Abstract

Inflammation is a part of the host defense system, which provides protection against invading pathogens. However, it has become increasingly clear that inflammation can be evoked by endogenous mediators through Toll-like receptors (TLRs) to enhance tumor progression and metastasis. Here, we discuss the roles of TLR-mediated inflammation in tumor progression and the mechanisms through which it accomplishes this pathogenic function.

Keywords: Toll-like receptor, inflammation, TNF-α, tumor progression, metastasis

Introduction

A link between chronic inflammation and cancer has been suspected since the 19th century, when Rudolf Virchow first noted that malignant tumors arise at regions of chronic inflammation and contain inflammatory infiltrates.1–5 Recent studies have clearly shown that chronic inflammation increases the risk of tumor development and progression.6 However, the source of inflammation in tumors that are not associated with chronic infection remains poorly understood.

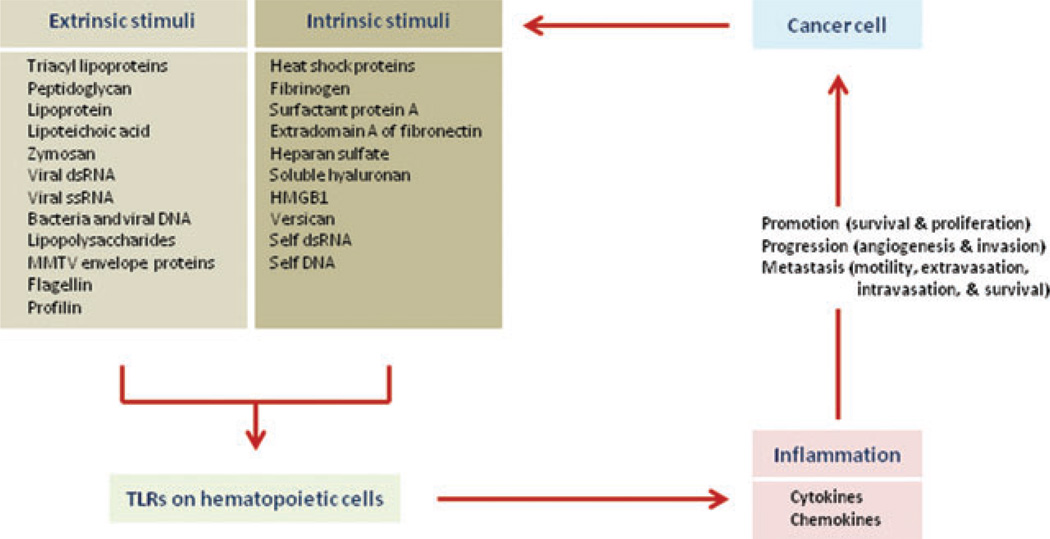

Inflammation is a part of the host defense system originally evolved to protect organisms against invading pathogens. However, it has become apparent that inflammation can also be evoked by intrinsic mediators (endogenous mediators) in the absence of infection (Fig. 1). For instance, it has been established that necrotic cell death, resulting in the release of molecules that are normally stored within cells, such as high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) and interleukin (IL)-1α, acts as a potent inflammatory stimulus.7,8 Toll-like receptors (TLRs), which recognize both extrinsic and intrinsic mediators, play key roles in the initiation of inflammation and innate immune responses and the eventual activation of adaptive immunity.9,10 Interestingly and importantly, many studies have shown a correlation between TLR signaling and tumor progression and metastasis, and endogenous mediators, including HMGB1, have been implicated in the triggering of tumor-associated inflammation.7

Figure 1.

Inflammatory mediators in tumor progression and metastasis. Endogenous molecules released by injured and necrotic cells might activate TLRs expressed on hematopoietic cells, including macrophages, and these activated cells release inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, which lead tumor progression and metastasis.

Here, we will discuss and mechanistically explain the roles of endogenous mediators and TLR-mediated inflammation in tumor promotion, progression, and metastasis.

Endogenous and exogenous inflammatory mediators and tumorigenesis

Under normal conditions, programmed cell death is tightly regulated by the adenosine triphosphate (ATP) concentration of the cell and the balanced expression of antiapoptotic and proapoptotic proteins.11 When it does occur, apoptotic cell death results in cell condensation, nuclear fragmentation, and formation of apoptotic bodies that are rapidly cleared by phagocytic cells without release of cellular constituents to the extracellular milieu.11 By contrast, necrotic cell death, which occurs upon injury or upon shortage of oxygen and nutrients in the core of solid tumors, results in the release of normal cellular constituents into the extracellular space.12 Some molecules normally kept within cells act as potent inflammatory mediators through activation of TLRs or other receptors.13 We refer to such molecules as endogenous inflammatory mediators and one notable example is HMGB1.7 Several studies showed that HMGB1, normally a component of chromatin, interacts with TLR2, TLR4, and receptor for glycation end-products (RAGE), thereby triggering inflammation through the production of chemokines and cytokines that stimulate tumor growth, progression, and metastasis.8,14 Several cancers, including breast cancer, colon cancer, melanoma, pancreatic cancer, and prostate cancer were found to contain higher amounts of HMGB1 than normal tissues, suggesting a close link between the necrotic release of HMGB1, inflammation, and tumor progression and/or metastasis.14 Other endogenous mediators include S100 proteins in melanoma cells, which also can trigger inflammation and enhance tumor growth.15 Heat shock proteins (HSPs) are also well known as potent activators of innate immune signaling.16,17 HSPs such as Hsp60, Hsp70, and Hsp90 can induce expression of proinflammatory cytokines, including tumor necrosis factor (TNF), IL-1, IL-6, and IL-12, and stimulate the release of nitric oxide (NO) and C–C chemokines by monocytes, macrophages, and dendritic cells (DCs) via TLR-dependent mechanisms.18 HSPs also induce the maturation of DCs as demonstrated by upregulation of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) classes I and II molecules, and co-stimulatory molecules such as CD80 and CD86.16,17 There is clear clinical evidence showing a positive correlation between elevated HSP amounts and metastatic tumor progression.19,20 Similar proinflammatory effects have also been reported for other cellular constituents, some of which are secreted by live cells, including fibrinogen,21 surfactant protein A,22 domain A of fibronectin,23,24 heparan sulfate,25 short hyaluronan (HA) fragments (soluble HA),26 (β-defensin 2-lymphoma antigen idiotype sFv fusion protein,27 tRNA synthase,28 and versican.29,30 Nucleic acids released from necrotic cancer cells or by injured normal cells can also serve as inflammatory mediators that activate nucleic acid sensing TLRs, such as TLR3, 7, 8, and 9.31 There is also a report showing potent induction of inflammation by a complex of DNA and HMGB1 released by necrotic cells.7 Importantly, the absolute amounts of circulating DNA in serum and plasma appear to have diagnostic and prognostic significance for various cancers.32 The integrity of circulating DNA, measured as the ratio of longer to shorter DNA fragments, is higher in cancer patients than in normal individuals.33 In general, there is growing evidence that intrinsic TLR activators that are released during tumor progression, by both dying and living cancer cells, may be responsible for the persistent low-grade inflammation found in the tumor microenvironment.34 However, a full understanding of the roles played by most of these intrinsic mediators in tumor progression and metastasis is yet to be achieved.

Molecules derived from invading microorganisms such as bacteria, fungi, and viruses are the major extrinsic inflammation-inducing molecules. Such molecules are recognized by TLRs and other pathogen-recognition receptors. Approximately 15% of all cancers worldwide develop in the context of chronic infections, including gastric cancer (Helicobacter pylori), cervical cancer (Human papilloma virus), liver cancer (Hepatitis virus B and C), and hematologic malignancies (Cytomegalovirus and Epstein-Barr virus).35 Mediators released by infectious organisms also cause chronic inflammation that promotes tumor development and progression.36

Link of TLR-mediated inflammation and tumor development

Toll-like receptors (TLRs), the mammalian homologues of the Drosophila Toll protein, are evolutionarily conserved pattern recognition receptors.9,37 Eleven TLRs (TLR1 to TLR11) have been identified in humans so far. They are expressed in different types of immune cells and are located either at the plasma membrane or within early endosomes. TLRs play key roles in activation of inflammatory responses and host defense against invading pathogens by virtue of their ability to recognize conserved molecular motifs of microbial and viral origins, referred to as pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs).38–40 TLRs may also be activated by a number of intrinsic agonists produced by mammalian cells, such as HMGB18 and HSPs.18 Any TLR agonist, either microbial or mammalian in origin, can trigger the activation of myeloid and lymphoid cells as well as stimulate DC maturation.7,41–43

