Abstract

Background

Injection opioid use plays a significant role in the transmission of HIV infection in many communities and several regions of the world. Access to evidence-based treatments for opioid use disorders is extremely limited.

Methods

HPTN 058 was a randomized controlled trial designed to compare the impact of two medication assisted treatment (MAT) strategies on HIV incidence or death among opioid dependent people who inject drugs (PWID). HIV-negative opiate dependent PWID were recruited from four communities in Thailand and China with historically high prevalence of HIV among PWID. 1251 participants were randomly assigned to either; 1) a one year intervention consisting of two opportunities for a 15 day detoxification with buprenorphine/naloxone (BUP/NX) combined with up to 21 sessions of behavioral drug and risk counseling (Short Term Medication Assisted Treatment: ST-MAT) or, 2) thrice weekly dosing for 48 weeks with BUP/NX and up to 21 counseling sessions (Long Term Medication Assisted Treatment: LT-MAT) followed by dose tapering. All participants were followed for 52 weeks after treatment completion to assess durability of impact.

Results

While the study was stopped early due to lower than expected occurrence of the primary endpoints, sufficient data were available to assess the impact of the interventions on drug use and injection related risk behavior. At weeks 26, 22% of ST-MAT participants had negative urinalyses for opioids compared to 57% in the LT-MAT (p<0.001). Differences disappeared in the year following treatment: at week 78, 35% in ST-MAT and 32% in the LT-MAT had negative urinalyses. Injection related risk behaviors were significantly reduced in both groups following randomization.

Conclusions

Participants receiving BUP/NX three times weekly were more likely to reduce opioid injection while on active treatment. Both treatment strategies were considered safe and associated with reductions in injection related risk behavior. These data support the use of thrice weekly BUP/NX as a way to reduce exposure to HIV risk. Continued access to BUP/NX may be required to sustain reductions in opioid use.

Introduction

Globally, the number of people who inject drugs (PWID) is relatively small, rarely exceeding 1% of total population in any country. Yet, in many communities and several regions, particularly Eastern Europe, Central and Southeast Asia, injection drug use remains a primary driver in the AIDS epidemic.1–5 Outside of sub-Saharan Africa, injection drug use accounts for about one third of all new HIV infections and approximately three million PWID are estimated to be infected with HIV.1,5 PWID are estimated to have twenty-two times the prevalence of HIV infection relative to the general population.6 Since most of these infections are related to the injection of heroin or other opioids, alone or in combination with stimulants or benzodiazepines, effective treatments for opioid dependence have important potential for preventing new HIV infections. Although there have been no randomized controlled trials, over 20 years of observational data on the impact of methadone maintenance treatment (MMT) provide “proof of concept” on the ability of medication assisted treatment (MAT) to reduce opioid use, injection related risk behaviors, and HIV infections.7–16 Yet, despite evidence of the efficacy of methadone treatment as an HIV prevention strategy, access remains extremely limited.3,13,17 Only a small proportion of PWID are currently receiving MAT and most drug users at risk of HIV infection have no access to any form of evidence based treatments for opioid use.5,18

The use of buprenorphine/naloxone (BUP/NX) has expanded rapidly since its approval as a treatment for opioid addiction in the US in 2002. Buprenorphine is a partial opioid agonist with strong affinity to the mu opioid receptors of the central nervous system resulting in an active half-life of up to 60 hours, making dosing intervals of up to three days possible.19,20 While buprenorphine alone was first introduced for opioid dependence treatment in Europe in 1996, naloxone was included in the tablet formulation as a deterrent to diversion and injection.21 When absorbed sublingually, buprenorphine maintains adequate bioavailability while naloxone poorly absorbed and rapidly metabolized. However, if a BUP/NX tablet is dissolved for use by injection, naloxone will remain active and precipitate withdrawal. Overdose from BUP/NX alone is uncommon and withdrawal symptoms following dose reduction are less severe in intensity and duration than pure agonist medications.22–24 Similar to other opioids, side effects include nausea, vomiting, constipation, sedation and temporary elevations in liver transaminases.

Given the critical need to expand MAT options for HIV prevention among opioid injectors, HPTN 058 was designed to compare two novel, one year, community-based opioid treatment strategies using BUP/NX and counseling to reduce incident HIV infections and mortality among opioid dependent injectors.

Methods

HPTN 058, a 1:1 randomized open label trial, compared two twelve month opioid treatment strategies combining medication and drug counseling in opioid dependent PWID in China and Thailand. Those assigned to the short-term medication assisted treatment arm (ST-MAT) received a three day induction to BUP/NX followed by up to 15 days of dose reduction detoxification. ST-MAT participants also received weekly drug counseling for the first three months of treatment and then offered monthly for the remaining nine months of the intervention.25,26 Recognizing that opioid dependence is a chronic disease with a high likelihood of relapse, at week 26, participants in the ST-MAT arm were offered a second opportunity for detoxification. The LT-MAT arm received BUP/NX induction and dosage stabilization followed by directly observed BUP/NX administration in the clinic three times per week for 46 weeks. At week 47 BUP/NX dose tapering began with final dosing completed by the end of week 52. LT-MAT participants received twelve months of drug counseling on the same schedule as the ST-MAT arm. Both study arms were followed for an additional 52 weeks after treatment completion to evaluate long term impact. The primary endpoint of the study was incident HIV infection or death at week 104, one year after the completion of the intervention. The protocol was designed to measure impact during the intervention year and to assess durability of effect following treatment completion. Interim monitoring rules established prior to the initiation of the study included planned analyses by the independent DSMB after 25%, 50% and 75% of the participants had completed the 104 week assessment. The protocol was reviewed and approved by ethics committees and IRBs at each local site and affiliated institutions.

