Abstract

Despite the recent expansion of peptide drugs, delivery remains a challenge due to poor localization and rapid clearance. Therefore, a hydrogel-based platform technology was developed to control and sustain peptide drug release via matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) activity. Specifically, hydrogels were composed of poly(ethylene glycol) and peptide drugs flanked by MMP substrates and terminal cysteine residues as crosslinkers. First, peptide drug bioactivity was investigated in expected released forms (e.g., with MMP substrate residues) in vitro prior to incorporation into hydrogels. Three peptides (Qk (from Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor), SPARC113, and SPARC118 (from Secreted Protein Acidic and Rich in Cysteine)) retained bioactivity and were used as hydrogel crosslinkers in full MMP degradable forms. Upon treatment with MMP2, hydrogels containing Qk, SPARC113, and SPARC118 degraded in 6.7, 6 and 1 days, and released 5, 8 and, 19% of peptide, respectively. Further investigation revealed peptide drug size controlled hydrogel swelling and degradation rate, while hydrophobicity impacted peptide release. Additionally, degraded Qk, SPARC113, and SPARC118 releasing hydrogels increased endothelial cell tube formation 3.1, 1.7, and 2.8-fold, respectively. While pro-angiogenic peptides were the focus of this study, the design parameters detailed allow for adaptation of hydrogels to control peptide release for a variety of therapeutic applications.

Keywords: Peptide, Hydrogel, Controlled drug release, Matrix metalloproteinase, Enzymatically degradable

1. Introduction

Peptide drugs have been identified for a variety of applications including to promote vascularization [1, 2], reduce inflammation [3, 4], and as cancer therapeutics [5, 6]. Peptides typically mimic the bioactivity of larger proteins or growth factors, and offer many advantages over traditional protein delivery. Due to small sizes, peptides can be produced synthetically and delivered at concentrations higher than whole proteins while maintaining high specificity to targets. Additionally, peptides often do not require complex tertiary structures for bioactivity, resulting in lower susceptibility to denaturation and degradation in vivo [1]. As peptides often do not fully recapitulate protein bioactivities, some reports indicate peptides may need to be delivered at higher doses to achieve similar therapeutic effects [7], while other studies indicate that at equivalent molar doses of peptides and proteins offer similar bioactivities [2]. Similar to proteins, however, peptides suffer from rapid clearance and poor pharmacokinetics, thus motivating the development of controlled release systems [8].

Numerous methods for systemic delivery of peptide drugs have been developed, including the use of liposomes [9], poly(lactide-co-glycolide) (PLGA) microparticles [10], and chitosan nanoparticles [11]. However, these drug delivery systems are not tissue-specific, and methods to achieve targeted, tissue-specific peptide delivery are poorly developed [12]. Bolus injection of peptides is often used [13, 14], necessitating repeat injections to achieve longitudinal therapeutic concentrations. Osmotic pumps can be used to achieve prolonged peptide delivery [2]; however, pumps must be removed after delivering their payload, necessitating an additional revision surgery. Diffusion-mediated peptide release can be achieved using polymers such as Hydron [7, 15] or hydrogels such as ReGel (PLGA-b-PEG-b-PLGA) [16], pluronics [2], or Matrigel [17]. However, delivery using these approaches occurs over pre-dictated, and not necessarily therapeutically-relevant, timeframes. To more closely meet tissue demands, stimuli-responsive drug delivery systems can be developed that allow for delivery controlled by the local tissue microenvironment, showing improved tissue healing over bolus delivery of the therapeutic molecule [18]. However, stimuli-responsive materials have not yet been developed for peptide drug delivery [12].

Poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) hydrogels have been used to deliver therapeutic molecules such as peptides and proteins, and offer numerous advantages as controlled release systems [19]. PEG hydrogels are highly hydrophilic, inert, and biocompatible. Additionally, due to their synthetic nature, PEG hydrogels have highly tunable degradation profiles and mechanical properties [20]. Moreover, PEG hydrogels can be formed using a number of synthetic schemes that are compatible with peptide incorporation. For example, norbornene-functionalized PEG (PEGN) can be reacted with thiol-containing crosslinkers to form hydrogel networks via step-growth photopolymerizations [21]. This polymerization strategy is cytocompatible, produces homogeneous PEG-peptide networks, and allows for facile incorporation of peptides that include cysteine (thiol R-group) amino acids [21, 22]. Thiol-ene based PEG hydrogels can also be rendered enzymatically-degradable through the incorporation of proteolytically-responsive peptide crosslinkers [23]. Enzymatically-responsive peptide sequences have been used to control the temporal availability of the cell adhesion peptide RGD within non-degradable PEG hydrogels [24], and to provide responsive release of tethered vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) [18]. When employed to treat a mouse model of hindlimb ischemia, enzymatically-responsive VEGF delivery results in greater vascular reperfusion compared to bolus injection, presumably due to extended therapeutic protein delivery [18]. This result further motivates the development of sustained peptide delivery systems.

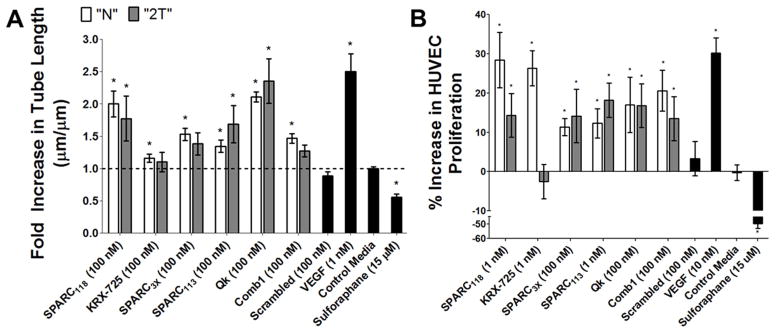

The goal of this study was to develop poly(ethylene glycol) hydrogels that provide sustained, enzymatically-responsive release of peptide drugs (Figure 1). To test the impact of substrate “tails” left on the peptide drugs upon release from the hydrogels (LRAG-peptide-IPES; “2T”), six bioactive peptide sequences were identified from literature as candidates for incorporation into enzymatically-responsive hydrogels. Pro-angiogenic peptides were the focus of this work due to the plethora of established therapeutic peptides and well-defined in vitro assays available [25]. First, the effects of residual enzyme substrate amino acid “tails” on the peptide drugs after enzyme-mediated release were assessed using the human umbilical vein endothelial cell (HUVEC) tube formation and proliferation assays. Three peptide drugs retained bioactivity in released forms. These and three additional peptides encompassing a range of peptide sizes and hydrophobicities were incorporated into PEG hydrogels via enzymatically responsive linkers (C IPES↓LRAG-peptide-IPES↓LRAG C; degradable linker, “DL”). The enzymatically responsive sequence IPES↓LRAG was utilized as it is susceptible to matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) 1, 2, 3, 7, 9 & 14 [26], many of which are expressed at increased levels in diseased or regenerating tissues [27–32]. Incorporating the therapeutic peptide as the hydrogel crosslinker maximizes peptide drug concentrations within the hydrogel, but also inherently links peptide drug release to hydrogel degradation. The resulting hydrogels were characterized and enzymatically-responsive hydrogel degradation and “2T” peptide release upon treatment of gels with MMP2 was investigated. The bioactivity of degraded enzymatically-responsive peptide drug-releasing hydrogels were then assessed in vitro using the HUVEC tube formation assay.

Figure 1.

Poly(ethylene glycol) hydrogels designed to provide sustained, enzymatically-responsive release of peptide drugs. PEG hydrogels are crosslinked via thiol-ene photopolymerization between terminal norbornene groups on PEG macromers and thiol-containing cysteine amino acids. By flanking therapeutic peptide sequences with the enzymatically degradable sequence IPES↓LRAG, enzymatically responsive hydrogel degradation and peptide release can be achieved. ↓ indicates cleavage site.

2. Materials and Methods

All materials were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich unless otherwise noted. Cells and cell culture materials were obtained from Lonza unless otherwise noted.

2.1. Peptide synthesis

Peptides (Table 1) were synthesized on Fmoc-Gly-Wang resin (EMD) using a Liberty1 automated peptide synthesizer with UV monitoring (CEM). Amino acids (AAPPTec) were prepared at 0.2 M in N-methylpyrrolidone (NMP). 5% piperazine (Alfa Aesar) in dimethylformamide (DMF, Fisher Scientific) was used for deprotection, 0.5 M O-Benzotriazole-N,N,N’,N’-tetramethyl-uronium-hexafluoro-phosphate (HBTU, AnaSpec) in DMF was used as the activator, and 2 M diisopropylethylamine (DIEA, Alfa Aesar) in NMP was used as the activator base, except for Qk(DL), SPARC113(DL), Scrambled(DL), and SPARC3X(DL) where 0.5 M diisopropylcarbodiimide (DIC, Chem-Impex International) in DMF was used as the activator and 1 M hydroxybenzotriazole (HOBt, Advanced ChemTech) in DMF used as the activator base. Peptides were cleaved from resin in a cleavage cocktail composed of 92.5 vol% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA, Alfa Aesar) and 2.5 vol% each triisopropylsilane (Alfa Aesar), 3,6-dioxa-1,8-octanedithiol (Alfa Aesar), and distilled, deionized water (ddH2O) for 2–3 hours. For peptides containing arginine, 2.5 vol% thioanisole (Alfa Aesar) was added to the cleavage cocktail and cleavage time increased to 4–5 hours to aid in the removal of 2,2,4,6,7-pentamethyldihydrobenzofuran-5-sulfonyl (Pbf) protecting groups. After cleavage, resin was removed by vacuum filtration and peptide solutions precipitated in ice cold diethyl ether. Peptides were collected by centrifugation, and washed four times in diethyl ether.

Table 1.

