Abstract

Background

Sorafenib was FDA approved in 2005 for treatment of renal cell carcinoma (RCC) based on the results of the pivotal phase 3 clinical trial, TARGET (Treatment Approaches in Renal Cancer Global Evaluation Trial). Since that time, numerous clinical studies have been undertaken that substantially broaden our knowledge of the use of sorafenib for this indication.

Methods

We systematically reviewed PubMed, Web of Science, Embase, Cochrane Library, and www.clinicaltrials.gov for prospective clinical studies using single agent sorafenib in RCC and published since 2005. Primary endpoints of interest were progression-free survival (PFS) and safety. PROSPERO International prospective register of systematic reviews #CRD42014010765.

Results

We identified 30 studies in which 2182 patients were treated with sorafenib, including 1575 patients who participated in randomized controlled phase 3 trials. In these trials, sorafenib was administered as first-, second- or third-line treatment. Heterogeneity among trial designs and reporting of data precluded statistical comparisons among trials or with TARGET. The PFS appeared shorter in second- vs. first-line treatment, consistent with the more advanced tumor status in the second-line setting. In some trials, incidences of grade 3/4 hypertension or hand-foot skin reaction (HFSR) were more than double that seen in TARGET (4% and 6%, respectively). These variances may be attributable to increased recognition of HFSR, or potentially differences in dose adjustments, that could be consequences of increased familiarity with sorafenib usage. Several small studies enrolled exclusively Asian patients. These studies reported notably longer PFS than was observed in TARGET. However, no obvious corresponding differences in disease control rate and overall survival were seen.

Conclusions

Collectively, more recent experiences using sorafenib in RCC are consistent with results reported for TARGET with no marked changes of response endpoints or new safety signals observed.

Introduction

Sorafenib was approved in 2005 for treatment of renal cell carcinoma (RCC) based on the results of the pivotal phase 3 clinical trial, TARGET (Treatment Approaches in Renal Cancer Global Evaluation Trial) [1]. This randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter study examined overall survival (OS), median progression-free survival (PFS), objective response rate (ORR), and safety in 903 patients with histologically confirmed metastatic clear-cell RCC who had had progression after one systemic treatment within the previous 8 months. Patients with brain metastases or prior exposure to vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) pathway inhibitors were excluded. In TARGET, sorafenib significantly extended median PFS from 2.8 months in the placebo group to 5.5 months (hazard ratio for disease progression in the sorafenib group, 0.44; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.35 to 0.55;P<0.01), with an acceptable safety profile [1].

While sorafenib was under review by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), several expanded access programs were established. In the open-label EU-ARCCS (EUropean Advanced Renal Cell Carcinoma Study; N = 1150), NA-ARCCS (North America-Advanced Renal Cell Carcinoma Study; N = 2504), and AUS1 (N = 47) studies, median PFS (95% CI) was 6.6 (6.1–7.4) [2], 5.5 (5.1–5.8) [3], and 6.5 (2.61–10.41) [4] months, respectively (Table 1). Notably, in these trials, sorafenib was used as a first-line systemic agent in 33%-50% of patients, and patients were not required to have clear cell histology.

Table 1. TARGET and expanded access trials.

| NCT00073307TARGET [1] | NCT00492986EU-ARCCS [2] | NCT00111020NA-ARCCS [3] | AUS1 [4] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trial Design | Randomized Double-blind | Expanded Access | Expanded Access | Expanded Access |

| N | 903 | 1159 | 2515 | 47 |

| Sorafenib arm, n efficacy | 451 | 1150 | 2504 | 47 |

| Sorafenib arm, n safety | 451 | 1145 | 2504 | 47 |

| Patient baseline characteristics a | ||||

| Age, median (range),years | 58 (19–86) | 62 (18–84) | 63 (13–93) | 60-(34–83) |

| Male, n (%) | 315 (70) | 858 (75) | 1734 (69) | 35 (75) |

| Race, n (%) | ||||

| White | NR | NR | 2231 (89) b | NR |

| Black | NR | NR | 102 (4) | NR |

| Hispanic | NR | NR | 85 (3) | NR |

| Asian | NR | NR | 38 (2) | NR |

| Other | NR | NR | 96 (4) | NR |

| ECOG PS, n (%) | ||||

| 0 | 219 (49) c | 460 (40) d | NR e | 14 (30) |

| 1 | 223 (49) | 516 (45) | NR | 24 (51) |

| 2 | 7 (2) | 169 (15) | NR | 9 (19) |

| RCC histology, n (%) | ||||

| Clear cell | 894 (99) | 909 (79) | 2302 (92) | 33 (70) |

| MSKCC score, n (%) | ||||

| Favorable | 233 (52) | NR | NR | 5 (11) |

| Intermediate | 218 (48) | NR | NR | 28 (60) |

| Poor | NR | NR | 14 (29) | |

| Prior systemic therapy, n (%) | 903 (100) | 765 (67) | 1250 (50) | 24 (51) |

| Prior nephrectomy, n (%) | 422 (94) | 1020 (89) | 2081 (83) | 37 (79) |

| Sorafenib treatment | ||||

| Median (range) duration of treatment, months | 5.3 | NR | 2.8 (<1–18.7) | NR |

| Efficacy | ||||

| OS, months (95% CI) | 17.8 (NR) | NR | 12 (11.0–12.6) 1st line; 10.6 (9.9–13.8) previously treated | 11.9 (4.99–18.88) |

| HR vs PBO(95% CI) | 0.88 (0.74–1.04), P = .146;[0.78 (0.62–0.97), P = .029 crossover patients censored] | NA | NA | NA |

| PFS, months (95% CI) | 5.5 (NR) | 6.6 (6.1–7.4) | 5.5 (5.1–5.8) | 6.5 (2.61–10.41) |

| Response, n(%) | ||||

| CR | 1 (< 1) | 1 (<1) | 1 (<1) f | 1 (2) |

| PR | 43 (10) | 45 (4) | 67 (4) f | 6 (13) |

| SD | 333 (74) | 633 (60) | 1511 (80) f | 29 (62) |

| Safety, n (%) | ||||

| Treatment-related AEs | 392 (87) | 1072 (94) | NR | NR |

| Grade 3 or 4 | 132 (29) | 519 (45) | NR | NR |

| Treatment-emergent AEs | NR | NR | NR | 44 (94) |

| Grade 3 or 4 | NR | NR | NR | 28 (60) |

| SAEs | 154 (34) | 515 (45) | NR | 10 (21) g |

| Treatment-emergent AEs (n%) | ||||

| Fatigue | 165 (37) | 388 (34) h | NR | 20 (43) |

| Grade 3 or 4 | 22 (5) | 81 (7) | 113 (5) g | 4 (9) |

| HFSR | 134 (30) | 645 (56) | 25 (53) | |

| Grade 3 | 25 (6) | 149 (13) | 238 (10) | 6 (13) |

| Rash or desquamation | 180 (40) | 379 (33) | NR | 22 (47) |

| Grade 3 or 4 | 4 (1) | 60 (5) | 124 (5) | 3 (6) |

| Alopecia | 122 (27) | 375 (33) | NR | 10 (21) |

| Grade 3 or 4 | 1 (<1) | 0 | 2 (<1) | 0 |

| Nausea | 102 (23) | 198 (17) | NR | 19 (40) |

| Grade 3 or 4 | 3 (< 1) | 14 (1) | 38 (1) | 4 (9) |

| Diarrhea | 195 (43) | 633 (55) | NR | 15 (32) |

| Grade 3 or 4 | 11 (2) | 84 (7) | 58 (2) | 0 |

| Hypertension | 76 (17) | 223 (20) | NR | 11 (23) |

| Grade 3 or 4 | 16 (4) | 70 (6) | 114 (5) | 4 (9) |

| Weight loss | 46 (10) | 128 (11) | NR | NR |

| Grade 3 or 4 | 3 (< 1) | 13 (1) | 4 (<1) | NR |

| Reduced appetite/anorexia | NR | 249 (22) | NR | 16 (34) |

| Grade 3 or 4 | NR | 33 (3) | 26 (1) | 1 (2) |

| Dyspnea | 65 (14) | NR | NR | NR |

| Grade 3 or 4 | 16 (4) | NR | NR | NR |

| Constipation | 68 (15) | 81 (7) | NR | NR |

| Grade 3 or 4 | 3 (1) | 3 (<1) | 4 (<1) | NR |

| Additional References | [5–15] | [16–21] | [22–24] | |

| Funding | Bayer HealthCare and Onyx Pharmaceuticals | Bayer HealthCare and Onyx Pharmaceuticals | Bayer HealthCare and Onyx Pharmaceuticals | Bayer Australia |

Abbreviations: AE = adverse event; CI = confidence interval; CR = complete response; ECOG PS = Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; HFSR = hand-foot skin reaction; HR = hazard ratio; MSKCC = Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center; NE = estimable; NR = not reported; OS = overall survival; PBO = placebo; PFS = progression-free survival; PR = partial response; SAE = serious adverse event; SD = stable disease.

a Unless otherwise specified, refers to entire study population.

b Data missing for 36 pts.

c Data missing for 2 pts.

d Data missing for 5 pts.

e Eligibility criteria included ECOG PS 0–2 with waivers granted to selected pts with PS 3 or 4.

f n = 1891.

g Considered treatment related.

h All reported AEs were considered treatment related.

The TARGET trial, which formed the basis for sorafenib approval, and these expanded access studies, represented the collective experience with sorafenib in RCC at the time of its approval. Since then, the treatment landscape for RCC has changed considerably. Clinicians now have nearly 10 years of additional experience in the use of sorafenib, managing its side effects, and evaluating response to angiogenesis inhibitors in larger and more diverse patient populations. Moreover, additional targeted systemic therapies, such as sunitinib, axitinib, dovitinib, bevacizumab, trebananib, and temsirolimus, pazopanib, and everolimus have been, and continue to be, investigated in RCC. An increasing emphasis is being placed on the use of these agents in the first-line setting, and several clinical trials have focused on head-to-head comparisons with sorafenib. Since complete objective responses are rare, studies are also investigating the use of sorafenib sequentially (either prior to, or following) or in combination with other targeted agents, as an open-ended management of metastatic kidney cancer.

The abundance of data from published clinical studies of sorafenib in RCC substantially broadens our knowledge base. To date, the collective experience has not been comprehensively reviewed and aggregated. The objective of this study is to understand the body of evidence defining a more contemporary perspective on efficacy and safety of sorafenib in patients with RCC treated since 2005. The issue of relative efficacy versus comparator drugs is not addressed in this review.

Methods

Protocol registration

The protocol for this study is registered at the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) and may be accessed at http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.asp?ID=CRD42014010765#.U9gsn_ldW3A.

