Abstract

Previous studies indicate that conditional genetic deletion of phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) in neonatal mice enhances the ability of axons to regenerate following spinal cord injury (SCI) in adults. Here, we assessed whether deleting PTEN in adult neurons post-SCI is also effective, and whether enhanced regenerative growth is accompanied by enhanced recovery of voluntary motor function. PTENloxP/loxP mice received moderate contusion injuries at cervical level 5 (C5). One group received unilateral injections of adeno-associated virus expressing CRE (AAV-CRE) into the sensorimotor cortex; controls received a vector expressing green fluorescent protein (AAV-GFP) or injuries only (no vector injections). Forelimb function was tested for 14 weeks post-SCI using a grip strength meter (GSM) and a hanging task. The corticospinal tract (CST) was traced by injecting mini-ruby BDA into the sensorimotor cortex. Forelimb gripping ability was severely impaired immediately post-SCI but recovered slowly over time. The extent of recovery was significantly greater in PTEN-deleted mice in comparison to either the AAV-GFP group or the injury only group. BDA tract tracing revealed significantly higher numbers of BDA-labeled axons in caudal segments in the PTEN-deleted group compared to control groups. In addition, in the PTEN-deleted group, there were exuberant collaterals extending from the main tract rostral to the lesion, into and around the scar tissue at the injury site. These results indicate that PTEN deletion in adult mice shortly post-SCI can enhance regenerative growth of CST axons and forelimb motor function recovery.

Keywords: spinal cord injury, mouse, axonal growth, axon regeneration, corticospinal tract, CST, sprouting, motor system, recovery of function, Cremediated recombination

INTRODUCTION

Axon regeneration in the mature mammalian brain and spinal cord is extremely limited after injury. Consequently, spinal cord injury causes persistent paralysis due to disconnection of descending axons from their normal targets. Presumably, recovery would be improved if axon regeneration could be achieved and if regenerating axons re-established functional synapses below the injury level.

The extent of axon regeneration depends on the intrinsic capacity of mature neurons to re-grow axons (Goldberg 2004, Sun et al 2010) and extrinsic inhibitors in myelin and the glial scar (Tang et al 2003; Selzer 2003, Wanner et al 2008, Cafferty et al 2010). Intrinsic growth capabilities of neurons are regulated by gene transcription, which in turn controls the neuron’s protein synthesis critical for axon regeneration. Intrinsic factors that have been shown to affect axon growth are components of signaling pathways and include axon growth enhancers such as cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) (Cai et al 2001, Rodger et al 2005), mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR)(Verma et al 2005) and repressors such as Phosphatase and Tensin homolog (PTEN), Kruppel-like transcription factors (KLFs) (Dang et al 2000, Moore et al 2011) and suppressor of cytokine signaling 3 (SOCS3) (Smith et al 2009, Hellstrom et al 2011).

Of the intrinsic repressors, PTEN has emerged as a promising target for manipulations to enable axon regeneration after injury. PTEN is a negative regulator of the PI3K/AKT-mTOR pathway, which plays an important role in controlling cell growth (Sabatini 2006; Ma and Blenis 2009). PTEN converts PtIns(3)P to PtIns(2)P reversing the reaction catalyzed by phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K). Inactivation of PTEN results in the accumulation of PtIns (3)P, activating AKT and mTOR, which is a central regulator of cap-dependent protein synthesis and cell growth.

Using an optic nerve crush model, Park et al (2008) demonstrated that conditional genetic deletion of PTEN in the retina promoted both survival of axotomized retinal ganglion cells and enabled robust regeneration of injured optic nerve axons. Subsequent studies revealed that conditional deletion of PTEN in the sensorimotor cortex of developing mice (at day 1 postnatal) enabled adult corticospinal tract (CST) axons to regenerate following spinal cord injuries at the thoracic level (Liu et al 2010). An unresolved question, however, was whether this regeneration was sufficient to support recovery of motor function and whether regeneration could be achieved by deleting PTEN in mature neurons after an injury.

Accordingly, here we assess whether deletion of PTEN after a spinal cord injury in adult mice enables CST regeneration and enhances recovery of motor function. We use an injury model and functional assessments that are thought to measure functions related to the CST, specifically a moderate contusion injury at C5 and assessments of voluntary forelimb motor function (Aguilar et al., 2010). The C5 contusion model is of high relevance for human SCI, because about half of the spinal cord injuries in people are at the cervical level, and recovery of upper extremity function is a high priority for individuals with such injuries (Anderson et al., 2009).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Experimental animals

Experimental animals were adult female mice (PTENloxP/loxP strain C;129S4-Ptentm1Hwu/J) (http://jaxmice.jax.org/strain/004597.html) that were between 5 and 7 weeks of age (20–25g) at the beginning of the experiment. Females mice were used because it is easier to manually express bladders of female mice following SCI, leading to fewer complications due to urinary tract infections. All procedures involving animals were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of the University of California Irvine.

Thirty eight mice received spinal cord injuries on two consecutive days (13 mice on the first day and 25 mice on the second day). Mice from each cage were assigned to 3 groups by a technician who was not involved in either surgeries or AAV-CRE/GFP injections. Groups were: 1) injury only, 2) vector control (AAV-GFP) and 3) PTEN-deleted group (AAV-CRE). Assignment to groups was not explicitly random; assignment to groups was made at the time the mice were removed from the cage maintaining approximately equal numbers between groups. The individuals performing the spinal cord injury surgery were blind as to group assignment. At the end of the surgery, mice were assigned a code by the technician so that testing could be done blind.

A total of 3 out of 13 mice operated on the first day of surgery died or were euthanized. Two of those were a result of anesthesia complications during SCI surgery and one was euthanized due to excessive weight loss. A total of 4 out of 25 mice operated on the second day of surgery died or were euthanized, 3 of which were a result of anesthesia complications during SCI surgery and one was euthanized due to excessive weight loss. Behavior data were included in the analyses for mice that survived until the tracer injection surgeries (see below). Thus, after attrition due to all causes, total animal numbers at the end of all experiments were: injury only group n=10, vector control n=10 and PTEN-deleted group n=11 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Final number of mice per group in each experiment

| Group | Injury only | AAV-GFP | AAV-CRE | TOTAL |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exp #1 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 10 |

| Exp #2 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 21 |

| TOTAL | 10 | 10 | 11 | 31 |

Spinal cord surgical procedures

The spinal cord injury model was previously described by Aguilar et al 2010. Mice were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of ketamine and xylazine (100mg/kg and 10mg/kg, respectively). When supplemental anesthesia was required, one-fourth of the original dose was given. Hair overlying the cervical vertebrae was removed by shaving, the skin was incised and the connective and muscle tissue was dissected to expose the vertebral column from C4–C6. A dorsal laminectomy was performed on C5. The spinal column was clamped at C4 and C6 using forceps attached to the Infinite Horizon (IH) device platform. The impacting tip (1 mm diameter) was positioned at the middle of the dorsal spinal cord at C5 to generate the bilateral contusion. Impact force was 80 kilodynes (kdyn) to produce a moderate contusion. After creating the lesion, the muscle was sutured with 5–0 chromic gut and the skin was closed with 7-mm wound clips.

AAV-CRE Injections

About 20 min following the contusion injury, mice were transferred to a stereotaxic device, the scalp was shaved and drill holes were placed over the sensorimotor cortex. Mice received unilateral intra-cortical injections of either AAV-Cre to delete PTEN or the control vector AAV-GFP 6.8 × 1010 genome copies. Injections were made at 4 sites (0.4 μl/site) in the right sensorimotor cortex at 1.0mm lateral, 0.5 mm deep to the cortical surface and + 0.5, −0.2, −0.5, −1 mm with respect to bregma. The total time required to complete the intra-cortical injections was approximately 20 minutes. Following completion of the injections, the scalp was closed with 4-0 silk suture.

Post-operative care

Following the surgeries, the mice were immediately placed on water–circulating jacketed heating pad at 37°C. After recovering from the anesthetic, mice were housed 4–5 per cage on Alpha-Dri bedding. For 5–7 days post-injury, mice received lactate Ringer solution (1ml/20g, sub-cutaneously) for hydration, Buprenorphine (0.01mg/kg) for analgesia, and Baytril (2.5mg/kg, subcutaneously) for prophylactic treatment against urinary tract infections. Animals were monitored twice daily for general health, coat quality (indicative of normal grooming activity) and mobility within the cage. Injured mice typically resume these activities within a few days following injury. Bladders were manually expressed twice/day for the first week and body weight was measured once per week for the remainder of the experiment. Diet supplements (fruit loop cereal) and regular food pellets were placed on the floor of the cage to provide easy access. Nutri-cal (1ml, Henry Schein, Melville, NY) was administered orally for the first week post-injury.

Behavioral testing

A 3 week handling and pre-training procedure was used prior to SCI, in order to calm the mice and enhance reliability when testing, during which the animals were trained and baselines were collected for all tasks. Behavioral testing was conducted for 14 weeks post-injury as described below for the individual tasks. Testing was done blind with respect to treatment groups except that scalp scarring made it possible to identify mice that received intra-cortical injections but not which vector was injected.

