Abstract

Objective

Significant reductions in gynecologic (GYN) cancer mortality and morbidity require treatments that prevent and reverse resistance to chemotherapy and radiation. The objective of this study was to determine if pharmacologic inhibition of key DNA damage response kinases in GYN cancers would enhance cell killing by platinum-based chemotherapy and radiation.

Methods

A panel of human ovarian, endometrial and cervical cancer cell lines were treated with platinum drugs or ionizing radiation (IR) along with small molecule pharmacological kinase inhibitors of Ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM) and ATM and Rad-3-related (ATR).

Results

Pharmacologic inhibition of ATR significantly enhanced platinum drug response in all GYN cancer cell lines tested, whereas inhibition of ATM did not enhance the response to platinum drugs. Co-inhibition of ATM and ATR did not enhance platinum kill beyond that observed by inhibition of ATR alone. By contrast, inhibiting either ATR or ATM enhanced the response to IR in all GYN cancer cells, with further enhancement achieved with co-inhibition.

Conclusions

These studies highlight actionable mechanisms operative in GYN cancer cells with potential to maximize response of platinum agents and radiation in newly diagnosed as well as recurrent gynecologic cancers.

Keywords: DNA damage repair response, ATR, ATM, Gynecologic cancer, Cisplatin resistance, Ionizing radiation

Background

Gynecologic (GYN) cancers, specifically cancers of the uterine cervix, uterine corpus, and ovary, represent a significant worldwide health problem with 1,085,948 new diagnoses and 493,713 deaths observed annually (globocan.iarc.fr). Primary cytoreductive surgery with platinum- and paclitaxel-based chemotherapy, either in the adjuvant or neoadjuvant setting, are the standards of care for ovarian cancer [1]. Surgical staging plays a central role in endometrial cancer management, with platinum-based chemotherapy, radiation and/or hormonal therapy deployed in the adjuvant and salvage setting [1]. Chemoradiation and ionizing radiation (IR) are standard treatments for cervical cancer with platinum-based combination chemotherapy used for patients with advanced and recurrent disease [1]. Although response rates in these disease settings range from 34 to 77% [1], only 27%, 17% or 16% of women with advanced ovarian, endometrial or cervical cancer will be alive 5 years after diagnosis, respectively [2].

Ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM) and ATM and Rad-3-related (ATR) are two related phosphatidyl inositol 3-kinase-like protein (PIKK) kinases that act proximal in DNA damage response (DDR) pathways, differentially recognize genotoxic stress, and function to initiate cell cycle arrest and activate appropriate DNA repair mechanisms [3, 4]. ATR becomes activated in response to arrested replication forks via its recruitment by replication protein A (RPA)-coated single-stranded (ss) DNA that involves topoisomerase binding protein 1 (TOPBP1) as well as the 9–1–1 complex [3,4]. The ATR effector kinase, checkpoint kinase 1 (Chk1), is activated by phosphorylation of Ser317 and Ser345 by ATR [5,6]. Chk1 can phosphorylate multiple G2/M checkpoint targets, including CDC25C and the tumor suppressor p53 [4–6]. Canonical ATM activation occurs in response to DNA double strand breaks (DSBs) via the MRN (MRE11–RAD50–NBS1) complex [3,4]. The principle ATM effector kinase, checkpoint kinase 2 (Chk2), is activated through phosphorylation of Thr68 and plays significant roles in regulating cell cycle progression by phosphorylating myriad proteins, including p53 [3,4].

Significant reductions in GYN cancer patient mortality and morbidity rates require treatments that proactively prevent and reverse resistance to chemotherapy and radiation. Combining chemotherapy and radiation with inhibitors of key DDR proteins targets is likely to enhance the ability of genotoxic treatments to kill a variety of cancer cells [7–16]. Previous studies have demonstrated the benefits of targeting DDR pathways to enhance response of a broad range of genotoxic therapies, including chemotherapy and radiation [7,9,13,14,16–21].

Given the pivotal roles that platinum agents and radiation play in the treatment of GYN cancers, the success of targeting DDR pathways to enhance genotoxin response, including in ovarian and cervical cancers [1], the prevalence of defects in homologous recombination in ovarian and endometrial cancers [22–24], the strong link between human papilloma virus and DDR pathways [25,26], and the availability of more selective inhibitors of ATR and ATM, and that ATR kinase inhibitors have been shown to sensitize ATM- and p53-deficient cells to cisplatin [27], we sought to evaluate the impact of selectively inhibiting ATR and ATM in a panel of sensitive and resistant ovarian cancer cells as well as endometrial and cervical cancer cells with wild type or mutant p53 treated with cisplatin, carboplatin, or IR. We hypothesized that targeting these DDR pathways in GYN cancer cells would synergize with platinum-based chemotherapy and radiation. For these studies, we utilized small molecule pharmacologic kinase inhibitors of ATR (ETP-46464, “ATRi”) [28] and ATM (KU55933, “ATMi”) [29] and show enhancements in the response of IR in human cervical, endometrial and ovarian carcinoma in vitro, independent of p53 status. Further, our data show that selective inhibition of ATR, but not ATM, synergizes with platinum in cell line models in all three disease sites, independent of p53 status. This divergent response is of central importance as it informs the selective use of ATR inhibitors, but not ATM inhibitors, with cisplatin- or carboplatin-based chemotherapy, and directs the combined use of ATR and ATM inhibitors with radiation or cisplatin-based chemoradiation in newly diagnosed and recurrent ovarian, endometrial and cervical cancer.

Methods

Cell culture

A2780 and A2780-CP20 (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) and maintained in RPMI medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, ATCC, Manassas, VA). A2780-CP20 cells were treated with 1 µM cisplatin (Sigma) every other passage to maintain resistance to cisplatin. OVCAR3 cells maintained in RPMI medium supplemented with 20% FBS and 0.01 mg/mL insulin (Sigma) or DMEM:F12 with 10% FBS and 0.01 mg/mL insulin. KLE cells were maintained in DMEM:F12 medium supplemented with 10% FBS. HELA, SIHA, and HEC1B cells were maintained in Eagle's Minimum Essential Medium or DMEM:F12 supplemented with 10% FBS. All cells were maintained at 37 °C and 5% CO2. OVCAR3, HELA, SIHA, HEC1B and KLE were purchased from ATCC. The identities of all cell lines utilized were verified by short tandem-repeat testing and were confirmed to be mycoplasma-free (Universal Mycoplasma Detection Kit, ATCC).