Databases, search methodology, and eligibility criteria

The search terms (“sorafenib” or “Nexavar” or “BAY 43–9006”) AND (“RCC” or “renal cancer” or “kidney cancer”) were used to identify relevant publications, including meeting abstracts, in 4 electronic databases: PubMed (1/1/2005–3/3/2014), ISI Web of Science (1/1/2005–2/28 2014), Embase (1/1/2005–3/10/2014), and Cochrane Library (1/1/2005–2/28/2014). Bibliographies from pertinent review articles were hand-searched for additional relevant citations. Two independent reviewers examined titles and abstracts to determine eligibility for all identified records. When eligibility could not be determined from the abstract, the full publication was used. Disagreements were resolved by discussion between the two reviewers. Records were excluded for the following reasons in this sequence: 1) review articles, meeting reports, editorials, or guidelines; 2) not written in English; 3) reported only preclinical data, phase 1 trial data, data from a pilot or exploratory study, or data from a study with <20 patients receiving sorafenib; 4) reported data for patients included in the TARGET clinical trial; 5) reported data from a trial in which there was no discrete sorafenib arm or sorafenib was used only in combination with another systemic anticancer agent; 6) results from the reported study did not include patients with RCC, or the results in patients with RCC were only presented pooled with other tumor types; 7) presented results from a retrospective or observational study. Following identification of eligible studies, Internet searches (using Google) were performed to identify additional publications. Search terms consisted of the last names of the first and last authors for each of the already identified publications.

In addition, www.clinicaltrials.gov was searched, using the same search terms, to identify clinical trials registered between 1/1/2005 and 5/12/2014. Trials were excluded if they 1) were phase 1 or included fewer than 20 patients receiving sorafenib; 2) had no discrete sorafenib arm, or sorafenib was used only in combination with another systemic anticancer agent; or 3) were observational.

Data collection

Data were extracted to spreadsheets that had been pilot-tested to ensure that the included fields encompassed all desired data. When interim and mature data were both identified, the most recent data were used. Data were extracted exclusively for single-agent sorafenib arms. The primary endpoints of interest in this study were PFS and adverse events (AEs), especially hypertension, diarrhea, hand-foot skin reaction, and fatigue. Secondary outcomes of interest were OS and response rate (RR).

One reviewer extracted data and a second reviewed each field for accuracy. In some instances, where data are reported as n (%), only the number of patients or the percentage was published. For consistency of reporting, the corresponding values were calculated based on the total number of patients in the relevant study population. Similarly, when units for duration of treatment, PFS, or OS values were reported in days or weeks, values were converted to months as follows. Days: 12 x (reported value/365); Weeks: 12 x (reported value/52).

The following variables were extracted for each phase 3 and expanded access study (Tables 1 and 2): line of therapy; total number of patients; number of patients in the sorafenib arm; brief description of trial design; patient age, gender, race, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (ECOG PS), RCC histology, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) status; number of prior systemic therapies; prior nephrectomy; duration of sorafenib treatment; OS and hazard ratio, median PFS and hazard ratio, clinical benefit rate (complete response [CR], partial response [PR], stable disease [SD]), treatment-related and treatment-emergent AEs (overall and grade 3/4), and selected AEs that were observed in >20% of patients in any phase 3 study (overall and grade 3/4). For phase 2 and smaller studies, a subset of these variables was extracted (Table 3 [25–56] and Table 4 [57–67]).

Table 2. Randomized, open-label, phase 3 trials of sorafenib in RCC published following the TARGET trial.

| NCT00920816 AGILE 1051 [68,69] | NCT01481870CROSS-J-RCC a [70] | NCT00732914SWITCH [71] | NCT00678392AXIS [72–75] | NCT00474786INTORSECT [76] | NCT01223027GOLD-RCC [77] | NCT01030783TIVO-1 [78–83] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Line of therapy | 1st | 1st | 1st | 2nd b | 2nd | 2nd | 3rd | 1st or 2nd |

| Trial design | sorafenib vs axitinib | sorafenib followed by sunitinib at progression and vice versa | sorafenib followed by sunitinib at progression vice versa | sorafenib vs axitinib | sorafenib vs temsirolimus | sorafenib vs dovitinib | sorafenib vs tivozanib | |

| N | 288 | 124 | 365 | 723 | 512 | 570 | 517 | |

| Sorafenib arm, n efficacy | 96 | 63 | 182 | 76 | 362 | 253 | 286 | 257 |

| Sorafenib arm, n safety | 96 | 63 | 177 | 76 | 355 | 252 | 284 | 257 |

| Patient baseline characteristics | ||||||||

| Age, median (range) | 58 (20–77) | 66 (44–79) | 64 (39–84) | 65 (40–83) | 61 (22–80) | 61 (21–80) | 62 (18–81) | 59 (23–85) |

| Gender | ||||||||

| Male, n (%) | 74 (77) | 53 (84) | 138 (76) | 135(74) | 258 (71) | 192 (76) | 219 (77) | 189 (74) |

| Race | ||||||||

| White | 66 (69) | NR | NR | NR | 269 (74) | 163 (64) | 232 (81) | 249 (97) |

| Black | 0 | NR | NR | NR | 4 (1) | NR | 5 (2) | 0 |

| Hispanic | NR | NR | NR | NR | 0 | NR | 0 | 0 |

| Asian | 24 (25) | NR | NR | NR | 81 (22) | 50 (20) | 40 (14) | 8 (3) |

| Other | 6 (6) | NR | NR | NR | 8 (2) | 40 (16) | 9 (3) | 0 |

| ECOG PS, n (%) | ||||||||

| 0 | 55 (57) | NR | 124 (68) | 112 (61) | 200 (55) | 113 (45) | NR | 139 (54) |

| 1 | 41 (43) | NR | 58 (32) | 70 (38) | 160 (44) | 139 (55) | NR | 118 (46) |

| 2 | 0 | NR | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | NR | NR |

| Data missing | 0 | NR | 0 | 0 | NR | 1 (<1) | NR | NR |

| RCC histology, n (%) | ||||||||

| Clear cell | NR (100) | NR | 164 (90) | 154 (84) | NR (100) | 208 (82) | NR (100) | NR (100) |

| MSKCC score, n (%) | ||||||||

| Favorable | 53 (55) | 14 (22) | 71 (39) | 90 (45) | 101 (28) | 44 (17) | 59 (21) | 87 (34) |

| Intermediate | 40 (42) | 49 (78) | 108 (59) | 94 (51) | 130 (36) | 177 (70) | 162 (57) | 160 (62) |

| Low/poor | 2 (2) | 0 | 1 (<1) | 1 (<1) | 120 (33) | 32 (13) | 65 (23) | 10 (4) |

| Missing data | 1 (1) | 0 | NR | NR | 11 (3) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Prior systemic therapy | ||||||||

| 0 | (96) 100 a | 63 (100) c | 182 (100) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 181 (70) |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 76 (42) | NR (100) | 512 (100) | 0 | 76 (30) |

| >1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | NR (100) | 0 |

| Prior nephrectomy | 86 (90) | 56 (89) | 167 (92) | 168 (92) | NR | 219 (87) | 260 (91) | (100) |

| Sorafenib treatment | ||||||||

| Median (range) duration, months | 10.0 (0.2–21.2) | NR | Mean (SD): 8.7 (8.7) | Mean (SD): 3.7 (3.5) | 5.0 (0.03–20) | 3.6 (0.2–24.2) | 3.7 (< 1.0–16.9) | 9.5 (NR) |

| Efficacy | ||||||||

| OS, months (95% CI) | NR | NR | NR | 19.2(17.5–22.3) | 16.6(13.6–18.7) | 11.0(8.6–13.5) | 29.3 (NR) | |

| HR vs comparator (95% CI) | NR | NR | NR | 0.969 AX vs SOR (0.800–1.174) P = 0.3744 | 1.31 TEM vs SOR (1.05–1.63) P = 0.01 | 0.96 DOV vs SOR (0.75–1.22) | 1.245 TIV vs SOR (0.954–1.624) P = 0.105 | |

| PFS, months (95% CI) | 6.5 (4.7–8.3) | 7.0 (NR) | 5.9 (NR) | 2.8 (NR) | 4.7 (4.6–5.6) | 3.9 (2.8–4.2) | 3.6 (3.5–3.7) | 9.1 (7.3–9.5) |

| HR vs comparator (95% CI) | 0.77 AX vs SOR (0.56–1.05);P = 0.038 | 0.67 SU vs SOR (0.42–1.08) | 1.19 SO vs SU (<1.47 d ); P = 0.92 | 0.55 SU vs SO (<0.74 d ); P = 0.0001 | 0.665 AX vs SOR(0.544–0.812) | 0.87 TEM vs SOR (0.71–1.07) P = 0.19 | 0.86 DOV vs SOR (9.72–1.04); P = 0.063 | 0.797 e TIV vs SOR (0.639–0.993) P = 0.042 |

| Clinical benefit, n (%) | ||||||||

| CR | 0 | NR | 5 (3) i | 1 (1) | 0 | 1 (<1) | 0 | 2 (<1) |

| PR | 14 (15) | NR | 50 (28) i | 4 (5) | 43 (9) | 19 (8) | 11 (4) | 56 (23) |

| SD | 51 (53) | NR | 68 (38) i | 19 (25) | 197 (54) | 153 (60) | 149 (52) | 68 (65) |

| Safety, n (%) | ||||||||

| Treatment-related AEs | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 214 (83) |

| Grade 3 or 4 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 131 (51) |

| Treatment-emergent AEs f | 90 (94) | NR | 172 (97) | 64 (84) | 346 (97) | 252 (100) | NR | 249 (97) |

| Grade 3 or 4 | NR | NR | 117 (66) | 27 (36) | NR | 174 (69) | NR | 179 (70) h |

| SAEs | 24 (25) | NR | NR | NR | 110 (31) | 85 (34) | NR | NR |

| Fatigue | 25 (26) | 26 (42) g | 57 (32) | 9 (12) | 112 (32) | 85 (34) | 97 (34) | 41 (16) |

| Grade 3 or 4 | 1 (1) | 1 (2) g | 8 (4.5) | 0 | 18 (5) | 18 (7) h | 24 (8) | 9 (4) |

| HFSR | 37 (39) | 54 (86) | 69 (39) | 16 (21) | 181 (51) | 131 (52) | 115 (40) | 139 (54) |

| Grade 3 | 15 (16) | 16 (25) | 21 (12) | 5 (7) | 57 (16) | 38 (15) h | 18 (6) | 47 (17) |

| Rash or desquamation | 19 (20) | 31 (50) g | 53 (30) | 12 (16) | 112 (32) | 88 (35) | 66 (23) | NR |

