriptive statistics to describe the distribution of baseline variables in the two study groups. To compare the distribution of baseline variables between the two study groups, we apply the two-sample t-test for continuous variables, and chi-square tests for categorical variables.

For all outcome measures of interest, means and 95% confidence intervals at each follow-up time were calculated for the two groups. Differences in the average mean change-scores at one year from baseline were calculated as effect sizes for the surgical group compared with non-surgical group. Multiple regression models were used to obtain the covariate adjusted effect sizes and to test for the statistical difference in the one year change-scores between the two groups. The model used the change-scores as the dependent variable and an indicator for the surgical group as the primary independent variable. To adjust the effect sizes for baseline differences, the models were also adjusted for two different sets of covariates. In the first case, the mean difference in the change-scores was adjusted for the baseline values of the response variable. In the second case, the mean difference in the change-scores was adjusted for the baseline value of the response variable, age, severity (as degree of deformity), education (high school and lower versus higher), and gender. All effect sizes were calculated so the positive values corresponded to greater improvement in the surgical group relative to non-surgical group. Assessments of longitudinal trends were done graphically with the means and the 95% confidence intervals at each follow-up plotted over time for the two groups.

Results

A total of 163 patients were enrolled in the study from January 2004 to May 2008. Four patients assessed for eligibility declined to participate in the study. This is the largest cohort thus far assembled to evaluate the effects of the SMPA procedure. Of these patients, 70 were surgical cases and 93 were non-surgical cases. The study was designed as a long-term comparative hand outcomes study to have 90% power to detect a 0.6 standardized effect size (as changes from baseline in hand-specific outcomes at one year) between the surgical and non-surgical groups using a two-sided 0.01 level two-sample t-test. We report here preliminary results from one year outcome data available for 45 cases and 72 controls. Table 1 compares the demographic data for the surgical and non-surgical groups. The two groups were found to be statistically comparable in age, race, income and education though more women elected to have surgery.

Table 1. Comparison of Demographic Values for Surgical vs. Non-Surgical Subjects.

| Demographic variables | Surgery (N=70) |

Non-surgical (N=93) |

P- value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 60 (8) | 62 (11 ) | 0.33 |

| Women, No. (%) | 57 (81) | 62 (67) | 0.04 |

| Race, White, No. (%) | 59 (84) | 76 (82) | 0.10 |

| Education, ≤ High School Degree, No. (%) |

36 (51) | 37 (40) | 0.11 |

| Income, ≤ $50,000, No. (%) | 49 (70) | 58 (62) | 0.42 |

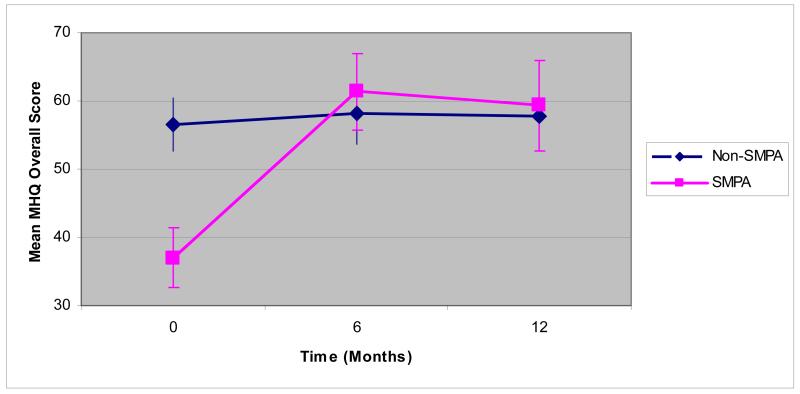

Tables 2-5 show outcomes at baseline, 6 months and 1 year for surgical and non-surgical cases. Mean MHQ scores (Table 2 and Figure 2) for the surgical group are lower at baseline than in the non-surgical group for all domains (p < 0.01 for all domains) indicating more patients in the surgical cohort have more self-perceived functional impairment in their hands and worse hand outcomes in general. The MHQ scores for the surgical cohort increased substantially at 6 months and approached or surpassed the scores for the non-surgical group at 1 year. The adjusted effect sizes at 1 year were significantly greater than zero for all MHQ subscales and the overall scale, indicating significant improvement in the surgical group. The exception to this trend is the MHQ work subscale. MHQ scores in the non-surgical group did not change significantly for any of the scales from baseline to 1 year.