Study population

Study participants were active opioid injectors recruited from the community at four sites: Chiang Mai, Thailand (n= 202); Nanning (n=161) and Heng County (n=411) in Guangxi, China and Urumqi (n=477), in Xinjiang, China. Sites were selected based on prior evidence of HIV incidence among PWID ranging from 2% to 9% per year.27,28 All study sites had access to methadone treatment, harm reduction services, and HIV treatment. Targeted outreach and recruitment activities were guided by local epidemiologic information and knowledge of the drug using community.

Individuals were eligible if they were at least 18 years old, HIV-seronegative, met criteria for opioid dependence (DSM-IV)29, had a positive urine drug test for opioids, and reported injecting 12 or more times in the prior 28 days. Exclusion criteria included enrollment in MMT, known allergy to BUP/NX, current alcohol or benzodiazepine dependence, pregnancy or breastfeeding, unwillingness to use contraception if female, alanine aminotransferase (ALT) > 3 times upper limit of normal (ULN), hemoglobin < 8 g/dL (if male) or 7 g/dL (if female), bilirubin > 2.5 times ULN, or platelet count < 50,000/mm3.

HPTN 058 represented the first use of BUP/NX in both Thailand and China. Consequently, recruitment of participants included activities and materials devoted to community and participant education. Each site had an active community advisory board (CAB) that included representatives from local advocacy groups, family members, public health, and criminal justice agencies. Prior to project implementation, CABs and community representatives were invited to participate in formal meetings designed to solicit feedback on the purpose of the study, its procedures, the interventions, and the strategies used to protect the safety and confidentiality of study participants. The design included a safety phase and review at each site after the first 50 participants completed one month of treatment. No unexpected safety concerns were identified at any site and enrollment proceeded uninterrupted.30

Medication management

Participants in both study arms began with a three day, outpatient induction period. In accordance with established clinical guidelines, participants were instructed not to use opioids for 24 hours prior to induction which must be initiated during withdrawal. Withdrawal symptoms were assessed using the Clinical Opioid Withdrawal Scale (COWS).31,32 Those with a score of 8 or greater were judged ready for induction, and received a 4 mg dose of sublingual BUP/NX. At one hour post-dose, if the COWS score was 2 or greater a second 4 mg dose was given. Days two and three followed similar procedures with provision for up to 16 mg and 32 mg respectively. Following induction, participants assigned to ST-MAT completed detoxification with an average dose tapering of 2 mgs per day for up to 15 days. Participants assigned to LT-MAT, after establishing the maintenance dose that prevented the emergence of withdrawal symptoms, continued receiving BUP/NX for 48 weeks, attending the clinic three times each week for directly observed dosing. At week 48, tapering of BUP/NX began, with dose reduction of 1–2 mgs per day with all medication administration completed prior to week 52. Dosing visits were carefully monitored and re-induction was required if more than three consecutive visits were missed. Women who became pregnant during the BUP/NX treatment phase were tapered from the medication and referred to MMT but continued in the counseling intervention and were followed through delivery and the completion of the study. At the week 26 assessment, participants in the ST-MAT arm who had relapsed to opioid use were offered a second induction and detoxification.

Counseling intervention

All study participants received behavioral drug and risk counseling (BDRC).25,26 BDRC is rooted in cognitive behavioral theory and focused on helping participants understand their addiction as a manageable medical condition. Counseling was delivered in individual sessions of 30–45 minutes, guided by a manual and designed to help participants develop and implement meaningful strategies for controlling drug use and avoiding injection and sexual risk. Counselors helped participants establish short term behavioral goals that promoted completion of BUP/NX administration visits, risk reduction, avoidance of “triggers” for craving and use, and initiation of rewarding behaviors incompatible with continued drug use. Counselors developed behavioral contracts to guide goal directed behavior between counseling sessions.

Assessments

All participants completed interviewer administered assessments of injection and non-injection drug use, sexual and drug related risk behaviors, community treatment utilization, HIV testing and plasma storage every 26 weeks throughout the study. At baseline and weeks 12, 26, 40 and 52 specimens were collected to assess liver function (ALT and total bilirubin). Testing for Hepatitis B and C was performed at screening and week 26, additional testing for Hepatitis C was performed at subsequent semi-annual follow up visits if previously negative. Urine drug screens and pregnancy tests were assessed monthly and semi-annually during the 12 month intervention period. Participants were followed for a minimum of 104 weeks, and a maximum of 156 weeks based upon their time of enrollment.

Laboratory methods

HIV testing was completed using two locally available rapid HIV test kits that had undergone full validation and were subject to routine proficiency testing according to HPTN protocol. Baseline HIV status and all new HIV infections were verified by the HPTN Network Laboratory using stored plasma and Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved HIV methodologies. A commercial point of care test with a sensitivity of 300ng/mL was used for detection of urine opioids and other drugs (Integrated E-Z Split Key Cup, ACON Laboratories, San Diego, CA).

