Summary

Bioluminescence, the creation and emission of light by organisms, affords insight into the lives of organisms doing it. Luminous living things are widespread and access diverse mechanisms to generate and control luminescence [1-5]. Among the least studied bioluminescent organisms are phylogenetically rare fungi – only 71 species, all within the ~9000 fungi of the temperate and tropical Agaricales Order - are reported from among ~100,000 described fungal species [6,7]. All require oxygen [8] and energy (NADH or NADPH) for bioluminescence, and are reported to emit green light (λmax 530 nm) continuously, implying a metabolic function for bioluminescence, perhaps as a by-product of oxidative metabolism in lignin degradation. Here, however, we report that bioluminescence from the mycelium of Neonothopanus gardneri is controlled by a temperature compensated circadian clock, the result of cycles in content/activity of the luciferase, reductase, and the luciferin that comprise the luminescent system. Because regulation implies an adaptive function for bioluminescence, a controversial question for more than two millenia [8-15], we examined interactions between luminescent fungi and insects [16]. Prosthetic acrylic resin “mushrooms”, internally illuminated by a green LED emitting light similar to the bioluminescence, attract staphilinid rove beetles (coleopterans) as well as hemipterans (true bugs), dipterans (flies), and hymenopterans (wasps and ants) at numbers far greater than dark control traps. Thus, circadian control may optimize energy use for when bioluminescence is most visible, attracting insects that can in turn help in spore dispersal, thereby benefitting fungi growing under the forest canopy where wind flow is greatly reduced.

Results and Discussion

Circadian clocks are biological oscillators responsible for maintaining the internal rhythms of animals, plants, fungi and cyanobacteria to the alternation of external stimuli as light and temperature [17]. Interestingly, bioluminescence and circadian biology share historical antecedents. Studies of the luminescence of the dinoflagellate Lingulodinium polyedrum (formerly Gonyaulax polyedra), shown to be regulated by a circadian clock, laid the foundations for many of the precepts and paradigms of chronobiology. These include the concept of temperature compensation and the phase response curve, the protocol used to assess the response of the clock to resetting cues as a function of time of day (4). Although analysis of fungal bioluminescence appeared in the modern literature contemporaneous with that of dinoflagellates [18], the biochemical basis of this luminescence and its possible functional/ecological significance have not been elucidated until very recently [6, 19]. The possibility of circadian regulation was noted in the early 1960’s [12,13] but quickly discounted, and in the subsequent 50 years only data questioning rhythmicity has appeared [14,15].

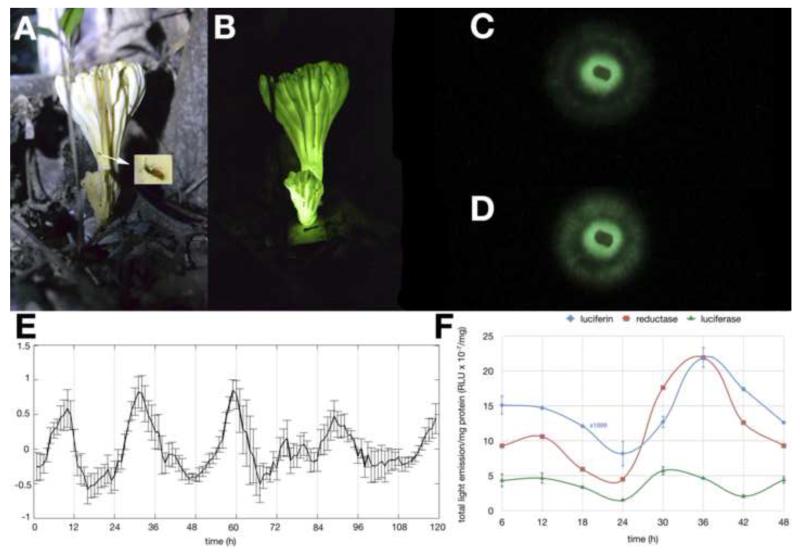

The Brazilian fungus N. gardneri belongs to the Omphalotus lineage [19] and displays exceptionally intense luminescence from either mycelium or basidiomes (Figure 1A-D). This fungus is distributed throughout of the Brazilian Coconut Forest (Mata dos Cocais) in the states of Maranhão, Tocantins, Goiás and Piauí [19], which is a transitional biome between Amazonian Forest and Caatinga. Fruiting bodies grow at the base of palm trees (Attalea humilis, A. funifera and Orbignya phalerata).