Table 2. Comparison of Michigan Hand Outcomes Questionnaire (MHQ) Scores for Surgical (SMPA) vs. Non-Surgical Subjects.

| MHQ Scale | Preoperative | 6-Month Postoperative |

1-Year Postoperative |

Adjusted Effect Size* (Baseline) |

Adjusted Effect Size** (Baseline & Covariates) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SMPA | Non- SMPA |

SMPA | Non- SMPA |

SMPA | Non- SMPA |

Effect Size | p-value | Effect Size | p-value | |

| Function | 36 (22) | 58 (18) | 64 (19) | 59 (21) | 60 (24) | 59 (22) | 15.4 | <.001 | 14.4 | 0.001 |

| ADL | 34 (26) | 60 (24) | 55 (29) | 60 (26) | 55 (31) | 60 (25) | 13.3 | <.001 | 13.2 | 0.001 |

| Work | 41 (22) | 59 (23) | 50 (28) | 63 (28) | 47 (28) | 61 (26) | 0.1 | 0.981 | 1.3 | 0.774 |

| Pain ♣ | 49 (26) | 35 (25) | 35 (25) | 33 (26) | 34 (24) | 35 (26) | 8.3 | 0.033 | 8.2 | 0.063 |

| Aesthetics | 32 (22) | 48 (24) | 71 (22) | 50 (23) | 66 (23) | 52 (23) | 20.5 | <.001 | 21.4 | <.001 |

| Satisfaction | 26 (20) | 48 (25) | 64 (24) | 49 (26) | 61 (27) | 49 (26) | 26.1 | <.001 | 24.1 | <.001 |

| Overall Score | 37 (18) | 56 (18) | 61 (20) | 58 (21) | 59 (22) | 58 (20) | 16.3 | <.001 | 15.6 | <.001 |

Abbreviations: ADL, activities of daily living; SMPA, Silicone Metacarpophalangeal Joint Arthroplasty.

Cell values are means (SD).

Mean difference in the response variable (1 year change score) between the SMPA and Non-SMPA group, adjusting for the centered baseline values of the response variable.

Mean difference in the response variable (1 year change score) between the SMPA and Non-SMPA group, adjusting for the centered baseline value of the response variable, centered age, centered severity, education (high school and lower versus higher), and gender.

Higher pain scores correspond to greater pain.

Table 5.

Angle of Motion Scores for Surgical vs. Non-Surgical Subjects

| Angle of Motion scores♣ |

Preoperative | 6-Month Postoperative |

1-Year Postoperative |

Adjusted Effect Size* (Baseline) |

Adjusted Effect Size** (Baseline & Covariates) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SMPA | Non- SMPA |

SMPA | Non- SMPA |

SMPA | Non- SMPA |

Effect Size | p-value | Effect Size | p-value | |

| Ulnar Drift | 37 (16) | 34 (14) | 13 (12) | 30 (14) | 13 (11) | 34 (14) | 21.27 | <.001 | 23.70 | <.001 |

| Extensor Lag | 65 (23) | 47 (18) | 26 (15) | 46 (23) | 29 (14) | 49 (21) | 28.10 | <.001 | 30.07 | <.001 |

|

MCP joint arc of

motion |

19 (15) | 37 (18) | 32 (17) | 37 (21) | 31 (15) | 34 (17) | 5.90 | 0.068 | 7.61 | 0.032 |

Abbreviations: MCP, Metacarpophalangeal; SMPA, Silicone Metacarpophalangeal Joint Arthroplasty.

Cell values are means (SD).

Mean difference in the response variable (1 year change score) between the SMPA and control group, adjusting for the centered baseline values of the response variable.

Mean difference in the response variable (1 year change score) between the SMPA and Non-SMPA group, adjusting for the centered baseline value of the response variable, centered age, centered severity, education (high school and lower versus higher), and gender.

Higher values correspond to worse outcome.

Figure 2.

