Abstract

We provide an overview of recent progress on the study of astrocyte intracellular Ca2+ signaling. We consider the methods that have been used to monitor astrocyte Ca2+ signals, the various types of Ca2+ signals that have been discovered (waves, microdomains, and intrinsic fluctuations), the approaches used to broadly trigger and block Ca2+ signals, and, where possible, the proposed and demonstrated physiological roles for astrocyte Ca2+ signals within neuronal microcircuits. Although important progress has been made, we suggest that further detailed work is needed to explore the biophysics and molecular mechanisms of Ca2+ signaling within entire astrocytes, including their fine distal extensions, such as processes that interact spatially with neurons and blood vessels. Improved methods are also needed to mimic and block molecularly defined types of Ca2+ signals within genetically specified populations of astrocytes. Moreover, it will be essential to study astrocyte Ca2+ activity in vivo to distinguish between pharmacological and physiological activity, and to study Ca2+ activity in situ to rigorously explore mechanisms. Once methods to reliably measure, mimic, and block specific astrocyte Ca2+ signals with high temporal and spatial precision are available, researchers will be able to carefully explore the correlative and causative roles that Ca2+ signals may play in the functions of astrocytes, blood vessels, neurons, and microcircuits in the healthy and diseased brain.

Astrocytes exhibit various types of calcium signals (e.g., waves, microdomains, and intrinsic fluctuations). Advanced methods to probe these signals will clarify their roles in sensing and controlling neuronal and synaptic activity.

Calcium ions are a ubiquitous inorganic signaling species that play myriad fundamental roles in nearly all aspects of biology in diverse species from most phyla (Clapham 2007). From the fertilization of an egg to the death of a cell, from muscle contraction to neurite extension, and from the release of neurotransmitters/hormones to synaptic plasticity, temporally and spatially restricted Ca2+ fluxes are essential. Not surprisingly, clarifying the biophysical and physiological mechanisms underlying the regulation of Ca2+ has been central to many advances in biology. Recalling the way in which electrophysiology allowed neuroscientists to explore neuronal activity (Scanziani and Häusser 2009), the development of tools for monitoring Ca2+ concentrations and fluxes has enabled researchers to explore Ca2+ signaling in nonexcitable cells including glia (Tsien 1988, 1989). One of the first demonstrations of dynamic Ca2+ fluctuations and regulation in astroglia came from the laboratory of Stephen Smith (Cornell-Bell et al. 1990). Using hippocampal explant cultures and organic Ca2+ indicator dyes, these and other investigators beautifully demonstrated that astroglia exhibited “spontaneous” calcium elevations that propagated in complicated patterns throughout cells as well as developed into Ca2+ waves that propagated over long distances and involved many individual cells (Cornell-Bell et al. 1990; Charles et al. 1991; Dani et al. 1992). Further, these investigators found that the activation of neurotransmitter receptors increased Ca2+ signaling within astroglial cells. These main observations are preserved in astrocytes in situ and in vivo in awake mice. Consequently, with respect to astrocyte signaling, focus over the past two decades has been on an analysis of the mechanisms and roles of astrocyte Ca2+ fluxes in situ and, more recently, in vivo. In many ways, Stephen Smith provided the basis and rationale for these studies in the early 1990s with two thought-provoking essays that are apt even today (Smith 1992, 1994).

APPROACHES TO MONITOR Ca2+ SIGNALS

Organic Ca2+ Indicator Dyes

Our understanding and ability to formulate hypotheses on the roles of astrocyte Ca2+ relies heavily on our ability to faithfully measure the underlying Ca2+ signals in physiologically relevant astrocyte compartments (Fig. 1). The methods used to image astrocyte Ca2+ signals have recently been reviewed (Tong et al. 2012; Li et al. 2013). It is important to remember that, by definition, all available methods have the potential to buffer Ca2+ because they all rely on Ca2+ binding. Hence, Ca2+ indicators should be used at concentrations that do not exceed the buffering capacity of the cells being studied (Tsien 1988; Neher 2000). In most cases, this means concentrations in the micromolar range when measuring bulk cytosolic Ca2+ signals with organic indicator dyes, such as Fluo-4 and Fura, but this will depend on the specifics of the experiment at hand and the dyes being used. Detailed information on the biophysical aspects of astrocyte Ca2+ buffering does not exist and precise guidelines are not possible at present.

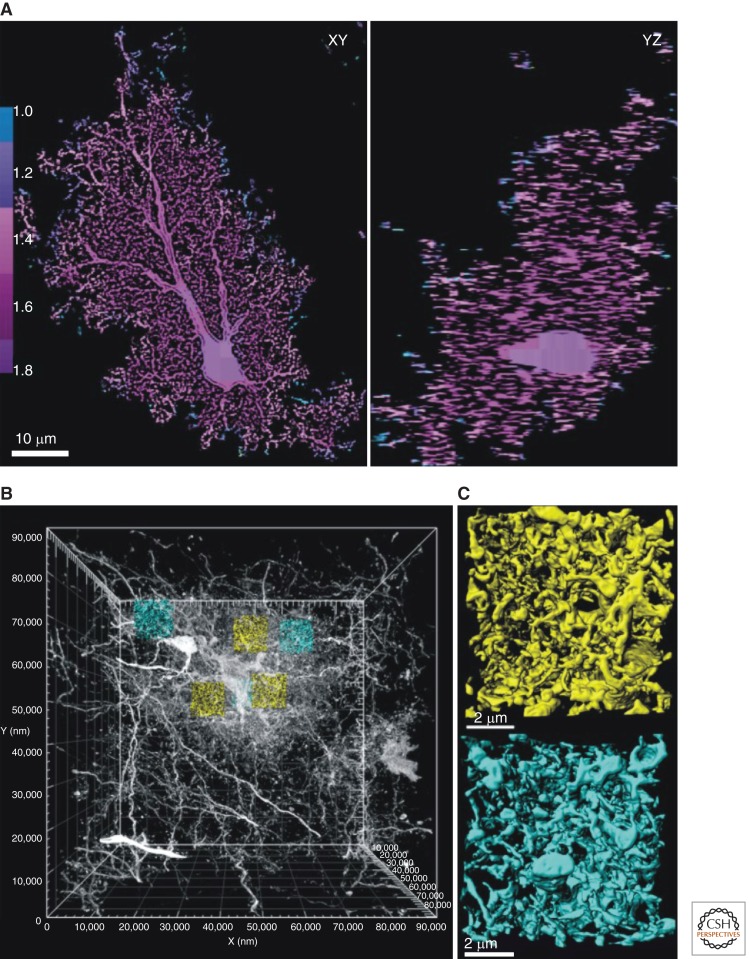

Figure 1.

Electron and light microscopy analysis of astrocyte processes. (A) Orthogonal slices through a confocal volume of a dye-filled astrocyte. Box counting fractal analysis was performed to determine the local DF across the astrocyte territory. The vast majority of the territory has a DF of ∼1.7, extending from the soma to the periphery, as shown by the colored scale bar. This implies that astrocytes are approximately equally complex throughout their territories. (B) Electron microscopic volume of an entire Golgi-impregnated astrocyte. Three perisomatic (yellow) and three peripheral (cyan; one of them is behind a yellow one in the view shown) subvolumes (∼680 µm3 each) have been extracted to determine surface area and volume of astrocyte branchlets. (C) Close-up views of astrocyte processes in perisomatic and peripheral subvolumes demonstrating dense network of fine branchlets in both regions. These analyses reveal that astrocytes have thousands of branches that are the primary sites for interactions with neurons. However, as discussed in the text, Ca2+ signals have not been studied in the fine structures. (From Shigetomi et al. 2013a; reproduced, with permission, from the authors as well as by the Creative Commons license for reuse in the public domain.)

Starting from the initial studies of Smith and colleagues, organic Ca2+ indicator dyes have been vital in the exploration of astrocyte physiology and the dynamics of Ca2+ signals. These indicators are available in a range of Ca2+ affinities, binding/unbinding kinetics and spectral properties. Organic Ca2+ indicator dyes have been extensively used and the data obtained with them has significantly advanced our understanding of astrocyte–neuronal interactions.