The first mammalian TLR to be identified, TLR4, is the receptor for lipopolysaccharide (LPS), a cell wall component of Gram-negative bacteria.40 Since then different TLRs were found to recognize a wide range of microbial components: TLR1 (in association with TLR2) being activated by tri-acyl lipopeptides;44 TLR2 by lipoproteins and peptidoglycans;45 TLR3 being a receptor for double-stranded RNA;46 TLR5 being a receptor for flagellin;47 TLR6 (in association with TLR2) being activated by di-acyl lipopeptides;48 TLR7 and TLR8 being receptors for single-stranded RNA;49 and TLR9 being a receptor for nonmethylated CpG DNA.50 No ligands have been identified as yet for TLR10 and TLR11. Upon binding of their cognate ligands, the TLRs trigger several different intracellular signal transduction pathways that culminate in induction of proinflammatory cytokines, chemokines, as well as interferons (IFNs).39,51,52

Several studies have shown a statistically significant correlation between elevated TLR protein expression in tumor and clinical grade. For example, pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma and colorectal cancers expressing higher amounts of TLR4 show larger tumor size, lymph node, and liver metastasis, respectively, and reduced overall survival rate.53,54 However, it is not clear whether the above-mentioned patients exhibit more inflammation; but most likely, upregulation of TLR expression should increase responsiveness to endogenous TLR agonists produced by cancer and noncancer cells alike, which should alter the tumor environment and overall disease condition. In colon, liver, and lung tumors, which are exposed to bacteria and bacterial-derived production, elevated TLR expression should also enhance the response to microbial-derived TLR agonists. Such factors should be considered when designing improved personalized treatments for such patients.

Inflammation and cancer

Inflammation and early tumor promotion

Cancer is a chronic disease that is caused by defective genome-surveillance and aberrant signal-transduction mechanisms.55 If infection and inflammation enhance tumor development they could do so through effects on cell cycle control, cell survival, or genomic surveillance. Chronic inflammation was proposed to act as an initiating factor in malignancy through the generation of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (ROS and RNS), which subsequently leads to DNA damage.56 Although persistent inflammation certainly results in excessive and prolonged generation of ROS and RNS by resident and infiltrating inflammatory cells, there is little evidence so far that this may directly result in induction of oncogenic mutations. One of the enzymes involved in free radical generation is the inducible form of nitric oxide synthetase, iNOS, which is frequently expressed not only in inflamed tissues, but also in premalignant lesions and tumor tissues.57,58 However, as mentioned earlier, there is little genetic evidence that chronic inflammation acts as a direct tumor initiator rather than a tumor promoter.59 Furthermore, a mouse mutant defective in the repair of oxidative DNA lesions was found to be highly susceptible to induction of chronic inflammation, while exhibiting only a very small increase in oncogenic mutations and tumor load.60 In addition, chronic low-grade inflammation is immunologically distinct from acute inflammation elicited by infections. The latter is characterized by CD8+ effector T cells, which have a central role in tumor-associated antigen (TAA)-specific immunity and thus can eliminate microbes as well as tumors.61 Activated natural killer (NK) cells also stimulate the maturation of DCs and facilitate antitumor immunity. Chronic inflammation lacks these functions, which is why it may result in net stimulation of tumor growth through a variety of mechanisms, including the production of cytokines that act as growth factors.62 Furthermore, it is clear that not every form of chronic inflammation can enhance tumor development. Usually, the site in which chronic inflammation occurs is of great importance, and it seems that only in tissues that are also exposed to environmental carcinogens, such as the colon or the liver, can chronic inflammation strongly enhance tumor development.63

Inflammatory infiltrates in tumors and their significance

Although inflammation at certain sites can promote tumor development, it is also clear that primary oncogenic events, such as Ras oncogene activation, can trigger inflammation through effects on expression of various proinflammatory genes, especially those that code for chemokines.4,64 Thus, primary oncogenic events in epithelial cells can establish an inflammatory microenvironment even in tumors that do not develop in the context of chronic inflammation, and this microenvironment can have a major impact on the course of tumor progression.3,65 The inflammatory microenvironment of neoplastic tissues is characterized by presence of infiltrating cells of hematopoietic origin, such as leukocytes, macrophages, dendritic cells, mast cells, and T cells.66 However, it is still being debated whether activation of the innate immune system, whose major manifestation is inflammation, contributes to tumor promotion and progression or whether it enhances tumor surveillance and elimination.67 It was suggested that whereas acute inflammation may inhibit malignancy through activation of T and NK cells, and induction of death cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α–related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL), chronic low-grade inflammation promotes carcinogenesis through activation of macrophages and mast cells that produce tumor-promoting cytokines, such as IL-6, which enhance the proliferation and survival of cancer cells 3,65,68

Pollard and coworkers have shown that macrophages, major components of the inflammatory microenvironment of most tumors, are important to the growth and progression of mammary carcinomas by using macrophage colony stimulating factor (MCSF)-1–deficient mice.65 Such tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) can promote tumor development and metastatic progression through multiple mechanisms, including the inhibition of antitumor T cell-dependent immunity through production of immunosuppressive indoleamine dioxygenase metabolites, inhibition of DC maturation via secretion of IL-10, transforming growth factor (TGF)-β and M-CSF, as well as attraction of T regulatory (Treg) cells to the tumor.66 In addition, TAMs produce numerous cytokines, for example, TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6, chemokines, for example, IL-8, macrophage inflammatory protein (MIP) 1 and MIP2, and enzymes that catalyze production of inflammatory mediators, such as cyclooxygenase (COX)-2. All of these act to support survival, proliferation, invasiveness, motility, and metastasis of cancer cells. It is now evident that TNF-α, initially heralded for its anticancer activity,69 can actually serve as a tumor-promoting factor,70,71 and a similar function has been demonstrated for IL-6.72 TAMs also secrete matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and proangiogenic factors such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) that stimulate invasion of surrounding tissues and angiogenesis, as well as ROS and RNS that enhance genomic instability, cell proliferation, and tumor progression.73,74

The capability to express distinct functional programs in response to different microenvironmental signals is a key feature of macrophages, which are typically displayed during pathological conditions such as infections and cancer.75–77 In response to cytokines and microbial products, mononuclear phagocytes express specialized programs, manifested by different cytokine production profiles that are referred to as M1 and M2. Classically activated M1 macrophages are induced by IFN-γ, either alone or in concert with microbial stimuli, for example, LPS, or by combinations of cytokines, for example, TNF-α and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF). On the other hand, IL-4 and IL-13 induce alternatively activated M2 macrophages.78 M1 and M2 macrophages display a number of distinct features. M1 macrophages are characterized by high capacity to present antigens, high IL-12 and IL-23 production, and consequent activation of type I T cells that may have cytotoxic ability toward tumor cells.79 On the other hand, M2 macrophages have poor antigen-presenting capacity; have an IL-12low IL-10high cytokine expression phenotype; suppress inflammatory responses as well as Th1 adaptive immunity; actively scavenge cellular debris; and promote wound healing, angiogenesis, and tissue remodeling.76 Earlier studies with TNF-α–stimulated macrophages or TAMs indicated that under certain conditions these cells display cytotoxic functions against cancer cells.80,81 However, it is clear that in the absence of M1-orienting signals, TAMs promote cancer cell growth in vitro and in vivo partially through the release of angiogenic and lymphoangiogenic factors that promote lymphatic metastasis of cancer cell.77,81,82 Importantly, in many human tumors a high TAM content has been associated with poor prognosis.1,66,82

Myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), which can be recruited by IL-6 and IL-1β, are also an important component of the tumor microenvironment.54 MDSCs have been recently recognized as critical mediators of cancer progression. They inhibit the antitumor immune responses by release of arginase, NO2, and TGF-β.83,84 Plasmacytoid DCs that express CXCR4 are also recruited into the tumor microenvironment and potentiate IL-10 production by T cells and therefore act as immunosuppressants.85 Vascular DCs in the tumor microenvironment increase tumor vascularization and subsequent metastasis.86 Cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) are another important component of the tumor stroma and the inflammatory microenvironment. Unlike normal fibroblasts, CAFs are perpetually activated and can produce a variety of chemokines.87 The origin of CAF is not well understood, but they appear to be as important as immune cells in the tumor microenvironment.88 A recent study proposed that TGF-β has a crucial role in CAF activation.89 Activated CAFs promote the proliferation and progression of cancer cells through the production of growth factors and metalloproteinases,90 and can attract immune and inflammatory cells through chemokine production.91 Therefore, a TLR-related increase in TGF-β production might lead to recruitment and activation of CAFs in the tumor microenvironment.

The mechanisms that lead to inflammatory cell recruitment and activation within tumors to promote growth, angiogenesis, and metastatic progression are not fully understood, and need to be further investigated. However, in various models of cancer metastatic progression, the appearance of distant site metastasis was found to correlate with infiltration of the primary tumors with various immune and inflammatory cells. For instance, immune cells that express high levels of the TNF family members RANK ligand (RANKL) and lymphotoxin (LT) α are likely to promote metastatic progression in the TRAMP model of prostate cancer.92 RANKL was also found to stimulate the metastatic growth of mouse and human mammary carcinomas (W. Tan et al., in preparation), and clinical trials suggest that it is also of importance for bone metastasis.93 Such findings suggest that activation of genetically unaltered myeloid and lymphoid cells in the tumor microenvironment can provide a major impetus to tumor growth, survival, angiogenesis, and metastasis.3,65,68 Our current mechanistic understanding of such processes will be discussed later.