Mean MHQ Overall Score for Surgical and Non-surgical Subjects Over Time (months)

Physical measurements (Table 3) did not show the same level of improvement as seen with the MHQ data. All physical measurements reflected statistically significant worse function (p < 0.05) at baseline in the surgical group compared to the non-surgical group, except key lateral pinch (p = 0.10). For most functional outcomes, the outcomes in the surgical group worsened at 6 months and improved to baseline values at 1 year. None of the adjusted effect sizes was significant. Although the Jebson-Taylor test did show improvement at 1 year from baseline in the surgical subjects by decreasing the time to complete tasks from 55.8 seconds at baseline to 44.4 seconds at 1 year, the baseline-adjusted effect size was not significant at one year.

Table 3. Comparison of Physical Measurement Scores for Surgical vs. Non-Surgical Subjects.

| Physical Measures | Preoperative | 6-Month Postoperative |

1-Year Postoperative |

Adjusted Effect Size* (Baseline) |

Adjusted Effect Size** (Baseline & Covariates) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SMPA | Non- SMPA |

SMPA | Non- SMPA |

SMPA | Non- SMPA |

Effect Size |

p-value | Effect Size |

p-value | |

| Grip Strength (kg) | 5.7 (6) | 8.5 (7) | 4.6 (4) | 9.6 (8) | 6.2 (5) | 9.8 (8) | −1.28 | 0.140 | −1.46 | 0.132 |

|

Key (lateral) pinch

(kg) |

3.5 (2) | 4.0 (2) | 3.1 (2) | 4.2 (2) | 3.1 (2) | 4.0 (2) | −0.25 | 0.268 | −0.25 | 0.327 |

|

2-point (tip) pinch

(kg) |

2.5(2) | 3.1 (2) | 2.3 (1) | 3.1 (2) | 2.7 (2) | 3.1 (2) | 0.08 | 0.683 | 0.12 | 0.603 |

|

Three-jaw

(palmar) pinch (kg) |

2.6 (2) | 3.1 (1) | 2.4 (1) | 3.2 (2) | 2.5 (1) | 3.1 (1) | 0.02 | 0.934 | −0.02 | 0.914 |

| Jebson-Taylor (s) ♣ | 56 (27) | 43 (10) | 48 (19) | 40 (11) | 44 (16) | 40 (10) | 1.75 | 0.359 | 1.69 | 0.440 |

Abbreviations: SMPA, Silicone Metacarpophalangeal Joint Arthroplasty.

Cell values are means (SD).

Mean difference in the response variable (1 year change score) between the SMPA and Non-SMPA group, adjusting for the centered baseline values of the response variable.

Mean difference in the response variable (1 year change score) between the SMPA and Non-SMPA group, adjusting for the centered baseline value of the response variable, centered age, centered severity, education (high school and lower versus higher), and gender.

Higher Jebson-Taylor scores correspond to worse outcome.

AIMS2 outcome data (Table 4) showed the greatest improvement in the physical domain for surgical patients and minimal improvement for the affect, symptom and social interaction domains. Surgical scores for all AIMS domain were significantly higher (worse outcome) at baseline as compared to controls (p < 0.01for all domains, except p = 0.04 for social interaction) and remained higher at 6 months and 1 year. AIMS2 scores for non-surgical patients did not show any improvement and remained essentially the same from baseline to 1 year. None of the adjusted effect sizes was significant.

Table 4. Comparison of Arthritis Impact Measurement Scales 2 (AIMS2) Scores for Surgical vs. Non-Surgical Subjects.

| AIMS2 Scale♣ | Preoperative | 6-Month Postoperative |

1-Year Postoperative |

Adjusted Effect Size* (Baseline) |

Adjusted Effect Size** (Baseline & Covariates) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SMPA | Non- SMPA |

SMPA | Non- SMPA |

SMPA | Non- SMPA |

Effect Size |

p-value | Effect Size |

p-value | |

| Physical | 4.0 (2) | 2.4 (2) | 3.4 (2) | 2.5 (2) | 3.3 (2) | 2.4 (2) | 0.24 | 0.261 | 0.28 | 0.241 |

| Affect | 4.1 (2) | 3.0 (2) | 3.7 (2) | 2.7 (2) | 3.7 (2) | 2.7 (2) | 0.03 | 0.895 | 0.23 | 0.343 |

| Symptom | 5.6 (3) | 4.3 (2) | 5.1 (3) | 4.0 (3) | 4.8 (3) | 4.0 (3) | 0.30 | 0.367 | 0.14 | 0.716 |

| Social interaction | 4.2 (2) | 3.6 (1) | 3.9 (2) | 3.7 (1) | 3.9 (2) | 3.5 (1) | 0.10 | 0.637 | 0.20 | 0.397 |

Abbreviations: SMPA, Silicone Metacarpophalangeal Joint Arthroplasty.