Cell viability assay

Cells were trypsinized with 0.25% Trypsin-EDTA (ATCC) and counted with 0.4% Trypan Blue using an automated cell counter (TC10, Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) and plated in 96-well plates at 5000 cells per well for KLE, HEC1B and HELA and 10,000 cells per well for OVCAR3, A2780, A2780-CP20 and SIHA (all cells were obtained in 2012). After cells attached and reached approximately 60% confluency (24–48 h post seeding), media was removed and replaced with fresh media containing cisplatin (0, 0.78, 1.56, 3.13, 6.25, 12.5, 25 or 50 µM) or carboplatin (0, 1.56, 3.13, 6.25, 12.5, 25, 50 or 100 µM) in 0.15% DMSO, 5 µM ETP-46464 (ETP46464 was synthesized by the Medicinal Chemistry Shared Resource of the Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center, supported in part by NCI Grant CA16058), 10 µM KU55933 (Tocris Biosciences), or a combination of 5 µM ETP-46464 and 10 µM KU55933 and incubated for 72 h. Final concentrations of ETP-46464 and KU55933 utilized were based on prior evidence indicating inhibition of ATR and ATM signaling, respectively [18]. Single-agent dose response analyses of ETP-46464 and KU55933 in a subset of cell lines revealed a wide LD50 range (10.0 ± 8.7 and 38.3 ± 7.6 µM, respectively). Similarly, cells were treated with fresh media containing cisplatin (0, 0.78, 1.56, 3.13, 6.25, 12.5, 25 or 50 µM) in 0.08% DMSO and 5 µM VE-821 (Selleck Chemicals). Cell viability was assessed using the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium (MTS) CellTiter 96 Aqueous One Solution Cell Proliferation Assay (Promega, Madison, WI) according to the manufacturer's instructions. After a 2 h incubation at 37 °C, absorbance was measured at 490 nm using a microplate spectrophotometer (xMark, Bio-Rad). Three biological replicates were performed for each cell line where each inhibitor(s)/cisplatin concentration was assayed in triplicate for each experiment. The combination index (CI) value (<1) and Fa–CI (Chou–Talalay's Plot) were obtained with CompuSyn (ver 3.0.1; ComboSyn, Inc., Paramus, NJ).

Clonogenic survival assay

A2780, HEC1B, HELA and SIHA were plated at a density of 1000 cells and OVCAR3 at 1500 cells per plate in triplicate, incubated for 4 h (OVCAR3 overnight) at 37 °C/5% CO2 to allow cells to adhere, respectively, and treated with 0.15% DMSO, 5 µM ETP-46464, 10 µM KU55933 or a combination of 5 µM ETP-46464 and 10 µM KU55933 15 min prior to γ-ray exposure in a 137Cs irradiator (Shepherd Mark I model, J.L. Shepherd & Associates, San Fernando, CA) at a dose rate of 78.3 R/min. Eight total fractional exposures were used corresponding to 0, 0.5, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6 Gy. Cultures were incubated for 4 h followed by removal of drug and addition of fresh media and an additional 9–14 days until mean colony size comprised ≥50 cells, and stained with Giemsa for colony counting. Data reported represent three biological replicates for DMSO, ATRi and ATMi treatments and two biological replicates for combination treatment with ATRi and ATMi for each cell line.

Immunoblot analyses

A2780, HEC1B and HeLa cells were plated and treated according to the following conditions and as described above for the cell viability or the clonogenic assays. Cells were washed with cold PBS and lysed 1% SDS, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM NaF, 1% Tween 20, 0.5% NP40, 50 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5 and 1× Halt protease and phosphatase inhibitor (Pierce). Equivalent amounts of protein lysates were resolved via 4–15% mini-PROTEIN TGX gels (Bio-Rad) and transferred to PVDF membranes. Membranes were blocked for 1 h using 5% non-fat dry milk (Bio-Rad) and incubated with primary antibody overnight at 4 °C, secondary antibody for 4 h at ambient temperature or overnight at 4 °C, and SuperSignal West Dura Chemiluminescent Substrate (ThermoFisher Scientific) for 5 min. Anti-pATM (S1981) and anti-β actin were from Abcam. Anti-ATM was from Thermo Scientific. Anti-ATR, anti-pChk1 (S345), anti-Chk1, anti-pChk2 (Thr68), anti-Chk2, anti-PARP, anti-cleaved PARP, anti-caspase 3, anti-cleaved caspase 3, goat anti-mouse and goat anti-rabbit IgG HRP-linked were from Cell Signaling Technologies. All primary antibodies were used at a 1:1000 dilution. Immunoblots were first probed for cleaved PARP followed by total PARP (Fig. 5B). Similarly, blots were first probed for cleaved caspase 3 followed by total caspase 3 (Fig. 5C and D). Images were acquired using a ChemiDoc XRS+ system (Bio-Rad).

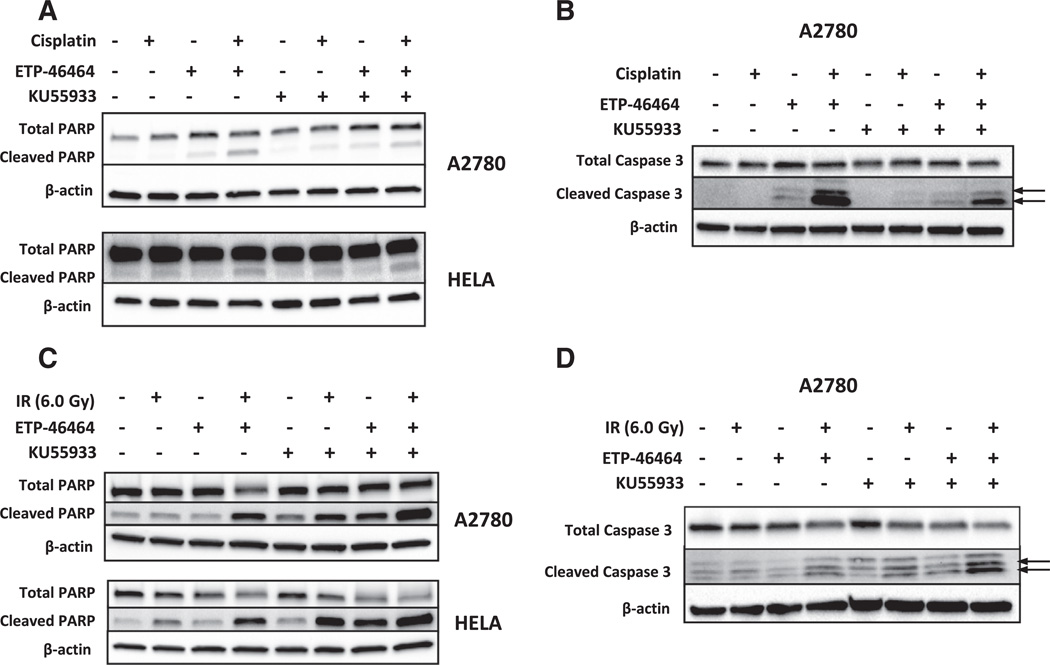

Fig. 5.