One of the most common methods to study astrocytes is bulk loading of membrane-permeable organic Ca2+ indicator dyes. The method is extensively used because of its ease and relative specificity for astrocytes, which can be confirmed using another astrocyte-specific vital dye, sulforhodamine 101 (Nimmerjahn et al. 2004). Although this method remains powerful for studying astrocyte Ca2+ signals, it does have limitations and its utility needs to be considered depending on the question at hand. First, it has been known for over two decades that bulk loading is problematic in adult tissue, although it works reproducibly in brain slices from young rodents (Yuste and Katz 1991; Haustein et al. 2014). Second, bulk loading fails to report on finer astrocyte structures, such as branches and branchlets, leaving ∼90% of the cell unsampled (Reeves et al. 2011). This is an important limitation because astrocytes interact with neurons via their fine distal extensions (Fig. 1). Therefore, it is likely that the most important compartments of astrocyte–neuron interactions cannot be effectively studied using bulk loading methods. The disconnect between where astrocyte Ca2+ signals have been measured (i.e., largely in the soma) and where they underlie physiological responses (likely in finer processes) has contributed to an incomplete picture of the role of astrocyte Ca2+ in physiology, as recently proposed (Reeves et al. 2011; Tong et al. 2012; Shigetomi et al. 2013a). Broadly, this conceptual problem may be analogous to trying to accurately measure events from dendritic spines and nerve terminals using somatic electrophysiological recordings from neurons. In both of these cases, direct exploration of dendritic signaling and nerve terminals necessitated the development of methods to record directly from dendrites (Stuart et al. 1993) and presynaptic nerve terminals (Bischofberger et al. 2006).

Patch pipette–mediated loading of membrane-impermeable organic Ca2+ indicator dyes has also been used to measure astrocyte Ca2+ signals based on pioneering work (Nett et al. 2002). This method has a number of advantages, including the fact that an identified astrocyte is loaded with a known concentration of dye, and the loading is often more complete than with bulk loading, permitting evaluation of the major astrocyte processes (Agulhon et al. 2010; Di Castro et al. 2011; Panatier et al. 2011). However, patch-mediated dialysis of astrocytes with Ca2+ indicator dyes introduces several problems that need to be carefully considered depending on the specifics of the experiment at hand. First, patch-mediated dialysis of Ca2+ indicator dyes does not provide information on fine astrocyte processes. Second, to obtain complete loading of astrocytes, quite high amounts of Ca2+ indicator dye are often used (up to 0.5 mm). The use of high concentrations means that the dye will alter Ca2+ signals and Ca2+-dependent processes within astrocytes (Tsien 1988; Neher 2000). Third, the act of patching cells not only introduces the dye into them, but also washes out intracellular components from within. This procedure also has the potential to alter cell properties (Rand et al. 1994). Nonetheless, when used judiciously, patch-mediated dialysis remains an important method to explore astrocyte Ca2+ signals.

Genetically Encoded Ca2+ Indicators (GECIs)

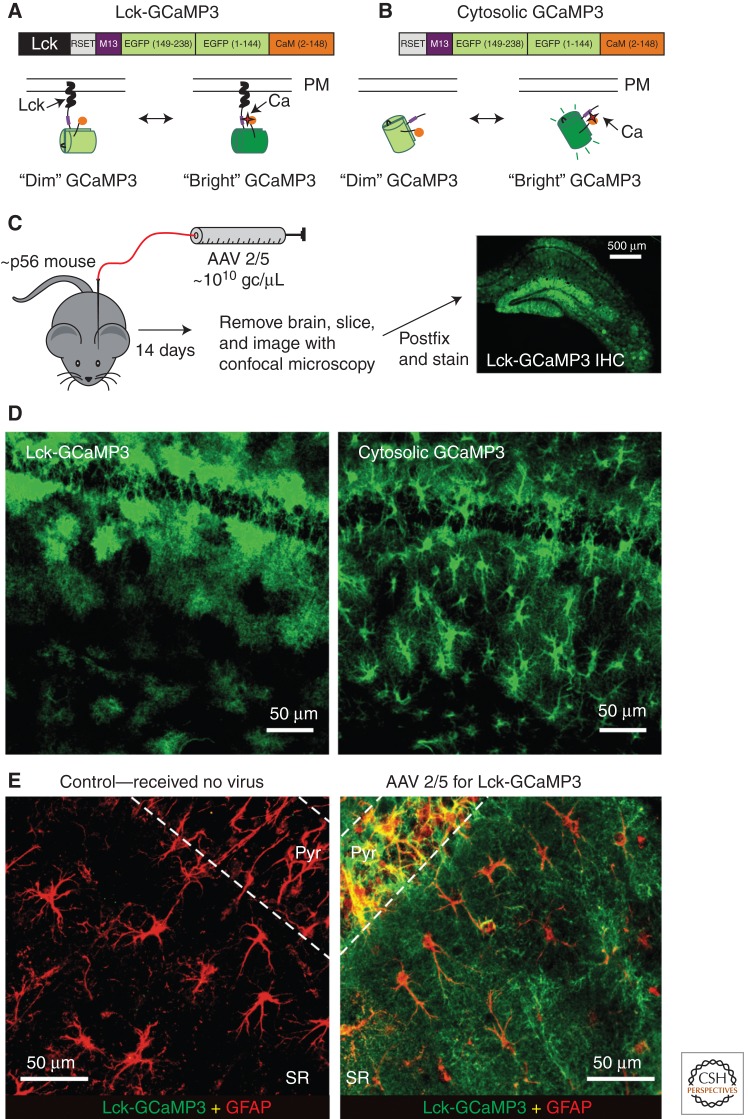

Building on work with fluorescence resonance energy transfer based Ca2+ indicators expressed in astrocytes (Atkin et al. 2009; Russell 2011), our laboratory (Khakh laboratory) recently sought to measure Ca2+ signals in astrocytes using single-wavelength genetically encoded Ca2+ indicators (GECIs) based on circularly permuted green fluorescent protein (Hires et al. 2008; Tian et al. 2009). We focused on using a membrane-targeted GECI and a cytosolic form (Fig. 2). The rational for using a membrane-targeted GECI and a cytosolic one was based on the fact that rapid switching between evanescent and wide-field microscopy revealed that many cytosolic Ca2+ signals failed to elevate Ca2+ near the plasma membrane of astroglia (Shigetomi et al. 2010b). Additionally, some Ca2+ signals happened only in near membrane regions (Shigetomi et al. 2010b). Finally, the sites of interaction between neurons and astrocytes in vivo are likely to be in the extensive small processes that have high surface areas and low internal volumes (Fig. 1), implying that a membrane-targeted GECI may be better than a cytosolic one to image Ca2+ signals within them (Shigetomi et al. 2010b). Based on these considerations, we first generated Lck-GCaMP2, and then improved the GECI iteratively in terms of signal-to-noise, expression level, and kinetics to generate Lck-GCaMP3 and Lck-GCaMP5G (Shigetomi et al. 2010a, 2011; Akerboom et al. 2012). “Lck” refers to a 26-amino-acid peptide that has been shown to be a strong membrane tether (Zlatkine et al. 1997; Benediktsson et al. 2005) and “GCaMP” refers to widely used single wavelength GECIs (Hires et al. 2008; Tian et al. 2009). Lck-GCaMP3 and 5G share many benefits of Lck-GCaMP2, but display better signal-to-noise ratios and expression levels. Most recently, we made Lck-GCaMP6 and tested it (along with cytosolic GCaMP6) in relation to GCaMP3 (Haustein et al. 2014). These are the current GECIs of choice, with GCaMP6 displaying kinetics as fast as an organic Ca2+ indicator dye (Chen et al. 2013). Together, the membrane-targeted and cytosolic GECIs represent useful tools to measure near-membrane and cytosolic Ca2+ signals in adult tissue (Shigetomi et al. 2013a,b). As mentioned earlier, GECIs have the potential to buffer Ca2+, but this has not proved problematic in several studies of neurons and astrocytes, perhaps because they are expressed in low micromolar amounts using the methods that have been used to date, such as adeno-associated viruses and knockin mice (Tian et al. 2009; Zariwala et al. 2012; Chen et al. 2013; Shigetomi et al. 2013a,b). The biggest challenge in using GECIs is the need for specialized methods to deliver the genes to astrocytes, necessitating the need to generate and test viruses (Fig. 2), or transgenic approaches, which can be time consuming and expensive. However, both methods have been used with success and with little evidence of deleterious effects on astrocytes (Zariwala et al. 2012; Shigetomi et al. 2013a). Cre-dependent knockin mice and adeno-associated viruses (AAVs) capable of delivering GECIs to astrocytes are widely available from Jackson Laboratories and the Penn Vector Core (University of Pennsylvania) (Zariwala et al. 2012; Shigetomi et al. 2013b). Very recently, our work with GECIs in situ following in vivo expression with viruses (Fig. 2) has been extended to studies in vivo with Cre-dependent GCaMP3 knockin mice in which the approach worked and revealed robust Ca2+ signals within large parts of astrocyte territories (Paukert et al. 2014).