Cell values are means (SD).

Mean difference in the response variable (1 year change score) between the SMPA and Non-SMPA group, adjusting for the centered baseline values of the response variable.

Mean difference in the response variable (1 year change score) between the SMPA and Non-SMPA group, adjusting for the centered baseline value of the response variable, centered age, centered severity, education (high school and lower versus higher), and gender.

For all AIMS2 subscales, higher scores correspond to worse outcome.

In contrast to other measurements, the mean degree of ulnar drift for the two treatment groups was similar (p = 0.23) at baseline (Table 5). However, the surgical cases showed remarkable improvement in ulnar drift at 6 months and 1 year. Extensor lag was greater (p < 0.001) at baseline for surgical cases as compared to non-surgical cases, but was substantially lower than non-surgical cases at 6 months and 1 year. The arc of motion is defined as the flexion – extension lag at a particular joint. The arc of motion for the MCP joint was lower (p < 0.001) for surgical cases at baseline as compared to non-surgical cases, with the greatest increase for the surgical group at 6 months and a smaller increase at 1 year. Mean scores for non-surgical group for all three measurements did not change from baseline to 1 year. The changes from baseline in ulnar drift and extensor lag were significantly greater in the surgical group than in the non-surgical group both at 6 months and at 1 year.

Adverse Effects

One patient had a K-wire infection from a PIP joint fusion. Two patients required revision SMPA. One patient because of substantial ulnar drift post-operatively and another patient because of a dislocated right little finger implant.

Discussion

The outcomes movement began in the late 1980’s as a response to the rising cost of health care.38 The medical community, if it was going to succeed in containing costs, needed to determine whether medical services given resulted in improved patient outcomes. The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) was created by Congress to identify research that would directly improve patient outcomes, result in changes in clinical practice and lead to the development of guidelines for the appropriate use of medical services.39, 40 As a means of evaluating outcomes research, AHRQ developed a model to determine the level of impact.41 A level 1 study has the lowest level of impact and does not provide enough evidence to change policy or clinical practice. Level 4 studies have the highest level of impact and show an improvement in health outcomes as a direct result of a medical intervention. Level 4 studies must have a control group and are usually clinical trials. Although the outcomes movement is several decades old, the number of level 4 studies published is inadequate in many medical fields, particularly in hand surgery.42, 43

Clinical trials are used routinely to test the effectiveness of medical treatments for RA. A large body of evidence has been accumulated about a variety of drugs that can be used in the management of this disease.44-46 Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), corticosteroids, disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) and analgesics have been used for many years. Although they often do not stop the progression of the disease, these drugs are very helpful in reducing the symptoms of RA, including inflammation and pain. New biologic agents have emerged that may actually prevent joint destruction altogether and have substantially changed the management of RA.

In contrast to rigorous research programs to test new drug in the treatment of RA, high level evidence studies to evaluate surgical innovations for this disease are lacking. Previous studies have been mostly retrospective chart reviews with no control group, and none included validated outcomes questionnaires.14 Given the current state of surgical research in RA, it is not surprising that rheumatologists view surgical outcomes studies with skepticism, and thus the controversy regarding SMPA persists. The aim of this study is to provide outcomes data regarding the benefits of SMPA by evaluating a prospective cohort of RA patients. Recruitment of patients from three different practice settings enhances generalizability. The University of Michigan is a tertiary referral academic center with a large collaborative program in the care of the RA patients, the Curtis National Hand Center draws patients from around the United States for hand surgery expertise, and the Pulvertaft Hand Center in Derbyshire, England is a renowned center in the United Kingdom for RA treatment.