Grip strength meter (GSM) task

Reliable assessment of gripping ability requires that animals are accustomed to being held. Therefore, the first week was limited to handling each animal for 5 min each day. In week 2, mice were trained on the Grip Strength Meter (GSM) task using a device designed by TSE-Systems and distributed by SciPro, Inc. For testing, mice are held by the tail next to the bar so that they reach out to grip the bar. To test grip strength of one paw, the opposite forepaw was gently taped with non-stick surgery tape (Micropore™ surgical tape from 3M, catalog nr.1530-0) so that it could not be used for gripping. The dimension of the working piece of tape was approximately 0.5 × 0.75 inches to prevent the tape from hindering the pull by the opposite forepaw. In the two-paw version, mice are allowed to grip with both paws simultaneously. Once grip was established, mice are gently pulled away until they released their grip.

Grip strength of each paw was tested three times per week (10 trials/session). The mice were held facing the bar so that they did not reach at an angle during the trials. Bar height was set as 3.5mm so that as mice were gently pulled away, they remain suspended just above the surface, but did not drop extensively when they released the bar.

Each testing session assessed each forepaw separately or both paws together until 4 successful grips were recorded for a maximum of 15 trials per session. A positive grip was scored when the digits extended and then flexed upon contacting the bar followed by the digits being extended as the mouse released the bar and landed on the platform. A score of zero was given when a clenched/closed forepaw engaged the bar or if the forepaw landed on the platform in a clenched/closed position. When gripping by both forepaws was assessed, a score of zero was given if grip was only established by only one forepaw.

In each session, if the mouse did not grip within the first 10 trials then the mouse was given 0 for the four data points/session/forepaw(s). If the mouse gripped successfully during the first 10 trials, then the testing continued until 4 successful trials were executed or the 15 trials maximum was reached. Mice were tested 3 times prior to injury and 2 times/week for 14 weeks post-injury.

Hanging task

To assess the ability of the forepaws to grasp and maintain grip, we assessed the ability of mice to hang from a suspended metal rod as previously described (Diener et al 1998) with few modifications. Following handling as described above mice were trained for 2 days before collecting the baselines. For testing, the GSM base was placed vertically against a wall. The grip strength bar was raised to its maximal height so the mice could not lean against the base. For testing, hindpaws were taped to prevent their being used for climbing atop of the metal bar. We recorded how long the mice were able to hang before falling onto a pad about 10 ins below. Three trials were collected per session per mouse. If the mouse tried to use any parts of the body to hold onto the bar, the mouse’s tail was gently pulled so that the mouse only used its forepaws to grasp the bar. Testing was performed two times prior to injury and every two weeks for 14 weeks post-injury.

Mini-ruby BDA tracing of CST projections

In order to trace the corticospinal tract, tracer injections were made into the right sensorimotor cortex at 15 weeks post-injury using the same coordinates as for AAV-CRE and AAV-GFP injections. For this purpose, mice were anesthetized using 2.5% isofluorane and positioned in a stereotaxic device, the fur was removed by shaving, the scalp was incised and the skull overlying the sensorimotor cortex was carefully removed with a dental drill. Mini-ruby BDA (dextran, tetramethylrhodamine, and biotin: molecular weight 10,000; 10% in dH2O (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) was injected into a total of 4 sites (0.4 μl/site over a 3–5 min time period) using a 10 μl Hamilton microsyringe tipped with a pulled glass micropipette. After the injections were completed, the skin overlying the skull was sutured with 4-0 silk, and mice were placed on soft bedding on a water-jacketed warming pad at 37°C for 4h after surgery. Behavioral tests were not performed during the time between BDA injections and perfusion.

Tissue preparation

At the end of the study, mice were killed humanly with an overdose of Euthasol (0.1 ml/30g) and perfused transcardially with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in 0.1M sodium phosphate buffer (Na2HPO4), pH=7.4. Spinal cords and brains were dissected and post-fixed in 4% PFA overnight, then immersed in 27% sucrose for cryoprotection overnight, frozen in TissueTek OCT (VWR International) and stored at −80°C until they were sectioned with a cryostat.

Three tissue blocks were prepared from the spinal cords: 1) a tissue block extending from ~4mm above to 4mm below the lesion and containing the injury site; 2) the portion of the spinal cord rostral to the tissue block containing the lesion and 3) the portion of the spinal cord caudal to the tissue block containing the lesion, extending to the caudal most segment. The main block containing the lesion was sectioned at 20 μm in the horizontal plane, and the rostral end of spinal cord above the injury block and the caudal end below the injury were sectioned transversely. The brains were sectioned at 20μm in the coronal plane and sections were collected in TBS.

Immunostaining to assess PTEN deletion

To address the PTEN deletion following AAV-Cre injection, free-flating coronal sections through the brain were incubated in 1% hydrogen peroxide for 15 min. After blocking in Tyramide Signal Amplification (TSA) blocking buffer (0.5g blocking reagent/ 40ml TBS, PerkinElmer, FP1012) sections were incubated in primary antibody at RT overnight (rabbit anti-PTEN, Cell Signaling 9188S, 1:250). Sections were washed in TBS and incubated with secondary antibody (donkey anti-rabbit HRP, Jackson Immunolabs 711-065-152, 1:250) in TSA blocking buffer for 2 hours at RT. Following a wash in TBS, sections were stained with 3–3′ diaminobenzidine (DAB, Vector Labs SK-4100) for 5 min, rinsed in TBS, mounted on gelatin subbed slides in weak mounting solution (0.5% gelatin and 0.05% chromium potassium sulfate, Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), air-dried and cover-slipped with DPX mounting medium.

BDA and GFAP immunostaining

The block of the spinal cord containing the lesion was frozen in OCT and sectioned in the horizontal plane at 20 μm thickness, collecting every section, and maintaining serial order during histological processing. All the sections from the block containing the lesion site were co-stained for BDA and glial fibrilary acidic protein (GFAP). BDA staining was used to confirm interruption of CST axons due to the contusion injury and to analyze spared and regenerating axons. GFAP immunostaining was used for lesion identification.

Free-floating sections were collected in PBS. After blocking in 5% normal goat serum in PBS, sections were incubated in primary antibody at 4°C overnight (rabbit anti-GFAP Dako ZO334, 1:1000) in PBS with 5% normal goat serum. The following day, sections were washed in PBS and incubated with the fluorescent secondary antibody (goat anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 488, Molecular Probes A-11034, 1:250) in PBS with 5% normal goat serum for 2h at room temperature. Following GFAP immunohistochemistry, the sections were processed for BDA amplification signal using the TSA (PerkinElmer, NEL704A001KT) kit. After 15 min wash in PBS and 0.1% Triton X-100 (PBST), sections were incubated in horseradish peroxidase (HRP) conjugated streptavidin (PerkinElmer, NEL750001EA, 1:200) in PBST for 2h at room temperature. The sections were washed three times in PBS and incubated in Cyanine 3 Tyramide reagent (PerkinElmer, FP 1046, 1:100) in amplification diluent (PerkinElmer, FP1052) for 15 min at room temperature. After being rinsed twice in PBS, sections were mounted on gelatin-subbed slides air-dried and cover-slipped with Vectashield® mounting medium.

Cross sections from the blocks rostral and caudal to the injury were washed twice in 1X PBS and 0.1% Triton X-100, incubated overnight at 4°C with avidin and biotinylated horseradish peroxidase (Vectastain ABC Kit, Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA). The next day, sections were washed twice in PBS, and then reacted with diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride with nickel (DAB-N, Vector Labs, SK-4100) for 25 min at room temperature, rinsed in PBS and mounted onto gelatin coated slides, air-dried, dehydrated and coverslipped with DPX mounting media (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO).

Assessment of regenerative growth of corticospinal tract (CST) axons

Total BDA-labeled axon counts

Cross-sections from the rostral-most block were used to determine the extent of CST labeling above the lesion and the number of BDA-labeled axon arbors that enter the gray matter of the cervical spinal cord above the lesion. Images were captured on an Olympus AX-80 microscope (Olympus Provis) using MagnaFire SP 21B software (Optronics Software, Goleta, CA). The density of BDA labeled axons in the dorsal CST was very high, making it difficult to count all axons. Therefore, to estimate axon numbers in dCST, images were taken at 120× initial magnification (a 60× objective magnified 2× under oil immersion). The axons were counted using the cell counter analyzer in ImageJ software. For the quantitative assessments the sample group was disclosed at the end of measurements.

Quantification of regenerative growth

To determine the number of BDA-labeled axons that extended into and caudal to the lesion, 20 μm horizontal sections through the block containing the injury were examined. Images were captured at 10×, montages were created and exported to ImageJ software. Perpendicular lines to the dorsal surface were set in the middle of the lesion (0mm) and at 0.2mm intervals through the entire spinal cord caudal to the lesion (as illustrated in Fig 11A). BDA-labeled axons crossing these lines were quantified in three regions through the spinal cord: dorsal column, lateral column and gray matter caudal to the lesion. The axon counts were summed for each mouse and averaged for each group. Data are represented as an index for each category following the formula: Index dorsal column (Dc) = number of BDA labeled axons in dorsal column/total number of BDA labeled axons; Index lateral column (Lc) = number of BDA labeled axons in lateral column/total number of BDA labeled axons; Arbor index (AI) = total number of axon arbors in gray matter caudal to the lesion/total number of BDA labeled axons.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using Prism software by One-Way ANOVA or Two-Way Repeated Measures ANOVA with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. Results were plotted as means plus or minus SEM.

