Clinical nephrology has advanced rapidly due to recent breakthroughs in genomic medicine. Several forms of nephropathy heretofore labeled “idiopathic” now have a well-defined genetic basis; more will follow. Whereas it was once taboo to suggest that population ancestry-based genetic variation contributes to ethnic-specific risk for end-stage kidney disease (ESKD), the identification of impressive genetic association between two coding variants in the apolipoprotein L1 gene (APOL1) and a spectrum of non-diabetic nephropathies in individuals with recent African ancestry unequivocally proves this to be the case.1 This finding is a striking and unusual example where variation in a single gene associates with pronounced risk for a complex disease. The two nephropathy-risk variants include G1, a non-synonymous coding variant, and G2, a six-base pair deletion. Each chromosome 22 typically possesses only a G1 or a G2 APOL1 allele (alleles are mutually exclusive on a single chromosome). About 13% of African Americans have two APOL1 nephropathy-risk variants and 49% lack a risk variant.1 Possession of two APOL1 nephropathy-risk variants (G1/G1, G1/G2, or G2/G2) is associated with markedly increased risk for progressive chronic kidney disease (CKD) due to focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS), focal global glomerulosclerosis (FGGS), primary and secondary forms of FSGS-collapsing variant (notably HIV-associated nephropathy), sickle cell nephropathy and severe lupus nephritis.2 Although these disorders are primarily classified based on glomerular pathology, they manifest pronounced interstitial and vascular changes potentially relating to APOL1. The mechanism(s) by which an APOL1 variant may cause this renal injury remains undefined. Individuals of European, Asian and Hispanic descent virtually lack APOL1 G1 and G2 nephropathy-risk alleles. Selection for nephropathy-associated risk variants likely occurred about 10,000 years ago in sub-Saharan Africa due to protection from infection with Trypanosma brucei rhodesiense, a cause of African sleeping sickness. This benefit requires the presence of only one APOL1 variant. Possession of two variants (versus zero or one variant; autosomal recessive inheritance) in APOL1 fully explains the majority of the excess risk of non-diabetic CKD in African Americans relative to European Americans. These same APOL1 variants in deceased African American organ donors predispose to shortened allograft survival after kidney transplantation. Translating the APOL1 molecular breakthrough in the clinic will ultimately improve risk prediction and lead to novel therapies to prevent kidney failure. This commentary makes the case that considering APOL1 risk variants in kidney transplantation will likely be an important clinical application that transforms current practice.

Nephrologists in the United States have long known that “kidneys in African American patients respond differently to hyperglycemia and systemic hypertension than kidneys in European American patients.” Similar observations have been made in transplantation, whereby kidneys donated by African Americans had significantly shorter allograft survival after transplantation, whether transplanted into African American or non-African American recipients. African American recipients have higher likelihoods of prolonged allograft survival when receiving non-African American deceased donor kidneys. Human and animal studies have shown that hypertension and salt sensitivity travel with transplanted kidneys and impact these phenotypes in recipients.3 These observations support the postulate that genetic variation in the cells of donor kidneys substantially affects blood pressure and renal function. Therefore, it should not be surprising that nephropathy-susceptibility alleles in donor kidneys impact allograft survival.