This clinical trial involved recruitment of a cohort of RA patients with defined MCP joint deformities who entered a surgery plus medical therapy group or a medical therapy alone group. Although the surgical group had worse self-reported MHQ scores at baseline when compared to the non-surgical group, the outcomes at 1 year follow-up period showed significant improvement in hand function after SMPA. Surgical patients reported significant improvement in function, aesthetics, ADL and satisfaction with their hand 1 year after surgery. Surgical cases also had significant decreases in ulnar drift and extensor lag after reconstruction. Overall health as measured by the AIMS2 questionnaire did not show any improvement at 1 year. AIMS2 has construct validity in measuring the general health impairment in RA, and our study showed that general RA health cannot be improved simply with hand reconstruction alone. The change in values for grip strength and pinch strength were not significant. These results are consistent with previous studies that show improvement in ulnar drift, extensor lag and HRQL after surgery but no improvement in the other standard functional measures.14, 19, 47

In contrast, the non-surgical group showed no improvement or deterioration in hand function during 1 year follow-up. Overall, the non-surgical group began the study with better function as measured using outcomes questionnaires and functional tests. This result is not surprising because one would expect that patients who report better hand function would not elect to have surgery. This group is continuing with medical therapy and the lack of deterioration in hand function provides evidence of the effectiveness of RA medications in curbing the destructive effect of RA.

This study did not randomize subjects into treatments groups due to strong patient preference and issues with equipoise by participating surgeons and rheumatologists. But despite a non-randomized design, both groups had similar baseline data in age, race, education, and income. Our surgical group had more women and we adjusted for gender as well as age and education in the analysis. Baseline values for most of the outcomes were different for the two treatment groups. Patients with poorer self-reported hand function at baseline elected to have surgery. Although the mean values of the outcome variable for the two treatment groups differed at baseline, the distributions of the two groups had a good overlap. We computed the effect sizes, adjusting for baseline values of the outcome variable.

The results presented in this paper only include up to 1 year of follow-up. Long term retrospective studies of SMPA have demonstrated high rates of implant fractures but patient satisfaction with the procedure remains good.8, 9, 15 We are continuing to follow this important cohort of patients and will be able to determine if improvements in hand outcomes for SMPA patients are maintained or if either group shows worsening over time. The results demonstrate that SMPA is a good treatment option, especially for patients with poor hand function and in whom medical therapy alone has not alleviated symptoms and slowed the progression of the disease. The information obtained in this study will help to bridge the gap between rheumatologists and hand surgeons in the common goal of improving the quality of life for patients with RA.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the assistance of the following participants of the SMPA Study Group: Sandra V. Kotsis, MPH, Heidi Reichert, MA (University of Michigan), Lorraine A. Zellers, CRC (Curtis National Hand Center), Mary J. Bradley, MSc (Pulvertaft Hand Centre) and the referring rheumatologists in Michigan, Derby and Baltimore. The authors also greatly appreciate the assistance of Jeanne M. Riggs, OTR, CHT, Kurt Hiser, OTR, Carole Dodge, OTR, CHT, Jennifer Stowers, OTR, CHT, Cheryl Showerman, OTR, Jo Holmes, OTR, Victoria Jansen, PT and Helen Dear, OTR in taking measurements for the study patients.

Supported in part by a grant from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (R01 AR047328) and a Midcareer Investigator Award in Patient-Oriented Research (K24 AR053120) (to Dr. Kevin C. Chung).

