Abstract

Objectives

Morphological abnormalities have been reported for the hippocampi and amygdalae in young schizophrenia patients, but very little is known about the pattern of abnormalities in elderly schizophrenia patients. Here we investigated local structural differences in the hippocampi and amygdalae of elderly schizophrenia patients compared to healthy elderly subjects. We also related these differences to clinical symptom severity.

Design

20 schizophrenia patients (mean age: 67.4±6.2 years, MMSE 22.8±4.4) and 20 healthy elderly subjects (70.3±7.5, 29.0±1.1) underwent high resolution magnetic resonance imaging of the brain. The Radial Atrophy Mapping technique was used to reconstruct the 3D shape of the amygdala and the hippocampus. Local differences in tissue reductions were computed between groups and permutation tests were run to correct for multiple comparisons, in statistical maps thresholded at p=0.05.

Results

Significant tissue reduction was observed bilaterally in the amygdala and hippocampus of schizophrenia patients. The basolateral-ventral-medial amygdalar nucleus showed the greatest involvement, with over 30% local tissue reduction. The centro-medial, cortical, and lateral nuclei were also atrophic in patients. The hippocampus showed significant tissue loss in the medio-caudal and antero-lateral aspects of CA1, and in medial section of its left head (pre- and para-subiculum;). In the left amygdala and hippocampus, local tissue volumes were significantly correlated with negative symptoms.

Conclusions

Tissue losses and altered morphology were found in elderly schizophrenia patients. Tissue loss mapped to amygdalo-hippocampal subregions known to have bidirectional and specific connections with frontal cortical and limbic structures and was related to clinical severity.

Keywords: elders, schizophrenia, amygdala, hippocampus, volumetric imaging, 3D-shape

Objective

Schizophrenia was first described by Kraepelin as a form of progressive neuronal degeneration characterized by an earlier onset than the other dementia-related disorders (1); the National Alliance on Mental Illness reports that about 1 in 100 young adults in the United States is affected by schizophrenia. This percentage represents about 3 million people nationwide. But schizophrenia is not only a young people disease, and the so called “schizophrenia in late life” is emerging as a major public health concern worldwide (2) (3). The number of older persons with a major psychiatric disorder has increased during last years. It has been estimated that by the year 2030, the number of persons over age 65 with a major psychiatric disorder will be roughly equal to the number of people aged 30 to 44 with a similar disorder (4). The hippocampus and amygdala are two allocortical key regions, highly interconnected and involved in various cognitive and behavioural functions (5). The hippocampus subserves the processing of episodic memory (6), and the amygdala is involved in appraising external stimuli with regard to their emotional significance (7). Volume deficits in both brain regions has been documented in a variety of brain disorders, including schizophrenia (8). Progressive hippocampal and amygdalar tissue loss may occur in the course of the disease, and may reflect abnormal plasticity and neurodegeneration (9), although the contributing mechanisms are not widely agreed and the same etiology may not be found in all patients (10–11). Early case-control MRI studies of schizophrenia patients have reported structural differences including reduced volume of medial temporal lobe structures, mainly located in the hippocampus and amygdale (see (12) for a review). Scientific literature reports encouraging results regarding neuroimaging profiles of young and elderly schizophrenia patients. The hippocampal involvement in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia has been described in neuroanatomical (13), neuropsychological (14), clinical (15) and postmortem studies suggesting loss of temporolimbic tissue both in adult and elderly schizophrenia patients (16).

Recently, Frisoni and colleagues (17) also showed atrophy of the whole cortical mantle in people with schizophrenia, while Thompson and colleagues found dynamic wave of accelerated gray matter loss in adolescent brains (18) which seemed also to be dependent on the type of used antipsychotic treatment (10).

In addition, we previously (9) examined MRI hippocampal and amygdalar volumes as well as their asymmetries in schizophrenia patients. Moreover, medial temporal lobe alterations have been observed, to a lower extent, in the unaffected relatives of schizophrenia patients (19) representing a morphological endophenotype that could reflect a higher risk for developing schizophrenia (11), rendering the hippocampus and the amygdala two key regions for all the features of this disease. Studies about shape characterization and mapping of temporo-limbic regions have been carried out before, on young (20) and on early onset schizophrenia patients (21) but, to our knowledge, a study on the local pattern of hippocampal and amygdalar tissue changes and their relationship with clinical symptoms on elderly schizophrenia patients has so far never been carried out. Localizing surface distortions in key brain regions such as hippocampus and amygdala could increase scientific knowledge regarding their involvement in elderly patients, the pathological process underlining the disease and could help clinicians in understanding the clinical manifestation of the disease in geriatric patients. To address this issue, we used an advanced image analysis method (radial atrophy mapping, RAM) which is capable of mapping profiles of volumetric differences in 3D with millimeter spatial accuracy. The method can also be used to attribute tissue differences to approximate hippocampal and amygdalar cytoarchitectonic subregions. From a clinical and functional perspective, the use of this method in elderly patients could enhance in vivo knowledge about localized tissue damages accounted by schizophrenia which, to date, have been principally studied in post-mortem tissues. So we applied this method to map brain differences in 20 patients with long-term, chronic schizophrenia, compared to 20 age-matched healthy elders. We hypothesized to find out structural and morphological differences between old patients and matched healthy elders in the direction of these found in young patients respect to young normal people; these changes could be related to negative and positive symptoms common in schizophrenia affected patients.