Cisplatin-induced apoptosis is enhanced by pharmacologic inhibition of ATR whereas IR-induced apoptosis is increased by inhibition of ATR and/or ATM. A. Total and cleaved levels of poly(ADP) ribose polymerase (PARP) were assessed by immunoblotting in gynecologic cancer cells treated with 0.15% DMSO, ETP-46464 (5.0 µM), KU55933 (10.0 µM), or a combination of ETP-46464 (5.0 µM) and KU55933 (10.0 µM) in the presence or absence of cisplatin at their LD50 concentration (A2780, 3.0 µM; HEC1B, 20.0 µM) for 24 h followed immunoblot detection of the PARP holoenzyme or cleaved PARP. B. Pharmacologic inhibition of ATR results in elevated levels of cleaved caspase 3 in cisplatin treated A2780 ovarian cancer cells. A2780 cells were treated with 0.15% DMSO, ATRi (ETP-46464, 5.0 µM), ATMi, (KU55933, 10.0 µM) or a combination of ATRi (ETP-46464, 5.0 µM) and ATMi, (KU55933, 10.0 µM) in the presence or absence of cisplatin at their LD50 (3.0 µM) for 24 h followed immunoblot detection of the caspase 3 holoenzyme or cleaved caspase 3 (indicated by the arrows). C. Immunoblot analyses of total and cleaved PARP in gynecologic cancer cells treated with 0.15% DMSO, ETP-46464 (5.0 µM), KU55933 (10.0 µM), or a combination of ETP-46464 (5.0 µM) and KU55933 (10.0 µM) with or without IR exposure (6.0 Gy). Cells were harvested 48 h post IR exposure followed immunoblot detection of the PARP holoenzyme or cleaved PARP. D. Pharmacologic inhibition of ATR and/or ATMi results in elevated levels of cleaved caspase 3 in irradiated A2780 ovarian cancer cells. A2780 cells were treated with 0.15% DMSO, ETP-46464 (5.0 µM), KU55933 (10.0 µM), or a combination of ETP-46464 (5.0 µM) and KU55933 (10.0 µM) with or without IR exposure (6.0 Gy) followed immunoblot detection of the caspase 3 holoenzyme or cleaved caspase 3 (indicated by the arrows).

Statistical analysis

Paired Student's t-tests were used to determine the statistical significance of the cisplatin LD50 between treatment conditions obtained from the MTS assay across cell lines. The effect of IR sensitization was determined by fitting clonogenic survival curves to a linear-quadratic model (S = exp(−(αD + βD2)), where S = survival, D = dose). A Student's t-test was used (two-tailed distribution, unequal variances) to determine the statistical significance of the IR sensitization at 3 and 4 Gy.

Results

Analysis of DDR protein expression across representative cell line models of gynecologic cancer

Protein abundances of ATR, ATM, Chk1, Chk2, and p53 were analyzed by immunoblot in seven cell line models of GYN carcinoma, including three models of ovarian [A2780, A2780-CP20 (a syngeneic model of cisplatin resistance derived from A2780), and OVCAR3], two models of cervical (HELA and SIHA) and two models of endometrial (KLE and HEC1B) carcinoma (Supplementary Fig. 1). Total ATR levels were largely invariant in these cells, with the exception of OVCAR3 where a greater level of ATR abundance was observed. ATM varied more significantly, with A2780 and A2780-CP20 cells exhibiting the highest levels and OVCAR3 and KLE cells having the lowest levels. Chk1 was most abundant in HEC1B, A2780, and A2780-CP20 cells, and Chk2 was most abundant in A2780, A2780-CP20, and SIHA. Basal levels of p53 were observed to be significantly elevated in OVCAR3, HEC1B, and KLE cells relative to other cell lines. Previous mutational analyses have revealed that A2780-CP20, HEC1B and KLE cells possess mutant TP53, whereas A2780, OVCAR3, HELA and KLE cells are TP53 wild type (Supplementary Table S1) [30,31].

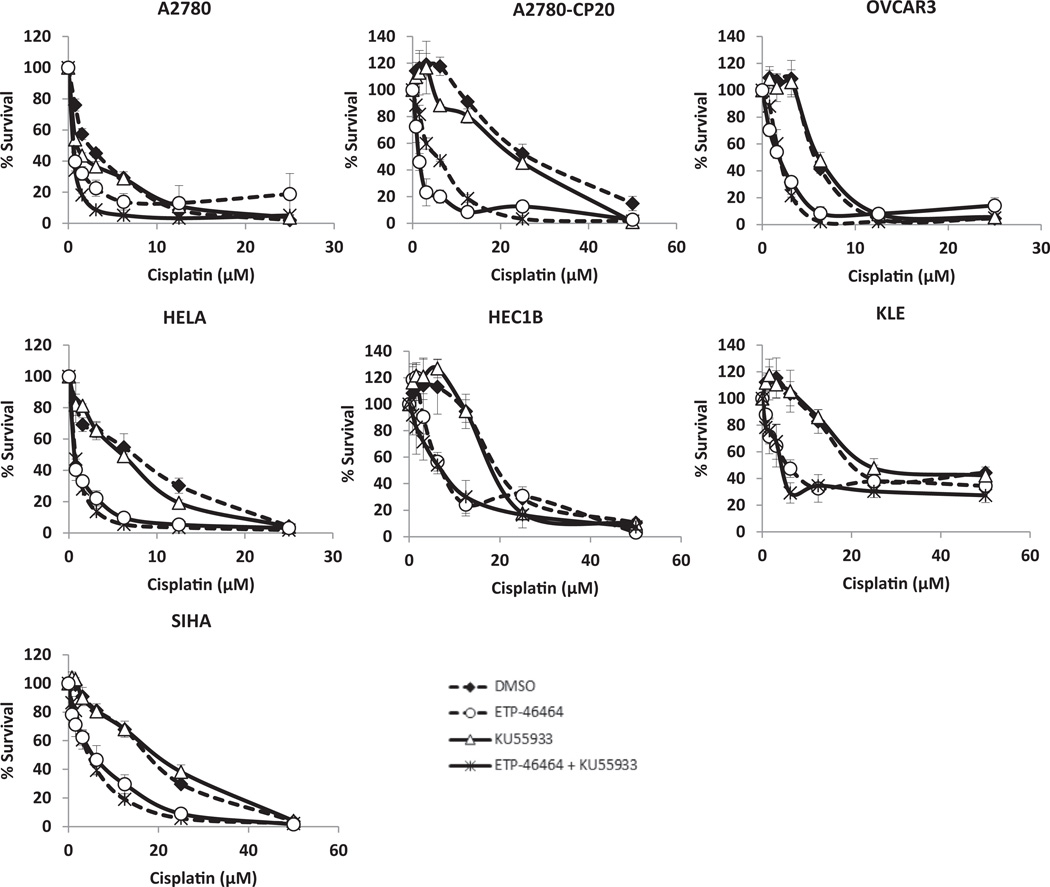

Inhibition of ATR, but not ATM, sensitizes gynecologic carcinoma cells to platinum drugs

