Abstract

Background:

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs used for postoperative analgesia have considerable adverse effects, with paracetamol having a different mechanism of action, superior side effect profile and availability in intravenous (IV) form, this study was conducted to compare intra-peritoneal bupivacaine with IV paracetamol for postoperative analgesia following laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

Aim:

The aim was to compare the efficacy of intra-peritoneal administration of bupivacaine 0.5% and IV acetaminophen for postoperative analgesia in patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

Settings and Design:

Randomized, prospective trial.

Materials and Methods:

A total of 60 patients of American Society of Anesthesiologists physical Status I and II scheduled for laparoscopic cholecystectomy were enrolled for this study. Group I received 2 mg/kg of 0.5% bupivacaine as local intra-peritoneal application and Group II patients received IV 1 g paracetamol 6th hourly. Postoperatively, the patients were assessed for pain utilizing Visual Analog Scale (VAS), Visual Rating Prince Henry Scale (VRS), shoulder pain. The total number of patients requiring rescue analgesia and any side-effects were noted.

Statistical Analysis:

Data analysis was performed using Students unpaired t-test. SPSS version 11.5 was used.

Results:

The VAS was significantly higher in Group I compared with Group II at 8th, 12th and 24th postoperative hour. At 1st and 4th postoperative hours, VAS was comparable between the two groups. Although the VRS was higher in Group I compared with Group II at 12th and 24th postoperative hour; the difference was statistically significant only at 24th postoperative hour. None of the patients in either of the groups had shoulder pain up to 8 h postoperative. The total number of patients requiring analgesics was higher in Group II than Group I at 1st postoperative hour.

Conclusion:

Although local anesthetic infiltration and intra-peritoneal administration of 0.5% bupivacaine decreases the severity of incisional, visceral and shoulder pain in the early postoperative period, IV paracetamol provides sustained pain relief for 24 postoperative hours after elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

Keywords: Bupivacaine, infiltration, intra-peritoneal, paracetamol, postoperative pain

INTRODUCTION

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy introduced by Phillipe Mouret in 1987 is now the gold standard for the treatment of gallstones disease.[1] Pain after laparoscopic cholecystectomy is usually an acute pain, sharp in character that starts with the surgical trauma and ends with tissue healing.[2,3,4] Although it is less intense than following open cholecystectomy, some patients still experience considerable discomfort during the first 24–72 postoperative hours, which can delay discharge. The origin of pain after laparoscopic cholecystectomy is multifactorial. Pain arising from incision sites being somatic pain, whereas pain from the gallbladder bed being mainly visceral in nature, and shoulder pain is mainly due to the residual CO2 irritating the diaphragm. It is, therefore, likely that combined methods of analgesia can best reduce postoperative pain.[5] Postoperative pain results in tachycardia, hypertension increased cardiac work, nausea, vomiting, and ileus. Thus, pain relief and patient comfort during the early postoperative period becomes increasingly important as the need for analgesic may delay discharge. Adequacy of postoperative pain control is one of the most important factors in determining when a patient can be safely discharged from a surgical facility and has a major influence on the patient's ability to resume their normal activities of daily living.[6]

Perioperative analgesia has been traditionally provided by opioid analgesics. However, extensive use of opioids is associated with a variety of perioperative side effects, e.g., ventilatory depression, drowsiness and sedation, postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV), pruritis, urinary retention, ileus and constipation that can delay hospital discharge. Multimodal or balanced analgesic techniques involving the use of smaller doses of opioids in combination with nonopioid analgesic drugs, e.g., local anesthetics, acetaminophen and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are becoming increasingly popular approaches to preventing pain after surgery. An ideal analgesic agent should be rapid in onset with a long duration of action and produce analgesic activity equal to or superior to opioids like morphine without producing any side-effects.[2] Bupivacaine is a long acting local anesthetic with a half-life of 2.5–3.5 h and has been reported to provide pain control for an average of 6 h. The central analgesic action of paracetamol is like aspirin, that is, it raises pain threshold but has weak peripheral anti-inflammatory component.[5]

Numerous studies have been conducted with intra-peritoneal administration of local anesthetic and paracetamol postoperative analgesia following laparoscopic surgery.[5,6,7] Unlike NSAIDs which have considerable adverse effects, paracetamol with a different mechanism of action has a superior side effect profile and its availability in the intravenous (IV) form makes it very useful when other routes are less feasible.[7] This study was undertaken to compare efficacy of intra-peritoneal bupivacaine and IV paracetamol for postoperative analgesia following laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Objectives included: Qualitative assessment by Visual Analog Scale (VAS) for postoperative pain at the shoulder tip, incision site, deep intra-abdominal and on coughing, occurrence of PONV and any adverse effect.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