| Grade 3 or 4 | 1 (1) | 9 (15) g | 3 (2) | 1 (1) | 14 (4) | 8 (3) h | 6 (2) | NR |

| Alopecia | 18 (19) | NR | 55 (31) | 4 (5) | 115 (32) | 78 (31) | 61 (21) | 55 (21) |

| Grade 3 or 4 | NR | NR | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 h | 1 (< 1) | 0 |

| Nausea | 14 (15) | 6 (10) | 39 (22) | 6 (8) | 77 (22) | 71 (28) | 83 (29) | 19 (7) |

| Grade 3 or 4 | 1 (1) | 0 | 2 (1) | 1 (1) | 4 (1) | 3 (1) h | 7 (2) | 1 (<1) |

| Diarrhea | 38 (40) | 26 (41) | 96 (54) | 26 (34) | 189 (53) | 158 (63) | 128 (45) | 84 (33) |

| Grade 3 or 4 | 5 (5) | 4 (6) | 9 (5) | 3 (4) | 26 (7) | 14 (6) h | 11 (4) | 17 (7) |

| Hypertension | 28 (29) | 28 (44) | 57 (32) | 6 (8) | 103 (29) | NR | 79 (28) | 88 (34) |

| Grade 3 or 4 | 1 (1) | 11 (17) | 16 (9) | 2 (3) | 39 (11) | NR | 47 (17) | 45 (18) |

| Weight loss | 23 (24) | NR | NR | NR | 74 (21) | 51 (20) | 87 (31) | 53 (21) |

| Grade 3 or 4 | 3 (3) | NR | NR | NR | 5 (1) | 5 (2) h | 1 (< 1) | 9 (4) |

| Reduced appetite/ anorexia | 18 (19) | 25 (40) | 37 (21) | 12 (16) | 101 (29) | 93 (37) | 99 (35) | 24 (9) |

| Grade 3 or 4 | 0 | 0 | 2 (1) | 0 | 13 (4) | 8 (3) h | 14 (5) | 2 (1) |

| Dyspnea | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 45 (18) | 57 (20) | 22 (9) |

| Grade 3 or 4 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 11 (4) h | 21 (7) | 5 (2) |

| Constipation | NR | NR | NR | NR | 72 (20) | 57 (23) | 69 (24) | NR |

| Grade 3 or 4 | NR | NR | NR | NR | 3 (1) | 1 (< 1) h | 3 (1) | NR |

| Hypo-thyroidism | 7 (7) | 19 (33) i | NR | NR | 29 (8) | NR | 8 (3) | NRj |

| Grade 3 or 4 | 0 | 1 (2) i | NR | NR | 0 | NR | 0 | NR |

| Additional References | [84] | [85,86] | [87–96] | [97,98] | [99–101] | [83,102,103] | ||

| Funding | Pfizer | Yamagata University | Bayer Pharma AG | Pfizer | Pfizer | Novartis | Aveo Oncology and Astellas | |

Abbreviations: AE = adverse event; AX = axitinib; CI = confidence interval; CR = complete response; ECOG PS = Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; DOV = dovitinib; HFSR = hand-foot skin reaction; HR = hazard ratio; MSKCC = Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center; NR = not reported; OS = overall survival; PFS = progression-free survival; PR = partial response; SAE = serious adverse event; SD = stable disease; SOR = sorafenib; SU = sunitinib; TEM = temsirolimus; TIV = tivozanib.

a Data reported only for first-line sorafenib.

b Unless otherwise noted, baseline characteristics refer to the overall SU-SO population at study entry (n = 176); characteristics of patients who crossed over are NR

c Except adjuvant IFNa.

d 1-sided CI.

e HR for progression of death.

f Occurring in >20% of patients in any phase 3 study.

g Data missing for 1 pt.

h Reported as grade ≥3.

i Data missing for 5 pts.

j 18 (7%) had normal thyroid-stimulating hormone levels prior to dosing that increased to >10 IU/mL after treatment; 5 (2%) had low T3 and 2 (1%) had low T4 on or after the date that the increases in thyroid-stimulating hormone were observed.

Table 3. Phase 2 trials of sorafenib in RCC published following the TARGET trial.

| NCT00467025 [25] | NCT00126594 [26] | NCT00117637 [27] | NCT00609401ROSORC [28–30] | NCT00618982 [31,32] | NCT00866320 [33] | NCT00079612 [34] | NCT00661375/ NCT00586495 (extension study) [35] | [36] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Line of therapy | 1st | 1st | 1st | 1st | 1st | ≥2nd | ≥2nd a | ≥2nd | ≥2nd |

| Trial design | Randomized double blind: AMG 386 + sorafenib vs sorafenib + placebo | Randomized open label: sorafenib vs sorafenib + low dose interferon-alpha | Randomized open-label: sorafenib vs interferon-alpha | Randomized open label: sorafenib + interleukin-2 vs sorafenib | Single arm: dose escalation | Single arm: sorafenib in sunitinib or bevacizumab refractory patients | Randomized discontinuation: sorafenib vs placebo in patients refractory to approved therapies | Single arm: sorafenib in patients with nephrectomy and failed cytokine therapy | Single-arm: sorafenib after interleukin-2 + interferon-alpha |

| N | 152 | 80 | 189 | 128 | 83 | 47 | 202 | 131 | 41 |

| Sorafenib arm, n efficacy | 51 | 40 | 97 | 62 | 67 | 47 | 32 | 129 | 36 b |

| Sorafenib arm, n safety | 50 | 40 | 97 | 62 | 83 | 47 | 202 | 131 | 38 |

| Previous systemic therapy, n (%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 47 (100) | 29 (91) | 129 (100) | 38 (100) |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 47 (100) | NR | 46 (36) | 0 |

| >1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 23 (49) | NR | 83 (64) | 0 |

| Nephrectomy, n (%) | NR | 40 (100) | 95 (98) | 46 (74) | NR | 44 (94) | 29 (91) | 129 (100) | 35 (85) |

| Efficacy | |||||||||

| OS, months (95% CI) | 27.1 (19.7-NE d ) | NE e | NR | 33 (16–43) | NR | 16.0 (7.6–32.2) | NR | 25.3 (19.0–32.0) | 16.6 (NE) |

| PFS, months (95% CI) | 9.0 (5.5–10.9) | 7.4 (5.5–9.2) | 5.7 (5.0–7.4) | 6.9 (3.5–15) | 7.4 (6.3–9.7) | 4.4 (3.6–5.9) | 5.5 | 7.9 (6.4–10.8) | 7.4 (6.5–13.1) |

| Response rate, (%) [95% CI] | (25)[14–40] | (30) [16.6–46.5] | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | (19) [13–27] | 44 [NR] |

| CR | 1(2) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | NR | 0 | 0 (0) | NR | 0 (0) | 3 (8) |

| PR | 12 (24) | 11 (28) | 5 (5) | 9 (15) | 12 (18) | 1 (2) f | NR | 25 (19) | 13 (36) |

| SD | 30 (59) | 17 (43) | 72 (74) | 27 (60) | 46 (69) | 20 (43) | NR | 87 (67) | 18 (50) |

| Safety | |||||||||

| Treatment-emergent AEs, n (%) | 50 (100) | NR | 92 (95) g | NR | 80 (96) | NR | 202 (100) c | 127 (97) g | NR |

| Grade 3 or 4 | 43 (86) h , i | NR | 40 (41) g , h | NR | NR | NR | 133 (65) | 90 (69) g | NR |

| Fatigue | 11 (22) | NR | 42(43) g | 10 (16) | 45 (54) | 26 (58) g | 147 (73) | 22 (17) g | NR |

| Grade 3 or 4 | 0 h | 10 (25) | 5 (5) g , h | 1 (2) h | NR | 8 (18) | 13 (7) | 3 (2) g | NR |

| HFSR | 27 (54) | NR | 58 (60) g | 32 (52) | 54 (65) | 31 (79) | 125 (62) | 76 (58) g | 19 (46) |

| Grade 3 | 14 (28) h | 10 (25) | 11 (11) g , h | 6 (10) h | NR | 14 (31) | 27 (13) | 12 (9) g | 0 |

| Rash or desquamation | 15 (30) | NR | 40(41) g | NR | 46 (55) | 14 (31) | 134 (66) | 54 (41) g | NR |

| Grade 3 or 4 | 4 (8) h | 2 (5) | 6 (6) g , h | NR | NR | 3 (7) | 5 (2) | 5 (4) g | NR |

| Diarrhea | 28 (56) | NR | 53 (55) g | 17 (27) | 53 (64) | 27 (60) | 117 (58) | 56 (43) g | 20 (49) |

| Grade 3 or 4 | 4 (8) h | 13 (33) | 6 (6) g , h | 0 | NR | 4 (9) | 8 (4) | 7 (5) g | 2 (5) |

| Hypertension | 23 (46) | NR | 22 (23) g | 10 (16) | 40 (48) | 16 (36) | 86 (43) | 43 (33) g | 15 (37) |

| Grade 3 or 4 | 7 (14) h | 2 (5) | 2 (2) g , h | 4 (6) h | NR | 4 (9) | 62 (31) | 22 (17) g | 0 |

| Additional references | [37] | [38–40] | [41–44] | [45–48] | [49,50] | [49–55] | [56] | ||

| Funding | Amgen Incorporated | NCI's Cancer Therapy Evaluation Program | Bayer Healthcare Pharma-ceuticals | Funded in part by Bayer HealthCare | Funded in part by Bayer HealthCare | Bayer, Onyx | Bayer, Onyx | Bayer | Bayer Hispania S.L. |

Abbreviations: AE = adverse event; CI = confidence interval; CR = complete response; HFSR = hand foot skin reaction; NE = estimable; NR = not reported; OS = overall survival; PFS = progression-free survival; PR = partial response; SD = stable disease.

a NR for 3 patients.

b Tumor assessment was not possible in five patients and they were excluded from the efficacy analysis.

c Treatment emergent AEs were reported for the total 202 patients, which included both patients randomized to the sorafenib and to the placebo arm after a 12 week run-in period of sorafenib treatment.

d Interim analysis.

e Median overall survival was not reached.

f Unconfirmed.

g All reported AEs were considered treatment related.

h Grade ≥3.

i Including 2 grade 5.