Figure 2.

Expression of cytosolic GCaMP3 and Lck-GCaMP3 throughout astrocytes. (A,B) Cartoons of differences between cytosolic and membrane-targeted GECIs. (C) Schematic illustrates the protocol for AAV 2/5 microinjections into the hippocampus. The right-hand image shows the expression of Lck-GCaMP3 throughout the hippocampus, and D shows expression within the stratum radiatum region for Lck-GCaMP3 and cyto-GCaMP3. (E) Representative images showing GFAP and GCaMP3 staining for the stratum radiatum region from control mice that received no AAVs and those that received AAV2/5 Lck-GCaMP3. The image is a zoomed-out view. AAV, adeno-associated virus; gc, genome copy; PM, plasma membrane. (From Shigetomi et al. 2013a; reproduced, with permission, from the authors as well as by the Creative Commons license for reuse under the public domain.)

TYPES OF ASTROCYTE CALCIUM SIGNALS

Intrinsic Calcium Fluctuations and Calcium Waves

Astrocytes, like many cell types, show intrinsic Ca2+ fluctuations that occur in the absence of external signals (Nett et al. 2002). Aside from the initiating events, the mechanisms underlying intrinsic Ca2+ fluctuations and intracellular Ca2+ waves have been studied extensively and are reasonably well understood (Berridge et al. 2003). At distinct sites within cells, there are bursts of Ca2+ release from the IP3 receptors/channels (IP3Rs) located in the membrane of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). Events that trigger these localized Ca2+ increases may include (1) a high density of Gq G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) whose intrinsic activity generates a sufficient level of IP3 to activate nearby IP3 receptors, (2) focal points of elevated Ca2+, which acts as a coagonist at IP3Rs, or (3) the Ca2+ “load” of a restricted region within the ER. Intracellular Ca2+ waves result from the diffusion of Ca2+ to neighboring IP3Rs where, in the presence of IP3, Ca2+ can induce Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release (CICR). Intracellular Ca2+ waves follow a specific spatial path within cells that is dependent on the proximity of ER IP3Rs; if the nearest IP3R is too distant, Ca2+ is buffered to basal levels and the intracellular Ca2+ wave terminates. Therefore, it is the spatial distribution of IP3Rs that provides a path for intracellular Ca2+ waves. Increasing concentrations of Gq-GPCR agonists leads to increases in the frequency of Ca2+ fluctuations and distance traveled by intracellular Ca2+ waves without a marked effect on the amplitude of Ca2+ responses (Shao and McCarthy 1993); the mechanism(s) underlying frequency changes has not been resolved. As the concentration of the Gq-GPCR agonist increases, it is possible to obtain a sustained increase in Ca2+ that is caused by the opening of store-operated Ca2+ channels and entrance of extracellular Ca2+; there is little evidence that this occurs in astrocytes under physiological conditions. Intrinsic Ca2+ fluctuations and intracellular Ca2+ waves are observed in astroglia in culture, as well as in astrocytes in acutely isolated brain slices (Fatatis and Russell 1992; Nett et al. 2002). The role(s) of intrinsic Ca2+ fluctuations and associated short-range Ca2+ waves has not been resolved. Given that these events occur independently of neuronal activity (Shao and McCarthy 1993; Nett et al. 2002) and are generally not synchronized with adjacent astrocytes, it is possible that there are inherent processes within astrocyte microdomains that affect local neural activity. That is, different regions of a given astrocyte may differentially affect local signaling events. For example, although not known, it is possible that individual microdomains within an astrocyte are independently regulating the local level of extracellular K+, glutamate, γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA), adenosine, nitric oxide (NO), or prostaglandins, as well as perhaps influencing dendritic spine formation through the release of trophic factors.

Transmembrane Ca2+ Signals and “Spotty” Microdomains

The vast majority of studies in this area have focused on store-mediated Ca2+ signals in astrocytes (see preceding sections), but there is a growing literature on ligand-gated cation channels in astrocytes. For example, activation of P2X and N-methyl-d-aspartic acid (NMDA) receptors leads to Ca2+ elevations in cortical astrocytes (recently reviewed in Pankratov and Lalo 2013). The extent to which these ion channels contribute either to basal Ca2+ levels or to intrinsic Ca2+ fluctuations is incompletely explored, but pharmacological experiments suggest they can be activated during synaptic neurotransmitter release (Palygin et al. 2010). For the remainder of this section, we focus on recent work that shows that astrocyte TRPA1 channels contribute to basal Ca2+ levels and to a fraction of intrinsic fluctuations in the CA1 region of the hippocampus.

Using membrane-targeted GECIs, one of us (Khakh laboratory) discovered a transmembrane Ca2+ flux pathway mediated by TRPA1 channels in astrocytes (Shigetomi et al. 2010b, 2011). These channels mediate spotty Ca2+ microdomains that are independent of those mediated by IP3R-dependent Ca2+ release from ER stores, but nonetheless contribute to basal Ca2+ levels within astrocytes. TRPA1-mediated microdomains have been observed in cell culture and in situ (Shigetomi et al. 2010a, 2011, 2013a,b). The discovery of TRPA1 channels in astrocytes and their contribution to near membrane and basal Ca2+ signals adds to the diversity of Ca2+ signals in astrocytes. Much more work is needed to explore other candidate mechanisms that may also lead to the elevation of Ca2+ levels or contribute to basal Ca2+ levels, including ligand-gated ion channels (Pankratov and Lalo 2013), TRPC channels (Malarkey et al. 2008), and several classes of transporters (Nedergaard et al. 2010). To a large extent, these areas have not been fully explored so far. Work on Drosophila melanogaster may be portentous (Melom and Littleton 2013).

An important aspect of TRPA1-mediated spotty Ca2+ signals within astrocytes was that TRPA1 blockades reduced basal cytosolic Ca2+ levels (Shigetomi et al. 2011). It remains feasible (but unproven) that the spotty Ca2+ signals may themselves regulate astrocyte Ca2+ levels locally within microdomains, but the available data suggest that they contribute to bulk intracellular basal Ca2+ levels. An additional feature of the TRPA1-mediated spotty Ca2+ signals that set them apart from other astrocyte Ca2+ signals is that they seem not to be regulated by, or require, neuronal activity or GPCR activation (Shigetomi et al. 2011), making it unlikely that TRPA1 channels contribute to active neuron-to-astrocyte communication. Based on the available data, two functions have been discovered for astrocyte TRPA1 channels using TRPA1 knockout mice and selective TRPA1 antagonists. The first are the indirect actions on inhibitory GABAergic synaptic transmission onto interneurons located in the stratum radiatum region of the hippocampus (Shigetomi et al. 2011). The mechanism involves TRPA1-mediated contributions to basal Ca2+ levels, which, in turn, regulate astrocyte GABA transporters of the GAT-3 subtype (Shigetomi et al. 2011). The second mechanism also involves TRPA1-mediated basal astrocyte Ca2+ levels, which are permissive for the release of d-serine (Shigetomi et al. 2013a). d-serine is thought to set the tone for NMDA-receptor-dependent long-term synaptic plasticity of excitatory synapses onto CA1 pyramidal neurons in the hippocampus (Shigetomi et al. 2013a). In both of these cases, astrocyte basal Ca2+ signals seem to indirectly contribute to neuronal function (via GABA transport and d-serine levels). We found no evidence to suggest that elevated Ca2+ signals mediated by TRPA1 channels affected either inhibitory synaptic transmission or synaptic plasticity (Shigetomi et al. 2011, 2013b). The potential contribution(s) of basal Ca2+ levels to other aspects of astrocyte physiology remains incompletely explored. In recent studies, we found that TRPA1 channels did not contribute to Ca2+ signals within astrocytes located in the stratum lucidum within the CA3 region of the hippocampus (Haustein et al. 2014). We interpret this to provide the first functional evidence for astrocyte heterogeneity even within subfields of the hippocampus.