Methods

Study subjects and assessment

The schizophrenia patients were selected from the Psychogeriatric Ward of the IRCCS Centro San Giovanni di Dio Fatebenefratelli in Brescia, Italy, from December 2006 to April 2008 (17). The selection criteria included old age (60 years or older) and a DSM-IV diagnosis of schizophrenia with onset before age 40. Exclusion criteria included history of substance dependence, dementia, or other diseases of the central nervous system, or unstable medical conditions. The symptoms of schizophrenia were assessed with the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) (22). Patients underwent history taking, laboratory examinations, physical and neurological examinations, neuropsychological assessment, and MR scanning. Neuropsychological assessment was performed and recorded by a psychologist after at least 4 weeks of observation to check stability of the psychiatric symptoms. This included tests of language comprehension and production, long-term memory, constructional abilities, attention, and executive functions (23). Results of neuropsychological assessment were detailed in a previous article on the same sample (17).

Normal healthy elders (24) who were age-matched to the patients, underwent multidimensional assessment including clinical, neurological and neuropsychological evaluation as previously described (23).

Informed consent about study participation was obtained from the normal elderly participants, schizophrenia patients, in all cases - and from the patients’ relatives, whenever possible. When the degree of cognitive impairment raised doubts about competence, consent of family relatives was always sought. The participants consent was obtained according to the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was reviewed and approved by the local ethics committee (Comitato Etico delle Istituzioni Ospedaliere Cattoliche).

MR Acquisition and Processing

High-resolution gradient-echo sagittal three-dimensional (3-D) brain MRI scans were acquired with a Philips Gyroscan 1.0-T scanner (Philips, Eindhoven, The Netherlands; repetition time: 20 msec, echo time: 5 msec, flip angle: 30°, field of view: 220 mm, acquisition matrix: 256 × 256, slice thickness: 1.3 mm, no interslice gap). Images were then normalized by linearly transforming them to a customized template using the Statistical Parametric Mapping software (http://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm/software/spm2/), after manual setting of the anterior commissure as the origin of the stereotactic space, reorientation along the AC-PC line, and removal of voxels below the cerebellum with the MRIcro software (www.psychology.nottingham.ac.uk/staff/cr1/mricro.html). The hippocampi and amygdalae of patients and normal elderly participants were manually traced. A single neuroanatomically-trained tracer (A.P.) outlined the hippocampi, and another one (E.C.) outlined all amygdalae boundaries on contiguous coronal sections. Briefly, hippocampal segmentation included the hippocampus proper, dentate gyrus, subiculum (subiculum proper and presubiculum), alveus and fimbria. Each hippocampus comprised approximately 30–40 consecutive slices, and segmentation took about 30 min per subject. We note that there are automated methods for hippocampal segmentation, which we have used and even developed in prior studies, but manual tracing remains the gold standard for ensuring anatomical precision (25).

The starting point for amygdalar segmentation in the coronal plane was at the level where the amygdala was separated from the entorhinal cortex by the intrarhinal sulcus, or tentorial indentation, which formed a marked indent in its inferior border. The uncus, at the level of the basolateral nuclear groups, was considered as its anterior-lateral border. The amygdalo-striatal transition area between the lateral amygdala and the ventral putamen was considered as the posterior-lateral border. The posterior end of the amygdala was defined where gray matter started to appear, superior to the alveolus and laterally to the hippocampus (26).

Test–retest reliability on 20 subjects was good for both hippocampal (intraclass correlation coefficients were 0.85 for intra-rater and 0.88 for inter-rater reliability) and amygdalar tracing (intra-class correlations were 0.87 for intra-rater and 0.83 for inter-rater reliability); both tracers were blind to diagnosis. Amygdalar and hippocampal volumes do not require normalization by head size, but were treated as already normalized, due to the spatial normalization carried out on the original images; we retained them for statistical analyses (27). Patients and healthy elders did not differ for total intracranial volumes (t = −0.97, df = 37, p=0.38 on Student’s t Test)

Radial atrophy mapping (RAM)

Three-dimensional parametric surface mesh models were generated from the manually segmented hippocampal and amygdalar tracings (27). To assess hippocampal and amygdalar morphology, a medial curve was automatically defined as the 3D curve traced out by the centroid of the hippocampal and amygdalar boundary in each image slice. The radial size of each hippocampus and amygdala at each boundary point was assessed by automatically measuring the radial 3D distance from the surface points to the medial curve defined for each individual’s hippocampal and amygdalar surface model. Shorter and longer radial distances were used as an index of hippocampal and amygdalar shape contraction or expansion, respectively, and were visualized in color at the corresponding surface point (27).

This procedure allows us to perform statistical comparisons between groups at corresponding surface locations.

The reconstruction of the anatomic hippocampal subfield and amygdalar nuclei was based on the localization of the hippocampal subfield and amygdalar nuclei in histologic sections from a human atlas (28) (Figure 1A; 2A). The contour of each subfield and nucleus, as detected by the atlas, was used to project approximate structural subregional boundaries on the final mesh models, or to explore whether surface changes might be attributed to the involvement of deeper regions (Figure 1B; 2B). Anatomical mesh modeling methods (29) were used to match equivalent hippocampal and amygdalar surface points, obtained from manual tracings, across subjects and groups. To match the digitized points representing the hippocampus and amygdala surface traces in each brain volume, the manually derived contours were made spatially uniform by modeling them as a 3D parametric surface mesh (please, see (27) for detailed figures which help in understand the full process), thus ensuring the regional tissue mapping being truly locally specific. That is, the spatial frequency of digitized points making up the hippocampal and amygdalar surface traces was equalized within and across brain slices. These procedures allowed measurements to be made at corresponding surface locations in each subject that may then be compared statistically in 3D. The matching procedures also allowed the averaging of hippocampal and amygdalar surface morphology across all individuals belonging to a group and recorded the amount of variation between corresponding surface points relative to the group averages. The 3D parametric mesh models of each individual’s hippocampi and amygdalae were analyzed, in our study, to estimate the regional specificity of hippocampal and amygdalar tissue loss in schizophrenia patients.