Table 4. Additional small trials and patient series in RCC published since the TARGET trial.

| Reference | Hermann et al 2008 [57] | Zhang et al 2009 [58] | Imarisio et al 2012 [59] | NCT00586105 [60] | Yang et al 2012 [61] | Sun et al 2008 [62] | Kapoor et al 2008 [63] | Battglia et al 2009; Gernone et al 2009 [64,65] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Line of therapy | ≥2nd | 2nd a | NR | NR | 1st or ≥2nd | ≥2nd | NR | ≥2nd |

| Trial design | Patient series | Patient series b | Patient series | Single-arm | Single-arm | Single-arm | Single-arm | Single-arm |

| N | 40 | 98 | 80 | 39 | 30 | 62 | 21 | 22 |

| Sorafenib arm, n efficacy | 20 | 39 c | 33 d | 39 | 30 | 62 | 21 | 20 |

| Sorafenib arm, n safety | 20 | 39 b | 33 | 39 | 30 | 62 | 21 | 22 |

| Prior treatments, n (%) | ||||||||

| Prior systemic therapy | 40 (100) | NR a | NR | NR | 13 (43) | 62 (100) | NR | 22 (100) |

| Nephrectomy | 19 (95) | 91 (93) | NR | NR | 27 (90) | 43 (85) | 11 (52) | 21 (96) |

| Efficacy | ||||||||

| OS, months (95% CI) | NR | NR e | NR | 7.8 (0.9–13.4) | 16 (10.2–21.8) | NR f | NR | NR |

| PFS, months (95% CI) | 6.4 (NR) | NR e | NR | 5.5 (4.1–7.8) | 14 (0–31.7) | 9.5 (NR) | 8.4 (1.2–59) g | NR |

| Response rate, n (%) | ||||||||

| CR | 0 | NR e | NR | 0 | 1 (3) | 1 (2) | NR | 0 |

| PR | 2 (10) | NR e | NR | 5 (13) | 4 (13) | 11 (18) | NR | 13 (59) |

| SD | 14 (60) | NR | NR | 27 (69) | 19 (63) | 36 (53) | NR | 7 (31) |

| Safety, n(%) | ||||||||

| Treatment-emergent AEs | NR | NR | NR | 39 (100) | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Grade 3 or 4 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Fatigue | 10 (50) | 30 (77) h | 16 (48) | 12 (31) | 5 (17) | NR | NR | NR |

| Grade 3 or 4 | 1 (5) | 2 (5) | 4 (12) | NR | 0 | NR | NR | 6 (27) |

| HFSR | 8 (40) | 21 (54) h | 10 (30) | 25 (64) | 18 (60) | NR | NR | NR |

| Grade 3 | 3 (15) | 5 (13) | 2 (6) | NR | 8 (27) | 10 (16) | NR | 5 (22) |

| Rash or desquamation | 8 (40) | 11 (28) h | 4 (12) | 9 (23) | 9 (30) | NR | NR | NR |

| Grade 3 or 4 | 3 (15) | 0 | 1 (3) | NR | 1 (3) | NR | NR | 4 (18) |

| Diarrhea | 11 (55) | 16 (41) h | 9 (27) | 14 (36) | 10 (33) | NR | NR | NR |

| Grade 3 or 4 | 2 (10) | 0 | 3 (9) | NR | 1 (3) | 3 (5) | NR | 2 (9) |

| Hypertension | 6 (30) | 7 (18) h | 3 (9) | 7 (18) | 9 (30) | NR | NR | NR |

| Grade 3 or 4 | 2 (10) | 1 (<1) | 3 (9) | NR | 1 (3) | 2 (3) | NR | 3 (13) |

| Additional references identified | [66] | [67] | ||||||

| Funding | NR | NR | NR | Bayer HealthCare | China Charity Federation | NR | NR | NR |

Abbreviations: AE = adverse event; CI = confidence interval; CR = complete response; HFSR = hand foot skin reaction; NR = not reported; OS = overall survival; PFS = progression-free survival; PR = partial response; SD = stable disease.

a All 39 pts for which results are posted received 2nd-line sorafenib.

b Patients received either 1st-line sorafenib (n = 43), 1st-line sorafenib + IFN (n = 16), or 2nd-line sorafenib (n = 39).

c Population who received 2nd-line sorafenib.

d Subset of pts with RCC.

e Results not reported individually for pts receiving single-agent sorafenib.

f Not reached after 278 days mean follow-up.

g Median (range).

h Grade 1–2.

Results

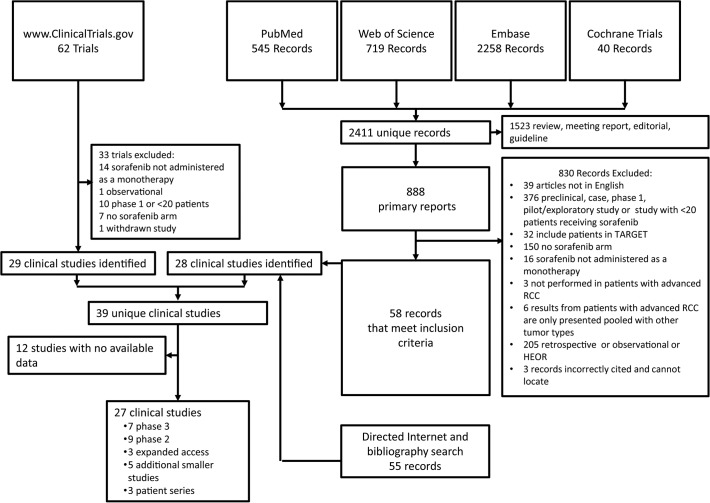

Fig. 1 depicts the flow of information informing the selection of clinical studies reviewed. A total of 2411 publications were identified in searches of PubMed, ISI Web of Science, Embase, and Cochrane Library databases. Among these, 888 were primary data reports. Fifty-eight records identified through these databases met inclusion criteria. An additional 55 records meeting inclusion criteria were identified through directed searching of the Internet or bibliographies of review articles. Collectively, these publications identified 28 clinical studies (27 from database searches and 1 from directed searching). An additional 11 clinical studies were identified by searching www.ClinicalTrials.gov. Thirty of the resulting 39 unique identified studies had available results.

Fig 1. Flow of information.

Selection process for included trials.

Phase 3 and expanded access trials

Eleven randomized controlled phase 3 trials of sorafenib in RCC have been undertaken since the TARGET trial. Three studies were excluded from this review because data are not yet available (expected in 2016) [104–107]. One additional trial was identified as a phase 3 trial, but it enrolled only 39 patients and was not a controlled trial [60]. Results for this trial are therefore considered below in the context of other small trials and are included in Table 4.

Results for the seven eligible phase 3 trials are shown in Table 2 [68–103]. Among these trials, patient age, gender, and ECOG PS were similar to those in the TARGET trial. Likewise, the predominant histology was clear cell type and most patients had undergone prior nephrectomy. However, MSKCC scores were considerably more heterogeneous. With the exception of AGILE 1051, all of the trials included a higher proportion of patients with intermediate or poor status than were included in TARGET (48%). MSKCC scores were also substantially worse in the expanded access AUS1 trial (Table 1) (not reported for EU-ARCCS and NA-ARCCS). Similar to TARGET, in which 98% of patients had ECOG PS ≤1, all patients in the phase 3 trials had ECOG PS ≤1 (where reported). In contrast, patients with ECOG PS 2 or higher were included in the EU-ARCCS and AUS-1 expanded access trials. Race was inconsistently reported, and no trial reported inclusion of more than 25% Asians.

In addition, phase 3 trials varied with respect to the number of prior systemic treatments administered. In TARGET, all patients’ tumors had progressed after one systemic treatment [1]. Sorafenib was also studied in the second-line in AXIS and INTORSECT. In AXIS 35% of patients had received prior cytokine treatment, 54% received prior sunitinib, 8% received prior bevacizumab, and 3% received prior temsirolimus treatment [74]. In INTORSECT, all patients received prior sunitinib treatment [76]. Two phase 3 trials, CROSS-J-RCC and SWITCH, examined sequential treatment approaches in which sorafenib was used following progression on first-line sunitinib and vice versa. For these trials, data were collected for both first- and second-line treatment, although data are not yet available for second-line treatment in CROSS-J-RCC [71,75]. In GOLD-RCC, patients received sorafenib third-line after disease progression on or within 6 months of the most recent of two prior therapies including one VEGF inhibitor and one mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitor [77,82,83]. In one of the phase 3 trials, all patients were treatment naive [68,69]. Finally, in the TIVO-1 trial, the patient populations were mixed with respect to the line of therapy [78–82].

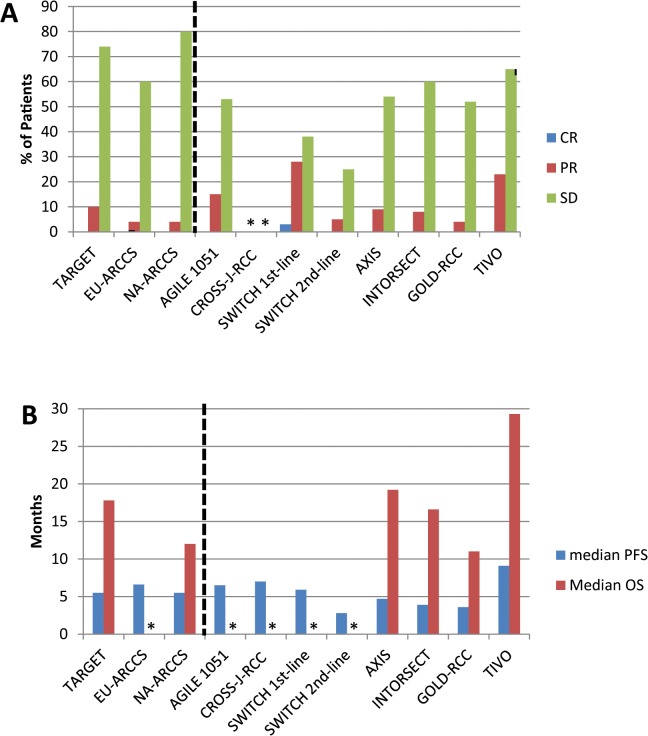

Median PFS ranged from 5.9 to 7.0 months in patients treated with first-line sorafenib (N = 341) [68–71]. In patients treated with second-line sorafenib (N = 691), PFS (95% CI) associated with sorafenib treatment ranged from 2.8 (not reported) to 4.7 (4.6–5.6) months [71–76]. In the third-line setting (N = 286), PFS (95% CI) was 3.6 (3.5–3.7) months [77]. Median PFS and OS for each of the phase 3 trials are represented graphically in Fig. 2, along with results from TARGET, EU-ARCCS, and NA-ARCCS.

Fig 2. Sorafenib response rates, PFS, and OS in TARGET, associated expanded access trials, and subsequent phase 3 trials.

A) Response rates. B) Median PFS and OS. Data for trials including patients for whom sorafenib was used ≥second line are indicated by stippling. *Data were not reported.