Before reviewing genetic influences on outcomes of kidney transplantation, environmental factors impacting survival of living- and deceased-donor allografts must be considered. Given the importance of APOL1 gene-environment interactions, modifiable environmental effects likely impact transplantation outcomes.2 Relative to recipients of deceased-donor kidneys, allograft survival is typically longer in recipients of living-donor kidneys. This difference reflects, in part, a more orderly pre-operative assessment of the renal and vascular anatomy, kidney function, and proteinuria of a living donor. In contrast, deceased-donor kidneys become available in unpredictable fashions, often at night and on weekends. Clinical information on pre-morbid kidney function in these donors may be less complete. In addition, proteinuria can be masked (and clearance function overestimated) due to hemodilution as a consequence of the frequent administration of large volumes of intravenous fluids to maintain blood pressure and optimize organ perfusion in the setting of brain death. Transplantation of deceased-donor kidneys with acute kidney injury can impose even greater difficulty for determination of baseline kidney function. Hence, relative to assessments of living donors, evaluations of deceased donors are less likely to detect mild or subclinical kidney dysfunction; kidneys with functional impairment may inadvertently be transplanted. These stressed deceased-donor kidneys are then subjected to cold ischemia (often prolonged) and nephrotoxic immunosuppression (calcineurin inhibitor) is often administered shortly after organ reperfusion. Furthermore, there is the potential for greater antigenic diversity in unrelated donors. As environmental stresses to transplanted kidneys differ for living versus deceased donors, they may differentially interact with inherent, genetically determined, variations in risk in the allografts. These factors collectively contribute to the poorer long-term survival of deceased-donor allografts.

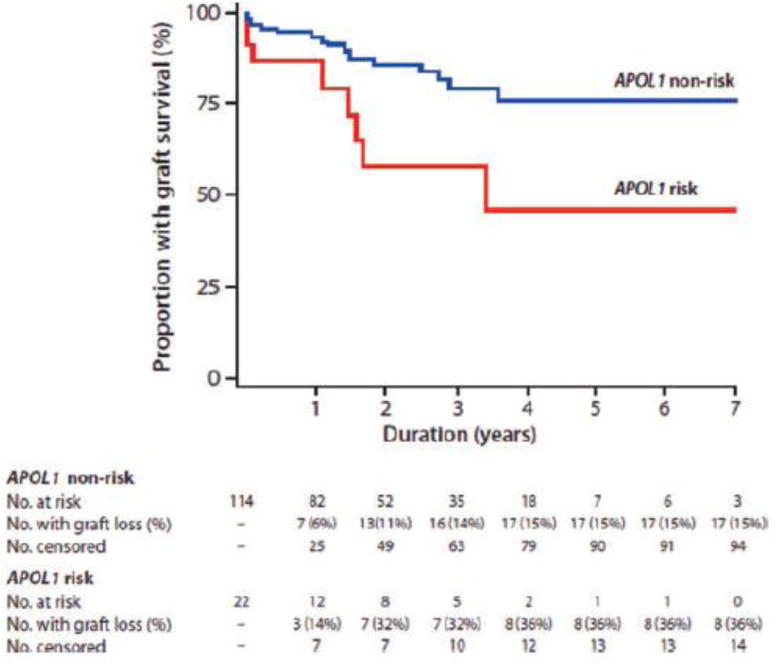

From the standpoint of genetics in transplantation, differences exist in renal-allograft survival based on donor ancestry. Shorter allograft survival is typically observed with African American donor kidneys. As a result, variation in APOL1 was assessed in kidney donors and recipients of recent African ancestry. A Wake Forest report analyzed outcomes after deceased-donor kidney transplantation based on donor APOL1 genotypes.4 One hundred thirty-six kidneys had been procured from 106 African American deceased organ donors and transplanted at that center. Kidneys from donors with two APOL1 risk variants comprised 16% (22/136) of the transplanted organs, a proportion similar to the 13% frequency of two-risk-variant persons in general African American populations. Cox-proportional hazard models assessed association between donor genotype and time to allograft failure. In a multivariate analysis that accounted for effects of donor APOL1 genotypes, estimated African ancestry across the genome, standard-criteria (versus expanded-criteria) donation, recipient age, recipient sex, degree of human leukocyte antigen (HLA) match, cold ischemia time (CIT), and sensitization based on panel reactive antibodies (PRA) at transplantation, only donor APOL1 genotype and HLA match significantly impacted outcomes after transplantation. Kidneys from donors with two APOL1 risk variants (hazard ratio [HR] 3.84; p=0.008) and greater degrees of HLA mismatch (HR 1.52; p=0.03) had shorter allograft survival, with a statistical trend observed for an adverse effect for longer CIT (HR 1.06; p=0.057). Figure 1 displays the Kaplan-Meier renal allograft survival curve based on APOL1 genotype from this report. Donor African ancestry beyond APOL1 did not significantly impact outcomes. APOL1 genotypes were unavailable in recipients but were unlikely to have affected allograft survival; non-African American patients (who almost universally lack APOL1 risk alleles) comprised approximately 50% of the transplant recipients and had slightly shorter renal-allograft survival than did African American recipients. This study strongly suggested that APOL1 genotype of the donor, not the recipient, impacts allograft failure in deceased-donor kidney transplantation. Renal histology in most patients whose failed allografts came from donors with two APOL1 risk variants revealed APOL1-associated lesions, including FSGS, FSGS-collapsing variant, and donor-associated nephron scarring with arteriosclerosis. Finally, survival of deceased-donor allografts from African Americans with fewer than two APOL1 risk variants was similar to that of kidneys from European Americans. This finding suggests that much of the observed risk for shorter survival of African American deceased-donor allografts, relative to that for non-African American deceased-donor kidneys, is mediated by the APOL1 G1 and G2 variants.