Figure 1.

Circadian control of fungal bioluminescence in Neonothopanus gardneri.

(A) Mushroom of Neonothopanus gardneri under illumination, and (B) in the dark, inset: rover beetle magnified image; (C) Minimum and (D) maximum bioluminescence from the mycelium of N. gardneri during photographical studies of light emission oscillation. (E) Bioluminescence profile from the mycelium after 48-h entrainment period at 21°C, 25°C and 29°C over a 6d experiment confirms temperature compensation of circadian period length (F) Luminescence profile from luciferin-, reductase- and luciferase-rich extracts (n = 3) obtained from mycelium after 48-h entrainment period at 25°C and over 48h (see more details on supplementary information). Luciferin light emission is multiplied by 1000. Photos obtained with a Nikon D3100, equipped with AF-S Micro Nikkor 60 mm f/2.8G ED lenses. Mushrooms: ISO 6400, f/5.6, 1/40 s (under headlamp illumination) and 15 s (in the dark) and cultures ISO 12800, f/4.5, 30 s. Mycelium of N. gardneri cultivated in 2.0% agar medium containing 1.0% sugar cane molasses and 0.10% yeast extract.

Circadian Control of Bioluminescence

Agar plates freshly inoculated with N. gardneri mycelium were maintained over 48h in a 12h-dark/light cycle at constant temperature (21°, 25° and 29°C, depending on the experiment). Following this initial entrainment period, the plates were transferred to constant darkness in a climatic chamber equipped with a CCD camera and an image was digitally recorded every hour over 6 d. Analyses of these pictures by imaging software confirmed that the light emission from the bioluminescent mycelium oscillates in a circadian rhythm of ca. 22h at 25°C (Figure 1E), with the peak phase of intensity occurring about 10 hours after the light-to-dark transfer and at circadian intervals thereafter. Circadian oscillators are temperature-compensated; i.e. they maintain a circa-24h period whenever the organisms are grown at warmer or cooler temperatures across the physiological range [17], When the experiments were repeated at 21°C and 29°C, the period was only slight changed; comparing the periods at different temperatures allowed calculation [http://www.physiologyweb.com/calculators/q10_calculator.html] of a Q10 of 1.04 for the rhythm, confirming its temperature compensation. Interestingly, these circadian period lengths of less than 24 hours are similar to those reported for Neurospora crassa, the non-luminescent ascomycete that is a prominent model system for analysis of the molecular basis of rhythms [20].

Biochemical basis of circadian bioluminescence

Luciferases (enzymes that catalyze the light emission in luminous organisms) have successfully been employed as reporters to monitor a wide array of biological processes, including rhythms. Fungal bioluminescence depends on four components, namely, a substrate (luciferin), a soluble NAD(P)H-dependent reductase, a membrane-bound oxygenase (luciferase) and oxygen [21]. Active luciferin can be extracted from cultivated mycelium using boiling citrate buffer under Argon atmosphere to prevent oxidation. The enzymes can also be partially purified from the cultivated mycelium using cold phosphate buffer, and the reductase and the luciferase subsequently separated by ultracentrifugation because the luciferase is an insoluble membrane protein. Light emission can be obtained in vitro by mixing the hot extract (luciferin source), the cold extract (reductase/luciferase source) and finally adding NADPH to trigger the reaction [21] (see more details on supplementary information). We took advantage of the natural occurrence of bioluminescence in this fungus and used its own luciferase, reductase, and luciferin to investigate the molecular basis of the oscillation in bioluminescence.

Cultures were entrained as above through 2 days of 12h-dark/light cycles prior to release into constant darkness, and the specific activity of the reductase, luciferase, and the concentration of luciferin, were measured every 6 h over 48 h (Figure 1F). The levels of all three biochemical components clearly cycle with a period of about a day, reaching maximum intensity about 6 hours after the light-to-dark transfer and at ~22h intervals thereafter; the robust 3-4 fold amplitude provides a molecular basis for the observed rhythm in luminescence.