Peptide drugs and model drugs investigated. Standard amino acid abbreviations are used.

| Peptide Drug/Model Drug | Sequence | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| SPARC118 | KKGHK | Cu2+ binding region of SPARC [33, 34]; Small, hydrophilic peptide |

| SmPho | KLVPLA | Model of small, hydrophobic peptide |

| KRX-725 | MRPYDANKR | The second intracellular loop of Sphingosine 1-phosphate 3 [7] |

| SPARC3X | KKGHKKGHKKGHK | Triplet of SPARC118; Large, hydrophilic peptide; 3 repeats of SPARC118 |

| SPARC113 | TLEGTKKGHKLHLDY | Basic region of SPARC [33, 34] |

| Qk | KLTWQELYQLKYKGI | 17–25 α-helix region of VEGF165 [1, 2]; Large, hydrophobic peptide |

| Comb1 | DINE(S)EIGAPAGEETEVTVEGLEPG | Combination of EGF-like domain from Fibrillin 1 and Fibronectin III-like domain of Tenascin X [35] |

| Scrambled | GLKEQSPRKHRLG | Scrambled control peptide |

|

| ||

| Native “N” form | peptide drug-G | No additional Gly added to C-termini of Comb1 or Scrambled |

| Two-tailed “2T” form | LRAG-peptide drug-IPES G | No additional Ile added to C-termini of Qk |

| Degradable linker | C IPES↓LRAG-peptide drug- | Qk(DL): EEEE C IPES↓LRAG |

| “DL” form | IPES↓LRAG C G | KLTWQELYQLKYKG IPES↓LRAG C EEEE G |

(S) indicates serine amino acids used in place of cysteine to prevent intrasequence peptide drug tethering to hydrogel networks. ↓ indicates MMP cleavage site.

Expected peptide molecular weights were confirmed using a Bruker AutoflexIII Smartbeam Matrix Assisted Laser Desorption Ionization-Time of Flight (MALDI-ToF) mass spectrometer, using 50/50 ddH2O/acetonitrile with 0.1% TFA as the solvent, and α-Cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid (Tokyo Chemical Industry) as the matrix, with calibrations performed using the Care peptide standards (Bruker 206195). Peptides were dialyzed in ddH2O (1–500 or 1000 MWCO tubing, Spectrum Laboratories) overnight and collected by lyophilization. Peptide purity was assessed by High Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC, Shimadzu Prominence) with a Kromasil Eternity C18 column (4.6 x 50 mm). Water and acetonitrile containing 1% TFA were used as the mobile phases and samples were run using gradients from 5% to 95% acetonitrile at 0.5 mL/minute. Peptide elution was monitored using a UV/Vis detector (SPA-20AV, Shimadzu Prominance) at 214 nm. Peptide purity (~ 90%) was determined by comparing target peak area to total area, adjusting for background from buffer-alone injection. Peptide concentrations were assessed via absorbance at 205 nm using an Evolution 300 UV/Vis detector (Thermo Scientific) [36]. Solid peptide and stock peptide solutions in PBS were stored at -20 ºC until use.

2.2. Norbornene functionalization of poly(ethylene glycol)

4-arm 10 kDa PEG (JenKem Technologies USA) was functionalized with norbornene (PEGN) as previously described [21]. Functionalization was determined (> 95%) with 1H-NMR using a Bruker Avance 400 MHz spectrometer, and deuterated chloroform as the solvent (δ = 6.25 - 5.8 ppm (8 H/molecule, norbornene vinyl protons, multiplet), 4.35 – 4.05 ppm (8 H/molecule, −COOCH2−, doublet), 3.9 – 3.35 ppm (892 H/molecule, −CH2CH2O− , multiplet)). The final product was dialyzed overnight in ddH2O, using 1000 MWCO dialysis tubing and collected by lyophilization. Functionalized PEG was stored at −20 ºC until use.

2.3. Human umbilical vein endothelial cell culture

HUVECs were cultured in Endothelial Growth Media 2 (EGM-2; Endothelial Basal Media-2 (EBM-2) containing EGM-2 SingleQuots) for at least two passages after thawing from cryostorage before use. Cells were maintained at 37 ºC with 5% CO2, split 1:4 using 0.25% Trypsin-EDTA in PBS, and used prior to passage 10. EBM-2 media with 2.5% fetal bovine serum (Atlanta Biologicals), 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 U/mL streptomycin, and 250 ng/mL amphotericin B (Thermo Scientific) was used as control media for the angiogenic assays.

2.4. HUVEC tube formation assay

Reduced growth factor Matrigel (BD Biosciences) was thawed overnight on ice at 4 ºC, diluted to 7.8 mg/mL with control media, and polymerized via incubation at 37 ºC for 30 minutes (150 μL per well of a 48-well plate). HUVECs (1.2×105 cells/mL) were suspended in either control media alone, or control media containing peptide drugs or controls. Cell solutions (200 μL/well) were placed on the polymerized Matrigel. Cells were incubated at 37 ºC for 8 hours before fluorescent imaging (0.5 μL/mL calcein AM, Invitrogen) using a temperature and humidity-controlled chamber (Pathology Devices) on a Nikon Eclipse Ti 2000 inverted light microscope [37]. Fluorescent images were converted to 16-bit greyscale and inverted in ImageJ for quantification using the image analysis software Angioquant [38]. Treatment with Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF, PeproTech) was used as a pro-proliferative positive control [39] and treatment with Sulforophane (EMD Milipore) was used as an anti-proliferative negative control [40] for both in vitro assays. Each plate contained a control media group to account for plate-to-plate variability.

2.5. HUVEC proliferation assay

HUVECs were suspended in control media at 2.0×104 cells/mL. 0.5 mL of the cell solution was seeded in each well of a 24-well plate. To achieve uniform cell adhesion, cells were allowed to adhere at room temperature for 1 hour before being transferred to the incubator [41]. 16 hours later, cells were washed twice with PBS and treated with 0.5 mL of either control media with or without peptide drugs or controls. A preliminary dose screening study (data not shown) was conducted to identify concentration at which each “N” peptide induced proliferation, and that concentration was used for both the “N” and “2T” treatments. Media was changed daily, and after 72 hours cells were washed twice with PBS, and lysed via sonication in 1x TE buffer (10 mM Tris, 1 mM EDTA in ddH2O, pH 7.5). DNA content was quantified using the Quant-iT picoGreen dsDNA quantification assay (Invitrogen). Each plate contained a control media group to account for plate-to-plate variability.

2.6. Peptide property predictions

Peptide structure was predicted using the Pepfold 1.5 de novo structure prediction server, and displayed in cartoon mode color-coded by group [42]. Peptide characteristics (hydropathy) were calculated using classifications from Lehninger Principles of Biochemistry [43], as well as the Kyte-Doolittle [44] and Hopp-Woods [45] hydropathy protein characterization methods.

2.7. Hydrogel formation

Peptide-crosslinked PEG hydrogels were formed via thiol-ene photopolymerizations. Cysteine-terminated peptides and 4-arm, 10 kDa PEGN were dissolved in PBS, with the exception of Qk(DL), which was dissolved in a 50/50 mixture of ddH2O and acetonitrile, in a 1:1 thiol:ene ratio to form a precursor solution containing 10 wt% PEG and 0.05 wt% lithium phenyl-2,4,6-trimethylbenzoylphosphinate (LAP, synthesized as previously described [46]). 40 μL of hydrogel precursor solution was then injected into a custom cylindrical mold and exposed to 365 nm UV light for 10 minutes (intensity ~ 2.5 mW/cm2), resulting in hydrogel polymerization (final gel diameter ~ 5 mm, height ~ 2 mm).

2.8. Hydrogel characterization

Hydrogels were swollen in buffer (50 mM Tricine (Acros Organics), 50 mM NaCl, 10 mM CaCl2, 50 μM ZnCl2 (Alfa Aesar), and 0.05 wt% Brij35 (Alfa Aesar) in ddH2O, pH 7.4) at 37 °C for 24 hours to achieve equilibrium swelling before characterization. Hydrogel images were collected using a Canon E05 Rebel T2i digital camera. Mass swelling ratio was determined by measuring equilibrium swelling and dry gel mass after lyophilization. The efficiency of peptide incorporation into the hydrogels was measured by collecting the buffer solution and quantifying the amount of peptide released into buffer via absorbance at 205 nm, as previously described (section 2.1). The amount of peptide incorporated into the gel but not fully crosslinked was quantified by incubating gels in 1 mL of 0.35 mg/mL Ellman’s reagent in PBS for 30 minutes, then measuring absorbance at 405 nm on a Tecan infiniteM200 microplate reader, and comparing to a standard curve generated using peptide alone [47].

2.9. Hydrogel degradation studies

After formation, hydrogels were stored in buffer at 37 °C for 24 hours, at which point solutions were changed to either fresh buffer, or buffer containing 10 nM recombinant human MMP2 (PeproTech). As MMP2 inactivates over time [23], MMP2 solutions were collected and replaced every 48 hours. For consistency, buffer solutions were collected and replaced every 48 hours as well. Hydrogel incubation solutions were stored at −80 °C for subsequent peptide release quantification. Gels were inspected daily until complete degradation occurred, for a maximum of 10 days.

2.10. Quantification of peptide release

The amount of “2T” peptide released into solution was quantified by HPLC, as described in section 2.1. The released concentration of “2T” peptide was determined by integrating peak area and comparing to standard curves generated using the “2T” form of the peptides.

2.11. In vitro efficacy of degraded hydrogels

Hydrogels were formed, stored in buffer at 37 °C fo r 24 hours, and then degraded in 1 mL of 10 nM MMP2 containing buffer. To maintain MMP bioactivity without increasing degradation solution volume, additional MMP2 (10 μmol/mL) was introduced every other day until hydrogels had fully degraded. Degraded hydrogels were collected, the MMP2 removed by centrifugal filtration (Ultracel 30K, Millipore), and the amount of “2T” peptide released determined as previously described (section 2.10). Degraded gel solutions were diluted in control media for the tube formation assay such that the final concentration of released SPARC118(2T) was 100 nM. The degraded gel:media ratio was kept constant across all degraded gel types. Degraded gel bioactivity was then assessed using the tube formation assay (~1/7,000th of a gel per well), as previously described (section 2.4), with control media containing buffer at equivalent amounts as the degraded gel groups.