Figure 1. Renal allograft survival according to APOL1 genotype.

Kaplan-Meier renal allograft survival curve for recipients of donor kidneys with (red line) and without (blue line) two APOL1 risk variant alleles. [Reprinted with permission: American Journal of Transplantation 2011; 11: 1025–1030].

A larger subsequent report from Wake Forest and University of Alabama at Birmingham evaluated survival of 675 renal allografts from African American deceased donors. Kidney transplantations and procurements were performed at 55 American centers and results were based on outcomes in the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients (Freedman BI, Julian BA, Pastan SO, et al. Apolipoprotein L1 gene variants in deceased organ donors are associated with renal allograft failure [abstract). J Am Soc Nephrol 2014; In Press). This analysis adjusted for all covariates in the initial report,4 except genome-wide African ancestry. Presence of two APOL1 risk variants in donors again predicted significantly shorter allograft survival (HR 2.26; p=0.001); recipient African American ancestry and expanded-criteria donation were also associated with allograft failure. Despite heightened risk for early allograft failure, many APOL1 two-risk-variant kidneys functioned for prolonged periods. This multi-center report confirmed the earlier finding that APOL1 G1 and G2 variants, without additional markers, could risk-stratify deceased-donor kidneys.

In contrast to the significant effect of the donor’s APOL1 genotype on survival of a renal allograft, there is no apparent effect of the recipient’s genotype. Lee et al. evaluated the impact of recipient APOL1 genotypes on kidney allograft outcomes in 119 African American recipients.5 Although 49% of the recipients in this retrospective analysis possessed two risk variants, at five years after engraftment there was no difference in allograft survival in recipients with two APOL1 risk variants versus those with fewer than two. Thus, the APOL1 genotype of recipients apparently does not alter the risk of renal allograft failure and a two-risk-allele genotype for a potential recipient should not discourage transplantation.

The impact of APOL1 on living donors after nephrectomy is uncertain. In the span of 1993–2005, 0.10% of European Americans and 0.51% of African Americans who donated a kidney developed ESKD within that timeframe.6 Some investigators have called for pre-donation APOL1 genotyping in African American living potential donors. However, no cohort study has yet addressed this important question. A case report of kidney transplantation in donor-recipient monozygotic twin brothers of African Caribbean ancestry raises some concern.7 The recipient had ESKD of unknown etiology. Six months after transplantation he developed proteinuria. Two years later his estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) had decreased; biopsy showed FSGS and moderate interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy. Despite glucocorticoid treatment, the allograft failed five years after engraftment. Subsequently, the donor developed proteinuria and reduced eGFR seven years after nephrectomy. Both brothers were APOL1 G1/G2 compound heterozygotes (each with two risk alleles). Although even one such case is of concern, the living donor evaluation process generally performs well. The higher rates of ESKD after living kidney donation in African Americans, relative to that in European Americans, appear to reflect higher rates of CKD in general populations.8 Based on favorable outcomes after living kidney donation with careful pre-donation assessment of kidney function and proteinuria, we must await studies addressing whether genotyping potential living donors of recent African ancestry for APOL1 risk variants will improve outcomes in donors with two risk variants and improve survival of their transplanted kidneys. Nonetheless, caution is advised regarding child-to-parent donation from young African Americans. These donors may not display final kidney phenotypes until they are older.