Mechanisms

The inflammatory microenvironment

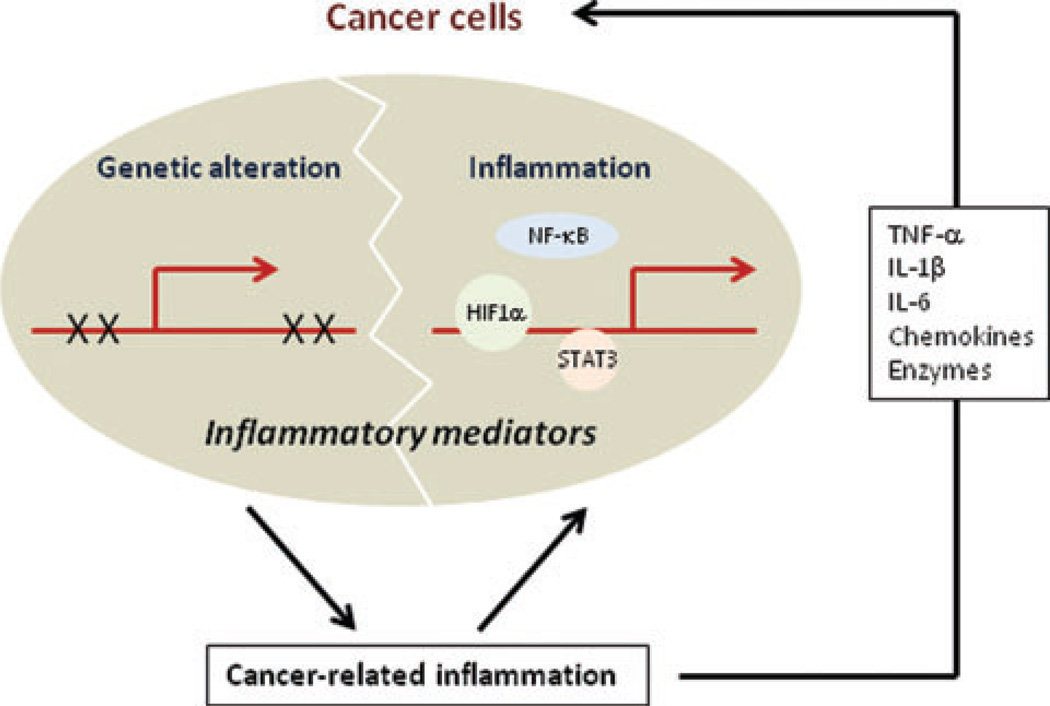

Cancer and inflammation can be linked by two pathways; one is dependent on an underlying inflammatory activation and the other one is not (Fig. 2). The latter pathway is activated by the genetic events that cause neoplasia, which include activation of proto-oncogenes by mutations, chromosomal rearrangements, gene amplification, and genetic and epigenetic inactivation of tumor-suppressor genes. Genetically transformed cancer cells produce different mediators, which generate an inflammatory microenvironment even in tumors without an underlying inflammatory condition or infection, which include breast cancer. For instance, it was shown that h-Ras activation can result in increased production of the chemokine CXCL-8/IL-8 that recruits inflammatory cells that produce factors that stimulate the growth of malignant, h-Ras–transformed cells.64 The inflammation-dependent pathway, on the other hand, is based on underlying infections or chronic inflammatory and autoimmune diseases that generate an inflammatory microenvironment rich in cytokines and chemokines that provide a “fertile soil” within which genetically transformed cancer cells can survive and rapidly proliferate (e.g., colorectal and gastric cancers). The two pathways converge through activation of transcription factors, such as NF-κB, signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) 3 and hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) 1α.5,94 Within the malignant cell these transcription factors control expression of prosurvival genes, proangiogenic factors, and MMPs. Within inflammatory cells, NF-κB controls the production of cytokines and chemokines that act on the malignant cells, as well as directing the production of proangiogenic factors, such as VEGF.95 Interestingly, NF-κB is also required for full activation of HIF1α through its effect on transcription of the Hif1α gene.96 In addition to its critical role in activation of the proangiogenic program, HIF1α is important for the survival and activation of macrophages and other myeloid cells in the oxygen-poor environment of primary tumors.97 The concerted action of these transcription factors and the reciprocal interactions between malignant cells and inflammatory cells are likely to play a key role in formation of the inflammatory microenvironment typical of advanced tumors.

Figure 2.

Cancer-related inflammation (genetic alteration versus inflammation). Genetically altered cancer cells may produce different inflammatory mediators that establish an inflammatory microenvironment within tumors to promote tumor progression and metastasis.

Chemokines, initially defined as soluble factors that control the directional migration of leukocytes during states of inflammation and immune responses, can be produced by multiple cell types including most human neoplastic cells98 and play an important role in formation of the inflammatory microenvironment.2 The importance of chemokines in malignant progression was first reported using mice lacking T or NK cell functions, which still exhibited typical inflammatory infiltrates when challenged with tumors, suggesting that neoplastic cells either produce chemotactic factors that recruit inflammatory cells or induce the expression of such factors in nearby host cells.99 Importantly, certain tumor cells not only use chemokines to recruit inflammatory cells but also directly respond to these factors to further enhance their own growth and survival.100–102

Inflammatory mediators and their effects on malignant cells

The microenvironment of human and murine cancers is rich in cytokines, chemokines, and enzymes that produce inflammatory mediators, which collectively modulate cancer cell migration, invasion, and metastasis (Fig. 2).1,2

Of particular interest among these factors is TNF-α, a pivotal cytokine in inflammatory reactions. Induced by a wide range of pathogenic stimuli, TNF-α induces expression of other inflammatory mediators and proteases that orchestrate inflammatory responses.103 High doses of extrinsic TNF-α cause hemorrhagic necrosis and can stimulate antitumor immunity.104 However, there is increasing evidence that low amounts of TNF-α are produced by malignant and stromal cells within tumors and act as an endogenous tumor promoter.103 TNF-α is frequently detected in human cancers, being produced by malignant epithelial cells, as in ovarian and renal cancers, or by stromal cells, as in breast cancer.103 A tumor-promoting function for TNF-α was first demonstrated in two-stage chemical skin carcinogenesis and later in other cancer models.70,103 The absence of TNF-α, or its type I receptor TNFR1, confer resistance to skin carcinogenesis.105 TNF-α does not influence the initiation phase of carcinogenesis; DNA adducts and initiating h-Ras mutations occur in its absence. However, TNF-α production by keratinocytes is a critical component of tumor promotion by phorbol esters, which act via PKCα and an AP-1–dependent intracellular signal transduction pathway to induce TNF-α gene expression in keratinocytes.70 In the absence of TNF-α, the epithelial production of other cytokines and MMPs that are thought to be important in skin carcinogenesis, and tumor–stroma communication is either delayed and/or completely absent. Similarly, in a model of chemically-induced liver cancer, TNF-α production by hepatocytes has been implicated in tumor development.106 However, in a different model of liver cancer induced by chronic inflammation rather than a chemical carcinogen, TNF-α was found to be produced by the tumor stroma.107 Nonetheless, stromal TNF-α serves as an important tumor promoter. In this system, as well as in inflammation-induced colon cancer,108 tumor promotion depends on activation of NF-κB transcription factor. Selective inhibition of NF-κB in hepatocytes, or inhibition of TNF-α production by neighboring parenchymal cells, induced programmed cell death of transformed hepatocytes and subsequently reduced the incidence of hepatocellular carcinomas.107 Tumor TNF-α production is associated with a poor prognosis, loss of hormone responsiveness, and cachexia. An interesting genetic link between TNF-α and malignancy was identified in renal cell cancer, where the pVHL tumor suppressor gene is a translational repressor of TNF-α.109 Despite its ability to induce necrosis at high concentrations in certain cell types, TNF-α frequently acts as a survival factor due to its ability to promote NF-κB activation.71,107 TNF-α also increases vascular permeability and can stimulate the migration and extravasation or intravasation of cancer cells.110 In certain cases, TNF-α can also act as a growth factor.71 Likewise, ablation of IKKβ, a protein kinase critical for NF-κB activation, in intestinal epithelial cells was found to prevent the development of colitis-associated cancer (CAC) induced by the procarcinogen azoxymethane (AOM) and repeated cycles of dextran sulfate sodium (DSS), which induced colonic inflammation.108 Deletion of myeloid cell IKKβ also interfered with CAC development, but in this case it mostly reduced tumor size rather than tumor multiplicity. More recent work has shown that part of the tumor-promoting function of myeloid cell IKKβ is mediated through induction of the proinflammatory cytokine IL-6.72 TNF-β also promotes the development of CAC,111 and during colitis macrophage-enriched lamina propria mononuclear cells produce high amounts of TNF-α.31