Statistical analysis

The study had 90% power to detect a 50% reduction in cumulative HIV infection and death at 104 weeks, assuming an HIV infection risk such that 7.25% of the ST-MAT arm would be infected or have died by 104 weeks.

The study was reviewed at least annually by an independent Data Safety and Monitoring Board (DSMB) appointed by the sponsor. At the first scheduled interim analyses, occurring October 4, 2011, when 25% of the participants had completed 104 weeks on study, the DSMB halted the study due to futility as a result of lower than anticipated HIV incidence rates. The present analysis includes data from visits up through October 4, 2011.

Cumulative incidence rates and confidence intervals were calculated based on Poisson distribution with time to infection or death. Cox proportional hazards model was used to compute hazards ratios. Monthly urine screens and injection and related risk behaviors were compared between arms using logistic regression at each visit, adjusted for site.

Results

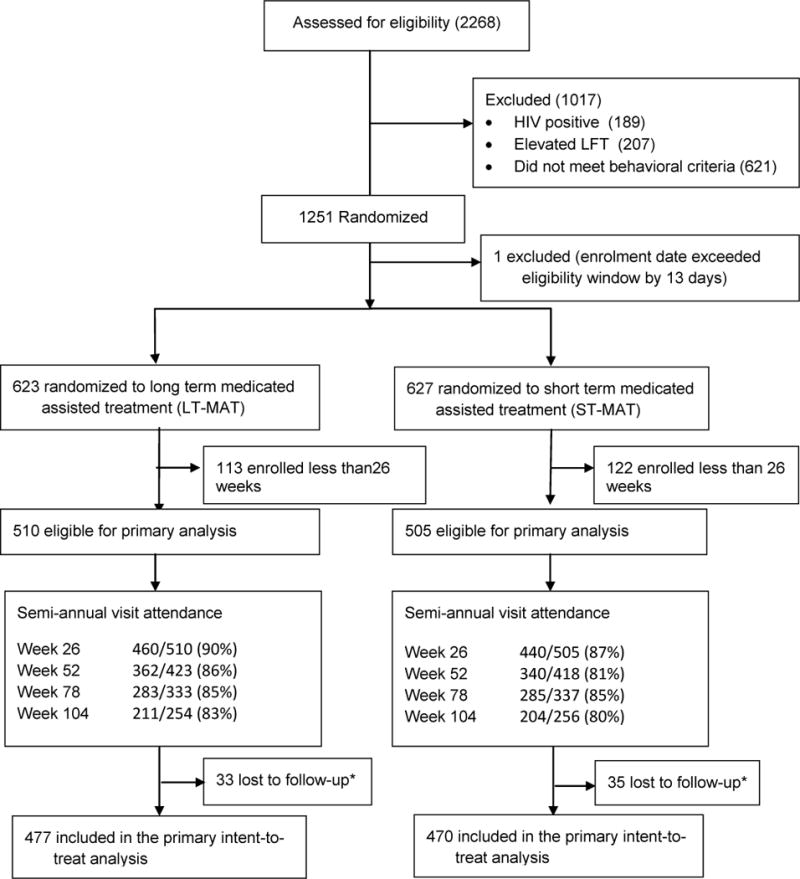

A total of 2268 PWID were screened for eligibility and 1251 were enrolled and randomized between May 2007 and October 2011, 627 on the ST-MAT and 623 on the LT-MAT (Figure 1). At the time the study was halted, 470 ST-MAT participants and 477 in the LT-MAT completed at least one follow-up HIV test and are included in the primary intent to treat (ITT) analysis.

Figure 1. Enrollment and follow-up of study participants.

*participants enrolled for at least 26 weeks with no follow-up assessment of primary endpoint at the time of study closure

As shown in Table 1, participants were predominantly (92%) male with a median age of 33 years. Over 40% were from ethnic minorities and a slight majority were married and living with a spouse or partner. Participants had been injecting for a median of 7 years with a median age at first injection of 25 years. During the month prior to enrollment, 90% reported injecting heroin, 11% reported injecting opium. The median number of injections in the month prior to enrollment was 84 (IQR: 60–90), or about 3 times per day. As required for enrollment, 100% of the participants tested positive for opioids. Methadone (3%), amphetamine (2%) and benzodiazepines (19%) were detected by urine drug screen.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics by arm

| N (%) or median (IQR) | ||

|---|---|---|

| LT-MAT (N = 623) |

ST-MAT (N = 627) |

|

| Demographic characteristics | ||

| Age | 33 (27,39) | 34 (28,39) |

| Male | 574 (92%) | 577 (92%) |

| Ethnic minority1 | 262 (42%) | 260 (41%) |

| Married/Living with Partner | 321 (51%) | 327 (52%) |

| Days employed (prior 30 days) | 15 (0,28) | 16 (0,27) |

| Injection drug use behaviors | ||

| Used needle/syringe after someone in the prior 6 months | 136 (22%) | 121 (19%) |

| Age at first injection | 24 (21, 30) | 25 (20, 31) |

| Years of injection | 7 (3, 12) | 7 (3, 12) |

| Self-reported drugs injected (prior 30 days) | ||

| Heroin | 556 (90%) | 556 (89%) |

| Opium | 66 (11%) | 69 (11%) |

| Amphetamine | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Methadone | 3 (1%) | 0 (0%) |

| Benzodiazepine | 5 (1%) | 10 (2%) |

| Median number of injections (prior 30 days) | 84 (60, 90) | 84 (60, 90) |

| Urine drug screen | ||

| Opioid | 623 (100%) | 627 (100%) |

| Amphetamine | 8 (1%) | 12 (2%) |

| Methadone | 25 (4%) | 18 (3%) |

| Benzodiazepine | 111 (18%) | 124 (20%) |

Ethnic minority are participants who did not identify as Han in China or Thai in Thailand

