Abstract

In mammals, puberty is a process of acquiring reproductive competence, triggering by activation of hypothalamic kisspeptin (KiSS)-gonadotropin releasing hormone (GnRH) neuronal circuit. During peripubertal period, not only the external genitalia but the internal reproductive organs have to be matured in response to the hormonal signals from hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (H-P-G) axis. In the present study, we evaluated the maturation of male rat accessory sex organs during the peripubertal period using tissue weight measurement, histological analysis and RT-PCR assay. Male rats were sacrificed at 25, 30, 35, 40, 45, 50, and 70 postnatal days (PND). The rat accessory sex organs exhibited differential growth patterns compared to those of non-reproductive organs. The growth rate of the accessory sex organs were much higher than the those of non-reproductive organs. Also, the growth spurts occurred differentially even among the accessory sex organs; the order of prepubertal organ growth spurts is testis = epididymis > seminal vesicle = prostate. Histological study revealed that the presence of sperms in seminiferous tubules and epididymal ducts at day 50, indicating the puberty onset. The number of duct and the volume of duct in epididymis and prostate were inversely correlated during the experimental period. Our RT-PCR revealed that the levels of hypothalamic GnRH transcript were increased significantly on PND 40, suggesting the activation of hypothalamic GnRH pulse-generator before puberty onset. Studies on the peripubertal male accessory sex organs will provide useful references on the growth regulation mechanism which is differentially regulated during the period in andevrepogen-sensitive organs. The detailed references will render easier development of endocrine disruption assay.

Keywords: Male rat, Accessory sex organs, Peripubertal period, Differential growth spurts.

INTRODUCTION

Puberty is the end-point of complex series of early developmental events and the process of acquiring reproductive competence. Activation of hypothalamic KiSS-GnRH neuronal circuit triggers puberty initiation in mammals, then the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (H-P-G) hormonal axis eventually dictates the regular and precise control of reproductive process shown in adults (Navarro et al., 2007). Most information on the neuroendocrine basis of puberty onset is from studies on the female laboratory rodents such as mice and rats. Available evidence indicates that activation of the KiSS-GnRH neuronal circuit may be also crucial in male rodents (Navarro et al., 2004), though this is not so clear as in the case of female.

To enable fertilization successfully, not only the external genitalia but the internal reproductive organs have to be matured in response to the hormonal signals from H-P-G axis. In human, notable morphologic changes in size, shape, composition, and functioning of these body parts are defined as the development of secondary sex characteristics (Wheeler, 1991). In laboratory rodents, puberty onset has been defined by vaginal opening (V.O.) in female rats and by anogenital distance (AGD) in male rats, and these marks are widely employed in the evaluation of endocrine disruption assays (Kim et al., 2002; van Weissenbruch et al., 2005; Okahashi et al., 2005). Growth of accessory sex organs in the laboratory animals could be useful reference for such assays, but it has not been studied extensively yet.

In the present study, we evaluated the maturation of male rat accessory sex organs during peripubertal period using tissue weight measurement, histological analysis and RT-PCR assay.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

1. Animals

Timely pregnant Sprague-Dawley (SD) rats were obtained from DBL (Chungcheongbuk-do, Korea). The male offsprings were maintained in our animal facility under conditions of 12-h light/dark cycle (lights on at 07:00 h) and constant temperature of 22±1°C. Animal care and experimental procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal care and the use committee at the Sangmyung University (R-1301) in accordance with guidelines established by the Korea Food and devrepug Administration. The animals were weaned on day 21 postnatal day (PND) and were acclimatized at least for 4 days before the study commenced. Rats were sacrificed at 25, 30, 35, 40, 45, 50, and 70 PND. Organs were immediately measured the wet weight and then used for histology and RT-PCR.

2. Histology

Testis and the accessory sex organs were fixed 4% paraformaldehyde overnight at 4°C for 24 h, and then were serially dehydevrepated in graded ethanol and xylene. The fixed organs were dehydevrepated in ethanol (70%, 80%, 90%, 95%, 100%) and embedded in paraffin block. The organ blocks were cut at 4-5 μm using microtome (HM350S, MICROM, Germany). Sections were stained with hematoxylineosin and observed using a light microscope (BX51, Olympus, Japan).