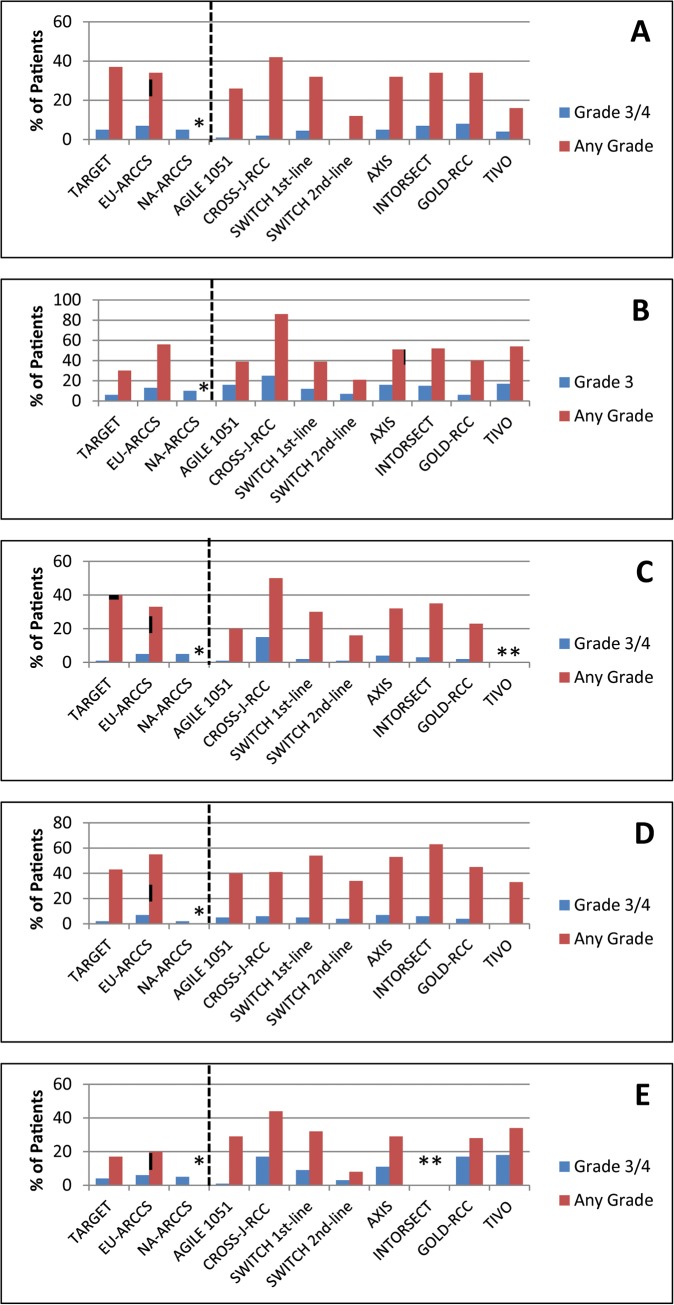

Where reported, treatment-emergent AEs occurred in nearly all patients, and grade 3/4 AEs were seen in 36%-70%. Overall incidences of AEs by line of treatment are difficult to evaluate because data have not been reported for four of the seven trials. The incidences of serious AEs was reported for three trials and ranged from 25%-34%. Frequencies of select AEs occurring in >20% of patients in any phase 3 trial are detailed in Table 2. Fatigue, hand-foot skin reaction (HFSR), rash or desquamation, diarrhea, and hypertension were among the most frequent AEs. Incidences of these AEs are presented graphically in Fig. 3 [68–103].

Fig 3. Incidences of select adverse events in TARGET, associated expanded access trials, and subsequent phase 3 trials.

A) Fatigue; B) HFSR; C) Rash, desquamation; D) Diarrhea; E) Hypertension. Data for trials including patients for whom sorafenib was used ≥second-line are indicated by stippling. *Data were not reported.

Phase 2 trials

Published data were identified for a heterogeneous group of nine phase 2 trials that met eligibility criteria for this review (Table 3). First-line sorafenib was used in three randomized, open-label studies [25–30]. Median PFS (95% CI) ranged from 5.7 (5.0–7.4) to 9.0 (5.5–10.9) months. In a single-arm dose-escalation study in the first-line setting, patients received 400 mg twice daily (BID) for 4 weeks, and escalated to 600 mg BID for 4 weeks and finally to 800 mg BID, with response evaluated at 6 months. The dose-escalation protocol was tolerated by 18/67 patients [31,32]. The remaining patients had dose escalations and reductions as tolerated throughout the study. Overall median PFS (95% CI) was 7.4 (6.3–9.7) months. Subgroup analysis by dose (400, 600, or 800 mg BID) administered to patients for the longest duration showed median PFS (95% CI) of 3.7 (1.8–9.5), 7.4 (6.3–12) and 8.5 (5.6–14.9) months, respectively [32].

In three phase 2 trials, sorafenib was evaluated as second-line or later therapy in patients who had failed or progressed after cytokine therapy [35,36] or in patients refractory to sunitinib or bevacizumab [33] (Table 3).

One study [34] was a randomized, discontinuation trial in which patients with tumor growth or <25% tumor shrinkage during a 12-week run-in period of sorafenib treatment were randomized to receive continued sorafenib or placebo. Thirty-two patients received continued sorafenib; efficacy results are presented only for these patients. Safety results are presented for the entire enrolled population (N = 202), 91% of whom received prior interleukin (IL)-2, interferon, or nonspecified systemic anticancer therapy. Median PFS (95% CI) was, respectively, 4.4 (3.6–5.9) and 5.5 (not reported) months in patients (N = 79) previously treated with VEGF inhibitors [33,34], and 7.4 (6.5–13.1) and 7.9 (6.4–10.8) months in patients (N = 165) previously treated with cytokine therapy [35,36]. It should be noted that this particular study technically met inclusion criteria for this systematic review because it was published in 2006. However, efficacy data are reported only up to December 31, 2004.

Overall incidences of treatment-emergent AEs were not consistently reported, but ranged from 96%-100% where data are available [31,34,37]. Incidences of treatment-related AEs, where reported, ranged from 95%-97%, and grade 3/4 treatment-related AEs in the same studies ranged from 41%-69% [27,35]. Frequencies of the most common specific AEs are detailed in Table 3.

Smaller studies and patient series

In addition to phase 2, phase 3, and expanded access trials, five small single-arm studies and three patient series reports were identified. Results for these studies are reported in Table 4. As mentioned above, one trial was listed as a phase 3 trial, but because it was not a randomized controlled trial and because only 39 patients were enrolled, it is included with this, more similar group of studies [60]. Notably, in two of the single-arm trials, median PFS [95% CI] was considerably longer than was seen in any of the phase 2/3 trials (9.5 [not reported] and 14 [0–31.7] months) [61,62]. These two studies were undertaken entirely in Chinese patients and 91% of the patients had received at least one prior systemic therapy.

Discussion

Generally when a drug is demonstrated to have clinical utility and becomes approved for use, results from a pivotal phase 3 trial, and potentially one or a few earlier phase 2 studies, comprise the body of experience in terms of disease response and management of side effects. These studies therefore have a profound effect on drug labeling and its uptake and use in the community. Over time, clinical experience in management of dose- and course- limiting acute and chronic side effects typically matures, with positive impacts for both the patient experience and disease outcomes. However, information on the collective experience may not be readily available to the practitioner.

Sorafenib was approved for the treatment of RCC in 2005 after favorable PFS results were obtained in the pivotal TARGET trial. Since that time, a large number of studies using sorafenib in RCC therapy have been undertaken. The number of publications initially identified (2411) represents a dauntingly broad experience. The availability of published data from these studies provides an important opportunity to comprehensively evaluate how the safety and efficacy experience with this drug may have evolved. To that end, we have systematically reviewed the published literature for clinical studies conducted since 2005 that included the use of single-agent sorafenib for RCC.

In all, we identified 30 studies in which 2182 patients were treated with sorafenib. Among these, 1575 were treated in randomized controlled phase 3 trials. It is important to note that even among phase 3 trials, comparisons with TARGET should be undertaken with caution. Differences in trial design, patient baseline characteristics (including proportion of patients with higher-risk characteristics) duration of treatment and follow-up and reported endpoints have precluded quantitative comparisons or meta-analysis. There is no comprehensive patient-level database that spans those experiences, and no practical way to re-analyze response or toxicity assessments.

Whereas TARGET was a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, all of the phase 3 trials (Table 2) identified in this review were open-label studies where the comparator arm was another targeted agent. Overall survival was the primary end-point in TARGET and PFS was the primary endpoint in the other seven phase 3 trials. Although it is not the intent of this review to provide a comparison with other agents, it is interesting to note that where reported, OS in sorafenib- treated patients was either similar to[58,61,86], or superior to[80][1] comparator agents.

Among the identified trials, patients differed with respect to baseline characteristics, perhaps most profoundly by MSKCC score and line of treatment. A recent retrospective review of control (comparator) arm data derived from clinical trials in RCC suggests that the characteristics of RCC patients at baseline have consistently improved over time and proposes that these differences may result from increased use of palliative nephrectomy, advances in surgical techniques, and earlier diagnosis [108]. The diversity of reported trial designs reflects not only evolving approaches in standard of care for RCC, but also the desire to further evaluate the role of sequential treatment for patients whose disease progresses during treatment with targeted agents that were unavailable at the time sorafenib was approved.

In the TARGET trial, patients’ tumors must have progressed after one systemic treatment within the previous 8 months. Sorafenib was used exclusively second-line for three other phase 3 trials. In contrast to TARGET, prior treatment in these trials consisted largely, if not entirely, of targeted non-cytokine therapies. As summarized in Table 2 and Fig. 2, patients treated in the second-line setting appeared to have shorter PFS than in the 3 trials where patients were treated first-line with sorafenib, a finding that is in keeping with the trend towards poorer MSKCC score in the second-line trials. While the major impacts of risk-group, disease features, and line-of-treatment preclude a quantitative comparison, more contemporary data are generally similar to that seen in TARGET.

Disappointingly, safety data were inconsistently reported among the trials. Overall incidences of AEs were reported for five of the seven phase 3 trials included; Serious AEs were reported for only three studies. Incidences of grade 3/4 AEs varied substantially. In TARGET, overall incidences of AEs were reported only if they were considered treatment related. These and other factors, such as differing duration of treatment, preclude a meta-analysis with statistical characterization trends.