Assessing the Adaptive Significance of Fungal Bioluminescence

Altogether, these data show that N. gardneri displays a clearly sustained rhythm in bioluminescence with a steady period of about a day whose length is temperature compensated and whose phase is set by the entraining cues of a prior light-dark cycle. While these characteristics are sufficient to define the rhythm as circadian, they do not speak to the adaptive significance of rhythmic bioluminescence to the fungus. Bioluminescence per se may fulfill a variety of bio- and ecological functions depending on the luminous organism, including prey attraction, aposematism, illumination, defense, attack, communication, sexual courtship, or as a simple metabolic by-product [1]. We considered luminescence as metabolic by-product unlikely given the existence of a specific luciferin and luciferase and instead considered possible significance in light of the biology of N. gardneri and fungi in general.

All fungi require help in getting from place to place to colonize new substrates; some achieve this through the use of winds that can carry light weight spores and others rely on animals, especially within highly stratified canopy forests where wind flow can be restricted near to the ground [22]. In the case of arthropods, spore dispersal can occur by the transportation of spores adhered to the body (ectozoochory) or inside the gut of the animal (endozoochory) [23,24]. Moreover, spore dispersal in canopy forests is greatest at night or early in the morning, when environment humidity and spore germination are highest [22]. Hence, it is reasonable to hypothesize that nocturnal transport of spores by arthropods provides an effective means of dispersal and grants some advantage to fungi, especially in dense forests.

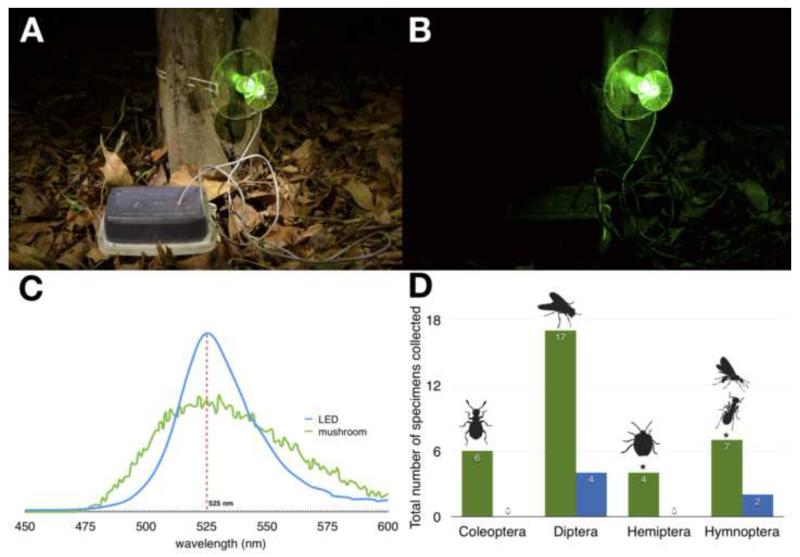

Fungal bioluminescence is too dim to be perceived by animals during the day but is readily perceived at night (even from smaller and less bright mushrooms than N. gardneri), so rhythmic control luminescence would be an attractive means to eliminate wasting energy through daytime luminescence. Work from nearly a quarter century ago suggested that insects can be attracted to bioluminescence [16] and indeed N. gardneri basidiomes are often seen infested by staphilinid rove beetles (Figure 1 inset). Given this, we tested the hypothesis that bioluminescence of N. gardneri would attract insects capable of dispersing spores. Acrylic resin “mushrooms” were fabricated and equipped with a green LED light on the base of stem such that the size, emission spectrum, and intensity of luminescence corresponded to values typical for N. gardneri basidiomes (Figure 2); nonluminescent “mushrooms” lacking the LED provided negative controls. When these were placed in the forest habitat of N. gardneri, we saw that hemipterans (true bugs), dipterans (flies), hymenopterans (wasps and ants) and other coleopterans in addition to rove beetles were captured by the light traps at greater numbers than seen with the control traps (LED light turned off). All orders of insects here reported are capable of perceiving green light [25]. Hence, our data are consistent with the hypothesis that nocturnal clock controlled bioluminescence renders N. gardneri more noticeable to insects and thus provides a selective advantage in spore dispersal not afforded to nonluminescent species.