3. Total RNA preparation and RT-PCR analyses

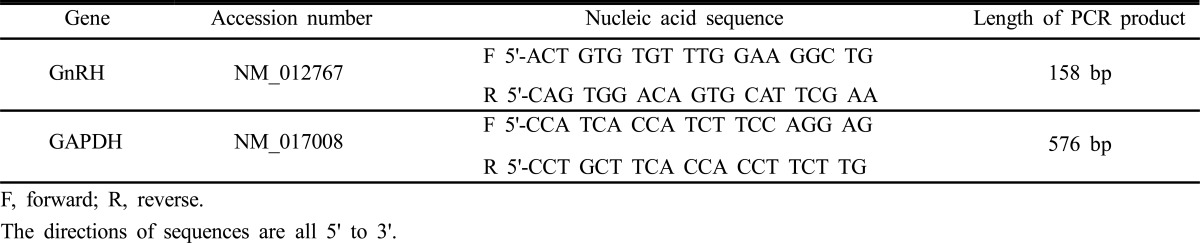

Total RNAs were isolated from hypothalamic samples using the single-step, acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenolchloroform extraction method. Total RNAs were used in RT-PCR reactions carried out with Maxime™ RT PreMix (iNtRON, Korea) and Accupower PCR Premix (Bioneer, Korea) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. As internal control, parallel amplification of GAPDH mRNA was carried out in each sample. Sequences of the rat GnRH and GAPDH gene primer sets are given in Table 1. PCR-generated cDNA fragments were resolved in 1.5% agarose gels and visualized by ethidium bromide staining. Quantification of the PCR products was performed by densitometric scanning using an image analysis system (Imager III-1D main software, Bioneer, Korea), and the values of the specific targets were normalized to those of GAPDH to express arbitrary units (A.U.) of relative expression.

Table 1.

Primer sets for semi-quantitative RT-PCR analyses

|

4. Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Data were expressed as means±S.E., and p value < 0.05 denoted the statistically significant difference.

3. RESULTS

To measure the body weights, organ weights and AGD, male rats were sacrificed at 25, 30, 35, 40, 45, 50, and 70 PND.

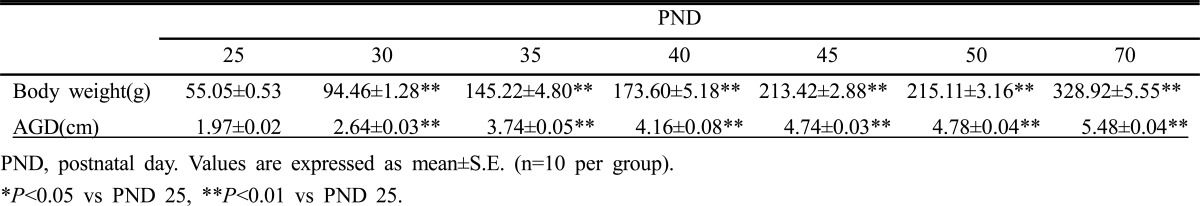

1. Measurements of body weights and anogenital distance

As outlined in Table 2, the body weight significantly increased 3.9 folds from 25 to 50 days of age (peripubertal period). When the data were combined at 5-day intervals from 25 to 50 days, the highest weight gain interval (rate) was on days 25-30 (71.6%) while the lowest weight gain interval was on days 45-50 (0.8%). Increments in AGD as a function of aging were in good correlation with body weight gains.

Table 2.

