Abstract

Sturge–Weber syndrome (SWS), also called as encephalotrigeminal angiomatosis is an uncommon congenital neurological disorder & frequent among the neurocutaneous syndromes specifically with vascular predominance. This disorder is characterized by facial capillary malformation & other neurological condition. The oral manifestations are gingival hemangiomatosis restricting to either side in upper and lower jaw, sometimes bilateral. We report a case of SWS with oral, ocular and neurological features.

Keywords: Sturge–Weber syndrome, Port-wine stains, Gingival enlargement

1. Introduction

Sturge–Weber syndrome (SWS), also called as encephalotrigeminal angiomatosis, is a rare non-hereditary condition characterized by a facial cutaneous vascular nevus (nevus flammeus or port-wine stain) in association with leptomeningeal angiomatosis.1 Schirmer was first one to describe it nearly a century ago (1860) in association with facial angioma and buphthalmos. Later in 1879 while reporting a case of 6½ year old girl, William Allen Sturge acclaimed these features in accordance with neurological findings and termed it as Sturge–Weber syndrome.2 There is a risk of 10–50 % for the involvement of brain if a child is born with Port-wine birthmark (PWB) on the forehead or the upper eyelid. When the upper and lower eyelids are involved in port-wine birthmark, the risk of developing glaucoma becomes as high as 50%.3 The frequency of occurrence of SWS is between 1:20,000 and 1:50,000. Amongst these port-wine birthmark is the most common with the occurrence of 0.3% in live births.2 In 1992, Roach categorized SWS variants into three types:

-

•

Type I: individual has a facial PWS, leptomeningeal angioma, and may have glaucoma

-

•

Type II: individual has a facial PWS, no leptomeningeal angioma, and may have glaucoma

-

•

Type III: individual has leptomeningeal angiomatosis, no facial PWS, and, rarely, glaucoma.4

The aim of this article is to report a case of Sturge–Weber syndrome and add to the existing literature.

2. Case report

An 11 year old boy reported to the Department of Pedodontics & Preventive Dentistry, I.T.S. Dental College, Hospital & Research Center, Greater Noida with the chief complaint of bleeding gums in upper and lower right posterior tooth region & dental caries affecting upper left posterior teeth. The patient's mother gave a history of pain due to multiple mobile teeth since 1–2 months.

Medical history of the patient revealed that there was no history of epileptic seizures, but the patient gave history of multiple attacks of migraine during day time. The natal history of the child was non-contributory as it was a normal full term delivery without any complications.

General examination revealed no developmental delay in motor & speech function without any evidence of cardiovascular & respiratory disease.

Extra oral examination revealed the presence of port-wine stain on right side of face along the upper eyelid & forehead. These stains were seen extending over the right side of neck, shoulder & also extending up to scalp but not crossing the midline (Fig. 1a). The ocular examination revealed presence of suprascleral hemangiomas, indicative of initial glaucoma (Fig. 1b).

Fig. 1.

a: Port-wine stain on right side of face along the upper eyelid & forehead. These stains were seen extending over the right side of neck, shoulder & also extending up to scalp but not crossing the midline. b: Ocular examination revealing presence of suprascleral hemangiomas. c: Erythematous reddish pink patches were seen on the right side of the hard palate extending till the soft palate. d: Poor oral hygiene with gross calculus in the posterior region.

Intraoral examination revealed inflamed & hypertrophied gingiva of the right upper and lower quadrants. 64 was carious & 53, 55, 84, 85 were mobile. An OPG, lateral ceph & PA view skull was advised to check for resorption of roots, osteohypertrophy & calcifications in frontal lobe. The vascular nevus extended up to the underlying oral mucosa and gingiva. Erythematous reddish pink patches were seen on the right side of the hard palate extending till the soft palate (Fig. 1c). He had poor oral hygiene with gross calculus in the posterior region (Fig. 1d).

Based on the present finding provisional diagnosis of Sturge–Weber syndrome was made & patient was advised to go for the ophthalmic examination & Magnetic resonance imaging.

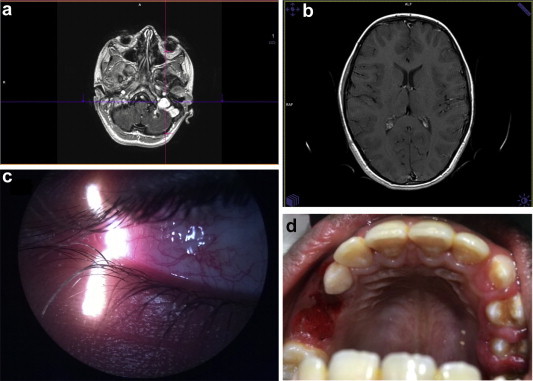

MRI with contrast revealed non-visualization of right sigmoid sinus and proximal internal jugular vein with attenuated caliber of right transverse sinus. Prominent venous channels were noted in the left posterolateral aspect of craniovertebral junction and there was prominent right vein of Labbe (Fig. 2a). MRI showed very mild changes in leptomeninges not significant enough to report (Fig. 2b).

Fig. 2.

a: Non-visualization of right sigmoid sinus and proximal internal jugular vein in MRI. b: Mild changes in leptomeninges at T1. c: Subscleral hemangiomas with right eye. d: Post operative maxillary arch after extractions.