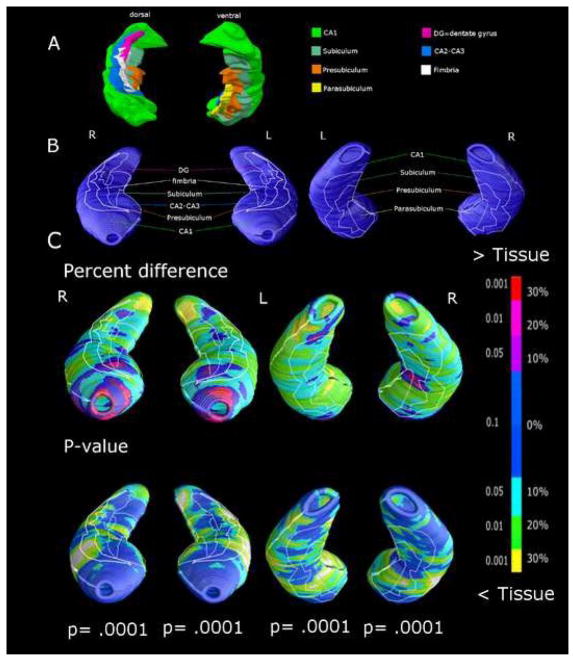

Figure 1.

(A) Surface of cytoarchitectonic sectors of the hippocampus reconstructed in 3D using an atlas (28) and projected on the surface of the mesh model (B). Local hippocampal differences between 20 elderly schizophrenia subjects and 19 healthy elders, expressed as percent difference and statistical significance (C). P values below maps represent the significance after correction for multiple comparisons (permutation test). Spots from light blue to yellow represent tissue reductions of 10 to 30% in schizophrenia patients respect to healthy elders.

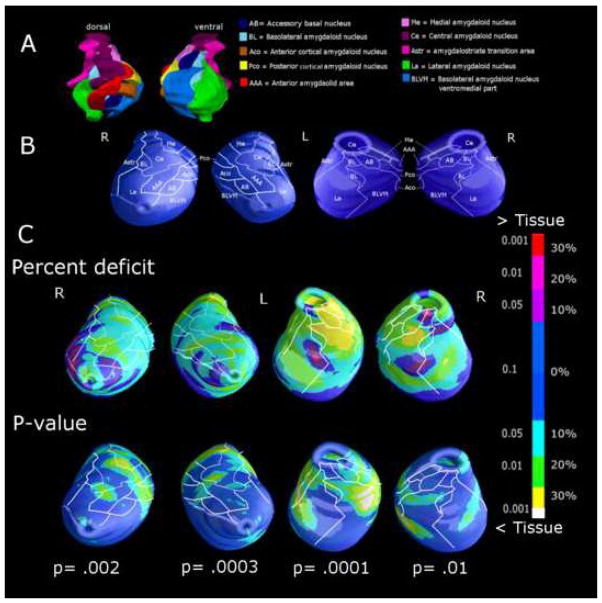

Figure 2.

(A) 3D surface reconstruction of amygdalar nuclei by an atlas (28) and projected on the surface of the mesh model (B). Local amygdala differences between 20 elderly schizophrenia subjects and 19 healthy elders, expressed as percent difference and statistical significance (C). P values below maps represent the significance after correction for multiple comparisons (permutation test). Spots from light blue to yellow represent tissue reductions of 10 to 30% in schizophrenia patients respect to healthy elders.

Statistical analysis

Clinical, sociodemographic, neuropsychological, hippocampal and amygdalar volumetric data were analyzed using SPSS V. 13.0. The non-parametric Mann-Whitney U-test was used to assess group differences in continuous variables while Chi-squared test was applied for dichotomous variables. The percent difference in mean radial distances (two tailed t tests) between patients and healthy elders (and the associated p value describing the significance of group differences) were plotted onto the model surface at each point of the hippocampus and amygdala, using a color code to produce statistical maps.

Maps of Pearson’s r correlations as well as the associated p-value maps (thresholded at p<0.05) between hippocampal/amygdalar morphology and positive and negative symptoms on the PANSS were computed in the group of schizophrenia patients.

