Abstract

Light is a source of energy and also a regulator of plant physiological adaptations. We show here that light/dark conditions affect alternative splicing of a subset of Arabidopsis genes preferentially encoding proteins involved in RNA processing. The effect requires functional chloroplasts and is also observed in roots when the communication with the photosynthetic tissues is not interrupted, suggesting that a signaling molecule travels through the plant. Using photosynthetic electron transfer inhibitors with different mechanisms of action we deduce that the reduced pool of plastoquinones initiates a chloroplast retrograde signaling that regulates nuclear alternative splicing and is necessary for proper plant responses to varying light conditions.

Light regulates approximately 20% of the transcriptome in Arabidopsis thaliana and rice (1, 2). Alternative splicing has been shown to modulate gene expression during plant development and in response to environmental cues (3). We observed that the alternative splicing of At-RS31 (Figure 1A), encoding a Ser-Arg-rich splicing factor (4), changed in different light regimes, which led us to investigate how light regulates alternative splicing in plants.

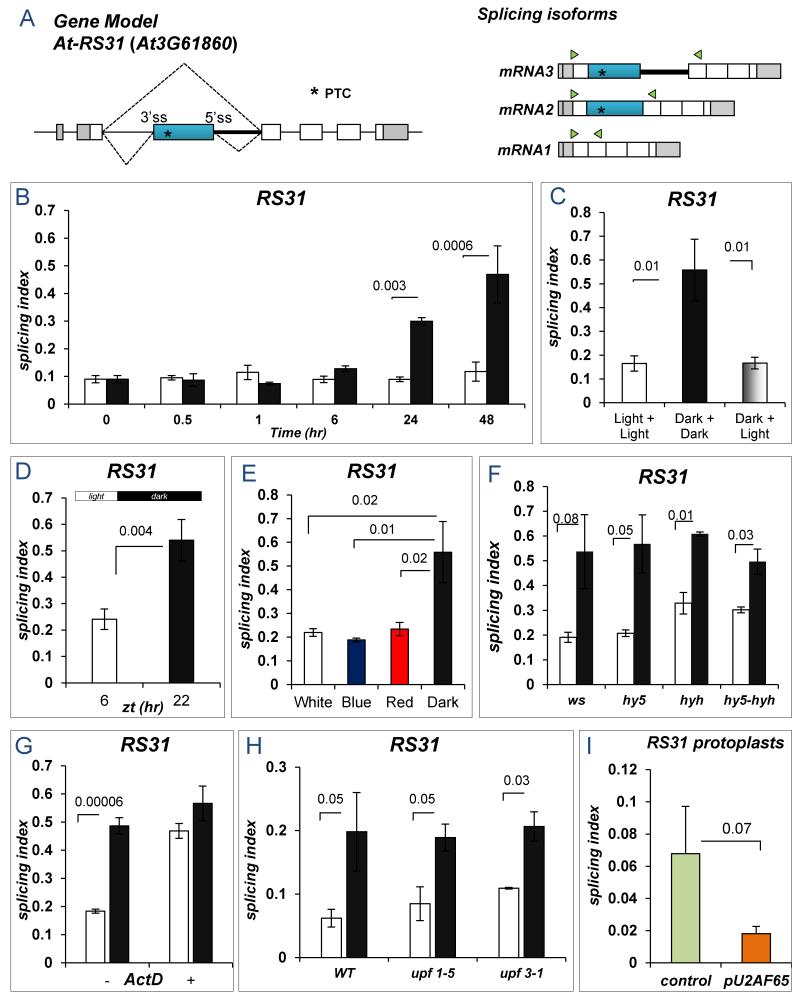

Figure 1. Effects of light/dark transitions on At-RS31 alternative splicing.