Body weights, anogenital distance (AGD) of PND 25, 30, 35, 40, 45, 50, 70 rats

|

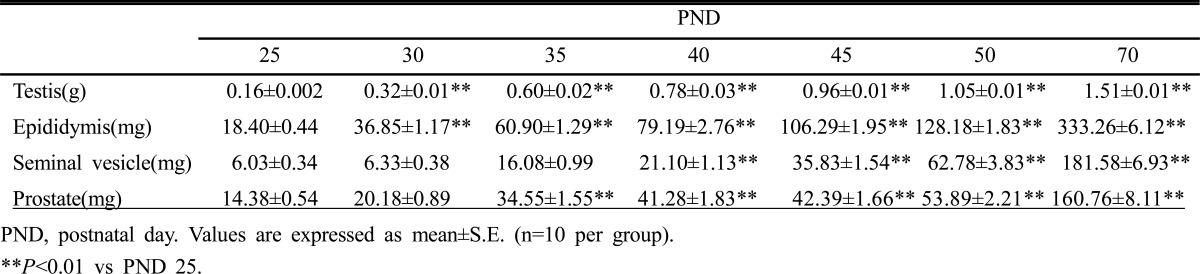

2. Measurements of reproductive organ weights

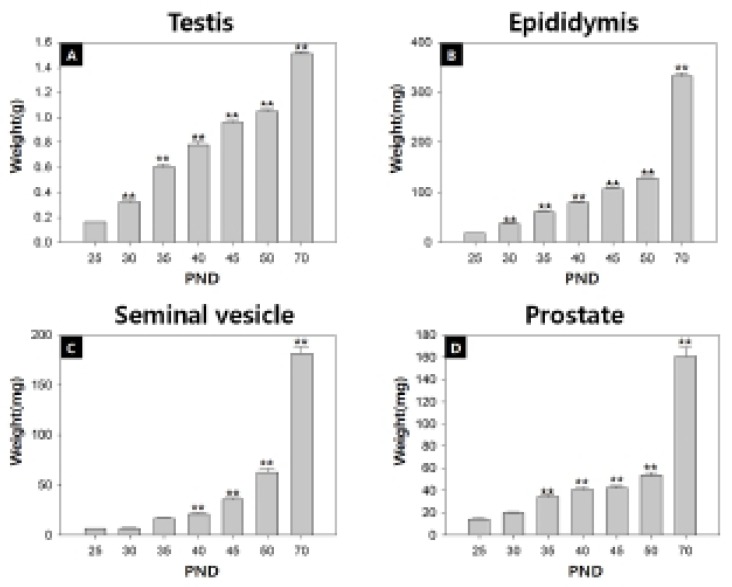

Fig. 1 and Table 2 show the temporal changes in reproductive organ weights in male rats during peripubertal period. From 25 to 50 days of age, the wet weights of testis, epididymis, seminal vesicle and prostate significantly increased 6.6, 7.0, 12.7 and 4.4 folds, respectively. The highest weight gain interval of testis was on days 25-30 (100.0%) while the lowest weight gain interval was on days 45-50 (9.4%). The highest weight gain interval of epididymis was on days 25-30 (100.3%) while the lowest weight gain interval was on days 45-50 (20.6%). The highest weight gain interval of seminal vesicle was on days 30-35 (154.0%) while the lowest weight gain interval was on days 25-30 (5.0%). The highest weight gain interval of prostate was on days 30-35 (71.2%) while the lowest weight gain interval was on days 40-45 (2.7%). So the order of prepubertal organ growth spurts is testis = epididymis > seminal vesicle = prostate. All the measured organs except testis exhibited postpubertal (days 50-70) growth spurt (epididymis, 160.0%; seminal vesicle, 137.8%; prostate, 151.7%).

Fig. 1.

Weights of the reproductive organs of PND 25, 30, 35, 40, 45, 50, 70 rats. PND, Postnatal day. Values are expressed as mean±S.E. (n=10 per group), **P<0.01 vs PND 25.