Specific treatment-emergent AEs reported in all phase 3 trials included in this review were largely similar to TARGET. However, whereas grade 3 HFSR was observed in 6% of patients in TARGET [1], it was reported in ≥15% patients in five of the more recent phase 3 trials [68,70,74,76,78,79,83]. Similarly, grade 3/4 hypertension occurred in 4% of patients in TARGET [1] and in 11%-18% in four of the more recent trials [70,74,75,77–79,103] (Fig. 3). One may speculate that some practice-related factors may be responsible for this. In more recent trials, increased familiarity with the use of sorafenib and its side effects may have reduced the frequencies of dose interruptions and reductions, resulting in overall higher dose intensity over the course of treatment. However, due to inconsistent reporting of dose intensities, this notion cannot be substantiated based on the reported data. As a bottom line for the clinician, the HSFR and hypertension issues seem more frequent in the current experience—an active management plan to mitigate remains an ongoing consideration.

Higher incidences of grade 3 HFSR and grade ≥3 hypertension were also reported in several of the phase 2 trials, although qualitative differences (treatment-emergent vs treatment-related AEs) and inconsistent reporting preclude determining the number of trials in which these occurred. Even with these rather small differences, it appears that the safety profile of sorafenib observed in the variety of patient populations and treatment settings studied is consistent with that observed in the TARGET trial, with no new signals.

For comprehensiveness, we included phase 2 and smaller trials in this review. Five of the phase 2 trials were randomized, and the remaining studies, including smaller trials and patient series listed in Table 4, were single arm. In addition to the limitations discussed above for the phase 3 trials, inherent potential bias in these trials should be considered when interpreting the results. Nonetheless, these trials may offer important insights. However, it is important to note that results reported for all of these studies may differ from those observed in daily clinical practice. Similarly, trends or absence of changes in reported prospective trials are not conclusively demonstrative of changes in daily clinical practice.

For example, among the seven phase 3 trials included in this review, none enrolled more than 25% of Asian patients. One phase 2 trial [35] enrolled exclusively Japanese patients and two smaller trials [61,62] and a patient series [58] report results in Chinese patients. PFS in these studies appeared longer than in TARGET or any other trial reported here (single-agent sorafenib results were not reported for the patient series). Yang et al. considered ethnic background as an important factor leading to these differences [61]. However, disease control rates and OS (where reported) did not show corresponding differences. These studies in Asian patients enrolled fewer than 100 patients each and did not include a control (non-Asian) population; additional studies would be necessary to clarify these findings. Incidences of AEs in Asian patients were similar to those observed in TARGET with the exception that grade 3 HFSR was higher in the smaller studies (Table 4), and treatment-related grade 3/4 hypertension was seen in 17% of patients in the phase 2 trial (Table 3). Understanding how ethnic features affect sorafenib efficacy or side effects remains a challenge.

In this review, we have comprehensively collected publications that describe the use of single-agent sorafenib in prospective studies in patients with RCC. The data are focused on the sorafenib experience, rather than comparative efficacy, with the goal of obtaining a broadened perspective on what to expect as medical practices evolve, beyond the database of the original pivotal trial. While the randomized controlled phase 3 trials likely provide the most robust information, important additional information may be gleaned from the inclusion of phase 2 and smaller studies, particularly as they may provide historical context or describe less well-represented populations. Comparisons among the included trials should be made with due caution as study design, patient populations, tumor characteristics, and prior drug exposure vary dramatically. Differences of patient characteristics a priori may be more important than differences of treatment plans. Notwithstanding the diversity of trial designs in this review, in examining the primary endpoints of this study, PFS and safety, we have observed no profound differences from the results observed in TARGET.

Supporting Information

(DOC)

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

Support for this manuscript was provided by Onyx Pharmaceuticals, an Amgen subsidiary. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. Pamela Foreman and Jin Tomshine are employees of Blue Ocean Pharma LLC, which provided support in the form of salaries, but did not have any additional role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. The specific roles of these authors are articulated in the ‘author contributions’ section.

References

- 1. Escudier B, Eisen T, Stadler WM, Szczylik C, Oudard S, Siebels M, et al. Sorafenib in advanced clear-cell renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2007;356: 125–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Beck J, Procopio G, Bajetta E, Keilholz U, Negrier S, Szczylik C, et al. Final results of the European Advanced Renal Cell Carcinoma Sorafenib (EU-ARCCS) expanded-access study: a large open-label study in diverse community settings. Ann Oncol. 2011;22: 1812–1823. 10.1093/annonc/mdq651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Stadler WM, Figlin RA, McDermott DF, Dutcher JP, Knox JJ, Miller WH Jr., et al. Safety and efficacy results of the advanced renal cell carcinoma sorafenib expanded access program in North America. Cancer. 2010;116: 1272–1280. 10.1002/cncr.24864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Tafreshi A, Thientosapol E, Liew MS, Guo Y, Quaggiotto M, Boyer M, et al. Efficacy of sorafenib in advanced renal cell carcinoma independent of prior treatment, histology or prognostic group. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol. 2014;10: 60–65. 10.1111/ajco.12122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Beck J, Bajetta E, Escudier B, Negrier S, Keilholz U, Szczylik C, et al. A large open-label, non-comparative, phase III study of the multi-targeted kinase inhibitor sorafenib in European patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma. Eur J Cancer Suppl. 2007;5: 300: abstract 4506. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Beck J, Procopio G, Verzoni E, Negrier S, Keilholz U, Szczylik C, et al. Large open-label, non-comparative, clinical experience trial of the multi-targeted kinase inhibitor sorafenib in European patients with advanced RCC. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26: abstract 16021. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Beck J, Procopio I, Negrier S, Keilholz D, Sczylik C, Bokemeyer C, et al. Final analysis of a large open-label, noncomparative, phase 3 study of sorafenib in European patients with advanced RCC (EU-ARCCS). Eur J Cancer Suppl. 2009;7: 434–435: abstract 7137. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Beck J, Verzoni E, Negrier S, Keilholz U, Szczylik C, Bracarda S, et al. A large open-label, non-comparative, phase III study of the multi-targeted kinase inhibitor sorafenib in European patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma. Eur Urol Suppl. 2008;7: 244: abstract 694. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bokemeyer C, Gore M, Bracarda I, Richel N, Staehler D, von der Maase H, et al. Safety and efficacy of sorafenib in patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma (RCC) with varying histologies: results from the phase 3, open access study of sorafenib in European patients with advanced RCC (EU-ARCCS). Eur J Cancer Suppl. 2009;7: 433: abstract 7132. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bokemeyer C, Porta C, Beck J, Ne´grier S, Richel DJ, Strauss UP, et al. Efficacy and safety of sorafenib in pts with brain and bone metastases: results from a large open-label, non-comparative phase III study of sorafenib in European pts with advanced RCC (EU-ARCCS). Ann Oncol. 2008;19(suppl 8): viii123–viii124: abstract 259P. 10.1093/annonc/mdn570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bracarda S, Procopio G, Keilholz U, Negrier SG, Szczylik C, Beck J, et al. Elderly patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma (RCC) successfully treated. Eur Urol Suppl. 2009;8: 156: abstract 142. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Eisen T, Beck J, Procopio G, Ne´grier S, Keilholz U, von der Maase H, et al. Large open-label, non-comparative phase III study of sorafenib in European pts with advanced RCC (EU-ARCCS)—subgroup analysis of pts with and without baseline clinical cardiovascular diseases (CCD). Ann Oncol. 2008;19(suppl 8): viii194–viii195: abstract 602P. 10.1093/annonc/mdn570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Porta C, Bracarda S, Beck J, Procopio G, Staehler M, Strauss UP, et al. Efficacy and safety of sorafenib in elderly pts: results from a large, open-label, non-comparative phase III study in European pts with advanced RCC (EU-ARCCS). Ann Oncol. 2008;19(suppl 8): viii193: abstract 596P. 10.1093/annonc/mdn570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Procopio G, Verzoni E, Gevorgyan A, Mancin M, Pusceddu S, Catena L, et al. Safety and activity of sorafenib in different histotypes of advanced renal cell carcinoma. Oncology. 2007;73: 204–209. 10.1159/000127387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Staehler M, Procopio G, Keilholz U, Negrier S, Szczylik C, Beck J, et al. A subanalysis of patients with and without prior nephrectomy in a large open-label, non-comparative phase 3 European advanced renal cell carcinoma (RCC) sorafenib study (EU-ARCCS). Eur Urol Suppl. 2009;8: 184: abstract 254. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bukowski R, Figlin R, Stadler W. Safety analysis of the advanced renal cell carcinoma sorafenib (ARCCS) study, an expanded access program. Eur Urol Suppl. 2007;6: 237:abstract 858. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bukowski RM, Stadler WM, Figlin RA, Knox JJ, Gabrail N, McDermott DF, et al. Safety and efficacy of sorafenib in elderly patients (pts) ≥65 years: A subset analysis from the Advanced Renal Cell Carcinoma Sorafenib (ARCCS) Expanded Access Program in North America. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(15 suppl): abstract 5045. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bukowski RM, Stadler WM, McDermott DF, Dutcher JP, Knox JJ, Miller WH Jr., et al. Safety and efficacy of sorafenib in elderly patients treated in the North American advanced renal cell carcinoma sorafenib expanded access program. Oncology. 2010;78: 340–347. 10.1159/000320223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bukowski RM, Wood LS, Knox JJ, Stadler WM, Figlin RA. The incidence and severity of hand-foot skin reaction: a subset analysis from the advanced renal cell carcinoma sorafenib expanded access program in North America. Ann Oncol. 2008;19(suppl 8): viii195: abstract 604P. 10.1093/annonc/mdn570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Henderson CA, Bukowski RM, Stadler WM, Dutcher JP, Kindwall-Keller TL, Hotte SJ, et al. Sorafenib therapy in the management of advanced renal cell carcinoma with brain metastases: results from the ARCCS expanded access program. Eur Urol Suppl. 2008;7: 245. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Knox JJ, Figlin RA, Stadler WM, McDermott DF, Gabrail N, Miller WH, et al. The Advanced Renal Cell Carcinoma Sorafenib (ARCCS) expanded access trial in North America: safety and efficacy. J Clin Oncol. 2007;2518(suppl): abstract 5011. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Tafreshi A, Thientosapol E, Liew MS, Guo Y, Quaggiotto M, Boyer M, et al. Efficacy of sorafenib in advanced renal cell carcinoma independent of prior treatment, histology or prognostic group. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol. 2012;8(suppl 2): 57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tafreshi A, Thientosapol E, Liew MS, Guo Y, Quaggiotto M, Boyer M, et al. Efficacy of sorafenib in advanced renal cell carcinoma (RCC) independent of prior treatment, histology or prognostic group. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol. 2012;8(suppl 3): 162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tafreshi l, Thientosapol E, Liew MS, Guo Y, Quaggiotto M, Boyer MJ, et al. Efficacy of sorafenib in advanced renal cell carcinoma (RCC) independent of prior treatment, histology, or prognostic group. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(suppl 6): abstract 465^. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Rini B, Szczylik C, Tannir NM, Koralewski P, Tomczak P, Deptala A, et al. AMG 386 in combination with sorafenib in patients with metastatic clear cell carcinoma of the kidney: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2 study. Cancer. 2012;118: 6152–6161. 10.1002/cncr.27632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Jonasch E, Corn P, Pagliaro LC, Warneke CL, Johnson MM, Tamboli P, et al. Upfront, randomized, phase 2 trial of sorafenib versus sorafenib and low-dose interferon alfa in patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma: clinical and biomarker analysis. Cancer. 2010;116: 57–65. 10.1002/cncr.24685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Escudier B, Szczylik C, Hutson TE, Demkow T, Staehler M, Rolland F, et al. Randomized phase II trial of first-line treatment with sorafenib versus interferon Alfa-2a in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. (Erratum in J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2305.). J Clin Oncol. 2009;27: 1280–1289. 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.3342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Procopio G, Verzoni E, Bracarda S, Ricci S, Miceli R, Bertolini A, et al. A randomized, prospective, phase 2 study, with sorafenib (So) and interleukin-2 (IL-2) versus So alone as first line treatment in advanced renal cell cancer (RCC): ROSORC Trial. Eur J Cancer Suppl. 2009;7: 425: abstract 7107. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Procopio G, Verzoni E, Bracarda S, Ricci S, Sacco C, Ridolfi L, et al. Sorafenib with interleukin-2 vs sorafenib alone in metastatic renal cell carcinoma: the ROSORC trial. Br J Cancer. 2011;104: 1256–1261. 10.1038/bjc.2011.103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Procopio G, Verzoni E, Bracarda S, Ricci S, Sacco C, Ridolfi L, et al. Overall survival for sorafenib plus interleukin-2 compared with sorafenib alone in metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC): final results of the ROSORC trial. Ann Oncol. 2013;24: 2967–2971. 10.1093/annonc/mdt375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bayer. Sorafenib dose escalation in renal cell carcinoma. Available: http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/results/NCT00618982. Accessed 2015 March 3.