Intervention exposure

The 3 day induction was initiated by all participants (with one exception) and completed by 89% (88% in the ST-MAT and 91% in the LT-MAT arm) (Table 2). In the ST-MAT arm, 80% of participants completed detoxification. At week 26, 153 of 440 (35%) ST-MAT participants initiated a second detoxification; 85% of these completed this detoxification. LT-MAT participants received observed BUP/NX doses for a median (IQR) of 170 days (IQR, 63, 308).

Table 2.

Delivery of the medication assisted treatment for opioid dependence

| Initiated BUP/NX induction | Completed induction | Completed detoxification | Weekly counseling1 (≥75% sessions weeks 1–12) | Monthly counseling1 (≥75% sessions months 4–12) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial induction/detoxification and counseling | |||||

| ST-MAT | 626/627 (100%) | 554/627 (88%) | 502/627 (80%) | 361/545 (66%) | 215/366 (59%) |

| LT-MAT | 623/623 (100%) | 564/623 (91%) | N/A | 453/541 (84%) | 271/385 (70%) |

| Significance | p<.001 | p<.001 | |||

| ST-MAT: BUP/NX dosing during follow-up | |||||

| 26 week induction (optional) | 153/440 (35%) | 137/153 (90%) | 130/153 (85%) | ||

| LT-MAT: BUP/NX dosing during follow-up | |||||

| Weeks 1–4 | Weeks 13–16 | Weeks 25–28 | Weeks 33–36 | Weeks 45–48 | |

| Received ≥75% of doses2 | 519/612 (85%) | 331/552 (60%) | 275/499 (55%) | 245/474 (52%) | 187/432 (43%) |

| Received any BUP/NX dose3 | 590/612 (96%) | 416/552 (75%) | 345/499 (69%) | 294/474 (62%) | 239/432 (55%) |

| Retained in BUP/NX treatment4 | 597/612 (98%) | 449/552 (81%) | 370/499 (74%) | 317/474 (67%) | 239/432 (55%) |

ST-MATMAT = Short term medication assisted arm, LT-MAT = Long term medication assisted arm,

At the time the study was halted, 1087 had completed the 12 weekly and 751 the 9 monthly counseling sessions

Received at least 75% of thrice weekly dosing throughout the period

Received any BUP/NX dose in the period

Received BUP/NX dose at any point during or after the period

Among the LT-MAT participants, 74% were retained in treatment through weeks 25–28, (i.e. completed BUP/NX medication visits during or after the period) with 55% receiving at least 75% of expected doses in this time window. By the final month of intervention (weeks 45–48), 55% remained in treatment, with 43% receiving at least 75% of expected doses.

Among those assigned to ST-MAT, 66% completed at least 9 of 12 weekly counseling sessions, compared to 84% in the LT-MAT arm (p < 0.001). Similarly, 59% of those in the ST-MAT arm completed 6 of 9 monthly counseling sessions compared to 70% of the LT-MAT (p < 0.001)

HIV infection and Death

Through week 104, 5 incident HIV infections and 9 deaths were identified among those in the ST-MAT arm and 2 incident HIV infections and 8 deaths among LT-MAT participants. With 642 person years (PY) in the ST-MAT arm and 658 in the LT-MAT arm, the composite rates of HIV infection or death were 1.9 (95% CI: 1.0–3.3) and 1.5 (95% CI: 0.7–2.8) per 100 PY, for a hazard ratio of LT-MAT vs. ST-MAT of 0.69 (CI: 0.31–1.56, p = 0.38).