A surface point significance threshold of p<0.05 was used to map hippocampal and amygdalar changes. All significance, percent difference and correlation maps were visualized using color codes on 3D surface models of the hippocampal and amygdalar subregions. A two-tailed permutation test was applied to all maps to provide an overall p value for the effects, that was corrected for multiple comparisons (30). Permutation methods basically measure the probability that the observed distribution of a given feature (e.g., the number of vertices with statistics below p<0.05 in the entire map) would occur by accident if the subjects were randomly assigned to groups. The effect observed in the random assignments was then compared to that observed in the true experiment. This calculation was made by computing the number of times that an effect with a similar or greater magnitude occurred in the random assignments compared to the true assignments, over the total number of “random” experiments run. This ratio represents the empirical probability that the observed pattern occurred by accident, and it provides an overall significance value for reliability of the map, corrected for multiple comparisons (31). More specifically, 10,000 permutations of the assignments for subjects to groups were computed, while keeping the total number of subjects in each group the same, in order to carry out 10,000 random experiments. In each of these experiments, instead of assigning 0 to cases (schizophrenia patients) and 1 to controls (healthy elders), as in the true experiment, the assignments of 0 and 1 to cases and controls was randomly scrambled (permuted). For each of these 10,000 permutations, the p-map of the differences for the “cases” (all individuals randomly assigned to group 0) versus “controls” (all individuals randomly assigned to group 1) was generated point by point along the whole 3D cortical mesh model, and a new p-map was obtained for each random experiment. Subsequently, the number of supra-threshold (i.e., significant) voxels was computed and compared between each random experiment and the true experiment. In the whole set of the 10,000 experiments, the total number of times that the supra-threshold count was equal or higher than that observed in the true experiment was divided by 10.000 (i.e., the number of random experiments carried out), and this estimated the probability that a map, with an amount of significant local differences greater than or equal to that observed in the true experiment, could be obtained by chance.

Finally, unthresholded effect size maps of the differences between schizophrenia and normal elders patients (Cohen’s d) were produced for hippocampi and amygdalae to check for truly local specificity of tissue distribution.

Results

The study groups (Table 1) were well matched for age, sex, and educational level. The cognitive performance of schizophrenia patients was, as expected, lower than that of the cognitively normal elderly (Table 1).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic, cognitive, clinical and volumetric features of the study groups.

| Healthy elders (N=20) | Elderly schizophrenia patients (N=20) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years [Range] | 70.3 ± 7.5 [56–84] | 67.4 ± 6.2 [59–78] | 0.204 |

| Sex (female) | 11 (55%) | 10 (50%) | 0.752 |

| Education, years | 9.7±4.4 | 7.6 ± 3.5 | 0.105 |

| Mini Mental State Exam [Range] | 29.0 ± 1.1 [27–30] | 22.8 ± 4.4 [14–30] | 0.0001 |

| Left_Amygdala (mm3)* | 1,989±305 | 1,629±356 | 0.002 |

| Right_Amygdala (mm3)* | 1,906±322 | 1,663±396 | 0.041 |

| Left_Hippocampus (mm3)* | 4,894±724 | 3,258±524 | 0.0001 |

| Right_Hippocampus (mm3)* | 4,993±619 | 3,400±649 | 0.0001 |

| Clinical features: Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale score (PANSS) | |||

| Positive symptoms subscale | -- | 19.7±5.2 | -- |

| Negative symptoms subscale | -- | 27.5±8.9 | -- |

Values denote mean ± SD or number (%). Significance is computed on Mann-Whitney U-test (with 38 degrees of freedom) for continuous variable and Chi-squared test (with one degree of freedom) for dichotomous variables.

Missing data for one healthy elder due to failure in segmentation procedure

The RAM procedure failed for one healthy elder, due to severe movement artifact during MRI acquisition, so shape and volumetric analyses were performed on 20 schizophrenia patients and 19 healthy elders.

The hippocampi and amygdalae displayed significant bilateral volume reduction in patients with schizophrenia respect to normal elders, with a mean global percent difference of 32% and 33% for the right and left hippocampi (Table 1), and of 13% and 18% for the right and left amygdalae (Table 1).

Radial atrophy maps showed that the hippocampus exhibited up to 30% significant tissue loss in the medial portion of the tail bilaterally, and a 20–30% deficit in the parasubiculum; tissue losses were more pronounced on the left side (Figure 1C). Milder but still significant tissue loss (in the range of 20%) was observed in the anterior lateral part of CA1, in CA2-3, and in the presubicular and subicular subfields.

The amygdala displayed greatest involvement in its ventral aspect (Figure 2C), with a significant 30% tissue loss in the accessory basal, medial and basolatero-ventro-medial nuclei, mainly on the left side. Milder tissue loss was also significant in the lateral, central, medial and cortical nuclei.

Despite the absence of significant correlations between global hippocampal or amygdalar volumes and clinical symptoms, both the amygdala and hippocampus showed significant negative correlations of local tissue loss with negative symptoms measured at the PANSS scale (see Figure 3)

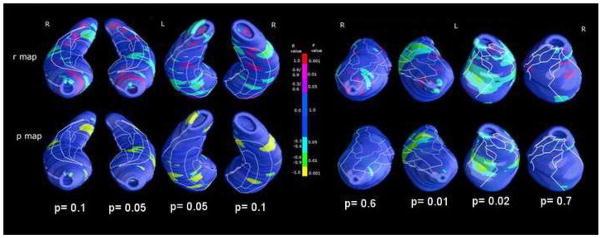

Figure 3.

Maps of positive (red range) and negative (green-yellow range) schizophrenia hippocampal and amygdalar local tissue correlation with negative symptoms at the PANSS. P values below maps represent the significance after correction for multiple comparisons (permutation test).

In particular, a significant relationship with negative symptoms was found encompassing mainly the left CA1 hippocampal sector along with small spots in the ventral left presubiculum. In the amygdale the relationship between negative symptoms and morphology was found only in the left amygdala: dorsally in the central nucleus and ventrally in the lateral nucleus (Pearson’s r=0.6, p=0.01). Correlations of both amygdala and hippocampus local tissue loss with positive symptoms measured at the PANSS scale were not significant (p>0.05 at Pearson’s Correlation).