RESULTS

Preoperative performance in the GSM and hanging test

Prior to injury, the average force applied before the mice released the bar of the grip strength meter (GSM) was approximately 45g for both right and left paws (Table 2). Average values for the GSM remained fairly consistent over testing days once the mice became accustomed to the testing procedure. These values are lower than the average values in a previous study using similar procedures in which the force applied before the mice released the bar was approximately 60–70g (Aguilar et al., 2011). This may be due to the different genetic background of the mice because the PTENff mice are of mixed genetic background but mainly FVB whereas the mice used in Aguilar et al were C57Bl/6. To test this possibility, the same testing procedures were used to test a group of mice from our breeding colony that are of C57Bl/6 genetic background. The values obtained were about 60 g (58.6 ± 1.47 SEM left paw and 56.5 ± 1.78 SEM right paw) suggesting that variation in values between our experiment and the previous publication reflect differences between strains.

Table 2.

: Pre-injury gripping force (g) values for both left and right forepaws expressed as a mean ± SEM, n=8–9 per group

| GROUPS | Gripping Force (Left Paw) |

Gripping Force (Right Paw) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Days Pre-Injury | Days Pre-Injury | |||||

| −10 | −6 | −5 | −10 | −6 | −5 | |

| Injury ONLY | 49.06±1.8 | 47.91±2.38 | 48.22±1.4 | 44.34±2 | 47.13±2.7 | 44.6±1.9 |

| AAV-CRE | 48.4±1.86 | 40.97±1.8 | 42.78±2.8 | 39.06±2.3 | 40.44±2.8 | 42.58±2.6 |

| AAV-GFP | 43.75±2.5 | 44±3.82 | 49.06±4 | 38.38±2.8 | 38.91±3.3 | 42.22±3.6 |

| Repeated measures ANOVA |

F=1.22 P=0.3136 |

F=1.7 P=0.2057 |

||||

In the hanging task, mice retained their grip on the bar for an average of about 60sec before falling; the average hanging time was similar between the groups on the last pre-operative testing day during which baseline data were collected (Table 3). Preoperative hanging time values were recorded once following two sessions of training, so only one preoperative value is available.

Table 3.

Pre-injury hanging time values (sec) in all three groups expressed as a mean ± SEM, n=8–9 per group

| GROUPS | Hanging Time (sec) |

|---|---|

| Injury ONLY | 62.78 ± 9.48 |

| AAV-CRE | 56.58 ± 6.98 |

| AAV-GFP | 55.04 ± 7.94 |

| One Way ANOVA | P=0.787 |

Contusion Injuries

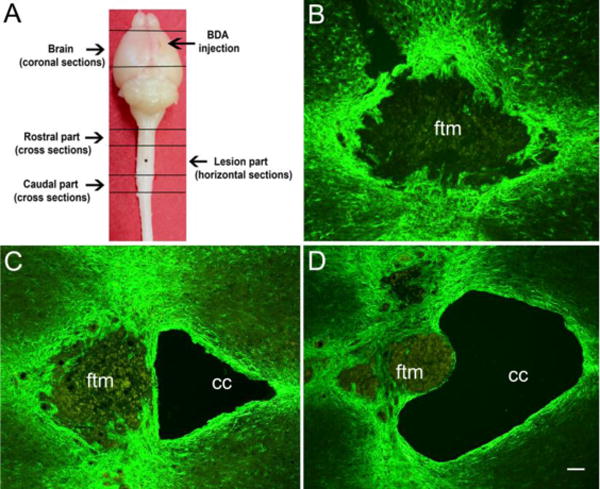

Figure 2 illustrates the method of tissue preparation and examples of lesion sites in horizontal sections of the spinal cord imaged for GFAP. Most lesions were filled in with a fibrous tissue matrix (23 out of 31) but small cystic cavities were found along with the fibrous matrix in 8 mice (Fig 2B–C). In 5 mice, the lesions were obviously asymmetric, and in one mouse, the lesion was incomplete; data from these mice were excluded from the behavioral analyses and analysis of CST axon distribution. Table 4 summarizes lesion characteristics for each mouse in this study.

Fig. 2. Representative examples of lesions at the lesion epicenter after an 80 kdyn cervical contusion.

A) Tissue block preparation for brains and spinal cords. B–D) Images of GFAP immunostained spinal cords with a fibrous filled lesion (B) and mixed fibrous/cystic cavities (C–D) ftm: fibrous tissue matrix; cc: cystic cavity; asterisk represents the lesion site; scale bar 200 μm.

Table 4.

Comprehensive description of spinal cord injuries conditions and lesion types

| Animal # | Experimental group | Force (kdyn) |

Type of lesion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exp 1 #2 | AAV-CRE | 82 | Fibrous/asymmetric |

| Exp 1 #3 | Injury ONLY | 85 | Fibrous/Cystic cavity |

| Exp 1#4 | AAV-CRE | 84 | Fibrous |

| Exp 1 #6 | Injury ONLY | 84 | Fibrous |

| Exp 1 #7 | AAV-CRE | 86 | Fibrous |

| Exp 1 #9 | AAV-GFP | 80 | Fibrous |

| Exp 1 #12 | AAV-GFP | 80 | Fibrous |

| Exp 1 #14 | AAV-CRE | 89 | Fibrous |

| Exp 1 #29 | Injury ONLY | 81 | Fibrous/Cystic cavity/incomplete |

| Exp 1 # 5 | AAV-GFP | 84 | Fibrous/asymmetric |

| Exp 2 #17 (2B33) | AAV-CRE | 80 | Fibrous |

| Exp 2 # 10 (377B) | Injury ONLY | 84 | Fibrous |

| Exp 2 # 11 (5448) | AAV-GFP | 85 | Fibrous |

| Exp 2 #22 (4909) | AAV-CRE | 82 | Fibrous |

| Exp 2# 16 (2A6E) | AAV-GFP | 80 | Fibrous |

| Exp 2 # 15 (6240) | Injury ONLY | 84 | Fibrous/Cystic cavity/asymmetric |

| Exp 2#28 (0E08) | AAV-CRE | 85 | Fibrous |

| Exp 2 #23 (613B) | AAV-GFP | 81 | Fibrous/Cystic cavity |

| Exp 2 #19(6041) | Injury ONLY | 86 | Fibrous/Cystic cavity |

| Exp 2 #32 (5750) | AAV-CRE | 81 | Fibrous/asymmetric |

| Exp 2#30 (360F) | AAV-GFP | 81 | Fibrous/asymmetric |

| Exp 2 #21(1243) | Injury ONLY | 81 | Fibrous |

| Exp 2 # 34 (734A) | AAV-CRE | 85 | Fibrous/Cystic cavity |

| Exp 2 #33 (7A2B) | AAV-GFP | 83 | Fibrous |

| Exp 2 #31 (2054) | Injury ONLY | 87 | Fibrous |

| Exp 2 # 37 (7147) | AAV-CRE | 82 | Fibrous/Cystic cavity |

| Exp 2 #35 (4509) | AAV-GFP | 83 | Fibrous |

| Exp 2 #36 (2D7F) | Injury ONLY | 80 | Fibrous |

| Exp 2 #38 (440E) | AAV-CRE | 84 | Fibrous/Cystic cavity |

| Exp 2 #24 (2A48) | Injury ONLY | 88 | Fibrous |

| Exp 2 #27 (6962) | AAV-GFP | 84 | Fibrous |

General health following moderate contusion injuries

For the first few days following the moderate bilateral cervical contusion and AAV-CRE or GFP injections, mice were significantly impaired and required attention and care. One day after the injury, mice exhibited limited spontaneous locomotion but they were able to right themselves and raised their heads to eat and drink. Within 2 days mice began moving their body with weight bearing by the hindlimbs but movement was slow and there was a minimal use of the forelimbs. Recovery progressed so that within 5 days, mice were able to move around their cage although forepaw use was limited.

To provide a quantitative measure of general health, mice were weighed just prior to injury and throughout the post-injury survival period. During the first two weeks post-injury mice lost about 2–3% of their pre-injury body weight except in two cases. Mouse #2 from the PTEN-deleted group lost 16% body weight but recovered by 3 weeks post-injury; mouse #25 from the injury only group lost 17% by the week 2 and 29% by the week 3 and was euthanized.