2.12. Statistical analysis

Data assembly, normalization, and calculations were performed in Microsoft Excel 2010 v14.0. Figures were produced and statistical analysis performed in Graphpad Prism 5.04. Peptide bioactivity (Figure 2) data was evaluated with two-sample t-tests (Mann-Whitney U when data was non-normal), due to ANOVA overprotecting α and potentially rejecting significance simply due to the large number of peptides being investigated. Gel characterization was analyzed using a one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc testing (Figure 4). Hydrogel degradation and “2T” peptide release was analyzed using a two-way ANVOA with Bonferroni post-hoc testing (Figure 5). Relationships between peptide characteristics and hydrogel behavior were analyzed using linear regression, and the value of the slope compared to 0 using an F-test (Figure 6). Degraded gel tube formation (Figure 7) was analyzed using a Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn’s post-hoc test, as D’Agostino & Pearson omnibus testing showed data was not normally distributed. p<α =0.05 was considered significant for all analyses. All experiments were performed at least in duplicate; n=6–12 as specified in figure legends; data is presented as mean ± standard error of measurements (SEM) for all figures and reported values.

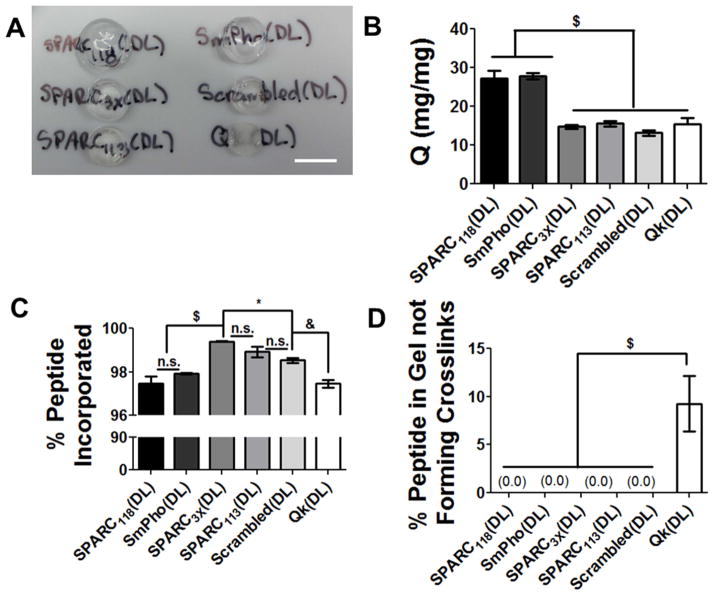

Figure 2.

Effects of residual “tails” from MMP-degradable peptide sequence on peptide bioactivity. (A) Fold increase in tube length over control media with peptide treatment and (B) percent increase in HUVEC proliferation, quantified by measuring DNA content, over control media after 3 days of peptide treatment. White bars indicate “N” peptide; grey bars indicate “2T” peptide; black bars indicate control groups. * p<0.05 vs. treatment with control media. n=9 for tube formation, n=12 for proliferation; error bars represent SEM.

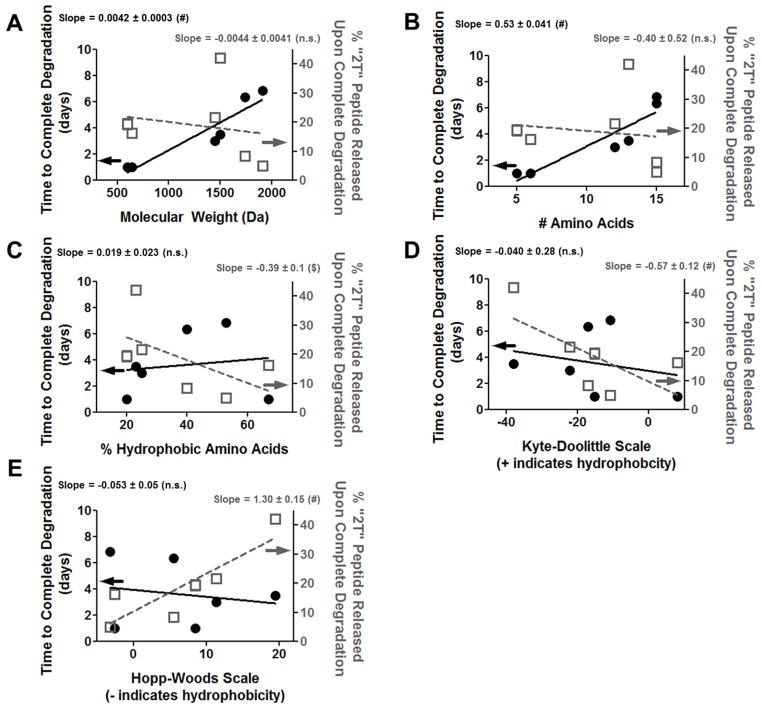

Figure 4.

Hydrogel characterization and degradation. (A) Bulk images, scale bar = 1 cm, (B) swelling ratios, (C) % peptide incorporated, and (D) % peptide not forming crosslinks. n.s. p>0.05, * p<0.05, & p<0.01, $ p<0.001. n=12; error bars represent SEM.

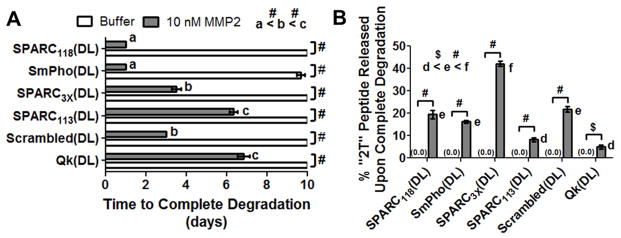

Figure 5.

Hydrogel degradation and peptide release. (A) Time to complete degradation (study ended at 10 days), and (B) amount of “2T” peptide released upon complete hydrogel degradation. a–f indicates groups that are statistically equivalent (p>0.05), $ p< 0.001, # p<0.0001. n=6; error bars represent SEM (some obscured by symbol).

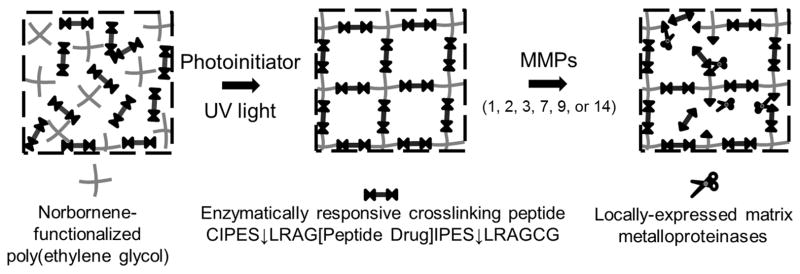

Figure 6.

Relationship between peptide (A) molecular weight, (B) sequence length, (C) percent hydrophobic amino acids, (D) Kyte-Doolittle scale, and (E) Hopp-Woods scale and hydrogel degradation (left axis, black circles and solid black line) and “2T” peptide release (right axis, open grey squares and dashed grey line). n.s. p>0.05, $ p<0.001, # p<0.0001. n=6; error bars represent SEM (some obscured by symbol).

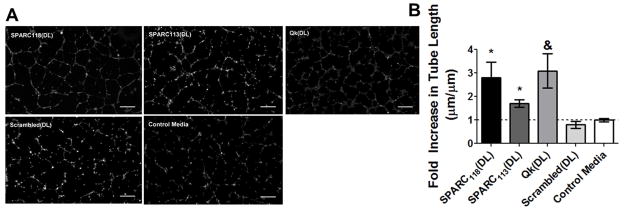

Figure 7.

(A) Representative images of and (B) fold increase in tube length over control media upon treatment with degraded peptide-releasing hydrogels. HUVECs were treated with ~1/7,000th of a degraded gel, corresponding to 100 nM of released SPARC118(2T). * p<0.05, & p<0.01 vs. treatment with control media. Scale bar = 250 um; n=9; error bars represent SEM.

3. Results

3.1. Effect of enzyme substrate residues (“tails”) on peptide bioactivity

Six a priori identified bioactive peptides (Table 1) were selected from literature to determine the effect of residual peptide “tails” remaining on peptides upon enzymatically-responsive hydrogel release. Bioactive peptide selection was restricted to pro-angiogenic peptides to allow for objective comparison of the impact of the “tails” on all peptides using well-established in vitro assays [25]. Peptides were chosen with a variety of sizes and hydrophobicity (Table 2) to investigate if these characteristics provided predictive power for the effect of “tails” on bioactivity. Peptides were synthesized both in their “native” (“N”) sequences, and in “two-tailed” (“2T”) forms (Table 1). The “2T” form mimics incorporation of the MMP2 degradable substrate, IPES↓LRAG, on both the N- and C- termini of the peptide drug for enzymatically-responsive hydrogel formation, and subsequent substrate cleavage and peptide release. Peptide bioactivities and the impact of “tails” were compared using two in vitro models of angiogenesis: the HUVEC tube formation and proliferation assays (Figure 2) [25]. For clarity, tube formation data is reported as fold-increase and proliferation data is reported as % increase, both normalized to control media.

Table 2.