After obtaining approval by the ethics committee and written informed consent from all patients, 60 patients over a period of 3 years were enrolled for this randomized prospective study. Sample size was calculated with 95% confidence level and 90% power using the formula n = (Zα + Zβ)2 × σ2/d2. Patients belonging to American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical Status I or II aged between 18 and 60 years scheduled for laparoscopic cholecystectomy were included for this study. Patients were divided into two groups of thirty individuals each by stratification and block randomization where Group I patients received 0.5% bupivacaine as local intra-peritoneal application and Group II patients received IV 1 g paracetamol 6th hourly. Exclusion criteria were patient refusal, acute cholecystitis, inability to understand and use the VAS, history of allergy to NSAIDS and local anesthetics, ASA Grade III and IV, patients with choledocholithiasis, and drain in situ.

Bupivacaine dose was limited to a maximum dose of 2 mg/kg. Preanesthetic evaluation was done on the evening prior to surgery. Patients were introduced to VAS and were instructed to point the intensity of pain on a 10 cm scale. Zero end of the scale is taken as no pain and 10 cm as maximum possible pain imaginable. All patients were premedicated with 10 mg diazepam per orally at night and 5 mg in the morning of the surgery.

In the operating room, an IV line was secured in nondominant upper limb using an 18 gauge IV cannula and a crystalloid infusion was started. Preinduction monitors were electrocardiogram (ECG), noninvasive blood pressure (BP) and pulse oximeter and baseline BP and heart rate were measured. All patients were anaesthetized with propofol (2–2.5 mg/kg) till the loss of verbal response, fentanyl (2–3 μg/kg) and vecuronium for intubation (0.1 mg/kg). Maintenance with N2O, O2 and isoflurane (50%, 50% and 1 MAC, respectively). Ventilation was adjusted to maintain end-tidal CO2 between 30 and 35 mmHg, whereas intra-abdominal pressure was maintained between 10 and 12 mmHg. Monitoring included continuous ECG, heart rate, SpO2, end-tidal CO2, isoflurane concentration, intermittent BP, and neuromuscular blockade.

After the gall bladder was removed, for Group I patients 0.5% bupivacaine 10 ml was instilled in the right subdiaphragmatic space in Trendelenburg position and another 10 ml was infiltrated into the port sites. A volume of 6 ml was infiltrated through the abdominal wall around midline port site and 4 ml at the lateral port sites. For Group II patients, 1 g paracetamol IV was given over a period of 15 min after intubation, before the creation of pneumoperitoneum. In all cases, residual CO2 was evacuated at the end of the procedure by compressing the abdomen before closure of ports. Residual neuromuscular blockade was antagonized with neostigmine (0.05 mg/kg) and glycopyrrolate (0.01 mg/kg). The time of arrival in the postoperative unit is defined as 0 h postoperatively.

Postoperatively the patients were assessed for pain utilizing VAS and Visual Rating Prince Henry Scale (VRS), shoulder pain and the number of analgesic doses required. The above parameters were assessed at 1, 4, 8, 12 and 24 h. The VRS consisted of 0–4 grades with 0 - no pain on cough, 1- pain on cough, but not on deep breathing, 2 - pain on deep breathing but not on rest, 3 - Slight pain at rest and 4 - severe pain at rest. Rescue analgesic consisted of diclofenac 75 mg given IV in 100 ml of normal saline over 20 min when the VAS was more than 6 and VRS was more than 3. The BP, heart rate and respiratory rate were also assessed at the above times.

Data analysis was done using Students unpaired t-test. SPSS version 11.5 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) was used. P <0.05 was considered to be significant.