Increases in Astrocytic Calcium Mediated by Neurons In Situ and In Vivo

Strong evidence shows that astrocytes in situ and in vivo respond to neuronal activity with increases in Ca2+. This was initially observed in acutely isolated hippocampal slices where electrical stimulation of the Schaffer collateral pathway led to increases in astrocytic Ca2+ via the activation of Gq-coupled GPCRs (Porter and McCarthy 1996). Subsequent studies from a large number of laboratories indicate that neuronal activation in situ leads to increases in astrocytic Ca2+ (Carmignoto and Haydon 2012). Although this was an important observation, the question remained whether physiological stimuli lead to increases in astrocytic Ca2+. Over the past several years, evolving technology has enabled investigators to monitor astrocyte Ca2+ responses to sensory stimulation in vivo using cranial windows and to relate this to neuronal activity in a correlative manner. Findings from these studies show that astrocytes in vivo respond to sensory input with increases in Ca2+ (Wang et al. 2006; Nimmerjahn et al. 2009). Interestingly, the form of astrocyte Ca2+ responses to sensory stimulation varies markedly among brain regions and experimental conditions. For example, most cortical astrocytes respond to whisker stimulation with Ca2+ responses restricted to their processes with little evidence of widespread Ca2+ waves (Wang et al. 2006), but later studies in awake mice with the startle response show widespread wave-like Ca2+ signals among astrocytes (Ding et al. 2013). In contrast, Bergmann glia can show large-scale Ca2+ waves involving hundreds of Bergmann glia during motor activity (Nimmerjahn et al. 2009). Sensory-and motor-driven astrocyte responses appear to primarily arise from glutamatergic input (Wang et al. 2006; Nimmerjahn et al. 2009), but startle responses are mediated by noradrenaline from the locus coeruleus (LC) (Ding et al. 2013). This is particularly interesting given the role of the LC in modulation of cortical activity (Aston-Jones and Cohen 2005; O’Donnell et al. 2012). In accord, recent studies suggest that astrocytes respond to local cortical activity when they are stimulated by norepinephrine release from LC projections (Paukert et al. 2014). It is likely that astrocyte responses to input arriving directly from the sensory system and those arriving from internal regulatory systems, such as the LC, play distinct roles in modulating/supporting neuronal activity, but this remains to be shown. Another interesting finding is that astrocytes in the visual cortex of ferrets show orientation and spatial frequency tuning, as measured by their Ca2+ responses, similar to neurons (Schummers et al. 2008). Similar findings have not been observed in mice (McCarthy laboratory; KD McCarthy, unpubl.). A major difference in the visual cortex of ferrets and mice is that ferrets show the columnar visual columns typical of higher mammals, whereas mice do not. These findings suggest, not surprisingly, that caution is needed when extrapolating findings among different rodents to higher-level organisms, such as primates. Overall, it is apparent that astrocytes in vivo respond in a correlated manner during neuronal activity with increases in Ca2+, and that the spatial and temporal characteristics of astrocyte Ca2+ responses vary dependent on the level and type of neural activity as well as with brain vigilance state (awake/anesthetized).

Intercellular Calcium Waves

One of the first observations made in this area was that cultured astroglia show intercellular Ca2+ waves that propagate long distances and can involve hundreds of cells (Cornell-Bell et al. 1990). This led to the suggestion that astrocytes in vivo might communicate over long distances via intercellular Ca2+ waves (Cornell-Bell et al. 1990). To date, there is little evidence that astrocytes in vivo show actively propagated intercellular Ca2+ waves that spread over long distances, but a variety of studies report widespread astrocyte Ca2+ responses in vivo in awake mice (Dombeck et al. 2007; Nimmerjahn et al. 2009; Ding et al. 2013) that may be mediated by the broad release of neuromodulators into large areas of brain tissue (Ding et al. 2013). This does not rule out the possibility that discrete clusters of astrocytes might be coupled through intercellular Ca2+ waves, and methods to monitor large cohorts (or all) astrocytes in vivo are needed. Moreover, one needs a computational framework to evaluate the probability distribution of time intervals between Ca2+ signals before we can determine whether signals in large populations of astrocytes are related or separate events. The mechanisms underlying intercellular Ca2+ waves have been studied extensively using cultured astroglia, and the overall consensus is that astroglia release ATP, which diffuses to neighboring cells to activate Gq-coupled purinergic receptors leading to increases in Ca2+ and consequent release of ATP to perpetuate the Ca2+ wave (Guthrie et al. 1999). Although the prevailing evidence suggests that gap junction–related proteins (pannexins/connexins) participate in the release of ATP from astroglia (Suadicani et al. 2004; Scemes and Spray 2012), alternate release pathways have also been described (Zhang et al. 2007; Kreft et al. 2009).

The Nature of Astrocyte Ca2+ Signals Measured In Vivo in Nonanesthetized Adult Mice

Technical developments from the Tank Laboratory (Princeton, NJ) have made it possible to image neurons and astrocytes in vivo during mouse behavior (Dombeck et al. 2007). Using these methods and two-photon microscopy on awake, head-fixed mice, these investigators discovered widespread astrocyte Ca2+ signals in layer two-thirds of the sensory cortex (Dombeck et al. 2007). Across a population of experiments, ∼11% of astrocytes displayed Ca2+ signals that were strongly correlated with running behavior; the rest were partially or not correlated (Dombeck et al. 2007). Beautiful and detailed studies using similar methods revealed three types of Ca2+ signals within Bergmann glia of the cerebellum (Nimmerjahn et al. 2009). Two types of Ca2+ signals were ongoing within the cerebellum and were termed “sparkles” and “bursts,” whereas a third form occurred in hundreds of Bergmann glia in a concerted manner during locomotor activity; these were termed “flares.” Interestingly, the sparkles occurred mainly in processes and were reduced by tetrodotoxin (TTX) and glutamate receptor antagonists, implying they were driven at least in part by action potential dependent glutamate release (Nimmerjahn et al. 2009). Bursts occurred spontaneously in mice at rest and appeared as expanding waves that encompassed ∼55 Bergmann glia (Nimmerjahn et al. 2009). These signals were not sensitive to TTX, but were abolished by PPADS, a nonspecific antagonist of ATP receptors, implying they were because of endogenous ATP (Nimmerjahn et al. 2009). Flares occurred during voluntary running and encompassed hundreds of Bergmann glia and were abolished by TTX and a glutamate receptor antagonist (Nimmerjahn et al. 2009). These studies elegantly show that a single type of astrocyte (i.e., the Bergmann glial cell) can display a variety of responses and mechanisms in vivo depending on what the mouse is doing. Moreover, during the course of these studies another fundamental observation was made. Anesthetics strongly disrupted Ca2+ signals within Bergmann glia (Nimmerjahn et al. 2009), recalling previous studies in the ferret visual cortex (Schummers et al. 2008). This insight has now been reproduced in studies of astrocytes in mouse cortex (Thrane et al. 2012). More recently, it has been shown that astrocyte Ca2+ responses in the mouse somatosensory cortex also encompass large populations of astrocytes and are driven by noradrenaline released from LC, which acts on α1 adrenoceptors on astrocytes (Ding et al. 2013). These investigators found that spontaneous Ca2+ signals were also driven by α1 adrenoceptors (Ding et al. 2013). Noradrenaline also engages Bergmann glia in the cerebellum and astrocytes in the visual cortex during vigilance in awake mice (Paukert et al. 2014).