Unthresholded effect size maps of Cohen’s d in the comparison between diagnostic group computed for hippocampi and amygdalae (Supplementary Figure 1) showed that in regions resulting affected in schizophrenia respect to normal subjects, the group effects were significant (percentage of non- overlap in distributions between groups ranging from 40 to more than 55%, Cohen’s d >0.982) respect to other areas of the hippocampus or amygdala for which distributions were 70% and more overlapping between groups (Cohen’s d<0.55).

Finally, we assessed relationships between cognitive and morphological features, finding just one significant positive Perarson’s r correlation between letter fluency neuropsychological test and left hippocampal volume (Pearson’s r between 0.60 and 0.80 in left hippocampal head, sector C1, p=0.006 at permutation test) in schizophrenia patients. No other significant correlations were found between cognitive and morphological features in schizophrenia or healthy elders groups (results not shown).

Discussion

In this work, we examined the volume and morphology of medial temporal lobe structures in a sample of elderly schizophrenia patients using an advanced technique able to identify local tissue abnormalities with high spatial accuracy. We hypothesized to find out structural and morphological differences between old patients and matched healthy elders, following a continued decline in hippocampus and amygdala across the lifespan in schizophrenia. These changes could have been related to negative and positive symptoms common in this disease.

Previous brain imaging studies pointed out grey matter volume decreases in schizophrenia patients involving many discrete and widely spread brain regions (see (32) for a review). Moreover, these results showed brain tissue deficits mainly located in regions involved in cognition and emotional processing such as the hippocampus and the amygdala. These reductions were found in both first episodes and chronic subjects supporting that brain abnormalities were present at the onset of illness, and were not simply a consequence of chronicity (32). Studies assessing brain morphometry at different phases of the illness, including late-life stages, together with longitudinal studies, can so elucidate further the role of clinical progression in this disorder.

In the present study, we found a bilateral and largely symmetrical distribution of differences in the schizophrenia sample mainly involving the lateral and medial aspects of CA1, CA2-3, and subicular subfields in the hippocampus. In addition, ventral amygdala showed an involvement of accessory basal, medial and baso-latero-ventral nuclei. To our knowledge, this is the first study describing results on medial temporal lobe morphology in elderly schizophrenia patients. Our results are in line with prior morphometric studies on younger patients, and even in first-degree unaffected relatives of patients. Some studies of subjects at high genetic risk for schizophenia have shown a volume deficit in the hippocampus and amygdale involving in particular the body and tail of the hippocampus, bilaterally (33). In addition, in line with our findings, Velakoulis and colleagues (34) compared chronic schizophrenia, first-episode psychosis, and ultra-high-risk individuals in terms of their hippocampal and amygdala volumes. They reported specific bilateral hippocampal volume reduction and amygdalar alterations in patients affected by chronic schizophrenia, not influenced by atypical or typical antipsychotic medications. The pattern of structural differences differed according to the type of psychosis (34), making bilateral hippocampal and amygdalar volume alterations a sign of more chronic schizophrenia. Moreover, in patients with methamphetamine psychosis (35) and in schizophrenia patients younger than our sample (36), hippocampal and amygdalar reductions have been widely reported.

More specifically, our results on elderly schizophrenia patients evidenced a 20–30% of significant tissue loss in the medio-caudal and antero-lateral aspects of CA-CA21, and medial section of hippocampal left head (pre- and para-subiculum) in line with results of Narr and colleagues (37), applying the same method to young first-episode patients. Taken together, these hippocampal volume reductions may be a robust neuroanatomical correlate of schizophrenia and may be present at first episode (38). The hippocampal formation is a convergence zone, in which unimodal and polynodal neocortical outputs ultimately come together. The primary projections to the hippocampus come from the enthorinal cortex through the perforant pathway to the dentate gyrus and through direct projections to hippocampal CA1 and CA3 subfields. Also, the entire structure is believed to be deeply involved in visual and verbal declarative memory, working memory and processing speed (39); these are among the most consistently impaired functions in schizophrenia. Moreover, the anterior hippocampus influences emotional and behavioural processing through the interaction with amygdala and hypothalamus (40) and supports frontal lobe activity via its outputs to the nucleus accumbens (40). In addition, it is recognized as the key organ involved in the response to stress, a threatening event at individual level which elicit physiological and behavioural responses (41). Both hippocampus and amygdala mediate allodynamic responses and are targets of allostatic load. Evidence suggest that the human hippocampus is particularly sensitive to elevated stress hormones and severe traumatic stress and shows greater changes than other brain areas, especially in psychiatric syndromes like schizophrenia, years before overt disease occurs (42).

Neuroimaging studies found that schizophrenia patients show a tendency to mislabel neutral or ambiguous stimuli as threatening, and exhibit increased medial temporal lobe activity to neutral or ambiguous stimuli (43). Moreover, high stress load in childhood and before puberty may interact with genetic and other vulnerability factors influencing the development of psychiatric disorders in the adulthood (44). Stress could affect amygdalar and hippocampal shapes contributing to the tissue deficits found later in elderly schizophrenia patients. Whether tissue deficit of the hippocampus is reversible or permanent is unclear (45). However, amygdalar and hippocampal tissue loss can also occur in the absence of elevated stress hormones levels. For example, stress early in post-natal life may result in long-term memory deficits and selective loss of hippocampal neurons (46). Finally, it is possible that pre-existing individual differences in the hippocampus and amygdala could partly increase vulnerability and decrease resilience against life stress (44) (47).