RESULTS

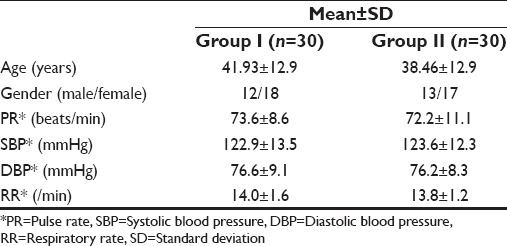

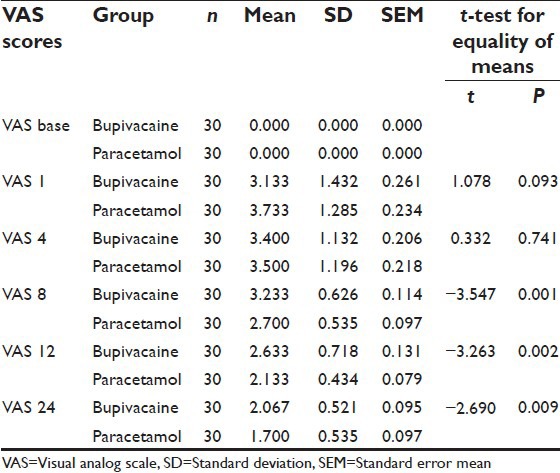

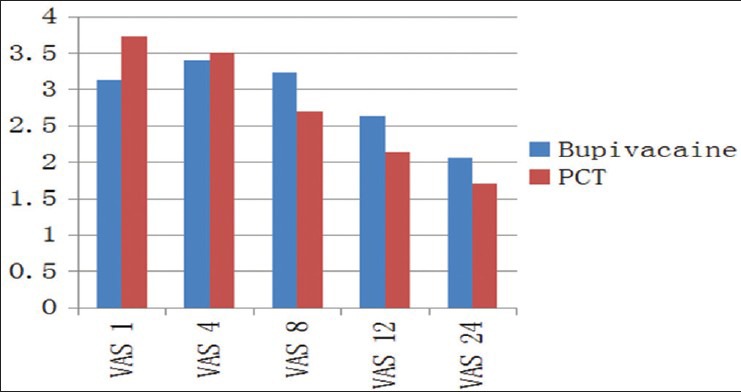

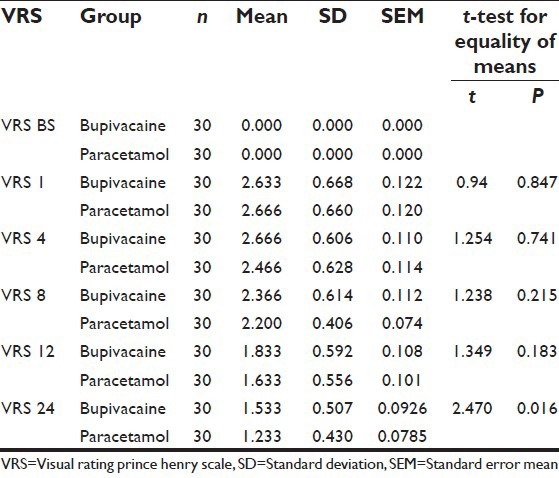

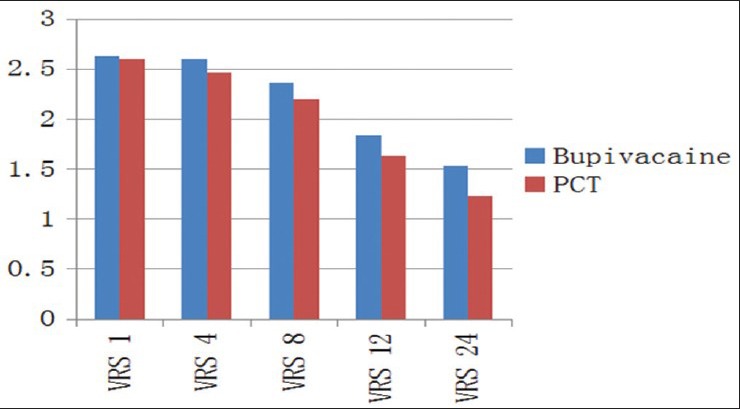

The two groups were comparable in age, sex and preoperative vital signs [Table 1]. The mean VAS scores were significantly higher in Group I as compared to Group II at 8th (P < 0.001), 12th (P < 0.002) and 24th (P < 0.009) postoperative hour. At 1st and 4th postoperative hours, mean VAS scores were comparable between the two groups [Table 2 and Figure 1]. Although the mean VRS scores was higher in Group I as compared to Group II at 12th and 24th postoperative hour; the difference was statistically significant only at 24th postoperative hour [Table 3 and Figure 2]. None of the patients in either of the groups had shoulder pain up to 8 h postoperatively. At 12th h the number of patients having shoulder pain was higher in Groups I as compared to Group II (2 vs. 1); however, this difference was not statistically significant. The total number of patients requiring rescue analgesia was higher in Group II than Group I at 1st postoperative hour (3 vs. 2), but the difference was not statistically significant. In our study, none of the patients in group I had nausea or vomiting or any adverse reactions to local anesthetics. One patient in Group II complained of nausea at 8th postoperative hour.