References

- 1.Kelsey JL, Praemer A, Nelson L, Felberg A, Rice DP. Upper extremity disorders: frequency, impact and cost. Churchill Livingstone; New York: 1997. p. 17. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Helmick CG, Felson DT, Lawrence RC, Gabriel S, Hirsch R, Kwoh CK, et al. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the United States. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:15–25. doi: 10.1002/art.23177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.De la Mata Llord J, Palacios Carvajal J. Rheumatoid arthritis: are outcomes better with medical or surgical management? Orthop. 1998;21:1085–6. doi: 10.3928/0147-7447-19981001-06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dellhag B, Bjelle A. A five-year followup of hand function and activities of daily living in rheumatoid arthritis patients. Arthritis Care Res. 1999;12:33–41. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199902)12:1<33::aid-art6>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sherrer YS, Bloch DA, Mitchell DM, Young DY, Fries JF. The development of disability in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1986;29:494–500. doi: 10.1002/art.1780290406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yelin E. The costs of rheumatoid arthritis: absolute, incremental, and marginal estimates. J Rheumatol. 1996;44S:47–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mannerfelt L, Andersson K. Silastic arthroplasty of the metacarpophalangeal joints in rheumatoid arthritis. J Bone Joint Surg. 1975;57A:484–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beckenbaugh RD, Dobyns JH, Linscheid RL, Bryan RS. Review and analysis of silicone-rubber metacarpophalangeal implants. J Bone Joint Surg. 1976;58A:483–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blair WF, Shurr DG, Buckwalter JA. Metacarpophalangeal joint implant arthroplasty with a Silastic spacer. J Bone Joint Surg. 1984;66A:365–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Swanson AB. Flexible implant arthroplasty for arthritic finger joints: rationale, technique, and results of treatment. J Bone Joint Surg. 1972;54A:435–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fleming SG, Hay EL. Metacarpophalangeal joint arthroplasty eleven year follow-up study. J Hand Surg. 1984;9B:300–2. doi: 10.1016/0266-7681(84)90047-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bieber EJ, Weiland AJ, Volenec-Dowling S. Silicone-rubber implant arthroplasty of the metacarpophalangeal joints for rheumatoid arthritis. J Bone Joint Surg. 1986;68A:206–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vahvanen V, Viljakka T. Silicone rubber implant arthroplasty of the metacarpophalangeal joint in rheumatoid arthritis: a follow-up study of 32 patients. J Hand Surg. 1986;11A:333–9. doi: 10.1016/s0363-5023(86)80138-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chung KC, Kowalski CP, Kim HM, Kazmers IS. Patient outcomes following Swanson silastic metacarpophalangeal joint arthroplasty in the rheumatoid hand: a systematic overview. J Rheumatol. 2000;27:1395–402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goldfarb CA, Stern PJ. Metacarpophalangeal joint arthroplasty in rheumatoid arthritis. J Bone Joint Surg. 2003;85A:1869–78. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200310000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sollerman CJ, Geijer M. Polyurethane versus silicone for endoprosthetic replacement of the metacarpophalangeal joints in rheumatoid arthritis. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg Hand Surg. 1996;30:145–50. doi: 10.3109/02844319609056397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rothwell AG, Cragg KJ, O’Neill LB. Hand function following Silastic arthroplasty of the metacarpophalangeal joints in the rheumatoid hand. J Hand Surg. 1997;22B:90–3. doi: 10.1016/s0266-7681(97)80027-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McArthur PA, Milner RH. A prospective randomized comparison of Sutter and Swanson silastic spacers. J Hand Surg. 1998;23B:574–7. doi: 10.1016/s0266-7681(98)80004-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chung KC, Kotsis SV, Kim HM. A prospective outcomes study of Swanson metacarpophalangeal joint arthroplasty for the rheumatoid hand. J Hand Surg. 2004;29A:646–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2004.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alderman AK, Chung KC, DeMonner S, Spilson SV, Hayward RA. Large area variations in the surgical management of the rheumatoid hand. Surg Forum. 2001;LII:479–81. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alderman AK, Chung KC, Demonner S, Spilson SV, Hayward RA. The rheumatoid hand: a predictable disease with unpredictable surgical practice patterns. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;47:537–42. doi: 10.1002/art.10662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alderman AK, Chung KC, Kim HM, Fox DA, Ubel PA. Effectiveness of rheumatoid hand surgery: contrasting perceptions of hand surgeons and rheumatologists. J Hand Surg. 2003;28A:3–11. doi: 10.1053/jhsu.2003.50034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alderman AK, Ubel PA, Kim HM, Fox DA, Chung KC. Surgical management of the rheumatoid hand: consensus and controversy among rheumatologists and hand surgeons. J Rheumatol. 2003;30:1464–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chung KC, Pillsbury MS, Walters MR, Hayward RA. Reliability and validity testing of the Michigan Hand Outcomes Questionnaire. J Hand Surg. 1998;23A:575–87. doi: 10.1016/S0363-5023(98)80042-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chung KC, Hamill JB, Walters MR, Hayward RA. The Michigan Hand Outcomes Questionnaire (MHQ): assessment of responsiveness to clinical change. Ann Plast Surg. 1999;42:619–22. doi: 10.1097/00000637-199906000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alderman AK, Arora AS, Kuhn L, Wei Y, Chung KC. An analysis of women’s and men’s surgical priorities and willingness to have rheumatoid hand surgery. J Hand Surg. 2006;31A:1447–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2006.