Drug use outcomes

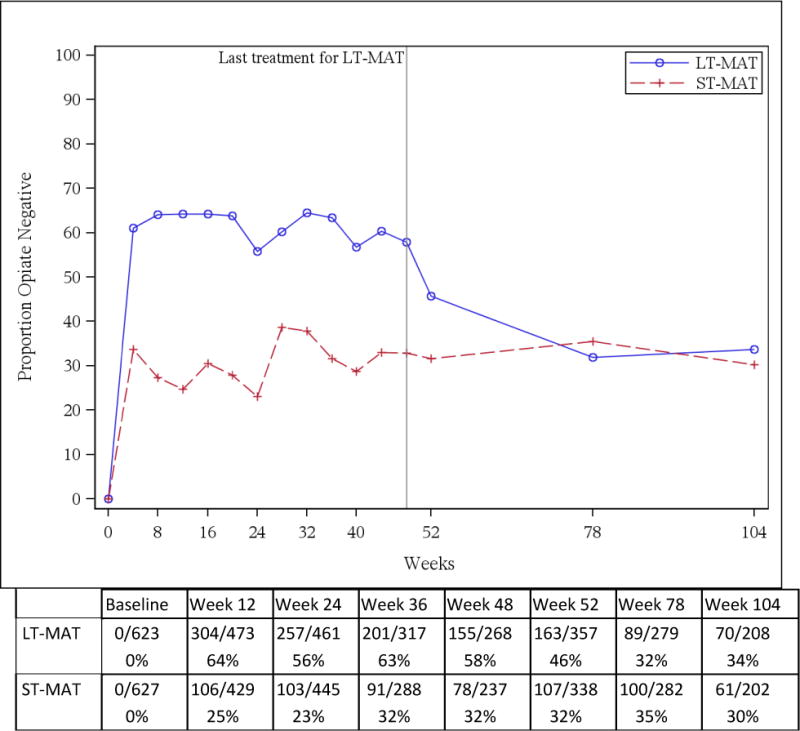

Monthly and semi-annual urine toxicology tests are shown in Figure 2. At week 24, 23% (103/445) in the ST-MAT arm and 56% (257/461) in the LT-MAT tested negative for opioids (p<0.001). At the initiation of dose tapering in week 48, opioid negative toxicology results were found in 33% (78/237) of ST-MAT compared to 58% (155/268) of LT-MAT participants (p<0.001); at completion of tapering (week 52), this remained at 32% (107/338) among ST-MAT participants but decreased to 46% (163/357) in the LT-MAT arm (p< 0.001). By 78 and 104 weeks, ST-MAT and LT-MAT arms had similar rates of opioid-negative tests: at week 78, 35% (100/283) in the ST-MAT and 32% (89/279) in the LT-MAT arm (p = 0.38); at week 104, 30% and 34% in the ST-MAT and LT-MAT arms respectively (p = 0.43).

Figure 2.

Opiate negative urinalyses by study arm during monthly screening and semi-annual follow-up

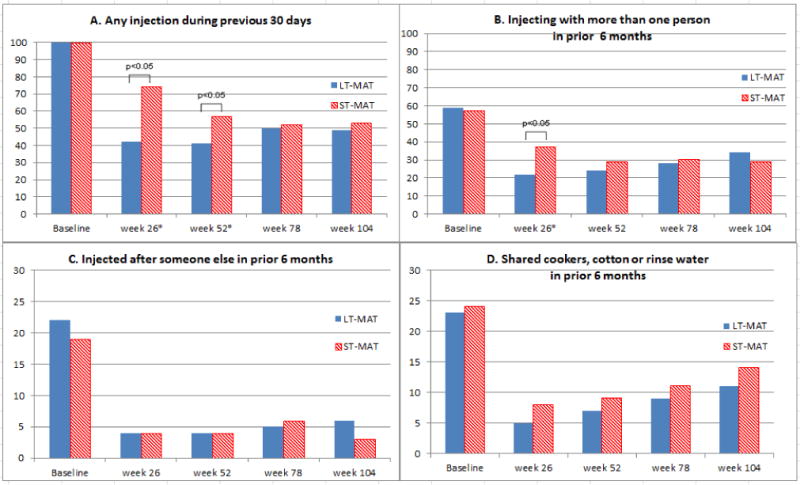

As shown in Figure 3A, self-reported drug use was consistent with urinalyses results; at week 26, 26% of participants in the ST-MAT arm and 58% in the LT-MAT arm reported no injection in the prior 30 days (p ≤ 0.001). At the end of the treatment phase of the study (week 52), 43% of the ST-MAT and 59% of the LT-MAT participants reported no injection during the prior month (p ≤ 0.001). No significant differences between arms were found during the second year: at 78 weeks 48% of ST-MAT and 50% of LT-MAT participants reported no injection (p = 0.7) and at 104 weeks, 53% of ST-MAT and 49% of LT-MAT reported no injection use (p = 0.4).

Figure 3.

Self-reported injection and related risk behaviors

Risk behavior outcomes

Self-reported injection related risk behaviors showed significant reduction in both arms following baseline that was sustained through the treatment phase and the subsequent year of follow-up. Figures 3B, 3C, and 3D show this pattern for injecting with more than one person, use of the same syringe/needle after another PWID, and sharing cookers, cottons, and rinse water. Significantly fewer injections were reported by LT-MAT participants at week 26 and 52. Also, fewer LT-MAT participants reported injecting with more than one person compared to ST-MAT.

Discussion

Due to the small number of new HIV infections observed in the study, we were unable to evaluate whether one year of BUP/NX and counseling was more effective in preventing HIV infection and death than short term BUP/NX and counseling. Despite this, those with one year of access to BUP/NX in the LT-MAT arm had a significantly higher, sustained reduction in opioid use and injection compared to those in the ST-MAT arm, as measured by both urinalyses and self-report, indicating a reduced risk of exposure to HIV. The differential rates of opioid use between arms disappeared by week 78, although 30% or more participants remained opioid free.

The study was designed to assess the durability of the LT-MAT intervention following one year of treatment and it is apparent that relapse to opioid use commenced as soon as the tapering began. Thrice-weekly access to BUP/NX achieved significant reductions in opioid use and injection during treatment. Since these reductions were not sustained after cessation of BUP/NX and counseling, our data clearly demonstrate the necessity of continued access to medication beyond one year to sustain reductions in opioid use for many PWID.