Another key inflammatory cytokine, IL-1β also increases tumor invasiveness and metastasis, primarily by promoting production of angiogenic factors by stromal cells in the tumor microenvironment.112–114 IL-1β is mainly produced by myeloid cells where its synthesis is subject to intricate transcriptional and posttranscriptional control.115 Curiously, although NF-κB stimulates IL-1β gene transcription it inhibits the processing of pro-IL-1β to IL-1β.116 A related cytokine is IL-1α, which, unlike IL-1β, is mainly secreted by epithelial cells undergoing necrosis.8,117 IL-1 receptor activation by either form of IL-1 can lead to induction of IL-6. Curiously, blood levels of IL-6 are elevated with age,118,119 due to loss of inhibitory sex steroids.120 Loss of hormonal suppression of IL-6 production has been implicated in the pathogenesis of several chronic diseases,121 including B cell malignancies, renal cell carcinoma, and prostate, breast, lung, colon, and ovarian cancers.122 Many of these cancers appear with old age, when circulating IL-6 is high. In multiple myeloma, for example, IL-6 promotes the survival and proliferation of cancer cells via activation of STAT3 and extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) signaling.123 Using a combination of in vitro experiments and mouse models, we showed that IL-1α released by necrotic hepatocytes can induce the secretion of IL-6 by resident liver macrophages (Kupffer cells).8 In turn, IL-6 acts to promote chemically-induced liver carcinogenesis most likely through activation of the prooncogenic transcription factor STAT3.124

A range of inflammatory enzymes, including COX-2, that catalyzes the conversion of arachidonic acid to prostaglandins (PG) are also induced by cytokines. COX-2 is highly expressed in colorectal, gastric, esophageal, breast, and prostate cancers and in non-small-cell squamous lung carcinoma.125 COX-2-produced PGE2 increases tumor invasion and metastasis and enhances production of IL-6, IL-8, VEGF, iNOS, MMP-2, and MMP-9.126 Selective and nonselective COX-2 inhibition exerts chemo-preventive and antimetastatic activity in a variety of human cancers.127 Most likely, this activity is due to disruption of the inflammatory microenvironment.

Inflammation and lung cancer metastasis

Lewis lung carcinoma (LLC), a commonly used mouse lung cancer cell line, has strong metastatic activity, and upon tail vein injection or subcutaneous implantation LLC metastasizes to lungs and to a lesser extent to liver, lymph nodes, adrenal glands, and bone.128,129 LLC cells grown as a primary subcutaneous tumor induce the expression of MMP-9 by lung endothelial cells, and this was proposed to somehow “precondition” the lung to become a preferential site for LLC cells to migrate into and establish metastatic growths.128 Induction of MMP-9 expression in the lung by subcutaneous LLC was shown to be partially dependent on type 1 VEGF receptor (VEGFR1).128 These results were confirmed and extended by Lyden and colleagues who found that LLC cells secrete factors that stimulate the migration of bone marrow-derived VEGFR1-positive hematopoietic cells into the lung.129 The nature of these factors and their mode of action remained unknown until recently.

Using a biochemical approach, we have identified one of the most critical factors secreted by LLC cells as versican, an extracellular matrix (ECM) prometastatic protein that can induce the activation of macrophages and stimulate the secretion of TNF-α and other cytokines.29 We found that conditioned medium collected from LLC cells activated TLR2 on macrophages to induce NF-κB and MAP kinase (MAPK) signaling and thereby stimulate the expression of proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and TNF-α. Importantly, subcutaneous LLC tumors led to TLR2 activation in vivo, which was important for induction of various inflammatory cytokines and chemokines in the lung, including TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1, CCL3/MIP1α, CCL4/MIP1β, CXCL1/MIP2, and CXCL2/KC. Both TLR2 on host bone marrow-derived cells and TNF-α have turned out to be critical for optimal metastatic growth of either tail-vein injected or subcutaneously implanted LLC.29

We used column chromatography and mass spectrometry to identify that the LLC-secreted factor responsible for TLR2 activation and stimulation of metastatic growth is versican,29 an aggregating chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan that was previously found to accumulate both in the tumor stroma and in cancer cells, including lung cancer.130 Using in vivo experiments in TLR2 knock-out mice, we found that versican signals via TLR2 and its coreceptors CD14 and TLR6.29 Versican expression, which is very high in several cancers, including lung cancer,130–132 is stimulated by signaling pathways that are known to be activated in cancer cells.133 Furthermore, versican or fragments thereof can enhance tumor cell migration, growth, and angiogenesis, processes that are of direct relevance to metastasis.134 Versican can bind HA, and both versican and HA are highly expressed in non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC), especially in advanced disease with high recurrence rates, whereas versican expression in normal lung is low.130 In addition to HA, versican can also interact with several adhesion molecules expressed by inflammatory cells and has proinflammatory activity.30 A related ECM proteoglycan, biglycan, was reported to activate both TLR2 and TLR4 on macrophages;135 but our results indicate that the proinflammatory activities of versican rely on TLR2 and TLR6, but not on TLR4, activation. Silencing of versican expression in LLC cells eliminates their metastatic behavior.29 In summary, our results suggest that LLC cells secret versican to activate hematopoietic-derived cells and recruit them to generate an inflammatory microenvironment and to produce TNF-α that stimulates their metastatic behavior. Although the role of versican in the metastatic progression of human NSCLC remains to be confirmed, we have observed that other metastatic cells can also lead to TLR2-dependent macrophage activation, but through other secreted factors. The molecular nature of these factors remains unknown, but the principals that guide their proinflammatory and prometastatic activity are likely to be similar to those established for versican.

Similarities between metastasis wound healing and vascular remodeling

Other than the studies described earlier, it has been noted that tumorigenic and metastatic progression shares many features with the process of wound healing.136,137 For instance, solid tumors must induce new blood vessels if they are to grow beyond a certain minimal size. As established for the neoangiogenic process that accompanies wound healing, tumors secrete vascular permeability factors, for example VEGF, that render the local microvasculature permeable to fibrinogen and other plasma proteins.136 Extravasated fibrinogen is rapidly clotted and invaded by macrophages, fibroblasts, and endothelial cells, and undergoes “organization” and eventually is replaced by vascularized granulation tissue, which finally becomes mature connective tissue.136 The same sequence of events (angiogenesis) found in tumors also occurs during wound healing and in a range of chronic inflammatory diseases. Yet, the molecular alterations that allow tumors to behave like wounds that do not heal137 (invading tumor cells continually render new vessels hyperpermeable to plasma, which does not occur in the normal wound healing process) are just being elucidated.

TGF-β, a key cytokine during embryonic development and tissue homeostasis,138 exerts potent inhibitory effects on epithelial cell proliferation and also can deter tumor growth. 138–140 TGF-β can be produced by myeloid cells, mesenchymal cells, and cancer cells subjected to hypoxic and inflammatory conditions during tumor progression, and is one of the major cytokines in the tumor microenvironment.141 Interestingly, TGF-β in breast tumors was found to prime cancer cells for metastasis to the lungs.142 Central to this process is TGF-β–dependent induction of angiopoietin-like 4 (ANGPTL4) in cancer cells that are about to enter the circulation, which enhances their subsequent retention in the lungs.142 Tumor cell-derived ANGPTL4 disrupts vascular endothelial cell–cell junctions, increases the permeability of lung capillaries, and facilitates the trans-endothelial passage of tumor cells.142 Although this work describes the molecular basis for the vasculature disruptive activity of TGF-β, it is likely that the prometastatic activity of this cytokine depends on several other processes as well.

Inflammation and transcriptional control of metastatic genes

Inflammatory cytokines, chemokines, and the proinflammatory microenvironment also have a role in shaping the gene expression profile that is required for metastatic behavior of cancer cells, including genes that encode mediators of vascular remodeling, such as integrins, VCAM, and MMPs.66,143

A key transcription factor in metastasis is the helix-loop-helix protein Twist, which regulates cell movement and tissue reorganization during early embryogenesis.144 Suppression of Twist expression in metastatic 4T1 mammary carcinoma cells specifically inhibits their ability to metastasize from the mammary gland to the lung.144 Importantly, the ability of these cells to form primary mammary tumors was not affected. Loss of Twist expression hindered the entry of metastatic cells into the circulation.144 Like several other controllers of tumorigenesis, Twist is likely to exert similar biological activities during metastatic progression as it does during normal development. In Drosophila, the twist gene is required for mesoderm induction;145,146 in vertebrates Twist is predominantly expressed in neural crest cells; and ablation of Twist in mice causes failure in cranial neural tube closure, all of these data indicate a role for Twist in migration and differentiation of neural crest and head mesenchym.147,148 Both mesoderm formation and neural crest development depend on a key cellular event termed the epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT), which involves the conversion of a sheet of tightly attached epithelial cells into highly mobile mesenchymal or neural crest cells.149 Indeed, ectopic expression of Twist resulted in loss of E-cadherin-mediated cell–cell adhesion, activation of mesenchymal markers, and gain of motility by malignant cells.144 These results suggest that Twist can contribute to invasion and metastasis by promoting the EMT developmental program. Interestingly, under certain circumstances, Twist expression can be induced in response to NF-κB activation150 and, therefore, can be upregulated in response to inflammation. This provides a mechanism through which tumor-associated inflammation may stimulate metastatic progression through induction of Twist-dependent EMT.