Assessment of forelimb motor function

Grip strength meter

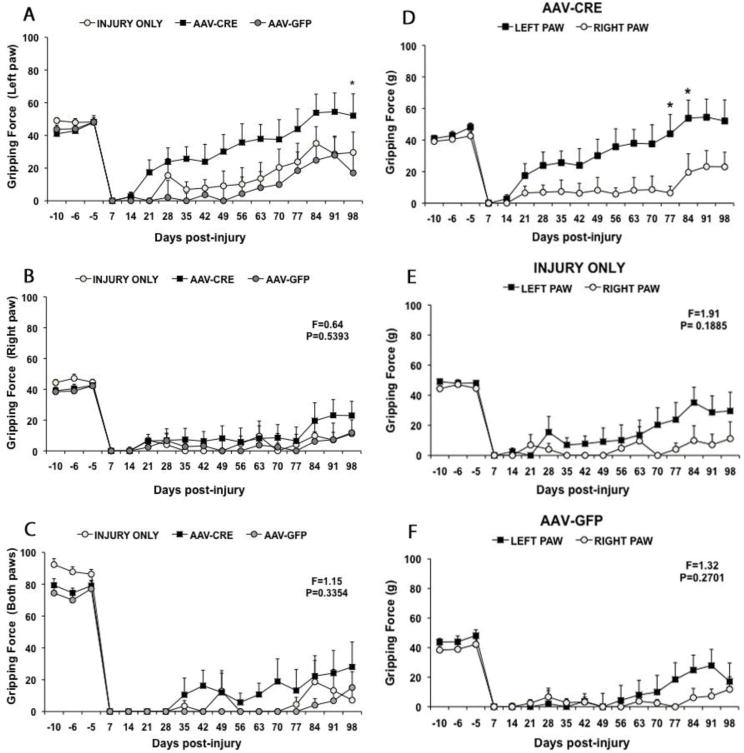

In considering the results from the mice in which PTEN was deleted, it is important to note that AAV-CRE was injected unilaterally into the right motor cortex. This was done in order to be able to compare recovery of the paw normally controlled by the PTEN-deleted cortex (the left paw) vs. the contralateral side. Accordingly, data are presented separately for each paw in Figure 3A&B.

Fig. 3. Forepaw gripping function as measured by the GSM after C5 contusion injury.

A) Comparison of average gripping force by the right forepaw in each group before injury (negative numbers) and at different times post-injury. B) Comparison of average gripping force by the right forepaw in each group. C) Comparison of average gripping force when both forepaws are tested together. Note enhanced gripping force of the right forepaw in the PTEN deleted group, and similarity of gripping force in the different groups when measuring the left forepaw. The gripping force values represent the average of 2 trials per week. Panels D, E and F illustrate a direct comparison between left and right forepaws in the different groups. D) PTEN-deleted group: grip strength of the left paw recovered earlier and to a greater extent than the grip strength of the right paw. E) Injury only group: grip strength was comparable in both paws until about 60 days post-injury. There were no statistically significant differences between the values for the two paws by repeated measures ANOVA (F and p values are shown on the graph). F) AAV-GFP group: grip strength was comparable in both paws until about 70 days post-injury. There were no statistically significant differences between the values for the two paws by repeated measures ANOVA (F and p values are shown on the graph). Results are presented as a mean ± SEM, n=8–9 per group. Data were analyzed using Repeated Measures ANOVA followed by Bonferroni posttests: *P<0.05 statistical significantly different from AAV-GFP group (A) and when compared with right paw (D).

Griping ability in left and right paws as measured by the GSM was severely impaired at 7 and 14 days post-injury in all 3 groups (Figure 3A&B). In both control groups, grip strength remained low in both paws until about 56 days, when the left paw began to show some recovery of strength (Figure 3A). At 35 days post-injury average grip strength of the left paw was 6.97 ± 4.65 SEM in the injury only group while in vector control group the mice did not grip (0 ± 0 SEM). By 56 days post-injury, average grip strength was 10.14 ± 10.14 SEM in the injury only group and 4.38 ± 4.38 SEM in the AAV-GFP group. There was some additional increase in average grip strength of the left paw for the 2 control groups from 77–98 days post injury (Fig 3A). In contrast, grip strength of the right paw remained low for both control groups throughout the post-operative testing period (average of 10 or less, see Fig. 3B). Differences in gripping ability between left and right paws in the control groups indicate asymmetry in functional loss, which may reflect asymmetry in lesions.

The pattern of recovery of gripping ability was much different in mice that received AAV-CRE. In particular, the left paw of AAV-CRE treated mice recovered grip strength earlier and reached a higher level at late post-lesion intervals than either the right paw or either paw of the control groups (Fig 3A). By 21 days post-injury, average grip strength of the PTEN-deleted group was 17.41±7.58 SEM whereas the mice in both control groups did not grip (0 ± 0 SEM in both). At 35 days, average grip strength in PTEN-deleted mice was almost half of the preoperative value (25.68 ± 7.38 SEM) and at 56 days the gripping force was 35.68 ± 11.41 SEM. By 84 days, values for the PTEN deleted group were actually higher than the preoperative baseline (53.85 ± 11.42 SEM) and became significantly different than those from the right paw (p<0.05) and this persisted until the end of testing (52.06 ± 13.36 SEM). While the increase in gripping recovery with the left paw in the PTEN-deleted group was substantially higher through our testing time when compared with control groups, differences were not significantly different from the control vector until 98 days post-injury Repeated measures ANOVA: F=2.87; p<0.05, Fig 3A).

To better illustrate the differences in recovery patterns between paws, Figure 4 directly compares data for left vs. right paws in the 3 groups. In the AAV-CRE group, the gripping force of the left paw was consistently higher than the right paw from 21 days post-injury. Post hoc comparisons with Bonferroni correction revealed that differences were statistically significant at 77 and 84 days (Repeated measures ANOVA: F=5.61, p<0.05, see Figure 3D). Although the gripping force for the left paw in the two control groups was also slightly higher across the testing period suggesting some asymmetry in lesions, these differences were not statistically significant in either the injury only or vector control group (Repeated measures ANOVA: F=1.91; P=0.18) or AAV-GFP group (F=1.32; P= 0.27, Fig 3E&F).

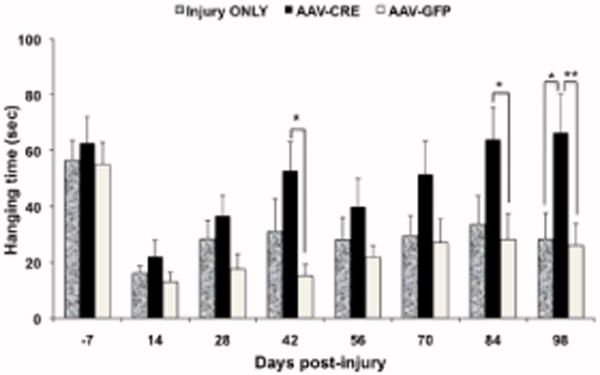

Fig. 4. PTEN deletion 20 min post-injury enhances grasping ability PTENloxP/loxP mice.

The graph represents the hanging time (sec) before and 98 days post injury in all three groups. Note that the hanging time that reflects the grasping ability remains steady through the study in control groups while in the PTEN deleted group the hanging time increases progressively over time. The results are presented as mean ± SEM, n=8–9 per group. Data were analyzed using Repeated Measures ANOVA with Bonferroni as post-hoc test. A value of *P<0.05, **P<0.01 was considered statistical significantly different when compared with control groups.

Since gripping force with both paws simultaneously is a reflection of both left and right paws gripping ability we next assessed the grip strength with both paws for all three groups. As observed with individual forepaws, the gripping force with both paws was impaired until 77 days, in both vector control 0 ± 0 SEM and injury only 4.45 ± 0 SEM groups (Fig 3C). There was slight recovery at about 84 days post-injury as observed in left and right paws in both controls. In the PTEN deleted group, there was some recovery of gripping with both paws simultaneously at 35 days (10.51 ± 10.51 SEM); gripping force remained fairly constant up to 77 days (13.19 ± 13.19 SEM), increasing slightly thereafter until the final testing day when griping force was 28 ± 15.72 SEM (Repeated measures ANOVA: F=1.15 and P=0.3354).

Hanging ability

Mice were not tested for their ability to hang from the bar until 14 days post injury, at which time, hanging ability was impaired to the same extent in all groups (Figure 4). Mice failed to grasp with both paws leading to falls. Average hanging time increased slightly at 28 days post-injury in the injury only group, but then remained stable at longer post-injury intervals. In the AAV-GFP group, average hanging time remained low until about 56 days post-injury when it increased slightly and then remained stable for the remainder of post-injury testing. In contrast, hanging time increased progressively over time in the PTEN-deleted group and was statistically different from control vector at 42 and 84 days (p<0.05). On the final testing day, hanging times for control groups were 26.2 8 ± 7.7 SEM (AAV-GFP) and 28.33 ± 9.37 SEM (injury only), vs. 66.5±13.79 SEM for the PTEN-deleted group. Repeated measures ANOVA revealed an overall difference between groups (F=3.79; P=0.0386); post-hoc assessments with Bonferroni correction revealed that on the final day of testing, the PTEN deleted group differed significantly from both control groups (P<0.01 and P<0.05 respectively).