In our sample, the amygdala displayed an involvement mainly in its ventral aspect, with a 30% tissue reduction in the basolatero-ventro-medial nucleus, more severe on the left side. Milder tissue reduction was also significant in the lateral, centro-medial and cortical nuclei. The amygdala is involved in the appraisal of external stimuli with regard to their emotional significance (7) and volume loss in both left and right amygdalae has been documented in schizophrenia (8). More specifically, the basolatero-ventro-medial nucleus, which innervates several key components of the corticolimbic system including the anterior cingulate cortex and the hippocampal formation (48), is thought to play a central role in modulating memory and learning associated with stress and emotion (49), as well as associative learning and attention. Projections of the basolatero-ventro- medial nucleus may be of particular importance for the induction of abnormal circuitry in schizophrenia, as their growth during late adolescence and early adulthood may help to anticipate the onset of illness in susceptible individuals (50). A preponderance of cellular and molecular abnormalities has been reported in the hippocampal CA3/2 sectors, in which basolatero-ventro- medial nucleus afferents provide a robust innervation (50). Our findings are in line with the notion of amygdalo-cortical circuitry dysfunction in schizophrenia, which postulates that disturbances in the integration of emotion and cognition are secondary to atrophy of several different brain regions, including the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, the rostral anterior cingulate cortex, the hippocampal formation, and basolateral amygdala. All of these regions are highly anatomically and functionally interconnected through the GABA and glutamate systems (50). Moreover, the recent paper of Herringa and colleagues (51) postulates that men with decreased amygdala corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) system binding protein, involved in the CRF activity modulation, may be more vulnerable to the effects of stress exposure on the etiology or maintenance of schizophrenia.

Furthermore, our results of a correlation between left hippocampus, amygdala morphology and negative symptoms as measured trough PANSS scale support the hypothesis of an amygdalo- cortical circuitry dysfunction. Even though reports relating structural morphometry to clinical symptoms vary (52–53), our findings further support the role of the hippocampus and amygdala in the schizophrenia pathophysiology and suggest unique associations between individual structures and specific symptoms of the illness. Moreover, association between tissue reduction and negative symptoms should be interpreted along with earlier and more recent MRI data suggesting that they could be part of a phenotype characterized by an elevated risk and/or early manifestations of psychosis in high risk adolescents (53–54).

Finally, our results might not be attributable to long-term neuroleptic exposure, since similar morphological features can be detected, with a lesser severity, in unaffected relatives (19), nor to illness chronicity, as similar results have been reported in younger and in first-episode schizophrenia patients (34) (36). Moreover, as confirmed by effect size maps, the tissue loss found in schizophrenia patients and the association between tissue distribution and clinical symptoms were truly regionally specific, reinforcing our findings on hippocampus and amygdala shape abnormalities in elderly schizophrenia patients.

Conclusions

In conclusion our results showing tissue deficits and altered morphology in the hippocampus- amygdala complex of elderly schizophrenia patients, largely agree with findings in younger patients. Tissue loss mapped onto amygdalo-hippocampal subregions known to have bidirectional and specific connections with frontal cortical and limbic structures, and was related to clinical symptom severity. To study hippocampal ad amygdala shape abnormalities could increase our scientific knowledge on the conformation of their subregions in elderly schizophrenia patients. Indeed, the study of shape give us an indirect measure of in vivo schizophrenia neuropathology. Moreover, further studies could compare the hippocampus and amygdala morphologies of elderly schizophrenia patients with the ones of young schizophrenia or Alzheimer’s disease patients in order to understand to what extend the involvement of their subfield and nuclei is due to schizophrenia or Alzheimer’s Disease pathophysiology. Finally, to understand the in vivo pathophysiology of elderly schizophrenia patients could open important clinical perspectives for drugs treatment.

This study has strengths and limitations. First, studying elderly schizophrenia patients allows us to ascertain the impact of neurodegenerative processes, thought to occur in schizophrenia and certainly in normal aging, on morphological features reported in younger patients. Second, we controlled for the effect of neurodegeneration due to normal ageing was by pairing subjects with healthy elders of the same age, although an interaction of ageing with schizophrenia could not be quantitatively evaluated by this experimental design. Third, we were able to map morphological features of schizophrenia patients onto approximate cellular boundaries derived a from reliable human atlas. This allows us to appreciate how their abnormal morphology might be related to functionally linked structures and cellular fields with known projections to other parts of the brain. At least four limitations should be considered when interpreting our data. First, in the absence of reliable data regarding neuroleptic treatment over time, any possible treatment effect on the hippocampus and amygdala was not assessed so other studies considering potential confounding effects of psychotropic medications are urgently needed. Second - and as is usually the case when addressing late-life schizophrenia - our sample is small, and the present results need to be replicated in larger cohorts. Third, we were unable to find correlations between hippocampal and/or amygdalar morphology and PANNS positive symptoms; although previous studies on positive symptoms in schizophrenia demonstrated that these were very unstable and more labile than negative ones (55), this lack of correlation was unexpected and more studies on larger samples are strongly needed. Last, we cannot rule out the existence of early Alzheimer’s disease pathology in the schizophrenia group affecting primarily the hippocampus-amygdala complex, even if dementia was excluded through accurate history taking with caregivers or other knowledgeable proxy informants. Even so, there is no reason to believe that preclinical Alzheimer’s disease should be more frequent in these patients than in the general older population (56). If this should be the case, structural hippocampal and amygdalar changes in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease are usually minor, if detectable at all, and are not expected to be the major causative factor for the morphological differences found here in schizophrenia patients.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Fundings: This work was supported by Grants Ex Art 56533 F/B 1 and PS-Neuro Ex 56/05/11 (Italian Ministry of Health), and supported in part by a grant from the Italian Ministry of Health, Analisi dei Fattori di Rischio e di Potenziali Elementi Predittivi di Danno Neurodegenerativo Nelle Sindromi Parkinsoniane number 502/92.