The aforementioned in vivo studies represent a milestone because they provide a basis to explore and understand the physiological settings under which astrocytes respond to real-world experiences and behaviors that are engaged within the intact brain. Much more work is needed, but several general points are worth noting at this stage. First, anesthetics severely impair astrocyte Ca2+ signals and, hence, in vivo evaluations need to be performed on awake mice to faithfully study physiological Ca2+ signals. Second, a variety of Ca2+ signals can be observed in vivo, some are intrinsic, some driven by ATP, some by glutamate, and some by noradrenaline (Nimmerjahn et al. 2009; Ding et al. 2013; Paukert et al. 2014). What do these empirical observations mean? We suggest that when interpreting these studies it is important to avoid making strong generalizations based on observations on any one area of the brain, because the type of Ca2+ signal varies even within the cerebellum (Nimmerjahn et al. 2009), between brain areas, and also with the type of behavioral response being evaluated. Indeed, it has been convincingly argued that astrocyte heterogeneity will be reflected as diverse types of astrocyte Ca2+ signals in vivo (Nimmerjahn et al. 2009) and in situ (Tong et al. 2012). In support of this concept, our recent data for the CA3 region show that astrocytes respond to bursts of action potentials with slow quite global Ca2+ signals (Haustein et al. 2014), which is different to astrocyte responses elsewhere in the hippocampus (Di Castro et al. 2011; Panatier et al. 2011). Moreover, the differences between the CA1 and CA3 regions may be explained by the structural differences between astrocytes processes and their proximity to postsynaptic densities. Hence, generalizations based on specific examples in any one area of the brain may be limited in any broadly meaningful sense. Third, it has been suggested that in vivo and in situ astrocyte studies fundamentally differ, because Ca2+ signals in vivo are quite widespread, whereas those in situ are more local (Ding et al. 2013). This is an interesting point that merits further consideration. It is noteworthy, however, that Bergmann glia and cortical astrocytes both display local (i.e., within processes) and widespread Ca2+ signals (Nimmerjahn et al. 2009). Moreover, it has already been shown that stimulation of the Schaffer collaterals results in widespread responses in at least 45 astrocytes in the hippocampus in situ, and that this number varies depending on the pathway being stimulated (Bowser and Khakh 2004). Furthermore, hippocampal astrocytes in situ also display local Ca2+ signals in processes (Nett et al. 2002; Di Castro et al. 2011; Panatier et al. 2011; Shigetomi et al. 2013a; Haustein et al. 2014). A conservative interpretation, therefore, suggests that there may not be an insurmountable biological schism between in vivo and in situ studies (Ding et al. 2013), but more work is certainly needed. Indeed, several decades of neuronal studies in vitro and in situ were necessary and portentous for hypothesis-driven experiments in vivo; there is no obvious reason to believe astrocytes will be different in this regard. Fourth, an early study on the adult cortex showed that astrocyte Ca2+ responses evoked by whisker stimulation were partly mediated by synaptic release of glutamate acting on astrocyte mGluR5 receptors (Wang et al. 2006), whereas a recent study concluded that glutamatergic signaling is insufficient to trigger astrocyte Ca2+ signaling and that mGluR5 receptors were not expressed in adult astrocytes (Sun et al. 2013). The causes of these differences are not clear, but clearly in vivo astrocyte Ca2+ signals are complex and diverse in nature. It is likely that a better understanding of astrocyte Ca2+ signals in vivo will allow us to design better experiments to explore astrocyte responses in situ in which exploration of biophysical and molecular mechanisms is more feasible. Moreover, the use of head-mounted wearable fluorescence microscopes (Ghosh et al. 2011) will permit the study of astrocytes in awake mice in deeper brain structures (Kuga et al. 2011; Sasaki et al. 2011). Hence, a nuanced assessment suggests that studies in vivo and in situ are both necessary to explore physiological settings and biophysical mechanisms. In particular, pharmacological mechanisms are difficult to assess in vivo because drugs have to be applied at concentrations that are often far in excess of their equilibrium dissociation constants. At such concentrations, cherished pharmacological concepts of specificity and selectively begin to fall apart, and yet it is these very concepts that make pharmacology useful as an experimental tool (Kenakin 2006). From this perspective, reduced preparations will continue to be necessary to explore mechanisms.

APPROACHES TO ACTIVATE OR INACTIVATE ASTROCYTE Ca2+ SIGNALING

To explore the causative functional role(s) of astrocyte Ca2+ signaling, it is essential to be able to specifically interfere with astrocyte Ca2+ signaling in complex brain tissue. This is relatively straightforward with neurons where one can activate or silence neuronal activity using electrophysiological or optogenetic methods. However, it is much more difficult with astrocytes given that evoked Ca2+ signaling arises almost exclusively from the activation of GPCRs that, as a family, are present on all cells. An additional complication is that, under physiological conditions, it is possible that microdomains within an individual astrocyte respond to local neuronal activity without propagating the Ca2+ signal throughout the entire astrocyte (Di Castro et al. 2011; Panatier et al. 2011). Consequently, an astrocyte, which may envelop ∼100,000 synapses, may be simultaneously responding to many different signals with responses affecting different neuronal events.

A large number of different approaches have been used to increase astrocyte Ca2+ in situ (Fiacco et al. 2009). Early studies applied GPCR agonists that resulted in Ca2+ release from the ER in the presence of agents that blocked neuronal activity and neurotransmitter release (Porter and McCarthy 1995; Nett et al. 2002) or simply stimulated neuronal activity and monitored astrocyte Ca2+ responses (Porter and McCarthy 1996; Bowser and Khakh 2004). These early studies showed that astrocytes express GPCRs linked to Ca2+ mobilization and that these GPCRs could be activated by neuronal activity. However, these findings provided little insight into the functional role of astrocyte Ca2+ signals. There is little doubt that certain GPCRs linked to Ca2+ mobilization are enriched in astrocytes relative to other cell types in brain (Agulhon et al. 2010). A number of investigators have taken advantage of this to selectively activate astrocyte Ca2+ signaling (reviewed in Santello and Volterra 2009; Halassa and Haydon 2010; Davila et al. 2013). An advantage of this approach is that endogenous GPCRs distributed appropriately over the surface of astrocytes are being used to generate Ca2+ signals. Thus, one may argue that astrocyte Ca2+ signals are likely to modulate neural activity in ways similar to that occurring under physiological conditions. A concern in using endogenous GPCR ligands to understand the functional consequences of astrocyte Ca2+ signals is that it is impossible to rule out the possibility that the endogenous ligand did not directly activate neuronal GPCRs. To circumvent this issue, a number of laboratories have used caged Ca2+ or caged IP3 to specifically increase Ca2+ in individual astrocytes (Fellin et al. 2004; Fiacco and McCarthy 2004; Wang et al. 2013). This is accomplished using patch pipettes to load individual astrocytes with caged Ca2+ or caged IP3. A large increase in astrocyte Ca2+ that generally initiates in the soma and propagates throughout the astrocyte is observed following uncaging by flash photolysis (Fiacco and McCarthy 2004). An advantage of using caged IP3 in relation to caged Ca2+ is that uncaging IP3 leads to Ca2+ release from the ER, which is likely to be more physiological than uncaging Ca2+ directly. Both of these approaches have been used to show that increases in astrocyte Ca2+ can lead to the release of gliotransmitters that affect neuronal activity (Fellin et al. 2004; Fiacco and McCarthy 2004). A problem associated with both of these approaches is that the Ca2+ increases often observed are very large (relative to those that occur under physiological conditions) and may trigger events that rarely, if ever, occur under normal settings (Fiacco et al. 2009). Indeed, the precise relationship between the amplitude of Ca2+ signals within astrocytes and their potential to engage downstream signaling has not been systematically studied. In light of this, it has been cogently suggested that astrocyte Ca2+ signals should not be interpreted in a simple on/off or “binary” manner in relation to their ability for downstream signaling (Shigetomi et al. 2008). Information could be encoded by the amplitude, location, duration, spatial spread, and frequency of astrocyte Ca2+ signals; these quantitative details need to be explored in physiologically relevant compartments of astrocytes (Rusakov et al. 2011).

One of us (McCarthy) took a pharmacogenetic approach to circumvent many of the caveats associated with the approaches described above. We engineered a transgenic mouse model that enabled us to inducibly express a Gq-GPCR (linked to Ca2+ mobilization) in astrocytes that is not normally expressed in brain, does not respond to known receptor ligands released in brain, and whose receptor ligand does not activate known GPCRs present in brain (Fiacco et al. 2007) . The Gq-GPCR (MrgA1) is normally expressed in a subpopulation of sensory neurons and is activated by the peptide FMRF (Dong et al. 2001). Using this transgenic mouse model, we showed that MrgA1 was only expressed in astrocytes and that stimulation with FMRF led to a very similar temporal and spatial Ca2+ response as observed following stimulation of native astrocyte Gq-GPCRs (Fiacco et al. 2007). In contrast to our findings following uncaging of IP3 in astrocytes (Fiacco and McCarthy 2004), increasing Ca2+ via the activation of MrgA1 failed to affect basal or evoked synaptic transmission, or synaptic plasticity at the Schaffer collateral-CA1 synapse (Fiacco et al. 2007; Agulhon et al. 2010).

More recently, our laboratory (McCarthy) prepared a transgenic line that expresses an engineered Gq-GPCR known as hM3Dq driven by the GFAP promoter (Agulhon et al. 2013). hM3Dq is part of the designer receptor exclusively activated by designer drugs (DREADD) GPCR family of engineered GPCRs (Armbruster et al. 2007). DREADD receptors fail to respond to endogenous GPCR ligands but do respond to the otherwise biological inert molecule, clozapine-N-oxide (CNO) (Nichols and Roth 2009). Chronic cranial window and genetically encoded Ca2+ sensors were used to monitor astrocyte responses to an ip injection of CNO. Ca2+ responses similar to those elicited by endogenous ligands in brain slices were observed. Because CNO readily crosses the blood–brain barrier, for the first time, an analysis of the effect of activating astrocyte Gq-GPCR signaling on behavior could be performed. The activation of hM3Dq in GFAP+ cells led to a striking phenotype that included increases in blood pressure, heart rate, saliva formation, a decrease in body temperature, and potentiation of sedation caused by a GABAA agonist (Agulhon et al. 2013). Surprisingly, a similar phenotype occurs in GFAP-hM3Dq mice that also lack IP3R2s in which astrocyte Gq-GPCR-dependent Ca2+ responses are abolished (Petravicz et al. 2008). This finding emphasizes the point that Gq-GPCRs regulate a wide variety of signaling cascades in addition to Ca2+ and that these are likely to be important in physiology and behavior. More recent unpublished studies from our laboratory (McCarthy) indicates that a cKO of IP3R2 fails to affect several routinely measures of behavior including tests for spatial plasticity (Morris water maze) suggesting that astrocyte Ca2+ responses are likely involved in the fine tuning of behavior opposed to being required for major behavioral events.