The reduction in opioid use among participants in the LT-MAT arm during the treatment phase has important implications for HIV prevention. Research conducted over the past 20 years clearly demonstrates that reduced opioid use and injection related risk behaviors among opioid users in MAT are associated with lower risk of HIV acquisition.16 In addition, access to and retention in MAT by HIV positive individuals has been associated with increased retention in antiretroviral treatment and viral suppression, which itself has been associated with a reduced risk of HIV transmission.33–36 Past research among PWID has demonstrated that continued drug use inhibits these objectives. Cessation of injection through effective treatments (similar to that reported here) has been shown to increase access and improve retention and adherence to antiretroviral treatment.35,37–42 Importantly, these positive impacts occur among injectors who cease injection and not merely stop sharing syringes or enter treatment.38

Injection related risk behaviors were reduced among participants in both arms. Significant reductions in self -reports of injection, frequency of injection, needle sharing (reuse of a syringe after another injector), injection with others and sharing of cookers, cotton, and rinse water were observed between baseline and the assessment at six months in both arms. These behavioral changes were sustained through the intervention year and extended throughout the year following cessation of BUP/NX and counseling. The self-reported reductions in drug use and risk behavior among participants in both groups are consistent with the low rate of HIV incidence observed during the study.

Reductions in injection related risk behaviors must be considered in light of the counseling intervention that was available to participants in both arms. The approach and content were the same and attendance had potential to be clinically meaningful. Those assigned to the LT-MAT arm completed significantly more counseling sessions, suggesting that the regular contact required for medication administration also facilitated counseling attendance. Since participants in both arms received the same counseling, it is not possible to directly measure its impact on drug use and risk behaviors in this study. However, both arms displayed similar patterns of risk reduction. The data reported here support the perception that behavior change can occur among drug users who continue to use drugs.

Study sites were chosen based on earlier studies in these same communities that found HIV incidence rates as high as 8% per year.27,28 During the intervening time, HIV testing was expanded, access to antiretroviral treatment was scaled up and methadone treatment was introduced in each of the three communities in China. It is likely that these public health programs contributed to the low HIV incidence observed in HPTN 058.

The findings reported here should be considered in light of several limitations. First, participants in this study were recruited from the community and volunteered to receive treatment for their addiction. Consequently, data from this trial may not generalize to all opioid dependent injectors. Despite efforts to include women, 92% of the participants were men and we cannot be certain that the treatment outcomes apply to female opioid dependent injectors. Data on frequency of injection, injections with others, and sharing of syringes and other injection equipment can only be measured by self-report. However, it is important to note that we observed a high correlation between self-reported opioid use and urine toxicology results. Additionally, the decline in opioid use and injection in both arms of the study may reflect a regression to the mean bias since all participants had to have a positive opioid test in order to be enrolled. Finally, the study was discontinued prematurely due to lower than expected event rates in both arms of the study and we were unable to address the primary outcome of the trial.

Medication Assisted Treatment (MAT) approaches are based upon a body of evidence showing that drug dependence is most effectively treated when viewed as a chronic medical condition with both biological and behavioral components. As in the treatment of other chronic medical conditions disease management is more likely to be successful when appropriate medications are used in combination with behavioral interventions. In the United States, data on the efficacy of BUP/NX treatment coupled with its safety profile led to FDA approval for administration through office-based practice in which physicians with brief training can provide prescriptions for pharmacy distribution and self-administration. For some opioid dependent individuals however, the clinic based, directly observed medication administration used in HPTN 058 may be a more effective delivery strategy and lead to increased adherence and participation in counseling.

The participation we achieved in both medication and counseling is comparable or superior to that seen in other drug treatment modalities and provides evidence of the feasibility and acceptability of this strategy.33 Thrice weekly directly observed dosing, combined with counseling has a much lower burden on both patients and staff than daily MMT and has not previously been assessed in a large scale community-based trial. This intervention was safe and effective for reducing both opioid dependence and injection related risk. Access to MATs for opioid dependent individuals who are at risk for HIV and other blood borne infections is extremely limited, particularly in areas where HIV transmission is most commonly linked to injection drug use.5,17 It is hoped that the success of the BUP/NX strategy tested in HPTN 058 will lead to expanded coverage of effective MAT as HIV prevention.

Acknowledgments

The research reported here was funded by the HIV Prevention Trials Network through a grant from the NIH.

The project described was supported by Award Numbers UM1 AI068619, UM1 AI069482, and UM1 AI068613 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. Additional support was provided by the National Institute on Drug Abuse. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, the National Institute on Drug Abuse or the National Institutes of Health. Reckitt Benckiser Pharmaceuticals donated all medication used in this trial.

Footnotes

Earlier versions of some of the data reported here were presented at the 19th International AIDS Conference, Washington, DC, USA, July 2012. D. Metzger, D. Donnell, B. Jackson et al., “One year of counseling supported buprenorphine-naloxone treatment for HIV prevention in opioid dependent injecting drug users showed efficacy in reducing opioid use and injection frequency: HPTN058 in Thailand and China. Abstract THPE191,”

Contributor Information

David S. Metzger, University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine, Department of Psychiatry and the Treatment Research Institute.

Deborah Donnell, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Vaccine and Infectious Disease Division.

David D. Celentano, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Department of Epidemiology.

J. Brooks Jackson, Johns Hopkins School of Medicine and University of Minnesota, Department of Pathology.

Yiming Shao, State Key Laboratory for Infectious Disease Prevention and Control, National Center for AIDS/STD Control and Prevention, Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Collaborative Innovation Center for Diagnosis and Treatment of Infectious Diseases.