Figure 2.

Field experiments with acrylic resin mushrooms.

(A) Acrylic resin mushroom equipped with a green LED light and covered with glue under illumination and in the dark. Traps were attached to the base of juvenile palms of Attalea speciosa in N. gardneri abundant areas at night (B); (C) Emission spectra of LED lights and N. gardneri; (D) Main specimens captured in glue from light traps or controls (LED turned off) over 5 nights (19 LED-traps and 19 controls). See Experimental Procedures for additional details. The dipteran flies (p = 0.00) and coleopteran beetles (p = 0.02) were statistically significant (binomial test, p < 0.05), while the Hemiptera (p = 0.06) and Hymenoptera (p = 0.09) were borderline when compared to the control.

Experimental Procedures

Cultures, mycelium cultivation and circadian measurements

Cultures of Neonothopanus gardneri (MycoBank MB519818) were isolated from fruiting bodies collected in the Brazilian Coconut Forest located in the municipality of Altos, Piauí [26]. The mycelium was cultivated on Petri dishes (100 mm diameter) with medium containing 1.0% (w/v) sugar cane molasses (82.2°Bx, Pol 56%) and 0.10% (w/v) yeast extract (Oxoid) in 2.0% (w/v) agar (Oxoid) [21]. The mycelium was inoculated in the center of the Petri dish on a piece of sterilized dialysis cellulose membrane (3 × 3 cm, Sigma-Aldrich) overlying the agar medium. The dialysis membrane permits prompt harvesting of the entire sample without contamination of the culture medium [27]. After inoculation, the cultures were maintained routinely in a climatic chamber (Percival) for 4 days. Different temperatures were used depending on the set of experiments. Circadian rhythms experiments in which bioluminescence from the mycelium was tracked using a CCD camera were performed at 21, 25 and 29°C as described below, whereas experiments with time-dependent extraction of luciferin, luciferase and reductase were carried out at 25°C. The Q10 of the rhythm was calculated from the formula below, where T1 and T2 are the temperatures at which the rhythm was measured and R1 and R2 are the corresponding rates. It should be noted that these are rates, not periods, rate (or frequency) being the inverse of period; periods at 21°C and 29°C were used for the calculation.

Partial purification of luciferin, luciferase and reductase

In order to obtain partially purified luciferin, three dialysis membranes containing the mycelium were removed from the medium and cut in small pieces using a scalpel. Luciferin was extracted from this material using a Potter-Elvehjem homogenizer in 1.5 mL of hot (80°C) extraction buffer A [100 mM citrate (Merck), pH 4.0, 1 mM 2-mercaptoethanol (Sigma) and 5 mM EDTA (Sigma)]. Afterwards, the homogenate was centrifuged at 5,000 × g, 5 min, 4°C and the pellet was discarded whereas the supernatant, source of luciferin, was kept in ice. All the process was carried out under ice and Argon atmosphere whenever possible.

Partial purification of the enzymes was conducted by similar extraction of mushrooms, but using cold buffer B (100 mM phosphate pH 7.6, 1 mM 2-mercaptoethanol and 5 mM EDTA). After the centrifugation, the supernatant containing both the luciferase and the reductase was ultracentrifuged (Hitachi RP50T-2, rotor P50AT2-716) at 198,000 × g, 60 min, 4°C. The supernatant contains the reductase and the pellet, the luciferase. The pellet was re-dissolved in 1.5 mL of extraction buffer B. Partially purified luciferin, luciferase (1.0-1.5 mg/mL), and reductase (1.0-1.5 mg/mL) were kept on ice for immediate use or stored on liquid nitrogen. Proteins concentrations were determined using Bradford assay [28].