Peptide characteristics. Hydrophobic amino acids are G, A, V, L, I, M, F, Y, W [43].

| Peptide | Molecular Weight (Da) | Sequence Length (# amino acids) | Hydropathy

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # Average (%) | K-D Score | H-W Score | |||

| SPARC118 | 597 | 5 | 20% | −15.3 | 8.5 |

| SmPho | 640 | 6 | 67% | 8.1 | −2.6 |

| KRX-725 | 1150 | 9 | 33% | −19.1 | 8.1 |

| Scrambled | 1449 | 12 | 25% | −22.2 | 11.4 |

| SPARC3X | 1498 | 13 | 23% | −38.4 | 19.5 |

| SPARC113 | 1740 | 15 | 40% | −17.2 | 5.5 |

| Qk | 1911 | 15 | 53% | −10.9 | −3.2 |

| Comb1 | 2543 | 25 | 44% | −13.7 | 14.3 |

| DL | 842 | 8 | 50% | −0.7 | 2.2 |

Average indicates number average, by amino acid type. In the Kyte-Doolittle (K-D) index, positive values indicate hydrophobicity [44]; in the Hopp-Woods (H-W) index, negative values indicate hydrophobicity [45]. Sequences were analyzed as the sequence alone, without any linker, “tails”, or C-terminal Gly amino acid used for synthesis.

All six “N” peptides significantly increased HUVEC tube length over control media; however, only three retained this bioactivity in “2T” forms, specifically Qk, SPARC113, and SPARC118 (Figure 2A). Qk(N) and Qk(2T) increased average tube length to 2.1 and 2.4-fold that of control media. SPARC118(N) and SPARC118(2T) increased tube length 2.0 and 1.8-fold, while SPARC113(N) and SPARC113(2T) increased tube length 1.3 and 1.7-fold. Comb1(N) significantly increased average tube length 1.5-fold, but Comb1(2T) did not significantly affect tube length (1.3-fold). SPARC3X was also inactivated by the “tails”, with the “N” form significantly increasing tube length 1.5-fold, and the “2T” form resulting in a statistically insignificant 0.4-fold increase. KRX-725(N) significantly increased tube length 1.2-fold, while KRX-725(2T) resulted in a statistically insignificant 1.1-fold increase. The scrambled peptide did not significantly affect relative tube length (0.9-fold), indicating that the observed results are due to specific peptide drugs.

A preliminary dose screening study (data not shown) did not identify a singular concentration at which all “N” peptides resulted in HUVEC proliferation. Therefore, the dose used to investigate the effect of the peptide “tails” on HUVEC proliferation was varied between peptide types, but kept constant between the “N” and “2T” forms of each peptide. All except for KRX-725 retained their “N” proliferative capacity upon inclusion of the “2T” (Figure 2B). Qk(N) and Qk(2T) at 100 nM both significantly increased HUVEC proliferation by 17%, SPARC113(N) and SPARC113(2T) at 1 nM significantly increased HUVEC proliferation by 12 and 18%, and SPARC3X(N) and SPARC3X(2T) at 100 nM significantly increased HUVEC proliferation by 11 and 14%. Comb1 at 100 nM increased proliferation by 21% in the “N” form and 14% in the “2T” form. SPARC118 at 1 nM exhibited similar behavior, with the “N” form increasing HUVEC proliferation by 28%, while the “2T” form increased proliferation 14%. KRX-725 completely lost bioactivity upon inclusion of the “2T”, with KRX-725(N) significantly increasing proliferation by 26%, and KRX-725(2T) decreasing proliferation 3% compared to control media, both at 1 nM. The scrambled peptide did not affect proliferation (3%), again indicating that the observed results are sequence-specific. Based on these results, three peptides were identified that retained bioactivities in released form from enzymatically-responsive hydrogels: Qk, SPARC113, and SPARC118.These peptides have varying sizes and hydrophobicities (Table 2), and no clear property was identified that could predict if peptides would remain bioactive with residual enzyme substrate “tails”. Similarly, peptide structure predictions were unable to provide insight as to which peptide retained or lost bioactivity (Supplemental Figure 1).

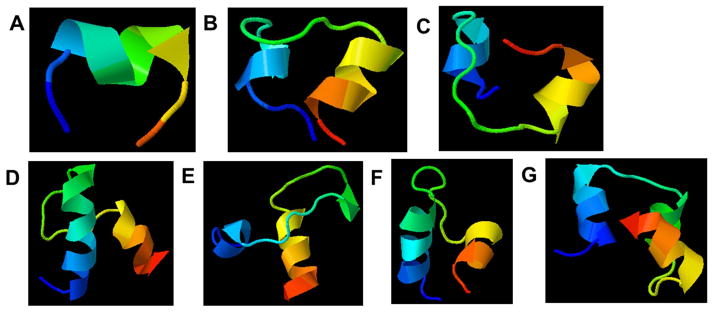

3.2. Prediction of crosslinking peptide structure

To investigate the versatility of the enzymatically-responsive peptide delivery system, release of six peptides were investigated. This included four of the previously-investigated pro- angiogenic peptide drugs: Qk, SPARC113, SPARC118, SPARC3X, as well as a scrambled control. These peptides represent a variety of peptide types, from small and hydrophilic (SPARC118) to large and very hydrophobic (Qk) (Table 2). As none of the peptides investigated in the bioactivity study were small and hydrophobic, a model peptide drug (SmPho) was also investigated. All six peptides were synthesized in the full enzymatically-responsive and crosslinkable forms (“DL” form, Table 1).

To further investigate differences in peptide properties, prediction software was used to investigate differences in peptide structure [34]. Figure 3 illustrates the predicted peptide structures for all six peptide-releasing sequences investigated, as well as the degradable linker IPES↓LRAG. The degradable linker was predicted to form an α-helix with ~ 1.5 turns, a structure maintained in all of the peptide-releasing sequences. Sequences designed to release large peptides (SPARC3X, SPARC113, Scrambled, and Qk) all exhibited increased number or length of α-helixes above those contributed by the “DL”s alone (Figure 3D–G), while the smaller peptides (SmPho and SPARC118) had either equal or reduced α-helix length (Figure 3B–C). The central region of Qk(DL) and SPARC113(DL) were predicted to have ~ 1.5 and ~ 0.5 turns, respectively. SPARC3X(DL) was predicted to have a longer, ~ 3.5-turn N-terminal α-helix, but no central α-helix. Scrambled(DL) similarly had an extended ~ 2.5 turn N-terminal α-helix, and both the N- and C- terminal α-helixes of Qk(DL) were extended to ~ 2.5 turns. SmPho(DL) and SPARC118(DL) were not predicted to have any additional α-helixes, and SPARC118(DL) had a slightly shorter N-termini α-helix. This structure prediction method has been validated against 37 linear peptides, and shown to deviate from NMR structures by only 3 Å [42]. Additionally, the predicted structure of the central peptide drug of Qk(DL) in particular is consistent with prior investigations of Qk that measured α-helix conformation using circular dichroism [48].

Figure 3.

Predicted structures for peptides (A) the degradable linker (DL) alone, (B) SPARC118(DL), (C) SmPho(DL), (D) SPARC3X(DL), (E) SPARC113(DL), and (F) Qk(DL). Arrowheads point to C-termini; color gradient also indicates directionality (blue = N-termini, red = C-termini). The reader is directed to the online version of this article for full color images.

3.3. Formation and characterization of enzymatically-responsive hydrogels

The Qk(DL) peptide initially designed (C IPES↓LRAG KLTWQELYQLKYKGI PES↓LRAG C G) was not sufficiently soluble in aqueous solution to allow for incorporation into PEG hydrogels. Therefore, the sequence was modified to enhance solubility by inclusion of four additional hydrophilic Glu (E) amino acids on both ends (Table 1). Even with these additional hydrophilic amino acids, the peptide required the use of a water/acetonitrile co-solvent to form hydrogels. All other (DL) peptides were soluble in buffer at the necessary concentrations for hydrogel formation.

Macroscopically, the Qk(DL) gels were somewhat opaque, while all other gels were transparent (Figure 4A). The hydrogels containing the smaller peptide drugs, SPARC118(DL) and SmPho(DL), appeared to have swollen to a greater extent and had significantly higher mass swelling ratios than the other four gels, specifically 27 and 28 mg/mg, as compared to 15, 16, 13 and 15 mg/mg for the SPARC3X(DL), SPARC113(DL), Scrambled(DL), and Qk(DL) gels, respectively (Figure 4B). While there were significant differences in peptide incorporation between the gels, all had nearly complete incorporation of the crosslinking peptide (97% or greater, Figure 4C). Additionally, only the Qk(DL) gels had any detectable amount of peptide incorporated into the gel not actively forming crosslinks, with 9% of the incorporated peptide retaining a free thiol (Figure 4D).

3.4. Degradation and “2T” peptide release from enzymatically-responsive hydrogels

The SmPho(DL) gels degraded when incubated in the buffer alone (9.7 days), with all other gels remaining intact over the course of the degradation study (10 days, Figure 5A). Qualitative decreases in stiffness of only SPARC118(DL) and SmPho(DL) gels in buffer were observed, while all other gels were stable over this timeframe. All six gel types fully degraded in the presence of 10 nM MMP2, and all degraded significantly faster than in buffer (Figure 5A). In the presence of MMP2, the SPARC118(DL) and SmPho(DL) gels degraded the fastest, in 1 day, followed by the Scrambled(DL) and SPARC3X(DL) gels which degraded in 3 and 3.5 days, respectively. The SPARC113(DL) and Qk(DL) gels degraded the slowest, over 6 and 6.7 days, respectively. All gel types released undetectable amounts of “2T” peptide in buffer alone, and all released significantly more “2T” peptide in MMP2 containing buffer (Figure 5B), demonstrating the enzymatically-responsive nature of these gels. Upon reaching the reverse gelation point, the Qk(DL), SPARC113(DL), SmPho(DL), SPARC118(DL), Scrambled(DL) and SPARC3X(DL) gels released 5, 8, 16, 19, 22, and 42% of peptide in its “2T” form, respectively. Tracking of “2T” peptides in solution over time demonstrated all peptides remain stable in both buffer and MMP-containing buffer (Supplemental Figure 2), indicating differences in “2T” peptide release are not due to further degradation of released peptides. Mass spectrometry on degraded SPARC118(DL), SmPho(DL), SPARC3X(DL), SPARC113(DL), and Scrambled(DL) hydrogels showed singular peaks at the expected “2T” peptide molecular weight, further confirming that the MMP is cleaving the peptides at the expected sites and that peptides are not nonspecifically degraded upon release from the hydrogels (Supplemental Figure 3).