Apinun Aramrattana, Chiang Mai University, Faculty of Medicine, Department of Family Medicine.

Liu Wei, Guangxi Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Guangxi Center for HIV/AIDS Prevention and Control.

Liping Fu, Xinjiang Autonomous Region Center for Disease Control and Prevention.

Jun Ma, Xinjiang Autonomous Region Center for Disease Control and Prevention.

Gregory M. Lucas, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Department of Medicine.

Marek Chawarski, Yale School of Medicine Department of Psychiatry.

Yuhua Ruan, State Key Laboratory for Infectious Disease Prevention and Control, National Center for AIDS/STD Control and Prevention, Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Collaborative Innovation Center for Diagnosis and Treatment of Infectious Diseases.

Paul Richardson, Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, Department of Pathology.

Katherine Shin, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, Division of AIDS, Pharmaceutical Affairs Branch.

Ray Y. Chen, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, Division of Intramural Research.

Jeremy Sugarman, Johns Hopkins University, Berman Institute of Bioethics.

Bonnie J. Dye, FHI 360.

Scott M. Rose, FHI 360.

Geetha Beauchamp, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Vaccine and Infectious Disease Division.

David N. Burns, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, Division of AIDS, Prevention Sciences Branch.

References cited

- 1.Beyrer C, Malinowska-Sempruch K, Kamarulzaman A, Kazatchkine M, Sidibe M, Strathdee SA. HIV in people who use drugs 7 Time to act: a call for comprehensive responses to HIV in people who use drugs. Lancet. 2010 Aug;376(9740):551–563. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60928-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.De Cock KM, Jaffe HW, Curran JW. The evolving epidemiology of HIV/AIDS. Aids. 2012 Jun;26(10):1205–1213. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328354622a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vlahov D, Robertson AM, Strathdee SA. Prevention of HIV Infection among Injection Drug Users in Resource-Limited Settings. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2010 May;50:S114–S121. doi: 10.1086/651482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kilmarx PH. Global epidemiology of HIV. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2009;4(4):240–246. doi: 10.1097/COH.0b013e32832c06db. 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mathers BM, Degenhardt L, Ali H, et al. HIV prevention, treatment, and care services for people who inject drugs: a systematic review of global, regional, and national coverage. Lancet. 2010 Mar 20;375(9719):1014–1028. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60232-2. Epub 2010 Feb 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bergenstrom AM, Abdul-Quader AS. Injection drug use, HIV and the current response in selected low-income and middle-income countries. Aids. 2010 Sep;24:S20–S29. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000390086.14941.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gowing L, Farrell MF, Bornemann R, Sullivan LE, Ali R. Oral substitution treatment of injecting opioid users for prevention of HIV infection. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(8):CD004145. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004145.pub4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Metzger DS, Woody GE, McLellan AT, et al. Human-Immunodeficiency-Virus seroconversion among intravenous-drug users in-of-treatment and out-of-treatment – An 18-month prospective follow-up. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes and Human Retrovirology. 1993;6(9):1049–1056. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gowing LR, Farrell M, Bornemann R, Sullivan LE, Ali RL. Methadone treatment of injecting opioid users for prevention of HIV infection. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2006;21(2):193–195. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.00287.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Qian HZ, Hao C, Ruan YH, et al. Impact of methadone on drug use and risky sex in China. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2008;34(4):391–397. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2007.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thiede H, Hagan H, Murrill CS. Methadone treatment and HIV and hepatitis B and C risk reduction among injectors in the Seattle area. Journal of Urban Health-Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine. 2000 Sep;77(3):331–345. doi: 10.1007/BF02386744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Metzger DS, Woody GE, O’Brien CP. Drug Treatment as HIV Prevention: A Research Update. Jaids-Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2010 Dec;55:S32–S36. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181f9c10b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sullivan LE, Metzger DS, Fudala PJ, Fiellin DA. Decreasing international HIV transmission: the role of expanding access to opioid agonist therapies for injection drug users. Addiction. 2005;100(2):150–158. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00963.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sorensen JL, Copeland AL. Drug abuse treatment as an HIV prevention strategy: a review. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2000 Apr;59(1):17–31. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(99)00104-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Farrell M, Gowing L, Marsden J, Ling W, Ali R. Effectiveness of drug dependence treatment in HIV prevention. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2005;16:S67–S75. [Google Scholar]