Platinum-sensitive and -resistant ovarian, endometrial and cervical cancer cell lines were treated with varying levels of cisplatin (0–50 µM) with or without the ATRi (5.0 µM ETP-46464) and/or the ATMi (10.0 µM KU55933) for 72 h. Single-agent dose response analyses of ATRi and ATMi in a subset of cell lines revealed a wide LD50 range of 10.0 ± 8.7 and 38.3 ± 7.6 µM respectively. Co-treatment doses were chosen based on these studies and previously published evidence of phospho-Chk1 (Ser345) and phospho-ATM (Ser1981) inhibition following ionizing radiation exposure and dose response treatments with ETP-46464 and KU55933 [18]. Treatment with ATRi significantly increased the response of cisplatin in all cell lines tested (Fig. 1), resulting in 52–89% enhancement in activity (Supplementary Table S2) and were synergistic (Supplementary Fig. S2). Treatment with ATMi alone did not significantly alter the response of cisplatin in any of these GYN cancer cells (Fig. 1). The combined inhibition of ATR and ATM enhanced the response of cisplatin to a level equivalent to that observed using ATRi alone (Fig. 1). These effects were independent of p53 status, and were observed in all GYN cancer cells tested (Fig. 1). Treatment with ATRi, but not ATMi, not only sensitized these GYN cancer cell lines to cisplatin, but also enhanced the response of carboplatin (Supplementary Fig. S3). We confirmed these findings using VE-821, another pharmacologic small molecule inhibitor that is highly selective for ATR (Supplementary Fig. 5) [17,20,32].

Fig. 1.

Inhibition of ATR, but not ATM, sensitizes gynecologic cancer cells to cisplatin. Gynecologic cancer cells were treated with 0.15% DMSO, ETP-46464 (5 µM), KU55933 (10 µM) or a combination of ETP-46464 (5 µM) and KU55933 (10 µM) in the presence of cisplatin at varying concentrations (0–50 µM) for 72 h followed by MTS assay to assess cell survival.

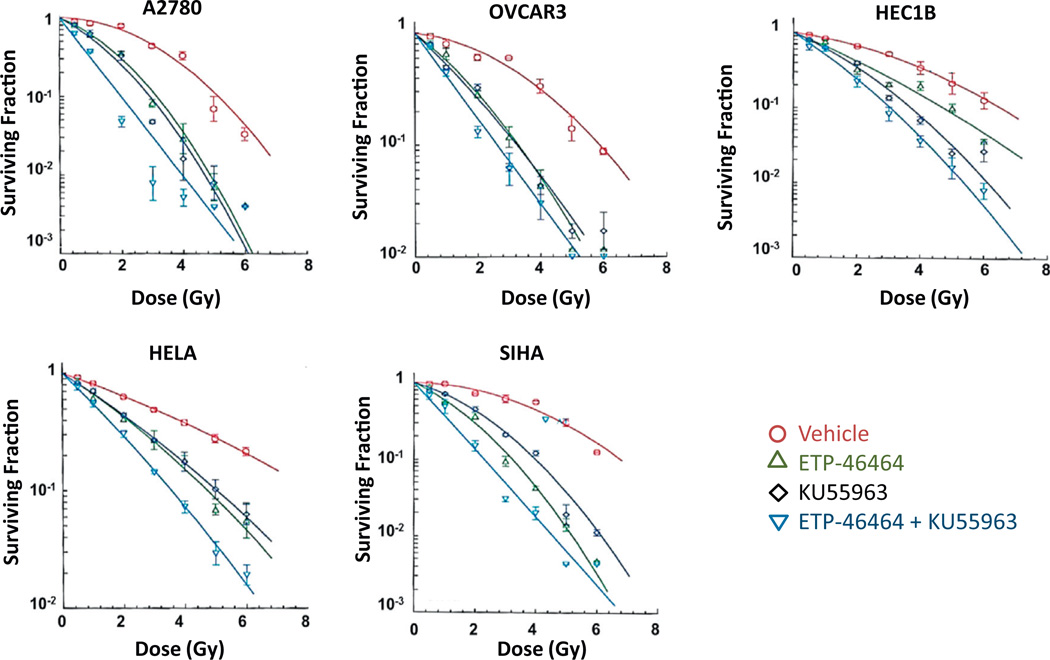

Inhibition of ATR and/or ATM sensitizes gynecologic carcinoma cells to ionizing radiation

Clonogenic survival studies were performed to determine the impact of ATRi and/or ATMi on the response of IR in cell line models of ovarian (A2780 and OVCAR3), cervical (HELA and SiHa), and endometrial (HEC1B) carcinoma. Cells were treated with ATRi (5.0 µM ETP-46464) and/or ATMi (10.0 µM KU55933) for 15 min prior to IR exposure (0–6 Gy) and clonogenic survival was assessed. Significant enhancement in the response of IR was observed with either ATRi or ATMi in all GYN cell lines tested (Fig. 2, Supplementary Fig. S4). Cells inhibited by the combination of ATRi and ATMi exhibited more pronounced IR cell killing when compared to those inhibited by ether inhibitor alone (Fig. 2, Supplementary Fig. S4). These effects were independent of p53 status, and were observed in all GYN cancer cell line models investigated.

Fig. 2.

Inhibition of ATR and ATM sensitizes gynecologic carcinoma cells to ionizing radiation. Gynecologic cancer cells were treated with 0.15% DMSO, ETP-46464 (5 µM), KU55933 (10 µM), or a combination of ETP-46464 (5 µM) and KU55933 (10 µM) for 15 min prior to IR exposure (0–6 Gy). Medium was replaced 4 h post IR with fresh medium without inhibitors and clonogenic survival was assessed 9–14 days later.