3.5. Relationship between peptide drug properties and enzymatically responsive hydrogel behaviors

To determine if any relationship existed between peptide drug properties and behavior of enzymatically-responsive hydrogels, time to complete hydrogel degradation and amount of “2T” peptide release upon degradation were plotted as a function of various measures of peptide size and hydrophobicity. As shown in Figure 6, two measures of peptide size, molecular weight and sequence length, exhibited a significant linear relationship with the rate of hydrogel degradation, but not with the amount of “2T” peptide released from hydrogels. Three measurements of peptide hydrophobicity, % hydrophobic amino acids, Kyte-Doolittle scale, and Hopp-Woods scale, exhibited linear relationships with the amount of “2T” peptide released from hydrogels, but none had a significant linear relationship with time to complete hydrogel degradation. Differences in units between the peptide characteristics investigated (Da, #, %, etc.) prevented any meaningful comparison between the slopes of the linear fits obtained.

3.6. In vitro efficacy of degraded hydrogels

The enzymatically-responsive gels releasing peptides found to be bioactive in their “2T” form, SPARC118(DL), SPARC113(DL), and Qk(DL), as well as the scrambled peptide releasing gel Scrambled(DL) were degraded with MMP2. Subsequently, the HUVEC tube formation assay was used to assess the pro-angiogenic potential of degraded hydrogel products and released peptide drugs. Filtered, degraded hydrogel solutions were diluted in media and assessed for bioactivity using the tube formation assay such that the concentration of SPARC118(2T) present was 100 nM, the concentration utilized in the efficacy screening study (section 3.1), equating to ~ 1/7,000th gel/well. The gel/well ratio was kept constant across all hydrogels investigated, but variations in the amount of “2T” peptide present in the degraded hydrogel solutions caused variation in the amount of “2T” peptide present (4.5 nM Qk(2T), 130 nM SPARC113(2T) and 240 nM Scrambled(2T)). Degraded SPARC118(DL), SPARC113(DL) and Qk(DL) hydrogels significantly increased HUVEC tube formation to 2.8, 1.7 and 3.1-fold that of control media (Figure 7). The degraded Scrambled(DL) gels did not significantly affect tube length (0.8-fold) indicating that the observed results are due to specific peptide drugs released from the hydrogels.

4. Discussion

This study details the development of a platform technology for the stimuli-responsive delivery of peptide drugs from hydrogels. The effect of residual peptide “tails” left on peptide drugs upon release from enzymatically-responsive hydrogels on the bioactivity of six peptides was investigated. While three peptides were identified that retained bioactivity in released forms, no physical peptide property was identified that predicted which peptide would retain bioactivity. Nonetheless, peptide release from enzymatically-degradable hydrogels was achieved through the use of MMP-substrate crosslinkers. Testing revealed the impact of the peptide drug on hydrogel degradation and peptide release; peptide drug size was found to affect hydrogel swelling and rate of hydrolytic and enzymatic degradation, while hydrophobicity affected the extent of peptide fully released in its “2T” form. Upon MMP-mediated degradation, degraded peptide-releasing hydrogels were able to induce HUVEC tube formation, indicating these hydrogels release bioactive components upon degradation.

Therapeutic peptides are often delivered via injection [13, 14], osmotic pumps [2], or diffusional release from polymeric particles [7, 15] or gels [2, 16, 17]. However, many of these approaches do not offer controlled, sustained release of therapeutic peptides, and delivery occurs over pre-dictated timescales and not in response to microenvironmental cues. Previous work has shown superiority of tissue-dictated release of drugs. For example, persistent vascularization of hydrogels in vivo was attributed to tissue-responsive cleavage of VEGF resulting in sustained release, in contrast to the burst release typical of diffusion-controlled drug release systems or bolus delivery [18]. While enzymatically-responsive growth factor release has shown promising results [18, 49], delivery of peptide drugs in this manner has not been demonstrated [12]. The enzymatically-responsive material presented here is designed to deliver peptide drugs in a sustained and tissue-dependent manner, as the MMPs to which the substrate is susceptible are expressed at increased levels in ischemic [27, 28] and inflamed tissues [31, 32], and in tumor microenvironments [29, 30]. These hydrogels are a promising candidate for minimally-invasive treatment as they can be polymerized in situ using cytocompatible UV light [21]. Additionally, degradation circumvents secondary surgeries necessary to remove non-degradable drug delivery depots.

The impact of residual enzyme substrate “tails” on the efficacy of six a priori identified pro-angiogenic peptide sequences was investigated. Some peptides (Qk, SPARC113 and SPARC118) were unaffected by the presence of residual amino acid residues, with “2T” results very similar to “N” results (Figure 2). Others exhibited decreased (SPARC3X and Comb1) or entirely lost (KRX-725) ability to induce HUVEC proliferation and tube formation in their “2T” form. Some peptides only lost bioactivity in one of the two assays (Comb1 and SPARC3X); however, differential effects between these outcomes is not unprecedented, as proliferation and tube formation are different cell processes [14, 35]. In addition to identifying three peptides likely to be bioactive after release from enzymatically-responsive hydrogels (Qk, SPARC113, and SPARC118), these data demonstrate a limitation of the enzymatically-responsive delivery system developed. The same peptide “tails” have very different impacts on peptide bioactivity, and neither size, hydrophobicity, nor structure could be used to predict which peptides retain bioactivity (Figure 2, Table 2, Supplemental Figure 1). However, it is possible that additional analyses could identify peptide properties not investigated here (basicity, acidity, etc) that are predictive of bioactivity. These findings are consistent with previous work that demonstrates that residual amino acid residues and drug properties can affect bioactivity. For example, VEGF containing a PEG linker retains similar bioactivity to the native protein [49]. However, PEG is a hydrophilic, unstructured molecule with few similarities to polypeptide chains. Similar to our approach, though, by altering the cleavable peptide spacer conjugating the chemotherapeutic Mitomycin C to a polymeric carrier, the rate of drug release and the off-target hematopoietic toxicity of the released drug is affected [50]. Additionally, the N- versus C- terminal position of peptide “tails” strongly affects bioactivity of CD95L fusion proteins [51]. These prior results, along with our findings, indicate that the therapeutic agent being used and the chemical composition and position of residual “tails” can impact therapeutic agent bioactivity upon release. These data also suggest the possibility of restoring bioactivity of peptide drugs inactivated by “tails” simply by changing the amino acid residues of the linker or incorporating amino acids spaces prior to the degradable substrate [26].

The three promising pro-angiogenic peptide drugs Qk, SPARC113, SPARC118, as well as SPARC3X, the scrambled peptide, and the model peptide drug SmPho, were incorporated into enzymatically-responsive hydrogels. The large, hydrophobic crosslinking peptide Qk produced opaque gels, while all other gels were transparent (Figure 4A), as is typical for PEG hydrogels. This is likely a result of increased intermolecular interactions of the Qk α-helices (Figure 3G), and is consistent with previous findings showing that α-helix containing peptides self-assemble into opaque hydrogels [52]. The swelling ratio of gels is inversely related to sequence length, with smaller peptides (SPARC118 and SmPho) having larger swelling ratios than gels formed with larger peptides (Qk, SPARC113, Scrambled, and SPARC3X, Figure 4B). As larger crosslinking peptides make up higher weight percentages of hydrogel dry masses (48% for Qk(DL) gels, compared to 23% for SPARC118(DL) gels), intermolecular interactions between crosslinking peptides are more probable. It is also possible that the increased number and length of α-helices found within the larger peptides (Figure 3) increases non-covalent intermolecular peptide interactions within these hydrogels, effectively increasing the crosslinking density of the gels. The lower crosslinking efficiency in Qk(DL) hydrogel properties could be due to the peptide structure and hydrophobicity decreasing cysteine availability, or to the evaporation of acetonitrile co-solvent during polymerization, which effectively increases peptide crowding, leading to less efficient crosslinking. Taken together, these results demonstrate the impact the size of the crosslinking peptide can have on hydrogel physical properties.

The incorporation of reactive enzymatically-responsive tethers IPES↓LRAG into pro-angiogenic peptides resulted in hydrogels that were degraded by MMP2. Previous work using IPES↓LRAG directly as a hydrogel crosslinker results in PEG hydrogels that degrade in 2 days in MMP2, but are stable for over 10 days in MMP1 [23]. Degradation over similar timescales was expected in this work as the previously studied “DL” gels were smaller, had a lower crosslinking density, and used a higher concentration of MMP2, but only had one “DL” per crosslink. All five gels exhibited enzymatically-responsive degradation and peptide release, as demonstrated by accelerated degradation and release of “2T” peptide only in the presence of MMP2 (Figure 5). As the same degradable substrates were used for every peptide investigated, it was expected that all hydrogels would degrade at similar rates and release similar amounts of “2T” peptide. However, testing revealed that peptide drug has a significant effect on both behaviors. Further investigation revealed that the rate of enzymatically-responsive hydrogel degradation is related to peptide drug size, while “2T” peptide release is related to peptide drug hydrophobicity (Figure 6). Numerous other studies have varied the rate of enzymatically-responsive hydrogel degradation by altering the degradable sequence employed, particularly the ~ 4 amino acids immediately adjacent to the cleavage site [21, 23, 53]; to our knowledge no study has investigated the role of linker-adjacent peptides in hydrogel degradation and peptide release. Vessillier et al. found that addition of hydrophilic amino acids flanking a peptide cleavage substrate increases substrate sensitivity [54], but the contributions of hydrophilicity and size of the flanking sequences were not specifically isolated. The decreased substrate cleavage and “2T” release of Qk from the developed system may have been affected by the additional glutamic acid residues included to improve solubility. As MMP activity requires a zinc-bound water molecule activated for nucleophilic attack, and glutamic acid residues shuttle protons and allow for peptide bond cleavage [55], it is possible that modifying the MMP substrate with additional glutamic acids for improved solubility may have also affected proton transfer. Introduction of alternative hydrophilic amino acids and/or hydrophilic linkers may allow for additional Qk(2T) release. With the potential for the rate of degradation and release being affected by glutamic acid residues notwithstanding, Qk-based hydrogels are observed to degrade in an MMP2-dependent manner.