Table 1.

Demographic data

Table 2.

VAS scores at various time intervals with independent samples test

Figure 1.

Comparison of mean Visual Analog Scale scores between the two groups

Table 3.

VRS scores at various time intervals with independent samples test

Figure 2.

Comparison of mean Visual Rating Prince Henry Scale scores between the two groups

DISCUSSION

Planning for postoperative pain management should begin in the preoperative period. Patient education regarding the degree of pain that they might expect, the pain assessment tools and the modalities of pain treatment that might be utilized should reduce the patient's anxiety and the fear of unrelieved pain. Reduced patient anxiety reduces the incidence of postoperative pain. In addition, patients have to be made aware of the importance of communicating their analgesic needs. They may benefit from an explanation of how much and what type of pain can be expected following their procedure. For example, a separate discussion of the discomfort, rather than significant pain that might be felt in the region of the shoulders and reassurance that this is related to laparoscopy and not their chest or heart are necessary. Patients should receive instruction on the importance of coughing, deep breathing, ambulation and postoperative rehabilitation.[8]

There are three types of pain after laparoscopic cholecystectomy: Incisional, visceral and shoulder pain. The pain being multifactorial, a multimodal approach for pain relief is essential. The pain after laparoscopic procedures is primarily visceral in origin. Factors responsible for this pain may be related to surgical incisions, carbon dioxide insufflation, and the intra-abdominal pressures maintained during the laparoscopic procedure. Higher insufflation pressures should be avoided as they can significantly increase the severity of postoperative pain. Subphrenic and shoulder pain after laparoscopic procedures appear to arise from diaphragmatic and phrenic nerve irritation due to insufflated carbon dioxide. This pain tends to be aggravated by ambulation and may persist for several days after surgery. Residual insufflating gas can also increase the intensity of the postlaparoscopic pain. Therefore, the abdomen should be actively deflated at the end of the laparoscopic procedure.[9]

The results of this study demonstrate that in Group I, intra-peritoneal and intraincisional instillation of 20 ml of 0.5% bupivacaine produces lower VAS and VRS up to 4 h postoperatively. There is specific evidence in the literature to support the use of incisional and intra-peritoneal local anesthetic infiltration at the end of surgery. Infiltration of the surgical wound with local anesthetic can provide excellent analgesia that outlasts the duration of action of the local anesthetics.[10,11,12,13] Bhardwaj et al. studied the effect of 20 ml of 0.5% bupivacaine with 1:200,000 adrenaline instilled intra-peritoneally at the end of surgery in the Trendelenburg position and concluded that it provides good pain relief in the early postoperative period.[14] However, epinephrine does not affect the duration of action of bupivacaine as it is highly lipid soluble and gets bound to tissues. Raetzell et al. measured plasma concentrations of bupivacaine after intra-peritoneal administration of 50 ml of 0.125% bupivacaine (Group A) and 0.25% bupivacaine (Group B). Mean maximum plasma concentrations of bupivacaine reached 0.48 mg/L (range 0.15–0.90 mg/L) in Group A and 1.0 mg/L (0.35–2.10 mg/L) in Group B within 15 min (range 5–30 min). However, there was no significant difference in pain scores or opioid consumption between the groups compared with placebo with 50 ml of normal saline. The lack of analgesic effect can be attributed to the lower concentrations of bupivacaine used because it is the concentration that may be important in laparoscopic cholecystectomy rather than volume.[13]