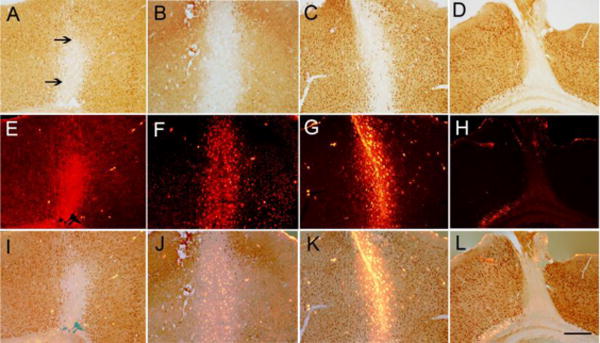

Documentation of PTEN deletion by immunostaining

In sections through the sensorimotor cortex that were immunostained for PTEN, the area of PTEN deletion was evident as a blank area in which there was no immunostaining (Figure 5A–C). The area of PTEN deletion ranged from 100 μm (anterior/posterior) to 1200 μm (dorsal/ventral). Table 5 documents the area of PTEN for each animal in this study.

Fig. 5. PTEN deletion and mini-ruby BDA labeling in brain coronal sections in PTEN-deleted mouse.

Panels A–C illustrate patterns of PTEN deletion in different mice after AAV-CRE injection into the right sensorimotor. Note brown PTEN labeled neurons surrounding the area of PTEN deletion. Panels E–H illustrate mini-ruby BDA labeling in the same section. Panels I–K illustrate the mini-ruby-BDA overlapped with an area of PTEN deletion. Note intense BDA labeling in PTEN deleted neurons. Panels D–L indicate a case with a small lesion surrounding the needle track with no overlap between BDA and PTEN deletion. The arrows indicate the PTEN deleted neurons. Scale bar 250 μm

Table 5.

Comprehensive description of PTEN-deleted area in sensorimotor cortex

| Animal # | PTEN-deleted area (μm) | |

|---|---|---|

| Anterior-Posterior | Dorsal-Ventral | |

| # 4 | 200–300 | 800 |

| # 7 | 100–200 | 600 |

| # 14 | 200 | 1200 |

| # 2B33 | 200 | 600 |

| # 734A | 100–200 | 1000 |

| # 4909 | 100 | 600 |

| #7147 | 200 | 800 |

| #440E | 100–200 | 800 |

| # 0E08 | 100–300 | 1100 |

Assessment of regenerative growth of CST axons

Our goal was to trace CST projections from cortical motoneurons in which PTEN had been deleted. Accordingly, we assessed whether BDA injections targeted the area of PTEN deletion (Fig 5E–G) or targeted parts of the cortex in which PTEN expression was maintained. For this purpose, series of sections were immunostained for PTEN and nearby sections were imaged for mini-ruby BDA fluorescence. Figure 5I–K illustrates examples in which mini-ruby BDA fluorescence overlapped with an area of PTEN deletion. BDA-labeled neurons were evident in most cases, whereas in one case (Fig 5E) the BDA labeling was diffuse. Table 6 summarizes the degree of overlap between the mini-ruby BDA injection sites and area of PTEN deletion in the different cases. In all animals there was good overlap between the BDA injection site and area of PTEN deletion at the two anterior injection sites 0.5mm and −0.2mm Anterior/Posterior (A/P) with respect to bregma. However in two cases the cortex was damaged during the surgical procedures so that the overlap could not be assessed. Fig 5D illustrates a case with a small lesion surrounding the needle track with no overlap between BDA and PTEN deletion (Fig 5L). At the posterior 2 injection sites −0.5mm and −1mm A/P, the mini-ruby BDA injection clearly targeted part of the cortex in which PTEN expression was maintained. In two mice, the extent of overlap could not be assessed because of damage to the section. In the cases in which the BDA injection did not overlap the area of PTEN deletion, some of the BDA labeled CST axons in the spinal cord would originate from cortical motoneurons with preserved PTEN expression.

Table 6.

PTEN/BDA co-localization at different injection sites: 0.5mm, −1mm, −0.5mm and −1mm anterior/posterior (A/P) with respect to bregma.

| Animal # | Injection site #1 | Injection site #2 | Injection site #3 | Injection site #4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| #4 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| #7 | Yes | Yes | Cortex damaged | No |

| #14 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| #2B33 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| #734A | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| #4909 | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| #7147 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| #440E | Cortex damaged | Yes | Cortex damaged | No |

| #0E08 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Distribution of BDA-labeled CST axons in the spinal cord

The overall extent of BDA labeling of CST axons in the spinal cord was first assessed in cross sections taken rostral to the lesion. In 18 mice, there were large numbers of BDA-labeled axons in the ventral part of the dorsal column (the main component of descending CST axons) on the side contralateral to the injection. Figure 6A–C illustrates different cases with heavy labeling. In these and other cases, the labeled axons in the DCST were too numerous to count accurately. In 5 mice, the overall extent of labeling was sparse (an example of a case with sparse labeling is illustrated in Fig. 6D); these mice were not included in the analyses of CST axon distribution.

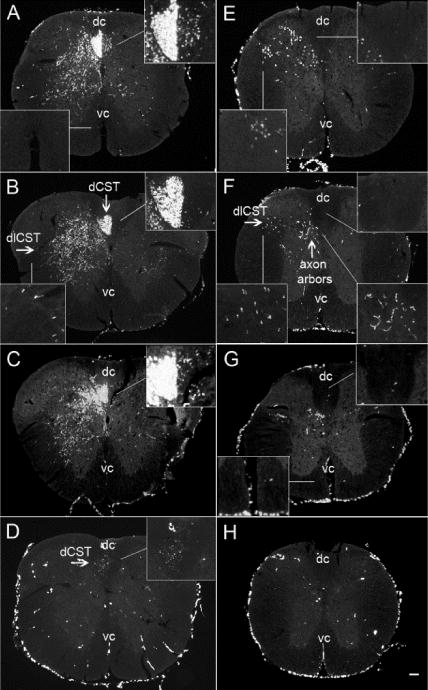

Fig. 6. Examples of BDA labeling in cross sections of spinal cord rostral (A–D) and caudal (E–H) to the lesion.

Panels A–D illustrate different cases of BDA-labeling in cross sections taken rostral to injury and the representative caudal parts are presented in panels (E–H). Different patterns of the BDA labeling in the ventral part of the dCST ipsilateral to the injection site: (A) heavy labeling, (B) 7 axons and (C) 43 axons. Panel (D) shows an example of poor labeling of the dCST. Panels E–G illustrate BDA-labeled axons in the dlCST and in gray matter in the caudal cross sections. The lack of axons in the dorsal column indicates the complete destruction of the main tract of dCST. No BDA-labeled axons were found in the ventral column. Panel H shows the caudal cross sections from a case with a poor labeling (dc = dorsal column and vc = ventral column); scale bar 100 μm

BDA labeled CST axons were also found in the dorsal part of the lateral column (dorsolateral CST) (Table 7) and a small number of labeled axons were also seen in the dorsal column ipsilateral to the injection. In one mouse from the vector control group an unusually large number of axons were found in the ventral part of the dorsal column ipsilateral to the injection (the “wrong” side, see Fig 6A), while in 8 out of 23 mice the average number of BDA-labeled CST axons in the dCST ipsilateral to the cortex of origin ranged between 12–43 (Fig 6C). In the rest of mice (14 out of 23) the number of BDA-labeled axons in the dCST ipsilateral to the injection ranged between 0–8 (Fig 6B). There were no BDA labeled axons tracking along the ventral column ipsilateral to the injection in the position of the ventral CST in the control groups, although some collaterals extended down into the ventral column from the gray matter on the side contralateral to the injection as previously reported (Steward et al., 2008). In two mice in PTEN deleted group, however, a few BDA labeled axons were seen tracking along the ventral column (Table 7).

Table 7.

The number of BDA-labeled axons in rostral and caudal part. The numbers represent the average of counts per 2–3 sections.

| Animal # | ROSTRAL PART | CAUDAL PART | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| dCST | dICST | Ventral column | dCST | dICST | Gray matter | Ventral column | |

| #9 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 14 | 0 | 0 |

| #2A6E | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| #6962 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| #4509 | 92 | 13 | 0 | 5 | 19 | 52 | 0 |

| #613B | 12 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 6 | 0 |

| #0E08 | 2 | 12 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 14 | 0 |

| #7147 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 0 |

| #3 | 2 | 23 | 0 | 0 | 15 | 11 | 0 |

| #5448 | 2 | 11 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| #2B33 | 6 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| #734A | 17 | 21 | 2 | 0 | 14 | 19 | 0 |

| #4909 | 12 | 20 | 1 | 3 | 11 | 10 | 0 |

| #2D7F | 6 | 12 | 0 | 1 | 51 | 47 | 0 |

| #7A2B | 2 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 10 | 0 |

| #2054 | 13 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 0 |

| #6041 | 17 | 19 | 0 | 5 | 43 | 39 | 0 |

| #377B | 5 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 19 | 0 |

| #7 | 8 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| #4 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| #6 | 11 | 21 | 0 | 2 | 22 | 27 | 0 |

| #12 | 43 | 12 | 0 | 1 | 8 | 13 | 0 |

| #14 | 7 | 20 | 0 | 1 | 19 | 15 | 0 |

| #1243 | 21 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

Next, we examined cross sections from the caudal block (Fig 6E–H) for the presence of BDA-labeled axons in the dorsal column, which would indicate incomplete destruction of the dorsal CST. In 15 of 23 mice, there were no labeled axons in the dCST indicating that the contusion injury destroyed the main component of CST axons in the dCST (Fig 6G), while in 8 out of 23 mice, there were very few labeled axons between 1–5 (Fig 6E–F). Figure 6H shows an example of poor BDA labeling. No BDA labeled axons were found tracking along the ventral column in the expected position of the ventral CST (Fig 6E–H).