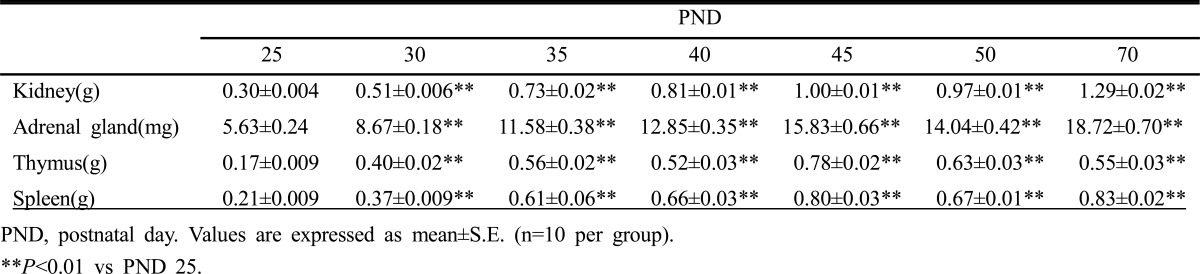

3. Measurements of non-reproductive organ weights

Table 3 demonstrates the temporal changes in non-reproductive organ weights in male rats during peripubertal period. From 25 to 50 days of age, the wet weights of kidney, adevrepenal gland, thymus and spleen significantly increased 3.2, 2.5, 3.7 and 3.2 folds, respectively. So the overall growth rates of non-reproductive organs during peripubertal period were much lower than the those of reproductive organs. The highest weight gain interval of kidney was on days 25-30 (70.0%) while the lowest weight gain interval was on days 45-50(–9.1%). The highest weight gain interval of adevrepenal gland was on days 25-30 (54.0%) while the lowest weight gain interval was on days 45-50 (–3.0%). The highest weight gain interval of thymus was on days 25-30 (135.3%) while the lowest weight gain interval was on days 45-50 (–19.2%). The highest weight gain interval of spleen was on days 25-30 (76.2%) while the lowest weight gain interval was on days 45-50 (–16.3%). All organs shown the prepubertal organ growth spurts on days 25-30, and weight loss prior to puberty onset (day 45-50). All the measured organs except thymus exhibited postpubertal (days 50-70) growth spurts which were much lower levels compared to those of reproductive organs (kidney, 33.0%; adevrepenal gland, 33.3%; spleen, 23.9%). At the same interval, thymus exhibited weight loss (–12.7%).

Table 3.

Weights of the reproductive organs of PND 25, 30, 35, 40, 45, 50, 70 rats

|

4. Histological changes in reproductive organs during peripubertal periods

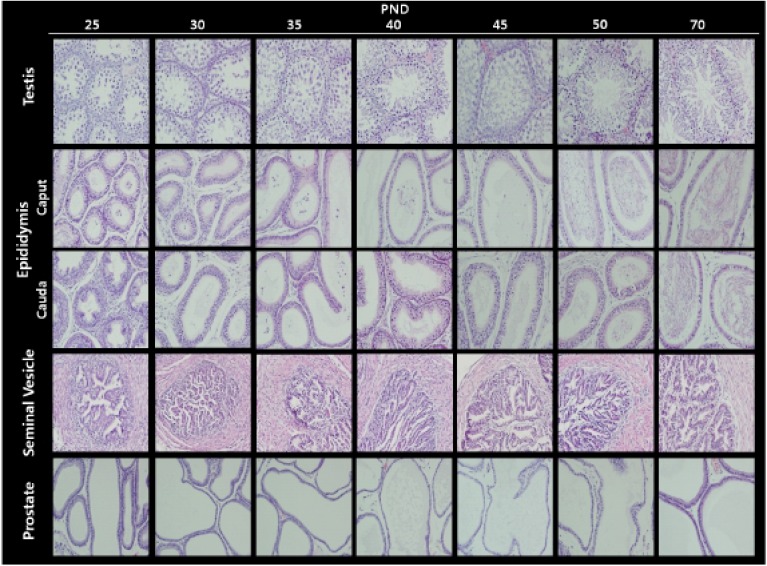

Fig. 2 illustrates the histological changes in the testis and male accessory sex organs during peripubertal periods. In the testis, the diameter of seminiferous tubules and Leydig cell populations gradually increased from day 25 to day 50. As expected, the elongated spermatids and the fully grown sperms were found at day 50. In the epididymis, the number of duct and the volume of duct were inversely correlated during the experimental period; gradual decrease in numbers and gradual increase in volumes. As shown in day 50 seminiferous tubules, sperms were found in day 50 epididymal ducts. In the seminal vesicle, the complexity of gland(irregularity and number of crypts) and lumen volume gradually increased from day 25 to day 50. As shown in epididymis, the number of duct and the volume of duct in prostate were inversely correlated during the experimental period (Table 4).

Fig. 2.

Microphotographs (objective 400×) of reproductive organs of PND 25, 30, 35, 40, 45, 50, 70 rats. Tissue sections were stained with hematoxylin-eosin and were observed using a light microscope.

Table 4.