By incorporating the therapeutic molecule as the crosslinking agent of the enzymatically-responsive hydrogels, higher concentrations of peptide can be loaded into gels. However, this also inherently links peptide release to hydrogel degradation. To achieve hydrogel degradation in this system, peptide crosslinkers need only to be cleaved at one “DL” site. However, both “DL” sites need to be cleaved for “2T” peptide release (Figure 1). It is likely that crosslinking peptide not detected in “2T” forms after hydrogel degradation remained tethered to PEG molecules, rather than being further degraded upon release. This is supported by the stability of all “2T” peptides in both buffer and MMP2 (Supplemental Figure 2), and the single peak observed in the mass spectrometry of degraded hydrogels (Supplemental Figure 3). As hydrogel degradation is predicted by peptide size (Figure 6), it can be inferred that the size of the peptide drug affects the rate of cleavage of one “DL”. The SPARC3X peptide, which is 3 repeats of the SPARC118 peptide, directly highlights the impact of peptide drug size on degradation. Whereas hydrogels formed with SPARC118 degraded in 1 day in the presence of MMP2, SPARC3x-releasing hydrogels required 3.5 days to reach the reverse gelation point (Figure 5). The mesh size of these gels varied from 30 ± 4 nm (Qk(DL)) to 63 ± 2 nm (SmPho(DL)) [56], but there should be minimal hindrance to diffusion of MMP2 (~ 2.6 nm) within all gels [57], indicating that the observed differences in degradation rate are not due to diffusional limitations. Additionally, the hydrolytic degradation observed for the SPARC118(DL) and SmPho(DL) gels is likely a minor contributor to accelerated enzymatic degradation, as there is a substantial difference in timescales (1 versus 10 days) of hydrolytic and enzymatic degradation for SmPho(DL) gels. Similar to previous reports, these hydrogels hydrolytically degraded due to the presence of ester bonds between PEG and norbornene groups [58, 59]. Future studies could employ an alternate chemistry for norbornene functionalization of PEG where esters are replaced with amide bonds, significantly reducing the rate of hydrolytic degradation [58]. Hydrophobicity is strongly related with “2T” release (Figure 6), implying that once the first “DL” is cleaved, hydrophobic peptides decrease the cleavage rate of the second “DL”. Differences in peptide structure may also impact the rate of “DL” cleavage, as the more slowly degrading gels have a larger proportion of α-helices (Figure 3). While the degradation and “2T” release data provides interesting information on how the peptide drug affects the relative rates of “DL” cleavage, it is unable to elucidate any difference in cleavage rate or order between the N- and C- terminal “DL”, or if the differences in cleavage rate are due to changes in cleavage site accessibility or substrate cleavage kinetics.

The degradation and release data here provide valuable insight for development of similar enzymatically-controlled peptide release systems: large, hydrophilic peptide drugs are predicted to produce gels that slowly degrade and fully release a large fraction of the peptide, while small, hydrophobic peptide drugs are expected to produce gels that degrade rapidly and release only a modest amount of peptide drug. As linear relationships were found between two measures of peptide size (molecular weight and sequence length) and hydrogel degradation, and between three measures of peptide hydrophobicity (% hydrophobic amino acids, Kyte-Doolittle scale, and Hopp-Woods scale) and “2T” peptide release, it is likely these underlying peptide drug characteristics control hydrogel behavior. Only a single substrate/enzyme pair was investigated here, and it is possible that these trends will not translate to all enzyme/substrate systems. For example, alteration of two different MMP-degradable substrates (substrate vs. NS-substrate-STSAGPTV) increases the rate of MMP3-mediated cleavage of the degradable sequence GPLGLWAQ 3-fold, while increasing the rate of cleavage of degradable substrate GVPDVGHFSLFP 29-fold. However, the MMP1-mediated cleavage of both substrates is unaffected by the addition of the hydrophilic sequence [54]. This underlies the interplay between enzyme, degradable linker, and linker-adjacent modifications in affecting substrate cleavage kinetics.

Despite various amounts of peptide released in “2T” form, all three peptide drug releasing hydrogels significantly increased HUVEC tube formation. Degraded SPARC118(DL) and SPARC113(DL) hydrogels significantly increased HUVEC tube length 2.8 and 1.7-fold, demonstrating that these hydrogels release bioactive components upon MMP mediated degradation. The degraded Qk(DL) gels significantly increased HUVEC tube length 3.1-fold control media, despite releasing substantially less peptide in “2T” form than the SPARC118(DL) and SPARC113(DL) hydrogels. Indeed, degraded Qk(DL) hydrogels induced tube formation at lower “2T” levels (4.5 nM) than those previously investigated in the screening study (100 nM). However, the 100 nM dose previously used was not verified to be the minimum effective dose, and it is possible that “2T” peptide alone is also able to induce tube formation at this lower concentration. Additionally, as PEG is bio-inert, it is possible that peptides released from the hydrogel in PEG-tethered forms retain their bioactivity [49]. However, additional studies would be required to separate the contributions of peptide fully released from the hydrogel in “2T” form from those of peptide still tethered to a PEG molecule. Nevertheless, this study demonstrates that the SPARC118(DL), SPARC113(DL), and Qk(DL) hydrogels release bioactive components upon MMP-mediated degradation.

A critical consideration for responsive delivery systems is therapeutic impact. The hydrogels investigated here contain ~ 0.8 μmol peptide per 40 μL gel. Omitting temporal considerations, with the 19% “2T” release achieved for SPARC118(DL) gels and in vitro efficacy obtained at 100 nM, one gel should release enough “2T” drug to reach target concentrations in ~ 1.5 L of tissue. The decreased “2T” release from the Qk(DL) gels means these gels only release enough “2T” drug to reach 100 nM in ~ 0.4 L of tissue. Despite differences in “2T” peptide release, SPARC118(DL), SPARC113(DL), and Qk(DL) gels were all able to induce tube formation at the same gel dilution ratios. This indicates that the all three gels should be able to reach therapeutic levels in similar volumes of target tissue. Only one concentration of degraded gel was assessed for in vitro bioactivity, and it is possible that the enzymatically-responsive gels developed here are bioactive at even lower concentrations and could achieve therapeutically relevant concentrations in even larger volumes of tissue.

A further consideration is the timescale over which the gels release peptide drug. Smaller peptide drugs resulted in hydrogel degradation over 1 day, while gels releasing larger peptide drugs degraded in approximately 1 week (Figure 5). While indicative of enzymatic-responsiveness, this is not expected to be predictive of degradation timescales in vivo, as supra-physiological concentrations of MMP2 were used [60]. Additionally, the presence of other MMPs in an in vivo environment [27–32] will likely alter the rate of hydrogel degradation and peptide release. Degradation timescales could be altered by adjusting hydrogel crosslinking density [61]. Degradation time could also be altered by changing the specific degradable substrate used [23, 26]; however, this would also alter the “tails” left on the peptide, likely affecting bioactivity based on the results previously discussed.

The peptide drugs investigated here were restricted to pro-angiogenic peptides; however, controlled release of any therapeutic peptide is feasible, including anti-inflammatory [3, 4] and chemotherapeutic [5, 6] peptides. Additionally, while therapeutic peptides were the exclusive focus of this study, controlled release of any therapeutic agent whose chemical composition allows them to be flanked by MMP-degradable substrates is also theoretically possible [62, 63]. This approach also has promise for use in cell-based tissue engineering approaches; for example, the peptide SPARC118 was recently described to increase mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) production of pro-angiogenic factors [64], suggesting the possibility to enhance the therapeutic effect of transplanted or host MSCs [65] using SPARC118(DL) hydrogels. Additionally, release of multiple peptide drugs could be achieved by using a mixture of crosslinking peptides during gel formation or, as illustrated here, differences in temporal release among peptide drugs could be exploited to deliver two drugs over different timeframes. For example, sequential delivery of pro-angiogenic and pro-maturation growth factors improves vessel formation and stability in vivo [66]. However, as the peptide drug delivered affects the rate of hydrogel degradation and peptide release, achieving well-controlled sequential release of multiple factors is non-trivial. Altogether, these results demonstrate the development of a novel method for enzymatically-responsive delivery of peptide drugs, with potential application in a variety of disease states and tissue engineering applications.

5. Conclusions

With the goal of developing a hydrogel-based platform technology for enzymatically-responsive delivery of peptide drugs, this study compared the relative in vitro efficacies of six pro-angiogenic peptides and the impact residual peptide “tails” had on peptide bioactivity. SPARC118, SPARC113, and Qk were found to retain their bioactivity in their released form, but no clear peptide property was identified to a priori predict which peptides retain bioactivity in the released form. Six peptides with varying properties were incorporated into PEG hydrogels via the enzymatically-responsive linker IPES↓LRAG, achieving enzymatically-responsive hydrogel degradation and peptide release. Linear regression analysis indicated peptide drug size controls the rate of hydrogel degradation, while peptide drug hydrophobicity affects the amount of peptide fully released from the PEG macromers. In vitro testing of degraded SPARC118(DL), SPARC113(DL), and Qk(DL) hydrogels demonstrated that enzymatically-responsive hydrogels release bioactive constituents upon MMP-mediated degradation. This represents a novel method to controllably deliver peptide drugs in an enzymatically-responsive manner, with potential applications to aid in development of tissue engineered constructs, or for the treatment of ischemia, chronic inflammation, or cancer.

Supplementary Material

Predicted structures for various “N” and “2T” peptides. Comparing peptides that lost (KRX-725 and SPARC3X) and retained (SPARC113 and Qk) bioactivity upon inclusion of the “2T”, no clear change in structure between “N” and “2T” form was observed. Arrowheads point to C-termini; color gradient also indicates directionality (blue = N-termini, red = C-termini).