Light emission assays

The luminescent reactions were carried out following the procedure described in literature [27]. In summary, each assay was composed by 100 μL of luciferase, 100 μL of reductase and 50 μL of luciferin (all components partially purified as described in the reference), 50 μL of 1 mg/mL solution of BSA (bovine serum albumin, Sigma Aldrich) and 50 μL of 70 mM NADPH (nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate sodium, Sigma Aldrich) to trigger the reaction. The light emission was recorded during 1 min using a tube luminometer (Berthold, Sirius FB15) at 25°C. All the measurements were performed in triplicate.

Circadian bioluminescence rhythm of the fungus N. gardneri – photographical studies

The cultures were grown under the conditions described above in a 12h/12h dark/light cycle over 48h in an incubator equipped with a VersArray 1300B liquid nitrogen cooled CCD camera system from Princeton Instruments. The camera was housed within a Percival incubator under conditions of constant darkness and temperature (21, 25 or 29°C) and was controlled with the WinView software (Princeton Instruments). Beginning on the third day, the light/dark cycle was terminated and the cultures were maintained at total darkness for 6 more days during which time bioluminescence was monitored. Acquisition times were set to 10 minutes with a 50 min delay between images (1 frame per hour). Data from the image series was extracted with a customized macro ([29], LF Larrondo, A Stevens-Lagos, VD Gooch, JJL, JCD in preparation) developed for ImageJ (http://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij/), and customized with an Excel interface. Although bioluminescence data can be collected from an entire culture (e.g. [29]), differences in periodicity between older and newer regions of a colony [e.g. 30] can lead to desynchronization and the appearance of rhythm dampening within a colony. To avoid this the customized Excel macro allowed collection of luminescence from regions of interest, in this case comprising concentric rings surrounding the point of inoculation, analogous to the regions of interest within growth tubes described in [29]. Data were analyzed using a suite of analysis programs designed for analysis of behavioral and molecular cycles including bioluminescence [31]: As recommended [31] chronic trends were first removed to yield a stable baseline; statistically valid rhythmicity was then confirmed by periodogram analysis, and period estimates were derived using Maximum Entropy Spectral Analysis (MESA) [31] as reported in Figure 1E.

Circadian rhythm effects on luciferin, luciferase and reductase luminescent specific activity

The cultures were cultivated (same conditions described above) in a 12h/12h light/dark cycle during 4 days in an incubator at 25°C. On the fifth day, the light/dark cycle was interrupted and the rhythm experiments were initiated. During the 48-h-experiment, the cultures were kept in total darkness. Circadian control of luciferin, luciferase and reductase was determined by assaying each one of the components separately from extracts every 6h, using stock solutions of the other two components. For example, analysis of circadian control of luciferase variation was accomplished by using 24 Petri dishes of mycelium: 3 dishes for every 6h over 48h. The luciferin concentration and the reductase activity were maintained constant during the luciferase experiment by using the same batch of frozen pre-purified luciferin (50 μL), and reductase (100 μL) samples in 350 μL total volume assay. Analogous methodology was used for monitoring the luciferin concentration and the reductase activity.

Ecological studies with acrylic resin mushrooms

Nocturnal collection of insects directly from N. gardneri mushrooms and LED light trap experiments were performed in the Brazilian Coconut Forest (Mata dos Cocais) biome in Fazenda Cana Brava, municipality of Altos, PI, Brazil (5°5′39.5″S, 42°23′12.82″W) during the rainy season of March 2013. Acrylic models of N. gardneri were equipped with one 530 nm LED and covered with scentless glue (Tangle-Trap® Stick Coating, Tanglefoot®). Experiments in the field were conducted by setting the voltage knob of the LED to the minimum value so that the light emitted by the acrylic mushrooms approximated that emitted by real mushrooms (see below). Approximately four lighted traps and four control traps (with the LED light turned off) were placed at sundown and collected before the sunrise over 5 nights in forest areas where N. gardneri is abundant. The insects captured by the glue were removed from the traps and stored in 70% ethanol after each night. Traps were then cleaned and prepared for reuse. Over 5 nights of experiments, 19 light traps and 19 control traps (n = 19) were used and a total of 42 insects from light traps and 12 from controls were captured. Sorting and identification of insects was performed with the help of the entomologists Profs. Silvio S. Nihei and Sergio Vanin from Instituto de Biologia – Universidade de São Paulo. Total arthropod counts were compared between lighted and control traps with the binomial test for significance, difference was considered significant if p < 0.05.