In our study, with paracetamol, the VAS was lower up to 24 h compared to bupivacaine group, but statistically significant only at 8, 12 and 24th postoperative hour. VRS was lower in group II compared to Group I at 24 h. The reason being IV paracetamol was given 1 gram 6th hourly up to 24 h. Although paracetamol is commonly used for postoperative pain management, its slow onset of analgesia and the nonavailability of the oral route immediately after surgery makes oral paracetamol of limited value in the treatment of immediate postoperative pain. Therefore, a parenteral formulation of paracetamol is an attractive option for the treatment of postsurgical pain.[15] IV paracetamol has been evaluated for postoperative analgesia by many studies in recent years as a single dose of 1 g IV or 1 g IV 6th hourly for 24 h. In our study we used 1 g paracetamol IV over a period of 15 min immediately after intubation before the creation of pnemoperitoneum similar to the study conducted by Salihoglu et al. and also 1 g paracetamol was given IV 6th hourly for 24 h similar to the study conducted by Tippanna et al.[16,17] In comparison to a study conducted by Gregoire et al. where 5 g of paracetamol was given over a period of 24 h, in our study maximum dose of paracetamol administered was limited to 4 g in 24 h, that was well below the toxic dose.[18] Thus sustained pain relief up to 24 h in the paracetamol group is due to the repeated administration of IV paracetamol every 6 h and in the bupivacaine group, good pain relief was achieved in the initial 4 postoperative hours.

CONCLUSION

Although local anesthetic infiltration and intra-peritoneal administration of 0.5% bupivacaine decreases the severity of incisional, visceral and shoulder pain in the early postoperative period, IV paracetamol provides sustained pain relief for 24 postoperative hours after elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Vecchio R, MacFayden BV, Palazzo F. History of laparoscopic surgery. Panminerva Med. 2000;42:87–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rawal N. Analgesia for day-case surgery. Br J Anaesth. 2001;87:73–87. doi: 10.1093/bja/87.1.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ready LB, Oden R, Chadwick HS, Benedetti C, Rooke GA, Caplan R, et al. Development of an anesthesiology-based postoperative pain management service. Anesthesiology. 1988;68:100–6. doi: 10.1097/00000542-198801000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Joshi GP, White PF. Postoperative pain management: Day surgery. In: Rowbotham DJ, McIntyre P, editors. Clinical Pain Management – Acute Pain. London: Arnold; 2003. pp. 329–40. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alam MS, Hoque HW, Saifullah M, Ali MO. Port site and intraperitoneal infiltration of local anesthetics in reduction of post-operative pain after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Med Today. 2009;22:24–8. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gayatri P. Post-operative pain services. Indian J Anesth. 2005;49:17–9. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crews JC. Multimodal pain management strategies for office-based and ambulatory procedures. JAMA. 2002;288:629–32. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.5.629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Payne FB, Ghia JN, Wilkes NC. The relationship of preoperative and intraoperative factors on the incidence of pain following ambulatory surgery. Ambul Surg. 1996;3:127–30. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alexander JI. Pain after laparoscopy. Br J Anaesth. 1997;79:369–78. doi: 10.1093/bja/79.3.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alexander DJ, Ngoi SS, Lee L, So J, Mak K, Chan S, et al. Randomized trial of periportal peritoneal bupivacaine for pain relief after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Br J Surg. 1996;83:1223–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dahl JB, Møiniche S, Kehlet H. Wound infiltration with local anaesthetics for postoperative pain relief. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1994;38:7–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.1994.tb03830.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kehlet H, Gray AW, Bonnet F, Camu F, Fischer HB, McCloy RF, et al. A procedure-specific systematic review and consensus recommendations for postoperative analgesia following laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc. 2005;19:1396–415. doi: 10.1007/s00464-004-2173-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Raetzell M, Maier C, Schröder D, Wulf H. Intraperitoneal application of bupivacaine during laparoscopic cholecystectomy – Risk or benefit? Anesth Analg. 1995;81:967–72. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199511000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bhardwaj N, Sharma V, Chari P. Intraperitoneal bupivacaine instillation for post-operative pain relief after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Indian J Anesth. 2002;46:49–52. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Holmér Pettersson P, Owall A, Jakobsson J. Early bioavailability of paracetamol after oral or intravenous administration. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2004;48:867–70. doi: 10.1111/j.0001-5172.2004.00452.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Salihoglu Z, Yildirim M, Demiroluk S, Kaya G, Karatas A, Ertem M, et al. Evaluation of intravenous paracetamol administration on postoperative pain and recovery characteristics in patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2009;19:321–3. doi: 10.1097/SLE.0b013e3181b13933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tiippana E, Bachmann M, Kalso E, Pere P. Effect of paracetamol and coxib with or without dexamethasone after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2008;52:673–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2008.01650.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gregoire N, Hovsepian L, Gualano V, Evene E, Dufour G, Gendron A. Safety and pharmacokinetics of paracetamol following intravenous administration of 5 g during the first 24 h with a 2-g starting dose. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2007;81:401–5. doi: 10.1038/sj.clpt.6100064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]