We have identified another mechanism by which tumor-associated inflammation can affect expression of key metastasis control genes. By studying the TRAMP model of metastatic prostate cancer we found that appearance of distant site metastasis as well as the metastatic behavior of isolated carcinoma cells are dependent on the activation and nuclear accumulation of IKKα.92 By examining expression of 40 known genes that either enhance or suppress metastasis,151 we found that IKKα exerted its prometastatic effect by repressing transcription of the gene maspin.92 Maspin is a member of the serpin family with well-established antimetastatic activity in breast and prostate cancers.152,153 Repression of maspin transcription required nuclear translocation of catalytically active IKKα, and the two processes only occur in advanced prostate tumors that contain inflammatory infiltrates and cells that express RANKL and LTα:β.92 Early tumors devoid of inflammatory infiltrates do not show activated IKKα and, in contrast to late tumors, express high amounts of maspin and therefore lack metastatic activity. In vitro, RANKL can lead to repression of maspin-expression in an IKKα-dependent manner. Once in the nucleus, IKKα interacts with the maspin control region, but the mechanism through which it induces its repressive activity is not clear.

Effect of TLR agonists and cytokines on metastatic growth

Several clinical trials are on-going using TLR ligands in different types of cancer. In these trials, TLR agonists are expected to activate the host immune system including CD8+ effector T cells and NK cells, which should kill tumor cells and subsequently reduce tumor progression and metastasis. One potentially successful example is imiquimod, a TLR7 agonist.31,154 This drug is extensively used to treat actinic keratosis and basal cell carcinoma, and it is being studied as an adjuvant therapy for melanoma.31 A study of imiquimod 5% cream in 90 patients with basal cell carcinoma reported a 96% clearance rate and only two recurrences during a mean follow-up period of 36 months.155 Cutaneous side effects were minimal and no systemic side effects were reported. Imiquimod induces IFN-α, IFN-γ, and IL-12, which activate APC function and TAA-specific immunity.156

On the other hand, several publications have demonstrated that strong proinflammatory stimuli can stimulate tumor growth and have suggested that bacterial contamination during surgery or postoperative inflammation triggered by tissue damage can increase metastatic tumor growth in mice71,157,158 and human patients.159 As described earlier, very high doses of TNF-α administered in close proximity to solid tumors can kill cancer cells by destroying the tumor neovasculature.104 However, endogenous TNF-α at moderate amounts produced by activated inflammatory cells promotes tumor development and growth.160 We found that administration of a sublethal dose of LPS, a TLR4 agonist, can stimulate the metastatic growth of colon carcinoma cells in the lung by inducing TNF-α expression.71 However, LPS administration also leads to induction of the death cytokine TRAIL,71 a type II transmembrane protein of the TNF family also known as Apo2 ligand, which in contrast to TNF-α is a weak inducer of inflammation.161 Administration of recombinant TRAIL suppresses the growth of tumor xenografts with no apparent systemic toxicity.162 Endogenously expressed TRAIL on the surface of NK cells can suppress the growth of liver and lung metastases.71,163 Inhibition of NF-κB activation in metastatic colon cancer cells prevents and strongly enhances susceptibility to TRAIL-induced killing.71 Thus, inhibition of NF-κB in malignant cells may be used to convert the prometastatic activity of LPS and similar proinflammatory stimuli and TLR agonists to a potent tumoricidal effect. Only future clinical studies will tell whether TLR agonists will be found to have a broad antitumorigenic activity or whether TLR stimulation should be avoided at all costs due to its tumor-promoting and prometastatic activity.

In addition to TNF-α and TRAIL, other cytokines may also affect tumor progression or regression. A considerable effort has been invested in the use of cytokines and anticytokine drugs in cancer therapy.164 One of the most effective agents identified so far is IFN-α, which evokes antitumor effects in several hematological malignancies and solid tumors.165 The infusion of high doses of IL-2 was also found to induce regression of renal cell carcinoma and melanoma in a minority of patients.166,167 Recently, numerous preclinical studies have established the ability of tumors that were engineered to produce cytokines to serve as cellular vaccines that augment systemic immunity against wild-type tumors (cytokine-based vaccines).168 On the flip side of the coin, both anti-TNF-α and anti-IL-6 drugs are currently being evaluated for their antitumor activities and encouraging results have been reported.31

Can we use anti-inflammatory drugs to battle metastatic cancer?

As discussed earlier, there is ample evidence from experimental cancer models in rodents and investigations of human cancer that continuous/chronic inflammation stimulates tumorigenesis and metastatic progression. If so, therapies that are directed at reducing inflammation, inhibiting the function of inflammatory cytokines, or preventing the recruitment of inflammatory cells onto the tumor microenvironment could reduce cancer risk, slow tumor progression, and may even decrease the burden of metastasis. Indeed, the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and aspirin was found to reduce colon cancer risk by 40–50%, and may also have a significant preventative effect in lung, esophageal, and stomach cancers.169,170 The ability of NSAIDs to inhibit COX-1 and COX-2 underlies their mechanisms of chemo-prevention. Other NSAIDs, for example, flubiprofen, were found to have strong antimetastatic effects that were attributed to their inhibition of platelet aggregation.130 However, NSAIDs may act through additional mechanisms, as some NSAIDs lacking COX-inhibitory function are also effective in inhibiting colon carcinogenesis.171