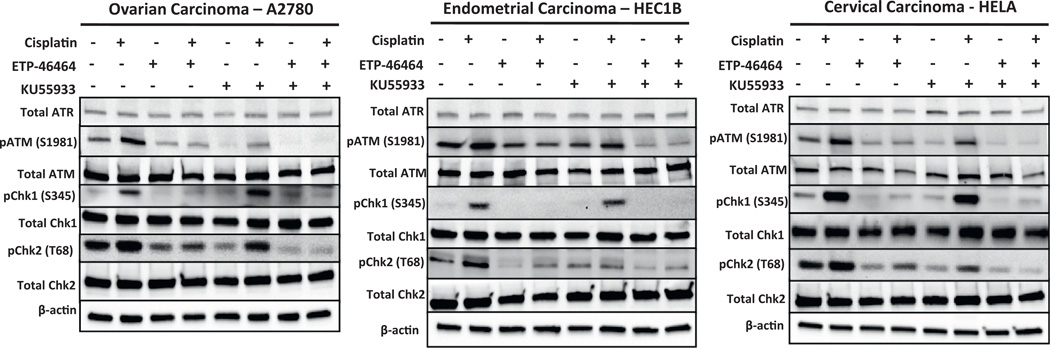

DNA damage response signaling is activated in response to cisplatin treatment in gynecologic cancer cells

To document DDR signaling following exposure to cisplatin alone or in the presence of inhibitors of ATR and/or ATM, immunoblotting was performed in three representative GYN cancer cell lines (A2780, HEC1B, and HeLa) to quantify total and phosphorylated levels of ATR, ATM, Chk1, and Chk2 (Fig. 3). The GYN cancer cell lines were treated at their respective LD50 levels of cisplatin alone or in combination with ATRi (5.0 µM ETP-46464) and/or ATMi (10.0 µM KU55933) for 3 h. Total ATR, ATM, Chk1 and Chk2 did not vary significantly under any of these treatment conditions. Relative to the vehicle control, cisplatin induced classic DDR signaling including the phosphorylation of ATM at position Ser1981, Chk2 at position Thr68, and Chk1 at position Ser345 in these GYN cancer cell lines. A near complete loss of phospho-Chk1 (Ser 345) and partial loss of both phospho-ATM (Ser1981) and phospho-Chk2 (Thr68) were observed when the GYN cancer cells were treated with a combination of cisplatin and ATRi compared to cells treated with cisplatin alone. The cisplatin/ATMi combination did not result in altered phospho-Chk1 (Ser345) levels, but levels of phospho-ATM (Ser1981) and phospho-Chk2 (Thr68) were reduced in these three GYN cancer cell models. As expected, near complete losses of phospho-ATM (Ser1981), phospho-Chk2 (Thr68), and phospho-Chk1 (Ser345) were observed in cells treated with a trio combination of cisplatin, ATRi, and ATMi as compared to cells treated with cisplatin alone, but this did not correspond to further enhancement in response of cisplatin over that provided by ATRi alone. Similar modulations in DDR signaling were also observed when experiments were performed using carboplatin in place of cisplatin (data not shown).

Fig. 3.

ATR signaling is activated in response to cisplatin treatment in gynecologic cancer cells. Immunoblot analyses of total ATR, pATM (Ser1981), total ATM, pChk1 (Ser345), total Chk1, pChk2 (Thr68) and total Chk2 in gynecologic cancer cells treated with 0.15% DMSO, ETP-46464 (5 µM), KU55933 (10 µM), or a combination of ETP-46464 (5 µM) and KU55933 (10 µM) in the presence or absence of cisplatin at their LD50 (A2780, 3 µM; HELA, 10 µM; HEC1B, 20 µM) for 3 h.

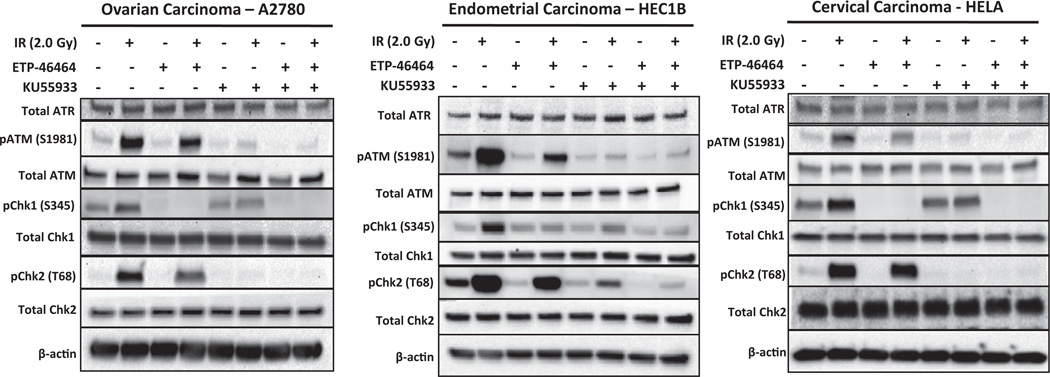

DNA damage response signaling is activated in response to IR exposure in gynecologic cancer cells

Additional immunoblot studies were performed to monitoring DDR signaling in A2780, HEC1B and HeLa cells with ATRi (5.0 µM ETP-46464) and/or ATMi (10.0 µM KU55933) (Fig. 4). None of the treatments induced significant changes in total ATR, ATM, Chk1, or Chk2 levels in the three GYN cancer cell lines. IR alone induced the classic marked increases in phospho-ATM (Ser1981) and phospho-Chk2 (Thr68), and modest increases in phospho-Chk1 (Ser345) relative to cells treated with vehicle alone. Treatment with ATRi and IR resulted in attenuation of phospho-ATM (Ser1981) and phospho-Chk2 (Thr68) and a near complete loss of phospho-Chk1 (Ser345). The ATMi/IR combination resulted in marked loss of phospho-ATM (Ser1981) and phospho-Chk2 (Thr68) and modest decreases in phospho-Chk1 (Ser345). The trio combination of ATRi, ATMi, and IR resulted in significant loss of phospho-ATM (Ser1981), phospho-Chk2 (Thr68), and phospho-Chk1 (Ser345) in all GYN cell lines tested.

Fig. 4.

ATM signaling is activated in response to IR exposure in gynecologic cancer cells. Immunoblot analyses of total ATR, pATM (Ser1981), total ATM, pChk1 (Ser345), total Chk1, pChk2 (Thr68), and total Chk2 in gynecologic cancer cells treated with 0.15% DMSO, ETP-46464 (5 µM), KU55933 (10 µM), or a combination of ETP-46464 (5 µM) and KU55933 (10 µM) with or without IR exposure (2.0 Gy).