- 32. Gore ME, Jones RJ, Ravaud A, Kuczyk M, Demkow T, Bearz A, et al. Efficacy and safety of intrapatient dose escalation of sorafenib as first-line treatment for metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC). J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(15 suppl): abstract 4609. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Garcia JA, Hutson TE, Elson P, Cowey CL, Gilligan T, Nemec C, et al. Sorafenib in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma refractory to either sunitinib or bevacizumab. Cancer. 2010;116: 5383–5390. 10.1002/cncr.25327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ratain MJ, Eisen T, Stadler WM, Flaherty KT, Kaye SB, Rosner GL, et al. Phase II placebo-controlled randomized discontinuation trial of sorafenib in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24: 2505–2512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Naito S, Tsukamoto T, Murai M, Fukino K, Akaza H. Overall survival and good tolerability of long-term use of sorafenib after cytokine treatment: final results of a phase II trial of sorafenib in Japanese patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. BJU Int. 2011;108: 1813–1819. 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2011.10281.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Maroto JP, del Muro XG, Mellado B, Perez-Gracia JL, Andres R, Cruz J, et al. Phase II trial of sequential subcutaneous interleukin-2 plus interferon alpha followed by sorafenib in renal cell carcinoma (RCC). Clin Transl Oncol. 2013;15: 698–704. 10.1007/s12094-012-0991-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Rini BI, Szczylik C, Tannir NM, Koralewski P, Tomczak P, Deptala A, et al. AMG 386 in combination with sorafenib in patients (pts) with metastatic renal cell cancer (mRCC): A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase II study. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(suppl 7): abstract 309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Jonasch E, Corn P, Ashe RG, Do K, Tannir NM. Randomized phase II study of sorafenib with or without low-dose IFN in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(18 suppl): abstract 5104. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Tannir NM, Zurita AJ, Heymach JV, Tran HT, Pagliaro LC, Corn P, et al. A randomized phase II trial of sorafenib versus sorafenib plus low-dose interferon-alfa: Clinical results and biomarker analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(15 suppl): abstract 5093. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Zurita AJ, Jonasch E, Wang X, Khajavi M, Yan S, Du DZ, et al. A cytokine and angiogenic factor (CAF) analysis in plasma for selection of sorafenib therapy in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Ann Oncol. 2012;23: 46–52. 10.1093/annonc/mdr047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bayer BAY43-9006 (sorafenib) versus interferon alpha-2a in patients with unresectable and/or metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Available: http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/results/NCT00117637. Accessed 2015 March 3.

- 42. Escudier B, Szczylik C, Demkow T, Staehler M, Rolland F, Negrier S, et al. Randomized phase II trial of the multi-kinase inhibitor sorafenib versus interferon (IFN) in treatment-naive patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC). J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(18 suppl): abstract 4501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Escudier B, Szczylik C, Demkow T, Staehler M, Rolland F, Negrier S, et al. Phase II trial of sorafenib vs interferon in first-line patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma: results of period 1 and 2 after cross over. Ann Oncol. 2007;18(suppl 4): iv18: abstract O.203. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Szczylik C, Cella D, Eisen T, Shah S, Laferriere N, Scheuring U, et al. Comparison of kidney cancer symptoms and quality of life (QoL) in renal cell cancer (RCC) patients (pts) receiving sorafenib vs interferon-{alpha} (IFN). J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(suppl 15): abstract 9603. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Procopio G, Verzoni E, Bracarda S, Ricci S, Bregni M, Conti GN, et al. A randomized, prospective, phase 2 study, with sorafenib (S) and interleukin-2 (IL-2) versus S alone as first line treatment in advanced renal cell cancer (RCC): ROSORC trial. Ann Oncol. 2009;20(suppl 8): vii79. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Procopio G, Verzoni E, Bracarda S, Ricci S, Ridolfi L, Sacco C, et al. Overall survival (OS) of sorafenib (So) plus interleukin-2 (IL-2) versus So alone in patients with treatment-naive metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC): Final update of the ROSORC trial. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(suppl 6): abstract 356. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Procopio G, Verzoni E, Bracarda S, Ricci S, Sacco C, Ridolfi L, et al. A randomized, open label, prospective study comparing the association between sorafenib (So) and interleukin-2 (IL-2) versus So alone in advanced untreated renal cell cancer (RCC): Rosorc Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(15 suppl): abstract 5099. [Google Scholar]

- 48. Procopio G, Verzoni E, Bracarda S, Ricci S, Sacco C, Ridolfi L, et al. Subgroup analysis and updated results of the randomized study comparing sorafenib (So) plus interleukin-2 (IL-2) versus So alone as first-line treatment in metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC). J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(15 suppl): abstract 4589. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Case Comprehensive Cancer Center. Sorafenib in treating patients with metastatic kidney cancer that has not responded to sunitinib or bevacizumab. Available: http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/results/NCT00866320. Accessed 2015 March 3.

- 50. Shepard DR, Rini BI, Garcia JA, Hutson TE, Elson P, Gilligan T, et al. A multicenter prospective trial of sorafenib in patients (pts) with metastatic clear cell renal cell carcinoma (mccRCC) refractory to prior sunitinib or bevacizumab. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(15 suppl): abstract 5123. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Akaza H, Naito S, Tsukamoto T, Murai M, Fukino K. Efficacy and safety of long-term use of sorafenib: final report of a phase II trial of sorafenib in Japanese patients with unresectable/metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Eur J Cancer Suppl. 2009;7: 437–438: abstract 7147. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Akaza H, Naito S, Tsukamoto T, Nakajima K, Murai M. Uncontrolled confirmatory trial of single-agent sorafenib in Japanese patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma. Eur Urol Suppl. 2007;6: 237: abstract 859. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Akaza H, Tsukamoto T, Murai M, Nakajima K, Naito S. Phase II study to investigate the efficacy, safety, and pharmacokinetics of sorafenib in Japanese patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2007;37: 755–762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bayer. Long-term extension from RCC phase II (11515). Available: http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/results/NCT00586495. Accessed 2015 March 3.

- 55. Naito S, Tsukamoto T, Murai M, Fukino K, Nakajiima K, Akaza H. Clinical benefits of long-term use of sorafenib in Japanese patients with unresectable renal cell carcinoma (RCC). J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(15 suppl): abstract 16039. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Del Muro XG, Maroto P, Mellado B, Perez JL, Andres R, Cruz J, et al. Phase II trial of first-line sequential treatment with interleukin-2 plus interferon alfa followed by sorafenib in patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma. Ann Oncol. 2008;19(suppl 8): viii193–viii194: abstract 598P. 10.1093/annonc/mdn570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Herrmann E, Bierer S, Gerss J, Kopke T, Hertle L, Wulfing C. Prospective comparison of sorafenib and sunitinib for second-line treatment of cytokine-refractory kidney cancer patients. Oncology. 2008;74: 216–222. 10.1159/000151369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Zhang H, Dong B, Lu JJ, Yao X, Zhang S, Dai B, et al. Efficacy of sorafenib on metastatic renal cell carcinoma in Asian patients: results from a multicenter study. BMC Cancer. 2009;9: 249 10.1186/1471-2407-9-249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Imarisio I, Paglino C, Ganini C, Magnani L, Caccialanza R, Porta C. The effect of sorafenib treatment on the diabetic status of patients with renal cell or hepatocellular carcinoma. Future Oncol. 2012;8: 1051–1057. 10.2217/fon.12.74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bayer. Phase III study of sorafenib in patients wth renal cell carcinoma (RCC). Available: http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/results/NCT00586105. Accessed 2015 March 3.

- 61. Yang L, Shi L, Fu Q, Xiong H, Zhang M, Yu S. Efficacy and safety of sorafenib in advanced renal cell carcinoma patients: Results from a long-term study. Oncol Lett. 2012;3: 935–939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Sun Y, Na Y, Yu S, Zhang Y, Zhou A, Li N, et al. Sorafenib in the treatment of Chinese patients with advanced renal cell cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(15 suppl): abstract 16127. [Google Scholar]

- 63. Kapoor A, Chatterjee S, Pinthus JH, Hotte SJ, Kleinmann N. Progression free survival in patients with metastatic and recurrent renal cancer treated with sorafenib—single center experience. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(15 suppl): abstract 16141. [Google Scholar]

- 64. Battaglia M, Gernone A. Long-term use of sorafenib (SOR) in metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC) previously treated with systemic therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(suppl): abstract e16123. [Google Scholar]

- 65. Gernone A, Battaglia M, Troccoli G, Pagliarulo V. Long-term use of sorafenib (SOR) in metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC) previously treated with systemic therapy. Ann Oncol. 2009;20(suppl 8): viii84: abstract F22. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Herrmann E, Bierer S, Gerss J, Köpke T, Hertle L, Wülfing C. Comparison of sorafenib and sunitinib in cytokine refractory renal cancer patients—Which tyrosine kinase inhibitor is more effective-. Presented at Genitourinary Cancers Symposium; February 26–28, 2009; Orlando, FL. abstract 345.