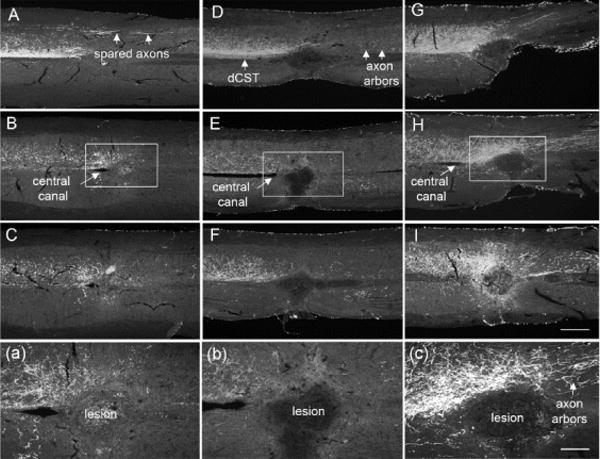

Next we evaluated the collections of serial horizontal sections through the lesion block. Fig 7 shows serial horizontal sections from injury only (Fig 7A–C) and vector control (Fig 7D–F) groups. In all cases, the main component of BDA-labeled axons in the dorsal CST was largely destroyed. BDA labeled axons in the dorsal column terminated in retraction balls rostral to the injury, typical for injured axons in control groups. BDA labeled axons could be seen extending past the lesion in the dorsal part of the lateral column (the dlCST) and in some cases BDA-labeled axon arbors could be seen extending from the dlCST into the gray matter in caudal segments in control groups (Fig 8). Thus, the BDA labeled axon arbors in caudal segments in the control groups likely originate from the dlCST.

Fig. 7. Regeneration of CST axons after PTEN deletion in PTENf/f mice.

Images of 3 serial horizontal sections from the spinal cords starting from the dorsal part (A, D, G) to about 80μm ventral (C, G, K) to the central canal (B, F, H) in injury only (A–C), AAV-GFP (D–F) and AAV-CRE (G–I) groups. Note: the main component of the dCST was destroyed in all three groups. Abundant axon arbors were present in AVV-CRE group and few spared axons caudal to the lesion were observed in vector control group. Note: BDA labeled axons passing the lesion were observed only in PTEN-deleted group (C). Panels (a), (b) and (c) illustrate higher magnification view; scale bar 500μm for A to I panels and 200μm for a–c.

Fig. 8. Examples of axon arbors extending from the dlCST into the gray matter caudal to lesion in injury only (A) and vector control (B) groups.

The arrows indicate the extended axons from the dlCST into the gray matter; scale bar 100μm.

AAV-driven expression of GFP can be used for orthograde tracing of axons. To determine whether GFP labeling could be used to trace CST axons in mice that received AAV-GFP, sections rostral to the injury were immunostained for GFP. Only a few GFP-positive axons were detected in the location of the dCST, and no GFP-labeled axon arbors were detectable. The lack of GFP-labeling is likely due to the fact that AAV-driven expression decreases over time and would likely be minimal at the long survival times here (data not shown).

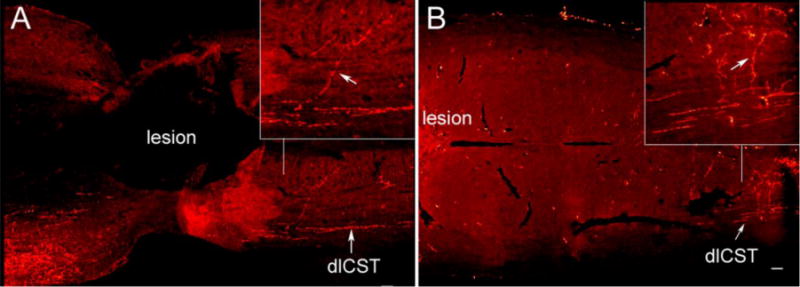

In contrast, CST axon distribution was qualitatively different in the PTEN-deleted group (Fig 7G–I). Abundant collaterals extended from the main tract rostral to the lesion, and some extended across the midline and into or around the scar tissue at the injury site. BDA-labeled axons were also present in the ventral gray matter caudal to the lesion in PTEN-deleted mice. BDA labeled axons were also observed extending bilaterally caudal to the lesion while others had an abnormal trajectory with axons located outside their normal topography suggesting regenerative growth (Fig 9A). In one mouse with the mixed matrix/cavity, BDA labeled axons extended into the scar, forming a bridge between two parts of the lesion (Fig 9B).

Fig. 9. Examples of axon re-growth in 2 different PTEN-deleted mice.

Panel A illustrates BDA labeled axons with a wrong trajectory outside their normal topography. Panel B represents an example where BDA labeled axons extended into the scar between two parts of the fibrous/cystic cavity lesion. The arrows indicate the extended axons into the scar; scale bar 100μm.

Quantitative assessments of CST axons

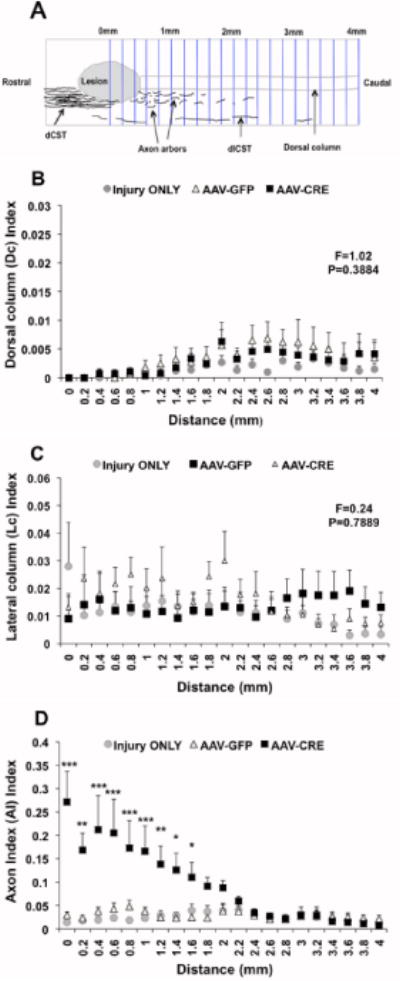

For the quantitative analysis, we quantified the axons extending into and caudal to lesion site in the serial horizontal sections. CST axons were assessed at 0.2mm intervals through the entire spinal cord caudal to the lesion side in three different regions as follows: dorsal column, lateral column and gray matter (Fig 10A). To control for differences in the overall extent of BDA labeling, we counted the total number of BDA-labeled axons in cross sections from the rostral part above the lesion.

Fig. 10. Quantification of CST axons.

Panel A shows the axon count diagram. Panel B and C illustrate the axon quantification in dorsal column and lateral column respectively. Note: The number of axons in dorsal and lateral columns was not statistical different among all groups at any given distance caudal to the lesion. Panel D represents the axon arbors quantification in the gray matter below the lesion. The axon arbors were abundant in PTEN-deleted group when compared with controls. The results are presented as mean ± SEM, n=4–6/group. Data was analyzed using Repeated Measures ANOVA with Bonferroni as post-hoc test. Values of ***P<0.001, **P<0.01, *P<0.05 were statistically significant different from control groups.

As previously reported (Aguilar et al., 2011) the C5 contusion injury destroyed almost all CST axons in the dorsal column in all three groups as revealed by counts of BDA labeled axons in the dorsal column at different distances from the injury site (Figure 9). The counts are expressed as Dorsal column (Dc) Index in which the number of axons in the dorsal column caudal to the injury is divided by the total number of BDA-labeled axons rostral to the injury. The Dc Index was very small among groups about 0.001 at 1mm, and 0.004 at either 2 or 3mm distance from the injury side (F=1.02, P=0.3884).

As shown in previous studies (Aguilar et al., 2011) the C5 contusion injury model usually spares the dlCST, and our results confirmed this. Counts of BDA-labeled axons in the dorso-lateral column are expressed as the Lc Index (number of axons in the lateral column caudal to the injury divided by the total number of BDA-labeled axons rostral to the injury). The Lc index was on average 0.02 at the lesion site, 0.02 at 1mm, 0.024 at 2mm and 0.017 at 3mm beyond the lesion (Repeated measures ANOVA: F=0.24, P=0.7889) (Fig 10C).