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chung KC, Kotsis SV, Kim HM, Burke FD, Wilgis EF. Reasons why rheumatoid arthritis patients seek surgical treatment for hand deformities. J Hand Surg. 2006;31A:289–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2005.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Klein RD, Kotsis SV, Chung KC. Open carpal tunnel release using a 1-centimeter incision: technique and outcomes for 104 patients. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;111:1616–22. doi: 10.1097/01.PRS.0000057970.87632.7e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kotsis SV, Chung KC. Responsiveness of the Michigan Hand Outcomes Questionnaire and the Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand questionnaire in carpal tunnel surgery. J Hand Surg. 2005;30A:81–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2004.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kotsis SV, Lau FH, Chung KC. Responsiveness of the Michigan Hand Outcomes Questionnaire and physical measurements in outcome studies of distal radius fracture treatment. J Hand Surg. 2007;32A:84–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2006.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chung KC, Kotsis SV, Kim HM. Predictors of functional outcomes after surgical treatment of distal radius fractures. J Hand Surg. 2007;32A:76–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2006.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chung KC, Petruska E. Treatment of unstable distal radius fractures with the volar locking plating system. A surgical technique. J Bone Joint Surg. 2007;89A:256–66. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.G.00283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Herweijer H, Dijkstra PU, Nicolai JP, Van der Sluis CK. Postoperative hand therapy in Dupuytren’s disease. Disabil Rehabil. 2007;29:1736–41. doi: 10.1080/09638280601125106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chung KC, Kotsis SV. Outcomes of multiple microvascular toe transfers for reconstruction in 2 patients with digitless hands: 2- and 4-year follow-up case reports. J Hand Surg. 2002;27A:652–8. doi: 10.1053/jhsu.2002.33706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chung KC, Wei FC. An outcome study of thumb reconstruction using microvascular toe transfer. J Hand Surg. 2000;25A:651–8. doi: 10.1053/jhsu.2000.6913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Meenan RF, Mason JH, Anderson JJ, Guccione AA, Kazis LE. AIMS2: the content and properties of a revised and expanded arthritis impact measurement scales health status questionnaire. Arthritis Rheum. 1992;35:1–10. doi: 10.1002/art.1780350102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sharma S, Schumacher HRJ, McLellan AT. Evaluation of the Jebsen hand function test for use in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res. 1994;7:16–9. doi: 10.1002/art.1790070105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Relman AS. Assessment and accountability: the third revolution in medical care. N Engl J Med. 1988;319:1220–2. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198811033191810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Epstein AM. The outcomes movement--will it get us where we want to go? N Engl J Med. 1990;323:266–70. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199007263230410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Eisenberg JM. Putting research to work: reporting and enhancing the impact of health services research. Health Serv Res. 2001;36:x–xvii. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.The outcome of outcomes research at AHCPR: final report. Rockville, MD: [Accessed 7/30/2008]. 1999. http://www.ahrq.gov/clinic/out2res Agency for Health Care Policy and Research (No. 99-R044) [Google Scholar]

- 42.Davis Sears E, Burns PB, Chung KC. The outcomes of outcome studies in plastic surgery: a systematic review of 17 years of plastic surgery research. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;120:2059–65. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000287385.91868.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chung KC, Burns PB, Davis Sears E. Outcomes research in hand surgery: where have we been and where should we go? J Hand Surg. 2006;31A:1373–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2006.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pisetsky DS, St Clair EW. Progress in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. JAMA. 2001;286:2787–90. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.22.2787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.O’Dell JR. Therapeutic strategies for rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2591–602. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra040226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Olsen NJ, Stein CM. New drugs for rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2167–79. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra032906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Burgess SD, Kono M, Stern PJ. Results of revision metacarpophalangeal joint surgery in rheumatoid patients following previous silicone arthroplasty. J Hand Surg [Am] 2007;32:1506–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2007.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]