Some of the current NSAIDs—especially those that are COX-2 selective—exert side effects, such as life-threatening stomach ulcers, heart attacks, and strokes, in a considerable number of patients,172 and this has limited their utility. The continuing study of the molecular mechanisms that lead to inflammatory cell activation within tumors and consequently stimulate tumor growth, angiogenesis, and progression should help in the identification of new therapeutic targets and aid in the design of new drugs free of such side effects. In addition, this understanding may also aid the development of vaccines and other strategies that enhance antitumor immunity.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Balkwill F, Coussens LM. Cancer: an inflammatory link. Nature. 2004;431:405–406. doi: 10.1038/431405a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Balkwill F, Mantovani A. Inflammation and cancer: back to Virchow? Lancet. 2001;357:539–545. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04046-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coussens LM, Werb Z. Inflammation and cancer. Nature. 2002;420:860–867. doi: 10.1038/nature01322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Karin M. Inflammation and cancer: the long reach of Ras. Nat. Med. 2005;11:20–21. doi: 10.1038/nm0105-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Karin M. Nuclear factor-kappaB in cancer development and progression. Nature. 2006;441:431–436. doi: 10.1038/nature04870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mantovani A, Allavena P, Sica A, Balkwill F. Cancer-related inflammation. Nature. 2008;454:436–444. doi: 10.1038/nature07205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Park JS, Svetkauskaite D, He Q, et al. Involvement of toll-like receptors 2 and 4 in cellular activation by high mobility group box 1 protein. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:7370–7377. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306793200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sakurai T, He G, Matsuzawa A, et al. Hepatocyte necrosis induced by oxidative stress and IL-1 alpha release mediate carcinogen-induced compensatory proliferation and liver tumorigenesis. Cancer Cell. 2008;14:156–165. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kawai T, Akira S. The role of pattern-recognition receptors in innate immunity: update on Toll-like receptors. Nat. Immunol. 11:373–384. doi: 10.1038/ni.1863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O’Neill LA. When signaling pathways collide: positive and negative regulation of toll-like receptor signal transduction. Immunity. 2008;29:12–20. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Saikumar P, Dong Z, Mikhailov V, et al. Apoptosis: definition, mechanisms, and relevance to disease. Am. J. Med. 1999;107:489–506. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(99)00259-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vanlangenakker N, Vanden Berghe T, Krysko DV, et al. Molecular mechanisms and pathophysiology of necrotic cell death. Curr. Mol. Med. 2008;8:207–220. doi: 10.2174/156652408784221306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lotze MT, Zeh HJ, Rubartelli A, et al. The grateful dead: damage-associated molecular pattern molecules and reduction/oxidation regulate immunity. Immunol. Rev. 2007;220:60–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2007.00579.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ellerman JE, Brown CK, de Vera M, et al. Masquerader: high mobility group box-1 and cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2007;13:2836–2848. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Klein JR, Hoon DS, Nangauyan J, et al. S-100 protein stimulates cellular proliferation. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 1989;29:133–138. doi: 10.1007/BF00199288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tsan MF, Gao B. Cytokine function of heat shock proteins. Am. J. Physiol. Cell. Physiol. 2004;286:C739–C744. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00364.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wallin RP, Lundqvist A, More SH, et al. Heat-shock proteins as activators of the innate immune system. Trends Immunol. 2002;23:130–135. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(01)02168-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhao Y, Yokota K, Ayada K, et al. Helicobacter pylori heat-shock protein 60 induces interleukin-8 via a Toll-like receptor (TLR)2 and mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase pathway in human monocytes. J. Med. Microbiol. 2007;56:154–164. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.46882-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kalogeraki A, Garbagnati F, Darivianaki K, et al. HSP-70, C-myc and HLA-DR expression in patients with cutaneous malignant melanoma metastatic in lymph nodes. Anticancer Res. 2006;26:3551–3554. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tetu B, Lacasse B, Bouchard HL, et al. Prognostic influence of HSP-27 expression in malignant fibrous histiocytoma: a clinicopathological and immunohistochemical study. Cancer Res. 1992;52:2325–2328. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smiley ST, King JA, Hancock WW. Fibrinogen stimulates macrophage chemokine secretion through toll-like receptor 4. J. Immunol. 2001;167:2887–2894. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.5.2887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guillot L, Balloy V, McCormack FX, et al. Cutting edge: the immunostimulatory activity of the lung surfactant protein-A involves Toll-like receptor 4. J. Immunol. 2002;168:5989–5992. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.12.5989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Okamura Y, Watari M, Jerud ES, et al. The extra domain A of fibronectin activates Toll-like receptor 4. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:10229–10233. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100099200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Saito S, Yamaji N, Yasunaga K, et al. The fibronectin extra domain A activates matrix metalloproteinase gene expression by an interleukin-1-dependent mechanism. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:30756–30763. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.43.30756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Johnson GB, Brunn GJ, Kodaira Y, Platt JL. Receptor-mediated monitoring of tissue well-being via detection of soluble heparan sulfate by Toll-like receptor 4. J. Immunol. 2002;168:5233–5239. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.10.5233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Termeer C, Benedix F, Sleeman J, et al. Oligosaccharides of Hyaluronan activate dendritic cells via toll-like receptor 4. J. Exp. Med. 2002;195:99–111. doi: 10.1084/jem.20001858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Biragyn A, Ruffini PA, Leifer CA, et al. Toll-like receptor 4-dependent activation of dendritic cells by beta-defensin 2. Science. 2002;298:1025–1029. doi: 10.1126/science.1075565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wakasugi K, Schimmel P. Two distinct cytokines released from a human aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase. Science. 1999;284:147–151. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5411.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim S, Takahashi H, Lin WW, et al. Carcinoma-produced factors activate myeloid cells through TLR2 to stimulate metastasis. Nature. 2009;457:102–106. doi: 10.1038/nature07623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wight TN. Versican: a versatile extracellular matrix proteoglycan in cell biology. Curr. Opin. Cell. Biol. 2002;14:617–623. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(02)00375-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Adams S, O’Neill DW, Nonaka D, et al. Immunization of malignant melanoma patients with full-length NY-ESO-1 protein using TLR7 agonist imiquimod as vaccine adjuvant. J. Immunol. 2008;181:776–784. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.1.776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gal S, Fidler C, Lo YM, et al. Quantitation of circulating DNA in the serum of breast cancer patients by real-time PCR. Br. J. Cancer. 2004;90:1211–1215. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang BG, Huang HY, Chen YC, et al. Increased plasma DNA integrity in cancer patients. Cancer Res. 2003;63:3966–3968. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Campana L, Bosurgi L, Rovere-Querini P. HMGB1: a two-headed signal regulating tumor progression and immunity. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2008;20:518–523. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2008.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kuper H, Adami HO, Trichopoulos D. Infections as a major preventable cause of human cancer. J. Intern. Med. 2000;248:171–183. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.2000.00742.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Niwa T, Tsukamoto T, Toyoda T, et al. Inflammatory processes triggered by Helicobacter pylori infection cause aberrant DNA methylation in gastric epithelial cells. Cancer Res. 2010;70:1430–1440. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-2755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kumagai Y, Takeuchi O, Akira S. Pathogen recognition by innate receptors. J. Infect. Chemother. 2008;14:86–92. doi: 10.1007/s10156-008-0596-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Medzhitov R, Preston-Hurlburt P, Janeway CA., Jr A human homologue of the Drosophila Toll protein signals activation of adaptive immunity. Nature. 1997;388:394–397. doi: 10.1038/41131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Takeda K, Kaisho T, Akira S. Toll-like receptors. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2003;21:335–376. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.141126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Takeda K, Akira S. Toll-like receptors. Curr. Protoc. Immunol. 2007 doi: 10.1002/0471142735.im1412s77. Chapter 14, Unit 14 12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Asea A, Rehli M, Kabingu E, et al. Novel signal transduction pathway utilized by extracellular HSP70: role of toll-like receptor (TLR) 2 and TLR4. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:15028–15034. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200497200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kariko K, Ni H, Capodici J, et al. mRNA is an endogenous ligand for Toll-like receptor 3. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:12542–12550. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310175200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ohashi K, Burkart V, Flohe S, Kolb H. Cutting edge: heat shock protein 60 is a putative endogenous ligand of the toll-like receptor-4 complex. J. Immunol. 2000;164:558–561. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.2.558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Takeuchi O, Sato S, Horiuchi T, et al. Cutting edge: role of Toll-like receptor 1 in mediating immune response to microbial lipoproteins. J. Immunol. 2002;169:10–14. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.1.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Takeuchi O, Hoshino K, Kawai T, et al. Differential roles of TLR2 and TLR4 in recognition of gram-negative and gram-positive bacterial cell wall components. Immunity. 1999;11:443–451. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80119-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Alexopoulou L, Holt AC, Medzhitov R, Flavell RA. Recognition of double-stranded RNA and activation of NF-kappaB by Toll-like receptor 3. Nature. 2001;413:732–738. doi: 10.1038/35099560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hayashi F, Smith KD, Ozinsky A, et al. The innate immune response to bacterial flagellin is mediated by Toll-like receptor 5. Nature. 2001;410:1099–1103. doi: 10.1038/35074106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Takeuchi O, Kawai T, Muhlradt PF, et al. Discrimination of bacterial lipoproteins by Toll-like receptor 6. Int. Immunol. 2001;13:933–940. doi: 10.1093/intimm/13.7.933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lund JM, Alexopoulou L, Sato A, et al. Recognition of single-stranded RNA viruses by Toll-like receptor 7. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:5598–5603. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400937101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hemmi H, Takeuchi O, Kawai T, et al. A Toll-like receptor recognizes bacterial DNA. Nature. 