Ocular examination revealed presence of subscleral hemangiomas with right eye (Fig. 2c). After complete presurgical laboratory blood test, patient was advised a thorough plaque control regimen. It included oral prophylaxis, use of chlorhexidine mouth rinses and oral hygiene maintenance. Extraction of grade II mobile teeth 54, 64, 65, 84, 85 were carried out under local anesthesia. Complete homeostasis was achieved with pressure pack & patient was kept under observation for 1 h then he was discharged with appropriate post operative instructions (Fig. 2d).

3. Discussion

Bioxeda et al5 in 1993 studied 121 patients with port-wine stains and found 88% of stains were predominantly distributed over maxillary branch of trigeminal nerve. In 1999, Inan & Marcus1 reported the presence of port-wine nevus up to 87–90% on right side of face. 50% patients showed lesion extension over midline & 33% showed bilateral involvement of the lesion.

SWS is an developmental anomaly of embryonic origin because of malformation in mesodermal and ectodermal development. It results due to failure of regression of a vascular plexus around cephalic portion of neural tube which is destined to become facial skin. This vascular plexus normally forms at 6th week of intrauterine life and regresses by 9th week. Failure of its regression results in residual vascular tissue which forms angiomas of leptomeninges, face and ipsilateral eye.6 Due to this there is abnormal flow of blood which in turns causes vasomotor phenomenon, resulting in ischemia, gliosis, atrophy, and calcification of the cortical tissues.

3.1. Imaging

Conventional skull radiographs are usually advised for visualizing the calcifications in frontal lobe2 OPG showed osteohypertrophy of the involved side. Lateral ceph & PA view skull failed to show any calcifications in the frontal lobe.

The recommended imaging modality to diagnose Sturge–Weber syndrome is Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).2 Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain was performed and high-resolution T1–T2 weighed serial sections obtained in the sagittal and axial planes. Contiguous fast FLAIR images were also obtained in the coronal plane on 1.5 T scanner using a dedicated 8-phased-array surface coil. Additional diffusion weighted images were obtained in the axial plane. T1-weighted serial sections were also obtained in the sagittal, axial and coronal planes after injection of intravenous contrast. In present case MRI showed very minimal changes which were not significant enough. This might be because of the young age of the child or the slow progression of angiomas towards the cortical areas.

3.2. Ocular examination

The choroidal hemangioma causes increased secretion of aqueous humor which in turns causes increased intra ocular tension & causes buphthalmos and glaucoma.7 Glaucoma, exudative retinal detachment (ERD) and heterochromia iridis may be present in 30–70% as ophthalmic manifestation.8 In the present case the authors report the subscleral hemangiomas under ophthalmoscopy.

4. Management

There is enough evidence based studies suggesting laser treatment for port-wine stains in early infancy. Anticonvulsant medications in combination with aspirin can be given for management of neurologic consequences. Surgical interventions are often needed in glaucoma as in association with SWS this doesn't respond to medical therapy.2 Photodynamic therapy and intravitreous bevacizumab is an upcoming treatment modalities for diffuse choroidal hemangioma.8 Correction of gingival enlargement can be done with gingivectomy and lasers as they have additional advantage of homeostasis and minimum damage to oral tissues.9 In the present case treatment plan which was carried out consisted of full mouth oral prophylaxis, and extractions of grade II mobile teeth 54, 84 & 85 under local anesthesia. Laser therapy would be employed to perform gingivectomy in this patient after the complete eruption of premolars.

5. Conclusion

SWS presents with varied clinical features. Available latest treatment modalities & thorough knowledge of this syndrome is very important in management of this condition. It is a multidisciplinary team work to deliver proper medical care to the patient. Complete understanding regarding the entire disorder should be imparted to caregivers. It is important that caregivers should perceive consequences of complications so that the patients are treated quickly and effectively.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have none to declare.

References

- 1.Reid D.E., Maria B.L., Drane W.E., Quisting R.G., Hoang K.B. Central nervous system perfusion and metabolism abnormalities in Sturge–Weber syndrome. J Child Neurol. 1997;12:218–222. doi: 10.1177/088307389701200313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sudarsanam A., Ardern-Holmes S.L. Sturge–Weber syndrome: from the past to the present. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2014 May;18:257–266. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpn.2013.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Enjolras O., Riche M.C., Merland J.J. Facial port-wine stains and Sturge–Weber syndrome. Pediatrics. 1985;76:48–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marx R.E., Stern D. Quintessence Publishing Co, Inc.; Chicago, IL, USA: 2003. Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology: A Rationale for Diagnosis and Treatment; pp. 224–226. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bioxeda P., de Misa R.F., Arrazola J.M. Facial angioma and the Sturge–Weber syndrome: a study of 121 cases. Med Clin (Barc) 1993;101:1–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aydin A., Cakmakçi H., Kovanlikaya A., Dirikss E. Sturge–Weber syndrome without facial nevus. Pediatr Neurol. 2000;22:400–402. doi: 10.1016/s0887-8994(00)00127-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Inan C., Marcus J. Sturge–Weber syndrome: report of an unusual cutaneous distribution. Brain Dev. 1999;21:68–70. doi: 10.1016/s0387-7604(98)00067-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anaya-Pava E.J., Saenz-Bocanegra C.H., Flores-Trejo A., Castro-Santana N.A. Diffuse choroidal hemangioma associated with exudative retinal detachment in a Sturge–Weber syndrome case: photodynamic therapy and intravitreous bevacizumab. Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther. 2015 Jan 2 doi: 10.1016/j.pdpdt.2014.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gill N.C., Bhaskar N. Sturge–Weber syndrome: a case report. Contemp Clin Dent. 2010 Jul–Sep;1:183–185. doi: 10.4103/0976-237X.72789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]