To quantify axon arbors in the gray matter caudal to the injury, counts were expressed as arbor index (AI), in which arbor counts were divided by the total number of BDA-labeled axons rostral to the injury. The AI was 0.29 at the middle site of the lesion (0mm) in the PTEN deleted group compared with 0.014 in injury only or 0.029 control vector groups (P<0.001). In PTEN deleted mice, the number of BDA labeled axons was significantly different from controls at every distance up to 1.4 mm caudal to the lesion (F=8.46, P=0.0051) and still higher than controls at 2mm as shown in Fig 10D. There was no statistically significant difference in the AI Index between experimental groups at 3mm and 4mm distance from the lesion (Repeated measures ANOVA: P>0.05).

DISCUSSION

Our goals in this study were to determine whether conditional genetic deletion of PTEN in mature cortical motoneurons can enable regenerative growth of CST axons after SCI, and whether enhanced regeneration would improve forelimb gripping and grasping function in a clinically-relevant model (C5 contusion). Our results reveal that mice that received AAV-Cre injections to delete PTEN 20 minutes after a moderate contusion at C5 exhibited enhanced gripping and grasping performance in tasks in which the CST is thought to be critical and enhanced regenerative growth of the CST in comparison to control groups. This supports the conclusion that it is possible to enhance regenerative by deleting PTEN in adult neurons and in a time frame that is more therapeutically relevant than previous approaches in which PTEN was deleted at P1, long before the time of a spinal cord injury. In what follows, we discuss these findings in the context of previous studies and consider caveats.

The effect of PTEN gene deletion in enhancing axon regeneration has been described before in different models. In an optic nerve crush model, (Park et al, 2008) showed that conditional genetic deletion of PTEN in adult retinal ganglion cells (RGCs) is sufficient to initiate the regenerative program for axon growth. Next, (Liu et al 2010) demonstrated that conditional genetic deletion of PTEN in the sensorimotor cortex at P1 enhanced CST regeneration following two types of spinal cord injuries in adult mice: a dorsal hemisection and a complete crush at thoracic level 8 (T8). Recently (Zukor et al, 2013) showed that deletion of PTEN in neonatal mice (P0/P1) using shRNA against PTEN (AAV-shPTEN-GFP) also enabled regenerative growth of CST axons following spinal cord injury at T8 in adults. Also, (Ohtake et al, 2014) demonstrated that PTEN inactivation using systemic PTEN antagonist peptides (PAPs) treatment after a dorsal hemitransection injury at T7 led to increased density of serotonergic fibers in the caudal spinal cord and enhanced sprouting of CST axons rostral to the lesion. These latter studies represent another step toward establishing clinical relevance by showing that expression of native PTEN can be knocked down with shRNA or inactivated by systemic PAPs treatment to enhance axon growth potential.

The present study differs in several ways from previous studies, and takes additional steps toward potential clinical relevance. First, although we used a conditional genetic model for PTEN deletion as did Liu et al, the AAV-Cre mediated deletion was accomplished in adult mice at the time of a spinal cord injury. Second, the injury model used in this study was a moderate cervical contusion at C5 centered on the midline of the spinal cord that produced bilateral tissue damage and bilateral function deficits. We chose this injury model for its human relevance. More than 50% of spinal cord injuries are at the cervical level, impairing both lower and upper extremities and the most common type of injury in humans is the contusive type. Moderate C5 contusions resulted in profound bilateral deficits in forelimb motor function. Consistent with our previous studies (Aguilar et al., 2010), there was minimal urine retention even during the early post-injury period. None of the mice exhibited autophagia, and only one mouse exhibited excessive weight loss. General health was acceptable with mice being able to function independently within 5 days post-injury.

Measures of forelimbs’ gripping and grasping function

The grip strength meter (GSM) yields quantitative and reproducible measures of flexor strength of the digits, is simple and minimally stressful and allows independent assessment of each forepaw. Assessment of each forepaw independently was important because AAV-CRE was injected unilaterally into the right motor cortex, allowing comparisons of recovery of the paw controlled by the PTEN-deleted cortex vs. the contralateral side, which provides an internal control. There was greater recovery by the paw controlled by the injected (right) side of the cortex (the left paw). Grip strength in the left paw of the PTEN-deleted group increased earlier and recovered to a higher level at late post-lesion intervals. An underlying assumption is that the laterality of control still exists following PTEN deletion and injury. In this regard, one feature of enhanced CST axon growth is bilateral extension near the injury site, which could disrupt the normal laterality of function. There was also slightly greater spontaneous recovery of the left paw in injury only and vector control groups, although differences between paws were not statistically significant. This could be due to a slight asymmetry in the lesion that might influence the degree of sparing in the dlCST. Previous studies showed that spared CST axons could contribute to behavioral recovery following injury (Kartje-Tillotson et al 1987; Thallmair et al 1998).

Data from the hanging task also indicated enhanced forepaw grasping ability in PTEN deleted mice, and the recovery was more pronounced after 10–12 weeks of testing. We employed the hanging task because it was simple, quantitative, and produced consistent results over time. Contusion injury impaired hanging ability in all tree groups. In control groups, hanging ability was slightly improved at the 28 day testing point, but did not improve further, whereas hanging ability continued to increase in the PTEN deleted group indicating continuing recovery.

Relevance of the GSM and hanging task to the CST

Our studies focus on the CST because it is the major pathway controlling voluntary motor function, especially forelimb motor function. Studies in humans indicate that the CST mediates fine motor control of the distal arm and hand (Schieber et al 2007) and evidence from experimental animals support this conclusion. Lesions of the pyramidal tract in hamsters lead to deficits in execution of precise manipulation of the digits (Kalil and Schneider, 1975). In rats, damage to the CST in the brain or spinal cord impairs forelimb motor function during skilled movements (Whishaw et al, 1998, 2002; Anderson et al 2005; Kanagal and Muir 2008). However, lesions of the rubrospinal system also impair forelimb function during skilled movements (Muir et al 2007; Whishaw et al 1992, 1998; Schrimsher and Reier, 1993) suggesting that other descending pathways could also be important in forelimb recovery.

The GSM and hanging task assess flexor and general forelimb strength, and there is evidence that at least the GSM depends on the integrity of the sensorimotor cortex in mice (Blanco et al., 2007) and rats (Strong et al. 2009). Nevertheless, it is an open question whether these functions can truly be called “voluntary” in the same sense as the skilled manipulative tasks that are tested by pellet retrieval (Whishaw et al 1992, 1998). In this regard, a companion paper reports enhanced recovery of forelimb motor function following PTEN deletion and salmon fibrin implantation at the injury site in a task that does involve pellet retrieval (Lewandowski et al 2014).

Analysis of regenerative growth of CST axons

Analyses of BDA-labeled CST axons revealed that contusion injuries almost completely destroyed the main component of the dorsal CST in all groups. However, we found a small number of BDA-labeled axons in the lateral column in all three groups indicating sparing of the dlCST, which can be a source of sprouting. Histological analysis revealed that in control groups, there were a few axon arbors in the gray matter caudal to the lesion. Studies of mice in which the main tract in the dorsal column had been completely transected at the thoracic level revealed that some axons coming from the dlCST arborized extensively through the dorsal and ventral horns at caudal levels often extending across the midline to arborize on the contralateral side (Steward et al 2004). These extensive arbors could reflect sprouting from spared dlCST axons.

The distribution of BDA labeled axons was different in the PTEN deleted group in two ways. First, there was a bloom of axons rostral to the lesions, and axons extended into and around the lesion with exuberant axon arborization ventrally in the gray matter below the lesion. Second, quantitative assessment of BDA labeled axons showed larger numbers of CST axons caudal to the injury in the PTEN deleted group.

The regenerative growth seen here resembles what has been previously reported following spinal cord injury with either conditional genetic deletion of PTEN at P0/P1 (Liu et al 2010) or with AAV-shPTEN injections at P1 to knockdown PTEN (Zukor et al 2013). The extent of the regenerative growth appears less extensive, however, although direct comparisons are difficult because the site and nature of the injury is different (C5 contusion vs. T8 dorsal hemisection or crush). Further studies will be required to address this issue.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrates enhanced recovery of forepaw gripping and grasping function and enhanced regenerative growth of injured CST axons with conditional genetic deletion of PTEN in adult mice shortly after a spinal cord injury. These results suggest that manipulations of PTEN or the downstream mTOR pathway may be a viable target for therapeutic interventions to promote axon regeneration after spinal cord injury.

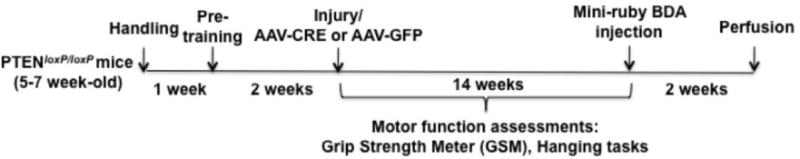

Fig. 1. Experimental design.

The timeline indicates periods during which different procedures were carried out.

Research Highlights.