Demonstration of released peptide stability. 0.8 μmol of “2T” peptide in 1 mL buffer or buffer containing 10 nM MMP2 was incubated at 37 ºC, and the amount of peptide remaining in its “2T” form tracked over time using HPLC. (A) SPARC118(2T), (B) SmPho(2T), (C) SPARC3X(2T), (D) SPARC113(2T), (E) Scrambled(2T), and (F) Qk(2T). The peptides remained stable in both solutions, indicating that peptides are not degraded after release from the hydrogel network. n=1.

MALDI-ToF mass spectrometry analysis of degraded hydrogels. (A) SPARC118(DL), (B) SmPho(DL), (C) SPARC3X(DL), (D) SPARC113(DL), (E) Scrambled(DL) and (F) buffer alone. SPARC118(DL) gels were degraded in Brij-free buffer for mass spectrometry, as the Brij signal obscured the “2T” form of the peptide. All degraded gels have a clear single peak at the expected “2T” peptide molecular weight, indicating peptides are not being further cleaved by MMP2 after release from the hydrogel networks. An increase of 1 or 2 Da indicates the released peptide is protonated. No clear spectra could be obtained for degraded Qk(DL) gels.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the National Institute of Health (R01 AR064200) and a Howard Hughes Medical Institute Med-into-Grad fellowship (AVH). The authors would like to thank Dr. James L. McGrath (University of Rochester, Department of Biomedical Engineering) and Dr. Alex Shestopalov (University of Rochester, Department of Chemical Engineering) for the use of their equipment, Dr. Stephen Dewhurst (University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry, Department of Microbiology and Immunology) for HUVECs, Dr. Jharon Silva for his advice on HUVEC culture, and Dr. Jinjiang Pang for helpful discussions about the tube formation assay.

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST:

All authors state that they have no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Amy H. Van Hove, Email: amy.h.vanhove@rochester.edu.

Michael-John Beltejar, Email: michael-john_beltejar@urmc.rochester.edu.

Danielle S. W. Benoit, Email: benoit@bme.rochester.edu.