- 67. Kapoor A, Chatterjee S, Pinthus JH, Hotte SJ, Kleinmann N. Progression free survival in patients with metastatic and recurrent renal cancer treated with sorafenib: single center experience. Indian J Urol. 2008: 24(suppl 22). [Google Scholar]

- 68. Hutson TE, Lesovoy V, Al-Shukri S, Stus VP, Lipatov ON, Bair AH, et al. Axitinib versus sorafenib as first-line therapy in patients with metastatic renal-cell carcinoma: a randomised open-label phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14: 1287–1294. 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70465-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Pfizer. Axitinib (AG-013736) for the treatment of metastatic renal cell cancer. Available: http://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT00920816. Accessed 2015 March 3.

- 70. Tomita Y, Naito S, Sassa N, Takahashi A, Kondo T, Koie T, et al. Sunitinib versus sorafenib as first-line therapy for patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma with favorable or intermediate MSKCC risk factors: a multicenter randomized trial, CROSS-J-RCC. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(suppl 4): abstract 502. [Google Scholar]

- 71. Michel MS, Vervenne W, de Santis M, Fischer von Weikersthal L, Goebell PJ, Lerchenmueller J, et al. SWITCH: A randomized sequential open-label study to evaluate efficacy and safety of sorafenib (SO)/sunitinib (SU) versus SU/SO in the treatment of metastatic renal cell cancer (mRCC). J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(suppl 4): abstract 393. [Google Scholar]

- 72. Motzer RJ, Escudier B, Tomczak P, Negrier S, Gore ME, Tarazi J, et al. Axitinib vs sorafenib for advanced renal cell carcinoma: phase III overall survival results and analysis of prognostic factors. Ann Oncol. 2012;23(suppl 9): 262. Poster 793PD. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Pfizer. Axitinib (AG 013736) as second line therapy for metastatic renal cell cancer. Available: http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/results/NCT00678392. Accessed 2015 March 3.

- 74. Rini BI, Escudier B, Tomczak P, Kaprin A, Szczylik C, Hutson TE, et al. Comparative effectiveness of axitinib versus sorafenib in advanced renal cell carcinoma (AXIS): a randomised phase 3 trial. (Erratum in Lancet 2011;378:1931–1939.). Lancet. 2011;378: 1931–1939. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61613-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Motzer RJ, Escudier B, Tomczak P, Hutson TE, Michaelson MD, Negrier S, et al. Axitinib versus sorafenib as second-line treatment for advanced renal cell carcinoma: overall survival analysis and updated results from a randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14: 552–562. 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70093-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Hutson TE, Escudier B, Esteban E, Bjarnason GA, Lim HY, Pittman KB, et al. Randomized phase III trial of temsirolimus versus sorafenib as second-line therapy after sunitinib in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32: 760–767. 10.1200/JCO.2013.50.3961 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Motzer RJ, Porta C, Vogelzang NJ, Sternberg CN, Szczylik C, Zolnierek J, et al. Dovitinib versus sorafenib for third-line targeted treatment of patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma: an open-label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15: 286–296. 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70030-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Eisen T, Sternberg CN, Tomczak P, Harza M, Jinga V, Esteves B, et al. Detailed comparison of the safety of tivozanib versus sorafenib in patients with advanced/metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC) from a Phase III trial. BJU Int. 2012;110(suppl 2): 16. Abstract 35.22233268 [Google Scholar]

- 79. Eisen TQG, Sternberg CN, Tomczak P, Harza M, Jinga V, Esteves B, et al. Detailed comparison of the safety of tivozanib versus sorafenib in patients with advanced/metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC) from a phase 3 trial. Ann Oncol. 2012;23(suppl 9): 262–263. Abstract 795PD. [Google Scholar]

- 80. Motzer R, Nosov D, Eisen T, Bondarenko I, Lesovoy V, Lipatov O, et al. Tivozanib versus sorafenib as initial targeted therapy for patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma: results from a Phase III randomized, open-label, multicenter trial. BJU Int. 2012;110(suppl 2): 13. Abstract 30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Motzer RJ, Bhargava P, Esteves B, Al-Adhami M, Slichenmyer W, Nosov D, et al. A phase III, randomized, controlled study to compare tivozanib with sorafenib in patients (pts) with advanced renal cell carcinoma (RCC). J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(7 suppl 1): abstract 310. [Google Scholar]

- 82. Sternberg CN, Eisen T, Tomczak P, Strahs AL, Esteves B, Berkenblit A, et al. Tivozanib in patients treatment-naive for metastatic renal cell carcinoma: a subset analysis of the phase III TIVO-1 study. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(suppl): abstract 4513. [Google Scholar]

- 83. Motzer RJ, Nosov D, Eisen T, Bondarenko I, Lesovoy V, Lipatov O, et al. Tivozanib versus sorafenib as initial targeted therapy for patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma: results from a phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31: 3791–3799. 10.1200/JCO.2012.47.4940 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Hutson TE, Gallardo J, Lesovoy V, Al-Shukri S, Stus V, Bair AH, et al. Axitinib versus sorafenib as first-line therapy in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC). J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(suppl 6): abstract LBA348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Michel MS, Vervenne W, Goebell PJ, Fischer Von Weikersthal L, Freier W, De Santis M, et al. Phase III randomized sequential open-label study to evaluate efficacy and safety of sorafenib (SO) followed by sunitinib (SU) versus sunitinib followed by sorafenib in patients with advanced/metastatic renal cell carcinoma without prior systemic therapy (SWITCH Study): safety interim analysis results. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(suppl): abstract 4539. [Google Scholar]

- 86. von Weikersthal FL, Vervenne WL, Goebell PJ, Eichelberg C, Freier W, De Santis M, et al. Phase III randomized sequential open-label study to evaluate efficacy and safety of sorafenib (SO) followed by sunitinib (SU) versus sunitinib followed by sorafenib in patients with advanced/metastatic renal cell carcinoma without prior systemic therapy (SWITCH Study)—Safety interim analysis results. Onkologie. 2012;35(suppl 6): 237. Abstract P778.22868501 [Google Scholar]

- 87. Cella D, Escudier B, Rini B, Chen C, Bhattacharyya H, Tarazi J, et al. Time to deterioration (TTD) in patient-reported outcomes in phase 3 AXis trial of axitinib vs sorafenib as second-line therapy for metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC). Eur J Cancer. 2011;47(suppl): S224. Abstract 3006. [Google Scholar]

- 88. Cella D, Escudier B, Rini B, Chen C, Bhattacharyya H, Tarazi J, et al. Patient-reported outcomes for axitinib vs sorafenib in metastatic renal cell carcinoma: phase III (AXIS) trial. Br J Cancer. 2013;108: 1571–1578. 10.1038/bjc.2013.145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Cella D, Escudier B, Rini BI, Chen C, Bhattacharyya H, Tarazi JC, et al. Patient-reported outcomes (PROs) in a phase III AXIS trial of axitinib versus sorafenib as second-line therapy for metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC). J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(suppl): abstract 4504. [Google Scholar]

- 90. Escudier B, Loomis AK, Kaprin A, Motzer R, Tomczak P, Tarazi J, et al. Association of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in VEGF pathway genes with progression-free survival (PFS) and blood pressure (BP) in metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC) in the phase 3 trial of axitinib versus sorafenib (AXIS trial). Eur J Cancer. 2011;47(suppl): S505. Abstract 7103. [Google Scholar]

- 91. Escudier B, Motzer RJ, Lim HY, Porfiri E, Zalewski P, Kannourakis G, et al. Safety and efficacy of second-line axitinib versus sorafenib in metastatic renal cell carcinoma by duration of prior therapy: subanalyses from a phase III trial. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49(suppl 2): S673–S674. Abstract 2795. [Google Scholar]

- 92. Rini BI, Escudier B, Tomczak P, Kaprin A, Hutson TE, Szczylik C, et al. Axitinib versus sorafenib as second-line therapy for metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC): results of phase III AXIS trial. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(suppl): abstract 4503. [Google Scholar]

- 93. Rini BI, Escudier B, Tomczak P, Kaprin A, Szczylik C, Hutson TE, et al. Erratum: Rini et al (Lancet. 2011;378:1931–1939). Lancet. 2012;380: 1818 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62028-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Rini BI, Escudier BJ, Michaelson MD, Negrier S, Gore ME, Oudard S, et al. Phase III AXIS trial for second-line metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC): Effect of prior first-line treatment duration and axitinib dose titration on axitinib efficacy. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(suppl 5): abstract 354. [Google Scholar]

- 95. Ueda T, Uemura H, Tomita Y, Tsukamoto T, Kanayama H, Shinohara N, et al. Efficacy and safety of axitinib versus sorafenib in metastatic renal cell carcinoma: subgroup analysis of Japanese patients from the global randomized Phase 3 AXIS trial. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2013;43: 616–628. 10.1093/jjco/hyt054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Uemura H, Ou Y-C, Lim HY, et al. Phase III AXIS trial of axitinib versus sorafenib in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma: Asian subgroup analysis. Ann Oncol. 2012;23(suppl 11): 6.22100695 [Google Scholar]

- 97.Hutson T, Escudier B, Esteban E, Bjarnason GA, Lim HY, Pittman K, et al. Temsirolimus vs sorafenib as second line therapy in metastatic renal cell carcinoma: results from the INTORSECT trial. Presented at ESMO Congress; September 28—October 2, 2012; Vienna, Austria.

- 98.Pfizer. Temsirolimus versus sorafenib as second-line therapy in patients with advanced RCC who have failed first-line sunitinib (INTORSECT). Available: http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/results/NCT00474786. Accessed 2015 March 3.

- 99. Escudier BJ, Porta C, Squires M, Szczylik C, Kollmannsberger CK, Melichar B, et al. Biomarker analysis from a phase III trial (GOLD) of dovitinib (Dov) versus sorafenib (Sor) in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma after one prior VEGF pathway–targeted therapy and one prior mTOR inhibitor therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(suppl 4): abstract 473. [Google Scholar]

- 100. Motzer R, Sternberg CN, Vogelzang N, Urbanowitz G, Cai C, Kay A, et al. A multicenter, open-label, randomized phase 3 trial comparing the safety and efficacy of dovitinib (TKI258) versus sorafenib in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma after failure of anti-angiogenic (VEGF-targeted and mTOR inhibitor) therapies. BJU Int. 2012;109(suppl 5): 7–8. Abstract 16. [Google Scholar]