2000;408:740–745. doi: 10.1038/35047123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Akira S, Takeda K. Toll-like receptor signalling. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2004;4:499–511. doi: 10.1038/nri1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kopp E, Medzhitov R. Recognition of microbial infection by Toll-like receptors. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2003;15:396–401. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(03)00080-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhang JJ, Wu HS, Wang L, et al. Expression and significance of TLR4 and HIF-1alpha in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. World J. Gastroenterol. 2010;16:2881–2888. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i23.2881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang EL, Qian ZR, Nakasono M, et al. High expression of Toll-like receptor 4/myeloid differentiation factor 88 signals correlates with poor prognosis in colorectal cancer. Br. J. Cancer. 2010;102:908–915. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. The hallmarks of cancer. Cell. 2000;100:57–70. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81683-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hussain SP, Hofseth LJ, Harris CC. Radical causes of cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2003;3:276–285. doi: 10.1038/nrc1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jaiswal M, LaRusso NF, Burgart LJ, Gores GJ. Inflammatory cytokines induce DNA damage and inhibit DNA repair in cholangiocarcinoma cells by a nitric oxide-dependent mechanism. Cancer Res. 2000;60:184–190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jaiswal M, LaRusso NF, Gores GJ. Nitric oxide in gastrointestinal epithelial cell carcinogenesis: linking inflammation to oncogenesis. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver. Physiol. 2001;281:G626–G634. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.2001.281.3.G626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Greten FR, Karin M. The IKK/NF-kappaB activation pathway-a target for prevention and treatment of cancer. Cancer Lett. 2004;206:193–199. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2003.08.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Meira LB, Bugni JM, Green SL, et al. DNA damage induced by chronic inflammation contributes to colon carcinogenesis in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 2008;118:2516–2525. doi: 10.1172/JCI35073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Boudreau JE, Bridle BW, Stephenson KB, et al. Recombinant vesicular stomatitis virus transduction of dendritic cells enhances their ability to prime innate and adaptive antitumor immunity. Mol. Ther. 2009;17:1465–1472. doi: 10.1038/mt.2009.95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lin WW, Karin M. A cytokine-mediated link between innate immunity, inflammation, and cancer. J. Clin. Invest. 2007;117:1175–1183. doi: 10.1172/JCI31537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Grivennikov SI, Greten FR, Karin M. Immunity, inflammation, and cancer. Cell. 140:883–899. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sparmann A, Bar-Sagi D. Ras-induced interleukin-8 expression plays a critical role in tumor growth and angiogenesis. Cancer Cell. 2004;6:447–458. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lin EY, Nguyen AV, Russell RG, Pollard JW. Colony-stimulating factor 1 promotes progression of mammary tumors to malignancy. J. Exp. Med. 2001;193:727–740. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.6.727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Balkwill F, Charles KA, Mantovani A. Smoldering and polarized inflammation in the initiation and promotion of malignant disease. Cancer Cell. 2005;7:211–217. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bui JD, Schreiber RD. Cancer immunosurveillance, immunoediting and inflammation: independent or interdependent processes? Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2007;19:203–208. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2007.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Karin M, Cao Y, Greten FR, Li ZW. NF-kappaB in cancer: from innocent bystander to major culprit. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2002;2:301–310. doi: 10.1038/nrc780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Old LJ. Tumor necrosis factor. Sci. Am. 1988;258:59–60. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican0588-59. 69–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Arnott CH, Scott KA, Moore RJ, et al. Tumour necrosis factor-alpha mediates tumour promotion via a PKC alpha- and AP-1-dependent pathway. Oncogene. 2002;21:4728–4738. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Luo JL, Maeda S, Hsu LC, et al. Inhibition of NF-kappaB in cancer cells converts inflammation-induced tumor growth mediated by TNFalpha to TRAIL-mediated tumor regression. Cancer Cell. 2004;6:297–305. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Grivennikov S, Karin M. Autocrine IL-6 signaling: a key event in tumorigenesis? Cancer Cell. 2008;13:7–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hofseth LJ. Nitric oxide as a target of complementary and alternative medicines to prevent and treat inflammation and cancer. Cancer Lett. 2008;268:10–30. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.03.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sawa T, Ohshima H. Nitrative DNA damage in inflammation and its possible role in carcinogenesis. Nitric Oxide. 2006;14:91–100. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2005.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Gordon S. Alternative activation of macrophages. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2003;3:23–35. doi: 10.1038/nri978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Mantovani A, Sica A, Locati M. Macrophage polarization comes of age. Immunity. 2005;23:344–346. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Mantovani A, Sica A, Sozzani S, et al. The chemokine system in diverse forms of macrophage activation and polarization. Trends Immunol. 2004;25:677–686. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2004.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kuroda E, Ho V, Ruschmann J, et al. SHIP represses the generation of IL-3-induced M2 macrophages by inhibiting IL-4 production from basophils. J. Immunol. 2009;183:3652–3660. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Verreck FA, de Boer T, Langenberg DM, et al. Human IL-23-producing type 1 macrophages promote but IL-10-producing type 2 macrophages subvert immunity to (myco)bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:4560–4565. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400983101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Mantovani A, Bottazzi B, Colotta F, et al. The origin and function of tumor-associated macrophages. Immunol. Today. 1992;13:265–270. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(92)90008-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Mantovani A, Sozzani S, Locati M, et al. Macrophage polarization: tumor-associated macrophages as a paradigm for polarized M2 mononuclear phagocytes. Trends Immunol. 2002;23:549–555. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(02)02302-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Pollard JW. Tumour-educated macrophages promote tumour progression and metastasis. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2004;4:71–78. doi: 10.1038/nrc1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Li H, Han Y, Guo Q, et al. Cancer-expanded myeloid-derived suppressor cells induce anergy of NK cells through membrane-bound TGF-beta 1. J. Immunol. 2009;182:240–249. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.182.1.240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Rodriguez PC, Ochoa AC. Arginine regulation by myeloid derived suppressor cells and tolerance in cancer: mechanisms and therapeutic perspectives. Immunol. Rev. 2008;222:180–191. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00608.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Zou W, Machelon V, Coulomb-L’Hermin A, et al. Stromal-derived factor-1 in human tumors recruits and alters the function of plasmacytoid precursor dendritic cells. Nat. Med. 2001;7:1339–1346. doi: 10.1038/nm1201-1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kundu SD, Lee C, Billips BK, et al. The toll-like receptor pathway: a novel mechanism of infection-induced carcinogenesis of prostate epithelial cells. Prostate. 2008;68:223–229. doi: 10.1002/pros.20710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Li H, Fan X, Houghton J. Tumor microenvironment: the role of the tumor stroma in cancer. J. Cell. Biochem. 2007;101:805–815. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Haviv I, Polyak K, Qiu W, et al. Origin of carcinoma associated fibroblasts. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:589–595. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.4.7669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Bhowmick NA, Chytil A, Plieth D, et al. TGF-beta signaling in fibroblasts modulates the oncogenic potential of adjacent epithelia. Science. 2004;303:848–851. doi: 10.1126/science.1090922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Tetu B, Trudel D, Wang CS. [Proteases by reactive stromal cells in cancer: an attractive therapeutic target] Bull. Cancer. 2006;93:944–948. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Mueller L, Goumas FA, Affeldt M, et al. Stromal fibroblasts in colorectal liver metastases originate from resident fibroblasts and generate an inflammatory microenvironment. Am. J. Pathol. 2007;171:1608–1618. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.060661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Luo JL, Tan W, Ricono JM, et al. Nuclear cytokine-activated IKKalpha controls prostate cancer metastasis by repressing Maspin. Nature. 2007;446:690–694. doi: 10.1038/nature05656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Sasaki A, Ishikawa K, Haraguchi N, et al. Receptor activator of nuclear factor-kappaB ligand (RANKL) expression in hepatocellular carcinoma with bone metastasis. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2007;14:1191–1199. doi: 10.1245/s10434-006-9277-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Yu H, Kortylewski M, Pardoll D. Crosstalk between cancer and immune cells: role of STAT3 in the tumour microenvironment. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2007;7:41–51. doi: 10.1038/nri1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Scortegagna M, Cataisson C, Martin RJ, et al. HIF-1alpha regulates epithelial inflammation by cell autonomous NFkappaB activation and paracrine stromal remodeling. Blood. 2008;111:3343–3354. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-10-115758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Rius J, Guma M, Schachtrup C, et al. NF-kappaB links innate immunity to the hypoxic response through transcriptional regulation of HIF-1alpha. Nature. 2008;453:807–811. doi: 10.1038/nature06905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Zinkernagel AS, Johnson RS, Nizet V. Hypoxia inducible factor (HIF) function in innate immunity and infection. J. Mol. Med. 2007;85:1339–1346. doi: 10.1007/s00109-007-0282-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Rossi D, Zlotnik A. The biology of chemokines and their receptors. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2000;18:217–242. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.18.1.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Mantovani A, Muzio M, Garlanda C, et al. Macrophage control of inflammation: negative pathways of regulation of inflammatory cytokines. Novartis Found Symp. 2001;234:120–131. doi: 10.1002/0470868678.ch8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Norgauer J, Metzner B, Schraufstatter I. Expression and growth-promoting function of the IL-8 receptor beta in human melanoma cells. J. Immunol. 1996;156:1132–1337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Ottaiano A, Franco R, Aiello Talamanca A, et al. Overexpression of both CXC chemokine receptor 4 and vascular endothelial growth factor proteins predicts early distant relapse in stage II-III colorectal cancer patients. Clin. Cancer Res. 2006;12:2795–2803. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Richmond A, Thomas HG. Purification of melanoma growth stimulatory activity. J. Cell. Physiol. 1986;129:375–384. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041290316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Balkwill F. Tumor necrosis factor or tumor promoting factor? Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2002;13:135–141. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6101(01)00020-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Havell EA, Fiers W, North RJ. The antitumor function of tumor necrosis factor (TNF), I. Therapeutic action of TNF against an established murine sarcoma is indirect, immunologically dependent, and limited by severe toxicity. J. Exp. Med. 1988;167:1067–1085. doi: 10.1084/jem.167.3.1067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Arnott CH, Scott KA, Moore RJ, et al. Expression of both TNF-alpha receptor subtypes is essential for optimal skin tumour development. Oncogene. 2004;23:1902–1910. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Knight B, Yeoh GC, Husk KL, et al. Impaired preneoplastic changes and liver tumor formation in tumor necrosis factor receptor type 1 knockout mice. J. Exp. Med. 2000;192:1809–1818. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.12.1809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Pikarsky E, Porat RM, Stein I, et al. NF-kappaB functions as a tumour promoter in inflammation-associated cancer. Nature. 2004;431:461–466. doi: 10.1038/nature02924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Greten FR, Eckmann L, Greten TF, et al. IKKbeta links inflammation and tumorigenesis in a mouse model of colitis-associated cancer. Cell. 2004;118:285–296. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Galban S, Fan J, Martindale JL, et al. von Hippel-Lindau protein-mediated repression of tumor necrosis factor alpha translation revealed through use of cDNA arrays. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2003;23:2316–2328. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.7.2316-2328.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Tracey KJ, Lowry SF, Beutler B, et al. Cachectin/tumor necrosis factor mediates changes of skeletal muscle plasma membrane potential. J. Exp. Med. 1986;164:1368–1373. doi: 10.1084/jem.164.4.1368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Onizawa M, Nagaishi T, Kanai T, et al. Signaling pathway via TNF-alpha/NF-kappaB in intestinal epithelial cells may be directly involved in colitis-associated car-cinogenesis. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver. Physiol. 2009;296:G850–G859. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00071.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Anasagasti MJ, Olaso E, Calvo F, et al. Interleukin 1-dependent and -independent mouse melanoma metastases. J. Natl. Cancer. Inst. 1997;89:645–651. doi: 10.1093/jnci/89.9.645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Apte RN, Voronov E. Interleukin-1—a major pleiotropic cytokine in tumor-host interactions. Semin. Cancer. Biol. 2002;12:277–290. doi: 10.1016/s1044-579x(02)00014-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Song X, Voronov E, Dvorkin T, et al. Differential effects of IL-1 alpha and IL-1 beta on tumorigenicity patterns and invasiveness. J. Immunol. 2003;171:6448–6456. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.12.6448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Dinarello CA, Schindler R. Dissociation of transcription from translation of human IL-1-beta: the induction of steady state mRNA by adherence or recombinant C5a in the absence of translation. Prog. Clin. Biol. Res. 1990;349:195–204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Greten FR, Arkan MC, Bollrath J, et al. NF-kappaB is a negative regulator of IL-1beta secretion as revealed by genetic and pharmacological inhibition of IKKbeta. Cell. 2007;130:918–931. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Chen CJ, Kono H, Golenbock D, et al. Identification of a key pathway required for the sterile inflammatory response triggered by dying cells. Nat. Med. 2007;13:851–856. doi: 10.1038/nm1603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Harris TB, Ferrucci L, Tracy RP, et al. Associations of elevated interleukin-6 and C-reactive protein levels with mortality in the elderly. Am. J. Med. 1999;106:506–512. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(99)00066-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Preacher KJ, MacCallum RC, et al. Chronic stress and age-related increases in the proinflammatory cytokine IL-6. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:9090–9095. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1531903100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Gallucci M, Amici GP, Ongaro F, et al. Associations of the plasma interleukin 6 (IL-6) levels with disability and mortality in the elderly in the Treviso Longeva (Trelong) study. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2007;44(Suppl 1):193–198. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2007.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Ershler WB, Keller ET. Age-associated increased interleukin-6 gene expression, late-life diseases, and frailty. Annu. Rev. Med. 2000;51:245–270. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.51.1.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Trikha M, Corringham R, Klein B, Rossi JF. Targeted anti-interleukin-6 monoclonal antibody therapy for cancer: a review of the rationale and clinical evidence. Clin. Cancer. Res. 2003;9:4653–4665. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Honemann D, Chatterjee M, Savino R, et al. The IL-6 receptor antagonist SANT-7 overcomes bone marrow stromal cell-mediated drug resistance of multiple myeloma cells. Int. J. Cancer. 2001;93:674–680. doi: 10.1002/ijc.1388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Naugler WE, Sakurai T, Kim S, et al. Gender disparity in liver cancer due to sex differences in MyD88-dependent IL-6 production. Science. 2007;317:121–124. doi: 10.1126/science.1140485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Choy H, Milas L. Enhancing radiotherapy with cyclooxygenase-2 enzyme inhibitors: a rational advance? J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2003;95:1440–1452. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djg058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Gasparini G, Longo R, Sarmiento R, Morabito A. Inhibitors of cyclo-oxygenase 2: a new class of anticancer agents? Lancet Oncol. 2003;4:605–615. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(03)01220-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Baek SJ, Eling TE. Changes in gene expression contribute to cancer prevention by COX inhibitors. Prog. Lipid Res. 2006;45:1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2005.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Hiratsuka S, Nakamura K, Iwai S, et al. MMP9 induction by vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-1 is involved in lung-specific metastasis. Cancer Cell. 2002;2:289–300. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(02)00153-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Kaplan RN, Riba RD, Zacharoulis S, et al. VEGFR1-positive haematopoietic bone marrow progenitors initiate the pre-metastatic niche. Nature. 2005;438:820–827. doi: 10.1038/nature04186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Pirinen R, Leinonen T, Bohm J, et al. Versican in nonsmall cell lung cancer: relation to hyaluronan, clinicopathologic factors, and prognosis. Hum. Pathol. 2005;36:44–50. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2004.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Ricciardelli C, Russell DL, Ween MP, et al. Formation of hyaluronan- and versican-rich pericellular matrix by prostate cancer cells promotes cell motility. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:10814–10825. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M606991200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Yee AJ, Akens M, Yang BL, et al. The effect of versican G3 domain on local breast cancer invasiveness and bony metastasis. Breast Cancer Res. 2007;9:R47. doi: 10.1186/bcr1751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Rahmani M, Wong BW, Ang L, et al. Versican: signaling to transcriptional control pathways. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2006;84:77–92. doi: 10.1139/y05-154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Zheng PS, Wen J, Ang LC, et al. Versican/PG-M G3 domain promotes tumor growth and angiogenesis. FASEB J. 2004;18:754–756. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-0545fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Schaefer L, Babelova A, Kiss E, et al. The matrix component biglycan is proinflammatory and signals through Toll-like receptors 4 and 2 in macrophages. J. Clin. Invest. 2005;115:2223–2233. doi: 10.1172/JCI23755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Brown LF, Dvorak AM, Dvorak HF. Leaky vessels, fibrin deposition, and fibrosis: a sequence of events common to solid tumors and to many other types of disease. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 1989;140:1104–1107. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/140.4.1104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Dvorak HF. Tumors: wounds that do not heal. Similarities between tumor stroma generation and wound healing. N. Engl. J. Med. 1986;315:1650–1659. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198612253152606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Massague J, Blain SW, Lo RS. TGFbeta signaling in growth control, cancer, and heritable disorders. Cell. 2000;103:295–309. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00121-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Bierie B, Moses HL. Tumour microenvironment: TGFbeta: the molecular Jekyll and Hyde of cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2006;6:506–520. doi: 10.1038/nrc1926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Dumont N, Arteaga CL. Targeting the TGF beta signaling network in human neoplasia. Cancer Cell. 2003;3:531–536. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00135-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Yang L, Pang Y, Moses HL. TGF-beta and immune cells: an important regulatory axis in the tumor microenvironment and progression. Trends Immunol. 2010;31:220–227. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2010.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Padua D, Zhang XH, Wang Q, et al. TGFbeta primes breast tumors for lung metastasis seeding through angiopoietin-like 4. Cell. 2008;133:66–77. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Alberti C. Genetic and microenvironmental implications in prostate cancer progression and metastasis. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2008;12:167–175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Yang J, Mani SA, Donaher JL, et al. Twist, a master regulator of morphogenesis plays an essential role in tumor metastasis. Cell. 2004;117:927–939. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Leptin M, Grunewald B. Cell shape changes during gastrulation in Drosophila. Development. 1990;110:73–84. doi: 10.1242/dev.110.1.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Thisse B, el Messal M, Perrin-Schmitt F. The twist gene: isolation of a Drosophila zygotic gene necessary for the establishment of dorsoventral pattern. Nucleic Acids Res. 1987;15:3439–3453. doi: 10.1093/nar/15.8.3439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Chen ZF, Behringer RR. Twist is required in head mesenchyme for cranial neural tube morphogenesis. Genes. Dev. 1995;9:686–699. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.6.686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Soo K, O’Rourke MP, Khoo PL, et al. Twist function is required for the morphogenesis of the cephalic neural tube and the differentiation of the cranial neural crest cells in the mouse embryo. Dev. Biol. 2002;247:251–270. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2002.0699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Hay ED. An overview of epithelio-mesenchymal transformation. Acta. Anat. (Basel) 1995;154:8–20. doi: 10.1159/000147748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Pham CG, Bubici C, Zazzeroni F, et al. Upregulation of Twist-1 by NF-kappaB blocks cytotoxicity induced by chemotherapeutic drugs. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2007;27:3920–3935. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01219-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Steeg PS. Metastasis suppressors alter the signal transduction of cancer cells. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2003;3:55–63. doi: 10.1038/nrc967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Lockett J, Yin S, Li X, et al. Tumor suppressive maspin and epithelial homeostasis. J. Cell. Biochem. 2006;97:651–660. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]