Recently, there have been spectacular advances in the use of optogenetics to explore neurons (Fenno et al. 2011). Some of these methods are now being applied to studies of astrocytes (Gourine et al. 2010; Sasaki et al. 2012), but more work is needed to determine whether these approaches trigger physiological Ca2+ signals within astrocytes or, like caged compounds, if they trigger signals that tend to be large. A new approach with increased temporal control of astrocyte Ca2+ involves LiGluR (Li et al. 2012).

Not surprisingly, there are strengths and weaknesses associated with the use of pharmacogenetic and optogenetic methods to increase astrocyte Ca2+. The primary weakness of pharmacogenetic tools, such as DREADD receptors, is that it is difficult to limit the exposure time given that the ligand is typically administered systemically. This contrasts markedly with physiological responses that occur over seconds. A major strength of the pharmacogenetic approach is that the entire cascade of signaling molecules normally activated by GPCRs is activated, as opposed to a single downstream signal, such as Ca2+. Consequently, it is likely that the response is more physiological. The primary limitation of optogenetic excitation approaches is that astrocytes do not typically express voltage-gated ion channels permeable to Ca2+, meaning that the method is reliant on the Ca2+ permeability of molecules like channelrhodopsin. It is unclear how the profile of Ca2+ entry through channelrhodopsin-like molecules is related to physiological astrocyte Ca2+ signals. Consequently, it seems likely that the temporal and spatial characteristics of astrocyte Ca2+ increases using this approach more closely resemble those obtained by directly uncaging Ca2+. The primary advantage of the optogenetic approach to increasing astrocyte Ca2+ is potentially higher temporal control. A consideration with both pharmacogenetic and optogenetic tools is that neither method enables one to control the level or spatial distribution of engineered receptors/channels to sites normally activated in vivo. Hence, it is possible that both methods produce robust Ca2+ signals that fail to mimic physiological Ca2+ responses.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

We have summarized how astrocyte Ca2+ signals are measured, their properties, their mechanisms, and some of their physiological roles. In the last few years, there has been considerable work on evaluating how astrocyte Ca2+ signals may, or may not, regulate neuronal activity. These topics, and the controversy that surrounds them, has already been reviewed in great detail (Agulhon et al. 2008, 2012; Halassa and Haydon 2010; Zorec et al. 2012). The topic is also covered in an accompanying article on gliotransmission. Rather than restating the arguments here, we make a few general points of relevance.

First, much more detailed work is needed to study the properties and biophysics of astrocyte Ca2+ signals in processes (Fig. 1). These data seem necessary to form specific hypotheses to explore distinct types of Ca2+ signal. It will be necessary in these studies to determine how closely astrocyte Ca2+ responses, and the consequences of these responses in acute brain slices, reflect those occurring in vivo. It is also important to note that in vivo imaging has so far only been performed on the superficial layers of the brain in awake mice; it is unlikely that findings from these studies will be reflective of the brain as a whole. The power of GECIs will be further increased as newer transcriptional units are identified that enable the expression of GECIs and knockdown constructs in defined subpopulations of astrocytes. Further, a better understanding of the molecules localizing GPCRs to specific subcellular sites will be critical for mimicking, with cell specificity, physiological activation of Ca2+ signaling. Second, it seems certain that astrocyte Ca2+ activity and downstream effects vary among different brain regions, as recently shown by one of us (Haustein et al. 2014). Consequently, it will be important to develop technology that enables monitoring of astrocyte and neuron activity in vivo in regions currently inaccessible using available GECIs and two-photon microscopy. The development of red-shifted GECIs and improved fluorescence endoscopy methods that enable imaging deep within tissues will undoubtedly lead to major advances in our understanding of astrocyte-neuronal interactions in vivo. Also, an expanded palette of indicators may permit the simultaneous imaging of astrocyte and neuronal signaling at high rates and with high cell coverage within entire microcircuits. If so, such developments have the potential to markedly advance our understanding of the correlative relationships between neuronal encoding and astrocyte Ca2+ signaling, an area that remains largely unexplored, although important progress has been made recently (Poskanzer and Yuste 2011). Third, much more work is needed to identify, genetically delete, and then explore the functions of distinct Ca2+ signals. IP3R2 conditional knockout mice are very useful to explore the predominant store-mediated Ca2+ signals in astrocytes and are likely to clarify the role of GPCR-mediated Ca2+ fluxes in physiology and behavior. Similar approaches are now needed for other astrocyte Ca2+ signals. Identification of the proteins that mediate astrocyte Ca2+ signals will markedly advance our understanding of the role of Ca2+ signaling in physiology. Fourth, methods to trigger physiologically relevant astrocyte signals are essential as each of the available methods have merits and limitations. These efforts would benefit greatly from detailed knowledge of Ca2+ responses to physiological stimuli. This will be essential for the field to evaluate the physiological relevance of the various Ca2+ responses that have been reported so far. Further, a detailed understanding of the temporal and spatial characteristics of astrocyte responses under physiological conditions will be critical for progress in this field. We believe that an ideal way to study physiological responses is to determine the settings under which astrocytes display Ca2+ signals in vivo in awake behaving mice during real-world experiences, such as sensory and motor stimuli. Such experiments are now underway (Dombeck et al. 2007; Nimmerjahn et al. 2009; Thrane et al. 2012; Ding et al. 2013) and will guide in situ mechanistic studies. It is notable that in vivo studies that use anesthesia may not reveal physiological responses because anesthetics themselves affect Ca2+ responses within astrocytes (Schummers et al. 2008; Nimmerjahn et al. 2009; Thrane et al. 2012). Fifth, we need rigorous analytical regimes, detection software and models of astrocyte Ca2+ signals in vivo so that relevant biological questions can be framed precisely. Sixth, we need to develop testable concepts and experimental frameworks to explore the roles of astrocytes in model microcircuits that are relevant to behavioral endpoints in whole mice.

Once we can reliably measure, mimic, and block specific astrocyte Ca2+ signals with high temporal and spatial precision, then the field will be in a strong position to continue to explore the correlative and causative roles that Ca2+ signals may have for the functions of synapses, neurons, and circuits. These roles may affect synaptic transmission, vascular tone, synapse formation, synapse removal, plasticity, and inflammation. They may also include slower passive neuromodulatory functions driven by basal Ca2+ levels as recently suggested (Khakh and North 2012; Tong et al. 2012). Perhaps, equally likely is the possibility that Ca2+ signals may regulate the supportive and trophic functions of astrocytes, at least in part, through regulation of gene expression. The next decade of research in this area will continue to clarify the role of astrocytes in physiology, behavior, and neurological/psychiatric diseases as the availability of new tools enables investigators to selectively monitor, mimic, and block astrocyte Ca2+ signaling cascades in situ and in vivo. The next few years look very exciting for astrocyte biology.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We regret that we could not cite many worthy papers because of space constraints. B.S.K. and K.D.M. are grateful to current and past members of our laboratories for discussions. The Khakh laboratory is supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (NS060677, MH104069, MH099559) and the Cure Huntington's Disease Initiative (CHDI) Foundation. The McCarthy laboratory is supported by the NIH (NS020212, MH099564, NS081589, EY021190).