Weights of the non-reproductive organs of PND 25, 30, 35, 40, 45, 50, 70 rats

|

5. Changes in hypothalamic GnRH expression levels during peripubertal periods

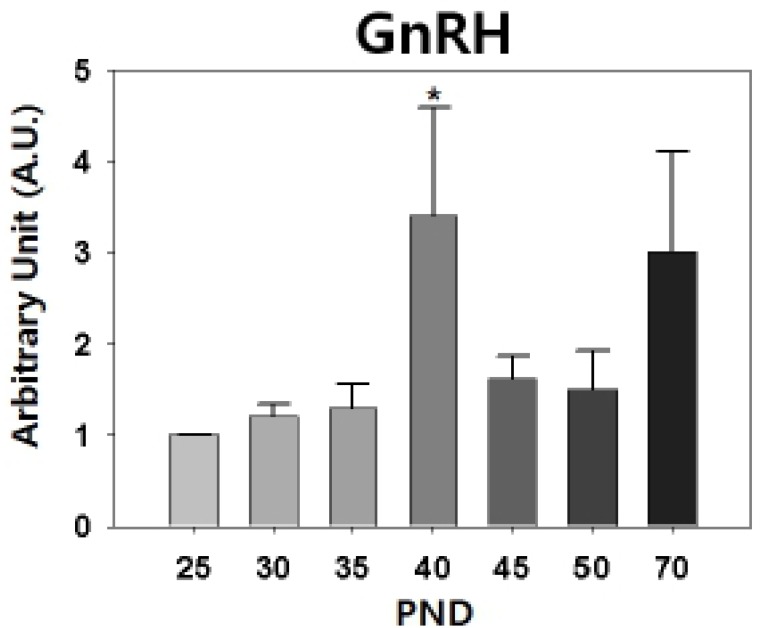

Our semi-quantitative RT-PCR revealed that the levels of hypothalamic GnRH transcript were increased significantly on PND 40 (PND 25 : PND 40 = 1.00±0 : 3.40±1.19, p<0.05, Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Semi-quantitative RT-PCR analysis of GnRH expressions in the hypothalami of PND 25, 30, 35, 40, 45, 50, 70 rats. Total RNAs were extracted, reverse-transcribed and the resulting cDNAs were applied to RT-PCR study. GAPDH was used as an internal control. Bars indicate the mean value (±S.E.M) of repeated experiments (n=6 per group). *Significantly different from PND 25, p<0.05.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we found that the rat accessory sex organs show differential growth patterns compared to those of non-reproductive organs. Firstly, the growth rate of the accessory sex organs were much higher than the those of non-reproductive organs. Secondly, the growth spurts occurred differentially even among the accessory sex organs; the spurts found in testis and epididymis between day 25 and day 30 and in seminal vesicle and prostate between day 30 and day 35. The delayed spurts in the secretory glands could be explained by andevrepogen responsiveness of these glands (Nishino et al., 2004; Yadav & Heemers, 2012). Concerning the prepubertal growth spurts own in non-reproductive organs, the presence of andevrepogen action in these organs is so far not clear though the organs express andevrepogen receptor (Stefani et al., 1994; Rossi et al., 1998; Sakabe et al., 1994; Dart et al., 2013). Further study will be helpful to understand the specific andevrepogen-sensitive organs maturation.

AGD, reflecting animal's andevrepogen exposure during the masculinization programming window (MPW), is a useful marker of puberty onset in male (Okahashi et al., 2005). MPW (e15.5-e18.5 in rats) was thought to be important in the origin of male reproductive disorders and in programming male reproductive organ size, and this window concept is extended since postnatal andevrepogen action may be also important to achieve this size (Macleod et al., 2010). Our data demonstrates that the rat AGD gradually increased from day 25 to day 45, then only 0.8% of increase was shown in days 45-50. Interestingly, body weight gain in days 45-50 was also 0.8%. The hold-ups of AGD increase and body weight gain, if combined, can be more precise criterion for puberty onset. AGD increase also shows good correlation with growth spurt pattern of andevrepogen-sensitive organs such as seminal vesicle and prostate. Like V.O. in female, measurement of AGD will be advantageous to study peripubertal physiology without sacrifice of animals.

Puberty onset in laboratory rats shows sexually dimorphic feature; rat V.O. occurs at PND 31-40 and epididymal sperms are detected from PND 50 (Rivest, 1991; Blystone et al., 2007). The delayed puberty onset in male rats seems to be resulted from the late activation of H-P-T hormonal axis than H-P-O hormonal axis. The mode and quantity of LH and FSH secretion in male and female hamster are different during the prepubertal period, the preceeding peak and higher serum gonadotropin levels are found in female (Vomachka & Greenwald, 1979). In hypothalamus, activation of female KiSS-GnRH neuronal circuit commences earlier than that of male (Navarro et al., 2004). Our RT-PCR data, the prepubertal peak of GnRH expression on PND 40, confirms that.

Studies on the peripubertal male accessory sex organs will provide useful references on the growth regulation mechanism which is differentially regulated during the period in andevrepogen-sensitive organs. The detailed references will render easier development of endocrine disruption assay. In this context, our data will be helpful for further intriguing study such as assessment of 'extended MPW hypothesis'.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was supported by a 2013 Research Grant from Sangmyung University.