A) At-RS31 splicing event. *, PTC: premature termination codon. Triangles: primers for splicing evaluation (see also Figure S10a). B) Arabidopsis thaliana seedlings were incubated in light/dark for different times (Suppl. Text). C) After 48 hr of darkness, transferring the seedlings to light causes a rapid change in the SI of At-RS31 to “light values” (Suppl. Text). Light+Light, 48 hr + 3 hr light; Dark+Dark, 48 hr + 3 hr dark; Dark+Light, 48 hr dark + 3 hr light. D) Seedlings were grown for 2 weeks under short day conditions (~100 μmol/m2s). Samples were collected 2 hr before lights off (6 hr, zt) and 2 hr before lights on (22 hr, zt). E) Plants were grown in constant light, transferred to dark for 48 hr and then treated in light/dark for 6 hr with LEDs to provide specific wavelengths (Suppl. Text). F) hyh and hy5 mutants for integrators of photoreceptor-signaling pathways show the same At-RS31 alternative splicing regulation by light as WT plants (WS -Wassilewskija ecotype). G) Actinomycin D (ActD) causes the loss of the light/dark transition effect. ActD (+) was added 2 hr before light/dark treatments. DMSO, control (−). H) SI change induced by the light/dark transition is preserved in the NMD impaired mutants upf1-5 and upf3-1. I) Effect of U2AF65 over-expression in A. thaliana protoplasts. In all experiments: white bars, light; black bars, darkness. Data represent means ± standard deviation (n≥3); significant p-values (Student’s t-test) are shown.

Seedlings were grown for a week in constant white light to minimize interference from the circadian clock and then transferred to light or dark conditions for different times (Suppl. Text). We observed a 2- and 4-fold increase in the splicing index (SI), defined as the abundance of the longest splicing isoform relative to the levels of all possible isoforms, of At-RS31 [mRNA3/(mRNA1+mRNA2+mRNA3)] after 24 and 48 hr in the dark, respectively (Figure 1B). This effect was rapidly reversed when seedlings were placed back in light, with total recovery of the original SI in about 3 hr (Figure 1C), indicating that the kinetics of the splicing response is slower from light to dark than from dark to light.

The light effect is gene-specific (Figure S1) and is also observed in diurnal cycles under short day conditions (Figures 1D and S2). Furthermore, three circadian clock mutants behaved like the wild type (WT) in the response of At-RS31 alternative splicing to light/dark (Figure S3). Changes in At-RS31 splicing are proportional to light intensity both under constant light or in short day grown seedlings (Figure S4).

Both red (660 nm) and blue (470 nm) lights produced similar results as white light (Figure 1E). Moreover, At-RS31 splicing is not affected in phytochrome and cryptochrome signaling mutants (5, 6) behave as WT seedlings, ruling out photosensory pathways in this light regulation (Figures 1F, S5 and S6).

Light-triggered changes in At-RS31 mRNA patterns are not due to differential mRNA degradation. First, the light effect is not observed in the presence of the transcription inhibitor actinomycin D (Figure 1G). Second, the effects are still observed in upf mutants, defective in the nonsense-mediated mRNA decay (NMD) pathway (7) (Figures 1H and S7). Third, overexpression of the constitutive splicing factor U2AF65 (8) in Arabidopsis protoplasts mimics the effects of light on At-RS31 alternative splicing (Figures 1I).