Dr. Paul Thompson is supported, in part, by NIH Grants R01EB008281, EB008432, EB007813, AG036535 and AG020098, and by the NIBIB, NCRR, NIA, and NICHD, agencies of the U.S. National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: No Disclosures to Report.

References

- 1.Mc Intyre C. Dementia praecox as described by Kraepelin. Cinci J Med. 1949;30:412. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harvey PD, Czaja SJ, Loewenstein DA. Schizophrenia in later life. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2012;20:1–4. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e31823bbf93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Howard RJ. Schizophrenia in later life: emerging from the shadows. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;18:859–861. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181ef78eb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jeste DV, Lebowitz BD. The Leifer Report. 1997. Coming of age; pp. 39–40. Special Edition. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Duvernoy HM. The human hippocampus: functional anatomy, vascularization and serial sections with MRI. Springer; New York: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ferbinteanu J, Kennedy PJ, Shapiro ML. Episodic memory--from brain to mind. Hippocampus. 2006;16:691–703. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gainotti G. Disorders of emotional behaviour. J Neurol. 2001;248:743–749. doi: 10.1007/s004150170088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.White T, Cullen K, Rohrer LM, et al. Limbic structures and networks in children and adolescents with schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2008;34:18–29. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbm110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prestia A, Boccardi M, Galluzzi S, et al. Hippocampal and amygdalar volume changes in elderly patients with Alzheimer’s disease and schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2011;192:77–83. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2010.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thompson PM, Bartzokis G, Hayashi KM, et al. Time-lapse mapping of cortical changes in schizophrenia with different treatments. Cerebral Cortex. 2009;19:1107–1123. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhn152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gogtay N, Hua X, Stidd R, et al. Longitudinal mapping of white matter development in healthy siblings of childhood-onset schizophrenia patients. Archives of General Psychiatry. in press. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wright IC, Rabe-Hesketh S, Woodruff PW, et al. Meta-analysis of regional brain volumes in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:16–25. doi: 10.1176/ajp.157.1.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harrison PJ. The hippocampus in schizophrenia: a review of the neuropathological evidence and its pathophysiological implications. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2004;174:151–162. doi: 10.1007/s00213-003-1761-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Antonova E, Sharma T, Morris R, et al. The relationship between brain structure and neurocognition in schizophrenia: a selective review. Schizophr Res. 2004;70:117–145. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2003.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stehen RG, Mull C, McClure R, et al. Brain volume in first-episode schizophrenia: systematic review and meta-analysis of magnetic resonance imaging studies. Br J Psychiatry. 2006;188:510– 518. doi: 10.1192/bjp.188.6.510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gothelf D, Soreni N, Nachman RP, et al. Evidence for the involvement of the hippocampus in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2000;10:389–395. doi: 10.1016/s0924-977x(00)00097-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Frisoni GB, Prestia A, Adorni A, et al. In vivo neuropathology of cortical changes in elderly persons with schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;66:578–585. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thompson PM, Vidal C, Giedd JN, et al. Mapping adolescent brain change reveals dynamic wave of accelerated gray matter loss in very early-onset schizophrenia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:11650–11655. doi: 10.1073/pnas.201243998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ho BC, Magnotta V. Hippocampal volume deficits and shape deformities in young biological relatives of schizophrenia probands. Neuroimage. 2010;49:3385–3393. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.11.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Narr KL, van Erp TG, Cannon TD, et al. A twin study of genetic contributions to hippocampal morphology in schizophrenia. Neurobiol Dis. 2002;11:83–95. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.2002.0548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nugent TF, Herman DH, Ordonez A, et al. Dynamic Mapping of Hippocampal Development in Childhood Onset Schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2007;90:62–70. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2006.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Andreasen NC, Carpenter WT, Jr, Kane JM, et al. Remission in schizophrenia: proposed criteria and rationale for consensus. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:441–449. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.3.441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lezak M, Howieson D, Loring DW. Neuropsychological Assessment. 4. Oxford: University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Galluzzi S, Testa C, Boccardi M, et al. The Italian Brain Normative Archive of structural MR scans: norms for medial temporal atrophy and white matter lesions. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2009;21:266–276. doi: 10.1007/BF03324915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morey RA, Petty CM, Xu Y, et al. A comparison of automated segmentation and manual tracing for quantifying hippocampal and amygdala volumes. Neuroimage. 2009;45:855–866. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.12.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pruessner JC, Li LM, Serles W, et al. Volumetry of hippocampus and amygdala with high- resolution MRI and three-dimensional analysis software: minimizing the discrepancies between laboratories. Cereb Cortex. 2000;10:433–442. doi: 10.1093/cercor/10.4.433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thompson PM, Hayashi KM, De Zubicaray GI, et al. Mapping hippocampal and ventricular change in Alzheimer disease. Neuroimage. 2004;22:1754–1766. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.03.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mai JK, Paxinos G, Voss T. Atlas of the Human Brain. 3. Elsevier; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thompson PM, Schwartz C, Toga AW. High-resolution random mesh algorithms for creating a probabilistic 3D surface atlas of the human brain. Neuroimage. 