- 16.MacArthur GJ, Minozzi S, Martin N, et al. Opiate substitution treatment and HIV transmission in people who inject drugs: systematic review and meta-analysis. British Medical Journal. 2012 Oct;:345. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e5945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mathers BM, Degenhardt L, Adam P, et al. Estimating The Level of HIV Prevention Coverage, Knowledge and Protective Behavior Among Injecting Drug Users: What Does The 2008 UNGASS Reporting Round Tell Us? Jaids-Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2009;52:S132–S142. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181baf0c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Degenhardt L, Mathers B, Vickerman P, Rhodes T, Latkin C, Hickman M. HIV in people who use drugs 2 Prevention of HIV infection for people who inject drugs: why individual, structural, and combination approaches are needed. Lancet. 2010 Jul;376(9737):285–301. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60742-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Amass L, Kamien JB, Mikulich SK. Thrice-weekly supervised dosing with the combination buprenorphine-naloxone tablet is preferred to daily supervised dosing by opioid-dependent humans. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2001 Jan 1;61(2):173–181. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(00)00141-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnson RE, Jones HE, Fischer G. Use of buprenorphine in pregnancy: patient management and effects on the neonate. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2003 May 21;70(2 Suppl):S87–101. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(03)00062-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Emmanuelli J, Desenclos JC. Harm reduction interventions, behaviours and associated health outcomes in France, 1996–2003. Addiction. 2005 Nov;100(11):1690–1700. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01271.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johnson RE, Strain EC, Amass L. Buprenorphine: how to use it right. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2003 May 21;70(2 Suppl):S59–77. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(03)00060-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bridge TP, Fudala PJ, Herbert S, Leiderman DB. Safety and health policy considerations related to the use of buprenorphine/naloxone as an office-based treatment for opiate dependence. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2003 May;70(2 Suppl):S79–85. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(03)00061-9. 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fudala PJ, Woody GW. Recent advances in the treatment of opiate addiction. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2004 Oct;6(5):339–346. doi: 10.1007/s11920-004-0020-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chawarski MC, Mazlan M, Schottenfeld RS. Behavioral drug and HIV risk reduction counseling (BDRC) with abstinence-contingent take-home buprenorphine: a pilot randomized clinical trial. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008 Apr 1;94(1–3):281–284. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chawarski MC, Zhou W, Schottenfeld RS. Behavioral drug and HIV risk reduction counseling (BDRC) in MMT programs in Wuhan, China: A pilot randomized clinical trial. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2011 Jun;115(3):237–239. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.09.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wei L, Chen J, Rodolph M, et al. HIV incidence, retention, and changes of high-risk behaviors among rural injection drug users in Guangxi, China. Subst Abus. 2006 Dec;27(4):53–61. doi: 10.1300/j465v27n04_07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang Y, Shan H, Trizzino J, et al. HIV incidence, retention rate, and baseline predictors of HIV incidence and retention in a prospective cohort study of injection drug users in Xinjiang, China. International journal of infectious diseases : IJID : official publication of the International Society for Infectious Diseases. 2007 Jul;11(4):318–323. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2006.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Woody G, Schuckit M, Weinrieb R, Yu E. A review of the substance use disorders section of the DSM-IV. The Psychiatric clinics of North America. 1993 Mar;16(1):21–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lucas GM, Beauchamp G, Aramrattana A, et al. Short-term safety of buprenorphine/naloxone in HIV-seronegative opioid-dependent Chinese and Thai drug injectors enrolled in HIV Prevention Trials Network 058. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2012 Mar;23(2):162–165. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2011.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wesson DR, Ling W. The clinical opiate withdrawal scale (COWS) Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 2003 Apr-Jun;35(2):253–259. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2003.10400007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tompkins DA, Bigelow GE, Harrison JA, Johnson RE, Fudala PJ, Strain EC. Concurrent validation of the Clinical Opiate Withdrawal Scale (COWS) and single-item indices against the Clinical Institute Narcotic Assessment (CINA) opioid withdrawal instrument. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2009 Nov 1;105(1–2):154–159. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fiellin DA, Weiss L, Botsko M, et al. Drug treatment outcomes among HIV-infected opioid-dependent patients receiving buprenorphine/naloxone. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2011 Mar 1;56(Suppl 1):S33–38. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182097537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Uhlmann S, Milloy MJ, Kerr T, et al. Methadone maintenance therapy promotes initiation of antiretroviral therapy among injection drug users. Addiction. 2010 May;105(5):907–913. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.02905.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wood E, Hogg RS, Kerr T, Palepu A, Zhang R, Montaner JSG. Impact of accessing methadone on the time to initiating HIV treatment among antiretroviral-naive HIV-infected injection drug users. Aids. 2005 May;19(8):837–839. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000168982.20456.eb. 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, et al. Prevention of HIV-1 Infection with Early Antiretroviral Therapy. New England Journal of Medicine. 2011 Aug;365(6):493–505. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Roux P, Carrieri MP, Villes V, et al. The impact of methadone or buprenorphine treatment and ongoing injection on highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) adherence: evidence from the MANIF2000 cohort study. Addiction. 2008 Nov;103(11):1828–1836. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02323.x. Epub 2008 Sep 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Roux P, Carrieri MP, Cohen J, et al. Retention in Opioid Substitution Treatment: A Major Predictor of Long-Term Virological Success for HIV-Infected Injection Drug Users Receiving Antiretroviral Treatment. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2009;49(9):1433–1440. doi: 10.1086/630209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wood E, Milloy MJ, Montaner JSG. HIV treatment as prevention among injection drug users. Current Opinion in Hiv and Aids. 2012 Mar;7(2):151–156. doi: 10.1097/COH.0b013e32834f9927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wood E, Kerr T, Tyndal MW, Montaner JSG. A review of barriers and facilitators of HIV treatment among injection drug users. Aids. 2008;22(11):1247–1256. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282fbd1ed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Volkow ND, Baler RD, Normand JL. The Unrealized Potential of Addiction Science in Curbing the HIV Epidemic. Current Hiv Research. 2011 Sep;9(6):393–395. doi: 10.2174/157016211798038605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Spire B, Lucas GM, Carrieri MP. Adherence to HIV treatment among IDUs and the role of opioid substitution treatment (OST) International Journal of Drug Policy. 2007;18(4):262–270. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2006.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]