Induction of apoptosis following combined treatments with an ATRi, ATMi, and cisplatin or IR in gynecologic cancer cells

Immunoblot studies were performed to examine the cleavage of two surrogate markers of apoptosis, PARP1 and caspase 3, following combined treatments with ATRi, ATMi, and either cisplatin or IR in the GYN cancer cell lines. Two representative GYN cancer cell lines (A2780 and HeLa) were treated with LD50 levels of cisplatin in the absence or presence of ATRi (5.0 µM ETP-46464) and/or ATMi (10.0 µM KU55933) for 24 h. Cisplatin alone had negligible effects on PARP1 (A2780 and HeLA, Fig. 5A) or caspase 3 cleavage (A2780, Fig. 5B). The combined treatment with cisplatin and ATRi alone, or in combination with ATMi, resulted in the greatest cleavage of PARP1 (A2780 and HeLA, Fig. 5A) and caspase 3 (A2780, Fig. 5B) observed in this study. The magnitude of the effects in cells treated with a trio combination of ATRi, ATMi, and cisplatin was similar to that observed with the ATRi and cisplatin combination. Exposure of cells to ATRi and/or ATMi for 15 min followed by exposure to 6 Gy of IR (followed by a 48 h incubation) was associated with the cleavage of PARP1 (A2780 and HeLA, Fig. 5C) and caspase 3 (A2780, Fig. 5D). The cleavage of PARP1 (Fig. 5C) was also observed in A2780 and HeLa cells treated with ATRi or ATMi with greatest levels observed when the ATRi and ATMi were combined with 6 Gy of IR.

Discussion

Here we show that pharmacological inhibition of ATR, but not ATM, sensitizes ovarian, endometrial and cervical cancer cells to cisplatin and carboplatin, and that the combination of either platinum agent with the ATRi was synergistic. We present data utilizing a syngeneic model of platinum-resistant ovarian cancer, A2780 (platinum-sensitive) versus A2780-CP20 (platinum-resistant), showing that inhibition of ATR produces marked enhancement in response when combined with cisplatin or carboplatin. These results demonstrate that ATRi abrogates ATR-dependent phosphorylation of Chk1 induced by platinum-mediated DNA damage. Phosphorylation of Chk1 at Ser345 has been established as a classic indicator of ATR kinase activity [6]. Recent evidence has revealed that treatment with VE-821, another ATR inhibitor, and MK-8776, a Chk1 inhibitor, enhanced cisplatin, gemcitabine, topotecan and veliparib response in ovarian cancer cells [14]. It should be noted that ETP-46464 is an effective inhibitor of other PIKK enzymes, most notably the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) [28]. It has been previously noted that inhibitors of PI3K, mTOR, ATM or DNAPKcs do not generate replicative stress, nor do they enhance hydroxyurea-induced replicative stress [28]. Previously published results have documented the formation of 53BP1 foci in hydroxyurea (HU)-treated cells inhibited with ETP46464, the absence of 53BP1 foci in HU-treated cells inhibited with rapamycin and another mTORi, and that replication fork restart was suppressed by ETP-46464, and not rapamycin [28]. Although the preponderance of the data showing enhanced cisplatin killing of ETP-46464 point to its inhibitory activity on ATR-Chk1 signaling, the known inhibitory activity on mTOR signaling may, in part, contribute to the observed enhanced cisplatin sensitivity. Cellular sensitization to cisplatin was recapitulated with VE-821, another highly selective small molecule pharmacologic inhibitor of ATR (Supplementary Fig. S5).

Treatment of all of the GYN cancer cells in this study with ATRi not only reduced phosphorylation of Chk1 at Ser345 following genotoxic stress, but also phosphorylation of ATM. Loss of phospho-ATM following ATRi treatment is not likely due to non-specific targeting of ATM by ETP-46464 [28]. While ATR kinase inhibitors have been shown to sensitize ATM-deficient cells to cisplatin [27], the seven cell lines studied here expressed ATM and this ATM was functional as it autophosphorylated on serine-1981 following IR. Though ATM becomes activated in response to platinum-based DNA damage, and although this activation is partially abrogated by ATMi, treatment of GYN cells with ATMi and cisplatin or carboplatin did not enhance the response of either drug. Moreover, the enhanced response of cisplatin or carboplatin in the presence of the combined inhibition of ATR and ATM was equivalent to that seen with ATRi alone. These findings are relevant as progressive accumulation of DNA lesions following acute platinum-treatment results in the formation of lethal DSBs and activation of apoptosis [4,33–35]. As ATM has been shown to play a key role in DSB repair, our data suggest that progressive DSB accumulation by cisplatin or carboplatin either circumvents or may not temporally align with ATM-associated DNA repair pathways. Cisplatin-mediated phospho-Chk2 (Thr68) and phospho-ATM (Ser1981) levels were reduced by ATM inhibition, though more markedly by ATR inhibition. However, low levels of phospho-Chk2 (Thr68) persisted with ATR inhibition alone, indicating that there may be an ATR-independent activity of ATM responsible for this basal level of phosphorylation of Chk2. This notion is supported by the observed complete loss of phospho-Chk2 (Thr68) following combined inhibition of ATR and ATM without any further augmentation of response over that seen with the combination of cisplatin and ATRi alone. We find increased levels of cleaved PARP1 and caspase 3 in GYN cancer cells treated with cisplatin and ATRi demonstrating that the enhancement in the response of the cisplatin and ATRi combination occurs, at least in part, through elevated apoptotic signaling. These data clarify the roles of ATR and ATM in response to genotoxic stressors that induce replicative stress, such as platinum drugs, and clearly point to opportunities for pharmacologic targeting of ATR to increase the therapeutic potential of platinum-based drugs in GYN cancers.