Footnotes

Editors: Ben A. Barres, Marc R. Freeman, and Beth Stevens

Additional Perspectives on Glia available at www.cshperspectives.org

REFERENCES

- Agulhon C, Petravicz J, McMullen AB, Sweger EJ, Minton SK, Taves SR, Casper KB, Fiacco TA, McCarthy KD 2008. What is the role of astrocyte calcium in neurophysiology? Neuron 59: 932–946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agulhon C, Fiacco TA, McCarthy KD 2010. Hippocampal short- and long-term plasticity are not modulated by astrocyte Ca2+ signaling. Science 327: 1250–1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agulhon C, Sun MY, Murphy T, Myers T, Lauderdale K, Fiacco TA 2012. Calcium signaling and gliotransmission in normal vs. reactive astrocytes. Front Pharmacol 3: 139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agulhon C, Boyt KM, Xie AX, Friocourt F, Roth BL, McCarthy KD 2013. Modulation of the autonomic nervous system and behaviour by acute glial cell Gq protein-coupled receptor activation in vivo. J Physiol 591: 5599–5609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akerboom J, Chen TW, Wardill TJ, Tian L, Marvin JS, Mutlu S, Calderón NC, Esposti F, Borghuis BG, Sun XR, et al. 2012. Optimization of a GCaMP calcium indicator for neural activity imaging. J Neurosci 32: 2601–2612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armbruster BN, Li X, Pausch MH, Herlitze S, Roth BL 2007. Evolving the lock to fit the key to create a family of G protein-coupled receptors potently activated by an inert ligand. Proc Natl Acad Sci 104: 5163–5168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aston-Jones G, Cohen JD 2005. Adaptive gain and the role of the locus coeruleus-norepinephrine system in optimal performance. J Comp Neurol 493: 99–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkin SD, Patel S, Kocharyan A, Holtzclaw LA, Weerth SH, Schram V, Pickel J, Russell JT 2009. Transgenic mice expressing a cameleon fluorescent Ca2+ indicator in astrocytes and Schwann cells allow study of glial cell Ca2+ signals in situ and in vivo. J Neursci Methods 181: 212–226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benediktsson AM, Schachtele SJ, Green SH, Dailey ME 2005. Ballistic labeling and dynamic imaging of astrocytes in organotypic hippocampal slice cultures. J Neurosci Methods 141: 41–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge MJ, Bootman MD, Roderick HL 2003. Calcium signalling: Dynamics, homeostasis and remodelling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 4: 517–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bischofberger J, Engel D, Li L, Geiger JR, Jonas P 2006. Patch-clamp recording from mossy fiber terminals in hippocampal slices. Nat Protoc 1: 2075–2081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowser DN, Khakh BS 2004. ATP excites interneurons and astrocytes to increase synaptic inhibition in neuronal networks. J Neurosci 24: 8606–8620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmignoto G, Haydon PG 2012. Astrocyte calcium signaling and epilepsy. Glia 60: 1227–1233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charles AC, Merrill JE, Dirksen ER, Sanderson MJ 1991. Intercellular signaling in glial cells: Calcium waves and oscillations in response to mechanical stimulation and glutamate. Neuron 6: 983–992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen TW, Wardill TJ, Sun Y, Pulver SR, Renninger SL, Baohan A, Schreiter ER, Kerr RA, Orger MB, Jayaraman V, et al. 2013. Ultrasensitive fluorescent proteins for imaging neuronal activity. Nature 499: 295–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clapham DE 2007. Calcium signaling. Cell 131: 1047–1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornell-Bell AH, Finkbeiner SM, Cooper MS, Smith SJ 1990. Glutamate induces calcium waves in cultured astrocytes: Long-range glial signaling. Science 247: 470–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dani JW, Chernjavsky A, Smith SJ 1992. Neuronal activity triggers calcium waves in hippocampal astrocyte networks. Neuron 8: 429–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davila D, Thibault K, Fiacco TA, Agulhon C 2013. Recent molecular approaches to understanding astrocyte function in vivo. Front Cell Neurosci 7: 272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Castro MA, Chuquet J, Liaudet N, Bhaukaurally K, Santello M, Bouvier D, Tiret P, Volterra A 2011. Local Ca2+ detection and modulation of synaptic release by astrocytes. Nat Neurosci 10: 1276–1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding F, O’Donnell J, Thrane AS, Zeppenfeld D, Kang H, Xie L, Wang F, Nedergaard M 2013. α1-Adrenergic receptors mediate coordinated Ca2+ signaling of cortical astrocytes in awake, behaving mice. Cell Calcium 54: 387–394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dombeck DA, Khabbaz AN, Collman F, Adelman TL, Tank DW 2007. Imaging large-scale neural activity with cellular resolution in awake, mobile mice. Neuron 56: 43–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong X, Han S, Zylka MJ, Simon MI, Anderson DJ 2001. A diverse family of GPCRs expressed in specific subsets of nociceptive sensory neurons. Cell 106: 619–632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fatatis A, Russell JT 1992. Spontaneous changes in intracellular calcium concentration in type I astrocytes from rat cerebral cortex in primary culture. Glia 5: 95–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fellin T, Pascual O, Gobbo S, Pozzan T, Haydon PG, Carmignoto G 2004. Neuronal synchrony mediated by astrocytic glutamate through activation of extrasynaptic NMDA receptors. Neuron 43: 729–743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenno L, Yizhar O, Deisseroth K 2011. The development and application of optogenetics. Annu Rev Neurosci 34: 389–412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiacco TA, McCarthy KD 2004. Intracellular astrocyte calcium waves in situ increase the frequency of spontaneous AMPA receptor currents in CA1 pyramidal neurons. J Neurosci 24: 722–732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiacco TA, Agulhon C, Taves SR, Petravicz J, Casper KB, Dong X, Chen J, McCarthy KD 2007. Selective stimulation of astrocyte calcium in situ does not affect neuronal excitatory synaptic activity. Neuron 54: 611–626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiacco TA, Agulhon C, McCarthy KD 2009. Sorting out astrocyte physiology from pharmacology. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 49: 151–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh KK, Burns LD, Cocker ED, Nimmerjahn A, Ziv Y, Gamal AE, Schnitzer MJ 2011. Miniaturized integration of a fluorescence microscope. Nat Methods 8: 871–878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gourine AV, Kasymov V, Marina N, Tang F, Figueiredo MF, Lane S, Teschemacher AG, Spyer KM, Deisseroth K, Kasparov S 2010. Astrocytes control breathing through pH-dependent release of ATP. Science 329: 571–575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guthrie PB, Knappenberger J, Segal M, Bennett MVL, Charles AC, Kater SB 1999. ATP released from astrocytes mediates glial calcium waves. 19: 520–528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halassa MM, Haydon PG 2010. Integrated brain circuits: Astrocytic networks modulate neuronal activity and behavior. Annu Rev Physiol 72: 335–355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haustein MD, Kracun S, Lu X-H, Shih T, Jackson-Weaver O, Tong X, Xu J, Yang XW, O’Dell T, J., Marvin JS, et al. 2014. Conditions and constraints for astrocyte calcium signaling in the hippocampal mossy fiber pathway. Neuron 82: 413–429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hires SA, Tian L, Looger LL 2008. Reporting neural activity with genetically encoded calcium indicators. Brain Cell Biol 36: 69–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenakin TP 2006. A pharmacology primer: Theory, applications and methods. Academic, London. [Google Scholar]