References

- 1.Finetti F, Basile A, Capasso D, Di Gaetano S, Di Stasi R, Pascale M, et al. Functional and pharmacological characterization of a VEGF mimetic peptide on reparative angiogenesis. Biochem Pharm. 2012 Aug 1;84(3):303–11. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2012.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Santulli G, Ciccarelli M, Palumbo G, Campanile A, Galasso G, Ziaco B, et al. In vivo properties of the proangiogenic peptide QK. J of Trans Med. 2009;7:41. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-7-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Akeson AL, Woods CW, Hsieh LC, Bohnke RA, Ackermann BL, Chan KY, et al. AF12198, a novel low molecular weight antagonist, selectively binds the human type I interleukin (IL)-1 receptor and blocks in vivo responses to IL-1. J Biol Chem. 1996 Nov 29;271(48):30517–23. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.48.30517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schultz P, Vautier D, Richert L, Jessel N, Haikel Y, Schaaf P, et al. Polyelectrolyte multilayers functionalized by a synthetic analogue of an anti-inflammatory peptide, alpha-MSH, for coating a tracheal prosthesis. Biomaterials. 2005 May;26(15):2621–30. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.06.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang LL, Mashima T, Sato S, Mochizuki M, Sakamoto H, Yamori T, et al. Predominant suppression of apoptosome by inhibitor of apoptosis protein in non-small cell lung cancer H460 cells: Therapeutic effect of a novel polyarginine-conjugated Smac peptide. Cancer Res. 2003 Feb 15;63(4):831–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Selivanova G, Iotsova V, Okan I, Fritsche M, Strom M, Groner B, et al. Restoration of the growth suppression function of mutant p53 by a synthetic peptide derived from the p53 C-terminal domain. Nat Med. 1997 Jun;3(6):632–8. doi: 10.1038/nm0697-632. Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ben-Sasson SA, Licht T, Tsirulnikov L, Reuveni H, Yarnitzky T. Induction of pro-angiogenic signaling by a synthetic peptide derived from the second intracellular loop of S1P(3) (EDG3) Blood. 2003 Sep 15;102(6):2099–107. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-12-3634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Craik DJ, Fairlie DP, Liras S, Price D. The Future of Peptide-based Drugs. Chem Biol Drug Des. 2013 Jan;81(1):136–47. doi: 10.1111/cbdd.12055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Camelo S, Lajavardi L, Bochot A, Goldenberg B, Naud MC, Fattal E, et al. Ocular and systemic bio-distribution of rhodamine-conjugated liposomes loaded with VIP injected into the vitreous of Lewis rats. Mol Vis. 2007 Dec 7;13(256):2263–74. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aguado MT, Lambert PH. Controlled-Release Vaccines - Biodegradable Polylactide Polyglycolide (Pl/Pg) Microspheres as Antigen Vehicles. Immunobiology. 1992 Feb;184(2–3):113–25. doi: 10.1016/S0171-2985(11)80470-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim JH, Kim YS, Park K, Kang E, Lee S, Nam HY, et al. Self-assembled glycol chitosan nanoparticles for the sustained and prolonged delivery of antiangiogenic small peptide drugs in cancer therapy. Biomaterials. 2008 Apr;29(12):1920–30. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.12.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Du AW, Stenzel MH. Drug Carriers for the Delivery of Therapeutic Peptides. Biomacromolecules. 2014 Apr;15(4):1097–114. doi: 10.1021/bm500169p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hardy B, Battler A, Weiss C, Kudasi O, Raiter A. Therapeutic angiogenesis of mouse hind limb ischemia by novel peptide activating GRP78 receptor on endothelial cells. Biochem Pharm. 2008 Feb 15;75(4):891–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2007.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hardy B, Raiter A, Weiss C, Kaplan B, Tenenbaum A, Battler A. Angiogenesis induced by novel peptides selected from a phage display library by screening human vascular endothelial cells under different physiological conditions. Peptides. 2007 Mar;28(3):691–701. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2006.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Failla CM, Soro S, Orecchia A, Morbidelli L, Lacal PM, Morea V, et al. A proangiogenic peptide derived from vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-1 acts through alpha 5 beta 1 integrin. Blood. 2008 Apr 1;111(7):3479–88. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-03-077537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Choi S, Baudys M, Kim SW. Control of blood glucose by novel GLP-1 delivery using biodegradable triblock copolymer of PLGA-PEG-PLGA in type 2 diabetic rats. Pharm Res. 2004 May;21(5):827–31. doi: 10.1023/b:pham.0000026435.27086.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Van Slyke P, Alami J, Martin D, Kuliszewski M, Leong-Poi H, Sefton MV, et al. Acceleration of Diabetic Wound Healing by an Angiopoietin Peptide Mimetic. Tissue Eng Pt A. 2009 Jun;15(6):1269–80. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2007.0400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Phelps EA, Landazuri N, Thule PM, Taylor WR, Garcia AJ. Bioartificial matrices for therapeutic vascularization. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010 Feb 23;107(8):3323–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905447107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Slaughter BV, Khurshid SS, Fisher OZ, Khademhosseini A, Peppas NA. Hydrogels in Regenerative Medicine. Adv Mater. 2009 Sep 4;21(32–33):3307–29. doi: 10.1002/adma.200802106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lin CC, Anseth KS. PEG Hydrogels for the Controlled Release of Biomolecules in Regenerative Medicine. Pharm Res. 2009 Mar;26(3):631–43. doi: 10.1007/s11095-008-9801-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fairbanks BD, Schwartz MP, Halevi AE, Nuttelman CR, Bowman CN, Anseth KS. A Versatile Synthetic Extracellular Matrix Mimic via Thiol-Norbornene Photopolymerization. Adv Mater. 2009 Dec 28;21(48):5005–10. doi: 10.1002/adma.200901808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lin CC, Raza A, Shih H. PEG hydrogels formed by thiol-ene photo-click chemistry and their effect on the formation and recovery of insulin-secreting cell spheroids. Biomaterials. 2011 Dec;32(36):9685–95. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.08.083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Patterson J, Hubbell JA. Enhanced proteolytic degradation of molecularly engineered PEG hydrogels in response to MMP-1 and MMP-2. Biomaterials. 2010 Oct;31(30):7836–45. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.06.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Salinas CN, Anseth KS. The enhancement of chondrogenic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells by enzymatically regulated RGD functionalities. Biomaterials. 2008 May;29(15):2370–7. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.01.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Auerbach R, Lewis R, Shinners B, Kubai L, Akhtar N. Angiogenesis assays: A critical overview. Clin Chem. 2003 Jan;49(1):32–40. doi: 10.1373/49.1.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cantley LC, Turk BE, Huang LL, Piro ET. Determination of protease cleavage site motifs using mixture-based oriented peptide libraries. Nat Biotechnol. 2001 Jul;19(7):661–7. doi: 10.1038/90273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Muhs BE, Plitas G, Delgado Y, Ianus I, Shaw JP, Adelman MA, et al. Temporal expression and activation of matrix metalloproteinases-2,-9, and membrane type 1 - Matrix metalloproteinase following acute hindlimb ischemia. J Surg Res. 2003 May 1;111(1):8–15. doi: 10.1016/s0022-4804(02)00034-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Phatharajaree W, Phrommintikul A, Chattipakorn N. Matrix metalloproteinases and myocardial infarction. Can J Cardiol. 2007 Jun;23(9):727–33. doi: 10.1016/s0828-282x(07)70818-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kurahara S, Shinohara M, Ikebe T, Nakamura S, Beppu M, Hiraki A, et al. Expression of MMPs, MT-MMP, and TIMPs in squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity: Correlations with tumor invasion and metastasis. Head Neck-J Sci Spec. 1999 Oct;21(7):627–38. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0347(199910)21:7<627::aid-hed7>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Heppner KJ, Matrisian LM, Jensen RA, Rodgers WH. Expression of most matrix metalloproteinase family members in breast cancer represents a tumor-induced host response. Am J Pathol. 1996 Jul;149(1):273–82. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lawrance IC, Fiocchi C, Chakravarti S. Ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease: distinctive gene expression profiles and novel susceptibility candidate genes. Hum Mol Genet. 2001 Mar 1;10(5):445–56. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.5.445. Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Konttinen YT, Ainola M, Valleala H, Ma J, Ida H, Mandelin J, et al. Analysis of 16 different matrix metalloproteinases (MMP-1 to MMP-20) in the synovial membrane: different profiles in trauma and rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1999 Nov;58(11):691–7. doi: 10.1136/ard.58.11.691. Comparative Study. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jendraschak E, Sage EH. Regulation of angiogenesis by SPARC and angiostatin: implications for tumor cell biology. Semin Cancer Bio. 1996 Jun;7(3):139–46. doi: 10.1006/scbi.1996.0019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Iruelaarispe ML, Lane TF, Redmond D, Reilly M, Bolender RP, Kavanagh TJ, et al. Expression of Sparc during Development of the Chicken Chorioallantoic Membrane - Evidence for Regulated Proteolysis in-Vivo. Mol Biol Cell. 1995 Mar;6(3):327–43. doi: 10.1091/mbc.6.3.327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Demidova-Rice TN, Geevarghese A, Herman IM. Bioactive peptides derived from vascular endothelial cell extracellular matrices promote microvascular morphogenesis and wound healing in vitro. Wound Repair Regen. 2011 Jan-Feb;19(1):59–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2010.00642.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Anthis NJ, Clore GM. Sequence-specific determination of protein and peptide concentrations by absorbance at 205 nm. Protein Sci. 2013 Jun;22(6):851–8. doi: 10.1002/pro.2253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Arnaoutova I, Kleinman HK. In vitro angiogenesis: endothelial cell tube formation on gelled basement membrane extract. Nat Protoc. 2010;5(4):628–35. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2010.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Niemisto A, Dunmire V, Yli-Harja O, Zhang W, Shmulevich I. Robust quantification of in vitro angiogenesis through image analysis. Ieee T Med Imaging. 2005 Apr;24(4):549–53. doi: 10.1109/tmi.2004.837339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ryan JA. Corning guide for identifying and correcting common cell growth problems. Corning Incorporated Life Sciences; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Silva EA, Mooney DJ. Effects of VEGF temporal and spatial presentation on angiogenesis. Biomaterials. 2010 Feb;31(6):1235–41. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.10.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Asakage M, Tsuno NH, Kitayama J, Tsuchiya T, Yoneyama S, Yamada J, et al. Sulforaphane induces inhibition of human umbilical vein endothelial cells proliferation by apoptosis. Angiogenesis. 2006;9(2):83–91. doi: 10.1007/s10456-006-9034-0. Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Thevenet P, Shen YM, Maupetit J, Guyon F, Derreumaux P, Tuffery P. PEP-FOLD: an updated de novo structure prediction server for both linear and disulfide bonded cyclic peptides. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012 Jul;40(W1):W288–W93. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lehninger AL, Nelson DL, Cox MM. Lehninger principles of biochemistry. 3. New York: Worth Publishers; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kyte J, Doolittle RF. A Simple Method for Displaying the Hydropathic Character of a Protein. J Mol Biol. 1982;157(1):105–32. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(82)90515-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hopp TP, Woods KR. Prediction of Protein Antigenic Determinants from Amino-Acid-Sequences. P Natl Acad Sci-Biol. 1981;78(6):3824–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.6.3824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fairbanks BD, Schwartz MP, Bowman CN, Anseth KS. Photoinitiated polymerization of PEG-diacrylate with lithium phenyl-2,4,6-trimethylbenzoylphosphinate: polymerization rate and cytocompatibility. Biomaterials. 2009 Dec;30(35):6702–7. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.08.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ellman GL. Tissue Sulfhydryl Groups. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1959;82(1):70–7. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(59)90090-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.D'Andrea LD, Iaccarino G, Fattorusso R, Sorriento D, Carannante C, Capasso D, et al. Targeting angiogenesis: structural characterization and biological properties of a de novo engineered VEGF mimicking peptide. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005 Oct 4;102(40):14215–20. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505047102. Comparative Study Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zisch AH, Lutolf MP, Ehrbar M, Raeber GP, Rizzi SC, Davies N, et al. Cell-demanded release of VEGF from synthetic, biointeractive cell-ingrowth matrices for vascularized tissue growth. Faseb J. 2003 Oct;17(13):2260. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-1041fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Soyez H, Schacht E, Jelinkova M, Rihova B. Biological evaluation of mitomycin C bound to a biodegradable polymeric carrier. J Control Release. 1997 Jul 7;47(1):71–80. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Watermann I, Gerspach J, Lehne M, Seufert J, Schneider B, Pfizenmaier K, et al. Activation of CD95L fusion protein prodrugs by tumor-associated proteases. Cell Death Differ. 2007 Apr;14(4):765–74. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402051. Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kisiday J, Jin M, Kurz B, Hung H, Semino C, Zhang S, et al. Self-assembling peptide hydrogel fosters chondrocyte extracellular matrix production and cell division: Implications for cartilage tissue repair. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002 Jul 23;99(15):9996–10001. doi: 10.1073/pnas.142309999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Miller JS, Shen CJ, Legant WR, Baranski JD, Blakely BL, Chen CS. Bioactive hydrogels made from step-growth derived PEG-peptide macromers. Biomaterials. 2010 May;31(13):3736–43. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.01.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vessillier S, Adams G, Chernajovsky Y. Latent cytokines: development of novel cleavage sites and kinetic analysis of their differential sensitivity to MMP-1 and MMP-3. Protein Eng Des Sel. 2004 Dec;17(12):829–35. doi: 10.1093/protein/gzh097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Diaz N, Suarez D. Peptide hydrolysis catalyzed by matrix metalloproteinase 2: A computational study. J Phys Chem B. 2008 Jul 17;112(28):8412–24. doi: 10.1021/jp803509h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zustiak SP, Leach JB. Hydrolytically Degradable Poly(Ethylene Glycol) Hydrogel Scaffolds with Tunable Degradation and Mechanical Properties. Biomacromolecules. 2010 May;11(5):1348–57. doi: 10.1021/bm100137q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Erickson HP. Size and Shape of Protein Molecules at the Nanometer Level Determined by Sedimentation, Gel Filtration, and Electron Microscopy. Biol Proced Online. 2009 Dec;11(1):32–51. doi: 10.1007/s12575-009-9008-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Roberts JJ, Bryant SJ. Comparison of photopolymerizable thiol-ene PEG and acrylate-based PEG hydrogels for cartilage development. Biomaterials. 2013 Dec;34(38):9969–79. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.09.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shih H, Lin CC. Cross-Linking and Degradation of Step-Growth Hydrogels Formed by Thiol-Ene Photoclick Chemistry. Biomacromolecules. 2012 Jul;13(7):2003–12. doi: 10.1021/bm300752j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Spinale FG, Coker ML, Heung LJ, Bond BR, Gunasinghe HR, Etoh T, et al. A matrix metalloproteinase induction/activation system exists in the human left ventricular myocardium and is upregulated in heart failure. Circulation. 2000 Oct 17;102(16):1944–9. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.16.1944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lutolf MP, Lauer-Fields JL, Schmoekel HG, Metters AT, Weber FE, Fields GB, et al. Synthetic matrix metalloproteinase-sensitive hydrogels for the conduction of tissue regeneration: Engineering cell-invasion characteristics. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003 Apr 29;100(9):5413–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0737381100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chen XY, Plasencia C, Hou YP, Neamati N. Synthesis and biological evaluation of dimeric RGD peptide-paclitaxel conjugate as a model for integrin-targeted drug delivery (vol 48, pg 1099, 2005) J Med Chem. 2005 Sep 8;48(18):5874. doi: 10.1021/jm049165z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bae M, Cho S, Song J, Lee GY, Kim K, Yang J, et al. Metalloprotease-specific poly(ethylene glycol) methyl ether-peptide-doxorubicin conjugate for targeting anticancer drug delivery based on angiogenesis. Drug Exp Clin Res. 2003;29(1):15–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Jose S, Hughbanks ML, Binder BY, Ingavle GC, Leach JK. Enhanced trophic factor secretion by mesenchymal stem/stromal cells with glycine-histidine-lysine (GHK)-modified alginate hydrogels. Acta Biomater. 2014 Jan 24; doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2014.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hoffman MD, Xie C, Zhang X, Benoit DS. The effect of mesenchymal stem cells delivered via hydrogel-based tissue engineered periosteum on bone allograft healing. Biomaterials. 2013 Aug 16;34(35):8887–98. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Brudno Y, Ennett-Shepard AB, Chen RR, Aizenberg M, Mooney DJ. Enhancing microvascular formation and vessel maturation through temporal control over multiple pro-angiogenic and pro-maturation factors. Biomaterials. 2013 Dec;34(36):9201–9. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Predicted structures for various “N” and “2T” peptides. Comparing peptides that lost (KRX-725 and SPARC3X) and retained (SPARC113 and Qk) bioactivity upon inclusion of the “2T”, no clear change in structure between “N” and “2T” form was observed. Arrowheads point to C-termini; color gradient also indicates directionality (blue = N-termini, red = C-termini).

Demonstration of released peptide stability. 0.8 μmol of “2T” peptide in 1 mL buffer or buffer containing 10 nM MMP2 was incubated at 37 ºC, and the amount of peptide remaining in its “2T” form tracked over time using HPLC. (A) SPARC118(2T), (B) SmPho(2T), (C) SPARC3X(2T), (D) SPARC113(2T), (E) Scrambled(2T), and (F) Qk(2T). The peptides remained stable in both solutions, indicating that peptides are not degraded after release from the hydrogel network. n=1.