IR therapy is commonly used as a first- and second-line treatment in management of primary and recurrent endometrial and cervical cancer, and even in select settings in ovarian cancer. Our data show that ATM is activated in response to IR-mediated DNA damage. The phosphorylation status of ATM or Chk2 was only modestly reduced in irradiated cells in which ATR was pharmacologically inhibited. This finding recapitulates previous evidence demonstrating autoactivation of ATM, followed by ATM-dependent phosphorylation of Chk2, in response to IR-induced DNA damage [3,4]. The results here suggest that ATM activation in response to IR-induced DNA damage results in the activation of ATR, which in turn phosphorylates Chk1. This conclusion is supported by our data showing that inhibition of ATM in IR-treated cells did not result in a pronounced induction of phospho-Chk1 (Ser345) compared to cells exposed to IR alone. This interpretation is further supported by the observed complete loss of basal phospho-Chk1 (Ser345) levels in ATR inhibited GYN cancer cells exposed to IR, a loss that is not observed in IR exposed cells in which ATM-alone is inhibited. Further, the interplay between ATR and ATM is underscored by the loss of phospho-Chk1 (Ser345) and phospho-Chk2 (Thr68) in IR exposed cells in which both ATR and ATM are inhibited. In the context of Chk1 activation, ATM-dependent activation of ATR resulting from the generation of ssDNA during DSB resection has been previously described [36]. An assessment of radioresistance profiles in cervical cancer cell lines has shown that abundant levels of the p53 family member, p73α is associated with increased radiosensitivity [37].We show that pharmacologic inhibition of ATR or ATM augmented the response of IR in HELA and SIHA cervical cancer cell lines, both of which represent different levels of radioresistance arising from their low level of p73α expression [37], with further increases in IR sensitization by coordinate inhibition of both kinases. These data have translational potential to enhance the therapeutic response of IR (alone or with a radiation sensitizer such as cisplatin) with the combination of ATR and ATM inhibitors, particularly in the setting of newly diagnosed disease as well as persistent and recurrent disease in cervical, endometrial and ovarian cancer. These findings also support previous studies showing that ATM and ATR inhibition both induces sensitization to radiation and demonstrates further enhancement when inhibitors of ATR and ATM are combined with IR [17–19,21].

Although TP53 status has been shown to play a role in ATR inhibition and platinum resistance [7,27,38], in inhibition of ATM and sensitivity to IR [39], and in the activation of Chk1 and Chk2 [3,4], ATM and ATR signaling can occur through the p38MAPK/MK2 pathway in p53-deficient cells [40]. Our findings showing enhanced response of either platinum-based chemotherapy when combined with ATRi or IR when combined with inhibitors of ATR and ATM in GYN cancer cells harboring wild type (A2780, OVCAR3, HELA, SiHa) or mutant (A2780-CP20, KLE, HEC1B) TP53 [31,41] suggests the broad applicability of these combinations in the management of ovarian, endometrial, and cervical cancer.

Our findings support the hypothesis that inhibition of key DDR kinases, such as ATM and ATR, enhances the response of IR in human cervical, endometrial and ovarian carcinoma in vitro, independent of p53 status. Selective inhibition of ATR, but not ATM, synergized with platinum in cell line models in all three disease sites, independent of p53 status, and in cell lines characterized as platinum-resistant and sensitive. Combined inhibition of ATR and ATM did not enhance the response of platinum-agents above that seen with the ATRi alone. This divergent response is of central importance as it informs the selective use of ATR inhibitors, but not ATM inhibitors, with cisplatin- or carboplatin-based chemotherapy, and directs the combined use of ATR and ATM inhibitors with radiation or cisplatin-based chemoradiation in newly diagnosed and recurrent ovarian, endometrial and cervical cancers. Proactive prevention and reversal of resistance to chemotherapy and radiation represent real opportunities to reduce the mortality and morbidities associated with gynecologic cancers by exploiting the highly conserved DDR pathways to enhance the response of cancer therapies that induce DNA damage.

Supplementary Material

HIGHLIGHTS.

Pharmacologic inhibition of the ATR kinase, but not the ATM kinase, significantly enhances platinum drug efficacy in gynecologic cancer cells.

Inhibition of either ATR or ATM enhances IR efficacy in gynecologic cancer cells, with further enhancement achieved with co-inhibition.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Darcy Franicola for her assistance in generating the IR clonogenic plots.

Funding

This study was funded by an award from the United States Army Medical Research and Materiel Command (W81XWH-11-2-0131, all authors but CJB) and CA148644 (CJB) from the National Cancer Institute (CJB).