REFERENCES

- Blystone CR, Lambright CS, Furr J, Wilson VS, Gray LE., Jr Iprodione delays male rat pubertal development, reduces serum testosterone levels, and decreases ex vivo testicular testosterone production. Toxicol Lett. 2007;174(1-3):74–81. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2007.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dart DA, Waxman J, Aboagye EO, Bevan CL. Visualising andevrepogen receptor activity in male and female mice. PLoS One. 2013;8(8):e71694. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0071694. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0071694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HS, Shin JH, Moon HJ, Kim TS, Kang IH, Seok JH, Kim IY, Park KL, Han SY. Evaluation of the 20-day pubertal female assay in Sprague-Dawley rats treated with DES, tamoxifen, testosterone, and flutamide. Toxicol Sci. 2002;67(1):52–62. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/67.1.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macleod DJ, Sharpe RM, Welsh M, Fisken M, Scott HM, Hutchison GR, devrepake AJ, van den devrepiesche S. Andevrepogen action in the masculinization pro- gramming window and development of male reproductive organs. Int J Andevrepol. 2010;33(2):279–287. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2605.2009.01005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarro VM, Castellano JM, Fernández-Fernández R, Barreiro ML, Roa J, Sanchez-Criado JE, Aguilar E, Dieguez C, Pinilla L, Tena-Sempere M. Developmental and hormonally regulated messenger ribonucleic acid expression of KiSS-1 and its putative receptor, GPR54, in rat hypothalamus and potent luteinizing hormone-releasing activity of KiSS-1 peptide. Endocrinology. 2004;145(10):4565–4574. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-0413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarro VM, Castellano JM, García-Galiano D, Tena-Sempere M. Neuroendocrine factors in the initiation of puberty: the emergent role of kisspeptin. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2007;8(1):11–20. doi: 10.1007/s11154-007-9028-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishino T, Wedel T, Schmitt O, Bühlmeyer K, Schönfelder M, Hirtreiter C, Schulz T, Kühnel W, Michna H. Andevrepogen-dependent morphology of prostates and seminal vesicles in the Hershberger assay: evaluation of immunohistochemical and morphometric parameters. Ann Anat. 2004;186(3):247–253. doi: 10.1016/S0940-9602(04)80011-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okahashi N, Sano M, Miyata K, Tamano S, Higuchi H, Kamita Y, Seki T. Lack of evidence for endocrine disrupting effects in rats exposed to fenitrothion in utero and from weaning to maturation. Toxicology. 2005;206(1):17–31. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2004.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivest RW. Sexual maturation in female rats: hereditary, developmental and environmental aspects. Experientia. 1991;47(10):1027–1038. doi: 10.1007/BF01923338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi R, Zatelli MC, Valentini A, Cavazzini P, Fallo F, del Senno L, degli Uberti EC. Evidence for andevrepogen receptor gene expression and growth inhibitory effect of dihydevrepotestosterone on human adevrepenocortical cells. J Endocrinol. 1998;159(3):373–380. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1590373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakabe K, Kawashima I, Urano R, Seiki K, Itoh T. Effects of sex steroids on the proliferation of thymic epithelial cells in a culture model: a role of protein kinase C. Immunol Cell Biol. 1994;72(3):193–199. doi: 10.1038/icb.1994.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefani S, Aguiari GL, Bozza A, Maestri I, Magri E, Cavazzini P, Piva R, del Senno L. Andevrepogen responsiveness and andevrepogen receptor gene expression in human kidney cells in continuous culture. Biochem Mol Biol Int. 1994;32(4):597–604. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Weissenbruch MM, Engelbregt MJ, Veening MA, Delemarre-van de Waal HA. Fetal nutrition and timing of puberty. Endocr Dev. 2005;8:15–33. doi: 10.1159/000084084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vomachka AJ, Greenwald GS. The development of gonadotropin and steroid hormone patterns in male and female hamsters from birth to puberty. Endocrinology. 1979;105(4):960–966. doi: 10.1210/endo-105-4-960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler MD. Physical changes of puberty. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 1991;20(1):1–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yadav N, Heemers HV. Andevrepogen action in the prostate gland. Minerva Urol Nefrol. 2012;64(1):35–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]