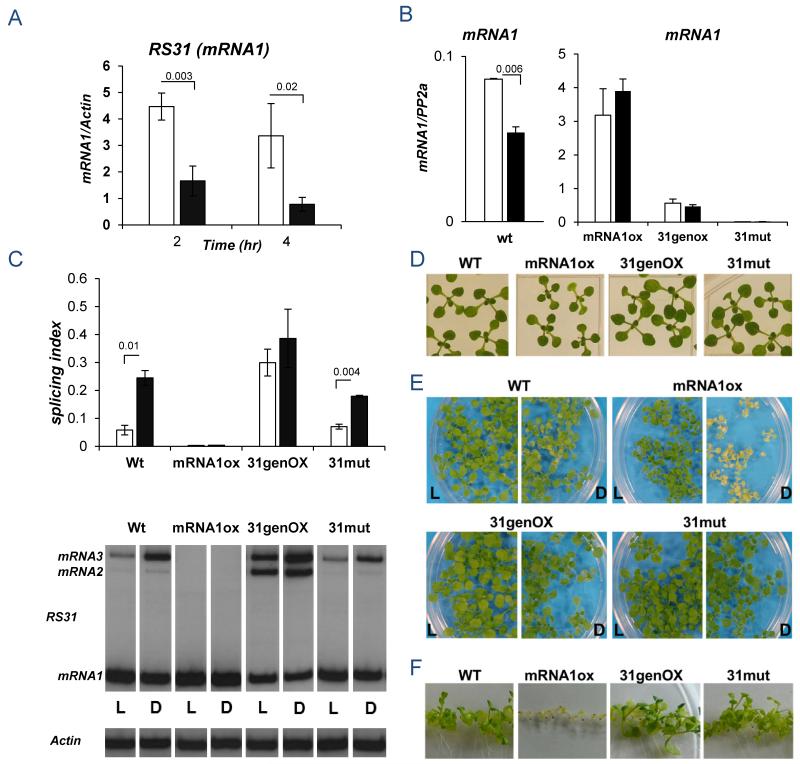

mRNA1 is the only isoform encoding a full-length At-RS31 protein (9). mRNA3 and mRNA2 are almost fully retained in the nucleus (Figure S8). mRNA1 levels decrease considerably in dark without significant changes in the total amount of At-RS31 transcripts (Figures 2A and S9) which suggests that alternative splicing is instrumental in the control of mRNA1 cellular levels and, consequently, At-RS31 protein abundance. To assess how interference with At-RS31 alternative splicing regulation could affect Arabidopsis phenotype we obtained transgenic plants overexpressing either a cDNA (mRNA1ox) or a genomic version (31genOX) of At-RS31, and a knock-out (31mut) line (Figure S10). At-RS31 total mRNA is more abundant in the mRNA1ox and 31genOX lines compared to the WT (Figure S10). While the mRNA1ox line expresses almost exclusively the mRNA1 isoform and at higher levels than the other lines, the 31genOX line is mostly enriched in mRNA3 and mRNA2 isoforms while mRNA1 levels are not much higher than those in WT seedlings (Figures 2B, 2C and S10). Under photoperiodic conditions (16/8 hr light/dark) no major phenotypes are observed for these lines (Figures 2D, S11 and “L” in 2E). However, when plants are either exposed to long darkness (3 days, Figure 2E), or grown under constant low light intensity (50 μmol/m2sec, Figure 2F), the mRNA1ox line shows a dramatic phenotype, characterized by small and yellowish seedlings concomitantly with faster degradation of chlorophylls a and b (Figure S12). This suggests that downregulation of mRNA1 in the dark through alternative splicing is important for proper growth of the plant in response to changing environmental light conditions.

Figure 2. At-RS31 alternative splicing regulation is important for proper adjustment to light changes.

A) qPCR analysis of At-RS31 mRNA1 levels relative to Actin. The graph shows the relative expression of mRNA1 in two different time points of light/dark treatment (2 and 4 hr). B) qRT-PCR analysis of At-RS31 mRNA1 isoform expression in the different genotypes and treatments. C) Top, At-RS31 SI in the different genotypes in response to light/dark (Suppl. Text); Bottom, representative gel images for the alternative splicing pattern of At-RS31 in the different genotypes in response to light/dark transitions. Actin, as control. L, light; D, dark. D) All lines were grown on MS agar plates with 1 % sucrose for 1 week in light/dark cyles (16/8 hr), 120 μmol/m2sec white light. Similar size sections of plates are shown. E) Seedlings of the different genotypes were grown under a 16/8 hr light/dark regime for 2 weeks and then transferred to dark for 3 days (D) or kept in photoperiod as controls (L). F) Seedlings for each genotype were grown on MS plates in constant light conditions (~50 μmol/m2sec). Similar size sections of plates are shown. Bar color code and statistics as in Figure 1.