In contrast to the currently uncertain status for APOL1-risk-variant genotyping of living kidney donors, the case for testing deceased donors with recent African ancestry appears sound. Significantly shorter renal allograft survivals are reproducibly observed for kidneys from deceased donors with two APOL1 risk variants. Genetic information at the APOL1 G1 and G2 nephropathy risk markers is important to consider in the informed consent process and to risk-stratify deceased-donor kidneys prior to allocation. APOL1-two-risk-variant kidneys might best be utilized in clinical settings where expanded-criteria-donor kidneys are appropriate. APOL1-two-risk-variant kidneys have a greater probability of early allograft failure; however, those that function longer than three years appear likely to function for prolonged periods. As for patients with native-kidney disease of whom a minority with two APOL1 risk variants develops nephropathy, modifying environmental factors are likely involved in loss of allograft function. This interaction would explain why only a subset of high-risk kidneys fail early after transplantation.2

In an era of precision medicine, rapid genotyping of deceased African American kidney donors is coming of age. The greater risk for non-diabetic nephropathy in individuals with recent African ancestry derives predominantly from variation at the APOL1 G1 and G2 loci. Higher rates of allograft failure after deceased-donor kidney transplantation, long attributed to being African American, also derive from variation at APOL1. Rapidly performed polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based testing for viral infections (hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and HIV) is now standard for deceased organ donors. PCR-based genotyping for APOL1 G1 and G2 risk variants in deceased kidney donors with African ancestry should be implemented and its quality control ensured. If the clinical impact of the APOL1 nephropathy-risk variants on survival of renal allografts survival is confirmed in a clinical trial, this genotype data will likely supplant the “race=African American” element in the new kidney donor profile index,9 although its weighting in the formula remains to be calculated. Given that kidneys for transplantation are in short supply, APOL1 genotyping of African American deceased kidney donors would contribute to a more rational organ allocation and also improve long-term outcomes.

Footnotes

Reference List

- 1.Genovese G, Friedman DJ, Ross MD, et al. Association of trypanolytic ApoL1 variants with kidney disease in African Americans. Science. 2010;329:841–845. doi: 10.1126/science.1193032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Freedman BI, Skorecki K. Gene-gene and gene-environment interactions in apolipoprotein L1 gene-associated nephropathy. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014 doi: 10.2215/CJN.01330214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Curtis JJ, Luke RG, Dustan HP, et al. Remission of essential hypertension after renal transplantation. N Engl J Med. 1983;309:1009–1015. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198310273091702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reeves-Daniel AM, Depalma JA, Bleyer AJ, et al. The APOL1 gene and allograft survival after kidney transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2011;11:1025–1030. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03513.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee BT, Kumar V, Williams TA, et al. The APOL1 genotype of African American kidney transplant recipients does not impact 5-year allograft survival. Am J Transplant. 2012;12:1924–1928. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2012.04033.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gibney EM, King AL, Maluf DG, et al. Living kidney donors requiring transplantation: focus on African Americans. Transplantation. 2007;84(5):647–649. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000277288.78771.c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kofman T, Audard V, Narjoz C, et al. APOL1 polymorphisms and development of CKD in an identical twin donor and recipient pair. Am J Kidney Dis. 2014;63:816–819. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2013.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lentine KL, Schnitzler MA, Xiao H, et al. Racial variation in medical outcomes among living kidney donors. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:724–732. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1000950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Israni AK, Salkowski N, Gustafson S, et al. New national allocation policy for deceased donor kidneys in the United States and possible effect on patient outcomes. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014 doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013070784. Epub. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]