- Khakh BS, North RA 2012. Neuromodulation by extracellular ATP and P2X receptors in the CNS. Neuron 76: 51–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreft M, Potokar M, Stenovec M, Pangrsic T, Zorec R 2009. Regulated exocytosis and vesicle trafficking in astrocytes. Ann NY Acad Sci 1152: 30–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuga N, Sasaki T, Takahara Y, Matsuki N, Ikegaya Y 2011. Large-scale calcium waves traveling through astrocytic networks in vivo. J Neurosci 31: 2607–2614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li D, Hérault K, Isacoff EY, Oheim M, Ropert N 2012. Optogenetic activation of LiGluR-expressing astrocytes evokes anion channel-mediated glutamate release. J Physiol 590: 855–873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li D, Agulhon C, Schmidt E, Oheim M, Ropert N 2013. New tools for investigating astrocyte-to-neuron communication. Front Cell Neurosci 7: 193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malarkey EB, Ni Y, Parpura V 2008. Ca2+ entry through TRPC1 channels contributes to intracellular Ca2+ dynamics and consequent glutamate release from rat astrocytes. Glia 56: 821–835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melom JE, Littleton JT 2013. Mutation of a NCKX eliminates glial microdomain calcium oscillations and enhances seizure susceptibility. J Neurosci 33: 1169–1178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nedergaard M, Rodríguez JJ, Verkhratsky A 2010. Glial calcium and diseases of the nervous system. Cell Calcium 47: 140–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neher E 2000. Some quantitative aspects of calcium fluorimtery. In Imaging neurons: A laboratory manual (ed. Yuste R, Lanni F, Konnerth A), Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nett WJ, Oloff SH, McCarthy KD 2002. Hippocampal astrocytes in situ exhibit calcium oscillations that occur independent of neuronal activity. J Neurophysiol 87: 528–537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols CD, Roth BL 2009. Engineered G-protein coupled receptors are powerful tools to investigate biological processes and behaviors. Front Mol Neurosci 2: 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nimmerjahn A, Kirchhoff F, Kerr JN, Helmchen F 2004. Sulforhodamine 101 as a specific marker of astroglia in the neocortex in vivo. Nat Methods 1: 31–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nimmerjahn A, Mukamel EA, Schnitzer MJ 2009. Motor behavior activates Bergmann glial networks. Neuron 62: 400–412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell J, Zeppenfeld D, McConnell E, Pena S, Nedergaard M 2012. Norepinephrine: A neuromodulator that boosts the function of multiple cell types to optimize CNS performance. Neurochem Res 37: 2496–2512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palygin O, Lalo U, Verkhratsky A, Pankratov Y 2010. Ionotropic NMDA and P2X1/5 receptors mediate synaptically induced Ca2+ signalling in cortical astrocytes. Cell Calcium 48: 225–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panatier A, Vallée J, Haber M, Murai KK, Lacaille JC, Robitaille R 2011. Astrocytes are endogenous regulators of basal transmission at central synapses. Cell 146: 785–798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pankratov Y, Lalo U 2014. Calcium permeability of ligand-gated Ca2+ channels. Eur J Pharmacol 739: 60–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paukert M, Agarwal A, Jaepyeong C, Doze VA, Kang JU, Bergles DW 2014. Norepinephrine controls astroglial responsiveness to local circuit activity. Neuron 82: 1263–1270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petravicz J, Fiacco TA, McCarthy KD 2008. Loss of IP3 receptor-dependent Ca2+ increases in hippocampal astrocytes does not affect baseline CA1 pyramidal neuron synaptic activity. J Neurosci 28: 4967–4973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter JT, McCarthy KD 1995. GFAP-positive hippocampal astrocytes in situ respond to glutamatergic neuroligands with increases in [Ca2+]i. Glia 13: 101–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter JT, McCarthy KD 1996. Hippocampal astrocytes in situ respond to glutamate released from synaptic terminals. J Neurosci 16: 5073–5081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poskanzer KE, Yuste R 2011. Astrocytic regulation of cortical UP states. Proc Natl Acad Sci 108: 18453–18458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rand MN, Leinders-Zufall T, Agulian S, Kocsis JD 1994. Calcium signals in neurons. Nature 371: 291–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeves A, Shigetomi E, Khakh BS 2011. Bulk loading of calcium indicator dyes to study astrocyte physiology: Key limitations and improvements using morphological maps. J Neurosci 31: 9353–9358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rusakov DA, Zheng K, Henneberger C 2011. Astrocytes as regulators of synaptic function: A quest for the Ca2+ master key. Neuroscientist 17: 513–523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell JT 2011. Imaging calcium signals in vivo: A powerful tool in physiology and pharmacology. Br J Pharmacol 163: 1605–1625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santello M, Volterra A 2009. Synaptic modulation by astrocytes via Ca2+-dependent glutamate release. Neuroscience 158: 253–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki T, Kuga N, Namiki S, Matsuki N, Ikegaya Y 2011. Locally synchronized astrocytes. Cereb Cortex 21: 1889–1900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki T, Beppu K, Tanaka KF, Fukazawa Y, Shigemoto R, Matsui K 2012. Application of an optogenetic byway for perturbing neuronal activity via glial photostimulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci 109: 20720–20725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scanziani M, Häusser M 2009. Electrophysiology in the age of light. Nature 461: 930–939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scemes E, Spray DC 2012. Extracellular K+ and astrocyte signaling via connexin and pannexin channels. Neurochem Res 37: 2310–2316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schummers J, Yu H, Sur M 2008. Tuned responses of astrocytes and their influence on hemodynamic signals in the visual cortex. Science 320: 1638–1643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao Y, McCarthy KD 1993. Quantitative relationship between alpha 1-adrenergic receptor density and the receptor-mediated calcium response in individual astroglial cells. Mol Pharmacol 44: 247–254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shigetomi E, Bowser DN, Sofroniew MV, Khakh BS 2008. Two forms of astrocyte calcium excitability have distinct effects on NMDA receptor-mediated slow inward currents in pyramidal neurons. J Neurosci 28: 6659–6663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shigetomi E, Kracun S, Khakh BS 2010a. Monitoring astrocyte calcium microdomains with improved membrane targeted GCaMP reporters. Neuron Glia Biol 6: 183–191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shigetomi E, Kracun S, Sofroniew MV, Khakh BS 2010b. A genetically targeted optical sensor to monitor calcium signals in astrocyte processes. Nat Neurosci 13: 759–766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shigetomi E, Tong X, Kwan KY, Corey DP, Khakh BS 2011. TRPA1 channels regulate astrocyte resting calcium and inhibitory synapse efficacy through GAT-3. Nat Neurosci 15: 70–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shigetomi E, Bushong EA, Haustein MD, Tong X, Jackson-Weaver O, Kracun S, Xu J, Sofroniew MV, Ellisman MH, Khakh BS 2013a. Imaging calcium microdomains within entire astrocyte territories and endfeet with GCaMPs expressed using adeno-associated viruses. J Gen Physiol 141: 633–647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shigetomi E, Jackson-Weaver O, Huckstepp RT, O’Dell TJ, Khakh BS 2013b. TRPA1 channels are regulators of astrocyte basal calcium levels and long-term potentiation via constitutive d-serine release. J Neurosci 33: 10143–10153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SJ 1992. Do astrocytes process neural information? Prog Brain Res 94: 119–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith S 1994. Neural signalling. Neuromodulatory astrocytes. Curr Biol 4: 807–810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuart GJ, Dodt HU, Sakmann B 1993. Patch-clamp recordings from the soma and dendrites of neurons in brain slices using infrared video microscopy. Pflugers Arch 423: 511–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suadicani SO, Flores CE, Urban-Maldonado M, Beelitz M, Scemes E 2004. Gap junction channels coordinate the propagation of intercellular Ca2+ signals generated by P2Y receptor activation. Glia 48: 217–229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun W, McConnell E, Pare JF, Xu Q, Chen M, Peng W, Lovatt D, Han X, Smith Y, Nedergaard M 2013. Glutamate-dependent neuroglial calcium signaling differs between young and adult brain. Science 339: 197–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thrane AS, Rangroo Thrane V, Zeppenfeld D, Lou N, Xu Q, Nagelhus EA, Nedergaard M 2012. General anesthesia selectively disrupts astrocyte calcium signaling in the awake mouse cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci 109: 18974–18979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian L, Hires SA, Mao T, Huber D, Chiappe ME, Chalasani SH, Petreanu L, Akerboom J, McKinney SA, Schreiter ER, et al. 2009. Imaging neural activity in worms, flies and mice with improved GCaMP calcium indicators. Nat Methods 6: 875–881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong X, Shigetomi E, Looger LL, Khakh BS 2012. Genetically encoded calcium indicators and astrocyte calcium microdomains. Neuroscientist 19: 274–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsien RY 1988. Fluorescence measurement and photochemical manipulation of cytosolic free calcium. Trends Neurosci 11: 419–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsien RY 1989. Fluorescent probes of cell signaling. Annu Rev Neurosci 12: 227–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Lou N, Xu Q, Tian GF, Peng WG, Han X, Kang J, Takano T, Nedergaard M 2006. Astrocytic Ca2+ signaling evoked by sensory stimulation in vivo. Nat Neurosci 9: 816–823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang F, Smith NA, Xu Q, Goldman S, Peng W, Huang JH, Takano T, Nedergaard M 2013. Photolysis of caged Ca2+ but not receptor-mediated Ca2+ signaling triggers astrocytic glutamate release. J Neurosci 33: 17404–17412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuste R, Katz LC 1991. Control of postsynaptic Ca2+ influx in developing neocortex by excitatory and inhibitory neurotransmitters. Neuron 6: 333–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zariwala HA, Borghuis BG, Hoogland TM, Madisen L, Tian L, De Zeeuw CI, Zeng H, Looger LL, Svoboda K, Chen TW 2012. A Cre-dependent GCaMP3 reporter mouse for neuronal imaging in vivo. J Neurosci 32: 2131–2141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Chen G, Zhou W, Song A, Xu T, Luo Q, Wang W, Gu XS, Duan S 2007. Regulated ATP release from astrocytes through lysosome exocytosis. Nat Cell Biol 9: 945–953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zlatkine P, Mehul B, Magee AI 1997. Retargeting of cytosolic proteins to the plasma membrane by the Lck protein tyrosine kinase dual acylation motif. J Cell Sci 110: 673–679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zorec R, Araque A, Carmignoto G, Haydon PG, Verkhratsky A, Parpura V 2012. Astroglial excitability and gliotransmission: An appraisal of Ca2+ as a signalling route. ASN Neuro 4: e00080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]