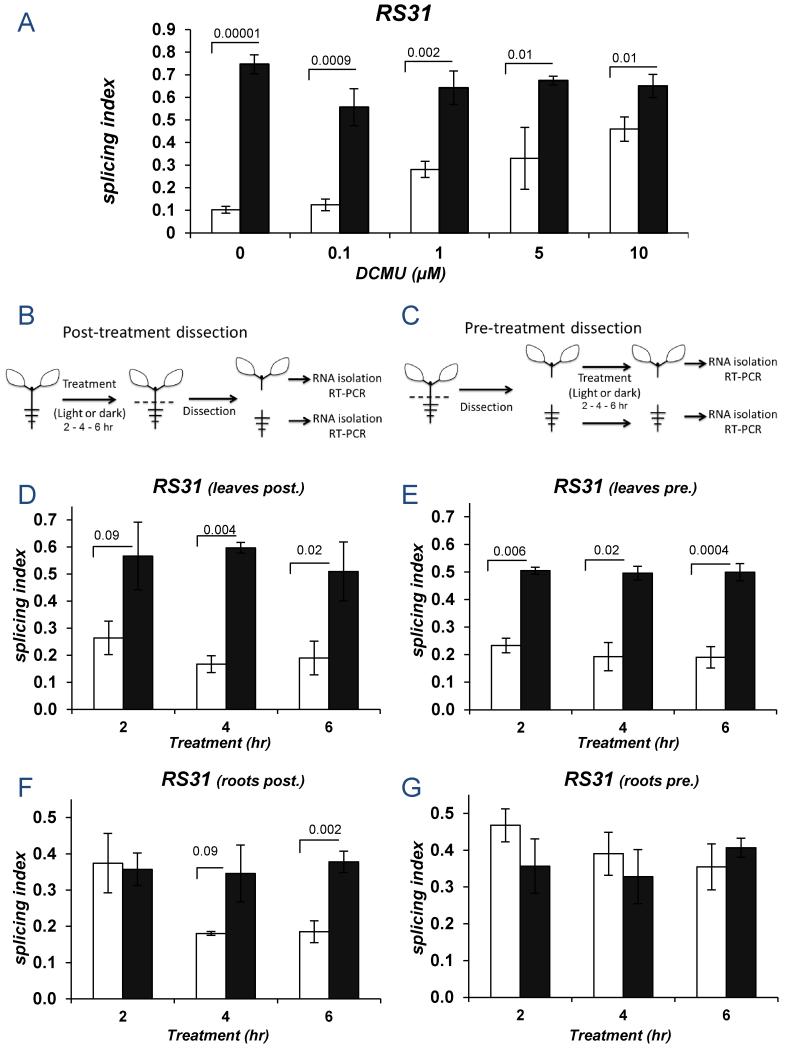

As sensory photoreceptors do not participate, we investigated whether retrograde signals from the chloroplast were involved (1). Increasing concentrations of DCMU [3-(3,4-dichlophenyl)1,1-dimethylurea] (10), a drug that blocks the electron transfer from photosystem II (PSII) to the plastoquinone (PQ) pool, inhibited the effect of light on At-RS31 alternative splicing (Figure 3A), confirming chloroplast involvement. Roots have no chloroplasts so the light effect should only be observed in the green tissue in dissected seedlings (Figures 3B). However, the effect was observed both in dissected leaves and roots, with roots showing a time delay in the response (Figures 3D and F). When shoots were separated from roots before the light/dark treatment (Figures 3C), dissected shoots retained the response (Figure 3E); but light had no effect on At-RS31 splicing in isolated roots (Figure 3G). Similar results were obtained by covering the different parts of the seedlings (Figure S13). No chlorophyll was detected in the roots of pre- or post-dissected plants (Figure S14), strengthening the hypothesis that a mobile signal generated in the leaves triggers root alternative splicing responses to light.

Figure 3. The light signal is generated in the photosynthetic tissue and travels through the plant.

A) Seedlings were grown in constant light, transferred to darkness for 48 hr and then treated with DCMU during a 6 hr light/dark further incubation. B-G) Light regulation of At-RS31 alternative splicing in green tissues and roots after a 2, 4 or 6 hr light/dark exposure of whole seedlings (B, D, F) or in the isolated parts exposed separately to light or dark (C, E, G). B, C) Schemes for post- and pre-exposure dissections (see Suppl. Text). D, F) At-RS31 alternative splicing assessment in green tissue (D) or in the roots (F) of light/dark treatments performed using intact seedlings (dissection performed after light/dark treatment). E, G) At-RS31 alternative splicing assessment in response to light/dark treatments using pre-dissected (E) green tissue or (G) roots (dissection performed before light/dark treatment). Bar color code and statistics as in Figure 1.