The opinions or assertions contained herein are the private views of the authors and are not to be construed as official or as reflecting the views of the Department of the Army, Department of the Air Force, Department of the Navy, or the Department of Defense.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2014.12.035.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors have no financial disclosures.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Barakat RR. Principles and practice of gynecologic oncology. 6th ed. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Heath; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel R, Ma J, Zou Z, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64:9–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.21208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ciccia A, Elledge SJ. The DNA damage response: making it safe to play with knives. Mol Cell. 2010;40:179–204. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roos WP, Kaina B. DNA damage-induced cell death: from specific DNA lesions to the DNA damage response and apoptosis. Cancer Lett. 2013;332:237–248. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2012.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhao H, Piwnica-Worms H. ATR-mediated checkpoint pathways regulate phosphorylation and activation of human Chk1. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:4129–4139. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.13.4129-4139.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu Q, Guntuku S, Cui XS, Matsuoka S, Cortez D, Tamai K, et al. Chk1 is an essential kinase that is regulated by Atr and required for the G(2)/M DNA damage checkpoint. Genes Dev. 2000;14:1448–1459. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen Z, Xiao Z, Gu WZ, Xue J, Bui MH, Kovar P, et al. Selective Chk1 inhibitors differentially sensitize p53-deficient cancer cells to cancer therapeutics. Int J Cancer. 2006;119:2784–2794. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith J, Tho LM, Xu N, Gillespie DA. The ATM-Chk2 and ATR-Chk1 pathways in DNA damage signaling and cancer. Adv Cancer Res. 2010;108:73–112. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-380888-2.00003-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arora S, Bisanz KM, Peralta LA, Basu GD, Choudhary A, Tibes R, et al. RNAi screening of the kinome identifies modulators of cisplatin response in ovarian cancer cells. Gynecol Oncol. 2010;118:220–227. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2010.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huehls AM, Wagner JM, Huntoon CJ, Karnitz LM. Identification of DNA repair pathways that affect the survival of ovarian cancer cells treated with a poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitor in a novel drug combination. Mol Pharmacol. 2012;82:767–776. doi: 10.1124/mol.112.080614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sultana R, Abdel-Fatah T, Perry C, Moseley P, Albarakti N, Mohan V, et al. Ataxia telangiectasia mutated and Rad3 related (ATR) protein kinase inhibition is synthetically lethal in XRCC1 deficient ovarian cancer cells. PLoS One. 2013;8:e57098. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abdel-Fatah T, Sultana R, Abbotts R, Hawkes C, Seedhouse C, Chan S, et al. Clinico-pathological and functional significance of XRCC1 expression in ovarian cancer. Int J Cancer. 2013;132:2778–2786. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Furgason JM, Bahassi el M. Targeting DNA repair mechanisms in cancer. Pharmacol Ther. 2013;137:298–308. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2012.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huntoon CJ, Flatten KS, Wahner Hendrickson AE, Huehls AM, Sutor SL, Kaufmann SH, et al. ATR inhibition broadly sensitizes ovarian cancer cells to chemotherapy independent of BRCA status. Cancer Res. 2013;73:3683–3691. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-0110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peasland A, Wang LZ, Rowling E, Kyle S, Chen T, Hopkins A, et al. Identification and evaluation of a potent novel ATR inhibitor, NU6027, in breast and ovarian cancer cell lines. Br J Cancer. 2011;105:372–381. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yazlovitskaya EM, Persons DL. Inhibition of cisplatin-induced ATR activity and enhanced sensitivity to cisplatin. Anticancer Res. 2003;23:2275–2279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Prevo R, Fokas E, Reaper PM, Charlton PA, Pollard JR, McKenna WG, et al. The novel ATR inhibitor VE-821 increases sensitivity of pancreatic cancer cells to radiation and chemotherapy. Cancer Biol Ther. 2012;13:1072–1081. doi: 10.4161/cbt.21093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gamper AM, Rofougaran R, Watkins SC, Greenberger JS, Beumer JH, Bakkenist CJ. ATR kinase activation in G1 phase facilitates the repair of ionizing radiation-induced DNA damage. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:10334–10344. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vavrova J, Zarybnicka L, Lukasova E, Rezacova M, Novotna E, Sinkorova Z, et al. Inhibition of ATR kinase with the selective inhibitor VE-821 results in radiosensitization of cells of promyelocytic leukaemia (HL-60) Radiat Environ Biophys. 2013;52:471–479. doi: 10.1007/s00411-013-0486-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pires IM, Olcina MM, Anbalagan S, Pollard JR, Reaper PM, Charlton PA, et al. Targeting radiation-resistant hypoxic tumour cells through ATR inhibition. Br J Cancer. 2012;107:291–299. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2012.265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fokas E, Prevo R, Pollard JR, Reaper PM, Charlton PA, Cornelissen B, et al. Targeting ATR in vivo using the novel inhibitor VE-822 results in selective sensitization of pancreatic tumors to radiation. Cell Death Dis. 2012;3:e441. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2012.181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Integrated genomic analyses of ovarian carcinoma. Nature. 2011;474:609–615. doi: 10.1038/nature10166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kandoth C, Schultz N, Cherniack AD, Akbani R, Liu Y, Shen H, et al. Integrated genomic characterization of endometrial carcinoma. Nature. 2013;497:67–73. doi: 10.1038/nature12113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pennington KP, Walsh T, Harrell MI, Lee MK, Pennil CC, Rendi MH, et al. Germline and somatic mutations in homologous recombination genes predict platinum response and survival in ovarian, fallopian tube, and peritoneal carcinomas. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20:764–775. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-2287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Turnell AS, Grand RJ. DNA viruses and the cellular DNA-damage response. J Gen Virol. 2012;93:2076–2097. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.044412-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wallace NA, Galloway DA. Manipulation of cellular DNA damage repair machinery facilitates propagation of human papillomaviruses. Semin Cancer Biol. 2014;26:30–42. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2013.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reaper PM, Griffiths MR, Long JM, Charrier JD, Maccormick S, Charlton PA, et al. Selective killing of ATM- or p53-deficient cancer cells through inhibition of ATR. Nat Chem Biol. 2011;7:428–430. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Toledo LI, Murga M, Zur R, Soria R, Rodriguez A, Martinez S, et al. A cell-based screen identifies ATR inhibitors with synthetic lethal properties for cancer-associated mutations. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2011;18:721–727. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hickson I, Zhao Y, Richardson CJ, Green SJ, Martin NM, Orr AI, et al. Identification and characterization of a novel and specific inhibitor of the ataxia-telangiectasia mutated kinase ATM. Cancer Res. 2004;64:9152–9159. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Skilling JS, Squatrito RC, Connor JP, Niemann T, Buller RE. p53 gene mutation analysis and antisense-mediated growth inhibition of human ovarian carcinoma cell lines. Gynecol Oncol. 1996;60:72–80. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1996.0014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yaginuma Y, Westphal H. Analysis of the p53 gene in human uterine carcinoma cell lines. Cancer Res. 1991;51:6506–6509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vavrova J, Zarybnicka L, Lukasova E, Rezacova M, Novotna E, Sinkorova Z, et al. Inhibition of ATR kinase with the selective inhibitor VE-821 results in radiosensitization of cells of promyelocytic leukaemia (HL-60) Radiat Environ Biophys. 2013;52:471–479. doi: 10.1007/s00411-013-0486-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Olive PL, Banath JP. Kinetics of H2AX phosphorylation after exposure to cisplatin. Cytometry B Clin Cytom. 2009;76:79–90. doi: 10.1002/cyto.b.20450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nowosielska A, Calmann MA, Zdraveski Z, Essigmann JM, Marinus MG. Spontaneous and cisplatin-induced recombination in Escherichia coli. DNA Repair (Amst) 2004;3:719–728. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2004.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nowosielska A, Marinus MG. Cisplatin induces DNA double-strand break formation in Escherichia coli dam mutants. DNA Repair (Amst) 2005;4:773–781. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2005.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jazayeri A, Falck J, Lukas C, Bartek J, Smith GC, Lukas J, et al. ATM- and cell cycle-dependent regulation of ATR in response to DNA double-strand breaks. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:37–45. doi: 10.1038/ncb1337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu SS, Chan KY, Leung RC, Law HK, Leung TW, Ngan HY. Enhancement of the radiosensitivity of cervical cancer cells by overexpressing p73alpha. Mol Cancer Ther. 2006;5:1209–1215. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-05-0451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sangster-Guity N, Conrad BH, Papadopoulos N, Bunz F. ATR mediates cisplatin resistance in a p53 genotype-specific manner. Oncogene. 2011;30:2526–2533. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Biddlestone-Thorpe L, Sajjad M, Rosenberg E, Beckta JM, Valerie NC, Tokarz M, et al. ATM kinase inhibition preferentially sensitizes p53-mutant glioma to ionizing radiation. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:3189–3200. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-3408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Reinhardt HC, Aslanian AS, Lees JA, Yaffe MB. p53-deficient cells rely on ATM- and ATR-mediated checkpoint signaling through the p38MAPK/MK2 pathway for survival after DNA damage. Cancer Cell. 2007;11:175–189. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.11.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Skilling JS, Sood A, Niemann T, Lager DJ, Buller RE. An abundance of p53 null mutations in ovarian carcinoma. Oncogene. 1996;13:117–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.