Efforts were made to keep the LED light at levels comparable to that emitted by mushrooms, and both would easily be perceived as bright by nocturnal insects. Because the insects are night-active it follows that they must have accommodations to allow them to see at night. In fact, night active insects including beetles and ants undergo dark adaptations that increase the sensitivity of the rhabdom and change the structure of the ommatidia, allowing even diurnal insects to visually navigate at night under extremely low light levels [32, 33], conditions under which bioluminescence by comparison may appear quite bright. However, the absolute amount of “average” bioluminescence in a mushroom in the field has been hard to estimate. Anecdotally it is well known by the local inhabitants, and has been observed by authors of this manuscript (CVS, HEW and AGO), that the amount of bioluminescence emitted by N. gardneri varies greatly depending, of course, on the size and age of the fruiting body but also greatly on the ambient humidity, optimal conditions being night time following a hot day with an afternoon rain storm and a light evening/night breeze. These were the conditions in the forest during the rainy season in March 2013 when the experiments described in the article were performed.

Bioluminescence and LED light emission spectra

Bioluminescence of N. gardneri mushroom and LED light emission spectra were recorded using a Hitachi F-4500 spectrofluorometer set at 400 V PMT voltage and emission slit 1.0 nm (LED) 700 V PMT voltage and emission slit 20 nm (mushroom).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We dedicate this contribution to commemorate late J. Woodland Hastings whose 65 years of pioneering research on bioluminescence and circadian biology continue to illuminate all subsequent work. We are indebted to Dr. Ismael Dantas, owner of Cana Brava Farm in Altos, PI, Brazil, for the collection of N. gardneri. We also thank Profs. Silvio S. Nihei and Sérgio Vanin from Instituto de Biologia, Universidade de São Paulo for help with the identification of insects. Supported by grants GM34985 to JCD, GM083336 to JJL and JCD, 2010/11578-5 to AGO, FAPESP 13/16885-1 and NAP-PhotoTech (the USP Research Consortium for Photochemical Technology) to CVS.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Hastings JW, Wilson T. Bioluminescence Living Lights, Lights for Living. Harvard University Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haddock SHD, Moline MA, Case JF. Bioluminescence in the sea. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci. 2010;2:443–493. doi: 10.1146/annurev-marine-120308-081028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Widder EA. Bioluminescence in the ocean: Origins of biological, chemical and ecological diversity. Science. 2010;328:704–708. doi: 10.1126/science.1174269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hastings JW. The Gonyaulax clock at 50: translational control of circadian expression. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 2007;72:141–144. doi: 10.1101/sqb.2007.72.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Visick KL, Ruby EG. Vibrio fischeri and its host: it takes two to tango. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2006;9:632–638. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2006.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stevani CV, Oliveira AG, Mendes LF, Ventura FF, Waldenmaier HE, Carvalho RP, Pereira TA. Current status of research on fungal bioluminescence: biochemistry and prospects for ecotoxicological application. Photochem. Photobiol. 2013;89:1318–1326. doi: 10.1111/php.12135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stajich JE, Berbee ML, Blackwell M, Hibbett DS, James TY, Spatafora JW, Taylor JW. The fungi. Curr. Biol. 2009;19:R840–845. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boyle R. Observations and tryals about the resemblances and differences between a burning coal and shining wood. Phil. Trans. 1666;2:605–612. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harvey EN. A History of Luminescence from the Earliest Times until 1900. The American Philosophical Society; Philadelphia: 1957. Aristotle, De Anima (Book II, Chap. 7, Sec. 4), cited in. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Desjardin DE, Oliveira AG, Stevani CV. Fungi bioluminescence revisited. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2008;7:170–182. doi: 10.1039/b713328f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mendes LF, Bastos EL, Desjardin DE, Stevani CV. Influence of culture conditions on mycelial growth and bioluminescence of Gerronema viridilucens. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2008;282:132–139. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2008.01118.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Berliner MD. Diurnal periodicity of luminescence in three basidiomycetes. Science. 