About 39% of the 93 alternative splicing events (Table S1) tested using a high-resolution RT-PCR panel (11) changed significantly in response to light (Tables S2-S4, Figure S15). The effects of light were not due to sugar starvation during darkness (Figure S15) indicating that the chloroplast role in this light signaling pathway is not primarily associated to the energy state of the cells (Figure S16a). In addition, we ruled out the participation of sugar-sensing pathways (12, 13) reported to control nuclear gene expression (Figures S16b and c).

Analysis of light-responsive splicing events revealed an enrichment in the RNA-binding and processing category (Figure S17 and Table S3). The SR protein gene At-SR30 (20) and At-U2AF65 (21) showed the biggest changes (Figure S18 and Table S2) and DCMU treatment also confirmed a role for chloroplast involvement in their responses (Figure S19).

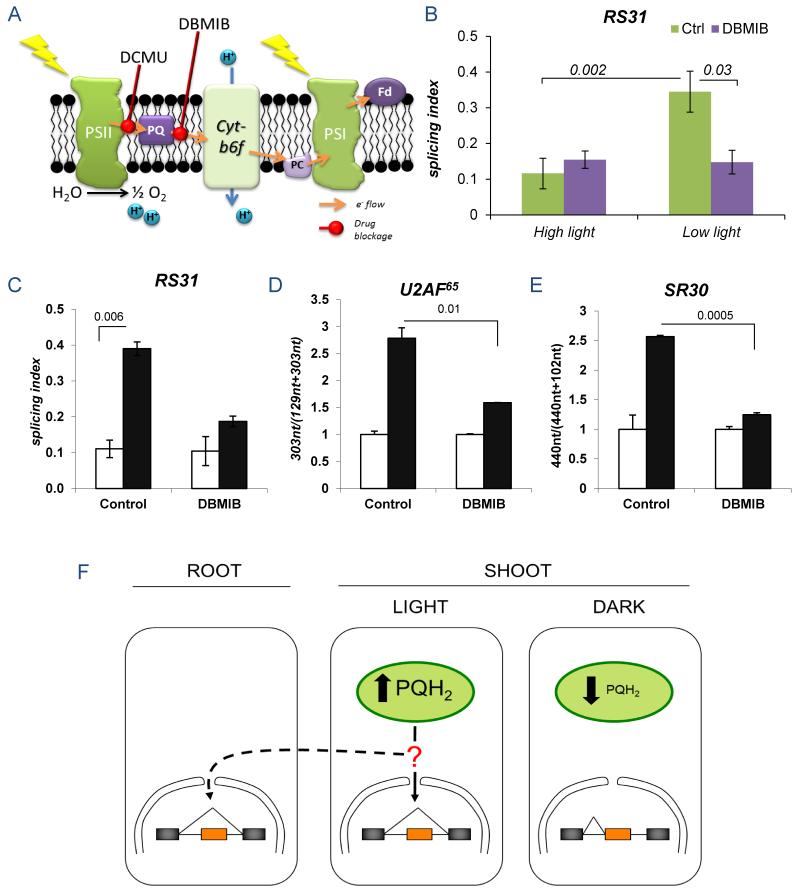

Experiments in Figures S20 and S21 revealed that plastid gene expression, the tetrapyrrole pathway and reactive oxygen species (14) are not involved in At-RS31 alternative splicing regulation. Since methyl viologen takes electrons from PSI (15) with no effect on At-RS31 alternative splicing (Figure S21a) we inferred that the signal must be generated between PSII and PSI. To prove this we used DBMIB (2,5-dibromo-3-methyl-6-isopropyl-p-benzoquinone). Both DCMU and DBMIB inhibit the overall electron transport chain but while DCMU increases the oxidized PQ pool by blocking the electron transfer from the PSII to PQ (10), DBMIB keeps the PQ pool reduced by preventing the electron transfer to cytochrome b6/f (15) (Figure 4A). Addition of DBMIB potentiates the decrease in At-RS31 SI when seedlings are exposed to low light in comparison to the lack of effect under high light (Figure 4B). It was shown that when externally added in the dark, DBMIB can act as a reduced quinone analog (16, 17). Consistently, DBMIB decreases At-RS31 SI in the dark, mimicking the effects of light (Figure 4C). Similar results were obtained for At-U2AF65 and At-SR30 (Figures 4D and E).