Deletion of PTEN in adult corticospinal neurons enhances regenerative growth capacity

Regenerative growth of CST axons enhances recovery of forelimb motor function

Post-SCI interventions can enable regenerative axon growth

Acknowledgments

Supported by R01 NS047718 to O.S., and generous donations from Cure Medical, Research for Cure, and individual donors. Thanks to Kelli Sharp, Robert Aguilar, Ardi Gunawan, Jennifer Yonan, and Kelly Yee for assistance in surgical procedures, animal care and testing, and neurohistology.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Commercial Interest: Oswald Steward is one of the co-founders of a company called “Axonis” which holds options on patents relating to PTEN deletion and axon regeneration.

References

- Aguilar RM, Steward O. A bilateral cervical contusion injury model in mice: assessment of gripping strength as a measure of forelimb motor function. Exp Neurol. 2010;221(1):38–53. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2009.09.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson KD, Gunawan A, Steward O. Quantitative assessment of forelimb motor function after cervical spinal cord injury in rats: relationship to corticospinal tract. Exp Neurol. 2005;194(1):161–74. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2005.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson KD, Sharp KG, Steward O. Bilateral cervical contusion spinal cord injury rats. Exp Neurol. 2009;220(1):9–22. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2009.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco JE, Anderson KD, Steward O. Recovery of forepaw gripping ability and reorganization of cortical motor control following cervical spinal cord injuries in mice. Exp Neurol. 2007;203(2):333–48. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2006.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cafferty WB, Duffy P, Huebner E, Strittmater SM. MAG and OMgp synergize with Nogo-A to restrict axonal growth and neurological recovery after spinal cord trauma. J Neurosci. 2010;30(20):6825–6837. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6239-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai D, Qiu J, Cao Z, McAtee M, Bregman BS, Filbin MT. Neuronal cyclic AMP controls the developmental loss in ability of neurons to regenerate. J Neurosci. 2001;21(13):4731–9. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-13-04731.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dang DT, Pevsner J, Yang VW. The biology of the mammalian Kruppel-like family of transcription factors. IJBCB. 2000;(32):1103–1121. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(00)00059-5. Review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener PS, Bregman BS. Fetal spinal cord transplants support the development of target reaching and coordinated postural adjustments after neonatal cervical spinal cord injury. J Neurosci. 1998;18(2):763–78. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-02-00763.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg JL. Intrinsic neuronal regulation of axon and dendrite growth. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2004;14(5):551–557. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2004.08.012. Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellstrom M, Muhling J, Ehlert EM, Verhaagen J, Pollett MA, Hu Y, Harvey AR. Negative impact of rAAV2 mediated expression of SOCS3 on the regulation of adult retinal ganglion cell axons. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2011;46(2):507–15. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2010.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalil K, Schneider GE. Retrograde cortical and axonal changes following lesions of the pyramidal tract. Brain Res. 1975;89(1):15–27. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(75)90130-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanagal SG, Muir GD. The differential effects of cervical and thoracic dorsal funiculus lesions in rats. Behav Brain Res. 2008;187(2):379–86. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2007.09.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kartje-Tilllotson G, O’Donoghue DL, Dauzvardis MF, Castro AJ. Pyramidotomy abolishes the abnormal movements evoked by intracortical microstimulation in adult rats that sustained neonatal cortical lesions. Brain Res. 1987;415(1):172–7. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(87)90283-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewandowski G, Steward O. AAVshRNA-mediated suppression of PTEN in adult rats in combination with salmon fibrin administration enables regenerative growth of corticospinal axons and enhances recovery of voluntary motor function after cervical spinal cord injury. J Neurosci. 2014;34:9951–9962. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1996-14.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu K, Lu Y, Lee JK, Samara R, Willenberg R, Sears-Kraxberger I, Tedeski A, Park KK, Jin D, Cai B, Xu B, Connolly L, Steward O, Zheng B, He Z. PTEN deletion enhances the regenerative ability of adult corticospinal neurons. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13(9):1075–81. doi: 10.1038/nn.2603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma XM, Blenis J. Molecular mechanisms of mTOR mediated translational control. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10(5):307–18. doi: 10.1038/nrm2672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore DL, Apara A, Goldberg JL. Kruppel-like transcription factors in the nervous system: novel players in neurite outgrowth and axon regeneration. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2011;47(4):233–43. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2011.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muir GD, Webb AA, Kanagal S, Taylor L. Dorsolateral cervical spinal injury differentially affects forelimb and hindlimb action in rats. Eur J Neurosci. 2007;25(5):1501–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05411.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohtake Y, Park D, Abdule-Muneer PM, Li H, Xu B, Sharma K, Smith GM, Selzer ME, Li S. The effect of systemic PTEN antagonist peptides on axon growth and functional recovery after spinal cord injury. Biomaterials. 2014;35:4610–4626. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.02.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park KK, Liu K, Hu Y, Smith PD, Wang C, Cai B, Xu B, Connolly L, Kramvis I, Sahin M, He Z. Promoting axon regeneration in the adult CNS by modulation of the PTEN/mTOR pathway. Science. 2008;322(5903):963–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1161566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodger J, Goto H, Cui Q, Chen PB, Harvey AR. cAMP regulates axon outgrowth and guidance during optic nerve regeneration in goldfish. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2005;30(3):452–64. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2005.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabatini DM. mTOR and cancer: insights into a complex relationship. Nat Rev cancer. 2006;6(9):729–34. doi: 10.1038/nrc1974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schieber MH, Rivlis G. Partial reconstruction of muscle activity from a pruned network of diverse motor cortex neurons. J Neurophysiol. 2007;97(1):70–82. doi: 10.1152/jn.00544.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrimsher GW, Reier PJ. Forelimb motor performance following dorsal column, dorsolateral funiculi, or ventrolateral funiculi lesions of the cervical spinal cord in the rat. Exp Neurol. 1993;120(2):264–76. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1993.1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selzer ME. Promotion of axon regeneration in the injured CNS. Lancet Neurol. 2003;2(3):157–66. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(03)00322-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith PD, Sun F, Park KK, Cai B, Wang C, Kuwako K, Martinez-Carrasco I, Connolly L, He Z. Socs3 deletion promotes optic nerve regeneration in vivo. Neuron. 2009;64:617–623. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.11.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steward O, Zheng B, Ho C, Anderson K, Tessier–Lavigne M. The dorsolateral corticospinal trct in mice: an alternative route for corticospinal input to caudal segments following dorsal column lesions. J Comp Neurol. 2004;472(4):463–77. doi: 10.1002/cne.20090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strong MK, Blanco JE, Anderson KD, Lewandowski G, Steward O. An investigation of the cortical control of forepaw gripping after cervical hemisection injuries in rats. Exp Neurol. 2009;217(1):96–107. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2009.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun F, He Z. Neuronal intrinsic barriers for axon regeneration in the adult CNS. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2010;20(4):510–8. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2010.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun F, Park KK, Belin S, Wang D, Lu T, Chen G, Zhang K, Yeung C, Feng G, Yankner BA, He Z. Sustained axon regeneration induced by co-deletion of PTEN and SOCS3. Nature. 2011;480:372–375. doi: 10.1038/nature10594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang X, Davies JE, Davies SJA. Changes in distribution, cell associations, and protein expression levels of NG2, neurocan, phosphocan, brevican, versicanV2, and tenascin-C during acute to chronic maturation of spinal cord scar tissue. J Neurosci Res. 2003;71(3):427–444. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thallmair M, Metz GA, Z’Graggen WJ, Raineteau O, Kartje GL, Schwab ME. Neurite growth inhibitors restrict plasticity and functional recovery following corticospinal tract lesions. Nat Neurosci. 1998;1(2):124–131. doi: 10.1038/373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verma P, Chierzi S, Codd AM, Campbell DS, Meyer RL, Holt CE, Fawcett JW. Axonal protein synthesis and degradation are necessary for efficient growth cone regeneration. J Neurosci. 2005;25(2):331–42. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3073-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wanner IB, Deik A, Torres M, Rosendahl A, Neary JT, Lemmon VP, Bixby JL. A new in vitro model of the glial scar inhibits axon growth. Glia. 2008;56(15):1691–709. doi: 10.1002/glia.20721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whishaw IQ, Pellis SM, Pellis VC. A behavioral study of the contribution of cells and fibers of passage in the red nucleus of the rat to postural righting, skilled movements, and learning. Behav Brain Res. 1992;52(1):29–44. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(05)80322-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whishaw IQ, Sarna JR, Pellis SM. Evidence for rodent-common and species typical limb and digit use in eating, derived from a comparative analysis of ten rodent species. Behav Brain Res. 1998;96(1–2):79–91. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(97)00200-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whishaw IQ, Metz GA. Absence of impairments or recovery mediated by the uncrossed pyramidal tract in the rat versus enduring deficits produced by the crossed pyramidal tract. Behav Brain Res. 2002;134(1–2):323–336. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(02)00051-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zukor K, Belin S, Wang C, Keelan N, Wang X, He Z. Short hairpin RNA against PTEN enhances regenerative growth of corticospinal tract axons after spinal cord injury. J Neurosci. 2013;33(39):15350–61. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2510-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]