1996;3:19–34. doi: 10.1006/nimg.1996.0003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thompson PM, Hayashi KM, de Zubicaray G, et al. Dynamics of gray matter loss in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci. 2003;23:994–1005. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-03-00994.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Arndt S, Cizadlo T, Andreasen NC, et al. Tests for comparing images based on randomization and permutation methods. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1996;16:1271–1279. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199611000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Levitt JJ, Bobrow L, Lucia D, et al. A selective review of volumetric and morphometric imaging in schizophrenia. Curr Top Behav Neurosci. 2010;4:243–281. doi: 10.1007/7854_2010_53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Witthaus H, Kaufmann C, Bohner G, et al. Gray matter abnormalities in subjects at ultra-high risk for schizophrenia and first-episode schizophrenic patients compared to healthy controls. Psychiatry Res. 2009;173:163–169. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2008.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Velakoulis D, Wood SJ, Wong MT, et al. Hippocampal and amygdala volumes according to psychosis stage and diagnosis: a magnetic resonance imaging study of chronic schizophrenia, first- episode psychosis, and ultra-high-risk individuals. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:139–149. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.2.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Orikabe L, Yamasue H, Inoue H, et al. Reduced amygdala and hippocampal volumes in patients with methamphetamine psychosis. Schizophr Res. 2011;132:183–189. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2011.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Barkataki I, Kumari V, Das M, et al. Volumetric structural brain abnormalities in men with schizophrenia or antisocial personality disorder. Behav Brain Res. 2006;169:239–247. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2006.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Narr KL, Thompson PM, Szeszko P, et al. Regional specificity of hippocampal volume reductions in first-episode schizophrenia. Neuroimage. 2004;21:1563–1575. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2003.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maller JJ, Daskalakis ZJ, Thomson RH, et al. Hippocampal volumetrics in treatment-resistant depression and schizophrenia: the devil’s in de-tail. Hippocampus. 2012;22:9–16. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dickinson D, Iannone VN, Wilk CM, et al. General and specific cognitive deficits in schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2004;55:826–833. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2003.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Johnson JD. Dysfunction of the anterior hippocampus: the cause of fundamental schizophrenic symptoms? Med Hypotheses. 2005;65:55–60. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2005.01.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McEwen BS. The neurobiology of stress: from serendipity to clinical relevance. Brain Research. 2000;886:172–189. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)02950-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McEwen BS, Magariños AM. Stress Effects on Morphology and Function of the Hippocampus. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1997;821:271284. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1997.tb48286.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kosaka H, Omori M, Murata T, et al. Differential amygdala response during facial recognition in patients with schizophrenia: an fMRI study. Schizophr Res. 2002;57:87–95. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(01)00324-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Weber K, Rockstroh B, Borgelt J, et al. Stress load during childhood affects psychopathology in psychiatric patients. BMC Psychiatry. 2008;8:63. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-8-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McEwen BS. Protective and damaging effects of stress mediators. The New England Journal of Medicine. 1998;338:171–180. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199801153380307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.VanItallie TB. Stress: A Risk Factor for Serious Illness. Metabolism. 2002;51:40–45. doi: 10.1053/meta.2002.33191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lupien SJ, Evans A, Lord C, et al. Hippocampal volume is as variable in young as in older adults: implications for the notion of hippocampal atrophy in humans. Neuroimage. 2007;34:479– 485. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.09.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Swanson LW, Petrovich GD. What is the amygdala? Trends Neurosci. 1998;21:323–331. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(98)01265-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kim JJ, Diamond DM. The stressed hippocampus, synaptic plasticity and lost memories. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2002;3:453–462. doi: 10.1038/nrn849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Benes FM, Lim B, Matzilevich D, et al. Circuitry-based gene expression profiles in GABA cells of the trisynaptic pathway in schizophrenics versus bipolars. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:20935–20940. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810153105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Herringa RJ, Roseboom PH, Kalin NH. Decreased amygdala CRF-binding protein mRNA in post-mortem tissue from male but not female bipolar and schizophrenic subjects. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;8 :1822–1831. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang L, Mamah D, Harms MP, et al. Progressive deformation of deep brain nuclei and hippocampal-amygdala formation in schizophrenia. Biol Psy. 2008;64:1060–1068. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rajarethinam R, DeQuardo JR, Miedler J, et al. Hippocampus and amygdala in schizophrenia: assessment of the relationship of neuroanatomy to psychopathology. Psychiatry Res. 2001;108:79– 87. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4927(01)00120-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Welch KA, Stanfield AC, Moorhead TW, et al. Amygdala volume in a population with special educational needs at high risk of schizophrenia. Psychol Med. 2010;40:945–954. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709990870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hull JW, Smith TE, Anthony DT, et al. Patterns of symptoms change: a longitudinal analysis. Schizophr Res. 1997;24:17–18. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jellinger KA, Gabriel E. No increased incidence of Alzheimer’s disease in elderly schizophrenics. Acta Neuropathol. 1999;97:165–169. doi: 10.1007/s004010050969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.