Figure 4. The plastoquinone redox state mediates alternative splicing regulation by light.

A) Diagram showing the action of DBMIB and DCMU in the photosynthetic electron transport chain. B) Effects of the addition of 30 μM DBMIB to seedlings under medium (80 μmol/m2 sec) and low (15 μmol/m2 sec) light on At-RS31 alternative splicing. C-E) Addition of 30 μM DBMIB reduces the effects of light/dark transitions on At-RS31 (C), At-U2AF65 (D) and At-SR30 (E) alternative splicing patterns. F) Model for the light regulation of alternative splicing. Light-induced reduction of plastoquinone to plastoquinol (PQH2) generates a signal that modulates alternative splicing in the nucleus. This signal, or a derived one, travels to the roots and provokes similar effects. Bar color code and statistics as in Figure 1.

Our results reveal a retrograde pathway linking the photosynthetic redox state to the regulation of nuclear alternative splicing, mediated by the PQ pool, together with a signaling molecule, of yet unknown nature, that is able to travel through the plant to affect alternative splicing (Figure 4F).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank J. Casal, J. Estévez, N. Iusem, J. Palermo, G. Cabrera, G. Siless, N. Carrillo, F. Rolland, J. Chory, J-S. Jeon, R. Hausler, J. Sheen, A. Köhler, A. Trebst, and S. Smeekens for materials and advice.

This work was supported by the Agencia Nacional de Promoción de Ciencia y Tecnología of Argentina, the University of Buenos Aires, the King Abdulaziz University, the European Network on Alternative Splicing, the Austrian Science Fund FWF (P26333 to M.K.; DK W1207, SFBF43-P10, ERA-NET I254 to A.B.), the UK Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council and the Scottish Government Rural and Environment Science and Analytical Services division. M.G.H. is fellow and A.R.K. is career investigator from the Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas of Argentina. E.P. is an EMBO postdoctoral fellow. A.R.K. is a senior international research scholar of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (for detailed acknowledgments see Supplementary Text).

Footnotes

Additional Author Notes: see “Suppl. Text” file.

Materials and Methods: see “Suppl. Text” file.

Figures S1-S22: see “Suppl. Figures” file.

Tables S1-S4: see “Suppl. Tables” file and “Suppl. Text” file for details.

References and Notes

- 1.Ruckle ME, Burgoon LD, Lawrence LA, Sinkler CA, Larkin RM. Plant Physiol. 2012;159:366–390. doi: 10.1104/pp.112.193599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gyula P, Schafer E, Nagy F. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2003;6:446–452. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5266(03)00082-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Syed NH, Kalyna M, Marquez Y, Barta A, Brown JW. Trends Plant Sci. 2012;17:616–623. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2012.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lopato S, Waigmann E, Barta A. Plant Cell. 1996;8:2255–2264. doi: 10.1105/tpc.8.12.2255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Casal JJ, Yanovsky MJ. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 2005;49:501–511. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.051973jc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sellaro R, Hoecker U, Yanovsky M, Chory J, Casal JJ. Curr. Biol. 2009;19:1216–1220. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.05.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim SH, et al. Plant Cell. 2009;21:2045–2057. doi: 10.1105/tpc.109.067736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Domon C, Lorkovic ZJ, Valcarcel J, Filipowicz W. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:34603–34610. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.51.34603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kalyna M, Lopato S, Voronin V, Barta A. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:4395–4405. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khandelwal A, Elvitigala T, Ghosh B, Quatrano RS. Plant Physiol. 2008;148:2050–2058. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.128488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Simpson CG, et al. Plant J. 2008;53:1035–1048. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03392.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dijkwel PP, Huijser C, Weisbeek PJ, Chua NH, Smeekens SC. Plant Cell. 1997;9:583–595. doi: 10.1105/tpc.9.4.583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hanson J, Smeekens S. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2009;12:562–567. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2009.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koussevitzky S, et al. Science. 2007;316:715–719. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schansker G, Toth SZ, Strasser RJ. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2005;1706:250–261. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2004.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Finazzi G, Zito F, Barbagallo RP, Wollman FA. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:9770–9774. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010092200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Elich TD, Edelman M, Mattoo AK. EMBO J. 1993;12:4857–4862. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb06175.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.