1961;134:740. doi: 10.1126/science.134.3481.740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Calleja GB, Reynolds GT. The oscillatory nature of fungal luminescence. Trans. Br. Mycol. Soc. 1970;55:149–154. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mihail JD, Bruhn JN. Dynamics of bioluminescence by Armillaria gallica, A. mellea and A. Mycologia. 2007;99:341–350. doi: 10.3852/mycologia.99.3.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mihail JD. Comparative bioluminescence dynamics among multiple Armillaria gallica, A. mellea, and A. tabescens genets. Fungal Biol. 2013;117:202–210. doi: 10.1016/j.funbio.2013.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sivinski J. Arthropods attracted to luminous fungi. Psyche. 1981;88:383–390. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dunlap JC, Loros JJ, DeCoursey PJ. Chronobiology: Biological timekeeping. Sinauer Associates; Sunderland, Massachusetts: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hastings JW, Sweeney BM. The luminescent reaction in extracts of the marine dinoflagellate, Gonyaulax polyedra. J Cell Physiol. 1957;49:209–25. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1030490205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oliveira AG, Stevani CV. The enzymatic nature of fungal bioluminescence. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2009;8:1416–1421. doi: 10.1039/b908982a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Capelari M, Desjardin DE, Perry BA, Asai T, Stevani CV. Neonothopanus gardneri: a new combination for a bioluminescent agaric from Brazil. Mycologia. 2011;106:1433–1440. doi: 10.3852/11-097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baker CL, Loros JJ, Dunlap JC. The circadian clock of Neurospora crassa. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2012;36:95–110. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2011.00288.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shaw DC. In: Vertical organization of canopy biota. In Forest Canopies. 2nd ed. Lowman MD, Rinker HB, editors. Elsevier Academic Press; 2004. pp. 73–101. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lilleskov EA, Bruns TD. Spore dispersal of a resupinate ectomycorrhizal fungus, Tomentella sublilacina, via soil food webs. Mycologia. 2005;97:762–769. doi: 10.3852/mycologia.97.4.762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Malloch D, Blackwell M. In: Dispersal of fungal diaspores. In The Fungal Community: Its Organization and Role in the Ecosystem. 2nd ed. Carroll GC, Wicklow DT, editors. CRC Press; 1992. pp. 147–171. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Briscoe AD, Chittka L. The evolution of color vision in insects. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2001;46:471–510. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ento.46.1.471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Capelari M, Desjardin DE, Perry BA, Asai T, Stevani CV. Neonothopanus gardneri: a new combination for a bioluminescent agaric from Brazil. Mycologia. 2011;6:1433–1440. doi: 10.3852/11-097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oliveira AG, Desjardin DE, Perry BA, Stevani CV. Evidence that a single bioluminescent system is shared by all known bioluminescent fungal lineages. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2012;11:848–852. doi: 10.1039/c2pp25032b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bradford MM. Rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Larrondo LF, Loros JJ, Dunlap JC. High-resolution spatiotemporal analysis of gene expression in real time: in vivo analysis of circadian rhythms in Neurospora crassa using a FREQUENCY-luciferase translational reporter. Fungal Genet Biol. 2012;49:681–3. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2012.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dharmananda S, Feldman JF. Spatial distribution of circadian clock phase in aging cultures of Neurospora crassa. Plant Physiol. 1979;63:1049–54. doi: 10.1104/pp.63.6.1049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Levine JD, Funes P, Dowse HB, Hall JC. Signal analysis of behavioral and molecular cycles. BMC Neurosci. 2002;3:1. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-3-1. Epub. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Meyer-Rochow VB. The eyes of Creophilus erythrocephalus F. and Sartallus signatus Sharp (Staphylinidae: Coleoptera). Light-, interference-, scanning electron- and transmission electron microscope examinations. Z Zellforsch Mikrosk Anat. 1972;133:59–86. doi: 10.1007/BF00307068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Warrant E, Dacke M. Vision and visual navigation in nocturnal insects. Annu Rev Entomol. 2011;56:239–54. doi: 10.1146/annurev-ento-120709-144852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.